�NEW APPROACHES

TOWARD RECORDING,

PRESERVING AND STUDYING

CULTURAL HERITAGE IN DIVIDED

CYPRUS:

PROBLEMS & OPPORTUNITIES

�ISBN: 978-605-70810-3-2

NEW APPROACHES

TOWARD RECORDING,

PRESERVING AND STUDYING

CULTURAL HERITAGE IN DIVIDED CYPRUS:

PROBLEMS & OPPORTUNITIES

First print: May 2023, ARUCAD Press, 2023, Kyrenia

Publisher Certificate No: 51959

Publication Director

Oya Silbery

Cover design

Melis Dağgül

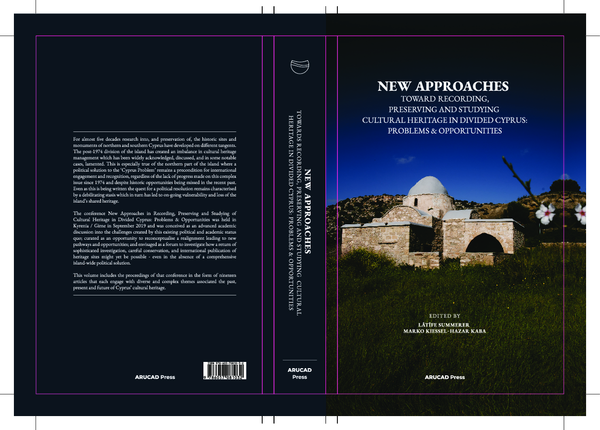

Cover image

Church Panagia Kyra

Book design

Fatma Irem Erol

Print and binding

Acar Basım ve Cilt San. Tic. A.Ş.

Bsi, Birlik Cad. No: 26, Acar Binası

Haramidere/Beylikdüzü-İSTANBUL

Tel: +90 (0212) 422 18 34

Sertifika No: 44977

The authors are responsible for the articles.

Copyright 2023 by ARUCAD Press.

All rights reserved.

This book or any portion there of may not be reproduced or used in any manner

whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher and authors

except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Arkin University of Creative Arts and Design

Şair Nedim Sokak, No: 11, Kyrenia, Cyprus

Tel: +90 (0392) 650 65 55

www.arucad.edu.tr

Distribution: info@arucad.edu.tr

ARUCAD Press, an institution of the Arkin University of Creative Arts and Design.

�NEW APPROACHES

TOWARD RECORDING,

PRESERVING AND STUDYING

CULTURAL HERITAGE IN DIVIDED

CYPRUS:

PROBLEMS & OPPORTUNITIES

Edited by

Lâtife Summerer

Marko Kiessel – Hazar Kaba

ARUCAD Press

�In memoriam

Rıza Tuncel

(1971-2022)

�Contents

Introduction

The Cultural Heritage Question within the Cyprus Dispute: Law,

Policy and Reconciliation

Alexander Gillespie

In Fear of Blacklisting. How the Division Shaped Archaeology in Cyprus

Lâtife Summerer

Between Rejection and Coping -Do Turkish Cypriots Have the Right to

Conduct Archaeological Research?

Hazar Kaba

9

15

33

87

Politics and Monuments in Cyprus: Dilemma or a Way Out?

Dimitris Michalopoulos

123

Utilizing Soft Power for Managing Cultural Heritage in Cyprus

Naciye Doratlı

137

The Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage: An Alternative Model

for Solving the Problems in the Field of Cultural Heritage

Ali Tuncay

Alashia Reborn?: Replicating and “Repatriating” Heritage in Cyprus

Leticia R. Rodriguez

From Excavation to Exhibition Problems in the Conservation of

Archaeological Objects from Excavations in Cyprus

Marie-Louise Winbladh

Architectural Conservation in Northern Cyprus: An Overview of the

Legislative Developments, Organisational Structure, and Heritage

Practices of the post-1974 Era

Reyhan Sabri

From Alasia to Kizzuwatna: Late Cypriot Pottery from Tepebağ Höyük

Ekin Kozal – Deniz Yaşin

A new Archaic Sanctuary in Cyprus? On Sculptural Finds from

Aphendrika in the Karpas Peninsula

Marko Kiessel

159

175

191

219

239

271

�An Integrated Approach to Archaeological Heritage: The Shipwreck

Museum in the Kyrenia Castle, Cyprus

Alessandro Camiz – Zeynep Ceylanlı – Giorgio Verdiani

The Cesnola Collection of Terracotta Oil Lamps from Cyprus

Christopher S. Lightfoot

301

323

From Watershed to Church. A Fragmented Biography of

Panagia tis Kyras (Sazlıköy/Livadia)

Latife Summerer

341

Rural Cyprus between Arab Invasions (8th c.) and Venetian Rule (16th c.):

Church Architecture and Society on the Karpas Peninsula

Thomas Kaffenberger

407

Poetics in Digital Modelling: Bells, Banners, Murals and Music in the

14th c. Church of St. Anne, Famagusta

Michael J.K. Walsh

439

The Issues of Managing Modern Heritage in North Cyprus: An

Investigation of Historic Cinema Buildings in Nicosia

Aliye Menteş – Valentina Donà

473

Transgressive Design Strategies: Political Discourse Acts as a

Transnational Catalyst in the Decision-making of Architectural

Reconciliation Process in Cyprus

Bertuğ Özarısoy – Haşim Altan

The Narrative Dimension of Cultural Heritage in the City of Dead:

Story-telling of Cemeteries

Yannis Polymenidis – Konstantinos Lalenis – Evi Kolovou

501

517

�Architectural Conservation

in Northern Cyprus:

An Overview of the Legislative

Developments, Organisational Structure,

and Heritage Practices of the post-1974 Era

REYHAN SABRİ*

INTRODUCTION

Interest in protecting the architectural heritage in Cyprus arose during

the last quarter of the 19th c. The island came under British rule at this time

and protection was motivated by the then evolving medievalist conservation

ethos in Britain.1 The establishment of the colonial Department of Antiques

in 1934 was a milestone for organising the architectural conservation field

on the island. The new Antiques Law came into force in 1935 and expanded

the scope and cut-off date for the listing of ancient monuments.2 At the same

time, the Antiques Department was given the authority to approve and/or

supervise conservation projects related to the historical structures that were

defined as antiquities.3 The post-colonial bi-communal Republic of Cyprus

(hereafter RoC) subsequently borrowed the British colonial era’s legislative

framework and administrative system in 1960. The main change was in

the organisational structure in that positions formerly occupied by British

scholar-bureaucrats were now filled by Greek Cypriots. The Department of

Antiquities of Cyprus (hereafter DoA) focused its resources on excavating,

protecting, and presenting the archaeological sites and architectural monuments. This was done in a way to best support Greek national and religious

identity.4 As Julie Scott has observed, the conspicuous absence of a Turkish

*

1

2

3

4

Dr. Reyhan Sabri, University of Sharjah, rsabri@sharjah.ac.ae

Sabri 2016, 232–234.

Blackall 1935.

Blackall 1935.

Limbouri 2011, 52. Also see Leriou 2002; Leriou 2007; Michael 2005; Sabri 2019a for

219

�New Approaches

name in the technical or administrative staff of the Department from 19601974 indicates how the Turkish community were sidelined in national heritage management.5

Cyprus was politically and geographically divided in 1974, a culmination

of inter-communal conflicts which started in the 1950s and reached its peak

in 1963. Many of its most important architectural heritage sites remained

within the borders of the new state established by the Turkish Cypriot community in the northern part of the island. The post-1974 era coincides with

the evolution of international conservation principles and guidance, especially after the declaration of the Venice Charter in 1964. Consequently, the

Turkish Cypriots, who did not have any professional presence in the field

before 1974, entered the last quarter of the 20th c. with the responsibility

for a substantial cultural heritage portfolio at a time when cultural heritage

awareness had been rising globally. This article presents an overview of the

legislative developments, organisational structure, and architectural heritage

practices in Northern Cyprus in the post-1974 period.

DEVELOPMENTS IN PRESERVATIONIST LEGISLATION

The British colonial Antiques Law, which had been in effect since 1935,

was amended and enacted as Law no. 31/1959 (Cap. 31) of the RoC, which

was established in 1960. The main change in the definition of an architectural monument was perhaps the change of cut-off date from 1700 to 1850.

As in the colonial era, conservation was centralised under the control and

approval of the Department of Antiques.

One of the first actions of the Turkish Federated State of Cyprus (Kıbrıs

Türk Federe Devleti), which was established in the northern part of the island

in 1975, was the amendment of Law no. 31/1959 and the establishment of the

Department of Antiquities and Museums (Eski Eserler ve Müzeler Dairesi)

(hereafter DoAM). In the newly enacted Law no. 35/1975, the scope of the

definition of monuments was expanded, and the cut-off date was removed.6

The duty to take action to maintain and repair architectural monuments

5

6

220

how the Late Bronze Age, Classical/Hellenistic and Byzantine periods were defined

by the Cypriot Greek elites as the focal points of official archaeology in Cyprus, with

a dominant Hellenisation narrative aiming for the consolidation of the longevity

and superiority of Greek presence.

Scott 2002, 102. For the ongoing boycotting of archaeological activity and the blacklisting of researchers conducting fieldwork in Northern Cyprus since 1974, see Hardy

2010, 144–149.

See the Law of 35/1975. <http://www.cm.gov.nc.tr/Yasalarr> (28.05.2021).

Reyhan Sabri

owned by natural and legal persons was assigned to the ministry to which

DoAM was attached. It was also decided that projects related to the use and

repair of the ancient monuments held by Cyprus Evkaf Administration (hereafter Evkaf) would be undertaken by the Evkaf, subject to the approval of the

Council of Ministers. Meanwhile, with the transfer of the real estate belonging to the Greek Orthodox Church to the Evkaf, it also became responsible

for the maintenance of the Orthodox ecclesiastical structures in Northern

Cyprus abandoned due to the war.7 Combined with the Ottoman waqf properties, the Evkaf entered the post-1974 era responsible for the maintenance

and repair of the island’s most substantial architectural heritage portfolio.

According to the Antiquities Law no. 35/1975, the Ministry to which

DoAM is attached to, has been charged with constituting the High Council

of Monuments (Anıtlar Yüksek Kurulu), which identifies and registers ancient monuments. The new regime prepared a monuments list, which was

approved by the Council of Ministers on 20 December 1976, and published

in the official newspaper in 1979.8 In the list, there were many Ottoman-era

Muslim religious and secular structures which were listed for the first time.

Following the establishment of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

(hereafter TRNC), Urban Planning Law no. 55/899 was enacted, and the City

Planning Office was given the authority to locate and identify heritage sites.

It joined forces with the DoAM to make recommendations for heritage listings to the High Council of Monuments. Another significant development

regarding preservation legislation took place in 1994 when the scope of

Antiquities Law no. 35/1975 was revised, leading to the enactment of Law no.

60/1994, which is still in effect today.10 Law no. 60/1994 addresses the issue

of urban sites and authorises the City Planning Department to identify conservation areas and determine their limits. Based on this, the historic walled

cities of Nicosia and Famagusta and the Kyrenia Castle area were declared

to be urban conservation areas. An important feature of Law no. 60/1994

is Article 42, which establishes the High Council of Immovable Antiquities

and Monuments as the authority to identify the stakeholders and to approve

7

8

Hyland 1999, 67.

Kıbrıs Türk Federe Devleti Resmi Gazetesi (Official Gazette of the Turkish Federated

State of Cyprus), 5 April 1979, no. 29, supplement IV, 45–48.

9 Until 1989, the colonial era’s “Roads and Buildings, Chapter 96” (Yollar ve Binalar

fasıl 96), which remained in force (since 1946) but lacked provisions for urban heritage, had guided urban planning.

10 See for “No. 60/1994 Monuments Law” (No. 60/1994 Eski Eserler Yasası) with

the amendments in 13/2001 and 14/2017. <http://www.cm.gov.nc.tr/Yasalarr>

(28.05.2021).

221

�New Approaches

the management of registered monuments. It consists of eleven members

from relevant government departments, NGOs, and a representative from a

university Northern Cyprus. In addition, Article 20 of the Law envisages the

establishment of a Monuments Protection Fund (Eski Eserleri Koruma Fonu)

(herafter MPF) to create resources for conservation and restoration works.

Also, as per the Law no. 60/1994, while the Evkaf holds the right to maintain and repair the listed historic structures within the framework of the

traditional Ahkam-ül Evkaf regulations, the related projects have been subjected to High Council of Immovable Antiquities and Monuments’ approval, and their execution placed under the supervision of the DoAM. Article

19 defines the conditions for the expropriation of monuments possessed by

natural or legal persons - including Evkaf - which are at risk of losing their

character through inappropriate physical interventions or lack of maintenance. Accordingly, the conservation and use of these expropriated properties follow plans prepared by the DoAM.

It is important to note that while the legislation is comprehensive in terms

of identifying monuments and assigning responsibilities, heritage policy and

resources in Northern Cyprus is still inadequate. The consequences of this

will be further discussed later in this paper.

ESTABLISHING THE ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE

With the establishment of the DoAM in 1975, the Turkish Cypriots

emerged for the first time as actors, who had not previously taken an active role in management, or technical and practical activities, of the Greek

Cypriot-led DoA. The crucial step in establishing the organisational structure for architectural conservation was the creation of a Documentation

and Restoration Branch (Rölöve ve Restorasyon Birimi) under the DoAM

and employing İlkay Feridun,11 a Turkish Cypriot restoration specialist. Ms.

Feridun was instrumental in initiating the documentation of architectural

heritage in Northern Cyprus. She also consolidated conservation awareness

in the DoAM in line with the then developing in international conservation

principles. Unfortunately, despite this promising start, subsequent governments could not allocate adequate budgetary and human resources for the

Documentation and Restoration Branch to enable comprehensive mainte11 Ms. Ilkay Feridun is the first Turkish Cypriot architectural heritage professional who

returned to the island. She had completed her masters degree in the restoration of

historic buildings in 1975 at the Middle East Technical University. See Özdeğer –

Yeşilada 1993, 14.

222

Reyhan Sabri

nance and conservation works on all ancient monuments. In many cases,

the action remained confined to emergency repairs due to lack of funds.

Nevertheless, most of the conservation works undertaken by the DoAM,

especially during 1990-2005, are highly commendable in terms of the use

of local materials and traditional plasters/mortars which are physically and

chemically compatible with the existing historic fabric. However, lack of

resources became apparent with those cases requiring the use of modern

strengthening techniques and materials. The frequent changing of the ministry to which DoAM is attached often results in slow decision making to

the detriment of ancient monuments and heritage structures.12

As for the Evkaf, despite having a substantial portfolio of historical structures, it has remained weak in terms of developing an effective organisational

structure dedicated to conservation work. This is seen in the absence of heritage professional(s) employed within the institution, as well as in the lack

of clear heritage policy and regulations. The multi-purpose Construction

and Real Estate Branch (İnşaat ve Emlak Şubesi) was established under the

Vakıflar ve Din İşleri Teşkilat Kanunu (Foundations and Religious Affairs

Organization Law) of 31/1971. It undertakes the planning and implementation of the repair and maintenance of all types of architectural heritage

belonging to the institution.

There are weaknesses in the organisational structures governing architectural heritage in Northern Cyprus, especially the lack of technical personnel

and equipment. These deficiencies have been highlighted at the National

Culture and Art Congresses; organised with relevant stakeholders in 1998,

2001 and 2006; yet they remain a serious problem. For instance, the transfer of the MPF in 2006 to the Finance Ministry was a severe blow to the

DoAM’s financial capacity.13 The Fund was established as per Article 20 of

Law no. 60/1994, and provided financial resources for several emergency

and restoration projects between 1994-2006. The lack of financial resources

and technical expertise has also been highlighted in a report by Josef Stulc

in 2002, submitted to the Council of Europe regarding the current state of

architectural heritage in Northern Cyprus.14 How architectural conservation

practice has been shaped in this context is addressed in the next section.

12 Regarding the administrative and organisational weaknesses caused by changing the

ministries with responsibilities for urban conservation in the TRNC, see Hoşkara

– Doratlı 2011, 869–870.

13 For pleas at the Culture and Art Congress in 2006 for its transfer back to the DoAM

to generate revenue for conservation projects, see Doratlı 2014.

14 Stulc 2002.

223

�New Approaches

ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE CONSERVATION PRACTICES

IN NORTHERN CYPRUS IN THE POST-1974 ERA

Architectural conservation practice was quite slow, especially in the first

twenty years after 1974, due to the lack of heritage practitioners, technical

personnel, and extremely tight finances. One of the first projects undertaken by the DoAM was the restoration and adaptive reuse of the Derviş Paşa

Konağı in Nicosia’s walled Arabahmet district carried out between 1979-86

(Fig. 1).15 This building, which was converted into an ethnographic museum

in 1988, was listed in 1979. The project indicated that the island’s hitherto neglected Ottoman architectural legacy16 would receive attention in the

new era. Among the other conservation works undertaken by the DoAM in

the 1980s and 1990s were: the restoration of a part of the Venetian walls of

Nicosia in 1982-86, the restoration of Ag. Lucas Church in Nicosia in 1986

and Haydar Paşa Camii (former St. Catherine Church) in 1986-89, and the

conservation and adaptive reuse of St. Barnabas Monastery near Famagusta

in 1991-92, which became the Icon and Archaeology Museum.17 The establishment of the abovementioned MPF provided funding for several projects

in the 1990s. These included the restoration and adaptive reuse projects of

the Eaved House (Saçaklı Ev) and the Lusignan House (Lüzinyan Evi) in

Nicosia. As well, partial maintenance and repair works were carried out in

Kyrenia Castle, which was converted into a museum, exhibition and conference space.18

One of the first restoration projects was that of Büyük Han in Nicosia,

which is the island’s largest classical Ottoman city inn and administratively

attached to the Evkaf (Fig. 2). Planning was done by Ms Ilkay Feridun of

DoAM and the project started in 1982 under the supervision of the DoAM.

However, it came to a halt due to insufficient funding, and then continued with support provided by the German Government between 1988 and

1990, and later by the Turkish Embassy between 1995-2002.19 The southern

portico of the Han was assessed to be in endangered at risk of falling and

15

16

17

18

19

224

Özdeğer – Yeşilada 1993, 14.

Sabri 2017.

Özdeğer – Yeşilada 1993, 15.

Hyland 1999, 68.

This information has been retrieved from an interview with Ms. İlkay Feridun on

8 June 2012.

Reyhan Sabri

pulled down during the restoration work under the control of the DoA in

1963.20 The portico was reconstructed during the restorations in the 1990s in

reinforced concrete and clad with stone slabs similar to the original masonry. When the restoration works were completed, the building was converted

into a cultural and tourism centre where traditional Cypriot handicrafts are

produced and sold.

Restoration projects planned and implemented by the DoAM used local

materials, traditional mortars, plasters, and water-proofing compositions

compatible with the original products. These practices indicate the adoption

of the restoration principles stipulated by the Venice Charter (1964). Early

efforts were made not to use Portland cement in the repair or restoration

works unless it was necessary for structural consolidation. Even though the

Turkish Cypriots entered the post-1974 era without any experience in the

field, by the 1980s, the DoAM had developed sufficient capacity in planning

and executing architectural conservation works to be up to date with the

evolving international principles.21 The problem was, and still is, the lack of

adequate human resources and funds.22 Due to the low numbers of technical

staff, the DoAM has been inefficient in monitoring the state of the architectural monuments. Consequently, the ability to monitor repair/restoration

works on heritage assets owned by other natural or legal persons, especially

those by the Evkaf, has suffered. For instance, it was only by coincidence

that the DoAM became aware that the original materials and designs were

not being altered in the restoration works carried out in the 1980s for the

Great Bath (Büyük Hamam), the largest surviving Ottoman public bath on

the island which was owned by the Evkaf.23

Projects to conserve architectural monuments and heritage structures

which are the property or responsibility of the Evkaf are prepared by the institution’s Construction and Real Estate Branch. Such projects are subject to

the approval of the High Council of Immovable Antiquities and Monuments

(Taşınmaz Eski Eserler ve Anıtlar Yüksek Kurulu), and they are carried out

under the supervision of the DoAM. Note that before being transformed

20 Ms. İlkay Feridun on 8 June 2012.

21 Arguably, restoration practices in line with the Venice Charter of 1964 emerged in

Northern Cyprus in the 1980s, almost simultaneously with the RoC. For an overview of the conservation practice in the RoC, see Philokyprou – Limbouri-Kozakou

2015.

22 The lack of conservation specialists and laboratory has also been recently remarked,

albeit in the context of archaeological findings, by Fehlmann 2016, 433.

23 This information has been retrieved from an interview with Ms. İlkay Feridun on

8 June 2012.

225

�New Approaches

into a governmental department - namely the Evkaf - during the British

colonial era, Cyprus waqfs were a self-sustaining institution which had a

well-developed building upkeep and maintenance system.24 The continuity

of waqfs depended on the proper upkeep and maintenance of the endowed

buildings. Hence, it was a priority to use the waqf revenues for the upkeep

and maintenance of both the income-generating structures and religious facilities. The waqf system operated with sustainable principles such as regular

monitoring and maintenance on buildings to prevent advanced and costly

decay. With its transformation into a government department during the

colonial era, the institution’s resources were redirected to other areas, and

it lost its capacity to offer affordable building protection. The Evkaf entered

the post-1974 era as a government department, whose resources and revenues are mostly directed towards the newly emerging requirements of the

community.25 This was unlike the Islamic waqf system, which focused on the

protection of the endowed buildings. While the Evkaf owns a large number

of heritage structures, including examples of various residential, commercial,

and educational properties, their conservation decisions have often prioritised functioning mosques.26 For this purpose, the Evkaf has received funds

and technical expertise from Turkey’s General Directorate of Foundations

(TC Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüğü) in the post-1974 era. An example of this

is the restoration of many historical mosques since the 1990s in Northern

Cyprus using the resources of the General Directorate of Foundations as per

the protocols signed between them and the Evkaf.27

As for the churches in the North abandoned due to military conflict and

incorparated into administration of the Evkaf after 1974, those listed as ancient monuments were either entirely transferred to the DoAM, or the two

organisations shared responsibilities. Many churches in the villages, mostly

constructed during the British colonial period, have been converted into

mosques. Hence, they have been provided with essential maintenance and

repair. Some have been repaired and allocated to local organisations to be

24 For an analysis of Ottoman waqfs’ role in shaping and protecting built environments

in Cyprus, see Sabri 2019b, 32–44. For further information on the organization of

waqfs in Ottoman Cyprus, see Yıldız 2009; and for the typology and examples of

waqf built properties around the island see Bağışkan 2009.

25 For detailed analyses of the shifts and transformation of the waqf system throughout the British colonial era, see Sabri 2019b, 45–132.

26 Based on the suthor’s survey in the Evkaf ’s waqf building upkeep and maintenance

files (from 1975-2010) in 2012.

27 This information has been retrieved from an interview with Mr. Mustafa

Kaymakamzade, the then Evkaf Director, on 22 April 2012.

226

Reyhan Sabri

used for various functions, including cultural activities, exhibition spaces and

meeting halls.28 Unfortunately, those which remained unused, especially in

remote rural areas have materially and structurally deteriorated because of

the lack of resources to fund repair and maintenance works. While the dire

conservation state of some of the Greek Orthodox ecclesiastical structures

in rural areas has been criticised,29 it must be remembered that political isolation has its toll not only on people but also on heritage structures.30 The

converted churches sadly became a source of tension between the Greek

and Turkish communities when the Greek Cypriots visited them after the

opening of the borders in 2004.31 This led to the construction of new village

mosques and the converted churches becoming unused, leaving them open

to deterioration and creating conservation problems.

INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS AND ARCHITECTURAL

CONSERVATION PRACTICE IN NORTHERN CYPRUS

The de-facto division of Cyprus is a long-running obstacle for attracting conservation professionals and funding to Northern Cyprus. To some

extent, this has been overcome with the backing of international organisations. These include the United Nations Development Programme (herafter

UNDP), the United States Agency for International Development (herafter

USAID), Supporting Activities that Value the Environment (SAVE - which

is a subsidiary of USAID), and the European Commission. Among these international organisations, UNDP has been the most active. Among the first

projects supported by the UNDP was the bi-communal Nicosia Master Plan

(hereafter NMP) prepared under the 1979 initiative of Mustafa Akıncı and

Lellos Demetrades, the then Turkish and Greek Mayors of Nicosia. It aimed to

create a joint planning strategy for improving infrastructure and rehabilitating the heritage areas in the walled city.32 The first phase of the plan in North

28 Saifi – Yüceer 2013.

29 See for instance: Chotzakoglou 2008; Jansen 2005. Sadly, these publications fail to

be objective in the coverage of religious sites belonging to both communities. For

an analysis of Michael Jansen’s manipulative exclusion of the destructions on the

Islamic heritage sites in the RoC while focusing only on the Christian sites in the

North, see Hardy 2010, 160–168.

30 As Hardy 2010, 144–149, has demonstrated, the ongoing boycotting of archaeological excavations and publications, and the blacklisting of the researchers who conduct fieldwork in Northern Cyprus, not only hinders the widening of knowledge,

but also the improvement of cultural heritage skills in the North.

31 Constantinou et al. 2012.

32 Stubbs – Makas 2011, 353.

227

�New Approaches

Nicosia was the restoration and rehabilitation of the Arabahmet District,

which started in 1985 and continued through the 1990s. The Arabahmet

District was a declining neighbourhood, located in the north of Nicosia,

comprising mainly Ottoman and British era residential buildings. UNDP

and USAID provided the funding.33 The project sought general revitalisation

rather than a comprehensive conservation scheme. It initially focused on

renovating the facades, and street landscaping and pedestrianisation, with

a limited number of properties having interior renovations.34 Houses were

mainly private properties, and no repair grants were available until much

later for the property owners to undertake interior restoration works. Sadly,

in the absence of regular maintenance, almost two decades after the initial

façade renovations, the exterior finishings have deteriorated (Fig. 3).

The funding of conservation works, even urgent ones, remained a significant problem until the beginning of the 21st c. Finally, in 2002, the Council of

Europe issued a report emphasising problems requiring urgent interventions

and protection of architectural heritage sites in Northern Cyprus, stressing

that this situation cannot be ignored any further and calling for international

funding.35 In the same period, the preparation of restoration and rehabilitation projects related to Nicosia’s historic city walls (which were already

identified in NMP), and the provision of financial support were brought

under the umbrella of the UNDP.

With Cyprus becoming a full member of the European Union in 2004,

further opportunities emerged to receive support to document and preserve

architectural heritage throughout the island. Since then, architectural conservation practices have gained momentum, especially with the financial

backing of the European Commission under the auspices of the UNDP. Many

architectural monuments have been restored, and historical environmental

rehabilitation works have been carried out in Northern Cyprus.36 Restoration

works in walled Nicosia were extended to include buildings from the British

colonial period: Bandabulia, which is a closed market from the British colonial period, has been restored and serves its original function.37 Among other

33 Further details: <https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/

pdf/fiche-projet/cyprus/cy-fm/2001/cy0104-01-rehabilitationnicosia-phase2.pdf>

(19.07.2020).

34 Doratlı 2016, 460–61.

35 Stubbs – Makas 2011, 351.

36 Further details: <https://www.cy.undp.org/content/cyprus/en/home/operations/

projects/partnershipforthefuture/upgrading-of-local-and-urban-infrastructure--phase-ii.html> (19.07.2020).

37 For the renovation and revitalization of Bandabulia: <https://www.cy.undp.org/

228

Reyhan Sabri

works are the restoration and rehabilitation of Samanbahçe mass housing and

the restorations of the facades of traditional houses in the Selimiye region.

One of the key projects, perhaps, is the conservation works carried out

on Bedesten (former St. Nicholas Church) in Nicosia. This Frankish-era

Orthodox church, which was converted into a covered market during the

Ottoman period38, has been restored and used as an exhibition and conference hall. The Bedesten project is very important for the implementation of

restoration techniques that have not been used before in Northern Cyprus.

Within the scope of this project, structural consolidation was made between

2004-06 and the earthquake resistance of the building was increased.39

Between 2007 and 2009, interventions focused on the protection of materials and arrangements for adaptive reuse. Hydraulic lime injection strengthened the bearing capacity of the foundation and walls, which had become

structurally weak. The application of the hydraulic lime injection was a first

in Northern Cyprus, and it set an example for other projects, including the

Büyük Hamam restoration project, which was planned and implemented by

the Evkaf. In addition, the contemporary shell, made from steel and wood,

was used to replace the missing vaulted roof (Fig. 4). The arched openings

were covered by glass panels fastened with metal hooks, as part of a system

which does not require drilling holes in the original fabric. These were considered to be innovative solutions when they were applied for the first time

in Northern Cyprus.

Another milestone in terms of international support for the conservation

of architectural heritage emerged in 2008 when the European Parliament

decided to support, via the European Commission, a comprehensive survey

of cultural heritage in Northern Cyprus. The purpose of this survey was to

identify heritage structures, document their current state, and plan and cost

their conservation. Later, the study was expanded to include a comprehensive

inventory of Ottoman period architectural heritage throughout the island.

As part of this project, a bi-communal Technical Committee on Cultural

Heritage was established in 2008. An extensive survey was carried out in 2010

with the sponsorship of UNDP as per the invitation of the European Union.

content/cyprus/en/home/operations/projects/partnershipforthefuture/upgrading-of-local-and-urban-infrastructure---phase-ii/renovation-of-the-bandabuliya--old-market-.html> (14.08.2020)

38 Bağışkan 2009, 506.

39 Further details: <https://www.cy.undp.org/content/cyprus/en/home/operations/

projects/partnershipforthefuture/upgrading-of-local-and-urban-infrastructure--phase-ii/restoration-and-re-use-of-the-bedestan--st--nicolas-church-.html>

(19.07.2020).

229

�New Approaches

Upon its completion, 2300 cultural heritage sites were identified, and inventory was prepared for about 700 of them.40 The latter were ranked based on a

set of heritage valorisation criteria, and technical evaluation was performed

on 121 of them.41 In the second phase of the project, heritage structures were

identified that were a conservation priority and staged conservation works

were initiated.42 Among them were four large-scale projects; the medieval

walls and Othello Tower in Famagusta, Apostolos Andreas Monastery in

Karpasia peninsula and Ag. Panteleimonas Monastery in Çamlıbel/Myrtou.43

In addition to these, conservation projects began on various heritage structures, and emergency measures were introduced in stages, especially for

abandoned mosques and churches under threat of collapse in rural areas

throughout Cyprus.44

Overall, Northern Cyprus has witnessed an unprecedented momentum

change in the conservation of architectural monuments and heritage structures since the outset of the 21st c. However, concerns are emerging relating

to the negative impacts of the continuing politicization of the conservation

planning. For instance, the Greek Orthodox Church authority’s unwillingness to participate in the conservation of the Apostolos Andreas Monastery,

delayed the works for a long time.45 The implementation of the restoration

project, which has been prepared by the University of Patras in Greece and

under the directives of the Greek Orthodox Church authority of Cyprus,

finally started in September 2014.46 In addition to renovation works, the

project involves controversial reconstruction practices as seen in the additions on the northern part of the Church (Fig. 5). Drawing lessons from

such practices is undeniably important for the formulation of conservation

regulations and guidelines.

40 Tuncay 2016, 443.

41 Tuncay 2016, 443.

42 See for further information: <http://www.cy.undp.org/content/cyprus/en/home/

operations/projects/partnershipforthefuture/support-to-cultural-heritage-monuments-of-great-importance-for-c.html> (19.07.2020).

43 See: <http://www.cy.undp.org/content/cyprus/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2015/01/28/tender-for-agios-panteleimonas-monastery-closing-soon/>

(19.07.2020).

44 Tuncay 2016, 443–445. For further information, see The Technical Committee

on Cultural Heritage (2015), <http://www.cy.undp.org/content/cyprus/en/home/

library/partnershipforthefuture/the-technical-committee-on-cultural-heritage--2015-.html> (11.08.2020), <https://www.cy.undp.org/content/cyprus/en/

home/operations/projects/partnershipforthefuture.html> (11.08.2020).

45 Harmanşah 2016, 481.

46 For the phases of the project: <https://www.cy.undp.org/content/cyprus/en/home/

projects/restoration-of-the-monastery-of-apostolos-andreas.html> (11.08.2020).

230

Reyhan Sabri

CONCLUSION

Despite Turkish Cypriots having entered the post-1974 period lacking

experience in the field of architectural conservation, they have been proactive in creating legislative and organisational frameworks. The preservationist legislation allowed for a comprehensive listing of architectural heritage freed from a cut-off date. As well, the immediate establishment of the

DoAM, and appointment of a conservation specialist, were key moments

of success for conservation projects implemented in the 1980s and 1990s.

However, due to limited human and technical resources, and tight budgets,

the number of heritage structures which benefitted from conservation works

during that timeframe were insignificant compared to the expanded list of

ancient monuments. Similarly, the Evkaf, which manages a substantial architectural heritage portfolio, has remained weak in terms of its institutional

capacity for conservation planning. With the involvement of the European

Commission, the financial resources available for conservation, especially

for emergencies, has increased since 2004. International experts have been

instrumental in introducing new perspectives, technologies, and innovative

solutions to the field. However, not only the strengths but also the weaknesses

of such practices should be comprehensively analysed. Lessons learnt from

these practices need to be considered carefully and utilised in forming the

hitherto absent regulations for architectural conservation practice.

Relying on foreign aid for emergency conservation is not a sustainable

approach. Developing sound local funding sources should be prioritised

as this will allow for regular monitoring and maintenance on the heritage

structures. Better funding will prevent not only advanced decay but also

make local-level conservation efforts financially manageable. Another problem which needs to be addressed is the lack of collaboration between the

DoAM, the DoA, Evkaf, and local academic institutions regarding database

formation and knowledge and expertise sharing in the use of technologies,

both for documentation and conservation. Such a collaboration could be

invaluable in building architectural heritage databases, but also in terms of

consultancy services, especially for the historical analyses of heritage structures and their valuation.

The way forward requires improving heritage policy and practice by extensively analysing the weaknesses in legislative, financial, and organisational frameworks, creating opportunities for multi-disciplinary collaboration,

and drawing lessons from the practical experiences of the post-1974 era.

231

�New Approaches

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bağışkan 2009

T. Bağışkan, Ottoman, Islamic and Islamized Monuments in Cyprus (Nicosia

2009).

Blackall 1935

H.W.B. Blackall, A Bill Entitled: A Law to Consolidate and Amend the Law

Relating to Antiquities. Supplement to the Cyprus Gazette, No. 2441, 10 May

(Nicosia 1935) 315–330.

Chotzakoglou 2008

C. Chotzakoglou, Religious Monuments in Turkish-Occupied Cyprus. Evidence

of Destruction (Nicosia 2008).

Constantinou et al. 2012

C.M. Constantinou – O. Demetriou – M. Hatay, Conflicts and Uses of Cultural

Heritage in Cyprus, Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 14,2, 2012,

177–198.

Doratlı 2014

N. Doratlı, Ağır Hasta Lefkoşa Surlariçini Kurtarmak, Havadis Gazetesi Poli

eki 174, 13 April 2014.

Doratlı 2016

N. Doratlı, Revitalization of the Northern Walled City of Nicosia: Merits and

Pitfalls, in: L. Summerer – H. Kaba (eds.), The Northern Face of Cyprus: New

Studies in Cypriot Archaeology and Art History (Istanbul 2016) 455–476.

Fehlmann 2016

M. Fehlmann, Conservation and Restoration Measures in Northern Cyprus,

in: L. Summerer – H. Kaba (eds.), The Northern Face of Cyprus: New Studies

in Cypriot Archaeology and Art History (Istanbul 2016) 427–440.

Hardy 2011

S.A. Hardy, Interrogating archaeological ethics in conflict zones: Cultural heritage work in Cyprus (Ph.D. diss. University of Sussex 2011).

Harmanşah 2016

R. Harmanşah, Appropriating Common Ground? On Apostolos Andreas

Monastery in Karpas Peninsula, in: L. Summerer – H. Kaba (eds.), The Northern

Face of Cyprus: New Studies in Cypriot Archaeology and Art History (Istanbul

2016) 477–488.

Hoşkara – Doratlı 2011

Ş.Ö. Hoşkara – N. Doratlı, A Critical Evaluation of the Issue of Conservation

of the Cultural Heritage in North Cyprus, in: Z.C. Arda – Z.B. Özer – R.

Gürses – B.T. Karababa – M. Akbulut – Z. Dilek (eds.), Proceedings of the

232

Reyhan Sabri

38th International Congress of Asian and North African Studies II (Ankara

2011) 849–872.

Hyland 1999

A.D.C. Hyland, Ethnic Dimensions to World Heritage: Conservation of the

Archaeological Heritage of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Journal

of Architectural Conservation 5,1, 1999, 59–71.

Jansen 2005

M. Jansen, War and Cultural Heritage: Cyprus after the 1974 Turkish Invasion

(Minneapolis 2005).

Leriou 2002

N.A. Leriou, Constructing an Archaeological Narrative: The Hellenization of

Cyprus, Stanford Journal of Archaeology, 2002, 1–32.

Leriou 2007

N.A. Leriou, The Hellenization of Cyprus: Tracing Its Beginnings (an updated version), in: S. Müller Celka – J.C. David (eds.), Patrimoines culturels en

Méditerranée orientale: recherche scientifque et enjeux identitaires. 1er atelier

(29 novembre 2007): Chypre, une stratigraphie de l’identité (Lyon 2007) 1–33.

Limbouri 2011

E. Limbouri, The Restoration of Ancient Monuments of Cyprus from the

Establishment of Department of Antiquities of Cyprus in 1935 until 2005, in:

C.A. Brebbia – L. Binda (eds.), Structural Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage

Architecture XII 118 (Southampton 2011) 45–60.

Michael 2005

A.S. Michael, Making Histories: Nationalism, Colonialism and the Uses of the

Past on Cyprus (Ph.D. diss. University of Glasgow 2005).

Özdeğer – Yeşilada 1993

S. Özdeğer – F. Yeşilada, Odamızdan Portreler: Yüksek Mimar İlkay Feridun,

Mimarca, May-June 1993, 14–15.

Philokyprou – Limbouri-Kozakou 2015

M. Philokyprou – E. Limbouri-Kozakou, An Overview of the Restoration of

Monuments and Listed Buildings in Cyprus from Antiquity until the Twentyfirst Century, Studies in Conservation 60,4, 2015, 267–277.

Sabri 2016

R. Sabri, The Genesis of Hybrid Architectural Preservation Practices in British

Colonial Cyprus, Architectural Research Quarterly 20,3, 2016, 243–255.

Sabri 2017

R. Sabri, From an Inconsequential Legacy to National Heritage: Revisiting

the Conservation Approaches towards the Ottoman Built Legacy in British

233

�New Approaches

Reyhan Sabri

Colonial Cyprus, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 19,1,

2017, 55–81.

Sabri 2019a

R. Sabri, Greek Nationalism, Architectural Narratives, and a Gymnasium that

wasn’t, International Journal of Heritage Studies 25,2, 2019, 178–197.

Sabri 2019b

R. Sabri, The Imperial Politics of Architectural Conservation: The Case of Waqf

in Cyprus (Cham 2019).

Saifi – Yüceer 2013

Y. Saifi – H. Yüceer, Maintaining the absent other: the re-use of religious heritage

sites in conflicts, International Journal of Heritage Studies 19,7, 2013, 749–763.

Scott 2002

J. Scott, World Heritage as a Model for Citizenship: The Case of Cyprus,

International Journal of Heritage Studies 8,2, 2002, 99–115.

Stubbs – Makas 2011

J.H. Stubbs – E.G. Makas, Architectural Conservation in Europe and Americas

(New Jersey 2011).

Stulc 2002

J. Stulc, Report on A Mission to Cyprus, Document 9460, Parliamentary

Assembly Documents Working Papers V, 24-28 June 2002 Ordinary Session

(Strasbourg 2002) 112–122.

Fig. 1 - Derviş Paşa Mansion in Nicosia; adaptive reuse as ethnographic museum.

Fall of plaster on the walls indicate lack of regular maintenance; a consequence of

lack of resources and weak conservation planning (by author).

Tuncay 2016

A. Tuncay, The Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage in Cyprus: From

Conflict to Cooperation, in: L. Summerer – H. Kaba (eds.), The Northern Face

of Cyprus: New Studies in Cypriot Archaeology and Art History (Istanbul

2016) 441–453.

Yıldız 2009

N. Yıldız, The Vakıf Institution in Ottoman Cyprus, in: M.N. Michael – M.

Kappler – E. Gavriel (eds.), Ottoman Cyprus: A Collection of Studies on History

and Culture (Wiesbaden 2009) 117–159.

Fig. 2 - Büyük Han, adaptive reuse as cultural-commercial space (by author).

234

235

�New Approaches

Reyhan Sabri

a.

Fig. 4 - Interior view from Bedestan in Nicosia (by author).

b.

Fig. 3a-b - Views from the present conservation state of facades in

Arabahmet District in Nicosia (author).

236

Fig. 5 - Reconstruction works on the historic site of Apostolos Andreas Monastery in Karpasia peninsula in 2016 (by author).

237

�

Reyhan Sabri

Reyhan Sabri