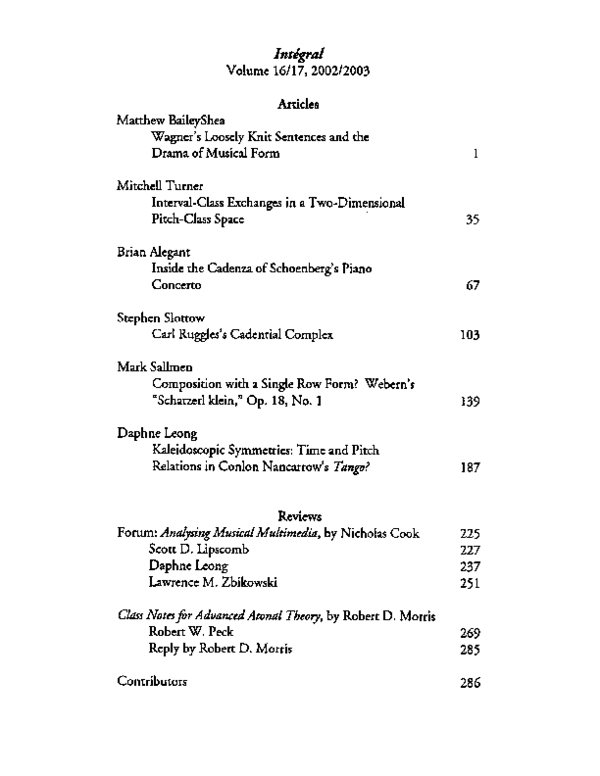

Integral

Volume 16/17, 2002/2003

Articles

Matthew BaileyShea

Wagner's Loosely Knit Sentences and the

Drama of Musical Form

1

Mitchell Turner

Interval-ClassExchanges in a Two-Dimensional

Pitch-Class Space

35

Brian Alegant

Inside the Cadenza of Schoenberg'sPiano

Concerto

67

Stephen Slottow

Carl Ruggles'sCadential Complex

103

Mark Sallmen

Composition with a Single Row Form? Webern's

"Schatzerlklein," Op. 18, No. 1

139

Daphne Leong

Kaleidoscopic Symmetries:Time and Pitch

Relations in Cordon Nancarrow's Tango?

187

Reviews

Forum: AnalysingMusicalMultimedia^by Nicholas Cook

Scott D. Lipscomb

Daphne Leong

LawrenceM. Zbikowski

225

227

237

25 1

ClassNotesfor AdvancedAtonal Theory^

by Robert D. Morris

Robert W. Peck

Reply by Robert D. Morris

269

285

Contributors

286

�Review Forum

Analysing Musical Multimedia by Nicholas Cook.

Oxford: Clarendon Press;

New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Why a whole forum of reviews on Cook's AnalysingMusical

Multimedia* I hope readers find that the diverse contributions by

Scott Lipscomb, Daphne Leong, and Lawrence Zbikowski justify

the forum almost entirely on their own. Then there is the book. It

inaugurates its own sub-discipline which reaches into several

disciplines besides mainstream music theory, such as music

perception and cognition, human physiology, cognitive science,

film studies, cultural history- -even television marketing. Of course

the book invites reaction from so many angles.

From the perspective of music perception and cognition

research, several issues arise. To some extent these spring naturally

from the perceptual interaction between aural and visual sensory

modalities, which is inherent to multimedia. Yet they also stem

from the particular orientations Cook chooses in addressing his

topic. For instance, how relevant is synaesthesia to analyzing

multimedia? What is the significance of a theory devoted to

analyzing music-derived multimedia, as opposed to theatrical films,

in which music is secondary? How does Cook's book spur

empirical scientific work on music perception and cognition, and

stimulate interdisciplinarydialogue? Lipscomb's contribution to the

forum considers these issues, also bringing to bear his experience

teaching and applying Cook's theory in a classroom context: a

course he has taught on Multimedia Cognition.

Cook's topic raises issues that rarely,if ever, arise when music is

considered alone. So it provides a fresh context to examine the

application of pre-existing theories, such as those of musical

rhythm and grouping. For instance, what does it mean for one

medium, say a visual one, to model a particular "hearing" of a

musical passage?How is such a model evaluated?And how does the

artistic merit of the multimedia piece influence the process and

�226

Integral

result? These are among the issues examined in Leong's

contribution, which is probably the first in our field to evaluate a

multimedia analysis on grounds of rhythmic accuracy. It opens

doors to future rhythmic analysisof film.

Multimedia also provokes inquiries into musical meaning.

Schoenberg envisioned Die gluckliche Hand from the start as

multimedia, combining music not just with text, but also elaborate

instructions for stage action and color lighting. How do we

interpret the meaning(s) from such a work? How do recent

developments in the musical application of conceptual blending

theory offer ways to streamline and formalize Cook's approach to

Die gluckliche Hand's "lighting crescendo"? Zbikowski explores

these concerns. He then re-analyzes the "lighting crescendo" using

the technology of conceptual integration networks (CINs). His

analysis points to the psychological tumult of the opera's

protagonist, as a meaning conjured by the multimedia experience.

Finally, I suspect the relevance for our discipline of analyzing

musical multimedia is not yet fully appreciated. Music theorists

already routinely lavish analytical attention on a large body of

classical music works, operas and ballets- from Monteverdi and

Striggio's Orfeo to Stravinsky and Balanchine's Agont and

beyond- which are actually instances of musical multimedia, and

therefore fall within the scope of Cook's theory.1 Furthermore,

multimedia permeates many aspects of our culture- both high and

low - more now than ever. The climate of technological change in

the early 21st century forecasts a rise in multimedia, and our access

to it. There is good reason for the sub-discipline of analyzing

musical multimedia to grow.

Joshua Mailman

Reviews Editor

In fact, aspects of Cook's theory have already been applied to opera in Philip

Rupprecht's Britten s Musical Language (New York: Cambridge University Press,

2001).

�Modeling Multimedia Cognition:

A Review of Nicholas Cook's

Analysing Musical Multimedia

Scott D. Lipscomb

It is perhaps surprising that a text published over five years ago

should warrant a series of reviews in a respected scholarly journal.

This occurrence suggests at least two very important outcomes.

First, "multimedia"- specifically, the role that music plays within

such a context- is finally being given the attention it deserves as a

sociologically relevant artifact of contemporary culture, thus worthy

of discussion in scholarly music journals. Second, Nicholas Cook's

Analysing Musical Multimedia has made a significant contribution

to this dialogue in its emphasis, as evident from the book's title,

upon the musical component of this multimodal experience.

Cook's text does not serve, however, to initiate the analysis of

musical multimedia. In fact, the practice of combining music and

drama dates back millennia to the Greek dramas of Aeschylus,

Euripides, and Sophocles and can be traced throughout the

evolution of Western civilization, as represented in the Medieval

sacred drama, courtly displays of the Renaissance, Baroque opera,

Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk,and the development of sound film in

the 20thcentury. Beginning in the 1950s, with interest intensifying

during the most recent two decades, music researchers and

psychologists have begun to investigate empirically the relationship

between hearing and seeing... sound and image. As I have noted

elsewhere,1 in the field of perceptual psychology, interaction

between the aural and visual sensory modalities is welldocumented.2 Empirical studies investigating the intermodal

relationship in more ecologically valid contexts was initiated in the

middle of the 20th century, but did not begin to attract significant

attention until the late 1980s. Using a simple "drop the needle"

technique, Tannenbaum discovered that music does influence

Lipscomb, in press.

Sec, for example, McGurk and MacDonald 1976, Radeau and Bertelson 1974,

and Staal and Donderi 1983.

�228

Integral

verbal ratings collected from participants following a dramatic

presentation, whether live on stage, in a studio-taped version, or in

a video recording of the live performance.3 Using an industrial

safety film depicting three accidents, Thayer and Levenson found

that skin conductance level, a physiological measure, varied

significantly between two conditions, one using a series of mildly

active major seventh chords ("documentary music") and one using

a repetitive figure based on diminished seventh chords

incorporating harsh timbres ("horror music").4 Marshall and

Cohen, a study that Cook uses as an empirical basis for his own

model of musical multimedia and its cognition, found that the

information provided by a musical soundtrack significantly affected

judgments of personality attributes assigned by subjects to each of

three geometric shapes presented as "characters" in the film.5

Based on the results of this investigation, the authors proposed a

paradigm to explain the interaction of musical sound and geometric

shapes in motion entitled the "Congruence-Associationist model."

They assumed that, in the perception of a composite A-V

presentation, separate judgments were made on each of three

semantic dimensions (i.e. Evaluative, Potency, and Activity)6 for

the music and the film, suggesting that these evaluations were then

compared for congruence at a higher level of processing. Since the

publication of Cook's text in 1998, Annabel Cohen has gone on to

expand the model, significantly clarifying the multi-level

relationships that occur between sensory modalities.7

Cook's text is divided into two parts. The first half of the book

provides a foundation for the theoretical framework proposed by

the author. The remainder of the text consists of three analytical

case studies or exemplars to which this specific framework is

applied. As a general outline, this organizational structure is

extremely clear and provides the reader a functional and concise

method of analysis with examples of its practical application. A

Tannenbaum 1956.

Thayer and Levenson 1984.

Marshall and Cohen 1988. For a detailed discussion of these studies and other

related work, see lipscomb 1995 or lipscomb and Kendall 1994.

Osgood, Sud and Tannenbaum 1957.

7

Cohen 2001.

�Review Forum: Lipscomb on Cook

229

detailed analysis of the actual content, naturally, reveals numerous

possibilities for further discussion or debate, a continuing process

for which Cook has provided an excellent starting point. I have

had the opportunity to use Analysing Musical Multimedia as a

textbook in a graduate-level selected topics course on "Multimedia

Cognition" (MUSJTHRY 335-0) at Northwestern University.

Cook's text, Michel Chion's excellent Audio-vision? and a course

reader including a variety of theoretical and empirical works related

to the multimedia experience provided an excellent triumvirate

upon which to build knowledge and facilitate discussion about the

multi-modal experience.9 Given my own background and

experience, the present review of Cook's text will represent a dual

perspective: that of a music/multimedia researcherand a university

professor.

The opening section of Part I introduces many of the concepts

that Cook deals with in the following chapters. To demonstrate the

manner in which music can influence (or determine) the meaning

of a sequence of visual images, several highly creative commercials

are deconstructed according their content, both visual and

auditory. In my opinion, this is one of the most valuable sections

of the text, clearly demonstrating the extremely important role that

music plays in this context and hinting at issues of congruence

between the audio-visual (A-V) components... an element that will

come to play a defining role in Cook's paradigm. I found myself

at times,

about

the selected

frustrated,

reading

examples- completely unfamiliar to me and wanting desperately

to view the commercials so that I could experience the A-V

combinations described for myself, affording a basis for critical

analysis and debate. Perhaps selecting exemplars that are more

readily available would have served the audience better or, ideally,

making these commercials available on a DVD, either

accompanying the text or available separately as a "companion."

Instead, at the outset, the reader is placed in a position where one

must simply trust the author's description and analysis of the

8 Chion

1990.

The complete course syllabus, including a list of literature contained in the

course reader, can be found on the "syllabi"page of the present author's web site:

http://faculty-web.at.northwcstern.edu/music/lipscomb/.

�230

Integral

existing interrelationships. Despite this criticism, the clarity of

descriptions and select captured still images make the author's

intended points effectively.

Particularly important in these introductory pages is Cook's

insistence that music be considered a communicative medium,

extending beyond mere effectinto the realm of meaning. This is an

important distinction, though not novel,10 since the model of

multimedia toward which he is leading the readerwill require that

the meaning attained by each modality be compared for similarity

and/or difference. Equally important is his distinction between

connotative and denotative meaning, characteristics clearly

differentiated in a musical context within the work of Susanne

Langer.11 Drawing upon information in Joseph Kerman's

monograph on opera,12 Cook suggests that, within this specific

musical context, "the identification of word with denotation and

music with connotation suggest [a] kind of layered, noncompetitive relationship" (119). To accomplish its connotative

task, according to Cook:

Musicalstylesand genresofferunsurpassed

for communicating

opportunities

complex social or attitudinal messages practically instantaneously; one or two

notes in a distinctive musical style are sufficient to target a specific social and

demographic group and to associate a whole nexus of social and cultural values

with a product (16-17).

With these basic concepts clearly delineated and the multimedia

artifact as an object of study, the foundation for Cook's framework

has been laid.

At this point in the text, I was confused to find myself thrown

into a discourse concerning synaesthesia. Though perhaps a topic

worthy of brief mention within a book on multimedia, the amount

of verbiage devoted to this phenomenon, affecting such a small

percentage of the population, seems to imply an importance that is

hugely disproportionate to its actual impact upon the typical

multimedia experience. Its relevance might be more marked were

there a consistent A-V relationship from one synesthete to another.

See, for example, Campbell and Heller 1980 or Kendall and Carterctte 1990.

11

Langer 1942.

12

Kerman 1956.

�ReviewForum:Lipscombon Cook

231

This is not the case, however,and the fact that colorsperceivedin

the music listening experiencevary greatly between individuals

affectedby this highlyuncommonperceptualanomalysuggeststhat

this is not an appropriatebasisupon which to build an overarching

theory of multimedia perception. This is, of course, the same

conclusion to which Cook comes prior to formulatinghis own

model, makingthe guidedtour throughsynaesthesiaand associated

theorists- fascinating as it is at times- seem an unnecessary

detour. The manyfascinatingmultimediaworksupon whichCook

focuses in this section (Messiaen's Couleursde la Citi celeste,

and Schoenberg'sDie glilcklicheHand)could

Scriabin'sPrometheus,

easily have been made relevantbased on aestheticvalue, without

the need for a long-windeddiscussionaboutsynaesthesia.It is with

the introductionof a metaphor-basedmodel that Cook returnsto

what will truly become useful in the analysis of cross-modal

relationships. The present author found the discussion about

"recordsleeves"laterin this samechapterto be of little relevanceto

the primarythesisof the text andwould havelikedto haveseen this

space allotted to more meaningful and relevant subject matter

relatingto the truemultimediaexperience.

In the second chapter, Cook's critical analysis of several

important models of cross-modal relationships (Kandinsky,

Eisensten,and Eisler)puts the readerright back on trackin the

process of consideringthe interrelationshipof the auditoryand

visual perceptualmodalities. Supplementedwith commentsmade

by esteemedfilm composerBernardHerrmannand the resultsof

empirical researchinto the relationship,13the author carefully

builds a case for considerationof the multimedia context as a

metaphoricalrelationship,based on "enablingsimilarity"and the

resulting"transferof attributes"(70).u Cook also identifiesthe

- of "emergentproperties"

presence- and stressesthe importance

in the multimediacontext.Such attributesaresaid to be negotiated

between the interacting media within a specific context and

"...cannot be subsumed within a model based on the simple

mixing or averagingof the propertiesof each individualmedium"

thatofMarshall

andCohen1988;discussed

Primarily

previously.

14AfterMarks andLakoff

andJohnson

1980.

1978,

�232

Integral

(69). Just prior to the presentation of his own model, Cook

summarizeshis perspective concisely in the following way:

. . .whatever music's contribution to cross-media interaction, what is involved is a

dynamic process: the reciprocal transfer of attributes that gives rise to a meaning

constructed,not just reproduced,by multimedia (97, emphasis added).

This emphasis on an emergent meaning that is constructed as a

result of the interaction between the various components of a

multimedia work is a significant contribution to the study of

multimedia.

Cook's own paradigm ("Models of Multimedia") is carefully

delineated in the final chapter of Part I. Here, the author sets out

his approach to the study of multimedia, interrelationshipsbetween

the various component media, and potential source(s) of the

resulting meaning(s). At its most fundamental level, this model

consists of two steps: a similarity test and a difference test. Space

limitations for the present review preclude a full description of the

model. Its essence, however, involves determining whether

component media are communicating the same basic meaning via

different perceptual modalities or whether these constituent

elements consist of varying messages. In the latter case, the listenerviewer's cognition is a more complex interpretive process. If the

media are considered to be communicating the same message, the

relationship is said to be conformant (Lakoff and Johnson's

"consistent"). At the other extreme, if the media communicate in a

manner such that the meaning of each contradicts that of the other,

the relationship is said to be one of contest. In the middle ground

between these two polar extremes of a continuum exists a

complementaryrelationship, in which the relationship is neither

consistent nor contradictory. In selecting the identifiers used to

describe these models, Cook consciously decided to coin a new set

of terms instead of using the common terms already used

frequently to describe these relationships (consistent, coherent, and

contradictory). Upon initial contact with Cook's model, I

considered this a major weakness, incorporating - what I

considered at the time- an unnecessary level of interpretation and

resulting in needless complexity. However, as I continued to use

these concepts in a classroom context and to participate in

�Review Forum: Lipscomb on Cook

233

animated discussions about the roles of the various media in a

multimedia context by all involved, I found that having such

were clearly

terms - once

their meanings

reserved

understood- actually served to facilitate the resulting discussions

and enhanced the ability to readily distinguish a variety of

meaningful interrelationships.

At this point, with the primary intent of Part I of Cook's text

clearly accomplished, it was time to enter the realm of analysis,

using specific examples from the vast repertoire available. My own

purpose in this review is not to agree or disagree with the specific

application of Cook's model to the analyses presented in Part II.

Other reviewers in the present volume will take the opportunity to

do so. I do, however, wish to take issue in a very general way with

the examples selected by Cook for the purpose of demonstrating

the appropriateness and functionality of his models. As a

musicologist, Cook has chosen explicitly to focus on multimedia

examples in which the music plays a primary role (i.e., "musical

multimedia"). As a result, each of the three selected examples (the

video for Madonna's "MaterialGirl," the "Rite of Spring sequence"

from Fantasia, and "Armide" from Arid) represents a multimedia

context in which the music predates the accompanying visual

component and dominates the multi-modal texture. Quite the

opposite of instances in which the visual image is autonomous (a

situation dealt with by the author at length in Part I of the text),

the chosen excerpts focus solely on a relationship at the opposite

extreme of the spectrum, rather than providing a variety of media

types and representativeinterrelationships. In cinema, arguablythe

most sociologically significant form of multimedia at present- and,

admittedly, the present author's primary area of research

interest- the sequence of events involved in production is quite the

opposite. Typically, though exceptions to this rule certainly exist,

the film composer is given a finished product for which she is

asked- within a phenomenally short period of time- to produce a

musical score for the purpose of enhancing the dramatic narrative.

It would seem appropriate to have included at least one excerpt

from a feature film in the set of examples for analysis, given the

significance of this artform as evidenced by box office receipts.

This is not intended to denigrate the selections of the three very

interesting pieces analyzed, each useful in its own right and quite

�234

Integral

different one from another. I question only whether- other than

the music video- they represent types of multimedia that are

exemplary to the extent that the analytical method applied to them

can be shown to be appropriate for other similar examples of

multimedia that occupy a position of high sociological significance

within our culture. I wonder if the selection of such materials

doesn't run counter to the author's stated intent to "contribute to

the current reformulation of music theory in a manner that loosens

the grip on it of the ideology of musical autonomy" (vi). Selecting

these specific types of multimedia, intentionally or unintentionally,

raises the musical component to the position of most significant

feature, upon which all others are based and/or to which they relate

specifically. Though perhaps no longer "musically autonomous,"

in the sense meant by Peter Kivy (according to Cook's own

reference), these chosen works represent- at best- music-centric

multimedia examples. To what extent does a model formulated for

the analysis of such specialized examples generalize to multimedia

artifacts in which the roles of individual components share more

equally in the emergent meaning of the piece?

Despite the minor critiques offered in these paragraphs, I

found AnalysingMusical Multimedia to be a highly informative and

stimulating read. The clarity with which Cook expresses his wellinformed ideas is exemplary, as is the manner in which he

introduces formative concepts that support the basis for his

proposed model of analysis. Though this text does not provide the

definitive guide- Cook certainly does not presume to make this

claim- to understanding or analyzing multimedia, it certainly takes

admirable strides in that direction. I found that the book served my

educational objectives extremely well in the context of the

previously referenced "Multimedia Cognition" course. It provided

an interesting and highly useful counterpoint to Chion's Audiovision and the additional selected readings intended to augment

understanding of aesthetics in general and inform students

regarding the results of empirical research investigating the

multimedia context specifically. Students responded well to the

manner in which the material was introduced and developed; this

communicated to me that Cook's proposed model facilitated their

understanding of the interrelationships between various media and

�Review Forum: Lipscomb on Cook

235

enhanced their ability to communicate about these matters clearly

and concisely.

As a music researcher, I find that my primary remaining

concern with the text echoes that previously stated by a colleague

and friend. In her review of the same text, Annabel Cohen

identifies the author's "unwillingness to endorse the cognitive

psychology experimental approach."15She goes on to state that

many of the ideas presented in the text afford a perfect opportunity

to be tested experimentally, specifically mentioning issues related to

conscious attention, cross-modal figure-ground relationships, the

effect of music on perceived synchrony, the effect of synchrony on

awareness of the music, and the effect of music on the perceived

quality of activity. Many of these topics have alreadybeen broached

in empirical work investigating the multimedia experience. In

agreement, I would argue that experimental researchin general and

the cognitive approach specifically offer the perfect tools with

which to further revise and develop Cook's set of models. Looking

to the future, I see Cook's text as a musicological "statement"made

to the interdisciplinary academic community at large to which the

community of music cognition researchers can respond with an

appropriate "answer." If I had but one wish, I would ask that this

scholarly "dance"might proceed through numerous iterations, in a

way that will afford an opportunity for dialogue and discussion

across extant disciplinary boundaries, bringing us closer to an

understanding of the processes inherent in the multimedia

experience through the systematic investigation of the intriguing

relationships proposed by Cook, supplemented by researchalready

carried out, and clarified by researchyet to come. After reading this

text and formulating its many testable hypotheses, a research

agenda could be set that would occupy the next two decades... at

least. I hope Cook's text and others like it will stimulate others to

join in the search.

15Cohen

1999:258.

�236

Integral

References

Campbell, W. and Heller, J. 1980. MAnOrientation for Considering Models of

Musical Behavior." In Handbook of Music Psychology.Edited by D. Hodges,

29-35. Lawrence, KS: National Association for Music Therapy.

Chion, M. 1990. Audio-vision: Sound on Screen. Translated by C. Gorbman.

New York: Columbia University Press.

Cohen, A.J. 1999. "Musicology Alone?" (a review of Nicholas Cook's Analysing

Musical Multimedia). Music Perception 17:247-260.

Cohen, A.J. 2001. "Music as a Source of Emotion in Film." In Music and

Emotion: Theory and Research.Edited by P.N. Juslin and JA. Sloboda, 249272. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Kendall, R.A. and Carterette, E.C. 1990. "The Communication of Musical

Expression." Music Perception8/2: 129-164.

Kerman, Joseph. 1956. Opera as Drama, 1* ed. New York: Knopf.

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press.

Longer, S.K. 1942. Philosophy in a New Key:A Study in the Symbolismof Reason,

Rite, and Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lipscomb, S.D. in press. "The Perception of Audio- visual Composites: Accent

Structure Alignment of Simple Stimuli." Selected Reportsin Ethnomusicology

12.

Lipscomb, S.D. 1995. "Cognition of Musical and Visual Accent Structure

Alignment in Film and Animation." Unpublished doctoral dissertation,

University of California, Los Angeles.

Lipscomb, S.D. and Kendall, R.A. 1994. "Perceptual Judgment of the

Relationship Between Musical and Visual Components in Film."

Psychomusicology13/1: 60-98.

Marks, L.E. 1978. The Unity of the Senses: Interrelations Among the Modalities.

New York: Academic Press.

Marshall, S.K. and Cohen, A.J. 1988. "Effects of Musical Soundtracks on

Attitudes Toward Animated Geometric Figures."Music Perception6: 95-1 12.

McGurk, H. and MacDonald, J. 1976.

Nature 264: 746-748.

"Hearing Lips and Seeing Voices."

Osgood, C.E., Suci, G.J., and Tannenbaum, P.H. 1957. The Measurement of

Meaning. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Radeau, M. and Bertelson, P. 1974. "The After-effects of Ventriloquism."

QuarterlyJournal of ExperimentalPsychology26: 63-7 1.

Staal, H.E. and Donderi, D.C. 1983. "The Effect of Sound on Visual Apparent

Movement." AmericanJournal of Psychology96: 95- 105.

Tannenbaum, P.H. 1956. "Music Background in the Judgment of Stage and

Television Drama." Audio-Visual CommunicationsReview 4: 92-101.

Thaycr, J.F. and Levenson, R.W. 1984. "Effects of Music on Psychophysiological

3: 44-54.

Responses to a Stressful Film." Psychomusicology

�Fantasia's Rite of Spring as Multimedia:

A Critique of Nicholas Cook's Analysis*

Daphne Leong

Nicholas Cook's AnalysingMusical Multimedia undertakes the

lofty task of creating "a generalized theoretical framework for the

analysis of multimedia" (v), one that moves from music to other

media (vi). The first half of the book sets out this theoretical

framework followed, in the second half, by three analytical case

studies: Madonna's "Material Girl," the Rite of Spring sequence

from Fantasia, and Godard's sequence in Aria based on Lully's

Armide.

Cook states that his case studies "do not illustrate the analytical

approach in any literal way, but rather attempt to embed its results

within the context of broader critical readings" (ix-x). One can

therefore read his case studies as a presentation of theory, analysis,

and criticism. The present essay focuses on Cook's treatmenttheoretic, analytic, and critical- of Fantasia's Rite of Spring

sequence.

The sequence exemplifies what Cook calls "music film": "a

genre which begins with music, but in which the relationships

between sound and image are not fixed and immutable but variable

and contextual, and in which dominance is only one of a range of

possibilities" (214). Cook further proposes viewing the Rite of

Spring sequence "as the construction of a fundamentally new

experience, one whose limits are set not by Stravinsky nor even by

but by anybody who watches - and listens

Disney...,

to- 'Fantasia'" (214).

This proposition, as fleshed out by Cook in the chapter,

implies among other things that (a) Fantasia's Rite is not defined by

the music from which it originated, (b) the combination of visuals

and music in Fantasia's Rite creates a new entity, and (c) this new

entity is worthy of the analytical attention that Cook devotes to it.

"

Nicholas Cook, Disney *s Dream: The Rite of Spring Sequence from 'Fantasia',"

Chapter 5 in Analysing Musical Multimedia (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2000 reprint of 1998 edition): 174-214.

�238

Intigral

I will qualify all three claims and, along the way, question certain of

Cook's analytical observationsand methodologies.

The claim that the Rite of Spring sequence provides a

"fundamentally new experience" derives from a central thesis of

Cook's book. Simply put, meaning emergesfrom the combination

of disparate media (115). Attributes are transferred from one

medium to another; the resulting combination is qualitatively

different from its constituents (84). l

In the case of Fantasia's Ritey Cook counters the assumption

that the music is primary, and the visuals merely "the projection

through ancillary media of an originary meaning" (214).

Ironically, his argument rests in part on similarities between

Fantasia and the original ballet production of The Rite of Spring.

Pointing to the close collaboration between Nikolai Roerich,

Stravinsky, and Vaslav Nijinsky during the ballet's genesis, and to

the tight interlacing of ethnography, music, and dance during

Stravinsky's compositional process, Cook argues for the intrinsic

multimedia nature of Rite, and, by implication, for the validity of

its new multimedia incarnation in Fantasia (198ff.).2 He defends

"Disney's realization of the music as the story of life" as "an

alternative metaphor to that of the pagan celebration of spring"

(206), and compares Disney's visuals to Stravinsky'schoreographic

annotations.3 I find Cook's placement of Fantasia's Rite of Spring

in the context

of the original

Stravinsky-Nijinsky

choreography particularly his comparison of Rites rhythmic

structure, Stravinsky's choreographic annotations, and Fantasia's

visualization of the score on several levels- fascinating, and one of

the strongest contributions of his analysis.

Yet Cook's contention that Fantasia's Rite of Spring sequence

constitutes a new entity fails to persuade. Indeed, negative musiccritical reaction to the film focused on the lopsidededness of its

Lawrence Zbikowski's review-essay in this volume describes the theory of

"conceptual blending," which explores and formalizes this notion of emergent

concepts.

Others have presented evidence for the intertwining of ethnography, music, and

dance in the creation of Rite. See, for example, Taruskin 1984, also Taruskin

1995 and Pasler 1986.

As transcribed in Stravinsky 1969.

�Review Forum: Leong on Cook

239

music and animation, on the failure of its two media to cohere.

According to critic Olin Downes, "Stravinsky's'Sacre' is a piece of

music almost as difficult as that of Bach to visualize in any way that

corresponds to the inherent quality of the score;" this in contrast

to Fokine's choreography of Rimsky-Korsakov's Schihe*razade>

which "magnificently companioned the music. The point here is

that while the music was not slavishly followed, it was represented

essentially by a companion creation of a parallel character which

completed and did not belie the nature of the score."4

The notion of image and sound as a united whole has a long

history in film theory. Rudolf Arnheim, for example, exploring

questions of multimedia in 1938, emphasized both difference at a

surface and unity on a deeper level: "...elements conform to each

other in such a way as to create the unity of the whole, but their

separatenessremains evident." "...a combination of media that has

no unity will appear intolerable."5 A history of this "need for

unity, totality, continuity, fusion of some form among disparate

elements" is traced by Scott Paulin, who states that "in addition to

the need to create the impression of internal unity within both the

imagetrack and the soundtrack separately, the two tracks must also

cohere so as to invite perception as a unified whole. Sound and

image must bear some relation of appropriateness or 'realness' to

each other...."6

Fantasia's Rite of Spring sequence presents a wide chasm

between music and image. Disney's animation and Stravinsky's

score (or Stokowski's soundtrack) simply do not match well in

terms of artistic quality and depth. Their juxtaposition creates, not

a "fundamentally new experience," as Cook would have it, but an

uneasy amalgamation of cartoon and sound. For those acquainted

with Stravinsky's score, at least, the music looms large over the

supposedly new creation that is Fantasia.

A slight aside is in order here about the music in Fantasia's

Rite. The soundtrack of Fantasia's Rite departs from Stravinsky's

intentions in several obvious respects. As Cook states, Disney's

team cuts sections of the score, reorders it, and reorchestratesit in

4

Downes 1940.

5 Arnheim

1957: 207, 201.

6

Paulin2000: 63-64.

�240

Integral

parts.7 Conductor Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia

OrchestradepartsignificantlyfromStravinsky's

tempoindications.

I now turn to some detailsof Cook's analysis. My discussion

focuses on Cook's applicationof three theoreticalconcepts: the

associationof accentuationwith coincidence of visual and aural

"cuts,"Pietervan den Toorn's Type I and II rhythmicstructures,

and Andrew Imbrie's "conservative"and "radical"hearings of

metricstructure.

(1) Accentuationand coincidenceof visualandauralcuts

Cook's Figure 5.2 diagramsthe Rite of Springsequencefrom

104 to 117, showing blocks of musicalmaterial,largergroupsof

these blocks, and placeswherevisualcuts align with beginningsof

musicalblocks. u...[T]here is a contrastbetweenthe groupsthat

are characterized

by cuts at the beginningsof blocks(I and III) and

those that are not (II and IV); these coincidencesestablishwhat

might be termedaudio-visualdownbeats.The resultis that groups

I and III create the effect of being accented as comparedwith

groups II and IV, giving rise to a kind of large-scaledownbeatafterbeatpattern;groupII constitutesa kind of prolongedafterbeat

followingon the initialgroupI, while the moreextendedgroupIV

follows on from the composite downbeatformed by the second

groupI and groupIII"(184).

This analysismissesseveralimportantfeatures. Cook's group

IV segments into two parts,which I will call IVa (114) and IVb

(115 to end of 116); the beginning of group IVb is clearly

articulatedby a changein orchestrationat 115. Cook ignoresthis

change, implicitlygroupingall of 114 to the first measureof 115

Cook suggests a rationale for Disney's reordering of the score (176-177); it is

interesting to note that the reordering also parallels the palindromic plan of the

animation. Disney orders parts of Stravinsky's score as follows: Introduction to

Part I- first part of Part I ("Augurs of Spring," "Ritual of Abduction")- most of

Part II (all but the "Sacrificial Dance") - last part of Part I ("Kiss and Dancing

Out of the Earth")- Introduction to Part I, corresponding roughly to the visual

plan space- earth- life- earth- space. (Cf. Cook Figure 5.5.) Both plans are

palindromic.

�Review Forum: Leong on Cook

241

together, as "the six successive appearances of block V from 114,

...enlivened by means of a relatively autonomous visual structure"

(184). The visual structure is actually not particularlyautonomous;

it aligns with Stravinsky's alternating 5/4 - 6/4 bars (Cook's

alternating el 0-1 2). As shown in my version (Example lb) of the

end of Cook's Figure 5.2 (Example la), a visual cut that Cook

misses at 114+2 completes a clear pattern of visual cutting at the

beginning of every 5/4 measure (Cook's elO's).

Examplela. Cook'sFig. 5.2 "AnalyticalOverviewof the

Fight Sequence"(last line) (183).

114

115

116

IV 103

I

I

|elO

12

10

12

10

|1O

|f6

el2

f4

e6

f6

g5

Examplelb. Revisionof Cook'sFig. 5.2 (last line).

114

115

116

IVa

IVb

I

II

|elO

12

|1O

t

12

|10

I

10

|f6

el2

jf4

t

e6

|f6

g5

t

Furthermore, a closer look at group IVb shows that important

visual changes occur at the beginning of every f block. At 115+1,

as Cook notes, a visual cut marks the beginning of f6; but at 115+3

and 116+1, unmentioned by Cook, significant visual changes

(Stegosaurus tail hits Tyrannosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus bites

Stegosaurus and holds, notated in Example lb with dotted vertical

lines) coincide with the beginnings of blocks f4 and f6 respectively.

�242

Integral

The latter two 'changes of scene/ while not cuts per se, accomplish

functions analogous to cuts. By marking the beginning of each f

block, they create the effect of an alternation of upbeats (e blocks)

and downbeats (f blocks).

Thus, even accepting Cook's assertion that coincidence of

visual and aural cuts results in "accented" groups,8 a more

consistent reading based on this criterion would be: I (accented) II (unaccented) - I and III (accented) - IVa (accented) - IVb

(somewhat accented?). Cook, however, wishes to divide the

passage into two parallel sections I-II and I/HI-IV; interpreting IV

as unaccented supports the parallelism of his reading. Other

features contribute to a sense of group IVa as unstressed- it has a

lower dynamic level and lighter orchestration than preceding

material- but any unstressed quality is not due to lack of

coincidence between visual and auralcuts.

(2) Pieter van den Toorn's Type I and II rhythmic structures

In his monograph on the Rite of Spring, Pieter van den Toorn

proposes two prototypical types of rhythmic structure. Type I

consists of irregular or shifting meter, with alternations of

contrasting material delimited by bar lines; all concurrent

instrumental parts synchronize metrically. Type II displays

foreground metric regularity (usually a steady meter), but

superimposes two or more repeating motives whose periodicities

differ from one another.9

Cook terms the opening of "Augursof Spring" from 13 to 22

Type I, arguing that, rather than Stravinsky'snotation in 2/4 meter

with cross-metric accents, the passage could well be notated in

changing meters (presumably 9/8 - 2/8 - 6/8 - 3/8 - ... ) (187188). Several objections can be raised to this interpretation.

I would prefer a different term, since accentuation more precisely occurs at

points in time, not over extended passages. Imbrie 1973: 52-54; Benjamin 1984:

379; and Lester 1986: 16 attribute accent to time points, rather than time-spans.

Schachter 1987: 6; Hasty 1997: 16-17, 103-104; and Berry 1985: 30 attribute

accent to events, but describe it as focused on a particular point within an accented

event. Imbrie 1973: 54 suggests the term "weighting" for cases in which "an

important downbeat accent ... impart[s] a generalized sense of greater heaviness to

an entire rhythmic unit." See Leong 2000: 39 for further discussion of this issue.

9

Van den Toorn 1987: 97-1 14; see especially 99-100.

�Review Forum: Leong on Cook

243

Elsewhere, Stravinsky clearly emphasizes the significance of his

notated meters, and the difference between his bar lines and accent

markings;10 renotating these cross-accentsas changing meters alters

their sensibility drastically. Furthermore, preceding, interspersed,

and overlying material (12+8 to 12+9, 14 to 14+3, and 15+1 to

u

And

15+5 respectively) unambiguously articulates 2/4.

subsequent material, at 16, displays characteristics of Type II

structure: 2/4 in English horn and viola plays against an offset 2/4

in oboe and 3/8 in the lower strings. When a metric structure

similar to that at 16 appears at 28, Cook calls it a "textbook

example" of Type II (189). Thus Cook's labeling of the passage

from 13-21 as Type I is questionable at best.

(3) Andrew Imbrie's "conservative"versus "radical"hearings

Cook's appropriation of Andrew Imbrie's terms "conservative"

and "radical"suffers throughout from subtle misinterpretations of

their meaning. According to Imbrie, a conservative listener

maintains the established meter for as long as possible in the face of

conflicting evidence; a radical listener "converts" quickly when

presented with evidence of changing meter.12 According to Imbrie

via van den Toorn via Cook, "'radical'readings [are] based purely

on surface rhythms," while "'conservative' readings [emphasize]

underlying metrical continuity" (187). The main difference

between radical and conservative listeners, however, lies not in their

compliance with surface rhythm versus metrical structureper se>but

in the speed with which they adapt to the changing metric

implications of surface rhythms.

Two examples follow to illustrate the misunderstanding. The

first continues our discussion of the passage from 13 to 22.

In Stravinsky

andCraft1959:21, Craftasks,"Canthesameeffectbe achieved

by means of accents as by varying the meters? What arc bar lines?*, to which

Stravinsky replies, "To the first question my answer is, up to a point, yes, but that

point is the degree of real regularity in the music. The bar line is much, much

more than a mere accent, and I don't believe that it can be simulated by an accent,

at least not in my music."

Van dan Toorn 1987: 69-70 describes 13 in terms of the continuation of the

previously established 2/4 meter, its disorientation, and its reestablishment at 14.

Imbrie 1973; see especially 65. The concept has been adopted by van den

Toorn (1987: 67 ff.); and Lcrdahl and Jackendoff ( 1996: 22-25); among others.

�244

Integral

Beginning at 18, Stravinsky reinterprets the material beginning at

13: the eight measures of 18 repeat those of 13, but unlike the

material at 13, which is followed by straightforward 2/4 meter at

14, that at 18 leads to 2/4 meter shifted by one eighth note at 19.

Beginning at 19, the accented melodic entrances on the second

eighth note of the measure, combined with the accompaniment

accents and dynamic changes at the same metric position, make it

extremely difficult for the listener to maintain the previouslyestablished notated 2/4 meter. Even the most "conservative" of

listeners would be hard put to avoid converting to the shifted 2/4

meter articulatedby so many musical cues.

Disney's visual cuts make the same shift. From 13 to the end

of 18, the primary visual cuts, as Cook notes, coincide with the

downbeat of each new block. (I prefer to say that the cuts align

with the beginnings of musical blocks, which happen to occur on

downbeats.) At 19, the musical blocks shift, at least aurally, to

begin on the second eighth of the measure. Here Disney follows

the aural cues, aligning visual cuts with the aural cuts on the second

eighth of the measure.

Cook calls the animation of this passage "predominantly

'radical'" (188), because of its alignment with surface patterning.

This description is incorrect, because a radical reading implies

shifting sooner rather than later, shifting on the basis of lesser

rather than greater evidence. Disney's visual cuts shift to the

second eighth note only when the musical evidence makes it

difficult to avoid shifting; they follow the preponderance of

musical cues, ratherthan anticipating them.

Cook's analysis of the latter part of "Augurs of Spring," from

28 to its end, displays a similar misunderstanding of Imbrie's terms.

Essentially, Cook argues that visual cutting rhythms serve first to

reinforce four-bar periodicity, and then to play against it. His

Figure 5.4 shows cutting rhythms in the passage, and, as far as I can

tell, is inaccurate. Examples 2a and 2b show Cook's Figure 5.4 and

my revision of it.

The inaccuracies do not alter Cook's argument much, except

that the "cut on the hyperdownbeat at 31+4" actually falls an

eighth after the hyperdownbeat, coinciding with the syncopated

horn entrance, and there is an additional coincidence of visual cut

and hypermetric downbeat, at 32+4. At 31+4 the cuts do start out

�Review Forum: Leong on Cook

245

supporting the hypermeter (albeit one eighth late at the beginning),

and then begin cutting against the music's four-measureunits. But

one cannot, as Cook does, describe this process as a conservative

hearing migrating to a radical one. A radicalhearing implies a shift

in listening stance commensurate with changes in musical surface,

from an established meter to a new meter, or from an established

meter to changing motivic metric identities. After 32+4 the cuts

do not follow musical metric, grouping, or motivic structure; they

create their own largely independent rhythm. They cannot be

interpretedas a visualization of a radicalhearing of the music.

Example2a. Cook'sFig. 5*4 "CuttingRhythmsin

The Augursof Spring'"(190).

28

29+1

30

31+4

8

8

15

15

14

6

9

33+2

6

7

35+2 36+2

6

7

5

3

4

3

Example2b. Revisionof Cook'sFig. 5*4.

28

29+1

30

88

31

15

14

6

31+4

32+4

li£

2£

34+2

6651

7

7

3

3

In his description of methodology for the analysis of

multimedia (133-146), Cook suggests experiencing each medium

on its own, and comparing this effect to the medium's effect in the

totality, or in pairs of media; when interpreting media pairs, he

proposes inverting relations (reading from one to the other),

reading for gaps, and using "distributionalanalysis." In this list of

methodologies, Cook, though he mentions music-specific analytical

methods such as Schenkerian analysis, makes no mention of visualspecific tools. This may be one result of his orientation from

"music-to-other-media," his attempt to "extend the boundaries of

�246

Integral

"

music theory to encompass... words and moving images... (vi).

Nevertheless, a music theorist would be rightly dubious of a film

theorist making analytical claims about precise alignments of

musical metrical structure and visual cuts without recourse to the

musical score; and Cook, though he makes frequent reference to

the score of Rite, makes no reference to frame-by-frameanalysis or

to other visual tools beyond simple viewing.

Furthermore, in his discussion of visual rhythmic structure,

Cook relies heavily upon cutting rhythms. He makes little mention

of rhythms articulated by analogous changes in visual content.13

His discussion of the Tyrannosaurus/Stegosaurus fight scene, for

example, as mentioned earlier, overlooks the rhythmic articulation

created by visual changes (not cuts) in group IVb.

>

The Rite of Spring sequence features in Cook's Analysing

Musical Multimedia as an illustration of his theory of multimedia.

The connections between the theory and Cook's analysis are rather

broadly drawn; some readers might wish to see more rigorous

connections

between Cook's explication of conformance,

complementation, and contest, and his analytical chapter on

Fantasia}*

The Rite of Spring sequence does illustrate contest,on a deeper

level than that envisioned by Cook.

The two media

involved Disney's animation and Stokowski's performance of Rite

I am speaking of changes akin to cuts, without actual filmic cutting. Cook does

discuss alignments of surface musical activity with visual gestures such as shooting

stars, volcanic puffs of flame, and Tyrannosaurus snaps, as well as with kinesthetic

motions such as swooping pterodactyls and "jogging dinosaurs" (182).

Furthermore, I am referring primarily to intermediate levels of rhythmic structure;

Cook does explore large-scale form created by the chronological narrative and its

symmetrical plan space-earth-life-earth-space, by color associations, and by camera

or diegetic motion (193-196).

See Cook (98-106) for his presentation of these terms. In a nutshell,

conformancerefers to media consistent with one another, without "differential

elaboration;" complementationentails media similar to one another, yet differing in

significant ways; contest "implies an element of collision or confrontation between

the opposed terms" (102).

�Review Forum: Leong on Cook

247

of Spring- juxtapose "popular" art with "elite" art. The two

contradictory views come to the fore in statements by Disney and

Stravinskyrespectively:

Stravinsky saw his Rite of Spring and said that that was what he had in mind all the

time. None of that matters, I guess. This isn't a picture just for music lovers.

People have to like it. They have to be entertained. We're selling entertainment

and that's the thing I'm hoping Fantasia does- entertain.

When Walt Disney used Le Sucredu printemps for Fantasia, he told me: "Think of

the numbers of people who will now be able to hear your music." Well, the

•numbers of people who consume music... is of no interest to me. The mass adds

nothing to art. It cannot raise the level, and the artist who aims consciously at

mass appeal can do so only by lowering his own level. The soul of each individual

who listens to music is important to me, not the mass feeling of a group. Music

cannot be helped by means of an increase of the quantity of listeners, be this

increase affected by the film or any other medium. It can be helped only through

an increase in the quality of listening, the quality of the individual soul.

What is at issue, as emerges from Stravinsky'sstatement, is not so

much "popular"versus "elite," as it is "the level" and "quality"of

the artisticvision, its execution, and its reception.

Cook bases his models of multimedia on George Lakoff and

Mark Johnson's model of metaphor.17The defining feature is "a

distinctive combination of similarity and difference" (98). Cook

assumes a basic level of similarity which, if one is to follow his basis

in metaphor theory, means that the constituent expressions must be

close enough to "fit together," to form a metaphor. For some

readers, the metaphoric link, so to speak, between Disney's

animation and Stravinsky's score or Stokowski's performance may

be quite tenuous.

In his development of the concept of contest,Cook writes that

"each medium strives to deconstruct the other, and so create space

for itself. Any IMM [instance of multimedia]18in which... one or

more of the constituent media has its own closure and autonomy is

likely to be characterized by contest; IMMs that involve the

15

Walt Disney, quoted in Culhanc 1983: 29.

16

Stravinsky 1946: 35-36.

17

Lakoff and Johnson 1980.

Cook abbreviates his term "instance of multimedia" as IMM (100).

�248

Integral

addition of a new medium to an existing production are a

particularlyrich source of examples"(103).

This description would seem to be aproposof Fantasia'sRite of

Spring sequence. But Cook argues that the sequence's overall

relationship of visuals and sound is one of conformance. He

describes the close synchronization of image and music on the

film's surface, the 'contrapuntal' relationships of cutting rhythms

and hypermetrical patterns at intermediate levels, and the creation

of "a single filmic gesture... which reaches from the opening space

sequence right up to the dawn of life" (196) on a large scale. "The

result of all this is that music and visualization stack up into a single

hierarchy whose highest level is visual. And in this way, what

might be called the background model of the Rite sequence from

'Fantasia'is an unambiguous conformance''(208).

Elsewhere Cook shows how conformant relations at more

surface levels can contribute to conflicting relations at a deeper level

(181-182). Although Fantasia'sRite of Springsequence can be seen

as conformant on its surface and even deeper levels, the

combination of Disney's particular choice of animation with

Stokowski's performance is ultimately conflicted, in terms of

aesthetic caliber.

Stravinsky describes the problem of surface conformance versus

deeper compatibility as follows:

The danger in the visualization of music on the screen- and a very real danger it

is- is that the film has always tried to "describe" the music. That is absurd.

When Balanchine did a choreography to my "Danses Concertantcs" (originally

written as a piece of concert music) he approached the problem architecturallyand

not descriptively. And his success was extraordinaryfor one great reason: he went

to the roots of the musical form, of the jeu musical, and recreated it in forms of

movements. Only if the films should ever adopt an attitude of this kind is it

possible that a satisfying and interesting art form would result.19

And later in the same interview:

...my ideal is the chemical reaction, where a new entity, a third body, results from

uniting two different but equally important elements, music and drama; it is not

the chemical mixture where. . .nothing either new or creative [results]."20

19

Stravinsky 1946: 35.

Ibid.

20 TL'j

�Review Forum: Leong on Cook

249

The Rite of Spring sequence in Fantasia forms not a "chemical

reaction," but a "chemical mixture." For although, as Cook argues,

Fantasia may be a "fundamentally new experience" that constructs

new meaning through the combination of its constituent parts, it

remains a combination and not a coherent whole; it remains

aesthetically unsatisfying. And so, Cook's analysis, in its choice of

IMM for analysis, must also be unsatisfying, in analyzing an IMM

that conforms on many levels yet fails to cohere on the deepest,

aesthetic level.21

References

Arnhcim, Rudolf. 1957. "A New Laocoon: Artistic Composites and the Talking

Film" (original in Italian in Bianco e Nero 1938). Translated in Arnhcim,

Film as Art. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Benjamin, William. 1984. "A Theory of Musical Meter." Music Perception 1/4:

355-413.

Berry, Wallace. 1985. "Metric and Rhythmic Articulation in Music." Music

TheorySpectrum7: 7-33.

Culhane, John. 1983. Walt Disney'sFantasia. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Downes, Olin. 1940. "Disney's Experiment: Second Thoughts on 'Fantasia' and

Its Visualization of Music." New YorkTimest 17 November.

Hasty, Christopher. 1997. Meter as Rhythm. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Imbrie, Andrew. 1973. "'Extra' Measures and Metrical Ambiguity in Beethoven."

In BeethovenStudies 1, ed. Alan Tyson. New York: Norton.

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Leong, Daphne. 2000. "A Theory of Time-Spaces For the Analysis of TwentiethCentury Music." Ph.D. diss., Eastman School of Music, University of

Rochester.

Cook explains in his Preface (x) that he chose case studies largely on the basis of

general availability. Another fairly obtainable "music film," and one that, I think,

would provide a much more satisfying "chemical reaction" for analysis, is Chuck

Jones' What's Opera, Doc? Like Fantasias Rite, this short takes a "classical"and

originally multimedia work, Wagner's Ring, as a point of departure. Unlike

Fantasia, it makes no claim to fidelity to the original, but freely snips, arranges,

and adds sound effects, voices, and lyrics. However, the quality of the animation

and the creative vision of the director in this example, unlike in Fantasia's Rite,

result in a truly new entity of image and sound.

�250

Integral

Lcrdahl, Fred and Ray Jackcndoff. 1996 reprint of 1983. A Generative Theoryof

Tonal Music. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lester, Joel. 1986. The Rhythms of Tonal Music. Carbondale: Southern Illinois

University Press.

Pasler, Jann. 1986. "Music and Spectacle in Pctrushka and The Rite of Spring."

In Confronting Stravinsky: Man, Musician, and Modernist, ed. Pasler.

Berkeley. University of California Press.

Paulin, Scott. 2000. "Richard Wagner and the Fantasy of Cinematic Unity: The

Idea of the Gesamtkunstwerkin the History and Theory of Film Music." In

Music and Cinema, ed. James Buhler, Caryl Flinn, and David Neumeyer.

London: Wcsleyan University Press.

Schachter, Carl. 1987. "Rhythm and Linear Analysis: Aspects of Meter." Music

Forum VI: 1-60.

Stravinsky, Igor. 1946. "Igor Stravinsky on Film Music, as told to Ingolf Dahl."

Musical Digest 28/ 1 (September): 4-5, 35-36.

. 1969. "The Stravinsky-Nijinsky Choreography." Appendix III in The

Rite of Spring:Sketches1911-1913. [London]: Boosey and Hawkes.

Stravinsky, Igor and Robert Craft. 1959. Conversations with Igor Stravinsky.

Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

Taruskin, Richard. 1984. "The Rite Revisited: The Idea and the Sources of its

Scenario." In Music and Civilization: Essaysin Honor of Paul Henry Lang, ed.

Edmond Strainchamps and Maria Rika Maniates. New York: W.W. Norton.

. 1995. "A Myth of the Twentieth Century: The Rite of Spring, the

Tradition of the New, and 'The Music Itself." Modernism/Modernity111: 126.

van den Toorn, Pieter. 1987. Stravinskyand The Rite of Spring: The Beginning of a

Musical Language. Berkeley, University of California Press.

�Music Theory, Multimedia, and the Construction of

Meaning

Lawrence M. Zbikowski

In the summer of 1938, as the storm clouds of war were

gathering across Europe, Sir Donald Tovey delivered a lecture to

the British Academy entitled "The Main Stream of Music." The

lecture is a curious affair, not the least because for Tovey the

mainstream of music was a thoroughly Germanic one. While

sensitive to the accomplishments of non-German composers in the

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Tovey nonetheless believed

there was a sea change in musical composition in the early

eighteenth century: "With the advent of Bach, music became an art

so congenial to all that is best in the Teutonic intellect that for the

next two centuries there is no musical art-form in which German

musicians have not produced the supreme masterpieces."1 And it

was the genius of Bach that discovered resources within music

which rendered the medium independent of other media. Tovey

continues, "There can be no supreme musical art without the

qualities of absolute music, whether the art be as compounded with

other arts as Wagnerian opera or as exclusively musical as the string

quartets of Beethoven." The mainstream of music, then, was one

flooded by the works of German composers, works whose

excellence relied on the purely musical.

This conclusion caused Tovey some anxiety. Indeed, both his

long-held belief that music could speak to a broad audience, and

his tireless championing of British music, were challenged by a

central corpus of thoroughly German works that required neither

text nor program for their understanding. But a deeper source of

his anxiety was a nagging suspicion that musicians were in danger

of losing their way. Some pages later, after having drawn his survey

to a close with a brief contemplation of Wagner's enormous operas,

1

Tovey1938:128.

�252

Integral

he writes aI can go no further. At the present day all musicians feel

more or less at sea, and not all of us are good sailors."2

Sixty-five years later one can only look with envy on the

navigation problem that confronted Tovey, for his mainstream is

now regardedby most as but a tributary, if a significant one, to the

vast body of music through which scholars must find their way.

This challenge to navigation is, in less metaphorical terms, a

challenge to musical analysis, for analysis is one of the fundamental

ways musicians chart their course through challenging or unfamiliar

repertoire. And one seldom finds a repertoirethat presents as many

challenging or unfamiliar problems as does musical multimedia, for

the various ways music can combine with words or images yield

phenomena that are often beyond the reach of our usual analytical

tools. Indeed, as Nicholas Cook argues in Analysing Musical

Multimedia, confronting multimedia opens up basic issues within

the theory and analysis of music, and suggests a thorough reevaluation of the entire enterprise. As Cook notes, "What begins as

an analysis of musical multimedia, then, turns ineluctably into an

analysisof analysis"(viii).

The analysis of analysis begins not with the somewhat

shopworn questions of what counts as analysis and why one should

do it, but with the issue of musical meaning, for the assumption

that music means somethingis basic to musical multimedia. This is

not to say that musical meaning is theorized in any profound way

by those who create musical multimedia, only that these

practitioners realize that a television commercial or a film means

something quite different when the music is taken away or

substantially altered. Thus, while music often occupies a place well

below the obvious story-line within these media, its contribution is

not inconsequential- as Cook observes, "Music transfers its own

attributes to the story-line and to the product; it creates coherence,

making connections that are not there in the words or pictures; it

even engenders meanings of its own" (20). This leads Cook to the

somewhat startling conclusion that music in the abstract- Tovey's

"absolutemusic"- doesn't have meaning.

2

Tovey1938:139.

�Review Forum: Zbikowski on Cook

253

What it has, rather, is a potential for the construction or negotiation of meaning in

specific contexts. It is a bundle of generic attributes in search of an object. Or it

might be described as a structured semantic space, a privileged site for the

negotiation of meaning. And if, in the commercials, meaning emerges from the

mutual interaction of music, words, and pictures, then, at the same time, it is

meaning that forms the common currency among these elements- that makes the

negotiation possible, so to speak. (23)

Cook goes on to argue that the same holds true for the words

and music in songs, and the words about music in analytical

prose- in all cases, the meaning that is produced is a consequence

of interactions between various media. Musical culture is, in

consequence, irreducibly multimedia in nature (23). Analysis must

perforce deal not only with the interaction between musical

elements but also with the interactions between media, for these

interactions are basic to the construction of meaning.

The interactions between media that Cook sees as most

important are oppositional in nature- what is significant is not

how media are like one another, but how they are differentfrom

one another. This sense of discrete media that in some way interact

is, Cook argues, what separates the experience of multimedia from

synaesthesia. At the same time, the most compelling examples of

multimedia are not simply the consequence of the coincidence of

two discrete forms of communication. What is required is a limited

intersection of attributes between the constituent media- what

Cook calls an enabling similarity- which allows the media to be

brought together into the same conceptual domain so that their

differences can be noted and thus made accessible for the

construction of meaning.3

This notion of domains that are in some respectssimilar which

are brought into a correlation that reveals their differences brings

Cook to the theory of metaphor first proposed by George Lakoff

and Mark Johnson in the early 1980s.4 In the following, I would

like to explore the contemporary theory of metaphor in just a bit

more detail than Cook is able to do in Analysing Musical

Multimedia. Further developments of this theory offer ways to

A similar perspective, developed from research in psychology, can be seen in

Gentncr and Markman 1994 and 1997.

4

LakofFand Johnson 1980.

�254

Integral

streamline a few aspects of Cook's account of multimedia, and

extensions to the theory offer a somewhat more systematic

approach to the analysis of multimedia in particular, and music in

general.

The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor

Lakoff and Johnson's point of departure was the proposal that

metaphor was not simply a manifestation of the figural use of

language to create colorful if imprecise images but reflected a basic

structure of human understanding.5 For instance, in speaking

about a person's romantic relationships we might use expressions

such as aHe is known for his many rapid conquests" or "She is

besieged by suitors." The linguistic metaphors central to these

expressions are based on the conceptual metaphor LOVEIS WAR,

which correlates the conceptual domain of romantic love with the

conceptual domain of warfare. Once this correlation is active we

can access concepts drawn from the domain of warfare ("rapid

conquests," "besieged") to characterize aspects of individuals'

romantic relationships. More generally, WAR serves as a source

domain, providing a rich set of structures that we can map onto the

target domain of LOVE.Thus "quickly bringing an enemy to

defeat" is used to structure our understanding of a situation in

which an individual is able to cause other individuals to direct their

affections only to him, and to do so with little effort: "He is known

for his many rapid conquests."

One question raised by this approach to metaphor was of the

ultimate grounding of the process of mapping structure from one

domain onto another. Even if we grant that we understand a target

domain (such as LOVE)in terms of a source domain (such as WAR),

how is it that we understand the source domain in the first place?

Mark Johnson answered this question by proposing that meaning

was grounded in repeated patterns of bodily experience, which give

Expanded versions of the discussion that follows, along with more extensive

citations to recent work on metaphor theory, can be found in Zbikowski 1998 and

Zbikowski 2002: 65-71.

�Review Forum: Zbikowski on Cook

255

rise to what he called image schemata.6 An image schema is a

dynamic cognitive construct that functions somewhat like the

abstract structure of an image and thereby connects together a vast

range of different experiences that manifest this same recurring

structure. Thus our understanding of a source domain like WARis

grounded in image schemata such as BLOCKAGEand

COUNTERFORCE;

these, together with evaluative judgments such as

"winning" and "losing," provide a rich conceptual structurewhich

can then be mapped onto domains such as LOVE.

Although the theory of image schemata provides a way to

explain how cross-domain mapping is grounded, it does not explain

why some mappings are more felicitous than others. For instance,

we could map structure from the domain of WARonto the domain

to produce statements like "The G4

of PITCH RELATIONSHIPS

vanquished the FI4." But if we simply want to describe how one

pitch relates to another this seems a bit much- we tend to prefer

IN PHYSICAL

SPACE:

mapping from the domain of ORIENTATION

"The G4 is higher than the ¥14." To account for why some

metaphorical mappings are more effective than others, George

Lakoff and Mark Turner proposed that such mappings are not

about the impositionof the structure of the source domain on the

target domain, but are instead about the establishment of

correspondences between the two domains. These correspondences

are not haphazard, but instead preserve the image-schematic

structure latent in each domain. Lakoff and Turner formalized this

perspective with the Invariance Principle, which Turner states as

follows: "In metaphoric mapping, for those components of the

source and target domains determined to be involved in the

mapping, preserve the image-schematic structure of the target, and

import as much image-schematic structure from the source as is

consistent with that preservation."7 Our mapping of orientation in

physical space onto pitch thus relies on correspondences between

the image-schematic structure of components of the spatial and

acoustical domains. Both space and the frequency spectrum are

continua that can be divided into discontinuous elements. In the

spatial domain, division of the continuum results in points; in the

6

Johnson1987.

7Turner1990:

in original.SeealsoLakoff1990.

254;emphasized

�256

Integral

acoustic domain, it results in pitches. The mapping thus allows us

to import the concrete relationships through which we understand

physical space into the domain of music and thereby provide a

coherent account of relationships between musical pitches. In

contrast, mapping from the domain of WARonto the domain of

PITCHRELATIONSHIPS

works less well because it does not preserve

the image-schematic structure of the target domain (our sense that

the frequency spectrum is a continuum is almost completely

suppressed) and because it imports structure (notions based on

BLOCKAGE

and COUNTERFORCE)

foreign to the target domain.8

According to the contemporary theory of metaphor, then,

metaphor is a basic cognitive capacity that involves mapping

structure from one domain onto another. This mapping is possible

because there are aspects of the structure of each domain that are

invariant- these are the enabling similarities that Cook suggests are

a precondition for musical multimedia. Thus, in the case of

Schoenberg's Die gliickliche Hand (discussed by Cook on pp. 4156), the "Lighting Crescendo" that occurs in bars 125-53 relies on

shared structure between the music, lighting, and action on the

stage. As the musical materials get louder and coalesce the lighting

gradually goes from dull red through a variety of hues until it

becomes a glaring yellow, and the central character moves from a

portrayal of exhaustion through stages that lead to a portrayal of

extreme tension. The basic structure that unites these three

domains relies on the notion of gradually increasing energy. The

instantiation of this structure in each domain makes it possible for

the media to combine; because the structure is instantiated

differently within each domain the result of the combination is

w«/tfmedia. An increase in energy such as that portrayed by the

actor might well be soundless, but here it is accompanied by a

crescendo and the emergence of musical themes from an inchoate

background; that same increase in energy might well play out

within consistent lighting, but in Schoenberg's conception it begins

in murky gloom and ends in the bright light of day.

Note, however, that if our concern were tonal relationships as opposed to pitch

relationships a mapping from the domain of WAR might be completely

appropriate. See Burnham 1995, Chap.l.

�Review Forum: Zbikowski on Cook

257

The perspective provided by metaphor theory leads Cook, at

the conclusion of the first part of his book, to propose three basic

models for multimedia. The models are shown on Example 1,

which places them along a continuum which focuses on the relative

degree of similarity among the constituent media of an instance of

multimedia, or IMM. Leftmost on the diagram is the conformance

model, distinguished by the large number of similarities that obtain

between the constituent media of an IMM. Differences between

the media are thus relatively attenuated, and in extreme cases a