GRID2

Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, delta 2, also known as GluD2, GluRδ2, or δ2, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the GRID2 gene.[5][6] This protein together with GluD1 belongs to the delta receptor subtype of ionotropic glutamate receptors. They possess 14–24% sequence homology with AMPA, kainate, and NMDA subunits, but, despite their name, have been found not to directly promote neuronal activation in response to glutamate or various other glutamate agonists.[7]

delta iGluRs have long been considered orphan receptors as their endogenous ligand was unknown. They are now believed to bind glycine and D-serine but these do not result in channel opening.[8][9]

Function

GluD2-containing receptors are selectively/predominantly expressed in Purkinje cells in the cerebellum[7][10] where they play a key role in synaptogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and motor coordination.[11]

GluD2 induces synaptogenesis through interaction of its N-terminal domain with Cbln1, which in turn interacts with presynaptic neurexins, forming a bridge across cerebellar synapses.[11][12]

The main functions of GluD2 in synaptic plasticity are carried out by its intracellular C-terminus.[13] This is regulated by D-serine,[14] which binds to the ligand-binding domain and results in changes in the structure of GluD2 without opening the channel in the absence of pre-synaptic connections.[9] Glycine and D-serine can open the channel in GluD2 when bound to cerebellin-1 and neurexin-1β.[15] These changes may signal up to the N-terminal domain or down to the C-terminal domain to alter protein-protein interactions.

Pathology

A heterozygous deletion in GRID2 in humans causes a complicated spastic paraplegia with ataxia, frontotemporal dementia, and lower motor neuron involvement[16] whereas a homozygous biallelic deletion leads to a syndrome of cerebellar ataxia with marked developmental delay, pyramidal tract involvement[17] and tonic upgaze,[18] that can be classified as an ataxia with oculomotor apraxia (AOA) and has been named spinocerebellar ataxia, autosomal recessive type 18 (SCAR18).

A gain of channel function, resulting from a point mutation in mouse GRID2, is associated with the phenotype named 'lurcher', which in the heterozygous state leads to ataxia and motor coordination deficits resulting from selective, cell-autonomous apoptosis of cerebellar Purkinje cells during postnatal development.[19][20] Mice homozygous for this mutation die shortly after birth from massive loss of mid- and hindbrain neurons during late embryogenesis.

Ligands

9-Aminoacridine, 9-tetrahydroaminoacridine, N1-dansyl-spermine, N1-dansyl-spermidine, and pentamidine have been shown to act as antagonists of δ2-containing receptors.[21]

Interactions

GRID2 has been shown to interact with GOPC,[22] GRIK2,[23] PTPN4[24] and GRIA1.[23] A possible correlation between GRID2 and the pre-B lymphocyte protein 3 (VPREB3) has been suggested, due to the apparent importance of B-lymphocytes in the origins of cerebellar Purkinje neurons in humans.[25][26][27][28][29] Morphological studies conducted in GRID2-knockout mice suggest that GRID2 may be present in lymphocytes as well as in the adrenal cortex, however further studies must be conducted to confirm these claims.[28][30]

See also

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000152208 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000071424 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: GRID2 glutamate receptor, ionotropic, delta 2".

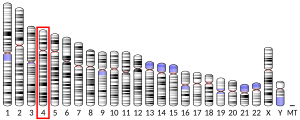

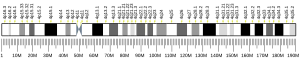

- ^ Hu W, Zuo J, De Jager PL, Heintz N (Jan 1998). "The human glutamate receptor delta 2 gene (GRID2) maps to chromosome 4q22". Genomics. 47 (1): 143–5. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.5108. PMID 9465309.

- ^ a b Lomeli H, Sprengel R, Laurie DJ, Köhr G, Herb A, Seeburg PH, Wisden W (Jan 1993). "The rat delta-1 and delta-2 subunits extend the excitatory amino acid receptor family". FEBS Letters. 315 (3): 318–22. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(93)81186-4. PMID 8422924. S2CID 43024586.

- ^ Naur P, Hansen KB, Kristensen AS, Dravid SM, Pickering DS, Olsen L, Vestergaard B, Egebjerg J, Gajhede M, Traynelis SF, Kastrup JS (August 2007). "Ionotropic glutamate-like receptor delta2 binds D-serine and glycine". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104 (35): 14116–14121. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10414116N. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703718104. PMC 1955790. PMID 17715062.

- ^ a b Hansen KB, Naur P, Kurtkaya NL, Kristensen AS, Gajhede M, Kastrup JS, Traynelis SF (Jan 2009). "Modulation of the dimer interface at ionotropic glutamate-like receptor delta2 by D-serine and extracellular calcium". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (4): 907–17. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4081-08.2009. PMC 2806602. PMID 19176800.

- ^ Araki K, Meguro H, Kushiya E, Takayama C, Inoue Y, Mishina M (Dec 1993). "Selective expression of the glutamate receptor channel delta 2 subunit in cerebellar Purkinje cells". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 197 (3): 1267–76. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1993.2614. PMID 7506541.

- ^ a b Yuzaki M (Nov 2013). "Cerebellar LTD vs. motor learning-lessons learned from studying GluD2". Neural Networks. 47: 36–41. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2012.07.001. PMID 22840919.

- ^ Matsuda K, Yuzaki M (Mar 2012). "Cbln1 and the δ2 glutamate receptor--an orphan ligand and an orphan receptor find their partners". Cerebellum. 11 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1007/s12311-010-0186-5. PMID 20535596. S2CID 16612844.

- ^ Kakegawa W, Miyazaki T, Emi K, Matsuda K, Kohda K, Motohashi J, Mishina M, Kawahara S, Watanabe M, Yuzaki M (February 2008). "Differential regulation of synaptic plasticity and cerebellar motor learning by the C-terminal PDZ-binding motif of GluRdelta2". J. Neurosci. 28 (6): 1460–1468. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2553-07.2008. PMC 6671576. PMID 18256267.

- ^ Kakegawa W, Miyoshi Y, Hamase K, Matsuda S, Matsuda K, Kohda K, Emi K, Motohashi J, Konno R, Zaitsu K, Yuzaki M (May 2011). "D-serine regulates cerebellar LTD and motor coordination through the δ2 glutamate receptor". Nat. Neurosci. 14 (5): 603–611. doi:10.1038/nn.2791. PMID 21460832. S2CID 17507539.

- ^ Carrillo, Elisa; Gonzalez, Cuauhtemoc U.; Berka, Vladimir; Jayaraman, Vasanthi (2021-12-24). "Delta glutamate receptors are functional glycine- and ᴅ-serine–gated cation channels in situ". Science Advances. 7 (52): eabk2200. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.2200C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abk2200. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 8694607. PMID 34936451.

- ^ Maier A, Klopocki E, Horn D, Tzschach A, Holm T, Meyer R, Meyer T (Feb 2014). "De novo partial deletion in GRID2 presenting with complicated spastic paraplegia". Muscle & Nerve. 49 (2): 289–92. doi:10.1002/mus.24096. PMID 24122788. S2CID 26359325.

- ^ Utine GE, Haliloğlu G, Salanci B, Çetinkaya A, Kiper PÖ, Alanay Y, Aktas D, Boduroğlu K, Alikaşifoğlu M (Jul 2013). "A homozygous deletion in GRID2 causes a human phenotype with cerebellar ataxia and atrophy". Journal of Child Neurology. 28 (7): 926–32. doi:10.1177/0883073813484967. PMID 23611888. S2CID 206550612.

- ^ Hills LB, Masri A, Konno K, Kakegawa W, Lam AT, Lim-Melia E, Chandy N, Hill RS, Partlow JN, Al-Saffar M, Nasir R, Stoler JM, Barkovich AJ, Watanabe M, Yuzaki M, Mochida GH (Oct 2013). "Deletions in GRID2 lead to a recessive syndrome of cerebellar ataxia and tonic upgaze in humans". Neurology. 81 (16): 1378–86. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a841a3. PMC 3806907. PMID 24078737.

- ^ Lalonde R, Botez MI, Joyal CC, Caumartin M (Mar 1992). "Motor abnormalities in lurcher mutant mice". Physiology & Behavior. 51 (3): 523–5. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(92)90174-Z. PMID 1523229. S2CID 33424240.

- ^ Zuo J, De Jager PL, Takahashi KA, Jiang W, Linden DJ, Heintz N (Aug 1997). "Neurodegeneration in Lurcher mice caused by mutation in delta2 glutamate receptor gene". Nature. 388 (6644): 769–73. Bibcode:1997Natur.388..769Z. doi:10.1038/42009. PMID 9285588. S2CID 4431774.

- ^ Williams K, Dattilo M, Sabado TN, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K (May 2003). "Pharmacology of delta2 glutamate receptors: effects of pentamidine and protons". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 305 (2): 740–8. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.045799. PMID 12606689. S2CID 83540259.

- ^ Yue Z, Horton A, Bravin M, DeJager PL, Selimi F, Heintz N (Aug 2002). "A novel protein complex linking the delta 2 glutamate receptor and autophagy: implications for neurodegeneration in lurcher mice". Neuron. 35 (5): 921–33. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00861-9. PMID 12372286. S2CID 10534933.

- ^ a b Kohda K, Kamiya Y, Matsuda S, Kato K, Umemori H, Yuzaki M (Jan 2003). "Heteromer formation of delta2 glutamate receptors with AMPA or kainate receptors". Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 110 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1016/S0169-328X(02)00561-2. PMID 12573530.

- ^ Hironaka K, Umemori H, Tezuka T, Mishina M, Yamamoto T (May 2000). "The protein-tyrosine phosphatase PTPMEG interacts with glutamate receptor delta 2 and epsilon subunits". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (21): 16167–73. doi:10.1074/jbc.M909302199. PMID 10748123.

- ^ Hess DC, Hill WD, Carroll JE, Borlongan CV (Apr 2004). "Do bone marrow cells generate neurons?". Archives of Neurology. 61 (4): 483–5. doi:10.1001/archneur.61.4.483. PMID 15096394.

- ^ Weimann JM, Johansson CB, Trejo A, Blau HM (Nov 2003). "Stable reprogrammed heterokaryons form spontaneously in Purkinje neurons after bone marrow transplant". Nature Cell Biology. 5 (11): 959–66. doi:10.1038/ncb1053. PMID 14562057. S2CID 33685652.

- ^ Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Fike JR, Lee HO, Pfeffer K, Lois C, Morrison SJ, Alvarez-Buylla A (Oct 2003). "Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes". Nature. 425 (6961): 968–73. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..968A. doi:10.1038/nature02069. hdl:2027.42/62789. PMID 14555960. S2CID 4394453.

- ^ a b Felizola SJ, Katsu K, Ise K, Nakamura Y, Arai Y, Satoh F, Sasano H (May 2015). "Pre-B Lymphocyte Protein 3 (VPREB3) Expression in the Adrenal Cortex: Precedent for non-Immunological Roles in Normal and Neoplastic Human Tissues". Endocrine Pathology. 26 (2): 119–28. doi:10.1007/s12022-015-9366-7. PMID 25861052. S2CID 27271366.

- ^ Kemp K, Wilkins A, Scolding N (Nov 2014). "Cell fusion in the brain: two cells forward, one cell back". Acta Neuropathologica. 128 (5): 629–38. doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1303-1. PMC 4201757. PMID 24899142.

- ^ Berenova M, Mandakova P, Sima P, Slipka J, Vozeh F, Kocova J, Cervinkova M, Sykora J (2002). "Morphology of Adrenal Gland and Lymph Organs is Impaired in Neurodeficient Lurcher Mutant Mice". Acta Vet. Brno. 71: 23–28. doi:10.2754/avb200271010023.

Further reading

- Araki K, Meguro H, Kushiya E, Takayama C, Inoue Y, Mishina M (Dec 1993). "Selective expression of the glutamate receptor channel delta 2 subunit in cerebellar Purkinje cells". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 197 (3): 1267–76. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1993.2614. PMID 7506541.

- Hu W, Zuo J, De Jager PL, Heintz N (Jan 1998). "The human glutamate receptor delta 2 gene (GRID2) maps to chromosome 4q22". Genomics. 47 (1): 143–5. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.5108. PMID 9465309.

- Sanger Centre, The; Washington University Genome Sequencing Cente, The (Nov 1998). "Toward a complete human genome sequence". Genome Research. 8 (11): 1097–108. doi:10.1101/gr.8.11.1097. PMID 9847074.

- Roche KW, Ly CD, Petralia RS, Wang YX, McGee AW, Bredt DS, Wenthold RJ (May 1999). "Postsynaptic density-93 interacts with the delta2 glutamate receptor subunit at parallel fiber synapses". The Journal of Neuroscience. 19 (10): 3926–34. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03926.1999. PMC 6782719. PMID 10234023.

- Hironaka K, Umemori H, Tezuka T, Mishina M, Yamamoto T (May 2000). "The protein-tyrosine phosphatase PTPMEG interacts with glutamate receptor delta 2 and epsilon subunits". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (21): 16167–73. doi:10.1074/jbc.M909302199. PMID 10748123.

- Miyagi Y, Yamashita T, Fukaya M, Sonoda T, Okuno T, Yamada K, Watanabe M, Nagashima Y, Aoki I, Okuda K, Mishina M, Kawamoto S (Feb 2002). "Delphilin: a novel PDZ and formin homology domain-containing protein that synaptically colocalizes and interacts with glutamate receptor delta 2 subunit". The Journal of Neuroscience. 22 (3): 803–14. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00803.2002. PMC 6758529. PMID 11826110.

- Ly CD, Roche KW, Lee HK, Wenthold RJ (Feb 2002). "Identification of rat EMAP, a delta-glutamate receptor binding protein". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 291 (1): 85–90. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2002.6413. PMID 11829466.

- Yue Z, Horton A, Bravin M, DeJager PL, Selimi F, Heintz N (Aug 2002). "A novel protein complex linking the delta 2 glutamate receptor and autophagy: implications for neurodegeneration in lurcher mice". Neuron. 35 (5): 921–33. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00861-9. PMID 12372286. S2CID 10534933.

- Kohda K, Kamiya Y, Matsuda S, Kato K, Umemori H, Yuzaki M (Jan 2003). "Heteromer formation of delta2 glutamate receptors with AMPA or kainate receptors". Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 110 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1016/S0169-328X(02)00561-2. PMID 12573530.

- Yap CC, Muto Y, Kishida H, Hashikawa T, Yano R (Feb 2003). "PKC regulates the delta2 glutamate receptor interaction with S-SCAM/MAGI-2 protein". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 301 (4): 1122–8. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00070-6. PMID 12589829.

- Sonoda T, Mochizuki C, Yamashita T, Watanabe-Kaneko K, Miyagi Y, Shigeri Y, Yazama F, Okuda K, Kawamoto S (Nov 2006). "Binding of glutamate receptor delta2 to its scaffold protein, Delphilin, is regulated by PKA". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 350 (3): 748–52. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.109. PMID 17027646.