Eagle_Ford_Task_Force_Report-0313

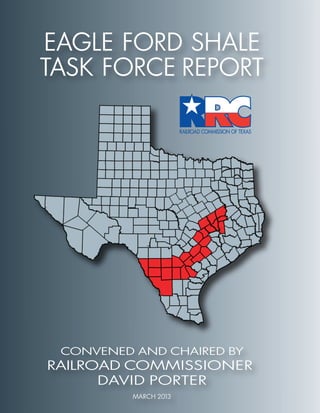

- 1. EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE REPORT CONVENED AND CHAIRED BY RAILROAD COMMISSIONER DAVID PORTER MARCH 2013

- 2. EAGLE FORD SHALE EFS_TOC.indd 1 3/6/2013 5:47:47 PM

- 3. EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter EFS_TOC.indd 2 3/6/2013 5:47:50 PM

- 4. EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Table of Contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 Chapter 1: Workforce Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 Chapter 2: Infrastructure - Roads, Pipelines, Housing . . . . . . . . . . . 21 Chapter 3: Water Quality and Quantity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35 Chapter 4: Railroad Commission Regulations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53 Chapter 5: Economic Benefits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63 Chapter 6: Flaring and Air Emissions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75 Chapter 7: Health Care, Education, and Social Services . . . . . . . . . . . 87 Chapter 8: Landowner, Mineral Owner, and Royalty Owner Issues . .99 Appendix . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A.1 Biographies of Task Force Members . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . b.1 Acknowledgments EFS_TOC.indd 3 3/6/2013 5:47:54 PM

- 5. EFS_TOC.indd 4 3/6/2013 5:47:54 PM

- 6. IntroductionEAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE REPORT “The Eagle Ford Shale has the potential to be the single most significant economic development in our state’s history.” Railroad Commissioner David Porter EFS_Introduction.indd 1 3/6/2013 5:48:17 PM

- 7. 2 INTRODUCTION EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter The shale revolution is sweeping the country and revolutionizing energy and the economy, with Texas and the Eagle Ford Shale leading the way. Texas is the nation’s top oil and natural gas producing state and leads the country in energy technology and policy. The state is home to a number of prolific oil and gas plays, including the Eagle Ford Shale, Permian Basin, Barnett Shale, Haynesville/Bossier Shale, and Granite Wash. The Eagle Ford Shale has the potential to become the most active oil and gas play in North America, with approximately 235 drilling rigs currently running.1 Operators forecast that the play will continue to develop for decades to come. Source: Data from U.S. Energy Information Administration/Graphic by the American Enterprise Institute (October 28, 2012) The Railroad Commission (“Commission”) regulates the exploration and production of oil and gas in Texas. For more than 120 years, the Commission has played a critical role in the establishment of Texas as an interna- tional energy leader. In 2011, the Commission led the way in transparency by formally adopting the Hydraulic Fracturing Chemical Disclosure Rule, one of the nation’s first and most comprehensive rules of its kind, requir- ing operators to report the type and amount of fluids used to hydraulically fracture wells on a national public website.2 The Commission continues to review its policies and rules to ensure that they account for current 1 Baker Hughes Rig Count. 2012 Baker Hughes Rotary Rig Count. Retrieved from http://investor.shareholder.com/bhi/rig_ counts/rc_index.cfm 2 Tex. Nat. Resources Code § 91.851 (Vernon 2011). (The rule implemented forward-looking legislation enacted by the Texas Legislature in 2011.) Daily Oil Production in the Top 4 U.S. Oil-Producing States 2002-2012 EFS_Introduction.indd 2 3/6/2013 5:48:18 PM

- 8. 3 INTRODUCTION EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter technologies and environmental and safety needs in a manner that is efficient and consistent with sound market principles. These are the Commission’s primary responsibilities relative to oil and gas: 1. Prevent waste of oil and gas resources. 2. Protect surface and subsurface water from contamination by oilfield operations. 3. Ensure that all mineral interest owners have an opportunity to recover their fair share of the minerals underlying their property. 4. Ensure that gas utility rates and service are reasonable and non-discriminatory. In performing its responsibilities, the Commission oversees the following: 1. All aspects of oil and natural gas drilling and production, including issuing permits, monitoring, and inspecting oil and gas operations 2. Coal and uranium exploration, surface mining, and reclamation, and issues permits for such operations 3. Natural gas and hazardous liquids intrastate pipelines to ensure the safety of the public and integrity of the environment 4. Gas utility rates and service 5. Propane safety and licenses all propane distributors The Commission no longer has any jurisdiction or authority over railroads, a duty that was transferred to the Texas Department of Transportation in 2005. Moreover, the Commission does not have jurisdiction over roads, traffic, noise, odors, oil and gas leases, pipeline easements, or royalty payments. The Commission is led by three statewide elected officials who serve staggered, six-year terms. The current Commissioners are Chairman Barry T. Smitherman, Commissioner David Porter, and Commissioner Christi Craddick. The Commission employs approximately 700 staff, 41 percent of whom are in the Commission’s dis- trict offices, also referred to as field offices. The field staff performs inspections of oil, natural gas, and pipeline operations. (See Appendix A.1 for Commission Organization Chart.) The productivity of the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas has been unlocked over the past four years with the application of improved horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing techniques, first honed by producers in the Barnett Shale. Upon launching the Eagle Ford Shale Task Force (“Task Force”) in 2011, Commissioner The shale revolution is sweeping the country and revolutionizing energy and the economy, with Texas and the Eagle Ford Shale leading the way. EFS_Introduction.indd 3 3/6/2013 5:48:20 PM

- 9. 4 INTRODUCTION EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter David Porter observed, “The Ea- gle Ford Shale has the potential to be the single most significant eco- nomic development in our state’s history.”3 Experts’ projections confirm Porter’s prediction, with capital expenditure in the Eagle Ford Shale expected to reach near- ly $30 billion in 2013.4 In 2011, the Eagle Ford Shale sup- ported almost 50,000 full-time jobs in 20 counties and contrib- uted over $25 billion dollars to the South Texas economy.5 From 2011 to 2013, daily hydrocarbon liquid production, including nat- ural gas liquids, increased from 100,000 to 700,000 barrels per day.6 These developments have made South Texas one of the most prominent energy producing regions in the United States. The Eagle Ford Shale takes its name from the town of Eagle Ford, Texas, approximately six miles west of Dallas, where the shale outcrops at the surface as clay soil. The wells in the deeper part of the play produce a dry gas, but moving northeastward 3 Porter, D. (2011, July 27). Stated at the Eagle Ford Shale Task Force introduction and agenda-setting meeting, San Antonio, Texas. 4 McMahon, C. (2012, December 6). Wood Mackenzie: Total Eagle Ford capital expenditure to reach US $28 billion in 2013. Wood Mackenzie. Retrieved from http://www.woodmacresearch.com/cgi-bin/wmprod/portal/corp/corpPressDetail. jsp?oid=10950029 5 Center for Community and Business Research, Institute for Economic Development. (2012, May). Economic impact of the Eagle Ford Shale. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 4-5. Retrieved from http://ccbr.iedtexas.org/index. php/Download-document/52-Eagle-Ford-Shale-Final-Report-May-2012.html 6 McMahon, C. (2012). Wood Mackenzie: Total Eagle Ford capital expenditure to reach us$28 billion in 2013. In (Press Release: Energy). Wood Mackenzie. Retrieved from http://www.woodmacresearch.com/cgi-bin/wmprod/portal/corp/corpPressDetail. jsp?oid=10950029 OIL PRODUCTION Eagle Ford Shale - Annual Growth B/D Growth 2008 358 2009 844 136% 2010 11,986 1,320% 2011 126,459 955% 2012 338,911 168% CONDENSATE PRODUCTION Eagle Ford Shale - Annual Growth B/D Growth 2009 1,423 2010 13,708 863% 2011 70,934 417% 2012 72,126 1.6% GAS PRODUCTION Eagle Ford Shale - Annual Growth MMCF/D Growth 2008 8 2009 47 487% 2010 216 360% 2011 959 344% 2012 964 0.5% DRILLING PERMITS Eagle Ford Shale - Annual Growth Permits Growth 2008 26 2009 94 261% 2010 1,010 974% 2011 2,826 180% 2012 4,145 46% PRODUCING OIL WELLS Eagle Ford Shale - Annual Growth Wells Growth 2009 40 2010 72 80% 2011 368 411% 2012 1,262 243% PRODUCING GAS WELLS Eagle Ford Shale - Annual Growth Wells Growth 2008 67 2009 158 136% 2010 550 248% 2011 855 55% EFS_Introduction.indd 4 3/6/2013 5:48:21 PM

- 10. 5 INTRODUCTION EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter out of Commission District 1 and updip, the wells produce more liquids. The core counties include an area that stretches from north of Gonzales County west-southwest to Webb County at the Texas-Mexico border. Eagle Ford Shale wells have been tested in Mexico, but results have not been widely reported. The Eagle Ford Shale contains a high carbonate shale percentage, as high as 70 percent in South Texas. Moving northwest, the formation depth decreases and the shale content increases. The high percentage of carbonate makes the play more brittle and “fracable.” The play trends across at least 23 Texas counties, from the Mexican border to East Texas. It is roughly 50 miles wide and 400 miles long, with an average thickness of 250 feet. Cretaceous in age (66 million to 145 million years old), it lies between the Austin Chalk and the Buda Lime at a depth of approximately 4,000 to 14,000 feet. It is the source rock for the Austin Chalk oil and gas producing formation and the massive East Texas Field. The name has often been misspelled as “Eagleford.” The success of the Eagle Ford Shale is primarily due to its greater productivity of both oil and gas, as com- pared to other traditional shale plays. Oil revenues and petroleum liquid production (i.e., oil, condensate, and natural gas liquids such as ethane, propane, and butane) across the play support economic development, even when natural gas prices are relatively low. Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (May 29, 2010) Average General Properties for the Eagle Ford Shale Play Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Review of Emerging Resources: U.S. Shale Gas and Shale Oil Plays” (July 2011) Depth (ft) 7,000 Thickness (ft) 200 Porosity (%) 9 Total Organic Content (% wt) 4.25 EFS_Introduction.indd 5 3/6/2013 5:48:22 PM

- 11. 6 INTRODUCTION EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Over the past four years, the production of oil, gas, and petroleum liquids in the Eagle Ford Shale has accelerated at a record pace, al- though the growth in natural gas production has been deleteriously affected by lower natural gas prices. Correspondingly, the volume of drilling permits issued by the Commission and the number of oil and gas wells in the region have surged to previously unseen levels. Petrohawk Energy drilled the first of the Eagle Ford wells in 2008, discovering in the process the Hawkville (Eagle Ford) Field in La Salle County (Commission District 1). The discovery well flowed at a rate of 7.6 million cubic feet of gas per day from a 3,200-foot lateral (first perforation was at 11,141 feet total vertical depth) with 10 fracture stages. Originally there were over 30 fields. Due to field consolidations, the current number of fields has been reduced to 21 active fields located within Commission Districts 1 through 6. The two largest fields, the Eagleville (Eagle Ford-1) in District 1 and the Eagleville (Eagle Ford-2) in District 2, contain only oil wells. Many of the larger Eagle Ford Shale fields are governed by a number of special rules. Currently, these are the top 20 operators for oil production in the Eagle Ford Shale from largest to smallest:7 1. EOG Resources 2. Burlington Resources (a unit of ConocoPhillips) 3. Chesapeake Energy 4. GeoSouthern Energy 5. Anadarko 6. Plains Exploration & Production 7. EP Energy 8. Marathon Oil 9. Murphy Oil 10. Pioneer Natural Resources 7 Railroad Commission Production Data-Query (02/25/2013) 11. Carrizo Oil & Gas 12. Goodrich Petroleum 13. Penn Virginia Corporation 14. Hilcorp Energy 15. Petrohawk Energy (a unit of BHP Billiton) 16. Comstock Oil & Gas 17. Rosetta Resources 18. Cabot Oil & Gas 19. Newfield Exploration 20. Matador Resources The Eagle Ford Shale has the potential to become the most active oil and gas play in North America, with approximately 235 drilling rigs currently running. EFS_Introduction.indd 6 3/6/2013 5:48:23 PM

- 12. 7 INTRODUCTION EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter 11. Swift Energy 12. EP Energy 13. Plains Exploration & Production 14. XTO Energy 15. Marathon Oil 16. Talisman Energy 17. Paloma Resources 18. Hilcorp Energy 19. Murphy Oil 20. Carrizo Oil & Gas Currently, these are the top 20 operators for gas production in the Eagle Ford Shale from largest to smallest:8 1. Anadarko 2. Petrohawk Energy (a unit of BHP Billiton) 3. Burlington Resources (a unit of ConocoPhillips) 4. EOG Resources 5. GeoSouthern Energy 6. Chesapeake Energy 7. SM Energy 8. Rosetta Resources 9. Lewis Energy 10. Pioneer Natural Resources EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Railroad Commissioner David Porter took office in 2011 believing that many of the divisive and challenging issues that arose during the development of the Barnett Shale could have been alleviated if the local communi- ties and other involved parties had a forum for open and constructive dialogue. To ensure that development in the Eagle Ford Shale is not hindered by a lack of communication, Commissioner Porter formed the 24-member Task Force, assembling a group of stakeholders from various interests and areas of expertise. He has led the Task Force with a belief in the importance of protecting the health and safety of Texans and properly managing the state’s precious natural resources, while encouraging the oil and gas industry to efficiently and economically produce the energy needed to support the Texas and U.S. economies. The Task Force is comprised of a diverse group of community leaders, local elected officials, water represen- tatives, environmental groups, oil and gas producers, pipeline companies, oil services companies (including a hydraulic fracturing company, a trucking company, and a water resources management company), landowners, mineral owners, and royalty owners. 8 Ibid. Commissioner Porter has led the Task Force with a belief in the importance of protecting the health and safety of Texans and properly managing the state’s precious natural resources, while encouraging the oil and gas industry to efficiently and economically produce the energy needed to support the Texas and U.S. economies. EFS_Introduction.indd 7 3/6/2013 5:48:24 PM

- 13. 8 INTRODUCTION EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter These are the Task Force members, in alphabetical order: • Greg Brazaitis Energy Transfer, Chief Compliance Officer, Houston • The Honorable Jaime Canales Webb County Commissioner, Precinct 4, Laredo • Teresa Carrillo Sierra Club, Executive Committee Member, Lone Star Chapter, Treasurer, Coastal Bend Sierra, Corpus Christi • James E. Craddock Rosetta Resources, Senior Vice President, Drilling and Production Operations, Houston • Steve Ellis EOG Resources, Senior Division Counsel, Corpus Christi • The Honorable Daryl Fowler DeWitt County Judge, Cuero • Brian Frederick DCP Midstream, Senior Vice President, Southern Region, Houston • Anna Galo ANB Cattle Company, Vice President, Laredo • The Honorable Jim Huff Live Oak County Judge, George West • Stephen Ingram Halliburton, Technology Manager, Houston Business Development & Onshore South Texas, Houston • Mike Mahoney Evergreen Underground Water Conservation District, General Manager, Pleasanton • Leodoro Martinez Middle Rio Grande Development Council, Executive Director, Cotulla • James Max Moudy MWH Global, Inc., Senior Client Service Manager, Houston • Terry Retzloff TR Measurement Witnessing, LLC, Founder, Campbellton • Trey Scott Trinity Mineral Management, LTD, Founder, San Antonio • Paula Seydel Dimmit County Chamber of Commerce, Carrizo Springs • The Honorable Barbara Shaw Karnes County Judge, Karnes City • Mary Beth Simmons Shell Exploration and Production Company, Senior Staff Reservoir Engineer, Houston • Kirk Spilman Marathon Oil, Regional Vice President-Eagle Ford • Susan Spratlen Pioneer Natural Resources, Vice President, Sustainability & Communication, Dallas • Glynis Strause Conoco Phillips, Community Relations Advisor for the Eagle Ford Shale, and former Dean of Institutional Advancement, Coastal Bend College, Beeville • Chris Winland Good Company Associates, Associate; The Univer- sity of Texas at San Antonio, Assistant Director, San Antonio Clean Energy Incubator, Austin/San Antonio • Paul Woodard J&M Premier Services, President, Palestine • Erasmo Yarrito, Jr. Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, Rio Grande Watermaster, Harlingen EFS_Introduction.indd 8 3/6/2013 5:48:25 PM

- 14. 9 INTRODUCTION EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter d r- o The Task Force established its three major priorities at its first monthly meeting, held at Luciano’s on the River in San Antonio on July 27, 2011: (1) Open the lines of communications among all parties (2) Provide recommendations and advisements for developing the Eagle Ford Shale in a responsible manner (3) Promote the economic benefits of the Eagle Ford Shale locally and statewide The Task Force met 10 times from July 2011 to November 2012 to study the following issues: • Workforce Development • Infrastructure - Roads, Pipelines, Housing • Water Quality and Quantity • Railroad Commission Regulations • Economic Benefits • Flaring and Air Emissions • Health, Education, and Social Services • Landowner, Mineral Owner, and Royalty Owner Issues Chapters reporting on each of these topics follow. EFS_Introduction.indd 9 3/6/2013 5:48:28 PM

- 15. EFS_Introduction.indd 10 3/6/2013 5:48:28 PM

- 16. 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT In 2011, when the nation’s unemployment rate was above nine percent, South Texas was generating a windfall of high-paying jobs — and the oil and gas industry’s demand for skilled labor in the Eagle Ford Shale will remain strong. EFS_Chapter_1.indd 11 3/6/2013 5:35:51 PM

- 17. 12 CHAPTER 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Eagle Ford Shale production has far surpassed previous growth projections. Consequently, job openings direct- ly and indirectly related to the oil and gas industry have exceeded all forecasts. The challenge facing the prolific Eagle Ford Shale is clear: How do we maintain the manpower needed to supply the growing shale play, and how do we ready the local workforce to take advantage of the near limitless job opportunities presented by the play? In 2011, the Eagle Ford Shale supported 38,000 full-time jobs in its core 14 counties: Atascosa, Bee, DeWitt, Dimmitt, Frio, Gonzales, Karnes, La Salle, Live Oak, Maverick, McMullen, Webb, Wilson, and Zavala.1 That year, the average income of an oil and gas industry job was $117,000, an 18 percent increase from 2010.2 At a time when the nation’s unemployment rate was above nine percent,3 South Texas was generating a windfall of high-paying jobs. However, the oil and gas industry is grap- pling with an acute shortage of well-trained, experienced labor in the region. The existing workforce has a finite capacity to meet industry needs.4 1 Center for Community and Business Research, Institute for Economic Development. (2012, May). Economic impact of the Eagle Ford Shale. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 4. Retrieved from http://ccbr.iedtexas.org/index.php/ Download-document/52-Eagle-Ford-Shale-Final-Report-May-2012.html 2 Wood, R. (2012, April 18). Stated at the Eagle Ford Shale Task Force meeting on economic benefits, Gonzales, Texas. 3 Hall, K. (2011, August 5). Statement of Keith Hall, Commissioner, Bureau of Labor Statistics before the Joint Economic Com- mittee, United States Congress. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news. release/archives/jec_08052011.pdf 4 Spilman, K. (2011, August 24). Stated at the Eagle Ford Shale Task Force meeting on workforce development, Beeville, Texas. 12 CHAPTER 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT Source: Fuel Fix, “Salaries Surging in Oil and Gas Industry” June 2012 “Strategic alliances among industry, community colleges, universities, and non-profits are essential for supplying an adequately trained workforce in the Eagle Ford Shale.” (Glynis Strause, Eagle Ford Shale Task Force member and Community Relations Advisor for the Eagle Ford Shale, Conoco Phillips; Former Dean of Institutional Advancement, Coastal Bend College) OIL AND GAS AVERAGE SALARIES Geologist $161,000 Geophysicist 184,000 Engineering Technician 91,000 Geological Technician 89,000 Petrophysicist 176,000 Landman 131,000 Land Technicians 72,000 EFS_Chapter_1.indd 12 3/6/2013 5:35:53 PM

- 18. 13 CHAPTER 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter The Eagle Ford Shale play encompasses a 20,000 square mile landmass that is primarily comprised of sparsely populated rural communities.5 In 2008, the entire region had less than one million inhabitants,6 and a very small minority among this modest population possesses oil and gas industry experience or relevant formal edu- cation. The Center for Urban and Regional Planning Research (“CURPR”) at The University of Texas at San Antonio (“UTSA”) confirms that, “… jobs created in the Eagle Ford Shale area require higher skills and educa- tion than the average skill-level currently found in the area.”7 5 Ibid. 6 Center for Community and Business Research, Institute for Economic Development. (2011, February). Economic impact of the Eagle Ford Shale. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 10. Retrieved from http://www.anga.us/media/ content/F7D1441A-09A5-D06A-9EC93BBE46772E12/files/utsa%20eagle%20ford.pdf 7 Kamal, A. College of Architecture, Center for Urban and Regional Planning Research. (2012, July). Strategic housing analy- sis - sustainable choices for the growing demand for housing in the Eagle Ford Shale area of South Texas. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 4. Retrieved from http://web.caller.com/2012/pdf/EFS-Housing-Study_-July-2012.pdf Source: The University of Texas at San Antonio, “Strategic Housing Analysis” (July 2012) EFS_Chapter_1.indd 13 3/6/2013 5:35:54 PM

- 19. 14 CHAPTER 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter The shortage of qualified local candidates forces many companies to hire employees from outside the region and relocate them.8 This influx of transient workers has led to a housing shortage. The supply of temporary housing and hotel rooms is limited. Workers tend to reside in recreational vehicle parks or barracks-style, short- term housing units – also known as “man camps.”9 For additional information regarding Eagle Ford Shale play housing, see Chapter 2: Infrastructure. Research indicates that oil and gas industry demand for skilled labor will continue to remain strong.10 According to the Center for Community and Business Research (“CCBR”) at UTSA, as the play matures, the composition of its labor force will evolve, requiring a workforce capable of accommodating the play’s growth: The development of the Eagle Ford Shale has distinct phases, during which individual industries will experience varying levels of labor demand and evolving types of labor demanded. Thus, education and training requirements for workers will need to remain flexible enough to accom- modate the vacillating needs of industry. For example, during the exploration phase counties will see a rise in the need for occupations dealing with mineral leasing, site construction/management, drill- ing rig support, and material transport. As companies shift into the production and processing phase of operations, they require a workforce composed of business management, administrative support and the processing of gas, oil and condensates occupations.11 For the Eagle Ford Shale region to establish and maintain a local workforce capable of meeting industry de- mand, area residents must acquire technical skills and training.12 Most of the rural communities within the region rely on local community colleges for affordable training and vocational education, but decreases in en- rollment and funding have hindered the ability of these institutions to expand oil and gas-related programs.13 8 Ibid. 9 Center for Community and Business Research, Institute for Economic Development. (2012, May). Economic impact of the Eagle Ford Shale. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 56. Retrieved from http://ccbr.iedtexas.org/index. php/Download-document/52-Eagle-Ford-Shale-Final-Report-May-2012.html 10 Kamal, A. College of Architecture, Center for Urban and Regional Planning Research. (2012, July). Strategic housing analy- sis - sustainable choices for the growing demand for housing in the Eagle Ford Shale area of South Texas. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 4. Retrieved from http://web.caller.com/2012/pdf/EFS-Housing-Study_-July-2012.pdf 11 Center for Community and Business Research, Institute for Economic Development. (2012, October). Workforce analysis for the Eagle Ford Shale, executive summary. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 3. 12 Kamal, A. College of Architecture, Center for Urban and Regional Planning Research. (2012, July). Strategic housing analy- sis - sustainable choices for the growing demand for housing in the Eagle Ford Shale area of South Texas. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 4. Retrieved from http://web.caller.com/2012/pdf/EFS-Housing-Study_-July-2012.pdf 13 Strause, G. (2011, August 24). Stated at the Eagle Ford Shale Task Force meeting on workforce development, Beeville, Texas. EFS_Chapter_1.indd 14 3/6/2013 5:35:55 PM

- 20. 15 CHAPTER 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter The Eagle Ford Shale Task Force (“Task Force”) met to discuss the play’s urgent labor demand, the opportunity to satisfy that demand with local labor, and the challenge of meeting and sustaining industry’s diverse workforce needs. TASK FORCE MEETING At the Task Force meeting on workforce development, held at Coastal Bend College in Beeville on August 24, 2011, the following people made presentations:14 Glynis Strause, Community Relations Advisor for the Eagle Ford Shale, Conoco Phillips; Former Dean of Institutional Advancement, Coastal Bend College Genetha Turner, Attorney, Board Certified in Labor & Employment Law, Locke Lord LLP Manuel Ugues, Business Service Director, Workforce Solutions of the Coastal Bend Larry Demieville, Deputy Director, Workforce Solutions of the Coastal Bend Kirk Spilman, Regional Vice President-Eagle Ford, Marathon Oil Susan Spratlen, Vice President, Sustainability & Communication, Pioneer Natural Resources Task Force member Glynis Strause of Conoco Phillips, who formerly served as Dean of Institutional Advance- ment for Coastal Bend College, described colleges’ assessments of gaps in workforce training, the resources necessary to sustain a qualified force for at least 20 years, and the importance of addressing long-term workforce issues. Strause identified four notable, industry-supported programs that will help meet the long-term employment goals of the energy sector in the Eagle Ford Shale. These programs are: (1) dual credit (concurrent enrollment in high school and college courses); (2) National Energy Education Development project (“NEED”); (3) Texas Alliance for Minorities in Engineering (“TAME”); and (4) the Danielle Dawn Smalley Foundation’s (“Smalley Foundation”) safety education programs. Strause stated that strategic alliances among industry, community colleges, universities, and non-profits are es- sential for supplying an adequately trained workforce in the Eagle Ford Shale. The Texas Workforce Commis- sion and consortia of Workforce Investment Boards, Strause added, are already implementing joint efforts in the Eagle Ford Shale area. 14 This was the second Eagle Ford Shale Task Force meeting. An introductory and agenda-setting meeting was held on July 27, 2011 in San Antonio. Elected officials in attendance at the introductory meeting: Senator Carlos Uresti, State Representative Tracy King, and State Representative Geanie Morrison. Elected officials in attendance at the workforce development meeting: U.S. Congressman Rubén Hinojosa and State Representative Jose Aliseda. EFS_Chapter_1.indd 15 3/6/2013 5:35:56 PM

- 21. 16 CHAPTER 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Manuel Ugues of Workforce Solutions of Coastal Bend presented his organization as a collaborative statewide network that assists both employers and employees during the recruitment and hiring process. Ugues described Workforce Solutions’ efforts to connect employers with skilled workers in the Eagle Ford Shale. He urged em- ployers to reach out to the organization for recruiting assistance. Task Force member Kirk Spilman of Marathon Oil addressed recruitment issues from an industry perspective. Marathon Oil has quickly scaled its workforce to match the increased activity in the Eagle Ford Shale, where only a few years ago they had no employees.15 Spilman described best practices to meet workforce challenges, such as recruiting locally, partnering with educational institutions, recruiting from untapped or underutilized sources, and remaining competitive. Much of the play’s success, Spilman said, can be attributed to the com- munities within the region, who have embraced the opportunities the play offers by helping the oil and gas industry meet its needs. Recruitment Spilman reiterated the recruiting difficulties for companies in the region, including small rural populations, the shortage of experi- enced labor, and the various issues that arise when relocating work- ers. According to Spilman, companies must explore previously untapped or underutilized recruitment sources to meet immedi- ate labor needs. For example, Marathon Oil has increasingly hired military candidates. The proximity of the Eagle Ford Shale to San Antonio, a military hub, is conducive to this practice. Marathon Oil’s Eagle Ford Asset Team has successfully used military hiring initiatives for recruiting positions in health, environment, and safe- ty; engineering; construction; instrumentation and electrical; and other positions. Marathon Oil values military candidates for their discipline, transferable trade skills, and aptitude for leadership. Marathon Oil has also increased its emphasis on traditional recruitment methods, including local and national advertising, career fairs, the use of recruiting agencies, and retained searches. In order to remain competitive in the recruiting and retention arenas, Spilman said companies must remain alert to shifting market conditions, respond quickly, and make adjustments regularly. Salary surveys show upward trends in base pay for petroleum and reservoir engineers, geologists, and other key field positions. Spilman said that company benefits, such as restricted stock and enhanced vacation, have increasingly become part of general employee and new hire pack- ages, as have work schedules that allow work/life balance. 15 As of November 2012, Marathon Oil had 180 employees and an estimated 3,000 contractors working in the play. (Spilman, K. (2012, November 13). Stated at the Eagle Ford Shale Task Force re-cap meeting, San Antonio, Texas.) “Energy companies must explore previously untapped or underutilized recruitment sources, for example the military, to meet immediate labor needs.” (Kirk Spilman, Eagle Ford Shale Task Force member and Regional Vice President-Eagle Ford, Marathon Oil) EFS_Chapter_1.indd 16 3/6/2013 5:35:57 PM

- 22. 17 CHAPTER 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Ugues expanded upon Spilman’s endorsement of recruiting agencies and networks. He provided details of the ongoing efforts to identify and recruit candidates capable of meeting industry’s qualifications. Workforce Solutions of the Coastal Bend, for example, offers job seekers free training, financial assistance for childcare, and education incentives. The organization serves employers as well, by recruiting, screening, and matching ap- plicants.16 Spilman and Ugues each reported on how pre-employment screenings, while important, often further narrow the pool of qualified candidates during the hiring process. Spilman cited a lack of adequate medical facilities for pre-employment testing/physicals. Ugues noted that many truck drivers and rig workers fail pre-employment screenings, such as drug tests, making these positions more difficult to fill. In 2011, Workforce Solutions sur- veyed 10 Eagle Ford Shale employers and determined that one in four applicants failed a company screening.17 16 Workforce Solutions of the Coastal Bend. (2010). About us. Retrieved from http://www.workforcesolutionscb.org/index. php?option=com_content&view=article&id=49&Itemid=55 17 Ugues, M. (2011, August 24). Stated at the Eagle Ford Shale Task Force meeting on workforce development, Beeville, Texas. Source: The University of Texas at San Antonio, “Strategic Housing Analysis” (July 2012) EFS_Chapter_1.indd 17 3/6/2013 5:35:58 PM

- 23. 18 CHAPTER 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Finding qualified truck drivers with Commer- cial Driver’s License (“CDL”) certification is a struggle for employers, according to Ugues. Spilman agreed that drivers are highly sought after in the Eagle Ford Shale, as every phase of development requires their services. Ac- cording to the CCBR, in 2011, truck drivers had the most significant occupational im- pact, representing almost five percent of the 38,000 industry jobs supported by the 14 top producing Eagle Ford Shale counties.18 Concurring that properly licensed drivers are a crucial component of industry’s ability to operate safely and efficiently, Strause reported that most of the colleges in the Eagle Ford Shale play have ex- panded their CDL course offerings. Sustainable Workforce Development Given the obstacles that Eagle Ford Shale-area communities are facing as they attempt to satisfy current labor demand, meeting industry’s long-term workforce needs will present similar challenges. To foster sustainable sources of skilled, local candidates, Spilman said Marathon Oil and some industry peers partner with local educational institutions. Spilman explained that these partnerships may not yield immediate results, but they are an integral long-term investment in the region’s future workforce. For example, Marathon Oil currently of- fers scholarships for petroleum technology certificate and degree programs at Coastal Bend College in Beeville, Texas. A number of colleges in the Eagle Ford Shale region are offering oil and gas-related classes and field training, including: Alamo Colleges, Coastal Bend College, Del Mar College, Laredo Community College, Southwest Texas Junior College, Sul Ross Rio Grande College, The University of Texas at San Antonio, Victoria College, and Texas A&M International University (“TAMIU”). After a successful Eagle Ford Shale Stakeholder’s Sum- mit, at which Senator Judith Zaffirini (District 21) stated that TAMIU would be the ideal home for a petroleum engineering program, TAMIU accelerated its plans to launch a petroleum engineering degree program.19 18 Center for Community and Business Research, Institute for Economic Development. (2012, October). Workforce analysis for the Eagle Ford Shale, executive summary. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 7. 19 Senator Judith Zaffirini held an Eagle Ford Shale Stakeholders Summit in Laredo on October 23, 2012. Finding qualified truck drivers with Commercial Driver’s License certification is a struggle for employers; in response, most colleges in the Eagle Ford Shale have expanded their CDL course offerings. EFS_Chapter_1.indd 18 3/6/2013 5:35:59 PM

- 24. 19 CHAPTER 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Coastal Bend College partners with several organizations to provide what Strause described as “world-class” field training to students, who can currently enroll in courses such as drilling industry introduction (elementary drilling), corrosion basics, petroleum safety and environmental hazards (H2S Training), technology/technician/ management (supervisory skills), focused oil spill response training, and CDL/driving safety courses.20 The efforts of the region’s institutions of higher education do not stop there, Strause reported. Most of the col- leges in the Eagle Ford Shale play have expanded the following courses: CDL; Occupational Safety and Health Administration and SafeLand courses for safety training and new hire orientation; HazMat and HazWhopper training; instrumentation and electricity; supervisory leadership skills; and gauging. Strause also highlighted that Pioneer Natural Resources has partnered with Coastal Bend College to provide safety and driver training and helped fund the college’s Petroleum Industry Training Room. However, according to Strause, securing funding for community colleges and other programs that train Eagle Ford Shale employees is an ongoing struggle. Many students choose to directly enter into occupations that re- quire minimal education and training, instead of pursuing a higher-level degree. When students do not enroll in workforce-related courses, state funding for community college workforce education, as well as financing from tuition, are limited. Continuing the discussion regarding education and training, Strause and Spilman pointed out that many high schools, such as Pleasanton High School in Pleasanton, Texas, are implementing industry-specific course cur- ricula. Strause endorsed dual credit programs, which offer concurrent high school and college enrollment. Stu- dents enrolled in such programs receive simultaneous high school and college credit, fast-tracking them toward industry careers or allowing them to enter college with up to 62 hours of college credit. Strause said dual credit programs will help meet the long-term employment needs of industry operating in the shale play. Strause spotlighted three additional industry-supported, education-based programs that will help facilitate the goal of sustainable employment in the Eagle Ford Shale region: (1) NEED; (2) TAME; and (3) the Smalley Foundation safety education programs. Strause lauded oil and gas industry companies, such as ConocoPhillips, who have helped fund the NEED Proj- ect, which offers an energy-related curriculum and aims to identify and inspire Science, Technology, Engineer- ing, and Math (“STEM”) students from kindergarten through high school.21 Spilman noted that Marathon Oil currently partners with the Karnes City Independent School District Foundation to promote STEM throughout all grade levels. 20 Strause, G. (2011, August 24). Stated at the Eagle Ford Shale Task Force meeting on workforce development, Beeville, Texas. 21 National Energy Education Development Project. (2013). About NEED. Retrieved from http://www.need.org/About-NEED EFS_Chapter_1.indd 19 3/6/2013 5:36:00 PM

- 25. 20 CHAPTER 1 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter TAME promotes minority interest and participation in the engineering, science, and computer science profes- sions.22 Strause explained how these initiatives nurture opportunities for future engineers. For example, third through seventh grade students may be offered an educational precursor to help them distinguish between dif- ferent types of engineering and acquire a sense of what it means to be an engineer from a professional stand- point.23 Strause praised the efforts of the Smalley Foundation, a memorial non-profit formed to promote safety aware- ness and training for those who live, work, and play near our nation’s oil and gas sites and pipelines.24 The Smalley Foundation indoctrinates first responders in emergency protocols for natural gas leaks and petroleum product spills, as well as the fires that may result from either incident.25 The foundation also trains industry contractors, such as excavators, and partners with civic and student groups to promote appropriate behaviors and necessary precautions to exercise when encountering oil and gas-related equipment, pipelines, and storage tanks.26 22 Texas Alliance for Minorities in Engineering. (2013). About us. Retrieved from http://www.tame.org/about 23 National Energy Education Development Project. (2013). Trailblazer. Retrieved from http://www.tame.org/programs/trail- blazer 24 Danielle Dawn Smalley Foundation, Inc. (2008). Retrieved from http://www.smalleyfnd.org 25 Ibid. 26 Ibid. A number of colleges in the Eagle Ford Shale are offering oil and gas-related classes and field training, including Alamo Colleges, Coastal Bend College, Del Mar College, Laredo Community College, Southwest Texas Junior College, Sul Ross Rio Grande College, The University of Texas at San Antonio, Victoria College, and Texas A&M International University. EFS_Chapter_1.indd 20 3/6/2013 5:36:02 PM

- 26. 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING The increase in Eagle Ford Shale drilling and production is the source of remarkable economic benefits. At the same time, the increased activity has heightened infrastructure challenges for the region’s communities. Truck traffic and road quality, pipeline placement and safety, and a shortage of affordable housing are top concerns. EFS_Chapter_2.indd 21 3/6/2013 5:39:29 PM

- 27. 22 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Truck Traffic and Road Quality Increased drilling and production in the Eagle Ford Shale, compounded by the limited number of existing pipelines, has resulted in an unprecedented amount of truck traffic on state and county roads. According to a study conducted by the Texas Department of Transportation (“TxDOT”), in Webb and La Salle Counties from 2009 to 2012, traffic increased in the least affected areas of Interstate Highway 35 (“IH-35”) by 24 percent; it increased in the most affected areas of IH-35 by 86 percent.1 Until an adequate pipeline network is in place, trucks will be responsible for transporting the vast majority of the region’s oil and condensate to market.2 The need for these heavy transport vehicles throughout the region, particularly in Dimmit and La Salle Counties, has led to an increase in traffic, premature deterioration of roads and bridges, and public safety concerns. Pipeline Placement and Safety Pipelines are normally the preferred method for transporting oil, natural gas, petroleum liquids, and refined products be- cause of their transportation efficiency. In addition, pipelines greatly reduce truck traffic and air pollution and have the low- est spill rate of any other type of carrier (e.g., ships, barges, trucks, and railcars).3 Currently, Texas is home to more than 350,000 miles of pipelines. Increases in oil and gas production have created an urgent de- mand for pipelines in the Eagle Ford Shale, and the Railroad Commission (“Commission”) projects significant growth as shale play production expands. Already, several billion dollars- worth of energy pipeline projects are under development in the Eagle Ford Shale.4 Local communities have expressed concerns about how the development of these mas- sive projects will affect them. 1 Texas Department of Transportation, Laredo District. (2012, October 23). Eagle Ford Shale: impacts to the transportation system. Presented by Melissa Montemayor at the Eagle Ford Shale stakeholders summit, Laredo, Texas. Available at http://www. tamiu.edu/adminis/vpia/events/documents/102312TxDOTEFSSSumiitPresentationMMontemayor.pdf 2 Center for Community and Business Research, Institute for Economic Development. (2012, May). Economic impact of the Eagle Ford Shale. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 52. Retrieved from http://ccbr.iedtexas.org/index. php/Download-document/52-Eagle-Ford-Shale-Final-Report-May-2012.html 3 American Association of Pipelines. (2012). Why pipelines? Retrieved from http://www.aopl.org/aboutPipelines/?fa=pipelinesI nTheUS 4 Center for Community and Business Research, Institute for Economic Development. (2012, May). Economic impact of the Eagle Ford Shale. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 33. Retrieved from http://ccbr.iedtexas.org/index. php/Download-document/52-Eagle-Ford-Shale-Final-Report-May-2012.html Pipelines are normally the preferred method for transporting TEXAS PIPELINES Pipeline Commodity Natural Gas Crude Oil Product Other EFS_Chapter_2.indd 22 3/6/2013 5:39:30 PM

- 28. 23 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Housing The surge in drilling activity has resulted in a housing shortage across the region. Throughout Eagle Ford Shale counties, there is consistently not enough housing (temporary or permanent) to accommodate the influx of oil field workers. This shortage has led to higher demand for both permanent and temporary housing, such as ho- tels, apartment complexes, recreational vehicle parks, and barracks-style, short-term housing units – also known as “man camps.”5 As a result of such demand, rent has increased across the Eagle Ford Shale.6 The Eagle Ford Shale Task Force (“Task Force”) met with representatives from trucking and pipeline industries, the oil and gas industry, state and local governments, and a private developer to engage in a dialogue about these issues and to discuss reasonable solutions. Housing Stock by County in 2000 Housing Stock by County in 2010 5 Ibid, p. 58. 6 Kamal, A. College of Architecture, Center for Urban and Regional Planning Research. (2012, July). Strategic housing analy- sis - sustainable choices for the growing demand for housing in the Eagle Ford Shale area of South Texas. San Antonio, TX: The University of Texas at San Antonio, p. 4. Retrieved from http://web.caller.com/2012/pdf/EFS-Housing-Study_-July-2012.pdf. Source: The University of Texas at San Antonio, “Economic Impact of the Eagle Ford Shale” (October 2012) EFS_Chapter_2.indd 23 3/6/2013 5:39:31 PM

- 29. 24 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter TASK FORCE MEETING At the Task Force meeting on infrastructure, held at the Chisholm Trail Heritage Museum in Cuero on September 28, 2011, the following people made presentations:7 Paul Woodard, President, J&M Premier Services Brian Schoenemann, Area Engineer, Texas Department of Transportation James Mann, Partner, Duggins, Wren, Mann & Romero, LLP Brian Frederick, Senior Vice President, Southern Region, DCP Midstream Greg Brazaitis, Chief Compliance Officer, Energy Transfer Christian Noll, Manager of Multifamily and Single Family Development Programs, Texas Department of Housing & Community Affairs Bob Zachariah, Founder, President and CEO, HotelWorks Development, LLC Truck Traffic and Road Quality Oil and gas development has significantly increased road traffic by heavy trucks in rural areas, where most roads were originally built for light-duty use. The traffic and specialized equipment associated with drilling and pro- duction puts a strain on local roads that leads to premature asphalt wear and tear, ripples, potholes, and torn shoulders. To illustrate the scope of the challenge, Brian Schoenemann, Area Engineer for TxDOT, presented research indicating that almost 1,200 loaded trucks are required to bring one gas well into production; over 350 are required per year for maintenance of a gas well; and almost 1,000 are needed every five years to re-fracture a well.8 Source: Texas Department of Transportation, “Roads for Texas Energy” (December 2012) 7 State Representative Tracy King and State Representative Geanie Morrison attended the meeting. 8 Barton, J. (2011, September 28). Energy sector impacts to Texas’ transportation system. Presented by Brian Schoenemann at the Eagle Ford Shale Task Force meeting on infrastructure, Cuero, Texas. LOADED TRUCKS PER GAS WELL Activity Number of Loaded Trucks Bring well into production 1,184 Maintain production (each year) Up to 353 Refracturing (every 5 years) 997 EFS_Chapter_2.indd 24 3/6/2013 5:39:32 PM

- 30. 25 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter The service life of highway systems and Farm-to-Market (“FM”) roads has been reduced by an average of 30 percent due to natural gas well operations and an average of 16 percent due to crude oil well operations.9 The original estimated annual impacts are: over $1 billion for the FM road system; $2 billion for the state highway system; and over $1 billion for local roads.10 To further illustrate the breadth of this issue, the TxDOT study focused on rigs and wells. The infrastructure impact of ancillary activities, notably pipeline construction (as de- tailed later in this chapter), was not included in these calculations. At the meeting, Task Force members discussed concerns about the legal, financial, and political limits on the ability of county property tax increases to finance road repair. Some members voiced their support for a plan to return severance tax revenue to the counties to address infrastructure needs. 9 Ibid. 10 Texas Department of Transportation, Task Force on Texas’ Energy Sector Roadway Needs. (2012, December). Report to the Texas Transportation Commission, p. 2. Retrieved from http://ftp.dot.state.tx.us/pub/txdot-info/energy/final_report.pdf The activity in the Eagle Ford Shale has also seen a dramatic increase in heavy truck traffic, with a resulting strain on roads and bridges, along with congestion and safety issues. Several methods of financing road needs have been discussed: “Severance taxes could be used as a self-regulating funding source, almost immediately available to meet road-financing needs in oil and gas producing areas of the state.” (Judge Daryl Fowler, Eagle Ford Shale Task Force Member and DeWitt County Judge) “An alternative funding proposal would be to biennially appropriate a portion of the Rainy Day Fund for a grant-in-aid program to counties, based on need. One measure of need could be oil and gas activity in local counties.” (James LeBas, fiscal consultant to the Texas Oil & Gas Association and other industrial taxpayers) EFS_Chapter_2.indd 25 3/6/2013 5:39:34 PM

- 31. 26 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter According to Task Force member and DeWitt County Judge Daryl Fowler, DeWitt County’s experiences with truck traffic and road quality are a typical example of what is occurring throughout the Eagle Ford Shale play. From 2000 to 2007, prior to the drilling of the first Eagle Ford Shale horizontal well, the Commission issued an annual average of 69 new and amended drilling permits to operators in DeWitt County. The annual permit volume jumped to 355 in 2011 and to 449 in 2012.11 Fowler explained that the most significant and visible change occurring with horizontal drilling is the size of the drilling pad. Drilling pads are now larger, in order to support rigs capable of drilling to depths of 18,000 feet (combined vertical and lateral lines) and to utilize hydraulic fracturing completion methods. A typical county- maintained road is within a 40-foot right-of-way and constructed of four to six inches of gravel base. These county roads were not adequately built to handle the present volume of traffic needed to build a pad site, which requires between 270 and 315 loads of gravel, and the weight of transporting a drilling rig, which may reach three million pounds per movement.12 According to a 2012 study conducted by Naismith Engineering, Inc. of Corpus Christi, the anticipated oil field traffic demand, including public usage, will require the construction of stronger and wider roads in DeWitt County.13 The cost of providing a county road system designed to meet the anticipated traffic demand arising from drilling another 3,250 wells in DeWitt County at 65-acre spacing is approximately $432 million.14 Some roads require annual maintenance at $70,000-80,000 per mile.15 However, other roads need basic reconstruction at a cost of up to $920,000 per mile, and roads that already handle the traffic meant for an FM system can cost up to $1.9 million per mile to rebuild when the costs of additional right-of-way, engineering, fence building, and utility moving are considered.16 Fowler contended that infrastructure costs far outpace a county’s ability to raise revenue from a local property tax, even with the increasing tax base created by the new mineral wealth. The Property Tax Code is designed to push property tax rates lower when the tax base increases,17 thus local tax rates (though not tax revenues) have 11 Search results at www.rrc.state.tx.us for Karnes County and DeWitt County P-4 drilling applications. 12 Fowler, D., Afflerbach, C., Oliver, J., Kuecker, D., & Pilchiek, J. DeWitt County Commissioners Court, Naismith Engineering, Inc. (NEI). (2012). Road damage cost allocation study - DeWitt County. Retrieved from website: http://web.caller.com/2012/pdf/ DeWitt-County-Road-Damage-Cost-Allocation-Study.pdf 13 Ibid. 14 Ibid. 15 Ibid. 16 Ibid. 17 See Tex.Tax Code § 26.04(c) (describing formula for determination of a county’s effective tax rate); also see Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts (2012), Truth-in-Taxation Guide 9–12. Retrieved from http://www.window.state.tx.us/taxinfo/proptax/tnt11/ pdf/96-312.pdf EFS_Chapter_2.indd 26 3/6/2013 5:39:35 PM

- 32. 27 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter tended to decline with the development of oil and gas fields.18 Road and bridge maintenance budgets doubled or tripled in many counties and forced elected officials to exceed tax rollback ceilings in order to meet expanded maintenance needs.19 The question has been raised whether the county property tax, under current calculations and limits, can or should continue to shoulder such a large share of the burden for financing local road needs. According to the most recent Biennial Revenue Estimate of the Texas Comptroller (“Comptroller”), sales taxes (including motor vehicle sales taxes) and oil and gas severance taxes will provide the largest sources of tax rev- enue for fiscal year (“FY”) 2015.20 Severance taxes are imposed on the first sale of every barrel of oil or liquids and every thousand cubic feet (“Mcf”) of natural gas.21 The Comptroller indicates that $323 million was col- lected on production from 24 Eagle Ford Shale counties in FY 2011.22 According to Fowler, there is very cogent reasoning behind arguments favoring the use of severance taxes to fund repair of the county road system and the state highway system. The severance tax correlates with the vol- ume of wells drilled and completed, which in turn corresponds to the damage inflicted upon area road systems. Thus, as the volume of new permitted wells eventually declines, so should the rate of road damage and the revenue from severance tax collections. Also, Fowler noted that the severance tax is collected immediately upon the sale of the taxed oil and gas product, without a delay of up to 23 months, as is the case with the collection of property taxes. Therefore, Fowler said, severance taxes could be viewed as a self-regulating funding source that is almost immediately available to meet road financing needs in oil and gas producing areas of the state. Oil and gas severance taxes are deposited in the state’s General Revenue Fund, but 75 percent of the annual severance tax revenue that exceeds the level of severance tax collections in 1987 is transferred to the Economic Stabilization Fund, also known as the “Rainy Day Fund.”23 Under a proposal being advanced by Fowler, a pro- portional share of the severance tax revenue would be returned to the counties where the tax was derived and provide timely funds for road repairs at the county level.24 18 Fowler, D. (2012). Testimony before the House County Affairs Committee. Retrieved from http://www.legis.state.tx.us/tlodocs/82R/handouts/C2102012102410001/e5650987-5d8e-4aad-8c33-e7f7f8d225fd.PDF 19 DeWitt County. (2012). Fiscal year (“FY”) 2013 proposed budget - DeWitt County, Texas. Retrieved from http://www. co.DeWitt.tx.us/ips/export/sites/DeWitt/downloads/Fiscal_Year_2013_Proposed_Budget.pdf 20 Total state tax collections in the 2014-2015 biennium are estimated to be $96.9 billion. Of this, the sales and motor vehicle sales taxes comprise $63 billion, and oil and gas production taxes comprise $7.1 billion. Retrieved from http://www.window.state. tx.us/finances/Biennial_Revenue_Estimate/bre2014/BRE_2014-15.pdf 21 Tex. Tax Code Ann. § 202001 et seq. (West 2012) (Oil Production Tax). 22 State Comptroller data obtained by open records request (on file with Judge Daryl Fowler, DeWitt County Courthouse). Ac- cessed via personal interview with Fowler. (2012, November). 23 The legislature created the Economic Stabilization Fund in 1988 by adding Section 49-g to Article III of the Texas Constitu- tion; For other statutory provisions governing the Fund, see Tex. Educ. Code ch. 42; Tex. Tax Code §§ 201.404, 202.353. 24 Fowler, D. (2012). Testimony before the House County Affairs Committee. Retrieved from http://www.legis.state.tx.us/tlodocs/82R/handouts/C2102012102410001/e5650987-5d8e-4aad-8c33-e7f7f8d225fd.PDF EFS_Chapter_2.indd 27 3/6/2013 5:39:36 PM

- 33. 28 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter An alternative proposal (which would not disturb the century-long arrangement under which counties tax oil and gas in place underground while the state taxes oil and gas when it is produced) would be to biennially ap- propriate a portion of the Rainy Day Fund for a grant-in-aid program to counties, based on need. One measure of need could be oil and gas activity in local counties. According to Fowler, local property taxes are the only real revenue source available to local governments seeking funds for infrastructure investment and repairs. However, statutory provisions limit the ability of local govern- ment to increase revenue.25 Fowler explained that over the last two years in DeWitt County, the tax base has doubled in value and the effective tax rate has been cut in half.26 Using the statutory formulas, DeWitt County would have been limited to a $472,000 increase in tax revenue for its FY 2013 budget, if the tax rate were set at the rollback limit, which yields an eight percent revenue increase.27 Knowing that their financial needs were greater than the $472,000 rollback rate calculation, the DeWitt County Commissioner’s Court, led by Fowler, elected to hold the county’s maintenance and operating tax rate at the previous year’s rate, in anticipation of raising $3.6 million new tax dollars.28 That additional tax revenue repre- sents a 53 percent increase from FY 2012 to FY 2013.29 This decision resulted from several public hearings and a final vote by the county commissioners to exceed the rollback tax rate.30 Following the vote, taxpayers have a 90-day window within which to gather signatures on a petition calling for a rollback election.31 The election, if successful, forces the county to withdraw the higher tax rate and restructure its budget to reflect the limit placed on county revenue collection – an amount no more than eight percent greater than the previous year’s revenue collection.32 Fowler explained that amid these unique fiscal challenges, the combined road and bridge precinct budgets for DeWitt County will exceed $5 million in FY 2013 – consuming 35 percent of total county appropriations. A decade ago, Fowler noted, the county road and bridge budget was only $1.4 million, comprising less than 26 percent of the county budget. 25 Notes from November 2012 interview with Judge Daryl Fowler, DeWitt County. (on file with the Railroad Commission). 26 Ibid. 27 Ibid. 28 Ibid. 29 Ibid. 30 Ibid. 31 Tex. Tax Code § 26.07 (West 2013) (describing procedures for a rollback election). 32 Notes from November 2012 interview with Judge Daryl Fowler, DeWitt County. (on file with the Railroad Commission). EFS_Chapter_2.indd 28 3/6/2013 5:39:37 PM

- 34. 29 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Fowler offered a cautionary hypothesis of changes likely to occur in the near future. If market forces create a renewed demand for natural gas drilling within the next few years, an additional 250,000 acres of DeWitt County will be attractive to exploration, subjecting 347 more miles of county road to the forces of rapid decline. Engineers are already developing secondary methods of recovery for extracting the estimated ultimate recovery of 500,000 barrels of oil per drilling unit in the known reservoirs. Methods to reach even deeper formations capable of yielding more hydrocarbons are likely to be discovered as well. Fowler concluded, “Although we cannot know when things will occur, it is apparent to county government officials that the financial needs of providing a public road system capable of supporting the industry and the local needs are far greater than what DeWitt County’s $15 million total annual revenue can provide.”33 In addition to road quality and funding, Task Force members discussed how irresponsible driving behavior, combined with poor road conditions, has impacted public safety. The Houston Chronicle reported a significant rise in traffic accidents in the Eagle Ford Shale: In the counties most directly affected by Eagle Ford drilling, the biggest jump in fatal traffic ac- cidents has involved commercial vehicles, according to an analysis of TxDOT numbers, increas- ing from six in 2008 to 24 last year [2011] … At first glance, the increase in crashes - and fatal crashes - appears to be easily explained by math. More people equals more crashes. But officials say there is more to the upswing. It’s fatigued drilling workers, driving home after a long shift, sometimes on unfamiliar roads. It’s people in a hurry. It’s not paying attention. It’s bad roads.34 At the meeting, the Task Force expressed support for trucking companies partnering with TxDOT to develop a program that will alert companies when their drivers receive moving violations or driver’s license suspensions. The Task Force also endorsed the creation of road usage agreements, or trucking plans, between operators and local authorities, which include the following commitments by operators: 1. Avoid peak traffic hours, school bus hours, and community events. 2. Establish overnight quiet periods. 3. Ensure adequate off-road parking and delivery areas at all sites to avoid lane and road blockage. Subsequent to the meeting, the Task Force voiced its support for the TxDOT Task Force on Texas’ Energy Sector Roadway Needs (“TxDOT Task Force”). TxDOT created the task force in March 2012, “…to find ways to address the impact on the state’s infrastructure of increased energy exploration and production.”35 The 33 Ibid. 34 Konnath, H. (2012, July 9). Traffic deaths soar in Eagle Ford Shale areas. Houston Chronicle. Retrieved from http://www. chron.com/news/houston-texas/article/Traffic-deaths-soar-in-Eagle-Ford-Shale-areas-3691999.php 35 Texas Department of Transporation. (2012). Roads for Texas energy. Retrieved from http://www.roadsfortexasenergy.com/ EFS_Chapter_2.indd 29 3/6/2013 5:39:38 PM

- 35. 30 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter TxDOT Task Force was comprised of representatives from counties and other state agencies and organizations, including the following: The Railroad Commission The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Texas Department of Public Safety Texas Department of Motor Vehicles America’s Natural Gas Alliance Association of Energy Service Companies Midland-Odessa Transportation Alliance Texas Alliance of Energy Producers Texas Competitive Power Advocates Texas Farm Bureau Texas Independent Royalty Owners Association Texas Motor Transportation Association Texas Oil and Gas Association Texas Pipeline Association The Wind Coalition36 The TxDOT Task Force was composed of four subcommittees: (1) Safety; (2) Innovation and Prevention; (3) Public Awareness; and (4) Funding. Stacie Fowler, the Commission’s Director of Government Affairs, and Polly McDonald, the Commission’s Pipeline Safety Director, represented the Commission on the TxDOT Task Force, serving on the Safety and Public Awareness Subcommittees. As a result of this partnership, the Commission shares geographic informa- tion system (GIS) information on permitted wells so that TxDOT is better equipped to predict future strains on infrastructure. The Commission has also developed a partnership with DPS, through which Commission inspectors and State Troopers patrol together to find drivers who violate regulations, such as illegal waste haul- ing (which can cause oil slicks and potentially leads to accidents). The Commission’s proposed amendments to Statewide Rule 8 would strengthen requirements for waste hauler vehicle operation, design, and maintenance, in order to prevent leaks during transportation. (See Chapter 5: Railroad Commission Regulations.) Pipelines At the Task Force meeting, Task Force member Greg Brazaitis, Chief Compliance Officer for Energy Transfer, disclosed that the construction of one, 20-inch crude oil pipeline running 50 miles would displace 1,250 tank truck trips per day.37 Although the pipeline industry is building pipelines at a record pace, demand still outpaces 36 Ibid. 37 Brazaitis, G. (2011, September 28). Stated at the Eagle Ford Shale Task Force meeting on infrastructure, Cuero, Texas. Pipelines are normally the preferred method for transporting oil, natural gas, petroleum liquids, and refined products because of their transportation efficiency. Texas is home to more than 350,000 miles of pipelines. EFS_Chapter_2.indd 30 3/6/2013 5:39:39 PM

- 36. 31 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter supply. Brazaitis added that pipeline construction timetables are impacted by new federal permitting regulations and further hampered by the uncertainty surrounding the recent Texas Supreme Court decision in Texas Rice Land Partners, Ltd. v. Denbury Green Pipeline-Texas, LLC.38 Common carrier pipelines in Texas have a statutory right of eminent domain, subject to the “public use” re- quirement articulated by the Texas Supreme Court in Denbury.39 Common carrier pipelines may include those that transport oil, oil products, gas, carbon dioxide, salt brine, sand, clay, liquefied minerals, or other mineral solutions. For example, a pipeline transporting hazardous liquids could be a common carrier, and as such, would have the right of eminent domain. Natural gas pipelines (other than certain gathering lines) are generally classified as gas utilities, which also traditionally have the power of eminent domain. The Legislature defines “common carrier” and “gas utility,” and the Commission applies the Legislature’s definitions when exercising its jurisdiction.40 The Commission does not regulate any pipelines with respect to the exercise of their eminent domain powers. Generally, all pipelines operating in Texas must have a T-4 pipeline permit, issued by the Commission. (See Ap- pendix A.2 for Application.) There are two exceptions: lines that never leave an oil or gas production lease, and distribution lines to homes and businesses that are part of a natural gas or LP-gas distribution system.41 An application for a T-4 Permit must be filed by an operator with an approved Organization Report (“P-5”) on file with the Commission. (See Appendix A.3 for P-5 Form Application.) The T-4 Permit application must include a digitized map of the pipeline(s) to be covered by that T-4 Permit. A P-5 and financial security (e.g., bond, let- ter of credit, cash deposit, or well-specific plugging insurance policy) are required of all companies performing operations within the jurisdiction of the Commission.42 The Texas Supreme Court’s decision in Denbury has created a level of uncertainty regarding the process to de- termine a pipeline’s common carrier status. In its opinion, the Court stated that the filing of a T-4 permit and self-designation as a common carrier alone did not conclusively establish Denbury Green’s status as a common carrier and thus confer the power of eminent domain.43 The Court pointed out that it has long held that “the ultimate question of whether a particular use is a public use is a judicial question to be decided by the courts.”44 38 Texas Rice Land Partners, Ltd. v. Denbury Green Pipeline-Texas, L.L.C., 363 S.W.3d 192 (Tex. 2012) (holding that a pipeline company had to show a “public use” in order to exercise the power of eminent domain and that obtaining the designation of “common carrier” from the Commission was not conclusive, at least under present procedures ). 39 Tex. Nat. Resources Code § 111.019(a). 40 Tex. Nat. Resources Code § 111.001–111.003. 41 16 Tex. Admin. Code § 3.70. (2013) (Railroad Comm’n of Tex., Pipeline Permits Required). 42 16 Tex. Admin. Code § 3.78. (2013) (Railroad Comm’n of Tex., Fees and Financial Security Requirements). 43 Denbury, 363 S.W.3d at 198. 44 Ibid. EFS_Chapter_2.indd 31 3/6/2013 5:39:40 PM

- 37. 32 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter As noted above, the Commission does not regulate the exercise of eminent domain by pipelines and does not have authority to determine property rights. Therefore, rather than the final determination resting solely with the Commission, the issue of a pipeline’s common carrier status could be sub- ject to challenge in one or more of the 456 district courts across the state. This means that a pipeline traversing several counties may face challenges to its status as a common carrier in multiple district courts. Whether or not a pipeline is for public use is an essential determination for right-of-way ac- quisition where eminent domain must be used. The determination must be made in a timely manner. The Commission is committed to working with the Legislature to create a remedy for this issue that is fair and reasonable for pipeline companies and landowners alike. Task Force members, including representatives of pipeline companies, agreed that while it is imperative to build pipelines, local communities must be protected throughout the process. The Task Force members discussed guidelines and adopted the following advisements: 1. The placement of pipelines should avoid steep hillsides and watercourses where feasible. 2. Pipeline routes should take advantage of road corridors to minimize surface disturbance. 3. When clearing is necessary, the width disturbed should be kept to a mini- mum, and topsoil material should be stockpiled to the side because retaining topsoil for replacement during reclamation can significantly accelerate suc- cessful re-vegetation. 4. Proximity to buildings or other facilities occupied or used by the public should be considered, with particular consideration given to homes. 5. Unnecessary damage to trees and other vegetation should be avoided. 6. After installation of a new line, all right-of-way should be restored to conditions compatible with existing land use.45 Housing The final item on this Task Force meeting’s agenda was to address housing issues, such as rent increases and the lack of temporary housing – issues that affect many residents in the Eagle Ford Shale. Christian Noll, Manager of Multifamily and Single Family Development Programs for the Texas Department of Housing & Community Affairs, provided an overview of state and federal programs that are available to offset rent increases and assist 45 (September 28, 2011). Eagle Ford Shale Task Force meeting on infrastructure in Cuero, Texas Whether a pipeline is for public use is often an essential determination for right-of-way acquisition. The determination must be made in a timely manner. The Railroad Commission is committed to working with the Texas Legislature to create a remedy for this issue that would allow landowner and pipeline interests to be resolved at the Railroad Commission. EFS_Chapter_2.indd 32 3/6/2013 5:39:42 PM

- 38. 33 CHAPTER 2 INFRASTRUCTURE - ROADS, PIPELINES, HOUSING EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter displaced families. For example, the HOME Investment Partnerships Program, funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, is a program that expands the supply of decent, safe, affordable housing and strengthens public-private housing partnerships between units of general local governments, public hous- ing authorities, non-profits, and for-profit entities.46 Several Task Force members expressed a desire to see builders foster community development by placing more emphasis on permanent housing, rather than relying on short-term, temporary, and semi-permanent structures. Bob Zachariah, HotelWorks Development, LLC, a developer in the Eagle Ford Shale region, reported that many developers are reluctant to build permanent housing in certain areas because they are wary of boom and bust cycles. He also spoke about the ways in which local governments and communities can spur private investment in the region. The Task Force lauded the launching of the Housing and Land Use Analysis study that will be conducted by the Institute for Economic Development and the Center for Urban and Regional Planning Research within the Col- lege of Architecture at The University of Texas at San Antonio (“UTSA”).47 The study will analyze 15 counties in the Eagle Ford Shale region and provide them with a Land Use, Infrastructure, and Housing Plan Guide for the upcoming decade, which will include the following: 1. Economic analysis and projections 2. Population analysis and projections 3. Land use studies 4. Housing studies 5. Circulation and transportation 6. Infrastructure (utility systems, school systems production and midstream infrastructure) 7. Administrative controls 8. Quality of life and sustainability indicators The Task Force also endorses the UTSA-sponsored Municipal Capacity Building Workshop, which began in February 2013. The workshop helps Eagle Ford Shale government officials de- velop the capability to create comprehensive plans of action for developing sustainable, stable communities amid the fast pace of expansion precipitated by the oil and natural gas boom. 46 Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs. (2012.) HOME division. Retrieved from http://www.tdhca.state.tx.us/ home-division/index.htm. 47 The comprehensive study will cost $100,000 in professional and student labor, supply and data costs, and travel for research and presentations. UTSA anticipates that the project will commence in March 2013. The housing shortage in the Eagle Ford Shale region has led to a higher demand for both permanent and temporary housing, such as hotels, apartment complexes, recreational vehicle parks, and “man camps.” EFS_Chapter_2.indd 33 3/6/2013 5:39:43 PM

- 39. EFS_Chapter_2.indd 34 3/6/2013 5:39:43 PM

- 40. 3 WATER QUALITY AND QUANTITY Railroad Commission records do not include a single documented groundwater contamination case associated with hydraulic fracturing − a process that has been employed in Texas for more than 60 years. Unlike many other states in the nation, Texas has a comprehensive and mature regulatory framework in place to ensure the protection of usable quality groundwater. EFS_Chapter_3.indd 35 3/6/2013 5:38:46 PM

- 41. 36 CHAPTER 3 WATER QUALITY AND QUANTITY EAGLE FORD SHALE TASK FORCE Commissioner David Porter Water is an essential part of energy production. Water is used in exploration, drilling, stimulation (including hydraulic fracturing), and enhanced recovery processes. While the oil and gas industry uses both surface water and groundwater for exploration and production activi- ties, the latter is used more frequently.1 For example, in the Eagle Ford Shale, groundwater constitutes almost 90 percent of the new (i.e., not reused or recycled) water used for hydraulic fracturing.2 According to the most recent data from the Texas Water Development Board (“TWDB”), as presented in the 2012 State Water Plan (“State Water Plan”), “mining water use” (i.e., the water used in the exploration, develop- ment, and extraction of oil, gas, coal, aggregates, and other materials) represents 1.6 percent of the state’s total water use.3 In comparison, irrigation and municipal water use collectively represent 82.8 percent of water use in the state.4 1 Surface water generally refers to rivers, streams, lakes, bays, and other bodies of water; while groundwater generally refers to subterranean water. 2 Nicot, J., Reedy, R. C., Costley, R. A., & Huang, Y. (2012, September). Bureau of Economic Geology, Jackson School of Geosci- ences. Oil & gas water use in Texas: update to the 2011 Mining Water Use Report. Austin, TX: The University of Texas, p. 56. Retrieved from http://www.twdb.texas.gov/publications/reports/contracted_reports/doc/0904830939_2012Update_MiningWa- terUse.pdf 3 Texas Water Development Board (TWDB). 2012 State water plan, Ch. 3, p. 137 (Table 3.3). Retrieved from http://www.twdb. state.tx.us/publications/state_water_plan/2012/03.pdf 4 Ibid. WATER DEMAND 2010 Municipal 26.9% Manufacturing 9.6% Mining 1.6% Steam Electric 4.1% Livestock 1.8% Irrigation 55.9% EFS_Chapter_3.indd 36 3/6/2013 5:38:47 PM