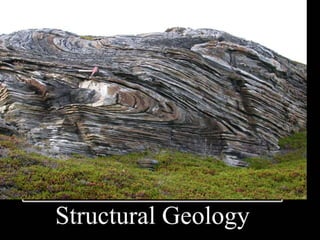

Structural Geology Folds

- 2. What is Structural Geology? •Structural geology is the study of the three-dimensional distribution of rock units with respect to their deformational histories.

- 3. • The primary goal of structural geology is to use measurements of present-day rock geometries to uncover information about the history of deformation (strain) in the rocks, and ultimately, to understand the stress field that resulted in the observed strain and geometries. • This understanding of the dynamics of the stress field can be linked to important events in the regional geologic past.

- 4. Structural fabrics and defects • Folds • Joints • Faults • Foliations • These are internal weaknesses of rocks which may affect the stability of human engineered structures.

- 5. Deformation of Rocks • Within the Earth rocks are continually being subjected to forces that tend to bend them, twist them, or fracture them. When rocks bend, twist or fracture we say that they deform (change shape or size). • Deformation common at plate margins. • Deformation concepts… – Force – Stress – Strain

- 6. Stress • The forces that cause deformation of rock are referred to as stresses (Force/unit area). • Differential Stress – Unequal in different directions. • A uniform stress is a stress wherein the forces act equally from all directions. • 3 major types of differential stress – Compressional stress – Tensional stress – Shear stress

- 7. Compressional Stress • Push Together stress. • Shortens and thickens crust. • which squeezes rock.

- 8. Tensional Stress • “Pull-apart” stress. • Thins and stretches crust. • Associated with rifting

- 9. Shear Stress • Slippage of one rock mass past another. • In shallow crust, shear is often accommodated by bedding planes.

- 11. Strain • Changes in the shape or size of a rock body caused by stress. • Strain occurs when stresses exceed rock strength. • Strained rocks deform by folding, flowing, or fracturing

- 12. How Rocks Deforms • Elastic deformation – The rock returns to original size and shape when stress removed. • When the (strength) of a rock is surpassed, it either flows (ductile deformation) or fractures (brittle deformation). • Brittle behavior occurs in the shallow crust; ductile in the deeper crust.

- 13. We can divide materials into two classes. • Brittle materials have a small or large region of elastic behaviour but only a small region of ductile behaviour before they fracture. • Ductile materials have a small region of elastic behaviour and a large region of ductile behaviour before they fracture.

- 14. How a material behaves will depend on several factors • Temperature - At high temperature molecules and their bonds can stretch and move, thus materials will behave in more ductile manner. At low Temperature, materials are brittle. • Confining Pressure - At high confining pressure materials are less likely to fracture because the pressure of the surroundings tends to hinder the formation of fractures. At low confining stress, material will be brittle and tend to fracture sooner. • Strain rate -- At high strain rates material tends to fracture. At low strain rates more time is available for individual atoms to move and therefore ductile behaviour is favoured. • Composition -- Some minerals, like quartz, olivine, and feldspars are very brittle. Others, like clay minerals, micas, and calcite are more ductile This is due to the chemical bond types that hold them together. Thus, the mineralogical composition of the rock will be a factor in determining the deformational behaviour of the rock. Another aspect is presence or absence of water. Water appears to weaken the chemical bonds and forms films around mineral grains along which slippage can take place. Thus wet rock tends to behave in ductile manner, while dry rocks tend to behave in brittle manner.

- 15. Evidence of Former Deformation • Evidence of deformation that has occurred in the past is very evident in crustal rocks. • For example, sedimentary strata and lava flows generally follow the law of original horizontality. Thus, when we see such strata inclined instead of horizontal, evidence of an episode of deformation. • In order to uniquely define the orientation of a planar feature we first need to define two terms – – Strike (trend) – Dip (inclination)

- 16. Dip and strike

- 17. Dip and strike • Consider a flat uniform stratum which is tilted out of the horizontal. On its sloping surface there is one direction in which a horizontal line can be drawn, called the strike. It is a direction that can be measured on beds that are exposed to view and recorded as a compass bearing. At right angles to the strike is the direction of maximum slope, or dip. • The angle of inclination which a line drawn on the stratum in the dip direction makes with the horizontal is the angle of dip (or true dip), and can be measured with a clinometers and recorded to the nearest degree.

- 18. Dip and strike Strike (illustrated by line s- t below) is the compass direction of a line marking the intersection of an inclined plane with a horizontal plane such as the Earth’s surface Dip (line d-p above) is the maximum angle between the inclined plane and the horizontal plane. Dip is always perpendicular to strike, and has both a compass direction and an angle.

- 19. Folds • It is frequently seen that strata in many parts of the Earth's crust have been bent or buckled into folds; dipping beds, mentioned above, are often parts of such structures. • An arched fold in which the two limbs dip away from one another is called an antiform, or an anticline. • A fold in which the limbs dip towards one another is a synform, or a syncline.

- 20. Fold geometry • In the cross-section of an upright fold the highest point on the anticline is the crest and the lowest point of the syncline the trough; the length of the fold extends parallel to the strike of the beds, i.e. in a direction at right angles to the section. • The line along a particular bed where the curvature is greatest is called the hinge or hinge-line of the fold ; and the part of a folded surface between one hinge and the next is a fold limb. • The surface which bisects the angle between the fold limbs is the axial surface, and is defined as the locus of the hinges of all beds forming the fold. This definition allows for the curvature which is frequently found in an axial surface.

- 21. Folds

- 23. Fold

- 24. Fold

- 25. Fold groups • The relative strength of strata during folding is reflected by the relationship between folds. Those shown in Figures are called harmonic folds as adjacent strata have deformed in harmony. Disharmonic folds occur when adjacent beds have different wavelengths the smaller folds being termed parasitic folds , or 'Z 4M' and 'S' folds. Box- folds and kink bands are examples of other groups that may occur.

- 26. Fold Group

- 27. Fracture-cleavage • This is mechanical in origin and consists of parallel fractures in a deformed rock. A band of shale lies between two harder sandstone beds, and the relative movement of the two sandstones has fractured the shale, which has acquired cleavage surfaces oblique to the bedding. The cleavage is parallel to one of the two conjugate shear directions in the rock. The spacing of such shear fractures varies with the nature of the material, and is closer in incompetent rocks such as shale than in harder (competent) rocks

- 29. Boudinage in Fold • When a competent layer of rock is subjected to tension in the plane of the layer, deformation by extension may result in fracturing of the layer to give rod-like pieces, or boudins (rather like 'sausages'), with small gaps between.They are often located on the limbs of folds; softer material above and below the boudin layer is squeezed into the gaps.

- 31. Gravity folds • Gravity folds, which may develop in a comparatively short space of time, are due to the sliding of rock masses down a slope under the influence of gravity.

- 32. Folds A fold is when the earth’s crust is pushed up from its sides. There are six types of folds that may occur: • Anticline • Syncline • Tight Fold • Overfold • Recumbent Fold • Nappe Fold

- 33. Anticline • An anticline occurs when a tectonic plate is compressed by movement of other plates. This causes the center of the compressed plate to bend in an upwards motion. • Fold mountains are formed when the crust is pushed up as tectonic plates collide. When formed, these mountains are usually enormous like the newly formed Rocky Mountains in Western Canada and the United States • To the top right is a picture of an anticline. Beneath is a picture of the Rocky Mountains.

- 34. Syncline • A syncline is similar to an anticline, in that it is formed by the compression of a tectonic plate. However, a syncline occurs when the plate bends in a downward motion. • The lowest part of the syncline is known as the trough. • To the top right is a diagram of a syncline fold (The bottom of the fold center is the trough). Beneath, is an example of a syncline in California. Can you distinguish the trough in this picture?

- 35. Tight Fold • A tight fold is a sharp peaked anticline or syncline. • It is just a regular anticline or syncline, but was compressed with a greater force causing the angle to be much smaller. • Folds such as these occur to form steep mountain slopes like those in Whistler, British Columbia. • To the left is a photo of a tight fold formed by extreme pressure on these rocks.

- 36. Overfold • An overfold takes place when folding rock becomes bent or warped. • Sometimes the folds can become so disfigured that they may even overlap each other. • An example of overfolding is shown in the diagram below.

- 37. Recumbent Fold • This type of fold is compressed so much that it is no longer vertical. • There is a large extent of overlapping and it can take the form of an “s”. • To the right is a diagram that shows the process of recumbent folding.

- 38. Nappe Folding • This fold is similar to a recumbent fold because of the extent of folding and overlapping. However, nappe folding becomes so overturned that rock layers become fractured. • To the right is a picture of someone standing under a fractured fold.