Rabbis at Weddings

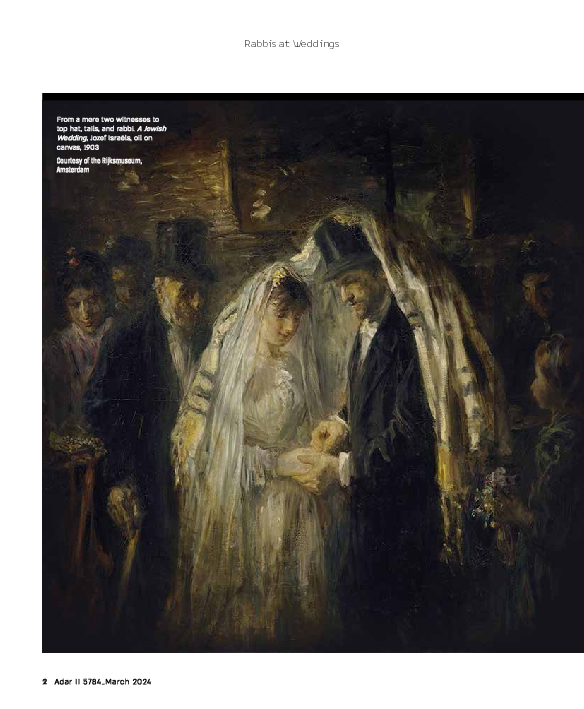

From a mere two witnesses to

top hat, tails, and rabbi. A Jewish

Wedding, Jozef Israëls, oil on

canvas, 1903

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum,

Amsterdam

2 Adar II 5784_March 2024

�Rabbis at Weddings

Who Invited

the Rabbi?

Rabbis have officiated at weddings for centuries,

but the Talmud mentions no such practice. So how

did Jewish clergy become an integral part of the

ceremony? | Ariel Picard

M

any human endeavors begin

spontaneously but gradually

become so institutionalized

that authorization is required.

For instance, the ancient art of healing has

evolved into the science of medicine, in which

practitioners must be not just knowledgeable

and experienced but certified MDs.

This phenomenon applies to Jewish

marriage as well. In the Talmud, the

creation of such a union requires no more

than a man gifting something valuable to

a woman in the presence of two witnesses

for the express purpose of matrimony,

and her accepting the item with that in

mind. Talmudic literature details countless

marriages and divorces, all performed

without supervision. Rabbinic authorities

get involved only when complications arise,

as in the following example:

An incident occurred involving five women,

Segula_The Jewish Journey through History 3

�Rabbis at Weddings

M

A

ZA

L TO V

!

including two sisters, in which a man

gathered a basket of figs […] and declared,

“Behold, you are all betrothed to me with

this basket,” and one accepted it on behalf

of all. The sages ruled: the sisters are not

betrothed. (Mishna, Kiddushin 2:7)

The Talmudic sources all describe a man

betrothing a woman with no rabbi (or

anyone else) performing any ceremony. So

how did the role of officiant develop, and

when did it become reserved for rabbis?

Ordination

Actually, the position of community rabbi

also has a history. Ever since the Second

Temple period, local religious leaders have

addressed halakhic matters both communal

and personal. However, the official rabbinic

position known in Aramaic as mara deatra, “master of the location,” is less ancient

and doesn’t even appear in the Talmud. The

relationship between rabbi and community

was formalized as late as the medieval

period, and according to scholar Prof.

Mordecai Breuer, the rabbinate became

an Ashkenazic profession – complete with

ordination documents – only in the 14th

century.

Communal politics swiftly surrounded

the new, paid position, with power

struggles between established rabbis and

up-and-coming rabbinic talent. With

personal incomes at stake, incumbents

accused their competition of professional

trespassing.

One example, cited by Rabbi Yitzhak

bar Sheshet Parfat (acronym Rivash) in a

responsum, concerns two French rabbis in

4 Adar II 5784_March 2024

the 1380s. Rabbi Isaiah Astruc, leader of the

Savoy Jewish community, aimed to become

chief rabbi of France. He therefore decreed:

All bills of divorce and levirate release

issued without Rabbi Isaiah’s permission

by any rabbi attempting to settle in France

shall be invalid; [any such rabbi’s] books

are those of an idolator. (Responsa of Rivash

271)

Yet the rabbi of Paris, Johanan ben

Mattithiah Treves, son of the country’s

previous chief rabbi, aspired to succeed

his father, only to have his authority

undermined by Rabbi Isaiah’s proclamation.

Rabbi Johanan turned to Rivash, head of the

Spanish Jewish community of Zaragoza, for

help.

The resulting responsum discussed the

The local rabbi was part of

the community leadership

but not necessarily the

exclusive authority. Klezmer

musicians dominate this

portrayal of a Jewish

wedding procession by

Wincenty Smokowski, 1858

Courtesy of the Warsaw

National Museum

�Rabbis at Weddings

origin and nature of the halachic authority

bestowed by ordination. Rivash wrote that

the Talmudic chain of rabbinic ordination

had been broken, making its contemporary

equivalent much less binding. Therefore no

rabbi could impose his authority.

Such is the ordination customary in France

and Ashkenaz. When a student becomes

capable of teaching […], he is rabbinically

forbidden to do so without his teacher’s

permission […] That is to say: he is

henceforth no longer a student; rather, he’s

worthy of teaching others anywhere and

deserves the title “rabbi.” (ibid.)

In numerous Talmudic

anecdotes, rabbinic authorities

intervened in marriages only

when complications arose

No rabbi’s authority is territorial.

Rivash's response notwithstanding,

the trend toward granting rabbis local

jurisdictions seems only to have gained

momentum in the region in question.

Doctors of Halakha

In other words, according to Rivash,

ordination stems not from the relationship

between a rabbi and his community, but

from that between a scholar and his teacher.

A century after Rivash, statesman,

philosopher, and Bible commentator Don

Isaac Abarbanel reestablished himself in Italy

following the expulsion from Spain. In his

It only takes two to

tango – or to wed – in

this medieval illustration

featuring bride and

groom. Festival prayer

book, Leipzig, 1320

Courtesy of ANU Museum

Segula_The Jewish Journey through History 5

�Rabbis at Weddings

new country, Abarbanel was surprised by

the Ashkenazic custom of ordaining rabbis

altogether. He detected Christian academic

influence:

This was the practice in Spain while the

[Jews] were still there, that none among

them was ordained. Yet after my arrival

in Italy, I discovered that the custom of

one rabbi ordaining another had become

common. I perceived that it had begun with

the Ashkenazim, all of [whose rabbis] are

ordained and ordain others. I know not

whence they derived this license, unless they

acquired it from the ways of the non-Jews,

who award doctorates and whose doctors

then appoint others. (Nahalat Avot 6:1)

While agreeing that Jewish scholars

deserve respect, Abarbanel disapproved of

granting them professional qualification,

which he thought reeked of Christian

academic institutions. For Abarbanel, Jewish

scholarship wasn’t a profession, nor did it

require ordination. In the past, the chain of

authority soldered together by ordination

had depended on the Sanhedrin. With

no such body or anything similar in the

Diaspora, sages were to be described as

“neither rabbi nor rabban, terms reserved for

those appointed by those already crowned

with semikha (ordination; see p. 36), since

there can be no ordination outside the land

of Israel” (ibid.).

Rivash’s understanding of ordination as

part of the relationship between rabbi and

student is echoed in Rabbi Moshe Isserles’

(acronym Rema, 1530–1572) Ashkenazic

glosses on Rabbi Yosef Karo’s code of Jewish

6 Adar II 5784_March 2024

�Rabbis at Weddings

law, the Shulhan Arukh:

The matter of ordination as practiced

nowadays indicates that [one] has reached

the level of instruction and that the rulings

he issues are by permission of his teacher

who ordained him […]. (Yoreh De’a 242:14)

Rema also qualifies the value of rabbinic

ordination:

Some say that the rulings of anyone not

ordained [by the rabbinic authority they

recognize] […] are meaningless, and

his divorces, etc., are suspect, unless all

acknowledge him as a widely recognized

expert who humbly doesn’t aspire to

greatness [or titles]. (ibid.)

That is, ordination may signify professional

expertise, yet even someone without such

credentials but renowned for his wisdom

and knowledge is just as authoritative.

Qualifications

Despite the objections of Abarbanel and

Rema, the rabbinate became a certified

profession. The Ashkenazic trend was

strengthened by the modern period’s

obsession with qualifications. Even as

modernity weakened the sense of religious

obligation, rabbinic authority was bolstered

by certification and institutionalization. In

the field of marriage and divorce, however,

that process had begun much earlier.

Even the Talmud was uncomfortable with

the fact that betrothals and divorces could be

enacted by anyone:

Rabbi Judah said in Samuel’s name: Anyone

unfamiliar with the nature of divorce and

betrothal should have no business with

them. (Kiddushin 6a)

Rashi (medieval commentator Rabbi

Shlomo Yitzhaki) comments here that

expertise regarding the consequences of such

agreements is vital.

“I know not how rabbinic ordination

became permitted if not by aping the nonJews’ awarding of doctorates” – Abarbanel

Facing page: was

community rabbis’

ordination influenced by

that of Christian clergy

and other professional

certification? Meeting of

Doctors at the University

of Paris, Etienne Collault,

16th century

In Jewish law, betrothal

requires only that a man

give his intended a gift

in the presence of two

witnesses. The ketuba

(marriage contract)

accompanying this act

details the husband’s

obligations to his wife

and has been compulsory

since at least the fourth

century. Ketuba from

Livorno (Leghorn), Italy,

1698

Segula_The Jewish Journey through History 7

�Rabbis at Weddings

“Should have no business with them” – to

serve as a judge of the matter, lest he permit

marriage between those forbidden to marry

one another, resulting in an error that

cannot be rectified.

Not just a matter of

Jewish law. Officiating

at weddings was also

lucrative for the local

rabbi. A Jewish Wedding,

colored print by Dirk

Jansz van Santen, late 17th

century, Netherlands

This fear resulted in a series of rabbinic

restrictions on those authorized to perform

weddings and divorces. Maimonides

described a decree he himself helped

formulate:

8 Adar II 5784_March 2024

The rabbis of Egypt have issued – and

brought a Torah scroll out in public to

declare – a ban on the inhabitants of

the villages of Damanhūr, Bilbeis, and

Almohella to prevent any man among them

from marrying or divorcing his wife other

than by means of the rabbis of the Egyptian

villages: Rabbi Halfon, rabbinic judge of

Damanhūr; Rabbi Yauda Hakohen, rabbinic

judge of Bilbeis; and Rabbi Perahia, rabbinic

judge of Almohella. We have agreed to

ban whoever grants a license [to preside

over marriages and divorces] to anyone

unschooled in the nature of divorces and

betrothals. (Maimonides’ Responsa, vol. 2,

Blau edition, sec. 348 [Hebrew])

Similar decrees were enacted in various

times and places. The Rules of the Exiles

of Castile in the City of Fez, a collection of

�Rabbis at Weddings

M

A

ZA

not detract from the wage of

the local rabbi by officiating at

wedding ceremonies and taking the

accompanying gratuity for himself, since

that is the reward of the resident rabbi. [The

guest] may, however, perform the marriage

and hand the payment to the regular rabbi.

(Yoreh De’a 245:22)

L TO V

!

Israeli Invention

Local rabbis clung to their

right to perform marriages,

refusing to share the

privilege or its fee

rabbinic rulings beginning in the late 14th

century, included retrospective annulment

of any marriage performed by an unlicensed

rabbi. The main idea was to prevent

weddings performed by people unaware of

the complications arising from halakhically

inappropriate relationships. But there was

an additional motive, originating wherever

rabbis were salaried. Rema mentions it in

another gloss on the Shulhan Arukh:

If a guest sage comes to town, he should

The exiles of Castile

brought their

stringencies with

them to Morocco, even

annuling unauthorized

marriages. A Jewish

Wedding in Morocco,

Eugène Delacroix, 1839

Courtesy of the Louvre

Museum, Paris

In the United States, Canada, and many

other countries, marriages may legally be

performed and registered by a member of

the clergy, a public official such as a judge, or

possibly even a civil celebrant. The modern

state’s insistence on marriage registration,

beginning in 18th-century Europe, probably

contributed to the institutionalization

of weddings and the requirement of a

recognized rabbinic presence.

The next stage in formalizing rabbinic

officiation at weddings occurred shortly after

the Israeli Chief Rabbinate’s inception. This

body decreed that all marriages be registered

with the local rabbinate. Any time lag

between betrothal and wedding was likewise

forbidden, formally ending an ancient

custom that had long since fallen out of use

lest it lead to abandoned brides. Betrothed

couples delaying their weddings would be

forced to divorce. Furthermore:

We hereby forbid any person or rabbi of

Israel to arrange betrothal or marriage

unless he has been appointed in this capacity

in writing and by signature of the Chief

Rabbinate of the Cities of the Land of Israel.

[…] Violators will face excommunication –

with all the weight of decrees made by the

Segula_The Jewish Journey through History 9

�Rabbis at Weddings

In a Word | Semikha

The Hebrew word semikha originally

indicated the laying of hands upon a

person or animal, designating him/it for a

certain purpose. The verb appears in the

Pentateuch in the context of sacrifices

offered in the Tabernacle. No sacrifice

made in fulfillment of a vow or to obtain

atonement was valid unless the owner of

the animal leaned on it with both hands

prior to its slaughter.

Perhaps by association, a similar

procedure is described for the biblical

transfer of leadership. In Numbers (27:18),

God instructed Moses to “Take Joshua

son of Nun, a man of spirit, and lay your

hand upon him.” Through this ritual, some

measure of Moses’ greatness was passed

on to his successor.

Ethics of the Fathers opens by

documenting the chain of rabbinic

leadership from Moses until the beginning

of the Second Temple period. The Talmudic

tractate Sanhedrin recounts the valiant

but futile rabbinic struggle to maintain the

practice of semikha and thus the chain

of ordination despite a ban imposed by

Roman emperor Hadrian.

This chain was ultimately broken, leaving

Jewish judges “unordained” and therefore

no longer authorized to impose fines or

other penalties.

Outstanding rabbis such as Maimonides

and Yaakov Berab of Safed (1474–1546)

attempted to restore the practice of

semikha but without success.

rabbis of Israel – in all existing communities

of Israel and those that may arise in the

10 Adar II 5784_March 2024

Country or community?

Israel’s Chief Rabbinate is

essentially one big “local

rabbi,” though its rulings

carry the force of law. The

Great Rabbinical Court

sitting in judgment in its

offices in Heikhal Shlomo,

King George Street,

Jerusalem, 1959

future. (Rabbi Isaac Halevi Herzog, Heikhal

Yitzhak, Even Ha-ezer, vol. I, sec. 5, note 1)

The Israel Chief Rabbinate Law, passed in

1980, listed among the powers of the Chief

Rabbinical Council the following:

(a) To enable a rabbi to act as a marriage

registrar and (b) to appoint certain rabbis

as marriage registrars from among those so

authorized above. (ibid., sec. 2 [6])

Photo: Moshe Pridan,

Israel National Photo

Photo Archive

Yehezkel Landau, chief

rabbi of Prague, ruled

that only in the town

rabbi’s absence could

his colleague perform

a wedding. Portrait of

Landau, 18th century

“We hereby forbid any person

or rabbi to arrange betrothal

or marriage unless appointed

by the Chief Rabbinate”

�Rabbis at Weddings

In 2017, the rabbinate defined the criteria

qualifying rabbis to officiate at marriages.

Parliamentary legislation proposed in 2009

had even stated that any couple married or

divorced by an unauthorized officiant would

face two years in prison, while the master

of ceremonies himself would serve a sixmonth sentence. Although the bill didn’t

pass, it shows how institutionalized marriage

has become. One reason is the increase in

private, non-rabbinate weddings in Israel,

including illegal marriages involving minors

or clandestine nuptials designed to prevent

widows or single mothers from losing welfare

payments contingent on their unfortunate

status. The law’s creators believed that only the

threat of criminal prosecution could halt such

practices.

Also in the background is the longsimmering struggle between Israel’s

Orthodox sector, represented by the

Chief Rabbinate, and the Reform and

Conservative movements. Only the

Chief Rabbinate is authorized to perform

marriage, divorce, and conversion.

Nonetheless, as stated, a fair number

of Israelis sidestep the rabbinate and

cement their relationships with non-

Orthodox ceremonies. In addition to the

circumstances discussed above, some go

this route because as far as the rabbinate is

concerned, the bride or groom in question

isn’t Jewish. Others want an egalitarian

ceremony or just prefer to defy the

Orthodox monopoly on marriage.

Current attempts to circumvent the

requirements of certification and officiation

by a state-licensed Orthodox rabbi seem to

be trending back to where we started, with

weddings validated by two witnesses alone.

Many modern Jews would rather avoid

officialdom and run their lives and life-cycle

events as they see fit. Too much oversight,

though born of the worthy intention of

maintaining the integrity of the Jewish

people, can backfire, producing exactly the

opposite effect.

State occasion. President

Haim Herzog at the

wedding of his son Isaac,

current president of

Israel, with future chief

rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau

officiating, 1985

Photo: Yaakov Sa’ar,

Sa’ar,

Israel National Photo

Photo Archive

Further reading:

Kopel Kahana, The Theory of Marriage in Jewish Law, Brill

1966. Mendell Lewittess, Jewish Marriage: Rabbinic Law,

Legend, and Custom, Aaronson 1994

Rabbi Dr. Ariel Picard A research fellow at the

Shalom Hartman Institute. His books include

The Philosophy of Rabbi Ovadya Yosef in an

Age of Transition (Hebrew)

Segula_The Jewish Journey through History 11

�

אריאל פיקאר Ariel Picard

אריאל פיקאר Ariel Picard