West End, Edinburgh

| West End | |

|---|---|

Melville Street looking down towards West Register House | |

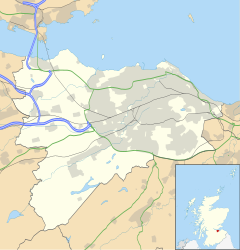

Location within the City of Edinburgh council area Location within Scotland | |

| Council area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Postcode district | EH2, EH3 |

| Dialling code | 0131 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

The West End is an affluent district of Edinburgh, Scotland, which along with the rest of the New Town and Old Town forms central Edinburgh, and Edinburgh's UNESCO World Heritage Site.[1] The area boasts several of the city's hotels, restaurants, independent shops, offices and arts venues, including the Edinburgh Filmhouse, Edinburgh International Conference Centre and the Caledonian Hotel.[2] The area also hosts art festivals and crafts fairs.[3][4][5]

Built as a western expansion of the New Town, the northern part of the West End sits on the Water of Leith river and forms part of Edinburgh's UNESCO World Heritage Site.[6] The West End is contiguous with the rest of New Town and is accordingly included in the New Town Conservation Area.[7] As can be inferred therefore, this area of the city contains many buildings of great architectural beauty, primarily long rows and crescents of Georgian terraced houses.[8] The West End also incorporates many of the New Town Gardens, a heritage designation since 2001.[9]

The district is one of Edinburgh's most affluent areas, and includes many of the most expensive streets in Scotland's capital.[10] Many nations have their consulates in the West End. The Scottish Episcopal Church has its headquarters, Forbes House, in the district and the official residence of the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is also located here.[11]

The West End district is immediately west of the rest of the New Town, and also the Old Town. It is bordered to the north by the Stockbridge, Dean Village, and Ravelston districts, Tollcross and Fountainbridge districts to the south, and West Coates, Haymarket and Murrayfield to the West.

History

[edit]

In 1615 John Byres the city Treasurer built Easter Coates House to the west of the city. The house had a truly huge estate, stretching to St Cuthbert's Church.[12] The house was originally a Laird's house, and as the city of Edinburgh grew, and John Byres became city Treasurer and Bailie, it became an early example of a Burgher's city mansion. The house is still standing as of the 21st century as the centre of the West End district.[13]

Founding of the West End (Western New Town)

[edit]For the history and development of the rest of New Town see: New Town, Edinburgh.

In 1806, Shandwick Place was developed as a western extension of New Town's Princes Street, to the south of the Easter Coates House estate, by John Cockburn Ross, of Shandwick in Easter Ross, who commissioned architect James Tait to come up with a plan for the west of New Town. It was eventually joined up with the newly built Maitland Street (started 1807), named after its developer and owner Sir Alexander Charles Maitland, 2nd baronet of Cliftonshall.[14][15]

Around 1800, the Easter Coates House estate was bought by William Walker, an Advocate and the Gentleman Usher of the White Rod in the Estates of Parliament, who sought to develop the east section of the estate, as a western extension of the then newly built New Town.[16][17][18] In 1808 a plan for the West End Village was devised by the architect Robert Brown.[18] Property in the West of the city was desirable to the wealthy early on because the winds carried smog, dust and pollution eastward.[19]

Under the Brown plan Melville Street would form the centrepiece of the new Georgian West End Village, extending directly from the western facing side of West Register House and Randolph Place. The street would be accessed to the south at Shandwick Place, from Coates Crescent by Walker Street, which would itself be intersected by William Street to create a Georgian grid layout, with both roads named after William Walker. Construction began in 1813 on Coates Crescent. Brown also developed Atholl Crescent which faces Coates Crescent.[20] Melville Street was largely completed by the 1830s although the corner plots would remain unfinished until the 1860s.[18][21] At the centre of Melville Street is a bronze statue of Robert Dundas, 2nd Viscount Melville standing on two large stone steps.[22][23]

The William Walker estate abutted the estate of James Erskine, Lord Alva and the Erskine Trustees, with Stafford Street forming the junction between the two estates. The Erskine family estate was developed alongside the Walker estate, but using James Gillespie Graham as the architect, instead of Brown. Gillespie Graham was the architect for the Earl of Moray and had designed the Moray Feu in the New Town, and was employed by Lord Alva to continue the New Town westward. Alva Street (named for Lord Alva), which serves as a continuation of William Street and the Georgian grid, was constructed in 1830 and is a rare and fine example of Gillespie Graham's Georgian work.[24][25]

Stafford Street itself was a joint development between the Erskine and Walker Estates. This has led to some confusion over who was responsible for the design, Robert Brown (Walker's architect) or Gillespie Graham (Erskine's architect). Experts believe it was Brown, as the architecture is simpler, while Gillespie Graham was known for his grand, and often more expensive, works.[26]

Gillespie Graham was also tasked with designing Queensferry Street, part of the Erskine Estate, which acts as the junction between the New Town and the new West End development. The north of Queensferry Street is where the West End meets the Moray Feu. Here Queensferry Street overlooks Randolph Crescent Garden, one of the New Town Gardens, and formerly the location of the estate of the Earl of Moray. Randolph Crescent Garden was not part of the Moray Feu Estate gardens, and the land was not feued, as the Earl of Moray had hoped to extend the Moray Feu into the West End here and build a new city mansion for himself. As such, in 1825 several houses around this area of the Moray Estate had been purchased by the Heriot Trust on the advice of Gillespie Graham. The intention was to knock some of the houses down in order to extend the garden and roads to create a grand entrance from the Moray Estate into the West End development. By 1829, however, it was agreed that the prospect of the feuars agreeing to demolition or deviation from the original Moray Feu plan was so remote that it was not worth pursuing the plan, and the houses were sold at a considerable loss. By 1867 Lord Moray had sold the Randolph Crescent garden to the Feuers at Randolph Crescent, however it remains managed separately from the other Moray Estate gardens.[27][28][29]

Randolph Place provides access from Melville Street into Charlotte Square and from there on to George Street in the New Town via two unassuming passages either side of the West Register House, constructed between 1811 and 1814. Robert Adam's original plan for the building included a grand rear entrance onto Randolph Place. However, when the funds could not be found for Adam's design, architect Robert Reid was called in to modify the plan. The modified plan placed attenuated pavilions flanking a Diocletian window above a Venetian window at the rear of the building overlooking Randolph Place, and although architect David Bryce later drew up plans to add towers to the pavilions, this work was never carried out. Randolph Place therefore became a comparatively unimpressive entrance from the West End's Melville Street, into Charlotte Square.[30][31]

At the north of Queensferry Road is Lynedoch Place, built on land owned by Major James Weir and broadly completed by 1823 by architect James Milne. The Georgian terraces here are stepped into the slope, and command views over the Deane. This is also the location of the Drumsheugh Baths Club.[28] From here the road also splinters onto the Dean Bridge constructed much later by Thomas Telford, and capped on the south side by what is now Deanbrae House (formerly an inn), and to the north by the Holy Trinity Church built in the late 1830s.[32]

This Georgian era central part of the West End is sometimes also known as "Western New Town" or the "West End Village".[33][34]

The southern area of the new West End was developed separately under several different landowners.[18] Rutland Square had been developed from the 1830s under the auspices of its owner Provost John Learmonth who also owned much of the nearby Dean Village.[14]

The Victorian Extension

[edit]

The area west of Manor Place remained undeveloped until the 1860s.[14] One of the few exceptions was in 1850, when Sheriff of the Lothians and Peebles George Napier bought some of the land on the west of the estate for construction of a new "Coates Hall", designed by David Bryce as a small Baronial house.[35] Other than this, William Walker left the land north and south of his Easter Coates House home as garden ground and it remained such until the 1870s.[18]

The estate was inherited by William's son, Sir Patrick Walker, who also inherited his father's office of White Rod of the Scottish Parliament (an ancient office similar to Black Rod in England). Sir Patrick expanded the Easter Coates House, often incorporating historic carved stones he had collected from demolished historic buildings in the Old Town. As well as a number of inscriptions there is a round-arched doorway and an elaborate double window with a pediment above, which is said to have come from the French Ambassador's Chapel in the Cowgate.[16]

After his death the Easter Coates House estate would be inherited by Sir Patrick's two spinster daughters: Mary and Barbara Walker. Devout Episcopalians, they donated the garden of Easter Coates House, and fully underwrote the entire cost of building an Episcopalian Cathedral as a centrepiece for the whole West End at the end of Melville Street. There had not been an Anglican/Episcopal Cathedral in Edinburgh since the Anglican Scottish Episcopal Church was disestablished as the Church of State in 1690, when the Bishop of Edinburgh and congregation were removed from St Giles' Cathedral, which was handed over to the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.[36]

Work began on the cathedral in 1873 under the supervision of The Walker Trust and opened in 1879. It was named St Mary's Episcopal Cathedral. The Walker's funds did not cover the cost of all three spires. The two front spires were not added until 1917.[37] The Walker Trustees also received the office of White Rod, to be granted to the serving Bishop of Edinburgh, who holds the office ex-officio to this day.[38] In 2011 the Walker Trustees found the regalia of the White Rod in a safety deposit box in the Royal Bank of Scotland Headquarters and donated it for exhibition to the National Museum of Scotland.

The St Mary's Music School was opened in 1880 in the West End as the Song School of St Mary's Episcopal Cathedral in 1880 to educate choristers for the cathedral. Napier's New Coates Hall meanwhile was purchased and turned into Edinburgh Theological College - the music school would move to this building in 1994.

Buildings constructed after the latter half of the 19th century are generally regarded as 'the Victorian Extension' of the West End. This includes Drumsheugh Gardens. Designed by John Lessels, they were built around a private garden in the late 1870s, the square was named for the gardens of Drumsehugh House, the estate of the Earls of Moray which once stood on Randolph Crescent in the Moray Feu and stretched into this area of the West End.[39][40][41]

Additional Victorian crescents and terraces were built around this northern section of the West End as the Walker family sold off the land to the west of Easter Coates House in the 1860s, usually with a private garden as their central focal point in much the same way as the New Town Gardens. These included the 1860s Rothesay Terrace by Peddie and Kinnear, and the 1870s Eglinton, Glencairn, Grosvenor and Lansdowne Crescents by John Chesser.[42]

Palmerston Place forms a junction between the older Georgian West End and the newer Victorian Extension. It extends into Douglas Gardens, developed in the 1890s and bounding the Waters of Leith.[43]

In 1881 a grand 56 metre campanile was added to St George's West Church at Shandwick Place, described as "one of the icons of Scottish presbyterianism". The original church had been designed by David Bryce, however the stunning campanile was the work of Sir Robert Rowand Anderson, one of Scotland's most renowned architects of the era. Anderson modelled the campanile after the one on the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice designed by Andrea Palladio in 1467.[44][45]

The North West End

[edit]

One part of the Victorian extension curves around north up the Queensferry Road, over the Dean Bridge, and overlooking the Dean Village and Dean Gardens.

Lord Provost of Edinburgh John Learmonth built the Dean Bridge around 1838 with engineer Thomas Telford to open up his lands in the north of the West End. With architect John Tait, Learmonth developed Clarendon Crescent, named after the Earl of Clarendon and based on William Henry Playfair's Regent Terrace. The crescent disguised this side of the Dean Bridge by raising ground levels to create a level platform for building.[46][47]

Following the success of Clarendon Crescent, further plans were drawn up for the flanking streets, which were to be called Oxford Terrace and Cambridge Terrace, after Britain's then leading universities. This development became slowed due to a dispute concerned with the steep slope next to the Dean Bridge where Cambridge Terrace would be built. At the time the steep slope was then used for sheep grazing and in places, had become disfigured with piles of building spoil. A number of nearby residents began a public subscription to purchase the slope, to improve the land and prevent the construction of Cambridge Terrace. As the dispute dragged out the name Cambridge was usurped by a development south of Edinburgh Castle and the eastern terrace was instead called Eton Terrace after Eton College. The slope would be landscaped, and become known as The Eton Terrace Garden (later renamed the Dean Gardens).[48][49][47]

Due to delays and the bankruptcy of the Learmonth family the development of the rest of this land was much delayed. Following the bankruptcy of the Learmonth family, the land was purchased by Sir James Steel, a Lord Provost of Edinburgh who made his fortune in the building trade. The plan for this area had been drawn up by architect John Chesser. The plan called for rows of well proportioned townhouses in much the same way as Tait had done with Clarendon Crescent, creating a corresponding crescent opposite called Buckingham Terrace, however Chesser oversaw only the construction of Learmonth Terrace as Steel preferred to use his own architect.[50][51]

At the far end of Learmonth Terrace is Learmonth House, designed by architect James Simpson. It was designed in 1891 for Arthur Sanderson, the famous whisky distiller. In 1925 it was purchased to be the Headquarters of 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron, Royal Auxiliary Air Force.[52][50]

The South West End

[edit]The South West End - south of Shandwick Place, and across from Kings Stable Road to what is now Morrison Street - was once known as the Kings Garden due to its position against Edinburgh Castle. By the 1400s it was known as Orchard Field. A significant part of this land was purchased towards the end of the 18th century; half by the Grindlay brothers, tanners on King's Stable Road, and the remaining half by the Merchant Company. A patchwork of estates soon developed between Castle Rock and the Haymarket which would form the south of the West End.[53]

Most of the South West End was developed later than the West End Village in the north. Through the early 1800s, proposed canal and railway developments, plus the uncertainty about the New Western Approach road to the Old Town, made the South West End less desirable, and delayed the implementation of a number of development proposals to extend the New Town and West End Georgian terraces southward to Tollcross. By the 1820s only two such schemes had begun, one on Morrison Street and the other known as Gardener's Crescent. The matching crescent opposite was never constructed because of the railway.[53]

A neoclassical church was built in 1831, designed by architect David Bryce for the United Presbyterian Church, later becoming St Thomas of the Church of Scotland, which counted Andrew Thomson amongst its ministers.

The Edinburgh Princes Street railway station was built in the West End in the 1890s, and features a large, grand, railway hotel. The station was closed in 1965 but the hotel remains.

Edinburgh's first power station was built on the southern edge of the West End at Dewar Place off Morrison Street between 1894 and 1895.[54][55] The power station was coal-fired using fuel from the adjacent Caledonian Railway yards adjacent to Edinburgh Princes Street railway station.[54] While the power station has since been dismantled, the area still serves as one of the main electricity substations in Edinburgh and the site is covered with a false frontage.[55]

By the late 19th and early 20th century the South West End began to obtain a reputation for the arts. Stradling the South West End, Tolcross and the Old Town, the Royal Lyceum Theatre was constructed in 1883.[53] The Usher Hall, a concert venue, would open in 1914 also straddling the Old Town, Tolcross and West End.[56] The Caley Picture House meanwhile opened in 1923, and though it closed in 1984, now being occupied by a Wetherspoons pub of the same name, the West End maintained a connection to cinema with the opening of the Edinburgh Filmhouse in 1979 in Bryce's old church.

Access to the South West End from Shandwick Place is via the Lothian Road, which was built to give easy access from the west end and Princes Street to as far down as Fountainbridge and The Meadows.[57]

Shandwick Place originally comprised a terrace of 19th-century palace-fronted tenements by James Tait. By the late 19th century however Shandwick Place was redeveloped by a number of private developments, around the same time as the construction of the railway and Caledonia Hotel, which has left the small street with a distinct architectural feel compared to the surrounding Georgian era buildings. Architect John McLachlan developed numbers 52, 54 and 56 as some of his first works as a sole practitioner.[58] Following this re-development, Shandwick Place was famed for its art galleries, and connection to the turn of the century Scottish Colourists who worked in the area.[59] By the early 20th Century, Shandwick Place was a bustling high end shopping street, which also featured the flagship car showroom for the Rossleigh Car Company. Rossleigh held a royal warrant as Motor Engineers to the King, and sold Daimler, Rolls-Royce, Bentley, and many other high end motor vehicles.[60][61][62]

Recent history

[edit]Although initially built as a residential district, from the mid 20th century many of the buildings in the West End were predominantly used for offices. Retail uses are concentrated on Shandwick Place, West Maitland Street, William Street and Queensferry Street where the area abuts the Moray Estate. William Street is the only street which has a continual commercial ground floor of 19th-century character.

The West End of Edinburgh has been synonymous with the arts since the late 19th century. In 1876, the Albert Gallery was built on Shandwick Place, styled as the Albert Institute of the Fine Arts. The institute was intended to promote the encouragement of fine art in general, and contemporary Scottish art in particular. Today it is used as offices.[63]

In 1984 the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art opened at its present site, Modern One on Belford Road to the west of the West End Village. In March 1999, the National Galleries of Scotland opened Modern Two across the road from Modern One as a sister gallery.[64]

In 1998, the Church of Scotland purchased a two-story townhouse, Number 2 Rothesay Terrace, in the West End for use as an official residence for the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.[65][66]

From 1999 until 2020, the address at 1 Melville Crescent served as the Edinburgh home of the Secretary of State for Scotland, until the office was moved to the Queen Elizabeth House building in the Old Town.[67]

Prior to the UK's Brexit vote the European Commission had their European Commission Representation in Scotland at 9 Alva Street in the West End.[68] The office was closed and the flag taken down in 2019.[69]

Around 2019, the City of Edinburgh Council began to hold public consultations on improving the Randolph Place entrance onto Melville Street into the West End Village from Charlotte Square, via the passages either side of West Register House. Suggestions included removing parking, resurfacing the setts, or the addition of green space and public art, and the possibility of a cycle route.[70][71]

In the South West End, a complex of buildings was opened in the mid-1980s on the site that formerly housed the Princes Street Station goods shed. Called The Exchange, it was designed by Sir Terry Farrell and includes the Edinburgh International Conference Centre, a Sheraton Grand hotel, a cutting edge Spa facility, bars and restaurants, and a number of offices for financial firms, lawyers, and banks.[72][73]

By 1984, the space opposite the Usher Hall in the West End (formerly the site of the goods shed for the Princes Street Railway Station) would be laid out as a new piazza-style square. The square was intended to connect the space around the Usher Hall with the space created by The Exchange development and adjoining buildings to create a large public space for the city's festivals and fringe. The success of the square has been mixed, with many critics claiming the busy Lothian Road makes the two spaces feel very separate. To counteract this criticism in 2019 plans were drawn up to part or fully pedestrianize the road by the square, and redirect traffic around this part of the Lothian Road.[53][74][56] In 2021, due to the growth of the Edinburgh Film Festival, plans were submitted to build a contemporary tower caped in video-capable screens, with underground cinema space and rooftop terraces, in Festival Square to be operated by the Edinburgh Film Festival organisers.[75][76]

Access to the South West End, from Atholl Crescent and the West End tram stop, is via Canning Street. It appears the original intention for Canning Street was to extend the surrounding Georgian terraced properties. Number 2 Canning Street appears to have been built as a Georgian tenement. The plan seems to have been abandoned due to uncertainty around prospective rail, road and canal developments. Number 2 Canning Street was later converted to a whisky bonded warehouse (it is as of 2022 a block of high end apartments). The gaps this left were filled in during the Victorian era, and later 1960s/70s with different priorities in mind. In recent years this has led to the assessment that these buildings - predominantly infrastructure and office space - are unsympathetic in terms of style, scale and massing with the rest of the area. These buildings, while overlooking the streets at ground floor level, do not provide activity and hence the streets have a feeling of emptiness. Attempts have been made in recent years to improve this street and increase foot traffic down it. At the rear of Canning Street for example, there are electricity sub stations which through the use of lighting have been turned into “public art”.[53][77][78]

Geography

[edit]

The West End is located at the western edge of the centre of Edinburgh, to the west of the Old Town and largely contiguous with the New Town. The Dean Village is surrounded by the north of the West End to its south, east, and west, sharing only its northern boundary with Ravelston.

The West End is also bordered by the Stockbridge district to the north east, and Ravelston district is to the north west. Haymarket, Murrayfield and West Coates are directly west of the West End. Fountainbridge and Tollcross are the districts to the south.[79]

The primarily Georgian section of the West End in the north forms part of Edinburgh's World Heritage Site along with the rest of the New Town.[6][80]

The Water of Leith is the main river in Edinburgh city centre, and flows through the West End. The Belford Bridge is the main crossing into the West End from the west. The Dean Bridge, allows traffic to cross from the south of the West End into the North.

Shandwick Place, Princes Street, Queensferry Road, and the Lothian Road all coalesce on the eastern side of the West End at Rutland Place, forming an important junction in Edinburgh. The positioning of the Johnnie Walker building (formerly Frasers) and St John's Church on the New Town side, along with The Caledonian Hotel and The Rutland Hotel on the West End side, give this junction the feel of a large public square.

Governance

[edit]The West End is served by the West End Community Council.[81]

The south of the West End falls into the City Centre council ward, while the north comes under the Inverleith ward for elections to the City of Edinburgh Council.[82]

The West End falls under the Edinburgh Central Scottish Parliament constituency.

For UK Parliamentary Elections, most of the West End falls under the Edinburgh North and Leith constituency, while some of the south of the West End falls under either the Edinburgh South West or Edinburgh West constituencies.[83]

Economy

[edit]The West End is home to a large number of offices, shops, restaurants, bars and cultural venues.[2]

In recent history the West End has become associated with Bohemianism and the arts. The Edinburgh Filmhouse opened in the 1970s and is home to the Edinburgh International Film Festival, the world's oldest continually running film festival.[5] The Scottish Arts Club, which opened in 1873 has retained a home on 24 Rutland Square.[84] The West End is also home to a number of venues for the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, as well as hosting the Edinburgh Festival West End Fair, Edinburgh's largest Arts, Crafts and Design Fair.[85] The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art has both galleries in the West End - Modern One and Modern Two - to the west of the West End Village.[64]

The West End is popular with tourists, and has several hotels and hostels, including the Bonham (on Drumsheugh Gardens), the Edinburgh Grosvenor (on Grosvenor Street), the Guards Hotel, and the Haymarket Hub hotel (on Haymarket Street), and the Thistle Hotel (on Manor Place). William Street has become a popular tourist shopping destination, mainly because of the 19th-century-style shopfronts. It is known for its upmarket independent fashion boutiques comparable to London's Notting Hill. It has also become a location sought after by location scouts in the film industry.[86][87]

The food and drink sector is also prominent in the West End, with a number of restaurants across the district, and the Edinburgh tasting room of fine wine merchant Justerini & Brooks on Alva Street.[88]

The West End contains several consulates and High Commissions, including those of Germany (on Eglinton Crescent), Switzerland (on Manor Place), Turkey (on Drumsheugh Gardens), India, Norway and New Zealand (on Rutland Square), and Italy, Russia and Taiwan (on Melville Street).[89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97]

The Edinburgh International Conference Centre is located in the South West End in the Exchange District, a regenerated business district that opened in the mid-1990s. Large employers in the West End include Standard Life, whose headquarters is located on the western side of Lothian Road.[98] The Exchange Tower in the West End is central Edinburgh's tallest building.[99] This part of the West End is also home to news media outlets and film and television production companies.[100][101][102]

Culture and community

[edit]

The West End is associated with a number of arts movements, and is one of the key locations during the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The district has also been associated with the LGBTQ community, and hosts a number of highly rated LGBTQ friendly hotels.

Museums and Libraries

[edit]The Museum of the Incorporated Trades of Edinburgh - the ancient body of craftsmen of Edinburgh with a history dating back past 1424 - is at their headquarters at Ashfield House, number 61 Melville Street in the West End Village. On the ground floor there are four rooms, three of which house the museum collection of artefacts and the Convenery's Hall; the fourth room houses the library and archive.[103]

The Library of Mistakes established by group of Edinburgh financiers, "founded to promote the study of financial history" and "dedicated to learning from financial fiascos and failures" is on Melville Street Lane in the West End.[104][105]

Art galleries

[edit]The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art lies on the far north-western edge of the West End, adjacent to the Dean Village.[106] The Gallery is split across two buildings; the former John Watson's Institution known as Modern One and Modern Two in a former orphan hospital.[106] They can be accessed from the West End by foot via a footbridge on the Water of Leith walkway, or road via the Belford Bridge in the Dean Village.

There are also a number of private art galleries across the district.

Screen and stage

[edit]The Edinburgh Filmhouse is based in the West End of Edinburgh and hosts the Edinburgh Film Festival. The Usher Hall concert venue, Traverse Theatre, and Royal Lyceum Theatre are on the South West End and Old Town border in Festival Square, separated by the Lothian Road. The South West End is also home to the Edinburgh International Conference Centre.

Parks and public spaces

[edit]The West End Village contains several parks and gardens within the New Town Gardens heritage designation, but the majority are in private ownership. Private green areas include the Dean Gardens, Drumsheugh Gardens (named after the Earl of Moray's home Drumsheugh), Rothesay Terrace Gardens, Magdala Crescent Gardens, and Eglinton and Glencairn Crescents’ Gardens (opened 1877).[107][108][109] Rutland Square is a private square gardens completed in the 1830s.[110]

Atholl Crescent Gardens (sometimes known as Coates Crescent Gardens) are public gardens within the New Town Garden heritage designation laid out in a crescent form in the 1820s, divided by Shandwick Place.[111] The gardens contain a large memorial statue of William Ewart Gladstone by James Pittendrigh Macgillivray.[112] The statue was unveiled in Edinburgh in 1917 and moved to its present location in 1955.[112]

On the north West End, and Easter Coates border is the Edinburgh Life Tribute at the AIDS Memorial Park on the Water of Leith. Since World AIDS Day 2004, the 'Life Tribute' is a place has been dedicated to remember all those affected by HIV/AIDS. It's a permanent site, situated on the Water of Leith Walkway, behind the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.[113][114]

Architecture

[edit]

The Cockburn Association (Edinburgh Civic Trust) is prominent in campaigning to preserve the architectural integrity of the West End.

The West End is a large draw to tourists and visitors to Edinburgh. The Georgian architecture of the New Town and the West End together form the largest area of Georgian architecture in Europe, and it is part of what gives Edinburgh its UNESCO World Heritage Site status. It was referred to as "the Scottish Enlightenment in stone" and "the Athens of the North".[115][116] Both the medieval Easter Coates House and later gothic St Mary's Cathedral provide a contrast to the Georgian architecture. The West End has a heritage trail that includes signs exploring famous places and residents of the West End.[6]

Clubs and societies

[edit]A number of clubs and societies are based in the West End, including The Scottish Liberal Club (after their relocation from Princes Street), the Scots Guards Club, the Scottish Arts Club (founded in 1873), and the Edinburgh Chess Club.[117][118][119]

A number of sports clubs also exist in the West End, including the Drumsheugh Baths Club, and the Edinburgh Sports Club - a racket sports club opened in 1936.[120]

Medical practice

[edit]The West End Medical Practice is the local GP surgery under NHS Scotland.[121] Designed by Page\Park Architects, the practice opened in 2014 in a new purpose built complex at a cost of £4 million.[122]

Transport

[edit]

Rail

[edit]Since the closure of the Princes Street railway station, Haymarket station on the West End/Haymarket border serves as the nearest railway station for most of the area. The station opened in 1842 and was the original terminus of the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, however as the line was extended it became an intermediate station on the extension to Princes Street Railway Station and later Edinburgh Waverley.[123] An extensive refurbishment of Haymarket Station, with the addition of a new concourse and entrance was completed in 2013.[124]

Tram

[edit]The island tram stop at Coates Crescent on Shandwick Place was named West End - Princes Street prior to opening at the request of local traders.[125] As this stop sits on a switching point, it can act as an eastern terminus when Princes Street is closed to traffic. The Princes Street suffix was dropped in 2019 and the stop is now known as West End.[126]

West End

| Preceding station | Edinburgh Trams | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Princes Street towards Newhaven |

Newhaven - Edinburgh Airport | Haymarket towards Airport |

Buses

[edit]The Shandwick Place/ Maitland Street corridor is well-served by Lothian Buses and other operators with destinations out with Edinburgh.

All buses eastwards go to Princes Street, where there are easy links to the Lothian Road corridor. Westward routes split at Haymarket: either to the Gorgie/Dalry district or westwards to Roseburn, Murrayfield, and Corstorphine.

Education

[edit]

St Mary's Music School is a mixed music school in the West End, established in 1880.[127] The Song School and Walpole Hall are listed buildings, containing murals by Phoebe Anna Traquair and designed by the architects Robert Rowand Anderson and Robert Lorimer respectively.[128]

The West End has no State primary or secondary schools within its geographical area; the nearest primary schools are Dalry Primary School in Dalry and Tollcross Primary School in Tollcross, and the nearest secondary schools are Boroughmuir High School and Broughton High School. Torphichen Street School was a combined infant and juvenile school in the West End built in 1887, but it was closed in the 20th century and converted to offices.[129]

The West End is well served for private schools. Stewart's Melville College, an independent day and boarding school established in 1832 (at one time based on Melville Street) now sits on the northern border of the district with Ravelston.[citation needed] Several other private schools, such as Fettes College and St George's School lie within walking distance in neighboring districts of the West End Village.[130][131]

Religion

[edit]

St Mary's Cathedral is a late 19th-century cathedral of the Scottish Episcopal Church in the West End.[132] It is designed in the Gothic style by Sir George Gilbert Scott and is a Category A listed building.[133] Reaching 90 metres (295 ft), its spire makes the building the tallest in the Edinburgh urban area.[134]

St George's West Church, formerly of the Church of Scotland, now a Baptist chapel, is located on the corner of Shandwick Place and Stafford Street in the West End. Construction of the church began in 1867 to designs by David Bryce in the Roman Baroque style.[135][136] The 56m tower in the south-west corner was completed by 1882 under Robert Rowand Anderson, in the form of a Venetian campanile, modeled on that of San Giorgio Maggiore.[135][136]

Palmerston Place Church is an Italianate-style church designed by John Dick Peddie and Charles Kinnear, and completed in 1875.[137][138] Services are provided by the Church of Scotland.[139]

References

[edit]- ^ "Randolph Crescent Visitor Guide, Hotels, Cottages, Things to do in Scotland". scotland.org.uk.

- ^ a b "The West End, Edinburgh - Edinburgh Guide". Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Enjoy the Spirit of Christmas in Edinburgh's West End Village Street Market". Edinburghguide.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Randolph Crescent Visitor Guide, Hotels, Cottages, Things to do in Scotland". Scotland.org.uk.

- ^ a b "The Ultimate Guide to Edinburgh's West End - Forever Edinburgh". Edinburgh.org.

- ^ a b c "Meet the West Enders". Edinburgh World Heritage. 24 November 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ "New Town Conservation Area Character Appraisal". Edinburgh.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Things to do". Edinburgh-westend.co.uk.

- ^ "THE NEW TOWN GARDENS (GDL00367)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Revealed: Here are the most expensive streets in Edinburgh". Edinburghnews.scotsman.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Terms & Conditions". The Scottish Episcopal Church.

- ^ The Closes and Wynds of Edinburgh: The Old Edinburgh Club

- ^ "Easter Coates House".

- ^ a b c Fleet, Chris; MacCannell, Daniel (2018). Edinburgh: Mapping the City. Scotland: Birlinn Ltd. p. 154. ISBN 978-1780272450.

- ^ "4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Queensferry Street (Lb29577)".

- ^ a b "Dean Village News" (PDF). Deanvillage.org. 1992. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Imperial Society of Knights Bachelor". Londonremembers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Fleet, Chris; MacCannell, Daniel (2018). Edinburgh: Mapping the City. Scotland: Birlinn Ltd. p. 153. ISBN 978-1780272450.

- ^ Goldstein, Steve. "The incredible reason east sides of cities are poorer than west sides". MarketWatch.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Buildings of Scotland: Edinburgh by Gifford McWilliam and Walker

- ^ "46-60 (Even Numbers) Melville Street, 31 Manor Place, Including Railings and Arched Lamp Holders (Lb29328)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "Edinburgh statue of Robert Dundas latest to sprayed with anti-slavery graffiti". Dailyrecord.co.uk. 10 June 2020.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Edinburgh, Melville Street, 2nd Viscount Robert Melville Statue (237962)". Canmore. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "28, 30, 32 Alva Street Including Railings (Lb28240)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "Engine Shed guidance for owners and occupiers of traditional buildings". Blog.engineshed.scot. 18 December 2018.

- ^ "4-16B (Even Numbers) Stafford Street and 2, 4 William Street (Lb29830)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "MORAY FEU – Georgian Gardens Of Edinburgh". Morayfeu.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ a b "3-22 (Inclusive Numbers) Lynedoch Place, Including Railings and Arched Lampholders (Lb29275)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "History – MORAY FEU". Morayfeu.com.

- ^ "GENERAL REGISTER HOUSE" (PDF). Nrscotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Charlotte Square, West Register House (Former St George's Church) (Lb27360)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "1 Dean Bridge, Holy Trinity Church (Formerly Scottish Episcopal Church) (Lb27059)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "The City of Edinburgh Planning Local Review Body (Panel 3)" (PDF). The City of Edinburgh Council. 25 January 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "The Ultimate Guide to Edinburgh's West End | Forever Edinburgh". edinburgh.org.

- ^ "(194) - Towns > Edinburgh > 1867-1870 - New Edinburgh, Leith, and county (Business) directory > 1867-1868 - Scottish Directories - National Library of Scotland". digital.nls.uk.

- ^ "St Mary's Episcopal Cathedral Feature Page on Undiscovered Scotland". Undiscoveredscotland.co.uk.

- ^ History of St Marys Episcopal Cathedral

- ^ "Society's History". Iskb.frb.io.

- ^ "About us". Drumsheughgardens.org.uk.

- ^ "The History of The Bonham". Thebonham.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "23-37 (Inclusive Numbers) Drumsheugh Gardens, Including Mews, Boundary Walls and Ancillary Buildings to Rear (Lynedoch Place Lane) (Lb28676)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "1, 2 Rothesay Terrace (Lb29667)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Douglas Gardens, Including Railings (Lb28658)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "Kirk gives its blessing to sale of St George's". Scotsman.com.

- ^ "Buildings - St George's West, Shandwick Place, Edinburgh". Edinphoto.org.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "9-24 (Inclusive Numbers) Learmonth Terrace, Including Railings (Lb29247)".

- ^ a b "1-22 (Inclusive Nos) Clarendon Crescent and 1, 1A Oxford Terrace, Including Railings (Lb28544)".

- ^ "1-13 (Inclusive Nos) Eton Terrace, Including Railings (Lb28737)".

- ^ "The Dean Gardens | Description and History".

- ^ a b "25 Learmonth Terrace, Learmonth House (Lb29248)".

- ^ "1-34 (Inclusive Numbers) Buckingham Terrace, Including Railings and Boundary Walls (Lb28405)".

- ^ "603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron, Royal Auxiliary Air Force".

- ^ a b c d e "West End Conservation Area Character Appraisal" (PDF). Gov.scot. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ a b Fleet, Chris; MacCannell, Daniel (2018). Edinburgh: Mapping the City. Scotland: Birlinn Ltd. p. 226. ISBN 978-1780272450.

- ^ a b Historic Environment Scotland. "Edinburgh, Dewar Place, Central Electricity Generating Station (139288)". Canmore. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Festival Square from the Gazetteer for Scotland". Scottish-places.info.

- ^ "Lothian Road | Edinburgh Attractions". Allaboutedinburgh.co.uk.

- ^ "52, 54, 56 Shandwick Place (Lb30183)".

- ^ "22-30 (Even Numbers) Shandwick Place (Lb30181)".

- ^ "About WL Sleigh LTD, chauffeur hire services in Edinburgh, Scotland".

- ^ "Sainsburys Creates 50 Jobs Move Shandwick Place". scotsman.com.

- ^ "Rossleigh - Graces Guide".

- ^ "Geograph:: Albert Gallery, Shandwick Place,... © Mr H". Geograph.org.uk.

- ^ a b "The History of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art". Nationalgalleries.org. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "#365,000 townhouse for moderator". Heraldscotland.com. 8 October 1998.

- ^ Stewart, Ian (25 January 2017). "A past to be proud of in a world which will always need good journalism". The Scotsman. Retrieved 13 March 2023 – via PressReader.

- ^ "Flagship UK Government Hub in Edinburgh named 'Queen Elizabeth House'". Gov.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Auditor General for Scotland (AGS) Section 22 Report "The Scottish Government Consolidated Accounts 2013/14: Common Agricultural Policy Futures Programme" (PDF). External.parliament.scot. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "'Beyond sad' : EU flag taken down as European Commission closes Scottish base". Thenational.scot. 27 June 2019.

- ^ "Randolph Place Improvements (CCWEL) - City of Edinburgh Council - Citizen Space". Consultationhub.edinburgh.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "EDINBURGH COUNCIL'S CONSULTATION ON IMPROVEMENTS TO RANDOLPH PLACE (CCWEL) : FEBRUARY 2018 - COMMENTS FROM SPOKES" (PDF). Spokes.org.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Great Places to Stay - Sheraton Grand, Edinburgh". Rampantscotland.com.

- ^ "The Exchange, Edinburgh, Lothian Rd". eDinburgharchitecture.co.uk. 14 October 2010.

- ^ "City centre ready for transformation". Theedinburghreporter.co.uk. 10 May 2019.

- ^ "About 2". Newfilmhouse.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "New plans show five underground cinema screens for huge new Edinburgh Filmhouse". Edinburghlive.co.uk. 28 January 2021.

- ^ "Destiny Scotland -The Malt House Apartments". Destinyscotland.com.

- ^ "1-11 (Inclusive Nos) Canning Street Lane and 2 Canning Street, Atholl House (Lb46521)". Portal.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "City of Edinburgh Council Open Spatial Data Portal". Data.edinburghcouncilmaps.info.

- ^ "West Approach Road - Roader's Digest: The SABRE Wiki". Sabre-roads.org.

- ^ "West End Community Council Edinburgh". edinburghwestendcc.org.uk.

- ^ "Boundary Maps | Scottish Boundary Commission".

- ^ "5th Review Constituency Maps (From 2005) | the Boundary Commission for Scotland". bcomm-scotland.independent.gov.uk.

- ^ "Send your comments, suggestions, requests". Scottishartsclub.com.

- ^ "Edinburgh Festival West End Fair - Baigali Designs". Baigali Designs.

- ^ Carponen, Claire. "Edinburgh's New Town and West End Offer Plenty of Old-Fashioned Charm". Mansionglobal.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Behind the scenes with Justerinis in Edinburgh". Scottishfield.co.uk. 17 April 2018.

- ^ "Consulate General Edinburgh". Uk.diplo.de. German Missions in the United Kingdom. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Consulate General of Switzerland in Edinburgh". Swiss Confederation. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Edinburgh Turkish Consulate General". Turkish Government. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Home Page". Consulate General of India. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Honorary Consulate General in Edinburgh". Norway. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "New Zealand High Commission". New Zealand Government. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "The Consulate". Consulate General D'Italia. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Home page". Consulate General of the Russian Federation. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Taipei Representative". Taiwan ROC. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Our Story". Standardlife.co.uk. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Exchange Tower Edinburgh Haymarket Offices". Edinburgharchitecture.co.uk. 10 October 2010.

- ^ "STV Edinburgh HQ". Foursquare.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Kremlin mouthpiece sets up UK base in Edinburgh". HeraldScotland.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Production Companies - Production Guide". Filmedinburgh.org.

- ^ "Contact". Edinburghtrades.org. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Financial Library in Edinburgh's New TownThe Library of Mistakes". The Library of Mistakes. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "The Library of Mistakes". BBC News. 16 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Home Page". Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "History". Drumsheugh Gardens Upkeep Committee. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "New Town Gardens". Parks and Gardens. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Garden". Eglinton and Glencairn Crescents’ Gardens Association. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Rutland Square". City of Edinburgh Council. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Atholl Crescent Garden". City of Edinburgh Council. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b Historic Environment Scotland. "Edinburgh, Coates Crescent, Gladstone Memorial (146163)". Canmore. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "AIDSmemorial.info". aidsmemorial.info.

- ^ "AIDS Memorials in the UK – AIDS Memory UK".

- ^ "New Town Architecture Walking Tour (Self Guided), Edinburgh, Scotland". Gpsmycity.com.

- ^ "Athens of the North". Ewh.org.uk. 24 November 2017.

- ^ "Scottish Liberal Club - History". Scottishliberalclub.org.uk.

- ^ "Scottish Arts Club". Scottishartsclub.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Scots Guards Club in Edinburgh | Visitors & Members Welcome". Scotsguardsclub.co.uk/. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Edinburgh Sports Club". Edinburghsportsclub.co.uk.

- ^ "Home Page". West End Medical Practice. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "New medical centre ready for business at the West End". The Edinburgh Reporter. 13 March 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "HAYMARKET TERRACE, HAYMARKET STATION ENTRANCE AND OFFICE BLOCK WITH STEPS, RAILINGS, AND LAMP STANDARD (Category A Listed Building) (LB26901)". Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Haymarket Station officially opened by Transport Minister". BBC News. 19 December 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "News | Edinburgh News". Edinburghnews.scotsman.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "West End". Edinburgh Trams. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ MacFarlane, Felicity (Summer 2016). McKinnon, Gillian (ed.). "On Song at St Mary's". The Edge. 20 (4). The Diocese of Edinburgh in the Scottish Episcopal Church.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "CHESTER STREET AND PALMERSTON PLACE, ST MARY'S CATHEDRAL (EPISCOPAL), WALPOLE HALL AND SONG SCHOOL (Category A Listed Building) (LB27448)". Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "TORPHICHEN STREET, FORMER TORPHICHEN STREET EDUCATION CENTRE, INCLUDING JANITOR'S HOUSE, GATES, GATEPIERS, BOUNDARY WALLS AND RAILINGS (Category B Listed Building) (LB43888)". Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Fettes College | Scotland's Boarding Schools". Scotlandsboardingschools.org.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Find Us, Map, Routes & Directions - St George's Girls School Edinburgh". Stge.org.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Edinburgh, Coates, Palmerston Place, St Mary's Episcopal Cathedral (88783)". Canmore. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Palmerston Place, Cathedral Church of St. Mary (Episcopal) (Category A Listed Building) (LB27441)". Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "St. Mary's Episcopal Cathedral". Emporis. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Historic Environment Scotland. "Edinburgh, 58 Shandwick Place, St George's West Church (146453)". Canmore. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b Historic Environment Scotland. "SHANDWICK PLACE ST. GEORGES WEST CHURCH, (CHURCH OF SCOTLAND) (Category A Listed Building) (LB27367)". Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Edinburgh, 12 Palmerston Place, Palmerston Place Church (120746)". Canmore. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "12 PALMERSTON PLACE, PALMERSTON PLACE CHURCH INCLUDING WALL AND RAILINGS (Category A Listed Building) (LB27220)". Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Our History". Palmerston Place Church. 22 May 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2021.