Running head EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS1.docx

- 1. Running head: EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS 1 EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS 2 Perform an external and internal environmental analysis for your Learning Team’s company. Write a summary of about 2,000 words that does the following: · Identifies and analyzes the most important external environmental factor in the remote, industry, and operating environments · Identifies and analyzes the most important internal strengths and weaknesses of your organization: Include an assessment of the organization’s resources. Format your paper consistent with APA guidelines External and Internal Environmental Analysis Your Name: School Name: Date External and Internal Environmental Analysis U.S. Energy Corporation (USEC) provides service in the production and development of natural gas and oil in the United States. Founded in 1966 in Wyoming and focusing on “the development of natural resource assets — acquiring properties on favorable terms, adding value through the application of its expertise in the natural resources sector, and seeking joint

- 2. venture partners to assist in the development of its projects”. USEC is an independent exploration and production company that has large and diverse prospects through North Dakota and Montana as well as Texas and the Gulf of Mexico. Team B will be identifying and analyzing the external environmental factor in the remote, industry, and operating environments in addition to the internal strengths and weaknesses of USEC.Included will be an assessment of the company’s resources. Remote factors USEC economic remote factors can have a huge effect on the company. The market is one of the largest factors because this can affect the prices of natural gas and oil. The demand for natural gas and oil as well as geothermal, and molybdenum are also another factor.USECkeeps constant trends and motoring on these factors because it can affect the production. The company so far has maintained the financial part of the business without outsourcing for capital. Other economic factors are the contracts in developing and mining and the commodity derivative contracts. The commodity derivative contract, also called “economic hedges” objective is to reduce the effect of price changes on a portion of future oil production; achieve more predictable cash flows in an environment of volatile oil and gas prices, and to manage exposure to commodity price risk. The use of these derivative instruments limits the downside risk of adverse price movements. The commodity derivative prices can effect the changes in the market Demand, pipeline capacity constraints, weather, and the economic activities, and other factors. Social Factors The USEC has built a strong culture that has made it possible for the company “to create opportunities which we can then convert into positive return for shareholders”. The company does not deal directly with the consumer but the company does have stockholders and intermediates bonded by contracts to sell

- 3. the company’s products. The company as of 2011 has employed 19 full-time well trained professionals dedicated in following the company’s code of ethics. USECis a company with an excellent cultural environment, and values. The company has very low employee turnover with exceptional work ethics. Political Factors USEC is affected by political factors.As Pearce and Robison, 2011 states “political factors define the legal and regulatory parameters within which firms must operate”. USEC is obligated to follow the rules and regulation of local, state and federal law requirements. Other laws that apply are NEPA, Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972 and the Clean Air Act.The company is follows the tax laws for assets and liabilities, security laws for real estate, and environmental laws for quality and pollution laws. Technological and ecological factor The technological factor involves the technological changes. USEC has adopted all technological changes, including the purchase of new equipment and improving machinery to improve the drilling and the production. The ecological factors are air pollution, land pollution, and water pollution. These factors are extremely important because they can affect the living conditions natural life. The company constructs fully functional water pipelines on sites that dischargein compliance with permit requirements. USEC may generate “solid” and “hazardous” wastes subject to regulation under RCRA and comparable state statutes, although certain mining and oil and natural gas exploration and production wastes currently are exempt from regulation as hazardous wastes under RCRA. Other operations like drilling that releases restrict substances into the environment, USEChas remedial work to mitigate pollution from operations by closing and covering disposal pits,

- 4. and plugging abandoned wells. Industry factors USEC has made a name for itself in the market place with the oil and gas exploration; includingproduction, geothermal energy, and molybdenum mining projects. The gas and oil wells operate along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico and Texas. The entry into the oil market is highly competitive. USEC competes with public and private exploration and development companies. The company also competes with gas and oil operators to acquire acreage positions. The competitors are small to mid-size companies that have in-house petroleum exploration and drilling.Some companies do have the personal resources, technology, and financialsmuch greater than USEC. The elevated barriers to entry consist of resource ownership, government licenses, and a high start-up cost. The oil and gas industry is a monopolist market.“Theoil industry was prone to a natural monopoly because of the rarity of the deposits”. Operating Factors Execution of a business plan for the company requires the ability to generate cash to satisfy planned operating requirements for the next six to eight months.USEC entered into an agreement as a participant with a private entity of two counties in Texas. Under the terms of the agreement, USEC will earn 19.6% net revenue interest in approximately 1,274 net acres to USEC through a cash payment of $1.7 million. The promoted amount will cover USEC's portion of the costs for land, geological, and geophysical work, in addition to all dry hole costs for an initial test well in each of the seven prospects. Upon payout of USEC's initial well costs in each unit, USEC's interest is reduced to 14.7% net revenue interest. Future infill drilling will be on an as needed basis, and USEC's interest will be 14.7% net revenue interest. USEC is incessantly in quest of additional capital through different alternatives, and particularly with respect to procuring

- 5. working capital ample for the development of natural gas and energy projects to cause positive cash flow to sustain operations. USEC continue to pursue numerous opportunities their business as it relates to the oil and gas industry. USEC’s participation with private entities has been mutually favorable demonstrating a $1.6 million, a 24% increase in revenue; produced an OE/D from 13.65 producing wells; received an average of $2.8 million per month from producing wells with an average operating cost of $431,000 per month (excluding work- over costs), and production taxes of $294,000 before non-cash depletion expense, for an average cash flow of $2.1 million per month from oil and gas production. USEC’s objective to generate capital for investors includes the commitment amount for our senior credit facility with Wells Fargo, NA increased from $75 million to $100 million, and the borrowing base increased from $28 million to $30 million and did not have any borrowings under this facility; however, borrowed $5 million to funddrilling programs. The company has $7.8 million in cash and cash equivalents on hand with working capital of $11.8 million. During the quarter ended March 31, 2012 we recorded a net loss after taxes of $381,000 as compared to a net loss after taxes of $2.2 million during the same period of 2011. Currently in 2012, USEC sold an undivided 75% of undeveloped acres in its Yellowstone and SE HR Zavanna leasehold interests for $16.7 million and $1.4 million in reimbursed well costs. The Company retained the remaining 25% interest in the undeveloped acreage and its original working interest and production in ten gross or two point three wells. Internal strength and weakness To improve the quality of decisions and choices by management USEC must identify its strengths that arise from the resources and competencies available.It must also identify its weaknesses

- 6. that limit its capabilities and creating disadvantages related to its competition.The following SWOT analysis identifies the strengths and weaknesses related to the future of USEC. The most important strengthsare assets including property acreage and low liabilities. In the First Quarter of 2012 USEChad combined assets worth 148.22 million and total liabilities worth 21.68 million. This is a huge asset for the company because minimal risk is assumed with obligation for liabilities. The company continues to keep its balance sheet clean by selling acreage at a premium to original cost. Acquiring favorable assets allow the company to reinvest in itself by exploring new technologies and other forms of producing environment friendly efficient energy. In an interview Keith Larson the CEO of USECsaid, “the company is looking forward to continuing to work with Crimson in the Eagle Ford programs to identify the best practices to economically develop the acreage. Reports 2011 Highlights and Selected Financial Results. This is an indication of the value of acreage held by the company as an asset. USEC’s strength also lies in possible future revenues from Uranium properties and the royalties held on Uranium claims. “It currently holds a 4% net profits interest on unpatented mining claims on Rio Tinto’s Jackpot uranium property located on Green Mountain in Wyoming." USEC’s internal weaknesses include drilling operations, equipment, and key personnel. Currently the company does not operate most of its drilling locations and therefore cannot control the timing of exploration and development efforts, associated costs, or the production rate of these non-operational assets. This is challenging for the company because it poses

- 7. uncertainties with timing, selection of suitable technology and the required capital expenditures. The price fluctuation of oil and gas industry can often cause periodic shortages in equipment. This can severely affect the activity levels in many operating regions. Williston Basin says, “These types of shortages can significantly decrease the profit margin, cash flow and operating results or delay the ability to drill those wells and conduct those operations that the company currently has planned and budgeted, causing to miss forecasts and projections.” Equipment is essential to any project and USEC must plan better to secure equipment.It can either buy its own equipment or enter into contract agreements to use the equipment that will give the company access to the equipment regardless of the competition. The last internal weakness of the USECis that it has limited technical staff and executive group. Often the company has to reach out to third party consultants for professional geophysical and geological advice in oil and gas matters. The loss of any key employee can force business operations temporarily immobile and replacements can be difficult because of competitive hiring of experienced personnel in the minerals industry. USEC must invest in employee growth and explore opening its own research department rather than hiring third party consultants. This may help to strengthen employee retention and continually grow a qualified staff of personnel. Assessment of U.S. Energy Corporation resources In general, a company’s resources are all assets, capabilities, competencies, organizational processes, attributes, information, and knowledgeable that is controlled and enabled to conceive and implement strategies designed to improve its efficiency and effectiveness. A firm’s attributes that may be thought of as resources are generally divided into four categories: financial, physical, human, and organizational

- 8. capital. Financial capital is all the different money sources a company uses to implement strategies. USEC is very financially sound as described in the operating factors section. In its current financial situation U.S. Energy Corp. is in a very advantageous position to continue to support its oil and gas exploration and investments into other markets. Physical capital that is any non- human asset-made by humans and used in production. This usually includes all facilities, equipment, access to raw materials, and geographic location with an affluence of drilling ventures and a diverse portfolio of prospects. Human capital includes all the attributes of experience, training, intelligence, leadership, and insight of managers and workers within a corporation. USEC has a wealth of human capital within its organization. The company is led by Keith Larsen, the acting CEO. Keith has over 25 years of experience in the natural resource sector that includes project development in oil and gas and mineral markets. Mark Larsen, COO, Steven Youngbauer, Secretary, and Bryon Mowry, Director of Accounting, round out the rest of the senior management team that has a total of over 106 years of experience within this sector. Organizational capital is a term used to describe the efficiency with which a business or other type of organization can utilize resources in a manner, making it possible to implement and sustain some type of strategy. This process often involves identifying ways to use existing resources in new ways, or to allocate a portion of those resources to a new project without creating hardship for other strategies that must continue to function, the ability to assess and use organizational capital is important to the ongoing growth of the company. USEC has a corporate governance strategymade of several committees that provide oversight and direction for the company. These committees include the Audit Committee, to provide direction

- 9. and review of fiscal matters; the Compensation Committee that reviews and recommends compensation packages for the officers of the company; the Executive Committee, and the Nominating Committee, who considers and recommends who may be suitable to serve as directors. Conclusion USEChas a long-standing reputation as the industry leader with a long-term orientation. Disciplined management, a nationally valued source for gas, oil, energy, and operational excellence in natural resources and environmental cultivating; USEC is poised to take on the challenges of the world energy sources. The magnitude of its reserves, strong technology orientation, and its financial strength gives it a commanding position in the industry. For USEC to extend the competitive advantage, a well-balanced strategy that caters to the short-term and long-term is critical. USEC recent move of focusing on seven projects with a private company is well aligned with its energy outlook and long-term investments in relatively high-growth areas of energy sources. The oil andgas industry is cyclical and its profits are highly correlated to supply and demand dynamics and political stability in major oil producing nations. Nevertheless, improving global economic growth prospects and ever increasing energy demand goes well for the company’s profit outlook. With an nationally diversified business portfolio, the company’s leading oil and gas reserves, envious financial strength and solid

- 10. dividend yields, USEC is one of the best long-term investment plays in the energy sector and integrated oil and as an industry. References 2011 Annual Report. (2011). U. S. Energy Corporation. Retrieved from http://files.shareholder. com/downloads/USEG/1878530569x0x570365/462A4412-DE21- 4707-8C60 783E5B73822F/US_Energy_Corp_2011_Annual_Report.pdf Beattie, A. (2010). A history of U. S. Monopolies. Retrieved from http://www.investopedia.com/ articles/economics/08/hammer-antitrust.asp#axzz1w5KkzVRi Pearce, J. A., II, Robinson, R. B. (2011). Strategic management: Formulation, implementation, and control (12th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. U.S. Energy Corp. Reports 2011 Highlights and Selected Financial Results. (2012). Retrievedfromhttp://investor.usnrg.com/releasedetail.cfm?Relea seID=657392 Working With the Aging: The Case of Francine Francine is a 70-year-old, Irish Catholic female. She worked for 40 years as a librarian in an institution of higher education and retired at age 65. Francine has lived alone for the past year, after her partner, Joan, died of cancer. Joan and Francine had been together for 30 years, and while Francine personally identifies as a lesbian, she never came

- 11. out to her family or to her colleagues. When speaking to all but her closest confidantes, Francine referred to Joan as her “best friend” or her “roommate.” Francine’s bereavement was therefore complicated because she did not feel she could discuss the true nature of her partnership with Joan. She felt that there was little recognition from her family, and even some of her close associates, of the impact and meaning of Joan’s death to Francine. There is a history of alcohol abuse in Francine’s family, and Francine abused alcohol from late adolescence into her mid-30s. However, Francine has been in recovery for several decades. Francine has no known sexual abuse history and no criminal history. Francine sought counseling with me for several reasons, including an ongoing depressed mood, a lack of pleasure or enjoyment in her life, and loneliness and isolation since Joan’s death. She also reported that she had begun to drink again and that while her drinking was not yet at the level it had been earlier in her life, she was concerned that she could return to a dependence upon alcohol. Francine came to counseling with several considerable strengths, including a capacity to form intimate relationships, a successful work history, a history of having maintained her sobriety in the past for many years, as well as insight into the factors that had contributed to her current difficulties. During our initial meetings, Francine stated that her goals were to feel less depressed, to reduce or stop drinking, and to feel less isolated. In order to ensure that no medical issues were contributing to her depression symptoms, I referred Francine to her primary care

- 12. physician for an evaluation. Francine’s physician PRINTED BY: [email protected] Printing is for personal, private use only. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted without publisher's prior permission. Violators will be prosecuted. PRINTED BY: [email protected] Printing is for personal, private use only. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted without publisher's prior permission. Violators will be prosecuted. https://jigsaw.vitalsource.com/api/v0/books/9781624580062/pri nt?from... 1 of 1 10/4/2016 10:47 PM Contributions of Psychological Well-Being and Social Support to an Integrative Model of Subjective Health in Later Adulthood Sophie Guindon & Philippe Cappeliez Published online: 14 January 2010 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 Abstract This study examined the contributions of psychological well-being and social support to an integrative model of subjective health among older adults. Structural equation modeling was used to test the proposed model of subjective health which

- 13. included age, education, physical health problems, functional status, psychological well- being and social support. Partial support for the model was found. Psychological well- being had both a direct effect on subjective health and an indirect effect mediated by physical health problems. Social support had an indirect association with subjective health via its effect on psychological well-being. Functional status had only a weak effect on subjective health. Longitudinal data at a six-year interval revealed the same direct and/ or indirect effects of these variables on subjective health. This study sheds light on how psychological and social resources are linked with subjective health in later adulthood. Keywords Subjective health . Older adults . Psychological well- being . Social support Older age is associated with an increase in chronic health problems and physical disability, yet the majority of older adults evaluate their health in positive terms (e.g. Statistical Report on the Health of Canadians 1999; Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group 2001). Subjective health is of particular interest in gerontological research, as it appears to predict important variables including functional decline (Grand et al. 1988; Idler and Kasl 1995; Kaplan et al. 1993; Mor et al. 1994) and even mortality after other Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 DOI 10.1007/s12126-009-9050-7

- 14. The Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA) was funded by the Seniors’ Independence Research Program, through the National Health Research and Development Program (NHRDP) of Health Canada (Project No. 6606-3954-MC[S]). Additional funding was provided by Pfizer Canada Incorporated through the Medical Research Council/Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of Canada Health Activity Program, the NHRDP (Project No. 6603-1417-302 [R]), Bayer Incorporated, and the British Columbia Health Research Foundation (BCHRF Projects No. 38 [93-2] & No. 34 [96-1]). The CSHA was coordinated through the University of Ottawa and the Division of Aging and Seniors, Health Canada. The authors wish to express their appreciation to all staff across Canada involved in the CSHA. S. Guindon: P. Cappeliez (*) School of Psychology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada e-mail: [email protected] covariant factors including objective indicators of health are taken into account (for reviews, see Benyamini and Idler 1999; Idler and Benyamini 1997). These observations suggest that subjective health encompasses elements that are not necessarily captured by objective measures of health and underlines the relevance of gaining a better understanding of subjective health. In keeping with this objective, it appears important to identify the principal determinants of subjective health, and in particular, those

- 15. variables which may affect subjective health positively in later adulthood. Consistent with traditional biological and Western views of health, models of subjective health have generally focused on physical health and functional status (e.g. Johnson and Wolinsky 1993; Liang 1986). Subjective health in later adulthood is indeed linked to physical health indicators such as number of reported health problems (Pinquart 2001), medications used (Benyamini et al. 2000), as well as functional disability (Bookwala et al. 2003; Lee and Shinkai 2003; Pinquart 2001). Sociodemographic factors have also been included in many studies of the determinants of subjective health. Review of the literature reveals that the relationship between gender and the subjective health of older adults is still unclear (Gonzalez et al. 2002; Henchoz et al. 2008; Saevareid et al. 2007; Prus and Gee 2003). In particular, several studies have found that the predictors of subjective health may vary according to gender (Heikkinen et al. 1997; Leinonen et al. 1999; Prager et al. 1999; Prus and Gee 2003; Rodin and McAvay 1992; Schulz et al. 1994). The effect of age on subjective health also varies from one study to the next. Results of two meta-analyses that included cross-sectional (Roberts 1999) and longitudinal (Pinquart 2001) studies, reveal a slight decrease in subjective health with increasing age, especially among

- 16. adults 80 years and older. However, these results are interpreted as the effect of increasing health problems and functional limitations with age (Pinquart 2001), which suggests that age probably does not exert a direct effect on subjective health, but rather an indirect one through physical health and functional status. This hypothesis has received some empirical support (Orfila et al. 2000). In addition, studies have shown rather consistently that higher education is associated with better subjective health (e.g. Grundy and Sloggett 2003; Murrell and Meeks 2002; Prus and Gee 2003; Von dem Knesebeck et al. 2003; Zimmer and Amornsirisomboon 2001). As Mossey (1995) pointed out, psychological variables can also influence subjective health. She proposed a model of subjective health that includes mental health as predictor of subjective health, alongside physical health, functional status, and sociodemographic variables. This model proposes that sociodemographic variables have a direct effect on subjective health, as well as indirect effects through the three other variables. The model further posits that physical health exerts direct and indirect effects through mental health and functional status, which in turn both have direct effects on subjective health. Finally, in addition to its direct effect on subjective health, mental health is hypothesized to have indirect effects via physical health and functional status. Regrettably research simultaneously testing the

- 17. predictions of Mossey’s model is still lacking. The criticism of tautological reasoning could be leveled against this approach to the determinants of subjective health, as physical and mental health indicators can be expected to share much variance with subjective health. However, closer examination of these constructs and their measurements reveals that they are distinct. Specifically, while more objective indicators of physical health (e.g. health problems checklist or Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 3939 medical antecedents) and functional status (e.g. ability to accomplish various activities of daily living or level of mobility) may indeed influence self- assessment of health, clearly the perception of one’s health transcends this information and indeed is influenced by a variety of personal factors such as mood, self- perception/concept, expectations, and comparisons with others, to name a few. Regarding psychological well-being, typical indicators such as life satisfaction, happiness, self-esteem and perception of control, are much broader and multi-facetted concepts than subjective evaluation of health. At the empirical level also, items referring to perception of physical health in typical measures of psychological well-being constitute only a very small fraction of the dimensions assessed by such measures.

- 18. It is important to note that research on the psychological determinants of subjective health has largely adopted a pathogenic perspective by conceptualizing mental health in terms of level of psychological distress and thus focusing on factors that undermine subjective health. Yet it has been reported that positive indicators of psychological well-being such as life satisfaction (Lee and Shinkai 2003), perception of control (Chipperfield et al. 2004), and self-esteem (Cairney 2000; Starr et al. 2003), are also associated with subjective health. In fact, emerging evidence suggests that positive psychological functioning may represent an important long-term predictor of subjective health (Benyamini et al. 2000). However, how these psychological factors precisely relate to subjective health remains an open question. While psychological well-being could directly influence self- evaluations of health, a growing body of research suggests that objective indicators of physical health can also be positively affected by various dimensions of psychological well-being, including positive affect (Fredrickson and Levenson 1998; Ostir et al. 2001a; Ostir et al. 2004; Ostir et al. 2001b; Xu 2006), perception of control (Chipperfield et al. 2004), and healthy global psychological well-being (Keyes 2005). Notably, experimental research has demonstrated that the induction of positive emotions restored

- 19. cardiovascular physiological activation induced by negative emotions or stress, which suggests that mood can exert a direct effect on the risk of illness (Fredrickson and Levenson 1998). Thus, it appears likely that psychological well-being could indirectly affect subjective health through its effect on objective physical health. Although findings have been inconsistent, there is also research pointing to the relevance of social support. Overall, positive integration within diverse social networks appears to be related to better subjective health (Wu and Rudkin 2000; Zunzunegui et al. 2004), with emotional support seemingly the most beneficial for subjective health (Zunzunegui et al. 2001). The positive effects of social support on subjective health may well be mediated by psychological variables (Landau and Litwin 2001; Okamoto and Tanaka 2004). Despite the above-mentioned evidence, research on subjective health from a salutogenic perspective, focusing on factors that promote health such as positive psychological functioning and social support (Ryff and Singer 1998; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000), has been lacking. Yet, considering the role of these variables could help elucidate how older adults can maintain a favorable subjective health despite an objective decline of physical health. Therefore, the main objective of the present study was to examine how psychological well-

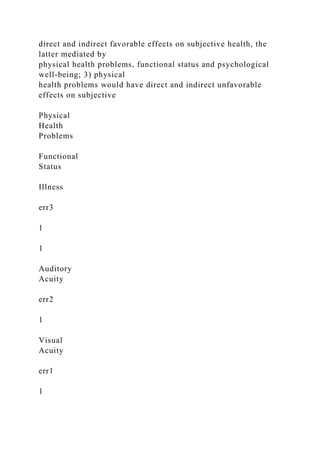

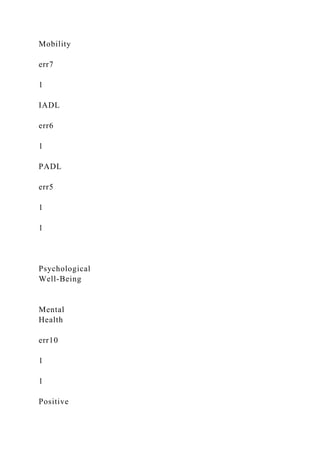

- 20. being and social support relate to subjective health among older adults. These relationships were tested using the framework of an integrative model of subjective health that stems 40 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 from Mossey’s model of subjective health (Mossey 1995). The proposed model incorporates positive indicators of psychological well-being and social support as predictors of subjective health. On the basis of the literature reviewed above, and as Fig. 1 illustrates, the main hypothesis was that psychological well-being, operationalized as general mental health status, life satisfaction and positive psychological functioning, would have a favorable direct effect on subjective health, as well as an indirect effect through mediation by physical health problems and functional status. Given the less consistent relationship between social support and subjective health, it was hypothesized that the effect of social support would be a favorable but indirect one, mediated by psychological well-being. The proposed model further posits the following subsidiary hypotheses : 1) age would have an indirect unfavorable effect on subjective health, mediated by physical health problems and functional status; 2) education would have

- 21. direct and indirect favorable effects on subjective health, the latter mediated by physical health problems, functional status and psychological well-being; 3) physical health problems would have direct and indirect unfavorable effects on subjective Physical Health Problems Functional Status Illness err3 1 1 Auditory Acuity err2 1 Visual Acuity err1 1

- 22. Mobility err7 1 IADL err6 1 PADL err5 1 1 Psychological Well-Being Mental Health err10 1 1 Positive

- 24. Social Support Fig. 1 Proposed integrative model of subjective health Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 4141 health, the latter mediated by functional status and psychological well-being; and 4) better functional status would have direct and indirect favorable effects on subjective health, the latter mediated by psychological well-being. The test of this model was first performed on cross-sectional data obtained from a large representative sample of older adults. The predictive power of the resulting model was further tested using longitudinal data from the same sample. Specifically, it was hypothesized that the final model resulting from the cross- sectional analysis would also significantly predict future subjective health. Since the research literature is equivocal regarding gender differences in subjective health, analyses were performed on men and women separately in order to elucidate potential gender differences. Method Participants Data were obtained from the Canadian Study of Health and

- 25. Aging (CSHA Working Group 1994), a longitudinal investigation comprising a large nationally representa- tive sample of adults over 64 years of age. A randomized sample of older adults was created from government health records in all provinces except Ontario, where enumeration records were used instead. The Yukon and North– West Territories were excluded from the CSHA due to the small number of older adults inhabiting those regions. Data collection for the CSHA was divided into three phases. A total of 9,008 community-dwelling older adults and 1,255 living in institution participated in the first phase (CSHA-1) in 1991–1992. The latter underwent a clinical exam for assessment of their cognitive functioning, while the former completed with a qualified interviewer a standardized interview which included a cognitive screen, the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS; Teng and Chui 1987). Those presenting possible cognitive impairments were further assessed for dementia. Community-dwelling participants who were deemed free of dementia in CSHA-1 were invited to participate in the second phase (CSHA-2) in 1996–1997. Among the 5,703 participants from CSHA-2 (63.3% of original sample), 5,395 lived in the community whereas 308 moved to an institutional setting. Only the community- dwelling sample from the CSHA-2 was retained for the present study, given that all the measures of interest were administered to this sample at that

- 26. time. Participants from the CSHA-2 whose scores on the 3MS suggested possible cognitive problems were excluded from the present study as they were not required to respond to all measures in the interview, resulting in a total of 4,329 participants. Of this sample, only the English-speaking participants were retained to increase sample homogeneity. The resulting sample consisted in 3,599 participants (2,171 women, 1,428 men) aged between 69 and 105 (M=78.58, SD=5.76). Half of the participants were married (50.7%) and 39.8% were widowed. Participants completed an average of 11.39 years of education (range from 0 to 33; SD=3.45) and 49.3% reported an annual household income below $30,000. On average, 4 physical health problems were reported over the past year (range 0 to 13; SD=2.32). From this sample, a total of 2,367 participants (1,471 women, 896 men) responded to the subjective health measure in the CSHA-3, which took place in 2001–2002. The cross-sectional 42 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 analyses in the current study are based on the data from CSHA- 2, and the longitudinal analyses use data collected in CSHA-2 to predict subjective health assessed in CSHA-3. To simplify, CSHA-2 and CSHA-3 data

- 27. are referred to respectively as Time 1 and Time 2 data in the present study. More information on the samples of CSHA-1 and CSHA-2 is available elsewhere (McDowell et al. 2001). Measures Sociodemographic variables They included gender, age, and years of education. Subjective health Subjective health was assessed with the following question: « How would you say your health is these days? (5 = very good, 4 = pretty good, 3 = not too good, 2 = poor, 1 = very poor) ». Use of such a single global question is one of the most frequent manner of measuring self-rated health, and it is considered as a reliable measure of subjective health for older adults. Studies evaluating subjective health with five response choices with older participants have reported good test-retest reliability, using weighted Kappa statistic (in order to account for partial agreement among ordered categories). Indeed, Andresen and colleagues reported a Kappa coefficient of 0.67 for adults aged 65 years and older, over a 2- week interval (Andresen et al. 2003). Crossley and Kennedy (2002) indicated a Kappa coefficient of 0.69 for adults aged 70 and over, for an evaluation performed before and after another set of health related questions. Furthermore, criterion validity for such a measure is supported by the demonstration of significant graded

- 28. relationships with health events in adults of middle and older ages (Wurm et al. 2008). Physical health problems Physical health problems were assessed with four measures. The first comprised a list of 16 health problems common in old age. Participants indicated whether or not they had experienced these problems over the past year, resulting in a cumulative index of reported health problems. A second 4-item measure evaluated reported medical antecedents (i.e. heart operation; artery or neck operation; hip replacement; diabetes); higher scores were indicative of a greater number of antecedents. Given that visual and hearing impairments are relevant to subjective health (Lee et al. 2005), measures of visual and auditory acuity were included, in the form of two questions asking the participants to assess their vision (with glasses or contacts if worn) and hearing (with a hearing aid if worn) using a 5-point response scale (1 = excellent; 2 = good; 3 = fair; 4 = poor; 5 = incapable of hearing/seeing); higher scores reflected poorer auditory and visual acuity. Functional status Functional status was defined as the capacity to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and functional mobility. Questions assessing the capacity to perform ADL were from the Older Americans Resources Survey (Multidimensional functional

- 29. assessment 1978). Both physical ADL (PADL) and instrumental ADL (IADL) were assessed, each with a scale comprising seven items. Participants indicated whether they could perform each activity without help, with help, or if it was impossible for them to perform the activity. The maximum score for each scale was 14, thus 28 for the complete scale, with a higher score reflecting a better functional status. Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 4343 Significantly elevated correlations (tau = .83, r=.89, p<.001) were found between this measure and assessments of functional status by qualified professionals, suggesting very good criterion validity. In addition, a very good inter-rater reliability has been reported for this measure (.87; α=.001) (Fillenbaum and Smyer 1981; George and Fillenbaum 1985). Alpha coefficients of .71 and .78 were respectively found for the PADL and IADL scales among the sample of the present study. Functional mobility was assessed with the Timed Up & Go Test (TUG; Podsiadlo and Richardson 1989, 1991). It measures the amount of time needed for the person to lift from a chair, walk a distance of 3 m, turn, walk back to the chair, and sit. The TUG allows the identification of older adults susceptible to falls with an 87% degree of sensitivity and reliability (Shumway-Cook et al. 2000). Elevated

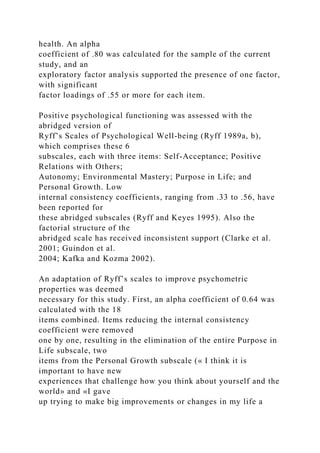

- 30. correlation coefficients (r=−.69 and −.70) were found between the TUG and ADL scales among CSHA participants, suggesting satisfactory construct validity (Rockwood et al. 2000). Psychological well-being Indicators of psychological well-being included life satisfaction, general mental health, and positive psychological functioning. Life statisfaction was assessed with an 11-item adaptation of the Terrible-Delightful Scales (Andrews and Withey 1976), evaluating on a 7-point scale (0 = terrible; 6 = delighted) satisfaction toward: health, family relationships, friendships, housing, finances, residential neighborhood, activities, religion, transportation, life partner, as well as general life satisfaction. A Cronbach alpha coefficient of .81 was calculated with the sample of the present study, indicating very good internal consistency. A similar level of internal consistency has been reported recently (alpha=0.74) (Chappell and Dujela 2008). An exploratory factor analysis with forced one factor solution also indicated significant factor loadings for all items, with a minimum factor loading of .46. The index of general mental health was composed of five items from the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) which assesses anxiety, depression and positive psychological well-being (Ware 1993). Scores were transformed so that a higher score corresponded to better mental

- 31. health. An alpha coefficient of .80 was calculated for the sample of the current study, and an exploratory factor analysis supported the presence of one factor, with significant factor loadings of .55 or more for each item. Positive psychological functioning was assessed with the abridged version of Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-being (Ryff 1989a, b), which comprises these 6 subscales, each with three items: Self-Acceptance; Positive Relations with Others; Autonomy; Environmental Mastery; Purpose in Life; and Personal Growth. Low internal consistency coefficients, ranging from .33 to .56, have been reported for these abridged subscales (Ryff and Keyes 1995). Also the factorial structure of the abridged scale has received inconsistent support (Clarke et al. 2001; Guindon et al. 2004; Kafka and Kozma 2002). An adaptation of Ryff’s scales to improve psychometric properties was deemed necessary for this study. First, an alpha coefficient of 0.64 was calculated with the 18 items combined. Items reducing the internal consistency coefficient were removed one by one, resulting in the elimination of the entire Purpose in Life subscale, two items from the Personal Growth subscale (« I think it is important to have new experiences that challenge how you think about yourself and the world» and «I gave up trying to make big improvements or changes in my life a

- 32. long time ago »), and 44 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 one item from the Autonomy subscale (« I tend to be influenced by people with strong opinions »). This resulted in a 12-item scale with alpha coefficients of 0.67 and 0.71 for male and female participants. Confirmatory factor analyses were completed to test the proposed model structure consisting in one latent variable (i.e. positive psychological functioning) and 12 observed variables (i.e. retained items). As expected, significant error covariances were found between certain items that initially belonged to the same subscale or presented with content overlap. Acceptable fit indices for the model were found, χ2 (48, N=1997)=355.65, p<.001; AGFI=.95; CFI=.91; RMSEA=.057 and χ2 (48, N=1,332)=216.55, p<.001; AGFI=.96; CFI=.92; RMSEA=.051, for women and men). A cross- validation analysis indicated that the model structure was valid, as it did not vary significantly between randomly- selected samples from the original sample. This revised scale mostly excludes dimensions of positive psychological functioning that have been found to be weaker in later adulthood (i.e. Purpose in Life and Personal Growth; Ryff 1989b, 1991, 1995; Ryff and Keyes 1995). The revised scale therefore appears to reunite more cohesive

- 33. indicators of positive psychological functioning at this stage of life (i.e. Self- Acceptance, Positive Relations with Others, Autonomy, Environmental Mastery). Social support The social support measure was based on the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (Ware 1993) and adapted to an older adult population. It includes 6 items evaluating satisfaction toward the perceived amount of instrumental, emotional and informational forms of support, as well as the sense of belonging. The presence of one factor was supported by an exploratory factor analysis, as well as a confirmatory factor analysis (CFI=.97, AGFI=.98, RMSEA=.05 for men; CFI=.98, AGFI=.97 and RMSEA=.06 for women). The internal consistency of this measure was also deemed acceptable given its limited number of items (alpha=0.69). Analytic Procedure Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analyses were completed with AMOS-5 (Arbuckle 2003) to assess the fit of the proposed model. The subjective health measure was treated as continuous, as it is not possible to consider the categorical nature of a variable in analyses performed by this program. The use of categorical variables can lead to inflated χ2 values as well as attenuated correlation coefficients, factor loadings, and standard error estimates mostly when variables are abnormally

- 34. distributed and/or comprise less than five categories (Byrne 2001), which was not the case with the subjective health measure. The Bootstrap Maximum Likelihood procedure was applied to minimize the possible impact of abnormal data distributions on model estimates. Model fit was evaluated with the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The chi-square statistic was not considered due to its hypersensitivity to sample size (Byrne 2001). An acceptable degree of model fit is generally reflected by AGFI and CFI indices equal to or greater than .90, and a RMSEA equal to or less than .08 (Byrne 2001; McDonald and Ho 2002). A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was first completed to confirm that the observed variables included in the model measured their respective latent variables. Given that Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 4545 the fit of the measurement models was judged to be satisfactory, the proposed relationships (i.e. structure) between the different variables included in the model were subsequently tested. In order to satisfy identification requirements of the model, the reciprocal relationships between the Psychological Well- Being variable and Physical Health and Functional Status variables were evaluated

- 35. separately. Cross- validation invariance analyses were subsequently completed to ascertain the statistical equivalence of the model between sub-samples and thus further test its validity. Finally, the models (for men and women samples) supported by previous cross- sectional SEM analyses were tested with subjective health measured six years later (Time 2), taking into account initial subjective health (Time 1). Invariance analyses were again undertaken to further test the validity of the final longitudinal models. Results Preliminary Analyses Missing data analyses revealed that 20 men (1.40%) and 42 women (1.93%) responded to less than 50% of items, and they were excluded from subsequent analyses. This left a total sample of 2,129 female and 1,408 male participants. Almost all participants (95.94% of men and 93.87% of women) responded to 95% or more of the items. Only 1.30% and 2.23% of missing data were found for men and women samples, respectively. The Expectation-Maximization algorithm was used to estimate missing data, as this method is considered superior to analysis of complete data (listwise and pairwise deletion) and mean substitution (Graham et al. 2003; Schafer and Graham 2002). Skewness and kurtosis indices revealed that measures were

- 36. overall fairly normally distributed. Notably, the skew and kurtosis indices for the subjective health measure at Time 1 were, respectively, −.59 and .95 for women and −.70 and 1.76 for men. Similar values were found for subjective health at Time 2 (−.54 and .74 for women; −.61 and 1.23 for men). However, distribution of the three measures of functional status deviated significantly from normal. Transformations were therefore applied to improve distribution of these measures and the Bootstrap procedure was used to estimate all parameters in subsequent SEM analyses. The latter procedure is considered effective in reducing the influence of abnormal data distributions in large samples (Byrne 2001). Scatter plots suggested satisfactory linearity. Multicollinerarity analyses revealed an absence of correlations above .90 between variables (see Tables 1 and 2), as well as tolerance indices superior to 10% and variance inflation factor ratios inferior to 10 for each variable, which indicates that multicollinerarity was not present (Kline 1998). Multivariate outliers were excluded from further analyses, resulting in a final sample of 2,022 female and 1,336 male participants. From this sample, 1,426 female and 868 male participants evaluated their subjective health in CSHA-3 and were thus included in the longitudinal analyses. Cross-Sectional Test of the Integrative Model Results of the SEM analyses revealed an acceptable degree of

- 37. fit for the proposed model of subjective health for both women and men (respectively: AGFI=.95; 46 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 T a b le 1 B iv ar ia te co rr el at io n s b et w ee n o b se rv

- 61. .0 5 . * * p < .0 1 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 4747 T a b le 2 B iv ar ia te co rr el at io n s b et w

- 84. v it ie s o f d ai ly li v in g * p < .0 5 . * * p < .0 1 48 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 CFI=.93; RMSEA=.057 and AGFI=.96; CFI=.92; RMSEA=.047). Estimates for the reciprocal relationship between Psychological Well-Being and Functional Status

- 85. were however inadmissible and removed from the model. Other non-significant paths were also deleted from the model, with the exception of the path Functional Status → Subjective Health which was statistically non-significant for men yet retained due to its theoretical significance. Modification indices suggested a possible relationship between Age and Subjective Health and this path was added to the model. Post hoc analyses were completed following the above-mentioned modifications to the model and results suggested a slight improvement in model fit for women and men (respectively: AGFI=.95; CFI=.94; RMSEA=.052 and AGFI=.96; CFI=.92; RMSEA=.045). Cross-validation analyses of the modified models revealed that their structure did not significantly vary from one sample to the next, which strongly a Fig. 2 a Final model of subjective health for women (Time 1). b Final model of subjective health for men (Time 1) Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 4949 supported their validity. Final models of subjective health for women and men are respectively presented in Fig. 2a and b. In sum, hypothesized relationships in the proposed model of

- 86. subjective health were partially supported. To reiterate, the main hypotheses were that psychological well-being would have a direct effect on subjective health, as well as an indirect one through physical health and functional status, and that social support would have an indirect effect on subjective health via psychological well- being. As predicted, for both women and men respectively, psychological well-being exerted direct (b=.16, p<.001; b=.13, p<.01) and indirect (b=.35, p<.001; b=.31, p<.001) effects on subjective health, resulting in considerable total effects (b=.51, p<.001; b=.44, p<.001). While psychological well-being was associated with less physical health problems (b=−.62, p<.001 for women; b=−.57, p<.001 for men), no relationship was found with functional status, suggesting that the indirect effects occurred through physical health exclusively. As hypothesized, social support also b Life Satisfaction Fig. 2 (continued) 50 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60

- 87. had indirect effects on subjective health (b=.23, p<.001 for women; b=.16, p<.001 for men) through its direct positive effect on the psychological well-being of both women and men (b=.45, p<.001; b=.37, p<.001 respectively). Furthermore, age was associated with a greater number of physical health problems (b=.32, p<.001 for women; b=.17, p<.001 for men) and a poorer functional status (b=−.30, p<.001 for women; b=−.27, p<.001 for men). Higher education was associated with fewer physical health problems for both sexes (b=−.08, p<.01; b=−.11, p<.001 for women and men respectively), whereas it predicted better psychological well-being in women only (b=.16, p<.001). Not surprisingly, physical health problems were associated with poorer subjective health (b=−.52, p<.001 for women; b=−.50, p<.001 for men) and poorer functional status (b=−.54, p<.001 for women; b=−.50, p<.001 for men). Better functional status was associated with better subjective health for both sexes (b=.09), yet achieved a minimal degree of statistical significance (p<.05) in women only. The total explained variance of subjective health reached 43% for women and 38% for men. Contrary to expectations, older age was directly associated with better subjective health (b=.18, p<.001; b=.10, p<.001 for women and men respectively), whereas education was not significantly associated with subjective health for neither sexes, nor

- 88. with psychological well-being and functional status for men. A very weak negative association was found between women’s education and functional status (b=−.07, p<.01). Indirect positive effects were found between women’s education and subjective health (b=.12, p<.001). Results suggested a unidirectional (as opposed to reciprocal) relationship between psychological well-being and physical health for both sexes. Specifically, the effect of psychological well-being on physical health was significant, but not the reverse. Finally, as previously mentioned, results suggested an absence of relationship between psychological well-being and functional status. Longitudinal Test of the Proposed Model Results of the longitudinal analyses suggested an appropriate model fit for both women and men (respectively AGFI=.95; CFI=.94; RMSEA=.048 and AGFI=.95; CFI=.91; RMSEA=.045). Certain non significant path coefficients lead to the deletion of corresponding links, and post hoc analyses again suggested an acceptable model fit (AGFI=.95; CFI=.94; RMSEA=.048 and AGFI=.95; CFI=.91; RMSEA=.044 for women and men respectively). Validity of these models was also supported by cross- validation analyses, which suggested that their structure did not vary significantly from one sub-sample to another. Final models of subjective health at Time 2 for women and men are presented in Fig. 3a and b respectively.

- 89. As predicted, subjective health measured at Time 1 was significantly associated with subjective health at Time 2 (b=.29, p<.001 for women; b=.23, p<.01 for men). For men, psychological well-being had both significant direct (b=.15, p<.01) and indirect effects on subjective health at Time 2, with total effects rising significantly (b=.34, p<.001). While the direct effect of psychological well- being on subjective health at Time 2 was not significant for women, significant indirect effects were found (b=.33, p<.001). Social support also continued to have a small indirect positive effect on subjective health at Time 2 (b=.15, p<.01 for women; b=.14, p<.01 for men). A greater number of physical health problems had both direct (b=−.30, Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 5151 p<.001 for women; b=−.19, p<.01 for men) and indirect negative effects on subjective health at Time 2, resulting in significantly elevated total effects (b=−.46, p<.001 for women; b=−.30, p<.001 for men). The effect of functional status on both women and men’s subjective health at Time 2 was not significant. Contrary to expectation, age for both genders and psychological well-being for women did not have significant direct effects on subjective health across time. The total explained

- 90. variance of subjective health at Time 2 was 28% for women and 21% for men. Discussion The primary aim of the present study was to examine the contributions of psychological well-being and social support to an integrative model of subjective health in older adults, concurrently and over time. Overall, both cross-sectional and longitudinal SEM results support the proposed integrative model of subjective health, as suggested by adequate model fit indices and significant variable .50.86.84 .59.42.55 .60 .60 .45 .58 .52 .59 .78 .96 .72 -.08 .16 .45

- 91. .26 -.08 -.62-.27 -.52 -.51 .16 .14 .06 .71 .38.40 .19 -.64 .76.67 .63 .64 .74 .29 -.30 .18 Psychological Well-Being Mental Health

- 93. T1 Subjective Health T2 a Fig. 3 a Final model of subjective health for women (Time 2). b Final model of subjective health for men (Time 2) 52 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 interrelationships. It is remarkable that the contributions of the different variables in the model were overall very similar in men and women. This contrasts with results of other studies that found gender differences in the predictors of subjective health (e.g. Gonzalez et al. 2002; Prus and Gee 2003). Results provide strong support for the main hypothesis that psychological well- being affects subjective health directly and indirectly (although only indirect effects were observed for women at Time 2). The direct effect of psychological well-being on subjective health may reflect the influence of psychological well-being on memory and other cognitive processes that may be involved in the evaluation of health, such as downward social comparisons (Henchoz et al.

- 94. 2008; Jylhä 1994; Kaplan and Baron-Epel 2003; Krause and Jay 1994; Suls et al. 1991), which refer to the tendency to maintain a positive perception of one’s health by comparing oneself to others in poorer health. As Wurm and her colleagues recently pointed out (Wurm et al. 2008), a positive view of ageing affects subjective health and life satisfaction even in the face of serious health problems, and thus represents a psychological resource that fosters resilience. b .68 .60 .53 .70 .84 .88 .49 .95 .81 .70 .85 .55 .79.67 .84 Fig. 3 (continued) Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 5353 The finding of an indirect effect of psychological well-being on subjective health via physical health finds an echo in emerging evidence showing how physical health can be positively affected by various dimensions of

- 95. psychological well-being including positive affect (Fredrickson and Levenson 1998; Ostir et al. 2001a; Ostir et al. 2004; Ostir et al. 2001b; Xu 2006), optimism (Kubzansky et al. 2001; Reed et al. 1999; Segerstrom et al. 1998), and perception of control (Chipperfield et al. 2004). As predicted, greater satisfaction with available social support had direct and indirect positive effects on psychological well-being and subjective health, respectively. These effects were found in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. It should be noted however that the indirect effects of social support on subjective health, although significant, were small. Some studies that distinguished between emotional and instrumental support have reported that availability of emotional support was associated with better subjective health, whereas greater instrumental support was associated with poorer subjective health (Liu et al. 1995; Zunzunegui et al. 2001). It is therefore possible that larger effects could be found for emotional support specifically. This hypothesis could not be tested in the present study since these two types of support were not distinguished in the measure of social support used. A more detailed understanding of the effects of social support on subjective health might be achieved with the use of distinct measures of these different forms of social support. Not surprisingly, physical health problems were significantly

- 96. associated with subjective health and continued to have a significant effect at Time 2, both directly and indirectly through subjective health measured at Time 1. A surprising result was the lack of effect of physical health problems on psychological well-being for both sexes. Several studies have shown that psychological (or subjective) well-being tends to remain relatively stable and minimally affected by life events in the long term (DeNeve and Cooper 1998; Eid and Diener 2003; Stones et al. 1995; Suh et al. 1996). This stability may be rooted in personality (Duberstein et al. 2003; Suh et al. 1996) or genetic predispositions (Nes et al. 2006). The limited effect of life events on psychological well-being may also reflect the capacity of human beings to adapt to major challenges such as health problems. As expected, age had an unfavorable effect on physical health problems and functional status. Consistent with results of other studies (Hays et al. 1996; Idler 1993; Johnson and Wolinsky 1993; Landau and Litwin 2001; Lee and Shinkai 2003; Mulsant et al. 1997), a small yet significant relationship was found between older age and better subjective health at Time 1. This finding should however be interpreted with caution, as results were inconsistent in the longitudinal test. Other hypothesized links between certain variables of the model were not

- 97. significant. For instance, education appeared to be associated with greater psychological well-being and better subjective health, but only for women. Results also suggested that functional status had a minimal effect on subjective health for both sexes, which is congruent with results of other studies (Nybo et al. 2001; Stump et al. 1997). It may be that older adults expect a certain degree of physical limitations at this stage of life and thus evaluate their health based on this expectation rather than that of an “ideal” or “perfect” health (Nybo et al. 2001). Although a substantial amount of subjective health’s variance was explained by the final model, a certain amount of variance was left unexplained. Other variables excluded from the proposed model may also contribute to explain subjective health 54 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 in later life, such as potential risk factors like pain, psychological distress, and life stressors. On the other hand, other protective factors could also be considered, such as positive coping strategies, healthy lifestyle, positive affect, personality traits (e.g. optimism; sociability), and favorable cognitive processes such as downward social comparisons and positive illusions. Some limitations of the present study need to be acknowledged.

- 98. A major dis- advantage of secondary data analyses consists in the imposed selection of measures. Findings of this study are limited by the conceptual and methodological restrictions of some of its measures. For instance, the evaluation of psychological well-being included a measure of general mental health which contained questions related to depression and anxiety that are indeed more indicative of psychological distress than well-being. Furthermore, Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-being and the social support scales were adaptations of the original scales. Measures of physical health and functional status can also be criticized for being based on self-report, and thus susceptible to under- or over-reporting biases. While measurement of subjective health with a single item can also be considered an issue, there is extensive evidence to support its use (see above description of this measure). Although the investigation was rendered more rigorous with the adoption of SEM as an advanced method of analysis, the analyses remain correlational in nature, and thus cannot truly establish causal relationships between variables (Kline 1998). Nonetheless, findings from the longitudinal analyses provide some tentative support for such type of relationship between the variables in the proposed model and subjective health. Finally, it should be recalled that participants of the present study resided in the community, and did not present with significant cognitive impairments. Therefore, results may not be

- 99. generalizable to older adults with differing characteristics, such as individuals with lower autonomy. In conclusion, results of this study emphasize the determining role of psycho- logical well-being, in terms of good mental health, satisfaction with life and positive psychological functioning, for older adults’ perceptions of their health. The final model illustrates how psychological well-being conceived in this manner can influence subjective health, both directly and indirectly through its favorable effect on physical health. Considering the predictive power of subjective health on other important outcomes such as functional decline and mortality, implications of these results are important. At a theoretical level, they confirm the validity of integrative or holistic models of subjective health, such as those proposed by Mossey (1995) and in the present study. Furthermore, while existing research has mainly focused on the negative effects of psychological distress on subjective health, this study supports the relevance of studying protective psychological resources that may promote better subjective health in later adulthood. This line of investigation could also help elucidate the reason many older adults rate their health positively even when faced with physical health problems. At a clinical level, the results point to the need to promote greater psychological well-

- 100. being in order to improve subjective health. Various types of interventions could be considered. In particular, findings of this study suggest that social support may have a significant effect on psychological well-being, and a resulting indirect effect on subjective health. Clinicians working with older adults should thus be aware of the possible needs for social support among their clients and provide referrals to appropriate community resources for those with limited support. Furthermore, strategies aiming to Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 5555 achieve greater psychological well-being without requiring professional assistance have been described in the literature (e.g. Fredrickson and Levenson 1998; Seligman et al. 2005), and could potentially also have positive effects on subjective health in the later stages of life. Clinical implications of this study incite the development of social policies that would facilitate older adults’ access to life conditions and resources that are likely to promote more optimal levels of psychological well- being and, in turn, better subjective health and associated outcomes. References Andresen, E. M., Catlin, T. K., Wyrwich, K. W., & Jackson- Thompson, J. (2003). Retest reliability of surveillance questions on health related quality of life. Journal

- 101. of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 339–343. Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. R. (1976). Social indicators of well-being. New York: Plenum. Arbuckle, J. L. (2003). Amos 5.0 (Computer Software). Chicago, IL: SmallWaters Corp. Benyamini, Y., & Idler, E. L. (1999). Community studies reporting association between self-rated health and mortality: additional studies, 1995 to 1998. Research on Aging, 21(3), 392–401. Benyamini, Y., Idler, E. L., Leventhal, H., & Leventhal, E. A. (2000). Positive affect and function as influences on self-assessments of health: expanding our view beyond illness and disability. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 55B, P107–P116. Bookwala, J., Harralson, T. L., & Parmelee, P. A. (2003). Effects of pain on functioning and well-being in older adults with osteoarthritis of the knee. Psychology and Aging, 18, 844–850. Byrne, M. B. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New Jersey: Erlbaum. Cairney, J. (2000). Socio-economic status and self-rated health among older Canadians. Canadian Journal on Aging, 19, 456–478. Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group. (1994). Canadian study of health and aging: study methods and prevalence of dementia. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 150, 899–913.

- 102. Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group. (2001). Disability and frailty among elderly Canadians: a comparison of six surveys. International Psychogeriatrics, 13(Suppl.1), 159–167. Chappell, N. L., & Dujela, C. (2008). Caregiving: Predicting at- risk status. Canadian Journal on Aging, 27(2), 169–179. Chipperfield, J. G., Campbell, D. W., & Perry, R. P. (2004). Stability in perceived control: implications for health among very old community-dwelling adults. Journal of Aging & Health, 16, 116–147. Clarke, P. J., Marshall, V. W., Ryff, C. D., & Wheaton, B. (2001). Measuring psychological well-being in the Canadian study of health and aging. International Psychogeriatrics, 13(Suppl. 1), 79–90. Crossley, T. F., & Kennedy, S. (2002). The reliability of self- assessed health status. Journal of Health Economics, 21, 643–658. DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: a meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197–229. Duberstein, P. R., Soerensen, S., Lyness, J. M., King, D. A., Conwell, Y., Seidlitz, L., et al. (2003). Personality is associated with perceived health and functional status in older primary care patients. Psychology & Aging, 18, 25–37. Eid, M., & Diener, E. (2003). Global judgments of subjective well-being: situational variability and long-

- 103. term stability. Social Indicators Research, 65, 245–277. Fillenbaum, G. G., & Smyer, M. A. (1981). The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. Journal of Gerontology, 36, 428–434. Fredrickson, B. L., & Levenson, R. W. (1998). Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 12, 191–220. George, L. K., & Fillenbaum, G. G. (1985). OARS methodology: a decade of experience in geriatric assessment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 33, 607–615. Gonzalez, J. S., Chapman, G. B., & Leventhal, H. (2002). Gender differences in the factors that affect self- assessments of health. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 7, 133–155. 56 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 Graham, J. W., Cumsille, P. E., & Elek-Fisk, E. (2003). Methods for handling missing data. In J. A. Schinka & W. F. Velicer (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Research methods in psychology, Vol. 2 (pp. 87–114). New York: Wiley. Grand, A., Grosclaude, P., Bocquet, P., Pous, J., & Albarede, J. L. (1988). Predictive value of life events, psychological factors and self-rated health on disability in an elderly rural French population. Social

- 104. Science & Medicine, 27(12), 1337–1342. Grundy, E., & Sloggett, A. (2003). Health inequalities in the older population: the role of personal capital, social resources and socio-economic circumstances. Social Science & Medicine, 56(5), 935– 947. Guindon, S., O’Rourke, N., & Cappeliez, P. (2004). Factor structure and invariance of responses by older men and women to an abridged version of the Ryff scale of psychological well-being. Journal of Mental Health and Aging, 10, 301–310. Hays, J. C., Schoenfeld, D. E., & Blazer, D. G. (1996). Determinants of poor self-rated health in late life. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 4, 188–196. Heikkinen, E., Leinonen, R., Berg, S., Schroll, M., & Steen, B. (1997). Levels and associates of self-rated health among 75-year-old people living in three Nordic localities. In E. Heikkinen, S. Berg, M. Schroll, B. Steen, & A. Viidik (Eds.), Functional status, health and aging: The NORA study. Facts, research and intervention in geriatrics (pp. 121–148). Paris: Serdi Publisher. Henchoz, K., Cavalli, S., & Girardin, M. (2008). Health perception and health status in advanced old age: a paradox of association. Journal of Aging Studies, 22, 282– 290. Idler, E. L. (1993). Age differences in self-assessments of health: age changes, cohort differences, or survivorship? Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 48, S289–S300.

- 105. Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21–37. Idler, E. L., & Kasl, S. (1995). Self-ratings of health: do they also predict change in functional ability? Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 50(6), S344–S353. Johnson, R. J., & Wolinsky, F. D. (1993). The structure of health status among older adults: disease, disability, functional limitation, and perceived health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34, 105–121. Jylhä, M. (1994). Self-rated health revisited: exploring survey interview episodes with elderly respondents. Social Science & Medicine, 39, 983–990. Kafka, G. J., & Kozma, A. (2002). The construct validity of Ryff’s scales of psychological well-being (SPWB) and their relationship to measures of subjective well- being. Social Indicators Research, 57, 171–190. Kaplan, G., & Baron-Epel, O. (2003). What lies behind the subjective evaluation of health status? Social Science & Medicine, 56, 1669–1676. Kaplan, G. A., Strawbridge, W. J., Camacho, T., & Cohen, R. D. (1993). Factors associated with change in physical functioning in the elderly: a 6-year prospective study. Journal of Aging and Health, 5, 40–53. Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Chronic physical conditions and aging: is mental health a potential protective

- 106. factor? Ageing International, 30, 88–104. Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford. Krause, N. M., & Jay, G. M. (1994). What do global self-rated health items measure? Medical Care, 32, 930–942. Kubzansky, L. D., Sparrow, D., Vokonas, P., & Kawachi, I. (2001). Is the glass half empty or half full? A prospective study of optimism and coronary heart disease in the normative aging study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63, 910–916. Landau, R., & Litwin, H. (2001). Subjective well-being among the old-old: the role of health, personality and social support. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 52, 265–280. Lee, Y., & Shinkai, S. (2003). A comparison of correlates of self-rated health and functional disability of older persons in the Far East: Japan and Korea. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 37, 63–76. Lee, D. J., Lam, B. L., Gomez-Martin, O., & Caban, A. J. (2005). Concurrent hearing and visual impairment and morbidity in community-residing adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 17, 531–546. Leinonen, R., Heikkinen, E., & Jylhä, M. (1999). A path analysis model of self rated health among older people. Aging in Clinical and Experimental Research, 11(4), 209–220. Liang, J. (1986). Self-reported physical health among aged

- 107. adults. Journal of Gerontology, 41, 248–260. Liu, X., Liang, J., & Gu, S. (1995). Flows of social support and health status among older persons in China. Social Science & Medicine, 41, 1175–1184. McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M.-H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7, 64–82. Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60 5757 McDowell, I., Aylesworth, R., Stewart, M., Hill, G., & Lindsay, J. (2001). Study sampling in the Canadian study of health and aging. International Psychogeriatrics, 13(Suppl. 1), 19–28. Mor, V., Wilcox, V., Rakowski, W., & Hiris, J. (1994). Functional transitions among the elderly: patterns, predictors, and related hospital use. American Journal of Public Health, 84(8), 1274–1280. Mossey, J. M. (1995). Importance of self-perceptions for health status among older persons. In M. Gatz (Ed.), Emerging issues in mental health and aging (pp. 124– 162). Washington: American Psychological Association. Mulsant, B. H., Ganguli, M., & Seaberg, E. C. (1997). The relationship between self-rated health and depressive symptoms in an epidemiological sample of community-dwelling older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 45, 954–958.

- 108. Multidimensional functional assessment: The OARS methodology, a manual (2nd ed.) Centre for the Study of Aging & Human Development, Duke University, Durham, NC, 1978. Murrell, S. A., & Meeks, S. (2002). Psychological, economic, and social mediators of the education-health relationship in older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 14(4), 527–550. Nes, R. B., Roysamb, E., Tambs, K., Harris, J. R., & Reichborn- Kjennerud, T. (2006). Subjective well- being: genetic and environmental contributions to stability and change. Psychological Medicine, 36, 1033–1042. Nybo, H., Gaist, D., Jeune, B., McGue, M., Vaupel, J. W., & Christensen, K. (2001). Functional status and self-rated health in 2, 262 nonagenarians: the Danish 1905 Cohort Survey. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 49(5), 601–609. Okamoto, K., & Tanaka, Y. (2004). Gender differences in the relationship between social support and subjective health among elderly persons in Japan. Preventive Medicine, 38(3), 318–322. Orfila, F., Ferrer, M., Lamarca, R., & Alonso, J. (2000). Evolution of self-rated health status in the elderly: cross-sectional vs. longitudinal estimates. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(6), 563–570. Ostir, G. V., Markides, K. S., Peek, M. K., & Goodwin, J. S. (2001a). The association between emotional well-being and the incidence of stroke in older adults. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63, 210–215.

- 109. Ostir, G. V., Peek, M. K., Markides, K. S., & Goodwin, J. S. (2001b). The association of emotional well- being and future risk of myocardial infarction in older adults. Primary Psychiatry, 8, 34–38. Ostir, G. V., Ottenbacher, K. J., & Markides, K. S. (2004). Onset of frailty in older adults and the protective role of positive affect. Psychology and Aging, 19, 402–408. Pinquart, M. (2001). Correlates of subjective health in older adults: a meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 16, 414–426. Podsiadlo, D., & Richardson, S. (1989). The timed “Up and Go” test. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 67, 387–389. Podsiadlo, D., & Richardson, S. (1991). The timed “Up and Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 39, 142–148. Prager, E., Walter-Ginzburg, A., Blumstein, T., & Modan, B. (1999). Gender differences in positive and negative self-assessments of health status in a national epidemiological study of Israeli aged. Journal of Women & Aging, 11(4), 21–41. Prus, S. G., & Gee, E. (2003). Gender differences in the influence of economic, lifestyle, and psychosocial factors on later-life health. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 94, 306–309. Reed, G. M., Kemeny, M. E., Taylor, S. E., & Visscher, B. R.

- 110. (1999). Negative HIV-specific expectancies and AIDS-related bereavement as predictors of symptom onset in asymptomatic HIV-positive gay men. Health Psychology, 18, 354–363. Roberts, G. (1999). Age effects and health appraisals: a meta- analysis. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 54B(1), S24–S30. Rockwood, K., Awalt, E., Carver, D., & MacKnight, C. (2000). Feasibility and measurement properties of the functional reach and the timed up and go tests in the Canadian study of health and aging. Journals of Gerontology: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences, 55, M70–M73. Rodin, J., & McAvay, G. (1992). Determinants of change in perceived health in a longitudinal study of older adults. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 47(6), 373–P384. Ryff, C. D. (1989a). Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: new directions in quest of successful ageing. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12, 35–55. Ryff, C. D. (1989b). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well- being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069– 1081. Ryff, C. D. (1991). Possible selves in adulthood and old age: a tale of shifting horizons. Psychology and Aging, 6, 286–295. 58 Ageing Int (2010) 35:38–60