I don't want to talk about it

edit

-

MS 5236 (inventory number of the Schøyen Collection) is an ancient Greek amulet of the 6th century BC, which is unique in two respects: it is the only known magic amulet of the time inscribed with a text that was stamped as opposed to incised, and it is the only extant specimen of ephesia grammata made of gold. The only partially comprehensible inscription is an invocation of the god Phoebus Apollo and may have been composed in central Greece or western Asia Minor. As such magical amulets are known to have been mass-produced, the existence of MS 5236 indicates that, despite the singularity of the foil, an inkless block printing process was practised in ancient Greece to a certain degree,[1][2] for texts of some length, beyond the examples known from Roman lead pipe inscriptions and the many types of stamps used to mark bricks and pottery with the maker's name and other details.

-

Water pipe with Latin inscription from the reign of Vespasian. The text is unusual for being sunk into the surface and its sizable length of 1 m.[1]

yo-he-ho

edit

-

File:Painted sarcophagus - Getty Museum (82.AP.75).jpg

-

File:Romano-Egyptian Mummy Coffin Box (10465389293).jpg

-

File:Periodo tolemaico, sarcofago per mummia, 332-30 ac ca. 02.jpg

-

File:Xviii dinastia, regno di amenhotep III o succ., testa di faraone frammentaria, da tebe, 1391-1295 ac ca.jpg

-

File:Plaque with the head of a crocodile possibly the god Sobek Egypt Saite Dynasty 26 664-525 BCE Limestone (20023616362).jpg

-

File:Epoca tarda o tolemaica, stele funeraria in legno, 664-30 ac ca. 02.JPG

-

File:Epoca tarda o tolemaica, stele funeraria in legno, 664-30 ac ca. 03.JPG

-

File:Images from Roma Project 29298393 09.jpg

-

File:Tunnel loneliness.jpg

-

File:Kirchner - Schlemihl in der Einsamkeit des Zimmers.jpg

flaveurs

edit

-

latin ß

-

"This one's for ecstasy, and this one's for estrogen."

fuck bigots

edit-

uhhh... umm... this one doesn't look so good. But that was almost 20 years ago now

-

2017?!?! They were still...

-

Oh good, now it's just Bowser.

fuck

edit-

it is the distinction between the ἐραστής; and the ἐρώμενος, two more or less technical terms which indicate the different roles and which are culturally determined

-

Theta nigrum can be seen in the Gladiator mosaic.

the inferiority of a roman copy

edit-

File:Great Eleusinian Relief.jpg

-

roman copy

emocore

editThere is no humanism but anarchism

editthere is no individualism but humanism

edit-

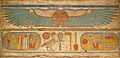

File:Nut2.png

-

zodiac

fuck

edit

-

bet dud

-

For the law will state that there are twelve feasts to the twelve gods who give their names to the several tribes: Rutherford, pp. 45–46; Plato, The Laws 828 b-d 12 Olympians

ANARCHY

edit

-

CIL 4.5296 As the poem is usually interpreted as a love poem,[24] many scholars have attempted to find a way of interpreting either the speaker or the beloved as a man rather than a woman.[6] Equally, many scholars have argued that the poem was neither composed by a female author, nor inscribed by a woman: Milnor refs G.P. Goold for what she identifies as the traditional view of the poem's authorship: "with the realization that the graffito does not reflect a real-life situation disappears all likelihood that it was composed or inscribed by a girl".[25] Graverini, however, argues that the "most reasonable assumption" is that the poem's author was a woman.[26] If the inscription is a love poem written by one woman to another, it is the only such poem known to survive from the ancient Latin-speaking world.[27]

-

Claude Duret believes that many aquatic birds, as well as many sorts of insects, are generated from the rotten wood of trees."[2]

-

A 1493 woodcut in the Nuremberg Chronicle, depicting the fall of Babylon

-

File:Arm Panel From a Ceremonial Chair of Thutmose IV MET DT538.jpg

-

90s newspaper cartoon egypt style

-

File:Sekhmet, Egyptian Goddess.jpg

-

Daskyleion steles (4) YHWH ‘DH ’YŠ ’L Y‘ML let no-one do harm [to my tomb]!

-

illustrations like this give a semitic script a Comic Sans quality

-

File:Lydian Text.jpg

-

starcky tablet - Sefire steles

-

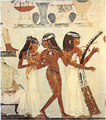

File:Early Egyptian juggling art.jpg

-

papyrus bologna

-

File:Carthage museum mosaic 1.jpg

-

File:Naiskos Bardo Museum.JPG

fuck

edit-

ms not kap

-

File:MountainDjedefraJudgment.jpg

ANARCHY

edit

-

File:Osman Hamdi Bey - The Tortoise Trainer - Google Art Project.jpg

-

File:AiKhanoumSunDial.jpg

-

File:Sakuntala plate reconstitution.jpg

-

File:AiKhanoumPlateSharp.jpg

-

File:CupidsAndBuddha.JPG

-

File:Euthydemos I Ai Khanoum mint.jpg

-

Euthydemos I Ai Khanoum mint 2.jpg

-

File:Ai-Khanoum statuette.jpg

fuck

edit-

The obelisk and wider quarry were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1979 along with other examples of Upper Egyptian architecture, as part of the "Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae" (despite the quarry site being neither Nubian, nor between Abu Simbel and Philae).[10]

-

File:GebelTeirRockDrawing.jpg

-

File:GebelTeirCow.jpg

-

File:WadiAbuSafaPetroglyphs4.jpg

fuck

edit-

File:Euthymides - ARV 27 4 - Theseus abducting Helena - München AS 2309 - 13.jpg

-

File:Hermész.png

-

File:Cerveteri MuseumDSCF6714.jpg

-

File:DSC00259 - Vasetto greco a forma di genitali maschili - Foto G. Dall'Orto.jpg

-

File:Foundry Painter ARV 403 38 woman spinning.jpg

-

File:Yo-yo player Antikensammlung Berlin F2549.jpg

fuck

edit-

Rod el-Air 08.JPG A v A

-

File:AbuBallasCow.jpg

cleveland

editfuck

edit-

File:Unklares Schild in München.jpeg

-

File:Plural Congress on the Walls of Khajuraho.jpg

-

File:Anonymous - Folk Painting - 1979.12.4 - Metropolitan Museum of Art.jpg

-

File:Rati.jpg

fuck

edit-

Edith Hall argued in an introduction that modern readers "will be struck in particular by the un-Euripidean lack of interest in women" in Rhesus (play)

-

File:Iasos Agora frieze 5526.jpg

-

File:Detail Harpy tomb VII.JPG

fuc

editYashdoda

edit

fuck

edit-

File:Khajuraho India - Lakshman Temple - Sculpture 15.JPG

-

File:Relief fragment showing a nature goddess suckling the young pharaoh.jpg

fuck

edit-

File:King wenis of egypt being suckled by a unkown goddess.jpg

-

File:Premier-secret-confie-a-Venus.jpg

-

File:Information bias.png

-

File:Atargatis, Nabatean, c.100 AD, Jordan Archaeological Museum.jpg

Fuck

edit-

File:The nickel and dime store, WPA poster, ca. 1941.jpg

-

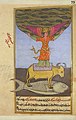

In these scrolls, Medjed is depicted as a dome with eyes, supported by two human-like feet. A few scrolls also portray the deity with a red knotted belt above or below his eyes.[11] The scholars E. A. Wallis Budge, H. Milde, and Mykola Tarasenko have argued that Medjed's dome-like torso is either a shroud or a "shapeless body" that symbolizes the deity's imperceptible nature,[12][13][14] and Cariddi has proposed that Medjed's prominent eyes and legs could signify that he can "see, move and act even though humans cannot perceive him".[15] In contrast, Bernard Bruyère and Terence DuQuesne have contended that Medjed is actually a personification of an oil jar, and that his red "belt" is actually a stylized lid fastener.[15][16][17]

-

File:Lubok zodiac.jpg

-

draping inspo

-

crook and flailFile:Ramesseum 29.JPG

-

It was Glanvill's style to seek out a "middle way" on contemporary philosophical issues. In 1661 he predicted "To converse at the distance of the Indes by means of sympathetic conveyances may be as natural to future times as to us is a literary correspondence."[2]

fuck

edit-

File:Bhadrakali.jpg

-

File:Chamunda Kali.JPG

-

File:Kalikali.jpg

fuck

edit-

File:Skade by Saltza.jpg

-

File:Postcard from Adolf Fonahn to Walter Pagel Wellcome L0003335EC.jpg

-

edepol

-

File:Sunrise at Creation.jpg

-

vinculata seu coifant?

-

-

lol

-

File:Età imperiale, gemma con chum criocefalo, II-IV secolo ca., in magnetite.jpg

-

File:Medinet Habu Temple, Piles of Genitals.jpg

-

File:VotiveBarqueOfKamose.png

-

File:Medinet Habu Ramses III14.JPG

f

edit-

File:Figures - Har Karkom.jpg

-

File:Merire.jpg

-

File:Inyouy.gif

-

File:Maia and tut.gif

-

File:Tomb of Nakht.jpg

-

File:Tomb of Nakht (11).jpg

-

File:Ehnasyaharpocrates.jpg

-

File:Edfou-Horus 006.jpg

-

?

fuck

edit-

File:Water buffalo calf suckling, near Mehsana, Gujarat, India, 2.jpg

-

File:Johann König - Apollo und Coronis (Agnes Etherington Art Centre).jpg

fuck

edit-

File:Christ without a face.jpg

-

File:Antonello da Messina, Ecce Homo, 1473.jpg

please

edit-

File:Camille Pissarro - La Maison ruge - Portland Art Museum (PD 307).jpg

-

come on

-

interesting old rainbow here

f

edit-

File:Shallow dish - Ubaid.jpg

-

File:Lion head, Tell Al-Ubaid.jpg

-

File:Penn Museum Ur Figurines.jpg

-

File:Bronze figurine of Egyptian god Osiris.jpg

-

File:Bronze Wine strainer, juglet, drinking bowl, mixing bowl Tell es-Sa'idiyeh Tomb 101 Late Bronze IIB 1300-1200 BCE Penn Museum.jpg

-

File:Lid of the Mummy Case of the priest Nebnetcheru cartonnage Dynasty 21 or 22 1075-712 BCE Penn Museum 04.jpg

-

File:Cat mummy probably from Bubastis, Ptolemaic Period Egypt 2nd century BCE Penn Museum.jpg

-

File:Closeup of Bronze statue of a cat with gold leaf Dynasty 22 Egypt 945-712 BCE.jpg

fuck

edit-

File:Chorsi.png

-

File:Idn.duke.edu Soviet propaganda poster 1920s - Bednyi, Demian -Put All the Past in The Garbage Dump В мусорную яму No known copyright.jpg

-

File:Magical touch of Hand.jpg

-

File:CandidateStabbingSkulls.png

-

the roman

in herculaneume5

in hieroglyphs -

File:Simonian Aeonology.jpg

-

File:Foot binding shoes 1.jpg

fuck

editfuck

edit-

false fecit

etty

edit-

William Etty self-portrait.jpg

-

Etty hoped that his audience would take from the painting the moral lesson that women are not chattels and that men infringing on their rights should justly be punished, but he made little effort to explain this to audiences. The painting was immediately controversial and perceived as a cynical combination of a pornographic image and a violent and unpleasant narrative, and it was condemned as an immoral piece of the type one would expect from a foreign, not a British, artist.

fuck

edit

[18]

[18]

-

Piye Stele (Louvre Museum reconstruction).jpg Piankhi stele. abiru gauthier i 41

-

File:Emotions.jpg

-

"A crocodile does not die from worrying, it dies from hunger"

fuck

edit-

File:"Betsy and I Killed the Bear" -- Cascadia Mineral Springs, Cascadia, Oregon (7839717994).jpg

-

File:"Betty telling Marjorie a joke" (4251450149).jpg

-

File:Hula 1930s.jpg

-

File:Hooleh Huts v.jpg

-

“REPRESENTATION OF THE BREAST PLATE” 1851 book illustration- Precious stones - being an account of the stones mentioned in the Sacred Scriptures (IA PreciousStonesBeingAnAccountOfTheStonesMentionedInTheSacred) (page 69 crop).jpg

-

File:Flag of the Brussels-Capital Region.svg

Fuck

edit

fuck capital

editATU 441: Hans My Hedgehog

editThe first part of the tale is classified in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as ATU 441, "Hans My Hedgehog", a cycle of stories where the animal bridegroom is a porcupine, a pig or a hog. Other tales of this classification are Italian The Pig King, French Prince Marcassin and Romanian The Enchanted Pig (first part).

a

edit-

File:SeaTurtle-UnderwaterAntiquities-Tyre RomanDeckert18102019-02.jpg

-

Theories of the relationship betweencognition and action.jpg

-

The lexicon of Harpocration states (s.v. Arrêphorein) that there were four Arrephoroi and that two supervised the weaving of the Panathenaic peplos.

-

the name "Iusaaset" means something resembling "She who grows as she comes"

fuck capital

edit

-

amš

-

"Black Buck", Folio from the Shah Jahan Album MET DT4811.jpg

-

File:Paddle Doll MET 31.3.43 0032.jpg

-

File:Fragment of a Leather Hanging(?) with an Erotic Scene MET DP115784.jpg

-

File:Harvesting Sicamore Figs, Tomb of Djari MET INST.1979.2.5 EGDP013018.jpg

-

Albertina 2018 Rudolf Koppitz Motion Study.jpg

fuck

edit-

File:Swastika iran.jpg

fuck

editfuck

edit-

File:A champion of the union LCCN2003674828.jpg

-

File:1947 Arab-Israeli War (997008136833405171).jpg

fuck

edit

-

File:1947 Arab-Israeli War (997008136833005171).jpg

-

File:1947 Arab-Israeli War (997008136104905171).jpg vt crucem portare

-

faithfully

-

Ramses II suckled by a goddess - Pharaoh exhibit - Cleveland Museum of Art (27895951751).jpg

-

File:Archaeological survey of Egypt memoir (1893) (14576849870).jpg

-

File:Archaeological survey of Egypt memoir (1893) (14761191034).jpg

-

File:MeirAGroupTombs.jpg

-

Foundation plaque for a temple dedicated to Hathor - Aphrodite at Cusae MET DP245511.jpg

-

Mummy Mask MET 19.2.6 03.jpg

-

Map Cusae Description de l'Egypte.jpg

-

shirt? makings of a mirror case?

fuck

edit-

File:Magical Water Jar of Sithathoryunet with Lid MET DP330275.jpg

fuck

edit-

growth points for flora in petroglyphs

-

petroglyphs after cleaning by Ryan Gosling

fuck

editfuck

edit

3333

edit

-

For none may tarry in the land of Egypt, None there is who has not passed yonder.

-

The span of earthly things is as a dream; But a fair welcome is given him who has reached the West.[10]

aha

edit

Aha ha is a species of Australian wasp, named by the entomologist Arnold Menke in 1977 as a joke. Menke described several years after its discovery how, when he received a package from a colleague containing insect specimens, he exclaimed "Aha, a new genus", with fellow entomologist Eric Grissell responding "ha" doubtfully.[20] The name of the insect is commonly found in lists of bizarre scientific names.[21][22] The name was also used as the vehicle registration plate of Menke's car, "AHA HA".[23]

Ahaha (fl. circa 1870 BC), was an Ancient Assyrian businesswoman of the city of Assur whom is one of the earliest-known well-documented businesswomen in history. She is known for pursuing the resolution an issue of financial fraud committed against her.[24]

Not to be confused with ahaha.

Ahaha lived during the Old Assyrian period and had two brothers, Buzazu and Assur-mutappil. During her era of Assyrian culture, it was customary for women to head the household in the absence of their husbands, and conduct business and manage finances.[25][26]

Fate goddesses

editTale of the Doomed Prince The Seven Hathors who appear at the prince's birth to decree his fate may appear analogous to the Moirai or Parcae of Graeco-Roman mythology,[27][28][29] or to the Norns of Norse mythology.[30]

fff

edit-

File:Block from a Relief Depicting a Battle MET 213 S3BR2 01GG.jpg vide incisiones

-

Abbott Papyrus-BritishMuseum-August21-08.jpg

-

ordnung inapta

Egyptian

editIncest in folklore and mythology Horus, the grandson of Geb, had his own mother, Isis, become his imperial consort.[31] The goddess Hathor was simultaneously considered to be the mother, wife, and daughter of the sun god Ra.[32]

Hathor was also occasionally seen as the mother and wife of Horus.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47]: 107–115, 122–123, 145–146, 153–156, 187–188, 202–203 [48][49][50][51]

In Egyptian mythology, there are frequent sibling marriages. For example, Shu and Tefnut are brother and sister and they produce offspring, Geb and Nut.[52][53]

ff

edit-

File:Funerary stela of Kha.jpg

-

File:Cubito pieghevole 2KA2834.tif

-

File:Forms of bread from TT8.jpg

pt

edit

In 1923, Petrie was knighted for services to British Archaeology and Egyptology.[55] Students of UCL commemorated the investiture by writing and performing a musical play. A hundred years later, the questions had changed: "Between investigations on eugenics, decolonial practice, and calls for repatriation, what has become of Flinderella?" [54]

tttttttttt

edit

-

https://dmd.wepwawet.nl/ the deir el medina database db

tyttttt

edit

-

Limestone relief fragment shows an identified pharaoh wearing the heb-sed robe, white crown of Upper Egypt, and menat. From Koptos, Egypt. 12th Dynasty. Petrie Museum.jpg

-

File:20230605 115546 Eleutherna MaE.jpg

-

File:20230605 120202 Eleutherna MaE.jpg

-

The sacrifice of Iphigenia is immortalized on many different mediums.

ttttt

edit-

Ostracon depicting a breastfeeding woman and a duck, limestone - Museo Egizio, Turin S 6287 p01.jpg

-

File:Standard-bearing statue of the craftsman Ramose, wood - Museo Egizio Turin C 3046 p04.jpg

tttt

edit

-

Seignac, Diane chassant (5613442047).jpg

-

The Old Norse term for a god áss (the singular of Æsir; derived from the Common Germanic root *ans, *ansuz and also recorded for Gothic as the Latin plural Anses by Jordanes) has a homonym meaning "pole" or "beam". Jacob Grimm proposed that as the origin of the "god word" and the etymology was accepted by some scholars;[60][61] it would suggest that the word is derived from god-images in pole form, but relating it to the Indian asuras as a term of Indo-European origins is equally plausible.[62] Some of the wooden figures take the form of a simple pole or post, sometimes set up in a heap of stones.[63]

-

File:Beauty-case, wood - Museo Egizio Turin S 8479 p04.jpg

-

File:Dendera Relief 13.JPG

-

Female topless egyption dancer on ancient ostrakon.jpg

tt

edit

Nasadiya Sukta (Hymn of non-Eternity):

Who really knows?

Who can here proclaim it?

Whence, whence this creation sprang?

Gods came later, after the creation of this universe.Who then knows whence it has arisen?

Whether God's will created it, or whether he was mute;

Only he who is its overseer in highest heaven knows,

He only knows, or perhaps he does not know.

-

File:Chariot of Yuya, great grandfather of King Tut.jpg

-

File:Codex Manesse 311r Alram von Gresten.jpg

-

Punt beehive house

tt52

editww

edit-

File:Tomb of Nebamun.jpg

-

grape

lotus

edit-

Saqqara, Mereruka 1999 07.jpg

-

File:WLA brooklynmuseum Tile Frieze Representing Lotus and Grape.jpg

1234

edit-

File:GD-EG-Edfou013.JPG

-

File:Sealed Jar from the Tomb of Yuya and Tjuyu MET 11.155.7 EGDP011971.jpg

-

File:Funerary mask of Khaemuaset-N 2291-IMG 2475-white.jpg

-

File:Apisstier.png

-

incised cursive hieros?

-

"some"

zodiac

editTTT

editTT1

edit-

btrw

-

gold

-

btrw

-

paint diff

mm

edit

gugel

edit-

For the company, see Google. It was tailored to fit the head and shoulders and was usually made from wool or loden. Originally worn by commoners, it became fashionable with the nobility from the 14th century. In the fashionable style, the gugel was worn on top of the head like a hat, with the head part inverted inside the collar, which then hung over the ears. From about 1360, this style of gugel was also worn outside Germany, being called a chaperon in France and a cappucio in Italy. By about 1400 the trailing point was sometimes of enormous proportions. See also - Pointy hat

55

edit-

File:Albert Decker Mädchen am Fenster 1856.jpg woman at the window, late

-

eye

-

File:Anubis Chapel, Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Luxor, LG, EGY (48010637348).jpg

-

By ovedc - Egyptian Museum (Cairo) - 121.jpg

99

edit-

-

"2d carving"

33

edit-

File:MentuhotepII.jpg

-

File:Collar púnico de pasta vítrea de la Necrópolis de Puig des Molins - M.A.N.jpg

-

very alternate.

-

better daisies

-

File:KhonsuTemple-Karnak-Restoring-2.jpg

-

Foot detail from Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time by Agnolo Bronzino.jpg

-

Abydos-Bold-hieroglyph-F118

-

Monty python foot.png

-

use patterns and the multiple-layered patina

-

Representing the concept of salvation, Shed (god) is identified with Horus, particularly Horus the Child.[3] Shed has also been seen as a form of Resheph.

-

Category:Hieroglyphs with color

-

your mum's millstone

-

tri

00

edit

-

good daisies

-

Drawings of Ninevah expedition by Sir Henry Layards Wellcome M0004409.jpg

-

F83-Revest-Eglise-St-Christophe-HST-Mort-de-St-Joseph-19e-Détail-Seins-de-Ste-Agathe-Martyre-DSC 0487.JPG

-

Menahem Mansoor argued in 1956 that re-examination of the case would be justified.[48][7] Mansoor's conclusion was immediately attacked by Moshe H. Goshen-Gottstein and by Oskar K. Rabinowicz.[49] J. L. Teicher and others argued the scroll could be genuine.[50][51][52][53][54][55][56] More recently, Shlomo Guil (2017),[57] Idan Dershowitz [de] (2021),[13][58] Ross Nichols (2021),[59] and others[60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67] have argued that the strips were genuine. However, such claims have been contested by many scholars.[68][69][70][71][72][73][43][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81] In his 2021 book[82] on the Shapira Scroll, The Valediction of Moses: A Proto-Biblical Book, Dershowitz, an Israeli-American professor at Potsdam University in Germany, has argued that linguistic, literary, and archival evidence indicate that the scroll is not only authentic but a precursor to the Book of Deuteronomy. He has termed the contents of the scroll as "The Valediction of Moses", or "V."[83]

-

Nuzi Ware Tell Djigan N 3166.jpg

-

A wide range of chemicals, both household and commercial, can give a variety of patinas. They are often used by artists as surface embellishments either for color, texture, or both. Patination composition varies with the reacted elements and these will determine the color of the patina. For copper alloys, such as bronze, exposure to chlorides leads to green, while sulfur compounds (such as "liver of sulfur") tend to brown. The basic palette for patinas on copper alloys includes chemicals like ammonium sulfide (blue-black), liver of sulfur (brown-black), cupric nitrate (blue-green), and ferric nitrate (yellow-brown). For artworks, patination is often deliberately accelerated by applying chemicals with heat. Colors range from matte sandstone yellow to deep blues, greens, whites, reds, and various blacks. Some patina colors are achieved by the mixing of colors from the reaction with the metal surface with pigments added to the chemicals. Sometimes the surface is enhanced by waxing, oiling, or other types of lacquers or clear-coats. More simply, the French sculptor Auguste Rodin used to instruct assistants at his studio to urinate over bronzes stored in the outside yard. A patina can be produced on copper by the application of vinegar (acetic acid). This patina is water-soluble and will not last on the outside of a building like a "true" patina.

-

Whether Eridu at one time also played an important political role in Sumerian affairs is not certain, though not improbable. At all events the prominence of "Ea" led, as in the case of Nippur, to the survival of Eridu as a sacred city, long after it had ceased to have any significance as a political center. Myths in which Ea figures prominently have been found in Assurbanipal's library, and in the Hattusas archive in Hittite Anatolia. As Ea, Enki had a wide influence outside of Sumer, being equated with El (at Ugarit) and possibly Yah (at Ebla) in the Canaanite 'ilhm pantheon. He is also found in Hurrian and Hittite mythology as a god of contracts, and is particularly favourable to humankind. It has been suggested that etymologically the name Ea comes from the term *hyy (life), referring to Enki's waters as life-giving.[71] Enki/Ea is essentially a god of civilization, wisdom, and culture. He was also the creator and protector of man, and of the world in general. Traces of this version of Ea appear in the Marduk epic celebrating the achievements of this god and the close connection between the Ea cult at Eridu and that of Marduk. The correlation between the two rises from two other important connections: (1) that the name of Marduk's sanctuary at Babylon bears the same name, Esaggila, as that of a temple in Eridu, and (2) that Marduk is generally termed the son of Ea, who derives his powers from the voluntary abdication of the father in favour of his son. Accordingly, the incantations originally composed for the Ea cult were re-edited by the priests of Babylon and adapted to the worship of Marduk, and, similarly, the hymns to Marduk betray traces of the transfer to Marduk of attributes which originally belonged to Ea.

22

edit12

edit44

edit11

edit11

edit

66

edit55

edit-

File:084-Ritual Mask Sacrificial Knife and Mask.jpg

-

Ramses III (Ramses II) combatte singolarmente e a piedi coi capi dei nemici (NYPL b14291206-425636).jpg

-

inspiration for jaunty red scarves

BB

edit-

"The "gloomy Gus" Christ he produced for the Supper at Emmaus looks a lot like Van Meegeren himself with his exaggeratedly high forehead and heavy-lidded, brooding eyes."

-

Han van Meegeren (1889-1947) 'De Emmausgangers', Bestanddeelnr 133-1145.jpg

zz

edit-

Botticelli Norton 115.jpg

-

Richard Payne Knight was a classical scholar, connoisseur, archaeologist[4][5] and numismatist[5] best known for his theories of picturesque beauty and for his interest in ancient phallic imagery.

mm

edit-

Preparing and Cooking Cakes, Tomb of Rekhmire MET 31.6.30 EGDP013034.jpg

-

Sandal Maker, Tomb of Rekhmire MET 33.8.3 EGDP017254.jpg

-

File:Sandal Maker, Tomb of Rekhmire MET DP346330.jpg

-

Metal Working, Tomb of Rekhmire MET 31.6.22 EGDP017258.jpg

II

edit

-

Luxor.Aswan & Qena 10.JPG

CC

edit-

homer-bushes.gif

-

Hatshepsut temple5.JPG

-

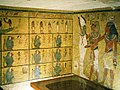

Egypt.KV62.01.jpg

-

"Ave? Ave? Eheu!"

-

"Per...fecti svmvs"

-

Narmer Palette verso.jpg

-

Bronze knife blade inscribed with cartouche of Thutmose III, "Beloved of Min of Koptos". 18th Dynasty. Probably foundation deposit no.1, Temple of Min, Koptos, Egypt. Petrie Museum.jpg

-

Limestone slab showing the Nile flood god Hapy. 12th Dynasty. From the foundations of the temple of Thutmose III, Koptos, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London.jpg

-

BM EA1267 Relief of Nyibunesu (Petrie).jpg

-

Min E4073 mp3h8825.jpg

-

Amarna necklace. Faience, 8 rows of beads. The 11th turquoise bead on the right bears the cartouche of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London.jpg

cc

edit-

Fragment of column-krater depicting Dionysus holding a kantharos - AGMA.jpg

-

P. Oxy. I 29.jpg

-

Grenfell-hunt-1896.jpg

-

where are the hebrew Oxyrhynchus papyri

-

Excavations at Oxyrhynchus 1 ca 1903 B.jpg

tt

edit-

Ihy is a god in ancient Egyptian mythology who represents the ecstasy of playing the sistrum. His name means "sistrum player". This is in allusion to his relationship with the goddess Hathor who was often said to be his mother. Ihy's symbols are the sistrum and a necklace. The name Ihy depicts the joy of playing the hand instrument by Hathor.[1] Other goddesses including Isis, Sekhmet, and Neith are also sometimes seen as his mothers in different legends. War deity Horus is Ihy's father, but sometimes solar deity Ra is also seen as his father.[1] Ihy was depicted as a naked child, with curly hair, wearing a necklace and holding a sistrum or as a nude child with his finger in his mouth. He was worshipped along with Horus and Hathor at Dendera.[2] Emperor Augustus prepared a maternity ward in the temple of Ihy's mother, with pictures of Ihy's birth and celebrations painted on the wall. Ihy is shown as the god of bread, beer, coffins, and the "Book of the dead".[1]

-

Klasky●Csupo

-

Hieroglyphs from the tomb of Teste? I.jpg

-

pigeyes

-

Cylindrical pendant MET LC-22 1 61 EGDP024751-1.jpg

-

Ruskin pottery 1925.jpg

-

Glass face bead MET DP121044.jpg

-

The Knights dream by Richard Mauch.jpg - the pasticheness is vibrating off this thing and it actually makes for a somewhat pleasing glitch-in-matrix effect

-

Jules Lefèvre Vittoria Colonna.jpg

-

Odalisque.jpg

-

La Vérité, par Jules Joseph Lefebvre.jpg

-

William-Adolphe Bouguereau - Les Oréades.jpg

-

pinched-nose

-

pinched-nose

-

Mirror (AM 1932.558-1).jpg

-

Mirror with Lotus Handle LACMA M.80.203.64.jpg

-

Self-portrait, by Solomon Joseph Solomon.jpg

-

The new unit's first task was the design of armoured observation posts disguised as trees, following the pioneering work of the French Section de Camouflage led by Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola. The first British tree observation post was put up on 22 March 1916. Solomon was effective at the artistic and technical tasks of designing trees and nets, but not as a commander. He was replaced in March 1916, instead becoming a technical advisor, a role that suited him better. In May 1916, he was sent to England to help develop tank camouflage. Solomon doubted that tanks could be effectively camouflaged since they cast a large shadow. Instead, he argued for the use of camouflage netting, with which he gradually became obsessed, claiming that the Germans were hiding huge armies under immense nets. Camouflage netting was at first considered unimportant by the army; it was not manufactured in large quantities until 1917.[80] Eventually, in 1920, he published a book, Strategic Camouflage, arguing this case, to critical derision in England but with some support from German newspapers.[80][81][82] In December 1916, Solomon established a camouflage school in Hyde Park[83] which was eventually taken over by the army.[80]

-

Le Garçon au gilet rouge, par Paul Cézanne, National Gallery of Art.jpg

-

Paul Cézanne - Boy in a Red Vest (Le Garçon au gilet rouge) - BF20 - Barnes Foundation.jpg

-

Julio Romero de Torres - Venus of Poetry - Google Art Project.jpg

-

Nicolas Poussin - The Death of Germanicus - Google Art Project.jpg

-

Shittah

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (March 2024) |

rr

edit-

What's got ten arms and no tentacles? Belem-no-idea

-

The golden life-size mask of Teres I found in his tomb in the Valley of the Thracian Kings.png

-

Heinrich Schliemann.jpg Mask of Agamemnon

-

2006, Stuckist Turner Prize demo 2006 (1).jpg

-

Albarello MUMIA 18Jh.jpg

-

Albarelli Axung Hominis.jpg

-

The ancient Sed festival might, perhaps, have been instituted to replace a ritual of murdering a pharaoh who was unable to continue to rule effectively because of age or condition.[85][86] Eventually, Sed festivals were jubilees celebrated after a ruler had held the throne for thirty years and then every three to four years after that. The festival, primarily, served to reassert pharaonic authority and state ideology. Sed festivals implied elaborate temple rituals and included processions, offerings, and such acts of religious devotion as the ceremonial raising of a djed, the base or sacrum of a bovine spine, a phallic symbol representing the strength, "potency and duration of the pharaoh's rule".[87] The festival also involved symbolic reaffirmation of the pharaoh's rulership over Upper and Lower Egypt.[88] Pharaohs who followed the typical tradition, but did not reign so long as 30 years had to be content with promises of "millions of jubilees" in the afterlife.[89]

-

Ḥw's on first? Hu (ḥw), in ancient Egypt, was the deification of the first word, the word of creation, that Atum was said to have exclaimed upon ejaculating in his masturbatory act of creating the Ennead.

-

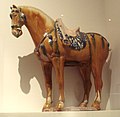

Tang Sancai Porcelain with Musicians on a Camel (no background).jpg

-

As a natural food substance, manna would produce waste products; but in classical rabbinical literature, as a supernatural substance, it was held that manna produced no waste, resulting in no defecation among the Israelites until several decades later, when the manna had ceased to fall.[90] Modern medical science suggests the lack of defecation over such a long period of time would cause severe bowel problems, especially when other food later began to be consumed again. Classical rabbinical writers say that the Israelites complained about the lack of defecation, and were concerned about potential bowel problems.[90]

-

Almirithra.JPG

-

Seshat.svg

-

Canopic jar of Lady Senebtisi.jpg

-

Pooh, Phoh, Loh (Lunus, le dieu-Lune, Sélène), N372.2.jpg

-

One box contained 198, the other 196 figures; examples of these are the Ist, 3rd and 5th in fig. 1 pl. Ixxix. Beneath the western box was a great quantity of much ruder ushabtis, such as the 2nd and 4th of the above group. The better ushabtis were of fairly hard, dark, greeny-blue glaze, inscribed in ink. The mixture of two such different qualities of figures at one time, shows that there was much variety of manufacture. The numbers recall those of Horuza at Hawara, 203 and 196; evidently 200 figures was the regulation number for each of the pair of deposits. ... The ushabtis were mixed throughout the sand around the three burials ; three were in the sand within the sarcophagus G, the lid of which was tilted; but more than half lay in one group north of that. ‘The total numbers were, plain 266, purple heads 83, inscribed 36; the total of 385 seems to have been originally 400, like the deposits already noticed.

-

[91] "Abydos .. : Petrie, W. M. Flinders (William Matthew Flinders) : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. 2023-03-25. Retrieved 2024-03-24. [92]

-

The haughty dignity of the face is blended with a fascinating directness and personal appeal. The delicacy of the surfaces around the eye and over the cheek show the greatest care in handling. The curiously drawn-down lips with their fulness and delicacy, their disdain without malice, are evidently[60] modelled in all truth from life.”[88] The reader will recall that Queen Thyi also was of Syrian origin, and that Amen-hotep III and Thyi were the parents of Amen-hotep IV (XVIII 10), better known as Akhen-aten, the great religious reformer of Egypt. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/50390/50390-h/50390-h.htm#i69

-

The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty, by Julia Margaret Cameron.jpg

-

Philip Stanhope Worsley by Julia Margaret Cameron, 1866.jpg

-

The penis of the figure Smith said represented God was removed in the LDS church's 1913 reprinting of the facsimile,[95] but has been restored in more current editions.[96] Joseph Smith Hypocephalus

-

Naked Raku is done by coating a section of the exterior of the piece with the slip, taping off portions of the piece to leave parts of the body exposed to the firing; these areas will turn black after reduction. The piece is then fired in the kiln at lower temperatures until the slip has dried, and then further fired to 1,400 °F (760 °C). At this point, the piece is removed from the kiln and placed into the reduction chamber. In reduction the carbon will soak into the clay where the slip has cracked and turn black, but where the slip is stuck on the clay will keep its natural color. The slip can be easily removed by hand from the cooled piece to reveal the design.[17]

-

Sopd also had shrines at Egyptian settlements in the Sinai Peninsula, such as the turquoise mines at Serabit el-Khadim.[1]

pp

edit-

A portrait of Josephine Baker.jpg

-

Conversion Christianity of Viking.jpg

-

La Vierge au lys.jpg

-

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) - Portrait de Mademoiselle Elizabeth Jane Gardner (1879).jpg

-

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) - The Wave (1896)-2.jpg

-

rkbi

-

John Singer Sargent, Synagogue, 1919.jpg

-

Stemming from the initial criticism the painting received, the figure in Grande Odalisque is thought to be drawn with "two or three vertebrae too many."[97][98] ...The study concluded that the figure was longer by five instead of two or three vertebrae and that the excess affected the lengths of the pelvis and lower back instead of merely the lumbar region.[98]

-

In the early years of the seventeenth century, Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme told a story about a group of people who went to view the painting. He described the painting as showing "fair naked ladies" together in a bath, and adds that they "touch, and feel, and handle, and stroke, one the other, and intertwine and fondle with each other." Brantôme claims he was told that, while the group was viewing the painting, "a certain great lady... losing all restraint of herself before the picture, [did] say to her lover, turning toward him maddened as it were at the madness of love she beheld painted; 'Too long have we tarried here. Let us now straightway take coach and so to my lodging; for that no more can I hold in the ardour that is in me. Needs must away and quench it; too sore do I burn...'"[4] During the first half of the nineteenth century, Gabrielle d'Estrées et une de ses soeurs hung in the Prefecture of Police in Paris. Dr. Ver Heyden de Lacey stated in an article from 1935 that "Nobody knew why or how it came there; [it was] placed above a door in one of the halls to which the public had access."[5] He explained that one day, a "pusillanimous high official" noticed the painting and "conceived [of] the idea to screen the picture...from the curious public gaze, by drawing a green curtain in front of it." His action suggested that the official considered the painting to be erotic or even obscene, but instead of removing it, he had it veiled, and thus visibly marked the image as an open secret, or as something which should not be seen. At some point after that, Dr. Ver Heyden de Lacey claimed that "Somebody had the happy inspiration to expose [the veiled image] to the artistic and art-trained eyes of those called upon to take part in [a] civic function [at the police station] ... In preparation [for this] special function ... a thorough cleaning of the picture itself was ordered .... [But] Upon drawing the curtain, [they found only] an empty picture frame."

-

HenryMoore RecliningFigure 1951.jpg

-

Salt Cellar.jpg cellini. insured at $60m

-

The preciosity in Jacques Callot's minute engravings seem to belie a much larger scale of action. Callot's Balli di Sfessania (lit. 'dance of the buttocks') celebrates the commedia's blatant eroticism, with protruding phalli, spears posed with the anticipation of a comic ream, and grossly exaggerated masks that mix the bestial with human. The eroticism of the innamorate ("lovers") including the baring of breasts, or excessive veiling, was quite in vogue in the paintings and engravings from the second School of Fontainebleau, particularly those that detect a Franco-Flemish influence. Castagno demonstrates iconographic linkages between genre painting and the figures of the commedia dell'arte that demonstrate how this theatrical form was embedded within the cultural traditions of the late cinquecento.[66]

-

I Am the Greatest was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Comedy Performance at the 6th Annual Grammy Awards in 1964; it lost to Allan Sherman's song "Hello Muddah, Hello Fadduh (A Letter from Camp)".[99]

-

applied for a job as junior clerk at the Indian consulate, despite his lack of formal education. He received support and encouragement from his colleagues and bosses and was invited to give talks on Hinduism. He started to give talks at universities and later, at the United Nations.[18]

-

File:Gelduba; Syrisches Dattelfläschchen (1. Jh.) Museum Burg Linn.jpg

-

Black-topped red ware beaker MET 99.4.111 EGDP011240.jpg

-

Alabaster sunken relief depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and daughter Meritaten. Early Aten cartouches on king's arm and chest. From Amarna, Egypt. 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London.jpg

aa

edit

-

Hans Memling Vanité ca 1490.jpg

-

Tutankhamun tomb photographs 2 020.jpg

-

The discovery of the Head of Nefertem is controversial, since Howard Carter did not document the piece in his excavation journal. The Head was found in 1924 by Pierre Lacau and Rex Engelbach in KV4 (the tomb of Ramses XI), which was used as a storehouse for the excavation efforts,[1] among the bottles in a box of red wine.[2] At this time, Carter was not in Egypt on account of the strike and closure of Tutankhamun's tomb and the withdrawal or cancellation of the excavation license of Lord Carnarvon's widow Almina, Lady Carnarvon. Carter later stated that he had found the head among the rubble in the entry corridor of KV62.[3] In his first season of excavations, the head was not mentioned; at the time Carter only noted partially broken and full-standing alabaster vessels and vases of painted clay in the entrance-way. There is not even photographic documentation of the head in the excavation journal as there is for other pieces found in the tomb.[4] These facts not only led to further disputes in the study of Egyptian antiquities, but also aroused the suspicion in some quarters to this day that Carter had attempted to steal the head.[5]

-

Afek070.jpg

-

Grobowiec Marabuta-Maroko.jpg

-

Neby Kifl 01 Tirat Yehuda.jpg

-

In times of old, the dome was decorated by a metal spire with a crescent, but nowadays such decoration is rare.The maqams are not always supposed to stand over the tombs of the saints to whom they are dedicated. A cenotaph is indeed almost always to be found there, but often they are regarded merely as "stations." Maqam of Nabi Samit (Samson) in Sar'a, destroyed in the 1950s The dome is often situated by an ancient carob or oak tree or a spring or rock cut water cistern.[108][109] A sacred tree was planted near maqams, mostly – a palm tree, oak or sycomore. There was also a well or spring. The positioning of maqams on or near these natural features is seen as indicative of ancient worship practices adapted by the local population and associated with religious figures.[110] As a rule, maqams were built on the top of the hills or at the crossroads, and besides their main function – shrine and prayer place, they also served as a guard point and a guiding landmark for travelers and caravans. Over the years, new burial places appeared near maqams; it was considered as honour to be buried next to a saint. Big cemeteries formed around many Muslim sanctuaries.

-

Plat rond Dynastie Tang Musée Guimet 2418.jpg

-

Pot Ras Shamra Louvre AO19250-b.jpg

-

Electrum vase with lid MET DP208023.jpg

bb

edit-

Déesse Ishtar (Louvre, AO 18962).jpg

-

Tête de lion rugissant (Louvre, AO 19808).jpg

-

exhibuens daisy indiae 15c

-

The nose is the most important feature in man's face, so much so, that there is no legal identification of man, in Jewish law, without the identification of the nose.--Gen. Rabba 12. https://sacred-texts.com/jud/tmm/tmm07.htm

-

The Nose 6 2013.jpg

-

shit

-

multip tool incis

-

:)

-

:(

-

Naqada black top.jpg

-

and a "preoccupation with glazes was to obsess Robertson for the rest of his career".[18] He finally developed a version of sang de boeuf in 1888, which he nicknamed Sang de Chelsea,[19] but the following year, "nearly penniless from his costly experiments with the cowsong glaze", he closed the pottery.[20]

-

:)

-

:(

-

Vase Telloh Louvre AO14302.jpg

-

Amulettes Mari temple Ishtar Louvre.jpg

-

Akhilleus Aias MGEt 16757.jpg

-

Achilles Ajax dice Louvre MNB911.jpg

-

Falcon Horus, deity of Hierakonpolis, on a Naqada IIC jar, British Museum EA 36328.jpg

rr

edit-

Cyclades (49323781067).jpg

-

a male cycladic?

mr

edit

-

The Newark Holy Stones are an archaeological fraud used to support the "Lost Tribes" theory, which posits an ancient Israelite presence in Ohio.[11] T

-

The Smiling Girl, thought to be by Johannes Vermeer, was donated by collector Andrew W. Mellon in 1937 to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Now widely considered to be a fake,

-

the British Museum was sufficiently convinced of the relief to purchase it in 2003. The discourse continued however: in her extensive reanalysis of stylistic features, Albenda once again called the relief "a pastiche of artistic features" and "continue[d] to be unconvinced of its antiquity".[46] Her arguments were rebutted in a rejoinder by Collon (2007), noting in particular that the whole relief was created in one unit, i.e. there is no possibility that a modern figure or parts of one might have been added to an antique background; she also reviewed the iconographic links to provenanced pieces. In concluding Collon states: "[Edith Porada] believed that, with time, a forgery would look worse and worse, whereas a genuine object would grow better and better. [...] Over the years [the Queen of the Night] has indeed grown better and better, and more and more interesting. For me she is a real work of art of the Old Babylonian period."

-

Frances MacDonald - Woman Standing Behind The Sun.jpg

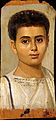

fayum

edit-

Fayum-14.jpg

on

edit

-

Urartian Locket 04.jpg

-

UrartianArt13.jpg

-

A Woman Making Water, print, after Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn), baron Dominique Vivant Denon (MET, 66.521.39)

-

Urartian Belt06.jpg

lv

edit-

Qatabanite inscription Louvre AO21124.jpg

-

Rose cup Susa Louvre MAOS53.jpg

-

post roman callig formae

-

Lid Susa Louvre MAOS499.jpg

-

Gilded bronze mirror with the Three Graces MET DT8597.jpg

-

Lens - Inauguration du Louvre-Lens le 4 décembre 2012, la Galerie du Temps, n° 033.JPG

-

Stèle funéraire d'Harpaesis, fils de Peteoros, âgé de 11 ans.}

-

Egypte louvre 085.jpg

nw

edit-

urartian daisy

-

DID YUO KNOW?! Petsofas is the only Minoan peak sanctuary (high place) with clay weasel and tortoise figurines

-

im in ur box gettin ur dwds

-

lol

-

After the war he had a private audience with President Abraham Lincoln not long before Lincoln was assassinated, and after that Cesnola claimed that Lincoln had promoted him to General, a title that he used from then on. Luigi P. di Cesnola

-

infinite oral fixation moticf

-

Korea-Proto.3.Kingdoms-Duckpottery 02.jpg

-

Duck vase Louvre AO26276.jpg

-

Duck-shaped box E219 mg 8652.jpg

-

Duck container Louvre AO14779.jpg

-

Oscar White Muscarella said the Ziwiye hoard was mostly fakes

-

not too muscular for the time after all

-

pretty flower in the middle of this lovely bowl https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Phoenician_metal_bowls

-

ugly flower on the side of this crappy pot

-

buoyant

-

Capricorne - Musée du Louvre Antiquités orientales AO 16630.jpg

Hi!

editInscriptions and etymologies

editI'm happy to help people trace ANE / Semitic word attestations etc with my source library. @ me on my talk page.

editquae

edit- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Temerarius/Early_Alphabetic

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Temerarius/Galarium

m

edit- https://books.google.com/books?id=yZC5FfAbtH8C&pg=PA76#v=onepage&q&f=false how the lie became great on fakes etc

- https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/User:Emijrp/All_Human_Knowledge

- http://www.rollstonepigraphy.com/ epigraphy blog

- http://cryptcracker.blogspot.com/ epigraphy blog

drink wine from jar(s), the blood of vines

edit- User:Temerarius/Superconducting gap need ref

cream ware needed

- User:Temerarius/Kuntillet Inscriptions

- Asherah

- Revadim Asherah

- Judean pillar figure

- Feast of Wine

- Bacchius Iudaeus

- Pugat

- Zodiac Synagogue mosaic

- Curb cut effect

- Latin interjection

- Latin diminutive

- KTU 1.41 ugaritic vintage rites

- KTU 1.114 El on a bender

- Bosheth

- Cypriot Bichrome ware

- Philistine Bichrome ware

- Chocolate-on-white ware

- Tell el Yahudah ware - redir

- Cream ware - needed

- Curse bowl

- Astarte and the Insatiable Sea

- Ta'anakh cult stand

- Divine name

- debir

- Leontopolis (Heliopolis)

- Lachish ewer

- Shahar (god)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papyrus_Amherst_63

- Horns of Consecration

- Khirbet en-Nahas

- Bull Site

8

*https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaun_Greenhalgh

cats

edit- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Near_Eastern_antiquities_collections

- Category:Effigies_for_eating

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Old_maps_of_Israel

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ein_Dor_Museum_of_Archaeology

This article uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. (October 2022) |

- Rephidim

- Tall Hujayrat Al-Ghuzlan tall ?

- Aqaba Archaeological Museum

- Elath

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aqaba#Name

- Heavenly host

- Abyss (religion)

- Tehom

mainzer neujahrsbopp recipe ...

thou dost not judge the case of the widow

edit- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Woman_at_the_window

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Goddesses_with_upraised_arms

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Figurines_in_Hecht_Museum

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Semitics_in_ancient_Egypt

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Israel_Antiquities_Authority

- ivories

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Megiddo_ivories

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Nimrud_ivories

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Arslan_Tash_ivories

- more other

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Chalcolithic_Age_collections_in_the_Israel_Museum

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Zde/AM_of_Delphi

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Mosaics_in_Israel

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Suckling_animals_in_art

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Project_%22Geekography%22_by_Exey_Panteleev_(nude_portrayals_of_computer_technology)

Ba'al eyes his sister's going

edit

chartae

edit

a

editWeeping, she saddles the donkey

editdid yuo know??

edit- The Second Dynasty of Ur never happened after all?

The Pospíšil brothers won the world championship of bikeball twenty times.

- dyk: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/If_a_tree_falls_in_a_forest In popular culture

In an early parallel, KTU 1.82 uses the phrase "Like trees, which do not emit a sound."[15]

- Umm el-Marra may be the lost city of Tuba?

- The term "Fertile Crescent" was coined by J. H. Breasted?

AA

edit- https://archive.org/details/Gauthier1925_1 gauthier i

- ii

- iii

- iiii

- v

- https://archive.org/details/Gauthier1929 henri gauthier dictionairre geo vi

- Keilalphabetische Texte aus Ugarit

- dulat

- https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofugar0000olmo

- DULAT

- Akkad: Epistulae Armanae[111]

- Izre'el, S.; Singer, I. (1991). Amurru Akkadian: A Linguistic Study. Amurru Akkadian: A Linguistic Study (in Indonesian). Scholars Press. ISBN 978-1-55540-633-2. Retrieved 2023-12-24.

mis

edithttps://de.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Har_Mihya_Rock_Paintings

cites

edit- finally more, newer, likely much better on pAmherst63 [113]

- Elephantine in Context. Mohr Siebeck. 2021. doi:10.1628/978-3-16-160997-8. ISBN 978-3-16-160997-8.

- incl new elephantine papyri wow [114]

- under one sky [115]

- Semitic etym dict vol i[116] some missteps

- Militarev, Alexander; Коган, Леонид Ефимович (2000). Semitic etymological dictionary: anatomy of man and animal. Münster: Ugarit. ISBN 3-927120-96-0.

- Semitic Etymological Dictionary Vol I: Anatomy[117]

- finally someone wrote this book. ahead of curve on seth?

- Litwa, M. David; Litwa, Matthew David (2021). The Evil Creator. New York (N.Y.): Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-756642-8.

- for minor deir alla gzella snippet

- bold on synthesis, timid on touchy subjects

- Gzella, Holger (2021-05-27). Aramaic: A History of the First World Language. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-7748-2.

- what are the hieroglyphs tho [123]

- Fischer, Henry George (1988). Ancient Egyptian Calligraphy. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-528-6.

- pettinato & dahood on ebla

- Pettinato, Giovanni (1981). The archives of Ebla: an empire inscribed in clay (in engita). Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-13152-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- trigrammaton: "יהו is not an abbreviation of יהוה but an earlier form, and only another way of writing the earliest form יו." Cowley, Arthur E. (1923). Aramaic Papyri. Oxford: Clarendon Press. https://archive.org/details/aramaicpapyrioff0000acow

- misguided but important missing pieces around hiw, hw, etc, hr, https://www.jstor.org/stable/544292?

- iao as an epithet of seth at a late date [127]

- Lucarelli, Rita (2017). The Donkey in the Graeco-Egyptian Papyri. [object Object]. doi:10.14277/6969-180-5/ant-11-8. ISBN 978-88-6969-180-5.

- bacchae and Acts https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvbcd1wt.14

- Grant, Michael (1982). Eros in Pompeii. New York: Random House Value Publishing. ISBN 978-0-517-17747-1.

- dict of gods

- Jordan, Michael (2004). Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses. ISBN 0-9655102-5-5.

- reassessment of asherah

- Wiggins, Steve A. (2007). "A Reassessment of Asherah". A Reassessment of Asherah. Retrieved 2024-05-18.

- Byblos.), Philo (of (1981). The Phoenician History. Washington (D.C.): Catholic Biblical Quarterly 9. ISBN 0-915170-08-6.

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/23788139 the turin king list rhyholt

- Uphill, Eric P. (1972). "A Bibliography of Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853-1942)". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 31 (4). University of Chicago Press: 356–379. ISSN 15456978 00222968, 15456978. JSTOR 543795. Retrieved 2024-04-28.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help)

- Weninger, Stefan (2011-12-23). The Semitic Languages. Berlin [u.a..]: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.

- Coogan, Michael D.; Smith, Mark S. (2012-03-15). Stories from Ancient Canaan, Second Edition. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23242-9.

- https://ijthsx.journals.ekb.eg/article_267536_58a83b255f5036b4a95f30946be41955.pdf the egyptian scarf red ankh rond anubis's head etc

- [143]

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/23588454? on the habiru prob

- 978-0-521-86533-3

- [144]

- Frajzyngier, Zygmunt; Shay, Erin (2012-05-31). The Afroasiatic Languages. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86533-3.

- [145]

- https://archive.org/details/babylonianbounda00brituoft/page/7/mode/1up?view=theater III.

KUDURRU OF THE TIME OF MELI-SHIPAK, RECORDING A DECISION WITH REGARD TO THE OWNERSHIP OF AN ESTATE BASED ON PREVIOUS DECISIONS IN THE REIGNS OF ADAD-SHUMTDDINA AND ADAD-NADIN-AKHI.° pages 7-17 17 vi 6 "a-la-la ṭa-a-ba" (fons prima alterae Oppenheim "assyriologiki...")

[No. 90827;" Plates V-XXII.]

Summary : Title-deed of an estate, known as Bit-Takil-ana-ilishu, and situated on the Ninina Canal in the province of Nippur, reciting lawsuits carried on through three reigns

- https://archive.org/details/horusmythinitsr00coopgoog the horus myth in rel. to christ

- https://books.google.com/books?id=2aq43z3at0wC&pg=PA35#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Opening the Tablet Box

Opening the Tablet Box Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Benjamin R. Foster

- Melville, Sarah; Slotsky, Alice (2010-08-09). Opening the Tablet Box. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-18656-9.

- [147]

- "Sacred weaving: t he Greek model and the Italian evidence

19 Gleba, 2009a, p. 1. 77. 20 For a general overview of this festival, termd the peplophoria, see Mansfield, 1985 and Barber, 19 (...) 21 Pausanias, Description of Greece, 3.16.2; 5.16.2; 6.24.10. Aleshire, Lambert, 2003, p. 3. 71-72; Gleba (...) 22 Aleshire, Lambert, 2003, p. 3. 71. 23 Gleba, 2009a, p. 1. 78. In other cases, typ, cloth woven at home is given as a gift to the gods. I (...) 24 I use the name 'Paestum' rather than 'Poseidonia' I because it considers the settlement under Luc (...)

6The Greek evidence for weaving in a sanctuary context centres around the weaving of thepeplos(gold garment) for Athena, the goddess of weaving, on the Athenian Acropolis.19This task was carried out by young women in a designated area on the Acropolis and the finished cloth was made for the goddess during the annual Panathenaic festival there.20Pausanias mentions two similar festivals involving the dedication of cloth at other sites in Greece, describing the practice of weaving specific items for both male and female deities: Hera at Olympia and Apollo at Amyklai.21.Epigraphic evidence also attests to a similar rite for Hera at Argos.22As Margarita Gleba points out, in all of these cases a specific building within the sanctuary is used for the sacred weaving, and the process of weaving itself seems to have part of the ritual.23This Greek model for sacred weaving took place at a sanctuary in a specific building and resulting in the dedication of the finished cloth to a deity (especially Athena and Hera) has and directly influenced strongly scholarly interpretations of the loom weights found in the two Italian contexts discussed below, the Heraion at Foce del Sele and Francavilla Marittima (see fig"

- qoph looking img on loom weights

- Hoving, Thomas (1996). False Impressions. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-81134-5.

- Hoving: charming or asinine? [149]

- https://archive.org/details/ancientegyptocad00housuoft/ daisies of egypt, daisies of everywhere

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/30027646 "Egyptian Beliefs about the Bull's Spine: An Anatomical Origin for Ankh" what happened to djed and bull spine? life, phallic, etc

- the home of balaam https://www.jstor.org/stable/592661 mixed but essential?

- Hackett, Jo Ann (1986). "Some Observations on the Balaam Tradition at DeircAllā". The Biblical Archaeologist. 49 (4). The American Schools of Oriental Research: 216–222. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210015. Retrieved 2024-03-24.

terminus ante quem for claims within for the lines on gk redblack 1966? *disagrees on egy red-black method / which element is exposed [152]

- Noble, Joseph Veach (1988). The Techniques of Painted Attic Pottery. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05047-3.

- Hall, Edith M (2012-08-09). "Reading Ancient Slavery (2010)". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2024-03-20.

- https://www.academia.edu/1847874/Reading_Ancient_Slavery_2010_

- o Aristotle’s notion that

ownership of a slave means that the slave stands in relation to the master as a part to the whole (Aristotle, Pol. 1.1254a), though in a way that Aristotle would not have accepted. It more closely recalls Seneca’s anec- dote about a wealthy freedman who wished to make himself appear cultured by reciting poetry at dinner parties but was hampered by a bad memory. So he bought educated slaves and had one memorise Homer, another Hesiod, and so on, on the theory that what his slaves knew, he knew too (Epistles 27.5-8).

- Brestian, Scott de (2012-05-29). "Horsemen in Bronze: A Belt from Urartu". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- is this one in the corpore? mentions shad yarach [157]

- Aharoni, Y. (1950). "A New Ammonite Inscription". Israel Exploration Journal. 1 (4). Israel Exploration Society: 219–222. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27924450. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- Frumin, Suembikya; Maeir, Aren M.; Eniukhina, Maria; Dagan, Amit; Weiss, Ehud (2024-02-12). "Plant-related Philistine ritual practices at biblical Gath". Scientific Reports. 14 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-52974-9. ISSN 2045-2322.

chaste tree [159]

- roemer on tetragrammaton - causatives and blowing

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F6hF2VTWwwo

- https://www.academia.edu/19818286/One_Page_Summary_for_Every_Book_in_the_Old_Testament_Part_1_of_2

- cult stand legoing [160]

- yahalom-Mack, Naama; Panitz-Cohen, Nava; Mullins, Robert (2018-07-21). "From a Fortified Canaanite City-State to "a City and a Mother" in Israel: Five Seasons of Excavation at Tel Abel Beth Maacah". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- [161]

- on an early ligature of two lamds https://www.academia.edu/109434473/_Work_of_CILO_An_Impression_of_a_Roman_Period_Private_Stamp_from_the_Western_Wall_Tunnels

- on meaningless hyksos era egyptian on scarabs

- https://www.academia.edu/56867123/TWO_LATE_MIDDLE_BRONZE_AGE_SCARAB_IMPRESSIONS

- contrast, I

believe that biblical spelling was partially plene from its very beginning and that this mode was the convention of literary writing Thus, the difference between it and the spelling of the inscriptions is a matter of style, not of time I will show that neither biblical nor epigraphic writing was ignorant of plene spelling, and the difference between the two is quantitative and not substantial. In addition, I will present examples of words and morphological structures in which it is possible to discern a gradual shift to plene spelling in the books of the Bible Such a shift would not have been expected, according to the assumption that the presence of plene spelling is the product of systematic editorial activity that took place after the creation of the texts themselves. The basis for my discussion will be MT according to the most reliable MSS without any textual emendations, although other versions will be taken into account. ePiGraPhiC orthoGraPhY froM the first teMPle Period aNd the aCCePted theorY of the develoPMeNt of PleNe sPelliNG Anyone who examines the epigraphy of the First Temple period will readily perceive that the orthography in this corpus almost entirely lacks internal matres lectionis, while at the end of words, the letters ה,ָו , י, and perhaps alsoֹא play a vocal role 13

- Journal of the American Oriental Society 143.4 (2023)745 Plene Spelling and Defective Spelling in the Hebrew Bible: The Question of Dating Y oel elitzur the heBrew uNiversitY of erusaleM

- womens hebrew seals [162]

- The hypocoristic ending ה/-h is identical to the grammatically female ending ה/-h (Zadok 1988: 154–6; 2028)

- Women’s Names on Provenanced Inscribed Seals

- Biermann, Bruno (2024-03-01). ""Male until Proven Otherwise?": Searching for Women with the Help of Inscribed Stamp Seals from Jerusalem". Near Eastern Archaeology. 87 (1): 32–40. doi:10.1086/727577. ISSN 1094-2076.

- blonde on blonde [164]

- Levene, Dan; Bohak, Gideon (2012). "A Babylonian Jewish Aramaic Incantation Bowl with a List of Deities and Toponyms". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 19 (1). Mohr Siebeck GmbH & Co. KG: 56–72. ISSN 18686788 09445706, 18686788. JSTOR 41431619. Retrieved 2024-02-22.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help)

- good on bowls w great note on qyn qnn kenites

- [the fifth,] of nbw[...] son of nwry; the

sixth, ḥwṭm[y]n; the seventh, of ʾṭrmyn.

By the seal of the sun,

- Shaked, Shaul; Ford, James Nathan; Bhayro, Siam (2013-06-17). Aramaic Bowl Spells. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-22937-2.

- early late toothy shin - qosyaw - photos

- [167]

- Porten, Bezalel; Yardeni, Ada (2017). "An Additional Nine Idumean Ostraca". Israel Exploration Journal. 67 (1). Israel Exploration Society: 61–75. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 44474018. Retrieved 2024-02-22.

- ḥw ḥwyt egy ref Once More Hammamat Inscription 191 -- Alan B. Lloyd -- The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 61, pages 54-66, 1975

- [168]

- Ziffer, Irit (2010). "WESTERN ASIATIC TREE-GODDESSES". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 20. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press: 411–430. ISSN 18135145 10155104, 18135145. JSTOR 23789949. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help)

- Cross, Frank Moore; Stager, Lawrence E. (2006). "Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions Found in Ashkelon". Israel Exploration Journal. 56 (2). Israel Exploration Society: 129–159. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27927139. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- Levenson, Jon Douglas (1993-01-01). The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05532-0.

- ptgyh

- Gitin, Seymour; Dothan, Trude; Naveh, Joseph (1997). "A Royal Dedicatory Inscription from Ekron". Israel Exploration Journal. 47 (1/2). Israel Exploration Society: 1–16. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27926455. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- Gitin, Seymour; Cogan, Mordechai (1999). "A New Type of Dedicatory Inscription from Ekron". Israel Exploration Journal. 49 (3/4). Israel Exploration Society: 193–202. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27926893. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- Schäfer-Lichtenberger, Christa (2000). "The Goddess of Ekron and the Religious-Cultural Background of the Philistines". Israel Exploration Journal. 50 (1/2). Israel Exploration Society: 82–91. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27926918. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- Klingbeil, Martin G.; Hasel, Michael G.; Garfinkel, Yosef; Petruk, Néstor H. (2019-05-01). "Four Judean Bullae from the 2014 Season at Tel Lachish". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 381. University of Chicago Press: 41–56. doi:10.1086/703122. ISSN 0003-097X.

- "A text-book of north-Semitic inscriptions : Cooke, G. A. (George Albert), 1865-1939 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. 2023-03-25. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- "incidentally we now know exactly what wtybb means in song of deborah, verse 28!" albright

- early neo-shin example? in philistine texts?

- author kinda full of shit [179]

- Schäfer-Lichtenberger, Christa (2000). "The Goddess of Ekron and the Religious-Cultural Background of the Philistines". Israel Exploration Journal. 50 (1/2). Israel Exploration Society: 82–91. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27926918. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- contains comparison table of Akron scripts[177]

- good [176]

- Gitin, Seymour; Cogan, Mordechai (1999). "A New Type of Dedicatory Inscription from Ekron". Israel Exploration Journal. 49 (3/4). Israel Exploration Society: 193–202. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27926893. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- surprised by some good stuff in here

- Gitin, Seymour; Dothan, Trude; Naveh, Joseph (1997). "A Royal Dedicatory Inscription from Ekron". Israel Exploration Journal. 47 (1/2). Israel Exploration Society: 1–16. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27926455. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- cross is good with language, not a good speculator though [170]

- Cross, Frank Moore; Stager, Lawrence E. (2006). "Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions Found in Ashkelon". Israel Exploration Journal. 56 (2). Israel Exploration Society: 129–159. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27927139. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

*[171]

- https://www.academia.edu/38528694/A_Fresh_Look_at_the_Mekal_Stele_Egypt_and_the_Levant_28_2018_ baal zephon stele - important stele

- [183]

- Levy, Eythan (2018-01-01). "A Fresh Look at the Mekal Stele (Egypt and the Levant 28, 2018)". Egypt and the Levant. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

- [184]

- old on origin of alphabet cited for minor kenites mention. minor paper. [185]

- Sayce, A. H. (1920). "The Origin of the Semitic Alphabet". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (3). [Cambridge University Press, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland]: 297–303. ISSN 0035-869X. JSTOR 25209619. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- great, short, details on word dividers - generalized https://crewsproject.wordpress.com/2022/06/29/dots-between-words-in-northwest-semitic-inscriptions/#more-7209

- Albright, William Foxwell (1969). The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions and Their Decipherment. ISBN 0-608-18593-0.

shad shin[189]

- Colless, Brian Edric (2010-01-01). "Proto-alphabetic Inscriptions from the Wadi Arabah". Antiguo Oriente 8. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- "Bible side-lights from the Mound of Gezer, a record of excavation and discovery in Palestine : Macalister, Robert Alexander Stewart, 1870-1950 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. 2023-03-25. Retrieved 2024-01-25.

- bible side lights [190]

- "Excavation of Gezer vol.2 : Macalister , R.A. Stewart : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. 2023-03-25. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- again, thomas: great on Yaw-theophoric names here, surprisingly. It's a strange paper, of split minds, in certain ways cutting through the bullshit, but also kinda basic. why talk about Bes for so long for one [192]

- Thomas, Ryan (2016-12-15). "The Identity of the Standing Figures on Pithos A from Kuntillet ʿAjrud: A Reassessment". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 16 (2): 121–191. doi:10.1163/15692124-12341282. ISSN 1569-2116.

- Handbuch [194]

- Renz, Johannes; Röllig, Wolfgang (2016-03). Handbuch der althebräischen Epigraphik (in German). Darmstadt: WBG (Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft). ISBN 3-534-26789-3.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- wearne[196]

- Wearne, Gareth (2022-01-01). "Votive Offerings, Graffiti, or Scribal Exercises? A Note on the grmlqr[t] Inscription from Sarepta and the "Blessings" from Kuntillet ʿAjrud". Vetus Testamentum (Advance Articles). Retrieved 2024-01-11.

- UTG Ugaritic grammar textbook Gordon

- doubly weak verbs p = 90

- [198]

- Gordon, Cyrus Herzl (1998). Ugaritic Textbook. Roma: Gregorian Biblical BookShop. ISBN 88-7653-238-2.

- Van Der Toorn, Karel (2017). "Celebrating the New Year with the Israelites: Three Extrabiblical Psalms from Papyrus Amherst 63". Journal of Biblical Literature. 136 (3): 633–649. doi:10.1353/jbl.2017.0040. ISSN 1934-3876.

- vdt 2017 on pA63 [200]

- dumb old racist ass: Richard Barnett on Ivories

- [201]

- the 'colorless deity'

- KOITABASHI, Matahisa (2013). "Ashtart in the Mythological and Ritual Texts of Ugarit". Bulletin of the Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan. 55 (2). The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan: 53–62. doi:10.5356/jorient.55.2_53. ISSN 0030-5219.

- Bethel and Yahō: A Tale of Two Gods in Egypt

In: Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions Author: Tawny Holm Online Publication Date:

24 Aug 2023

- Holm, Tawny (2023-08-24). "Bethel and Yahō: A Tale of Two Gods in Egypt". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 23 (1). Brill: 25–55. doi:10.1163/15692124-12341335. ISSN 1569-2116.

- Abstract[205]

Aramaic documents from Egypt suggest that Yahwists there may have identified Yahweh/Yahō with the Syrian-Aramean deity Bethel (Bayt-ʔēl). Portions of Papyrus Amherst 63, the long and complex multi-composition Aramaic text written using Demotic script, also support this view. For instance, Bethel and Yahō seem to be paralleled with each other in two poems on the papyrus; both deities share some attributes otherwise ascribed to Baʕal-Shamayn (i.e., Hadad), yet are superior to that deity; and a priestess of Bethel is termed a khnh, the feminine form of khn, the noun used solely for a priest of Yahō and no other deity in Egypt. Other subtle connections between Bethel and Yahō can also be found.

- child sacrifice / beloved son [172]

- Levenson, Jon D. (1993-01-01). The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06511-6.

- [173]

- [206]

- [207]

- Wolfson, Elliot (2013-04-18). "The Face of Jacob in the Moon: Mystical Transformations of an Aggadic Myth". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- release the krater. nice piece

- [208]

- Locatell, Christian; McKinny, Chris; Shai, Itzhaq (2022-09-30). "Tree of Life Motif, Late Bronze Canaanite Cult, and a Recently Discovered Krater from Tel Burna". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 142 (3). doi:10.7817/jaos.142.3.2022.ar024. ISSN 2169-2289.

- [209]

- Danielson on ... Qos

- [210]

- Danielson, Andrew J. (2021-04-16). "On the History and Evolution of Qws: The Portrait of a First Millennium BCE Deity Explored through Community Identity". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 20 (2): 113–189. doi:10.1163/15692124-12341314. ISSN 1569-2116.

- high importance phoe spelling https://www.jstor.org/stable/20699919

- why edom ? https://www.jstor.org/stable/20503993

- not used yet: exciting paper about jacob / jacob el

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/26566693

- place name in Egy records

- [212]

- Knohl, Israel (2017). "Jacob-el in the Land of Esau and the Roots of Biblical Religion". Vetus Testamentum. 67 (3). Brill: 481–484. ISSN 15685330 00424935, 15685330. JSTOR 26566693. Retrieved 2023-12-27.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help)

- Krause on KAjrud 4.3 allegeg exodsu

- fun, critique-al

- "not so fast"

- Krause, Joachim J. (2017). "Kuntillet ʿAjrud Inscription 4.3: A Note on the Alleged Exodus Tradition". Vetus Testamentum. 67 (3). Brill: 485–490. ISSN 15685330 00424935, 15685330. JSTOR 26566694. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help)

- Kletter, Raz (1998). Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (310). American Schools of Oriental Research: 85–89. ISSN 21618062 0003097X, 21618062. JSTOR 1357582 http://www.jstor.org/stable/1357582. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Plodding uncertain and fumbling but thorough. grammatical comments about terminal h and suffixes on DN

https://www.religionofancientpalestine.com/?page_id=230[218]

- "A New Analysis of YHWH's asherah". Religion and Literature of Ancient Palestine. 2015-12-13. Retrieved 2023-12-24.

Meshel

edit- Meshel, Ze'ev; Meyers, Carol (1976). "The Name of God in the Wilderness of Zin". The Biblical Archaeologist. 39 (1). The American Schools of Oriental Research: 6–10. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3209411. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

Meshel 95, "Dating." is anything related?[222] [223]

- Meshel, Zeev; Carmi, Israel; Segal, Dror (2006-06-12). "(PDF) 14C Dating of an Israelite Biblical Site at Kuntillet Ajrud (Horvat Teman)". Radiocarbon. 37 (2). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.2458/azu_js_rc.37.1665. ISSN 0033-8222. Retrieved 2023-12-23.

continued, normal

editfeminist, stimulating, different, but too lawyerly or midrashically creative

- "What keeps Moses from reacting? Why is circumcision necessary? Why does Zipporah perform the circumcision? Whose feet are touched with the foreskin? What is the meaning of Zipporah's incantation? Who is the "bridegroom of blood?" Why does Yahweh withdraw?"

- Pardes, Ilana (1992). Countertraditions in the Bible. Cambridge, Massachusetss London, England: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-17545-X.

polysemy and ambiguity cretan-canaanite collaboration / imigration cite high personal importance https://www.academia.edu/26405597/Metaphysis_The_Ambiguity_of_the_Minoan_Mind [226]

- Manolakakis, Stellios (2016-06-22). "Metaphysis The Ambiguity of the Minoan Mind". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2023-12-22.