What is basel iii and why should we regulate bank capital

- 1. Economics for your Classroom from Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog Financial Reform: What is Basel III and Why Should We Regulate Bank Capital? Revised March 2013 Munsterplatz, Basel, Switzerland Photo source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Munsterplatz,_Basel,_Switzerland.jpg Terms of Use: These slides are provided under Creative Commons License Attribution—Share Alike 3.0 . You are free to use these slides as a resource for your economics classes together with whatever textbook you are using. If you like the slides, you may also want to take a look at my textbook, Introduction to Economics, from BVT Publishing.

- 2. What is Bank Capital? A bank balance sheet records the financial condition of the bank Assets are the income-producing items the bank owns, like loans Liabilities are what it owes—its sources of funds, like deposits By definition, capital equals assets minus liabilities In banking, the term capital is used instead of the terms net worth or equity that are often used in other areas of accounting. These terms are synonyms. Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 3. Why Banks Need Capital Banks need capital for protection in case of losses on loans or other assets Suppose a borrower defaults on a $50,000 loan, reducing total assets The bank still owes depositors $900,000 After the loan loss, capital (assets minus liabilities) falls by the amount of the loss If capital falls to zero or below . . . the bank’s assets are no longer enough to cover what it owes depositors It is insolvent and must cease operations Its shareholders stand to lose everything they have invested Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

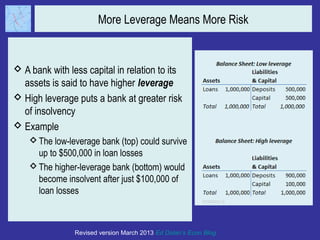

- 4. More Leverage Means More Risk A bank with less capital in relation to its assets is said to have higher leverage High leverage puts a bank at greater risk of insolvency Example The low-leverage bank (top) could survive up to $500,000 in loan losses The higher-leverage bank (bottom) would become insolvent after just $100,000 of loan losses Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

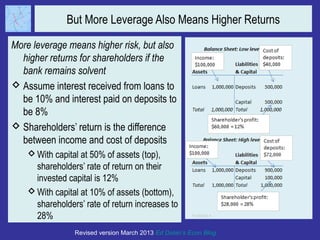

- 5. But More Leverage Also Means Higher Returns More leverage means higher risk, but also higher returns for shareholders if the bank remains solvent Assume interest received from loans to be 10% and interest paid on deposits to be 8% Shareholders’ return is the difference between income and cost of deposits With capital at 50% of assets (top), shareholders’ rate of return on their invested capital is 12% With capital at 10% of assets (bottom), shareholders’ rate of return increases to 28% Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 6. Regulators vs. Bankers’ Preferences for Leverage Varying the degree of leverage creates a tradeoff for shareholders between risk of insolvency and rate of return Bank regulators, who are concerned about the spillover effects that bank failures have on the rest of the economy, tend to prefer less risk, less leverage, and more capital than do bank managers To limit risk to the financial system, regulators set minimum standards for bank capital Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 7. Who Regulates Bank Capital? Bank regulators of individual countries do not act alone in setting rules for bank capital. They coordinate their capital regulation through the Basel Committee on Bank Supervision The Committee meets at the, Bank for International Settlements (BIS), an international organization, founded in 1930, that fosters monetary and Munsterplatz, Basel, Switzerland financial cooperation and acts as a Photo source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Munsterplatz,_Basel,_Switzerland.jpg bank for central banks Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 8. The Basel Accords The Basel Committee periodically issues “accords” that set out international standards for bank capital as well as other bank regulations The first Basel Accords, now called Basel I, were issued in 1988 They were replaced by a new set of Photo source: standards, Basel II, in 2004. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e4/Glo be.png Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 9. Failure of the Basel Accords Unfortunately, Basel II failed to prevent the global financial crisis that began in 2007 Government rescues of failed or failing banks like Citibank (US), RBS (UK), and Fortis (EU) cost taxpayers billions of dollars, pounds, and euros Failure of the Basel II standards can be traced to two major problems: They allowed banks to overstate their true amount of capital They allowed banks to understate the risks to which they were exposed Photo source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Citibank_Tower.JPG Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

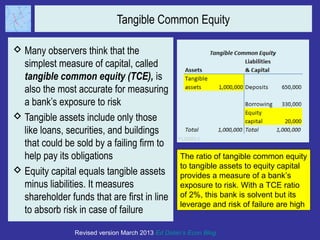

- 10. Tangible Common Equity Many observers think that the simplest measure of capital, called tangible common equity (TCE), is also the most accurate for measuring a bank’s exposure to risk Tangible assets include only those like loans, securities, and buildings that could be sold by a failing firm to help pay its obligations The ratio of tangible common equity to tangible assets to equity capital Equity capital equals tangible assets provides a measure of a bank’s minus liabilities. It measures exposure to risk. With a TCE ratio shareholder funds that are first in line of 2%, this bank is solvent but its leverage and risk of failure are high to absorb risk in case of failure Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

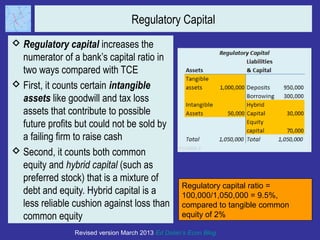

- 11. Regulatory Capital Basel II regulations did not use TCE to measure risk. Instead, instead they Regulatory Capital used the ratio of regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets Risk-Weighted Assets Both the numerator and denominator differ from the tangible common equity concept Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 12. Regulatory Capital Regulatory capital increases the numerator of a bank’s capital ratio in two ways compared with TCE First, it counts certain intangible assets like goodwill and tax loss assets that contribute to possible future profits but could not be sold by a failing firm to raise cash Second, it counts both common equity and hybrid capital (such as preferred stock) that is a mixture of Regulatory capital ratio = debt and equity. Hybrid capital is a 100,000/1,050,000 = 9.5%, less reliable cushion against loss than compared to tangible common common equity equity of 2% Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 13. Risk-Weighted Assets: Example For the denominator of the capital ratio, Basel II did not count all assets at full value Instead, assets were assigned risk weights according to their ratings Examples of the weights: AAA rated assets = 20% A rated assets = 50% BBB rated assets = 100% Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 14. Regulatory Capital vs. TCE Data in this chart compare regulatory In short, under Basel II regulatory capital ratios to TCE ratios for banks capital tended to understate the in Europe and the US just before the 2008 financial crisis leverage of bank balance sheets A bank might have tangible assets of 1,000,000 and tangible common equity of 20,000, giving a TCE ratio of 2% The same bank might have risk- weighted assets of just 500,000 and regulatory capital of 50,000, giving a regulatory capital ratio of 10% Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 15. Trying Again: Basel III In an attempt to fix the problems of Basel III, regulators have reached a new agreement, known as Basel III Proposed improvements include: A better measurement of capital, closer to tangible common equity (but not exactly) Requirements for banks to build extra capital reserves if early warning signs show abnormal credit growth or asset price bubbles Building of The Bank for International Settlements Photo source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BIZ_Basel_002.jpg Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 16. Will Basel III Succeed? Now the hard work has begun of translating the general principles of Basel III into specific regulations Preliminary proposals were tough, but banks are lobbying hard to weaken them Some observers are already starting to fear that Basel III regulations will once again be too easy on banks, laying the basis for another global financial crisis a few years down the road Revised version March 2013 Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog

- 17. Related slideshow: More on Financial Regulation and Basel III: Regulating Bank Liquidity For more slideshows and commentary, follow Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog Like this slideshow? Share it on Twitter Follow @DolanEcon on Twitter Click here to learn more about Ed Dolan’s Econ texts