Ph.D. Thesis on HBC by RS Mehta.pdf

- 1. HOME-BASED CARE TO THE PEOPLE LIVING WITH AIDS: A STUDY OF EASTERN RURAL NEPAL A dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of Tribhuvan University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in RURAL DEVELOPMENT By RAM SHARAN MEHTA Ph.D. Reg. No. 43/2064 Shrawan T.U. Reg. No. 5865-83 July 2011

- 2. LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION We certify that this dissertation entitled “Home-Based Care to the People Living with AIDS: A Study of Eastern Rural Nepal” was prepared by RAM SHARAN MEHTA under our guidance. We hereby recommend this dissertation for final evaluation by the Research Committee of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tribhuvan University, in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in RURAL DEVELOPMENT. __________________ Dr. Uma Kant Silwal Supervisor Associate Professor Central Department of Rural Development Trubhuvan University ______________________ Prof. Dr. Sarala Shrestha Expert Maharajgunj Nursing Campus Institute of Medicine Tribhuvan University Date: 22nd July 2011

- 3. APPROVAL LETTER This dissertation entitled “Home-Based Care to the People Living with AIDS: A Study of Eastern Rural Nepal” was submitted by Mr. Ram Sharan Mehta for final examination by the Research Committee of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tribhuvan University, in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rural Development. I hereby certify that the Research Committee of the Faculty has found this dissertation satisfactory in scope and quality and has therefore accepted it for the degree. ______________________ Prof. Nav Raj Kanel, Ph.D. Dean and Chairman Research Committee Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Tribhuvan University, Nepal Date :

- 4. DECLARATION I hereby declare that this Ph.D. dissertation entitled “Home-Based Care to the People Living with AIDS: A Study of Eastern Rural Nepal” I have submitted to the Office of the Dean, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tribhuvan University (TU), is entirely my original work prepared under the supervision of my supervisor. I have made due acknowledgements to all ideas and information borrowed from different sources in the course of writing this dissertation. The results of this dissertation have not been presented or submitted anywhere else for the award of any degree or for any other purpose. No part of the contents of this dissertation has ever been published in any form before. I shall be solely responsible if any evidence is found against my declaration. ................................... Ram Sharan Mehta Tribhuvan University Date:

- 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am thankful to the faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tribhuvan University (TU) for giving me the opportunity to conduct this study as a requirement of the Ph D programme. It is my proud privilege to express my profound sense of gratitude and heartfelt thanks to my esteemed supervisor Associate Professor Dr. Uma Kant Silwal, Central Department of Rural Development (CDRD), Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur for his continued valuable guidance and support throughout the period of this study. His motivational efforts, general assistance, clues to proceed further have proved a great source of inspiration to me for bringing this project to fruitful conclusions. I am deeply indebted and will remain ever grateful to Prof. Dr. Sarala Shrestha, Maharajgunj Nursing Campus, Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University for enabling me to comprehend the study and supporting me right from the selection of the problem to the conclusion of the research project and also for her professional expertise, guidance and encouragement. My heartfelt thanks go to the Head of Department, Prof. Dr. Pradeep Khadka, CDRD, TU, Kirtipur, and members of faculty of CDRD whose affection, encouragement and inspiration were a source of enduring strength for me. I am extremely thankful to Prof. Dr. Nav Raj Kanel, Dean, FoHSS and Dr. Tara Kant Pandey, Assistant Dean, FoHSS, TU, and research committee members for permitting me to conduct this study and providing me moral support. I humbly acknowledge my heartfelt gratitude to Prof. Dr. Purna Chandra Karmacharya, Vice Chancellor, Prof. Dr. Rupa Rajbhandari Singh, Rector, Prof. Dr. B. P. Das, Hospital Director, Chief, College of Nursing, Head of Department of Medical Surgical Nursing and other concerned authorities of B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS) for their continuous support and encouragement. I take this opportunity to express my sincere thanks to the Member Secretary and members of Ethical Review Board, BPKIHS for giving ethical clearance to conduct this study.

- 6. I express my deep sense of gratitude to the hospital Director/Medical Superintendents of BPKIHS, Koshi Zonal Hospital (KZH), Mechi Zonal Hospital (MZH) and Sagarmatha Zonal Hospital (SZH) for permitting me to collect the information from their hospital records, staffs, PLWHA and their caregivers attending the hospital for services. My special thanks are due to the Programme Coordinators of Home Based Care, President, Chair Person and other staffs of NGOs, Dharan Positive Group, KYC, Nav Kiran Plus, Family Health Centre, Lav Kus Ashram, NAPN and Members of District AIDS Coordination Committee (DACC) of Sunsari, Morang and Jhapa Districts for providing the relevant information about home based care and related aspects. I have no words to express my gratitude to the doctors of ART-Clinic, VCT-Nurses, VCT-Counsellor of BPKIHS, Koshi Zonal Hospital, Mechi Zonal Hospital and Sagarmatha Zonal Hospital, and key informants Ms. Anjeer Shrestha, (BPKIHS), Mr. B.P. Chaudhary (MZH), Ms. Laxmi Gautam (KZH), Dr. Lekh Jung Thapa (BPKIHS), Ms. Kamala Baral (Nav Kiran plus), Ms. Sharmila Sharstha (Family Health Centre), Ms. Laxmi Chaudhary (SZH) and Mr. Kapil Thapa (DACC, Morang), who have also supported me in data collection, focus group discussion and collecting information from People living with HIV/AIDS and their caregivers. I can not forget my respondents, the people living with AIDS and their caregivers for their cooperation and participation in the study. Without their cooperation the study would have been impossible. I express my sincere thanks to all the nursing staffs of Tropical ward of BPKIHS and all the ART/VCT counsellors and staffs of BPKIHS, KZH, SZH and MZH. I take this opportunity to express my sincere thanks to the staff of NCASC and UNAIDS for providing me the resource materials on HIV/AIDS. My special thanks are due to Mr. D.D. Baral, Assistant Professor, Statistian, BPKIHS, for his statistical assistance and support. My heartiest thanks are due to Mr. Swayam Prakash Sharma for undertaking the laborious task of editing my thesis.

- 7. I take this opportunity to express heartfelt thanks to Prof. Dr. Prahlad Karki, HOD, Department of Internal Medicine, BPKIHS; Prof. Dr. Suman Rijal, In-charge, Infectious and Tropical Disease Unit, BPKIHS; Prof. Dr. Nilamber Jha, Chief, School of Community Medicine and Public Heath, BPKIHS; Prof. Dr. Sudha Agrawal, HOD, Department of Dermatology and Coordinator of Clinical Epidemiology Unit, BPKIHS; Prof. Dr. C.B. Jha, Researcher; Dr. M.L. Das, Researcher, Dr. S.R. Niraula, Statistician; Dr. Iswari Sharma Paudel, Demographer; Mr. Sailesh Adhikari, Sociologist; Prof. Dr. Fedrick Conel, USA, Visiting Public Health Faculty, BPKIHS; Prof. Dr. Pramod Mohan Sangwa, HOD, Department of Psychiatric, BPKIHS; Prof. Dr. G.K. Singh, Epidemiologist; Prof. Dr. R.M. Pandey, Statistician, and Prof. Dr. Nita Pokhrel, former Chief, College of Nursing for their contribution during the course of project development and tool validity. I wish to express my special appreciation to all those who encouraged me for enrollment in Ph D. I owe much of the credit for this study to the reference sources cited. I humbly acknowledge my heartfelt gratitude to the University Grant Commission for providing me the Ph D scholarship grant and technical support. I want to express my heartfelt thanks to those who have helped me directly and indirectly during the course of this study. Above all my sincere thanks to God, the Almighty for giving me courage as it is said, “God helps those who help themselves”. _________________ Ram Sharan Mehta Date:

- 8. ABSTRACT HIV/AIDS is a worldwide epidemic. For social and economic development, it is a great issue. HIV and AIDS continue to spread rapidly throughout Africa and Asia, especially among young people aged 15-24 years. In world 33.2 million people living with HIV and 50,000 people infected each year. In Asia 8.3 million are infected with HIV. In Nepal first case of HIV was detected in 1988. It is estimated that 70,000 people are infected with HIV with prevalence in general population 0.55%. It has been estimated that up to 90 percent of illness care may be provided in the home by untrained family and associates, and up to 80 percent of AIDS related deaths occur in the home. Home based care is the care in the home which responds to the physical, social, emotional and spiritual needs of PLWA from diagnosis to death and through bereavement. It aims to reduce suffering and increase quality of life by providing responsive care, including self-care skills, linking clients to needed services and empowering PLWA to manage in the home. The objectives of this study were to investigate the home-based care aspects of the people living with AIDS and their caregivers; to find out the relationships between socio-demographic variables and home-based care aspects of PLWA and their caregivers; to explore the effects on the caregivers and their family related to PLWA; and to implement and evaluate an education intervention programme on home based care to the people living with AIDS and their caregivers. This study has two parts. In the first part there is aspect analysis of home based care and in the second part an education intervention programme on home based care was carried out. The first part of the study was conducted with descriptive cross sectional research design using both qualitative and quantitative methods including Interview, Focus Group Discussion, Case Study and Key Informant Interview. The study area was eastern region of rural Nepal. The people living with AIDS (PLWA) on Anti- Retroviral therapy (ART) for more than three months and their primary caregivers residing in eastern rural Nepal constitute the target population of the study. The PLWA on ART therapy and their caregivers residing in eastern region of Nepal who

- 9. fulfilled the set selection criteria was the sample of this study. Total 125 caregivers of PLWA were included in the study for individual interviews and 14 PLWA were included for case study. Six slots of focus group discussion (FGD) involving 9-11 caregivers in each slot were arranged. Thirteen Key Informant Interviews were also carried out to collect the relevant information from concerned persons involved in the care of people living with AIDS. The lists of all the PLWA belongs to Village Development Committee (VDC) were prepared from the register of ART centers of eastern Nepal and a sampling frame was prepared. Total enumerative sampling technique was used to collect the data from caregivers of people living with AIDS. The PLWA on ART therapy for more than three months and their caregivers were only included in the study. In the second part, education intervention programme, as a pilot project was designed to care for the PLWA using pre-test post-test pre-experimental research design. This programme was conducted at ART centre of B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences on every Monday, Wednesday and Friday from 11am to 1pm continuously for 8 weeks; from 1st February to 30th March 2011, so that each participant would get minimum of two chances to participate in the education intervention programme on the day of ART clinic. As per ART clinic record of 2009, it was found that a total 722 PLWHA were registered in all the four ART centers of eastern region of Nepal and among those total 299 were on ART and from 299 PLWA, 139 PLWA were from village development committee. Out of 139, only 125 caregivers of people living with AIDS who met the selection criteria were included in the study. It was found that most of the primary caregivers were female (69.6%), Hindus (92.0%), illiterate (49.6%), and unemployed (24.8%). The wives (55.2%) were the main caregivers. The majority of the (75.2%) people living with AIDS (PLWA) cared at home by the caregivers was of age group of 25-40 years and married (76.0%). Most of the PLWA (77.0%) had suffering with HIV infection for more than 6 months. Majority of the PLWA (78%) on ART for more than 6 months. Forty seven percent of the PLWA from Morang district, 32.0% from Jhapa and 8.0% from Sunsari district. Only 12.0% caregivers received home based care training, whereas 52.5% had participated in health education programme on HIV/AIDS. Majority of caregivers (60.0%) had limited knowledge about HIV/AIDS, 22.4% caregivers reported high risk of HIV transmission, whereas 20.8% reported moderate risk. The knowledge about home based care among caregivers was low. Most of the caregivers reported

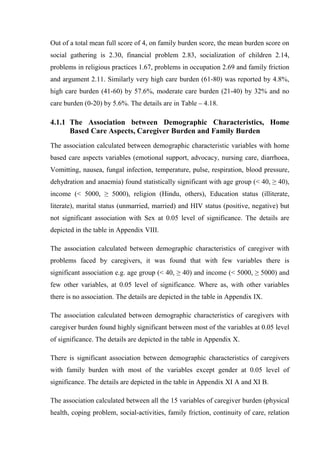

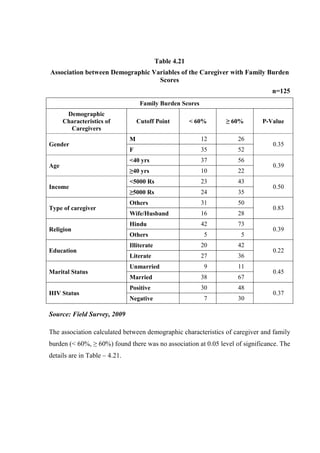

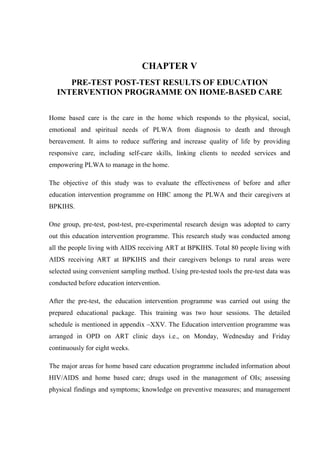

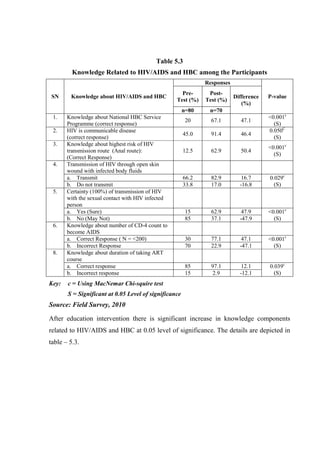

- 10. high caregiver burden (67.2 %) and high family burden (57.6 %). The majority of caregivers was suffering from stress and anxiety (60.0%), insomnia (56.0%), digestion problem (51.2%), loneliness (58.4%), headache (55.2%) and care under cover (56.8%). Most of the caregivers reported the problems in their social life (67.2%), privacy (75.2%), financial problems (82.4%) and problems of discrimination (59.2%). Only 32.0% caregivers reported that they were fully prepared to provide the care to PLWA; whereas, 38.4% reported adequately prepared, 25.6% reported somewhat prepared and 4.0% reported not prepared at all. Most of the caregiver (83.0%) spent 3-9 hrs/week on care of PLWA, 12.0% received formal HBC training and 52.5% participated in health education programme on HIV/AIDS. Majority of the caregivers (60.0%) had only limited knowledge on HIV/AIDS. The high risk of HIV transmission reported by caregivers is 22.4% , 20.8% reported moderate risk, 37.6% caregivers were HIV positive and 19.2% do not know about transmission of HIV. The services provided by caregivers were emotional support (44.2%), helping in ADL (57.6%), health care advocacy (62.4%) and nursing care (60.8%) to the people living with AIDS. The association calculated using Chi-squire test between the demographic variables with home based care aspects found statistically significant with age group and health problems of caregivers (p < 0.001), income and health problems of caregivers (p =0.03), marital status and health problems of caregivers (p = 0.02) but not significant with sex and health problems of caregivers (p =0.25). The association calculated using Chi-squire test between demographic variables and caregiver burden found significant association with marital status (p =0.02) and religion (p =0.023). Similarly, the association calculated between demographic variables and family burden score were not significant at 0.05 level of significance. The association calculated between the all 15 components of caregiver burden and 20 components of family burden found statistically significant at 0.05 level of significance. The association calculated using McNemar Chi-squire test between the difference in scores of pre-test and post-test after education intervention programme on home based care found significant in most of the variables at 0.05 level of significance. The findings of the study obtained from caregivers of people living with AIDS are supported by the results obtained from Case Study, Focus Group Discussion, and Key Informant Interview. The provision of appropriate care at all levels is hampered by the lack of human, technical and financial resources; continuing high levels of

- 11. stigma; and the fact that most people living with HIV/AIDS today do not know they are infected. The care giving process placed considerable demands on caregivers at household level, negatively impacting on their mental health. Insufficient support, lack of income and dire poverty experienced by most respondents, and the added responsibilities of caring for other household members exacerbated the psychosocial impact. The lack of support that the household caregiver received was as debilitating as the caring process. These issues need urgent attention at policy and programme levels. The findings of the study have implications in the capacity building of caregivers of PLWA for enhancing the quality of life of PLWA. It is recommended that National Centre for AIDS and STD control (NCASC) continue to support increasing access to community and home-based care as part of its national strategy and identify ways in which to expand and integration of these services into the public health care system.

- 12. TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION ii APPROVAL LETTER iii DECLARATION iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABSTRACT viii LIST OF TABLES xviii LIST OF FIGURES xviii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYM xx CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1 1.2 General and Specific Objectives 4 1.4.1 General Objective 4 1.4.2 Specific Objectives 4 1.3 Hypotheses 5 1.4 Operational Definitions 5 1.4.1 People living with AIDS (PLWA) 5 1.4.2 Home Based Care 5 1.4.3 Eastern Rural Nepal 5 1.4.4 Aspects Analysis 6 1.4.5 Home Based Care Aspects 6 1.4.6 Effects on the Family 6 1.4.7 Caregiver 6 1.4.8 Family 6 1.5 Variables of the Study 6 1.5.1 Independent Variables 6 1.5.2 Dependent Variables 7 1.6 Rationale of the Study 7 1.7 Conceptual Framework of the Study 11 1.8 Chapter Outline 14

- 13. CHAPTER II REVIEW OF THE LITRATURE 2.1 Overview of HIV/AIDS Situation 16 2.1.1 Global Picture 17 2.1.2 Asian Situation 17 2.1.3 South-East Asia Region 17 2.1.4 Situation in Nepal 19 2.2 Pathogenesis of HIV/AIDS 20 2.2.1 Definition of HIV/AIDS 20 2.2.2 Causes and Transmission of HIV/AIDS 21 2.2.3 Pathology of HIV/AIDS 23 2.3 Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS 25 2.3.1 The Current HIV Epidemic in Nepal 26 2.3.2 Reasons for Fuelling the Epidemic 26 2.3.3 Reasons for Growing Problems of HIV/AIDS in Nepal 31 2.4 Treatment, Care and Support for PLWA 32 2.4.1 Caregiver of PLWA 34 2.4.2 Home Based Care to the PLWA 35 2.4.3 Care of Dying PLWA at Home 35 2.4.4 HIV/AIDS and Quality of Life 36 2.5 Stigma and Discrimination related to HIV/AIDS 39 2.6 Conflict and HIV/AIDS 42 2.7 Need of the People Living with HIV/AIDS 44 2.7.1 Home Based Care Providers: Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices 47 2.7.2 Rights of the Infected, Affected and Vulnerable Groups 48 2.8 Importance of Home Based Care Services 49 2.8.1 Home Based Care Aspects of Care Provider 52 2.8.2 The Burden of Health Care Provider Burnout 54 2.8.3 Care for the Caregiver 56 2.8.4 Home Based Care Services 60 2.8.5 Home Care Models 60 2.8.6 Mobilization of Community Resource 63 2.8.7 Cost of Home Based Care 64

- 14. 2.8.8 The Burden of Care 65 2.9 Expanding Care Continuum for HIV/AIDS 66 2.9.1 Issues and Challenges of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Treatment Programme in Nepal 69 2.10 HIV/AIDS and Rural Development 71 2.10.1 The Impact of the Disease on People and Societies 71 2.10.2 Rural Dimensions of HIV/AIDS 73 2.10.3 Impact on Rural Development 75 2.10.4 HIV/AIDS, Poverty and Development 77 2.10.5 HIV/AIDS and Child Labour 80 2.10.6 HIV/AIDS in Rural Communities: A New Set of Challenges 81 2.10.7 HIV/AIDS, Agricultural and Rural Development 82 2.11 Effects of HIV/AIDS on Caregiver, Family and Community 82 2.11.1 The Impact of HIV/AIDS on Informal Caregiver 84 2.11.2 Advocacy, Policy, Legal Reform and Human Rights 85 2.12 Ways to Improve the Status of HBC and Rural Development: Multi- Sectoral Approach 87 2.13 Recent Data and Information Related to Home Based Care 82 2.14 Summary of Literature Review 93 CHAPTER III METHODOLOGY 3.1 Nature and Source of Data 97 3.2 Description of Study Area 98 3.3 Research Design 98 3.4 Universe Population and Sample 99 3.5 Sampling Technique 99 3.6 Research Instrument 100 3.6.1 Interview with caregivers 101 3.6.2 Focus Group Discussion with Caregivers 101 3.6.3 Case Study with People Living with AIDS 102 3.6.4 Key Informant Interview 102 3.7 Validity and Reliability of the Tool 102 3.7.1 Pre-testing of the Tool 102

- 15. 3.7.2 Reliability of the Tool 103 3.7.2.1 Reliability Test of Caregiver Burden Scale 103 3.7.2.2 Reliability Test of Family Burden Scale 104 3.8 Data Collection Procedure 104 3.9 Education Intervention Programme 105 3.10 Ethical Issues of the Research 107 3.11 Data Analysis 108 3.12 Limitations of the Study 108 CHAPTER IV ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA 4.1 Data obtained by Interviewing Caregivers 111 4.1.1 The Association Between Demographic Characteristics, Home Based Care Aspects, Caregiver Burden and Family Burden 127 4.1.2 The Association Between Values (<60% and ≥60%) of Home Based Care Aspects, Caregiver Burden, Family Burden, and Demographic Characteristics 128 4.2 Results of Case Study Obtained from PLWA 134 4.2.1 Major Findings of Case Study 136 4.3 Results of Focus Group Discussion 139 4.4 Results of the Key Informant Interview 142 4.4.1 Care Provider 142 4.4.2 Adequacy of Care Received by PLWA at their Home 142 4.4.3 Importance of HBC 143 4.4.4 Discrimination in Home and Community 143 4.4.5 Stigma in Society 143 4.4.6 Support from NGOs and INGOs at Community Level 144 4.4.7 Status of PLWA at Home and Community 144 4.4.8 Major Needs of PLWA at their Own Home 144 4.4.9 Problems of Caregivers 144 4.4.10 Some Other Important Findings of Key Informant Interview were 145 4.4.11 Suggestions for Better HBC Services for PLWA 146 CHAPTER V

- 16. PRE-TEST POST-TEST RESULTS OF EDUCATION INTERVENTION PROGRAMME ON HOME BASED CARE 5.1 Results of the HBC Education Intervention Programme 149 5.2 Discussion of the Results of Education Intervention Programme 158 CHAPTER VI SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION 6.1 Summary of the Study 160 6.2 Discussions 163 6.2.1 Demographic Profile of People living with AIDS 163 6.2.2 HIV and ART status of people living with AIDS 164 6.2.3 Demographic Profile of Caregivers 165 6.2.4 Knowledge about HIV/AIDS among Caregivers 165 6.2.5 Service Provided by the Caregivers 166 6.2.6 Preparation of Caregivers 167 6.2.7 Problem faced by Caregivers 167 6.2.8 Association between Demographic Characteristics of Caregiver with Home Based Care Aspects, Problem Faced by Caregiver, Caregiver Burden, Family Burden and Related Aspects 169 6.2.9 Association between Caregiver Burden and Family Burden 171 6.2.10 Association between knowledge, Skill and Practice related to care of Health Problems of People Living with AIDS before and after Education Intervention Programme 172 CHAPTER VII CONCLUSION AND RECOMENDATIONS 7.1 Conclusion of the Study 174 7.2 Recommendations of the Study 178 7.3 Areas for Further Studies 180 7.4 Implications of the study 181 APPENDICES 182-244 Appendix I Interview Questionnaire for Caregiver 182 Appendix II Focus Group Discussion Guidelines 191 Appendix III Case-Study Guidelines for PLWA 194

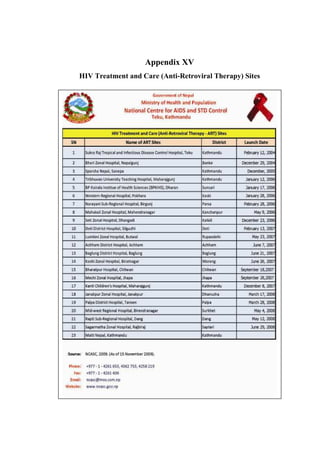

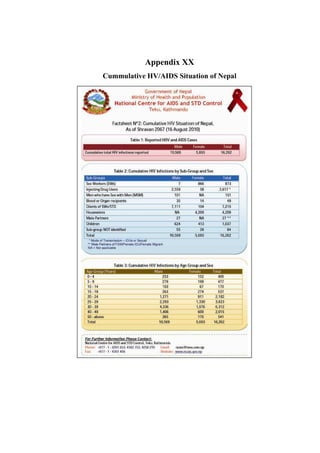

- 17. Appendix IV Key Informant Interview Guidelines 196 Appendix V List of Experts Consulted for tool Validity 197 Appendix VI Informed Consent Form 198 Appendix VII List of INGOs/NGOs Actively Involved in Care of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Eastern Nepal 199 Appendix VIII Association between Demographic Characteristics of Caregivers with Home Based Care Aspects 200 Appendix IX Association between Demographic Characteristics of Caregivers with Problem faced by Caregivers 201 Appendix X Association between Demographic Characteristics of Caregivers with Caregiver Burden 202 Appendix XI Association between Demographic Characteristics of Caregivers with family Burden 203 Appendix XII Association between Caregiver Burden with Family Burden 205 Appendix XIII Detailed Description of Focus Group Discussion 209 Appendix XIV Detailed of Key Informant Interviews 217 Appendix XV Treatment and Care (Anti-Retroviral Therapy) Sites 227 Appendix XVI CD-4 Test and Facs Calibre Sites 228 Appendix XVII Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV Sites 229 Appendix XVIII HIV and AIDS Epidemic Update of Nepal 230 Appendix XIX HIV Testing and Counseling Services in Nepal 231 Appendix XX Cumulative HV/AIDS Situation of Nepal 232 Appendix XXI List of Contents of Home Based Care Booklet 233 Appendix XXII Logistic Regression between Caregiver Burden with selected Demographic Variables and HBC Aspects Variables 237 Appendix XXIII Logistic Regression between Family Burdens with selected Demographic Variables and HBC Aspects Variables 238 Appendix XXIV Interview Questionnaire: Pré-test /Post-test 239 Appendix XXV Time Table of Education Intervention Programme 243 Appendix XXVI Ethical Clearance Letter from IERB, BPKIHS 244 LIST OF PLATES 245-249 REFERENCES 250-265

- 18. LIST OF TABLES 2.1 HIV Burden and Access to Antiretroviral Treatment in SEAR Countries 29 3.1 Details of Sampling Procedure 100 4.1 Demographic Characteristics of the People Living with AIDS 111 4.2 HIV/AIDS and Related Aspects of the PLWA 112 4.3 Socio-demographic Characteristics of Caregivers 113 4.4 Occupation and Economic Status of Caregivers 114 4.5 Home Based Care Related Aspects of Caregivers 115 4.6 Knowledge about HIV/AIDS among Caregivers 116 4.7 Knowledge about causes and Transmission of HIV among Caregivers 117 4.8 Services Provided by the Caregivers to People Living with AIDS 118 4.9 Help and Support Received by Caregivers from INGOs/NGOs Personnel 118 4.10 Preparation of Caregivers to Provide care to Health Problems to PLWA 119 4.11 Ability of Caregivers to Measure the Symptoms of PLWA 120 4.12 Problem Faced or Habits Developed by Caregivers Related to Care of PLWA 121 4.13 Satisfaction among Caregivers in Providing HBC to the PLWA 121 4.14 Responsibilities Perceived by Caregivers Providing HBC to the PLWA 122 4.15 Effects on Caregivers Related to Care of PLWA 123 4.16 Needs of the Caregivers to Provide Better HBC to the PLWA 124 4.17 Caregiver Burden Based on Caregiver Burden Scales 125 4.18 Family Burden Based on Family Burden Assessment Scale 126 4.19 Association Between Characteristics of Caregiver with Home Based Care scores 129 4.20 Association Between Demographic Variables of the Caregiver with Family Burden Scores 130 4.21 Association Between Demographic Characteristics with Family Burden Scores 131 4.22 Association Between Home Based Care Aspects with Caregiver Burden Scores 132

- 19. 4.23 Association Between Home Based Care Aspects with Family Burden Scores 133 4.24 Association Between Family Burden Scores with Caregiver Burden Scores 133 4.25 Demographic Characteristics of the PLWA Included in Case Study 134 4.26 HIV and Related Aspects of the PLWA Included in Case Study 135 4.27 Problem Faced by the People Living with AIDS (Multiple Responses) 136 5.1 Comparison of Socio-demographic Characteristics of the PLWA and their Caregivers involved in Education Intervention Programme 150 5.2 ART and HIV Related Status of the PLWA and their Caregivers 151 5.3 Knowledge Related to HIV/AIDS and HBC among PLWA and their Caregivers 152 5.4 Differences in knowledge about drugs used in the Management of OIs among Caregivers after Education Intervention 153 5.5 Differences in Ability to access the Vital Status among the PLWA and their Caregivers after Education Intervention 154 5.6 Differences in knowledge and Practices on Using Preventive Measures after Education Intervention 155 5.7 Differences in the Ability to Manage the Common OI Symptoms at Home 156 5.8 Suggestions given by Caregiver to improve HBC at their Home 156 5.9 Evaluation Related of the Education Intervention Programme 157 LIST OF FIGURES 1.1 Conceptual Framework based on WHO HIV/AIDS Care Continuum Model 14 2.1 HIV/AIDS Situation in Nepal: At a Glance 30

- 20. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ARV Anti-Retroviral ART Anti-Retroviral Therapy BPKIHS B. P. Koirala Institute of Health Science BTS Blood Transfusion Service CBO Community Based Organization CHBC Community Home Based Care CSW Commercial Sex Worker DoHS Department of Health Services FCHV Female Community Health Worker HBC Home Based Care HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus IDU Injecting Drug User IEC Information, Education and Communication ILO International Labour Organization INGO International Non Government Organization MDR Multi-Drug Resistance MoH Ministry of Health MSM Men Who Have Sex with Men NCASC National Center for AIDS and STD Control NACC National AIDS Coordination Committee NFE Non Formal Education NGO Non Government Organization NHEICC National Health Education, Information and Communication Center NHTC National Health Training Center NRCS Nepal Red Cross Society OI Opportunistic Infection PLWA People Living with AIDS PLWHA People Living With HIV and AIDS PMTCT Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission STD Sexually Transmitted Disease STI Sexually Transmitted Infection VCT Voluntary Counseling and Testing VDC Village Development Committee UNGASS United Nations General Assembly Special Session

- 21. CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Globally more than 34 million people were living with HIV at the end of 2010 (UNAIDS, 2010). Total 30.8 millions of adults and 2.5 million children were living with HIV in 2009. The people newly infected with HIV in 2009 were 2.6 million; total AIDS deaths were 1.8 million and over 7000 new HIV infections a day. About 97% of people living with HIV were in low and middle income countries (UNAIDS, 2009). Social and economic vulnerabilities, including poverty and illiteracy, highlight the need to act effectively and aggressively to reduce its spread. South Asia has about 4.2 million of the world’s 36 million people living with HIV/AIDS. While overall prevalence rates remain relatively low, the region’s large populations mean that a rise of a mere 0.1percent (NCASC, 2007). Delay in diagnosing HIV infection, continuing stigma, the high cost of the drugs for treating the disease, and limited health system capacity is preventing more than a million people in South-East Asia from receiving vital HIV treatment, prevention and care. More than two out of three HIV-infected people in need of treatment do not receive life-saving antiretroviral treatment in WHO’s South-East Asia Region. Only 577000 people (32%) of those in need receive this treatment. The Region has the second highest burden of HIV in the world after Sub-Saharan Africa; with an estimated 3.5 million people infected and 230 000 AIDS-related deaths. An estimated 1.3 million women aged 15 and above currently live with HIV in the Region. The estimated number of children living with HIV increased by 46% during 2001 to 2009 (NCASC, 2009) Lack of information about the disease is a significant contributing factor to the escalation of HIV/AIDS. The communities most affected by HIV/AIDS lack the

- 22. most basic information about health care, human, sexual and reproductive rights (Underwood, 2006). The current situation of HIV in Nepal is different from when the first case was diagnosed in 1988. There are gaps and challenges to be addressed in the fight against HIV and AIDS. Nepal is low prevalence (0.5 percent) country for HIV and AIDS. However, some of the groups show evidence of a concentrated HIV epidemic e.g. sex workers (19.5 %,) migrant population (4.0 to 10.0%), and intravenous drug users (IVDU's), both in rural and urban areas (68.0 %). Since 1988, MoHP/DoHS and different stakeholders came forward to address HIV and AIDS issues. The main focus was given to preventive aspects. In 1995 MoHP in consultation with different stakeholders developed a policy for the control of HIV and AIDS. However, the activities were implemented in a sporadic and disorganized manner (NCASC, 1996). National Centre for AIDS and STDs Control (NCASC)/Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) came to the conclusion that every stakeholder working in the field of HIV and AIDS should come forward and work under one umbrella within the framework of a single policy. As a result in 2002 a new strategy for HIV and AIDS was developed for 5 years (2002 to 2006) and consequently an operational work plan was developed for 5 years (2003 to 2007). However, there are many gaps that were not identified during development of the New Strategy Guidelines that need to be addressed while revising it in 2006. The new strategy spotlights the following main areas i.e. vulnerable groups, young people, treatment, care and support, epidemiology, research and surveillance, management and implementation of an expanded response (NCASC, 2006). Broad political commitment, a multi-sectoral approach, civil society involvement, public-private partnership, reduction of stigma and discrimination against people infected and affected by HIV/AIDS and human rights based approach have been outlined as some of the guiding principles in the development of the strategy. To enable high level and multi-sectoral commitment in the response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Nepal, a high level National AIDS Council (NAC) chaired by the Prime Minister was formed. There is a National AIDS Coordination Committee (NACC)

- 23. chaired by the Minister of Health which is responsible for reviewing and approving work plans and budgets, reviewing reports, and guiding implementation of the national strategy. The NCASC has the authority for technical review and advice on policy and funding issues and acts as the secretariat to the NACC. The NACC reports to the NAC. There is also a Steering Committee chaired by the Health Secretary that meets on a regular basis to review programme activities as well as to guide and direct programme implementation (NCASC, 2009). The presence of multiple terms used to describe the effects of care giving may lead to confusion in synthesizing care giving aspects. Investigators have documented the negative biopsychosocial effects associated with providing care for a relative or friend. Understanding the concepts related to care giving experiences and the relationships among them can enable health workers to better address the needs of caregivers (Hunt, 2003). The home based family caregiver burden is due to personal problem of caregivers, financial limitations, inadequate resources, inadequate knowledge and insufficient support. The home based care outcomes to PLWA can be categorized in positive, negative and neutral terms. Hunt (2003) mentioned that in positive terms it’s called caregiver esteem, caregiver satisfaction and uplifts of caregiver. The negative consequences include caregiver burden, caregiver stress, and caregiver strain. The neutral term used are caregiver appraisal, caregiver well being and quality of life. Most of the caregiver outcomes have shown the negative effects i.e. called caregiver burden. The caregiver burden is both predictor and outcome. The perceived burdens are related to emotional, physical, social life and financial status of care providers. The concept of family need not be limited to ties of blood, marriage, sexual partnership or adaptation. This can be extended to individuals whose bonds are based on trust, mutual support and a common density may be regarded as a family. All families, traditional or non-traditional, can help stop AIDS spreading by ensuring that their members understand and follow safer behaviour and if one of their members does fall ill with AIDS, families are often the best sources of compassionate care and support (Hunt, 2003).

- 24. Most of the HIV and AIDS home care is carried out by family members who have no contact with professional help and suffer through lack of support. This means that infected people are inadequately looked after despite the best efforts of their carers and families who face economic, psychological and social difficulties. Studies have shown that the most effective home based care programme involve ongoing support for their workers, support from local communities and integration within existing health systems. However, many home based care programme had, inadequate help from home based care organizations, limited resources, risks faced by carers and economic burden on the family (Opiyo et al., 2008). In developing countries, families are the primary caregivers to sick members. There is clear evidence of the important role that the family plays in providing support and care for people living with HIV/AIDS. However, not all-family response is positive. Infected members of the family can find themselves stigmatized and discriminated within the home. This study explores the various aspects of home-based care to the PLWA and the effects on the caregivers and the family residing in eastern rural Nepal. Based upon the finding of the aspects analysis of this study, the available literature, WHO and NCASC guidelines the education intervention programme was implemented and the effectiveness was evaluated. 1.2 General and Specific Objectives 1.2.1 General Objective The overall objective of this study is to examine the aspects of home-based care to the people living with AIDS and their effects on caregiver and family in Eastern Rural Nepal 1.2.2 Specific Objectives The specific objectives of this study are: a. To measure the home-based care aspects to the people living with AIDS and their caregivers.

- 25. b. To find out the relationships between socio-demographic variables and home-based care aspects of people living with AIDS and their caregivers. c. To find out the level of burden on caregivers and their family. d. To evaluate the effects of education intervention programme on home- based care to the PLWA among the caregivers. 1.3 Hypotheses Ho1: There is no association between socio-demographic variables of caregiver with home-based care aspects, caregiver burden and family burden. Ho2: There is no relationship between caregiver burden and family burden. Ho3: There is no significant difference between before and after education intervention programme in relation to knowledge and practice of care of people living with AIDS among the caregivers along with PLWA. 1.4 Operational Definitions 1.4.1 People living with AIDS (PLWA) The diagnosed and registered AIDS clients at ART centres, getting anti-retroviral therapy and residing in eastern region of rural Nepal are called people living with AIDS. 1.4.2 Home Based Care The care provided to the PLWA by the caregiver at their home is called home based care. It includes the physical, psychological, social and spiritual care to the PLWA. It also includes the provision of arrangement of resources and support to the PLWA at the family level. 1.4.3 Eastern Rural Nepal All the village development committee (VDC) of eastern region of Nepal is included in eastern rural Nepal.

- 26. 1.4.4 Aspects Analysis It includes the analysis of home based care provided to the people living with AIDS by the caregivers. 1.4.5 Home-Based Care Aspects Home-based care aspects includes the knowledge about HIV/AIDS, service provided to the PLWA, support received from NOGs/INGOs, assessment of health of PLWA, management of physical health problems, problems faced by caregivers, level of preparation to provide the care to PLWA, needs of caregivers for effective home based care to the people living with AIDS provided by the caregivers at family level. 1.4.6 Effects on the Family Effects on the family include the personal problems of caregivers, financial limitations, inadequate resources, inadequate knowledge and insufficient support. It also includes the stigma and discrimination along with burnout syndrome. Effects on family were assessed by using family burden assessment scale. 1.4.7 Caregiver It includes mainly the primary caregiver to the PLWA in the family who provides most of the care to the PLWA. 1.4.8 Family The concept of family in this study is not limited to ties by blood, marriage, sexual partnership or adaptation. Any group whose bonds are based on trust, mutual support and a common density is regarded as a family. 1.5 Variables of the study 1.5.1 Independent variables a. Socio-demographic characteristics of PLWA and their caregivers: sex, age, religion, caste, education, marital status, occupation and health status. b. Education intervention programme on home-based care

- 27. c. Other related co-variables (home-based care aspects): knowledge about HIV/AIDS, service provided to PLWA, support received form NGOs/INGOs, assessment of health status of PLWA, management of physical health problems, problems faced by caregivers, level of preparation of caregivers and need of caregiver. 1.5.2 Dependent Variables a. Effects on caregiver: The effect on caregivers was measured by using 15 items five points caregiver burden assessment tool based on the scale developed by Robinson (1983), where Cronbach’s alpha is 0.86. b. Effects on family: The effects on family was measured by using 20 items five points family burden assessment tool, based on the scale developed by Kipp et al. (2006), where Cronbach’s alpha is 0.87. c. Knowledge and practice on home based care. 1.6 Rationale of the Study The demands and outcomes on the family caregivers of PLWA are enormous and need to be addressed in terms of public health policy, health economics and patient care perspectives. The care for PLWA is provided through general and infectious disease hospitals in Nepal. The increasing demand of family caregivers involves the patient care. The studies have shown that AIDS clients would rather stay with their families at home than in a hospital. The necessary emphasis on family care giving is even more significant because the family member is given the responsibility of the care of people living with AIDS. There has been a growing interest over the past 20 years in exploring the care giving experience. Over the course of the AIDS epidemic, family caregivers have provided an essential source of care to PLWA. The assessment of burden has become a challenging task for most researchers. The literature suggests that the characteristics of the caregiver, the characteristics of the patient, stigma and the nature of the care giving relationship are the determinants of caregiver burden (Vithayachockitikhum, 2006).

- 28. An extensive body of literature underscore that providing care to an ill family member is a stressful experiences for the entire family. Most of the care giving research has disproportionately focused on negative caregiver outcomes. Studying this aspect is of significance because social support has shown to be positively related to good health. It is associated with better health outcomes, better coping and less negative effects of stress which is particularly relevant in the context of HIV/AIDS. The PLWA has a lot of physical health problems that needs care. The problems that need care are: Fever, Headache, Weight Loss, Anorexia, Oral thrush, Cough, Diarrhoea, Skin infection and Tuberculosis. Along with physical health problems PLWA experience emotional and psychological problems to a great extent. The families experienced enormous burdens related to financial limitations, inadequate resources, and insufficient support (Fitting & Robins, 1985). AIDS in some African countries is already affecting sizeable populations and has important implications for development. At the most basic level, it increases morbidity (illness) and mortality (death), particularly among young adult populations; decreases life expectancy, and increases infant and child mortality rates. The full impact is not clear, as nowhere has the epidemic run its course. HIV/AIDS is of concern in the rural development sector. Evidence shows that in many countries there is currently a lower rate of HIV infection in rural areas. For example in Zambia in 1993, prevalence rates among women ranged from 33.3% in urban areas to 13.2% in rural (Agbonivtor, 2009). However, in other countries, for example Swaziland and South Africa, there is little difference in the infection rates between the rural and urban areas. The key determinant of the differential levels of infection is the amount of movement and interchange between urban and rural areas. Ironically, successful rural development will facilitate this process. It is possible that, even in rural areas with current low levels of HIV infection, these may climb, and in time approach those of the urban areas. Even if there is a differential between rural and urban areas, the rural sector will not be immune to the impact of the epidemic.

- 29. The area of this study is eastern rural Nepal, where there is HIV/AIDS endemic especially in Dharan, Biratnagar, Itahari, Kakarbhita, Rajbiraj, Lahan and Damak. The eastern region of Nepal is very prone to HIV/AIDS because there are a lot of IV drug users in Dharan. Lauhure is the main occupation of majority of people residing in Dharan, Ithari, Damak, and eastern hilly districts. Eastern border of Nepal, Kakarbhita, is very near to Indian city of New Jalpaigudi, Siliguri and Darjeeling. Southern boarder of Nepal is also open and rural people go to India, especially Punjab, Delhi, Mumbai and other major cities frequently for earning and labour work. In eastern Nepal, especially Jhapa and Morang there are major issues of Bhutanese refuges, where the problem of HIV/AIDS is also prevalent. These are the common reasons for increasing HIV infection in eastern Nepal. In eastern region of Nepal the main towns are Dharan, Biratnager, Itahari, Damak, Inaruwa, Rajbiraj, Bhadrapur, and Kakarbhita, where the rate of migration of people from urban to rural and rural to urban is very high. Many people residing in eastern Nepal are also involved in foreign labour, especially in the Gulf countries, that leads to increase in the number of HIV infection related to high risk sexual behaviour. The NCASC data show that eastern region of Nepal is the area most prone to HIV/AIDS. In eastern region of Nepal there are four ART centers situated at Dharan, Rajbiraj, Biratnagar and Bhadrapur. Some other centres are going to be established in the near future as per plan of NCASC. The investigator is interested to conduct this study in eastern region of Nepal, in order to explore new facts that can be practical and useful in policy implications, and problem solving. Home based care to the PLWA is not the alternative service of hospital care and professional health care providers’ services, it is a complementary service. It includes the physical, social, psychological and religious needs of the PLWA. The main aim of home based care is to develop insight and positive thinking among the PLWA and their care provider family members. Home based care programme helps to regulate the services of PLWA in the family and community; Increases knowledge regarding prevention, treatment, and care of

- 30. PLWA; Makes capable to obtain long term services for PLWA; Boost-up Care Provider for long term quality care; Able to manage the symptoms, Prevent and care the problems related to opportunistic infection; Decrease the negative feelings and stigma related to HIV/AIDS in the family and society; Make patient capable to obtain available services in health care institutions; Provide quality services to PLWA easily and Help utilize local resources of the community properly to care the PLWA. Advantages of home-based care are: • It frees up the number of hospital beds available for those who are very ill or suffering as a result of other diseases and accidents. • It involves the community in directly taking responsibility for HIV/AIDS. • It allows people who are ill to spend their days in familiar surroundings and stops them from being isolated and lonely. • It gives families access to support services as well as emotional support. • It promotes a holistic approach to care and does not only focus on narrow health needs. • It is pro-active and helps keep people healthy for longer. • It involves the patients in their own care and gives them more rights to decide about what should be done. • Many of the common diseases or conditions can easily be managed at home with the right training. • It takes a big burden off the family, especially children. • Home-based care focuses on the individual patient and her/his needs. • It avoids unnecessary referrals or admissions to hospitals and institutions. • It helps to co-ordinate different services in the community and get them all to people who need it through one volunteer. • It helps to collect data and to record information about what is happening in the community. • It makes sure that there is consistency of services and that everyone gets access to things like grants, projects and food parcels.

- 31. Ninety percent of people that are ill are cared for by their relatives. It is important that the relatives are properly equipped to do this work and get the emotional support they need. Where relatives are unwilling to look after someone, the home-based care project will have to give more regular support and make sure that the person is not neglected. Keeping all these facts in mind the investigator has decided to conduct the study on, “Home Based Care to the People Living with AIDS in Eastern Rural Nepal: An Aspects Analysis”. 1.7 Conceptual Framework of the Study People with HIV/AIDS can live healthy lives for longer if proper care and support is provided. People who are ill with AIDS need much more care than our hospitals and clinics can provide. It is vital that health workers work with communities and families to make sure that people who are ill at home get proper care. This is where the idea of home-based care comes from. It is very important that the more direct support and care roles are played below a hospital level so that the hospital can do the things that it does best for diagnosis, treatment and medication. Family members are most often the direct caregivers for people who are ill. Families do the basic washing, cleaning and feeding and it is important they get both training and emotional support. Where the patient does not have a direct caregiver, the volunteers will have to do this work. If family members are available to provide some care, they should be trained by the volunteers who can also give some emotional support. Family members over 12 can be trained in basic hygiene, dealing with simple infections, basic nutrition, bed baths dealing with blood and body fluids. They should learn how to protect themselves from infection, For example, covering your hands with a plastic bag when you deal with blood can save your life. The volunteers should give these families access to information, make referrals to other service providers and distribute food parcels and so on. They can also help people who are ill to get medication from the clinics through their links with the health workers.

- 32. People with HIV/AIDS can look after themselves while they are able to. They should be encouraged to keep themselves as healthy as possible and should be targeted for specific programs such as: Wellness programs to keep as healthy as possible and to strengthen immune systems, Nutrition programs, Training in basic hygiene and treatment for common infections like skin infections. They themselves should be trained in basic health care and where possible should be drawn into support and other activity groups. It is very important for home-based care projects to target all people who are ill and being looked after at home. The review explores the specific issues that cluster around the provision of care in the context of the global HIV/AIDS pandemic. The concept of the ‘care economy’ provides a useful lens through which to view the HIV/AIDS pandemic, as it illuminates the increased labour, time and other demands placed upon households and shows that the assumptions on which norms and expectations of care provision are based are increasingly being challenged. While some studies are being made in policy and programme around HIV and AIDS related care, much more needs to be known and done to enable individuals, families and households to survive in a world shaken by AIDS. A strategy of simply downloading responsibility for care into women, families and communities can no longer be a viable, appropriate or sustainable response and this is no less true in this current era of expanding treatment options for people living with HIV and AIDS. Home based care (HBC) is one of the models of care that deliver health care and other support to PLWHA and their families. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines HBC as the provision of services in support the HIV/AIDS care process that take place in the home of the HIV-infected person (WHO, 1989). It includes physical, psychosocial, palliative, and spiritual activities (WHO, 2002) such as clinical monitoring and management of opportunistic infections (prophylaxis and treatment), counseling, food supplementation/nutrition, and clean water. Services are provided by a mix of staff that usually includes community volunteers, community health workers, nurses, doctors, and other professionals. Other models of care that deliver health and support services to PLWHA and their families may require the

- 33. PLWHA to travel to a community center to obtain food and counseling, and to a health center for palliative care. Home-based caregivers were particularly valued for home visits, because they provided much needed material support. They counselled PLWA and their carers, provided palliative care, cooked and cleaned the house. They provided a much- needed respite for respondents who felt emotionally strengthened by their visits. A bonus for respondents was an informed home-based caregiver. NGOs were valued by respondents because they met needs that the health services could not. In contrast, some caregivers felt that home-based carers ignored them and only gave support to the PLWA. A conceptual framework is an integrated model of care designed to meet the health needs of the patients, families and communities. According to Stanhope and Lancaster (2004), it is important to have a conceptual framework in research because it gives a basis for making decisions and establishing priorities. It also gives the researcher an opportunity to examine programme systematically for deficiencies to deal with potential problems. Lastly, conceptual framework serves to explain why things are done in a particular way. The conceptual perspective which has been described in this chapter to guide the present study is quality of care which can determine the quality of life for PLWHA. Through the thick descriptions of the experiences from the participants in this study, it was possible to determine the deficiencies in the implementation of HBC to PLWA in Eastern Rural Nepal. Home based care is not only an important mechanism for extending the continuum of care by providing at home the basic nursing care and treatment necessary for many of the afflictions that strike PLWHAs. It also promotes community awareness of HIV/AIDS, provides an example to motivate behaviour change and decrease the stigma attached to the disease, and enables PLWHAs to maintain their family and community roles. Home-based care is cost effective as well. It frees up hospital beds and medical personnel for the acutely ill and thus relieves the burden on the health care system (UNAIDS, 2002).

- 34. The model for HIV/AIDS care continuum developed and used by WHO (2004) is depicted in figure 1.1. Figure 1.1. Conceptual Framework based on WHO HIV/AIDS Care continuum model Source: WHO, 2004 1.8 Chapter Outline This dissertation is written in seven chapters. The first chapter is introduction, which contains background of the study, objectives, rationale of the study, research question, null hypothesis, operational definitions, variables, limitations of the study and conceptual framework. In chapter two, review of literature is presented in fourteen sub-headings. In chapter three, there is description of methodology, described under the various sub-headings including research design, sampling technique, validity of tool, reliability of the tool, data collection procedure, education intervention programme, ethical issues of the Social Support Services Peer Support and Voluntary Services Hospitals, HIV Clinics, Specialists and Specialized care Facilities: Direct Care, Infection Control, Terminal Care Homes, Community & Hospices Services Health Centre, Dispensaries, Traditional Care: Governmental & Non- governmental HIV Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT) PLWA & their Caregivers Care Seeking/Providing/Referral

- 35. research, methods of data analysis and limitations of the study. The chapter four is analysis and interpretation of data, described under main four sub-headings including data obtained by interviewing caregivers, results of case study obtained from people living with AIDS, results of focus group discussion and the results of key informant interview. In chapter five, there is description of results of education intervention programme, described under various sub-headings. Chapter six describes the summary of the study and discussion. Chapter seven includes conclusion and recommendations. The relevant documents and materials are included in appendices. Some relevant photographs are depicted in the list of the plates heading. At the end of the dissertation list of all the references cited are included.

- 36. CHAPTER II REVIEW OF THE LITRATURE In accordance with the subject for study, an extensive review of the relevant literature was carried out through the published national as well as international text books, periodicals, journals on medicine, nursing and public health. Surfing of the internet and Medline was carried out to collect the latest information pertaining to the subject. The literatures that were reviewed related to the subject are presented under the following heads: 2.1 Overview of HIV/AIDS Situation 2.2 Pathogenesis of HIV/AIDS 2.3 Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS 2.4 Treatment, Care and Support of People Living with AIDS 2.5 Stigma and Discrimination Related to HIV/AIDS 2.6 Conflict and HIV/AIDS 2.7 Need of the People Living with AIDS 2.8 Home-Based Care Services and Costs 2.9 Expanding Care Continuum for People Living with AIDS 2.10 HIV/AIDS and Rural Development 2.11 Effects of HIV/AIDS on Caregiver and Family 2.12 Ways to Improve the Status of Home Based Care 2.13 Recent Data and Information Related to HIV/AIDS and HBC 2.14 Summary of Literature Review 2.1 Overview of HIV/AIDS Situation Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infects humans. A person with HIV is infected for life and can infect others. The virus attacks the immune system and slowly weakens the body’s defense against diseases. An HIV-infected person can

- 37. look and feel well for a long time without developing AIDS (Armirkhanian et al., 2003). Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a disabling and deadly disease caused by HIV. “Acquired” means something not inherent in the patient’s body but transmitted from others; “immunodeficiency” refers to the weakened ability of the body’s immune system that helps it ward off infections and diseases; and “syndrome” is the group of signs and symptoms associated with the disease. AIDS occurs as a collection of infections called opportunistic infections that are usually severe, such as pneumonia or tuberculosis, manifest more often during the late stages of HIV infection. An HIV infected person may not develop AIDS until 8 to 10 years after being infected (Beine, 2003). 2.1.1 Global Picture HIV/AIDS is a fourth biggest killer worldwide. Estimated 40.3 million are living with HIV; about one-third are aged 15-24 years. Most people don’t know they are infected. Young women are especially vulnerable. More than 95% are in low or middle-income countries. In 2005 about 4.9 million new HIV infections was added and 3.1 million deaths occurred due to AIDS. About 14,000 new HIV infections a day in 2005 and more than 95% are in low and middle-income countries (WHO, 2006). 2.1.2 Asian Situation There is high HIV prevalence in India, Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand. There is Low HIV prevalence among women in antenatal clinics but relatively high among IVDUs in Nepal, China and Malaysia. There is low HIV prevalence in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Indonesia, Maldives and Srilanka (NCASC, 2006). 2.1.3 South-East Asia Region Although the HIV prevalence rate is still low in South East Asia, it is one of the most rapidly growing epidemics globally. Because of the largest population base and presence of several factors that enhance the spread of HIV, including poverty, gender

- 38. inequality and social stigma, the South-East Asia Region is likely to increasingly suffer the brunt of the epidemic (NCASC, 2006). As per report (WHO SERO, 2006) there is an estimated 6.7 million people are living with HIV/AIDS in South-East Asia in 2005; it is the second highest number of cases in the world after sub-Saharan Africa. It is estimated that less than 10 percent of infected persons are aware of their HIV status. India, with 5.1 million HIV/AIDS cases, is second only to South Africa in terms of the numbers. Six states in the country, namely, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Manipur, Nagaland and Tamil Nadu bear the highest burden. Report (WHO, 2006) also mentioned, the majority of HIV infections in the Region occur through unprotected sex between men and women. Throughout the Region, injected drug use is adding to the rapid spread of the epidemic. Around half of injection drug users have already acquired the infection in Nepal, Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia, Manipur and Nagaland states in India. An estimated 9,50,000 persons living with HIV/AIDS in the Region urgently require antiretroviral treatment. The number of people on treatment was doubled during 2004 and nearly 163,000 persons are receiving antiretroviral treatment at the end of December 2005 (WHO SERO, 2006). In South-East Asia Region, the HIV epidemic remains highly dynamic, posing tremendous challenges to the public health system. An estimated 3.5 million people are living with HIV/AIDS in the Region. Women account for 33% of total people living with HIV. In 2008, about 2,00,000 people were newly infected with HIV and 2,30,000 died of AIDS related illnesses (WHO, 2006). The overall HIV prevalence in the region is slowly decreasing. However, country wise differences exist. In the parts of India, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Thailand, HIV prevalence is decreasing or stabilizing although pockets of high transmission remain. HIV infection is rapidly increasing in Indonesia. The majority of the HIV infections are transmitted sexually. Injecting drug use is an important route of HIV transmission in several countries. In Thailand, a third of all

- 39. new infections are among low-risk women from their HIV-infected regular male partners or husbands. Overall, HIV prevalence among the adult population is low (0.3%) in the Region, but sex workers and their clients, men who have sex with men and transgender populations as well as injecting drug users are disproportionately affected by HIV. In some areas (Thailand and south India), HIV prevalence has decreased among female sex workers; however, there is evidence of continuing high transmission among injecting drug users and increasing HIV infection among men who have sex with men in large cities (WHO, 2006). Consistent condom use with paying partners is reaching optimal levels among sex workers; however, men who have sex with men, transgender populations and injecting drug users have low rates of condom use. Men who have sex with men have multiple partners and a large proportion of them are married to women. 2.1.4 Situation in Nepal There is an estimated 0.5% national prevalence, concentrated epidemic, estimated 70, 256 infected, about 12.0% of these have been tested, about 3000 deaths per year. In Kathmandu HIV prevalence among IV drug users (IDU) is 51.1% and among female sex workers (FSW) is 4.0%. Estimates of prevalence of HIV-positive among labour migrants returning from India range from 4.0 to 10.0% (WHO, 2006). In Nepal the estimated number of PLWHA at the end of 2005 was 61,000. HIV prevalence in 2005 was 0.5%, estimated number of AIDS cases is 7,800, the number of children (0-18) orphaned by HIV/AIDS is 18,000 and receiving Anti Retroviral Treatment (ART) till December 2005 was 210. HIV infection has taken root in South Asia and poses a threat to development and poverty alleviation efforts in the region. HIV infection is fuelled by risk behaviour, extensive commercial sex, low condom use and access, injecting drug use, population movements (cross-border/rural-urban migration), and trafficking (WHO/UNAIDS, 2006). Social and economic vulnerabilities, including poverty and illiteracy, highlight the need to act effectively and aggressively to reduce its spread. South Asia has about

- 40. 4.2 million of the world’s 36 million people living with HIV/AIDS. While overall prevalence rates remain relatively low, the region’s large populations mean that a rise of a mere 0.1percent in the prevalence rate in India, for example, would increase the national total of adults living with HIV by about half a million persons (Singh et al., 2006). The current situation of HIV in Nepal is different from when the first case was diagnosed in 1988. There are gaps and challenges to be addressed in the fight against HIV and AIDS. Nepal is low prevalence country for HIV and AIDS. However, some of the groups show evidence of a concentrated HIV epidemic e.g. sex workers (19.5%), migrant population (4.0-10.0%), and intravenous drug users (IVDU's) both in rural and urban areas (68.0%). Now, different stakeholders have come forward to address HIV and AIDS issues (NCASC, 2006). A significant percentage (60.0%) of HIV positive patients belongs to lower socio- economic class and many of them were mobile workers and contracted their illness while working in Indian metropolis in the past (MOPH, 1996). 2.2 Pathogenesis of HIV/AIDS 2.2.1 Definition of HIV/AIDS HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) is a virus that causes AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome), a health condition in which a person is affected by a series of diseases because of poor immunity. HIV by itself is not an illness and does not instantly lead to AIDS. There is no way of knowing whether just looking at them infects someone. An HIV-infected person can lead a healthy life for several years or she can instantly pass the virus to others. AIDS is a health condition where the body’s immune system is gradually destroyed following an HIV infection. Over a period of time, the immune system weakens and the body loses its natural ability to fight against diseases. Eventually the infected person may lose weight and become ill with diseases like persistent severe diarrhoea, fever, skin diseases, pneumonia, TB or tumors. At this stage, he or she has now developed AIDS.

- 41. To reduce the transmission of HIV/AIDS, a number of activities have been undertaken over the last decade. National Centre of AIDS and STD Control (NCASC) was established in 1993. NCASC is a coordinating body under the MOH, which looks after the AIDS and STD preventive activities in the country (NCASC, 2003). 2.2.2 Causes and Transmission of HIV/AIDS The predominant mode of transmission of HIV in Nepal is heterosexual contact with commercial sex workers. HIV prevalence rates are about 4.0% among sex workers in the Terai regions of Nepal and about 1.5% in their clients (which is more than five times the national average prevalence). In Kathmandu, nearly 17.0% of sex workers are HIV-positive. There are about 25,000 sex workers in Kathmandu and an estimated 200,000 Nepalese women working in Indian brothels. About 5,000 to 10,000 Nepalese sex workers are trafficked every year; numbers are likely to increase as a result of the conflict. One striking estimate is that nearly 70% of sex workers returning from India are HIV-positive (NCASC, 2003). More people are travelling and working away from home due to global economy. Men have more sex with sex workers, contract HIV and return home to their wives, who contract HIV and pass it along to their infants in uterus or through breast milk (NCASC, 2006). Among injecting drug users, estimated to be about 30,000 in Nepal, about 40.0% are HIV-positive. Needle sharing and risky sexual behaviour are common in this group. The figures are particularly alarming in Kathmandu, the capital city, where nearly 68% of injecting drug users is HIV-positive. A subtype C virus with restricted genetic diversity is thought to have caused this epidemic in Kathmandu. Concomitant hepatitis C infection is a contributing factor to the rapidity and severity of disease progression in injecting drug users, and 94.0% of users in Kathmandu have tested positive for hepatitis-C (NCASC, 2003). Similarly, NCASC also reported, denial and silence regarding HIV are the norms. People with HIV are stigmatized for many reasons like: HIV is a slow, incurable

- 42. disease, resulting in illness and death. HIV is considered a death sentence; People often do not understand how HIV is spread and are irrationally afraid of acquiring it from those infected with it. HIV transmission is often associated with moral violations of social mores concerning sexual relations, so people with HIV are tainted with the notion of their having done something “bad.” People tend to stigmatize or blame certain groups for spreading HIV, for example, sexually promiscuous people or drug users. Stigma prevents people from speaking about or acknowledging HIV as a major cause of illness and death. Stigma prevents HIV-infected people from seeking care and from taking preventive measures. Even when counselling and testing are offered, people may not want to know if they are infected for fear of being stigmatized; this fuels the spread of the disease. In many societies people living with HIV and AIDS are often seen as shameful. In some societies the infection is associated with minority groups or behaviour, for example, homosexuality, in some cases HIV/AIDS may be linked to 'perversion' and those infected will be punished. Also, in some societies HIV/AIDS is seen as the result of personal irresponsibility. Sometimes, HIV and AIDS are believed to bring shame upon the family or community and whilst negative responses to HIV/AIDS unfortunately widely exist, they often feed upon and reinforce dominant ideas of good and bad with respect to sex and illness, and proper and improper behaviour (UNAIDS, 2006). HIV/AIDS is a life-threatening disease. People are scared of contracting HIV. The disease is associated with behaviours (such as sex between men and injecting drug- users) that are already stigmatized in many societies. People living with HIV/AIDS are often thought of as being responsible for becoming infected. Religious or moral beliefs lead some people to believe that having HIV/AIDS is the result of moral fault that deserves to be punished (UNAIDS, 2006). Cultural traditions, beliefs and practices affect people’s understanding of health and disease and their acceptance of conventional medical treatment. Culture describes

- 43. learned behaviour affected by gender, home, religion, ethnic group, language, community and age group. Culture can create barriers that prevent people, especially women, from taking precautions. For example, in many cultures, domestic violence is viewed as a man’s right, which reduces a woman’s control over her environment. This means she cannot question her husband’s extramarital affairs, cannot negotiate condom use and cannot refuse to have sex (NCASC, 2006). Gender roles have a powerful influence on HIV transmission. In many cultures, men are expected to have many sexual relationships. There is social pressure on them to do so. This increases their risk of becoming infected. Because women often suffer economic inequities, they often need to use sexual exchange as a means of survival. This exposes them to unacceptable risks when they try to negotiate safer sex (for example, rejection, loss of support, and violence). Poor people lack access to information needed to understand and prevent HIV/AIDS. Ignorance of the basic facts makes millions of people worldwide vulnerable to HIV infection. These lower a person’s inhibitions and impair judgment, which may result in risky behaviour. Injecting illicit drugs frequently involves the sharing of needles and injection equipment, increasing the risk of HIV transmission (NCASC, 2006). Religious organizations play a central role in many communities and are an essential part of support networks for people living with HIV/AIDS and their carries. Religious faith often motivates people to provide practical care for people who are sick. This includes volunteering to care for people with HIV/AIDS. Religious faith also encourages people to offer emotional and spiritual comfort, which is a type of counselling. This is especially important when the practical reality is difficult to face because there is little or no access to treatment and the burden of grief in the community is very large (Olley et al., 2006). 2.2.3 Pathology of HIV/AIDS Most people don't feel any difference after they are infected with HIV. In fact, infected people often do not experience symptoms for years. Some people develop flu-like symptoms a few days to a few weeks after being infected, but these symptoms usually go away after some time.

- 44. An HIV-positive person will eventually begin to feel sick. The person might begin to have swollen lymph nodes, weight loss, intermittent fever, infections in the mouth, diarrhea and feel tired for no reason all of the time. Eventually, the virus can infect all the body's organs, including the brain, making it hard for the person to think and remember things (Armirkhanian et al., 2003). When a person's T cell count gets very low, the immune system is so weak that many different diseases and infections by other germs can develop. These can also be life threatening. For example, people with AIDS often develop pneumonia, which causes coughing and breathing problems. Other infections can affect the eyes, the organs of the digestive system, the kidneys, the lungs, and the brain. Some people develop rare verities of cancers of the skin or immune system (Beine, 2003). Most of the children who have HIV got it because their mothers were infected and passed the virus to them before they were born. Babies born with HIV infection may not show any symptoms at first, but the progression of AIDS is often faster in babies than in adults. Doctors need to watch them closely. Kids who have HIV or AIDS learn more slowly than healthy kids and tend to delay walking and talking. HIV-positive people should know the difference between HIV and AIDS. They should understand how people become infected. Some HIV infected people stay healthy for months or years, but can still transmit the virus to others. Some get flu- like symptoms such as fever, headache, sore muscles and joints, stomachache, swollen lymph glands or skin rash. With any unexplained symptoms or possible exposure to HIV, testing should be considered. HIV testing looks for HIV antibodies in the blood, saliva or urine. If tested too early, some HIV infected people may not obtain positive results. For accurate results, testing should be done two to six months after exposure. A positive test result does not mean that a person has AIDS. Depending on HIV symptoms and test results (viral load and T-cell count), a person may need to take ARV medication (Underwood, 2006). 2.3 Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS

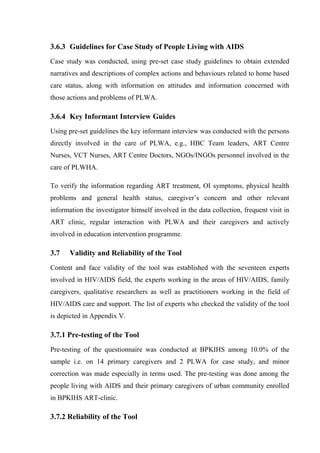

- 45. World AIDS Day has a special place in the history of the AIDS pandemic. Since 1988, 1st December has been a day bringing messages of compassion, hope, solidarity and understanding about AIDS to every country in the world. World AIDS Day emerged from the call by the World Summit of Ministers of Health on Programme for AIDS Prevention in January 1988 to open channels of communication, strengthen the exchange of information and experience, and forge a spirit of social tolerance. Since then, World AIDS Day has received the support of the World Health Assembly, the United Nations system, and governments, churches, communities and individuals around the world. Each year, it is the only international day of coordinated action against AIDS (UNAIDS, 2002). “Stop AIDS: Keep the Promise” is the theme of World AIDS Day 2005. "Keep the Promise" is an appeal to governments and policy makers to ensure that they meet the targets they have agreed to in the fight against HIV and AIDS. Awareness raising activities take place in almost all the countries around the world, often with mass participation; AIDS organizations mobilize and high level government officials speak out. There is broad, non-restrictive participation. Today, World AIDS Day has achieved such a level of recognition worldwide that it is set to remain a primary vehicle for reinforcing AIDS awareness at the international and national level, regardless of the theme or level of United Nations participation. The estimated number of HIV cases is important information for formulating a national strategy on HIV/AIDS and for programme designing, monitoring and evaluation purposes. The National Centre for AIDS and STD Control (NCASC), Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) of Nepal, with the technical support of Family Health International (FHI)/Nepal and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), estimated the number of adult HIV cases in Nepal for the first time in 2003. This estimation exercise was repeated again for the year 2005 by NCASC with technical assistance from FHI/Nepal and USAID. As before, the estimates are derived for four epidemic regions and combined to derive national estimates (NCASC, 2006).