The changing face of malnutrition and regulatory and fiscal efforts to address the rapid food system changes and growth in obesity while also improving overall diet quality

- 1. The changing face of malnutrition and regulatory and fiscal efforts to address the rapid food system changes and growth in obesity while also improving overall diet quality Barry Popkin W. R. Kenan, Jr. Distinguished University Professor Department of Nutrition Gillings School of Global Public Health School of Medicine Department of Economics The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill THE W RLD IS FAT

- 2. Outline: The whys and consequences 1.Setting the stage: dynamics of under and overnutrition, the double burden and the global obesity situation facing LMICs 2. Major Global Driver: Dietary shifts and food system changes driving future increases and the rapidly shifting dynamics 3. Early stages of global large-scale public health efforts: methodological challenges for evaluations. 4. Future strategies and major gaps

- 3. 1. State of adult obesity across LMIC’s with most complete data on women • Large shift from undernutrition to overweight across all regions, with some critical exceptions – Accelerated increase in annualized prevalence of rural overweight status • BMI distribution shifting rightward, increasing significantly – Age-period-cohort work in China showed 8-10 kg increase in weight over a decade. • Waist circumferences increasing along with BMI • Mysterious challenge: WC/BMI ratio increasing in many countries for men and women • Adolescents: Not presented but much more complex picture with more undernutrition — fear of intergenerational transmission of stunting/undernutrition for large set of adolescent girls of reproductive age in both South Asia and subSaharan Africa

- 4. -1.75 -1.25 -0.75 -0.25 0.25 0.75 1.25 1.75 Annualizedchangeinprevalence Wasted Stunted Overweight or Obese Supplemental Figure 2. Annualized changes in malnutrition prevalence among children ages 0–4 from earliest to latest survey years in selected countries* * Countries presented here had earliest-to-latest-year data spanning 15 or more years, latest-year data after 2010, and a population greater than ≈15 million (with the exception of Jordan and Kyrgyz Republic, which both had smaller populations but were included for regional representation). The data presented is from years spanning 1988 to 2016, but exact years vary by country. The span of earliest-to-latest years collected ranges from 15 years to 24 years. All data are from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS, https://dhsprogram.com/) with the exceptions of China (China Health and Nutrition Survey), Indonesia (Indonesian Family Life Survey), Mexico (Mexico National Survey of Health and Nutrition), Brazil (Brazil National Health Survey), and Vietnam (Vietnam Living Standards Survey).

- 5. Cambodia China Indonesia Vietnam Armenia Kazakhstan KyrgyzRepublic Turkey Bolivia Brazil Colombia DominicanRepublic Guatemala Haiti Honduras Mexico Nicaragua Peru Egypt,ArabRep. Jordan Morocco Bangladesh India Nepal BurkinaFaso Cameroon Chad Comoros Congo,Dem.Rep. Congo,Rep. Coted'Ivoire Ethiopia Gabon Ghana Guinea Kenya Lesotho Liberia Madagascar Malawi Mali Mozambique Namibia Niger Nigeria Rwanda Senegal SierraLeone Tanzania Togo Uganda Zambia Zimbabwe Annualizeddifference EastAsia andPacific Europeand CentralAsia Latin America &the Caribbean MiddleEast &NorthAfrica Sub-Saharan Africa SouthAsia Annualized difference in growth rate of women aged 15-49 overweight/obese prevalence for lowest- vs. highest- wealth groups between first and last survey waves (positive is where poor wealth groups growth rates are increasing more than high wealth groups) * Countries presented here had earliest-to-latest-year data spanning 15 or more years, latest-year data after 2010, and a population greater than ≈15 million (with the exception of Jordan and Kyrgyz Republic, which both had smaller populations but were included for regional representation). The data presented is from years spanning 1988 to 2016, but exact years vary by country. The span of earliest-to-latest years collected ranges from 15 years to 24 years. All data are from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS, https://dhsprogram.com/) with the exceptions of China (China Health and Nutrition Survey), Indonesia (Indonesian Family Life Survey), Mexico (Mexico National Survey of Health and Nutrition), Brazil (Brazil National Health Survey), and Vietnam (Vietnam Living Standards Survey).

- 6. 82.8 82.5 82.0 78.6 76.6 78.7 86.7 86.3 84.6 80.6 83.2 83.3 70 72 74 76 78 80 82 84 86 88 90 USA Mex* USA White* USA Black* England* Mexico* China* WaistCircumference(cm) Year 1 Year 2 86.8 88.6 84.4 88.2 82.6 88.2 89.3 84.2 88.2 87.3 USA Mex* USA White USA Black England China* A. Women B. Men *Bonferroni Corrected t-test significant at <.05 level. Figure Predicted mean WC (cm) for BMI=25 kg/m2 in Year 2 compared to Year 1 for women and men aged 20-29 years in the US (by race/ethnicity), England, Mexico, and China.

- 7. The Consequences Vary by Race-Ethnicity: Body Fat Composition in the East Vs the West (Yajnik & Yudkin 2004)

- 8. The global double burden of malnutrition based on two alternate measures for all countries using the most recent data for low- and middle-income countries (based on UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimates) 40% overweight prevalence 30% overweight prevalence 20% overweight prevalence No double burden High-income countries Double burden at: Criteria, any two: child with wasting ≥15%, stunting ≥30%, wasting and stunting both ≥35%, or overweight ≥15%; woman with overweight ≥40% or thinness ≥20%, Criteria, any 2: Child with wasting ≥15%, stunting ≥30%, wasting and stunting both ≥35%, overweight ≥15%, and/or severe anemia ≥40%; woman with overweight ≥40%, thinness ≥20%, and/or severe anemia ≥40%. a. Current Double burden countries according to weight/height data: at least 1 wasted/stunted/thin and 1 overweight/obese child, adolescent, or adult in household b. Double burden countries (anemic/wasted/stunted and overweight/obese in household) in most recent survey year, based on 20%, 30%, and 40% overweight/obesity cutoffs Not for use or quotation until published Popkin et al Lancet 2019

- 9. Predicted double burden of overweight & wasting or stunting Double burden of overweight & wasting or stunting a. Earliest measure of double burden regressed on 1990 GDP (PPP) b. Most recent measure of double burden regressed on 2010 GDP (PPP) Sources: The data are from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS, https://dhsprogram.com/), with the exceptions of China (China Health and Nutrition Survey), Indonesia (Indonesian Family Life Survey), Mexico (Mexico National Survey of Health and Nutrition), Brazil (Brazil National Health Survey), and Vietnam (Vietnam Living Standards Survey) Note: the regressions control for population size and look at GNP (quadratic or second-degree polynomial form) 1990GDP/capita 10,000 8,000 6,000 4,000 2,000 Prevalence of double burden 2010GDP/capita 10,000 8,000 6,000 4,000 2,000 Prevalence of double burden Regressions relating GDP per capita to household double burden Azerbaijan Egypt Kazakhstan Comoros Guatemala Lesotho EgyptMyanmar

- 10. Major direct drivers: Role of our history Core biochemical and physiologic processes have been preserved from those who appeared in Africa between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago. Biology Evolved Over 100,000 Years Modern Technology has taken advantage of this biology Sweet preferences Cheap caloric sweeteners, food processing create habituation to sweetness Thirst, hunger/satiety mechanisms not linked Caloric beverage revolution Fatty food preference Edible oil revolution — high yield oilseeds, cheap removal of oils, modern processed food/restaurant sector Desire to eliminate exertion Technology in all phases of work and movement reduce energy expenditure, enhance sedentarianism Snacking Behavior Modern food marketing; modern accessibility everywhere of unhealthy nonessential convenient ready-to-eat snack foods Mismatch: Biology, which has evolved over the millennia, clashes with modern technology

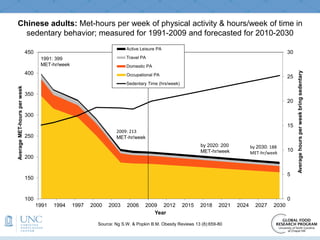

- 11. 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 2018 2021 2024 2027 2030 Averagehoursperweekbringsedentary AverageMET-hoursperweek Year Active Leisure PA Travel PA Domestic PA Occupational PA Sedentary Time (hrs/week) by 2030: 188 MET-hr/week 2009: 213 MET-hr/week by 2020: 200 MET-hr/week 1991: 399 MET-hr/week Source: Ng S.W. & Popkin B.M. Obesity Reviews 13 (8):659-80 Chinese adults: Met-hours per week of physical activity & hours/week of time in sedentary behavior; measured for 1991-2009 and forecasted for 2010-2030

- 12. From Jean-Claude Moubarac Evolution of Human Experience with Food • Old and accumulative process • Increase penetration of the matter • From domestic & artisanal to industrial Butchering, smoking & drying of meats Pounding, grinding, roasting, wetting, boiling, fermenting of seeds and acorns Granaries, agriculture, husbandry, pottery Large granaries Mass production of oil, salt & sugar Pasteurization, canning, roller mills Cooking Ultra-processing Industrial ingredients, biochemicals, genetics By Jean-Claude Moubarac Paleolithic 2 mya 300,000 BC Neolithic 12,000 - 2000 BC First States Post-war/global 1950-2013 Industrial 1780

- 13. Sources of major global dietary shifts: All significant in most Low and Middle Income Countries Global increases in: ↑ Use of added caloric sweeteners, especially beverages, but increasingly all packaged foods consumed ↑ Animal source foods ↑ Refined carbohydrates, ultra-(highly) processed foods ↑ Convenience foods for snacking, away-from-home eating, precooked/uncooked ready-to-heat food ↑ Large increase in edible oil used to fry foods (unique to LMICs) Global decreases in: ↓ Legumes, vegetables, fruits in most countries ↓ Food preparation time

- 14. From traditional to modern meals

- 15. From traditional to modern snacking

- 16. From traditional to modern marketing of food

- 17. First major global shift: Sweetness, added sugars Always loved sweetness and as fruit, provided unique source of nutrients.

- 18. A unique factor: Beverage-thirst and food-hunger mechanisms are not linked General Properties Food Water Hunger – Feeding Sensations that promote attainment of minimal food energy needs Thirst – Drinking Sensations that promote attainment of minimal hydration needs Energy Excess Stored Water Excess Excreted Energy Deficit: Die in 1-2 months Water Deficit: Die in 3-7 days

- 19. Mourao, .. (2007). "Effects of food form..." IJO:31(11): 1688-95. 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 Kcalsperdayconsumed Liquid Solid Liquid Solid Liquid Solid Carbohydrate (Watermelon) Fat (Coconut) Protein (Dairy) * * * Comparison of consumption of a beverage and a solid food on total energy intake shows beverage consumption in any macronutrient form significantly increases dairy energy intake

- 20. Mexican SSB distribution by age group (per-capita kcal/day from Quantile regressions), Ensanut 2012 58 99 175 133 178 108120 197 323 263 296 230 200 298 506 401 482 357 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 Preschool children School-aged children Adolescent males Adolescent females Adult males Adults females Energyintake(kcal/d) 50th percentile 75th percentile 90th percentile Source: Aburto, Poti, Popkin in press Pub Health Nutr.

- 21. Remarkably short history for caloric beverages: Might the absence of compensation relate to this historical evolution? AD BCE 10000BCE 200000BCE Beginning ofTime 100000 BCE 200000 BCE Homo Sapiens Pre-HomoSapiens 200,000BCE-10,000BCE OriginofHumans ModernBeverageEra 10,000BCE-present 0 Earliest possible date Definite date Water, Breast Milk 2000 BCE Milk (9000 BCE) Beer (4000 BCE) Wine (5400 BCE)Wine, Beer, Juice (8000 BCE) (206 AD) Tea (500 BCE) Brandy Distilled (1000-1500) Coffee (1300-1500) Lemonade (1500-1600) Liquor (1700-1800) Carbonation (1760-70) Pasteurization (1860-64) Coca Cola (1886) US Milk Intake 45 gal/capita (1945) Juice Concentrates (1945) US Coffee Intake 46 gal/capita (1946) US Soda Intake 52/gal/capita (2004)

- 22. a. Annualized change in SSB sales, 2004–2017 * Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) include regular cola carbonates, noncola carbonates (e.g., lemon/lime and orange carbonates, ginger ale, mixers), liquid and powder concentrates, juice drinks (up to 24% juice), nectars (25–99% juice), ready-to-drink coffees and teas, sports and energy drinks, and Asian specialty drinks. ** Includes low- and middle-income countries for which Euromonitor had data for the majority of SSB categories. Countries with modeled data were excluded. Data source: Euromonitor International Limited 2018 © All rights reserved Regressions of global trends in total sugar-sweetened beverage* (SSB) sales in low- and middle-income countries** Annualized change prediction (grams/capita/day) 2010GDP(PPP) -4.0 0.0 2.0 4.0-2.0 6.0 b. 2017 SSB sales SSB sales prediction (grams/capita/day) 2010GDP(PPP) -100 3001000 200

- 23. Sweeteners in Our Food Supply Key word searches in the ingredient list of each product: • Low-calorie sweeteners: artificial sweetener, aspartame, saccharin, sucralose, cyclamate, acesulfame K, stevia, sugar alcohols (i.e. xylitol) and brand name versions of each sweetener (i.e. Splenda) • Caloric sweeteners: fruit juice concentrate (not reconstituted), cane sugar, beet sugar, sucrose, glucose, corn syrup, high fructose corn syrup, agave-based sweeteners, honey, molasses, maple, sorghum/malt/maltose, rice syrup, fructose, lactose, inverted sugars Caloric Sweetener Low-calorie Sweetener

- 24. * excluding lemon/lime and when reconstituted) Source: Popkin,Hawkes Lancet Diab: 2016 30 29 32 31 31 34 28 26 28 3 6 5 0 0 0 9 14 12 63 60 55 66 66 63 58 51 45 3 5 7 2 2 2 4 9 15 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% 2000(N=40,562) 2006(N=76,971) 2013(N=129,527) 2000(N=35,896) 2006(N=67,600) 2013(N=113,015) 2000(N=4,666) 2006(N=9,371) 2013(N=16,512) All CPG Foods & Beverages Foods only Beverages only %uniqueformulationscontainingsweetenersbyweight Any fruit juice concentrate* Both nutritive and non- nutritive sweetener Nutritive/caloric sweetener only Non-nutritive/non- caloric sweetener only No added sweeteners Proportion of CPG products with unique formulations by weight containing any sweeteners

- 25. Second major global concern: Snacking • Snacking is a norm created by the food industry • The history of snacking — very rare until the mid-1900s except for festivals, royalty, war • When did snacking become a norm? – In the United States really began post-WWII • Today a different issue: – Brazil, Mexico, and the United States are three countries where our studies show >22% of kcal come from snacks, increasingly highly processed foods and beverages – China tripling each year from 2002,2004. 2006, 2009, 2011 but still small except for selected groups. • Increasingly refined carbohydrate and sugary snacks

- 26. a. Annualized change in junk food sales, 2004–2017 * “Junk” foods include cakes, pastries, chocolate & sugar confectioneries, chilled and shelf-stable desserts, frozen baked goods, frozen desserts, ice cream, sweet biscuits, snack bars, processed fruit snacks, salty snacks, savory biscuits, popcorn, pretzels, and other savory snacks. ** Includes low- and middle-income countries for which Euromonitor had data for the majority of junk food categories. Countries with modeled data were excluded. Data source: Euromonitor International Limited 2018 © All rights reserved Annualized change prediction (grams/capita/day) 2010GDP(PPP) Regressions of global trends in total junk food* sales in low- and middle-income countries** 0 0.5 1.0 1.5 b. 2017 junk food sales Junk food sales prediction (grams/capita/day) 2010GDP(PPP) -20 80400 20 60

- 27. Source: Euromonitor International Limited 2018 © All rights reserved Trends in per capita daily packaged junk food sales by category in select Asian countries, 2005-2017 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 China Malaysia Philippines Thailand India Gramspercapitaperday Sweet Biscuits, Snack Bars and Fruit Snacks Salty Snacks Confectionery Cakes & pastries China Malaysia Philippines Thailand India

- 28. Trends in total banner sales from quick-service, café, and full-service* restaurant retailers in select Asian countries, 2006–2017 × = No full-service restaurant data available. Source: Authors’ analysis of data from www.Planetretail.net. The sales figures are for the food retail chains PlanetRetail followed per country. PlanetRetail follows the leading national chains, not smaller chains, independents, or regional chains in a country. The total sales for a given country are thus an underestimate of all modern food retail sales but the trends are meaningful. × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × × 0.00 2.00 4.00 6.00 8.00 10.00 12.00 14.00 16.00 18.00 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 China India Malaysia Philippines Thailand BillionsUSD Full Service Restaurants Cafes Quick Service Restaurants China Malaysia Philippines ThailandIndia

- 29. Third major shift: Fatty foods and edible oils — unsure of weight and health effects • Fatty foods: smoother, affects taste in many ways • Shifts largest in Africa, Middle East, and Asia but also in the Americas • Oils have faced and will continue to face many challenges regarding trans fat content and unhealthy saturated fatty acid components, particularly palm oil whose consumption is growing very rapidly in LMICs. • Possibly the biggest early caloric drivers in the developing world other than SSB’s have been: – higher-fat junk foods, – other ultra processed foods with high saturated fats, and – ready-to-eat, ready-to-heat products.

- 30. Other Critical Eating Behavior Changes • Reduced healthy cooking • Increased away-from-home intake • Reduced home cooking are the major shifts

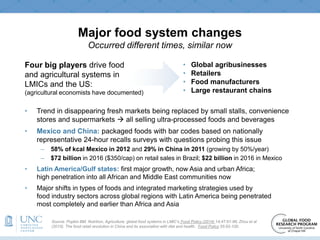

- 31. Major food system changes Occurred different times, similar now Four big players drive food and agricultural systems in LMICs and the US: (agricultural economists have documented) Source: Popkin BM. Nutrition, Agriculture, global food systems in LMIC’s Food Policy (2014) 14;47:91-96; Zhou et al (2015). The food retail revolution in China and its association with diet and health. Food Policy 55:92-100. • Trend in disappearing fresh markets being replaced by small stalls, convenience stores and supermarkets all selling ultra-processed foods and beverages • Mexico and China: packaged foods with bar codes based on nationally representative 24-hour recalls surveys with questions probing this issue – 58% of kcal Mexico in 2012 and 29% in China in 2011 (growing by 50%/year) – $72 billion in 2016 ($350/cap) on retail sales in Brazil; $22 billion in 2016 in Mexico • Latin America/Gulf states: first major growth, now Asia and urban Africa; high penetration into all African and Middle East communities now • Major shifts in types of foods and integrated marketing strategies used by food industry sectors across global regions with Latin America being penetrated most completely and earlier than Africa and Asia • Global agribusinesses • Retailers • Food manufacturers • Large restaurant chains

- 32. Stage 1 1800’s mainly scientific underpinnings Stage 3 Post WWII massive investments modern system Stage 4 Systematically transmitted globally (1955-2008) Stage 5 Commercial sector shifts major drivers of system change (present) Stage 2 1900-1944 Stage 6 Healthier food supply Reduced noncommunicable diseases, reduced climate footprint, achieve total sustainability, fewer animal source foods consumed Production linked to the needs of food manufacturers and retailers, ignoring climate, sustainability, and health concerns Green revolution, irrigation, credit, farm extension, and agricultural institutions mirror those of the west; modernizing of food processing High income countries see rapid mechanization; development of new food processing technologies (e.g. extraction of edible oils from oilseeds); and investment in transportation/ irrigation/electrification/ modernization of agriculture Farming systems developed; underpinnings post WWII revolution added modernization of agricultural production inputs and machinery Farming remains the major source of the food supply; industrial/large- scale monoculture initiated Investments in infrastructure and training Food industry farm links drive production and marketing decisions, incentives and economic drivers change Investment training, institutions, infrastructure, CGIARC (Consortium Global International Agricultural Research) Extensive funding for major infrastructure, systems, input and enhanced seeds, and major technology development Expansion of science; develop reaper; many other technologies Fossil energy, modern genetics, fertilizer, beginning agricultural science and experimental work, & land grant/agricultural universities Price incentives, taxation, other regulatory controls (e.g. marketing healthy food only) and system investments Retailers, agricultural input & processing, businesses, and food manufacturers dominate farm-level decision-making Farm research, extension systems, and education mirror those of the West Create the modern food system focused on staples, animal source foods, and cash crops Expansion technologies; science Stages of modern global agricultural system’s development Science and institution building Scientific and technological change, economic change, urbanization, globalization Source: © (copyright) Barry M. Popkin, 2015 See Anand,Hawkes et al, J Am College Card (2015) 66; Popkin (2017) Nutr Reviews

- 33. 3. National Regulations • Counter-factual option: look at shift in existing trends using historical trends, modeled and adjusted fully. – Look at shifts in trend line • Controls: No true controls for a country intervention so use other methods to understand changes linked to the law. • Differences when discussing US cities where groups we advise are using other cities (e.g. Baltimore for Philly) but we have our concerns with such options and areas around municipalities for leakages a. Evaluation Design: Taxes

- 34. Mexico: Modeling Used household food purchase data pre-tax (2012-13) and post-tax (2014-2015) Conducted pre-post comparisons of purchases using observational data, accounting for: • Seasonality in prices & purchases • Concurrent SSB and junk food taxes • Other concurrent changes (e.g., economic climate, consumer preferences) volumepurchased 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Month-Year 2012 20142013 pre-tax trend post-tax trend observed Modeling post-tax trend counterfactual Colchero et al BMJ. 2016;352:h6704; Colchero et al, Health Affairs. 2017;36:564-571

- 35. Mexico: SSB tax Findings: • On average, SSB purchases were 6% lower (-12ml/cap/d) while purchases of untaxed beverages (mainly water) were 4% higher compared to counterfactual in 2014 • Larger decline (9%; -19ml/cap/d) among low SES households • Decline in SSB consumption from SSB tax (-12ml) is small relative to growth in earlier years Colchero et al BMJ. 2016;352:h6704; Colchero et al, Health Affairs. 2017;36:564-571

- 36. Mexico: SSB tax Findings: • On average, SSB purchases were 6% lower (-12ml/cap/d) while purchases of untaxed beverages (mainly water) were 4% higher compared to counterfactual in 2014 • Larger decline (9%; -19ml/cap/d) among low SES households • Decline in SSB consumption from SSB tax (-12ml) is small relative to growth in earlier years Colchero et al BMJ. 2016;352:h6704; Colchero et al, Health Affairs. 2017;36:564-571

- 37. Mexico: Junk food tax — bigger reach, potentially larger impact 8% tax on non-basic foods (subject if >275kcal/100g) – salty snacks – confectionary – chocolates – flans – sweetened fruit or vegetables – peanut or hazelnut butter – milk candies – ice-cream if energy dense – grain-based foods (all except: tortilla, pasta, plain bread, flour, baby cereals) Missing foods • Not collected in Nielsen: – Most of unpackaged items – Confectionary and candies • Not collected consistently in Nielsen: – Bread from bakery – Tortillas – Chocolates Batis et al PLOS Medicine. 2016;13:e1002057; Taillie et al Preventive Medicine. 2017;105:S37-S42

- 38. Mexico: junk food tax Findings: • Mean volume of taxed foods purchased in 2014 declined by 5.1% (25 g/cap/mo) beyond what would have been expected based on pre-tax trends (2012-2013) – no corresponding change in purchases of untaxed foods. • Low SES households showed greater response to the tax, purchasing on average 10.2% less taxed foods than expected. – Middle- and high-SES households purchased 5.8% and 2.3% less taxed foods than expected, respectively. Batis et al PLOS Medicine. 2016;13:e1002057; Taillie et al Preventive Medicine. 2017;105:S37-S42

- 39. Sugary drink taxes around the world Western Pacific: Philippines Brunei Cook Islands Fiji Palau French Polynesia Kiribati Nauru Samoa Tonga Vanuatu Updated July 2, 2018 Copyright 2018 Global Food Research Program UNC Americas: USA (8 local) Mexico Dominica Barbados Peru Chile Bermuda Europe: United Kingdom Ireland Norway Finland Estonia Belgium France Hungary Spain (Catalonia) Portugal St Helena Africa, Eastern Mediterranean and Southeast Asia: Saudi Arabia Bahrain United Arab Emirates India Sri Lanka Thailand Maldives Mauritius South Africa IMPLEMENTED PASSED

- 40. SAMOA: 0.40 WST per L ($0.15) on carbonated beverages. Implemented 1984 FR. POLYNESIA: 40 CFP/L local ($0.39); 60 CFP/L import tax ($0.58) on sweetened drinks. Implemented 2002 PALAU: $0.28175/L import tax on carbonated soft drinks. Implemented 2003 FIJI: 0.35 FJD per L local ($0.17); 15% import duty on sweetened drinks. Updated 2016. 10% import duty on concentrates. Implemented 2007, updated 2017 NAURU: 30% import duty on all products with added sugars (+ removal of bottled water levy). Implemented 2007 COOK ISLANDS: 15% import duty (with 2% rise per year) on sweetened drinks. Implemented 2013 TONGA: 1 Pa’anga per L ($0.44) on carbonated beverages. Implemented 2013 KIRIBATI: 40% excise tax on drinks containing added sugar and fruit concentrates, 100% juices exempt. Implemented 2014 VANUATU: 50 vatu/L excise ($0.45) on carbonated beverages containing added sugar or other sweeteners. Implemented February 2015 INDIA: 12% goods and services tax on all processed packaged beverages and foods; additional 28% GST on aerated beverages and lemonades. Implemented Jul. 2017 UNITED ARAB EMIRATES: 100% excise tax on energy drinks; 50% tax on all carbonated drinks except sparkling water. Implemented Oct. 2017 BAHRAIN: 100% excise tax on energy drinks, 50% excise tax on aerated soft drinks. Implemented Dec. 2017 SAUDI ARABIA: 100% excise on energy drinks, 50% tax on carbonated drinks. Implemented Jun. 2017 MAURITIUS: MUR 0.03 per g sugar ($0.0009) on sodas, syrups, and fruity drinks with added sugar. Implemented Jan. 2013, updated Oct. 2016 SOUTH AFRICA: ZAR 0.021 per g sugar ($0.002) on sugary drinks and concentrates (4g per 100mL exempt). If sugar not labeled, default tax based on 20 g sugar/100mL; exempts dairy drinks and fruit, vegetable juices. Implemented Apr. 2018 MALDIVES: MVR 33.64 per L ($2.18) import tariff on all energy drinks; MVR 4.60/L ($0.30) tariff on soft drinks (incl. sweetened and unsweetened carbonated sodas, sports drinks) Implemented Mar. 2017 SRI LANKA: LKR 0.50 per g sugar ($0.003) on sweetened drinks, or Rs 12 per L ($0.08) — whichever is higher. Implemented Nov. 2017 BRUNEI: BND 4.00 per 10 L ($ 0.37/L) excise on all drinks with >6 g sugar per 100mL. Implemented Apr. 2017 IMPLEMENTED Sugary drink taxes: Africa, Middle East, Asia, and Pacific Updated July 2, 2018 Copyright 2018 Global Food Research Program UNC PHILIPPINES: 6 pesos per L ($0.12) on drinks using sugar and artificial sweeteners; P12 per L ($0.23) on drinks using HFCS; exempts dairy drinks, sweetened instant coffee, drinks sweetened using coco sugar or stevia, and 100% juices. Implemented January 2018 THAILAND: 3-tiered ad valorem and excise on all drinks with >6 g sugar per 100mL. Ad valorem rate will decrease over time as excise increases. Drinks with >6g sugar per 100mL will face higher tax rates, up to 5 baht/L ($0.16) for drinks with >10g sugar per 100mL from 2023 onwards. Implemented Sept. 2017

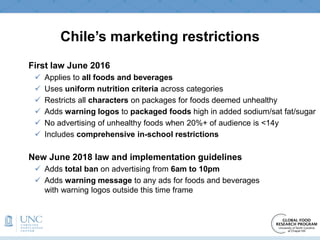

- 41. b. Evaluation Design: Chile, with multiple interventions and layers of timed changes focused on negative front-of-package labels • October 2014: 5% tax on SSBs relative to other beverages, incomplete, dropped some prices several % (will not show results—minimal impact, leakages into some sugary untaxed beverages, low price pass through) • July 1, 2016: foods and beverages with added sugars, sodium, saturated fats or calories that exceed set of thresholds (increasingly stringent over time) are subject to: • Front-of-package warning labels (on packaged products) • Marketing restrictions on children (≤14y) • 2018: Advertising ban extended to all TV and cinema from 6am – 10pm; warning message on regulated foods and beverages other hours of the day

- 42. Chile’s marketing restrictions First law June 2016 ✓ Applies to all foods and beverages ✓ Uses uniform nutrition criteria across categories ✓ Restricts all characters on packages for foods deemed unhealthy ✓ Adds warning logos to packaged foods high in added sodium/sat fat/sugar ✓ No advertising of unhealthy foods when 20%+ of audience is <14y ✓ Includes comprehensive in-school restrictions New June 2018 law and implementation guidelines ✓ Adds total ban on advertising from 6am to 10pm ✓ Adds warning message to any ads for foods and beverages with warning logos outside this time frame

- 43. Labeling unhealthy foods • 10% of front surface of the package • One for each high “critical nutrient” (sugar, saturated fat, sodium, or calories)

- 44. Focus groups Purpose: to explore how mothers perceive the food environment before and after the law and to investigate their understanding, attitudes, discourses, buying decisions and eating behaviors after introduction of the food regulation (including warning labels). • Nine focus groups of 7-10 mothers of children aged 2 to 14 (84 in total) • Different SES backgrounds • July 2017 Santiago, Chile

- 45. Changes in social norms Mother of a 9-year-old child explained: “My son eats at school. He, by his own, started to decide what he can eat and what not, this is because of these black logos that are in the package.” “Because of this new law, my daughter has been taught a lot about these black logos. ‘No mom, you can’t buy me that, my teacher won’t accept it because it has those labels.’And she requests me salads, she doesn’t accept snacks that have black labels.” — Gina, who has a 5-year-old daughter

- 46. Chilean results Not yet published, but will have publications on: • the first year of marketing and character bans • impacts on kids’ knowledge, attitudes, and exposure, and • effects on food purchasing. (astounding unprecedented impact in shift from regulated to unregulated beverages) SSB purchasing changes will be first to come out.

- 47. Last updated July 5, 2018 | © Copyright 2018 Global Food Research Program UNC Mandatory regulation of broadcast food advertising to children* Last updated 10/10/2017 © Copyright 2018 Global Food Research Program UNC National or regional statutory regulation * Not showing countries with regulations that apply to only specific/ limited products

- 48. Last updated July 5, 2018 | © Copyright 2018 Global Food Research Program UNC Countries with voluntary industry self-regulatory schemes Not shown: IFBA’s Global Policy provides minimum criteria for marketing directed to children <12y that is paid for/controlled by IFBA companies in every country where they market their products. Companies include: Ferrero General Mills Grupo Bimbo Kellogg Company McDonald's Mondelēz International Mars, Incorporated Nestlé S.A. PepsiCo, Inc. Unilever National or regional industry self regulation Last updated 10/10/2017 © Copyright 2017 Global Food Research Program UNC

- 49. Future strategies and major gaps • Fiscal policies focused on unhealthy products with minimal discussions to date on ways to use tax funds to encourage healthy food purchases (i.e. subsidizing foods) • Focused solely on retail sales and have ignored major dietary components: food service, street vendors/stalls • Food service: portion control via calorie labeling and then calorie pricing controls

- 50. Effectivenesspotential(populationlevel) Spectrum of approaches for changing behaviorsGov’t led Indiv driven Fiscal Measures (e.g., tax) Marketing/ advertising controls/FOP Industry’s voluntary efforts Food service & other regulations Modify choice architecture Cultural/ societal norms for healthy eating Individuals, communities, food manufacturers, retailers, food service, policymakers, regulatory agencies all have roles to play but to date little evidence they will without regulatory efforts Labeling & claims regs; Menu, Package Behaviors (measureable) as proxies for norms (non-measurable) Social marketing/ nutrition education 5. Our ultimate goal: How to use multiple approaches to change BOTH supply and demand? Slide derived from Shu Wen Ng

- 51. The Struggle Over the Millenia to Eliminate Arduous Effort Could Not Foresee Modern Technology