Southwest Pennsylvania EH Project Nov14 2014

- 1. Fracking: What are the risks to Ohio Melanie Houston, MS Ohio Environmental Council November 2014 11/26/2014 1

- 2. Ohio Environmental Council « Advocacy, non-profit « Legislative initiatives « Legal action « Science and policy « Network and partnerships

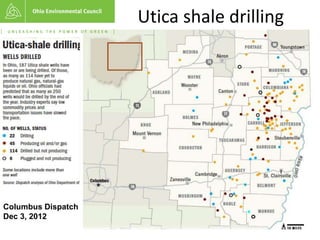

- 4. Utica shale drilling Columbus Dispatch Dec 3, 2012

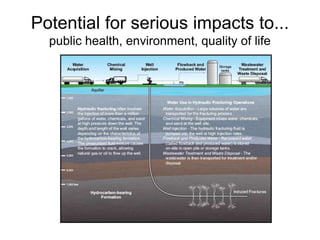

- 5. Potential for serious impacts to... public health, environment, quality of life

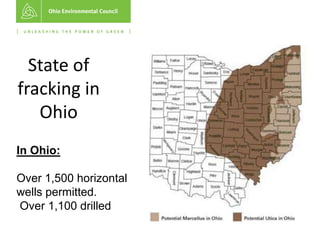

- 6. State of fracking in Ohio In Ohio: Over 1,500 horizontal wells permitted. Over 1,100 drilled

- 7. Risks to water quality • Cornell University study – “An uncontrolled health experiment on an enormous scale” • Duke University study – Found methane concentrations 17X higher in drinking water wells closer to natural gas wells • Akron Beacon Journal – 1 million pounds of chemicals used at a single well site

- 8. Air contamination • Colorado School of Public Health: – “Our data show that it is important to include air pollution in the national dialogue on natural gas development that has focused largely on water exposures to hydraulic fracturing,” said Lisa McKenzie, Ph.D., MPH – “We also calculated higher cancer risks for residents living nearer to the wells as compared to those residing further [away],” the report said. “Benzene is the major contributor to lifetime excess cancer risk from both scenarios.” http://attheorefront.ucdenver.edu/?p=2546

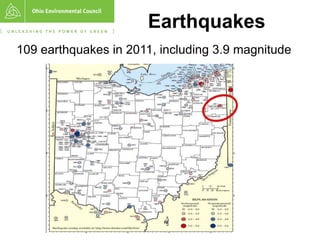

- 9. Earthquakes 109 earthquakes in 2011, including 3.9 magnitude

- 10. Brine dump Brine dump in storm drain leading to Mahoniing River in Youngstown, Ohio (Feb 2012)

- 11. Morgan County spill Morgan County • 100 barrel spill of drilling mud into an unnamed creek & unknown amount of wet gas released.

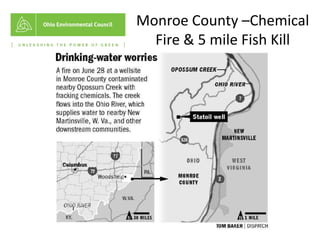

- 12. Monroe County –Chemical Fire & 5 mile Fish Kill

- 13. October 2014 – 3 Incidents in just 3 days Guernsey County – worker injury/ explosion Jefferson county – leaking well, evacuation Monroe County – pipeline fire

- 14. Local impacts

- 15. SAFER GAS Act To include provisions to require: • Protection of public water sources & floodplains • Increased air monitoring • Increased public input (right to know & right to appeal permit terms + conditions) • More inspectors + better reporting + tracking of incidents on ODNR website • Waste fluid recycling + reuse • Better regulation of waste materials

- 16. Increased buffer zones • Between wells & water bodies • Between wells & homes • Between wells & ecologically sensitive areas *Image of Wayne National Forest

- 17. Funds for Emergency Response • Equipment & training • Industry should foot bill (severance tax)

- 18. Spill containment rules • Need legislature to require ODNR issue emergency rules

- 19. Chemical disclosure • Need full disclosure of trade secret chemicals… …To emergency responders & drinking water utilities

- 20. OEC contacts: Melanie Houston MHouston@theoec.org (614) 487-5849 Nathan Johnson Njohnson@theOEC.org (614) 487-5841

- 21. Ohio’s state lands open to drilling • Quail Hollow State Park • Wayne National Forest *Image of Wayne National Forest

- 22. Relevant & timely legislation • SB 315 – Governor’s energy legislation • Budget bill (HB 59) – radioactive waste from fracking, definition of TENORM • Upcoming – severance tax bill, HB 490/midterm budget review bill

- 23. A meeting with the Southwest Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project Melanie Houston Raina Rippel Jill Kriesky Deborah Cowden November 7, 2014 11/26/2014 23

- 24. Welcome •How the meeting came about •Goals for the meeting •Meeting Agenda •Housekeeping 11/26/2014 24

- 25. Ohio Environmental Council « Legislative initiatives « Legal action « Science and policy « Network and partnerships Melanie Houston Director of Water Policy & Environmental Health

- 26. Today’s Speakers Jill Kriesky SWPA-EHP Deb Cowden Family Physician Raina Rippel SWPA-EHP

- 27. Introductions of attendees •In person attendees •Webinar participants – please introduce yourself through the chat box! •Name, organization & interest in attending today 11/26/2014 27

- 28. State of fracking in Ohio In Ohio: Over 1,500 horizontal wells permitted. Over 1,100 drilled

- 29. Potential for serious impacts to... public health, environment, quality of life

- 30. Earthquakes 109 earthquakes in 2011, including 3.9 magnitude

- 31. Brine dump Brine dump in storm drain leading to Mahoniing River in Youngstown, Ohio (Feb 2012)

- 32. Morgan County spill Morgan County • 100 barrel spill of drilling mud into an unnamed creek & unknown amount of wet gas released.

- 33. Monroe County –Chemical Fire & 5 mile Fish Kill

- 34. October 2014 – 3 Incidents in just 3 days Guernsey County – worker injury/ explosion Jefferson county – leaking well, evacuation Monroe County – pipeline fire

- 35. Local impacts

- 36. SAFER GAS Act To include provisions to require: • Protection of public water sources & floodplains • Increased air monitoring • Increased public input (right to know & right to appeal permit terms + conditions) • More inspectors + better reporting + tracking of incidents on ODNR website • Waste fluid recycling + reuse • Better regulation of waste materials

- 37. Increased buffer zones • Between wells & water bodies • Between wells & homes • Between wells & ecologically sensitive areas *Image of Wayne National Forest

- 38. Funds for Emergency Response • Equipment & training • Industry should foot bill (severance tax)

- 39. Spill containment rules • Need legislature to require ODNR issue emergency rules

- 40. Chemical disclosure • Need full disclosure of trade secret chemicals… …To emergency responders & drinking water utilities

- 41. OEC contacts: Melanie Houston MHouston@theoec.org (614) 487-5849 Nathan Johnson Njohnson@theOEC.org (614) 487-5841

- 42. www.environmentalhealthproject.org Human Health Impacts of Marcellus Shale Gas Extraction Ohio Environmental Council, Columbus, OH Raina Rippel, Director SWPA Environmental Health Project November 7, 2014

- 43. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Southwest Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project (EHP) Our mission is to respond to individuals’ and communities’ need for access to accurate, timely and trusted public health information and health services associated with natural gas extraction.

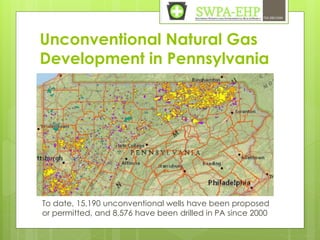

- 44. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Unconventional Natural Gas Development in Pennsylvania To date, 15,190 unconventional wells have been proposed or permitted, and 8,576 have been drilled in PA since 2000

- 45. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Regional Shale Plays 724.260.5504

- 46. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504

- 47. EHP Resources Health Evaluation and Support Nurse practitioner Health exams Consultations Referrals for health services Health provider education Clinical toxicity profiles SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Accurate, Trusted, and Timely Public Health Information Identification of exposure pathways Measurement tools Consultation on water reports Assessment of air exposures Evaluation of health risks Information assessment

- 48. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT World Health Organization’s Public Health Approach The three main public health functions are: 1. The assessment and monitoring of the health of communities and populations at risk to identify health problems and priorities. 724.260.5504 2. The formulation of public policies designed to solve identified local and national health problems and priorities. 3. To assure that all populations have access to appropriate and cost-effective care, including health promotion and disease prevention services.

- 49. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT EHP Tools for Monitoring Air monitoring of particulate matter: • Speck • Dylos 724.260.5504 Water monitoring for conductivity and total dissolved solids: • CATTFish • TDS meters Soil monitoring: under development this fall In conjunction with monitoring activities, our Nurse Practitioner is available by appointment in our McMurray office and onsite in Washington County to conduct health evaluations and work with families to seek appropriate medical care.

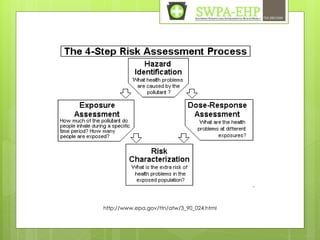

- 50. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT http://www.epa.gov/ttn/atw/3_90_024.html 724.260.5504

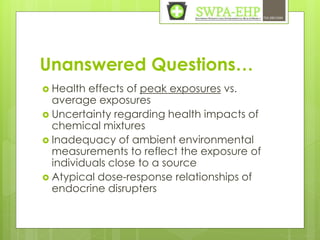

- 51. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Unanswered Questions… Health effects of peak exposures vs. average exposures Uncertainty regarding health impacts of chemical mixtures Inadequacy of ambient environmental measurements to reflect the exposure of individuals close to a source Atypical dose-response relationships of endocrine disrupters 724.260.5504

- 52. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT For More Information www.environmentalhealthproject.org 724.260-5504 RRippel@environmentalhealthproject.org 724.260.5504

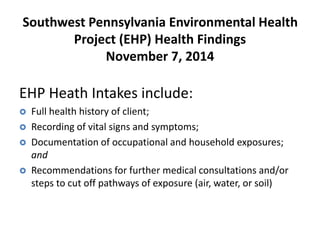

- 53. Southwest Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project (EHP) Health Findings November 7, 2014 EHP Heath Intakes include: Full health history of client; Recording of vital signs and symptoms; Documentation of occupational and household exposures; and Recommendations for further medical consultations and/or steps to cut off pathways of exposure (air, water, or soil)

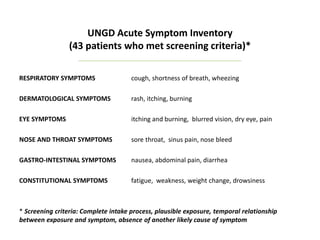

- 54. UNGD Acute Symptom Inventory (43 patients who met screening criteria)* ______________________________________________ RESPIRATORY SYMPTOMS cough, shortness of breath, wheezing DERMATOLOGICAL SYMPTOMS rash, itching, burning EYE SYMPTOMS itching and burning, blurred vision, dry eye, pain NOSE AND THROAT SYMPTOMS sore throat, sinus pain, nose bleed GASTRO-INTESTINAL SYMPTOMS nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea CONSTITUTIONAL SYMPTOMS fatigue, weakness, weight change, drowsiness * Screening criteria: Complete intake process, plausible exposure, temporal relationship between exposure and symptom, absence of another likely cause of symptom

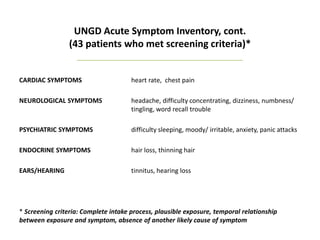

- 55. 724.260.5504 UNGD Acute Symptom Inventory, cont. (43 patients who met screening criteria)* __________________________________ CARDIAC SYMPTOMS heart rate, chest pain NEUROLOGICAL SYMPTOMS headache, difficulty concentrating, dizziness, numbness/ tingling, word recall trouble PSYCHIATRIC SYMPTOMS difficulty sleeping, moody/ irritable, anxiety, panic attacks ENDOCRINE SYMPTOMS hair loss, thinning hair EARS/HEARING tinnitus, hearing loss * Screening criteria: Complete intake process, plausible exposure, temporal relationship between exposure and symptom, absence of another likely cause of symptom

- 56. 724.260.5504 Symptoms Reported to EHP Nurse Practitioner N=43 Individuals reporting Percentage of total cases Respiratory 25 58% Dermatologic 27 62% Eye 22 51% Nose & throat 29 67% Gastro-Intestinal 22 51% Constitutional 17 39% Cardiac 8 18% Neurological 30 70% Psychiatric 27 62% Endocrine 5 11% Ear/hearing 10 23%

- 57. Criteria for Inclusion • A complete health history was taken; • Exposures were environmental, not occupational; • A potential exposure to UNGD had occurred, AND symptoms were present where there may have been an exposure. Robert Donnan ©2011

- 58. Attribution of symptoms • Temporal relationship – Development of symptom (or exacerbation of pre-existing symptom) after onset of gas extraction activities. • Plausible exposure – Identifiable exposure source in proximity to individual experiencing symptoms.

- 59. Attribution of symptoms, cont. • Absence of more likely explanation – Symptoms were not attributed to gas extraction activities if an individual had an underlying medical condition that was as (or more) likely to have caused the symptom, or if an exposure unrelated to gas drilling was as (or more) likely to have caused the symptoms.

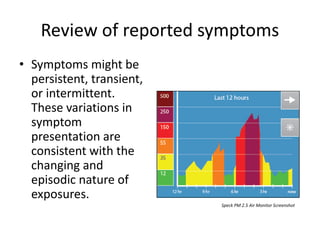

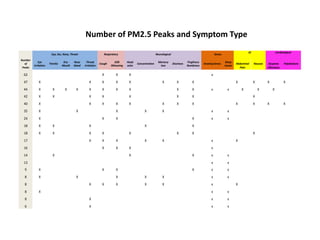

- 60. Review of reported symptoms • Symptoms might be persistent, transient, or intermittent. These variations in symptom presentation are consistent with the changing and episodic nature of exposures. Speck PM 2.5 Air Monitor Screenshot

- 61. Respiratory • 25 people reported respiratory symptoms. • That’s 58% of the cases. • Of these 25 people, 80% report cough, 52% report shortness of breath, 36% reported wheezing. Breakdown of Symptoms _____________________ Dermatological • 27 people reported dermatological symptoms. • That’s 62% of the cases. • Of these 27 people, 52% report rash, 41% report itching, 11% burning. Eye • 22 people reported eye symptoms. • That’s 51% of the cases. • Of these 22, 82% reported itching and burning.

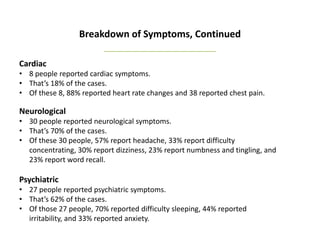

- 62. Breakdown of Symptoms, Continued _____________________ Cardiac • 8 people reported cardiac symptoms. • That’s 18% of the cases. • Of these 8, 88% reported heart rate changes and 38 reported chest pain. Neurological • 30 people reported neurological symptoms. • That’s 70% of the cases. • Of these 30 people, 57% report headache, 33% report difficulty concentrating, 30% report dizziness, 23% report numbness and tingling, and 23% report word recall. Psychiatric • 27 people reported psychiatric symptoms. • That’s 62% of the cases. • Of those 27 people, 70% reported difficulty sleeping, 44% reported irritability, and 33% reported anxiety.

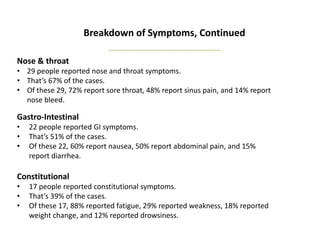

- 63. Breakdown of Symptoms, Continued _____________________ Nose & throat • 29 people reported nose and throat symptoms. • That’s 67% of the cases. • Of these 29, 72% report sore throat, 48% report sinus pain, and 14% report nose bleed. Gastro-Intestinal • 22 people reported GI symptoms. • That’s 51% of the cases. • Of these 22, 60% report nausea, 50% report abdominal pain, and 15% report diarrhea. Constitutional • 17 people reported constitutional symptoms. • That’s 39% of the cases. • Of these 17, 88% reported fatigue, 29% reported weakness, 18% reported weight change, and 12% reported drowsiness.

- 64. Number of PM2.5 Peaks and Symptom Type Eye, Ear, Nose, Throat Respiratory Neurological Stress GI Cardiological Number of Peaks Eye Irritation Tinnitis Dry- Mouth Nose bleed Throat irritation Cough SOB Wheezing Head ache Concentration Memory loss Dizziness Tingliness Numbness Anxiety/stress Sleep Issues Abdominal Pain Nausea Dyspnea /Dizziness Palpitations 62 X X X x 47 X X X X X X X X X X X X 44 X X X X X X X X X X x x X X X 42 X X X X X X X X 40 X X X X X X X X X X X X 35 X X X X X x x 24 X X X X x x 18 X X X X X 18 X X X X X X X X 17 X X X X X x X 16 X X X x 14 X X X x x 13 x x 9 X X X X x x 8 X X X X X x x 8 X X X X X x X 8 X x x 8 X x x 6 X x x

- 65. Related research on health Category Researcher/author Behavioral/mood /stress* SWPA (on-going) Earthworks (2012) Ferrar et al. (2013) Subra (2009) Perry (2013) Resick (2013) Birth Outcomes Hill (2012) McKenzie (2014) Cancer risk McKenzie (2012) Dermal* SWPA (on-going) Earthworks (2012) Subra (2009) Ear, nose, mouth, throat Earthworks (2012) Subra (2010) Subra (2009) Eye* SWPA (on-going) Earthworks (2012) Bamberger & Oswald (2012) Subra (2010) Subra (2009) Category Researcher/author Gastrointestinal Earthworks (2012) Bamberger & Oswald (2012) Ferrar et al. (2013) High Blood pressure Subra (2010) Muscle/joint pain* Earthworks (2012) Subra (2010) Subra (2009) Neurological* SWPA (on-going) Bamberger & Oswald (2012) Subra (2010) Subra (2009) Respiratory* SWPA (on-going) Earthworks (2012) Bamberger & Oswald (2012) Subra (2009)

- 66. References: • Michelle Bamberger and Robert E. Oswald, “Impacts of Gas Drilling on Human and Animal Health,” New Solutions 22(1): 51- 77, 2012. • Earthworks. Nadia Steinzor, Wilma Subra, and Lisa Sumi. Gas Patch Roulette, October 2012, http://www.earthworksaction.org/library/detail/gas_patch_roulette_full_report#.Uc3MAm11CVo, • KJ Ferrar, J Kriesky, CL Christen, LP Marshall, SL Malone, RK Sharma, DR Michanowicz, BD Goldstein, “Assessment and Longitudinal Analysis of Health Impacts and Stressors Perceived to Result from Unconventional Shale Gas Development in the Marcellus Shale Region,” International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 2013, Apr-Jun; 19(2):104-12. • Elaine L. Hill, “Working paper: Unconventional Gas Development and Infant Health: Evidence from Pennsylvania,” July 2012, The Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. • Lisa M. McKenzie, Roxana Z. Witter, Lee S. Newman, John L Adgate, “Human Health Risk Assessment of Air Emissions from Development of Unconventional Natural Gas Resources,” 2012, Science of the Total Environment, 424, 79-87. • Lisa M. McKenzie, Ruixin Guo, Roxana Z. Witter, David A. Savitz, Lee S. Newman, and John L. Adgate, Birth Outcomes and Maternal Residential Proximity to Natural Gas Development in Rural Colorado, Environmental Health Perspectives, Vo. 122, Issue 4, April 2014, • Simona L. Perry, “Using Ethnography to Monitor the Community Health Implications of Onshore Unconventional Oil and Gas Developments: Examples from Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale,” New Solutions, 2013, 23 (1), 33-54. • Lenore K. Resick, Joyce M. Knestrick, Mona M. Counts, Lindsay K Pizzuto, “The Meaning of Health among Mid-Appalachian Women within the Context of the Environment” Journal of Environmental Studies and Science, 2013, DOI 10.1007/s13412- 013-0119-y, published on-line, May • Wilma Subra, “Community Health Survey Results: Pavilion, WY Residents,” 2010. http://www.earthworksaction.org/files/publications/PavillionFINALhealthSurvey-201008.pdf • Wilma Subra, “Results of Health Survey of Current and Former DISH/Clark, Texas Residents” December 2009. Earthworks’ Oil and Gas Accountability Project, http://www.earthworksaction.org/files/publications/DishTXHealthSurvey_FINAL_hi.pdf

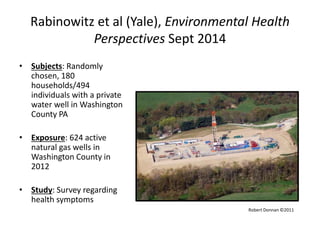

- 67. Rabinowitz et al (Yale), Environmental Health Perspectives Sept 2014 • Subjects: Randomly chosen, 180 households/494 individuals with a private water well in Washington County PA • Exposure: 624 active natural gas wells in Washington County in 2012 • Study: Survey regarding health symptoms Robert Donnan ©2011

- 68. Rabinowitz et al (Yale), Environmental Health Perspectives Sept 2014

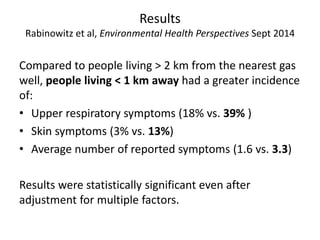

- 69. Results Rabinowitz et al, Environmental Health Perspectives Sept 2014 Compared to people living > 2 km from the nearest gas well, people living < 1 km away had a greater incidence of: • Upper respiratory symptoms (18% vs. 39% ) • Skin symptoms (3% vs. 13%) • Average number of reported symptoms (1.6 vs. 3.3) Results were statistically significant even after adjustment for multiple factors.

- 70. 2014 Birth Outcomes Study • Birth Outcomes and Maternal Residential Proximity to Natural Gas Development in Rural Colorado, Environmental Health Perspectives, Vo. 122, Issue 4, April 2014 • Lisa M. McKenzie, Ruixin Guo, Roxana Z. Witter, David A. Savitz, Lee S. Newman, and John L. Adgate

- 71. Conclusions • “In this large cohort, we observed an association between density and proximity of natural gas wells within a 10-mile radius of maternal residence and prevalence of congenital heart defects (CHDs) and possibly neural tube defects (NTDs). Greater specificity in exposure estimates are needed to further explore these associations.” http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/wp-content/uploads/122/1/ehp.1306722.pdf

- 72. Mckenzie et al. 2012 Study • Measured ambient air hydrocarbon emissions – 163 measurements from fixed monitoring station – 24 samples from perimeter of well pads (130-500 feet from center) undergoing well completion • Used EPA guidance to estimate non-cancer and cancer risks for residents living > 1/2 mile from wells and residents living < 1/2 mile from wells Colorado Shale Viewer 1:2,311,162 Content may not reflect National Geographic's current map policy. Sources: National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, HERE, UNEP-WCMC, USGS, NASA, CO_SPILLS_10162014_Buffer CO_DIR_WELLS_10142014_Buffer CO_PITS_10142014_Buffer1 CO_COUNTIES_10142014 CO_PLAYS_10142014 CO_BASINS_10142014 November 6, 2014 0 20 40 80 mi 0 30 60 120 km intern_ft © Copyright 2014 FracTracker Alliance

- 73. Conclusions from Mckenzie et al. Study • Residents closest to well pads have higher risks for respiratory and neurological effects based on their exposure to air pollutants. • Residents living close to natural gas well are at higher excess lifetime risk for cancer than residents who live farther from the wells. • Emissions measured by the fence line at well completion were statistically higher (p ≤ 0.05) than emissions at the fixed location station. These pollutants include benzene, toluene, and several alkanes.

- 74. Health Effects of UNGD Chemicals • Theo Colborn, the founder of TEDX, and her co-authors published a paper in 2010 Natural Gas Operations from a Public Health Perspective. • Colborn and her co-authors summarized health effect information for 353 chemicals used to drill and fracture natural gas wells in the United States. • Colborn’s paper provides a list of 71 particular fracturing chemicals that are associated with 10 or more health effects.

- 75. TEDX Findings • The four most common adverse health effects of the chemicals in the TEDX database are: • (1) neurotoxicity • (2) skin/sense organ toxicity • (3) respiratory problems • (4) gastrointestinal/liver damage

- 76. Conclusions: UNGD-related Potential Health Concerns • Both chemical and non-chemical exposures produced by gas drilling activities pose health risks to human and animal residents of gas production areas. • Rapid change resulting from introduction of gas drilling activities into rural communities carries risk of social disruption and mental health consequences.

- 77. Community and Social Impacts of Shale Gas Extraction in Pennsylvania SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT

- 78. • Disruption of daily routine by heavy truck traffic • Increased cost of living, especially higher rental housing costs • Higher incidence of crime • Heavy use of health and social services • More disputes between neighbors with differing opinions • Loss of “sense of place/community” • Contributions to communities by gas companies • Increased economic activity SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Social Impacts documented by social science researchers and journalists:

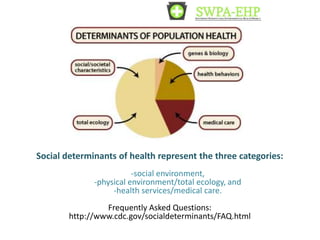

- 79. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Social determinants of health represent the three categories: -social environment, -physical environment/total ecology, and -health services/medical care. Frequently Asked Questions: http://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/FAQ.html 724.260.5504

- 80. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT What are social determinants of health? They are factors related to health outcomes which include: • How a person develops during the first few years of life • How much education a persons obtains • Being able to get and keep a job • What kind of work a person does • Having food or being able to get food (food security) • Having access to quality health services • Housing status • How much money a person earns • Discrimination and social support Frequently Asked Questions: http://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/FAQ.html 724.260.5504

- 81. Traffic SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Big trucks on small roads can create congestion, noise, dust, and odors even in sparsely populated areas Courtesy of: www.fractracker.org

- 82. Housing: Impact on Rental Availability & Price • The establishment of “man camps” for temporary workers • Higher rents (in some locations increases of 100% and more) • Those on “economic margins” increasing difficulty finding housing Photo: http://www.texassharon.com/2009/10/08/chesapeake-energy-brings-a-man-camp-to-marcellus-shale/ Source: MARCELLUS NATURAL GAS DEVELOPMENT’S EFFECT ON HOUSING IN PENNSYLVANIA (http://marcellus.psu.edu/resources/PDFs/housingreport.pdf) By J. Williamson and B. Kolb, Lycoming College SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT

- 83. 724.260.5504 Crime and Pressure on Community Social Services (many not yet measured and/or measureable) • Increased rates of crime • Drug and alcohol abuse • Sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) • Domestic violence SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT

- 84. Community Tensions SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT • “Haves” and “Have Nots” • “Old Timers” and “Newcomers” • Losing “Sense of Place or Community” http://ckilpatrick.weebly.com/thinker.html http://money.cnn.com/2011/05/09/news/eco nomy/natural_gas_fracking_duke/index.htm http://www.flickr.com/photos/29184238@N0 6/8488194752/

- 85. Economic Impacts Positive SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT • Job creation in shale gas industry now and in future • Job creation in “ancillary industries” • Income from leasing of mineral rights • Increased revenues for state and local governments Negative • Decrease in property values • Increase in rental housing costs • Losses experienced by non-related industries Photo courtesy of: http://naturalgasresourcecenter.com/tag/marcellus-shale-jobs/

- 86. Job Creation In 2013, the Multi-State Shale Research Collaborative, a joint effort of: • Pennsylvania Budget Policy Center, • Keystone Research Center (PA), • Fiscal Policy Institute in New York, • Policy Matters Ohio, • West Virginia Center on Budget & Policy, & • The Commonwealth Institute in Virginia Between 2005 and 2012, less than four new direct shale-related jobs have been created for each new well drilled, much less than estimates as high as 31 direct jobs per well in some industry-financed studies. http://www.multistateshale.org/shale-employment-report SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT

- 87. Job Creation (continued) SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Region-wide, shale-related employment accounts for just one out of every 794 jobs. By contrast, education and health sectors account for one out of every 6 jobs.

- 88. Job Creation (continued) Job growth in the industry has been greatest (as a share of total employment) in West Virginia. Still, shale-related employment is less than 1 percent of total West Virginia employment and less than half a percent of total employment in all the other states. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT

- 89. Income from Mineral Rights • Mineral rights owners collect – maybe as much as $1-2 million per well • Landowners save or invest about 55 percent of total leasing dollars within the year, rather than spending them immediately • They save or invest about 66 percent of all royalty dollars http://marcellus.psu.edu/resources/PDFs/Economic%20Impact%20of%20Marcellus%20Shale%202009.pdf Economic Impacts of Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania: Employment and Income in 2009 SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT

- 90. Income from Mineral Rights Journalist, Kevin Begos reported: SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Source: http://hosted.ap.org/dynamic/stories/U/US_GAS_ DRILLING_ROYALTIES?SITE=AP&SECTION=HOME& TEMPLATE=DEFAULT&CTIME=2013-01-27-17-43-51 “In Pennsylvania alone, royalty payments could top $1.2 billion for 2012, according to an Associated Press analysis that looked at state tax information, production records and estimates from the National Association of Royalty Owners.”

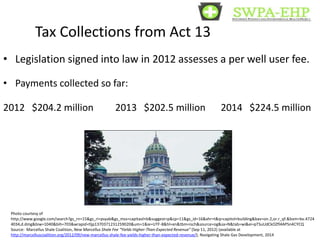

- 91. Tax Collections from Act 13 SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT • Legislation signed into law in 2012 assesses a per well user fee. • Payments collected so far: 2012 $204.2 million 2013 $202.5 million 2014 $224.5 million Photo courtesy of http://www.google.com/search?gs_rn=15&gs_ri=psyab&gs_mss=capitaol+b&suggest=p&cp=11&gs_id=16&xhr=t&q=capitol+building&bav=on.2,or.r_qf.&bvm=bv.4724 4034,d.dmg&biw=1040&bih=703&wrapid=tljp1370371231259020&um=1&ie=UTF-8&hl=en&tbm=isch&source=og&sa=N&tab=wi&ei=pTSuUdCkOZfl4AP5n4CYCQ Source: Marcellus Shale Coalition, New Marcellus Shale Fee “Yields Higher-Than-Expected Revenue” (Sep 11, 2012) (available at http://marcelluscoalition.org/2012/09/new-marcellus-shale-fee-yields-higher-than-expected-revenue/); Navigating Shale Gas Development, 2014

- 92. Influence on Property Values SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT • Concerns about groundwater risks associated with drilling "lead to a large and significant reduction in property values…“ • "These reductions offset any gains to the owners of groundwater-dependent properties from lease payments or improved local economic conditions, and may even lead to a net drop in prices.“ • Well drilling seems to have impacts on properties up to 2000 meters from a well -- more than a mile. • Property value decrease estimated at 23.6% if property depends on private drinking water wells. Photo courtesy of Shale Gas Development and Property Values, Differences across Drinking Water Sources, NBER Working Paper No. 18390, September 2012, http://www.nber.org/papers/w1839 Source: NBER Working Paper No. 18390, September 2012,http://www.nber.org/papers/w18390

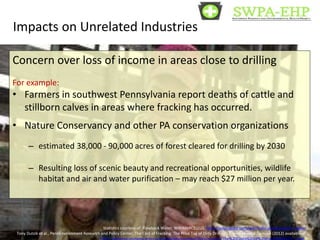

- 93. Impacts on Unrelated Industries SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Concern over loss of income in areas close to drilling For example: • Farmers in southwest Pennsylvania report deaths of cattle and stillborn calves in areas where fracking has occurred. • Nature Conservancy and other PA conservation organizations – estimated 38,000 - 90,000 acres of forest cleared for drilling by 2030 – Resulting loss of scenic beauty and recreational opportunities, wildlife habitat and air and water purification – may reach $27 million per year. Statistics courtesy of: Flowback Water, WIKIMARCELLUS, http://waytogoto.com/wiki/indix.php/Flowback_water Tony Dutzik et al., PennEnvironment Research and Policy Center, The Cost of Fracking: The Price Tag of Dirty Drilling's Environmental Damage (2012) available at http://penenvironmentcenter.org/sites/environment/files/reports/The%20Costs%20of%20Frackig%20vPA_0.pdf.

- 94. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Impacts on local infrastructure Degradation of roads through heavy use and overweight trucks occurs regularly in heavily drilled areas. Courtesy of: www.fractracker.org

- 95. Traffic-Related Costs to Communities Courtesy of: http://www.wcag-wv.org/A/Accidents/10-1223_Anthony/Anthony.htm SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT

- 96. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Social & Economic Impacts and Health These social determinants of health can contribute to: • Stress that directly impacts individuals’ health • Change in physical and social environments that indirectly contribute to health problems

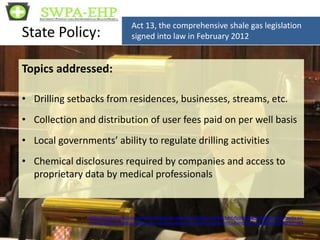

- 97. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT State Policy: Topics addressed: Act 13, the comprehensive shale gas legislation signed into law in February 2012 • Drilling setbacks from residences, businesses, streams, etc. • Collection and distribution of user fees paid on per well basis • Local governments’ ability to regulate drilling activities • Chemical disclosures required by companies and access to proprietary data by medical professionals Courtesy of: https://www.google.com/search?q=images+of+shale+gas+drilling+in+PA&client=firefox-a&hs=Oab&rls=org.mozilla:en- US:official&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=xOmsUZOFIerL0gHt7oHICA&ved=0CE4QsAQ&biw=1366&bih=664

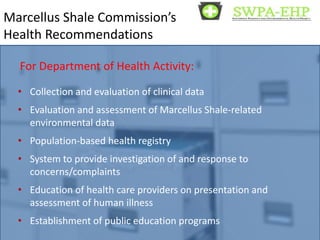

- 98. Marcellus Shale Commission’s Health Recommendations For Department of Health Activity: • Collection and evaluation of clinical data • Evaluation and assessment of Marcellus Shale-related environmental data • Population-based health registry • System to provide investigation of and response to concerns/complaints • Education of health care providers on presentation and assessment of human illness • Establishment of public education programs SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT

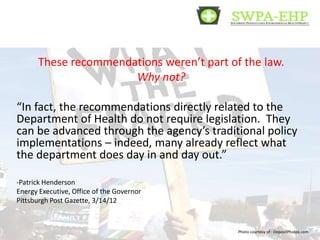

- 99. These recommendations weren’t part of the law. Photo courtesy of : DepositPhotos.com Why not? “In fact, the recommendations directly related to the Department of Health do not require legislation. They can be advanced through the agency’s traditional policy implementations – indeed, many already reflect what the department does day in and day out.” -Patrick Henderson Energy Executive, Office of the Governor Pittsburgh Post Gazette, 3/14/12 SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT

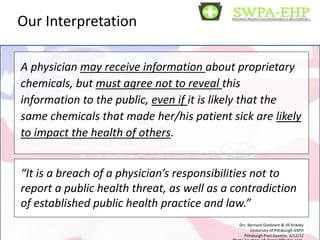

- 100. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT State Policy Act 13 Provisions Related to Health Courtesy of: DepositPhotos.com Hydraulic fracturing chemical disclosure requirements: • Limited availability of identity and amount of chemicals claimed to be confidential proprietary • Medical emergency disclosure to health professional upon verbal acknowledgment • Health professional provides written statement of need and confidentiality

- 101. Our Interpretation SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT A physician may receive information about proprietary chemicals, but must agree not to reveal this information to the public, even if it is likely that the same chemicals that made her/his patient sick are likely to impact the health of others. “It is a breach of a physician’s responsibilities not to report a public health threat, as well as a contradiction of established public health practice and law.” Drs. Bernard Goldstein & Jill Kriesky University of Pittsburgh GSPH Pittsburgh Post Gazette, 3/12/12 Photo Courtesy of: DepositPhotos.com

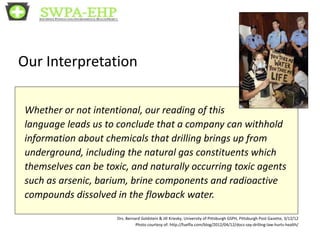

- 102. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Companies Responsibility to Report Section 3332.1(c)3: A vendor, service provider or operator shall not be required to… Disclose chemicals that may • occur incidentally • occur unintentionally in trace amounts • be incidental result of chemical reaction or chemical process • be constituents of naturally occurring materials Photo courtesy of: https://www.google.com/search?q=images+of+shale+gas+drilling+in+PA&client=firefox-a&hs=Oab&rls=org.mozilla:en- US:official&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=xOmsUZOFIerL0gHt7oHICA&ved=0CE4QsAQ&biw=1366&bih=664#client=firefox-a&rls=org.mozilla:en- US%3Aofficial&tbm=isch&sa=1&q=PROTEST+FRACKING&oq=PROTEST+FRACKING&gs_l=img.3..0i24.410999.414923.0.415254.16.11.0.5.5.0.66.486.11.11.0...0.0...1 c.1.15.img.s84Fqt20MKA&bav=on.2,or.r_qf.&bvm=bv.47244034,d.dmQ&fp=c6f2b15b3e959c13&biw=1307&bih=685

- 103. Our Interpretation Whether or not intentional, our reading of this language leads us to conclude that a company can withhold information about chemicals that drilling brings up from underground, including the natural gas constituents which themselves can be toxic, and naturally occurring toxic agents such as arsenic, barium, brine components and radioactive compounds dissolved in the flowback water. Drs. Bernard Goldstein & Jill Kriesky, University of Pittsburgh GSPH, Pittsburgh Post Gazette, 3/12/12 Photo courtesy of: http://fuelfix.com/blog/2012/04/12/docs-say-drilling-law-hurts-health/ SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT

- 104. www.environmentalhealthproject.org EHP Air and Water Monitoring Projects Ohio Environmental Council Raina Rippel SWPA EHP Director November 7, 2014

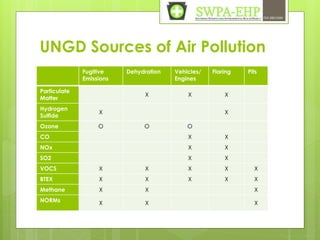

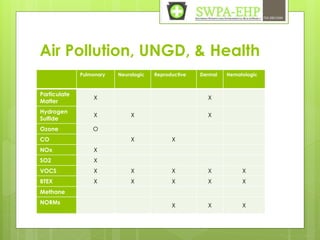

- 105. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT UNGD Sources of Air Pollution Fugitive Emissions Dehydration Vehicles/ Engines Flaring Pits Particulate Matter X X X Hydrogen Sulfide X X Ozone O O O CO X X NOx X X SO2 X X VOCS X X X X X BTEX X X X X X Methane X X X NORMs X X X 724.260.5504

- 106. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Air Pollution, UNGD, & Health Pulmonary Neurologic Reproductive Dermal Hematologic Particulate Matter X X Hydrogen Sulfide X X X Ozone O CO X X NOx X SO2 X VOCS X X X X X BTEX X X X X X Methane NORMs X X X 724.260.5504

- 107. The Speck Air Monitor: SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Developed by Carnegie Mellon University CREATE Lab in 2013 to continuously record particulate matter (PM2.5) levels 724.260.5504

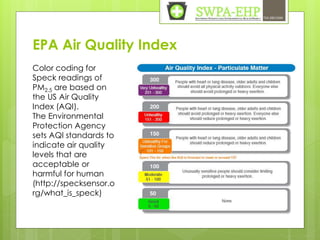

- 108. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 EPA Air Quality Index Color coding for Speck readings of PM2.5 are based on the US Air Quality Index (AQI). The Environmental Protection Agency sets AQI standards to indicate air quality levels that are acceptable or harmful for human (http://specksensor.o rg/what_is_speck)

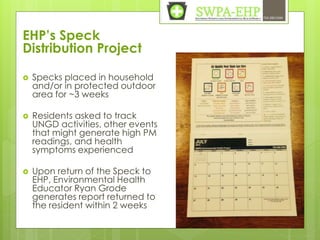

- 109. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 EHP’s Speck Distribution Project Specks placed in household and/or in protected outdoor area for ~3 weeks Residents asked to track UNGD activities, other events that might generate high PM readings, and health symptoms experienced Upon return of the Speck to EHP, Environmental Health Educator Ryan Grode generates report returned to the resident within 2 weeks

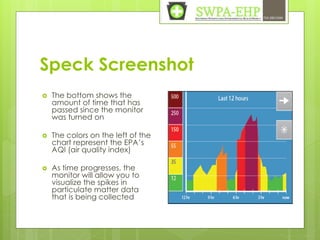

- 110. Speck Screenshot The bottom shows the amount of time that has passed since the monitor was turned on The colors on the left of the chart represent the EPA’s AQI (air quality index) As time progresses, the monitor will allow you to visualize the spikes in particulate matter data that is being collected SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504

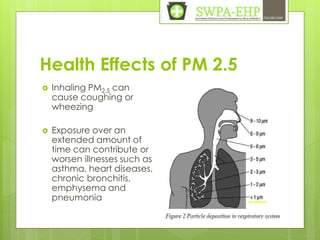

- 111. Health Effects of PM 2.5 Inhaling PM2.5 can cause coughing or wheezing Exposure over an extended amount of time can contribute or worsen illnesses such as asthma, heart diseases, chronic bronchitis, emphysema and pneumonia SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504

- 112. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Air Pollution and Health 724.260.5504

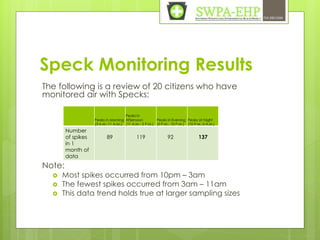

- 113. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Speck Monitoring Results The following is a review of 20 citizens who have monitored air with Specks: Note: Most spikes occurred from 10pm – 3am The fewest spikes occurred from 3am – 11am This data trend holds true at larger sampling sizes 724.260.5504 Peaks in Morning (3 A.M.-11 A.M.) Peaks in Afternoon (11 A.M.- 5 P.M.) Peaks in Evening (5 P.M.- 10 P.M.) Peaks at Night (10 P.M.-3 A.M.) Number of spikes in 1 month of data 89 119 92 137

- 114. How’s the Weather? SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT EHP has designed an air exposure model called ‘How’s The 724.260.5504 Weather’ that is available to the public. The model is used to determine exposure levels throughout the day based upon weather patterns. The ‘How’s the Weather’ program is often used alongside Speck monitoring to predict ahead of time if the results will be high or low.

- 115. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Water-related Concerns UNGD-related water exposures are less predictable than air. Potential for drinking water contamination from: Chemicals (Man-made and natural) Radioactivity Microbes 724.260.5504

- 116. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 The CATTFish Water Monitor: Developed by Carnegie Mellon University CREATE Lab in 2013 to record conductivity and temperature levels each time a reset button is pushed.

- 117. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 EHP CATTFish Distribution Project: Sixty monitors distributed in Washington County, PA, in collaboration with the Washington County Watershed Association in 2013-14; Process for recording data, receiving reports on results similar to that for Specks described above; EHP has additional 40 CATTFish to distribute now. NEITHER THE CATTFISH NOR SPECK PROVIDE DATA ON SPECIFIC CONTAMINANTS, BUT INDICATE WHEN FURTHER TESTING AND/OR ACTION MAY BE NEEDED!

- 118. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 What about food/soil? Robert Donnan

- 119. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Next Steps for EHP: Health intakes Continue intakes possibly in expanded region; Analyze aggregate results with monitoring results to understand exposures relation to symptoms better Air and water monitoring Continue providing Specks and CATTFish possibly in expanded region; Analyze aggregate results to better describe exposures

- 120. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 More next steps for EHP: Help residents cope with environmental changes; Educate health care professionals about health symptoms and potential causes; and Provide community-based organizations with health-related information to advocate for policy changes.

- 121. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 EHP’s Academic Partnerships Academic internships Collaboration or support for academic research projects

- 122. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Semester-, summer-, and year-long graduate and undergraduate internships Why? Leverage our funding; Tap into expertise not represented on EHP team; Prepare UNGD researchers of the future; Become acquainted with future research partners.

- 123. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Semester-, summer-, and year-long graduate and undergraduate internships (continued) What do they do? Assist with program development & delivery Air Modeling Train-the-trainer (2013) Take Steps to Health (2013-14) Conduct literature reviews for future program development & publications Soil contamination lit review (2014) International journal lit review on air contamination(2014)

- 124. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Semester-, summer-, and year-long graduate and undergraduate internships (continued) What do they do? Data analysis CATTFish water quality data analysis (2014) Health intake data analysis (current) Program evaluation Speck usage interviews and survey (2014) Tracking & analysis of inquiries to EHP (2013-current)

- 125. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Semester-, summer-, and year-long graduate and undergraduate internships (continued) Who are they? University of Pittsburgh – School of Social Work (2) University of Pittsburgh –School of Public Health(2) Carlow University – School of Nursing Chatham University – School of Sustainability West Virginia University – School of Public Health Northeastern University – Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute University of Pittsburgh, Johnstown – undergraduate Wheeling Jesuit University -- undergraduate

- 126. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT EHP Collaboration and/or Support for Academic Research Projects 724.260.5504 Why? Interest in advancing knowledge about UNGD health effects; Opportunity to influence the focus of research; Alternative methods or types of data collected & analyzed.

- 127. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 EHP Collaboration or Support for Academic Research (continued) What projects? Air, water, health survey data collection & analysis Yale University Washington County study (2012) University of Pittsburgh pilot project (2013) University of Washington/Yale Exposure Response pilot (2014) Noise Indiana University – Pennsylvania study (2014)

- 128. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 EHP Collaboration or Support for Academic Research (continued) What are the challenges? Research fatigue; Treatment as “research subjects”; Failure to provide timely results; Focus on publications over immediate needs of community.

- 129. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 EHP’s Community Partnerships What projects? Community education; Health care provider education; Low-cost air and water monitoring; Information for advocacy.

- 130. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 EHP’s Community Partnerships Why? Our two-way connection to local communities Our links to the national community of interest Similar projects & data collection efforts

- 131. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Promising Community Collaborations (continued) Community Education Community at large League of Women Voters (LWV) annual meetings Wellness and Water Coalition (WV) annual meetings Local impacted communities Villa Maria Retreat Center and town meeting Wheeling Jesuit University Appalachian Institute community meeting

- 132. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Community Partnerships Health Care Provider Education Physicians, Scientists and Engineers for Healthy Energy (PSE) on-line CME sessions (2012); Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments (ANHE) mid- Atlantic meetings (2013); Washington County Medical Society (2014); Ohio Environmental Council (today!).

- 133. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Community Partnerships Low-cost water and air monitoring Washington County Watershed Alliance CATTFish dissemination project (2013-14); Marcellus Outreach-Butler, Mountain Watershed Alliance and FracTracker West Virginia assistance with distribution of Speck air monitors; Earthworks collaboration on analysis of air emissions data; Global Community Monitor, Public Lab and Louisiana Bucket Brigade Community-based Science for Action Conference.

- 134. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT 724.260.5504 Community Partnerships Information for advocacy “Human Health Impacts of Marcellus Shale Gas Extraction: Where Do They Come From?” at PowerShift national conference, 2013; “How the Fracking Industry Impacts our Water, Air, Food Supply, and Children’s Health” for Beaver County Marcellus Awareness Public Forum, 2014; Research work group participation for Protect Our Children Coalition, ongoing; Research support for the Mars and Fort Cherry Parent groups, ongoing.

- 135. SOUTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT Where to go for more information:

Editor's Notes

- Introduce self Here today to talk briefly about the OEC’s concerns and advocacy work surrounding shale gas development, also know as horizontal hydraulic fracturing or fracking for short.

- So now I’d like to provide just a bit of background on the scale of the industry and the general environmental risks associated with it, before we jump into some of the risks and concerns specific to Ohio. First, many of you have probably been exposed to this map of the shale deposits throughout the US.

- This map from a recent Columbus Dispatch article by Spencer Hunt also provides a nice visual of where the majority of wells are in Ohio, most concentrated in Carroll, Columbiana and Jefferson Counties (can add a note here about how many wells are permitted in the county in which you are presenting)

- As with any industrial activity, the development of oil and gas involves risks to air, land, water, wildlife and communities. Many of you have probably seen these sorts of images depicting the new combination of horizontal drilling with hydraulic fracturing, or the use of sand, water, and chemicals injected at high pressures to blast open the shale rock and release the trapped gas. What industry will argue is that this technology has been around for 40 years. But that is not correct. While the use of hydraulic fracturing to drill vertical wells has been around that long, using the technique of hydraulic fracturing combined with horizontal drilling is very new and only began in 2011 in Ohio.

- This map from a recent Columbus Dispatch article by Spencer Hunt also provides a nice visual of where the majority of wells are in Ohio, most concentrated in Carroll, Columbiana and Jefferson Counties (can add a note here about how many wells are permitted in the county in which you are presenting)

- I want to speak briefly to general environmental concerns associated with fracking. First is the potential for water contamination, which could occur as a result of surface levels spills and accidents or through the migration of chemicals or methane. Jut a few highlights from the literature and news: a recent Cornell University study connected the death of over 100 cattle to exposure to fracking fluids. A Duke University study found methane concentrations 17x higher in drinking water wells within 1 km of fracking and shale gas extraction. Finally, Bob Downing with the Akron Beacon Journal conducted an investigation which found 1 million pounds of chemicals used at a single well site. (Industry claims that it’s no problem, because chemicals are only 1% of the solution. But how much is 1% of 5-7 million gallons? IT is 50,000 – 70,000 gallons of chemicals. Moreover, drillers are not currently required to reveal all of the chemicals contained in those products. )

- In terms of air quality and air pollution, it is not a matter of “if” air emissions will occur, as they most certainly will occur. Averages from PA & WV show that it’s not uncommon for all stages of production to burn 29,000 gallons of diesel fuel in approximately 5 days. And diesel exhaust includes many harsh emissions such as benzene, formaldyhyde and 40 other toxins. Colorado school of public health engaged in a health impact assessment around air emissions from fracking in Colorado and Earthworks oil and gas accountability project has recently put together a health survey of citizens living near shale gas development sites in Pennsylvania. The findings from both reports are very concerning. (option to add additional slide in the future).

- Also, most folks are probably aware of the series of earthquakes that occurred in Youngstown, Ohio, including a 4.0 magnitude earthquake on New Year’s Eve 2011, which was linked to the disposal of fracking fluids at nearby waste injection well. As a result of these quakes, the ODNR has issued a series of reforms to brine injection well regulations.

- Even with few producing wells in the state of Ohio, incidents have already cropped up. The OEC assisted a gentleman in Harrison county in submitting a verified complain to the Ohio EPA regarding a white substance which was running out of an underground spring down the hill 75 ft. below the Dodson Well Pad. Two state regulatory agencies, plus the US EPA, are conducting remediation of over 200,000 gallons of brine (fracking waste) that were dumped into a storm drain which empties into the Mahoning River in Youngstown, Ohio (article date: Feb 6, 2013). A criminal investigation is also underway. And finally, we were made aware of “frack outs” or releases of bentonite clay slurry by Mark West Company during pipeline drilling in Harrison County. These frack outs caused clay slurry to accumulate in streams and wetlands, smothering out macroinvertebrates and negatively affecting aquatic life.

- Even with few producing wells in the state of Ohio, incidents have already cropped up. The OEC assisted a gentleman in Harrison county in submitting a verified complain to the Ohio EPA regarding a white substance which was running out of an underground spring down the hill 75 ft. below the Dodson Well Pad. Two state regulatory agencies, plus the US EPA, are conducting remediation of over 200,000 gallons of brine (fracking waste) that were dumped into a storm drain which empties into the Mahoning River in Youngstown, Ohio (article date: Feb 6, 2013). A criminal investigation is also underway. And finally, we were made aware of “frack outs” or releases of bentonite clay slurry by Mark West Company during pipeline drilling in Harrison County. These frack outs caused clay slurry to accumulate in streams and wetlands, smothering out macroinvertebrates and negatively affecting aquatic life.

- Halliburton delayed releasing details on fracking chemicals after Monroe County spill By Laura Arenschield The Columbus Dispatch • Monday July 21, 2014 5:16 AM A fracking company made federal and state agencies that oversee drinking-water safety wait days before it shared a list of toxic chemicals that spilled from a drilling site into a tributary of the Ohio River. Although the spill following a fire on June 28 at the Statoil North America well pad in Monroe County stretched 5 miles along the creek and killed more than 70,000 fish and wildlife, state officials said they do not believe drinking water was affected. But environmental advocacy groups said they wonder how the state can be sure. A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency report obtained by The Dispatch shows that the federal and state EPA officials had to wait five days before they were given a full list of the fracking chemicals the drilling company used at the site. Halliburton, the company hired by Statoil to frack the horizontal well, provided a partial list up front that included most of the chemicals. Others, which are protected by Ohio’s trade-secrets law, were omitted. “How can communities know that they are being protected when an incident like this happens?” said Teresa Mills, an environmental activist and Ohio organizer with the Center for Health, Environment and Justice. “We need more transparent laws.” To pull oil and natural gas from shale, companies drill vertically and then turn sideways into the rock. Then they blast millions of gallons of water, sand and chemicals into the shafts to free trapped oil and gas in the process called fracking. During the process, fluids bubble back up to the surface with the gas. Once a fracking job is finished, drilling companies have 60 days to disclose what chemicals they used to the Department of Natural Resources, which oversees drilling and fracking operations in Ohio. Ohio law says that companies have to disclose the contents of proprietary fracking mixes only to firefighters or Natural Resources if there is an emergency, such as fires or spills. In this case, both were given the full list but did not share the details with other agencies. Halliburton has yet to finish fracking the Monroe County well that caught fire. Chris Abbruzzese, an Ohio EPA spokesman, said that on the day of the fire and spill, a representative from a group that represents the federal and state EPA offices, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources and Monroe County emergency management and fire workers asked Statoil and Halliburton for a list of the chemicals. “Once they realized that the proprietary information wasn’t included, there were additional (requests) made,” Abbruzzese said. Natural Resources, which regulates drilling in Ohio, has authority under state law to see the entire list and asked on its own two days after the fire. Halliburton, the company hired by Statoil to frack the well, gave the list to the single agency. But Natural Resources did not share that information with either EPA office. “Internal communication is something we’re going to work on,” said Bethany McCorkle, a Natural Resources spokeswoman. Kirsten Henriksen, a spokeswoman for Statoil, said the company hired an outside toxicology firm to test both the creek and the Ohio River for toxic chemicals. None were found in the Ohio River, she said. The Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission, a multi-state agency that tests the river, also found no contaminants. “Based on the chemicals that we were aware of, if there had been any other chemicals that would have been there, they all would have showed up (in tests),” Abbruzzese said. Kelly Scribner, a toxicologist with the Center for Toxicology and Environmental Health, which was hired by Statoil to perform the tests, said she wasn’t given a full list of chemicals either. But, she said, the tests would have shown abnormalities in the water either way. Fracking chemicals include ethylene glycol, which can damage kidneys; formaldehyde, a known cancer risk; and naphthalene, considered a possible carcinogen. The water tests showed elevated levels of chlorides, salt and acetone in the creek near the well pad. By the time federal and state EPA officials were given the full list, those chemicals likely flowed past towns along the Ohio River that draw in drinking water. That worries some state lawmakers and environmental advocacy groups. “We’ve got 70,000 or so fish that died,” said Nathan Johnson, an attorney for the Ohio Environmental Council. “Clearly, something was wrong with the water.” The group has been lobbying the Ohio legislature to pass laws that would force companies during emergencies to immediately disclose the full list of chemicals to all state agencies. Oil and gas industry officials and regulators have pushed back against additional regulations, saying Ohio’s laws are more than adequate to protect people. In a speech on Tuesday outside Mansfield, Gov. John Kasich said Ohio has “very tough regulations” concerning fracking. “If the accidents happen, and we’re not minding the store, or we’re looking the other way, that would be a disaster for us,” he said. Kasich told The Dispatch it would be unacceptable for emergency responders, including federal and Ohio EPA officials, not to know the full list of chemicals that might have spilled into the river. “We want people to know what the fracking fluid contains,” he said. Other states, including Pennsylvania and Texas, make companies disclose the full list of chemicals within 30 days of wrapping up a fracking operation. In Oklahoma, they must disclose the chemicals to state regulators before a well is drilled. The Statoil fire started on the morning of June 28 when, according to preliminary reports, a hydraulic line used during the fracking process broke. The broken line sprayed fracking fluid onto hot equipment, igniting it. The fire spread to 20 trucks, which went up in flames. No workers were hurt, but one firefighter was treated for smoke inhalation. About 25 people who live near the wells were evacuated. The fire continued to smolder for six days. As it burned, firefighters doused it with water and foam, washing chemicals from the site into the tributary, which flows for five miles before reaching the Ohio River. Legislators and environmental groups say the Statoil fire illustrates a gap in the law that allows fracking companies to determine when they release information and to whom. “It is a huge problem,” said Johnson, the Ohio Environmental Council attorney. “We’re essentially at the behest of the company with the chemical information.” Dispatch Public Affairs Editor Darrel Rowland contributed to this story.

- According to Paul Feezel, Chair of Carroll Concerned Citizens, who resides in the hotbed of shale gas activity in Ohio, local impacts range from water threats to a 100 Percent increase in traffic accidents to local renters being priced out of their rental units. Carroll County's water specifically is under a triple threat from shale gas water extraction, massive volumes of hydraulic fracturing chemicals, and disposal needs for waste fluids. Unfortunately Carroll county is also currently seeing a resurgence in underground coal mining.

- Some of the major provisions for the bill will include greater protections of public water sources and floodplains, a requirement for increased air monitoring, and improving the public’s right to know and right to appeal permit terms and conditions. We also hope to include language requiring additional inspectors and better reporting and tracking of shale gas incidents and accidents on ODNR’s website. Finally, there will be language requiring waste fluid recycling and reuse and increased protections for disposal of waste materials.

- We are very concerned because Ohio’s state lands and its largest tract of federal land – the Wayne National Forest - are now open to drilling + logging. Quail Hollow State Park in Stark County was the first to be targeted. A small portion of the park was recently pulled into a drilling unit through Ohio’s unitization laws. And in Aug 2012, the park supervisor at Wayne National Forest announced that land could be leased for up to 13 drilling sites in the national forest.

- -Gov’s energy bill: Passed in May 2012; Signed into law by the Governor, June 2012. Some good, some bad, & some ugly provisions. OEC began as interested party, but ended up opposing SB 315 due to an industry amendment & watering down of the bill. (There is an extensive press release covering the major provisions of this bill in your folders) -SB 46: State Senators Schiavoni (D) and LaRose (R) introduced senate bill 46 in the 2013 general assembly, as a response to the brine dumping incident in Youngstown, Ohio. This bill was a scarlet letter bill of sorts, proposing that the ODNR should permanently revoke permits from companies which intentionally or repeatedly commit violations of Ohio’s laws, and prohibit these violators from getting another permit in this state.. -Budget bill: Some of the significant changes included: Good: -Precludes brine that is produced from a horizontal well from being allowed to be spread on a roads -Calls for ODNR to develop a number of additional rules/regulations for horizontal drilling including rules around recycling, treatment and processing of brine, among other things. Bad: -Provisions regarding the disposal of solid waste materials, including radioactive materials, were not nearly as stringent as we would have liked (for example, definition of TENORM, or technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material outdated definition which will not include drill cuttings or brine in testing requirements), did not prohibit Centralized Treatment Facilities (+grandfathered in Patriot treatment facility)

- -Gov’s energy bill: Passed in May 2012; Signed into law by the Governor, June 2012. Some good, some bad, & some ugly provisions. OEC began as interested party, but ended up opposing SB 315 due to an industry amendment & watering down of the bill. (There is an extensive press release covering the major provisions of this bill in your folders) -SB 46: State Senators Schiavoni (D) and LaRose (R) introduced senate bill 46 in the 2013 general assembly, as a response to the brine dumping incident in Youngstown, Ohio. This bill was a scarlet letter bill of sorts, proposing that the ODNR should permanently revoke permits from companies which intentionally or repeatedly commit violations of Ohio’s laws, and prohibit these violators from getting another permit in this state.. -Budget bill: Some of the significant changes included: Good: -Precludes brine that is produced from a horizontal well from being allowed to be spread on a roads -Calls for ODNR to develop a number of additional rules/regulations for horizontal drilling including rules around recycling, treatment and processing of brine, among other things. Bad: -Provisions regarding the disposal of solid waste materials, including radioactive materials, were not nearly as stringent as we would have liked (for example, definition of TENORM, or technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material outdated definition which will not include drill cuttings or brine in testing requirements), did not prohibit Centralized Treatment Facilities (+grandfathered in Patriot treatment facility)

- -Gov’s energy bill: Passed in May 2012; Signed into law by the Governor, June 2012. Some good, some bad, & some ugly provisions. OEC began as interested party, but ended up opposing SB 315 due to an industry amendment & watering down of the bill. (There is an extensive press release covering the major provisions of this bill in your folders) -SB 46: State Senators Schiavoni (D) and LaRose (R) introduced senate bill 46 in the 2013 general assembly, as a response to the brine dumping incident in Youngstown, Ohio. This bill was a scarlet letter bill of sorts, proposing that the ODNR should permanently revoke permits from companies which intentionally or repeatedly commit violations of Ohio’s laws, and prohibit these violators from getting another permit in this state.. -Budget bill: Some of the significant changes included: Good: -Precludes brine that is produced from a horizontal well from being allowed to be spread on a roads -Calls for ODNR to develop a number of additional rules/regulations for horizontal drilling including rules around recycling, treatment and processing of brine, among other things. Bad: -Provisions regarding the disposal of solid waste materials, including radioactive materials, were not nearly as stringent as we would have liked (for example, definition of TENORM, or technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material outdated definition which will not include drill cuttings or brine in testing requirements), did not prohibit Centralized Treatment Facilities (+grandfathered in Patriot treatment facility)

- If you’d simply like to learn more about this issue, I am happy to provide you with additional resources,

- We are very concerned because Ohio’s state lands and its largest tract of federal land – the Wayne National Forest - are now open to drilling + logging. Quail Hollow State Park in Stark County was the first to be targeted. A small portion of the park was recently pulled into a drilling unit through Ohio’s unitization laws. And in Aug 2012, the park supervisor at Wayne National Forest announced that land could be leased for up to 13 drilling sites in the national forest.

- We are very concerned because Ohio’s state lands and its largest tract of federal land – the Wayne National Forest - are now open to drilling + logging. Quail Hollow State Park in Stark County was the first to be targeted. A small portion of the park was recently pulled into a drilling unit through Ohio’s unitization laws. And in Aug 2012, the park supervisor at Wayne National Forest announced that land could be leased for up to 13 drilling sites in the national forest.

- Introduce self Here today to talk briefly about the OEC’s concerns and advocacy work surrounding shale gas development, also know as horizontal hydraulic fracturing or fracking for short.

- Introduce self Here today to talk briefly about the OEC’s concerns and advocacy work surrounding shale gas development, also know as horizontal hydraulic fracturing or fracking for short.

- Introduce self Here today to talk briefly about the OEC’s concerns and advocacy work surrounding shale gas development, also know as horizontal hydraulic fracturing or fracking for short.

- This map from a recent Columbus Dispatch article by Spencer Hunt also provides a nice visual of where the majority of wells are in Ohio, most concentrated in Carroll, Columbiana and Jefferson Counties (can add a note here about how many wells are permitted in the county in which you are presenting)

- As with any industrial activity, the development of oil and gas involves risks to air, land, water, wildlife and communities. Many of you have probably seen these sorts of images depicting the new combination of horizontal drilling with hydraulic fracturing, or the use of sand, water, and chemicals injected at high pressures to blast open the shale rock and release the trapped gas. What industry will argue is that this technology has been around for 40 years. But that is not correct. While the use of hydraulic fracturing to drill vertical wells has been around that long, using the technique of hydraulic fracturing combined with horizontal drilling is very new and only began in 2011 in Ohio.

- Also, most folks are probably aware of the series of earthquakes that occurred in Youngstown, Ohio, including a 4.0 magnitude earthquake on New Year’s Eve 2011, which was linked to the disposal of fracking fluids at nearby waste injection well. As a result of these quakes, the ODNR has issued a series of reforms to brine injection well regulations.

- Even with few producing wells in the state of Ohio, incidents have already cropped up. The OEC assisted a gentleman in Harrison county in submitting a verified complain to the Ohio EPA regarding a white substance which was running out of an underground spring down the hill 75 ft. below the Dodson Well Pad. Two state regulatory agencies, plus the US EPA, are conducting remediation of over 200,000 gallons of brine (fracking waste) that were dumped into a storm drain which empties into the Mahoning River in Youngstown, Ohio (article date: Feb 6, 2013). A criminal investigation is also underway. And finally, we were made aware of “frack outs” or releases of bentonite clay slurry by Mark West Company during pipeline drilling in Harrison County. These frack outs caused clay slurry to accumulate in streams and wetlands, smothering out macroinvertebrates and negatively affecting aquatic life.

- Even with few producing wells in the state of Ohio, incidents have already cropped up. The OEC assisted a gentleman in Harrison county in submitting a verified complain to the Ohio EPA regarding a white substance which was running out of an underground spring down the hill 75 ft. below the Dodson Well Pad. Two state regulatory agencies, plus the US EPA, are conducting remediation of over 200,000 gallons of brine (fracking waste) that were dumped into a storm drain which empties into the Mahoning River in Youngstown, Ohio (article date: Feb 6, 2013). A criminal investigation is also underway. And finally, we were made aware of “frack outs” or releases of bentonite clay slurry by Mark West Company during pipeline drilling in Harrison County. These frack outs caused clay slurry to accumulate in streams and wetlands, smothering out macroinvertebrates and negatively affecting aquatic life.

- Halliburton delayed releasing details on fracking chemicals after Monroe County spill By Laura Arenschield The Columbus Dispatch • Monday July 21, 2014 5:16 AM A fracking company made federal and state agencies that oversee drinking-water safety wait days before it shared a list of toxic chemicals that spilled from a drilling site into a tributary of the Ohio River. Although the spill following a fire on June 28 at the Statoil North America well pad in Monroe County stretched 5 miles along the creek and killed more than 70,000 fish and wildlife, state officials said they do not believe drinking water was affected. But environmental advocacy groups said they wonder how the state can be sure. A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency report obtained by The Dispatch shows that the federal and state EPA officials had to wait five days before they were given a full list of the fracking chemicals the drilling company used at the site. Halliburton, the company hired by Statoil to frack the horizontal well, provided a partial list up front that included most of the chemicals. Others, which are protected by Ohio’s trade-secrets law, were omitted. “How can communities know that they are being protected when an incident like this happens?” said Teresa Mills, an environmental activist and Ohio organizer with the Center for Health, Environment and Justice. “We need more transparent laws.” To pull oil and natural gas from shale, companies drill vertically and then turn sideways into the rock. Then they blast millions of gallons of water, sand and chemicals into the shafts to free trapped oil and gas in the process called fracking. During the process, fluids bubble back up to the surface with the gas. Once a fracking job is finished, drilling companies have 60 days to disclose what chemicals they used to the Department of Natural Resources, which oversees drilling and fracking operations in Ohio. Ohio law says that companies have to disclose the contents of proprietary fracking mixes only to firefighters or Natural Resources if there is an emergency, such as fires or spills. In this case, both were given the full list but did not share the details with other agencies. Halliburton has yet to finish fracking the Monroe County well that caught fire. Chris Abbruzzese, an Ohio EPA spokesman, said that on the day of the fire and spill, a representative from a group that represents the federal and state EPA offices, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources and Monroe County emergency management and fire workers asked Statoil and Halliburton for a list of the chemicals. “Once they realized that the proprietary information wasn’t included, there were additional (requests) made,” Abbruzzese said. Natural Resources, which regulates drilling in Ohio, has authority under state law to see the entire list and asked on its own two days after the fire. Halliburton, the company hired by Statoil to frack the well, gave the list to the single agency. But Natural Resources did not share that information with either EPA office. “Internal communication is something we’re going to work on,” said Bethany McCorkle, a Natural Resources spokeswoman. Kirsten Henriksen, a spokeswoman for Statoil, said the company hired an outside toxicology firm to test both the creek and the Ohio River for toxic chemicals. None were found in the Ohio River, she said. The Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission, a multi-state agency that tests the river, also found no contaminants. “Based on the chemicals that we were aware of, if there had been any other chemicals that would have been there, they all would have showed up (in tests),” Abbruzzese said. Kelly Scribner, a toxicologist with the Center for Toxicology and Environmental Health, which was hired by Statoil to perform the tests, said she wasn’t given a full list of chemicals either. But, she said, the tests would have shown abnormalities in the water either way. Fracking chemicals include ethylene glycol, which can damage kidneys; formaldehyde, a known cancer risk; and naphthalene, considered a possible carcinogen. The water tests showed elevated levels of chlorides, salt and acetone in the creek near the well pad. By the time federal and state EPA officials were given the full list, those chemicals likely flowed past towns along the Ohio River that draw in drinking water. That worries some state lawmakers and environmental advocacy groups. “We’ve got 70,000 or so fish that died,” said Nathan Johnson, an attorney for the Ohio Environmental Council. “Clearly, something was wrong with the water.” The group has been lobbying the Ohio legislature to pass laws that would force companies during emergencies to immediately disclose the full list of chemicals to all state agencies. Oil and gas industry officials and regulators have pushed back against additional regulations, saying Ohio’s laws are more than adequate to protect people. In a speech on Tuesday outside Mansfield, Gov. John Kasich said Ohio has “very tough regulations” concerning fracking. “If the accidents happen, and we’re not minding the store, or we’re looking the other way, that would be a disaster for us,” he said. Kasich told The Dispatch it would be unacceptable for emergency responders, including federal and Ohio EPA officials, not to know the full list of chemicals that might have spilled into the river. “We want people to know what the fracking fluid contains,” he said. Other states, including Pennsylvania and Texas, make companies disclose the full list of chemicals within 30 days of wrapping up a fracking operation. In Oklahoma, they must disclose the chemicals to state regulators before a well is drilled. The Statoil fire started on the morning of June 28 when, according to preliminary reports, a hydraulic line used during the fracking process broke. The broken line sprayed fracking fluid onto hot equipment, igniting it. The fire spread to 20 trucks, which went up in flames. No workers were hurt, but one firefighter was treated for smoke inhalation. About 25 people who live near the wells were evacuated. The fire continued to smolder for six days. As it burned, firefighters doused it with water and foam, washing chemicals from the site into the tributary, which flows for five miles before reaching the Ohio River. Legislators and environmental groups say the Statoil fire illustrates a gap in the law that allows fracking companies to determine when they release information and to whom. “It is a huge problem,” said Johnson, the Ohio Environmental Council attorney. “We’re essentially at the behest of the company with the chemical information.” Dispatch Public Affairs Editor Darrel Rowland contributed to this story.

- According to Paul Feezel, Chair of Carroll Concerned Citizens, who resides in the hotbed of shale gas activity in Ohio, local impacts range from water threats to a 100 Percent increase in traffic accidents to local renters being priced out of their rental units. Carroll County's water specifically is under a triple threat from shale gas water extraction, massive volumes of hydraulic fracturing chemicals, and disposal needs for waste fluids. Unfortunately Carroll county is also currently seeing a resurgence in underground coal mining.

- Some of the major provisions for the bill will include greater protections of public water sources and floodplains, a requirement for increased air monitoring, and improving the public’s right to know and right to appeal permit terms and conditions. We also hope to include language requiring additional inspectors and better reporting and tracking of shale gas incidents and accidents on ODNR’s website. Finally, there will be language requiring waste fluid recycling and reuse and increased protections for disposal of waste materials.

- We are very concerned because Ohio’s state lands and its largest tract of federal land – the Wayne National Forest - are now open to drilling + logging. Quail Hollow State Park in Stark County was the first to be targeted. A small portion of the park was recently pulled into a drilling unit through Ohio’s unitization laws. And in Aug 2012, the park supervisor at Wayne National Forest announced that land could be leased for up to 13 drilling sites in the national forest.

- -Gov’s energy bill: Passed in May 2012; Signed into law by the Governor, June 2012. Some good, some bad, & some ugly provisions. OEC began as interested party, but ended up opposing SB 315 due to an industry amendment & watering down of the bill. (There is an extensive press release covering the major provisions of this bill in your folders) -SB 46: State Senators Schiavoni (D) and LaRose (R) introduced senate bill 46 in the 2013 general assembly, as a response to the brine dumping incident in Youngstown, Ohio. This bill was a scarlet letter bill of sorts, proposing that the ODNR should permanently revoke permits from companies which intentionally or repeatedly commit violations of Ohio’s laws, and prohibit these violators from getting another permit in this state.. -Budget bill: Some of the significant changes included: Good: -Precludes brine that is produced from a horizontal well from being allowed to be spread on a roads -Calls for ODNR to develop a number of additional rules/regulations for horizontal drilling including rules around recycling, treatment and processing of brine, among other things. Bad: -Provisions regarding the disposal of solid waste materials, including radioactive materials, were not nearly as stringent as we would have liked (for example, definition of TENORM, or technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material outdated definition which will not include drill cuttings or brine in testing requirements), did not prohibit Centralized Treatment Facilities (+grandfathered in Patriot treatment facility)