Running Head Felony Disenfranchisement Laws A form of Racial Dis.docx

- 1. Running Head: Felony Disenfranchisement Laws: A form of Racial Discrimination against African Americans 39 Running Head: Felony Disenfranchisement Laws: A form of Racial Discrimination against African Americans Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………… ……………………..pg.4 Problem Formulation………………………………………………………… ……………..pg.5

- 2. Introduction………………………………………………………… ……………………….pg.5 Problem Statement…………………………………………………………… ……………..pg.6 Research Question……………………………………………………………… …………...pg.6 Independent/Dependent Variable…………………………………………………………...pg. 7 Literature Review……………………………………………………………… …………....pg.7 Research Design………………………………………………………………… …………..pg.16 Methodology………………………………………………………… ……………………...pg.16 Sample Population…………………………………………………………… ……………..pg.17 Instrument…………………………………………………………… ……………………...pg.17 Reliability and Validity……………………………………………………………… ……..pg.18 Data Analysis and Findings……………………………………………………………… …………………….pg.18 Introduction………………………………………………………… ………………………..pg.19 Demographics……………………………………………………… ………………………..pg.19 Tables………………………………………………………………… ……………………...pg.21

- 3. Conclusion…………………………………………………………… ………………………pg.22 References…………………………………………………………… ………………………pg.23 Appendix……………………………………………………………… ……………………pg.26 Code Book………………………………………………………………… ………………..pg.27 Abstract This paper addresses the controversial topic of convicted criminal’s fundamental rights to vote due to felony disenfranchisement laws. America being the land of the free one would assume everyone could exercise his or her right to vote no matter the circumstances of criminal status or history. The study will clearly dissect and uncover reasonable truth regarding felony disenfranchisement laws and their possible racial discriminative attribute; the following are the objectives

- 4. that this study sets out to achieve. To establish the relationship between felony disenfranchisement laws and racial discrimination. To determine whether the felony disenfranchisement laws should be repealed or amended they are subdivided into general objective and specific objectives. The disenfranchisement laws infringe upon convicted minorities more so than convicted whites to racially discriminate against a group of people. The mass incarceration of minorities is directly affected by the disenfranchisement laws preventing them to vote. Exploratory study uses quantitative data to emphasize the political marginalization of African Americans of Felony disenfranchisement laws and how they may be racially discriminatory against African Americans. Problem Formulation Introduction The suspension of individual’s voting rights upon conviction is quite controversial as it appears to violate the fundamental right to vote. However, the most contentious issue arises when the felony disenfranchisement laws appear to discriminate against racial minorities. Numerous cases have been filed and heard regarding racial discrimination by the felony disenfranchisement laws and in almost all the cases, the plaintiff lost the case (Manza & Uggen, 2008). Felon disenfranchisement laws disproportionately affect ethnic minority communities on a national level. A higher rate of incarceration among the black and Latino populations leads directly to higher disenfranchisement rates (Isler, 2000).

- 5. Nationwide, over 13 percent of black adult males are denied the right to vote, and black men make up 36 percent of the total disenfranchised population. In other words, although black people make up only 13.5 percent of the total U.S. population, more than one third of disenfranchised Americans are black (Cutting, 2016). Nationwide police profiling and over-sentencing of members of minority populations negatively influences communities that already live in poor conditions as a result of discriminatory legislation, such as districting and strict public. Cheryl Wertz of the New Immigrant Community Empowerment organization and the Unlock the Block coalition observed, “A collection of decisions are made by a collection of people without a very good idea of education and poverty.” Prisoner disenfranchisement that occurs as a result of over-sentencing relieves politicians of constituent pressure to address the needs of this largely poor, uneducated, minority population (Ini, 2006). Profiling and over-sentencing, allows inequity to make its way into the criminal justice system, whose policies act as powerful tools to keep minority communities in a perpetual state of poverty and disempowerment. Ron Hayduk, a Political Science professor at Borough of Manhattan Community College and former social worker, characterized the racial inequalities of disenfranchisement law in the following manner: "mass incarceration of minorities is definitely mean-spirited in content and effect." Research Question Are felony disenfranchisement laws a form of racial discrimination against African Americans? Is there any correlation between felony disenfranchisement laws and racial discrimination? Have felony disenfranchisement laws been used to discriminate citizens on racial grounds? Should the felony disenfranchisement laws be repealed, amended or upheld? The purpose of this paper is to show how felony disenfranchisement laws are racially discriminative, how they single out people of color more and how they have little to no effect on whites.

- 6. These felony laws infringe upon the fundamental constitutional rights and should be repealed. This paper focuses on the most fundamental democratic right: the right to vote. What does disenfranchisement mean for some groups? And what does our willingness to disenfranchise people mean about American democracy? Despite public opinion in favor of re-enfranchising ex-felons, legislation is slow to act. Both disenfranchisement and the social structures that perpetuate discrimination must be challenged in order to make the United States a truly democratic country. This research will be conducted with scholastic journals, interviews, surveys, and data from Rust College and University of Memphis students. The surveys will consist of 20 questions that are neutral to all races. Operational Definition Felony disenfranchisement laws: these are laws that nullify the right to vote of an individual convicted of a criminal offence with some states applying the laws to all crimes while other states apply them to capital offences. Racial discrimination: the unfair treatment or distribution of benefits to individuals based on their skin color and origin. Minority Races: These are any non-white races residing in the USA and include African- Americans, American-Indians, Native-Hawaiians, Asians, Hispanic among others. Independent/Dependent Variable The independent variable is Felony disenfranchisement laws; and the dependent variable is racial discriminate against Americans. Other variables that are involved deal with percentage of prison population, race, rights restored by state and percentage of the country’s total population. Literature Review Previous studies conducted on felony disenfranchisement and racial discrimination approached the issue both qualitatively and quantitatively. Qualitative approach has made the constitution the center of the study whereby, loopholes and

- 7. conflicts that arise from disenfranchisement laws have been the basis of the study. An example of a case that resulted to public outcry is Richardson vs. Ramirez (1974) case heard by the US Supreme Court. This was a case filed in protest to the restoration of the individual voting rights upon completion of sentence. It was argued that the state of California violated section one of the 14th amendment that guarantees equal protection by the law for all people. The state of California, like many other states base restoration of voting rights upon payment restitution and legal fines. According to these studies, this is a form of discrimination on grounds of wealth status. It is argued that this in actual sense is a racial discrimination owing to the fact that the white population is wealthier than the minority races. The study further states that restoration of voting rights based on payment of fines violates the 24th Amendment to the US constitution that states that no individual should denied voting rights for failure to pay any form of taxes, (Marc, 2006). Another public outcry regarding felony disenfranchisement is with regard to what is known as “drug-war weapon”. Studies indicate that felony disenfranchisement laws relating to drug crimes bar individuals forever from voting. The study that cited this as a proof for racial discrimination by disenfranchisement laws indicated that about one million non-violent ex-convicts who are neither on parole nor probation, majority being African Americans, are permanently barred from voting, (Jeff, Christopher, McKnight, 2006). The above claims were supported by statistics obtained from the justice system regarding prisoner demographic figures. There has been public outcry regarding racial disparities when it comes to number of arrests, prosecution and the eventual conviction. The studies indicate that out of the arrests made, the percentage prosecution is higher for the minority races as compared to the whites. This is supported by the fact that the prisoners’ statistics show that 67% of the prisoners are from minority races. These figures will however be analyzed further

- 8. in the empirical review section (Brewer, M. R., & Nancy, H. A. 2008). All the above scenarios have been argued to favor the white race and also violate fundamental voting rights of the individuals affected. Among the key issues cited by previous studies that culminate to racial discrimination and infringement to the fundamental constitutional rights of individuals are; Selective application of the disenfranchisement laws. This refers to the partisan enforcement of the disenfranchisement laws thereby favoring a particular group of individuals. The studies further reiterate that in Kentucky, Virginia and Florida, 1 in every 5 African Americans are affected. This implies bias in the application of these laws, (Rand, 2013) "There is enough discrimination against us, and feeling alienated leads to recidivism. I served my sentence. I paid my debt to society. Why am I still doing time?" - Perry Hopkins, convicted felon and current community organizer for Communities United, talking about voting rights in Maryland. Racial discrimination has been meted on African Americans under the pretext of flawed felony laws. The discrimination has taken various forms in all spheres of life for this affected group including economic, social and political spectra (Behrens, Uggen, & Manza, 2003). Many studies have shown that voting rights are still a highly contested issue in America across all the states at a varying extent (Brewer & Nancy, 2008). Many states are passing strict laws with regard to voting rights that make it nearly impossible for the minority population especially African Americans to politically exercise their fundamental democratic rights. For instance, it is extremely difficult for a former convict with no parole to serve and who has committed to lead a reformed life to exercise this fundamental right under these flawed felony laws. It is four times less likely for a former Black convict to exercise his or her democratic rights than the Whites in the United States. The states with most stringent restrictions for the ex-convicts include Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Nebraska,

- 9. Nevada, Tennessee, Virginia and Wyoming being the leading contributing immensely to the staggering 5.89 million African Americans with no voting rights owing to their earlier criminal records (Manza & Uggen, 2008). Moreover, most of these aforementioned states have shown increasing tendencies to impose a lifetime ban blocking the Black ex-convict from participating in political course including enlisting as potential voters. Few states, for instance, Minnesota have not entirely banned these former convict from voting. However, the ex-convict must complete serving their parole after which they may be allowed to vote. Vermont and Maine are the only states that allow convicts to cast absentee ballots while they are in prison serving their jail terms. This pattern of voter suppression under flawed felony laws have locked out more than 4.5 million Americans most of whom are African American voters. Concerted efforts have been put in place especially by the Republican States which lead with the African American populations and Latinos, all of which have history of suppression of voters on criminal grounds. These have the long term effect of changing voting landscape in America. The states agitating to amend some clauses of voting rights acts by supreme court in these states with voting suppression normally faces legal bureaucratic ball rolling in overturning the controversial felony laws. Most of these laws violate individual constitutional rights and discriminate mostly against the black community. These laws have mostly disenfranchised the African-Americans ex-convict community from actively participating in politics either as voters or contenders casting doubts whether there is a veiled racism in these felony laws (Chin, 2002). Furthermore, restricting felons’ voting rights have the potential of perpetuating racial disparities in the course of discharging criminal justice. It is not uncommon to find young African Americans being over subjected to excessive police profiling and unnecessary police stop search tactics as compared to their

- 10. White counterparts. Similarly, drug convict African Americans are severely punished more than the White defendants both the same magnitude of the drug offence committed (Ewald, 2002). The ex-convict who completed their jail terms find themselves yet in another problem if they cannot find jobs besides having no prospects to vote in the future. Such fundamental rights are necessary for these former convicts to turn around their lives (Simpson, John , & Hawthorne, 1976). These economic and political disenfranchisement against Blacks under felony laws have been seen by most critics as current and future potential cause of racial tension among the Black and White communities (Khalilah, 2003). Currently, most of the felony disenfranchisement laws exist in books in some states. For instance, District of Columbia has felony disenfranchisement law on its books. Some states have made a forward step in restoring franchise to felons who have finished serving their jail sentences, however, most of the states have continued to hold fast onto and adopt laws that prevent felons from voting during their terms in prison (Behrens, Uggen, & Manza, 2003). In Massachusetts, convicts were allowed to vote until 2000 when the Bay state’s voter were subjected to a ballot question on the proposed state’s constitutional appeal which took away the incarcerated felons franchise. Such amended received approval of majority with 60% voting yes and 34% voting no. Similarly, in Utah; incarcerated felons had the voting right up to 1998 when major changes took place which saw amendment of the constitution to infringe on the felons’ franchise. Such proposition was passed by acclamation with 82% in support and a very small percentage opposing such amendments (Behrens, Uggen, & Manza, 2003). Different states have different ways of restoring voting rights for ex-convicts. Maine and Vermont remained the only states that with unrestricted voting rights for felons. These states allow convicts to vote during incarceration, through absentee ballot and also after the end of conviction terms. However, some states restore voting rights to convicts after they released

- 11. or completion of incarceration. Such states include some fourteen states and Colombia. Some states have their disenfranchisement on convict ending after completion of probation by these convicted criminals. Nineteen states require either incarceration or parole to be complete together with probation in order to restore these fundamental voting rights to felons. Conventionally, some states have disenfranchisement laws that relate to the magnitude of the crime committed by the convict. Under these laws, some offenders may regain back their voting rights on completion of incarceration, parole and probation. In this case offenders are required to file petition that in most cases may be denied. For instance, in Alabama, convicts with moral turpitude felony are denied voting rights, (Simpson, John , & Hawthorne, 1976) There is little doubt as to whether states have an equally substantial vested interest in preventing felons, especially those still incarcerated and under probation from voting in order to potentially to tide elections results in their favor (Tomkovicz, 1994). Hence, the legitimate concern over the voting rights as compelled by lobby group in disenfranchising felons cannot outweigh any supposed racial impact. Indeed, the Framers of the Reconstruction Amendments found most states authority to disenfranchise felons to be of such paramount significance that they willingly permit such motives through the Fourteenth Amendment. The Supreme Court allows states to function independently by separating the independent existence of the States and their governments the power to determine within the limits of the Constitution the qualifications of their own voters for state, including these African Americans (Clegg, 2001). There has been some progress in the recent past in fighting against the felony disenfranchisement laws by some lobby groups (Shapiro, 1993). In 2009, some non-native Americans serving probation sentences were denied the privilege of voting in the 2008 presidential elections and they filed suit against government officials with the consequence of South Dakota legislature amending the law which expanded space for

- 12. enjoyment of civil rights which came to effect in 2012. Under these new laws, the convict loses the voting rights until one has completed his or her full sentence including parole and probation. Alabama, on the other hand, has received heavy criticism regarding uneven application of the State’s felony disenfranchisement law; however, such criticism has been dismissed on the guise of lacking enough jurisdictional grounds (Manza, Brook, & Uggen, 2004). Similar incidents have been seen in Washington state were several African Americans have waged felony conviction challenge to the State disenfranchisement laws under the framework of the Fourth and Fifteenth Amendments of the American constitution and section 2 of the Voting Right Act of 1965 which provide against racial discrimination in fundamental voting rights. Such cases are normally turned down by the courts ageing out the appellants’ constitutional claims without hard evidence which include clear proofs intentional discrimination in the State’s criminal justice system (Uggen, Manza, & Thompson, 2006). Such bureaucratic standard intentional discrimination is normally hard to prove in court, hence further making the felony disenfranchisement laws tools of racial discrimination against African Americans. There is significant national momentum towards restoring voting rights to people with criminal convictions (Pinaire, Heumann, & Bilotta, 2002). Over the past two decades, more than 20 states have taken action both legislative or/ and executive to allow more people with past criminal convictions to vote, with intention aimed at getting the fundamental voting right sooner in a convenient manner, or for the felons to access that right more easily than it used to be in the past. Several initiatives are being put in place toward realization of those voting rights for the minorities especially African Americans. For example, the Brennan Center has been put in place to acts as legal counsel in the broader movement to restore voting rights to minorities with convictions cases (Preuhs, 2001). The Center scrutinizes state constitutions, statutes, and

- 13. administrative rules to understand and interpret felon convicts who are permitted to vote under what circumstances and how these rights might be expanded progressively to achieve universal suffrage. This provides useful analyses at crucial stages in the legislative processes to push for reforms in felony disenfranchisement laws. These analyses are also key in informing the general proposals for reform intended. In New York and Alabama, the Brennan Center conducted many surveys of local boards of elections, which documented that election officials were disenfranchising citizens who were legally eligible to vote. The Brennan Center then worked with election officials for the betterment of their practices and created education materials to ensure that citizens with past convictions are aware of their voting rights (Rodger, George , & Kenneth, 2006). Reform efforts in reforming felony disenfranchisement laws. In last few decades, there have been and improving trend in lifting the felony disenfranchisement restrictions, including procedures for applying for the restoration of civil rights for African Americans who had fulfilled their punishments for felonies by either finishing their parole or incarceration (Harvey, 1994). In 2007, Florida's Republican Governor successfully agitated for change geared towards elimination of felony disenfranchisement laws making it easier for most convicted felons to regain their voting rights much faster after serving their sentences and probation terms (Eisenstein & Jacob, 1977). Consequence, by 2008 about one million of the felons who had previously been denied right to vote, and who would have otherwise been disenfranchised under the older rules had their voting rights restored to them. From 2008, less severe disenfranchisement rules have been passed in majority of the states (Ewald C. A., 2009). However, felons may not apply to the court for restoration of voting rights until seven years after completion of sentence, probation and parole as seen in most Republican states (Fellner & Marc, 1998). In 2005, Democratic governor in Iowa issued an executive order restoring the right to vote for all

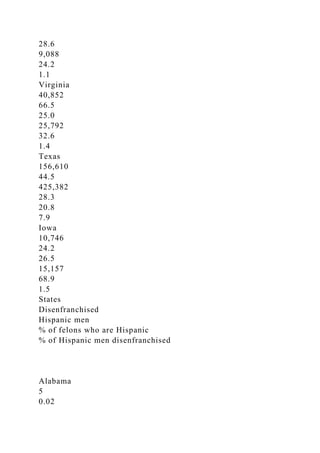

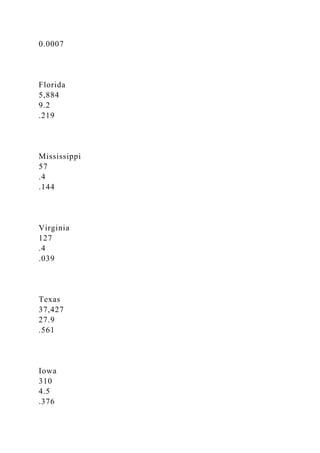

- 14. persons who had completed their supervision. Iowa's Supreme Court upheld mass re-enfranchisement of convicted felons in order to restore their voting rights. More, states disenfranchise felons for various period of time following their conviction. With except of Maine and Vermont, every state prohibits felons from voting while still in prison (Khalilah , 2003). The study therefore, attempt address the gaps by attempting to find corrective measures against felony disenfranchisement laws against minority especially the African American (Ansley, 1991). TABLE 1(The sentencing Project, 2008) States # disenfranchised African Americans % of Felons Who are African American % of African American men who are disenfranchised # disenfranchised men % of men who are white % of White men who are di Alabama 42,072 66.4 73,429 33.3 6.3 Florida 109,063 31.2 169,931 55.4 42.6 3.5 Mississippi 81,700 75.3

- 15. 28.6 9,088 24.2 1.1 Virginia 40,852 66.5 25.0 25,792 32.6 1.4 Texas 156,610 44.5 425,382 28.3 20.8 7.9 Iowa 10,746 24.2 26.5 15,157 68.9 1.5 States Disenfranchised Hispanic men % of felons who are Hispanic % of Hispanic men disenfranchised Alabama 5 0.02

- 17. TABLE 1: Shows disenfranchisement rates for men by race and ethnicity this graph shows the number of disenfranchised African Americans also the percent of felons who are African American. These 13 states have been chosen to do this study based upon the disenfranchised rate of race and ethnicity. Research Design & Methodology Design This Research is an exploratory study that uses quantitative data to emphasize the relationship of Felony disenfranchisement laws and how they may be racially discriminatory against African Americans. For this study the independent variable is Felony disenfranchisement laws. The dependent variable is racial discrimination against African Americans. Methodology The Purpose of this research is to examine Felony disenfranchisement laws and racial discrimination against African Americans. The independent variable is Felony disenfranchisement laws. The dependent variable is racial discrimination against African Americans. This is an exploratory study that will examine disenfranchisement laws and the correlation between that and racial discrimination against African Americans. Racial discrimination has been meted on African Americans under the pretext of flawed felony laws. The discrimination has taken various forms in all spheres of life for this affected group including economic, social and political spectra (Behrens, Uggen, & Manza, 2003). Many studies have shown that voting rights are still highly contested issue in America across all the states at a varying extent (Brewer & Nancy, 2008). Many states are passing strict

- 18. laws with regard to voting rights that make it nearly impossible for the minority especially the African Americans to politically exercise their fundamental democratic rights. For instance, it is extremely difficult for a former convict with no parole to serve and who has committed to lead a reformed life to exercise this fundamental right under these flawed felony laws. It is four times less likely for a former Black convict to exercise their democratic rights than the Whites in the United States. Moreover, most of these aforementioned states have shown increasing tendencies to impose a lifetime ban blocking the Black ex-convict from participating in political course including enlisting as potential voters Sample Population There were 23 Rust college students who participated in filling out the survey questionnaire; some of the students came from the Memphis metropolitan statistical area. And some were from the Marshall County. The participants were African American and Hispanics the study used. A non-probability sampling based on availability the study was conducted at the Library, in the Bcs lab and also in front of the cafeteria between the hours of 12pm.-2pm. Instrument There are two parts to the research instrument. The first section includes demographics of the participants. The first demographic question asks if they are between of 18- 35+. The second demographic question indicates race African American, Hispanic and other. And the third demographic question about gender. The second section to the research shows respondents answer 20 questions relating to Felony laws in correlation to how they racially discriminate against minorities. The participants will have to fill in the information according to the demographics for each question. Questionnaires consisted of questions that examined incarceration rates of minorities knowledge about disenfranchised felons and also general laws on voting. Examples of the Questionnaires include: Do you know how

- 19. many states deny the right to vote to all individuals with felony convictions even after they have completed their sentence? Do you know the number of ex-offenders disenfranchised as a result of felony laws? Reliability and Validity The instrument that was used in examining the findings of this research was a survey. To analyze data, descriptive statistic was employed. The instruments used were for the regression analysis through which provided the correlation coefficients of the racial prison composition and the coefficient of determination. The descriptive statistic and tables were obtained from SPSS statistics. The information presented purposed to show the relationship between racial discrimination and felony disenfranchisement laws. Data Analysis and Findings Introduction The purpose of this study is to examine Felony disenfranchisement laws and whether or not they are a form of racial discrimination against African Americans. The independent variable is Felony disenfranchisement laws. The dependent variable is racial discrimination against African Americans. The research was conducted through the method of surveying 23 students that attend Rust College and in the surrounding community. Demographic The Demographic statistical analysis resulted in age, gender, and ethnic group. The age of the participants for this study was 30.4% for ages (18-21) that participated and 47.8% for ages (21-24) for ages (25-28) that participated 17.4% and for ages (29-32+) that participated 4.3%. The Gender of the participants there were 56.5% for the males who participated in the study and 43.5% for the females who were participants in the study. The Ethnic Group of the participants is as follows African Americans were 52.2% Asians were 4.3% Hispanics

- 20. were 21.7% Native American made up 17.4% and there was a 4.3% again for participants who were other. Table 1: Gender Table Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent Valid Male 13 56.5 56.5 56.5 Female 10 43.5 43.5 100.0 Total 23 100.0 100.0 Table 2: Age Table Frequency

- 22. Table 3: Ethnic Group Table Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent Valid African Americans 12 52.2 52.2 52.2 Hispanic 5 21.7 21.7 73.9 Native American 4 17.4 17.4 91.3 Asian 1 4.3 4.3 95.7 Other 1 4.3 4.3 100.0

- 23. Total 23 100.0 100.0 Tables: 1, 2 and 3: The demographic tables provide the student ages, gender and also ethnic groups of 23 students. It can be seen that 13 of the respondents, or 56.5% are males and 10 of the respondents or 43.5% are females. The age range of the students varies from a range of eighteen to thirty two and up, with the highest number of ages being ages 21-24 which gave me 11(47.8%) respondents. The ethnic groups of the respondents were 12 (52.2%) African Americans, 5 (21.7%) Hispanic, 4 (17.4%) Native Americans, 1 (4.3%) respondent for Asians and 1 (4.3%) as others which gave me a total of 23 (100%) for ethnic groups. Table 4: Cross-Tabulation of Ethnicity and Question 6 Ethnic Group * ShouldConvictsLoseRightToVote Cross tabulation ShouldConvictsLoseRightToVote Total Yes No Neutral Ethnic Group African Americans

- 24. Count 7 4 1 12 % of Total 30.4% 17.4% 4.3% 52.2% Hispanic Count 2 3 0 5 % of Total 8.7% 13.0% 0.0% 21.7% Native American Count 2 2 0 4 % of Total

- 25. 8.7% 8.7% 0.0% 17.4% Asian Count 1 0 0 1 % of Total 4.3% 0.0% 0.0% 4.3% Other Count 0 0 1 1 % of Total 0.0% 0.0% 4.3% 4.3% Total Count 12 9

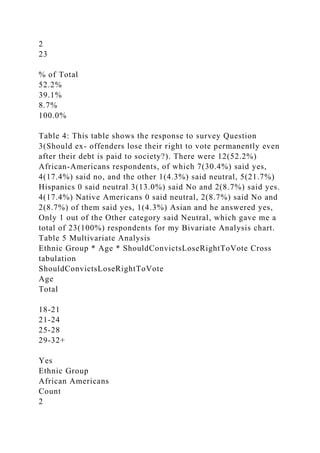

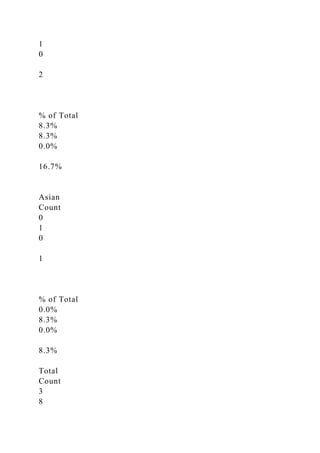

- 26. 2 23 % of Total 52.2% 39.1% 8.7% 100.0% Table 4: This table shows the response to survey Question 3(Should ex- offenders lose their right to vote permanently even after their debt is paid to society?). There were 12(52.2%) African-Americans respondents, of which 7(30.4%) said yes, 4(17.4%) said no, and the other 1(4.3%) said neutral, 5(21.7%) Hispanics 0 said neutral 3(13.0%) said No and 2(8.7%) said yes. 4(17.4%) Native Americans 0 said neutral, 2(8.7%) said No and 2(8.7%) of them said yes, 1(4.3%) Asian and he answered yes, Only 1 out of the Other category said Neutral, which gave me a total of 23(100%) respondents for my Bivariate Analysis chart. Table 5 Multivariate Analysis Ethnic Group * Age * ShouldConvictsLoseRightToVote Cross tabulation ShouldConvictsLoseRightToVote Age Total 18-21 21-24 25-28 29-32+ Yes Ethnic Group African Americans Count 2

- 27. 5 0 7 % of Total 16.7% 41.7% 0.0% 58.3% Hispanic Count 0 1 1 2 % of Total 0.0% 8.3% 8.3% 16.7% Native American Count 1

- 28. 1 0 2 % of Total 8.3% 8.3% 0.0% 16.7% Asian Count 0 1 0 1 % of Total 0.0% 8.3% 0.0% 8.3% Total Count 3 8

- 29. 1 12 % of Total 25.0% 66.7% 8.3% 100.0% No Ethnic Group African Americans Count 1 1 1 1 4 % of Total 11.1% 11.1% 11.1% 11.1% 44.4% Hispanic Count 2 0 1

- 30. 0 3 % of Total 22.2% 0.0% 11.1% 0.0% 33.3% Native American Count 1 1 0 0 2 % of Total 11.1% 11.1% 0.0% 0.0% 22.2% Total Count 4 2 2 1

- 31. 9 % of Total 44.4% 22.2% 22.2% 11.1% 100.0% Neutral Ethnic Group African Americans Count 0 1 1 % of Total 0.0% 50.0% 50.0% Other Count 1 0 1

- 32. % of Total 50.0% 0.0% 50.0% Total Count 1 1 2 % of Total 50.0% 50.0% 100.0% Total Ethnic Group African Americans Count 3 6 2 1 12

- 33. % of Total 13.0% 26.1% 8.7% 4.3% 52.2% Hispanic Count 2 1 2 0 5 % of Total 8.7% 4.3% 8.7% 0.0% 21.7% Native American Count 2 2 0 0 4

- 34. % of Total 8.7% 8.7% 0.0% 0.0% 17.4% Asian Count 0 1 0 0 1 % of Total 0.0% 4.3% 0.0% 0.0% 4.3% Other Count 0 1 0 0 1

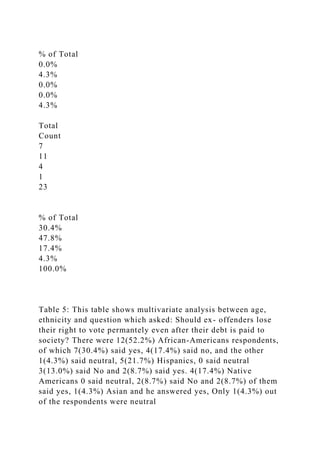

- 35. % of Total 0.0% 4.3% 0.0% 0.0% 4.3% Total Count 7 11 4 1 23 % of Total 30.4% 47.8% 17.4% 4.3% 100.0% Table 5: This table shows multivariate analysis between age, ethnicity and question which asked: Should ex- offenders lose their right to vote permantely even after their debt is paid to society? There were 12(52.2%) African-Americans respondents, of which 7(30.4%) said yes, 4(17.4%) said no, and the other 1(4.3%) said neutral, 5(21.7%) Hispanics, 0 said neutral 3(13.0%) said No and 2(8.7%) said yes. 4(17.4%) Native Americans 0 said neutral, 2(8.7%) said No and 2(8.7%) of them said yes, 1(4.3%) Asian and he answered yes, Only 1(4.3%) out of the respondents were neutral

- 36. Those between the ages 18-21 there were 7(30.4%) respondents, between the ages of 21-24 there were 11(47.8%) respondents, between the ages of 25-28 there were 4(17.4%) respondents, between 29-32+ there were 1(4.3%) respondent. There were a total of 12(52.2%) of African Americans who agreed that convicts should lose their right to vote. Between those ages of 18-21 there were 2(8.7%) African Americans agreed and 1(4.3%) for Native American. Between the ages of 21-24 there were 5(21.7%) African Americans 1(4.3%) Native American 1(4.3%) Hispanic and 1(4.3%) Asian who agreed that convicts should lose their right to vote. Between the ages 25-28 there was 1(4.3%) Hispanic who agreed that convicts should lose their right to vote. There were a total of 9(39.1%) respondents who disagreed that convicts should lose their right to vote. Between the ages of 18-21 there were a total of 4(17.4%) respondents. 1(4.3%) African American, 2(8.7%) Hispanics and 1(4.3%) Native American. Between the ages of 21-24 there was total of 2(8.7%) respondents 1(4.3%) African American and 1(4.3%) Native American. Between the ages of 25-28 there were 2(8.7%) respondents 1(4.3%) African American and 1(4.3%) Hispanic. Between the ages of 29-32+ there were a total of 1(4.3%) respondent which was African American. There was 1(4.3%) respondent who remained neutral regarding if convicts should lose their right to vote and they are considered as other. Conclusion By attempting to bring certainty to the controversies facing the legislature regarding the legitimacy of felony disenfranchisement laws and establishing whether or not these laws are racially discriminative, this study will have provided reasonable cause for legislative action on the laws at hand. Also, by explaining the outcome in details, and in a manner that is acceptable by all, the study will have settled judicial disputes spooked by the ambiguity and controversy of these laws. Therefore outcome of this study will not only be useful to

- 37. judiciary and legislature, but to the entire public that is disturbed by the controversy surrounding these laws. Denying the vote to ex-offenders is antidemocratic, and undermines the nation’s commitment to rehabilitating people who have paid their debt to society. And after doing countless and relentless research and interviews, and using different instrument such as surveys the results have been phenomenal. According to my research Felony laws have a sizable racial impact: 13 percent of African Americans alone have had their votes taken away, seven times the national average. Having conducted a survey where 23 respondents were asked questions about felony voting laws and also rights that people naturally have as Americans. . But even though it is policy, denying felons the vote has been a disaster because of the chaotic and partisan way it has been carried out. The evidence bears out that felony disenfranchisement laws should be repealed, or amended. This study through literature review has been able to establish the constitutional conflicts that exist between felony disenfranchisement laws and the Human rights clauses of the constitutional amendments. Among the amendments violated include the 14th amendment chapter one and the 24th amendment to the constitution. Also, the study has established an existing racial imbalance in the prison composition that implies racial discrimination. To add to that, every state has its own criterion for enforcement of felony disenfranchisement laws which means that these laws can be abused by authorities in power on racial or other malignant grounds. The findings demonstrated a clear awareness of the subject population to issues of discrimination in sentencing to felony voting laws. 52% percent of the respondents indicated that felony voting laws and regulations hurt the black communities as well as the overall voter’s outcome. With the overwhelming evidence of the remarkable amount of nationwide felony voting laws it is no surprise that the findings of the study are aligned with the efforts of elected officials. The desire of the people to see reform is slowly affecting these laws but however there is

- 38. much work to be done if true equality is to be achieved not only with felony voting laws but with the criminal justice system as a whole. References Ansley, L. F. (1991). Race and Core curriculum in legal education. California Law Review, 22(3), 1511-1597. Behrens, A., Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2003). Ballot manipulation and the "Menace of Negro Domination" Racial Threat and Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States 1850-2002. American Journal of Sociology, 109(3), 559- 605. Brewer, M. R., & Nancy, H. A. (2008). The racialization of crime and punishment criminal Justice, color blind racism, and the political economy of prison industrial complex. American Behavioral Scientist, 51(5), 625-644. Booker T. Washington, Up From Slavery (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2002), 134. Chin, G. J. (2002). Race, the war on drugs, and collateral consequences of criminal conviction. Journal of Gender, Race and Justice, 6(253), 567- 634. Clegg, R. (2001). Who should vote? Texas Law Review. & Pol., 1, 159-177. Eisenstein, J & Jacob, H. (1977). Felony Justice. Boston: Little Brown.

- 39. Ewald, A. (2002). Civil Death: the Ideological paradox of criminal disenfranchisement Law in The United States. Wisconsin Law Review, 11045- 1132. Ewald, A. (2002). Civil Death: the Ideological paradox of criminal disenfranchisement Law in The United States. Wisconsin Law Review, 10047- 10135. Ewald, C. A. (2009). "Criminal disenfranchisement and the challenge of American Federalism" publius. Journal of federalism, 39(3), 527-556. Fellner, J., & Marc, M. (1998). Losing the votes: The impact of felony disenfranchisement laws the United States. New York: Sentencing project. Harvey, E. A. (1994). Ex-felon disenfranchisement and its influence on Black Vote: The need for a second look. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Jeff Manza, PhD, Christopher Uggen, McKnight, (2006). Locked Out, Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy. 142(3), 1145-1189. Khalilah, B. L. (2003). One lens multiple view: felony disenfranchisement laws and American Political inequality. New York: The Ohio State University. Manza, J., & Uggen, C. (2008). Locked Out: felony disenfranchisement and American Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press. Manza, J., Brook, c., & Uggen, C. (2004). Public attitude toward felony disenfranchisement in The United States. Public Opinion Quarterly, 68(2), 275-286. Marc Mauer, (2006). Felon Disenfranchisement: A policy whose time has passed: Published In the Human Rights Magazine. Pauli Murray, States' Laws on Race and Color, (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1997), 414.

- 40. Pinaire, B., Heumann, M., & Bilotta, L. (2002). Barred from the vote: Public attitude towards the disenfranchisement of felons. Fordham Urb, 30(1), 1519-1533. Preuhs, R. R. (2001). State felony disenfranchisement policy. Social Sciences Quarterly, 84(4), 733-748. Rand Paul, JD, US Senator, (2013). The Collateral Damage of an Insidious Drug-War Weapon: available at paul.senate.gov. Rodger, C., George, T. C., & Kenneth, L. K. (2006). Bullet and the Ballot? The case for Felony Disenfranchisement statutes. Journal of Gender, Social policy and the Law, 14(1), 1-26. Shapiro, L. A. (1993). Challenging criminal disenfranchisement under Voting Rights Acts: ya New strategy. The Yale Law Journal, 103(2), 537-566. Simpson, P. L., John, A., & Hawthorne, K. (1976). The Real Fiction of American Revolution. Studies in the literary Imagination, 9(2), 56-77. The Washington Post Editorial, (2012). A Life Time sentence for Felons: available at washingtonpost.com. Tonkovich, J. J. (1994). Endurance of felony murder rule: a study of forces that shape our Criminal law. The Wash & Lee L. Rev, 51, 429-1433. Uggen, C., Manza, J., & Thompson, M. (2006). Citizenship democracy and civic reintegration Of criminal offenders. The annals of the American academy of Political and Social Science, 605(1), 281-310.

- 41. Appendix Code Book Question Variable Response 1 Gender (1)Male=13 (2) Female=10 2 Ethnic Group (1)African American=15 (2)Hispanic=3 (3)Native American=2 (4)Asian=1 (5) Other=2 3 Age (1) 18-21=7 (2) 22-24=11 (3) 25-28=4 (4) 29-32+=1 4 Do you believe that every us citizen should be able to exercise their right vote regardless of past or present criminal history?

- 42. Yes Neutral No 5 Do you feel that African Americans are more affected by disenfranchisement laws than Caucasians? Yes Neutral No 6 Should ex- offenders lose their right to vote permanetly even after their debt is paid to society? Yes Neutral No 7 Do you believe disenfranchisement laws were created to racially profile against African Americans? Yes Neutral No 8 Is this an important topic that needs to be addressed more in the African American community? Yes Neutral No 9 Do you feel that felony disenfranchisement laws and regulations hurt the black community? Yes Neutral No

- 43. 10 Have you or someone you know personally been affected by the disenfranchisement laws that are enacted? Yes Neutral No 11 Were you informed about the disenfranchisement laws and the restrictions on convicted felons before you read this survey? Yes Neutral No 12 After reading these survey Questions does this change your views on convicted felons right to vote? Yes Neutral No 13 Do you believe that this issue should be voted on a state by state basis? Yes Neutral No 14 Should each state have the same laws regarding voting rights for convicted felons? Yes Neutral No 15 Should states deny the right to vote to all individuals with felony convictions even after they have completed their

- 44. sentences? Yes Neutral No 16 Do you believe that racial discrimination has something to do with felony disenfranchisement laws? Yes Neutral No 17 Do you think states should prohibit voting while incarcerated with felony offenses? Yes Neutral No 18 Approximately 6 million people were unable to vote due to felony conviction could this have changed the outcome for presidency? Yes Neutral No 19 In states that disenfranchise ex-offenders, should African American men permanently lose their right to vote? Yes Neutral No 20 Are African Americans mostly affected by felony disenfranchisement laws? Yes Neutral

- 45. No 21 Is this disenfranchisement something that has been repeated in history when it comes to voting Yes Neutral No 22 Individuals convicted of felonies should receive full voting rights back after they complete their prison sentence? Yes Neutral No 23 Does felony disenfranchisement hurt the voting outcome judging by the number of people who don't vote? Yes Neutral No

- 46. “The Felony Disenfranchisement Laws Survey Questions” Gender: Male or Female Age: (1) 18-21=7 (2) 22-24=11 (3) 25-28=4 (4) 29-32+=1 Ethnic Group: African American, Hispanic, Native American, Asian, and Other 1. Do you believe that every U.S citizen should be able to exercise their right vote regardless of past or present criminal history? Yes or no 2. Do you feel that African Americans are more affected by disenfranchisement laws than Caucasians? Yes or No 3. Should ex- offenders lose their right to vote permantely even after their debt is paid to society? Yes or no or Neutral 4. Do you believe disenfranchisement laws were created to racially profile against African Americans? Yes or no or neutral 5. Is this an important topic that needs to be addressed more in the African American community? Yes or no or neutral 6. Do you feel that felony disenfranchisement laws and regulations hurt the black community? Yes or no or neutral 7. Are you or someone you know personally affected by the disenfranchisement laws that are enacted? Yes or No or neutral 8. Were you informed about the disenfranchisement laws and the restrictions on convicted felons before you read this survey? Yes or No or neutral 9. After reading this research paper does this change your views on convicted felons right to vote? Yes or No or neutral 10. Do you believe that this issue should be voted on a state by state basis? Yes or No or neutral 11. Should each state have the same laws regarding voting rights for convicted felons? Yes or No or neutral 12. Should states deny the right to vote to all individuals with

- 47. felony convictions even after they have completed their sentences? Yes or No or neutral 13. Do you believe that racial discrimination has something to do with felony disenfranchisement laws? Yes or No or neutral 14. Do you think states should prohibit voting while incarcerated with felony offenses? Yes or No or Neutral 15. Approximately 6 million people were unable to vote due to felony conviction could this have changed the outcome for presidency? Yes or No or Neutral 16. Should ex-offenders of the law that are minorities permanently lose their right to vote if they have paid their debt to society? Yes or No or Neutral 17. Are African Americans mostly affected by felony disenfranchisement laws? Yes or No or Neutral 18. Is this disenfranchisement something that has been repeated in history when it comes to voting? Yes or No or Neutral 19. Individuals convicted of felonies should receive full voting rights back after they complete their prison sentence? Yes or No or Neutral 20. Does felony disenfranchisement hurt the voting outcome judging by the number of people who don't vote? Yes or No or Neutral