Literature Review - How to write effectively.pptx

- 3. What is a Literature review?

- 4. What is a Literature review The aim of a literature review is to show "that the writer has studied existing work in the field with insight”. It will enable you to: 1. Define and limit the problem you are working on 2. Place your study in a historical perspective 3. Avoid unnecessary duplication 4. Evaluate promising research methods 5. Relate your findings to previous knowledge and suggest further research.

- 5. An effective review analyses and synthesizes material, and it should meet the following requirements: 1. Compare and contrast different authors' views on an issue 2. Group authors who draw similar conclusions 3. Criticise aspects of methodology 4. Note areas in which authors are in disagreement 5. Highlight exemplary studies 6. Identify patterns or trends in the literature 7. Highlight gaps and omissions in previous research or questions left unanswered 8. Show how your study relates to previous studies and to the literature in general 9. Conclude by summarising what the literature says

- 6. Basic Guidelines for a Literature Review • Establish your research questions and organise your literature into logical categories around topics. • Begin the literature review with an introduction to the topic. What is its significance and importance? • Critically analyse the literature relevant to the research question stating the content of the literature, implications of this knowledge, any gaps or deficiencies and inconsistencies or conflicting viewpoints. • Ensure you make your own interpretations and that you have written a critical and evaluative review.

- 7. Basic Guidelines for a Literature Review • The conclusion draws together important points and shows how the information answers the question. • Establish if more research is needed, especially if there are inconsistencies or conflicting points of view. • Avoid plagiarism - acknowledge sources of ideas and quotations to add authority and credibility to the work.

- 8. Searching the Literature - Locating your Resources • The first step towards a good literature review is conducting a comprehensive literature search. • An effective literature search will: – Reduce the time spent looking for information. – Maximise the quality and appropriateness of results. – Help clarify the scope of your research topic. – Assist in identifying experts and important published works in your field.

- 9. When conducting your literature search, remember to: • Use a variety of resources to cover a range of media - a literature review should include a range of literature, such as books, journal articles, or Internet sites. Theses, conference papers and government or industry reports can also be included. Do not rely solely on electronic full-text material which is more easily available. • Be aware of the importance of evaluating information. Is a journal refereed/peer reviewed? Is a source authoritative? • Use reference sources such as dictionaries to assist in defining terminology. Encyclopedias may be useful in introducing topics and listing key references.

- 10. When conducting your literature search, remember to: • Conduct initial searches by subject. You can also do author searches and search using citation indexes (i.e. Scopus). • Some databases allow you to save searches and set up email alerting, ensuring that your literature search is up to date. • Ensure you take care with recording your references. Keep systematic and accurate records. Software such as EndNote can assist. • Aim to find the most important relevant material early. Read as you go and make critical and evaluative notes as you read.

- 11. Search Strategies • The literature review relates to your research questions so think of the key concepts surrounding them. • Establish terminology and key words. A thesaurus can assist you. • Construct a search strategy. Use Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT). • The absence of research in the literature may help confirm that this is an area which needs further research; broaden your search by looking for literature in related fields. • Determine the scope of your literature search. The breadth of reading may depend on whether it is a new research area, where reading will need to be more extensive, or a well-researched area where reading may be more focused.

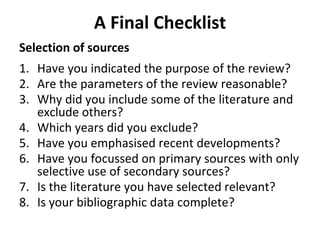

- 12. A Final Checklist Selection of sources 1. Have you indicated the purpose of the review? 2. Are the parameters of the review reasonable? 3. Why did you include some of the literature and exclude others? 4. Which years did you exclude? 5. Have you emphasised recent developments? 6. Have you focussed on primary sources with only selective use of secondary sources? 7. Is the literature you have selected relevant? 8. Is your bibliographic data complete?

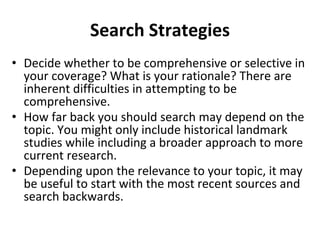

- 13. Search Strategies • Decide whether to be comprehensive or selective in your coverage? What is your rationale? There are inherent difficulties in attempting to be comprehensive. • How far back you should search may depend on the topic. You might only include historical landmark studies while including a broader approach to more current research. • Depending upon the relevance to your topic, it may be useful to start with the most recent sources and search backwards.

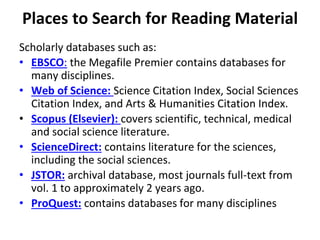

- 14. Places to Search for Reading Material Scholarly databases such as: • EBSCO: the Megafile Premier contains databases for many disciplines. • Web of Science: Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, and Arts & Humanities Citation Index. • Scopus (Elsevier): covers scientific, technical, medical and social science literature. • ScienceDirect: contains literature for the sciences, including the social sciences. • JSTOR: archival database, most journals full-text from vol. 1 to approximately 2 years ago. • ProQuest: contains databases for many disciplines

- 15. A Final Checklist Critical evaluation of the literature 1. Have you organised your material according to issues? 2. Is there a logic to the way you organised the material? 3. Does the amount of detail included on an issue relate to its importance? 4. Have you been sufficiently critical of design and methodological issues? 5. Have you indicated when results were conflicting or inconclusive and discussed possible reasons? 6. Have you indicated the relevance of each reference to your research?

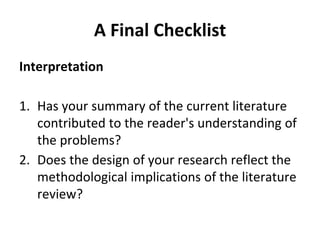

- 16. A Final Checklist Interpretation 1. Has your summary of the current literature contributed to the reader's understanding of the problems? 2. Does the design of your research reflect the methodological implications of the literature review?

- 17. A Final Checklist Note: • The literature review will be judged in the context of your completed research. • The review needs to further the reader's understanding of the problem and whether it provides a rationale for your research.

- 18. Further Reading • Biggam, J. (2011). Succeeding with your master's dissertation: A step-by-step handbook. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill International Ltd. • Burton, S. and Steane, P. (2004). Surviving your thesis. New York : Routledge. • Caulley, D. N. (1992). Writing a Critical Review of the Literature. La Trobe University: Bundoora. • Fink, A. (2009). Conducting research literature reviews : From the Internet to paper. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. • Harzing, A. (2010). The publish or perish book: Your guide to effective and responsible citation analysis. Melbourne : Tarma Software Research Pty Ltd. • Haywood, P. and Wragg, E. D. (1982). Evaluating the Literature. Rediguide 2, University of Nottingham School of Education. • Huff, A. S. (2009). Designing research for publication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. • Jesson, J. K. (2011). Doing your literature review: Traditional and systematic techniques. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. • Lyons, P. (2010). The dissertation: from beginning to end. New York : Oxford University Press. • Mertens, D. (2010). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. • Murray, R. (2011). How to write a thesis. Maidenhead : McGraw-Hill International Ltd. • Oliver, P. (2102). Succeeding with your literature review: A handbook for students. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education. • Polonsky, M. J. and Waller, D. S. (2005). Designing and managing a research project: A business student's guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications • Ridley, D. (2008). The literature review: A step-by-step guide for students. London: Sage Publications. • Rudestam, K. E. and Newton, R. R. (2007). Surviving your dissertation: A comprehensive guide to content and process. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- 20. Synthesising Literature • Understand: – The difference between summary & synthesis – The appropriate use of each – How to achieve each

- 21. Academic writing: the difference between Argument & • Uses critical analysis to make an informed opinion • Presents information relevant to a specific perspective, or position • Acknowledges other points of view • Answers possible challenges 4 Information • Outlines or shows a situation without analysis • Presents all information with no focussed position • Does not consider other points of view

- 22. What is synthesis? • Contextualise your own argument / research • Draw together sources that agree/disagree • Evaluate their strength and relevance • Weave them into your argument This is much more than simply finding relevant information and presenting it to the reader.

- 23. Synthesising means recognising… • … the connections between studies • … how researchers are linked or separated by the line of argument they take, or by their specific conclusions, results, methods • … broader “schools of thought” on a topic, paradigms and underpinning assumptions 8

- 24. Synthesis: What not to do •Smith (1999) states that women are better than men at reading body language. Brown (2000) found in his study that women are good at reading facial expressions. Green (2003) presented results on gender difference in ability to appreciate body language messages in communication. He reports that women perform better in certain circumstances. In contrast, Wright (1998) mentions no significant difference between the sexes in communication.

- 25. Synthesis: What not to do • Smith (1999) states that women are better than men at reading body language. Brown (2000) found in his study that women are good at reading facial expressions. Green (2003) presented results on gender difference in ability to appreciate body language messages in communication. He reports that women perform better in certain circumstances. In contrast, Wright (1998) mentions no significant difference between the sexes in communication.

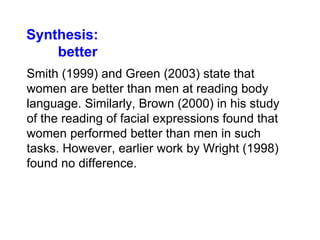

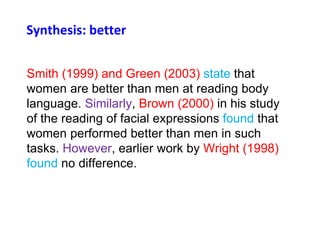

- 26. Synthesis: better Smith (1999) and Green (2003) state that women are better than men at reading body language. Similarly, Brown (2000) in his study of the reading of facial expressions found that women performed better than men in such tasks. However, earlier work by Wright (1998) found no difference.

- 27. Synthesis: better Smith (1999) and Green (2003) state that women are better than men at reading body language. Similarly, Brown (2000) in his study of the reading of facial expressions found that women performed better than men in such tasks. However, earlier work by Wright (1998) found no difference.

- 28. There is general agreement in the literature (Smith, 1999; Green, 2003; Hunter, 2012; Mickelby, 2010) that body language, including facial expression plays an important part in communication. However, the question of whether one sex is better than the other at reading body language remains unresolved. While studies by Smith (1999), Brown (2000) and Green (2003) generally claim that women are superior to men at understanding body language, Wright (1998) has found no difference. Furthermore, methodological problems raise questions about the positive results. For example, Brown's (2000) work looked solely at facial expressions asking participants to make judgements by looking at photographs. Whether these findings would be valid in real-life situations was not explored. In addition, Green (2003) used university students with a mean age of 21 as her sample, and one might question whether this sample is representative of the wider population...

- 29. Synthesis: Signs of ‘reporting’ Green (2002) discovered …. In 2006, Black conducted experiments on … and discovered that …. Later, Brown (2012) illustrated this in ….

- 30. Synthesis: Integrating your ‘voice’ •There seems to be general agreement on X (for example, Green 2002, Black 2006, White 2011, Brown 2012), but Green (2002) reports X as a consequence of Y, whereas Black (2006) puts X and Y as …. While Green's work has some limitations in that it …., its main value lies in …. This means that….

- 31. How to Synthesise: Try a matrix Key idea 1 Key idea 2 Key idea 3 Source 1 Source 2 Source 3

- 32. Bringing this all together For any of your assignments or research projects: 1. use the evidence you have taken from a range of sources 2. to write your own synthetic argument 3. written in a style appropriate for your audience and your purpose An individual consultation with a Learning Adviser might be useful to get feedback on your writing.

- 33. Big picture advice Start to read like a writer – pay attention to the way evidence is integrated into the writer’s own argument, alongside their voice. Then start to write like a reader - consider how you can best showcase your ideas alongside the ideas of others, and convince the reader of your argument.

- 34. References 22 Cottrell, S. (2003). The Study Skills Handbook (2nd Ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Greene, L. (2010). Writing in the life sciences. A critical thinking approach. Oxford, New York: OUP. pp. 123-124 Monash University (2006). Writing Literature Reviews. Retrieved April 4, 2012 from http://staging-www.monash/edu/au/lls/llonline/writing/general/lit- reviews/index.xml North Carolina State Writing and Speaking Tutorial Service (2006). Contributors were Laura Ingram, James Hussey, Michelle Tigani, and Mary Hemmelgarn. Special thanks to Stephanie Huneycutt for providing the sample matrix and paragraph. http://www.ncsu.edu/tutorial_center/writespeak RMIT Study and Learning Centre, RMIT (n.d.). Writing the literature review / using the literature. Retrieved July 29, 2009 from http://www.dlsweb.rmit.edu.au/lsu/content/2_AssessmentTasks/asess_pdf / PG%20lit%20review.pdf