Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 229

10

PEACEMAKING

Perceptions and practices in

the medieval Latin East

Yvonne Friedman

The prevailing perception of the 1096 to 1291 era as one of Holy War, with peace

far removed from the adversaries’ thoughts, is not entirely accurate. In fact, this

epoch of Holy War was punctuated by interludes of peace, as indicated by the

approximately 120 treaties mentioned in the historical sources. Although crusader

society in the East and its diverse Muslim enemies never achieved a lasting peace,

the intermittent ceasefires or treaties reached over this period enabled a fragile

cohabitation that endured for two centuries. The entry into such agreements

required bridging differing conceptions of peace and the lack of shared language

and peacemaking mechanisms.

I begin by examining the disparate conceptions of peace in Muslim and crusader

society. I then consider the factors that encouraged or discouraged the parties

involved from engaging in negotiations for a ceasefire or peace treaty and the

influence of the shifting balance of power on peace initiatives. Finally, I address issues

of mutual acculturation in the stages of peacemaking: how the sides developed a

shared verbal and nonverbal language of peacemaking contacts in the arena of the

Latin East, as implemented through diplomacy, gesture and formal agreements.

Peace was an ideal goal in both medieval Islamic and Western Christian

thought. The aspiration to world peace, however, did not contradict the concept

or practice of using military force against antagonists. Conceived of in Islam as

resulting from a definitive victory that would bring a just solution to current

situations, peace was therefore based on just war. In Christianity, peace was an

inherent part of an eschatological vision of the world. Yet, both Islam and Western

Christianity founded institutions aimed at the destruction of their enemies – in

Islam, the jihad; and in Christianity, the crusade – thus making war a religious

imperative. Both medieval societies, however, displayed a dichotomy between

ideology and practice with respect to war and peace. It was the loopholes between

the two that allowed for peace processes.

Muslim law differentiates between intra-Muslim peace, sulh, which could

only be contracted between Muslim factions, and muhadana, a temporary

1

2

3

4

511

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

229

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 230

YVONNE FRIEDMAN

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

ceasefire–peace with the infidel entered into only for reasons of expediency.

Although jihad is obligatory, its status as a collective, not a personal, obligation

allows for many exceptions and facilitates utilization of loopholes to make peace.

In Islam, war against the infidel needed no justification, whereas peace or even

truce-making required both pretext and explanation. In his chapter on jihad, alTabari outlined the basic terms:

Al-Awza´i said: If Muslims conclude a peace treaty with the enemy [darb

al-harb] in which they agree to pay Muslims a designated amount [of

money] every year so that the Muslims will not enter their country, there

is no harm in concluding such a treaty with them.

Al-Shafi´i said: I would like for the Imam, if a great misfortune were

to happen to the Muslims, and I hope God will not allow this [to

happen] to them, to consider a peace treaty with the enemy, whoever

they are, and he should conduct a peace [treaty] with [the enemy] only

up to a certain time . . . And if the Muslims have power, he should fight

the polytheists after the peace expires. If the imam does not have the

power, there is no harm to renew [the agreement] for the same duration

or less, but he should not exceed the [time limit for the first one].1

Later medieval Islamic legal thought was preoccupied with the circumstances and

conditions under which it was permissible to contract a truce. Ibn Rushd

(Averroes), for example, submitted:

The conclusion of truce is considered by some to be permitted from the

very outset and without an immediate occasion, provided that the Imam

deems it in the interest of the Muslims. Others maintain that it is only

allowed when the Muslims are pressed by sheer necessity, such as civil

war and the like. As a condition for truce, it may be stipulated that the

enemy pay a certain amount of money to the Muslims . . . Such a

stipulation (paying of tribute) however, is not obligatory.2

Thus, whereas peace treaties were seen as a necessary evil and had to be temporary,

they were clearly permissible. Practical willingness to limit warfare and enter into

treaties emerged from centuries of Muslim warfare and diplomatic relations with

the Byzantines, leading to the development of an intricate web of means of

coexistence, which included institutions like aman,3 captive exchanges4 and

formal diplomacy.5 Although still idealizing war as the normative relationship with

the infidel, medieval Islam had in fact honed the tools with which to make peace.

Bonner describes the relations on the tughur (frontier) as fostering centres for

embattled scholars, but at the same time depicts the abode of those embattled

scholars – the ribats on the Eastern frontiers – as centres ‘that became devoted to

the arts of peace’.6 The encounter with the crusaders led to an intensification of

the ideal of jihad, as for example in the writing of al-Sulami. But even in his

230

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 231

PEACEMEKING

treatise on jihad, he did not change the basic rules and thus treaties remained a

practical possibility.7

The conditions of treaty-making encompassed almost all possible scenarios: (1)

from a position of strength either to avoid further bloodshed or, occasionally, to

buy time to acquire reinforcements and supplies; (2) from a position of parity in

order to settle differences when combat was not desirable; and (3) from a position

of weakness in order to make the best of an adverse situation and perhaps gain time

for readjustment.8 During the eighth to tenth century, the Byzantine and Abbasid

empires often used captive exchanges as an opening and pretext for truce-making.

Nor were these endeavours limited to relations with Eastern Christendom alone.

In the twelfth century there were other Muslim–Christian encounters besides the

crusades, many of which ended or were regulated by treaty. These ranged from

military settlements, including a tributary status in Spain, to commercial treaties

with Mediterranean powers.9 Although all the Muslim legalists emphasized the

temporary nature of these agreements, they still spelled out the conditions and

tools of peacemaking.

Western Christianity also demonstrated a dichotomy between ideology and

practice with respect to war and peace, but its starting point was diametrically

opposed to that of Islam. As noted, peace was a religious goal, part of an

eschatological programme for the world. It belonged to Christian ritual and, in

Augustine’s eyes, was one of the aims of the City of God.10 Medieval Christian

ideological adherence to peace, and limitation of warfare, was exemplified by the

‘Peace of God’ movement, organized and hailed by the Church. The medieval

Western notion of peace encompassed Christians alone, viewing war against the

infidel – the crusade – as another facet of peace, if not a prerequisite for it.11 The

Church’s peace councils gave it the authority to decide who could deploy arms,

for what purpose, at whose command, against whom, and when. But at the same

time this development suggested that, under certain conditions, the Church now

regarded violence as licit.12 Seeing crusade as the logical outcome of the Peace of

God movement, Mastnak concluded that Urban II was a peacemaking pope, a

lukewarm Gregorian reformer who waged a holy war.13 Thus, crusade could be

seen as an act of love in Christian eyes,14 and the preaching of this act of love

included the rallying of forces to a war of extermination against the infidel enemy,

employing concepts like purging and cleansing the holy places. 15 Although the

Church preached peace, the practical outcome was war.

In principle, the Holy War against the infidel allowed for no mercy for the

vanquished enemy. The preachers described a situation of victory or death.16 As

they did not expect any mercy from their enemy, the crusaders saw no reason to

show them mercy. Christian chroniclers described with proud relish bloody

victories that included butchering and looting the defeated.17

On the other hand, Western Christianity had a long tradition of internal

peacemaking by treaties and of conflict resolution accompanied by ceremonial

gestures, such as satisfactio and deditio.18 Therefore, in facing actual problems of

peacemaking – accepting the capitulation of a besieged city, signing a ceasefire

1

2

3

4

511

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

231

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 232

YVONNE FRIEDMAN

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

with a city willing to pay tribute to be left in peace, and so on – the crusaders did

not encounter a totally unknown situation. Although, ideologically, they saw no

need to make peace with the enemy, when they found it profitable to do so, they

had in store an arsenal of rituals and usages that had developed in Europe for intraChristian peace and conflict resolution. Thus, to some extent, like their Muslim

foes, the peace-loving Christians felt there was no need to explain the Holy War

called by the pope; it was peace that needed a pretext and rationalization.

However, in contrast to the Muslim world, for Christianity, it was the idea of Holy

War that was new and placed the crusaders in a position in which peacemaking

with the infidel was not seen as an option, whereas the notions of peace and of

the need for treaty-making were well known.

In addressing the question of treaty-making under such circumstances we must

remember that the leaders of the First Crusade were not just charged with

religious zeal to free the Holy Land from what they saw as its unlawful inhabitants;

they were also down-to-earth military leaders governed by realistic strategic

considerations. Therefore, when approached by an enemy willing to surrender

under favourable conditions, or proposing a pact that might seem expedient or as

forwarding their main goal, it seems that the crusaders’ problem was not so much

one of overcoming religious or ideological qualms but one of language – cultural

language. The main difficulty was to find a mechanism acceptable to both cultures

to ensure that both sides would trust and keep an agreement. Not just military,

the Muslim–Christian encounter has been rightly defined as one of negotiating

cultures.19 It is the story of these negotiations, in sharp contrast to their hostile

ideology, which I seek to tell here.

The starting point for consideration of the details of the peacemaking processes

is naturally the agreements themselves, their number, dates and terms. Using

mainly Arabic sources, T. Nakamura charted a list of seventy-two treaties between

1097 and 1145, a period in which the Franks were dominant, ending with their

first serious territorial loss, the fall of Edessa.20 More recently, my student Shmuel

Nussbaum examined the Latin and French sources in addition and arrived at a

table of 109 treaties in the 1097 to 1291 period.21 Although there is a large degree

of overlap, by combining both tables and consulting the sources, I arrived at an

approximate total of 120 treaties over the two-century period, but with negotiations failing in 11 cases, the final total is 109. The calculation is problematic,

because treaties were often renewed and thus the same treaty is counted twice; on

the other hand, sometimes negotiations failed and did not in fact end in

agreement, although the sources may describe the stages as if they were part of a

treaty. But even if the number of treaties is not sufficiently exact for statistical

analysis, it suffices for a general impression of the balance of power and to prove

that, notwithstanding ideologies of crusade and jihad, treaties were a regular

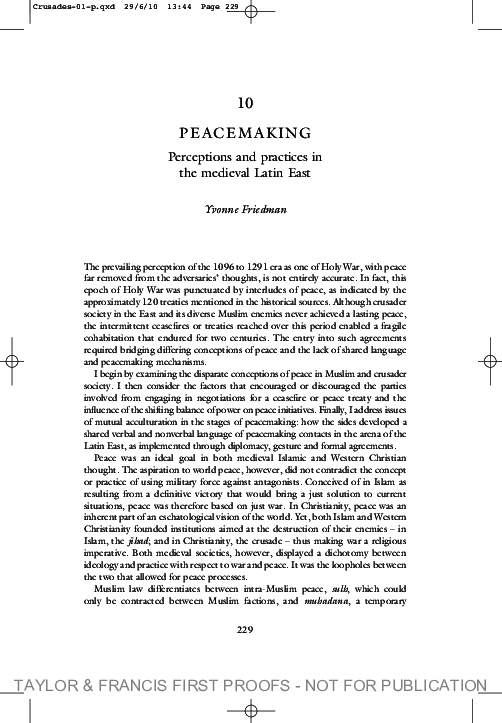

phenomenon in the Latin East. Figure 10.1 shows the balance of power that

emerges from comparison of the percentage of initiatives for peace as described

in the literary sources, based on Nussbaum’s findings.

232

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 233

PEACEMEKING

90

Muslim initiatives

80

Crusaders/Franks

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

1098–1124

1127–1192

1193–1250

1252–1290

Periods

Figure 10.1 The pattern of initiative-taking in peace treaties between Muslims and

Christians, 1098–1290

Note: Treaties where the sources do not specify who asked for peace are not included.

1098–1124

During the first two decades of the principality of Antioch’s history (1098–1128)

the Muslim powers were forced to cultivate a generally submissive and conciliatory

relationship with the Franks. The treaties reached included clauses setting tribute

payments to the Christians and were, according to Tom Asbridge, built on the

eleventh-century Iberian precedent of the so-called Taifa states and their tributary

status, known to at least some of the crusaders.22 For the Muslim side, this

situation was familiar from its relations with the Byzantine Empire. Asbridge sees

the difference in willingness to make peace not just as one of political power, but

of general outlook:

It is worth noting that the Latins of Antioch did not share their neighbours’ willingness to negotiate or purchase peace in times of crisis. When

the principality faced disaster in 1105 or 1119, the Franks did not appear

to have even tried to negotiate, relying instead upon military force,

risking battle even when they lacked resources and manpower.23

1

2

3

4

511

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

233

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 234

YVONNE FRIEDMAN

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

But when the Muslim side showed willingness to submit to crusader rule, this was

usually accepted, notwithstanding the ideal of total war. As the balance of power

during the first decade of the Latin kingdom and the Syrian principalities was

usually in favour of the Franks, treaties, both of tribute and condominium, were

signed and implemented.

Thus, during this period of overwhelming crusader superiority over the Muslim

principalities, we find a minority of Frankish requests for agreements with the

Muslims, only 15 per cent of a total of 33 requests attested in the literature, as

opposed to Muslim initiation of 46 per cent of the agreements.24

1127–92

With the unification of Syria under Zengi, Nur al-Din and Saladin, the religious

slogan of jihad was used as a power-enhancing mechanism to forward their

political aims. The gradual unification of Muslim territories, the fall of Edessa in

1144, and the ascendancy of jihad have been identified as points of decline on the

Christian side.25 This period saw a shift in the balance of power from crusader

superiority until its great defeat at Hattin. The Franks now had to learn to accept

that the shoe could be on the other foot. By then, though, a process of acculturation had taught them to accept elements of Eastern usage, and, when

necessary, to ask for peace. It is, however, illuminating to note William of Tyre’s

negative reaction to the signing of a treaty placing them on an equal footing with

their adversary, Saladin, in 1180, seven years before the great disaster at the Battle

of Hattin: ‘The conditions were somewhat humiliating to us, for the truce was

concluded on equal terms, with no reservations of importance on our part, a thing

which is said never to have happened before.’26

The Frankish historian and diplomat thought it permissible to make peace only

when the Franks were the victors and found a status of equality humiliating.

However, it seems inconceivable that the Franks had never been in a situation of

equality, not to mention inferiority, before 1180. That such a shift in diplomatic

balance is documented only at a rather late date may stem from the Muslim side’s

ideological preference for demonstrating its need for a truce even when it was in

fact not the weaker party. At the time Saladin’s propagandists depicted him as a

leader who was pursuing jihad and was not making truces from a position of

weakness; their explanation was that in this case he had economic motivations for

agreeing to a truce. The historian and diplomat William of Tyre saw this shift in

diplomatic protocol as a watershed, as marking a new period.

During this period, enhanced Muslim military strength, due to unification under

the leadership of Zengi, Nur al-Din and Saladin, is reflected in a reduction of the

number of Muslim-initiated requests for agreements from 46 per cent in the

previous period to 35 per cent.27 Note, however, that Saladin in fact fought more

intra-Muslim wars to enhance his own rule in Egypt and Syria than jihad against

the Franks, and it was his great victories at Hattin and Jerusalem that enabled his

propagandists to paint him as the ideal Muslim ruler fighting only for the faith.28

234

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 235

PEACEMEKING

1193–1250

For the third period, during which the Franks ruled the coastal region and the

Muslims ruled the internal region of the Holy Land, the balance of power was

largely determined by shifts in internal Ayyubid politics and crusader attempts at

incursion on Ayyubid lands, strengthened by crusades from the West.29 The tiny

crusader kingdom did occasionally succeed in obtaining additional territory by

treaty (especially from 1129 to 1144), but modern historians usually depict them

as clearly inferior to the Ayyubids. The balanced number of peace-agreementinitiating requests seems to point to military parity,30 or a balance of diplomatic

power that enabled the Franks to appear stronger than they were in reality. In

general, both this and the preceding period were characterized by a relatively even

number of ceasefire initiatives.

1252–90

During the period of the Mamluk sultanate, when the Muslims achieved

ascendancy, and before the final defeat of the Latin kingdom, we find cynical use

of agreements to push the Franks out of the Latin East. The overriding consideration was what would bring greater benefit: war or peace? Note, however,

that the religious definition of muhadana made designation of practical needs an

integral part of treaty formulation. The Muslim leader, even when he was the

stronger party, would explicitly state the necessity that permitted him to seek

peace, a convention the triumphant Baybars included in his treaties. During

Baybars’ reign, when the Franks had to ask for peace time and again and were

granted at most an unstable ceasefire, the diplomatic tone emphasized the inferior

status of the Franks both in terms of territory and in terms of initiating and paying

for the ceasefire. But even then it was necessary to mention the fidah – the return

of captives by the Franks – because exchange or ransoming of captives was one of

the legally accepted pretexts to end war.31 This period saw the highest proportion

of Frankish-initiated requests for ceasefires: 77 per cent of a total of 26 requests.32

This periodization of the two-century-long series of negotiations between

Muslims and Franks is naturally arbitrary. In his book on crusader castles, which

focuses on military encounters, Ronnie Ellenblum suggests a different scheme.

Based on the frequency of hostilities, he divides the twelfth century into three

stages: 1099–1115, 1115–67 and 1167–87.33 He sees the second period as one

of Frankish military superiority over their Muslim neighbours, and accordingly as

a period of relative security for the Franks. His third period includes the

unification of Muslim forces under Nur al-Din and Saladin and the subsequent

deterioration in Frankish security and, following William, 1180–7 is considered a

sub-period, one of constant pressure by Saladin on the Franks until their defeat at

Hattin.34 Taking the treaties and peace negotiations as the criterion for periodization, one arrives at comparable but not similar results. As we have seen, William

of Tyre, who was contemporary to the treaty of 1180 and well aware of the

1

2

3

4

511

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

235

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 236

YVONNE FRIEDMAN

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

military pressure Ellenblum sees as a watershed, still found equality in treaty

negotiations to be novel and humiliating. He could not prophesy the fall at

Hattin, but still ended his book on a gloomy note, expressing fear for the future.35

He clearly did not see the 1167–80 period as one of inferior Frankish status.

But whatever scheme one adopts, the data clearly demonstrate a correlation

between military–political shifts in the balance of power and requests for ceasefires

with the underdog generally seeking cessation of hostilities. Whereas the first and

last periods’ results are as expected, the state of near equilibrium characterizing

the two middle periods does not seem to fit the modern evaluation of the balance

of power. With hindsight, the second period is usually seen as one of sharp decline

on the Frankish side, and the third period as one of clear Muslim supremacy.

Apparently, in contemporary eyes, the picture was different or perhaps was

portrayed differently for religious or ideological reasons. Because Muslim ideology

accepted a truce only when absolutely necessary,36 the Muslims employed formal

wording that placed them as the underdog long after they were in fact equal to,

or even stronger than, the Franks. This might explain the discrepancy between the

balance of power in the second half of the twelfth century as perceived by modern

historians and as reflected by William of Tyre and statistical analysis.

The political significance of who initiates the request for peace negotiations is

emphasized by Baha al-Din’s description of the negotiations between Richard

the Lionheart and Saladin’s representatives in 1192. According to the chronicler,

the Muslim mediator al-Adil made a point of noting: ‘We did not make any

request of you. It was you who asked us,’37 thereby marking the inferiority of the

Latin side.

Comparison of the treaties over the whole period points to some changes in the

way agreements were reached over the course of the two-century period of

coexistence. If initial contacts were characterized by oral agreements between the

sides regarding surrender or lifting of a siege for monetary recompense, often

emphasizing the gestures involved, towards the end of the period we find the sides

drawing up formal written agreements, with fixed clauses defining the obligations

assumed by each. As written treaties are sometimes mentioned during the earlier

period too, they must have existed, even if they have not survived. But, more

plausibly, the extant treaties from the thirteenth century prove that by then a mutual

language had been agreed and a common diplomatic protocol had emerged.38

Analysis of the treaties mentioned in literary sources also enables elicitation of

the underlying reasons for initiation of ceasefire agreements, revealing that military

issues were most prevalent. Other factors promoting Muslim–Frankish agreements were: the need for military cooperation in the face of some common

enemy;39 renewal of expired agreements; economic or internal difficulties, such as

lack of rainfall, the low level of the Nile, or the weakening of the regime by

opposition forces; or, simply, the realization that no advantage would ensue from

further conflict.40 Not surprisingly, a greater number of treaties is attested both

for periods in which one side showed marked superiority and for periods of

intensive warfare, making the renewal or signing of treaties a necessity.

236

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 237

PEACEMEKING

Muslim willingness to enter into agreements was largely conditioned by the

pragmatic or political needs of the rulers. In the early period, individual leaders

of the local principalities acted in their own best interests, as seen from what

reportedly motivated Shams al-Khilafa, the governor of Ascalon, who made a

truce with Baldwin I in 1111: his being ‘more desirous of trading than of fighting

and inclined to peaceful and friendly relations and the securing of the safety of

travellers’.41 But whereas in Muslim sources this was viewed as a valid and even

honourable pretext, William of Tyre felt that ceasing fighting for economic

reasons indicated greed, and he castigated Amalric for his readiness to negotiate

a treaty after the conquest of Bilbeis in 1169 because of the large tribute the

Egyptians offered.42 However, this does not mean that the chronicler was unaware

of the economic advantages of peace. In another famous diatribe William

lamented the end of peace with Egypt:

From a quiet state of peace [quieto et tranquillo penitus status] into what

turbulent and anxious condition has an immoderate desire for possessions plunged us! All the resources of Egypt and its immense wealth

served our needs; the frontiers of our realm were safe on that side; there

was no enemy to be feared on the south. The sea afforded a safe and

peaceful passage to those wishing to come to us. Our people could enter

the territories of Egypt without fear and carry on commerce and trade

under advantageous conditions. On their part, the Egyptians brought to

the realm foreign riches and strange commodities unknown to us, were

at once an advantage and an honour to us.43

Although William admitted that peace had its sunnier sides, for him war was the

honourable task of a chivalrous, fighting society. Nonetheless, even these fighting

societies engaged in peaceful contacts, as we have seen. Notwithstanding the use

of jihad to forward political aims under Zengi, Nur al-Din and Saladin, the

Ayyubid period (the third period in Table 10.1) saw many peaceful contacts with

the Franks. 44 During the Mamluk period, however, we witness almost cynical use

of agreements to push the Franks out of the Latin East. Although we have charted

the shifting balance of power and changed historical circumstances in the Latin

East as underlying the conventions of treaty-making, note that initiating negotiations is not always a clear-cut sign of objective military inferiority on the local

scene, and that the global political situation, the real reason behind a diplomatic

move, sometimes receives no mention in the treaty itself.

Thus, for example, as Kedar has recently shown,45 Ayyubid willingness to

extend the treaty with the Latin kingdom in 1204 and to cede Kafr Kanna and

Nazareth to the Franks did not stem from the balance of power in the Holy Land

itself, but rather from the rumours that had reached the East about the preparations for the Fourth Crusade in the West. It may well have seemed expedient for

the Muslim side to make concessions to the Franks in order to prolong the

ceasefire; concessions which perhaps later proved unnecessary.46 Thus the Fourth

1

2

3

4

511

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

237

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 238

YVONNE FRIEDMAN

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

Crusade impacted on the balance of power in the Holy Land even though most

of its crusaders never landed in Acre.47

Similarly, Ibn Wasil’s explanation that the Egyptian sultan al-Kamil had to cede

Jerusalem to Christian rule in 1229 because he had promised it to Frederick II

perhaps sounds like a shallow excuse for a move that seemed irrational to local

Muslims in light of the imbalance between Frederick’s small military presence (and

dwindling local backing) and Ayyubid resources.48 But to a Muslim leader, aware

of the danger of Khwarizmian intervention in Syria and the Holy Land, as well as

the still unstable division of the Ayyubid Empire between Saladin’s heirs, a treaty

with the greatest lay power in Christendom might not have seemed so outlandish.49 The emperor’s naval superiority, grounded in the backing of the Sicilian

navy, was not apparent on the local scene, but it was evident to an Egypt-based

sultan who well remembered the Latin conquest of Damietta a decade earlier.50

The global balance of power may well have been the reason why the treaty, which

was condemned by both Christian and Muslim contemporary chroniclers because

of its religious connotations, was kept for its whole ten-year duration, despite the

criticism voiced in both camps.

To this point, we have looked at peacemaking efforts through the prism of the

shifting balance of power between the adversaries over the two-century period of

Holy War in the Latin East and the impact of economic and political factors, both

local and international. It remains to examine the verbal and nonverbal means the

parties to the conflict employed to bridge their cultural differences and reach

agreements.

Diplomacy

Note, at the outset, the differing conceptions in the Muslim and Christian camps.

For the Muslims, negotiations were usually carried out by sending delegates to

the enemy camp. For the Christians, the accepted mode of negotiating peace often

took place at the highest levels, between the leaders themselves.51 The need to

overcome the cultural gap between the parties enhanced the culture-bridging

role played by diplomats, and the emergence of a class of diplomats with special

privileges and safeguards comprises an important aspect of peacemaking in the

Latin East. From the first encounters between the enemies, and until their conclusion, emissaries played a prominent part in preventing hostilities and achieving

agreements. The initiation of negotiations by sending delegates to the enemy

camp presupposed a state of immunity, like the Muslim aman. This safe-conduct

was essential, and although it could often be a risky business to bring tidings or

offers to the other side, the envoys usually returned to their own camp unscathed.

In the initial stages of drawing up an agreement, emissaries from each side

engaged in preparatory talks, whose outcome often depended on their talents. In

this case, too, there existed longstanding traditions of polyglot, skilled diplomats

passing between the Muslim and Christian camps, some of them former captives,

who learned the language and mores of the antagonist while in captivity; these

238

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 239

PEACEMEKING

could be either Christians or Muslims, depending on the circumstances. In the

East emissaries were usually chosen from among persons with connections to the

ruling elite, at times even members of the royal family. Thus the mediator became

a kind of hostage, protected by the safe-conduct granted by the enemy and the

assumption that the monarch who dispatched him would consider any injury to

him a great loss. Therefore, by its very nature, engaging in a diplomatic mission

was indirectly a sign of trust in the enemy who was being approached.

Moreover, the emissary’s rank also played a role in negotiations. Sending

someone of high rank was a sign of honour; whereas sending somebody of lower

rank could be seen as an insult. Perhaps the crusaders in Antioch thought Peter

the Hermit a suitable envoy to Kerbogha of Mosul, who was laying siege to the

city in 1098, along with the addition of Herluin as a translator. But a shabby

hermit did not fit the other party’s expectations. Notwithstanding Peter’s report

to the army that he had offered Kerbogha the option of converting to Christianity,

which sounds very doubtful, his appearance alone was probably enough to

persuade Kerbogha to refuse any offer.52 Perhaps his real mission was to suggest

a trial by battle with twenty soldiers instead of a total war, or to discuss possible

surrender, but it seems in this case that the cultural, rather than the linguistic, gap

was the problem.53 Not surprisingly, the mission failed.

When Shirkuh, Saladin’s uncle, wanted to use his captive, Hugh of Caesarea,

as a diplomat to Amalric, he described the prerequisites for a mediator:

You are a great prince of high rank [nobilis] and much influence

[clarissimus] among your own people, nor is there any one of your barons

to whom, if free choice were offered me, I would prefer to communicate

this secret of mine and make my confidant . . . you are a man of high rank

[homo nobilis es], as I have said, dear to the king and influential in both

word and deed, be the mediator of peace between us.54

This flattering description was reported by Hugh himself, who was worried that

as a former captive his own people might be suspicious that he ‘was more

interested in obtaining his own liberty than concerned for the public welfare’. He

therefore preferred that another captive, Arnulf of Turbessel, take this task upon

himself; however, Hugh joined him for the later stages of negotiations and ‘put

the final touches’ to the treaty.55

As one function of the diplomat could also be to identify potential weaknesses

in the opposing side during his mission, astuteness in spying out trends in the

enemy camp played a role in his selection. Prominent diplomats like Saladin’s

brother al-Adil (Saphadin in Western sources) and the qadi Fahr-a-Din, who

negotiated with Frederick II on behalf of al-Kamil, cultivated friendly relationships

with the opposing side. A diplomat’s political judgement was taken into account,

and his influence certainly surpassed that of a simple message bearer. Polyglot

abilities were an advantage, but not a prerequisite. The envoy’s status and

diplomatic skill and knowledge counted for more.

1

2

3

4

511

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

239

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 240

YVONNE FRIEDMAN

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

A well-known instance of the extent to which diplomats could influence the

pact-making process is the part played by al-Adil, Hubert Walter, Bishop of

Salisbury, and Henry of Champagne (Richard’s relative) in the negotiations

between Saladin and Richard I in August 1192. We may well disregard the tearful

speech of love and admiration attributed to al-Adil by Richard of Devizes, as well

as his chronology, but his description of the secret agreement reached without the

sick king’s knowledge rings true in having al-Adil promise, ‘I shall arrange with

my brother either for a perpetual peace for you, or at the least for a firm and lasting

truce.’56 The king’s sudden recovery placed his ministers in a shaky position, as

they had already arranged the treaty terms with al-Adil. Unaware of this agreement, Richard tried to organize an offensive while Hubert Walter and Count

Henry did their best to sabotage mobilization of the army.57 When failure made

the king willing to negotiate, this provided the opening the negotiators needed.

To their surprise, or so they claimed, they found that al-Adil, who was supposed

to be in Jerusalem with Saladin, was in fact near by. Instructed by his colleagues

on how to speak to Richard, al-Adil obtained a temporary truce ratified by the

giving of hands and returned to his brother to arrange his part of the plot.

Baha al-Din’s description of the same encounter proves that al-Adil’s sudden

appearance was no chance occurrence; he was in fact waiting to be summoned.

The Itinerarium peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi knows nothing of the

devious part played by the mediators but agrees that the truce initiative came from

the crusader side and that the king was presented with a written document of a

truce obtained by al-Adil: ‘The terms were recorded in writing and read out to

King Richard, who approved them’, presented there as the best terms for which

Richard could have hoped.58

The important role of the diplomats finds corroboration in Baha al-Din’s

detailed record of the same events. He noted that Richard was presented with a

written draft of the truce as a fait accompli and referred the finishing touches,

including some cardinal terms, to Henry and ‘the others’.59 Baha al-Din mentions

that there was a delay in the oath-taking ceremony, attributed to the fact that the

Christians ‘do not take an oath after eating’, and that they had already eaten that

day. This too may have been the diplomats’ invention and a way of gaining time

to convince Richard. The mediators were apparently successful in setting international policy behind the backs of the rulers who had sent them to negotiate in

their name. Thus the messengers who were only supposed to go between the

camps grew in importance and became independent policy-makers, using the

power bestowed by their connections with the other side.

According to Baha al-Din, Richard had suggested a personal meeting with

Saladin to discuss peace terms back in November 1191. Saladin refused, making

the counter-proposal that he and Richard should send envoys instead. Although

his explanation that it was unseemly for kings to fight after having met, and that

the terms ought to be settled by interpreters and messengers before such a

meeting could take place, may have been a prevarication to gain time, it also

exemplifies the above-mentioned difference in the diplomatic traditions of the two

240

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 241

PEACEMEKING

sides.60 Richard met Philip August for direct negotiations and treaty-making at

Messina in March 1191,61 and a similar meeting took place between Gaillon and

Le Vaudreuil in January 1196.62 Messengers were not unknown in the West but,

apparently, relying on a long tradition of inter-religious diplomacy, the role of

diplomats was more prominent in the East. In fact, Richard and Saladin never met

except on the battlefield as commanders who did not really meet face-to-face, and

it was their diplomats who finally made the treaty between them. Illustrations

showing them fighting a duel belong to the realm of myth, not history.63

Gestures of conciliation

Another noteworthy aspect of the peacemaking encounters between enemies in

the Latin East belongs to the nonverbal realm – gesture and ceremony. Some

historians attribute the importance of gestures in the Middle Ages to the weakness

of literacy in medieval societies. On the one hand, medieval culture greatly

emphasized writing and reading because they were rare and used to spread

Scripture; on the other, gestures publicly transmitted political and religious power

and endowed legal actions with a living image. Gestures bound together human

wills and bodies.64 This was true for both societies, but the encounter between

them emphasized the need for gestures that could be immediately understood and

seen by all. In its stress on visual images through television and the internet,

modern culture may be closer to the medieval perception of the importance of

body language and political rituals than former generations.65 Set conventions and

conciliatory gestures were part of the cultural mechanisms that facilitated peacemaking, or prevented it in the cases where gestures were misunderstood by one

of the sides. For effective, fruitful negotiations, a common cultural language had

to be found. Some of these gestures of conciliation were learned by acculturation

and became a common language; others remained specific to one of the sides and

were never transmitted, whereas some were imposed on one side by the other,

thus becoming part of the language of power.

Potentially, there could be several stages of peacemaking, each accompanied by

its characteristic gestures. Thus, the capitulation of a city was signified by flying

the conqueror’s banner. This gesture occurred in the early encounters between

the enemies and was presumably known to both sides. But how did the losing side

obtain the banner? This presupposes the holding of some negotiations at an earlier

time. These negotiations are usually not spelled out in the chroniclers’ descriptions, perhaps because they were often carried out secretly, whereas the official

submission had to be done publicly, for all to see. Nor did the problems end there.

As each military leader had his own banner, it was important to know whose

banner to fly in order to avoid becoming the victim of internal rifts in the victors’

camp. Thus the anonymous Gesta Francorum claims that both Raymond of St

Giles’s and Bohemond’s banners were flown at Antioch.66 At Tarsus the rivalry

between Tancred and Baldwin over the city’s capitulation, which surrendered by

flying Tancred’s banner in 1097, ended in bloodshed.67 And in August 1099

1

2

3

4

511

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

241

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 242

YVONNE FRIEDMAN

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

crusader rivalry at the siege of Ascalon saved the city from surrender. Richard the

Lionheart’s tactless behaviour in flying his banner at Acre after its surrender did

not alter the city’s fate, but marred his relations with his partners during and after

the Third Crusade.68 William of Tyre mentions signs given by the inhabitants of

a conquered city spelling out their willingness to convert, but he does not explain

what those signs were.69

Another self-explanatory gesture understood by both sides was presenting the

victor with the key to the city. This is shown in illustrations such as that in the

fourteenth-century Grandes chroniques de France, where the surrender of Acre to

Philip Augustus and Richard I of England in 1191 is depicted by the offering to

the monarchs of a disproportionately large key.70 Muslim sources recognized a

similar significance in the transfer of keys. The chronicler al-Yunini (1242–1326)

described the capitulation of Crac des Chevaliers to Baybars in 1271: ‘when Hisn

al-Akrad [Crac des Chevaliers] was captured, the lord of Antartus (which

belonged to the Templars) wrote to al-Malik al-Zahir [Baybars] to request the

making of a truce and sent to him its keys’.71 This was a symbolic gesture, as the

lack of keys did not usually prevent the victorious army from entering the city.

The letter to Baybars presumably included the request for a truce and its proposed

terms, but the keys were the gesture of surrender.

The long list of cities that entered into treaties with the crusaders during the

first years of their rule in the Levant, paying tribute and often retaining their

former leaders as dependants of the new ruler, presupposes the holding of

negotiations about which most chroniclers remain silent. It seems logical to

assume that the vanquished side presented terms of capitulation, both because this

was the usual practice in the East before the crusaders’ arrival, and because it

would be easier for the victorious crusaders just to accept the favourable terms

that had been suggested than to negotiate in line with terms unknown in the

East.72 That perhaps explains the continuation of Eastern practices between the

victor and the vanquished in the East, such as tribute, gifts and the like.

Just as we do not know exactly how the actual fighting on the battlefield ended,

except in cases where the enemy was butchered to total extinction, it is not entirely

clear what signalled a ceasefire. Elsewhere, I have shown that by 1150 there existed

a gesture apparently known to both sides, namely the laying down of arms and

clasping the hands, first on one side, then on the other. This is not the same as

the modern gesture of capitulation by raising both hands, which signifies inferiority and even humiliation, albeit both gestures share the laying down of weapons

as a first step. As opposed to the modern gesture, William of Tyre views the

medieval gesture as showing reverence between military leaders and signalling a

willingness to stop fighting, but not humiliation.73 In 1150 the protagonists knew

each other beforehand from earlier diplomatic missions and the gesture served as

the sign to end fighting and start negotiating. Other Eastern gestures were

ineffectual when dealing with a Western Christian army. Thus, at the Battle of

Ascalon, the vanquished Egyptians ‘threw themselves flat on the ground, not

daring to stand against us, so our men slaughtered them as one slaughters beasts

242

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 243

PEACEMEKING

in a shambles’.74 Neither this gesture nor grasping the victor’s leg to beg for mercy

evoked any pity in crusader hearts, and the chroniclers make no apologies for

killing the vanquished enemy.75 At the Battle of Dorylaeum (July 1097) the

Christian women employed a different gesture of surrender (women were not

supposed to be on the battlefield but, during the First Crusade at least, the

difference between soldiers and noncombatants was blurred):

Stunned and terrified by the cruelty of the most hideous killings, girls

who were delicate and very nobly born were hastening to get themselves

dressed up, they were offering themselves to the Turks so that at least,

roused and appeased by love of their beautiful appearance, the Turks

might learn to pity their prisoners.76

In contrast, the crusaders prided themselves on killing, but not raping, enemy

women: ‘In regard to the women found in the tents of the foe [Antioch 1098],

the Franks did them no evil but drove lances into their bellies.’ 77 The Muslim

chronicler Imad al-Din al-Isfahâni clearly saw the conquest of women as part of

victory and did not spare the reader any descriptive details of their fate.78 In this

case, as in many others, the enemies had distinct cultural languages of war and

peace; the vanquished had to learn the nuances of the other’s nonverbal language

quickly in order to save their lives.

The conclusion of the actual battle was followed by the stage of initiating

negotiations. One gesture involved was that of bowing. Bowing before the ruler is

a liminal gesture: a means of introduction that bridges the gap of the unknown at

a first meeting between sides.79 The lower the bow, the greater the humility

shown. Koziol classifies bowing as a ‘natural’ gesture and therefore familiar to

both sides:

To place oneself beneath another person is clearly a sign of inferiority.

Indeed this meaning is so widespread among social mammals that one

wonders if it does not have some common source, perhaps in their

perception of space or in the reinforcement of dependent, infantile

behavior. Nevertheless, the kind of inferiority a prostration represents is

not inherent in the physical act. Still less does the act convey any information about the world. They are explained in the cultural framework

through their analogies with similar liturgical gestures (as one knelt

before God or saints).80

The only exception to this ranking according to height was the seated ruler: by

standing before him, the messengers or captives showed deference, and the ruler’s

immobility was a sign of his exalted position even though the standing petitioner

was higher.

As Koziol has shown in detail for the West, there was a difference between a

slight bow, kneeling on one knee or two, and the full-length prostration of a rebel

1

2

3

4

511

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

243

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 244

YVONNE FRIEDMAN

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

seeking pardon. We have already seen that, as a gesture of surrender asking for

one’s life to be spared, this gesture was not effective during the First Crusade. In

the East, the usual procedures for initiating treaty-making included bowing,

kneeling and the bringing of gifts, generally performed not by the ruler himself,

but by proxy, via his messenger. A messenger sent to the Byzantine court or the

court of the Abbasid caliph was expected to kiss the ground in front of the ruler

and to bow and kneel.81

The bowing gestures in both Christianity and Islam originated in the religious

sphere and were part of prayer ritual. This has been amply illustrated in the

detailed prayer gestures in the West.82 The religious connotations of prostration

were problematic for the Muslims, as sujud – the full-fledged proskynesis before a

person – is forbidden, as it is supposed to be restricted exclusively to the religious

sphere. Bowing is therefore misused when performed before anyone other than

God, even more so in this case of bowing not just before a human being, but an

infidel.83 Nevertheless, the Byzantine diplomatic protocol insisted on this gesture,

so when the Franks and locals met in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, this

gesture was well known and understood by both sides.

The above-mentioned difference in height could become part of a power play,

as in the case of Muhyi al-Din Ibn ‘Abd al-Zahir (1223–93), the head of the royal

chancery under Baybars and Qalawun, and a court biographer, who described his

part as a diplomat sent to ratify Baybars’ treaty with the Latin kingdom in 1268:

I was an ambassador together with the Amir Kamal al-Din b. Shith to

take the king’s oath . . . We entered Acre on 24 Shawwal [7 July 1268]

and were received by a numerous gathering. The sultan had instructed

us not to demean ourselves before [the king] in sitting or speech. When

we entered to him, we saw him sitting enthroned together with the

Masters [of the orders] and we would not take our seat until a throne

was placed for us opposite him.84

To this point, many of the gestures of conciliation belong to the sphere of natural

human behaviour and, as we have seen, some of its aspects, like gestures of

humiliation and issues of height, have universal meaning. But other gestures were

certainly culture-specific, and we must inquire how the parties to the conflict

learned what they signified to the other side.

This is the case for gifts, which were part of the trust-building, deferential steps

taken by the parties to negotiations. There was, however, a cultural difference

between East and West. In the East bringing gifts was a primary gesture necessary

to open negotiations. In one of the Old French manuscripts of William of Tyre’s

history there is an illustration showing the satraps of the northern principalities

extending their gifts of gold, horses and expensive clothes to Baldwin I, who

receives them sitting on his throne.85 The incident depicted is typical of this kind

of opening gesture. But even when the Muslim side had the upper hand, it still

saw gift-giving as a preliminary stage of negotiations. Thus the messengers

244

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 245

PEACEMEKING

Baybars sent to Acre, who were instructed to behave insultingly to the Frankish

ruler, as we saw above,86 were still dispatched with the gift of twenty of the

prisoners of Antioch, priests and monks.87 When Baybars laid siege to Safed in

1266 he sent the Templars gifts to initiate negotiations for their surrender ‘after

the custom of the Saracens’. When they refused the gifts and catapulted them back

by mangonel, this infuriated Baybars. After conquering the castle he executed all

the Templars even though he had previously promised them safe-conduct.88

In the West, on the other hand, gifts marked the culmination of the agreementreaching process, and usually signified the hierarchical relationship between the

parties: the more prominent side gave a gift to the lesser, thereby signifying its

dependent status. Not to accept was tantamount to effrontery, if not a declaration

of war.

Following Marcel Mauss, Essai sur le don,89 anthropologists emphasize the need

for reciprocity in gift-giving. As it creates some sort of obligation on the part of

the recipient, it is sometimes a dubious blessing. In the words of Arnoud-Jan A.

Bijsterveld:

Gift exchange is defined as a transaction to create, maintain or restore

relations between individuals or groups of people. The reciprocity is an

essential element of this exchange. A gift has the capacity to create those

relationships, because the initial gift obliges the recipient to return some

other gift in the future. Because of the counter-gift, gift-giving is not

restricted to one occasion: do ut des, it is an episode in a continuous social

relationship. Gifts and counter-gifts, landed property, money, objects,

brides and oblates act as a means of social integration.90

If we have seen that, in the encounter between enemies, gift-giving can work to

initiate talks or to seal a mutual obligation, according to cultural background,

Richard the Lionheart exemplifies what I see as a process of acculturation. When

al-Adil initiated peace negotiations by sending Richard ‘seven valuable camels and

an excellent tent’, Richard was severely criticized for accepting these gifts.91 Later,

when Richard wanted to initiate talks with Saladin, he sent him two falcons,

specifying what he would like in return, although it is not clear if these were really

meant as a gift or as a pretext to spy on the enemy.92

The falcon, a hunting bird, was in and of itself a symbol of peace, as hunting

was the favourite pastime of non-belligerent warriors among both the Eastern and

Western nobility. Hunting – the use of arms outside the battlefield – symbolized

peaceful encounters, somewhat similar to modern sport. This is illustrated, for

example, by the Bayeux tapestry, where a herald rides with a falcon on his shoulder

to prove his peaceful intentions.93 Usamah Ibn Munqidh’s colourful description of the two rivals Amir Muin- al-Din and Fulk, King of Jerusalem, hunting

together conveys the same meaning.94 Thus, if in fact carried out, Richard’s

gesture, which is not mentioned by the Latin sources, had dual layers of meaning.

It is interesting to note that Baha al-Din claims that the gift was accepted only on

1

2

3

4

511

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

245

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 246

YVONNE FRIEDMAN

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

the explicit condition that Richard accept a comparable present.95 At the same

time al-Adil made a point of emphasizing that the initiative had come from the

English king; in other words, by Oriental standards, he was the weaker party. The

gift of a falcon as part of a peace treaty is further illustrated by a Western

illumination to William of Tyre’s chronicle showing the Hungarian king returning

the hostages to Godfrey of Bouillon. The two leaders clasp right hands and a

falcon sits on the Hungarian king’s arm, this hunting bird being a gift to seal the

agreement.96 The importance of gifts in the Eastern tradition of negotiations is

further illuminated by the Kitab al-Hadaya wa al-Tuhaf (The Book of Gifts and

Rarities), apparently compiled a generation before the First Crusade. 97 Gifts

presented to Muslim rulers are carefully described, valued and detailed; there was

evidently a special treasury where royal, diplomatic gifts were kept and registered.

Another example of mutual acculturation comes from the gesture of giving the

right hand. Comparison of two treaties, one from 1098 – between the ruler of

Azaz and Godfrey of Bouillon – and the other from 1167 – between the Caliph

of Egypt and a Frankish emissary – shows a process of mutual acculturation,

exemplified by the employment of the Western ceremony of extending the right

hand and the Eastern use of gifts. Both cases reflect cultural mediation via outside

intervention. In the earlier treaty, a captive Christian wife of the Muslim ruler

teaches him Western mores. She instructs him to give Godfrey his right hand

rather than to use his preferred Eastern method of messengers bearing gifts, a

gesture that did not inspire trust on Godfrey’s part. Later Western sources

describe Godfrey, as the victorious party, giving gifts as a sign of lordship and

supremacy. In the second treaty, the diplomat Hugh of Caesarea forces the caliph

to extend his bare hand, contrary to his usage:

‘Therefore, unless you offer your bare hand [my emphasis] we shall be

obliged to think that, on your part, there is some reservation or lack of

sincerity.’ Finally, with extreme unwillingness, as if it detracted from his

majesty, yet with a slight smile, which greatly aggrieved the Egyptians,

he put his uncovered hand into that of Hugh. He repeated, almost

syllable by syllable, the words of Hugh as he dictated the formula of the

treaty and swore that he would keep the stipulations thereof in good

faith, without fraud or evil intent.98

The treaty clauses were important, but for the chronicler, William of Tyre,

imposing the gesture of giving his right hand was seen as a greater diplomatic

victory.

In September 1192, during the protracted negotiations between Richard the

Lionheart and Saladin, this basically Western usage for sealing a treaty is attributed

to both sides. Thus Baha al-Din claims that Richard, who was too sick to read the

draft of the treaty presented to him, said, ‘I have no strength to read this, but I

herewith make peace and here is my hand’, while Saladin said to the Christian

envoys, ‘These are the limits of the land that will remain in your hands. If you can

246

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 247

PEACEMEKING

accept these terms, well and good. I give you my hand on it.’99 Thus, according

to the Muslim chronicler, this gesture had become part of the conventions of

treaty-making on both sides. Notwithstanding this ‘victory’ of Western mores of

peace gestures in the twelfth century, I think that careful comparison of the

few surviving written treaties and earlier treaties in the West and in the East

demonstrates the greater influence of Eastern usage in the Latin East. Such a

comparison must, however, take into account the tendency of the victorious side

to impose its norms on the text and terms of agreement. For the period for which

written texts are extant, this was usually the Muslim party.100

A further source for the ceremonial aspects and nonverbal gestural language of

peacemaking encounters is pictorial evidence. One such source is Matthew Paris’s

illustration of the treaty between Crac and Acre, in which both rulers meet, kneel,

extend their hands, and remove their helmets while their forces look on from a

distance.101 The scene clearly represents a Western image of peacemaking, whereas

Eastern illustrations of peacemaking emphasize gift-giving and a subservient

gesture of bowing, as with the scene depicting Baldwin I from the Old French

manuscript of William of Tyre’s history, described above. Similarly, the Leningrad

manuscript (1225–35) of the illustrated Maqamat al-Hariri has a characteristic

miniature where the hero of the tales, Abu Zaid, approaches a city governor in a

bent posture, arms raised in supplication.102

Another major mechanism of treaty-making that required familiarity with the

enemy was ratification by oath. The use of oaths as a way of ensuring a treaty

would be upheld necessitated some knowledge of the enemy’s religious tenets and

is thus in a way recognition of the ‘other’’s belief at the supreme moment of

distrust, when assurance was most needed. The texts of these oaths, extant for

some of the Mamluk treaties, include a detailed list of the religious beliefs that the

oath-taker is willing to abrogate should he fail to keep his promises, as well as a

self-imposed penance of thirty pilgrimages. Clearly based on local usage, it was

necessary to find a way to make an infidel’s oath valid. Only one of the extant

oaths cited requires swearing on the Gospels, which was the normal Western

procedure in oath-taking and belonged to the legal procedures of the Latin

kingdom. For the Christians, swearing by touching a relic or a holy book served

as a surety, as it made the saint a guarantor of the oath-taker’s good faith. But this

gesture of touching a holy object had no meaning for the Muslims, for whom the

verbal component of the oath was the main one. Even though Saladin and Richard

signed a written document described in detail by Baha al-Din,103 this was not

considered sufficient to ensure its endurance. The taking of oaths was an

important part of peacemaking, and probably more binding than the written

contract. Because both societies were religious, an oath ensuring the involvement

of what they saw as holy – be it their tenets of belief or their saints – was considered necessary.

But can we extrapolate from the detailed late thirteenth-century texts of oaths

to the earlier oaths taken by crusaders and Muslims? No earlier evidence exists for

the content of early twelfth-century oaths, but oath-taking on both sides is

1

2

3

4

511

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

247

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 248

YVONNE FRIEDMAN

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

mentioned in the late twelfth century, during the Third Crusade. Joinville (1250),

however, describes the same kind of pre-formulated, written oaths as the late

Mamluk ones in relating how Louis IX refused to swear because he would never

agree to the clause inserted by renegades: ‘He should be as dishonoured as a

Christian who denies God and his law and in contempt of him, spits on his cross

and tramples it underfoot,’ and was only persuaded to change his mind by the

Patriarch of Jerusalem, who was tortured by the Muslims to this end and promised

to take the sin upon himself in addition.104 The emirs’ oath, which included the

clause, ‘they were to incur the same disgrace as a Saracen who has eaten pork’, was

checked by Nicole d’Acre, ‘a priest who knew their language, and assured him that

according to their law they could have devised no oaths that were stronger’.105

When there was a diplomatic will to compromise, a neutral form could be used, as

in the following example from a Latin document from Genoa, clearly translated

from Arabic: ‘In the name of God the Beneficent, the merciful. May God bless all

the Prophets and Have Peace upon them.’106 This general opening, clearly

formulated by a Muslim, could fit any prophets and all three monotheistic religions.

The formal language of the oaths, while being a tool to bridge the suspicion

between the sides, also made it necessary to learn the other side’s religious tenets.

Yet another realm of peacemaking involving gestures was the concluding stage

of negotiations. In the Christian setting, conflict resolution was achieved not only

by one side admitting the other’s supremacy; the sign of peace was an act of

friendly association – eating and drinking with the other party – and one

consequence was the return of the letter of diffidatio. When war was over, it was

over.107 Gestures of emotion were part and parcel of treaty-making and expected

of the protagonists. In the West public tears were taken as a sign of sincerity,108

but they would probably have been misunderstood in the case of a religious

adversary. In the thirteenth century King Alfonso el Sabio of Spain was able to

provide a format for peacemaking that included not only the formal treaty but its

accompanying gestures, especially the ‘kiss of peace’.109

Men sometimes agree to make peace with one another . . . know all

persons who see this instrument, that . . . So and So . . ., and . . . So and

So . . . have mutually agreed to keep peace with one another perpetually

with regard to the disagreements, disputes, grudges, and insults, of

which they have been guilty toward one another in word and in deed . .

. And as a mark of the true love and concord which should be preserved

between them, they kissed each other before me, notary public, and the

witnesses whose names are subscribed to this instrument, and promised

and agreed with one another that this peace and concord should forever

remain secure, and that they would do nothing against it, or to

contravene it, of themselves, or by anyone else either in word, deed or

advice, under a penalty of a thousand marks of silver; and whether the

penalty is paid or not, this peace and this agreement is to remain forever

enduring and valid.110

248

TAYLOR & FRANCIS FIRST PROOFS - NOT FOR PUBLICATION

�Crusades-01-p.qxd

29/6/10

13:44

Page 249

PEACEMEKING

Such a kiss had very little to do with emotions, but was an obligatory part of

signing an agreement in the West. The kiss of peace was not part of Muslim

cultural heritage, nor was it part of their gestural language. For the Muslims, any

physical contact with a ruler was a special privilege. Usually not granted to an

infidel mediator or envoy, the decision to grant it even to his co-religionists lay

with the ruler.111 Thus, it did not become part of the shared Muslim–Christian

repertoire of gestures in the Latin East.

This was also the case for another significant gesture in the East, the khil’a –

giving a garment or a horse invested with military meaning to a dependant to

signify the transfer of authority and as a special sign of honour – which dates back

to antiquity. This is illustrated by the biblical story of Esther, where Mordecai is

endowed with a horse that the king has ridden and a garment he has worn, with

a herald crying out before him: ‘This is what is done for the man whom the king

desires to honour!’112 This may well be an example of ancient Persian usage.

It was clearly used in the medieval Islamic world, but not in the Western lay

community (although the investiture of clergy may retain something of this old

gesture).113 But it was not a gesture of peace in the medieval West. However, in

one of the first treaties between the crusaders and the local northern principalities,

Godfrey of Bouillon bestowed on Omar of Azaz a hauberk and a golden helmet.

From his perspective, this gesture was part of the feudal gesture of submission,

where the recipient proves his inferiority by giving an oath of fidelity and receiving

a present. For his part, Omar of Azaz probably accepted this ceremony as the