European sovereign debt crisis

Download as PPTX, PDF11 likes12,369 views

The European sovereign debt crisis began in late 2009 as fears grew over rising private and government debt levels in Europe. Greece, Ireland, and Portugal were hit hardest initially, accounting for 6% of Eurozone GDP combined. By 2012, concerns had spread to Spain as well. The crisis impacted EU politics and led to leadership changes in affected countries. Key causes included rising household and government debts, trade imbalances, structural issues in sharing a currency without a common fiscal policy, monetary policy inflexibility within the Eurozone, and loss of investor confidence. Long term solutions proposed integrating fiscal policies more through options like a European fiscal union or common Eurobonds.

1 of 29

Downloaded 738 times

Recommended

European Debt Crisis

European Debt CrisisCharu Rastogi This presentation explores the causes of the European debt crisis, timeline of the crisis, its extent, how it is being addressed, who is to blamed for the crisis and how it affects us.

Euro Sovereign Debt Crisis

Euro Sovereign Debt CrisisShikher Kaushik An attempt to cover different facets of ESD Crisis . Following ppt enumerate how it all got started and draws out rationale behind the formation of EU.

Euro Crisis

Euro CrisisVIVEK KUMAR The document discusses the Eurozone debt crisis that began in 2008. Several European countries like Greece, Ireland, and Portugal faced collapsing financial institutions, high government debt, and rapidly rising bond yields. The crisis started with Iceland's banking system collapse and spread to other European countries and economies. While some countries joined the Eurozone over time, others did not meet the guidelines for borrowing set by the Maastricht Treaty, contributing to the debt crisis. Proposed solutions include electing less corrupt governments, reducing trade imbalances, restructuring debt, and greater economic cooperation across Eurozone countries.

European Sovereign Debt Crisis

European Sovereign Debt CrisisLakshman Singh The document summarizes the European sovereign debt crisis that began in 2008. It discusses the key events and causes of the crisis. The Eurozone debt crisis involved high government debt levels and collapsing financial institutions in Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain. Greece concealed its true budget deficit levels and had to accept multiple bailout packages. Ireland's crisis stemmed from a property bubble burst that caused bank losses. Spain spent heavily on bank bailouts. Portugal had decades of overspending. The EU and IMF provided emergency loans and austerity measures were implemented to remedy the crisis.

Eurozone debt crisis

Eurozone debt crisistomarricha The eurozone crisis began in 2007-2008 as a result of the global financial crisis. Countries like Greece, Portugal, Ireland, and Spain were hit especially hard due to fiscal deficits and housing bubbles. The crisis exposed flaws in the eurozone system like lack of coordination, supervision, and a centralized budget. To address the crisis, the European Financial Stability Facility was created to provide loans to struggling countries. Austerity measures have been implemented but long-term solutions are still needed like greater political and economic integration among eurozone members.

Euro Crisis

Euro CrisisRaj Choubey The document discusses the euro crisis that began in Greece in 2009. Greece had allowed large deficits from its central bank and government bonds to accumulate. When Greece's debt levels came to light in 2009, it became clear that the country could not repay its debts, marking the start of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe. The crisis spread to other eurozone countries as well. Proposed solutions involved providing long term loans to Greece and other countries in crisis, austerity measures to reduce deficits and debt levels, and recapitalizing struggling banks.

Euro debt crisis

Euro debt crisisPVAbhi The Eurozone consists of 19 European Union member states that have adopted the euro as their common currency. Several factors contributed to the European debt crisis that began in 2009, including different fiscal rules between eurozone countries, excessive borrowing by some countries like Greece, and the global recession caused by the United States. The crisis emerged as some countries could no longer repay or refinance their government debts without assistance. Germany ultimately took responsibility for repaying debts to prevent the collapse of the European Union.

European debt crisis

European debt crisistarunyc The European debt crisis began in late 2009 when revelations emerged that Greek government debt levels were much higher than originally reported. Several European countries, including Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Spain struggled with high debt levels that were exacerbated by the 2008 global financial crisis. While interest rates had dropped due to the Euro, countries like Greece and Italy took on large amounts of debt. Austerity measures have been implemented but growth remains low across Europe as countries struggle under high debt loads. The EU and IMF have implemented bailout programs but long term solutions around fiscal integration and stability remain works in progress.

Euro zone crisis

Euro zone crisisAjay Kumar the euro zone introduction and the reason for the crisis and its impact on the european countries and on the world

Greece crisis and its impact final ppt

Greece crisis and its impact final pptSumit Tamrakar Greece accumulated high levels of debt in the decade before the financial crisis when markets were liquid. This led to a sovereign debt crisis as the financial crisis deepened and liquidity dried up, making borrowing more difficult and expensive. The crisis impacted Greece through lower incomes, savings, capital flows and sector output like tourism and shipping that contribute significantly to GDP. The European Union, IMF and ECB implemented measures like bailout loans and austerity programs to reduce Greece's deficit while the ECB also engaged in bond purchases to increase confidence. Protests have occurred against austerity cuts while leaders debate solutions to the dilemma of whether to continue supporting Greece or risk default.

Euro zone crisis

Euro zone crisis Lovely Professional University The document discusses the Eurozone crisis that began in 2009. It started in Greece due to the country misreporting its economic statistics, which hid a large budget deficit. As the global financial crisis hit, it struggled with high debt and interest rates. Greece required a bailout package from the EU and IMF to avoid defaulting. The crisis spread to other southern European countries like Portugal, Italy, Ireland, and Spain, known as the PIIGS, who also had high debts and deficits. Austerity measures were implemented but caused economic hardships.

Eurozone debt crises

Eurozone debt crisesWordpandit The document discusses the Eurozone debt crisis, providing background on the origins of the euro currency and how debt levels grew unsustainably in Greece, Portugal, Italy and Spain (PIIGS countries). It explains that lack of fiscal controls allowed these countries to overspend for years. The crisis emerged in late 2000s when debt became unsustainable and these countries could no longer borrow from markets. They required bailouts from the EU, IMF and ECB to pay debts and stabilize banks. Root causes included bloated public sectors and uncompetitive economies that struggled with austerity reforms tied to bailout loans.

Greece crisis explained

Greece crisis explainedGunjan Kumar Greece experienced a debt crisis due to reckless government borrowing and spending that increased its debt to 175% of GDP. The US subprime crisis further impacted Greece by restricting its ability to borrow from international markets. This led the EU, ECB, and IMF to provide bailout loans totaling over €200 billion and impose austerity measures to reduce Greece's debt, but the bailout money mainly paid off loans rather than helping the economy, and austerity hurt growth. Despite bailouts, Greece's debt problems remain an ongoing crisis for the EU.

euro currency

euro currency Mohammed ALkraidees The euro was adopted on January 1, 1999 by 12 of the 15 member states of the European Union as a single unified currency to replace individual national currencies like the French franc and German mark. On January 1, 2002, euro banknotes and coins were introduced and citizens exchanged their legacy currencies for euros, with the goals of creating a more stable economy, improving economic growth, and further integrating European financial markets and politics. While the euro has brought some economic benefits, issues around differing economic performance among countries and inability to independently adjust interest rates remain challenges.

Eurozone crisis

Eurozone crisis Institute of management Sciences, Peshawar The document discusses the Eurozone crisis, its impacts, and potential solutions. Specifically, it summarizes that the crisis was caused by weaker Eurozone economies like Greece overspending and taking on too much debt. This led to sovereign debt issues and required bailouts from stronger economies. The crisis impacted global economies by weakening the euro, reducing trade and exports, and slowing growth in places like the US, Japan, China, Russia, and Brazil. Solutions proposed include reducing spending, raising taxes, cutting wages and improving competitiveness in weaker economies.

Greece Economy

Greece Economy Meghavi Mehta The document summarizes Greece's economic crisis. It describes how Greece accumulated high government deficits and debt levels in the decades before the global financial crisis. This left Greece vulnerable when the crisis hit. Greece was bailed out in two packages totaling over $300 billion but had to accept austerity measures. The crisis impacted Greece through high unemployment, declining industrial production, banking troubles, and spillovers to other European and global economies. Reforms have focused on reducing government spending, opening markets, cutting wages and pensions.

Euro zone crisis

Euro zone crisisHasnain Baber The document summarizes the Eurozone crisis, including its causes and potential outcomes and solutions. It discusses how countries like Greece, Portugal and Ireland accumulated large fiscal and trade deficits within the Eurozone, unable to devalue their currencies. This led to a sovereign debt crisis threatening the entire Eurozone. Proposed solutions included bailouts with austerity measures, new stabilization funds, and moves toward greater fiscal and political integration among Eurozone members.

Recession Impact And Causes

Recession Impact And CausesJacob Nalleparampil This document discusses recessions, including defining a recession as a general slowdown in economic activity, and listing some potential causes such as financial crises or trade shocks. It then outlines several impacts of recessions such as falling GDP, investment, income and rising unemployment. The document also discusses different shapes recessions can take (V, U, L, W) and sectors most affected by recessions like stock markets, IT, banking, real estate and automobiles. It provides examples of past global recessions and their causes.

European debt crisis

European debt crisisSHASHIKANT KULKARNI The European debt crisis arose when countries that used the euro, such as Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Spain (PIIGS), accumulated high levels of sovereign debt and deficits and had difficulty refinancing or repaying their debt. These countries were previously able to borrow at lower interest rates when they adopted the euro. However, they then racked up large amounts of debt and deficits through overspending. If any of these countries default, it could spark a major financial crisis due to the interconnectedness of European banks and economies.

Financial Crises

Financial Crisestutor2u This study presentation looks at the causes and consequences of different types of financial crisis. It also focuses on the Hyman Minsky theory of financial instability in a capitalist economic system.

Understanding the Eurozone Crisis

Understanding the Eurozone CrisisEuropean Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM) The document summarizes the key stages of the Eurozone crisis from 2007 to 2011. It began with the seizure of the banking system in 2007 due to subprime mortgage debt. It discusses the stages including the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in 2008, the $5 trillion fiscal expansion committed by G20 leaders in 2009, the shift to concerns over government solvency in 2010, and the downgrade of US debt to AA+ in 2011. The crisis spread from the periphery to the core of the Eurozone, with bailouts of Ireland, Portugal, and multiple bailouts of Greece. Key factors fueling the crisis were slowing growth, rising debt levels, vulnerable banks, and lack of political leadership. The document also analyzes Europe's

2008 Global Financial Crisis

2008 Global Financial Crisis MJM Consulting Presentation for graduate economics course regarding 2008 financial crisis. (Accompanying paper as well).

The global financial crisis 2008

The global financial crisis 2008Al-azhar University - faculty of commerce The Global Financial Crisis was caused by expanded lending to subprime borrowers in the US housing market who struggled to repay their loans, spreading losses to financial institutions globally through interconnected credit markets. The crisis impacted developing countries through lower exports due to reduced demand from industrial nations and less foreign investment as risk appetite declined. Central banks addressed the crisis through liquidity injections and government rescue plans, while major banks consolidated to avoid bankruptcy.

Presentation - Global financial crisis 2008

Presentation - Global financial crisis 2008Mohit Rajput The document provides an overview of the global financial crisis of 2008. It describes how the crisis originated from the subprime mortgage crisis in the United States, where risky lending practices led to many homeowner defaults which subsequently impacted financial institutions globally. As asset prices fell and credit markets froze, there were banking failures across Europe and a global recession ensued, with rising unemployment and declines in GDP and stock prices around the world. India was also impacted via slowing economic growth, though its financial system had less direct exposure than Western nations.

European Monetary Union

European Monetary UnionPriyesh Neema The European Monetary Union (EMU) originated from the European Monetary System (EMS) established in 1979 to implement fixed exchange rates. The EMS has since developed into a more extensive economic and monetary union with coordinated policies among member countries. The EU and EMU were formed to create a unified European market, enhance political stability and economic growth, and eliminate risks from separate currencies. Currently 19 EU member countries use the euro currency as part of the EMU.

Global Financial Crisis 2008

Global Financial Crisis 2008krishnakantjalan The document provides an overview of the global financial crisis of 2008. It discusses several key points:

- The US housing market boom from 2002-2006 led to a housing price bubble that eventually burst, contributing to the crisis. As housing prices declined sharply from their 2006 peak, foreclosures and defaults increased substantially.

- Loose monetary policy by the US Federal Reserve from 2002-2004, keeping interest rates low, fueled risky lending and the housing bubble. When rates rose in 2005-2006, the default rate on adjustable mortgages skyrocketed.

- Highly leveraged investment banks collapsed in 2008 as default rates rose due to declining lending standards. Stock prices around the world plummeted nearly 40

Greece Crisis

Greece Crisisnadi143 Greece has been experiencing a debt crisis as its budget deficit and debt levels have risen significantly. This was caused by falling tax revenues, increased spending, misreporting of economic statistics, and the effects of the global financial crisis which hurt Greece's major industries of tourism and shipping. To address the crisis, Greece has implemented austerity measures like spending cuts and tax increases, and the EU/IMF have agreed to a bailout package of up to €110 billion in loans to help Greece pay its debts and restore market confidence. However, the crisis has highlighted issues with fiscal policy and oversight in the eurozone.

Euro Currency System

Euro Currency Systemshiva5717 The document provides information about the Euro currency system. It discusses:

1) The Euro became the official currency of 11 EU member states known as the Eurozone in 1999.

2) The Eurozone has become the world's second largest economy.

3) Member states had to meet certain convergence criteria to join the Eurozone such as maintaining low inflation and deficit levels.

4) The European Central Bank was established to implement monetary policy for the Eurozone.

Bolt

BoltAaryendr This document provides an overview of BOLT, the Bombay Stock Exchange's online trading system. It describes how BOLT automated stock trading in India by introducing a screen-based system that allows brokers to place orders electronically via computers and VSAT networks, replacing the previous open-outcry method. The key aspects covered include how brokers log in and enter buy/sell orders through their terminals, how the orders are transmitted to the main exchange computer, and how trades are matched and executed based on price and time priority. Important terms like circuit breakers, order books, and trade books are also defined.

Ca dhruv agrawalsebi icdr amendments

Ca dhruv agrawalsebi icdr amendmentsCa Agrawal The document discusses the SEBI (ICDR) Regulations 2009 and recent amendments relating to issue management. It provides an overview of the key aspects regulated by the ICDR regulations including specified securities, structure of regulations, issues not regulated, and eligibility requirements for public issues. Recent amendments are highlighted including changes to preferential issues, QIP, book building process and minimum listing requirements. Key considerations for different types of public issues such as pricing, allocation and lock-ins are also summarized.

More Related Content

What's hot (20)

Euro zone crisis

Euro zone crisisAjay Kumar the euro zone introduction and the reason for the crisis and its impact on the european countries and on the world

Greece crisis and its impact final ppt

Greece crisis and its impact final pptSumit Tamrakar Greece accumulated high levels of debt in the decade before the financial crisis when markets were liquid. This led to a sovereign debt crisis as the financial crisis deepened and liquidity dried up, making borrowing more difficult and expensive. The crisis impacted Greece through lower incomes, savings, capital flows and sector output like tourism and shipping that contribute significantly to GDP. The European Union, IMF and ECB implemented measures like bailout loans and austerity programs to reduce Greece's deficit while the ECB also engaged in bond purchases to increase confidence. Protests have occurred against austerity cuts while leaders debate solutions to the dilemma of whether to continue supporting Greece or risk default.

Euro zone crisis

Euro zone crisis Lovely Professional University The document discusses the Eurozone crisis that began in 2009. It started in Greece due to the country misreporting its economic statistics, which hid a large budget deficit. As the global financial crisis hit, it struggled with high debt and interest rates. Greece required a bailout package from the EU and IMF to avoid defaulting. The crisis spread to other southern European countries like Portugal, Italy, Ireland, and Spain, known as the PIIGS, who also had high debts and deficits. Austerity measures were implemented but caused economic hardships.

Eurozone debt crises

Eurozone debt crisesWordpandit The document discusses the Eurozone debt crisis, providing background on the origins of the euro currency and how debt levels grew unsustainably in Greece, Portugal, Italy and Spain (PIIGS countries). It explains that lack of fiscal controls allowed these countries to overspend for years. The crisis emerged in late 2000s when debt became unsustainable and these countries could no longer borrow from markets. They required bailouts from the EU, IMF and ECB to pay debts and stabilize banks. Root causes included bloated public sectors and uncompetitive economies that struggled with austerity reforms tied to bailout loans.

Greece crisis explained

Greece crisis explainedGunjan Kumar Greece experienced a debt crisis due to reckless government borrowing and spending that increased its debt to 175% of GDP. The US subprime crisis further impacted Greece by restricting its ability to borrow from international markets. This led the EU, ECB, and IMF to provide bailout loans totaling over €200 billion and impose austerity measures to reduce Greece's debt, but the bailout money mainly paid off loans rather than helping the economy, and austerity hurt growth. Despite bailouts, Greece's debt problems remain an ongoing crisis for the EU.

euro currency

euro currency Mohammed ALkraidees The euro was adopted on January 1, 1999 by 12 of the 15 member states of the European Union as a single unified currency to replace individual national currencies like the French franc and German mark. On January 1, 2002, euro banknotes and coins were introduced and citizens exchanged their legacy currencies for euros, with the goals of creating a more stable economy, improving economic growth, and further integrating European financial markets and politics. While the euro has brought some economic benefits, issues around differing economic performance among countries and inability to independently adjust interest rates remain challenges.

Eurozone crisis

Eurozone crisis Institute of management Sciences, Peshawar The document discusses the Eurozone crisis, its impacts, and potential solutions. Specifically, it summarizes that the crisis was caused by weaker Eurozone economies like Greece overspending and taking on too much debt. This led to sovereign debt issues and required bailouts from stronger economies. The crisis impacted global economies by weakening the euro, reducing trade and exports, and slowing growth in places like the US, Japan, China, Russia, and Brazil. Solutions proposed include reducing spending, raising taxes, cutting wages and improving competitiveness in weaker economies.

Greece Economy

Greece Economy Meghavi Mehta The document summarizes Greece's economic crisis. It describes how Greece accumulated high government deficits and debt levels in the decades before the global financial crisis. This left Greece vulnerable when the crisis hit. Greece was bailed out in two packages totaling over $300 billion but had to accept austerity measures. The crisis impacted Greece through high unemployment, declining industrial production, banking troubles, and spillovers to other European and global economies. Reforms have focused on reducing government spending, opening markets, cutting wages and pensions.

Euro zone crisis

Euro zone crisisHasnain Baber The document summarizes the Eurozone crisis, including its causes and potential outcomes and solutions. It discusses how countries like Greece, Portugal and Ireland accumulated large fiscal and trade deficits within the Eurozone, unable to devalue their currencies. This led to a sovereign debt crisis threatening the entire Eurozone. Proposed solutions included bailouts with austerity measures, new stabilization funds, and moves toward greater fiscal and political integration among Eurozone members.

Recession Impact And Causes

Recession Impact And CausesJacob Nalleparampil This document discusses recessions, including defining a recession as a general slowdown in economic activity, and listing some potential causes such as financial crises or trade shocks. It then outlines several impacts of recessions such as falling GDP, investment, income and rising unemployment. The document also discusses different shapes recessions can take (V, U, L, W) and sectors most affected by recessions like stock markets, IT, banking, real estate and automobiles. It provides examples of past global recessions and their causes.

European debt crisis

European debt crisisSHASHIKANT KULKARNI The European debt crisis arose when countries that used the euro, such as Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Spain (PIIGS), accumulated high levels of sovereign debt and deficits and had difficulty refinancing or repaying their debt. These countries were previously able to borrow at lower interest rates when they adopted the euro. However, they then racked up large amounts of debt and deficits through overspending. If any of these countries default, it could spark a major financial crisis due to the interconnectedness of European banks and economies.

Financial Crises

Financial Crisestutor2u This study presentation looks at the causes and consequences of different types of financial crisis. It also focuses on the Hyman Minsky theory of financial instability in a capitalist economic system.

Understanding the Eurozone Crisis

Understanding the Eurozone CrisisEuropean Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM) The document summarizes the key stages of the Eurozone crisis from 2007 to 2011. It began with the seizure of the banking system in 2007 due to subprime mortgage debt. It discusses the stages including the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in 2008, the $5 trillion fiscal expansion committed by G20 leaders in 2009, the shift to concerns over government solvency in 2010, and the downgrade of US debt to AA+ in 2011. The crisis spread from the periphery to the core of the Eurozone, with bailouts of Ireland, Portugal, and multiple bailouts of Greece. Key factors fueling the crisis were slowing growth, rising debt levels, vulnerable banks, and lack of political leadership. The document also analyzes Europe's

2008 Global Financial Crisis

2008 Global Financial Crisis MJM Consulting Presentation for graduate economics course regarding 2008 financial crisis. (Accompanying paper as well).

The global financial crisis 2008

The global financial crisis 2008Al-azhar University - faculty of commerce The Global Financial Crisis was caused by expanded lending to subprime borrowers in the US housing market who struggled to repay their loans, spreading losses to financial institutions globally through interconnected credit markets. The crisis impacted developing countries through lower exports due to reduced demand from industrial nations and less foreign investment as risk appetite declined. Central banks addressed the crisis through liquidity injections and government rescue plans, while major banks consolidated to avoid bankruptcy.

Presentation - Global financial crisis 2008

Presentation - Global financial crisis 2008Mohit Rajput The document provides an overview of the global financial crisis of 2008. It describes how the crisis originated from the subprime mortgage crisis in the United States, where risky lending practices led to many homeowner defaults which subsequently impacted financial institutions globally. As asset prices fell and credit markets froze, there were banking failures across Europe and a global recession ensued, with rising unemployment and declines in GDP and stock prices around the world. India was also impacted via slowing economic growth, though its financial system had less direct exposure than Western nations.

European Monetary Union

European Monetary UnionPriyesh Neema The European Monetary Union (EMU) originated from the European Monetary System (EMS) established in 1979 to implement fixed exchange rates. The EMS has since developed into a more extensive economic and monetary union with coordinated policies among member countries. The EU and EMU were formed to create a unified European market, enhance political stability and economic growth, and eliminate risks from separate currencies. Currently 19 EU member countries use the euro currency as part of the EMU.

Global Financial Crisis 2008

Global Financial Crisis 2008krishnakantjalan The document provides an overview of the global financial crisis of 2008. It discusses several key points:

- The US housing market boom from 2002-2006 led to a housing price bubble that eventually burst, contributing to the crisis. As housing prices declined sharply from their 2006 peak, foreclosures and defaults increased substantially.

- Loose monetary policy by the US Federal Reserve from 2002-2004, keeping interest rates low, fueled risky lending and the housing bubble. When rates rose in 2005-2006, the default rate on adjustable mortgages skyrocketed.

- Highly leveraged investment banks collapsed in 2008 as default rates rose due to declining lending standards. Stock prices around the world plummeted nearly 40

Greece Crisis

Greece Crisisnadi143 Greece has been experiencing a debt crisis as its budget deficit and debt levels have risen significantly. This was caused by falling tax revenues, increased spending, misreporting of economic statistics, and the effects of the global financial crisis which hurt Greece's major industries of tourism and shipping. To address the crisis, Greece has implemented austerity measures like spending cuts and tax increases, and the EU/IMF have agreed to a bailout package of up to €110 billion in loans to help Greece pay its debts and restore market confidence. However, the crisis has highlighted issues with fiscal policy and oversight in the eurozone.

Euro Currency System

Euro Currency Systemshiva5717 The document provides information about the Euro currency system. It discusses:

1) The Euro became the official currency of 11 EU member states known as the Eurozone in 1999.

2) The Eurozone has become the world's second largest economy.

3) Member states had to meet certain convergence criteria to join the Eurozone such as maintaining low inflation and deficit levels.

4) The European Central Bank was established to implement monetary policy for the Eurozone.

Viewers also liked (17)

Bolt

BoltAaryendr This document provides an overview of BOLT, the Bombay Stock Exchange's online trading system. It describes how BOLT automated stock trading in India by introducing a screen-based system that allows brokers to place orders electronically via computers and VSAT networks, replacing the previous open-outcry method. The key aspects covered include how brokers log in and enter buy/sell orders through their terminals, how the orders are transmitted to the main exchange computer, and how trades are matched and executed based on price and time priority. Important terms like circuit breakers, order books, and trade books are also defined.

Ca dhruv agrawalsebi icdr amendments

Ca dhruv agrawalsebi icdr amendmentsCa Agrawal The document discusses the SEBI (ICDR) Regulations 2009 and recent amendments relating to issue management. It provides an overview of the key aspects regulated by the ICDR regulations including specified securities, structure of regulations, issues not regulated, and eligibility requirements for public issues. Recent amendments are highlighted including changes to preferential issues, QIP, book building process and minimum listing requirements. Key considerations for different types of public issues such as pricing, allocation and lock-ins are also summarized.

Online trading

Online tradingHarsha Matta The document summarizes the achievements and rankings of a financial services company. It was the 5th largest in terms of offices and 6th largest in terms of trading terminals for 2007-2008. The company was nominated among the top 3 for "Best Financial Advisor Awards" in 2008 and 2009, and was awarded by BSE as a major volume driver from 2004-2008. It also ranked highly in terms of branch expansion, sub-brokers, and by UTI MF and CNBC TV 18 for best financial advisor in 2009.

Online trading ppt

Online trading ppt petkarshwt Online trading allows investors to place stock orders over the internet through a broker's trading platform. It offers advantages like paperless transactions, placing orders outside market hours, and easy access to trading records. However, internet connection issues could cause delays, and some brokers charge fees. The major stock exchange in India, the Bombay Stock Exchange, launched its online trading system BOLT in 1995 to increase capacity and market transparency. While online trading entered India relatively late due to regulations and infrastructure barriers, it has grown significantly and many brokers now offer online platforms.

Euro zone crisis ppt

Euro zone crisis pptSonali Kukreja This document outlines a study on the impact of the Euro-zone crisis on India's current account deficit. The study has three objectives: 1) examine the impact of the crisis on the current account deficit, 2) analyze the European zone as a major trading partner of India, and 3) analyze the correlation between the Indian rupee and Euro exchange rates to evaluate the crisis's effect. The document provides background on the Euro-zone, crisis, current account deficit, and reviews literature on factors influencing current account balances. It describes the study's methodology, expected outcomes to indicate how the crisis impacted Indian exports and currencies, and lists references.

Grey market

Grey marketMouad Gouffia Grey Market:

Role of Governments

Attraction of grey market to firms

Counteracting the grey market

Consumers within the grey market

Conclusion

References

Depositories

DepositoriesVikram Sankhala IIT, IIM, Ex IRS, FRM, Fin.Engr The document discusses India's depository system for electronic trading and settlement of securities. It describes how the earlier physical system was inefficient and led to problems. To address this, the Depositories Act of 1996 was passed to dematerialize securities and facilitate electronic transfers through depositories like NSDL and CDSL (National Securities Depository Limited and Central Depository Services Limited). The system aims to make transfers faster, more accurate and secure by maintaining electronic records of ownership rather than physical certificates.

Analysis of the Grey Market

Analysis of the Grey MarketRyan Wilson In this paper, I will illustrate how grey markets operate in domestic and international settings, apply these concepts towards the structure of several large and active grey markets currently in operation, demonstrate the effect of these unauthorized vendors upon manufacturers and retailers in operation within said markets, discuss how these white market operators have attempted to counteract these effects, and conclude by suggesting further actions these companies may implement to work with and around unauthorized resellers.

Mezzanine

MezzanineVantage Capital Advisors LLC Mezzanine finance is medium risk, medium return debt capital that is typically used to finance ownership successions, management buyouts, and growth capital. It has flexible structures like subordinated debt combined with equity warrants. Mezzanine lenders seek management teams with experience and clear business strategies, and look for proprietary advantages, measurable milestones, and alignment of interests between investors and management. Total returns for mezzanine investors typically target 20-25% through both interest payments and equity participation.

Indian depository receipts (IDR's) a glimpse

Indian depository receipts (IDR's) a glimpseMallikarjun Bali Indian Depository Receipts (IDRs) allow foreign companies to raise capital from the Indian market. IDRs represent shares of a non-Indian company and are issued by a domestic depository in India. The first IDR issuance was in 2010 by Standard Chartered Bank, which raised Rs. 2490 crore. While IDRs provide benefits like access to the Indian market, there are also challenges like tax treatment and lack of fungibility between IDRs and underlying shares. The legal framework for IDRs needs further improvements to realize their full potential.

A project report on online trading

A project report on online tradingKumar Gaurav The document discusses an organizational profile for KOMOLINE, an Indian company established in 1990 that specializes in precision sensors, data loggers, transmitters, and software for weather monitoring and satellite communications equipment. KOMOLINE has in-house design, development, testing, and manufacturing capabilities and provides automated weather stations, sensor networks, tide gauges, and satellite communication modems for applications like weather forecasting and disaster management.

Insider trading

Insider tradingRizwan Rakhda Insider trading involves trading in a company's securities using material, non-public information. It can include directors, employees or other connected persons trading based on confidential corporate info. The US was first to tackle insider trading through the Securities Exchange Act of 1984. In India, SEBI regulations from 1992 define "insiders" as connected persons who may have access to unpublished price sensitive info. The regulations prohibit insiders from trading using such info and require listed companies to implement codes of conduct regarding disclosure practices. Violations can result in heavy financial penalties or criminal prosecution.

An analysis of demat account and online trading

An analysis of demat account and online tradingProjects Kart This document provides an overview of online share trading and dematerialization in India. It includes an executive summary that outlines the key benefits of online trading and dematerialization, such as faster trading and reduced costs compared to physical brokers. It also lists the objectives and scope of the project report. The industrial overview provides background on the history of online trading. The company profile section gives details on Indiabulls Financial Services, including its history, profile, products/services and growth. Overall, the document aims to analyze awareness of online trading and dematerialization among investors in India.

Ppt on depository system in india

Ppt on depository system in indiaKavita Sharma The document discusses the depository system in India. It explains that a depository holds securities electronically, avoiding risks of paper certificates. It outlines the key entities in the depository system - depositories like NSDL and CDSL, depository participants that interact with investors, stock exchanges, and clearing corporations. The document also describes various services provided by depositories like dematerialization and rematerialization of securities, account transfers, and settlement of trades.

Insider trading

Insider tradingFortune Institute of intrenational Business The document summarizes an insider trading case involving four parties - UTI, HLL, BBLIL, and SEBI. HLL planned to merge with BBLIL, which it informed exchanges of on April 19, 1996. Before the merger, HLL bought shares of BBLIL from UTI. SEBI accused HLL of insider trading, but the finance ministry later absolved HLL of charges. The key issues were whether HLL was an insider, if it had non-public information, and if it gained unfair advantage. While SEBI argued HLL was an insider, the information was non-public, and it gained, HLL counters the information was public and it did not unfairly benefit

Circuit breaker

Circuit breakerBiswajit Pratihari The document discusses different types of circuit breakers, including air blast, vacuum, oil, and SF6 circuit breakers. It explains that a circuit breaker can make, carry, and break currents under normal and abnormal circuit conditions. The operating mechanism involves using stored energy to move a moving contact to open or close the circuit. When contacts separate during a fault, an arc is formed that must be quickly quenched for circuit interruption. Each breaker type uses a different medium, such as air, vacuum, oil or SF6 gas, to rapidly cool and extinguish the arc. Modern systems commonly use vacuum or SF6 breakers for their fast, reliable performance.

The grey market

The grey marketgcd, dublin, ireland This document discusses grey market goods and counterfeit goods. It defines grey market goods as genuine trademarked goods that are imported into a country and sold in competition with the exclusive authorized importer. Counterfeit goods are identical but not genuine copies of trademarked goods. The document notes that grey market goods are mainly found in pharmaceuticals, electronics, automobiles, tobacco, alcohol, and fashion goods. While grey markets can cut costs, they can breach copyright and tariff laws by selling goods through unauthorized channels.

Similar to European sovereign debt crisis (20)

Europian debt crisis

Europian debt crisisNitesh Bhele The document discusses the 2010 European debt crisis, its causes, and its impact on several European countries including Portugal, France, and Germany. It also outlines some of the policy reactions from European leaders and institutions to address the crisis, such as establishing the European Financial Stability Facility and European Financial Stabilization Mechanism to provide loans to countries in financial trouble.

Eurozone crisis

Eurozone crisisPriyamvada Jha The document discusses the Eurozone crisis, its causes, and proposed solutions. It began with low interest rates fueling housing bubbles in countries like Greece, Ireland, Spain and Portugal. When the global financial crisis hit in 2008, it exposed flaws in the eurozone design like lack of fiscal coordination and inability of countries to use monetary policy. This led countries like Greece to face debt crises. The EU implemented emergency measures like bailout funds (EFSF, EFSM) and long-term reforms like the European Stability Mechanism and European Fiscal Compact to address fiscal profligacy. Proposed long-term solutions include a European fiscal union, eurobonds, and debt restructuring to reduce unsustainable debt levels

euro crisis

euro crisisSandeep Vishwakarma The document discusses the European Union, Eurozone, and the European sovereign debt crisis. It provides details on the countries that make up the Eurozone and EU. It then summarizes the sovereign debt crisis that began in Greece in 2009 and spread to other European countries like Portugal, Ireland, Italy, and Spain. It explains some of the key events and impacts of the crisis, as well as measures taken by the EU and European Central Bank to address the financial crisis.

euro crisis

euro crisisSandeep Vishwakarma The document discusses the European Union, Eurozone, and the European sovereign debt crisis. It provides details on the countries that make up the Eurozone and EU. It then summarizes the sovereign debt crisis that began in Greece in 2009 and spread to other European countries like Portugal, Ireland, Italy, and Spain. It explains some of the key events and impacts of the crisis, as well as measures taken by the EU and European Central Bank to address the financial crisis.

European Union and Euro Zone

European Union and Euro ZoneSaurabh Maloo The European Union was formed after World War 2 to promote peace and economic prosperity in Europe. It started with treaties promoting trade and economic cooperation and has expanded over time to include policies for a common currency, open borders, and more political integration among member states. However, the EU faces ongoing challenges including disagreements over issues like immigration, the debt crisis in some member countries, and the UK's decision to leave the EU (Brexit). The path forward remains uncertain but could involve either deeper integration among core members or a looser, more intergovernmental structure.

Euro Crisis - R Bays

Euro Crisis - R BaysRichard Bays JD, MBA, RN, CPHQ The document provides information about the history and development of the Euro currency. It describes how the Euro was introduced in 1999 among 11 European countries and expanded to 17 member states. Key events that led to the adoption of the Euro include the 1992 Maastricht Treaty which set the criteria for countries to join the Eurozone. The document also discusses the economic and monetary benefits of having a single currency, as well as the institutions like the European Central Bank that manage the Euro.

European Sovereign Debt Crisis

European Sovereign Debt Crisis Vishwarath Reddy This document summarizes the key events and factors that led to the European sovereign debt crisis. It explains that the creation of the euro enabled countries like Greece and Ireland to borrow at lower interest rates, fueling private sector borrowing and housing bubbles. When the global financial crisis hit in 2008, it exposed weaknesses in heavily indebted countries and dried up capital flows. This caused banking crises, rising bond yields, and eventual bailouts for Greece, Ireland, Portugal and others as investors grew concerned about their ability to repay debts. Reforms were implemented around fiscal rules and banking regulation, but the crisis highlighted the need for greater fiscal integration or risk of further crises.

Topic 5

Topic 5School of Economics, North-West University The document discusses the eurozone crisis, its causes, consequences, and policy options. It provides a detailed timeline of the crisis from 2009-2012, highlighting Greece's mounting debt issues and subsequent bailouts. The crisis stemmed from increases in government and private debt during strong growth. Austerity measures have deepened recessions while bailouts risk fatigue. Options include Greece exiting the euro, more support/bailouts, or greater fiscal coordination in Europe.

Euro crisis

Euro crisisSHEKHAR KUSHWAHA The document discusses the Euro zone crisis that began in 2009. It provides background on the Euro zone, then explains how the global financial crisis that began in 2007 led to a recession in the Euro zone. Greece was most severely impacted, with a large budget deficit, high debt levels exceeding 100% of GDP, and reliance on external aid. Other PIIGS countries (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Spain) also faced high debt levels and budget issues. The crisis spread uncertainty and economic problems to other European and neighboring countries. Proposed solutions involved international bailouts, government austerity measures, spending cuts, tax increases, and structural economic reforms.

Eurozone Sovereign debt crisis

Eurozone Sovereign debt crisisAshutoshSingh979 The document provides historical context on the evolution of the European Union and Eurozone, including key treaties and agreements that advanced economic and monetary integration among EU member states over time. It then discusses the sovereign debt crisis that emerged in Europe in 2010, with several Eurozone countries like Greece, Ireland, and Portugal facing insolvency and requiring bailouts after accumulating high levels of debt. The causes of Ireland's economic crisis are explained in more detail, including the bursting of a real estate bubble and the government guaranteeing bank losses that swelled the national deficit.

Pensions and the European Debt Crisis

Pensions and the European Debt CrisisAegon The document discusses the European debt crisis and its impact on pensions. It identifies four key points: 1) the debt crisis poses risks to both funded and unfunded pension systems, 2) implicit pension liabilities should be considered, 3) European politicians need action to restore confidence and contain the debt, and 4) structural reforms are needed and budget deficits must be reduced. It then provides context on the history and causes of the debt crisis, and analyzes four scenarios for resolving it based on regaining market confidence in the short-term and implementing structural reforms in the long-term.

Greek Crisis

Greek CrisisJason Lee The document summarizes the Greek sovereign debt crisis, providing background on the European Union and Eurozone, the timeline of events leading up to the crisis, causative factors, and current actions being taken. It describes Greece joining the Eurozone in 2001 and later admitting it had falsified deficit numbers. The global financial crisis exacerbated Greece's high deficit, debt, and structural economic issues. A series of austerity packages and bailouts from the EU and IMF have aimed to reduce Greece's deficit since 2010, though the deep recession has made targets difficult to achieve. Current actions include further austerity measures and privatization in exchange for release of additional bailout funds to avoid default.

Euro debt crisis div a

Euro debt crisis div aMohil Poojara The document summarizes the Eurozone debt crisis. It discusses how rising government debt levels, trade imbalances, and monetary policy inflexibility contributed to the crisis. It then examines the specific issues facing Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Potential solutions discussed include the European Financial Stability Facility, European Financial Stabilization Mechanism, Eurobonds, and ECB interventions. Four possible future scenarios are outlined: a successful resolution, an orderly Greek default, a disorderly default triggering a banking crisis, or a full break up of the Eurozone.

Euro crisis

Euro crisisRahul Nishad The Eurozone debt crisis began in 2009 when it was realized that Greece could default on its debt, escalating over three years to include potential defaults by Portugal, Italy, Ireland and Spain. The crisis occurred due to countries violating debt-to-GDP ratios without penalties and overspending during economic recession. While emergency loans from stronger economies and institutions attempted to remedy the crisis, austerity measures aimed at reducing spending further slowed economic growth and tax revenues, exacerbating the issues. The crisis significantly impacted the global economy and financial markets due to the large size of the EU and Eurozone.

USA Crisis & Euro Crisis

USA Crisis & Euro CrisisShubham Bhatia The document discusses the impact of the USA and European debt crises on the global economy. It provides details on:

1) How the USA debt crisis began in 2001 with interest rate cuts and increased lending, leading to a housing bubble and financial crisis in 2008. This crisis spread globally and contributed to the European debt crisis.

2) How the European debt crisis involved several countries like Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Cyprus taking on too much debt and eventually needing bailouts. The crisis threatened the stability of the Eurozone.

3) How both crises led to global economic impacts like recession, falling stock markets, reduced trade and liquidity issues. The European crisis also influenced events like the UK

Quick View On The Greek Crisis

Quick View On The Greek CrisisMohamed Atef The document discusses the Greek financial crisis that began in 2010. Political problems like unrestrained government spending and failure to implement reforms, as well as economic issues such as a high budget deficit and national debt, led to the crisis. This negatively impacted Europe's credibility in financial markets. Proposed solutions included austerity measures by the Greek government to reduce the deficit through tax increases and spending cuts, which led to public protests. The eurozone and IMF also implemented two rescue packages to help Greece.

Jatin parmar euro zone crisis

Jatin parmar euro zone crisispiyoosh_09 The document discusses the Euro Zone crisis that began in 2009. Key points include:

- The crisis started in Greece and spread to other southern European countries (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Spain) due to high government debts and budget deficits.

- The crisis threatened the stability of the shared Euro currency. Resolutions included a 750 billion euro rescue package from European governments and the IMF.

- Affected countries implemented austerity measures like spending cuts and tax increases to reduce their deficits but at the cost of economic hardship. The long term solutions require integrating economic policies or allowing debts to be restructured.

ECB vs Fed: Solutions to banking crisi

ECB vs Fed: Solutions to banking crisiPhilip Corsano Banking crisis in EU Zone, is the crisis of EU. How to recapitalize banks without pushing bad debts onto Governments of Spain, Ireland, Italy...

Future of Euro Zone

Future of Euro ZoneRiddhi Solanki Group 6 presents on the future of the Euro zone. The Euro zone crisis began in 2009 in Greece due to high deficit and debt levels. Greece had a debt-to-GDP ratio of 113% and budget deficit of 12.9% of GDP. The crisis spread to other PIIGS countries like Portugal, Italy, Ireland and Spain. If Greece exits the Euro zone, it could cause economic and financial instability across Europe as people withdraw money from banks. The future of the Euro zone depends on further economic integration of policies or the potential collapse of weaker economies and banks losing hundreds of billions.

Euro zone crisis

Euro zone crisis Barkha Agarwal The Euro zone crisis began in 2009 when Greece's huge government debt levels were revealed, exceeding 113% of GDP. A series of bailouts were issued over subsequent years for Greece, Ireland, and Portugal as their debt levels became unsustainable and they struggled to repay loans. The crisis threatened the stability of the entire Euro zone and raised concerns it could spread to larger economies like Italy and Spain. Underlying causes included rising private and public debt globally as well as structural issues within the Euro zone without a full fiscal union to support the shared currency.

Recently uploaded (20)

Certainties that are changing.Feb25.AM.ENG.docx.pdf

Certainties that are changing.Feb25.AM.ENG.docx.pdfAndrea Mennillo “Nothing’s sure about tomorrow,” wrote Lorenzo de’ Medici more than five centuries ago, in an attempt to stop time and harness the energy of youth. Energy that seems more valuable than ever today. Not necessarily – or not only – due to the demographic shift, but because of the demands of enterprises, the economy and our own lives.

Biography and Professional Career of Drew Doscher

Biography and Professional Career of Drew DoscherDrew Doscher Drew Doscher has demonstrated financial acumen and upheld a substantial ethical standard, earning him the reputation of “honest guy in a dishonest business.” His transparent dealings and leadership during crises, such as the Barclays-Lehman merger, have only bolstered his standing in the finance community.

Monthly Economic Monitoring of Ukraine No. 241

Monthly Economic Monitoring of Ukraine No. 241Інститут економічних досліджень та політичних консультацій Summary

• The IER estimates real GDP growth at 3.5% in 2024. According to the current IER forecast, real

GDP will grow by 2.9% in 2025 and 3.2% in 2026.

• According to the IER, real GDP grew by 2.0% yoy in January (by 1.6% yoy in December).

• In early February, power outages began for industry and businesses during peak hours due to

russian attacks on energy infrastructure.

• Naftogaz began importing gas due to a cold snap, the suspension of russian gas transit to the

EU, and shelling of gas infrastructure.

• In January, Ukraine exported 6.6 m t of goods by sea and 14 m t by rail.

• There was a seasonal decline in imports and a slowdown in exports in January.

• In January, the government received EUR 3 bn from the EU under the ERA (Extraordinary

Revenue Acceleration) mechanism, which should be repaid from profits from russian assets

frozen in the EU.

• In January, consumer inflation in annual terms further accelerated and reached 12.9% yoy.

• The NBU raised the rate from 13.5% to 14.5% per annum due to further acceleration in inflation

and deterioration in inflation expectations.

• The NBU's international reserves amounted to USD 43 bn at the end of January, which is slightly

less than USD 43.8 bn at the beginning of the year.

_Offshore Banking and Compliance Requirements.pptx

_Offshore Banking and Compliance Requirements.pptxLDM Global Offshore banking allows individuals and businesses to hold accounts in foreign jurisdictions, offering benefits like privacy, asset protection, and potential tax advantages. However, strict compliance regulations govern these banks to prevent financial crimes. Key requirements include Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) laws, along with international regulations like FATCA (for U.S. taxpayers) and CRS (for global tax transparency).

Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) in India: Strengthening Agricultural Val...

Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) in India: Strengthening Agricultural Val...Sunita C This presentation explores the role of FPOs in empowering small and marginal farmers, improving market access, enhancing bargaining power, promoting sustainable agriculture, and addressing challenges in agricultural trade, financing, and policy support.

RECOVER YOUR SCAMMED FUNDS AND CRYPTOCURRENCY HIRE iFORCE HACKER RECOVERY

RECOVER YOUR SCAMMED FUNDS AND CRYPTOCURRENCY HIRE iFORCE HACKER RECOVERYlonniecort7 iFORCE HACKER RECOVERY consists of professional hackers who specialize in securing compromised devices, accounts, and websites, as well as recovering stolen bitcoin and funds lost to scams. They operate efficiently and securely, ensuring a swift resolution without alerting external parties. From the very beginning, they have successfully delivered on their promises while maintaining complete discretion. Few organizations take the extra step to investigate network security risks, provide critical information, or handle sensitive matters with such professionalism. The iFORCE HACKER RECOVERY team helped me retrieve $364,000 that had been stolen from my corporate bitcoin wallet. I am incredibly grateful for their assistance and for providing me with additional insights into the unidentified individuals behind the theft.

Webpage; www. iforcehackersrecovery. com

Email; contact@iforcehackersrecovery. com

whatsapp; +1 240. 803. 3. 706

Yanis Varoufakis - Technofeudalism_ What Killed Capitalism - libgen.li.pdf

Yanis Varoufakis - Technofeudalism_ What Killed Capitalism - libgen.li.pdfMatiasMendoza46 Libro de Varoufakis sobre la evolución del sistema capitalista.

Veritas Financial statement presentation 2024

Veritas Financial statement presentation 2024Veritas Eläkevakuutus - Veritas Pensionsförsäkring The return on Veritas' fixed-income investments was 6.7 per cent during the year, equity investments 12.7 per cent, real estate investments -0.7 per cent and other investments 7.9 per cent.

Agricultural Credit and Financial Inclusion: Role of Kissan Credit Card

Agricultural Credit and Financial Inclusion: Role of Kissan Credit CardSunita C This PowerPoint presentation provides an in-depth analysis of the Kisan Credit Card (KCC) Scheme, a government initiative aimed at providing timely and low-cost credit to farmers. It covers the scheme's objectives, eligibility criteria, loan limits, interest rates, and repayment structure. Additionally, the presentation explores the role of financial institutions, digital advancements in KCC, its impact on rural credit accessibility, and challenges in implementation. It also highlights recent policy reforms and government efforts to expand KCC coverage to benefit small and marginal farmers, livestock owners, and fishers.

Slides: Eco Economic Epochs for The World Game .pdf

Slides: Eco Economic Epochs for The World Game .pdfSteven McGee Paper: The Great Redesign of The World Game (s): Equitable, Ethical, Eco Economic Epochs for programmable money, economy, big data, artificial intelligence , quantum computing.. federation, federated liquidity e.g., the "JP Morgan - Knickerbocker protocol" / global unified value unit

What would be the protection gap in Motor Insurance for future

What would be the protection gap in Motor Insurance for futureBalkir Demirkan Motor insurance, protection gap, autonomus vehicles, liability, balkir demirkan, gsr, gsr2, vehicles type approval

Gender board diversity and firm performance

Gender board diversity and firm performanceGRAPE We study the effects of gender board diversity on firm performance. We use novel and rich firm-level data covering over seven million private and public firms spanning the years 1995-2020 in Europe. We augment a standard TFP estimation with a shift-share instrument for gender board diversity. We find that increasing the share of women in the boardroom is conducive to better economic performance. The results prove robust in a variety of subsamples, and to a variety of sensitivity analyses. This outcome is driven primarily by firms from the service sector. The positive impact was stronger during the more recent years of our sample that is a period with relatively more board diversity.

INDUSTRIAL ESTATES IN TAMIL NADU by Dr. S. Malini

INDUSTRIAL ESTATES IN TAMIL NADU by Dr. S. MaliniMaliniHariraj Tamil Nadu is a leading industrial hub in India, attracting foreign investment due to its strong infrastructure, logistics, and diverse manufacturing sector, including automobiles, aerospace, pharmaceuticals, textiles, electronics, and chemicals. The state has the second-highest GDP in India and houses the largest number of factory units (37,220), contributing 20% of India’s electronics production. It has a high concentration of Special Economic Zones (SEZs), accounting for one-third of the state’s exports, with key industrial estates like **Ambattur, Sriperumbudur, and Oragadam**. The **Tamil Nadu Small Industries Development Corporation (TANSIDCO)**, established in 1970, supports **MSMEs** by maintaining **41 Government Industrial Estates and 87 TANSIDCO Industrial Estates**, offering developed plots (5 cents to 1 acre) and various support services such as cluster development, technical guidance, and raw material assistance. Notable industrial estates include **Ambattur (one of Asia’s largest MSME hubs), Guindy (India’s first industrial estate), Sriperumbudur (home to Hyundai, Foxconn, and Samsung), Oragadam (major automotive hub), Irungattukottai (Renault-Nissan, BMW), and Vallam Vadagal (aerospace and defense industries).** These estates provide world-class infrastructure, including **reliable power, developed plots, common facility centers, strong connectivity (highways, ports, airports), 24/7 security, water supply, stormwater drains, sewage systems, green belts, and parks**, fostering a robust environment for industrial growth.

Monthly Economic Monitoring of Ukraine No. 241

Monthly Economic Monitoring of Ukraine No. 241Інститут економічних досліджень та політичних консультацій

European sovereign debt crisis

- 2. INTRODUCTION • From late 2009, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed among investors as a result of the rising private and government debt levels around the world together with a wave of downgrading of government debt in some European states. • Three countries significantly affected, Greece, Ireland and Portugal, collectively accounted for 6% of the eurozone's gross domestic product (GDP).

- 3. •In June 2012, also Spain became a matter of concern, when rising interest rates began to affect its ability to access capital markets, leading to a bailout of its banks and other measures. •The crisis has had a major impact on EU politics, leading to power shifts in several European countries, most notably in Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and France.

- 5. CAUSES Rising household and government debt levels Trade imbalances Structural problem of Eurozone system Monetary policy inflexibility Loss of confidence

- 6. Rising household and government debt levels • A number of economists have dismissed the popular belief that the debt crisis was caused by excessive social welfare spending. • According to their analysis, increased debt levels were mostly due to the large bailout packages provided to the financial sector during the late-2000s financial crisis.

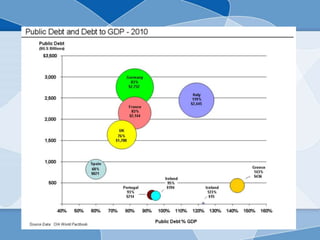

- 7. • The average fiscal deficit in the euro area in 2007 was only 0.6% before it grew to 7% during the financial crisis. • The International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported in April 2012 that in advanced economies,the ratio of household debt to income rose by an average of 39 percentage points, to 138 percent in Denmark, Iceland, Ireland, the Netherlands.

- 8. • In the same period, the average government debt rose from 66% to 84% of GDP. • By the end of 2011, real house prices had fallen from their peak by about 41% in Ireland, 29% in Iceland, 23% in Spain and the United States, and 21% in Denmark.

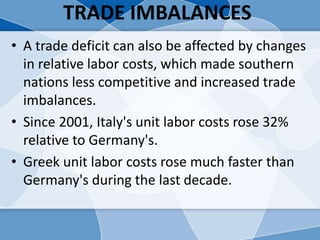

- 10. TRADE IMBALANCES • A trade deficit can also be affected by changes in relative labor costs, which made southern nations less competitive and increased trade imbalances. • Since 2001, Italy's unit labor costs rose 32% relative to Germany's. • Greek unit labor costs rose much faster than Germany's during the last decade.

- 12. STRUCTURAL PROBLEM OF EUROZONE SYSTEM • There is a structural contradiction within the euro system, namely that there is a monetary union without a fiscal union (e.g., common taxation, pension, and treasury functions). • In the Eurozone system, the countries are required to follow a similar fiscal path, but they do not have common treasury to enforce it.

- 13. • That is, countries with the same monetary system have freedom in fiscal policies in taxation and expenditure. • Eurozone, having 17 nations as its members, require unanimous agreement for a decision making process.

- 14. • This would lead to failure in complete prevention of contagion of other areas, as it would be hard for the Euro zone to respond quickly to the problem. • That is, countries with the same monetary system have freedom in fiscal policies in taxation and expenditure

- 15. MONETARY POLICY INFLEXIBILITY • Eurozone establishes a single monetary policy, individual member states can no longer act independently, preventing them from printing money in order to pay creditors and ease their risk of default. • By "printing money", a country's currency is devalued relative to its (eurozone) trading partners, making its exports cheaper,increased GDP and higher tax revenues in nominal terms.

- 16. LOSS OF CONFIDENCE • The loss of confidence is marked by rising sovereign CDS (credit-default swaps) prices, indicating market expectations about countries creditworthiness. • Since countries that use the euro as their currency have fewer monetary policy choices certain solutions require multi-national cooperation.

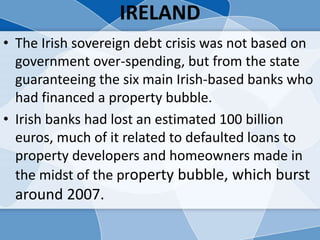

- 18. IRELAND • The Irish sovereign debt crisis was not based on government over-spending, but from the state guaranteeing the six main Irish-based banks who had financed a property bubble. • Irish banks had lost an estimated 100 billion euros, much of it related to defaulted loans to property developers and homeowners made in the midst of the property bubble, which burst around 2007.

- 19. • Unemployment rose from 4% in 2006 to 14% by 2010, while the national budget went from a surplus in 2007 to a deficit of 32% GDP in 2010, the highest in the history of the eurozone, despite austerity measures.

- 21. PORTUGAL • Portugal requested a €78 billion IMF-EU bailout package in a bid to stabilise its public finances. • These measures were put in place as a direct result of decades-long governmental overspending and an over bureaucratised civil service. • On 16 May 2011, the eurozone leaders officially approved a €78 billion bailout package for Portugal, which became the third eurozone country, after Ireland and Greece, to receive emergency funds.

- 22. • The average interest rate on the bailout loan is expected to be 5.1 percent. As part of the deal, the country agreed to cut its budget deficit from 9.8 percent of GDP in 2010 to 5.9 percent in 2011, 4.5 percent in 2012.

- 23. Proposed long-term solution European fiscal union Eurobonds European Monetary Fund Drastic debt write-off financed by wealth tax Debt defaults and national exits from the Eurozone

- 24. EUROPEAN FISCAL UNION • Increased European integration giving a central body increased control over the budgets of member states. • Control, including requirements that taxes be raised or budgets cut, would be exercised only when fiscal imbalances developed.

- 25. EUROBONDS • A growing number of investors and economists say Eurobonds would be the best way of solving a debt crisis though their introduction matched by tight financial and budgetary coordination may well require changes in EU treaties. • On 21 November 2011, the European Commission suggested that Eurobonds issued jointly by the 17 euro nations would be an effective way to tackle the financial crisis.

- 26. EUROPEAN MONETARY FUND • On 20 october 2011, the austrian institute of economic research published an article that suggests transforming the efsf into a european monetary fund (emf), which could provide governments with fixed interest rate eurobonds at a rate slightly below medium-term economic growth • These bonds would not be tradable but could be held by investors with the EMF and liquidated at any time.

- 27. DRASTIC DEBT WRITE-OFF FINANCED BY WEALTH TAX • To reach sustainable levels the eurozone must reduce its overall debt level by €6.1 trillion. • According to BCG this could be financed by a one-time wealth tax of between 11 and 30 percent for most countries, apart from the crisis countries (particularly Ireland) where a write-off would have to be substantially higher.

- 29. DEBT DEFAULTS AND NATIONAL EXITS FROM THE EUROZONE • In mid May 2012 the financial crisis in Greece and the impossibility of forming a new government after elections led to strong speculation that Greece would have to leave the Eurozone shortly. • This phenomenon had already become known as "Grexit" and started to govern international market behaviour.