Less sticks, more carrots: New directions for improving food safety in informal markets in low- and middle-income countries

- 1. Less sticks, more carrots: New directions for improving food safety in informal markets in low- and middle-income countries World Food Safety Day webinar, 7 June 2023

- 2. House Keeping Tech Tips • Use the chat to post comments during the presentations. Create a conversation! microphone is the next best solution. • Use the question function to ask questions to the panelists • Put your full name and organization - Tsehay Gashaw (ILRI) • If you can’t hear or see: close and restart zoom, close other programs • The session is recorded - audio, video and chat - and any private chats are also visible to the organizers.

- 3. Agenda Time What 9.00 - 9.05 Welcome to the event (Silvia Alonso) 9.05 – 9:15 Opening remarks 1 Appolinaire Djikeng (ILRI) - DG ILRI 2. Julian Lampietti (World Bank) - Manager, Global Engagement, Agriculture and Food Global Practice 9.15 - 9.35 Overview of the report and recommendations, Steve Jaffee 9.35 - 9:45 A new agenda for informal markets – ILRI’s ideas on how to move forward the recommendation, Delia Randolph 9:45 – 10:10 Commentary on the Launch – facilitated by Silvia Alonso 1. Simone Moraes Raszl (WHO) 2. Markus Lipp (FAO) 3. Pawan Agarwal (Food Future Foundation) 4. Amare Ayalew (African Union Commission) 5. Nika Larian (USAID’s Bureau for Resilience and Food Security) Response from authors (from 3-4 minutes) 10:10 – 10:15 Summing up and final remarks, Hung Nguyen, ILRI

- 4. New directions for tackling food safety risks in the informal sector of low- and middle-income countries Spencer Henson, Steven Jaffee and Shuo Wang

- 5. The Context or Problem Statement

- 6. Food systems in low- and middle-income countries Hybrid food systems yet fragmentation & informality are the norm Micro and small-scale aggregators, processors, distributors & food service operators collectively account for large shares of marketed foods. Especially for: Source: Adapted and modified from Teftt et al, 2017

- 7. Numerous surveys highlight food safety deficiencies in fragmented food systems & informal distribution channels Low food safety awareness and knowledge Weak and unhygienic physical environment Poor hygiene and unsafe food safety practices Limited effective consumer self- protection

- 8. A description from the community marketplaces of one capital city in Asia…a story common to many other locales “Degradation is widespread; waste and wastewater collection and treatment does not meet the required capacity; the supply of clean water is insufficient; the risk of inundation and poor drainage is high; equipment for business does not meet food safety requirements; fire protection doesn’t meet practical requirements…. … Meat has not been stored in cold containers, leading to exposure to the environment; vendors leave fresh meat and processed ones next to each other… no record on product origin… wastes are thrown directly to the floor and sidewalks…. …The infrastructure conditions and practices suggest a high risk of microorganism contamination to fresh agriculture product, especially meat. Especially in the summer when it is hot and humid, microorganism such as Norovirus, Salmonella, E. coli bacteria are in favourable conditions for growth, spoiling the meat and causing foodborne illness.”

- 9. But are small players really a big part of the food safety problem in developing countries? YES! The informal sector could account for a majority of the burden of foodborne disease associated with marketed foods in low and lower middle income countries

- 10. The Perspective

- 11. Incremental structural changes and top-down regulatory approaches will not solve the problem! The problem eventually goes away? 1. Formalization and consolidation? The problem stays & even worsens? • Traditional outlets & informal channels will remain prominent for the foreseeable future • Demographic, dietary & other changes are increasing consumer food safety risk exposures • Central government agencies have minimal interface with the informal sector 2. ‘Food control’ strengthening trickles down?

- 12. Recasting the problem and players and venues .… low incentives AND low capacity The ‘problem’: defined as an awareness gap and/or regulatory enforcement gap. Little distinction made among types of informal sector players or LMIC settings. Instead, need to recognize that there are…. different types of players with varied risk profiles .... and very different national, administrative and food system contexts.

- 13. Review of on-going, mixed experiences Broad strategies: Exclusion vs. incremental formalization Examples from other areas requiring behavioral change Sub-national state of play (i.e. Asian cities) Capacity: ◦ Training: Necessary but insufficient ◦ Collective action: Scope to better leverage ◦ Clustering players: Upgrading infrastructure strategically Incentives: ◦ Hygiene ratings & voluntary certification schemes ◦ Institutional procurement ◦ Engaging and empowering consumers Promising on-going experiment: ‘Eat Right India’ & differentiated approaches to food safety engagement and compliance support

- 14. Overall Assessment? Missing pieces, counterproductive measures, or promising elements which aren’t commensurate with the scale & complexity of the challenge Uncertain policy or benign neglect of traditional, community markets Punish and disrupt informal business operators Periodic training and awareness-raising programs Weak links to complementary areas of public policy Informal sector missing from national food vision & food law

- 15. Who is most at risk? Low and lower middle-income countries are the ‘critical hotspots’ Low/insufficient capacities to manage food safety risks from animal sources Multiple barriers to effective action on food safety matters among LMIC Asian cities

- 16. The Way Forward

- 17. 1. Local action, centrally guided Interventions at the municipal level: ◦ Both regulate and facilitate ◦ Part of urban (food & broader) governance ◦ Informal sector included in vision for healthy, sustainable and resilient cities Central government and agencies: ◦ Empower cities ◦ Provide technical guidelines ◦ Mobilize/unlock resources ◦ Facilitate experience-sharing

- 18. 2. Multisectoral & multi-stakeholder interventions • Synergistic interventions rather than stand- alone food safety measures and projects • Enhance capacity and incentives, both internal and external to food businesses • Foster & leverage collective action • Operationalize ‘shared responsibility’ between, business, consumers and government Big problem adversely impacting many Collective action mitigates a big problem

- 19. And, engaging with food operators differently… Less sticks and more carrots Enact and enforce Punish non-Compliance Engage and enable Motivate and facilitate compliance 19

- 20. A need for differentiated mixes and priorities Across countries and sub-sectors of the informal sector Key: Green relate to capacity; Orange relate to incentives

- 21. Thank you !

- 22. World Food Safety Day 2023 Natural Resources Institute , UK & International Livestock Research Institute, Kenya Delia Grace

- 23. Years of life lost annually for FBD FERG: Havelaar et al., 2015; Gibb et al., 2019 Health impact of FBD comparable to that of malaria, HIV/AIDs or TB USA – 1 in 6 Greece 1 in 3 Africa 1 in 10?? zoonoses non zoonoses 31 hazards • 600 mio illnesses • 480,000 deaths • 41 million DALYs

- 24. The public health and domestic economic costs – > 20 times trade related costs of unsafe food may be 20 times the trade-related costs for developing countries Cost estimates 2016 (US$ billion) Productivity loss 95 Illness treatment 15 Trade loss or cost 5 to 7

- 25. Foods implicated World Health Organisation, 2017 Fruit Milk Veggies Fish Meat/eggs

- 26. Informal markets have a major role in food security and food safety Benefits of wet markets Cheap, Fresh, Local breeds, Accessible, Small amounts, Sellers are trusted, Livelihoods for women, Credit may be provided (results from PRAs with consumers in Safe Food, Fair Food project) Wet market milk Supermarket milk Most common price /litre 56 cents One dollar Infants consume daily 67% 65% Boil milk 99% 79% Survey in supermarkets and wet markets in Nairobi in 2014

- 27. Food safety research at ILRI • 2006: Food safety research initiated • 2006-2016: focus risk assessment, policy analysis, understanding risk factors, literature review • 2016-2023: focus on interventions that are affordable, s scalable and will continue over the life of the project • Increasing engagement with national, regional and international actors • Co-led Food Safety Theme in Action Track One of UNFSS

- 28. savings on firewood / month = 900,000 UGX (260 US$) + >100 trees Reach: 50% of all pork butchers and their 300,000 customers in Kampala Abattoir and butcher intervention Uganda

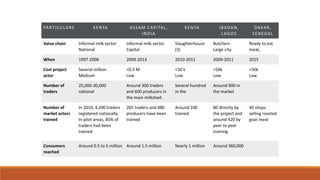

- 29. PARTICULARS KENYA ASSAM CAPITAL, INDIA KENYA IBADAN, LAGOS DAKAR, SENEGAL Value chain Informal milk sector National Informal milk sector Capital Slaughterhouse (3) Butchers Large city Ready to eat meat, When 1997-2006 2009-2013 2010-2011 2009-2011 2015 Cost project actor Several million Medium <0.5 M Low <50 k Low <50k Low <50k Low Number of traders 25,000-30,000 national Around 300 traders and 600 producers in the main milkshed Several hundred in the Around 900 in the market Number of market actors trained In 2010, 4,200 traders registered nationally. In pilot areas, 85% of traders had been trained 265 traders and 480 producers have been trained Around 100 trained 80 directly by the project and around 420 by peer to peer training 40 shops selling roasted goat meat Consumers reached Around 0.5 to 5 million Around 1.5 million Nearly 1 million Around 360,000

- 30. KENYA ASSAM STATE, INDIA KENYA IBADAN, LAGOS SENEGAL Enabling environment Yes KDB approval Yes Govt support No No No No No No Policy influence High – legislation changed and new institutions High- new institutions but no change to legislation None Low- only engagement with market authorities None

- 31. Kenya Assam state, India Kenya Ibadan, Lagos Senegal Intervention Training in hygiene and business practices; provision of hygienic dairy cans s; a certificate was given to successful trainees and this reduced harassment by officials. In depth training needs analysis; training of trainers; training covered hygiene and business skills; traders motivated by better relations with officials and positive publicity; farmers by visible reduction in mastitis Training in hygiene; raising awareness on food safety Peer-to-peer training on basic hygiene; provision equipment; banners and promotional material; use of butchers’ associations to monitor performance and ensure compliance. Control & 3 arms: Training & feedback on previous study, Hygiene pack, Training & hygiene pack Simple training & pack (brush, soap, trash can, apron etc). Pack=$60 Incentive Certificate business perf Various – oath, professionalization, Peer pressure Follow regulations Social norms Nudges Heuristics, rules of thumb Posters

- 32. Kenya Assam state, India Kenya Ibadan, Lagos Dakar, Senegal Documented impact Improved KAP after training Improved milk safety after training - reduction in unacceptable coliforms from 71% to 42% High economic benefits from the initiative - $33.5 million a year Improved KAP after training Significantly higher milk production after training (7.8 and 6.8 liters respectively) and tendency for reduced mastitis Sector level benefits in Kamrup at least $5.6 million a year No change in KAP after training – the management did not provide soap or other necessities and were rather indifferent to practices and there was no obvious incentive for behavior change Reduction of unacceptable meat from 97.5% to 78.5% (p<0.001); Significant improvements in KAP after training Cost of training is $9 per butcher and estimated gains through diarrhoea averted was $780 per butcher 70% microbial satisfactory before, improved after (n.s); No sig diff between arms No sig diff in economic performance Current status of the initiative Training and certification is episodic and project-led but trained vendors have an important share of the market . However, milk safety similar to untrained Training and monitoring is ongoing and supported by government None – one off training at the end of a prevalence study Safety worse than before, Govt. tried to relocate abattoir Butchers shot dead in street, Ongoing conflict one – one off research

- 33. 1. Many food safety interventions in LMICs do not scale 2. Scaling must be incorporated from the start 3. We know the critical success factors for scaling 4. We often need change only a small number of behaviours 5. Behaviours can be changed by a wide range of incentives and nudges 6. Authorities must be on board (or at least not anti informal market) Take home messages Learnings from first phase research

- 34. Pull approach (demand for safe food) Push approach (supply of safe food) ENABLING ENVIRONMENT Consumers recognize & demand safer food VC actors respond to demand & incentives Inform, monitor & legitimize VC actors Build capacity & motivation of regulators Empower consumers Three legged stool Progressive improvements infrastructure

- 35. Portfolio research projects 1. Safe Pork, Vietnam 2. Safe Food, Fair Food, Cambodia 3. BUILD – abattoirs Uganda 4. Pork and dairy value chains, India 5. MoreMilk, Kenya 6. Pull-Push Ethiopia and Burkina Faso 7. Safe African Vegetables, Nigeria 8. EatSafe, Ethiopia 9. One CGIAR butchers, Ethiopia

- 36. Control: Vendors who practices and operate their selling as usual Current surface (carton board) Washing detergent Trial: Vendor who get our incentive and used Easy to clean table surface Signpost And Training certificate Apron Tray Trial retailers: - 84% of the trial retailers had a good knowledge of safe meat handling compared to the control group (44%) - The KAP scores of retailers in the intervention significantly improved. MARKET VENDORS CAMBODIA

- 37. Acknowledgement

- 38. Next steps Recording will be available Questions, answers and disucsison wil be put together in a blog More information can be found here: https://www.ilri.org/world-food-safety-day-2023

- 39. THANK YOU