Family Counseling and Psychotherapy Techniques

- 1. 1. Directing Work: Prescribing Tasks and Directives 2. Challenging the Symptom and Worldview 3. Use of the Genogram 4. Empty Chair Techniques 5. Sculpting 6. Simple Tactics for Session 7. One-down Positioning 8. Paradox and Paradoxical Intention Demetrios Peratsakis, LPC, ACS and Natalia Boyarinova, LPC

- 2. 2 The difference between Counseling and Psychotherapy is the degree to which the therapist assumes personal responsibility for change. - d.peratsakis

- 3. Purpose: To force and foster change Tasks (rituals/scenarios) and Directives (instructions) provide practice in new ways of thinking, feeling and behaving Mechanics: 1. Define and Assign Task: Scripting and Prescribing Assume authority (power) to direct new experience Session as “safe haven” for change Directives are simple commands: keep them behavioral; ie “Talk to her”; “Get up and go sit next to him”; “Get them to behave” Tasks are complex commands: --- To assign, pretend that you are a Director (therapist) on a movie set: introduce the scene (task) and instruct (directive) the actor’s (client’s) behavior while filming the scene (allowing work to be done): --- Simple introductions, include: “Let’s try something”; “Let’s do an experiment”; “Some people find this helpful”; “I’m going to have you try something that may be uncomfortable”; “What if, we do this…”. • “Homework” is failure prone: make it highly scripted; make behavior independent of others; predict difficulty or failure 2. Staying on Task Once a task has been assigned the therapist's job is to continually redirect any straying or delay back to the task, while working on their own anxiety, impatience and need to rescue. Push-back is to be expected, but not accepted. Two forms of challenge: - Fear a) Anxiety or Angst: comfort the fear and encourage them back to task (“This is very hard”; “Let’s slow down and try again”) b) Morbid Dread: push; if task cannot be completed, focus on the fear: “What is the worse that would happen?”; “What’s happening now?” - Power-play Aimed at the therapist. Dis-arm, dis-engage and redirect the power-play. Address resentment and anger 3. Button-up and Review Simple endings, include: “Was that worse than you thought it would be?”; “How bad was that; what should we do different next time?” “Let’s stop, that’s enough hard work for now”; “I pushed you pretty hard, how pissed-off are you with me?” 3

- 4. 1. Create a new symptom. 2. Move to a more manageable symptom; ie “chores” versus “attitude” 3. I.P. another family member. (create a new symptom-bearer) 4. I.P. a relationship 5. Reframe or re-label the meaning of the symptom (ie. “It seems that her “school phobia” helps her stay home with mom; should we be worried about mom also? Change in any part of the transaction 6. Change the intensity of the symptom/pattern. (Inflate/Deflate) 7. Change the frequency or rate of the symptom/pattern 8. Change the duration of the symptom/pattern 9. Change the time (hour/time of day/week/month/year) of the symptom or pattern. 10. Change the location (in the world or body) of the symptom/pattern 11. Change some quality of the symptom or pattern (ie. use of imagery to impact elements) 12. Perform the symptom without the pattern; short-circuiting. 13. Perform the pattern without the symptom. 14. Change the sequence of the elements in the pattern 15. Interrupt or otherwise prevent the pattern from occurring. 16. Add (at least) one new element to the pattern. 17. Break up any previously whole element into smaller elements 18. Link the symptoms or pattern to another pattern or goal 19. Point to disparities 4

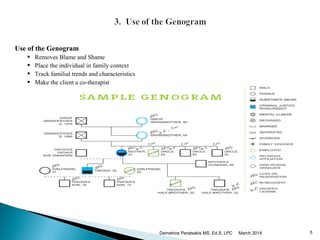

- 5. Benefits Removes Blame and Shame Places the individual in a family context Tracking familial trends and characteristics Makes the client a co-therapist and session collaborative and educational 5

- 6. March 2014Demetrios Peratsakis MS, Ed.S, LPC 6 Genogram continued: Intergenerational Issues and Trends Display Information; for at least three generations show: the client’s name, age, gender , occupation, spouse/partner, children, parents and siblings the wider family such as grandparents, uncles, aunties, and their pairings and children (include names, birth dates, ages, gender, occupation , highest level of education, dates of marriage, divorce, death, etc) how persons are related and the relationship between family members (adoptions, marriages, sources of stress/support, alliances/collusions, etc) Clinical and health issues such as child/partner abuse, drug and alcohol dependency, anxiety, depression, heart conditions, cancers, diabetes, etc. ethnic and cultural history of the family socioeconomic status of the family major nodal events and recent trigger issues, such as pregnancies, illnesses, relocations, or separations Tracking and Interpreting post the client’s symptoms/concerns and trace similar patterns across member relationships look at roles and rules that may have bearing on the presenting problem (s); post myths, legends and value statements look at life-cycle, nodal events and triggers for timing surrounding the presenting problem(s) demarcate, by dotted inclusion lines, members who participates/in the presenting problem client(s) and therapist (s) share observations and interpretations from the genogram

- 7. Use of Chairs (6 sample techniques) Chairs are relatively convenient and available props that can be used to illustrate relational issues and dynamics or to heighten and lower tension and confrontation among members within a session. As such, they make the covert, overt, and allow new forms of alignment and communication to be practiced: 1. “Open Forum”: Set two seats, side by side (facing each other), in the middle of the room and ask “Who wants to work?” 2. Decision Making: Set two chairs facing each, several feet apart; define each chair as representing the opposing or counter point of view in a dilemma. 3. Controlled Confrontation: Set two chairs back-to-back (not touching). Angry/Volatile clients are encouraged to begin a dialogue. 4. Co-therapist: Set two chairs, side by side, with a third several feet away from both. Have client sit adjacent to you and ask their aide in helping the “client”. ie. “Chris, tell me what “Chrissy” needs to do to become the new-Chris, “Christina”? 5. Greek Chorus: Set empty chair off to the side of the therapist. Use the “Ghost” therapist as a contrarian “Greek Chorus” meta-message of refusal to change. 7

- 8. 6. “Ghost”: Advanced technique requiring a relaxation directive 6. A. Make an estranged or cut-off member “visible” Ghosts are family legacies, myths, and legends as well as dead and estranged members whose persona have presence and meaning to the individual or group. They may be “good” ghosts or “bad” ghosts, and may be as simple as a family or personal rule or value or a more complex, over-riding philosophy or vantage point on how to behave, interact and even think. “Good” ghosts can provide support and nurturance; “bad” ghosts can be inexorable in their demands and ruthless in their punishments. • “Ghosts” often ‘haunt’ due to guilt, shame, retribution or vengeance. Anger and rage can be elixirs. • Make covert issues and rules, overt: (ie. “Temper” = adversary that one can battle) • Work through what makes the ghost more/less restless…what issue needs to be put to rest? • Write a letter, epitaph or will to the Ghost, emphasize disparities and similarities; develop a new legend or myth; make a “voodoo-doll”; create a ritual for taming the ghost • Reconnect to estranged partners and members • Hold a séance or conduct an exorcism • Prescribe the phantom 6. B. Make a volatile emotion such as Rage or Shame “controllable” This is an excellent technique for acquiring greater mastery of something heretofore experienced as not under one’s control, such as emotional (ie. rage, sadness) or physical pain. Picture the “feeling” that you’re having What color is it? What is its shape? It’s size? What texture does it have? What’s its temperature? Can you change its shape….it’s color….it’s temperature…..it’s texture…. Now, make it larger/smaller; hotter/cooler; more rough/smoother; less red/more red; taller/shorter. For homework, sit and relax and practice changing the one thing we have agreed to (always move to less toxic) 8

- 9. What it is Putting family members in physical positions that represent how “sculptor” sees each person’s role in the family. How it works Each family member given opportunity to sculpt family as they see it. Gives nonverbal, symbolic depiction of family process from each person’s perspective. o Nonverbal confrontation that bypasses cognitive defenses. o Able to literally see how he or she is contributing to problematic family process. Best to let each person sculpt before allowing discussion of sculptures. Encourage family members to respect the subjective experience and deepen understanding of one another. Benefits Makes the covert, overt. Provides insight into each other’s perspective and experience of relationship Creates a set time-line of “Now” and “Future”; “How do we get from where we are to there?” Shows disparities in perspective and roles; “How do we get these “pictures” to match-up better? Makes session fun and provides a continuous frame of reference for session

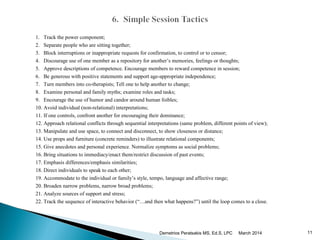

- 10. 1. Track the power component; always be mindful of who brought them in and can get them back 2. Separate people who are sitting together if they are in collusion or alignment 3. Block interruptions or inappropriate requests for confirmation, to control or to censor 4. Discourage use of one member as a repository for another’s memories, feelings or thoughts 5. Approve descriptions of competence. Encourage members to reward competence in session; model encouragement 6. Be generous with positive statements and support age-appropriate independence 7. Turn members into co-therapists; Tell one to help another to change 8. Examine personal and family myths and make roles and rules overt 9. Encourage the use of humor and candor around human foibles 10. Avoid individual (non-relational) interpretations 11. If one controls, confront another for encouraging their dominance 12. Approach relational conflicts through sequential interpretations (same problem, different points of view) 13. Manipulate and use space, to connect and disconnect, to show closeness or distance, alliances or collusions 14. Use props and furniture to illustrate relational components; introduce concrete reminders, short-hand symbol reminders 15. Give anecdotes and personal experience. Normalize symptoms as social problems associated with change and growth 16. Bring situations to immediacy/enact them/restrict discussion of past events 17. Emphasize differences/emphasis similarities to create alliances or diffuse coalitions 18. Direct individuals to speak to each other; enact problems in session 19. Accommodate to the individual or family’s style, tempo, language and affective range 20. Broaden narrow problems; narrow broad problems 21. Doggedly address major sources of stress, especially emotional cut-offs; cross-generational coalitions; partner discord; impairment in one of the partners; impairment in one or more of the children; powers-struggles; betrayals and conflicts 22. Track the sequence of interactive behavior (“…and then what happens?”) until the loop comes to a close 10

- 11. 23. Identify “Lifestyle” (Adler) themes that color interpretations, thereby driving feelings and statements about self in relation to the world; challenge Common Cognitive Errors (CBT/Beck, 1976): Filtering--taking negative details and magnifying them, while filtering out all positive aspects of a situation Polarized thinking--thinking of things as black or white, good or bad, perfect or failures, with no middle ground Overgeneralization--jumping to a general conclusion based on a single incident or piece of evidence; expecting something bad to happen over and over again if one bad thing occurs Mind reading--thinking that you know, without any external proof, what people are feeling and why they act the way they do; believing yourself able to discern how people are feeling about you Catastrophizing--expecting disaster; hearing about a problem and then automatically considering the possible negative consequences (e.g., "What if tragedy strikes?" "What if it happens to me?") Personalization--thinking that everything people do or say is some kind of reaction to you; comparing yourself to others, trying to determine who's smarter or better looking Control fallacies--feeling externally controlled as helpless or a victim of fate or feeling internally controlled, responsible for the pain and happiness of everyone around Fallacy of fairness--feeling resentful because you think you know what is fair, even though other people do not agree Blaming--holding other people responsible for your pain or blaming yourself for every problem Shoulds--having a list of ironclad rules about how you and other people "should" act; becoming angry at people who break the rules and feeling guilty if you violate the rules Emotional reasoning--believing that what you feel must be true, automatically (e.g., if you feel stupid and boring, then you must be stupid and boring) Fallacy of change--expecting that other people will change to suit you if you pressure them enough; having to change people because your hopes for happiness seem to depend on them Global labeling--generalizing one or two qualities into a negative global judgment Being right--proving that your opinions and actions are correct on a continual basis; thinking that being wrong is unthinkable; going to any lengths to prove that you are correct Heaven's reward fallacy--expecting all sacrifice and self-denial to pay off, as if there were someone keeping score, and feeling disappointed and even bitter when the reward does not come.

- 12. 24. Image-enrichment (Ego-building) Techniques a. Increase Differentiation Of Self; define and delineate Self-boundaries b. Increase sense of belonging; reconnect to others, meaningful goals and activities c. Employ Behavior Rehearsal; real and imagined practice d. Reframing: turn meaning and personal context from minus (-) into plus (+) e. Explore fears and dreads (“What bad would happen? And then what?”) f. "Boasting" ("What else are you good at?"; "What is he/she good at?") g. Hypnotic-suggestion. ("When did you first realize you could..."). h. Simple Paradox: exaggerate the symptom or complaint i. Reduce "Buts" & "Shoulds"; move to acceptance of behavior truth. (Change "But" to "And“) j. "Doom" client to Success (direct task, prescribing frequency, duration, location, participants, et al. Predict sabotage & failures) k. Examine progress and repeat sequence portions; gift-giving and rewards l. Log all that is going well enough to Not want to change m. Work through issues of Guilt, Anger and Shame n. Increase social competency: art, dance, wine, film, literature o. Increase sense of physical safety and health: vitamins, yoga, karate p. Pet therapy: new puppy, kitten or fish; volunteer at kennel q. Attach burdensome rituals to negative thought and behaviors r. Therapist takes one-down position s. Paradoxical Interventions; Prescribe symptoms, rules and myths t. Heal trauma through (advanced) Ghost and Revenge techniques. 25. Ghost techniques Exorcizing the Ghost: confront the source of the trauma, loss or betrayal (adversary; illness, etc) Exorcizing One’s Past: make the client the therapist and have them treat their past self Born Again/In-Utero Re-growth: recreate one’s birth and life history New Identity: create a new persona and history (ie. “that was the old way, the old you (“Chrissy”); tell me how Christina, the new you, will do it?”)

- 13. 26. Revenge Tactics: Betrayal demands revenge It is difficult for forgiveness to occur without some genuine expression of remorse. While several therapies address the issue of trust and betrayal, most gloss over the natural imperative for revenge. Likewise, few exploit the enormous benefit of repentance and the admission of guilt to the victim without which repair of the trust agreement will be less secure. The alternatives for demonstrating these expressions are rather limitless and best left to the creative energies of the victim and offender: Sample “Acts of Contrition” (to make amends; penance) for the perpetrator: get on their knees and beg for forgiveness talk about their own shame; describe their own weakness write a letter, poem or newspaper ad of apology contact relatives, children, peers or co-workers and “confess to their sin” allow the victim to slap or spit in their face arrange and participate in a “public humiliation” destroy or damage a favored possession/give away a cherished belonging hold a “confessional” sacrifice a favored activity or need Sample “Acts of Revenge” (planned punishment) for the victim: retaliate (retaliation is an effective, yet controversial, means of punishing another; the therapist must be careful about condoning illegal or “immoral” behavior) redefine the terms and purpose of the relationship; include zero-tolerance for abuse arrange a structured separation, using therapy as the common meeting stage meet with an attorney for guidance on a legal course of action create a “voodoo-doll” or “target” of the perpetrator, ie. collage of hate, a letter of revenge arrange for a period of indentured servitude (by agreement with perpetrator) client is now punishing someone in small doses, in different ways. Have them imagine a way that they could make this person suffer in one, big enough way to call-it-even. wish a major illness or disease on some one. establish a ritual that would help them channel being upset throughout the week

- 14. 27. Planning Tasks Couple/Family Council; planned airing of grievances Plan a vacation, date, meal, task, chore or other event in-session Create a ritual, séance or rite of passage to change Plan on reversing roles for the week/for a task Experience an Early Recollection or Imagery session in unison, then share interpretations 28. Spitting in One’s Soup Exposing the hidden agenda or motive can neutralize its utility and power; make the covert, overt. This is especially helpful when it undermines the nobility often associated with good intentions. To do so, point to the real motive of the client's behavior; for example: “Are you’re trying to make me feel angry, so that I can push you away and then you can tell yourself that nobody wants you?” “You seem to be punishing her with your depression (incompetence); that’s a clever way to get even. You must be realy pissed at her!” Turning to wife in session: “I wonder if he brought you so that I can take care of you while he leaves and escapes the marriage!” 29. When all else fails: prescribe the symptom invite a consultant or co-therapist to session convert the client to a therapist pronounce the client cured!

- 15. While the “one-down” position has been described by several tacticians, it became popularized by the Mental Research Institute (MRI) brief therapy model. Artkinson and Heath, posited that the therapist is an intimate part of the treatment system and must, therefore, take into continual account how they contribute to the dynamics of the interactions in session. The more in-tune the clinician is to nuances within the therapeutic alliance, the more readily they can respond to the underlying power dynamics and nimbly change or reposition their approach. A “one-down” position requires that the therapist do something to remove him or herself from a stance of presumed power and expertise thereby unbalancing the power structure and placing the client in a more powerful position (Fisch, Weakland, and Segal, 1982). This may be employed as an overall strategy, as when working with neurotic depressives, or as an immediate ploy throughout the course of the session. The importance of this stance can best be appreciated while working with individuals whose concept of self is characterized by a sense of “worthless” and who perceive others as being in positions of superiority or dominance. Ostensibly, by taking the one-down, the therapist occupies the lower position, thereby forcing the client to experience themselves in a “one-up”. This provides a brief but compelling challenge to their customary sense of self and their preferred view of the world. 7. The One-down Position; AKA Akido Psychotherapy

- 16. Paradoxical Intervention in Counseling -courtesy of Psychology “Alfred Adler is widely thought to be the first therapist to make explicit use of paradoxical interventions. The use of these techniques stemmed from Adler’s belief that a successful power play against the therapist results in increased patient self-esteem and therefore patient improvement. Thus, in a sort of “therapeutic judo,” Adler encouraged patients to rebel against him. Adler often used humor in prescribing his injunctions. From a behavioral point of view, in the 1920s, Knight Dunlap developed an approach that he called negative practice. This involved deliberately practicing behaviors that one wanted to eliminate rather than attempting to avoid them. Dunlap saw this as a way of bringing them under control. In doing so, he argued against the law of habit formation, which states that repetition of a response increases the probability of its recurrence. Perhaps the best known therapist to use paradoxical interventions and the first to use that term explicitly was Viktor Frankl. As part of his logotherapy, he developed what he called paradoxical intention, in which he encouraged patients to do or wish for that which they most feared. For example, a patient who was very afraid of contamination was urged to wish to become as dirty as possible. This is very similar to what later was called symptom prescription. 8. The Use of Paradox and Paradoxical Intention

- 17. Types of Paradoxical Interventions There are different ways of classifying paradoxical interventions, but one useful system makes a distinction between compliance-based and defiance-based interventions. All of the specific paradoxical techniques can be placed within one or the other. Compliance-Based Interventions These interventions are used with the expectation the client will comply with the counselor’s suggestion or directive and thereby improve. In the original compliance-defiance model, clients who were low on psychological reactance, that is, the tendency to resist interpersonal influence, were expected to do best with these strategies. There are several types of compliance-based interventions. Reframing Also called positive connotation, this involves a shift in meaning of the problem behavior from negative to positive. For example, feeling depressed might be reinterpreted as exquisite sensitivity to one’s internal feelings and a willingness to make sacrifices for the good of others. Anxiety might be reframed as a strong sense of caring about the outcome of a task. A related technique is relabeling, in which the label of a problem behavior is changed without changing its meaning. Negative connotation can also occur, in which a positive behavior is relabeled as negative, but that rarely occurs because there is little point.

- 18. Symptom Prescription This strategy involves urging the client to perform or even exaggerate the very behavior that is the problem in the first place. As a compliance-based intervention, it derives its power from the new control the client has over a behavior that was formerly seen as uncontrollable. A variant is symptom scheduling, in which the client is directed to (for example) feel deliberately anxious or fight with his or her spouse at a particular time. By implication, if the behavior can be controlled in one direction, it can be controlled in the other. This technique is very similar to Frankl’s paradoxical intention. Defiance Based Interventions These interventions are used with the expectation the client will defy the counselor’s suggestion or directive and thereby improve. They are similar to Adler’s original conceptualization. In the original compliance-defiance model, clients who scored high on psychological reactance were expected to do best with these strategies because they would resist the therapist in order to maintain their freedom. Symptom Prescription Although listed as a compliance-based intervention, this can also be conceptualized as a defiance-based intervention. With reactant clients, it derives its power from the fact that client resistance to the counselor’s suggestion or directive to perform the problem behavior deliberately reduces the frequency of that behavior. By implication, the behavior is under more conscious control than the client originally thought. Reactant clients tend to resist symptom scheduling as well, often finding it more onerous than simply giving up the problem behavior. Restraining Strategies In using this technique, the counselor either tells the client not to change the problem behavior (prohibiting change) or to change very slowly and carefully (inhibiting change). With this directive, reactant clients can resist the counselor only by changing, which is the point of therapy in the first place. It also empowers clients by placing the locus of change squarely upon them. The most common use of restraining strategies has been in sex therapy, where impotent couples are told not to attempt to engage in sexual activity for a period of time. With the pressure to perform thus removed, spontaneous sexual activity often occurs, much to their surprise. Positioning Here the counselor deliberately exaggerates clients’ negative views of themselves; useful when the counselor suspects these negative statements are designed to elicit positive comments from others in a “fishing for compliments” exercise. Adlerian therapists refer to this as “spitting in the client’s soup.” This technique should be used judiciously to avoid sounding sarcastic or uncaring. It should not be used with clients who have a truly negative view of themselves.”

- 19. 19 Thanks!