Trends and projections towards the 20/20/20 targets

- 1. Trends and projections towards the 20/20/20 targets The speech for this presentation can be viewed in the slide notes below Dr Hans Bruyninckx Executive Director, European Environment Agency Brussels, 9 October 2013

- 2. The 2013 ‘Trends and Projections’ package 2013 ‘Trends and Projections’ report Report on approximated EU GHG inventories 33 separate country profiles Updated ‘Policies and Measures Database’ (PAMs)

- 3. Headline messages in light of 2020 objectives 1. EU emissions reduced by approximately 18 % compared to 1990 levels. 2. The EU is on track for reaching its 20 % target for renewable energy consumption by 2020. 3. The EU is making progress towards its energy efficiency objective.

- 4. EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – demand and supply

- 5. Compared ambition levels in ETS vs. non-ETS sectors EU-10 % EU-15

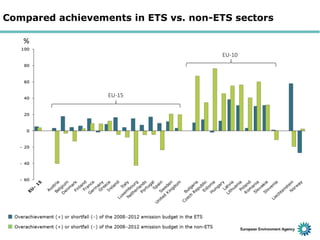

- 6. Compared achievements in ETS vs. non-ETS sectors % EU-10 EU-15

- 7. Progress towards the 2020 energy and climate targets Greenhouse gases Energy efficiency Renewable energy Estonia updated its energy statistics in September 2013. As this information was not received by the EEA in time for the publishing deadline of the report ‘Approximated EU GHG inventory: proxy GHG estimates for 2012’, 2012 emissions in non-ETS sectors appear to have been overestimated. The EEA has therefore not been able to take these new data into account for the assessments in this presentation.

- 8. How can Member States respond? 1. Ambitious GHG targets are needed in line with the existing global challenges – as stated in September’s IPCC analysis. 2. Good progress towards meeting energy efficiency objectives requires that mechanisms for proper policy implementation and enforcement are in place. 3. Appropriate policy instruments are essential for the development of renewable energy sources. 4. Some renewable energy technologies could play a more important role by 2020 than originally anticipated.

- 9. How can Europe respond? 2050 20/20/20 targets ETS 3rd trading period Effort Sharing Decision 2030 2020 2013 2020 Vision in 7EAP Low carbon society

- 10. A cost-efficient pathway towards 1Gt emissions in 2050 100% 80% Power Sector 80% domestic reduction in 2050 is feasible 80% 100% With currently available technologies; Current policy 60% 60% With behavioural change only induced through prices; 40% If all economic sectors contribute to a varying degree & pace. 20% Residential & Tertiary Efficient pathway Industry 40% Transport 20% Non CO2 Agriculture -25% in 2020 Non CO2 Other Sectors -40% in 2030 0% 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 0% 2050 -60% in 2040

- 11. The 2013 ‘Trends and Projections’ package 2013 ‘Trends and Projections’ report Report on approximated EU GHG inventories 33 separate country profiles Updated ‘Policies and Measures Database’ (PAMs)

- 12. Trends and projections in Europe 2013 Tracking progress towards Europe’s climate and energy targets until 2020 Thank you. eea.europa.eu

Editor's Notes

- We are in a transitional phase due to the end of the Kyoto Protocol’s first commitment period and the beginning of its second commitment period (due to run until 2020). We therefore need to ensure we can achieve the necessary cuts that are required in the longer term perspective. The release last week of the Fifth IPCC Assessment Report serves to underline the importance of the information presented today. The report confirms and strengthens the main findings of the Fourth Assessment Report with new evidence.

- Within this context I would like to present findings from a package of products that the European Environment Agency releases today.For the first time a full assessment of annual GHG emissions during the Kyoto Protocol’s first commitment period 2008–2012 can be provided. This is thanks to the increase in efforts from 18 Member States to provide more recent data as well as the EEA report on EU approximated GHG inventories which was published end of September and which complements these Member States estimates. These data allow for a more accurate assessment of progress than in previous years as well as a full analysis of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and non-economic sectors not covered by the ETS for the 2008–2012 period. 33 separate country profiles which include key facts on GHG emission and energy data for each Member State, as well as climate mitigation policies. The updated EEA Policies and Measures Database (PAMs), which presents the main policies and measures that Member States have planned or implemented in order to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Gathering all of this information is the 2013 edition of the Trends and Projections report. It has also broadened its scope to include a new assessment of progress towards energy policy objectives adopted by the EU for 2020.

- Before I provide comment on the ETS and non-ETS issues here are some headline messages looking towards the EU climate and energy policy objectives for 2020from the report: (1) EU emissions have reduced about 18 % compared to 1990 levels; (2) the EU is currently on track towards its target of 20 % of renewable energy consumption in 2020 having met its 10.7 % indicative target for 2011-2012; (3) there is progress being made to the towards 2020 energy efficiency objectives – yet only four Member States considered to be making good progress.

- As we know, for the second phase of the EU ETS (2008-2012) emissions were reduced below the caps already set in most Member States. Emission reductions took place within the EU ETS due to a number of factors such as a relative shift to the use of gas in the electricity sector and increased use of renewables. In addition, the recession, unforeseen at the time ETS caps were set, drove emissions further down emissions in the EU ETS. These reductions were larger than in the non-ETS sectors, because sectors in the ETS are more strongly linked to economic activity. Furthermore ETS operators made an increasing use of international credits during the second trading period, which increased the supply of allowances. This resultedin the surplus of allowances that is currently being addressed in the EU.

- As we are all aware the ETS was introduced to help Member States achieve their Kyoto targets and to achieve cost-efficient emission reductions at the sources of pollution themselves (so-called ‘point sources’) across the EU. Prior to the start of the Kyoto Protocol Member States were taking decisions on the quantities of allowances to allocate under the ETS. This was related to the organisation of their emission budgets for both the ETS sectors and the non-ETS sectors. Today’s report allows us to see the impact of these decisions made just before entering the first KP commitment period of 2008-2012. The EU-15 had an overall EU ETS cap (i.e. the maximum amount of emissions allowed) for the period 2008–2012 of 9 % below 2005 levels. Meanwhile the non-ETS sectors had an emission budget of 4 % below their 2005 levels. When they determined the level of ETS caps, Member States struck a balance in the effort to be made within the EU ETS and within the other non-ETS sectors. Some Member States decided to place more emphasis on the reductions in the non-ETS sectors compared to the ETS, such as Austria, Denmark, Luxembourg or Spain.

- Success in achieving national emission budgets through domestic actions in the non-ETS sectors has been more difficult. Today’s newly released EEA report provides some interesting findings. Almost all European countries with an individual GHG reduction and limitation targets under the KP were on track towards achieving their respective targets. This compares favourably to assessments in previous years. Interestingly, the report observes that in order to reach their Kyoto targets, nine Member States had originally placed more emphasis on emission reductions in the non-ETS sectors where domestic emission reductions are in general more costly to achieve compared to the ETS sectors – as we saw on slide 5. In particular, we can see that in Austria, Denmark, Italy, Luxembourg and Spain non-ETS reduction needs were higher than 15 % compared to 2005 non-ETS emissions levels. This figure shows that: emissions were reduced more in the ETS sectors than in the non-ETS sectors and significant gaps remain in the non-ETS sectors for a number of EU countries. These observations directly lead to the results of our assessment of Member States’ progress towards their respective Kyoto targets. To meet these emission reduction objectives in the non-ETS sectors, these countries will have to make use of carbon sinks and purchase quantities of Kyoto units that are significant at national level. These quantities represent between 13 % to 20 % of their respective base-year emissions, not taking into account the use of credits in the ETS, compared to an EU-15 average of 1.9 %.

- The first analysis I have presented can be considered as a retrospective of the recently closed ETS and Kyoto 2008-2012 period. We can now look ahead to 2020 targets. We can also reflect, as I mentioned in my introduction, if the progress we achieved is sufficient as we consider beyond the 2020 perspective. The EU is on track towards its 2020 target of reducing GHG emissions by 20 %. This 2013 edition of the Trends and Projections report broadened its scope to include a new assessment of progress towards energy policy objectives adopted by the EU for 2020. While the assessment of Member State progress shows overall relatively good progress towards climate and energy targets, no single Member State is on track towards meeting all three targets. Equally, no Member State underperforms in relation to all three areas. On the 2020 renewable energy targets, sources of renewable energy contributed 13 % of gross final energy consumption in the EU-28 in 2011. The EU has therefore met its 10.7 % indicative target for 2011-2012 and is therefore on track towards its target of 20 % of renewable energy consumption in 2020. Nevertheless the efforts ahead of us remain challenging. On energy efficiency there is mixed progress across Europe as only four Member States can be considered to be making good progress (reducing energy consumption and putting in place adequate policy framework across relevant sectors to improve energy efficiency). Overall, EU countries are moving towards the level of ambition required by the Energy Efficiency Directive but will remain insufficient to achieve the 20 % energy efficiency target. Key data and policy descriptions for each Member State can be found in the country profiles published today by the EEA. An assessment of Member States’ progress at national level across the three policy areas shows that overall the EU is making relatively good progress towards its climate and energy targets set for 2020. No Member State is on track towards meeting targets across all policy domains. Equally, no Member State underperforms in all three areas. Fourteen Member States are overall performing positively across the three policy domains: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia and Sweden. Four Member States have an overall neutral rating: Cyprus, Finland, Italy and the United Kingdom. Nine Member States score negatively overall: Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands and Spain. Croatia: n.a.

- The report provides some suggestions as to how Europe can respond to these challenges.Ambitious GHG targets are needed in line with the existing global challenges – as stated in September’s IPCC analysis. Good progress towards meeting energy efficiency objectives requires that mechanisms for proper policy implementation and enforcement are in place. The development of renewable energy contributes to significant emission reductions and primarily affects emissions in the EU ETS sectors. Appropriate and long-term policy instruments are essential for the development of RES. Certain RES technologies could play a more important role by 2020 than anticipated (when Member States drafted their national action plans in 2010).

- We are very much aware of the message emphasised by the latest IPCC report released last month. We can see that our policy makers have provided us with a vision for 2050. This is where we need to go. And our role is to find the transition pathways to get there. Countries such as Denmark and Germany are already actively looking towards 2050. Sustainability transitions are long-term, multi-dimensional and fundamental processes of change in socio-technical systems towards essentially sustainable modes of production and consumption. The EU is the most advanced region in the world for various targets including for biodiversity and climate change. Innovative thinking is needed to get us there. Debates on a national and European level are currently taking place about how to achieve the transition towards a low-carbon and energy-efficient future. Achieving optimal coherence between the various policy domains is crucial to maximise the co-benefits across sectors. This requires not only precise objectives, but also long term perspectives and equally long term support instruments.