Air Force Officer Evaluation System Project

- 1. , - •"i FILE COPY SYLLOGISTICS INC. FIUNAL REPORT co AIR FORCE OFFICER EVALUATION SN'STEM PROJECT 04 La N IV ' i• & THE HAY GROUP DTIC ELECTE JUL 11 W B MANAGEMENT * PLANNING * ANALYSIS -N 1 7 r xT' -c Fr A a ~<ii

- 2. TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION TITLE PREFACE ............................................. iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................ v INTRODUCTION .................................................................. I-1 Historical Background ........................................................... I-1 Project Objectives and Tasking ............................................ 1-9 II STUDY METHOD................................................................... I-I Phase 1: Background Study .......................... II-I Phase 2: Data Gathering ....................................................... 11-2 Phase 3: Literature Review .................................................. 11-4 Phase 4: Data Analysis ......................................................... 11-5 Phase 5: Synthesis of Recommendations ............................. 11-5 III FINDINGS ON PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL IN NON- AIR FORCE ORGANIZATIONS ........................................... I11-I Performance Appraisal: Findings from the Literature ....................................................................... III-1 Performance Appraisal: Findings from the Private Sector ................................................................. 111-23 Performance Appraisal: Findings from the Other Services ................................................................ 111-33 IV FINDINGS: AIR FORCE OFFICER EVALUATION SYSTEM ................................................................................ IV-I Major Features of the Current OER System ....................... IV-I Issues Affecting Officer Evaluations ................................... IV-8 Summary ................................................................................. IV -21 V CONCEPTUAL DESIGNS FOR THE AIR FORCE OER ............. V-I Formulation of Conceptual Design ....................................... V-I Testing and Redesign of Concepts ....................................... V-5 Conceptual Designs for Officer Evaluation ......................... V-6 Uniform Elements of the Conceptual Designs ............................................................................... V-7 Conceptual Design I: Differentiation through Command Persuasion ......................................... V- 17 Conceptual Design 2: Differentiation through Rater Persuasion .................................................. V-22 Conceptual Design 3: Differentiation through Top Block Constraint .......................................... V-29 Evaluation of Conceptual Designs ........................................ V-37

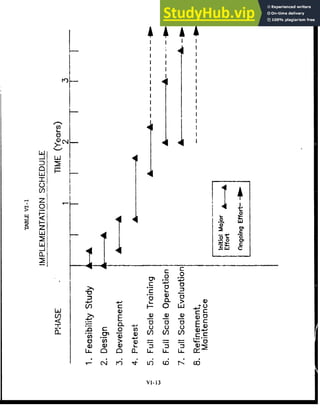

- 3. SECTION TIT[E PAGE VI IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ..................................................... VI-I Feasibility Assessment and Final Decision ................................................................................. V I-2 Design ..................................................................................... VI-3 Development........................................................................... V I-5 Test ............................................ VI-6 Full-Scale Training ................................................................ VI-8 Full-Scale Operation .............................................................. VI-9 Evaluation ............................................................................... VI- I1 Refinement and Maintenance ............................................... VI-12 VII CONCLUDING COMMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ........ VI-I Recom mended Initial Steps................................................... VII-2 Recommended Changes to OER Process ................ VII-3 Recommended Implementation Actions ............................... VII-5 Other Issues ............................................................................ VII-7 ApPPENDICES A R EFERENCES .................................................................................... A -I B SUMMARY OF PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL METHODS ....... B-I C PRIVATE SECTOR PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL INTERVIEWS .................................................................................... C-1 D INIrIAL AIR FORCE INTERVIEWS .............................................. D-i E FEEDBACK INTERVIEW SUMMARY .......................................... E-I F OER FORMS USED IN THE SERVICES ........................................ F-I Accession For NTIS GRAI DTIC TAB 0l Unaruiounced 0 Just trtoatton D1 button/~ Availability Codes ~veil and/or Dist Speoial ii

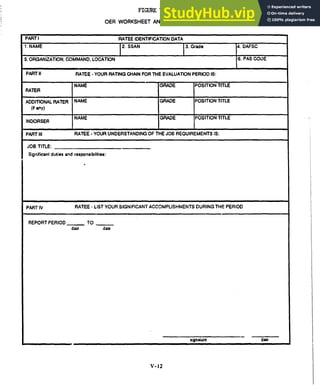

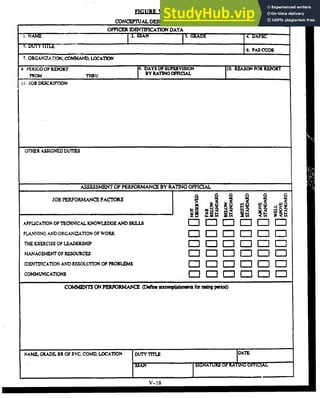

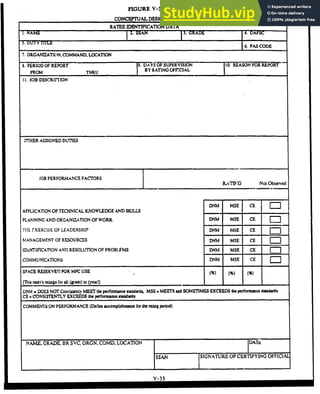

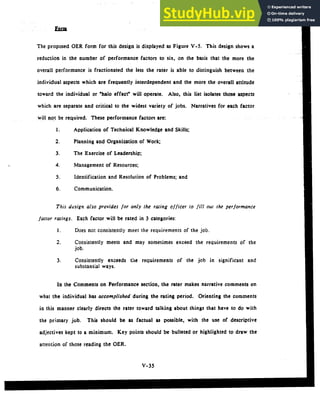

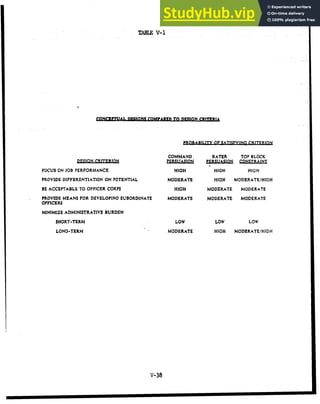

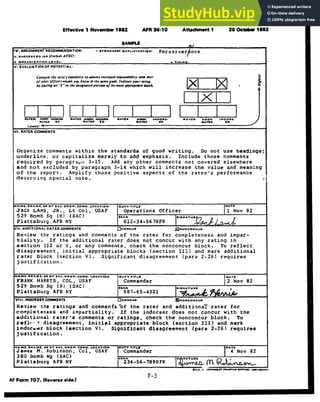

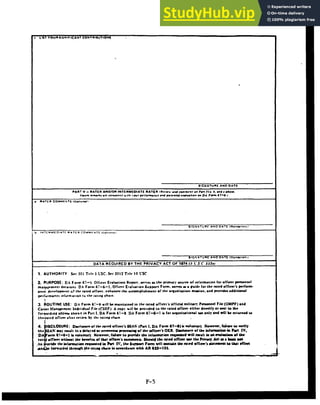

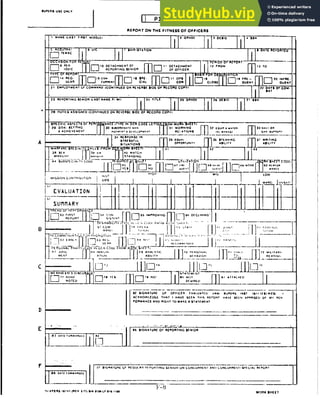

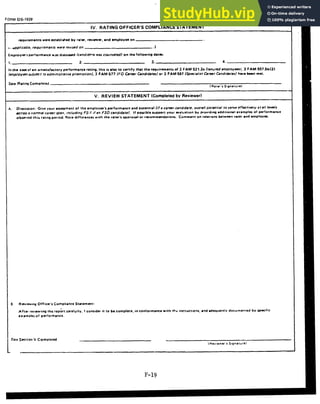

- 4. LIST OF TABLES LA.BETITLE PG I-! Highlights of the Air Force OER ..................................................... 1-6 1l-I Focus Groups Identification ............................................................... 11-3 I11-1 Comparison of Performance Appraisal Methods by Purpose and Costs ....................................................... 111-20 111-2 Other U.S. Services OER Comparison ............................................... 111-64 V-I Comparison of Conceptual Designs to Design Criteria .............................................................................................. V-38 VT-I Implementation Milestone Schedule .................................................. VI-13 LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE TITLE PAGE IV-I Air Force Form 707 ........................................................................... IV-4 V-1 Sample Job Description ..................................................................... V-10 V-2 OER Worksheet and Counseling Form ............................................. V-I12 V-3 Conceptual Design I .......................................................................... V-19 V-4 Conceptual Design 2 .......................................................................... V-25 V-5 Conceptual Design 3 .......................................................................... V-33 iii

- 5. PREFACE Syllogistics, Inc., and The Hay Group have prepared this final report of the Air Force Officer Evaluation System Project sponsored by the Deputy Chief of Staff/Personnel, under Air Force Contract No. F49642-84-D0038, Delivery Order No. 5025. Lieutenant Colonel James Hoskins, Personnel Analysis Center, Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, Personnel, and Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Wyngaard, Air Force Military Personnel Center, monitored this effort and provided helpful comments on the draft final report. The Study was executed by a combined project team of Syllogistics, Inc., and The Hay Group. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should in no way be interpreted as an official position, policy, or decision of any Government agency, unless so designated by other official documentation. SYLLOGISTICS STUDY PERSONNEL Mr. Frank M. Alley, Jr., Project Director and Principal Author Ms. Forrest Bachner, Analyst and Co-Author Ms. Donna Lessner, Analyst Mr. Stuart H. Sherman, Jr., Senior Vice President, Corporate Oversight Dr. Susan Van Hemel, Analyst and Co-Author Mr. David Weeks, Consultant HAY GROUP STUDY PERSONNEL Dr. George G. Gordon, Technical Director and Co-Author Mr. Jesse Cantrill, Analyst Lt. General (USAF, Ret.) Edgar Chavarrie, Consultant Mr. Gregori Lebedev, Partner and General Manager, Corporate Oversight Mr. Rene Morales-Brignac, Analyst and Co-Author iI,

- 6. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY From June through September 1987, Syllogistics, Inc., and the Hay Group conducted a study to examine the strengths and weaknesses of the current United States Air Force Officer Effectiveness Report (OER) system and to recommend alternative designs which could improve its usefulness. Two other groups conducted separate but concurrent efforts with the same study objective. These were active duty and retired senior Air Force officers at Randolph AFB and students at the Air Force Command And Staff College. Specific Air Force guidance for the project was that any alternative conceptual design to the OER should: I) focus on the officer's current job performance; 2) provide good differentiation among officers on potential for promotion and for successfully executing higher responsibility; and 3) provide some vehicle for giving officers feedback on their performance to support career development and counseling. The study was carried out in five major phases: 0 A study of the background of the officer evaluation process in the Air Force, including review of documentation and briefings by Air Force personnel; 0 The field data gathering phase which included interviews and focus group discussions with Air Force officers and functional managers, (interviews and focus groups were conducted at Andrews, Charleston, Langley, Offutt, Randolph, Scott, and Wright-Patterson Air Force Bases); o A review of performance appraisal in non-Air Force organizations (literature review, industry, other military services and government entities); o The analysis of the data; and v

- 7. o Synthesis of options and recommendations. KEY FINDINGS Key findings from the study are described below, by source. LITERATURE o While a wide variety of performance appraisal methods have been studied, most are unacceptable because they are either inappropriate to Air Force needs or totally impractical to implement. The combination of graphic rating scales and verbal descriptions remains, in our judgment, the only feasible path to pursue. 0 A performance appraisal system should focus on a single purpose, e.g., promotion. Other purposes should be addressed through alternate means. 0 Pbrformance evaluations can be improved by training the evaluators. This applies to both rating techniques and the need to rate accurately. o Counseling (performance or career) is best done separately from the formal evaluation. OTHER SERVICES 0 Each of the other services recognizes the special relationship between an officer and his/her immediate supervisor and has tried to reduce the conflict between maintaining this relationship and providing an honest evaluation. vi

- 8. o Each of the services has some mechanism for minimizing inflation in ratings, including peer rankings (Navy and Marine Corps), rate-the-rater (Army), and intensive headquarters review (U.S. Coast Guard). INDUSTRY o Since the principal purpose of performance appraisal in the private sector is to support relatively short-term compensation decisions, much of what is done there would not meet Air Force needs. o Some type of rating control is prevalent in the private sector, but it is usually driven by the compensation or merit increase budgets. o Performance feedback is encouraged and emphasized as an important component in supervisor-subordinate relationships, and most private sector organizations ti"-n supervisors to give such feedback. AIR FORCE CULTURE o There exists the perception that the Air Force officer corps is an elite group who are all above average. o The "controlled system" had a very negative effect on morale. o There is an unwillingness to openly make fine distinctions among officers. o Career advancement is often viewed as more important than job performance, especially by junior officers. DEVELOPMENT OF CONCEPTUAL DESIGNS Building upon the foregoing rich and diverse baseline of information, the Syllogistics/Hay study team developed three alternative approaches to enhance the OER vii

- 9. process. These alternatives were developed in accordance with several design criteria and guiding considerations. The design criteria stated that an improved OER should: o Focus on job performance, not peripherals; o Provide differentiation in potential for promotion; o Be acceptable to the officer corps; o Provide a means for developing subordinate officers; and o Minimize the administrative burden. In addition to these criteria the project team worked with a number of considerations, including: Alternative OER designs should reflect and sustain the larger Air Force culture; 0 Within the Air Force, the alternative OER designs should encourage change in attitudes and habits concerning the OER; o Promotion board judgment, not mere statistics, should be the ultimate method of making career decisions; and o Alternative OER designs should be practical to implement. RECOMMENDED OER DESIGNS The study-developed alternatives share a number of common elements but represent three levels of departure from current practices. Common elements in the designs include a parallel, "off-line" feedback system between the rater and ratee; ratings on fewer performance factors; a single verbal description of performance which focuses viii

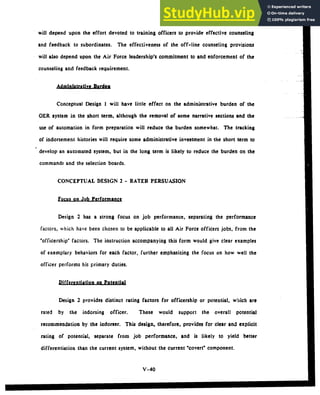

- 10. on specific accomplishment, not adjectives; computer basing of ratings; an improved method for producing job descriptions; and having potential rating done only by officers above the level of the rater. The principal distinguishing factor among the three alternatives resides in the methods used to assure that differentiation among officers is built into the system. CONCEPTUAL DESIGN 1 The first alternative accompi;.z.: differentiation in the same way as does the current Air Force system. That is, differentiation is represented by the level of the final indorser. Discipline is maintained by persuasion from the Chief of Staff to the MAJCOM commanders and by providing promotion boards with information on the distribution of indorsements produced by each command. CONCEPTUAL DESIGN 2 The second alternative calls for ratings of or[gzmanc by the rater on a number of scales and rating of pntial by the indorser on a separate series of scales. "T.is method attempts to obtain a fair degree of dispersion through the "rate-the-rater" concept. Specifically, rating and indorsing histories become part of every OER submitted to a promotion board and also become part of the rating and indorsing officers' records (and selection board folders) to be considered in their own evaluations. This alternative would provide a powerful stimulus to differential ratings. However, given the Air Force history and culture favoring "firewalling*, there is substantial risk that this approach would meet considerable resistance to compliance from the officer corps; since with a changed system, many officers would be rated significantly lower than they are currently. ix

- 11. CONCEPTUAL DESIGN 3 The third and preferred alternative, differentiation through top block constraint, is designed to reduce any stigma of "negative" ratings, while simultaneously placing greater emphasis behind recommendations for early promotion by limiting them to ten percent of each grade at the wing level or equivalent. This ten percent target would allow for the overt identification of the truly outstanding performers. At the same time, it is a small enough minority of the population so as not to threaten officers who are not included in the ten percent stratum. By this approach, the rater would evaluate the overwhelming majority of officers as "meeting and sometimes exceeding" job requirements. The rater is encouraged to limit the number of officers rated "consistently exceeds the job requirements,' through the rate-the-rater concept. The wing commander, on the other hand, would be compelled by regulation to comply with the ten percent early promotion recommendation limit. Based on the study findings and analysis, the consulting team believes that the third alternative is most likely to meet the Air Force's needs in both the short and long term. In the short term, the amount of differentiation is very modest, but the possibility of acceptance without major upheaval is reasonable. In the long run, as the ten percent ratings and indorsements are distributed, promotion boards will be compari,,8 individuals with variable and qu:litatively different records (since an individual may receive different top block ratings on different factors from different raters and indorsers). OTPER RECOMMENDATIONS Some changes are also recommended in the information supplied to promotion boards. In addition to supplying rating and indorsing histories, it is recommended that only OERs in the current grade or the previous five OERs (whichever is greater) be provided, the board be given a list of Special Category Units (SPECAT) that are !ikely x

- 12. to have a high proportion of outstanding officers, and a thorough exposition of the rating tendencies either of the command or of the raters/indorsers be provided to the boards along with the selection folders. The final recommendation focuses on the importance of a carefully planned and deliberate implementation of any modification to the OER process. This is indeed a critical considerat;on; since the implementation phase involves a number of complex stages and sets the stage for the acceptance (or non-acceptance) of a modified officer evaluation system. The report provides the necessary rationale and backup information for each of the conclusions and recommendations. We believe that the recommendations are workable and, if implemented, will contribute significantly toward assuring the continuation of a quality officer force. xi

- 13. SECTION I INTRODUCTION From June through September 1987, Syllogistics, Inc., in conjunction with the Hay Group, conducted a study to examine the strengths and weaknesses of the current United States Air Force Officer Evaluation Report (OER) and to recommend alternative designs which could improve its usefulness. This report documents the findings and recommendations from that study, and is organized in the following way. Section I gives the historical background of the OER and explains the project's objectives and tasking. Section II sets out the p~rocedures which were followed in the study. Section III presents the findings of the data collection and analysis phases of the study from non-Air Force sources, while Section IV gives the Air Force specific findings. Our rationale in formulating alternative OER designs is given in Section V followed by indepth descriptions of these alternatives for improvement of the OER system. Section VI outlines a proposed implementation plan and Section VII concludes with summary observations of the study group. The assessment of officer performance is an important function for the United States Air Force and makes a significant contribution to the maintenance of the consistent high quality of its officer force. The Air Force uses the OER for several purposes, including: selection for promotion and school assignment; job assignment decisions; and augmentation, and separation decisions. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The Air Force like many large organizations has experienced inflated evaluation ratings and/or evaluation systems which were incompatible with their overall purposes. There have been six distinct phases in the Air Force OER system since the establishment of the Air Force as a separate service in 1947. These are: I) the forced choice method 1-1

- 14. adopted from the Army in 1947-49; 2) the critical incident method used from 1949-52; 3) rating of performance factors with narrative commentary, 1952-1960; 4) the "9-4" system, 1960-1974; 5) the "controlled era", 1974-1978; and finally, 6) a return to a mechanism similar to 3) from 1978 to the present. Although these phases will be discussed in greater detail in the following pages, two characteristics have recurred throughout this history. The first characteristic is that throughout all the OER changes, major and minor, the Air Force has availed itself of extremely high-level expertise, from academia, industry, and in-house, in its deliberations. The Air Force has over the years been willing to consider many state-of-the-art approaches to performance appraisal. The second characteristic is the fundamental conflict between administrative need for differentiation, as institutionalized through the *up or out" system, versus an institutional reluctance to identify less than outstanding performance. PHASE 1: 1947-1949 Initially the Air Force adopted the A-my system for its OER program. This system included narrative comment, but the primary rating tool was the forced choice method which had been developed during World War I! by industrial psychologists as a means of reducing bias in the ratings of Army officers. In this method the rater is asked to choose from sets of phrases those which are most and least descriptive of the ratee. Raters did not know how the overall rating would come out, as the OER forms were machine read and scored according to a "secret" formula. The forced choice system was discontinued due to the lack of rater acceptance. The raters wanted to know how they were "grading" their subordinates. 1-2

- 15. PHASE 2: 1949-1952 In 1949 a new evaluation system was implemented which incorporated the critical incident approach as well as mandatory comments by the rater. The front side of the form showed the rater's comments about certain ratee traits and aspects of performance along with the indorsement. The reverse side covered proficiency and responsibility factors on which the rater evaluated the ratee. The scores were then multiplied by a weighting factor, totaled, and divided by the number of factors to derive a total score. This system was terminated in 1952 due to inflation of ratings and problems with the scoring of the forms. Total score became the predominant concern, outweighing individual factor scores. In addition there was some indication that inappropriate weights had been assigned to certain factors. Finally, the ratings on the front and reverse sides of the form often showed an illogical relationship and the form was very time-consuming to complete. PHASES 3 AND 4: 1952-1974 In 1952 a third OER system was implemented. This system was derived from a study of private organizations, the other U. S. military services, and the Royal Canadian Air Force. The basic form of the 1952 system incorporated six performance factors which were rated against graduated standards. The reverse side of the form cailed for an overall rating as well as providing space for the indorsement. Although there have been many forms as well as policy changes since the 1952 system was implemented, the basic form and aim of the system have remained consistent, with the exception of the 1974-1978 period, through the present. 1-3

- 16. The changes which have occurred to the 1952 system include the timing of OER preparation. This has alternated between a prescribed date and occurrence of an event, e.g., a permanent change of station move. The period of supervision in which a supervisor must have observed the work of a subordinate for rater qualification purposes has gone from 60 to 120 days, to 90 days and back to 120 days. The relationship of the rater to the ratee have shifted from the officer in charge of career development in 1952 to the immediate supervisor in 1954. In addition, at various points the rank of the rater and of the indorser relative to the ratee has been variously controlled and uncontrolled. The number of top blocks which could constitute an outstanding overall rating has for psychological reasons, alternated between I block and 3. One top block supposedly sent the message that most officers should fall in the "middle of the pack." Three top blocks were thought to encourage greater differentiation. In 1960 the "9-4"system was begun. The 9-4 system continued to use the overall 9 point scale evaluation from previous systems but added to it a requirement to rate promotion potential on a scale from I to 4. Initially, the 9-4 system did bring some discipline to the ratings but eventually the ratings became "firewalled" at the top score of 9-4. This inflation occurred even with an extensive educationai program to warn evaluators against rating inflation. By 1968 ratings inflation had once again rendered the OER system ineffective. Nine out of ten officers received the highest rating, 9-4. Development work on a new system began in 1968 and continued through 1974 when the controlled OER came into being. During this six year period four major designs were put forth as collaborative efforts of the Air Force Human Resources Laboratory, industry, universities, government laboratories, foreign military services, the other Armed Services, the Air University, and the Air Staff. 1-4

- 17. PHASE 5: 1974-1978 In 1974 the controlled OER era began. The basic form of the previous OER was retained but raters were instructed to distribute their ratings as follows: 50% in the 1st and 2nd blocks (two highest) with a limit of 22% in the highest block. Although the system had been extensively discussed and pretested prior to implementation, it encountered almost immediate resistance. The basic problem with the controlled OER was that officers who were experienced in a system that gave top marks on just about all evaluations understandably resisted a system where top marks became the exception. Perceptions centered about the notion that a *3" rating was the end of an upward career track in the Air Force. Although educational efforts were made to overcome such misgivings and ultimately only the top block was controlled, the initial anxiety about the system was never overcome. In 1978 the controlled OER era ended when the Air Force leadership decided that individual need for a less stressful OER system was more important than the management benefits of differentiation. PHASE 6: 1978-PRESENT Since 1978, the OER has retained performance factors, narrative comment, and promotion potential ratings. The majority of ratings are again "firewalled* to the top blocks and the discriminating factor has become the rank of the indorsing official and the words in his/her narrative remarks. Table I-I shows various characteristics of the OER since 1947. I-5

- 18. *d a 0 06 C ao6 6 .- tnCL 05 C4 06' C6 V) > IL) v V ) 4 v: u 0. 0 CIS, ISJ 1- z u. w 3 3 3 0-3- <g 1-6 Li. L

- 19. V 00 4.. LD .'o V* V) 0,; 51~~~ *OEV. oL~ 06 o. C1 . CA a in. a a a a a CA 0-0 3 cm~( E -o 0 0(66- 0. 2 U V C) 0 & C1-

- 20. V ;I- I 0... . . . I u C: .il.• --.- • • .

- 21. PROJECT OBJECTIVES & TASKING The Air Force leadership is concerned that the OER has again become less than effective for its intended purposes. Some of the features which have been observed to be deficient and which an acceptable revision should possess are: 1) focuses on the officer', current job performance, 2) provides good differentiation among officers on potential for promotion and for successfully executing higher responsibility, and 3) provides some vehicle for giving officers feedba,.k on their performance to support career development and counseling. In order to achieve these goals, the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel directed that a study of the OER be performed, to result in recommendations for an improved Air Force OER system and for its implementation. Three groups were tasked to perform this study. The first of these groups is composed of active duty and retired senior Air Force officers and is based at Randolph AFB, Texas. The second group is composed of twelve students at the Air Force Command and Staff College at Maxwell AFB, Alabama. They conducted their study as a class project. The Syllogistics/Hay team is the final study group. This team was chosen to provide an independent, outside view of the officer evaluation issue and to apply the expertise of the private sector to the solution of the problems. This study is thL basis of this effort. The Syllogistics-Hay team was specifically tasked to study the current Air Force Officer Evaluation Report piocess to determine its strengths and weaknesses, to apply their knowledge of available methods for performance appraisal, and to develop one or more conceptual designs for an improved OER process and recommendations for the implementation of the design(s). 1-9

- 22. SECTION 1I METHOD The study was carried out in five major phases: 1) a study of the background of the officer evaluation process in the Air Force, including review of documentation and briefings by Air Force personnel; 2) the field data gathering phase, which included interviews and focus group discussions; 3) a review of performance appraisal from non- Air Force sources; 4) the analysis of the data; and 5) synthesis of options and recommendations. Each of these phases will be described in some detail in the following sections. PHASE 1: BACKGROUND STUDY At the outset of the study, the Air Force provided a briefing to contractor personnel, covering several aspects of the OER, its purposes and the process by which it is completed. The briefing described the current officer evaluation report form and its evolution through the history of the Air Force, with information on the lessons learned as each change was implemented. It described the philosophy of officer evaluation, as it has evolved, and the difficulties which have recurred through time, especially inflation of ratings and "gaming" of the evaluation system. At the contractor's request, an additional briefing was provided, covering the Air Force promotion system and its interaction with officer evaluation. This briefing provided valuable background on the operation of promotion boards, on the use of the OER in promotion decisions, and on the officer force structure and factors affecting promotion opportunities. Copies of briefing materials, as well as pertinent reports, Air Force regulations and other publications were provided to the contractors. Contractor personnel carefully I1-1I

- 23. reviewed these materials. This was an essential step in the preparation for the next study phase, the gathering of data from Air Force personnel and others. PHASE 2: DATA GATHERING The data gathering phase of the study had four components. The first was personal interviews with individual Air Force officers who are highly knowledgeable of the personnel policies and procedures relating to officer evaluation. These officers ranged from general officers in command and policy-making positions to mid-level officers responsible for administration of the OER system. In each case, an interview guide (see Appendix D) was used to direct the discussion and to ensure coverage of points which the contractors had determined to be of major importance to t!•I• study. Notes were taken in all interviews for later analysis by the study team. All interviews were conducted by senior team members with extensive experience and expertise in interview techniques. The interviews ranged in length from one to three hours. A list of the officers interviewed is displayed at page D-2. The second data gathering component was the convening of focus groups of six to eight Air Force officers each to discuss the OER process. The nine groups included ranks from lieutenant to major general, but each group was composed of officers of similar rank (e.g., lieutenants and junior captains, lieutenant colonels and colonels). Some groups included only rated officers or only support officers, while others were mixed. A list of the groups, their location, and composition is given in Table II-I. 11-2

- 24. TABLE i!-1 FOCUS GROUPS IDENTIFICATION Group No. Location Ranks Other Information I Randolph AFB General Promotion Board Officers Members 2 Pentagon Colonel All Air Staff; mixed Rated/Non-rated 3 Randolph AFB Lt/Junior Capt Non-rated; support 4 Charleston AFB Lt/Junior Capt Rated; operations 5 Randolph AFB Sr Capt/Maj Rated: operations 6 Randolph AFB Sr Capt/Maj Nonrated; support 7 Randolph AFB Maj/LtCol Rated; operations 8 Charleston AFB Maj/LtCol Non-rated; support 9 Randolph AFB LtCol Mixed rated/non- rated; ops/support Each focus group was conducted by two contractor personnel, with additional personnel present as recorders at most sessions. One of the two served as chief facilitator and led the group discussion with the aid of a discussion guide (see Appendix D). The second facilitator was less active, entering the discussion only infrequently, and assisting in maintaining the focus of the session. The Air Force personnel in the groups were informed of the purposes and method of the study at the beginning of each session and were encouraged to be honest and open. The contractor's goal in these groups was to elicit information, not only on the operation of the OER system, but more importantly on how officers feel about the process and how it affects their careen. Each focus group met for approximately one and one-half to two hours. The third component of the data gathering effort was a series of interviews with persons responsible foi administering officer evaluation systems of the U.S. military services other than the Air Force and of the U.S. Department of State and the Canadian 11-3

- 25. Armed Forces. These interviews were conducted to learn about details of the officer performance evaluation systems of these services. The interviews focused upon identifying the ways in which these systems differ from the Air Force OER system and the significance of such differences. Each respondent was asked about specific strengths and weaknesses of the system which he/she administered, and most respondents provided documentation on their systems. The fourth data gathering component was a series of telephone interviews with representatives of major .orporations which have active management performance appraisal programs. These interviews were conducted to obtain information on current private sector performance evaluation practices. Fourteen interviews were completed, using an interview guide (see Appendix C) to ensure that all major points were covered. The interviews were performed by persons with expertise in private sector performance evaluation issues. PHASE 3: LITERATURE REVIEW In addition to the study of the background materials provided by the Air Force, the contractors searched and reviewed z large sample of historical and current literature on performance appraisal. Textbooks and review articles were used for an overview of "Otraditional" performance appraisal methods, anrl for information on the salient features of each of these methods. Special attention was given to cuirent research literature, with the goal of identifying and evaluating currently popular appraisal methods and systems. This literature was reviewed selectively, with emphasis on issues and methods which appeared especially relevant to the needs of the Air Force. 11-4

- 26. PHASE 4: DATA ANALYSIS The data analysis effort included several elements, some of them performed concurrently. Since the literature review analysis produced a conceptual framework within which other information was analyzed, it will be discussed first. The literature review findings were analyzed and organized in several ways. First, the information was searched to determine major features which are common to all or most performance appraisal systems. These features were listed and used in the analysis of data from other sources (see below). The study team also developed a taxonomy of performunce appraisal systems, based on what is evaluated, what measures are used, and the techniques by which the measures are applied. The next step was to identify in the literature a consensus on the , •,-ionship between organizational characteristics and performance appraisal methods. This resulted in a number of principles relating organizational characteristics to the categories of appraisal methods which have been found to be appropriate to them. The material from the briefings and documents provided by the Air Force was reviewed to extract major recurring themes or issues. These issues were listed and classified for use when evaluating alternative proposals for changes to the OER process. Those issues which emerged as most important were also compared with the data gathered in interviews and focus groups, (i.e., Are the historically important issues still seen as important by current officers?) The notes from interviews with Air Force personnel and from the Air Force focus groups were analyzed to determine major issues. A capsule description of each issue was prepared, and where specific issues could be identified with particular IN-

- 27. population groups, this was done. Certain issues, for example, were of concern more to rated than to non-rated officers; others were more salient to junior officers than to senior officers. The issues were categorized into groups according to their content or area of reference, for example, issues relating to the OER form, to the OER process, to the matter of control of rating distributioiks. The study team was careful to document the perceived strengths cf the present system as well as its perceived weaknesses. The study team also noted its impressions of Air Forcc cultural and organizational characteristics which interact with the OER process, since these are of great importance in determining the acceptability and feasibility of any proposed changes to the OER process. The data from interviews with the other services and departments were reviewed and analyzed to extract major features of each performance appraisal system. A comparison matrix was prepared to facilitate understanding of these systems and of their similarities and differences. These systems were also examined to determine how each deals with the issues which had been found to be of greatest importance to the Air Force. The information gathered by telephone interview from large corporations .vas subjected to an analysis similar to that used for the other military services, Major features of each corporation's performance appraisal system were extracted, and a matrix was prepared comparing the features across companies. PHASE 5: SYNTHESIS OF RECOMMENDATIONS Upon completion of the data analysis, the study team began developing conceptual designs for improving the Air Force OER process. This involved careful consideration of the ;.riteria which had teen developed for a successful OER, the practical considerations wi'hich had emerged in the analysis phase, and the knowledge 11-6

- 28. -gained from the literature and from other organizations concerning the feasibility and effectiveness of various potential solutions to the problems we had identified. Several preliminary OER designs were outlined, and their salient features were listed. These features were then discussed during interviews with 20 Air Force officers of various ranks, many of whom administer OER processing for their commands or activities, to obtain feedback on the value and feasibility of each feature. The feedback interview results were tabulated and analyzed, and decisions were made by the study team about features to be retained and those to be discarded or revised. The preliminary alternative conceptual designs were then revised into final recommended conceptual designs for presentation at the final briefing and in this final report. "1-7

- 29. SECTION III FINDINGS ON PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL IN NON-AIR FORCE ORGANIZATIONS This section gives the findings about performance appraisal in non-Air Force organizations. These were collected from a review of the performance appraisal literature, interviews with fourteen private sector organizations, and interviews with officials from the other armed services as well as the Department of State. PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL: FINDINGS FROM THE LITERATURE A literature search was conducted during the project with two purposes in mind. First, we wanted to determine recent trends and developments in the field of performance appraisal. Second, we hoped to cull from the literature an indication of standard elements for a performance appraisal system which could be used in our analysis of, and deliberations over, alternative OER designs. In addressing these two purposes, this section is organized into four parts. The first part, Survey and Background, discusses the available liteiature and gives the historical development and current position of performance appraisal. The second part, Standards, offers a set of standards for all performance appraisal systems and discusses typical errors in appraisal. This part also includes a discussion of the components of any performance appraisal system. The third part, Afethods, describes the primary forms of performance appraisal with the emphasis on subjective methods and compares these methods. The fourth part, Implications, offers some conclusions from the literature search and their implications for the Air Force's inquiry into alternative OER designs. Ill-I

- 30. SURVEY AND BACKGROUND The literature on performance appraisal is both extensive and diverse, and touches on many side issues such as motivation, job satisfaction, equity, etc. The bulk of the literature focuses on different aspects of documentable performance measures, a focus which is understandable due to the legal requirements of Equal Employment Opportuvity legislation. At the same time, an irea that is somewhat lacking in treatment is that which pertains to such broad organizational issues as the practical and meaningful implementation of performance appraisal within an organization and the matching of performance appraisal techniques with performance appraisal purposes. Rating scales, as a performance appraisal technique, have been in use at least since the 1920s. Although several newer techniques have been introduced, rating scales still predominate. Much has been written about Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scales (BARS), but the developmental costs appear to outweigh the advanta;es associated with the technique. The use of outcome-oriented techniques, such e. rna~.gement-by- objective, as a performance appraisal method is increas.!_g in Popularity as a management tool, but there is some indication that its popularity for appraisal purposes may be fading. The thrust of the literature search was on current literature which for our purposes was 1985 to the present. Certain standard texts were also used, primarily for the Methods section. These were Qrstpizntional Behavior and Personnel Psvchologv by Wexley and Yukl (1977); Personnel: A Diaanostic Aooroach by Glueck (1978); and, finally, Anolied Psycholoav in Personnel Manaaement by Cascio (1982). Performance appraisal, evaluation, or, as it is alternatively callpd, employee proficiency measurement, is generally defined as 'the assessment of how well an 111-2

- 31. employee is doing in his/her job" (Eichel and Bender, 1984). The activity of assessing job performance is certainly widespread in the United States. A Bureau of National Affairs (BNA) study in 1974, for example, found that three-fourths of supervisors, office workers, and middle managers have their performance evaluated annually. A second BNA study (BNA 1975) showed that 54% of blue collar workers participate in performance appraisal. How these assessments are used by organizations, however, varies widely and has shifted noticeably over time. Before 1960, performance appraisals were used by most organizations to justify administrative decisions concerning salary levels, retention, discharges, or promotions. In the 1960s, the purpose of performance appraisal grew to include employee development and organizational planning (Brinkerhoff and Kanter, 1980). In the 1970s, requirements of the Equal Employment Opportunity laws caused organizations to formalize performance appraisal requirements in order to justify salary, promotion, and retention decisions (Beacham, 1979). Currently, performance appraisal is used primarily for compensation decisions and often for counseling and training development. Performance appraisal is used less frequently as a basis for promotion, manpower planning, retention/dischaige, and validation of selection techniques. (Eichel and Bender, 1984; Hay Associates, 1975; Locker and Teel, 1977). Although performance appraisal is widely practiced, the activity is still usually regarded "as a nuisance at best and a necessary evil at worst' (Lazer and Wikstrom, 1977). This attitude towards performance appraisal seems to be held often by both evaluator and evaluatee. Schneier, Beatty, and Baird (1986) note that the requirements of performance appraisal systems often clash with the realities of organizational culture and of managerial work. For example, a manager often has an interest in taking decisive action whereas the performance appraisal may have ambiguous, indirect results. 111-3

- 32. Employee attitudes toward organizational pron .tional systems have also been found to be negative. In one study of such attitudes it was found that respondents believed that personality was the most significant factor in career advancement and that promotion decisions were usually made subjectively and arbitrarily by superiors (Tarnowieski, 1973). Regardless of the perceptions, performance appraisal is a necessary organizational activity. The following sections describe the current state of this activity. STANDARDS OF PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL Whatever performance appraisal system is used, there are certain standards which the system should meet. The literature identifies five such categories of criteria, narrely: legality, validity, reliability, acceptability, and practicality (i.e., cost and time). Thc, categories are closely related and must be defined in relation to one another. Luality refers to the legal requirements for performance appraisal systems, which are the same as for any selection test in that they stipulate that the performance appraisal system be valid and reliable. Validity, in turn, refers to the extent to which an instrument or method measures what it purports to measure. For example, an organization decides to evaluate an employee's performance. If the goal of the performance appraisal is selection for promotion then the performance factors to be evaluated must be selected based on an idea of what will be successful performance indicators for the next level position. This evaluation would not be valid unless it could be demonstrated that success in the selected factors was a predictor of success in the job to which the employee was being promoted. Apart from legal implications, it must be noted that the idea of validity is important at the more elementary level of organizational planning as well. If the organization were to evaluate job performance for developmental purposes then the 111-4

- 33. evaluation must be designed to identify individual strengths and weaknesses and must incorporate a vehicle for communicating this information between the rater and ratee. The third criterion, reliability, is the extent to which a personnel measurement instrument provides a consistent measure of some phenomenon. For example, given the assumption that a person's skills do not change, an instrument which measures skills repeatedly would be reliable only if it repeatedly produced approximately the same scores. The fourth criterion, aa biity, refers to a system's having to be acceptable to both evaluators and evaluatees. By acceptable, we mean that the system be perceived as fair and supportable within the organizational culture. Findings from one study of middle-level managers indicate that the procedures by which appraisals were made seemed to affect the perception of fairness to the same degree as the ratings themselves (Greenberg, 1986). This study also found that procedures that give employees input to the performance appraisalsystem are seen as being fairer than those that do not. The issue of acceptability must be considered whenever there is an attempt to introduce a new appraisal system into an established organization. No matter how well- designed an appraisal system is from a technical standpoint, it is not likely to be effective if it requires behaviors which are incompatible with the customs and expectations of the organization's members. A well-designed and well-implemented program of education and training may improve the acceptability of any appraisal system, but it will not overcome a fundamental mismatch between the appraisal method and the corporate values or culture. Finally, the criterion of Draicafity refers to the requirement that the performance appraisal system should be fairly simple to administer and reasonable in terms of time required and cost of development. 111-5

- 34. Problems of Performance Annralsals Although these standards could go a long way in promoting the integrity of performance appraisal systems, there are still typical, almost unavoidable errors made in the performance appraisal process due to the subjective nature of most measurement techniques combined with the proclivities of the raters. Among these are central tendency errors, "halo" effects, contrast effects, similarity-to-self errors and opportunity bias. Central tendency error is the propensity to grade performance at an average point on a scale rather than rate at the very high or very low end. Leniency and strictness are different manifestations of the same theme -- leniency being defined as the tendency to constantly rate at the higher end of the scale and strictness the reverse. A second common difficulty is referred to as the "halo" effect. The halo effect occurs when an evaluator assesses all factors based on the evaluator's own feelings about one or more factors of performance, rather than assessing each factor objectively. Halo effect can be reduced either by changing the sequence in which the evaluator rates performance factors or by making the performance factors more specific. Contrast effects occur when a person is evaluated against other people rather than against the requirements of a job. For example, three people are up for a promotion, one average and two less than average performers. The evaluator promotes the average performer because he or sh,. looks better in contrast to the other two candidates, not because he/she is necessarily qualified for the promotion. Similarity-to-self error occurs when an evaluator rates a person based on the evaluator's (often unconscious) perception of how similar that person is to him- or herself. This similarity could be in terms of job experience, educational background, 111-6

- 35. personal preferences, etc. Once again, the evaluator is not using a job related criterion to make his/her rating decision. Opportunity bias is a rating error which can manifest itself in two ways. The first is when objective data which may or may not be job related are used in an evaluation. Such objective dath could be absenteeism, tardiness, sick leave, etc. These data are objective and readily available, but may be over-emphasized relative to other aspects of the job which are unable to be measured objectively. The second way in which opportunity bias occurs is often associated with evaluations for employees of field offices, remote sites, etc., by headquarters personnel. In this manifestation, the evaluator tends to downgrade the field personnel because their work is not visible to the evA!uator. Components of Performance Annpra1sPl Prior to discussing specific methods of performance appraisal, the actual components of the performance appraisal system need to be identified. These include goals, methods of performance appraisal, indicators of performance, schedule of appraisals, znd evaluators. •.gJj. The goal or purpose of performance appraisal is usually either to support the administrative needs of the organization or to facilitate individual employee development. The goal of the performance appraisal should drive the type of performance appraisal system used and the type of performance information collected. For example, the primary administrative uses of performance appraisal are for compensation and promotion decisions. One would assume, then, that an organization would make these decisions based on assessment of current performance and would choose a performance appraisal method which would provide that information. The same idea would hold for the organization whose performance appraisal goal is employee 111-7

- 36. development. The method chosen in this case should give an indication of employee strengths and weaknesses. There is indication in the literature that performance appraisal for multiple purposes which include development tends :o fail on the development side. One important study showed that employees became defensive about performance counseling when a compensation decision was dependent on a favorable rating (Meyer, Kay & French, 1965). For this reason some authors argue for separate performance appraisal systems for different purposes or at least for separating the counseling session in time from the formal evaluation. Methods. Methods of performance appraisal can be categorized as objective and subjective methods for purposes of broad differentiation. Subjective methods, on the one hand, rely on the opinion of an individual or several individuals regarding an employee's performance. Most often subjective methods use some sort of scaling device to record these opinions concerning specified performance factors. There is tremendous variation in these techniques, mainly in the degree of accuracy attempted by the scale. Objective methods, on the other hand, use direct measures to rate employees. Such direct measures can be either rates of production, personnel statistics (e.g., absence rates, sick days) accomplishment or non-accomplishment of specified performance objectives or test scores. Objective methods are generally used with employees whose jobs are repetitive or production-oriented. Objective measures carry the obvious advantage of not being dependent on evaluator judgment. However, they may not be as useful to many organizations as subjective measures because they often reflect outcomes which may not provide the total, or most important, picture of an individual's performance. In 111-8

- 37. addition, they frequently fail to provide a means for comparison of performance among employees. Finally, it is occasionally the case that plausible objective performance measures simply cannot be devised for a particular job. Practical considerations usually limit the use of objective techniques, although it is important to note that objective information can be helpful in supporting subjective ratings, even when correlations between subjective and objective ratings are low (Cascio & Valenzi, 1978). Taylor and Zawacki (1984) categorized methods as traditional (i.e., use of quantitative or statistical tools along with judgment by an evaluator to evaluate performance) or collaborative (i.e., use of some form of joint, evaluator-evaluatee, goal- setting technique related to performance.) In a study of Fortune 500 companies, these authors found that collaborative designs brought about improvements in employee attitudes more often than traditional designs. They also found that, although more companies were satisfied with collaborative than with traditional designs, there was a general shift in usage to traditional designs, perhaps due to legal requirements for precise measurement. In another study of the effects of goal-setting on the performance of scientists and engineers, nine groups were formed which varied goal setting strategies (assigned goals; participatively set goals; and "do your best") and recognition vehicles (i.e., praise, public recognition, bonus) (Latham & Wexley, 1982). Those in the groups which set goals, either assigned or participatively.had higher performance than those in the "do your best' group. In addition, it was found that those in the participative group set harder goals and had performance increases which were significantly higher than the other two goal-setting categories, Indiisiira. Indicators of performance can b- behaviors displayed by employees, tangible results of employees performance, and/or ratings on employee traits or qualities (e.g., leadership, initiative). 111-9

- 38. There is consensus in the literature that traits are not the preferred performance indicators. Traits are difficult to define and therefore can lead to ambiguity and poor inter-rater reliability. Trait rating may also not be helpful from a developmental position as it is hard to counsel employees, for example, on "drive'. Finally, a trait- oriented appraisal is likely to be rejected by the courts (Latham & Wexley, 1982). It is difficult to show, first, that a trait has been validly and objectively measured, and second, that a particular trait is a valid indicator of job performance level. Behavioral indicators can be shown through job analysis to be valid measures of performance. Research on these indicators suggests that rating both behaviors and results is the best course of action (Porter, Lawler & Hackman, 1975). Schedule of the Apnralsal. Most organizations appraise performance annually, usually for administrative convenience. S6nedules are often based on employee anniversary dates with the organization, seasonal business cycles, etc. Appraisals scheduled once a year solely for administrative convenience are difficult to defend from a motivational viewpoint, since feedback is more effective if it immediately follows performance (Cook, 1968). In addition, if all appraisals are conducted at one time then managers have an enormous workload, although the annual dates for all employees need not coincide. Variable schedules for appraisals can be used when there are significant variations in an employee's behavior, although problems with this idea can include inconvenience and lack of consensus over what should constitute "*significantvariation.' Evaluatoil. An evaluator can be the employee's immediate supervisor, several supervisors, subordinates, peers, outside specialists or the employee him/herself. In a study by Lazer & Wikstrom (1977), the employee's immediate supervisor was found to be the evaluator for lower and middle management in 95% and for top Ill-10

- 39. management in 86% of companies surveyed. Use of the immediate supervisor as the evaluator is generally based on the belief that the supervisor is the most familiar with an individual's performance and therefore the best able to make the assessment. Several supervisors can be used to make the appraisal, a method which has the possibility of balancing any individual bias. Eichel and Bender's study (1984) shows that in 63% of the responding companies another supervisor would join in the appraisal in some way. Another study (Cummings and Schwab, 1973) showed however, that an evaluation by a trained supervisor was as effective as by a typical rating committee. In any event, the research on the effectiveness of joint appraisal by several supervisors is sparse and inconclusive. Peer evaluation, although rarely used, consistently meets acceptabie standards of reliability and is among the best predictors of performance in subsequent jobs. Also, peer appraisals made after a short period of acquaiutance are as reliable as those made after a longer period (Gordon A Medland, 1965; Korman, 1968; Hollander, 1965). Peer evaluations may not be used extensively because peer. are often reluctant to ac! as evaluators or to be evaluated by their peers, supervisors may not want to relinquish their managerial input to evaluation, and it may be difficult to identify an appropriate peer group. Outside specialists can be brought in to conduc: appraisals but this is rare. The assessment center technique incorporates outside personnel but this technique is often expensive in terms of time and manpower. Use of outside specialists was so infrequent that it was not even reported in the 1975 BNA study. Self evaluation in the form of either formal or informal input to the appraisal process was reported in three out of four responding companies in Eichel and Bender's survey (Eichel & Bender, 1984). Several studies which compared self and sup- visory Ill-I I

- 40. assessments showed low agreement between the two techniques (Meyer, 1980). Self assessment appears to be used primarily for employee development purposes, while supervisory assessment is used mainly for evaluative purposes. The role of the evaluator is key in most performance appraisal systems, because most performance appraisal systems rely on the judgment of the evaluator. On this point the literature supports the idea that evaluator training can be effective in reducing evaluator error, such as 'halo', especially if the training includes practice (Landy & Farr, 1980). Within the context of these components of any performance appraisal, specific methods of appraisal are described next. METHODS As discussed in the previous section, methods for performance appraisal can be divided into objective or subjective. An overview of methods is described below with the subjective methods first. Appendix B offers a more complete discussion of each technique along with sample forms. Sublective Methods Nine subjective performance appraisal methods are identified in the literature, including: ,l*atlj._ScaIle. These have been and continue to be the most popular forms of performance appraisal. In this method, the evaluator is asked to score an employee on some characteristic<s) on a graphic scale. Characteristics can be personal traits such as drive, loyalty, enthusiasm, etc., or they can be performance factors such as application of job knowledge, time management, and decision-makitg. Scoring is sometimes left completely to the judgment of the evaluator; alternatively, standards can be developed II1-12

- 41. which give examples of wa xt should constitute a particular score on the trait or performance factor. The scale on which the factor is scored may be a continuous line or in the multiple step variation the evaluator may be forced to score in discrete boxi;s. The widespread use of rating scales is probably attributable to administrative convenience and applicability across jobs. In their simplest forms, however, rating scales are prone to many types of evaluator bias. Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scales, or BARS, were developed to address this problem. BARS provide specific behavioral examples of "good" performance or "poor" performance developed and validated by supervisors for a particular job. The use of behavioral examples precludes much of the ambiguity of such descriptors as "exceptional". BARS, once developed, are fairly easy to use and can provide the employee with rather specific feedback. BARS are very expensive to develop and usually are constructed for each specific job. There seems to be some consensus that on a job by job basis the expense may be outweigh the value. Their most appropriate application is for very high density jobs such as telephone operators. CJjcklijzj. In this method the evaluator is given a list of behavioral statements and asked to indicate or check whether he/she has observed the evaluated employee exhibiting these behaviors. A rating score is obtained by totaling the checks. Weighted checklists also use behavioral statements, but weights have been developed for each statement which correspond to some numerical point on a scale from poor to excellent. Evaluators indicate presence or absence of each behavior without knowledge of associated scores. The evaluatee's final score is obtained by averaging the weights of all items checked. i11- 13

- 42. Eorced Choice. The forced choice method was developed during World War II by industrial psychologists as a means of reducing bias in the ratings of Army officers. In this technique groups of statements are developed and grouped, two favorable and two unfavorable per group. The evaluator is asked to pick from each group of four statements which are most and least descriptive of the employee being rated. One statement in each group is actually a discriminator of effective and ineffective behavior. The other statements are not. The rater does not know which statements are the discriminators and which are not. Scoring is done separately, usually by the personnel -department. The obvious advantage of this technique is that the system, properly constructed, should reduce subjectivity. However, evaluators are often reluctant to use the method because they don't know how they are rating employees. In addition, considerable time is required to develop the discriminating statements properly. Finally, the system does not effectively support employee development needs. Critical Incident. Like checklists, the critical incident technique involves preparing statements which describe employee behaviors. These statements, however, describe very effective or successful behaviors. Supervisors then keep a record during the rating period indicating if and when the employee exhibits these behaviors. This record can be used during the appraisal interview to discuss specific events with employees. The critical incident technique can be very effective for development purposes, but is not as useful for compensation or promotion decisions. Forced Distribution. The forced distribution method asks the evaluator to rate employees in some fixed distribution of categories, such as 20 percent poor, 50 percent average, and so forth. This distribution can be done in sequence for different purposes, i.e., job performance and promotion potential. This technique is administratively simple, but there are several disadvantages to the use of a forced distribution. It is not useful in III- 1

- 43. providing feedback to the ratee on his/her performance for use in developmental counseling. It often encounters resistance from the raters, who are uncomfortable assigning large numbers of subordinates to categories which are less than favorable. The use of forced distributions where the ratings of multiple groups must be combined may also lead to problems, because the groups may not all be seen as of equal "quality" by raters and ratees. For example, is an average performance in a highly selected work group the same as an average performance in a less elite group? If not, how can the difference be equitably dealt with in the system? Forced distribution is usually done to control ratings and to limit inflation. Bnaal.fja. Ranking involves simply rating employees from highest to lowest against some criterion. The method carries about the same advantages and disadvantages as forced distribution but is harder to do as the group size increases. Ranking also does not allow valid comparison across groups unless the groups share some of the individuals in common. Paired Comnarison. The paired comparison is a more structured ranking technique. Each employee is systematically compared one on one against each other employee in a defined group on some global criterion, such as ability to do the j.. When all employees in the group have been scored, the number of times an employee is preferred becomes, in effect, his/her score. This method gives a straightforward ordering of employees; however, it does not yield information which might be helpful for employee development. Paired comparison, like ranking, does not allow comparison across groups. Fie.ldRyle. The field review approach uses an outside specialist, often someone from the personnel department, to conduct the evaluation. Both the manager and the subordinate are questioned about the subordinates' performance, then the specialist prepares the appraisal with managerial concurrence. The major advantage of 111-15

- 44. the field review technique is that it reduces managerial time in the appraisal system and may provide more standardization in the appraisal s. Managers may, however, delegate all the appraisal functioa to the personnel office when in practice the technique is designed to be a collaborative effort. Essay Evaluatign. In t-is technique the evaluator writes an ebsay about the employee's performance. The essay is usually directed, that is, certain aspects of the employee's behavior must be discussed. Essays are often used in conjunction with graphic rating scales to explain a score. One disadvantage of this approach is that the writing ability of the rater can influence the employee's final rating if the evaluation is passed through the organizational hierarchy. Oblective Methods Objective methods do not rely on the judgment of an evaluator aid usually involve capturing direct information about an employee's proficiency or personal work statistics such as tardiness, etc. Objective methods are usually restricted to production oriented and repetitive jobs although they are also applied to jobs which are responsible for sales, profit or other objective outcomes. Even though objective methods may not rely on subjective judgments, they are still not a panacea for performance appraisal for the jobs where they are applicable. This is because the objective data is most relevant to the assessment of current performance, but probably could not stand alone as a performance appraisal technique for promotion or development purposes. Judgment as to the relevance of the data still adds a level of subjectivity which is impossible to avoid. Two objective methods, proficiency testing and measurement against production standards are discussed below. 1II- 16

- 45. Proficlency Tests. Proficiency tests measure the proficiency of employees at doing work and are basically simulations of the work a job entails. Typing tests and assessment center simulation are examples of this technique. Written tests can also be used to measure the employee's job related knowledge. One disadvantage of the testing technique, in addition to those given generally above, is that some people are more anxious during a testing situation than in an actual work situation, and these people will be at a disadvantage if their anxiety affects their performance. A second disadvantage is that proficiency tests tend to measure what -an be done as opposed to what is done daily on the job. For example, lack of motivation on the job may not be reflected in the test scores. Measurement Against Production Standards. Production standards are levels of output which reasonably can be expected from an employee within a given amount of time. Standards can be set through sophisticated industrial engineering techniques or they can be as simple as the average output of all employees in the given time. In any event, an employee's actual performance can then be measured against the standard rather than against other employees. OtherLMthod Management By Objective (MBO. MBO, which can be a goal oriented management tool, can be used either separately or simultaneously as a performance appraisal technique. When MBO is used as a nerformance appraisal technique, the supervisor and subordinate usually establish performance objectives, often in quantitative terms, for the rating period. At the end of the rating period, actual performance is compared to the objectives and scored. In an intuitive sense MBO is very appealing as a technique for performance appraisal as it appears straightforward, can be used to convey broad organizational goals, and usually has a quantitative orientation. Many

- 46. organizations have adopted MBO or some form of goal setting for appraisal purposes, possibly for these reasons (Kane & Freeman, 1986, Eichel & Bender, 1984). MBO as a performance appraisal technique is relatively new and therefore has not been studied extensively (for that purpose). The literature does indicate, however, some areas where MBO can be troublesome. MBO can be difficult as an appraisal technique if the appraisal is for promotion purposes; because MBO does not provide relative performance indicators (French, 1984). A second possible problem is that MBO tends to focus on goals which can be quantified: production rate, return on investment. etc. Such quantitative goals often do not include or address causal issues such as leadership, judgment, etc. In addition quantitative organizational goals are rarely the result of the performance of an individual. Thus, the appraisal may incorporate factors beyond the control of the individual. For whatever reason, the literature indicates that MBO and, to some extent, goal setting as a performance appraisal technique may be decreasing in popularity (Schuster & Kindall, 1974; Kane & Freeman, 1986; Taylor & Zawacki, 1984). Comnarison of Methods Table 111-1 compares the various performance appraisal methods by purpose or goal of the performance appraisal and by cost in terms of development and usage. Examination of this table shows that there is no one method which would satisfy all three purposes: development, compensation allocation, and promotion. It also shows that costs associated with various systems vary primarily as a function of the amount of information which must be collected or developed. Finally, the three employee comparison methods (ranking, paired comparison, and forced distribution) have the particular advantage/diadvntage of being useful for employee comparison within a group, but offering considerable barrier to comparing employees across groups. III-18

- 47. In the next part we will discuss conclusions from the literature and some possible implications for the Air Force. IMPLICATIONS FOR THE AIR FORCE The performance appraisal literature is frustrating in that it tends to dwell more on specific details of certain methods rather than on larger organizational issues. There are, however, some themes which appear relevant to the current OER considerations. The Air Force is a huge and diverse organization which must recruit, train, develop, and retain its desired work force. In addition, through the up or out system, the Air Force must constantly pare away at each class of officers. With these thoughts in mind, the performance appraisal system and the information it can yield to the individual and the organization take on extraordinary importance. It is also clear, however, that attempts to increase accuracy in measurement, fairness in procedure, and information for developmental purposes must be assessed against the administrative realities and practicalities of a very large and somewhat decentralized organization. The idea has been offered that the purpose of the performance appraisal system should drive the type of technique chosen or at least the information collected. The Air Force, like most organizations, uses performance appraisal now for multiple purposes but primarily for promotion. If the OER system is to be effective for the purpose of selection for promotion, then it should focus on that purpose and achieve its other, current purposes through alternative means. A variety of performance appraisal methods was described, classified according to how performance is measured. Examination of these methods suggest that some methods may be more realistic for the Air Force than others. For example, the III- 19

- 48. S0 U, < 0-- o"0 .0.. . io'E 0 0 L z 0: 00 0cZe 0 4i 'Z C 8c • o_,2 .0- a D E . !II- 20

- 49. employee comparison techniques of forced distribution, ranking, and paired comparison could not be used easily for promotion purposes, because once the rankings within a particular group have been established, there is no information to support comparisons across the ranked groups. The problem of equating rankings or distributions across work grouips or commands does not have a simple solution and is one of the issues which contributed to the lack of acceptability of the ;974-1978 controlled distribution system. Critical incident, BARs, and MBO are, or can be, extremely good techniques for employee development purposes. Each technique, however, carries some feature(s) which would seem to conflict with the administrative realities of such a huge organization as the Air Force. For example, BARs involves extensive development resources and a single OER form could not be used across jobs. Critical incident requires the superior to keep a log on each subordinate throughout the rating period. MBO tends to focus on short term quantitative effects and, like ranking, does not provide relative information across people, much less groups. The forced choice method appears to actually distinguish performance but is also associated with user resistance and high developmental costs. Surprisingly, the method which may be the most feasible, given administrative workload and organizational culture, is the traditional graphic rating scale, which, in fact, the Air Force uses now. Rating scales provide relative information, and can be made more or less specific through anchors or standards (such as the Air Force has now). Also the performance factors can be used to transmit the emphasis which the Air Force believes its officer corps should exhibit. The need may be not so much for a new technique to improve the OER system but rather control of the present technique to reduce inflation and improve the quality of performance information evaluated. Currently. the system works with 111-21

- 50. informal controls (such as the indorsement process) or with no controls (the tendency to firewall on the front side of the OER form). One means of controlling the technique is to influence the rater. This could be done by including "evaluation of subordinates" as a performance factor on the OER, by maintaining a history of the ratings given by the rater, or some combination of these. Evaluations can also be improved through rater training. This idea is very important if the Air Force wants to move away from the writing style and content habits currently in use. Raters can be given instruction on the type of behaviors (depending on technique) to be observed as well as on the organizational desire to have some accurate means of distinguishing performance. Thus, the training would be two-pronged, focusing on 1) what and how to rate and 2) the need to rate accurately. The Air Force currently does not include counseling as part of its overall performance appraisal system but has indicated a desire to do so. The literatureseems to indicate that counseling is best done separatelyfrom the formal evaluation. Also, related to counseling, the literature points to participative goal setting as the most useful technique in actually changing employee performance and/or attitudes. Peer evaluation is a promising source of information concerning leadership identification. Peer evaluation seems to be especially applicable in a military setting where groups of people enter together and attend training schools, etc. where such evaluations could be conducted. Peer evaluations should only be used as a supplementary leadership indicator, however, as there is substantial opportunity for personal change over a 12-20 year career. The most fundamental implication appears to be the need for organizational responsibility toward a performance appraisal system. In order to be useful, a 111-22