The Best of CityLab's The Future of Transportation

- 3. © 2014 CITYLAB Future of Transportation series editor: Eric Jaffe CityLab editor: Sommer Mathis Copy editor: Karen Ostergren Production/layout: Jennifer Adams Cover design: Aaron Reiss The Future of Transportation www.citylab.com/future-of-transportation/

- 4. Contents PART 1: THE PERFECT COMMUTE Chicago’s Big Bet on the Bus | 4 Putting a Price on D.C.’s Worst Commute | 13 The First Look at How Google’s Self-Driving Car Handles City Streets | 24 PART 2: THE SMARTEST TRIP How Denver Is Becoming the Most Advanced Transit City in the West | 42 What Running Out of Power in a Tesla on the Side of a Highway Taught Me About the Road Trip of Tomorrow | 55 The Triumphant Return of Private U.S. Passenger Rail | 68 PART 3: DESIGN IN MOTION Why Portland Is Building a Multimodal Bridge That Bans Cars | 79 If an Electric Bike Is Ever Going to Hit It Big in the U.S., It’s This One | 88 The Next-Generation Airport Is a Destination in Its Own Right | 100

- 5. T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N PART 4: POLICY IN PERSPECTIVE America’s Cities Are Still Too Afraid to Make Driving Unappealing | 111 The Next Century of Sustainable Communities Will Be Organized Around Transportation | 116 Why Can’t the United States Build a High-Speed Rail System? | 120

- 6. 1 INTRODUCTION Getting from here to there in the United States today can feel a lot closer to an episode of The Flintstones than The Jetsons.Every day we deal with problems that should be relics of the past: con- gested highways full of single-occupancy cars, mass transit sys- tems continually under threat of service cuts, and aging infra- structure on the verge of obsolescence if not total collapse. For all humanity’s advances, our daily haul can still be a nightmar- ish experience that reduces productivity, increases stress, en- dangers public safety, and hastens global climate change. Fortunately, the future is not all bleak. The flipside of these challenges is a bounty of ideas for how to improve travel in and around America’s cities. We’re recognizing the limits of our current highway systems, finding ways to increase transit effi- ciency and expand its development, and preparing for the not- so-distant day when our cars will drive themselves (and our “smart” streets will guide them). For every commuting obstacle we face there’s a brighter dream of better mobility. In a nine-month special series called The Future of Transporta- tion, which ran from February to October 2014, CityLab ex- plored the initiatives and technologies being developed right now that will change the way people travel around cities in the years to come. Our team of writers reported from every big met- ro area across the country, while mobility experts and local offi- cials shared thoughts and lessons that can apply to cities of all sizes. In both a physical and intellectual sense, we covered a lot of ground. This e-book includes a dozen of our favorite stories from the se- ries: three from each of its main parts (commuting, sustainabil- ity, and design), and three companion policy pieces. While it was impossible to choose every great moment, these selections

- 7. 2 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N reflect both the geographic and multimodal reach of the series, taking readers across the country on roads, rails, and runways. The articles have been copyedited slightly since their original publica- tion for clarity and consistency, and any factual corrections have been made to the text. Support for this series and this e-book came from The Rockefeller Foundation, whose mission for more than 100 years has been to advance a more resilient and equitable world. It’s our view that there may be no better way to achieve those goals than affordable, reliable transportation, and we thank The Rockefeller Foundation for their deep understanding and commitment to this issue. And rest assured our regular CityLab coverage will extend and expand on the themes we discussed in this series. The journey continues. Eric Jaffe Series Editor

- 8. PART 1 THE PERFECT COMMUTE New and better ways to enhance the journey to and from work.

- 9. 4 Chicago’s Big Bet on the Bus The Ashland BRT line has become a referendum on the city’s evolution. MATT DELLINGER | Originally published February 27, 2014 CHICAGO—Just 10 years ago, living in Chicago without an automobile was considered eccentric behavior. In 2002, a food-writer friend moved there from New York and bravely attempted to get by using public transporta- tion, taxis, and her own feet. Her colleagues at the Tribune thought her quite mad, and assigned her pieces in the suburbs (“part of my hazing,” she says). Being from Indianapolis, I often described Chicago as what would happen if my hometown and New York had a baby: Chicago is midwestern but ur- bane, approachable but grand—and somehow both car-oriented and tran- sit-friendly. Ten years has made a lot of difference. We now live in the age of bike-share and car-share, and today Chicago attracts plenty of people, mostly young and single, who would probably rather carry a flip phone than own a car. Yet the late 20th century remains baked into the city’s landscape—there are COURTESY CTA

- 10. 5 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N drive-through banks a 10-minute walk from Michigan Avenue downtown, and big-box stores and a strip mall with suburban-sized parking lots around the corner from the Steppenwolf Theatre. Chicago’s transportation split personality explains a great deal about how its recent plan for bus rapid transit (BRT) along Ashland Avenue could be- come controversial. And it has. In January, I met separately with opponents and supporters of the proposal, and both sides used the word transforma- tional to describe the city’s BRT plan. One side meant it as a compliment, the other as a slur. As cities across the country debate the merits of sacrificing car lanes for mass transit, many eyes are on the midwestern metropolis, where a proposal touted as a sensible way to improve commutes has be- come a referendum on how drastically the city should evolve. • • • • • Ashland Avenue is one of Chicago’s few continuous north-south thorough- fares, and its virtues as a transportation corridor have a lot to do with both its continuity and its position in the city. Thanks to the curve of the lakeshore, the avenue runs as close to downtown as a north-south arterial can while also reaching the northern neighborhoods, which happen to be, on the whole, the most affluent on the Ashland corridor. It intersects with seven Chicago Tran- sit Authority “L” stations, two regional Metra stations, and 37 bus routes. The planned 16-mile Ashland BRT route would affect a cross-section of Chi- cago that contains all of the city’s ethnicities, income levels, and zoning types. It slices through neighborhoods that are Polish, Mexican, African American, and white. It cuts through retail, residential, and industrial ar- eas. The current buses on Ashland carry more than 30,000 people every day, and they go very, very slowly: about 8.7 miles per hour. In 2012, shortly after Rahm Emanuel was elected mayor, he and then–Chi- cago DOT Commissioner Gabe Klein got to work on a progressive transpor- tation agenda that aimed to create 100 miles of protected bike lanes, a num- ber of rail improvements, and a trio of BRT lines. (Here’s where I should note that Klein told me that the Rockefeller Foundation, which provided support for this article, contributed $2 million in grants to advocate for Chi- cago BRT.) The first BRT line, known as the Jeffery Jump, has already begun

- 11. 6 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N daily service, running from the Loop downtown via Jeffrey Avenue to 103rd Street on the South Side. The second BRT line will run along two east-west streets in the Central Loop; construction on this Loop BRT line, which has not been particularly controversial, is scheduled to begin this spring. Ashland is the third line, and its planning began in 2012. A north-south transit corridor near Ashland had been studied for years as a way of con- necting the L lines so commuters could move between corners of the city without passing through downtown. Not long ago, the plan was for a new rail link, the Circle Line, which would have required new subway and el- evated track at a cost of more than $1 billion dollars. In the face of federal budget battles and cuts, such a figure could prove an insurmountable ob- stacle, and BRT has become popular among transportation planners and advocates because its dedicated lanes, traffic-signal priority, and prepay- ment system mimic the benefits of rail at a fraction of the cost. The Ash- land BRT line is estimated to cost $160 million, or $10 million a mile. • • • • • When you rule out subways and elevated trains, public transit must run on the streets, and in the case of Ashland, this means giving half of local road- way capacity to BRT buses. In the preferred design alternative chosen by the city, car and truck traffic would be limited to one lane in each direction. And while the stations for the Jeffery Jump and Loop BRT lines are curbside, the Ashland buses would run in the center of the road, with stations in the median—eliminating left-hand turns. (Many of the proponents I spoke with believe the final design will restore left turns onto major east-west arteri- als, however.) This dramatic reshaping of Ashland is a bit scary for some. Roger Romanel- li, executive director of the Randolph/Fulton Market Association, an orga- nization of local businesses, has led the charge against the BRT proposal. “Ashland is an industrial corridor with 700 businesses throughout,” he said. “They invested in our corridor because they had reasonable expecta- tion that Ashland would run the way it does today.” Indeed, Ashland in the central city has more than its fair share of auto- body garages, and the street is thick with parking lots and drivethroughs

- 12. 7 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N COURTESY CTA

- 13. 8 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N belonging to businesses that clearly cater to drivers. Representatives from a number of these, including a new Costco, came to public meetings in De- cember to speak out against the BRT plan. “You don’t go to Costco in a bus,” the store’s general manager told the Sun-Times. Romanelli’s criticism of the BRT plan is made more compelling by the fact that in the past he’s often advocated for better transit access. “I’d been work- ing as an economic-development practitioner for years. We’ve been pro– transit-oriented development, and pro–bus service,” he said. “We helped bring express buses to Ashland, and a new L station at Morgan and Lake.” Romanelli’s group has put forward an alternative plan for improving the corridor’s bus service. The Modern Ashland Bus plan maintains the open traffic lanes for cars while implementing a number of the features of BRT. He thinks those improvements should be instituted across Chicago. “We want to revolutionize bus service around the city,” he said. “If we can do it on Ashland Avenue—heated bus shelters, streamlined stops, signal prior- ity—we can do it throughout the city. The current bus service in this city is substandard.” Suzi Wahl, a neighborhood resident who works at Chicago O’Hare Interna- tional Airport, joined our meeting as well. Her main concerns were not in- dustrial in nature, but residential. When you take away Ashland as a driving arterial, she worries, thwarted through-traffic will inevi- tably divert to the smaller streets nearby, such as her own. “I see this as destroying the neighborhood,” she said. Wahl too has good transportation credentials: she takes the bus routinely, and she used to participate in Critical Mass bike rides intended to “take back the streets of our city” and remind people of the right to assemble. (She stopped riding after she became pregnant.) One night in October of 2013, while canvassing businesses on behalf of BRT opponents, Wahl felt a pain in her stomach and went to the emergency room at the University of Illinois Medical Center on Ashland. She was fine, but the adventure highlighted what she sees as a major drawback of removing traffic lanes and increasing congestion. “I see this as destroying the neighborhood.”

- 14. 9 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N “If that was post-BRT, I’d have my husband driving in the BRT lane. If that was my daughter, I’d be driving on the sidewalk,” she said. “A bus to the ER? Are you kidding?” The medical center’s administrators, meanwhile, have come out in support of the BRT plan, saying it would enhance access for employees and patients. But Romanelli and Wahl note that the medical center also happens to be a major landholder and could stand to benefit from development opportuni- ties along the BRT line. They point to an online map tool created by the Met- ropolitan Planning Council—showing zoning, vacancies, and median in- come along Ashland—as proof that some advocates have their eye on more than just faster buses. “Is the BRT also a Trojan horse for developers? To skyrocket taxes on Ash- land Avenue, take these buildings from these family-owned businesses who are struggling while minimalls are being constructed in our city?,” Ro- manelli mused. “Is this transit improvement, or is this a forced gentrifica- tion project?” • • • • • Chris Ziemann, project manager for Chicago BRT, freely admits that rede- velopment is a secondary goal. The primary goal, he says, is to help buses run faster and continue Chicago’s transition toward what’s known as “complete streets.” “The more transformative a project is, the less easy it goes down. And Ashland is extremely transformative,” he says. “But there’s growth pressure on the corridor anyway. We see car ownership decreasing. So this is to respond to those future trends. This is transformative because it needs to be.” Ziemann had organized a lunch with a handful of supporters at a Polish restaurant near Division and Ashland, and over blintzes and sausages, the group tried to make the case for the BRT, unafraid to describe the future Chicago they envisioned and the bold action required to facilitate it. Burt Klein, a board member of the Industrial Council of Nearwest Chicago, an organization not unlike Romanelli’s local-business association, admitted that his board colleagues were starkly divided on the issue of the Ashland

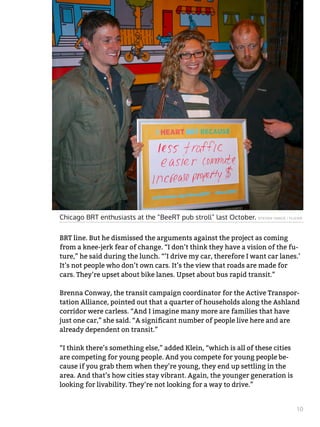

- 15. 10 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N BRT line. But he dismissed the arguments against the project as coming from a knee-jerk fear of change. “I don’t think they have a vision of the fu- ture,” he said during the lunch. “’I drive my car, therefore I want car lanes.’ It’s not people who don’t own cars. It’s the view that roads are made for cars. They’re upset about bike lanes. Upset about bus rapid transit.” Brenna Conway, the transit campaign coordinator for the Active Transpor- tation Alliance, pointed out that a quarter of households along the Ashland corridor were carless. “And I imagine many more are families that have just one car,” she said. “A significant number of people live here and are already dependent on transit.” “I think there’s something else,” added Klein, “which is all of these cities are competing for young people. And you compete for young people be- cause if you grab them when they’re young, they end up settling in the area. And that’s how cities stay vibrant. Again, the younger generation is looking for livability. They’re not looking for a way to drive.” Chicago BRT enthusiasts at the “BeeRT pub stroll” last October. STEVEN VANCE / FLICKR

- 16. 11 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N “We understand that people have gotten used to things. But that doesn’t make them good, you know?” said Conway. “You can’t not do something because it might be uncomfortable.” As agreed as the group was about the need for BRT, when I asked those around the table if there was anything they would change about the proj- ect, they all had peeves. Anna Shibrowsky, a copywriter who works at home and spends much of her break time commenting on transportation blogs, said she would re- move the parking from Ashland and replace it with protected bike lanes. Conway and Michael Whalen, a student at the University of Illinois at Chi- cago studying urban planning, both said they’d prefer the city tackle the entire 16-mile route at once rather than phase the construction. Klein ad- mitted that his industrial group was con- cerned about doing away with left turns, and the effect it might have on truck access. “But really I only care about one left turn,” he said, referring to one near his company’s of- fice. Everyone at the table laughed. “I make a joke of it, but that’s what matters to us.” He expected that his left turn would be restored in the final design phases, and he hoped the city would move quickly to finish the project. “I look at Ashland, and this is already five-to-10 years late,” Klein said. “By the time it’s built, Western [Avenue] will be overdue for BRT.” As we walked out of the Polish restaurant, Ziemann showed off the recently completed 11-story residential tower on the corner of Division and Ashland. He said it had replaced a boarded-up Pizza Hut and its parking lot. There were 99 units in the new building, yet no resident parking. Before this building was approved, a developer had come forward with a proposal for an apartment tower with a drive-through bank on the ground floor, but the neighborhood association nixed the idea. It would have brought too many cars to the area. • • • • • “You can’t not do something because it might be uncomfortable.”

- 17. 12 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Almost everyone agrees that the fate of the embattled Ashland BRT line will be decided in February 2015, when Rahm Emanuel is reelected, or not. The mayor has been quiet about the plan lately, but proponents have faith that he’ll see the new line through if he holds the mayor’s office. Romanelli is wise to this reality. “There are some lawyers involved,” he says, who are looking at whether the city’s environmental assessment of the project (which stated that it would have positive impacts on air quality and economic development, among other factors) might be worth challenging in court, “but really we’re looking at a pure political mobilization.” Ro- manelli is targeting local officials along Ashland, several of whom have come out publicly with concerns about the BRT’s transformative nature. If it were up to Gabe Klein, the former DOT chief, the city would fly some of the critics to a city where BRT is already working. This winter, Klein says, he went to Nantes, France, and rode the BRT there. “It’s amazing. I’m a huge advocate for BRT, but even I need to ride it to be reminded how amazing it can be,” he said. “People in Nantes can’t imagine the city without it. Just like most Americans—most people—can’t imagine something they haven’t seen before.”

- 18. 13 Putting a Price on D.C.’s Worst Commute I-95 south of the nation’s capital has some of the worst traffic in the country. Soon you’ll be able to buy your way out of it. EARL SWIFT | Originally published March 18, 2014 WASHINGTON—For a few giddy moments, it seems I’ve dodged the torture awaiting commuters heading into Washington, D.C., most any weekday morning. As I merge onto Interstate 95 in Fredericksburg, Virginia, 50 miles from the Pentagon, the traffic around me glides along at the 65-mph speed limit. No brake lights illuminate the predawn dark. I set my cruise control. Perhaps, I dare to think, this won’t be so bad. RAFAL OLKIS/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

- 19. 14 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N The illusion ends before I’ve covered a mile. Without warning or obvious reason, the highway’s flow thickens to a viscous dribble. My speed drops to 30, then 15, then an idling roll slower than I can walk. It remains there for a minute before shuddering to zero. I sit. It’s 6:30 a.m. on a typical Monday on the outskirts of the nation’s capital, and I’m mired in traffic the Texas A&M Transportation Institute reckons to be the worst in America, trumping even the titanic freeway logjams of Los Angeles. Here are highways so notoriously overtaxed that even on week- ends, “speed” is more a lovely abstraction than a realistic goal. Here is a circumferential interstate—the famed Washington Beltway—that has be- come synonymous with stress. Of all Washington’s snarled roads, perhaps none is more feared, despised, and lamented than the roughly 41 miles of I-95 between Fredericksburg and the Beltway, and I-395’s nine-mile spur from there to the Potomac. It’s a journey that should take under an hour but typically takes two or more in the morning. And in the evening, half again as long. My Camry inches northward, the sky lightening to a leaden gray, the air stinking of overheated brakes. For two generations, Virginia transportation officials have battled the route’s glacial pace with a succession of innova- tive prescriptions. In 1969, they installed the first reversible bus lanes in America, on I-395. A few years later they turned them into carpool lanes— the country’s first courtship with high-occupancy-vehicle lanes. Later they extended HOV 18 miles south, into the fast-rising suburbs and exurbs strad- dling I-95. The route remains a quagmire, just the same. So now the state is embarking on another fix. With financing from private investors, Virginia is convert- ing the HOV lanes south of Washington to high-occupancy toll lanes, or HOT lanes. These express lanes, like 20-some similar projects in cities from coast to coast, will enable solo motorists to drive alongside carpoolers—for a price. If the new system works as the Virginia Department of Transportation hopes, it will cull a fat number of commuters from I-95’s general-purpose lanes and speed the trip for everyone. The private investors may earn

- 20. 15 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N enough in tolls to retire their debts and make some money to boot. But the new arrangement differs from those already in place elsewhere, and with the differences come questions about how much relief it can offer. Some won’t be resolved until the new lanes are up and running in early 2015. All of which is to say that we’re soon to witness a complex and very expen- sive experiment. • • • • • The rush-hour nightmare in Northern Virginia is partly the product of to- pography. Geographic obstructions funnel travel into a narrow corridor occupied by I-95 and its smaller and equally congested parent, U.S. 1, and little else. It’s also partly the product of Northern Virginia real estate, which rises in price as distance from the District (and the exasperations of the daily commute) falls. Not many years ago, the 50-some miles to Fredericks- burg was an inconceivable distance for daily commuting; not so today, and the suburbs continue to spread like a stain, pushing farther south and west every year. Vdot’s attempts to address the corridor’s congestion by siphoning traffic from the general-purpose lanes have succeeded, at least in part. The bus lanes proved a hit 45 years ago—a Washington Post rush-hour race into the District saw a bus beat a car by 32 minutes, and before long bus commuters outnumbered their automotive counterparts on I-395. Likewise, the HOV lanes have consistently moved more people than the regular lanes at rush hour, according to Vdot. In fact, says the agency, they’re the most success- ful HOV lanes in the country. Be that as it may, the lanes are underused. As I sit immobile in my Camry in Dumfries, where the HOV lanes now have their southern terminus—and where an electronic sign predicts that I won’t reach the Beltway for another 52 minutes—the procession of cars entering the faster lanes amounts to a slim rivulet leaving the interstate’s main flow. So the state partnered with a joint venture of two private firms—the Texas- based Fluor Corporation and an Australian toll-road outfit, Transurban Group—to convert the existing I-95 HOV lanes to accept toll-paying custom-

- 22. 17 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N ers, and to extend them into Stafford County, Virginia, 27 miles south of the Beltway. As originally planned, the reversible HOT lanes would contin- ue inside the Beltway in the median of I-395 to the District’s very edge: the 14th Street Bridge, where the highway crosses the Potomac. Drivers using the lanes would enjoy a high-speed shot from the far-flung suburbs all the way into town. In fact, they’re all but guaranteed that. A key part of the $922.6 million deal—under which the state will supply $82.6 million of the project’s cost, and Fluor-Transurban will pony up the balance in cash and debt—is that the HOT lanes will keep flowing at 55 mph. Fluor-Transurban, which will recoup its investment through the toll in- come it generates over 76 years, will maintain that flow through dynamic pricing, which makes a commodity of a commuter’s time. “There is a value to a less-congested lane that someone driving alone might be willing to pay for,” says Philip Shucet, a Norfolk-based consultant who led Vdot as the agreement took shape. “Congestion creates a demand for a freer-flowing lane; therefore, because of the demand, you can charge for the supply of that lane.” Fifty minutes into my journey, traffic in I-95’s general-purpose lanes chugs along at 15 mph. HOV traffic, a blur to my left, shares the median with tow- ering heaps of dirt and earth-moving gear. Construction of the new HOT lanes is nearly 70 percent complete, according to Fluor-Transurban, and on schedule for an early-2015 opening. • • • • • A taste of what motorists can expect is already available in the capital re- gion, for the I-95 project is the second phase of two in the state’s partner- ship with Fluor-Transurban. The first was the installation of HOT lanes on a 14-mile stretch of the Beltway’s curving western side, from its junction with I-95 north to just past the Dulles Toll Road. Portions of the highway now shoulder nearly a quarter-million vehicles a day. The 495 Express Lanes, as they’re officially called, opened in November 2012 after four years of construction. They cost $2.07 billion, according to

- 23. 18 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N the Federal Highway Administration, which covered the replacement of more than 50 bridges and overpasses and the creation of several new HOT- only entry and exit points. The public-private pact is structured much like that for I-95: in exchange for covering most of the bill ($349 million in cash, plus debt service on more than $1 billion in loans and bonds), Fluor-Trans- urban will operate the lanes for the coming 74 years, after which they re- vert to the state. “Vdot owns the road,” says Transurban spokesman Mike McGurk. “We’re essentially just renting.” The Beltway lanes are not reversible. Rather, two in each direction are sepa- rated from the general-purpose lanes by a line of flexible pylons and linked to exits by dedicated ramps. When I entered them on a weekday midmorning in early March, the whole northbound trip cost $6.75; reaching the I-66 inter- change would set me back $3.35, and the edge city of Tysons Corner, $5.05. Those prices struck me as steep until I buzzed past stacking traffic in the regular lanes at Annandale, a denser clog at I-66, and a mile-long clot at Tysons Corner. The Camry was making a steady 72 mph. I covered the 14 miles in under 14 minutes, which was downright surreal on that road at that time of day. Renderings of traffic flows on the I-95 Express Lanes. VIA TRANSURBAN OPERATIONS INC

- 24. 19 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N When I headed the other way, against the traffic, the toll was $2.55 all the way to the Springfield Interchange, where the Beltway meets I-95 and the I-395 spur into town. I didn’t have to hunt for change. Both Virginia proj- ects are designed to accept only electronic payment, through a transponder affixed to each vehicle’s windshield. Those motorists who travel alone can use a regular E-ZPass, and those who carpool, an E-ZPass Flex. The Flex model features a switch that converts the unit from toll-paying to HOV operation. When a driver enters the HOT lanes toting fewer than two passengers, the Flex unit operates as a standard E-ZPass. But drivers that qualify for HOV status merely need flip a switch on the box, excusing the car from the toll. As the vehicle approaches the HOT lanes, an electronic receiver will detect the transponder’s HOV setting and alert a Virginia state trooper posted nearby (and paid for by the partnership) to eyeball the pass- ing vehicle to ensure that it’s playing by the rules. “They also have technology in their cars that can communicate with the infrastructure,” says McGurk of the troopers. “So even if they’re traveling behind a car, they’ll know whether that car has identified itself as an HOV vehicle.” • • • • • Now for the questions, the first being: Will the I-95 HOT lanes attract a suf- ficient number of non-HOV users to make a dent in the traffic? So far the Beltway lanes have not enticed the number of motorists, or generated the level of revenues, that the partners expected. In 2013, Transurban figured it would take in $60.2 million; revenues actually totaled less than a third of that amount ($17.2 million). Weekday use was expected to reach 66,000 trips by year’s end; reality delivered about 38,000. This is in keeping with the early performance of HOT lanes in other U.S. metro areas. Revenues have disappointed in Atlanta, Houston, and Seattle. McGurk blames the novelty of the experience. “It’s the first time D.C. has ever seen dynamic tolling, and an E-ZPass requirement,” he says. “There’s some education left to do. There are still a significant number of drivers out there who do not have an E-ZPass. It’s taking some time for people to un- derstand how to take advantage.”

- 25. 20 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Even so, says McGurk, “there are good trends.” Toll income rose 18 percent from the second quarter to the third of 2013, and by another 24.2 percent by year’s end, despite a flattening in the number of trips in the lanes late in the year. Usage jumped by more than 60 percent over the first year of op- eration, he says, and Transurban has “heard great feedback from custom- ers who take the route.” The consortium, which recently refinanced its obli- gations, anticipates “consistent growth.” An important lesson is that “people tend to use it episodically, rather than all the time,” says J. Douglas Koelemay, director of Virgin- ia’s Office of Transportation Public-Private Partnerships. “The morning they have that early meeting, it’s important for them to move quickly, and they’re happy to pay the toll. On other days, when they’re not in such a hurry, maybe they don’t mind taking longer.” Fluor-Transurban “recognizes that it’s build- ing a long-term business,” says Koelemay, noting that the consortium has refinanced the venture. There are other broad questions—including the ongoing debate about whether or not HOT lanes are fair to low-income drivers—but in the case of the I-95 project, there’s one especially vexing worry. As a result of a legal standoff with Arlington County, the I-95 HOT lanes will now extend only 29 miles, to just inside the Beltway, instead of stretching 36 miles and taking commuters all the way from the exurbs to the Potomac. At this abrupt end point, the interstate’s express lanes will become HOV-only. Toll-paying motorists will be dumped back into the gen- eral population. • • • • • By the time I reach the Springfield Interchange, I’ve been on the road for 61 minutes. Just after sunup I slip beneath an overpass marking the first exit on I-395, at Edsall Road. Up ahead, crews are already at work in the median on the primer-painted bones of a massive flyover, which arcs from the fu- So far Beltway HOT lanes have not enticed the number of motorists, or generated the level of revenues, the partners expected.

- 26. 21 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N ture HOT lanes, curves over northbound I-395, and swoops down to merge into the freeway’s slow lane. This is the Turkeycock flyover, the northern terminus of the HOT lanes project. Here, seven miles shy of the Potomac, toll-paying commuters will be forced to leave their carpooling fellow trav- elers to rejoin 395’s stop-and-start traffic. What will happen? Will monolithic jams erupt as the merging traffic re enters the mainstream? Does the project merely relocate and compress the morning nightmare? Will commuters, recognizing that the HOT lanes offer them an express ride to gridlock, forgo the toll route altogether? “I don’t know how that’s going to work,” says Mark Dudenhefer, a former state delegate from Stafford County who suffers the I-95 commute every weekday. “How would you like to be the guy who pays whatever the toll is— Construction of the I-495 Express Lanes near Tysons Corner. VIA FLUOR

- 27. 22 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N from, say, $5 to $15—and you don’t get to where you need to go? You get forced back into the regular lanes, and you have bumper-to-bumper com- muter traffic. What have you really saved? It’s difficult to understand.” This is no idle worry, for the I-395 leg of the commute is often the toughest, as I find during my excursion. It takes me 23 minutes to cover the less than three miles from the Turkeycock flyover to the Arlington County line, which I cross at 2 mph. It takes another 18 minutes to traverse the roughly four miles to the Pentagon’s southwest corner, looming off to the high- way’s left. Another five minutes moves me half the length of the building’s south wall. The partners forged on, says Steve Titunik, a Vdot spokesman, because com- muting times should nonetheless fall. The surviving mileage includes a new general-purpose lane and dedicated HOT-lane ramps at one busy cross street that should loosen the knot on I-395. Dudenhefer, who says he was involved in the project’s early stages as a county supervisor, says holding out for a perfect solution could leave everyone in the same place 15 years from now. “I don’t think we could afford to wait,” he says. • • • • • This thing could go any number of ways. It could spawn new and fearsome jams on I-395, choking Arlington County with the exhaust of idling legions of cars. It could provide an improvement over the current, wearying daily grind. It could convince commuters who’ve shied away from carpooling that the HOV lanes are the only practical way to get a car into D.C. The HOT lanes could be so popular, and inspire so fierce a public de- mand for their extension to the Potomac, that talks between state and county resume. Fact is, there’s no telling what will happen, which makes the 95 Express Lanes’ opening in 10 or 11 months an occasion worth watching. J. Douglas Koelemay figures the truncated “Urban areas are never finished. They’re always changing.”

- 28. 23 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N project, while “not the final or most elegant solution,” is “in itself impor- tant.” It’ll bring some relief, he predicts. “And it does not preclude our com- ing to an agreement with Arlington to go into Arlington or through Arling- ton. If you do it in a way that doesn’t diminish your opportunity to get to the next piece, I think you’re OK. “Urban areas are never finished,” he says. “They’re always changing.” In the short term, some commuters may be satisfied by any tonic to their daily pain, no matter how mild. My experiment ends at 8:35 a.m., when I pull off I-395 just shy of the river and meander my way to Reagan National Airport. I have spent 125 minutes in the car. I have driven exactly 50 miles. By current standards, that’s not a particularly bad start to the day.

- 29. 24 The First Look at How Google’s Self-Driving Car Handles City Streets The vehicle has now moved beyond highways to its next phase: roaming the roads of Mountain View. ERIC JAFFE | Originally published April 28, 2014 MOUNTAIN VIEW, Calif.—The first rule of riding in Google’s self-driving car, says Dmitri Dolgov, is to not compliment Google’s self-driving car. We’ve been cruising the streets of Mountain View for about 10 minutes. Dolgov, the car’s software lead, is sitting shotgun. Brian Torcellini, the project’s lead test driver (read: “driver”), is sitting behind the wheel (yes, there is a wheel). He is doing no more to guide the vehicle than I’m doing from the backseat. I have just announced that so far the trip has been “amazingly smooth.” GOOGLE

- 30. 25 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N “The car knows,” says Dolgov. He means I have violated some robotic superstition, calling the contest too early. Or maybe he means my praise serves no function here. If I can tell how well the car is driving itself, so can the car. Google’s self-driving-car project began in 2009. The vehicle’s early life was confined almost entirely to California highways. Hundreds of thousands of test miles later, the car more or less has mastered the art—rather, the com- puter science—of staying in its lane and keeping its speed. So about a year and a half ago, Google’s team shifted focus from the predictable sweep of freeways to the unpredictable maze of city streets. I was invited along as the first journalist to witness how the car is handling its new urban lifestyle. Over the next few minutes, the autonomous vehicle makes several maneu- vers that someone not privy to Dolgov’s first rule would have been tempted to compliment. We go through a yellow light, the car having calculated in a fraction of a second that stopping would have been more dangerous. We push past a nearby car waiting to merge into our lane, because our vehicle’s computer knows we have the right-of-way. We change into the right lane for seemingly no reason until, a minute later, the car signals a right turn. We go the exact speed limit because maps that the car consults tell it this road’s exact speed limit. The car identifies orange cones in the shoulder and we drift laterally in our lane, to give any road workers more space. Between you and me: amazingly smooth. Equally amazing is that people around us are going about their daily lives. I’d read that drivers tend to gawk at the Google car from their own cars, but that is not the case today. At one intersection I look at the cars flanking us. The driver to our right finds her cellphone more fascinating than us; the driver to our left is resting his head in his palm, and may or may not be fall- ing asleep. There is a banality to vehicle autonomy in this place. It can’t be that they’ve missed us. If the spinning bucket suspended by four metal arms on the roof doesn’t give us away, the words Self-Driving Car on the rear bumper should. We’re in a white Lexus RX 450h, part of a fleet of about two-dozen prototypes, all of which now spend most of their time on

- 31. 26 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N surface streets. The bucket spins 10 times a second, emitting 64 lasers that generate 3-D information on objects all around us; the car also has radar that bounces 150 meters or so in every direction to perceive things a human driver never could. The Lexus’s interior is standard with the following ex- ceptions: a camera facing out from the windshield capable of reading traf- fic lights, street signs, etc.; an on/off button on the steering wheel to en- gage or disengage autonomous mode; a driver’s side display panel showing our speed and position; and a big red button on the wooden console—a kill switch the team has never had to use. “Every robot has a big red button,” says Dolgov. Dolgov is holding a laptop running a map that effectively displays what the car is “seeing.” There is a comment box on the screen where he can record notes should something of interest occur during the ride. Right now he is not recording any notes. “Not much interesting stuff is happening,” he says. I had actually been promised ahead of time that “interesting things” would happen during the ride, so I could feel a bit misled at this moment. Except I’m riding in a car that’s driving itself through a city so amazingly smoothly that people around us are falling asleep. In that sense this uninteresting ride feels profoundly, even unimaginably, interesting. • • • • • The head of Google’s self-driving car project is Chris Urmson, a tall man with tousled blond hair and a boyish grin to match an idealistic spirit. We met at a Google X building just before my test ride. Google X is the compa- ny’s tight-lipped (but loosening) innovation lab that both oversees and emerged out of the self-driving-car project. It is known for impossibly lofty goals with a sci-fi twist; its director, Astro Teller, is officially titled Captain of Moonshots. Urmson shares a resistance to incremental advance. “You make so much more progress when you’re thinking about changing the world rather than making this minor delta improvement on some- thing,” he says. “You can get fired up in the morning.”

- 32. 27 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Urmson came into driverless cars like so many in the field: via three auton- omous-vehicle challenges held by darpa in the mid-2000s. The first Grand Challenge, in 2004, was a legendary disaster. Urmson was part of a team from the robotics institute at Carnegie Mellon led by the former marine William “Red” Whittaker. The Carnegie Mellon car made the contest’s best showing despite traveling just 7 of 150 miles before getting stuck in an em- bankment. “Almost literally burst into flames,” says Urmson. At the next A map of the Google car’s route through Mountain View during the author’s ride along. GOOGLE

- 33. 28 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Grand Challenge, in 2005, they placed second and third, losing to a Stan- ford group led by Sebastian Thrun, who later started Google’s self-driving program. Urmson’s team did win the 2007 race—an “Urban Challenge,” notably, through 60 miles of a city environment. He came to Google in 2009 to develop the self-driving car because it felt like something “that might change the world.” Urmson knows the statistics on metro-area congestion. Americans spend 52 minutes a day commuting, he says, which works out to 4 percent of their lives. (“If I could give you 4 per- cent more life, you’d take it.”) His bigger goal is safety, and he recites these numbers, too: 33,000 people a year die on U.S. roads; car crashes are the leading cause of death for people age 4 to 34; at least 90 percent of colli- sions are the result of human error. “So this is kind of a big deal,” he says. After accomplishing two baseline goals in its first 18 months—one, to drive 100,000 miles on public roads; the other, to complete 10 100-mile courses on challenging routes throughout California—the Google car spent the next couple of years conquering freeways. That seemed a “sim- pler problem” to tackle first, compared with city streets, says Urmson. Yes, higher speeds make the potential cost of any mistake that much big- ger, but the fundamentals of freeway driving are pretty easy for program- mers to model. Cars move in one direction, making minor adjustments to speed and position. “To grossly simplify it,” Andrew Chatham, the project’s mapping leader, later tells me, “you follow the curve and don’t hit the guy in front of you.” Cars move at slower speeds on city streets, but the number of variables is almost endless, and they require vigilant attention in every direction. There are tight lanes and traffic lights, pedestrians and cyclists, oncoming cars and double-parked trucks, unprotected turns and unexpected roadwork—the exter- nal elements are infinite, and configured dif- ferently each trip. So surface-street driving It’s not just that surface street driving is far more complex than freeway driving, it’s also unpredictably complex.

- 34. 29 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N isn’t just far more complex than freeway driving, it’s also unpredictably complex. Take the problem of crosswalks at intersections. Sometimes pedestrians wait for the crossing signal and walk inside the lines. But sometimes they ignore the signal and cross as they please, and sometimes they’re just wait- ing on the curb for a friend and don’t mean to cross at all. Early on, the Google car had trouble categorizing these varying intentions and deciding how to respond. Now it’s graduated to subtler problems, like spotting a ped estrian who might be standing behind a utility pole at the corner. “It’s the rarer and rarer situations we’re working towards,” says Urmson. “The complexity of the problem is substantially harder. But basically over the last year we’ve come to the conclusion it’s doable, and that this intu- ition we had about making a vehicle that was fully self-driving was correct: that it was possible. That we actually think we can make one that really is safer than human driving.” • • • • • An interesting thing has happened in the car. We are in the left lane on Mountain View’s West Middlefield Road when some roadwork appears up ahead. A dozen or so orange cones guide traffic to the right. The self-driving car slows down and announces the obstruction—“lane blocked”—but seems confused what to do next. It won’t merge right, even though no cars are coming up behind us. After a few false starts, Brian Torcellini takes the wheel and steers around the cones before reengaging auto mode. “It detected the cones and it tried to go around them, but it wasn’t confi- dent,” says Dmitri Dolgov, typing at the laptop. “The car is capable of a lot of things, but unless it’s absolutely sure that it can handle some situation well, it will err on the conservative side.” Boiled down, the Google car goes through six steps to make each decision on the road. The first is to locate itself—broadly in the world via GPS, and more precisely on the street via special maps embedded with detailed data on lane width, traffic-light formation, crosswalks, lane curvature, and so on.

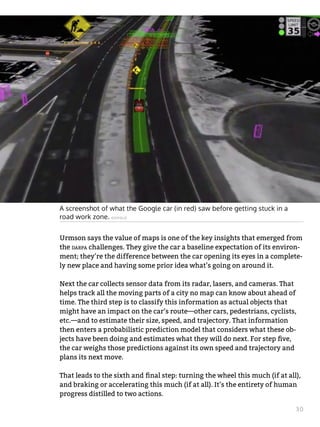

- 35. 30 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Urmson says the value of maps is one of the key insights that emerged from the darpa challenges. They give the car a baseline expectation of its environ- ment; they’re the difference between the car opening its eyes in a complete- ly new place and having some prior idea what’s going on around it. Next the car collects sensor data from its radar, lasers, and cameras. That helps track all the moving parts of a city no map can know about ahead of time. The third step is to classify this information as actual objects that might have an impact on the car’s route—other cars, pedestrians, cyclists, etc.—and to estimate their size, speed, and trajectory. That information then enters a probabilistic prediction model that considers what these ob- jects have been doing and estimates what they will do next. For step five, the car weighs those predictions against its own speed and trajectory and plans its next move. That leads to the sixth and final step: turning the wheel this much (if at all), and braking or accelerating this much (if at all). It’s the entirety of human progress distilled to two actions. A screenshot of what the Google car (in red) saw before getting stuck in a road work zone. GOOGLE

- 36. 31 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N The map on Dolgov’s laptop screen offers the best visual window into the car’s mind’s eye. Take the screenshot from one of our right turns (below). The baseline image is the detailed area map in grayscale. Layered atop that are objects identified by the car’s sensors, depicted in colorful geometric boxes: purple for vehicles, red for cyclists, yellow for pedestrians. The red and green ladders are objects that have an immediate impact on the car’s speed; in this case, though the traffic light is green, pedestrians prevent a turn, as does a cyclist coming up on the right—in a spot a human driver might easily miss. The flat green line shows the car’s planned route. Dolgov logs the roadwork incident in the computer. He explains that feed- back from the driving teams is critical to the car’s development. “Every dis- engage has a severity associated with it,” he says. “That was not the end of A screenshot of what the Google car sees approaching a right turn; inset, the view from inside the car. GOOGLE

- 37. 32 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N the world. We would have gotten through the cones. But it was a problem. Once we go back, we’ll pull the disk out of the car. We’ll import the log from this run. This will get flagged to developers. It will go into our database of scenarios and test cases we track. We’ll have more information about this on the desktops, but from what I saw on the screen, it looks like we detected [the cones] correctly, but for some reason the planner was conservative and decided not to change lanes. We’ll create a scenario that says, here, the right thing would have been to change lanes, and the next versions will have it addressed.” A few minutes later, we turn left across five lanes of oncoming traffic onto California Street and reach our destination: an open-air market called the Milk Pail. Rather than stop, though, we head back toward the Google cam- pus. At one point Dolgov and Torcellini realized air wasn’t coming out of the A/C system because the vents weren’t on. That was the biggest problem the car encountered until we’d just about reached campus. I had about closed out hope for more excitement when Dolgov makes an announcement. “We wanted to make the ride a little more interesting for you,” he says. • • • • • Dmitri Dolgov is soft-spoken with (at least on the day we met) biblical pa- tience for a reporter’s repetitive questions. He arrived at Google in 2009, at the same time as Chris Urmson. They’d known each other from their darpa challenge days, then as adversaries. Dolgov was part of Sebastian Thrun’s group at Stanford. Evidently the rivalry still lingers; when I met everyone else later that day to discuss my ride, they brought it up unprompted. “I was on a team that was not Chris’s,” says Dolgov. “Came in second,” says Urmson. “Different years, different places.” “Same year, different places.” “Well,” says Dolgov, “at least we didn’t flip our car upside-down.”

- 38. 33 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Race history aside, they share a clear belief that the self-driving car will have a transformative impact on road safety. Dolgov has been quoted as saying that if the car has to fail, he hopes it will “fail gracefully.” When I ask him to elaborate, he brings up the incident with the roadwork cones. “It didn’t handle it as well as you would want to,” he says. “But it kind of failed gracefully. It saw the cones early; it slowed down smoothly.” One could imagine a less graceful car, say, plowing right through them. “The car needs to recognize its limitations and do the conservative thing given its limitations,” he says. “Even when that means being slower or being stuck.” The Google car is programmed to be the prototype defensive driver on city streets. It won’t go above the speed limit and avoids driving in a blind spot if possible. It gives a wide berth to trucks and construction zones by shifting in its lane, a process called “nudging.” It’s extremely cautious crossing dou- What the Google car sees as it approaches a railroad crossing. GOOGLE

- 39. 34 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N ble yellow lines and won’t cross railroad tracks until the car ahead clears them. It hesitates for a moment after a light turns green, because studies have shown that red-light runners tend to strike just after the signal chang- es. It turns very slowly in general, accounting for everything in the area, and won’t turn right on red at all—at least for now. Many of the car’s capa- bilities remain locked in test mode before they’re brought out live. “We have lots of things we turn off until we’re confident,” says Dolgov. “And if you had a self-driving car that handled everything else well but didn’t do right on red? That’s still a useful thing.” Google’s self-driving “drivers” are programmed for caution, too. Torcellini, who’s been behind the wheel since 2009, may have logged more driverless miles than anyone else on the planet. He has a breezy manner—in the Google-car movie he’ll be played by Paul Rudd—but the driver-training pro- gram he’s designing is a rigorous one. He recruits detail-oriented and disci- plined individuals, several with military backgrounds. (“You can’t have a Craigslist ad for people with that type of experience,” he says.) He screens them with a driving interview. Once hired, drivers go through at least a month of training in both classroom and car, and must pass regular perfor- mance tests to ensure a steady development. “It seemed like I had the easiest job in the world, just sitting around in a Lexus, but in fact we’re paying really close attention to what the system is doing,” he says. “We know we have the repu- tation of not only Google but also the technol- ogy [on the line] every time we take a car out of the garage.” This safety-first culture gets a big assist from Google’s developers, who don’t need the cars to leave the garage to put them through sev- eral types of off-road simulation. They can invent a world using their CarCraft system to test out any road scenario imaginable. They can tweak the code and model hundreds of thousands of miles to determine what effect a change would have over time. They can even We’re hugging the curve when suddenly we jam on the brakes— a utility truck has cut us off on the left.

- 40. 35 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N take an instance when the driver disengaged and see what would have hap- pened if the car had been left alone. Inside the car, I found out what that means in practical terms: Google driv- ers don’t have to get into an accident to learn from one. • • • • • When Dolgov said they’d made the ride “a little more interesting” for me, he meant the team had staged a series of scenarios to demonstrate the full scope of the car’s city-street capabilities. First we turned down a road and came upon a woman riding a red, green, and yellow Google bicycle in the shoulder. She held out her left arm, which the car’s windshield camera de- tected and the software then identified as a turn signal. A little yield sign appeared above the cyclist on Dolgov’s laptop, and the car slowed down un- til the cyclist cut left and out of harm’s way. The car then passed a few more staged tests. We slowed for a group of jaywalkers and a rogue car turning in front of us from out of nowhere. We stopped at a con- struction worker holding a temporary stop sign and proceeded when he flipped it to slow—proof the car can read and re- spond to dynamic sur- roundings, making it less reliant on prepro- grammed maps. We merged away from a lane blocked by cones not un- like the one that had stumped us earlier. Urmson cites three big technological advances that have facilitated the car’s shift to surface The Google car can now recognize temporary stop signs, making it less reliant on pre-programmed maps. GOOGLE

- 41. 36 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N streets. The first is its ability to classify the objects around it. Early on, he says, they would be lucky to distinguish a car from a pedestrian; now they not only can tell the difference but can determine their travel paths. The second (and related) improvement has been in machine vision. That helps the car react to not only signals it expects, such as traffic lights, but those it doesn’t, such as the stop/slow sign. The third step forward is in machine learning—the system’s ability to interpret data and resolve a problem on its own. One of the clearest examples of the car’s progress is the way it turns left. Andrew Chatham, the mapping lead, explains that two years ago, the car made all left turns the same way: it drew a fixed path through the intersec- tion and adjusted its speed accordingly. But over time the team realized that cars approaching a left turn at a green light follow a very different path than those starting from a stopped position. So now the computer rec- ognizes this situation and computes a new route on the fly. It’s those little tweaks that bridge the gap between a jerky, robotic ride and an amazingly smooth one. Toward the end of my test run, after about a half hour of uneventful city driving, the car enters a cul-de-sac at the end of Charleston Street. We’re hugging the curve when suddenly we jam on the brakes—a utility truck has cut us off on the left. A few moments later it becomes clear that Torcel- lini had disengaged auto mode and hit the brakes manually; the car prob- ably had another second to decide on its own whether or not to stop, but rather than take the chance it wouldn’t, Torcellini performed what he calls a “conservative takeover.” I certainly hadn’t seen the truck coming, and the palpable release of tension in the car suggested this wasn’t one of the staged events. “It’s very easy for us to go back and simulate what the car would have done, had we not disengaged,” says Dolgov, logging the incident. Later on I ask Torcellini what he thought would have happened if he hadn’t taken over, and instead left the car to its own devices. “I think it would have stopped,” he says. “It would have done the exact same thing I did.” • • • • •

- 42. 37 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Top image: a screenshot of the Google car identifying the utility truck that cut it off. Bottom image: Google’s simulators determined that the car would have stopped before hitting the truck on its own. GOOGLE

- 43. 38 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Urmson met us after the ride to see how it went. I said I knew I wasn’t sup- posed to compliment the car, but that the ride had felt amazingly smooth. He turned to Dolgov. “Oh,” he says, “you told him the first rule of self-driving.” Urmson seemed a little disappointed that we’d needed to take manual con- trol of the car twice. He says it took about six months of focusing on surface streets to get the basic foundation in place, but that accounting for all the nuances of city driving will take more time. “Driving where you did today, it’s unusual that we would have disengaged twice,” he says. “Compared to some of the situations you’ll see on the road, a lot of what you saw today was pretty benign. It’s stuff in your daily life; you might drive it without worrying about it too much. So now we’ve still got room to grow there, but we’re pushing again on a few more of these longer problems. Trying to deal with smaller streets, less room to maneuver, more-difficult intersections— that kind of thing.” It’s still too soon to declare victory in the race for driverless cars, but that hasn’t stopped some experts from saying they expect autonomous vehicles on the road by 2030 (Nissan has pushed up its timeline to 2020). The history of self-driving technology is filled with premature confidence. At the 1939 World’s Fair, the famed General Motors’ Futurama exhibit predicted a world of radio-guided cars by 1960. In his recent New Yorker story on the Google car, Burkhard Bilger wrote that one of the team’s lead engineers, Anthony Levandowski, keeps reminders “of all the failed schemes and fiz- zled technologies of the past.” Urmson knows all too well the hurdles that still remain. One of the main limiting factors is that any city where the self-driving car goes must first be mapped with a precision far greater than what even Google Maps achieves. That’s doable in Urmson’s mind: “We know how to deal with that scale of data,” he says, referring to Maps and Street View. A greater challenge may be processing and codifying the myriad subtle social cues that remain so vital to navigating crowded city streets. Right now the car can’t detect a driver trying to wave it into a lane, for instance, or someone requesting a merge through eye contact. And it still can’t understand that universal language of urban traffic: honking. (It is, however, developing an “ear” for sirens.)

- 44. 39 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Then there is the matter of scale. Google has a goal of roaming all of Moun- tain View in the self-driving car by the end of this summer. That would be no small feat: the city has the feel of a typical college town, which makes it a great launching point for moving into many midsize U.S. cities, and its population of 74,000 no doubt rises considerably during the daytime hours, when the car roams its streets. But no one is mistaking it for San Francisco or New York or any other major metro area where traffic is so tightly packed and street behavior so wildly unpredictable that a super-defensive driver might suffer from paralysis by indecision. Still, Google is keenly aware what’s at stake. There’s the safety component, with cities rec- ognizing the need to strive for zero traffic fatalities. The nature of urban mobility itself is also on the line. Larry Burns, a former vice president for research and design at GM who’s now a paid Google consultant, says a taxi-like fleet of shared autonomous vehicles can become a viable business model if it can capture just 10 percent of all city trips. “I think that should be viewed as a new form of public transportation,” he says. Having recently invested in the ride-sharing service Uber, Google no doubt senses that marrying urban travel demand with autonomous vehi- cles could transform car ownership as we know it. I asked Urmson when he’ll consider the car a success. “I think it’s a success when people are using it in their daily lives,” he says. “When we have cars out there and people are moving around and we have statistical data that says we’re saving more lives than had these people been driving them- selves. The first time somebody who doesn’t work for Google is riding in one of these cars, getting to Grandma’s house or to work in the morning, or moving when they couldn’t otherwise move around the city, that’ll be a huge day for us. There’ll be lots of little wins between here and there, but that’s the big one.” A few days later I got an e-mail from the Google press staff saying the self- driving-car team had run a computer model on the near-miss with the util- ity truck. Turns out the car would have stopped on its own with “room to “There’ll be lots of little wins between here and there, but that’s the big one.”

- 45. 40 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N spare.” That sounds like one of those “little wins” Urmson mentioned, but I doubt he celebrated much. There’s a rule about that, and besides, the car already knew.

- 46. T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N PART 2 THE SMARTEST TRIP The crucial connections between transportation progress and achieving sustainability.

- 47. 42 TARAS GRESCOE | Originally published June 24, 2014 DENVER—It’s a vision straight out of a transportation planner’s fondest dream. In the center of the metropolis, the Beaux-Arts facade of a grand old rail- way terminus, finished in robin’s egg–hued stone, is cradled by the daring swoop of a canopy of brilliant white Teflon. On one of eight tracks, a dou- ble-decked passenger train has stopped to refuel. A few hundred yards Union Station is the centerpiece of Denver’s FasTracks expansion program. TARAS GRESCOE How Denver Is Becoming the Most Advanced Transit City in the West But the key question remains: will metro residents give up their cars?

- 48. 43 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N away, German-built light-rail vehicles arrive from distant parts of the city, pulling into a downtown of soaring condo towers and multifamily apart- ment complexes. Beneath the feet of rushing commuters, express buses pull out of the bays of an underground concourse, and articulated buses shuttle straphangers through the central business district free of charge. A businessman, after swinging his briefcase into a basket, detaches the last remaining bicycle from a bike-share stand next to the light-rail stop, com- pleting the final leg of his journey to work on two wheels. An out-of-towner could be forgiven for thinking she’d arrived in Stras- bourg, Copenhagen, or another global poster child for up-to-the-minute urbanism. The patch of sky framed in the white oval of the Union Station platform canopy, however, is purest prairie blue. This is Denver, a city that, until recently, most people would have pegged as an all-too-typical casualty of frontier-town, car-centric thinking. “Denver is a car town,” says Phil Washington, who has been general man- ager of the Regional Transportation District, metro Denver’s rail provider, since 2009. Originally from Chicago, Washington joined the transit author- ity after a 24-year career in the military. “You’ve got to remember, not so long ago, this was the Wild West. Historically, everybody had their own frickin’ horse. They’d strap them up on a pole outside the saloon. Folks feel the same way about their cars.” (Washington notes that even the RTD head- quarters—conjoined brick buildings in what is now rapidly gentrifying low- er downtown—was once a notorious brothel, located a convenient stroll from Union Station.) But in a state that recently voted to legalize the retail sale of marijuana, change is clearly in the wind. Ten years ago, Denver’s new mayor (and cur- rent Colorado governor) John Hickenlooper began to ramp up a campaign to convince voters to approve an ambitious expansion of the region’s embry- onic light-rail network. A similar plan—fuzzy on such key details as routes and cost—had been defeated in a 1997 referendum. In 2004, the region’s voters approved $4.7 billion of new debt for the FasTracks program. The plan, to add 121 miles of new commuter- and light-rail tracks to the region, 18 miles of bus rapid transit lanes, 57 new rapid-transit stations, and 21,000 park-and-ride spots, was approved 58–42, precisely reversing the results of the ’97 referendum. (The price tag has since risen to $7.8 billion.)

- 49. 44 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N COURTESY RTD

- 50. 45 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N Washington attributes the approval of FasTracks, in part, to growing frus- tration with traffic congestion. An earlier program called T-rex (for Trans- portation Expansion) not only built a light-rail line to the city’s southeast, but also widened Interstate 25, the region’s main north-south axis. Follow- ing the apparently immutable laws of induced demand, increased road supply led to increased traffic. Within a year, I-25 was just as congested as it had ever been. Voters, Phil Washington believes, came to the conclusion that transit offered a better path. Another key factor in the referendum’s success, Washington insists, was a concerted public-relations campaign. RTD, supported by the Denver Cham- ber of Commerce and the Denver Regional Congress of Governments (DRCOG), launched a communications blitz that had them doing presenta- tions in schools and city halls across most of the region’s 60 municipalities. “From the start, we made it clear we weren’t competing with the car,” says Washington. “And we explained, to the average Joe, that for only four cents on most $10 purchases, he’d be getting a whole lot of new transportation.” A rendering of the Westminster Station on the Northwest Rail Line. COURTESY RTD

- 51. 46 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N • • • • • Washington traces the progress of FasTracks on a poster-size map clipped to a whiteboard. Light-rail trains, on a track that branches south of down- town, already offer service to Littleton and Lincoln; extensions will see miles of new tracks penetrating even deeper into the southern exurbs. Last year saw the opening of the first FasTracks project, the West Rail Line, run- ning through some of Denver’s lowest-income neighborhoods to its termi- nus at the headquarters of Jefferson County. By 2016, the Gold Line to Ar- vada will offer further service to the west, and the East Rail Line will carry passengers to the airport; both lines will run heavy-duty commuter trains powered by overhead catenary wires. A rail line along Interstate 225 will create a loop east of downtown that Washington hopes will one day become a true circle line. Only the Northwest Rail Line, says Washington, remains a question mark. Intended to bring commuters from downtown to Boulder and Longmont, along 41 miles of track, it follows a Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad freight corridor. By 2016, a bus rapid transit system will offer service to Boulder, home to a university and cluster of tech companies that make it a major employment hub. The BRT along U.S. 36 will be more than just a stopgap; plans call for it to continue to run in tandem with commuter rail. Washington concedes that the line will be something less than full BRT. The buses currently on order have only one door, significantly slowing boarding and unloading, and will run in regular highway lanes, rather than dedicated busways. By 2018, when all but one of the 10 FasTracks lines should be completed, a metropolitan area with a projected population of 3 million, spread out over 2,340 square miles, will be served by nine rail lines, 18 miles of bus rapid transit, and 95 stations. Many argue the project will turn Denver into the west’s most advanced transit city, vaulting it beyond such better-known peers as Portland, Los Angeles, and Vancouver, British Columbia. “We’re witnessing the transformation of a North American city through transportation-infrastructure investment,” says Washington. He foresees a not-too-distant future when Denverites will be able to access not only com-

- 52. 47 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N muter and light-rail but also RTD buses, B-Cycle bicycles, and car-share ve- hicles using a single stored-value fare card. “You’ll wheel your suitcase out of Denver International Airport, ride the train to Union Station, and hop a Car2Go—or even a B-Cycle if you’re trav- eling light—to your house or hotel. All using one card.” It’s a beautiful vision, if one undermined by an uncomfortable truth. Den- ver’s mode share for transit—the proportion of people who use buses or light-rail to commute—is only about 6 per- cent. Contrast this with the Canadian city of Calgary, where a similarly sized bus and light- rail fleet operating in a similarly dispersed landscape draws in a mode share of nearly 17 percent. Even epically sprawled Atlanta and automobile-mad Los Angeles manage to achieve almost twice Denver’s per capita transit ridership. In spite of all the inducements, Denverites, like eight in 10 Americans, continue to get to school or work the same old way: driving alone. Will FasTracks make an appreciable number of people in Denver give up their horses—or their contemporary equivalent, private automobiles? The RTD is betting heavily that the answer will be yes. To achieve the transition, the agency is planning on changing not only the commuting habits of Den- verites, but also the DNA of Denver itself, making it into a far denser city. It’s a multibillion-dollar gamble not only on the future of transportation, but also on the future of the American metropolis—one whose outcome other cities will be watching very closely. • • • • • A trip to Denver, “The Queen City of the Plains,” once meant arriving in one of the continent’s great railroad towns. In its heyday, 80 trains a day passed It’s a multibillion- dollar gamble on the future of transportation and the future of the American metropolis.

- 53. 48 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N through Union Station—trains like the Pioneer Zephyr, a kinetic sculpture of wraparound windows and streamlined stainless steel, whose record- breaking 13-hour run to Chicago, in which it topped out at 112 miles an hour, earned it the nickname “Silver Streak.” Union Station, with its eight-foot-tall chandeliers and plaster arches lined with carved columbine flowers, announced Denver as an oasis of urbanity in the American West. Emerging from the Wynkoop Street entrance, trav- elers were met by the six-story-high Welcome Arch, illuminated with 2,194 incandescent light bulbs. Incongruously, the arch was emblazoned with the Hebrew word mizpah, meaning “God watch over you while we are apart.” (Denverites liked to kid newcomers that it was the Native American word for “howdy, partner.”) The grand opening of Union Station took place May 9, 2014. COURTESY RTD

- 54. 49 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N The fate of Union Station mirrors the fate of rail in much of North America. The Welcome Arch, which came to be seen as a traffic hazard, was torn down in 1931. Private interurban lines that linked downtown to Boulder in the north and Golden in the west disappeared with the coming of freeways. In 1958, a bright-red sign entreating Denverites to “Travel by Train” was erected on the facade of the station. Air travel had begun to outpace rail, and Stapleton Airport had become the new gateway to the city. The streets around Union Station became Denver’s skid row, the stomping ground for Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady, whose epic cross-country road trips were usually made by car, not train. By the 1970s, many of downtown’s most el- egant buildings, which went up at the height of the City Beautiful move- ment, had been replaced by oceans of surface parking. Change came with the new century. In 2001, RTD partnered with DRCOG to purchase the station and the surrounding acreage for $49 million. Union Station, currently a construction site, will once again become the center- piece of a renewed lower downtown, now rebranded “LoDo.” The station will continue to welcome Amtrak trains bound for Chicago and San Fran- cisco, but will also be home to the Crawford Hotel, a 112-room luxury prop- erty, set to opened in July 2014, with Pullman-style rooms and suites start- ing at $252. Cranes currently pivot over residential condo towers, the tallest of them 21 stories. On the north side of the station, adjacent to the light-rail stop, a whole new residential neighborhood, Confluence Park, has sprouted up on what used to be weed-ridden, trash-strewn rail yards. An elementary school has opened its doors in a high-rise tower, and the local supermarket chain, King Soopers, has staked a LoDo branch (there are rumors a Whole Foods will follow). All told, the station redevelopment has spurred $1.8 bil- lion in private investment. “RTD is one of the largest property owners in Colorado,” says Bill Sirois, the authority’s manager of transit-oriented development. He describes dozens of developments going up around FasTracks stations. On the East Rail Line, the Urban Land Conservancy, a nonprofit that purchases land to serve com- munity interests, has bought nine acres of land around the 40th and Colo- rado station, where it’s building 156 units of affordable housing. An eight- story housing complex for seniors is going up next to the 10th and Osage station. On the Central Rail Line, 275 new apartments are going up on a transit plaza adjacent to Alameda Station. All of these new developments

- 55. 50 T H E B E S T O F C I T Y L A B ’ S T H E F U T U R E O F T R A N S P O R T A T I O N will be within a half mile of a FasTracks line and well within walking dis- tance of a station. The biggest success story remains downtown, whose residential population has reached 17,500, a 142 percent increase since 2000. All told, FasTracks investment has brought 7 million square feet of new office space, 5.5 mil- lion square feet of new retail, and 27,000 new residential units. Driving demand for transit-oriented development, says Sirois, is Denver’s changing demographics. “We have a huge population of empty nesters,” he says. “More and more, they’re ditching their suburban homes and moving downtown.” Since the Great Recession, Denver has also become a hotspot for Millenni- als, knocking out such car-centric rivals as Phoenix and Atlanta. Members of Generation Y are less likely to own cars (or to want to own them) and more likely to opt for transit or active transportation (such as walking or biking). They are also multimodal by instinct: a recent survey found that 70 percent of those in the 25-to-34 age range reported using multiple forms of transportation to complete trips, several times a week. All of this bodes well for the future of FasTracks. RTD is counting on not only increased residential density around stations, but also the network effect—the synergy that happens when new transit opens, making more parts of a region accessible to more users—to drive ridership forward. “The system is developing and merging,” says University of Denver trans- portation scholar Andrew Goetz. “The opening of Union Station is a major threshold. It’s the intermodal heart of the network, bringing together rail and the regional bus system. The connectivity we’re going to see as a result is going to be quite impressive.” There’s evidence that Denver’s transit mode share is already improving. Daily light-rail boardings increased 15 percent between 2012 and 2013. Even skeptics are starting to see a future for transit in Denver. “Before it was a car town, Denver was a train town.”