Asia-Pacific Communication Monitor 2020/2021

- 3. ASIA-PACIFIC COMMUNICATION MONITOR 2020/21 STRATEGIC ISSUES, COMPETENCY DEVELOPMENT, ETHICAL CHALLENGES AND GENDER EQUALITY IN THE COMMUNICATION PROFESSION. RESULTS OF A SURVEY IN 15 COUNTRIES AND TERRITORIES. Jim Macnamara, May O. Lwin, Chun-Ju Flora Hung-Baesecke & Ansgar Zerfass A study organised by the Asia Pacific Association of Communication Directors (APACD) and the European Public Relations Education and Research Association (EUPRERA), partnered with Truescope, Nanyang Technological University, and PRovoke.

- 4. 4 Imprint Published by: APACD Asia-Pacific Association of Communication Directors, Hong Kong, www.apacd.com EUPRERA European Public Relations Education and Research Association, Brussels, www.euprera.org Citation of this publication (APA style): Macnamara, J., Lwin, M. O., Hung-Baesecke, F., & Zerfass, A. (2021). Asia-Pacific Communication Monitor 2020/21. Strategic issues, competency development, ethical challenges and gender equality in the communication profession. Results of a survey in 15 countries and territories. Hong Kong, Brussels: APACD, EUPRERA. Short quotation to be used in legends if using/citing graphics from this report: Source: Asia-Pacific Communication Monitor 2020/21, www.communicationmonitor.asia. Copyright: © March 2021 by the research team (Macnamara, Lwin, Hung-Baesecke, & Zerfass) for the whole document and all parts, charts and data. The material presented in this document represents empirical insights and interpretation by the research team. It is intellectual property subject to international copyright. Title graphic provided by Quadriga Media. Survey tool, previous questionnaires/data, and website domain licensed by EURERA. Permission is granted to quote from the content of this survey and reproduce any graphics, subject to the condition that the source including the internet address is clearly quoted and depicted on every page or chart. It is not allowed to use this data to illustrate promotional material for commercial services. Publishing this PDF document on websites or social media channels run by third parties and storing this document in databases or on platforms which are only open to subscribers/members or charge payments for assessing information is prohibited. Please use a link to the official website www.communicationmonitor.asia instead. This report is available as a free PDF document at www.communicationmonitor.asia. Contact: Please contact the lead researchers or national research team members in your country if your are interested in presentations, workshops, interviews, or further analyses of the insights presented here. Contacts are listed on pages 94-97.

- 5. 5 Content Introduction 6 Research design 8 Methodology and demographics 10 Strategic issues and communication channels 16 Competency development: Status quo and future needs 24 Ethical challenges and resources for the communication profession 42 Assessing and advancing gender equality 62 Characteristics of excellent communication departments 80 References 91 Authors and researcher team 94 National contacts 95 Survey organisers 98 Partners 99 More information 100

- 6. 6 Introduction Welcome to the third Asia-Pacific Communication Monitor. Following its launch in 2015/16 as a bi-annual survey, this study provides valuable understanding of the communication industry in Asia-Pacific today and predictions for its future. The Asia-Pacific Communication Monitor is part of the global Communication Monitor series that now includes the European Communication Monitor; the North America Communication Monitor; and the Latin America Communication Monitor. In all, the Monitor surveys cover more than 80 countries and territories on five continents and represent the views of more than 6,000 communication professionals, making the collectively the largest study of public communication practices worldwide. The global sample of the Communication Monitor also allows comparison of findings across regions to identify commonalities as well as reginal differences in practice. The findings of the Asia-Pacific Communication Monitor 2020 build on those of previous Communication Monitor studies in Asia- Pacific in 2015 (Macnamara, et al., 2015) and 2017 (Macnamara et al., 2017) to show development, trends, and future directions. The 2020/21 Asia-Pacific Communication Monitor findings are based on responses from 1,155 communication professionals in 15 Asia- Pacific countries and territories representing practices in corporations, governmental and non-profit organisations, and communication agencies. This report identifies the major strategic issues facing communication professionals in Asia-Pacific; the main communication channels that they use; and the competency of communication professionals to meet the challenges of today and tomorrow; and its explores the socially important issues of ethics and gender equality. Adequately responding to ethical challenges and advancing gender equality are vital to ensure that public communication is socially responsible and contributes to the ‘social good’, as well as achieving the objectives of organisations. In this report, you will find some unsurprising trends, such as the continuing use and importance of social media, as well as some surprises and findings that warrant discussion among practitioners and industry associations. For example, while women hold the majority of positions in the field, they still lag in appointment to senior management roles. Also, a ‘glass ceiling’ is reported more often in government organisations than non-profits, companies, and agencies. Arguably, governments should be more representative of society and committed to social equity. More than 40% of practitioners reporting facing ethical challenges in their work. In particular, 75% of practitioners are concerned about using bots and big data analysis. With growth in use of data analytics and artificial intelligence (AI), ethical practice in these areas is a matter for close attention in the industry. However, it is concerning that almost one-third of communication professionals in Asia-Pacific have never participated in any ethics training. The lead researchers and authors of this report believe that practitioners, industry organisations, and trainers and educators will find interesting information and insights in this report.

- 7. 7 !"#$%&'(#)%" !"#$%&'()*(+','+$-.//01'+(2'.1$3.1'2.4$'&$.45(1'$78$(1$(+(6#/'+$4#&#(4+"$2#(/$'1$+..9#4(2'.1$:'2"$2"#$%&'() *(+','+$%&&.+'(2'.1$.,$-.//01'+(2'.1$;'4#+2.4&$<%*%-;=$(16$2"#$>04.9#(1$*07?'+$@#?(2'.1&$>60+(2'.1$(16$ @#&#(4+"$%&&.+'(2'.1$<>A*@>@%=B$:"'+"$+..46'1(2#&$2"#$3.1'2.4$&206'#&$5?.7(??8C D.4$2"# EFEFGEH$%&'()*(+','+$-.//01'+(2'.1$3.1'2.4B$:#$(4#$I#48$9?#($2.$"(I#$!40#&+.9#B$2"#$,'4&2$&/(42$ /#6'($'12#??'5#1+#$9?(2,.4/$2"(2$94.I'6#&$4#(?)2'/#$'1,.4/(2'.1$2.$+?'#12&B$(&$.04$/(J.4$9(421#4C$%?&.B$:#$ (+K1.:?#65#$(16$2"(1K$*@.I.K# (&$.04$/#6'($9(421#4B$(16$L(18(15$!#+"1.?.5'+(?$A1'I#4&'28$(&$.04$(+(6#/'+$ 9(421#4C$M##$N*(421#4&O$.1$9(5#$PP$,.4$'1,.4/(2'.1$(7.02$2"#&#$&099.42'15$.45(1'&(2'.1&C Q1$(66'2'.1B$:#$#R2#16$&'1+#4#$2"(1K&$2.$(1$#R2#16#6$4#&#(4+"$2#(/$.,$(+(6#/'+&$(+4.&&$2"#$4#5'.1$:".$ &099.42#6$2"#$+.4#$2#(/$(16$#1&04#6$2"(2$2"#$&04I#8$4#,?#+2&$2"#$6'I#4&'28$.,$2"#$,'#?6$(+4.&&$%&'()*(+','+C$!"#$ #R2#16#6$4#&#(4+"$2#(/$'&$?'&2#6$016#4$NL(2'.1(?$+.12(+2&O$.1$9(5#&$PS)PT$.,$2"'&$4#9.42C U#$(?&.$2"(1K$(??$2"#$+.//01'+(2'.1$94.,#&&'.1(?&$:".$+.124'702#6$2"#'4$I(?0(7?#$2'/#$2.$9(42'+'9(2#$'1$2"'&$ &04I#8C$!"#8$5'I#$%&'()*(+','+$($I.'+#$'1$2"'&$5?.7(?$4#&#(4+"$94.J#+2$(16$+.124'702#$2.$2"#$+.12'10'15$6#I#?.9/#12$ (16$94.,#&&'.1(?'&/$.,$2"#$,'#?6C ! ;'&2'150'&"#6$*4.,#&&.4$V'/$3(+1(/(4( ! *4.,#&&.4$3(8$WC$X:'1 ! ;4C -"01)V0 D?.4($Y015)Z(#&#+K# ! *4.,#&&.4$%1&5(4$[#4,(&& !"#$%&"'"#&()"&'*%+',#-.#(,/,(%012234,(#5,14%614,51&

- 9. 9 Research design The Asia-Pacific Communication Monitor (APCM) is a unique transnational study of strategic communication practice covering 15 countries and territories in the region. Findings are derived from an online survey of communication professionals working in corporations, governmental and non-profit organisations, and communication agencies. The APCM is conducted in collaboration with similar studies in other regions including Europe (Zerfass et al., 2020), North America (Meng et al., 2019) and Latin America (Moreno et al., 2019). With more than 80 countries and territories participating globally using comparable methodology and sharing common questions, the Communication Monitor studies are the most comprehensive research into strategic communication and public relations worldwide. The research framework for the survey is designed to explore five key areas: (1) organisations (their structure and country or territory of operation); (2) communication professionals (their demographics, role, experience, etc.); (3) the situation in which they operate (challenges, competencies, etc.); (4) the communication department (its role, influence and performance); and (5) perceptions of the future (strategic issues, importance of channels, etc.). It examines a number of independent and dependent variables in nine categories outlined in the research framework on page 12. The study explores four constructs. Firstly, developments and dynamics in the field of strategic communication (Falkheimer & Heide, 2018; Holtzhausen & Zerfass, 2015; Nothhaft et al., 2019) and public relations (Tench & Waddington, 2021; Valentini, 2021) are identified by longitudinal comparisons of strategic issues and communication channels. To this end, questions from previous APCM surveys (Macnamara et al., 2015, 2017) have been repeated. Secondly, regional and national differences are revealed by breaking down the results to 11 key countries and territories. Thirdly, a selection of current challenges in the field are empirically tested. The study identifies the frequency of moral challenges and approaches of coping with them generally (Bivins, 2018, Cheney et al., 2011; Parsons, 2016), as well as ethical aspects of digital communication practices specifically (Barbu, 2014; DiStasio & Bortree, 2014). Additional issues explored are the role of women in communication with a specific look on the glass ceiling hindering female practitioners to reach top positions (Dowling, 2017; Topić et al., 2020) and competency development for communicators (Moreno et al., 2017; Tench & Moreno, 2015). Fourthly, statistical methods are used to identify high performing communication departments in the sample (Tench et al., 2017b; Verčič & Zerfass, 2016), and there define which aspects make a difference. The design of the study provides insights to help communication professionals and industry bodies identify strengths and opportunities as well as weaknesses and threats. It also provides empirical findings to inform professional development, undergraduate and postgraduate education, and academic research.

- 11. 11 Methodology and demographics The online questionnaire of the Asia-Pacific Communication Monitor 2020/21 consisted of 32 questions. Five of these questions were only presented to professionals working in communication departments. Instruments used dichotomous, nominal, ordinal and numeric scaling. They were based on research questions and hypotheses derived from previous research and literature. The survey was available in English and Chinese and was activated from September to November 2020. Communication practitioners were invited by e-mail from national research collaborators and professional associations. In addition, e-mail invitations were issued based on a database from the previous APCM editions and another provided by the Asia-Pacific Association of Communication Directors (APACD). The invitations were further publicised by PRovoke Media. In total 2,306 respondents started the survey and 1,236 of them completed it. Answers from participants who could not clearly be identified as part of the population were deleted from the dataset. This strict selection of respondents is a distinct feature of the APCM and sets it apart from many studies which are based on snowball sampling or which include students, academics and people outside of the focused profession or region. The evaluation presented in this report is based on 1,155 fully completed replies by communication professionals. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used for data analysis. Results have been tested for statistical significance with, depending on the variable, Chi², ANOVA / Scheffé Post-hoc-Test, independent samples T-Test, Pearson correlation, Kendall rank correlation or Mann-Whitney U Test. The applied methods are reported in the footnotes. Significant results are marked with * (p ≤ 0.05, significant) or ** (p ≤ 0.01, highly significant) in the graphics or tables and also mentioned in the footnotes. The demographics reveal the high quality of the sample, which is dominated by senior professionals with a sound qualification and a long tenure in the field. The average age is 39.2 years. Two out of three respondents are communication leaders: 23.1 per cent hold a top hierarchical position as head of communication in an organisation or as chief executive officer of a communication consultancy; 34 per cent are unit leaders or in charge of a single discipline in a communication department. 50.7 per cent of the professionals interviewed have more than ten years of experience in communication management. 64.1 per cent of all respondents are female and a vast majority (96.6 per cent) in the sample has an academic degree, half of them even a graduate degree or doctorate (45.1 per cent). Six out of ten respondents work in communication departments in organisations (joint stock companies, 18.4 per cent; private companies, 19.5 per cent; government-owned, public sector, political organisations, 17.7 per cent; non-profit organisations, associations, 5 per cent), while 39.4 per cent are communication consultants working freelance or for agencies. Communication professionals from 15 different countries and territories participated in the survey. Detailed insights were calculated for 11 key markets.

- 12. 12 Research framework and questions Situation Ethical challenges in communication, Q 1 Orientation on ethical challenges, Q 2 New ethical challenges, Q 3 Women in communication, Q 4 Glass ceiling in communication, Q 5 Competencies in communication, Q 9 Importance and personal level of key competencies, Q 10 Development of competencies, Q 11 Communication channels and instruments, Q 12 Person (Communication professional) Demographics Education Job status Professional status Age, Q 21 Gender, Q 22 Academic qualification, Q 29 Position, Q 14 Practices (Areas of work), Q 20 Experience on the job (years), Q 23 Membership in professional association(s), Q 30 Time spent for professional development, Q 24, Q 25 Training in ethics, Q 26, Q 27 Communication department Excellence Influence Performance Advisory influence, Q 16 Executive influence, Q 17 Success, Q 18 Quality & Ability, Q 19 Organisation Structure / Culture Country Type of organisation, Q 13 Alignment of the top communication manager, Q 15 Female top communication leaders and female share of communication staff, Q 28 Country, Q 31, Q 32 Perception Reasons for the glass ceiling, Q 6 Overcoming the glass ceiling, Q 7 Strategic issues, Q 8 Communication channels and instruments, Q 12

- 13. 13 !"#$%&'()*+,-'+.%&$/01,$2,('&3*+*('034 !"#$%$"& !"#$%&'%(&))*+,(#-,&+.%/0"+(1%234 56789 :+,-%;"#$"<.%="#)%;"#$"< 6>7?9 ="#)%)")@"<.%2&+A*;-#+- 6B7>9 4-C"< D7>9 '"()*+,*-$*&.* E&<"%-C#+%8?%1"#<A B?7D9 F%-&%8?%1"#<A 8G7G9 :H%-&%B%1"#<A 6?7B9 /0$1&2*&%)"3)%4*)."225&$.6%$"&)35&.%$"& I-<&+0;1%#;,0+"$%(&))*+,(#-,&+%$"H#<-)"+- 5?7F9 /;,0+"$%(&))*+,(#-,&+%$"H#<-)"+- F87>9 J"#K;1%#;,0+"$%(&))*+,(#-,&+%$"H#<-)"+- 8G7?9 LLL7(&))*+,(#-,&+)&+,-&<7#A,#%M%E#(+#)#<# "-%#;7%5?58%M%+%N%8.8BB%(&))*+,(#-,&+%H<&'"AA,&+#;A7%O%86P%JC"<"%$&%1&*%L&<KQ%O%8>P%JC#-%,A%1&*<%H&A,-,&+Q% O%56P%!&L%)#+1%1"#<A%&'%"RH"<,"+("%$&%1&*%C#S"%,+%(&))*+,(#-,&+%)#+#0")"+-MTUQ%/;,0+)"+-P%+%N%FVV%(&))*+,(#-,&+%H<&'"AA,&+#;A%L&<K,+0%,+% (&))*+,(#-,&+%$"H#<-)"+-A7%O%8BP%J,-C,+%1&*<%&<0#+,A#-,&+.%-C"%-&H%(&))*+,(#-,&+%)#+#0"<%&<%(C,"'%(&))*+,(#-,&+%&'',("<%,A%#%)")@"<%&'%-C"%"R"(*-,S"% @&#<$%M%<"H&<-A%$,<"(-;1%-&%-C"%234%&<%C,0C"A-%$"(,A,&+W)#K"<%&+%-C"%"R"(*-,S"%@&#<$%M%$&"A%+&-%<"H&<-%$,<"(-;1%-&%-C"%234%&<%C,0C"A-%$"(,A,&+W)#K"<7 6>7?9 6B7>9 D7>9 B?7D9 8G7G9 6?7B9 /0$1&2*&%)"3)%4*)."225&$.6%$"&)35&.%$"& 5?7F9 F87>9 8G7?9 "-%#;7%5?58%M%+%N%8.8BB%(&))*+,(#-,&+%H<&'"AA,&+#;A7%O%86P%JC"<"%$&%1&*%L&<KQ%O%8>P%JC#-%,A%1&*<%H&A,-,&+Q% 7-16&$#6%$"& 2&))*+,(#-,&+%$"H#<-)"+-%%%%%F?7F9 X&,+-%A-&(K%(&)H#+1 8G7>9 T<,S#-"%(&)H#+1 8V7B9 Y&+WH<&',-A B7?9 Z&S"<+)"+-W &L+"$.%H*@;,(W A"(-&<.%H&;,-,(#; &<0#+,A#-,&+ 8D7D9 2&))*+,(#-,&+ (&+A*;-#+(1. TU%#0"+(1. '<"";#+("%(&+A*;-#+- 6V7>9

- 14. 14 Personal background of respondents Gender / Age www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,155 communication professionals. Q 14: What is your position? Q 21: How old are you? Q 22: What is your gender? Q 29: Please state the highest academic/educational qualification you hold. * No degree: 3.5%. Q 30: Are you a member of a professional organisation? Overall Head of communication, Agency CEO Unit leader, Team leader Team member, Consultant Female Male Age (on average) 64.1% 35.9% 39.2 years 57.9% 42.1% 47.3 years 62.2% 37.8% 39.7 years 69.6% 30.4% 33.8 years Highest academic educational qualification* Doctorate (Ph.D., Dr.) 6.9% Master (M.A., M.Sc., Mag., M.B.A.), Diploma 38.2% Bachelor (B.A., B.Sc.) 48.0% Polytechnical / technical diploma 3.5% Membership in a professional association Asia-Pacific Association of Communication Directors (APACD) 4.6% Other international communication association 15.8% National PR or communication association 34.1%

- 17. 17 Strategic issues and communication channels Coping with the digital evolution and the social web continues to be the major strategic issue and challenge facing communication practitioners in Asia-Pacific, although the percentage of professionals rating this highest (38.1%) has declined since 2015 when 53.1% rated this the most important strategic issue. This signals that practitioners are coming to grips with digital technology and social media. However, using ‘big data’ and algorithms has increased as a strategic concern and focus. Also, building and maintaining trust has become the third highest rated strategic issue, after being ranked seventh in 2017. This is undoubtedly a response to global concerns about disinformation (Bennett & Livingston, 2018) and the reported emergence of post-truth society (Kavanagh & Rich, 2018; McIntyre, 2019). Surprisingly, building and maintaining trust is rated highest by companies (37.3% of practitioners) along with non-profit organisations (41.4% of practitioners), with less concern among government communication professionals (33.3%). This, and high levels of focus among government communicators on coping with the digital evolution and social web; using big data and algorithms; and dealing with the speed and volume of information flow; suggest government priority on dissemination of information rather than engagement and two-way communication. Dealing with sustainable development and social responsibility has increased most as a strategic concern, with almost 30% of all practitioners rating this a high priority in 2020 compared with just 19.3% in 2015. This finding is appropriate and encouraging, given the warning by social scientists such as Couldry and Mejias (2019) that new information and communication technologies (ICTs) are being widely used to deceive and manipulate people. A recent extensive global study found that many public relations and corporate and marketing communication professionals are participants in disinformation, deception, and manipulation of citizens through practices such as paid influencers and sponsored content (Macnamara, 2020). An analysis of attitudes towards artificial intelligence (AI) by Bourne (2019) described public relations practitioners as “cheerleaders” without adequate concern for ethics and consumer protection. Thus, increased focus on social responsibility is timely. Linking communication to business strategy, the second highest rated strategic issue in 2017, has declined in focus, to be rated seventh in 2020. However, this may be the result of the increase in other strategic concerns, rather than declining importance. The shift to social media and mobile communication has not been as significant as predicted in 2017. Rather, the use of social media has grown steadily, and use of mobile communication such as mobile web and phone and tablet apps has remained stable. Contrary to predictions of the ‘end of newspapers’ (Meyer, 1994), press and media relations remains a major activity, with only a small decline since 2017—albeit the focus is now online newspapers. More than 80% of practitioners continue to rate press and media relations as important. Looking ahead to 2023, practitioners in Asia-Pacific see continuing growth in the importance and use of social media and mobile communication, and stable patterns in use of websites, with continuing gradual decline in online as well as print newspapers, radio, TV, and events.

- 18. 18 Most important strategic issues for communication management until 2023 www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,155 communication professionals. Q 8: Which issues will be most important for communication management/PR within the next three years from your point of view? Please pick exactly 3 items. Percentages: Frequency based on selection as Top-3 issue. 38.1% 36.9% 34.3% 31.8% 29.9% 28.2% 25.5% 24.1% 22.7% 20.3% 8.3% Coping with the digital evolution and the social web Using big data and/or algorithms for communication Building and maintaining trust Strengthening the role of the communication function in supporting top-management decision making Dealing with sustainable development and social responsibility Exploring new ways of creating and distributing content Linking business strategy and communication Dealing with the speed and volume of information flow Matching the need to address more audiences and channels with limited resources Elevating and adapting competences of communication practitioners Tackling gender issues on the individual, organisational or professional level

- 19. 19 Long-term development of strategic issues for communication management www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,155 communication professionals (Q 8); Macnamara et al. 2017 / n = 1,306 (Q 1) / Macnamara et al. 2015 / n = 1,200 (Q 3). Q: Which issues will be most important for communication management/PR within the next three years from your point of view? Please pick exactly 3 items. Percentages: Frequency based on selection as Top-3 issue. 53.1% 0.0% 31.2% 30.1% 19.3% 41.0% 48.9% 32.4% 26.8% 28.6% 21.3% 34.9% 38.1% 36.9% 34.3% 31.8% 29.9% 25.5% Coping with the digital evolution and the social web Using big data and/or algorithms for communication Building and maintaining trust Strengthening the role of the communication function in supporting top- management decision making Dealing with sustainable development and social responsibility Linking business strategy and communication 2015 2017 2020

- 20. 20 Relevance of strategic issues differs between types of organisations www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,155 communication professionals. Q 8: Which issues will be most important for communication management/PR within the next three years from your point of view? Please pick exactly 3 items. Percentages: Frequency based on selection as Top-3 issue. 37.5% 35.9% 37.3% 29.7% 32.3% 27.7% 30.2% 20.4% 23.3% 17.2% 8.5% 39.5% 36.1% 33.2% 31.2% 32.2% 27.3% 15.6% 30.7% 23.4% 21.0% 9.8% 34.5% 29.3% 41.4% 34.5% 25.9% 25.9% 22.4% 31.0% 27.6% 15.5% 12.1% 38.5% 39.1% 31.0% 33.6% 27.0% 29.5% 25.9% 23.7% 21.1% 23.5% 7.0% Coping with the digital evolution and the social web Using big data and/or algorithms for communication Building and maintaining trust Strengthening the role of the communication function in supporting top-management decision making Dealing with sustainable development and social responsibility Exploring new ways of creating and distributing content Linking business strategy and communication Dealing with the speed and volume of information flow Matching the need to address more audiences and channels with limited resources Elevating and adapting competences of communication practitioners Tackling gender issues on the individual, organisational or professional level Companies Governmental organisations Non-profit organisations Consultancies & Agencies

- 21. 21 Importance of communication channels and methods today and in the future: Mobile communication is advancing fast; media relations is on the downturn www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,149 communication professionals. Q 12: How important are the following methods in addressing stakeholders, gatekeepers and audiences today? In your opinion, how important will they be in three years? Scale 1 (Not important) – 5 (Very important). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. Perceived importance for addressing stakeholders, gatekeepers and audiences in 2020 and in 2023 +1.7% +4.4% -8.7% -1.1% -7.8% -15.0% -6.2% -3.4% -23.1% -6.6% ∆ 91.6% 82.3% 81.5% 79.2% 76.3% 69.6% 65.4% 57.3% 56.7% 45.6% 93.3% 86.7% 72.8% 78.1% 68.5% 54.6% 59.2% 53.9% 33.6% 39.0% Social media and social networks (e.g., Blogs, Twitter, Facebook) Mobile communication (phone/tablet apps, mobile websites) Press and media relations with online newspapers/magazines Online communication via websites, e-mail, intranets Face-to-face communication Press and media relations with TV and radio stations Events Non-verbal communication (appearance, architecture) Press and media relations with print newspapers/magazines Corporate publishing/owned media (customer/employee magazines) Importance today (scale 4-5) Importance in 2023 (scale 4-5)

- 22. 22 Longitudinal analysis: Social media has clearly gained in importance, while media relations with print newspapers and magazines are rapidly declining www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,149 communication professionals (Q 12); Macnamara et al. 2017 / n ≥ 1,280 (Q2); Macnamara et al. 2015 / n ≥ 1,148 (Q 4). Q: You are almost done – one last question before we move on to the background and socio-demographics! How important are the following methods in addressing stakeholders, gatekeepers and audiences today? In your opinion, how important will they be in three years? Scale 1 (Not important) – 5 (Very important). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. Perceived importance of communication channels for addressing stakeholders, gatekeepers and audiences 91.6% 82.3% 81.5% 79.2% 76.3% 69.6% 65.4% 57.3% 56.7% 45.6% 90.4% 83.8% 83.3% 82.7% 74.9% 67.0% 63.3% 50.3% 61.5% 52.6% 75.0% 66.5% 73.2% 73.6% 71.2% 66.8% 59.8% 42.3% 76.5% 39.1% Social media and social networks (e.g., Blogs, Twitter, Facebook) Mobile communication (phone/tablet apps, mobile websites) Press and media relations with online newspapers/magazines Online communication via websites, e-mail, intranets Face-to-face communication Press and media relations with TV and radio stations Events Non-verbal communication (appearance, architecture) Press and media relations with print newspapers/magazines Corporate publishing/owned media (customer/employee magazines) 2020 2017 2015

- 23. 23 Shift towards social media and mobile communication has not been as strong as estimated in previous studies – and press relations is still better off www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,149 communication professionals (Q 12); Macnamara et al. 2017 / n ≥ 1,274 (Q2). Q: You are almost done – one last question before we move on to the background and socio-demographics! How important are the following methods in addressing stakeholders, gatekeepers and audiences today? In your opinion, how important will they be in three years? Scale 1 (Not important) – 5 (Very important). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. Perceived and predicted importance of communication channels and instruments in 2020 -2.4% -9.0% +2.8% -4.2% +6.8% +15.0% +3.8% +4.4% +17.6% -6.4% ∆ 91.6% 82.3% 81.5% 79.2% 76.3% 69.6% 65.4% 57.3% 56.7% 45.6% 94.0% 91.3% 78.7% 83.4% 69.5% 54.6% 61.6% 52.9% 39.1% 52.0% Social media and social networks (e.g., Blogs, Twitter, Facebook) Mobile communication (phone/tablet apps, mobile websites) Press and media relations with online newspapers/magazines Online communication via websites, e-mail, intranets Face-to-face communication Press and media relations with TV and radio stations Events Non-verbal communication (appearance, architecture) Press and media relations with print newspapers/magazines Corporate publishing/owned media (customer/employee magazines) Importance 2020 (scale 4-5) Predicted importance 2020 (in 2017; scale 4-5)

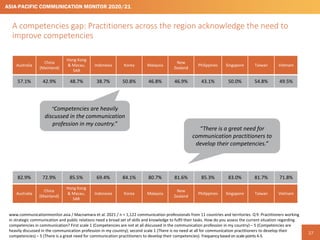

- 25. 25 Competency development: Status quo and future needs Communication competence has been widely discussed in European communication literature (e.g., Tench et al., 2013, 2015) and in the Global Capability Framework produced by the Global Alliance for Public Relations and Communication Management (Gregory & Fawkes, 2019). Tench and Moreno (2015) contend that knowledge, skills and personal attributes (KSAs) constitute the broad competencies in communication departments. Gregory (2008) defined competencies as “behavioral sets or sets of behaviors that support the attainment of organisational objectives. How knowledge and skills are used in performance” (p. 216). Integrating different definitions, Tench and Moreno (2015) described competencies as “the mix of skills and knowledge held by a practitioner, which combine with personal attributes to produce effective professional behaviors” (p. 44). Examination of communication competence in Asia-Pacific shows significant gaps, with four out of five practitioners acknowledging a need to increase competencies. Recognition of this need is highest in Hong Kong and Macau (SAR) (85.5%); the Philippines (85.3%); Korea (84.1%); Singapore (83.0%); Australia (82.9%); Taiwan (81.7%); New Zealand (81.6%); and Malaysia (80.7%). Similar to 2020 European Communication Monitor findings, seasoned and experienced communication professionals in the Asia Pacific region are more aware of the need to develop competence, while almost 25% of young practitioners did not acknowledge a strong need to do so. While acknowledging a need for competencies, there are large gaps between perceived importance of particular competencies and current competency levels. The largest discrepancy can be found in data competence, where 77.6% of practitioners consider data competence to be important, but only 45.1% of practitioners report having high competence. Similarly, even though 75.0% of practitioners consider technology competence to be important, only 46.6% stated they have high levels of competence in relation to technology. Communication leaders are more confident than their subordinates in communication, management, and business, which is consistent with their counterparts in Europe. However, in terms of technology and data competence, there is no difference across seniority levels. Male practitioners reported significantly higher competence in business, technology, and data than female practitioners. In terms of age, senior practitioners reported being more confident in business, management, communication, and data, as could be expected. Closing the competence gap requires investment of more time in education and training (Moreno, et al., 2017). When it comes to how practitioners should improve their competencies, nine in ten Asia-Pacific practitioners consider this a personal responsibility (87.7%) and a responsibility of their employer organisations (87.1%)—although three-quarters also believe professional associations should play a role. Across the region, communication professionals have completed an average of 22 training days per year in 2020, with almost half of those taking place in the practitioner’s free time (weekends, holidays or evenings). Personal development time is highest for those working in non-profit organisations, and lowest among those working in joint stock companies. Differences exist between practitioner age groups, with younger professionals (29 years or younger) investing more than seven weeks of work and leisure time a year in professional development, compared to only 15.8 days a year for those aged 50–59.

- 26. 26 !"#$%&%'()*+%,%-"$#%'&*.'*&/%*("##0'.(1&."'*$2"3%44."'5 6-#"4&*3"02*"0&*"3*3.,%*$21(&.&."'%24*.'*64.1781(.3.(*4%%*1*'%%+*3"2*.#$2",%#%'& !!!"#$%%&'(#)*($'%$'(*$+"),()-.-/)#')%)+) 0*-)1"-2324-.-'-5-46477-#$%%&'(#)*($'-8+$90,,($')1,"-: ;<-=+)#*(*($'0+,-!$+>('?-('-,*+)*0?(#-#$%%&'(#)*($' )'@-8&A1(#-+01)*($',-'00@-)-A+$)@-,0*-$9-,>(11,-)'@->'$!10@?0-*$-9&19(1-*B0(+-*),>,"-C$!-@$-D$&-),,0,,-*B0-#&++0'*-,(*&)*($'-+0?)+@('?-#$%80*0'#(0,-('-#$%%&'(E #)*($',F-G(+,*-,#)10-4-HI$%80*0'#(0,-)+0-'$*-)*-)11-@(,#&,,0@-('-*B0-#$%%&'(#)*($'-8+$90,,($'-('-%D-#$&'*+DJ-K 7-HI$%80*0'#(0,-)+0-B0)L(1D-@(,#&,,0@-('-*B0- #$%%&'(#)*($'-8+$90,,($'-('-%D-#$&'*+DJM-,0#$'@-,#)10-4-HNB0+0-(,-'$-'00@-)*-)11-9$+-#$%%&'(#)*($'-8+)#*(*($'0+,-*$-@0L01$8-*B0(+-#$%80*0'#(0,J-K 7-HNB0+0- (,-)-?+0)*-'00@-9$+-#$%%&'(#)*($'-8+)#*(*($'0+,-*$-@0L01$8-*B0(+-#$%80*0'#(0,J" !"#$%$&'(&)&*%$)+&,$$-&./%& 0/112,'0)+'/,&3%)0+'+'/,$%(&+/& -$4$5/3&+#$'%&0/13$+$,0'$(67 O?+00%0'*- 22"PQ R*+$'?-)?+00%0'*- 7P"PQ !"#$%&&'%($##)#*+' ,-./0 O?+00%0'*- S3"PQ R*+$'?-)?+00%0'*- 4T"2Q !"#$%&&'%($##)#*+' 1,.20 !8/13$+$,0'$(&)%$&#$)4'59& -'(02(($-&',&+#$&0/112,'0)+'/,& 3%/.$(('/,&',&19&0/2,+%967

- 27. 27 A competencies gap: Practitioners across the region acknowledge the need to improve competencies www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,122 communication professionals from 11 countries and territories. Q 9: Practitioners working in strategic communication and public relations need a broad set of skills and knowledge to fulfil their tasks. How do you assess the current situation regarding competencies in communication? First scale 1 (Competencies are not at all discussed in the communication profession in my country) – 5 (Competencies are heavily discussed in the communication profession in my country); second scale 1 (There is no need at all for communication practitioners to develop their competencies) – 5 (There is a great need for communication practitioners to develop their competencies). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. “There is a great need for communication practitioners to develop their competencies.” “Competencies are heavily discussed in the communication profession in my country.” Australia China (Mainland) Hong Kong & Macau, SAR Indonesia Korea Malaysia New Zealand Philippines Singapore Taiwan Vietnam 57.1% 42.9% 48.7% 38.7% 50.8% 46.8% 46.9% 43.1% 50.0% 54.8% 49.5% 82.9% 72.9% 85.5% 69.4% 84.1% 80.7% 81.6% 85.3% 83.0% 81.7% 71.8% Australia China (Mainland) Hong Kong & Macau, SAR Indonesia Korea Malaysia New Zealand Philippines Singapore Taiwan Vietnam

- 28. 28 Seasoned communication professionals are more aware of the need to advance knowledge and skills www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,155 communication professionals. Q 9: Practitioners working in strategic communication and public relations need a broad set of skills and knowledge to fulfil their tasks. How do you assess the current situation regarding competencies in communi- cations? First scale 1 (Competencies are not at all discussed in the communication profession in my country) – 5 (Competencies are heavily discussed in the communication profession in my country); second scale 1 (There is no need at all for communication practitioners to develop their competencies) – 5 (There is a great need for communication practitioners to develop their competencies). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. 77.0% 77.4% 79.8% 83.5% 85.7% 29 or younger 30 - 39 40 - 49 50 - 59 60 or older Much or great need to develop competencies

- 29. 29 Communication leaders stress the need for constant professional development more than practitioners at lower levels www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,069 communication professionals. Q 9: Practitioners working in strategic communication and public relations need a broad set of skills and knowledge to fulfil their tasks. How do you assess the current situation regarding competencies in communi- cations? First scale 1 (Competencies are not at all discussed in the communication profession in my country) – 5 (Competencies are heavily discussed in the communication profession in my country); second scale 1 (There is no need at all for communication practitioners to develop their competencies) – 5 (There is a great need for communication practitioners to develop their competencies). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. 82.0% 79.4% 78.7% Head of communication / Agency CEO Unit leader / Team leader Team member / Consultant Much or great need to develop competencies

- 30. 30 91.4% 86.7% 79.0% 75.0% 77.6% 79.3% 66.3% 56.0% 46.6% 45.1% Communication competence Management competence Business competence Technology competence Data competence Important keycompetence (scale 4-5) High personal competence (scale 4-5) Increasing gap Large gaps between perceived importance and personal competence www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,145 communication professionals. Q 10: Competencies are based upon knowledge, skills and personal attributes. Some of them might be more important than others. How important are the following competencies for communication practitioners in your opinion? And how do you rate your personal level in each case? Scale 1 (Very low) – 5 (Very high). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. Importance of competencies vs. personal assessment of competencies by practitioners Communication competence (message creation and production, listening; principles of communication and persuasion) Business competence (dealing with budgets, contracts and taxation; knowledge of markets, products and competitors) Management competence (decision making, planning, organising, measurement, leading people, human resources, self management) Technology competence (software and hardware usage, digital savviness) Data competence (use cases, methods, results interpretation)

- 31. 31 A closer look at competency gaps: Largest share of under-skilled communicators in the fields of technology and data 12.5% 16.3% 19.0% 19.5% 24.0% 36.7% 33.6% 32.3% 32.7% 32.4% Communication competence Management competence Business competence Technology competence Data competence www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,145 communication professionals. Q 10: Competencies are based upon knowledge, skills and personal attributes. Some of them might be more important than others. How important are the following competencies for communication practitioners in your opinion? And how do you rate your personal level in each case? Scale 1 (Very low) – 5 (Very high). Under-skilled professionals Critically under-skilled professionals ∑ 49.2% ∑ 51.3% ∑ 49.9% ∑ 52.2% ∑ 56.4% Total of under-skilled communicators How the number of under-skilled professionals has been calculated Under-skilled professionals = those who perceive the importance of a competence 1 scale point higher than their personal level (e. g. importance = 5 “very high”, but personal level = 4 “above average”). Critically under-skilled professionals = those who perceive the importance of a competence 2 or more scale points higher than their personal level (e. g. importance = 4 „above average“, but personal level = 2 “below average”).

- 32. 32 Practitioners working in governmental and non-profits organisations rate their business competencies lower than other sectors www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,145 communication professionals. Q 10: Competencies are based upon knowledge, skills and personal attributes. Some of them might be more important than others. How important are the following competencies for communication practitioners in your opinion? And how do you rate your personal level in each case? Scale 1 (Very low) – 5 (Very high). Mean values. ** Highly significant differences (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.01). Personal assessment of competency levels by communication professionals 4.05 3.82 3.63 3.53 3.40 4.09 3.72 3.20 3.45 3.38 3.97 3.88 3.28 3.53 3.38 4.12 3.91 3.73 3.35 3.35 2.50 4.00 Companies Governmental organisations Non-profit organisations Consultancies & Agencies Communication competence Management competence Business competence ** Technology competence Data competence (1) Very low Very high (5) (3)

- 33. 33 Communication competence strong, but practitioners need to increase competencies in data, technology and business Personal assessment of competency levels by communication professionals www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 247 communication professionals. Q 10: Competencies are based upon knowledge, skills and personal attributes. Some of them might be more important than others. How important are the following competencies for communication practitioners in your opinion? And how do you rate your personal level in each case? Scale 1 (Very low) – 5 (Very high). Mean values. ** Highly significant differences (independent samples T-Test, p ≤ 0.01). * Significant differences (independent samples T-Test, p ≤ 0.05). 4.30 4.17 3.87 3.49 3.48 4.11 3.72 3.45 3.40 3.25 3.98 3.72 3.41 3.55 3.36 4.20 4.10 3.80 3.45 3.47 4.08 3.78 3.61 3.50 3.46 2.50 3.50 4.50 Strategy and coordination Media relations Online communication Consultancy, advising, coaching, key account Marketing, brand, consumer communication Communication competence ** Management competence ** Business competence ** Technology competence * Data competence ** (1) Very low Very high (5) (3)

- 34. 34 Leaders are confident about their business, management and communication competencies, but rank equally to their subordinates in handling tech and data www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,063 communication professionals. Q 10: Competencies are based upon knowledge, skills and personal attributes. Some of them might be more important than others. How important are the following competencies for communication practitioners in your opinion? And how do you rate your personal level in each case? Scale 1 (Very low) – 5 (Very high). Mean values. ** Highly significant differences (Kendall rank correlation, p ≤ 0.01). Personal assessment of competency levels by communication professionals 3.86 3.54 3.26 3.27 3.42 4.11 3.95 3.62 3.38 3.43 4.40 4.21 4.04 3.51 3.50 2.50 3.50 4.50 Team member / Consultant Unit leader / Team leader Head of communication / Agency CEO Communication competence ** Management competence ** Business competence ** Technology competence Data competence (1) Very low Very high (5) (3)

- 35. 35 Male professionals rate their skills and knowledge higher than female peers – significant differences in the levels of business, technology and data competencies www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,142 communication professionals. Q 10: Competencies are based upon knowledge, skills and personal attributes. Some of them might be more important than others. How important are the following competencies for communication practitioners in your opinion? And how do you rate your personal level in each case? Scale 1 (Very low) – 5 (Very high). Mean values. ** Highly significant differences (independent samples T-Test, p ≤ 0.01). * Significant differences (independent samples T-Test, p ≤ 0.05). Personal assessment of competency levels by communication professionals 4.05 3.82 3.52 3.35 3.32 4.14 3.88 3.68 3.61 3.47 2.50 3.50 4.50 Female professionals Male professionals Communication competence Management competence Business competence ** Technology competence ** Data competence * (1) Very low Very high (5) (3)

- 36. 36 Older professionals lagging behind in technology competencies, but are stronger in terms of communication, management, and business skills www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,145 communication professionals. Q 10: Competencies are based upon knowledge, skills and personal attributes. Some of them might be more important than others. How important are the following competencies for communication practitioners in your opinion? And how do you rate your personal level in each case? Scale 1 (Very low) – 5 (Very high). Mean values. ** Highly significant differences (Pearson correlation, p ≤ 0.01). * Significant differences (Pearson correlation, p ≤ 0.05). Personal assessment of competency levels by communication professionals 3.70 3.47 3.11 3.40 3.28 4.06 3.72 3.53 3.55 3.40 4.19 3.98 3.73 3.41 3.38 4.38 4.23 3.89 3.40 3.40 4.41 4.43 4.09 3.20 3.59 2.50 3.50 4.50 29 or younger 30 - 39 40 - 49 50 - 59 60 or older Communication competence ** Management competence ** Business competence ** Technology competence Data competence * (1) Very low Very high (5) (3)

- 37. 37 Competency development: Most practitioners believe it is the responsibility of themselves and their employers www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,129 communication professionals. Q 11: Who should take care of the further development of competencies in the communication profession from your point of view? Scale 1 (Strongly disagree) – 5 (Strongly agree). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. Responsibility for the further development of competencies in the communication profession 87.7% 87.1% 74.5% Communication practitioners themselves, who should invest in their professional development (micro level) Organisations, who should offer development programmes for their communication staff (meso level) Professional associations, who should offer development programmes (micro level)

- 38. 38 !"#$%&$'()*($)+,'%'-$.(/'0'1),+'-%(&-(23!#$&*&$5 6)++7-&$#%&)-(,")*'33&)-#13(8#0'($)+,1'%'/(#-(#0'"#9'()*(::(%"#&-&-9(/#.3(,'"(.'#" !!!"#$%%&'(#)*($'%$'(*$+"),()-.-/)#')%)+) 0*-)1"-2324-.-'-5-646-#$%%&'(#)*($'-7+$80,,($')1,"-9 2:;-<'-234=>-?$!-%)'@-A)@,-?)B0-@$&-,70'*-$'-70+,$')1 *+)('('C-)'A-A0B01$7%0'*-('-)'@-8(01A,-D('#1&A('C-8&+*?0+-0A&#)*($'-.-,*&A@('C-!?(10-!$+E('CF-)AA-7)+*G*(%0-*$-8&11-A)@,HI-9-2J; K'A-?$!-%)'@-$8-*?0,0-A)@, !0+0-@$&+-8+00-*(%0-*?)*-@$&-?)B0-('B0,*0A-D!00E0'A,>-?$1(A)@,>-0B0'('C,>-LHI-/0)'-B)1&0," M)@,-$8-8+00-*(%0 DN00E0'A,>-?$1(A)@,> 0B0'('C,>-LH M)@,-$8-!$+E-*(%0 !! "# !"##$%&'($()*+,$-+$)*.(-+&#$,.&/+/+0$&+%$%*1*#-)2*+,$/+$3456 "! OB0+)11-*+)('('C-A)@, $ %

- 39. 39 Days spent for personal training and development across Asia-Pacific Days of work time Days of free time (Weekends, holidays, evenings, …) Overall training days Australia 15.7 17.5 33.2 China (Mainland) 9.5 8.8 18.3 Hong Kong & Macau, SAR 2.8 4.7 7.5 Indonesia 18.3 9.1 27.4 Korea 23.4 14.1 37.5 Malaysia 12.5 6.9 19.4 New Zealand 7.9 5.2 13.1 Philippines 17.0 4.5 21.5 Singapore 8.0 10.5 18.5 Taiwan 8.8 15.3 24.1 Vietnam 25.9 11.5 37.4 www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 696 communication professionals from 11 countries and territories. Q 24: In 2019, how many days have you spent on personal training and development in any fields (including further education / studying while working; add part-time to full days)? Q 25: And how many of these days were your free time that you have invested (weekends, holidays, evenings, …)? Mean values.

- 40. 40 Communication professionals in non-profits spend more time on personal development than their colleagues in other types of organisations www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 717 communication professionals. Q 24: In 2019, how many days have you spent on personal training and development in any fields (including further education / studying while working; add part-time to full days)? Q 25: And how many of these days were your free time that you have invested (weekends, holidays, evenings, …)? Mean values. Average number of full days spent by communication practitioners for personal training and development 5.5 18.2 16.9 11.3 11.4 9.3 10.1 10.1 19.9 7.8 Joint stock companies Private companies Governmental organisations Non-profit organisations Consultanices & Agencies Number of work days spent on personal training and development Number of free time days spent on personal training and development ∑ 14.8 ∑ 28.3 ∑ 27.0 ∑ 31.2 ∑ 19.2

- 41. 41 Younger professionals invest five weeks of work and leisure time in further education per year – many of them will probably study part-time to advance skills www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 717 communication professionals. Q 24: In 2019, how many days have you spent on personal training and development in any fields (including further education / studying while working; add part-time to full days)? Q 25: And how many of these days were your free time that you have invested (weekends, holidays, evenings, …)? Mean values. ** Highly significant differences (Pearson correlation, p ≤ 0.01). * Significant differences (Pearson correlation, p ≤ 0.05). Average number of full days spent by communication practitioners for personal training and development 20.8 12.8 9.4 9.5 11.4 14.2 8.9 9.7 6.3 6.4 29 or younger 30 - 39 40 - 49 50 - 59 60 or older Number of work days spent on personal training and development ** Number of free time days spent on personal training and development * ∑ 35.0 ∑ 21.7 ∑ 19.1 ∑ 15.8 ∑ 17.8

- 43. 43 Ethical challenges and resources for the communication profession Globalisation and advances in technology have created opportunities for public relations and strategic communication management. However, they also raise ethical concerns. Coleman and Wilkins (2009) contend that public relations practitioners are “good ethical thinkers” (p. 335) for their organisations. Yet, with the growing public concern about misinformation, disinformation, and manipulative corporate and marketing communication (Macnamara, 2020), practitioners in public relations and communication management are coming under increased pressure to make ethical decisions and provide ethical advice. More than half of the communication practitioners surveyed (56.5%) report experiencing one or more ethical challenges in their work in the past year. Practitioners in Southeast Asian countries including Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam report facing several ethical challenges a year. Interestingly, while 43.6% of all practitioners report facing no ethical challenges in the past year, practitioners in China (Mainland) and Taiwan report the least ethical challenges, with 64.7% of practitioners in China (Mainland) and 61.5% in Taiwan reporting ‘no ethical challenges’. In terms of dealing with ethical challenges, Place (2010) has reported that practitioners rely on moral duty and maintaining others’ dignity in making ethical decisions. These approaches are underpinned by personal values. Industry and organisation policies are also a source of guidance, and almost all professional associations provide a code of ethics to their members. Practitioners in Asia-Pacific report using all resources available at macro (72.8%), meso (83.6%), and micro (86.9%) levels when dealing with ethical challenges. While relying on personal values is the most common approach in most countries and territories, Indonesian practitioners report relying mostly on codes of ethics of professional associations, while practitioners in the Philippines mostly use organisational ethical guidelines (meso level). This indicates that it is important for organisations and professional associations to support practitioners in relation to ethical decisions and practice. Digital technologies have had a significant impact on public relations and communication management (Wiesenberg & Tench, 2020; Wiesenberg, Zerfass, & Moreno, 2017). While offering many benefits, concerns about privacy and ethical use of communication technology have been raised (Yang & Kang, 2015). This study found that more than 75% of Asia-Pacific practitioners are concerned about using bots (76.4%) and about using personal data as part of ‘big data’ analyses (76.8%)—far higher than their European counterparts. Audience targeting and profiling based on demographic information is the least concern in terms of ethics, although more than half of the practitioners surveyed (52%) expressed concern about this practice. Training in ethics is identified as a key method for improving ethical practice. But 30.1% of practitioners report that they have never participated in ethics training. Of those who have had ethics training, 30.5% received this through their employer organisation and 26.1% attended ethics courses offered by professional associations. This indicates that professional associations could do more to address this gap. As Schauster and Neill (2017) noted, public relations and communication management need to respond to the fast-moving business and digital environments. Increased initiatives by professional associations and employer organisations could improve ethical understanding and practice, particularly in relation to use of new digital technologies.

- 45. 45 Ethical challenges in communication differ between countries and territories www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,020 communication professionals from 11 countries and territories. Q 1: Like anyone else, Communication professionals sometimes face situations where particular activities might be legally acceptable, but challenging from a moral point of view. In your day to day work during the past 12 months, have you experienced ethical challenges? No / Yes, once / Yes, several times / Don’t know or don’t remember. 25.7% 64.7% 48.6% 23.6% 48.3% 26.7% 49.0% 22.3% 54.8% 61.5% 20.2% 17.1% 10.4% 18.0% 14.5% 12.1% 11.4% 18.4% 21.3% 15.5% 8.7% 17.0% 57.1% 24.9% 33.3% 61.8% 39.7% 61.9% 32.7% 56.4% 29.8% 29.8% 62.8% 0% 100% Australia China (Mainland) Hong Kong & Macau, SAR Indonesia Korea Malaysia New Zealand Philippines Singapore Taiwan Vietnam No ethical challenges One ethical challenge Several ethical challenges

- 46. 46 Female communication practitioners report significantly less ethical challenges than their male colleagues www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,048 communication professionals. Q 1: Like anyone else, communication professionals sometimes face situations where particular activities might be legally acceptable, but challenging from a moral point of view. In your day to day work during the past 12 months, have you experienced ethical challenges? No / Yes, once / Yes, several times / Don’t know or don’t remember. Significant differences between women and men (Mann-Whitney U Test, p ≤ 0.05). Number of ethical challenges encountered in day to day work in the past year 46.0% 39.7% 14.8% 14.0% 39.3% 46.3% 0% 100% Female professionals Male professionals No ethical challenges One ethical challenge Several ethical challenges

- 47. 47 Ethical challenges are most common in governmental organisations, compared to other types of organisations Number of ethical challenges encountered by communication professionals in day to day work in the past year www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,051 communication professionals. Q 1: Like anyone else, communication professionals sometimes face situations where particular activities might be legally acceptable, but challenging from a moral point of view. In your day to day work during the past 12 months, have you experienced ethical challenges? No / Yes, once / Yes, several times / Don’t know or don’t remember. Highly significant differences between various types of organisations (chi-square test, p ≤ 0.01). 33.0% 38.9% 42.4% 43.7% 56.7% 15.4% 14.8% 13.8% 15.8% 11.2% 51.6% 46.3% 43.8% 40.6% 32.1% 0% 100% Governmental organisations Non-profit organisations Private companies Consultancies & Agencies Joint stock companies No ethical challenges One ethical challenge Several ethical challenges

- 48. 48 Communication generalists report less ethical incidents than their peers in other areas of work www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 231 communication professionals. Q 1: Like anyone else, communication professionals sometimes face situations where particular activities might be legally acceptable, but challenging from a moral point of view. In your day to day work during the past 12 months, have you experienced ethical challenges? No / Yes, once / Yes, several times / Don’t know or don’t remember. Q 24: What are the dominant areas of your work? Please pick 3! ** Highly significant differences (chi-square test, p ≤ 0.01). Number of ethical challenges encountered by communication professionals in day to day work in the past year 39.7% 40.3% 43.2% 44.1% 44.4% 49.3% 15.6% 16.0% 12.8% 13.7% 16.7% 12.7% 44.7% 43.7% 44.0% 42.1% 38.9% 38.0% 0% 100% Consultancy, advising, coaching, key account Strategy and coordination Media relations Online communication Marketing, brand, consumer communication Overall communication ** No ethical challenges One ethical challenge Several ethical challenges

- 49. 49 Dealing with ethical challenges: Most practitioners rely on their personal values; organisational guidelines and codes promoted by associations are less important Resources used by communication practitioners when dealing with ethical challenges www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 493 communication professionals. Q 2: How important were the following resources to you when dealing with ethical challenges? Scale 1 (Not important) – 5 (Very important). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. 86.9% 83.6% 72.8% My personal values and beliefs (micro level) Ethical guidelines of my organisation (meso level) Ethical codes of practice of professional associations (macro level)

- 50. 50 Resources used for dealing with ethical challenges across Asia-Pacific www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 480 communication professionals from 11 countries and territories. Q 2: How important were the following resources to you when dealing with ethical challenges? Scale 1 (Not important) – 5 (Very important). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. Ethical codes of practice of professional associations (macro level) Ethical guidelines of my organisation (meso level) My personal values and beliefs (micro level) Australien 56.0% 77.8% 84.0% China (Mainland) 65.0% 79.6% 88.3% Hong Kong & Macau, SAR 66.1% 78.3% 83.9% Indonesia 97.6% 92.3% 88.1% Korea 50.0% 73.1% 73.3% Malaysia 84.4% 86.4% 90.9% New Zealand 72.0% 88.2% 92.0% Philippines 90.4% 92.2% 91.8% Singapore 56.8% 84.4% 91.9% Taiwan 70.0% 80.6% 87.5% Vietnam 76.0% 85.7% 88.0%

- 51. 51 Organisational guidelines are most acknowledged in governmental organisations, while practitioners in consultancies and agencies trust in personal values and beliefs www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 493 communication professionals. Q 2: How important were the following resources to you when dealing with ethical challenges? Scale 1 (Not important) – 5 (Very important). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. Resources used by communication practitioners when dealing with ethical challenges 73.5% 83.2% 82.7% 79.0% 89.8% 89.5% 75.8% 83.3% 81.8% 68.5% 80.4% 89.8% Ethical codes of practice of professional associations (macro level) Ethical guidelines of my organisation (meso level) My personal values and beliefs (micro level) Companies Governmental organisations Non-profit organisations Consultancies & Agencies

- 52. 52 Female communicators rely more often on professional codes of ethics and organisational guidelines, while men depend on their personal values and beliefs www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 492 communication professionals. Q 2: How important were the following resources to you when dealing with ethical challenges? Scale 1 (Not important) – 5 (Very important). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. Resources used for dealing with ethical challenges 75.6% 85.7% 85.8% 68.9% 80.2% 88.4% Ethical codes of practice of professional associations (macro level) Ethical guidelines of my organisation (meso level) My personal values and beliefs (micro level) Female professionals Male professionals

- 53. 53 Ethical concerns over communication practices on social media: Three out of four practitioners are worried about using bots and big data analyses Ethical challenges of current communication practices www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 1,036 communication professionals. Q 3: Strategic communication and public relations are constantly evolving and introducing new ways of communicating with stakeholders. How challenging are the following practices in your opinion in terms of ethics? Scale 1 (Ethically not challenging at all) – 5 (Ethically extremely challenging). 55.6% 55.3% 45.9% 45.2% 44.0% 37.4% 30.5% 20.8% 21.5% 21.8% 24.2% 24.2% 23.8% 21.5% 23.6% 23.2% 32.3% 30.6% 31.8% 38.8% 48.0% 0% 100% Using bots to generate feedback and followers on social media Exploiting audiences' personal data by applying big data analyses Motivating employees to spread organisational messages on their private social media accounts Using sponsored social media posts and sponsored articles on news websites that look like regular content Paying social media influencers to communicate favourably Editing entries about my organisation on public wikis Profiling and targeting audiences based on their age, gender, ethnicity, job, or interests Extremely/verychallenging (scale 4-5) Moderately challenging (scale 3) Slightly/not challenging (scale 1-2)

- 54. 54 Ethical concerns over communication practices across Asia-Pacific www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 480 communication professionals from 11 countries and territories. Q 3: Strategic communi- cation and public relations are constantly evolving and introducing new ways of communicating with stakeholders. How challenging are the following practices in your opinion in terms of ethics? Scale 1 (Ethically not challenging at all) – 5 (Ethically extremely challenging). Frequency based on scale points 4-5. ** Highly significant differences (chi-square test, p ≤ 0.01). Using bots to generate feedback and followers on social media Exploiting audiences' personal data by applying big data analyses Motivating employees to spread organisational messages on their private social media accounts ** Using sponsored social media posts and sponsored articles on news websites Paying social media influencers to communicate favourably ** Editing entries about my organisation on public wikis ** Profiling and targeting audiences based on age, gender, ethnicity, job, or interests Australia 84.4% 72.7% 34.3% 67.6% 47.1% 44.1% 20.6% China (Mainland) 43.9% 45.0% 38.8% 40.0% 42.7% 30.9% 38.9% Hong Kong & Macau, SAR 48.0% 48.1% 40.4% 36.2% 25.9% 25.5% 15.4% Indonesia 61.7% 72.9% 62.3% 50.0% 51.7% 49.2% 48.4% Korea 53.3% 47.5% 50.4% 42.4% 41.1% 33.3% 23.4% Malaysia 61.8% 66.7% 52.8% 48.5% 53.3% 44.6% 45.0% New Zealand 77.8% 64.4% 43.5% 46.8% 42.6% 36.6% 8.2% Philippines 63.5% 60.2% 41.4% 43.4% 54.2% 38.6% 29.4% Singapore 72.2% 47.7% 32.6% 42.9% 36.3% 34.1% 20.9% Taiwan 40.5% 52.3% 56.0% 53.2% 45.2% 40.6% 28.8% Vietnam 46.9% 66.7% 48.0% 43.9% 45.5% 50.0% 37.0%

- 55. 55 Communicators working in governmental organisations and non-profits are more troubled about using bots and exploiting audiences’ personal data Ethical challenges of current communication practices www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 1,036 communication professionals. Q 3: Strategic communication and public relations are constantly evolving and introducing new ways of communicating with stakeholders. How challenging are the following practices in your opinion in terms of ethics? Scale 1 (Ethically not challenging at all) – 5 (Ethically extremely challenging). Mean values. ** Highly significant differences (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.01). * Significant differences (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05). 3.61 3.53 3.03 3.17 3.16 2.82 2.66 3.41 3.40 3.16 3.11 3.11 2.89 2.79 3.90 3.88 3.48 3.45 3.53 3.10 3.05 3.72 3.73 3.42 3.51 3.51 3.18 3.11 3.38 3.39 3.13 3.21 3.10 2.93 2.51 Joint stock companies Private companies Governmental organisations Non-profit organisations Consultancies & Agencies Profiling and targeting audiences based on their age, gender, ethnicity, job, or interests ** Motivating employees to spread organisational messages on their private social media accounts * Using sponsored social media posts and sponsored articles on news websites that look like regular content Paying social media influencers to communicate favourably ** Exploiting audiences' personal data by applying big data analyses ** Using bots to generate feedback and followers on social media ** Editing entries about my organisation on public wikis (1) Ethically not challenging at all Ethically extremely challenging (5) (3)

- 56. 56 Male practitioners have most ethical concerns about bots, use of personal data, and employees spreading organisational information on social media Ethical challenges of current communication practices www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 1,034 communication professionals. Q 3: Strategic communication and public relations are constantly evolving and introducing new ways of communicating with stakeholders. How challenging are the following practices in your opinion in terms of ethics? Scale 1 (Ethically not challenging at all) – 5 (Ethically extremely challenging). Mean values. ** Highly significant differences (independent sample T-Test, p ≤ 0.01). * Significant differences (independent sample T-Test, p ≤ 0.05). 3.52 3.56 3.18 3.14 3.19 2.90 2.61 3.56 3.45 3.34 3.32 3.21 3.03 2.92 Female professionals Male professionals Profiling and targeting audiences based on their age, gender, ethnicity, job, or interests ** Motivating employees to spread organisational messages on their private social media accounts ** Using sponsored social media posts and sponsored articles on news websites that look like regular content * Paying social media influencers to communicate favourably * Exploiting audiences' personal data by applying big data analyses Using bots to generate feedback and followers on social media Editing entries about my organisation on public wikis (1) Ethically not challenging at all Ethically extremely challenging (5) (3)

- 57. 57 Younger communication professionals have less ethical concern in relation to sponsored content and social media influencers Ethical challenges of current communication practices www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 1,036 communication professionals. Q 3: Strategic communication and public relations are constantly evolving and introducing new ways of communicating with stakeholders. How challenging are the following practices in your opinion in terms of ethics? Scale 1 (Ethically not challenging at all) – 5 (Ethically extremely challenging). Mean values. ** Highly significant differences (Pearson correlation, p ≤ 0.01). * Significant differences (Pearson correlation, p ≤ 0.05). 3.47 3.33 3.06 2.95 3.23 2.91 2.75 3.45 3.42 2.99 3.09 3.17 2.84 2.65 3.50 3.60 3.38 3.24 3.15 2.97 2.66 3.87 3.85 3.71 3.59 3.21 3.09 2.85 3.69 3.67 3.50 3.76 3.47 3.21 2.98 29 or younger 30 - 39 40 - 49 50 - 59 60 or older Profiling and targeting audiences based on their age, gender, ethnicity, job, or interests Motivating employees to spread organisational messages on their private social media accounts Using sponsored social media posts and sponsored articles on news websites that look like regular content ** Paying social media influencers to communicate favourably ** Exploiting audiences' personal data by applying big data analyses ** Using bots to generate feedback and followers on social media * Editing entries about my organisation on public wikis * (1) Ethically not challenging at all Ethically extremely challenging (5) (3)

- 58. 58 !"#$%$"&%$"'($&()"*"+,-$&.("/0$%1+(%,2-"/"&%$"'3(4*"56(/0$5)(%,227&$%1/$,&( -5,#"''$,&1+($&(8'$19:1%$#$%(01'(&"*"5(-15/$%$-1/")($&(1&6(#,521+(/51$&$&.(,5(%+1''"' !"#$%&%'"$%()*%)*$#"%)%)+*()*&(,,-)%&"$%()*.$/%&0 !!!"#$%%&'(#)*($'%$'(*$+"),()-.-/)#')%)+) 0*-)1"-2324-.-'-5-673-#$%%&'(#)*($'-8+$90,,($')1,"-: 2;<-=)>0-?$&-0>0+-8)+*(#(8)*0@-('-*+)('('A,-$'-#$%%&B '(#)*($' 0*C(#,D-E0,F-G-C)>0-8)+*(#(8)*0@-('-#$%%&'(#)*($'-0*C(#,-*+)('('AH,I-J?-)-8+$90,,($')1-),,$#()*($'-.-E0,F-G-C)>0-8)+*(#(8)*0@ ('-#$%%&'(#)*($'-0*C(#,- *+)('('AH,I-J?-%?-$+A)'(,)*($'-.-E0,F-G-*$$K-)-#$%%&'(#)*($'-0*C(#,-#1),,H0,I-@&+('A-%?-,*&@(0,-.-L$F-'0>0+-.-M$'N*-K'$!-$+-@$'N*-+0%0%J0+"-: 2O<-PC0' !),-*C0-1),*-*(%0-?$&-8)+*(#(8)*0@-('-#$%%&'(#)*($'-0*C(#,-*+)('('AD-Q0,,-*C)'-4-?0)+-)A$-.-4-*$-R-?0)+,-)A$-.-/$+0-*C)'-R-?0)+, )A$-.-G-C)>0'N*-8)+*(#(8)*0@ ('-)'?-#$%%&'(#)*($'-0*C(#,-*+)('('A-,$-9)+-.-M$'N*-K'$!-$+-@$'N*-+0%0%J0+" !"#$% )**0'@0@ 0*C(#,-*+)('('AH,I J?-)-8+$90,,($')1-),,$#()*($' &'#(% )**0'@0@ 0*C(#,-*+)('('AH,I J?-*C0(+-$+A)'(,)*($' &!#!% *$$K-0*C(#,-#1),,H0,I- @&+('A-*C0(+-,*&@(0, &'#$% '0>0+-8)+*(#(8)*0@ ('-)'?-#$%%&'(#)*($'-0*C(#, *+)('('A,-$+-#1),,0, ")#)% 8)+*(#(8)*0@-('-0(*C0+ #$%%&'(#)*($'-0*C(#, *+)('('AH,I-$+-#1),,H0,I 1(-#&.0*(2*$#"%)%)+*()*&(,,-)%&"$%()*.$/%&0 3,-4$%'4.*0.4.&$%()0*'(00%54.6 7/.)*8"0*$/.*4"0$*$%,.*9(-*'"#$%&%'"$.:*%)*&(,,-)%&"$%()*.$/%&0*$#"%)%)+; Q0,,-*C)'-4-?0)+-)A$ !*#$% 4-*$-R-?0)+,-)A$ !'#$% /$+0-*C)'-R-?0)+,-)A$ !+#!%

- 59. 59 Participation in training on communication ethics across Asia-Pacific www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,000 communication professionals from 11 countries and territories. Q 26: Have you ever participated in trainings on communication ethics? Yes, I have participated in communication ethics training(s) by a professional association / Yes, I have participated in communication ethics training(s) by my organisation / Yes, I took a communication ethics class(es) during my studies / No, never / Don't know or don’t remember. 32.4% 23.5% 23.5% 18.9% 26.7% 22.8% 15.1% 40.6% 29.2% 45.0% 31.7% 43.3% 19.5% 34.5% 26.5% 37.5% 30.2% 41.7% 55.3% 14.8% 36.2% 30.8% 18.7% 45.1% 8.9% 39.2% 44.3% 14.7% 30.4% 23.5% 42.4% 32.6% 35.9% 35.3% 44.4% 32.1% 10.0% 38.1% 20.8% 14.9% 23.1% 25.3% 45.1% 13.0% 64.7% 55.6% 67.9% 90.0% 61.9% 79.2% 85.1% 76.9% 74.7% 54.9% 87.0% Australia China (Mainland) Hong Kong & Macau,SAR Indonesia Korea Malaysia New Zealand Philippines Singapore Taiwan Vietnam By a professional association During my studies By my organisation No Yes Participation in training on communication ethics Ethics trainings attended … (multiple selections possible)

- 60. 60 Attending internal ethics training is most common in governmental organisations – joint stock companies rely on further education offered by professional associations www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,033 communication professionals. Q 26: Have you ever participated in trainings on communication ethics? Yes, I have participated in communication ethics training(s) by a professional association / Yes, I have participated in communication ethics training(s) by my organisation / Yes, I took a communication ethics class(es) during my studies / No, never / Don't know or don't remember. 40.5% 37.5% 26.5% 27.5% 30.4% 59.5% 62.5% 73.5% 72.5% 69.6% Joint stock companies Private companies Governmental organisations Non-profit organisations Consultancies & Agencies 34.1% 21.4% 17.9% 23.8% 17.7% 22.7% 18.3% 25.7% 32.0% 33.3% 10.4% 33.3% 28.7% 19.3% 23.1% Participation in training on communication ethics No Yes By a professional association During my studies By my organisation Ethics trainings attended … (multiple selections possible)

- 61. 61 Communication leaders have participated in ethics training more than junior practitioners – particularly training by professional associations www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 963 communication professionals. Q 26: Have you ever participated in trainings on commu- nication ethics? Yes, I have participated in communication ethics training(s) by a professional association / Yes, I have participated in communication ethics training(s) by my organisation / Yes, I took a communication ethics class(es) during my studies / No, never / Don't know or don't remember. 37.7% 32.5% 28.2% 21.6% 34.2% 30.5% 22.6% 26.2% 35.5% 26.2% 31.0% 31.7% 73.8% 69.0% 68.3% Head of communication / Agency CEO Unit leader / Team leader Team member / Consultant Participation in training on communication ethics Ethics trainings attended … (multiple selections possible) No Yes By a professional association During my studies By my organisation

- 63. 63 Assessing and advancing gender equality The PR and communication industry has responded to the United Nation’s inclusion of gender equality in its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with requirements such as reports (i.e. GWPR 2019) and initiatives such as workshops. However, recent studies have pointed out that gender inequalities persist in the communication field globally (Topić et al., 2020). The APCM 2020 study shows that gender issues remain prevalent in Asia. Women make up more than three-quarters (75.9%) of the regional workforce in PR and communication management. However, only 59% of the senior communication leaders in the region are female, suggesting continuing barriers in ascent to leadership. Comparison across countries and territories shows that employment of women and appointment of women to senior roles varies substantially. Women make up 95% of communication departments and agencies in New Zealand, compared to 57% in Indonesia. Female leadership in communication is strong in New Zealand (76.1%), Singapore (78.3%), and Taiwan (69.4%), while Malaysia, the Philippines, and Korea lag in appointment of women to senior roles. A majority (60.8%) of communication professionals s agree that gender equality has advanced, but have mixed opinions on measures for improvement. Almost one-third (32.0%) disagree that enough has been done to support women in the field in their country. Some 42.5% of the respondents recognise a glass ceiling problem at a macro level (across the profession), but only a quarter (25.2%) see a glass ceiling at micro level (in their own organisation). Concern about a glass ceiling at a macro level are most reported in governmental organizations in Asia-Pacific, with 53.5% of communicators in these organisations acknowledging a glass ceiling, compared to only 39.5% perceiving a glass ceiling in companies. The study also identifies denial of a glass ceiling affecting women among male practitioners. Almost half of female communication professionals (47.6%) agree that a glass ceiling affects the field, compared to only 32.5% of males. At a personal level, almost a third (31.3%) of female practitioners stated that they are personally affected by an invisible barrier preventing them from rising up the ranks. Organisational barriers are reported as the major contributors to the glass ceiling, with lack of flexibility to take care of family commitments being the most cited (60.9%), followed by lack of transparency of promotion policies (50.9%), and lack of specific networks and development programmes for women (49.1%). A lack of specific competencies poses a barrier to women in some countries such as Indonesia, with 42.9% citing this concern, while only 9.5% of practitioners in Australia identified this factor. Perhaps not surprisingly, non-profit organisations are rated most highly in terms of offering flexibility to take care of family obligations and having more transparent promotional policies. In terms of how to further advance opportunities for women, the majority of respondents in almost all countries and territories believe that organizations have the most capability to effect change. However, 51.4% of Indonesian communicators and almost 40% of Vietnamese communicators believe that change is mostly up to female communicators themselves. Online communicators say that professional associations can play a key role.

- 64. 64 !"#$"%&'(()"(&*+&,-%./&0#&12&3"%4"#+&-5&4-66)#'4*+'-#&$"3*%+6"#+(&*#$&*7"#4'"(8& ,-6"#&*%"&'#&+9"&6*:-%'+;8&<)+&-#=;&('>&-)+&-5&+"#&+-3&4-66)#'4*+-%(&*%"&5"6*=" !!!"#$%%&'(#)*($'%$'(*$+"),()-.-/)#')%)+) 0*-)1"-2324-.-'-5-46372-#$%%&'(#)*($'-8+$90,,($')1,"-: 2;<-=$!-(,-*>0-,(*&)*($'-+0?)+@('?-!$%0'-('-10)@('? #$%%&'(#)*($'-8$,(*($',-('-A$&+-$+?)'(,)*($'B-C>0-*$8-10)@0+-$9-%A-#$%%&'(#)*($'-@08)+*%0'*.*>0-DEF-$9-%A-)?0'#A-(,-)-!$%)'-. FG0+)116-*>0+0-)+0 %$+0-!$%0'-*>)'-%0'-('-%A-#$%%&'(#)*($'-@08)+*%0'*.)?0'#A"-H#)10<-I0,-.-J$-.-J.K" L+)#*(*($'0+,-!$+M('?-('-#$%%&'(#)*($'- @08)+*%0'*,-)'@-)?0'#(0, C$8-10)@0+,-$9-#$%%&'(#)*($' @08)+*%0'*,-)'@-)?0'#(0, !"#$% %$+0-!$%0' *>)'-%0' &'#(% %$+0-%0' *>)'-!$%0' "$#)% !$%0' '*#!% %0'

- 65. 65 Female communicators are predominant in all types of organisations – female leadership is strongest in non-profits www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n ≥ 1,062 communication professionals. Q 28: How is the situation regarding women in leading communication positions in your organisation? The top leader of my communication department/the CEO of my agency is a woman / Overall, there are more women than men in my communication department/agency. Scale: Yes / No / N/A. Highly significant differences between various types of organisations (chi-square test, p ≤ 0.01). 51.5% 53.0% 56.1% 66.1% 69.8% 48.5% 47.0% 43.9% 33.9% 30.2% 0% 100% Governmental organisations Joint stock companies Private companies Consultancies & Agencies Non-profit organisations Top leader of my communication department / the CEO of my agency is a woman Top leader of my communication department / the CEO of my agency is a man 67.3% 70.4% 71.1% 78.6% 81.8% 32.7% 29.6% 28.9% 21.4% 18.2% 0% 100% Private companies Non-profit organisations Joint stock companies Governmental organisations Consultancies & Agencies More women than men in mycommunication department/agency More men than women in mycommunication department/agency

- 66. 66 More than 95 per cent of all departments and agencies in New Zealand are dominated by female professionals, compared to only 57 per cent in Indonesia www.communicationmonitor.asia / Macnamara et al. 2021 / n = 1,033 communication professionals from 11 countries and territories. Q 28: How is the situation regarding women in leading communication positions in your organisation? The top leader of my communication department/the CEO of my agency is a woman / Overall, there are more women than men in my communication department/agency. Scale: Yes / No / N/A. Highly significant differences between countries (chi-square test, p ≤ 0.01). 80.6% 73.2% 92.0% 57.1% 70.3% 73.5% 95.5% 78.5% 84.1% 73.6% 69.9% 19.4% 26.8% 8.0% 42.9% 29.7% 26.5% 4.5% 21.5% 15.9% 26.4% 30.1% 0% 100% Australia China (Mainland) Hong Kong & Macau, SAR Indonesia Korea Malaysia New Zealand Philippines Singapore Taiwan Vietnam More women than men in mycommunication department/agency More men than women in mycommunication department/agency