Contents

viii

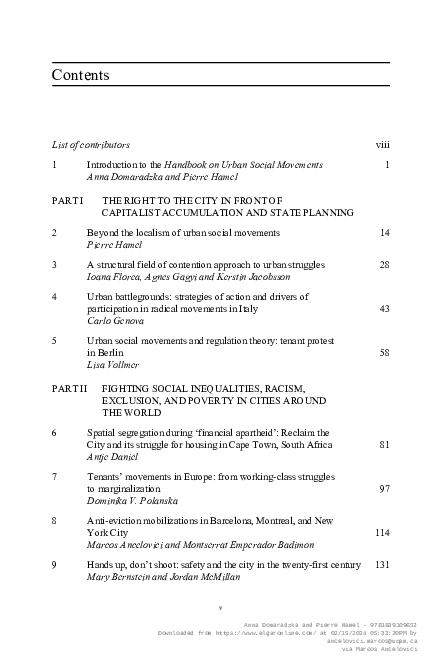

List of contributors

1

PART I

Introduction to the Handbook on Urban Social Movements

Anna Domaradzka and Pierre Hamel

1

THE RIGHT TO THE CITY IN FRONT OF

CAPITALIST ACCUMULATION AND STATE PLANNING

2

Beyond the localism of urban social movements

Pierre Hamel

14

3

A structural field of contention approach to urban struggles

Ioana Florea, Agnes Gagyi and Kerstin Jacobsson

28

4

Urban battlegrounds: strategies of action and drivers of

participation in radical movements in Italy

Carlo Genova

43

Urban social movements and regulation theory: tenant protest

in Berlin

Lisa Vollmer

58

5

PART II

6

7

8

9

FIGHTING SOCIAL INEQUALITIES, RACISM,

EXCLUSION, AND POVERTY IN CITIES AROUND

THE WORLD

Spatial segregation during ‘financial apartheid’: Reclaim the

City and its struggle for housing in Cape Town, South Africa

Antje Daniel

81

Tenants’ movements in Europe: from working-class struggles

to marginalization

Dominika V. Polanska

97

Anti-eviction mobilizations in Barcelona, Montreal, and New

York City

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon

114

Hands up, don’t shoot: safety and the city in the twenty-first century

Mary Bernstein and Jordan McMillan

131

v

Anna Domaradzka and Pierre Hamel - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:33:20PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�vi Handbook on urban social movements

10

Rural–urban migration and the right to the city: urban social

movements in the informal settlements of Namibia and Ghana

Eric Yankson and Ada Adoley Allotey

PART III

11

URBAN MOVEMENTS AND CITY LIFE IN RETROSPECT

Brazil’s urban social movements and urban transformations in

perspective

Abigail Friendly

12

Squatting, a SWOT analysis

Hans Pruijt

13

Building real utopias: urban grassroots activism, emotions and

prefigurative politics

Tommaso Gravante

14

Gentrification, resistance, and the reconceptualization of

community through place-based social media: the future will

not be Instagrammed

S. Ashleigh Weeden, Kyle A. Rich and @ParkdaleLife

PART IV

148

168

185

199

214

IN SEARCH OF URBAN CITIZENSHIP THROUGH

EXPERIENCING VARIOUS MODELS OF SOLIDARITY

15

Claiming urban citizenship: rights and practices

Maciej Kowalewski

16

Beyond co-optation and autonomy: the experience of two

Argentinean social organizations in the face of the left turn

Francisco Longa

248

The rise of urban resistance movements and spatialized

oppression: the Gezi legacy

Aysegul Can

265

17

PART V

18

19

232

COLLECTIVE ACTION, URBAN POLITICS AND/

OR URBAN POLICIES

The everyday politics of the urban commons: ambivalent

political possibilities in the dialectical, evolving and selective

urban context

Iolanda Bianchi

The 2019–2020 Chilean protests: the emergence of

a movement of urban memories

Alicia Olivari and Manuela Badilla

284

300

Anna Domaradzka and Pierre Hamel - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:33:20PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�Contents vii

20

21

22

23

Index

Rage against the machine: how twenty-first century political

machines constitute their own opposition

Stephanie Ternullo and Jeffrey N. Parker

315

Neoliberal urban redevelopment and its discontents: rising

urban activism in Seoul

Chungse Jung

330

Political engagement of urban social movements: a road to

decolonization or recolonization of urban management?

Tomasz Sowada

344

Neoliberal urban governance and slum dweller movements:

the mutual fragmentation of policies and community-based

organizations in the city of Buenos Aires

Joaquín Andrés Benitez, María Cristina Cravino, Maximiliano

Duarte and Carla Fainstein

364

381

Anna Domaradzka and Pierre Hamel - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:33:20PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�8.

Anti-eviction mobilizations in Barcelona,

Montreal, and New York City

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador

Badimon

INTRODUCTION

With the global financial crisis of 2008 (Martin and Niedt 2015), the intensification

and spread of gentrification (Albet and Benach 2018; Lees et al. 2016), and the

financialization of real estate (Rolnik 2019), housing insecurity and affordability

have become central issues in the public debate in the Global North. Some authors

speak of a “global capitalist phenomenon” (Soederberg 2018; Brickell et al. 2017;

Baeten et al. 2021), whereas some international organizations mention a genuine

“global crisis” (UN-Habitat 2011: VIII). Forced displacement and, more specifically,

evictions are the most brutal manifestation of such phenomena. Despite temporary

eviction moratoria adopted in several countries during the Covid-19 pandemic crisis,

the latter deepened this trend. As a result, ‘eviction studies’ have grown dramatically

in the last ten years and today one can no longer argue that “Eviction is perhaps the

most understudied process affecting the lives of the urban poor” (Desmond 2012:

89).1

However, the study of evictions often alternates between, on the one hand,

macro-level structural analysis stressing market forces, urban planning, and public

policy, and, on the other hand, micro-level individual analysis looking closely at

interactions as well as residential choices and trajectories. Even though “evictions are

also collective events that impact whole neighborhoods and communities” (Weinstein

2021: 13), the collective dimension is often neglected and “few studies in this area

touch on questions of collective action at all” (Weinstein 2021: 15). There is thus

a growing number of studies of eviction processes, but few studies of mobilization

dynamics against this pernicious social problem (for an exception, see Pasotti 2020).

While the urban studies and geography literatures do sometimes analyse opposition

to evictions and displacement, they often boil down this opposition to instances of

‘resistance’ (see Annunziata and Rivas 2018; Brickell et al. 2017; González 2016;

Lees et al. 2018; Newman and Wyly 2006). According to Brown-Saracino (2016:

223), “systematic examination of these acts of resistance remains limited, with

more attention devoted to sentiments of resistance than to protests and organizing”.

Similarly, as Lees et al. (2018: 347) point out: “Urban scholars have sought to conceptualize the right to the city … but they have spent less energy on conceptualizing

the actual fight to stay put in the face of gentrification”. Hence Brown-Saracino’s call

114

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�Anti-eviction mobilizations in Barcelona, Montreal, and New York City 115

“for the application of a social movements framework to this sphere of gentrification

studies” (2016: 223).

This chapter answers this call. It will first draw a general picture of evictions as

a social problem and outline the main characteristics of anti-eviction mobilizations. It

will then present the repertoire of action of anti-eviction mobilizations with examples

from recent campaigns and struggles in Montreal, New York City, and Barcelona.

EVICTIONS, OPPORTUNITIES, AND REPERTOIRES

In its most basic understanding, an eviction refers to “the act of expelling tenants

from rental property” (Soederberg 2018: 286). This act is the outcome of a very

codified legal process that begins with the landlord terminating the tenancy of the

property and then filing a lawsuit to have the tenant evicted. It requires a judge to

make an order and a person empowered by the court, sometimes with the help of the

police, to enforce said order. Although the reality and experience of this process vary

across institutional contexts (even within a single country like the United States2),

without these steps, there is no eviction in the strict sense.

However, some scholars challenge such restrictive use of the category ‘eviction’

and point out that tenants can be expelled from their home without going through

the entire legal process of eviction (Hartman and Robinson 2003: 463). Others stress

that the threat of eviction is actually way more prevalent than evictions as such3 and

that, although it does not necessarily lead to displacement, it constitutes a critical

factor exacerbating financial and housing precarity and can even become an ordinary

instrument of property management (Leung et al. 2021: 317; see also Garboden and

Rosen 2019). Brickell et al. (2017: 1) go even further and use the definition proposed

by Amnesty International, namely, “when people are forced out of their homes and

off their land against their will, with little notice or none at all, often with the threat

or use of violence”. Here, tenants are no longer the only category considered and

evictions can affect small landowners or homeowners as well, as it has happened in

Spain and the United States since the 2008 financial crisis for example (foreclosures

should thus be included in the study of evictions; see Martin and Niedt 2015). Such

perspectives entail looking beyond the formal, terminal step of the eviction process

and taking into account a broader range of events and phenomena. Although they face

many problems in terms of data gathering because of the informality they attempt to

grasp (Hartman and Robinson 2003: 466), they have the merit of emphasizing the

fact that evictions are not static or even discrete events but processes. Some prefer

thus to talk of evicting rather than eviction (Baker 2021; Garboden and Rosen 2019).

Once we think of evictions in terms of legal and extra-legal processes, it becomes

obvious that they involve a chain of decisions and events unfolding over time and

that, therefore, tenants and activists can intervene at different moments and in

different ways to try to stop the eviction process. They can intervene upstream, by

providing information and accompanying people facing an eviction. This stage can

involve providing legal assistance in housing court. They can also use disruptive

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�116

Handbook on urban social movements

tactics to put pressure on powerholders – sometimes small landlords, but above all

corporate landlords, banks, hedge funds, and public authorities – to either negotiate

a compromise or gain more time to find a viable housing alternative for the people

affected. They can also intervene downstream, when the eviction process is ending

and the person is about to be physically expelled from their home, and engage in

blockades and other forms of civil disobedience. And finally, they can act alongside,

or after, the eviction process to find alternative accommodations (through squatting,

for example) or campaign for reforms that would alter the institutional context.

These different modes of action during the eviction process are conditioned by the

institutional context and a corresponding structure of opportunities – that is, a set of

unequally distributed pathways for action (Merton 1996)4 – as well as a repertoire

of action – that is, a historically situated set of learned routines on which actors rely

when they act collectively (Tilly 1995, 2008). These two conditioning factors – the

institutional context and the repertoire of action – are closely intertwined insofar as

the repertoire stems from the interaction between actors and the structure of opportunities over time. The more actors engage along a given pathway, the more they are

socialized into using it, and the more they turn to it spontaneously when they need to

make claims or achieve certain goals. Tactical innovations are rather rare and generally take place at the margins (Tilly 1995). As a result, in each institutional context,

certain modes of action are taken for granted whereas others are ignored or ruled out.

In this sense, repertoires of collective action both enable and constrain collective

action and they are more context-specific than movement-specific.

In the following sections, we outline some tactics and strategies of anti-eviction

mobilizations in three different settings: Montreal, New York City, and Barcelona.

Although these cities are by no means homogeneous and cannot be boiled down

to a single mode of action or strategy (we can obviously find a diversity of tactics

and strategies in each one), we focus on emblematic or prevailing tactics to contrast

different logics at play in the struggle against evictions.

MONTREAL, BETWEEN INDIVIDUAL SERVICES AND THE

COLLECTIVE DEFENCE OF RIGHTS

Long considered an affordable renters’ city by North American standards, Montreal

is the Canadian city with the greatest proportion of renters. In 2016, the latter made

up 63.3 per cent of the population, compared to 47.2 per cent in Toronto, 53.1 per cent

in Vancouver, 38.6 per cent in the province of Quebec, and 31.8 per cent in Canada.5

Although there are no exact data about the number of actual evictions – because

many instances of forced displacement simply take place off the radar and are thus

invisible – the Quebec Housing Court (Tribunal administratif du logement, TAL)

collects data about eviction filings (which may end up, or not, in actual evictions).

These data are thus approximative and should be considered the tip of the iceberg.

According to Gallié (2016), each year the TAL receives between 30,000 and 50,000

eviction filings for unpaid rent or rent arrears in Quebec. Moreover, each year about

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�Anti-eviction mobilizations in Barcelona, Montreal, and New York City 117

1 per cent of the tenant population of Quebec has to deal with either a repossession

claim from the landlord (reprise de logement) or an eviction (Gallié et al. 2017). This

trend seems to be deepening. According to the Coalition of Housing Committees and

Tenants Associations of Quebec (RCLALQ), which includes most tenant unions in

the province, the number of tenants contacting housing committees because they are

facing eviction threats increased by 46 per cent in 2021.6 Insofar as most renters in

Quebec are concentrated in Montreal, we can assume that Montreal is more affected

than other parts of the province. This pattern is closely associated with the growth

cycle of the Montreal real estate market. According to Gaudreau et al. (2020), in

Montreal the 2000–2020 period ended with a housing crisis illustrated by a very low

vacancy rate as well as steep rent and sale price increases.

To face this increase in rents, housing insecurity, and evictions, Montrealers can

lean on a solid housing rights movement. In the city of Montreal, there are more

than 15 active housing committees (comités logement) which were created in the

1970s and 1980s (Comité Logement Petite Patrie 2020). Initially created as part of

civic struggles against urban development projects that had led to the destruction of

thousands of housing units in several of the city’s working-class neighbourhoods

in the 1960s and 1970s (see Bergeron-Gaudin forthcoming),7 housing committees

obtained access to public funding in the 1980s and gradually institutionalized and

professionalized. As a result, they partly lost their mobilization potential (Breault

2017). Although housing committees primarily organize at the neighbourhood level,

they also participate in broader mobilizations at the city level and at the provincial

level often led by two provincial-level coalitions: the Popular Action Front for Urban

Redevelopment (Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain, FRAPRU),

which focuses primarily on social housing, and the Coalition of Housing Committees

and Tenants Associations of Quebec (Regroupement des comités logement et des

associations de locataires du Québec, RCLALQ), which focuses on tenants in the

private rental market.

Significant portions of housing committees’ resources are dedicated to providing

individual assistance to tenants to help them deal with abusive landlords, rent hikes,

or eviction threats. Paid staff members offer information, legal advice, and accompaniment. Insofar as Quebec civil law establishes the right of remain of tenants (maintien dans les lieux), the conditions under which a landlord can formally evict a tenant

or significantly increase the rent are limited. In theory, if there are no major repairs

and the tenant is in good standing, the risk of eviction is supposedly very low (unless

the owner wants to repossess the unit for a family member). But this positive picture

requires that housing law actually be enforced and that the city follows up on claims

and contentious cases. Therefore, one of the central tasks of housing committees is to

try and make sure that housing law and municipal regulations are respected. Rather

than aiming at subverting institutions, housing committees rely on them and channel

claims and discontent accordingly, working with the housing court and district-level

authorities as much as possible.

Alongside professionalized individual assistance, housing committees engage

in the collective defence of rights (Breault 2017) through street demonstrations

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�118

Handbook on urban social movements

and protests. These protests do not aim at protecting individual tenants or stopping

a specific eviction. Although they sometimes aim at preventing the eviction of an

entire building which has been recently bought by a corporate landlord, most of the

time these demonstrations and protests target the borough or district, that is, the local

administrative division of the city (arrondissement). Borough-level authorities are

targeted because the municipal governance system of Montreal is quite decentralized

and several competencies are distributed between the City and borough councils.

More specifically, some dispositions that regulate the conditions under which

landlords can divide, extend, or reassign the use of their property are decided at the

borough level and have a concrete impact on tenants’ likelihood of being evicted.

Housing committees pressure boroughs to either block or slow down regulations that

would facilitate such transactions and advocate for more stringent protections of the

tenants’ right to remain. Therefore, the particular configuration of the structure of

opportunities at the local level involves a pathway for action that housing committees

keep using over time and toward which they turn almost mechanically. They adjust

their privileged modes of action accordingly and rarely engage in transgressive contention. They essentially rely on a repertoire of contained contention, that is, which

“takes place within a regime’s prescribed and tolerated forms of claim making, even

if it pushes the limits” (Tilly and Tarrow 2015: 236). This repertoire has constraining

effects. For example, in contrast to cities like Barcelona where, as we will see later on

in this chapter, tenant unions mobilize to block evictions whether the tenant violated

their lease or not, in Montreal housing committees assume that tenants in breach of

their lease are unlikely to avoid eviction and, therefore, do not really invest resources

in trying to stop it. Different pathways for action imply thus not only different repertoires but also different conceptions of what is worth fighting for.

In addition to local protests targeting borough councils, housing committees

organize city-level and provincial-level campaigns in favour of tenant rights, rent

control, and social housing. These campaigns primarily aim at making housing

issues more salient in the public debate and include street marches and occupations

of vacant lots and buildings and sometimes also denounce real estate projects associated with gentrification (Guay and Megelas 2021). Although these occupations can

occasionally last for a few days or weeks, as with the occupation of housing units on

Overdale Avenue in 2001 or of a vacant lot in the Saint-Henri neighbourhood by the

collective À qui la ville? (Whose City?) in 2013 (Saillant 2018), they are generally

temporary, as in May 2017 when a march organized by the FRAPRU ended up

occupying for a few hours an abandoned hospital in downtown Montreal to demand

that it be transformed into social housing. These marches and occupations are rarely

defensive in the sense that they do not try to block evictions. They are offensive

in the sense that they aim essentially at securing new rights and demanding more

investment in social housing as well as the development of new, better housing

policies. The struggle against evictions and urban displacement is thus envisioned as

a long-term policy goal. As a matter of fact, in 2020 the Montreal City Council voted

a new municipal regulation known as right of first refusal (droit de préemption) that

gives priority to the City over private interests to acquire buildings and lots for sale

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�Anti-eviction mobilizations in Barcelona, Montreal, and New York City 119

in order to decommodify them and turn them into social or affordable housing. It also

requires that new residential projects of 450 m2 (4,843 ft2) or more include at least 20

per cent of affordable housing units, 20 per cent of social housing units, and 20 per

cent of family housing units (but real estate developers generally prefer to pay fines

rather than comply, on grounds that abiding by such criteria would devalue the new

properties). Although they have the potential to yield some benefits, these reforms

have contributed to channelling even more the Montreal housing rights movement

inside institutions.

COALITION-BUILDING AND THE EXPANSION OF RIGHTS

IN NEW YORK CITY

Although it is branded as the “Real Estate Capital of the World” by the city’s tourism

agency (Angotti 2008: 6) and associated with images of high-end skyscrapers and real

estate tycoons like Donald Trump, New York City is a city of renters. Throughout

the 2000s and 2010s, rentals represented between 66 per cent and 69 per cent of the

city’s occupied housing units compared to approximately 36 per cent in the country.8

Whereas the proportion of renters is stable, the (average) percentage of household

income spent on rent – what is commonly called the rent burden – has increased from

26.6 per cent in 2000 to 32.2 per cent in 2016.9 The rent burden is particularly heavy

for low-income families. According to Angotti (2008: 47): “Most New Yorkers

cannot afford even a fraction of the rents in the city’s upscale neighborhoods …

About one-third of all households in the city are paying more than 50 per cent of

their gross incomes for housing (which means 60 per cent or more of take-home

pay)”. Such burden reflects both an increase in the cost of rent and a decline of real

wages affecting working-class and middle-class families.10 The rent burden directly

contributes to the nonpayment of rent and rent arrears, which constitute in turn the

vast majority of eviction cases filed each year in the housing courts of New York

City.11 According to the NYU Furman Center (2019: 10), in 2011 there were 200,809

cases filed in the city; by 2017, this number had slightly decreased to 176,590.12

Unsurprisingly, the majority of filings concerned the poorest neighbourhoods of the

city where racial minorities are concentrated, particularly southwest Bronx and, to

a lower extent, central and eastern Brooklyn. Although the majority of cases filed do

not result in executed warrants for eviction, they can still have tremendous negative

effects on tenants, who may, for example, end up blacklisted.

The New York City housing rights movement has a long tradition of fighting

against such residential oppression. The tactics used in the past were quite contentious. In addition to street protests, they consisted in community-wide rent strikes,

from the Lower East Side rent strike of 1904 to the Harlem rent strikes of 1958–1964

(Jackson 2006; Lawson 1983; Schwartz 1983). In the 1930s, they also included

“unevictions”, in which tenant organizers “would move evicted tenants’ furniture

back into their apartment and block marshals from taking it back out” (Mironova

2019: 141). In the 1970s, they took the form of large-scale squatting, as carried out

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�120

Handbook on urban social movements

in the Upper West Side, Morningside Heights, Chelsea, and the Lower East Side in

1970 with Operation Move-In, when activists close to the Metropolitan Council on

Housing and the Young Lords moved low-income Black and Latino families into

vacant buildings that the city was planning to destroy. This tactic is perhaps best

summarized by Operation Move-In’s leader Bill Price, who claimed that the tenants’

most effective organizing tool was a crowbar (Gold 2009: 397). However, these days

of transgressive contention seem long gone. Today, many housing groups receive

public and/or private funding and have a formal nonprofit status. Although there are

still many street protests, occasional sit-ins, and sporadic small-scale rent strikes, the

main tactics and strategies are now contained within institutions and are led by large

coalitions such as the national Right to the City Alliance, founded in 2007, and the

New York State Housing Justice for All coalition, founded in 2017. But contained

contention does not necessarily imply an absence of significant progress. As a matter

of fact, the New York housing rights movement scored significant victories in the

late 2010s, particularly the Right to Counsel (Intro 214-B), adopted by the New York

City Council in August 2017, and the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act,

adopted by the New York State Congress in June 2019. We now turn to the campaign

that made the drive for the right to counsel – the first of its kind in the United States

– successful.

When New York City’s Housing Court was created in 1973, it was supposed to

contribute to the enforcement of housing law in a fair and just manner. However, it

soon became clear that the court worked in the interests of landlords partly because

in New York City the great majority of landlords – between 90 and 97.6 per cent

– were represented by lawyers in eviction proceedings whereas only a small proportion of tenants – between 11.9 and 15 per cent – did (Hartman and Robinson 2003:

477). This made a big difference, as “only 22 percent of represented tenants had

final judgements against them, compared with 51 percent of tenants without legal

representation” (Seron et al. 2001: 419). Ensuring the legal representation of tenants

appeared thus as a relatively straightforward measure that could have a significant

impact on eviction rates. In the 2000s, several voices spoke up in favour of a right

to counsel in Housing Court, but it was only in 2012 that mobilization really started

to pick up.

In 2012, Southwest Bronx tenant organizers from the nonprofit Community Action

for Safe Apartments (CASA) decided to launch a campaign to reform the Bronx

Housing Court in order to bring down the strong eviction rate hurting the borough.13

Their first action was to produce, in partnership with the Community Development

Project at the Urban Justice Center, a research report titled Tipping the Scales on the

experience of the Housing Court from the standpoint of tenants (see RTCNYC 2013).

The report pinpointed the dire experience of the approximately 2,000 individuals,

mostly low-income people of colour, who go through the Bronx Housing Court

every day and recommended to hold the Office of Court Administration (OCA)

accountable and pass a city-wide legislation that would grant tenants a right to legal

representation. Following the report, the OCA made slight improvements, such as

offering better and bilingual information, but it was far from enough and CASA

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�Anti-eviction mobilizations in Barcelona, Montreal, and New York City 121

continued to campaign. In March 2014, Democratic New York City Councilmembers

Mark Levine (District 7, Northern Manhattan) and Vanessa Gibson (District 16,

Southwest Bronx) introduced Intro-214 to make the City responsible for providing

legal representation to low-income residents facing eviction. Although CASA welcomed this initiative, it also decided to form and lead a non-partisan, independent

coalition with more than 25 tenant rights, community, and legal organizations that

would advocate not only for increased funding for representation but also to establish

a right to counsel (RTC). And thus was born the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition.14

Although between 2013 and 2016, New York City increased funding for tenant

legal representation from $6 million to $62 million (Whitlow 2019: 1115), the coalition engaged in multiple and varied actions to advance Intro-214. First, it continued

to produce information under a variety of formats, from a report to videos and toolkits for organizers. It also organized a series of town halls that attracted more than

500 participants as well as a forum at the New York Law School that drew over 450

people and high-profile figures like a Chief Judge and the NYC Human Resources

Administration Commissioner. It developed a logistical plan to implement the RTC

and gave presentations to community boards throughout the city, which resulted in

community and borough boards passing resolutions in support of RTC. In addition,

it collected close to 7,000 signatures for a petition in favour of RTC and held several

press conferences and public hearings with a strong presence on social media. All

these actions contributed to a strong media coverage and thus made the issue of RTC

salient in the public debate. But the turning point was arguably the report commissioned by the New York City Bar Association in 2016, which concluded that the

RTC “would not only pay for itself but also save the city an additional $320 million/

year” (RTCNYC 2017: 3). Henceforth, major players such as the New York Times

started to endorse the RTC (see Cavadini 2020) and on 11 August 2017, Mayor Bill

de Blasio signed a bill Intro-214, making New York City the first jurisdiction in the

United States to formally grant a right to counsel to low-income residents facing

eviction. The central demand of the campaign as well as the strategy elaborated by

the RTCNYC Coalition were directly shaped by the Housing Court system and the

municipal institutional configuration.

While evictions are far from disappearing and many problems persist, the passage

of the RTC has had a significant impact. According to a report by TakeRoot Justice

and RTCNYC (2022: 3), four years after the law passed, “more than 71 percent of

tenants facing eviction have an attorney … and 84 percent of tenants who fight their

case with a Right to Counsel attorney stay in their homes”. The right to counsel not

only expands the range of options available to tenants but also fosters their confidence

and power and, thereby, alters the power dynamics of the tenant–landlord relation.

In this respect, it is worth pointing out that beyond individual benefits and an overall

reduction in the number of evictions, the RTC campaign has strengthened the New

York City housing rights movement by creating an organizational infrastructure that

has survived the initial legislative campaign. The RTC campaign has made tenants

more aware of their rights, created opportunities for them to get involved in multiple

organizational spaces, contributed to making relatively marginal tactics – such as

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�122

Handbook on urban social movements

rent strikes, eviction tribunals, eviction blockades, and worst evictors lists – better

known, and ultimately laid the basis for further networks, coalitions, and campaigns

(TakeRoot Justice and RTCNYC 2022). The RTC campaign fostered the creation of

social capital, that in turn shaped and sustained subsequent waves of mobilization.

The work of the RTC NYC Coalition has thus continued and in 2020, it launched

a new state-wide campaign – Housing Courts Must Change! (HCMC) – aiming at

expanding RTC to the entire state of New York and stopping the “eviction machine”.

The institutionalization of RTC is also illustrated in its diffusion to other cities in

the United States: “Between 2017 and 2022, sixteen jurisdictions passed the right

to counsel for tenants facing eviction” (Roumiantseva 2022: 1362). The experience

of the New York City RTC campaign laid out a strategy and produced data for

obtaining such reforms and showed that such right can be realistically implemented

(Roumiantseva 2022: 1363). There is thus a learning and diffusion process that contributes to strengthening the housing rights movement at the national level and shapes

its repertoire of action.

Nonetheless, important challenges remain. For example, according to a report by

CASA and NWBCCC (2019: 5), “more than half of tenants eligible for RTC had no

awareness of their right to an attorney prior to the first court date. … It means that

they spent weeks fearing eviction, not knowing their rights or options or that they

would be defended in housing court”. Following up on the implementation of RTC,

developing awareness campaigns, and pressuring the city for sufficient funding and

resources to make it a reality is thus critical. The fight must go on.

THE ‘CONTENTIOUS TRIAD’ OF BARCELONA

In contrast to Montreal and New York City, Barcelona, much like the rest of Spain,

is primarily a city of homeowners. In 2011, 70 per cent of Barcelonan households

owned their home whereas only 30 per cent rented it (similarly, in Spain in 2010, 80

per cent of households owned their home while 20 per cent rented it).15 But unfortunately, homeownership has not protected Barcelonans from the threat of evictions,

particularly in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis and the burst of the

housing bubble that had fed economic growth. Between 2008 and 2021, in Barcelona

there were 103,739 executed eviction warrants.16 In 2021, there were 6,327 executed

evictions, for an average of 24 evictions per day (counting only business days), of

which 73.5 per cent involved tenants, 16 per cent indebted homeowners, and 10.5

per cent “precarious occupants”.17 To face such challenge, the manifold housing

rights collectives of Barcelona converged in their use of what we call the ‘contentious triad’, namely, disruption, civil disobedience, and prefigurative action. In what

follows, we first outline the housing rights movement in Barcelona and then lay out

these three tactics.

The city of Barcelona has a long tradition of housing struggles. Several episodes

stand out, such as the mass rent strike of the 1930s (Aisa Pàmpols 2019), the local

mobilizations to improve living conditions in working-class neighbourhoods in the

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�Anti-eviction mobilizations in Barcelona, Montreal, and New York City 123

1970s and early 1980s (Castells 1983), and the squatters’ movement in the 1990s

(Adell and Martínez 2004). One of the housing groups most active today – the

Platform of Mortgages’ Victims (Plataforma de afectadas por la hipoteca, PAH)

– was founded in Barcelona in 2009. As its name indicates, the PAH primarily

defended indebted homeowners threatened with eviction. In just a few years, it

expanded throughout the country, became the spinal cord of a renewed, inclusive,

transversal, and mass housing rights movement, and managed to put the housing

question at the center of the public debate (Ancelovici and Emperador Badimon

2021; Emperador Badimon 2022; Emperador Badimon and Ancelovici 2022). A few

years later, the PAH was joined by another network of housing right collectives,

but the latter were more focused on tenants’ rights or on the right to the city at the

neighbourhood level. The Tenants’ Union (Sindicat de llogateres) was thus founded

in Barcelona in 2017 (a similar union was founded in Madrid almost simultaneously)

while multiple housing and neighbourhood unions (sindicatos de barrio) appeared in

many working-class and middle-class districts of Barcelona (Lira and March 2023).

None of these organizations – whether the PAH, the Tenants’ Union, or neighbourhood unions – benefit from direct public or private funding and they do not have

full-time paid staff.18

The organizations that make up the Barcelona housing rights movement have

developed a series of distinct medium and long-term tactics and strategies. On the

one hand, the PAH and the Tenants’ Union clearly went for a protest strategy aiming

at pressuring elected officials and public authorities into political bargaining to

pass new housing laws defending the rights of tenants, indebted homeowners, and

squatters. On the other hand, neighbourhood unions distrust institutional channels

and favour the construction of autonomous ‘popular structures’ that would concretely

address the everyday problems and needs of people who approach them (Comissió

de formadores del moviment per l’habitatge de Catalunya 2021). Nonetheless, in

spite of these strategic differences, all housing rights groups converge on the use of a

‘contentious triad’ to fight evictions.

The first component of this triad refers to disruptive actions, which we define

as actions that alter “the normal functioning of society and [are] antithetical to the

interests of the group’s opponents” (McAdam 1999 [1982]: 30). These actions have

multiple targets. In Barcelona, insofar as the housing rights movement re-emerged

in the context of the burst of the housing bubble and initially primarily involved

homeowners, banks with important real estate portfolios and which were bailed out

during crisis have been the target of many modalities of disruption: quiet actions

wherein activists pretend to be bank customers and ask for multiple time-consuming

services that prevent desk clerks from attending routine operations; street protest in

front of bank branches to denounce publicly the abuses committed against indebted

homeowners or, sometimes, tenants; loud and festive bank occupations that can last

several hours, until activists manage to meet with the branch manager to negotiate

and reschedule the payment of the mortgage; etc. Disruptive actions have also targeted some actors in the real estate sector. For example, branches of global hedge

funds like Blackstone and Norvet (García-Lamarca 2021) have been targeted by

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�124

Handbook on urban social movements

street protests and occupations. Finally, the housing rights movement has often

targeted elected officials with escraches, that is, testimony protests in front of the

office or private home of elected officials who refuse to stop evictions and support

the demands of the movement.19 The goal of all these disruptive actions is to generate

‘negative inducements’, that is a situation that “disrupt[s] their opponent’s interest to

such an extent that the cessation of the offending tactic becomes a sufficient inducement to grant concessions” (McAdam 1999 [1982]: 30). Thanks to the use of such

disruptive tactics, the Barcelona housing rights movement has succeeded in stopping

many eviction processes.

The second component of the contentious triad is civil disobedience, which

essentially takes the form of blockades to stop eviction warrants from being carried

out. The steps to stop the execution of an eviction warrant were laid out by the PAH

in 2011 and they have shaped the practices and tactics of other housing collectives.

First, activists and supporters gather before dawn in front of the building where the

eviction is supposed to take place to prevent the police, local court bailiffs, or the

locksmith, from accessing the home. When bailiffs arrive to carry out the eviction

– usually after several hours of waiting – activists try to negotiate with them the

suspension of the warrant. If they fail and the bailiffs decide to go ahead with the

help of the police, activists sit down together or make a human chain to try and block

the eviction while they chant slogans inviting neighbours to join them and celebrating the right to stay put and neighbourhood solidarity (Ancelovici and Emperador

Badimon 2021, 2023). The PAH’s anti-eviction protocol stipulates that the blockade

should take place peacefully, without insulting police officers and without seeking

physical confrontation, but without shunning passive physical resistance either. Like

the sit-ins that took place in the American South in the 1960s, such tactics require

preparation and more seasoned activists often take the lead to guide less experienced

or novice supporters. The PAH claims to have stopped hundreds of evictions in such

a way since 2011. However, the repressive response of the police has intensified in

the last few years and in 2022 Barcelona housing groups accumulated more than

€300,000 in fines for disobedience, resistance, and obstruction of police work.20

The third and last component of the contentious triad refers to prefigurative

actions, that is, actions which exemplify the principles and the ends of the movement.

Prefiguration implies that the means and the ends are mutually constitutive and that

ideals should be embodied and experienced here and now instead of waiting for

a revolution or some sort of great upheaval. Instead of claiming that the ends justify

the means, prefiguration proclaims that the means are the ends and vice versa.21 In

the case of the Barcelona housing rights movement, prefigurative actions also have

pragmatic implications because they are about securing alternative housing solutions

and addressing the residential urgency in which the people who have not managed to

prevent or stop the execution of the eviction warrant find themselves. The main form

that such prefigurative actions take is the occupation of vacant buildings, most of the

time newly constructed housing blocks owned by banks or hedge funds, to re-house

evicted families. Sometimes, entire blocks are thus squatted and managed by the new

dwellers on the basis of weekly assemblies in which families discuss the negotiation

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�Anti-eviction mobilizations in Barcelona, Montreal, and New York City 125

regarding the status of the building as well as practical matters related to furniture

and childcare. These occupants often notify the landlord of their willingness to pay

a small rent in the hope of avoiding the stigma associated with squatting (Martínez

2019).

The reliance on this contentious triad of disruption, civil disobedience, and prefigurative action, makes the Barcelona housing rights movement stand out compared

with Montreal and even New York City. Perhaps because in Barcelona housing

groups do not have as much access to public and private funding as in these two

other cities, activists do not have as much to lose and are thus willing to take more

risks. However, some Barcelona housing activists also believe that the transgressive

tactics aforementioned are only short term, temporary solutions and that any real

change requires ambitious legislative reforms. They thus invest resources in many

other tactics aiming at making housing salient in the public debate and building

large, popular coalitions to pressure elected officials. Although they still fall short

of their goals, they have made important gains in the last ten years and show that

contained and transgressive contention can be complementary (Emperador Badimon

and Ancelovici 2022).

CONCLUSION

Although all the mobilizations outlined above respond to evictions, they build on

different experiences and histories and rely on different tactics and strategies. They

suggest that there is not a single or universal best way to fight evictions and advocate

for housing rights. To understand why the housing rights movement relies on certain

tactics and strategies rather than others, we should not implicitly treat the experience

of a particular city as a benchmark to assess others but rather look at how the local

institutional context, power configurations, and inherited repertoires of action shape

tactical choices and strategic calculations.

Furthermore, the anti-eviction mobilizations of Barcelona, Montreal, and New

York City clearly show that housing rights movements never rely on a single tactic.

In this respect, it is worth pointing out that all the mobilizations discussed in this

chapter always rely on knowledge-making practices to develop their strategies. They

produce – either by themselves or in partnerships with activist academics or nonprofit

legal organizations – detailed reports that convey bottom-up accounts of the problems and challenges that local residents experience in their dealings with their landlord, the housing court system, and municipal authorities. These knowledge-making

practices are increasingly becoming digital, as, for example, the spread of online

countermapping work illustrates. The growing visibility of the anti-eviction mapping

project, founded in San Francisco in 2013 and now active in Los Angeles and

New York City as well, is a case in point (see Graziani and Shi 2020; Maharawal

and McElroy 2018).22 Its data visualization work, that seeks to make visible the

landscapes and experiences of both dispossession and resistance through maps and

oral history, is a potentially compelling way to generate and diffuse new stories and

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�126

Handbook on urban social movements

thereby contribute to framing and legitimating the movement’s analysis, claims, and

demands. It suggests that data is not only a resource and an object of struggle but

also a site of struggle in the sense that its production and epistemic dimensions can

have political implications (Beraldo and Milan 2019: 4). We can see similar issues at

play in the growing use of digital apps to collect data on housing conditions and file

complaints against landlords.23 At the same time, however, the rise of this housing

activism 2.0 can contribute to exclusionary dynamics insofar as the access to, and use

of, digital technologies reflect class inequalities (see Schradie 2018).

Finally, the institutional contexts and repertoires of action that shape the tactics

and strategies of housing rights movements are not static. Not only do they evolve

as a result of macro-structural forces, but they are also shaped by the very actions of

movements. It follows that grasping the constraints and opportunities that structure

the struggle against evictions requires that we situate them historically and treat

mobilizations as both an outcome and a cause.

NOTES

1.

Although here we are quoting Desmond, it is worth noting that his own research has

contributed significantly to the study of evictions in the United States and his Eviction

Lab, based at Princeton University, has become a central reference in just a few years (see

https://evictionlab.org/).

2. As Nelson et al. (2021: 696) stress regarding the situation in the United States, “divergent

contexts result in institutional definitions of eviction that are legally, materially, consequentially, and theoretically heterogeneous across the nation”.

3. For example, Garboden and Rosen (2019: 639) note that in Baltimore, MD, “about 6,500

evictions are executed per year, while landlords file for eviction approximately 150,000

times”.

4. According to Robert Merton’s (1996: 153) original conceptualization: “Opportunity

structure designates the scale and distribution of conditions that provide various probabilities for individuals and groups to achieve specifiable outcomes”. For a discussion, see

also Ancelovici (2021: 157–158).

5. Statistics Canada, Census Profile, 2016 Census (https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census

-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E).

6. Sarah R. Champagne and Zacharie Goudreault, ‘2021, année d’évictions au Québec’, Le

Devoir, 28 December 2021.

7. For a brief presentation of struggles against urban development in Montreal in the late

196os and early 1970s, see Castells (1972: 431–444).

8. See United States Census Bureau Data: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/.

9. Data from https://evictionlab.org/.

10. On declining real wages as one of the forces behind displacement pressures in the United

States, see Chapple (2017).

11. According to the NYU Furman Center (2019: 10), eviction filings for nonpayment represented 88.1 per cent of all eviction filing cases in 2010; by 2017, this number had slightly

decreased to 84.3 percent.

12. It should be kept in mind that a single eviction case affects not a single individual but

a household with potentially multiple people. A figure of 200,000 cases a year means

that several hundred thousand more individuals are affected each year in New York City

alone.

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�Anti-eviction mobilizations in Barcelona, Montreal, and New York City 127

13. Our account of the campaign is based on RTCNYC (2017) and CASA and NWBCCC

(2019).

14. The list of member organizations is available at https://www.righttocounselnyc.org/who

_we_are.

15. Observatori Metropolità de l’Habitatge de Barcelona (https://ohb.cat/visor) for Barcelona

and EUROSTAT (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/digpub/european_economy/bloc

-2c.html?lang=en) for Spain.

16. Data for the 2008–2019 period is derived from Observatori DESC (2020) whereas

data for the 2020–2021 period is from Consejo General del Poder Judicial, https://

www .poderjudicial .es/ cgpj/ es/ Temas/ Estadistica -Judicial/ Estadistica -por -temas/

Datos-penales--civiles-y-laborales/Civil-y-laboral/Efecto-de-la-Crisis-en-los-organos

-judiciales/ (last accessed 14 June 2022).

17. Consejo General del Poder Judicial, CGPJ – Efecto de la Crisis en los órganos judiciales

(https://www.poderjudicial.es/cgpj/es/Temas/Estadistica-Judicial/Estadistica-por-temas/

Datos-penales--civiles-y-laborales/Civil-y-laboral/Efecto-de-la-Crisis-en-los-organos

-judiciales/). ‘Precarious occupants’ are former owners or tenants who remained in their

home in spite of having formally lost their property or lease. They are thus former legal

occupants turned squatters.

18. However, the PAH of Barcelona does benefit from indirect funding through the

Observatori DESC, which funds two part-time staff positions.

19. The term Escraches was originally used in Latin America to shame politicians and

high-ranking military officers involved in torture, disappearances, and other crimes

against humanity.

20. See https://beteve.cat/societat/activistes-dret-habitatge-comencen-rebre-multes-desallotjament

-bloc-llavors/.

21. On prefiguration, see Breines (1989 [1982]), Maeckelbergh (2011), and Yates (2015).

22. See the impressive website of the project at https://antievictionmap.com/. There is a similar

initiative – although not as elaborated – in Montreal with the Parc-Ex Anti-Eviction

Mapping Project: https://antievictionmontreal.org/en/.

23. See, for example, the work of the nonprofit JustFix.nyc (https://www.justfix.nyc/en/),

which offers “technology for housing justice”.

REFERENCES

Adell, Ramon, and Miguel A. Martínez. 2004. ¿Dónde están las llaves? El movimiento okupa:

prácticas y contextos sociales. Barcelona: Los libros de la catarata.

Aisa Pàmpols, Manel. 2019. La huelga de alquileres y el comité de defensa económica.

Barcelona: El Lokal.

Albet, Abel, and Núria Benach (eds.) 2018. Gentrification as a Global Strategy: Neil Smith

and Beyond. New York: Routledge.

Ancelovici, Marcos. 2021. Bourdieu in movement: Toward a field theory of contentious politics. Social Movement Studies 20(2): 155–173.

Ancelovici, Marcos, and Montserrat Emperador Badimon. 2021. Ce que l’attente fait aux

mouvements sociaux: Temps et micro-mobilisation dans la lutte pour le droit au logement

en Espagne. Unpublished manuscript.

Ancelovici, Marcos, and Montserrat Emperador Badimon. 2023. Anti-eviction mobilizations

(Spain). In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements, 2nd ed.,

edited by David A. Snow, Donatella Della Porta, Doug McAdam, and Bert Klandermans.

New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Angotti, Tom. 2008. New York for Sale: Community Planning Confronts Global Real Estate.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�128

Handbook on urban social movements

Annunziata, Sandra, and Clara Rivas. 2018. Resisting gentrification. In Handbook of

Gentrification Studies, edited by Loretta Lees and Martin Phillips. Cheltenham, UK and

Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 393–412.

Baeten, Guy, Carina Listerborn, Maria Persdotter, and Emil Pull (eds.) 2021. Housing

Displacement: Conceptual and Methodological Issues. London: Routledge.

Baker, Alexander. 2021. From eviction to evicting: Rethinking the technologies, lives and

power sustaining displacement. Progress in Human Geography 45(4): 796–813.

Beraldo, Davide, and Stefania Milan. 2019. From data politics to the contentious politics of

data. Big Data & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719885967.

Bergeron-Gaudin, Jean-Vincent. Forthcoming. S’opposer à la gentrification: un nouveau

cadrage dans les mobilisations pour le logement à Montréal? In Gentrifications et

résistances à Montréal, edited by Marcos Ancelovici.

Breault, Geneviève. 2017. Militantisme au sein des groupes de défense des droits des personnes locataires: Pratiques démocratiques et limites organisationnelles. Reflets 23(2):

181–204.

Breines, Wini. 1989 [1982]. Community and Organization in the New Left, 1962–1968: The

Great Refusal. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Brickell, Katherine, Melissa Fernandez Arrigoitia, and Vasudevan Alexander (eds.) 2017.

Geographies of Forced Eviction: Dispossession, Violence, Resistance. London: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Brown-Saracino, Japonica. 2016. An agenda for the next decade of gentrification scholarship.

City & Community 15(3): 220–225.

CASA and NWBCCC. 2019. Tipping the Scales: Right to Counsel Is the Moment for the Office

of Court Administration to Transform Housing Courts. CASA-New Settlement and the

Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition.

Castells, Manuel. 1972. La question urbaine. Paris: François Maspero.

Castells, Manuel. 1983. The City and the Grassroots. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA:

University of California Press.

Cavadini, Maeve F. 2020. Our Rights! Our Power! The Right to Counsel (RTC) Campaign

to Fight Evictions in NYC! Documentary available online: https://vimeo.com/457047852.

Chapple, Karen. 2017. Income inequality and urban displacement: The new gentrification.

New Labor Forum 26(1): 84–93.

Comissió de formadores del moviment per l’habitatge de Catalunya. 2021. Quadern de

formació popular: Les estructures populars al moviment per l’habitatge català, I Congrés

d’Habitatge de Catalunya. https://pahc.baixmontseny.org/quadern-estructures-populars/.

Comité Logement Petite Patrie. 2020. Entre fraude et spéculation: enquêtes sur les reprises et

évictions de logements. Montreal: Comité Logement Petite Patrie.

Desmond, Matthew. 2012. Eviction and the reproduction of urban poverty. American Journal

of Sociology, 118(1): 88–133.

Emperador Badimon, Montserrat. 2022. Incluir y representar en espacios militantes: Identidad

colectiva y feminización del activismo en la Plataforma de Afectadas por la Hipoteca.

Revista Internacional de Sociología 80(1): 1–13.

Emperador Badimon, Montserrat, and Marcos Ancelovici. 2022. When movements change

policies: Popular legislative initiatives in favor of housing rights in Spain. Paper presented

at the International Conference Public Policy & Social Conflict: How Policy Changes and

Mobilizations Interact. UQAM, Montreal, Canada.

Furman Center. 2019. Trends in New York City Housing Court Eviction Filings. Data Brief.

NYU Furman Center.

Gallié, Martin. 2016. Le droit et la procédure de l’expulsion pour des arriérés de loyer: le

contentieux devant la Régie du logement. Montreal: UQAM and RCLALQ.

Gallié, Martin, Julie Brunet, and Richard-Alexandre Laniel. 2017. Les expulsions de logement

‘sans faute’: le cas des reprises et des évictions. Montreal: UQAM, RCLALQ and GIREPS.

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�Anti-eviction mobilizations in Barcelona, Montreal, and New York City 129

Garboden, Philip M. E., and Eva Rosen. 2019. Serial filing: How landlords use the threat of

eviction. City & Community 18(2): 638–661.

García-Lamarca, Melissa. 2021. Real estate crisis resolution regimes and residential REITs:

Emerging social-spatial impacts in Barcelona. Housing Studies 36(9): 1–20.

Gaudreau, Louis, Guillaume Hébert, and Julia Posca. 2020. Analyse du marché de l’immobilier et de la rentabilité du logement locative. Note socioéconomique IRIS, June: 1–20.

Gold, Roberta. 2009. ‘I had not seen women like that before’: Intergenerational feminism in

New York City’s tenant movement. Feminist Studies 35(2): 387–415.

González, Sara. 2016. Looking comparatively at displacement and resistance to gentrification

in Latin American cities. Urban Geography 37(8): 1245–1252.

Graziani, Terra, and Mary Shi. 2020. Data for justice: Tensions and lessons from the

Anti-Eviction Mapping Project’s work between academia and activism. ACME: An

International Journal for Critical Geography 19(1): 397–412.

Guay, Emanuel, and Alex Megelas. 2021. Le droit à la ville face à la gentrification des

quartiers populaires montréalais. Une analyse des mobilisations à Parc-Extension et

Pointe-Sainte-Charles. In Montréal en chantier. Les défis d’une métropole pour le XXIe

siècle, edited by Jonathan Durand Folco. Montreal: Écosociété, 216–229.

Hartman, Chester, and David Robinson. 2003. Evictions: The hidden housing problem.

Housing Policy Debate 14(4): 461–501.

Jackson, Mandi Isaacs. 2006. Harlem’s rent strike and rat war: Representation, housing access

and tenant resistance in New York, 1958–1964. American Studies 47(1): 53–79.

Lawson, Ronald. 1983. Origins and evolution of a social movement strategy: The rent strike in

New York City, 1904–1980. Urban Affairs Quarterly 18(3): 371–395.

Lees, Loretta, Sandra Annunziata, and Clara Rivas-Alonso. 2018. Resisting planetary

gentrification: The value of survivability in the fight to stay put. Annals of the American

Association of Geographers 108(2): 346–355.

Lees, Loretta, Hyun Bang Shin, and Ernesto López-Morales. 2016. Planetary Gentrification.

Cambridge: Polity Press.

Leung, Lillian, Peter Hepburn, and Matthew Desmond. 2021. Serial eviction filing: Civil

courts, property management, and the threat of displacement. Social Forces 100(1):

316–344.

Lira, Mateus, and Hug March. 2023. Learning through housing activism in Barcelona:

Knowledge production and sharing in neighbourhood-based housing groups. Housing

Studies 38(5): 902–921.

Maeckelbergh, Marianne. 2011. Doing is believing: Prefiguration as strategic practice in the

alterglobalization movement. Social Movement Studies 10(1): 1–20.

Maharawal, Manissa M., and Erin McElroy. 2018. The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project:

Counter mapping and oral history toward Bay Area housing justice. Annals of the American

Association of Geographers 108(2): 380–389.

Martin, Isaac William, and Christopher Niedt. 2015. Foreclosed America. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Martínez, Miguel A. 2019. Better wins or a long distance race? Social and political outcomes

of the Spanish housing movement. Housing Studies 34(10): 1588–1611.

McAdam, Doug. 1999 [1982]. Political Process and the Development of the Black Insurgency,

1930–1970. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Merton, Robert K. 1996. On Social Structure and Science. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Mironova, Oksana. 2019. Defensive and expansionist struggles for housing justice: 120 years

of community rights in New York City. Radical Housing Journal 1(2): 137–152.

Nelson, Kyle, Philip Garboden, Brian J. McCabe, and Eva Rosen. 2021. Evictions: The comparative analysis problem. Housing Policy Debate 31(3–5): 696–716.

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�130

Handbook on urban social movements

Newman, Kathe, and Elvin K. Wyly. 2006. The right to stay put, revisited: Gentrification and

resistance to displacement in New York City. Urban Studies 43(1): 23–57.

Observatori DESC. 2020. L’evolució dels desnonaments 2008–2019: de l’emergència a la consolidació d’una crisi habitacional. Barcelona: Observatori DESC. https://observatoridesc

.org/ca/l-evolucio-dels-desnonaments-2008-2019-l-emergencia-consolidacio-d-crisi

-habitacional.

Pasotti, Eleonora. 2020. Resisting Redevelopment: Protest in Aspiring Global Cities. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Rolnik, Raquel. 2019. Urban Warfare: Housing Under the Empire of Finance. New York:

Verso.

Roumiantseva, Maria. 2022. A nationwide movement: The right to counsel for tenants facing

eviction proceedings. Seton Hall Law Review 52(1351): 1351–1398.

RTCNYC. 2013. Tipping the Scales: A Report of Tenant Experiences in Bronx Housing Court.

Right to Counsel NYC Coalition.

RTCNYC. 2017. History of the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition. Right to Counsel NYC

Coalition.

Saillant, François. 2018. Lutter pour un toit. Douze batailles pour le logement au Québec.

Montreal: Ecosociété.

Schradie, Jen. 2018. The digital activism gap: How class and costs shape online collective

action. Social Problems 65(1): 51–74.

Schwartz, Joel. 1983. The New York City rent strikes of 1963–1964. Social Service Review

57(4): 545–564.

Seron, Caroll, Gregg Van Ryzin, Martin Frankel, and Jean Kovath. 2001. The impact of legal

counsel on outcomes for poor tenants in New York City’s housing court: Results of a randomized experiment. Law and Society Review 35(2): 419–434.

Soederberg, Susanne. 2018. Evictions: A global capitalist phenomenon. Development and

Change 49(2): 286–301.

TakeRoot Justice and RTCNYC. 2022. Organizing Is Different Now: How the Right Counsel

Strengthens the Tenant Movement in New York City. TakeRoot Justice and Right Counsel

NYC Coalition.

Tilly, Charles. 1995. Contentious repertoires in Great Britain, 1758–1834. In Repertoires and

Cycles of Collective Action, edited by Mark Traugott. Durham, NC: Duke University Press,

15–42.

Tilly, Charles. 2008. Contentious Performances. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tilly, Charles, and Sidney Tarrow. 2015. Contentious Politics, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford

University Press.

UN-Habitat. 2011. Forced Evictions: Global Crisis, Global Solutions. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

Weinstein, Liza. 2021. Evictions: Reconceptualizing housing insecurity from the Global

South. City & Community 20(1): 13–23.

Whitlow, John. 2019. Gentrification and countermovement: The right to counsel and New

York City’s affordable housing crisis. Fordham Urban Law Journal 46: 1081–1136.

Yates, Luke. 2015. Rethinking prefigurative: Alternatives, micropolitics and goals in social

movements. Social Movement Studies 14(1): 1–21.

Marcos Ancelovici and Montserrat Emperador Badimon - 9781839109652

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 02/15/2024 05:21:24PM by

ancelovici.marcos@uqam.ca

via Marcos Ancelovici

�

Marcos Ancelovici

Marcos Ancelovici