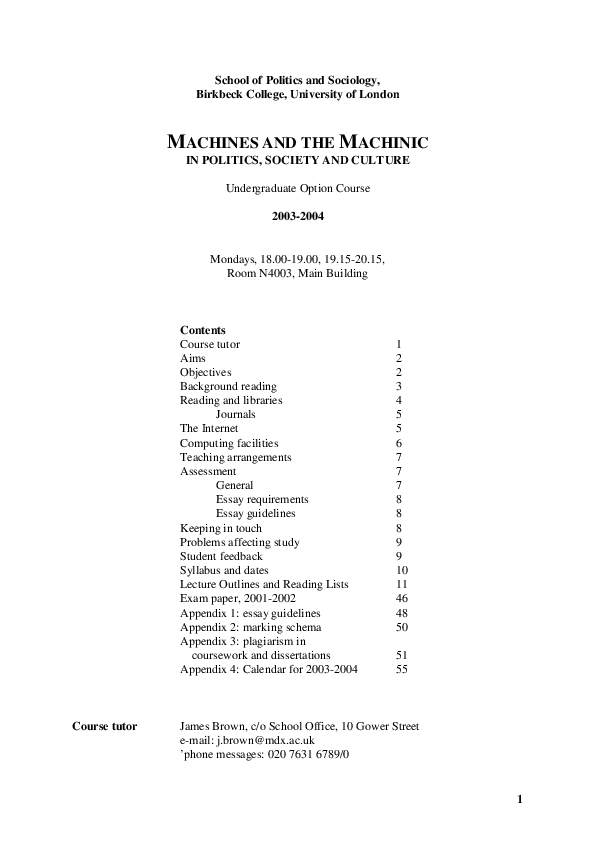

School of Politics and Sociology,

Birkbeck College, University of London

MACHINES AND THE MACHINIC

IN POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CULTURE

Undergraduate Option Course

2003-2004

Mondays, 18.00-19.00, 19.15-20.15,

Room N4003, Main Building

Contents

Course tutor

Aims

Objectives

Background reading

Reading and libraries

Journals

The Internet

Computing facilities

Teaching arrangements

Assessment

General

Essay requirements

Essay guidelines

Keeping in touch

Problems affecting study

Student feedback

Syllabus and dates

Lecture Outlines and Reading Lists

Exam paper, 2001-2002

Appendix 1: essay guidelines

Appendix 2: marking schema

Appendix 3: plagiarism in

coursework and dissertations

Appendix 4: Calendar for 2003-2004

Course tutor

1

2

2

3

4

5

5

6

7

7

7

8

8

8

9

9

10

11

46

48

50

51

55

James Brown, c/o School Office, 10 Gower Street

e-mail: j.brown@mdx.ac.uk

’phone messages: 020 7631 6789/0

1

�Aims

Technology looms large in modern, industrial societies, both as concrete, economic

fact, and as idea and symbol. It has become an intriguingly and awkwardly overdetermined

term: so much so that it can seem that the more insistently we speak of technology as such the

less sure we are what we mean. On the one hand, we reach for technology as explanatory

model and as fact the better to understand and control our world; on the other we invest it

with such mystique as almost either to worship or demonize it, and often fear it is getting out

of control -- possibly to control us. The modern version of Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?

sometimes seems to be What technology will regulate technology for us? IT has a certain

vogue as a likely candidate; but that only begs the further question: What will regulate IT?

Technology is complexly and variously concerned with power and powers: we reach

for it to enhance our powers (though often fear we forfeit them by so doing, as, for example,

when craft workers are deskilled by new technologies); we also engage in it as the only

decisive way of demonstrating our powers; and both as image and as fact it is readily seen not

merely as a political tool but as the entire political system. This is an idea Hobbes starts

running with his image of the state as a clockwork, artificial man, and it persists in talk of

machinery of government and the political or party machine. The idea gets a further twist as

states increasingly assert power and control by means of various technologies, so it’s unclear

when we think of states in machinic terms whether we’re indulging in metaphor or

metonymy.

The aim of the course is to explore the interplay between cultural, political, social and

material processes, and the terms available in which to conceive and govern them, as

manifested in the impact of machines as idea, metaphor and fact. The course is organised

into an approximately chronological selection of topics. But it is not an historical survey: so

no careful history of the Industrial revolution, for example. In looking backwards, the course

seeks issues that are of immediate concern to us now, and which historical perspective might

help us to reappraise.

The earliest sections of the course introduce a world in which machines as ideas and

facts are starting to develop their characteristic and slippery ambiguity in relation to the

material and the ideal. But it’s a world in which mentality and experience have arguably yet

to be radically recast by the idea of technology as such. The ‘machine’ as a model of

explanatory orderliness, self-regulating autonomy and tireless productivity affects this world

only in part. A simple way into the course is to see it as charting some of the complex, often

contested, uneven and not necessarily inevitable processes by which certain cultures come to

be permeated by uses and concepts of machinery, and the ways in which these impinge upon

(for example) forms of society, organization, power, legitimation, decision-making, selfunderstanding, work, and culture.

Besides the idea of the machine, the course is drawn together by several recurrent

issues, such as the autonomy of technology, the relation between technology and political or

social control, and the problem of rationality vis-à-vis culture.

Objectives

Students taking this course will continue to develop their skills in evaluating evidence and

argument, and in oral and written presentation. They will cultivate particular expertise in

2

�exploring a complex theme in relation to a wide variety of materials, drawn from various

discourses and from material culture. They will acquire a broad understanding of what has

become a pervasive issue in industrial civilization, and will assess and criticize different ways

of reflecting upon this in a theoretically sophisticated and historically informed way.

Background reading

Aronowitz, Stanley, Barbara Martinson & Michael Menser, Eds, 1996, Technoscience and

Cyberculture, New York: Routledge.

Cutcliffe, Stephen H. Terry S. Reynolds, Eds., 1997, Technology and American History: an

historical anthology from Technology and Culture, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Durbin, Paul T., Ed., 1980, Guide to the Culture of Science, Technology and Medicine, New

York: Free Press.

Andrew Feenberg & Alastair Hannay, Eds., 1995, Technology and the Politics of Knowledge,

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Jennings, Humphrey, 1987, Pandaemonium 1660-1886: The coming of the machine as seen

by contemporary observers, ed. Mary-Lou Jennings & Charles Madge [1985], London:

Picador.

Landes, David S., 1969, The Unbound Prometheus: Technological change and industrial

development in Western Europe from 1750 to the present, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Melzer, Arthur M., Weinberger, Jerry, & Zinman, M. Richard, Eds., 1993, Technology in the

Western Political Tradition, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Mitcham, Carl, 1994, Thinking Through Technology: The Path between Engineering and

Philosophy, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mumford, Lewis, 1934, Technics and Civilization, New York: Harcourt Brace.

Mumford, Lewis, 1967, The Myth of the Machine Vol. 1: Technics and Human Development,

New York: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich Inc.

Mumford, Lewis, 1970, The Myth of the Machine Vol. 2: The Pentagon of Power, New York:

Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich Inc.

Olson, Richard, 1990, Science Deified and Science Defied: The Historical Significance of

Science in Western Culture, vol. 2., Berkeley: University of California Press

Pacey, Arnold, 1983, The Culture of Technology, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Pacey, Arnold, 1999, Meaning in Technology, Cambridge Mass: MIT Press.

3

�Pursell, Carroll, 1994, White Heat: People and Technology, London: BBC Books.

Rhodes, Richard, Ed., 1999, Visions of Technology: A Century of Vital Debate about

Machines, Systems and the Human World, New York: Simon & Schuster.

Whitehead, Alfred North, 1932, Science and the Modern World [1926], Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Winner, Langdon, 1977, Autonomous Technology: Technics-out-of-control as a Theme in

Political Thought, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Reference

Bunch, Bryan & Alexander Hellemans, Eds., 1994, The Timetables of Technology: A

Chronology of the Most Important People and Events in the History of Technology, New

York: Simon and Schuster.

Day, Lance & Ian McNeil, 1996, Eds., Biographical Dictionary of the History of Technology,

London: Routledge.

Walker, Peter M.B., Ed., 1995, Larousse Dictionary of Science and Technology, Edinburgh:

Larousse.

Bibliographies published annually in Technology and Culture [available in ULL]

Reading and libraries

Although lectures and seminars constitute an essential element of the course, your learning

depends largely on the reading and research that you undertake personally. With this in mind,

please make sure that you register with the libraries listed below as soon as possible. You

should also acquaint yourself with the periodicals that are available on-line as e-journals.

These are accessible, free and direct to your PC, via the Birkbeck College Library website —

http://www.bbk.ac.uk/lib/ejournal.html. Most importantly, try to get into the habit of regular

reading and preparation for your weekly classes. Your success in this course, as well as your

enjoyment of it, will be directly related to regular participation and the amount of reading that

you accomplish throughout the year. Most of the items listed in the reading list below can be

found in the Birkbeck College Library, in the Malet Street building, which is open seven days

a week for most of the year. In addition, the Library provides an increasing number of on-line

services, including JSTOR and Ingenta (formerly, BIDS) are available in the Library. The

Library produces a comprehensive set of guidelines about how to use it and other libraries.

Together with other useful information, they are available on the Library website at

http://www.bbk.ac.uk/lib/. Those books or journals which are not in the College Library can

usually be found in collections close by, for example, at the University of London Library at

Senate House, and the British Library of Political and Economic Science (BLPES) at the

London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

It is important that you familiarise yourself with these libraries—what they hold in their

collections, when they are open, how access can be obtained, what your borrowing rights are,

whether remote access is possible, and what specialist features (e.g. electronic and on-line

4

�sources, short loan facilities, etc.) are available—as soon as possible. Sometimes your rights

as a reader may not be clear, so it is always worth inquiring. For example, as a Birkbeck

student you may not enter the BLPES course collection, which holds a wealth of valuable

material but is open only to LSE students. However, you can order items from the course

collection and have them delivered to you in the open part of the library. This can take some

time but it is important to know that you do have this option. The Short Loan Collection in

the College Library is a particularly important resource. It holds many of the essential journal

articles and books for this course.

It is important to make the most of the electronic resources available for this course, both

through the library and on the internet, as well as to use such other libraries as are open to

you. While the School makes every effort to ensure that the library is stocked with the

materials needed for all course units, the number of students will always far exceed the

number of copies of any given text. Planning your reading ahead and diversifying the range of

resources you use will help to avoid the problems that arise from ‘herding’, when 20 or 30

students on a course go in search of the same handful of copies of a core text at the same

time.

Students using the Birkbeck College Library are asked to report any lost or stolen item to the

School as soon as possible, so that steps may be taken to locate or replace it as quickly as

possible. They may notify the School Administrator for undergraduates, Sylvia Cabrera

(s.cabrera@bbk.ac.uk, 7631 6780), the lecturer for this course unit (James Brown,

j.brown@mdx.ac.uk) or the School’s Library Officer Dr. Dionyssis G. Dimitrakopoulos,

D.Dimitrakopoulos@bbk.ac.uk, 7631 6786. When reporting a missing item to the School,

please provide the author’s name, the title and the Birkbeck Library shelfmark.

NB Items that are the main reading for a session are usually marked as being in the Short

Loan Collection (SLC), along with their shelfmarks. This does not mean that there are not

any copies in the rest of the library.

Journals

The following journals are likely to prove useful:

• Impact of Science on Society

• Research in Philosophy and Technology [an annual]

• Science as Culture

• Science, Technology and Human Values

• Social Studies of Science

• Technology and Culture

• Technology in Society

The Internet

The internet is a very important learning resource. Many valuable materials are now available

on-line, but you should be no less critical of the material that you find on-line than you would

be of books and articles. You should endeavour to become a regular user—taught courses are

run by CCS at Birkbeck and a teach yourself course, Tonic, is available in the College

Library—and to familiarise yourself with relevant websites, including the School website at

http://www.bbk.ac.uk/polsoc/. You should visit this site regularly for information about the

5

�course, announcements and messages from course tutors or other students. Please note that

where you use it material available on the Internet needs to be cited as punctiliously as any

article or book.

Besides the School website at http:www.bbk.ac.uk/polsoc/ the following contain handy links

for issues in this field:

http://shot-dev.jhu.edu/

Society for the History of Technology -- publishers of Technology and Culture

http://echo.gmu.edu/center/index.html

Specializes in links to sites specializing in history of science and technology

http://www.alteich.com

Specializes in study of technology

http://radburn.rutgers.edu/andrews/projects/ssit/default.htm

IEEE Society on Social Implications of Technology

http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk

Museum of the History of Science, Oxford University

There are also some web-based journals which are worth keeping an eye on, among them:

Wired

First Monday

Culture Machine

http://www.wired.com

http://www.firstmonday.dk.issues

http://culturemachine.tees.ac.uk

And many, many more sites...

If you find anything especially useful, do mention it to the rest of the group.

For this course experience of this and other data-systems might also be deemed fieldwork as

well as research. As you use it you might try to notice how the experience of following up

references and hunting for information affects you. What kind of intereaction (or passivity)

does it foster? Some people see new forms of society and politics in this. Do you?

And remember that the pearls are cast in the midst of a lot of dross. For every worthwhile

item there are scores of inane, misleading, and insane ones.

Computing Facilities

Workstation rooms, provided by Central Computing Services (CCS), are available at a

number of locations in the College. CCS produces useful information sheets on a range of

IT-related subjects and runs training sessions on various aspects of IT use. Information is

available on-line at http://www.bbk.ac.uk/ccs/. All students are automatically given a

password at the beginning of term for use of computers and e-mail. If you do not receive a

password, you should contact CCS directly (020 7631 6298).

6

�Teaching Arrangements

The course is taught through a combination of lectures and student-led discussion. A lecture in

the first hour will identify the main themes and debates for each given topic. The second hour

will take the form of organised student-led discussion. Class discussion will relate to the lecture

and may be structured around a particular piece of assigned reading, or a presentation by one of

the group.

Regular attendance at classes is essential. You should contact either one of us or the School

Office (020 7631 6789/0) if you are unable to come to a particular session.

The work for each seminar is set out below, and it is expected that all students will have read the

relevant required reading and be prepared to participate in discussion.

Classes will take place between 6.00 and. 8.15. on Monday evenings in room N4003 in the

Main Building.

Assessment

General

When writing your essay, please make use of the essay guidelines (Appendix I), which are

intended to offer advice on academic conventions, including referencing, and style. You will

also find the Marking Schema, which outlines the criteria that will be used in evaluating your

written work, towards the end of this coursebook (Appendix II). You should note, crucially,

that all work submitted for assessment must be your own. Before beginning your first

piece of coursework, please ensure that you are clear about the concept of plagiarism and

how to avoid it (see Appendix III). Regrettably, instances of plagiarism are on the increase,

and the School and the College have been compelled to impose severe penalties where

plagiarism is detected.

The assessment for this course is by unseen written examination taken at the end of the

academic year. This method of assessment encourages and tests the development of subjectspecific understanding and knowledge, skills of analysis, evaluation and problem solving, and

encourages study across the breadth of the syllabus. It discourages plagiarism.

However, you are strongly encouraged to submit two essays of c.1500 words, the first on or

before 12 December 2003 and the second on or before 26 March 2004. Though these will not

count towards your final mark, writing these essays is an extremely valuable exercise. They

enable us to monitor your progress, allow you an opportunity to receive feedback on your

work, and give students returning to education an opportunity to adjust to the discipline of

writing without jeopardising their final results. To wait until the exam before working out

how to formulate your ideas is to wait too long. There’s nothing like writing for making one

find out what one thinks. You can use the essay questions that accompany each week’s

reading, or one of the questions from the past exam paper (included in this coursebook).

There will also be an opportunity to sit a mock exam paper towards the end of the course.

7

�Essay Requirements

Two copies of each essay are to be submitted to the School office. Each copy is to be

accompanied by a cover sheet (available from outside the School office and on the School

website). All essays should be typed or word-processed, double-spaced and printed in a font

of a readable size. All essays should give explicit acknowledgement to sources. Although a

bibliography should be included in all essays, this does not exhaust this requirement.

Quotations should be attributed and ideas used in the text should be referenced. Students are

advised to use the Harvard system of referencing. There are serious penalties for plagiarism—

the copying or close paraphrasing of published or unpublished work—which is regarded as a

serious office by the College.

Late essays carry a penalty unless an extension has been agreed with the lecturer in charge of

the course – not the School administrative staff. The mark for an essay submitted late without

an agreed extension (or after the extension deadline) will be reduced by 2% per working day.

Students are responsible for ensuring that their essays and dissertations reach the School on

time, no allowance can be made for the loss of work that is posted, or for the loss of work

dispatched via a third party. Essays arriving late through the post will be considered to have

arrived on time where the postmark is not later than the day before the actual deadline.

Essay Guidelines

Essays should always present an argument in answer to the chosen question and not just

rehearse what you know about the subject. An essay should provide an analysis of the subject

rather than consisting merely of description. The argument should be put forward coherently,

and be substantiated by factual or textual evidence. It should respond precisely to the question

posed. Your argument should be sustained from the first paragraph to the last, with each

paragraph contributing in some way to the support or elucidation of your larger multi-stage

argument. The first paragraph is particularly important in organising your essay. It should

address the question directly and crisply, and introduce the argument that you intend to make.

Simplicity of expression throughout is strongly preferred to purple prose. Marks will be

awarded according to the quality, clarity and coherence of the argument presented in the

essay, the essay’s structure, how well supported by evidence the main claims of the essay are,

and whether reference is made to the relevant literature.

It’s usually, therefore, a good idea to set aside some time to thinking about the precise terms

of the question, and reflecting upon what ways there might be of interpreting and answering

it. There are often several possibilities. It’s also often wise to leave oneself time to revise the

essay. Especially if you only find out what you’re arguing as you write, revision can be

crucial to bringing the argument to the fore, and making it consistent. Ideally, by the time you

sit down to write the final version of an essay, you’ll already know what the conclusion is

going to be. Every paragraph should in some way help to lead one to that conclusion.

If you’d like to discuss an essay you’re working on, do get in touch with me to arrange a

tutorial.

Detailed guidance on the substance, presentation and referencing of essays is given in

appendices 1-3 in this coursebook.

8

�Keeping in Touch

If you’d like to meet to discuss any aspect of our work, do contact me to arrange a meeting.

E-mail me (j.brown@mdx.ac.uk), or leave me a message and your ‘phone number by calling

the School Office (020 7631 6789/0), or have a word after class.

Problems affecting study

If a problem arises which is affecting your studies, you are encouraged to discuss the matter

with any of your personal tutor in the first instance, your programme director or the Head of

School, Professor Peter John (020 7631 6783, p.john@bbk.ac.uk). Alternatively, you might

contact the Students’ Union or any of the College services listed in the Programme Handbook.

Student Feedback

The School believes that student feedback is important to the quality of its provision. It

invites you to make your views known or to raise issues through the following formal

channels:

Class Representatives are elected in the third week of the winter term. They represent the

class in the Student's Union and at the Student-Staff Exchange Meetings (see below), and

can also approach the programme director or the Head of School to raise issues on behalf

of the class or individuals in the class.

Student-Staff exchange meetings are scheduled for 17 November 2003 and 23 February

2004. All students are invited, and class representatives are expected to attend.

A Course Evaluation Questionnaire is completed and submitted in the spring term.

Students are asked to comment on the course and the quality of teaching. Responses are

collated and summarised in a course review, presented by the course director to the School

Teaching Committee, where they are discussed. The course director examines the issues

raised and identifies the follow-up action which is to be taken. A summary is posted on

the School noticeboard following the meeting, and a report is presented by the Student

Liaison Officer at the next Student-Staff Exchange Meeting.

Personal Tutors will communicate any concerns you have to the relevant tutor, teacher or

administrator. This is a good way of giving feedback to us privately.

9

�Syllabus and Dates

Date

No.

Topic

29 September

6 October

13 October

20 October

27 October

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Introduction

The Social and Cultural Life of Early Modern Science

Clockwork and Authority

Machines for Making States and Souls: Guns and Print

Mechanism in Eighteenth-century Social Thinking

3 November

10November

17 November

24 November

1 December

8 December

READING WEEK

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

Romanticism: Organicism / Mechanism

Critiques of the Enlightenment: Instrumental Rationality

Political Economy of Machines

Technology, Religion and the Sublime

Technology / History: The Technological Determinism

Debate

CHRISTMAS VACATION

12 January

19 January

26 January

2 February

9 February

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16 February

23 February

1 March

8 March

15 March

22 March

Biology / Technology

Philosophy / Technology

Political Machinery

The Private Life of Machines

Technology and work: Taylorism and its aftermath

READING WEEK

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

Technology and Modern War

Machine Art

Luddites or Prophets? Some Critics of Technology

Can we choose? Technology and Social Policy

Toys for Boys? Feminism and Technology

EASTER VACATION

26 April

3 May

10 May

17 May

10

21.

22.

23.

24.

Information and Communication

BANK HOLIDAY

Posthumanism

Revision

�LECTURE OUTLINES AND READING LISTS

1. Introduction

We’ll consider the scope of the course and its limits (especially its focus on the west),

and consider the construction of the category of ‘technology’. We’ll review various

definitions of technology (as artefact, system, process, as more or less social or (alternatively)

purely technological); and some of the different ways of discussing technology, such as

history of technology, or the various things gathered in the category philosophy of technology,

and the ways different kinds of approach generate different kinds of discourse -- something

illustrated by an initial look at the argument between technological determinism and social

constructivism (see also week10). We’ll reflect on some of the problems of discussing

technology, especially the idea of ‘the problem of technology’, and the tendency to frame

discussion in terms of dualisms, such as nature vs. artifice, mechanism vs. organism, and the

problem of the ideas of control and freedom. With an eye on next week’s topic, we’ll think

about the relation of technology to rationality and to science.

Reading

Archer, Margaret S., 1990, ‘Theory, Culture and Post-Industrial Society,’ Theory, Culture,

Society, 7 iii: 97-119.

Carroll, John, 1993, Humanism: the Wreck of Western Culture, London: Fontana.

Gellner, Ernest, 1992, Reason and Culture, Oxford: Blackwell.

Hall, John, 1985, Powers and Liberties: the causes and consequences of the rise of the west,

Oxford: Blackwell.

Bernard Joerges, 1990, ‘Images of Technology in Sociology: Computer as Butterfly and Bat,’

Technology and Culture, 31: 203-27.

Kass, Leon R., ‘Introduction: The Problem of Technology’ in Melzer, Arthur M., Weinberger,

Jerry, & Zinman, M. Richard, Eds., 1993, Technology in the Western Political Tradition,

Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Mitcham, Carl, 1994, Thinking Through Technology: The Path between Engineering and

Philosophy, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, chs. 7-10, esp. ch. 7.

Sheehan, James J. & Morton Sosna, Eds., 1991, The Boundaries of Humanity: Humans,

Animals, Machines, Berkeley: University of California Press.

2.The Social and Cultural Life of Early Modern Science

The early modern period is often deemed to have witnessed a scientific revolution, at

the heart of which was a mechanical conception of nature, and from which modern science

11

�develops. We’ll be questioning this, by looking at the social and cultural origins of what

becomes modern science, and considering ways in which it was embedded in early modern

society. We’ll consider science’s uncertain differentiation of itself from other discourses, its

debts to earlier periods, and its positioning in these highly stratified societies. Science is

usually deemed crucial to processes of modernization and rationalization, which are

commonly contrasted to traditional cultures, which they’re seen as uprooting or transforming.

We’ll look at the Weberian problem of how such a discourse could arise within a culture, and

look at Merton’s Weberian case regarding Puritanism and modern science. We’ll take a

preliminary look at the kind of world this science posits, and ask whether at this point it

makes more sense to think of science as applied technology, or technology as applied science.

We’ll take a preliminary look at science in relation to issues of social, political and

epistemological authority (i.e. the sociology of scientific knowledge) -- something we’ll take

up again next week.

Main reading

Porter, Roy & Mikulás Teich, Eds., 1992, The Scientific Revolution in National Context,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. SLC (509.4031SCI)

[John Henry’s chapter on ‘The Scientific Revolution in England’, and, should time allow,

L.W.B.Brockliss’s on France, and Mario Biagioli’s on Italy]

Other reading

Cohen, H. Floris, 1994, The Scientific Revolution: a historiographical inquiry, Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Cohen, I. Bernard, Ed., 1990, Puritanism and the Rise of Modern Science: The Merton

Thesis, New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press

Dear, Peter, 2001, Revolutionizing The Sciences: European knowledge and its ambitions,

1500-1700, Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Debus, Allen G., 1980, Man and nature in the Renaissance, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Dijksterhuis, E.J., 1961, The Mechanization of the World Picture, trans. C. Dikshoorn,

Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Grant, Edward, 1996, The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Jacob, J.R., 1975, ‘Restoration, Reformation and the Origins of the Royal Society,’ History of

Science, 13: 155-76.

Jacob, Margaret, 1988, The Cultural Meaning of the Scientific Revolution, New York: Alfred

A. Knopf.

Jacob, Margaret, 1997, Scientific Culture and the Making of the Industrial West, New York:

Oxford University Press.

12

�Pumfrey, Stephen, et al., Eds., 1991, Science, Culture and Popular belief in Renaissance

Europe, Manchester, Manchester University Press

Rossi, Paolo, 1968, Francis Bacon: from magic to science, London: Routledge and Kegan

Paul. NIL.

Rossi, Paolo, 1970, Philosophy, Technology and the Arts in the Early Modern Era, trans.

S.Attanasio, New York: Haper Torchbooks.

Rossi, Paolo, 2001, The Birth of Modern Science, trans. Cynthia De Nardi Ipsen, Oxford:

Blackwell

Shapin, Steven, & Schaffer, Simon, 1985, Leviathan and the Air Pump, Princeton: Princeton

University Press

Shapin, Steven, 1996, The Scientific Revolution, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Shapin, Steven, 1994, A Social History of Truth: civility and science in seventeenth-century

England, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stewart, Larry, 1992, The Rise of Public Science: Rhetoric, technology and natural

philosophy in Newtonian Britain, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thomas, Keith, 1973, Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in

Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England [1971], Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Yates, Frances, 1964, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, London: Routledge and

Kegan Paul.

Essay Question

Discuss some of the ways in early modern science drew upon, and was affected by, the social

and cultural resources of the Europe in which it was practised.

3. Clockwork and Authority

We’re thinking this week about the relation of early modern science and of

mechanical ideas and images to politics and power. The background to this is bloody

political turbulence in the wake of the Reformation. Concepts of power and control adopt

specifically mechanistic forms. In a world where fear of damnation was common, and history

a process of increasing decay, Bacon’s early seventeenth-century project to use science to

improve the human condition (or "Man’s Estate") stands out -- and begs questions about

different kinds of power and order, mechanical and political. Descartes and Hobbes use

mechanical images to propose a model of order and control. This has some implications for

fundamental social theoretical issues, such as human agency and freedom. It also starts to

affect forms of social organisation and division of labour.

13

�Main reading

Merchant,Carolyn, 1990, The Death of Nature, rev. edn., San Francisco: Harper & Row, chs.

8-9. SLC (304.2MER)

Other reading

Bacon, Francis, The New Atlantis [any edn.]

De Solla Price, Derek, 1975, ‘Automata and the Origins of Mechanism and Mechanistic

Philosophy’, rptd. in Science Since Babylon, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hobbes, Thomas, 1651, Leviathan, esp. introduction.

Jacob, James R. & Margaret C. Jacob, 1980, ‘The Anglican Origins of Modern Science: The

Metaphysical Foundations of the Whig Constitution,’ Isis, 71: 251-67.

Latour, Bruno, 1993, We Have Never Been Modern [1991], trans. Catherine Porter, New

York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Mayr, Otto, 1986, Authority, Liberty and Automatic Machinery in Early Modern Europe,

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, chs. 2-5, esp. chs. 4-5.

Rabb, Theodore K., 1975, The Struggle for Stability in Early Modern Europe, New York:

Oxford University Press.

Schmitt, Carl, 1996, ‘The State as Mechanism in Hobbes and Descartes’ [1937], in The

Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes, trans. George Schwab & Erna Hilfstein,

Westport CT, Greenwood Press.

Sarasohn, Lisa, 1985, ‘Motion and Morality: Pierre Gassendi, Thomas Hobbes and the

Mechanical World View,’ Journal of the History of Ideas 46 (1985): 363-79.

Spragens, Thomas A., 1973, The Politics of Motion, London: Croom Helm.

Richard Westfall, 1977, The construction of Modern Science: Mechanisms and Mechanics,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Winner, Langdon, 1977, Autonomous Technology, Cambridge Mass: MIT Press

Essay Question

What were the political implications of mechanical ideas in the early modern period?

4. Machines for Making States and Souls: Guns and Print

We’re turning this week from mechanical ideas to actual devices: early modern

military and information technologies, or, plainly, guns and print. They’re significant partly

because they impinge upon a whole society -- indeed, it can be argued that they play a role in

14

�starting to constitute a single society vis-à-vis the state, where formerly there’s been

intermittent and uncertain control, and life was mostly organized locally and self-sustainingly.

We’ll consider how these technologies are used, and how they are shaped. In particular we’ll

look at arguments over their effects on forms of socio-political organisation and forms of selfunderstanding and self-cultivation (especially in the case of print). This begs questions about

possible relations between technologies, forms of organisation, and the character of the

human.

Main reading

Pacey, Arnold, 1992, The Maze of Ingenuity: Ideas and Idealism in the Development of

Technology, 2nd edn., Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. chs. 4 & 6. SLC o/o

Other reading

Anderson, Benedict, 1991, Imagined Communities, rev. edn, London: Verso, esp. ch. 3.

Black, Jeremy, 1991, A Military Revolution? Military Change and European Society 15501800, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Braudel, Fernand, 1981-4, Civilization and Capitalism, 3 vols., London: Fontana, vol. 1, The

Structures of Everyday Life, ch. 6.

Downing, Brian M., 1992, The Military Revolution and Political Change: origins of

democracy and autocracy in early modern Europe, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth, 1979, The Printing Press as Agent of Change, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Goody, Jack, 1986, The Logic of Writing and the Organization of Society, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

McLuhan, Marshall, 1962, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man,

Toronto: Toronto University Press.

Ong, Walter, 1982, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, London: Methuen

Parker, Geoffrey, 1988, The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the

West, 1500-1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. SLC

Essay question

Explain the role played by one or more early modern technologies in chnaging the nature of

political institutions and action.

5. Mechanism in Eighteenth-Century Social Thought

We’re turning this week to a moment some way after the seventeenth-century crisis,

when the imposition of social order seemed to many a less urgent task -- indeed, concepts of

15

�order as immanent in the nature of social and economic processes start to appear, and

mechanical images and concepts are arguably intrinsic to them.

We’ll look at the eighteenth-century project of a human science, and the role of

mechanistic, often (allegedly) Newtonian, thinking in it. Followed through remorselessly it

could be controversial, as in La Mettrie’s L’Homme-Machine which posits a mechanical,

materialist theory of human nature. Usually, though, mechanistic ideas were annexed to

visions of providential order, while claiming to reserve some unique difference to distinguish

at least the human individual, if not the group.

We’ll review Otto Mayr’s case that in political, social and economic life models of

organisation based on (human) control give way to an emphasis on self-regulating

mechanisms, such as that proposed in economic life by Adam Smith, which figure in early

liberal social and political thinking. We’ll reflect on the ambiguities over mechanism and

nature here, and develop our thinking about human subjectivity and agency and forms of

power in relation to this material -- especially in debates in the period concerning necessity,

freedom, and ethics. By the end of the period, we’ll see providentialist, self-regulating

mechanisms start to give way to the possibility of social engineering, especially in the work of

Bentham. We’ll return to this in considering the political economy of machines in week 8,

and touch on it in connexion with Foucault in week 7.

Main reading

Otto Mayr, 1986, Authority, Liberty and Automatic Machinery in Early Modern Europe,

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, chs. 9-11. SLC o/o

Other reading

Becker, Carl L., 1959, The Heavenly City of the Eighteenth-Century Philosophers [1932],

New Haven: Yale University Press, esp. ch. 2.

Bentham, Jeremy, 1995, The Panopticon Writings, ed. Miran Bozovic, London: Verso.

Cassirer, Ernst, 1951, The Philosophy of the Enlightenment, Boston: Beacon Press. SLC

Cohen Rosenfield, Leonora, 1968, From Beast Machine to Man Machine: Animal Soul in

French Letters from Descartes to LaMettrie, 2nd edn., New York: Octagon Books.

Knight, Isabel, 1968, The Geometric Spirit: The Abbe Condillac and the French

Enlightenment, New Haven: Yale University Press.

La Mettrie, Julien Offray de, 1912, Man a Machine, French with English translation, La Salle

IL: Open Court. [or any other edition]

MacIntyre, Alasdair, 1967, A Short History of Ethics, London: Routledge, chs. 11-13.

Olson, Richard, 1990, Science Deified and Science Defied: The Historical Significance of

Science in Western Culture, vol. 2., Berkeley, University of California Press, ch. 6

Rousseau, G.S., Ed., 1990, The Languages of Psyche, Mind and Body in Enlightenment

Thought, Berkeley: University of California P.

16

�Thomas, Keith, 1984, Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England, 15001800 [1983], Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Vartanian, A., 1960, La Mettrie’s ‘L’Homme Machine’, Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

Yolton, John, 1983, Thinking Matter: Materialism in 18th-Century Britain, Minneapolis: U.

of Minnesota P.

Wellman, Kathleen, 1992, La Mettrie: medicine, philosophy, and enlightenment, Durham

N.C.: Duke University Press

Willey, Basil, 1940, The Eighteenth Century Background, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Essay question

‘In the mid-eighteenth century, before the social problems brought by industrialization, the

idea of society as mechanistic was not dehumanizing, but reassuring and providential.’

Discuss.

6. Romanticism: Organicism / Mechanism

At the risk of crude simplification, the Enlightenment espouses reason (often in the

context of an elite, cosmopolitan high culture), and Romanticism reacts against this. It poses

fundamental questions about creativity and the true sources of vitality, and in the process

develops an often quasi-religious response to Nature. By comparison the mechanistic is often

seen as inauthentic or dehumanizing. This construction and evaluation of organicism and

mechanism is in some ways still current, and continues to inform the way we organise and

conduct our affairs (e.g in the value we attach to wildernesses and places of such natural

beauty that we restrict development of them).

But while often elevating imagination and creativity, Romantic writers also register

deep unease about our own capacity for creation, especially for self-creation, and there’s often

a kind of secularized spiritual anguish over the ideas of our being both creators, and creatures

-- created entities, perhaps crudely recreated by incompetent human intervention, instead of

being produced by nature. These are ideas that had been formulated by Rousseau, which

would inform critiques of what industrialiation was doing to the human spirit in the

nineteenth century, and which still impinge on, for example, some of our representations of

cyborgs, and our responses the things for which they stand.

Frankenstein raises many of these religious and philosophical questions in compelling

form, and offers besides a proto-feminist critique of a masculine and arrogant creativity that

destroys more than it makes. This is a story of biotechnology run mad, nemesis and male

arrogation of the power to give birth. Not surprisingly Frankenstein has become a powerful

myth of our relations with technology and nature.

Main reading

Shelley, Mary, 1996, Frankenstein, ed. J.Paul Hunter, New York: W.W.Norton. [1993 edn.,

ed. M. Butler in SLC (YHK, S4/Of8 [She])] [any decent edition will do, but this one usefully

includes a lot of contextual and critical material]

17

�Other reading

Abrams, M.H., 1953, The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic theory and the critical tradition,

New York: Oxford University Press

Cantor, Paul, 1984, Creature and Creator: Myth-Making and English Romanticism,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, esp. ch. 4.

Cantor, Paul, 1993, ‘Romanticism and Technology: Satanic Verses and Satanic Mills,’ in

Melzer, Arthur M., Weinberger, Jerry, & Zinman, M. Richard, Eds., 1993, Technology in the

Western Political Tradition, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Coleridge, S.T., Biographia Literaria [any edition]

Cunningham, Andrew & Nicholas Jardine, Eds., 1990, Romanticism and the Sciences,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hindle, Maurice, 1994,

Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Mary

Shelley:

Frankenstein,

Penguin

Critical

Studies,

Mitcham, Carl, 1994, Thinking Through Technology: The Path between Engineering and

Philosophy, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, epilogue.

Olson, Richard, 1990, Science Deified and Science Defied: The Historical Significance of

Science in Western Culture, vol. 2., Berkeley: University of California Press

Rousseau, G.S., Ed., 1972, Organic Form: The Life of an Idea, London: Routledge & Kegan

Paul.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe, ‘A Defence of Poetry’ [any edition]

Tarnas, Richard, 1996, The Passion of the Western Mind [1991], London: Pimlico, ch. 6.

Whitehead, Alfred North, 1932, Science and the Modern World [1926], Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Essay question

Discuss some of the ambiguities in the understanding of society and culture opened by

Romanticism’s exploration of the dualism of organicism and mechanism.

7. Critiques of the Enlightenment: Instrumental Rationality

Last week we considered the criticism of the Enlightenment implicit in the Romantic

reaction against it.. This week we’re turning to the terms in which influential, recent, explicit

critiques of the Enlightenment have been developed. Especially since Max Weber, the idea of

instrumental rationality has loomed large in criticism of the Enlightenment project: the

18

�machine-like adaptation of means to ends, and the systematization of activities, often deemed

to lead to a situation in which only those ends and activities which can be so systematized

persist. In other words, means usurp ends.

Weber advances his critique by arguing that rationalization, though self-sustaining

once under way, and seemingly self-given, has a concealed or repressed genesis, especially in

the spiritual anguish and world-view of Calvinists in the wake of the Reformation.

We’ll consider the conceptions of reason and culture implicit in this case, consider

how it is developed by Critical Theory, and look at the different way in which Foucault

handles related ideas -- especially in his discussion of the Panopticon in the context of his

broader account of normalization and the ‘great confinement’.

This begs some fundamental questions. Some of them we’ve already started thinking

about -- to do, for example, with what we mean by ‘power’ in these different contexts. But

here we’ll also want to probe the idea of instrumental rationality, and ask about its

specifically technological qualities, and consider whether reason per se can in principle be the

grounds of values.

Main reading

Wolin, Sheldon, ‘Reason in Exile: Critical Theory in Technological Society,’ in Melzer,

Arthur M., Weinberger, Jerry, & Zinman, M. Richard, Eds., 1993, Technology in the Western

Political Tradition, Ithaca: Cornell University Press. SLC 321.8 TEC

Other reading

Adorno, T. & Horkheimer, M., 1972, Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. John Cumming, New

York: Herder & Herder.

Foucault, Michel, 1977, Discipline and Punish, London: Allen Lane.

Foucault, Michel, 1986, The Foucault Reader, ed. Paul Rabinow, Harmondsworth: Penguin,

esp. ‘What is Enlightenment?’

Foucault, Michel, 1989, Madness and Civilization, London: Routledge.

Gellner, Ernest, 1992, Reason and Culture, Oxford: Blackwell. .

Habermas, Jurgen, 1987, Knowledge and Human Interests, trans. Jeremy J. Shapiro,

Cambridge: Polity, esp. the overview in the Appendix.

Habermas, Jurgen, 1987, The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, Cambridge: Polity, esp.

ch. 1 on Weber.

Held, David, 1980, Introduction to Critical Theory, Cambridge: Polity, esp. chs. 5, 9 & 11.

Jay, Martin, 1973, The Dialectical Imagination, London: Heinemann, esp. ch. 8.

Murray, Patrick, 1982, ‘The Frankfurt School Critique of Technology,’ Research in

Philosophy and Technology, 5: 223-48.

19

�Schmidt, James, Ed., 1996, What is Enlightenment? Eighteenth-Century Answers and

Twentieth Century Questions, Berkeley: University of California Press. SLC

Turner, Bryan S., 1992, Max Weber: From History to Modernity, London: Routledge, esp. ch.

7, ‘The Rationalization of the Body’

Weber, Max, 1992, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism [1904], trans. Talcott

Parsons, intr. Anthony Giddens, London: Routledge.

Essay question

Is the Enlightenment project vulnerable to the criticism that it enshrines and seeks to impose

on human life a limitedly instrumental rationality?

8. Political Economy of Machines

Industrialization changes the social and political implications of the idea of machines - not least because machines, in increasingly interconnected systematic and even networked

forms are clearly material facts, with certain obdurately unignorable and less than appealing

features -- at least in the ways in which they’d been instantiated. Machinery was clearly

fundamental to the industrial economy, and this in turn was begetting social problems that

cried out for some response, which, given the available machinery for social governance (to

use the inevitable metaphor) were profoundly difficult to respond to.

Political economy proposes techniques for socio-economic governance. Political

economists have things to say specifically about machinery and its economic implications.

But there’s also some sense in which political economy has some of the traits of a machine.

This becomes clear in the way political economic problems sometimes seem to be issues of

data-processing, feedback and control. The participation of the computing pioneer Charles

Babbage in the debate points to this. We’ll ponder the possibility of this being an early

instance of the technological fix: the idea that the answer to the problems thrown up by

technology is more technology. It also relates to the idea of the political process being

remodelled in machine terms -- something Carlyle latches onto, and to which we’ll return in

week 13.

For Marx the situation was rather different: the collapse of bourgeois control of the

economy and of politics was desired. Yet the proletariat’s power is in some ways intriguingly

and ambiguously related to the machinery that they’ve become expert in using. Marx’s

attitude to machinery is complex. We’ll look at the different ways in which it could seem

both dehumanizing and empowering, at its revolutionary potential, and at the possibility of

Marx’s thinking being informed by a streak of technological determinism (of which more in

week 10).

Main reading

Berg, Maxine, 1980, The Machinery Question and the Making of Political Economy,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, part 1. SLC (MVS/E [Ber])

20

�Other reading

Babbage, Charles, 1835, The Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, 4th edn. [excerpts

available on the web or as photocopy from me]

Babbage, Charles,1989, Science and reform: selected works of Charles Babbage, ed. Anthony

Hyman, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beniger, James R., 1986, The Control Revolution: Technological and Economic Origins of

the Information Society, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press.

Benthall, Jonathan, 1976, The Body Electric: Patterns of Western Industrial Culture, London:

Thames & Hudson.

Carlyle, Thomas, 1829, ‘Signs of the Times’, rtpd. in Carlyle, Selected Writings, ed. Alan

Shelston, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

Clayre, Alasdair, Ed., 1977, Nature and Industrialization, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harvie, Christopher, Graham Martin & Aaron Scharf, Eds., 1970, Industrialisation and

Culture, 1830-1914, London: Macmillan for the Open University Press.

Kennedy, Noah, 1989, The Industrialisation of Intelligence: Mind and Machine in the

Modern Age, London: Unwin Hyman, esp. chs. 2-4. SLC

MacKenzie, Donald, 1984, ‘Marx and the Machine,’ Technology and Culture, 25 (July 1984):

473-502.

Marx, Karl, 1976, Capital, vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes, intr. Ernest Mandel, Harmondsworth:

Penguin, ch. 15.

Pollard, S., 1963, "Factory Discipline in the Industrial Revolution," Economic History

Review, 2nd series, Vol. 16, pp. 254-271.

Ricardo, David, 1821, Principles of Political Economy,3rd edn., in Works and

Correspondence, 11 vols., ed. P. Sraffa, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951, esp.

ch. on machinery.

Ruskin, John, 1857, The Political Economy of Art [any edition]

Thompson, E. P., 1967, "Time, Work Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism," Past and

Present, No. 38, pp. 56-97.

Ure, Andrew, 1835, The Philosophy of Manufactures, rptd. New York: Augustus Kelley,

1967; partially rptd. in Michael Brewster Folsom & Steven D. Lubar, Eds., The Philosophy of

Manufactures: Early Debates over Industrialization in the United States, Cambridge Mass:

MIT Press; excerpt rptd. in Clayre, op. cit.

21

�Essay question

Write a critical appraisal of Marx’s interpretation of the social and historical significance of

technology as fact and concept.

9. Technology, Religion and the Sublime

In many ways technology may look like a secular and even a secularizing

phenomenon. But several accounts suggest that a quasi-religious feeling can quicken in

response to it.

In a crude way one sees this in some of the wilder cyber-prophecies current today: a

techno-destinarianism that envisages our taking our place among the stars, and escaping the

tyranny of the flesh (more of this in the final week). But on a more modest level, even

particular technologies (rather than merely imagined ones) can seem to be touched by grace -not least because they work. The more improbable a technology is, the more its working can

be a source of wonderment -- though of course that wonder can wear thin with overfamiliarity. One sees such wonder in the engineer-philosopher, Friedrich Dessauer’s view of

technology as something like the materialization in our world of ideas from another realm.

Of particular interest to us is the possibility of quasi-religious feeling about

technology having a social function. In this connexion we’ll review David Nye’s case about

the ‘American technological sublime’, which he relates to Durkheim’s view of religion as

having a fundamental role in securing social solidarity and representing a society to itself.

We’ll consider whether this case (which Durkheim applies to tribal societies) can be plausibly

adapted to modern, pluralist and individualist industrial societies, and follow through some if

the implications of the way Nye discusses technology and nature, and the influence of

Romanticism here.

Main reading

Nye, David E., 1994, American Technological Sublime, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, esp.

introduction & chs. 1 & 2. SLC (303.4830973NYE)

Other reading

Davis, Erik, 1999, TechGnosis: myth, magic and mysticism in the age of information,

London: Serpent’s Tail.

Dessauer Friedrich, 1972, ‘Technology in its Proper Sphere’, rptd. in Mitcham, Carl & Robert

Mackey, Eds., Philosophy and Technology: Readings in the Philosophical Problems of

Technology, New York: The Free Press.

Floorman, Samuel C., 1995, The Existential Pleasures of Engineering [1976], London:

Souvenir Press, esp. chs. 10-11.

Kubrick, Stanley, 1968, 2001: A Space Odyssey [film]

Marx, Leo, 1964, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America,

New York: Oxford University Press.

22

�Midgley, Mary, 1992, Science as Salvation: a modern myth and its meaning, London:

Routledge.

Mitcham, Carl & Grote, Jim, Eds., 1984, Theology and Technology: Essays in Christian

Analysis and Exegesis, Lanham: University Press of America.

Mumford, Lewis, 1970, The Myth of the Machine Vol. 2: The Pentagon of Power, New York:

Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich Inc.

Noble, David F., 1998, The Religion of Technology: the divinity of man and the spirit of

invention, New York: Knopf.

Pacey, Arnold, 1983, The Culture of Technology, Cambridge Mass: MIT Press, esp. ch. 5.

Pirsig, Robert, 1974, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, New York: Morrow.

Technology in Society, 1999, Special issue on Science, Technology and the Spiritual Quest,

21 iv .

Wertheim, Margaret, 1999, The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace, London: Virago

Essay question

‘Western technology promises a redemption it cannot deliver.’ Discuss.

10. Technology and History: The Technological Determinism debate

At its simplest technological determinism boils down to the idea that technological

development is the driving force of history. In this uncompromising sense of the term,

there’ve been very few technological determinists. Yet the idea persists. Some adopt a

qualified determinism, some versions of which we’ll consider. Some histories of technology,

by confining themselves to technology, adopt an implicit technological determinism by

default. But there’s also the widespread felt experience of technology as a force visited upon

us from without -- and this the idea of technological determinism does at least express, even

if we find it to be intellectually wanting. The relation (or lack of it) between professional

intellectual opinion and general felt experience is something we’ll need to bear in mind here.

Determinism can also be embraced as destiny (cf. last week’s topic), and is deeply

implicated in authority, control and freedom which, as we’ve seen, are issues that loom large

in modern scientific technology. The perception of determinism also raises the question of

what would count here as free choice, and we’ll consider the issue of individual as against

collective decision-making (something we’ll return to in week 19).

We’ll also consider one of the main alternatives to technological determinism: social

constructivism. We’ll think about different kinds of understandings of technology in relation

to history, and how far, if at all, different kinds of understanding might affect our ability to

make our own history.

23

�Main reading

Smith, Merritt Roe & Leo Marx, Eds., 1994, Does Technology Drive History? The Dilemma

of Technological Determinism, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, esp. Heilbroner’s two chapters.

SLC 303.483 DOE

Other reading

Bijker, Wieber E., Thomas P. Hughes, & Trevor J. Punch, Eds., 1987, The Social

Construction of Technological Systems, Cambridge MA, MIT Press.

Carlisle Y.M. & D.J.Manning, 1999, ‘Ideological Persuasion and Technological

Determinism,’ Technology in Society, 21 (1999): 81-102.

Cook, Scott D.N., 1996, ‘Technological Revolutions and the Gutenberg Myth’ in Stefik,

Mark, Ed., Internet Dreams, Cambridge Mass: MIT Press.

Lemonnier, Pierre, Ed., 1993, Technological Choices: transformation in material choices

since the neolithic, London: Routledge.

Marx, Karl, 1947, The Poverty of Philosophy, Moscow: Progress [or any edition] SLC

Pacey, Arnold, 1983, The Culture of Technology, Cambridge Mass: MIT Press, esp. ch. 2.

Segal, Howard P., 1985, Technological Utopianism in American Culture, Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Staudenmaier, John M., 1985, Technology’s Storytellers: Reweaving the Human Fabric,

Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

White, Lynn, jr., 1962, Medieval Technology and Social Change, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Essay question

‘Technology may not determine history by itself, but we’re prone to making our history (and

our technologies) as if it did.’ Discuss.

11. Biology / Technology

Ethical and other controversies about biotechnology and artificial life are much in the

news at present. But we’re going to go back some way to get to some of the underlying

questions here.

Darwinian evolution poses fundamental challenges. It implies that human life is

explicable in materialist terms, and posits a natural history of such immense scale and

seeming indifference to our conscious sentiments and intentions, as to dwarf human history.

The basic challenge, then, is to the way in which we conceive the human -- a

challenge which swiftly begot the strange and strangely influential doctrines of social

Darwinism. Some of these ideas are swiftly applied to technology -- for example in Samuel

24

�Butler’s Erewhon (= Nowhere backwards) novels, which imagine machines competitively

out-evolving their human creators.

On the one hand this is another manifestation of the recurrent theme of technology out

of control -- and one still with us. But on the other hand, if evolutionary natural history is

really what we have to get some purchase on in order to regain control, then technology may

look like the best bet for defying fate. One manifestation of this is the widespread (and

pseudo-scientific) invocation of race, and of racial groups as collective political entities. It’s

almost an obsession from the late nineteenth century onwards, and begets various eugenic

schemes, by which we’ll gain technological command of our biological destiny. This

culminates in the obscenity of the Final Solution, which should give us pause for thought,

before proceeding to probe the political implications of more recent bio-technology,

especially based on genetics. Among the other questions to ponder here is the problem of

being at home in the world, since Darwin posits life processes as in some ways quite alien to

the worlds of consciousness in which we seek to live; the problems of defining life or

humanity, especially in opposition to mechanism or artifice; and some awkward questions

thrown up by the attempt to use a kind of techno-politics to get a directing grip on history and

biology.

Main reading

Mazlish, Bruce, 1993, The Fourth Discontinuity: The Co-Evolution of Human and Machines,

New Haven: Yale University Press, chs. 10-11. SLC (303.483MAZ)

Other reading

Agamben, Giorgio, 1998, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel HellerRoazen, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Ansell Pearson, Keith, 1997, Viroid Life: Perspectives on Nietzsche and the Transhuman

Condition, London: Routledge.

Arendt, Hannah, 1966, The Origins of Totalitarianism, London: Allen & Unwin

Bauman, Zygmunt, 1989, Modernity and the Holocaust, Cambridge: Polity.

Brodwin, Paul E., Ed., 2000, Biotechnology and Culture: bodies, anxieties, ethics,

Bloomington: Indiana UP.

Bud, Robert, 1994, The Uses of Life: a history of biotechnology, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Butler, Samuel, 1872, Erewhon [any edition — and also available on the internet]

Caudill, Maureen, 1992, In Our Own Image: Building an Artificial Person, New York:

Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, Richard, 1988 , The Blind Watchmaker, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Dyson, George B., 1997, Darwin among the Machines, London: Addison-Wesley.

25

�Emmeche, Claus, 1994, The Garden in the Machine: The Emerging Science of Artificial Life,

trans. Steven Sampson, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kelly, Kevin, 1994, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, London: Fourth Estate.

Sharp, Margaret, 1985, The New Biotechnology: European Governments in Search of a

Strategy, Brighton: Science Policy Research Unit, University of Sussex..

Shiva, Vandana & Inguna Moser, Eds., 1995, Biopolitics: a feminist and ecological reader on

biotechnology, Atlantic Heights NJ: Zed Books.

Walgate, Robert, 1990, Miracle or Menace: Biotechnology and the Third World, London:

Panos.

Ward, Mark, 1999, Virtual Organisms, London: Macmillan.

Essay question

Do our current concept of biology, and techniques and technologies for intervening in it, pose

inherently political problems?

12. Philosophy / technology

Heidegger can be seen as a critic of technology alongside Mumford and Ellul, whom

we’ll be looking at later. The reason for tackling him here by himself is partly convenience,

in that his key work on technology, ‘The Question Concerning Technology’ happens to so

compactly suggestive as to warrant and make possible our close reading of it.

His thinking on technology presents some sophisticated terms, especially in the

context of his philosophy in general, for thinking about fundamental issues: the relation in

which we stand to the world and the world conceived as a kind of reserve store for our

projects, technologies as a kind of revealing (cf. Dessauer, whom we encountered in week 9),

among others.

However, besides attending to what he has to say, we’ll also want to consider the

position from which Heidegger speaks. His own cultural and political life poses some

awkward questions. His values are partly informed by a very German ideal of the smalltown, organic community, and a correspondingly ambivalent response to modernity. Yet

certain kinds of organicism and reactions against modernity also informed Nazism, even

though it was in other respects very high-tech. and self-consciously modern, and Heidegger

was at the very least a Nazi fellow-traveller for a time. The unsatisfactory silence he

maintained on this score, we can perhaps pass over. More relevant for our purposes is the

larger issue posed by contextual reading of Heidegger on technology of finding a place on

which to stand and from which to speak in relation to technology.

Main reading

Heidegger, Martin, The Question Concerning Technology in Heidegger, Martin, 1993, Basic

Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell, London: Routledge. SLC (193HEI)

[If this seems overfacing, look instead at Pattison’s introductory account -- reference below]

26

�Other reading

Arendt, Hannah, 1958, The Human Condition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Borgmann, Albert, 1987, ‘The Question of Heidegger and Technology: A Critical Review of

the Literature,’ Philosophy Today, 31 no.2 (Summer 1987): 98-194.

Dusek, Val & Robert Scharff, Eds., 2002, Philosophy of Technology: The Technological

Condition: an Anthology, Oxford: Blackwell.

Feenberg, Andrew, 1995, Alternative Modernity: The Technical Turn in Philosophy and

Social Theory, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gehlen, Arnold, 1980, Man in the Age of Technology, trans. Patricia Lipsomb, New York:

Columbia University Press [store]

Herf, Jeffrey, 1984, Reactionary Modernism: technology, culture and politics in Weimar and

the Third Reich, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mitcham, Carl & Robert Mackey, Eds., 1983, Philosophy and Technology: Readings in the

Philosophical Problems of Technology, New York: The Free Press.

Pattison, George, 2000, The Routledge Philosophy Guide to the Later Heidegger, London:

Routledge.

Rapp, Friedrich, 1981, Analytical Philosophy of Technology, trans. Stanley Carpenter &

Theodor Lagenbruch, Boston: D. Reidel.

Simpson, Lorenzo C., 1995, Technology, Time and the Cinversations of Modernity, New

York: Routledge.

Thiele, Leslie Paul, 1995, Timely Meditations: Martin Heidegger and Postmodern Politics,

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wolin, Richard, 1990, The Politics of Being: the political thought of Martin Heidegger, New

York: Columbia University Press.

Zimmerman, Michael, 1990, Heidegger’s Confrontation with Modernity: Technology,

Politics, Art, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Essay question

How, for Heidegger, does our technology shape our perception of and engagement with the

world?

27

�13. Political Machinery

This session develops issues we broached in thinking about control systems and

political economy in week 8, where we considered some of the ways in which local, relatively

discrete systems of governance ran into difficulties to which the answer often seemed to be

more elaborate, systematic, interconnected systems of governance.

For if the phrase ‘government machine’ is a metaphor, it’s a metaphor in which it’s

hard to tell where the metaphor ends and reality takes over. For governance has come to

deploy more technologies for administration, while its bureaucrats in the view of Weber and

others came to function as a kind of human machine -- even before computerization.

We’ll reflect upon particular political technologies, such as electronic voting, systems

of surveillance, and information systems, and enquire how far these have changed or might

change the character of political processes. We’ll also consider cybernetics (which shares its

etymology with ‘governor’) as an attempt to see biological, mechanical and political control

and feedback processes in similar terms.

Main reading

Winner, Langdon, 1977, Autonomous Technology: Technics-out-of-control as a Theme in

Political Thought, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, ch. 6. SLC (303.483WIN)

Other reading

Achterhuis, Hans, Ed., 2001, American Philosophy of Technology: the empirical turn, trans.

Robert P, Crease, Bloomington: Indiana UP. [chapter on Winner]

Ackroyd, Carol, Karen Margolis, Jonathan Rosenhead & Tim Shallice, 1977, The Technology

of Political Control, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Barker, Benjamin R., 1998-9, ‘Three Scenarios for the Future of Technology and Strong

Democracy,’ Political Science Quarterly, 113 iv: 573-89.

Brown, David, 1998, Cybertrends: Chaos, Power, and Accountability in the Information Age

[1997], Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Burnham, D., 1983, The Rise of the Computer State, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Deutsch, Karl W., 1966, Nerves of Government: Models of Political Communication and

Control, New York: The Free Press.

Diffie, Whitfield & Landau, Susan, 1999, Privacy on the Line: The Politics of Wiretapping

and Encryption, Cambridge Mass: MIT Press, 1999.

Gosling, William, 1994, Helmsmen and Heroes: Control Theory as a Key to Past and Future,

London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Gray, Chris Hables, Ed., 1995, The Cyborg Handbook, New York: Routledge.

28

�Gray, Chris Hables, 2001, Cyborg Citizen: Politics in the Post-human Age, London:

Routledge.

Hill, K. & Hughes, J, 1998, Cyberpolitics: Citizen Activism in the Age of the Internet,

Maryland: Rowan and Littlefield

Loader, Brian D., 1997, The Governance of Cyberspace, London: Routledge.

——, 1999, Digital Democracy, London: Routledge.

Lyon, David, 1993, The Electronic Eye: The rise of the surveillance society, Oxford:

Blackwell.

Schone, Richard, 1995, Democracy and Technology, Cambridge Mass: MIT Press.

Weber, Max, 1948, ‘Bureaucracy’ in From Max Weber, ed. H.H.Gerth and C. Wright Mills,

London: Routledge.

Wiener, Norbert, 1968, The Human Use of Human Beings: cybernetics and society [1950],

London: Sphere Books.

Essay question

Discuss the problems and opportunities presented by technologized forms of politics.

14. The Private Life of Machines

After the abstract and political concerns of the last few weeks, we come this week to

the intimate life of technologies -- or, rather, our intimate life with them. How do we interact

with technologies in daily life? How do we establish a sense of possession of them? How are

we encouraged to adopt technologies? What ideological baggage or constraints do they come

with?

Giedion’s book, from which the main reading comes, is fascinating and compendious.

I’ve asked you to have a look at the material on the household -- but if you have time do also

have a look at the material on the bath -- one of the most intimate ways in which we use

technology.

One of our concerns here is with the incorporation of technological systems and their

networks into felt cultural normality -- as, for example, in the way in which our often almost

visceral sense of acceptable standards of personal hygiene is structurally dependent upon

complex networks of fuel, machine production, plumbing and sewerage.

There are also questions of power involved -- as feminists point out in relation to

domestic technologies, which may promise liberation, but which (some argue) deliver a

different kind of bondage. But these technologies are also implicated in one of the most

striking social changes of the last hundred years: the decimation of the servant-class, which

has a host of political and other implications.

We’ll glance also at Gifford’s history of the way habitual perceptions (of, e.g.,

distance and space) have changed over the past two centuries, and then seek to locate these

intimate technologies in relation to terms proposed by Don Ihde and Albert Borgmann,

29

�respectively, for thinking about different kinds of technology and different ways of engaging

with them.

Main reading

Giedion, Siegfried, 1969, Mechanization Takes Command: a contribution to anonymous

history [1948], New York: W.W.Norton & Co, part VI, esp. ‘Mechanization Enters the

Household’. SLC 609 GIE

Other reading

Achterhuis, Hans, Ed., 2001, American Philosophy of Technology: the empirical turn, trans.

Robert P, Crease, Bloomington: Indiana UP. [includes chapters on Borgmann & Ihde]

Borgmann, Albert, 1984, Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life, Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Cowan, Ruth S., 1989, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technologies from

the Open Hearth to the Microwave, rev. edn., London: Free Association Books

Gifford, Don, 1990, The Farther Shore: A Natural History of Perception 1798-1984, London:

Faber and Faber.

Higgs, Eric, Andrew Light & David Strong, Eds., 2000, Technology and the Good Life?

Chicago: U of Chicago P. [essays on Albert Borgmann]

Ihde, Don, 1990, Technology and The Lifeworld: From Garden to Earth, Bloomington:

Indiana University Press.

Jackson, Stevii & Shaun Moores, Eds., 1995, The Politics of Domestic Consumption: Critical

Readings, London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Lie, Merete & Knut H. Sorensen, Eds., 1996, Making Technology Our Own? Domesticating

Technology into Everyday Life, Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

Martin, Michèle, 1991, ‘Hello Central? Gender, Technology and Culture in the formation of

telephone systems, Montreal: McGill / Queen’s University Press. [also relevant to weeks 15 &

20].

Wosk, Julie, 1992, Breaking Frame: Technology and the Visual Arts in the Nineteenth

Century, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Essay question

‘The technologies that most affect us are the ones we use so intimately and routinely that we

no longer attend to their technological constructedness.’ Discuss.

30

�15. Technology and work: Taylorism and its aftermath

In looking at the political economy of machines (week 8) we saw the advent of the

factory, with its special control and management systems, and with some industrialists

already speaking of the workers as human components of the machinery. We’re concerned

here in the first instance with the development of these in ‘scientific management’. Tasks are

carefully broken down into simple elements, and the worker is carefully drilled in one of

these. Time and motion studies optimize performance. It’s something Chaplin satirizes in

Modern Times -- especially in showing the worker actually being dragged into the machinery:

a telling metaphor for what’s going on here.

Apart from the obvious questions of whose interests are being served, and of whether

these seemingly technical questions are not properly political, there’s a larger context here of

the ‘social engineering’ movement and of ‘technocracy’ to which its related. It’s strong in the

US which goes at disorientating speed from pastoral to industrial society, and whose various

social ills are responded to by some with a strong impulse to impose rational, grid-like order

on life.

We’ll consider some of the ideological issues at stake, before looking to recent

transformations of work, especially in relation to the renewed attempts to get people to

identify with the machines they use, and the possible value of this in terms of social discipline

or productivity.

Main reading

Doray, Bernard, 1988, From Taylorism to Fordism: A Rational Madness [1981], trans. David