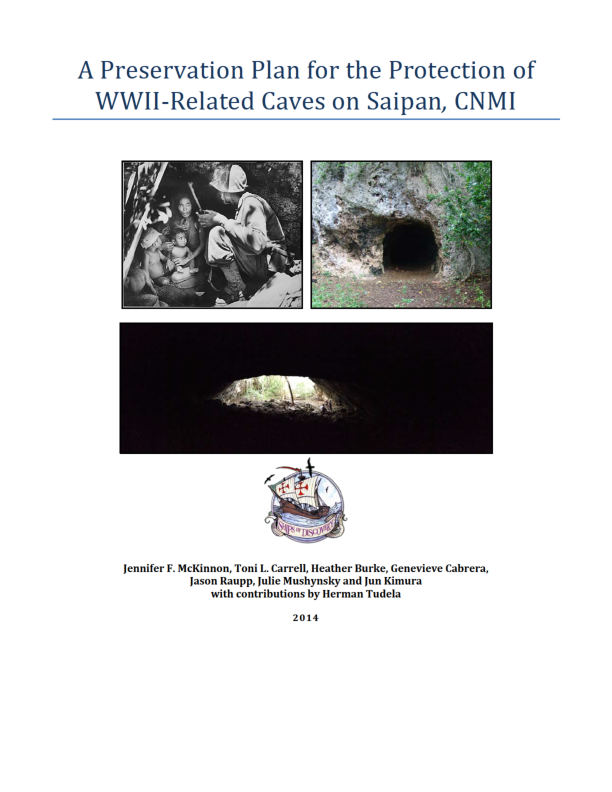

�Cover Photographs by Heather Burke and Genevieve Cabrera, 2013

��Title page photograph by Genevieve Cabrera, 2013

�Dedicated to the late Escolastica B. Tudela-Cabrera

1930 - 2013

She was known by the community of Saipan as “the champion of common causes.” Her energy,

knowledge and passion for passing on history made her an inspiration to all that knew her.

iii

�Abstract

The focus of this project and planning document is the WWII Battle of Saipan that occurred in June and

July of 1944 on the island of Saipan in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. This project

builds upon two previous American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) projects: 2009-2010 WWII

Invasion Beaches Underwater Heritage Trail GA-2255-09-028 and 2011-2012 Management Plan for

WWII Submerged Resources in Saipan GA-2255-11-018. However the focus of this grant is on the

terrestrial historic properties related to the Battle, specifically cave sites. The project aimed to:

1. conduct consultation and public meetings to gauge interest in protecting archeological cave

sites on private property, identify the values associated with such sites, and examine

issues/problems/solutions related to their protection;

2. produce public service announcements to increase awareness about the importance of

protecting archeological cave sites on private property; and

3. develop an initial planning document for the long-term protection of archeological cave sites on

private property.

The results of the public consultation process indicate that there is strong local support for protecting

WWII-related cave sites on private and public lands. Members of the local community have many

memories of using caves or their family members using caves for shelter and protection during WWII.

There is also a strong ancestral connection with caves that supersedes WWII, and evidence of this can

be found in the rock art on cave walls and the Indigenous artifacts scattered on the cave floors.

This document describes many of the natural and cultural factors affecting the preservation of historic

cave properties. Tourism and development are the two biggest concerns with regards to the

preservation of caves, and sustainable tourism must be implemented in order to preserve these

properties for generations to come.

This document also describes the process of developing two types of public service announcements –

radio and television. It outlines the process, content and delivery of these products with regards to their

ability to increase awareness about the importance of protecting historic resources.

Finally, this is a planning document that outlines a ten-year plan for both a community-run organization

and the Historic Preservation Office. Key strategies are identified and specific actions are outlined yearby-year. This document is meant to empower the local community and government to manage their

historical properties and should be read with this sentiment in mind.

iv

�Acronyms and Abbreviations

ABPP

AMP

CNMI

CRM

CZMP

DEQ

DFW

DLNR

DOI

DPL

FU

HPO

MARC

MVA

NEPA

NMC

NMICH

NPS

NRHP

SHARC

Ships

SEARCH

US

UXO

WWII

American Battlefield Protection Program

American Memorial Park

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

Coastal Resources Management

Zoning Management Program

Department of Environmental Quality

Division of Fish and Wildlife

Department of Lands and Natural Resources

Department of the Interior

Department of Public Lands

Flinders University

Historic Preservation Office

Micronesian Area Research Centre

Marianas Visitors Authority

National Environmental Policy Act

Northern Marianas College

Northern Mariana Islands Council for the Humanities

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Swift and Harper Archaeological Research Consultants

Ships of Exploration and Discovery Research, Inc.

Southeastern Archaeological Research, Inc.

United States

Unexploded Ordnance

World War II

v

�Table of Contents

Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ iv

Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ v

Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... 6

List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. 10

List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................... 13

Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................... 14

Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 15

The Battle of Saipan 1911-1944 (after Burns 2008) ................................................................................ 17

Japanese Defences on Saipan............................................................................................................. 17

The Mariana Islands in WWII, 1941-1944 .......................................................................................... 18

Operation Forager .............................................................................................................................. 18

The Battle of Saipan – Operation Tearaway, 1944 ............................................................................. 20

The aftermath of the Battle of Saipan ................................................................................................ 23

Chapter 2: The Battlefield Today ................................................................................................................ 24

The battlefield ......................................................................................................................................... 24

Potential National Register boundary ................................................................................................ 25

Previous cave research in the Mariana Islands ....................................................................................... 28

Oral histories ........................................................................................................................................... 30

Phelan and Denfeld’s cave research in the Pacific .................................................................................. 30

Previously recorded cave sites on Saipan ............................................................................................... 34

The cave sites survey ............................................................................................................................... 36

Chapter 3: Cave Geology and Historical Background ................................................................................. 39

Geology .................................................................................................................................................... 39

Types and locations of caves .............................................................................................................. 39

Prehistoric Indigenous use and adaptation of caves on Saipan .............................................................. 43

Historic and Ethnographic Accounts .................................................................................................. 43

Archeological Evidence ....................................................................................................................... 44

WWII use of caves: pre-, during and post-battle .................................................................................... 46

6

�Indigenous and non-Japanese civilians .............................................................................................. 47

Japanese civilians................................................................................................................................ 48

Japanese military ................................................................................................................................ 49

US military .......................................................................................................................................... 54

Archeological Evidence ....................................................................................................................... 55

Post-war cave use .................................................................................................................................... 56

Local community ................................................................................................................................ 56

Japanese bereavement bone collection missions .............................................................................. 56

Chapter 4: Cave, Rockshelter and Tunnel Sites .......................................................................................... 61

Sites ......................................................................................................................................................... 61

Uncle John’s Cave ............................................................................................................................... 61

Papagu Cave ....................................................................................................................................... 65

Japanese Field Hospital Cave and Swiftlet Cave................................................................................. 68

Ayuyu Family Caves ............................................................................................................................ 74

Gen’s Research Cave .......................................................................................................................... 79

Camacho Family Cave ......................................................................................................................... 82

“Naftan” Cave at Lao Lao Bay Golf Resort .......................................................................................... 86

Ben Sablan Family Caves .................................................................................................................... 87

1000 Men Cave or Liyang I Falingun Hanum...................................................................................... 89

Achugao Caves.................................................................................................................................... 91

Cabrera Family Cave ........................................................................................................................... 93

Chalan Galaidi Cave ............................................................................................................................ 96

Esco’s Caves ........................................................................................................................................ 97

Kalabera Cave ..................................................................................................................................... 97

Impacts on sites ....................................................................................................................................... 98

Looting, “salting,” or moving artifacts................................................................................................ 98

Spelunking .......................................................................................................................................... 98

Vandalism ........................................................................................................................................... 99

Japanese bereavement bone collecting missions ............................................................................ 100

Refuse dumping ................................................................................................................................ 100

Memorialization ............................................................................................................................... 100

Storm activity and erosion ............................................................................................................... 100

7

�UXO detonation ................................................................................................................................ 101

Fire .................................................................................................................................................... 101

Wildlife ............................................................................................................................................. 101

Livestock grazing............................................................................................................................... 101

Hunting ............................................................................................................................................. 102

Chapter 5: Planning: Community Engagement and Public Service Announcements............................... 103

Community engagement and planning meeting ................................................................................... 103

Public service announcements .............................................................................................................. 105

Chapter 6: Preserving WWII Cave Sites from the Battle of Saipan .......................................................... 107

Areas currently protected ..................................................................................................................... 107

Land protection options ........................................................................................................................ 108

Public and private property easements ........................................................................................... 108

Leasing .............................................................................................................................................. 109

Land purchase .................................................................................................................................. 109

Zoning and local ordinances ............................................................................................................. 110

Community battlefield group ................................................................................................................ 110

Preservation partners ............................................................................................................................ 110

Sustainable tourism ............................................................................................................................... 111

Restricting access .................................................................................................................................. 111

Education ............................................................................................................................................... 112

Enforcement .......................................................................................................................................... 112

Chapter 7: Recommended Actions ........................................................................................................... 113

Part 1: Community actions .................................................................................................................... 113

Form a community organization ...................................................................................................... 113

Apply for funding .............................................................................................................................. 113

Form partnerships ............................................................................................................................ 113

Work with landowners ..................................................................................................................... 113

Maintain momentum ....................................................................................................................... 114

Part 1: community action plan .............................................................................................................. 114

2014-2015......................................................................................................................................... 114

2015-2016......................................................................................................................................... 114

2016-2017......................................................................................................................................... 114

8

�2017-2018......................................................................................................................................... 115

2019-2020......................................................................................................................................... 115

2021-2022 more ............................................................................................................................... 115

2022-2023 more ............................................................................................................................... 116

2023-2024......................................................................................................................................... 116

Part 2: HPO actions ................................................................................................................................ 116

Conduct a grey literature survey and develop a database of known sites ...................................... 116

Develop a management plan ........................................................................................................... 116

Form partnerships ............................................................................................................................ 117

Develop interpretation ..................................................................................................................... 117

Work with landowners ..................................................................................................................... 117

Develop a monitoring program ........................................................................................................ 117

Develop a tour guide certification program ..................................................................................... 118

Develop a restricted access, user fee system at Kalabera Cave* ..................................................... 118

Develop an archeological project ..................................................................................................... 118

Maintain momentum ....................................................................................................................... 119

Part 1: HPO action plan ......................................................................................................................... 119

2014-2015......................................................................................................................................... 119

2015-2016......................................................................................................................................... 119

2016-2017......................................................................................................................................... 119

2017-2018......................................................................................................................................... 120

2019-2020......................................................................................................................................... 120

2021-2022......................................................................................................................................... 120

2022-2023......................................................................................................................................... 121

2023-2024......................................................................................................................................... 121

Chapter 8: Conclusion .............................................................................................................................. 122

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................. 123

References ................................................................................................................................................ 125

Appendix A ............................................................................................................................................... 131

Appendix B................................................................................................................................................ 138

Appendix C................................................................................................................................................ 140

Appendix D ............................................................................................................................................... 142

9

�List of Figures

Figure 1. Photograph from website of handling human remains inside a cave on Saipan

(http://saipanpictures.blogspot.com/2010/05/caves-in-saipan.html, accessed February 2014). 16

Figure 2. Photograph from website of handling human remains inside a cave on Saipan

(http://saipanpictures.blogspot.com/2010/05/caves-in-saipan.html, accessed February 2014). 16

Figure 3. Photograph from website of handling WWII artifacts inside a cave on Saipan

(http://saipanpictures.blogspot.com/2010/05/caves-in-saipan.html, accessed February 2014). 16

Figure 4. Invasion beaches of Saipan (Ships of Discovery 2009). .................................................. 20

Figure 5. Study area as defined by KOCOA analysis (McKinnon 2014). ........................................ 26

Figure 6. Core area as defined by KOCOA analysis (McKinnon 2014). .......................................... 27

Figure 7. Sketch of a series of H-caves found in Peleliu (Phelan 1945:7)...................................... 31

Figure 8. Sketch of U-cave found in Peleliu (Phelan 1945:7). ....................................................... 31

Figure 9. Sketch of Y-cave found in Peleliu (Phelan 1945:11). ...................................................... 32

Figure 10. Map of approximate cave locations based on Operation Forager accounts (H. Burke

2013).............................................................................................................................................. 35

Figure 11. Project team. Front Row: Genevieve Cabrera; Middle Row, Left to Right: Jun Kimura,

Jason Raupp, Jennifer McKinnon, and Julie Mushynsky; Back Row, Left to Right: Heather Burke,

Herman Tudela, and Betty H. Johnson (missing from photo Toni Carrell, Fred Camacho, and John

San Nicolas). .................................................................................................................................. 37

Figure 12. General geology of Saipan (Carruth 2003). .................................................................. 40

Figure 13. Cross-section of geological section on Saipan (Carruth 2003). .................................... 41

Figure 14. Locations of cave development on carbonate islands. Category D (complex island)

represents Saipan's carbonate island karst model (Stafford et al. 2002:2). ................................. 42

Figure 15. Skulls in Kalabera ca. 1920s (Hans Hornbostel Collection; Cabrera 2009:18).............. 44

Figure 16. "Man in canoe" pictograph in Kalabera Cave - 8cm scale (J. Mushynsky 2012). ......... 45

Figure 17. "Headless man" pictograph in Kalabera Cave - 8cm scale (J. Mushynsky 2012).......... 45

Figure 18. "Gecko/lizard" pictograph in Kalabera Cave - 8cm scale (Julie Mushynsky 2012). ...... 46

Figure 19. Supply and storage uses for caves: food and other stores inside a Saipan cave

(www.ww2incolor.com). ............................................................................................................... 49

Figure 20. Natural cave enhanced by Japanese (Department of Defense USMC 83566). ............ 53

Figure 21. Marines using flamethrower in the approach to Paradise Valley, the Marianas

(www.ww2incolor.com). ............................................................................................................... 54

Figure 22. War memorial by the MHLW on Saipan (http://www.mhlw.gov.jp). .......................... 57

Figure 23. Current state of recovered human remains in the Asia-Pacific region

(http://www.mhlw.go.jp, accessed 20 Jan 2012). ........................................................................ 58

Figure 24. Uncle John's Cave entrance, note reinforced cement on entrance (J. McKinnon 2013).

....................................................................................................................................................... 62

10

�Figure 25. Shell on downward slope outside Uncle John's Cave (J. McKinnon 2013). .................. 62

Figure 26. Sinkhole containing Uncle Frank Diaz's Cave (J. Mushysnky 2013). ............................. 63

Figure 27. Opening of cave (J. Raupp 2013). ................................................................................. 64

Figure 28. Inside cave looking out at entrance (J. McKinnon 2013). ............................................ 64

Figure 29. Tea kettle (J. McKinnon 2013). ..................................................................................... 65

Figure 30. Japanese ceramics (H. Burke 2013). ............................................................................. 66

Figure 31. Norbert Diaz standing in the cave (G. Cabrera 2013)................................................... 66

Figure 32. WWII era metal artifacts including a fuel container, bucket and cooking pot (G.

Cabrera 2013). ............................................................................................................................... 67

Figure 33. Norbert Diaz rappelling into his cave (H. Burke 2013). ................................................ 68

Figure 34. Fish and Wildlife sign outside hospital cave entrance (J. Musynsky 2013). ................. 69

Figure 35. Inside the hospital cave looking out with team member standing on rock wall (J.

McKinnon 2013). ........................................................................................................................... 70

Figure 36. Outside the hospital cave looking in with concrete platform in foreground (J.

McKinnon 2013). ........................................................................................................................... 70

Figure 37. Hospital cave entrance, note cement platform in background (G. Cabrera 2013). ..... 71

Figure 38. Memorial offering in back of hospital cave (J. McKinnon 2013). ................................. 71

Figure 39. Walking into the second cave entrance (H. Burke 2013). ............................................ 72

Figure 40. Looking out from the second cave (J. Mushynsky 2013). ............................................ 72

Figure 41. Wooden stupa in the second cave (H. Burke 2013). .................................................... 73

Figure 42. Concentration of artifacts in second cave (likely collected and placed in location) (J.

Mushynsky 2013). ......................................................................................................................... 74

Figure 43. View looking out of cave (H. Burke 2013). ................................................................... 75

Figure 44. Green bento box lid (J. Kimura 2013). .......................................................................... 76

Figure 45. Alcohol bottles (J. Kimura 2013)................................................................................... 76

Figure 46. Rockshelter (J. McKinnon 2013). .................................................................................. 77

Figure 47. Tunnel with Ayuyu family members (J. Mushynsky 2013). .......................................... 77

Figure 48. Gas mask and components (H. Burke 2013). ............................................................... 78

Figure 49. WWII era artifacts outside of tunnel (H. Burke 2013). ................................................. 79

Figure 50. Cave entrance (J. McKinnon 2013). .............................................................................. 80

Figure 51. Rock art (J. Kimura 2013). ............................................................................................. 80

Figure 52. Wooden barrel parts (J. Kimura 2013). ........................................................................ 81

Figure 53. Hair comb (J. Kimura 2013). ......................................................................................... 81

Figure 54. Bottle and shoe parts (J. Kimura 2013). ....................................................................... 82

Figure 55. Entrance to cave (G. Cabrera 2013). ............................................................................ 83

Figure 56. Looking out from the inside of cave (J. McKinnon 2013). ............................................ 83

Figure 57. Indigenous mortar fragment (J. Mushynsky 2013). ..................................................... 84

Figure 58. Haphazard tin can pile (J. Mushynsky 2013). ............................................................... 84

Figure 59. Japanese ceramics (H. Burke 2013). ............................................................................. 85

Figure 60. Metal drum and gray ash (H. Burke 2013). .................................................................. 85

Figure 61. Naftan cave entrance and memorial offerings (J. Mushynsky 2013). .......................... 86

Figure 62. Small, restricted cave entrance (J. McKinnon 2013). ................................................... 87

11

�Figure 63. Team member standing inside rock ring (H. Burke 2013). ........................................... 88

Figure 64. Second small cave (H. Burke 2013). ............................................................................. 88

Figure 65. Entrance to cave, note the mermaid statue immediately outside the entrance (H.

Burke 2013). .................................................................................................................................. 89

Figure 66. Inside cave looking out (H. Burke 2013). ...................................................................... 90

Figure 67. Scaffolding bridge erected inside cave (H. Burke 2013). .............................................. 90

Figure 68. Hair comb (H. Burke 2013). .......................................................................................... 91

Figure 69. Wall of pocket caves (J. Mushynsky 2013). .................................................................. 92

Figure 70. Gathered artifacts and memorials (J. Mushynsky 2013). ............................................. 92

Figure 71. Gathered human remains (J. Mushynsky 2013). .......................................................... 93

Figure 72. Genevieve Cabrera at the entrance of her family's cave (J. McKinnon 2013). ............ 94

Figure 73. Inside the large open space beneath the road bed (H. Burke 2013). .......................... 95

Figure 74. Adult and child shoe soles (J. Mushynsky 2013). ......................................................... 95

Figure 75. Chalan Galadi cave (J. McKinnon 2013)........................................................................ 96

Figure 76. Inside the cave suspected to be used by Esco (J. Mushynsky 2013). ........................... 97

Figure 77. Graffiti panel 1 with canoe pictograph (Swift et al. 2009:71). ..................................... 99

Figure 78. Graffiti panel 2 with canoe pictography (Swift et al. 2009:72). ................................. 100

Figure 79. Cow inside the Ayuyu family tunnel (H. Burke 2013). ................................................ 102

Figure 80. Newspaper advertisement announcing public meetings (J. McKinnon 2012). .......... 105

12

�List of Tables

Table 1. Mariana Island natural cave types, descriptions and locations (Mylroie and Mylroie

2007:61-62; Stafford et al. 2002:11-13). ....................................................................................... 43

Table 2. Number of individuals recovered since 2007 (http://www.mhlw.go.jp). ....................... 58

Table 3. Recovery missions by date (http://www.mhlw.go.jp)..................................................... 59

Table 4. Identification results for DNA analysis (http://mhlw.go.jp). ........................................... 60

Table 5. Conservation areas of Saipan. ....................................................................................... 108

13

�Acknowledgements

This project would not have occurred without the help of a number of individuals and groups.

First and foremost we would like to thank the CNMI Historic Preservation Office for their

continuous support. Special thanks are extended to Herman Tudela (no longer at HPO) and “JP”

John Palacios.

The agencies and organizations that have supported this project on island include: the National

Park Service American Memorial Park; the NMI Humanities Council; and Power 99.

Thank you to the volunteers on the project as well as general support while on island: John D.

San Nicolas, Scott Eck, Betty H. Johnson, and Fred Camacho.

Thank you to the archeological team for your assistance and knowledge: Jason Raupp, Heather

Burke, Genevieve Cabrera, Herman Tudela, Jun Kimura and Julie Mushynsky.

Thank you to the local community who were very enthusiastic and supportive of this project and

protecting their heritage.

Special thanks go to Flinders University for providing staff time and equipment, and East

Carolina University for providing staff time to this project.

Thank you to Windward Media for their support and assistance with this project and the fine

products they produce.

A big thank you should be extended to the American Battlefield Protection Program for

providing the funding for this project. We would particularly like to thank Kristen McMasters for

her availability and willingness to help us through this process.

Jennifer McKinnon, Greenville, NC

Toni Carrell, Santa Fe, NM

14

�Chapter 1: Introduction

This project involved a planning and consensus-building effort focused on the protection of

threatened caves on private property that were occupied and used prior to, during and after the

WWII Battle of Saipan by Japanese and US troops and civilians. The project was designed to

assess local interest in protecting sites on private property and sought to increase awareness

and advocacy of their protection into the future. This was accomplished through a series of

public meetings, consultation with land owners, Historic Preservation Office (HPO), National

Park Service (NPS), and other stakeholders, and the development and implementation of radio

and television (TV) public service announcements (PSAs) that focus on the conservation and

protection of cave sites.

This project was developed as a result of local and international concern for archeological cave

sites on Saipan. A range of cave types exist in various forms from natural, to modified, to fully

human-made intricate tunnel systems. Due to the excellent preservation environment of caves,

these sites still contain valuable historical and archeological material culture and context which

is actively being compromised and destroyed by cave explorers, souvenir hunters and tourists.

During 2010 while Ships of Exploration and Discovery Research, Inc. (Ships) archeologists were

on island conducting research as part of a previous ABPP grant, it was reported that

photographs of cave sites and their locations were being publicized on the Internet through a

private blog (http://saipanpictures.blogspot.com/2010/05/caves-in-saipan.html), a Flicker

account (https://www.flickr.com/photos/saipanpictures/sets/72157623893765702/) and on

YouTube (http://www.youtube.com/user/SaipanPictures?feature=watch). The photographs and

videos show individual(s) picking up both artifacts and human remains, which is prohibited by

both Commonwealth and Federal law (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). This raised concern with

the HPO and NPS about access to sites and their protection, particularly on private property. It

also alarmed local Indigenous community members who were concerned with the publication of

Indigenous rock art on the Internet. Inappropriate or unmonitored public access to archeological

sites can contribute to an overall loss of archeological and historical context and affect the

structural integrity of the sites and their long-term survival, particularly if individuals are seeking

to remove or move artifacts. Whether harm is intentional or unintentional these impacts are

irreversible and therefore an understanding of public access is crucial to developing a plan for

how these sites can be protected and managed.

15

�Figure 1. Photograph from website of handling human remains inside a cave on Saipan

(http://saipanpictures.blogspot.com/2010/05/caves-in-saipan.html, accessed February 2014).

Figure 2. Photograph from website of handling human remains inside a cave on Saipan

(http://saipanpictures.blogspot.com/2010/05/caves-in-saipan.html, accessed February 2014).

Figure 3. Photograph from website of handling WWII artifacts inside a cave on Saipan

(http://saipanpictures.blogspot.com/2010/05/caves-in-saipan.html, accessed February 2014).

Further, because many of these sites are on private property owned by Chamorro and Carolinian

peoples it is crucial to gauge their understanding of these sites, what values they hold and how

they might be involved in their protection into the future. Involving the community in this effort

is vital to the success of any plan for protecting sites. Local voices must be heard and considered

and the local community must be at the center of the movement to protect these sites.

Over the course of the project, researchers from Ships and Flinders University (FU) traveled to

Saipan several times to evaluate the caves, conduct research, speak with stakeholders, hold

community meetings and produce PSAs. The preservation plan for the Battle’s caves is based on

thorough evaluation of the resources. It also incorporates the ideas, wants and needs of the

community and stakeholders as expressed in the individual and community meetings concerning

the future of the sites and battlefield. Protection for significant cave sites rests solely in the

16

�hands of local landowners and the government agencies charged with managing these

resources. Outlined within this plan are strategies for addressing preservation through

partnership opportunities and as well as information about financial and technical sources of

support.

The ABPP’s willingness to fund this plan demonstrates that preserving these caves and

battlefield is more than a local initiative and that the NPS understands the significance of the

battlefield and the importance of preserving it into the future. This project demonstrates to the

NPS that the community is also serious about preserving the cave sites on their island. It is the

purpose of this plan to provide a blueprint for future preservation efforts.

The Battle of Saipan 1911-1944 (after Burns 2008)

As destructive as World War I was in other parts of the world, the Mariana Islands were spared.

Still, the end of the war had important ramifications for the islands. The League of Nations

approved Japan’s occupation of the Mariana (sans Guam), Caroline, Marshall, and Palau Islands

in 1921 with the stipulation that Japan not develop fortifications in the region. For over a

decade Japan complied with the agreement and focused on infrastructural development that

strengthened the economy of their possessions.

Increasingly expansionist, Japan sought to strengthen its presence in the Pacific in the late

1930s. For example on Saipan, Aslito Airfield on the southern end of the island and a seaplane

base at Flores Point (northeast of Garapan) were constructed. Japan withdrew from the League

of Nations in 1933 which abrogated their agreement. Barracks, ammunition storage, air raid

shelters, and other facilities preparatory for an offensive war were installed elsewhere on

Saipan in 1941 (Russell 1984).

Japanese Defences on Saipan

The Japanese defensive strategy used for Saipan and the other Mariana Islands was identical to

that of earlier battles at the Gilbert and Marshall Islands: the enemy was to be met and

destroyed at the beaches and, if allowed inland, they were to be pushed into the sea by way of

counterattacks (Denfeld 1992). Prior to the outbreak of the war, Japan’s need for troops and

material elsewhere in the Pacific hampered the pace of developments on Saipan and the other

islands of the Marianas. The Japanese forces established two bases on Saipan by early 1944. The

airfield at Aslito (built in the 1930s) served as a repair and maintenance facility for aircraft

involved in battles to the east and south. At Tanapag Harbor, a naval base served as a staging

area for troops and ships bound elsewhere (Denfeld 1992). Due to needs in other parts of the

Empire, Japanese troop numbers were fairly low; in early February 1944, there were only 1,500

troops on Saipan.

The impending US campaign against the Marianas hurried Japanese defensive measures and by

the end of February thousands of troops were sent to the Marianas to prepare for Battle. US

submarine attacks on Japanese transports prevented an estimated 2,000 troops from reaching

the islands (Denfeld 1992), but by early June some 30,000 troops were prepared for Battle on

Saipan (Rottman 2004b).

Once they had sufficient troops and materials available, the Japanese forces commenced

defensive improvements on Guam, Tinian, Rota, Pagan, and Saipan. On Saipan, another airfield

was built by Lake Susupe near the town of Chalan Kanoa, but this was little more than an

17

�emergency landing strip. More airstrips were planned on Saipan and throughout the islands, but

most were never completed (Denfeld 1992). Forty-six gun installations were established on the

beaches and ridges of Saipan, but twelve were not operational on D-Day. An additional three

units lay on railcars awaiting installation at the start of the Battle and another 42 were in

storage at the Navy base at Tanapag. Construction of three blockhouses on the beaches of

Saipan, each a concrete structure with four ports housing heavy guns, began in early 1944.

Between Obyan Point and Agingan Point stand two of the three blockhouses. The third is at

Laulau Bay (Purple Beach). None of the three blockhouses housed the large guns intended for

the fight against US forces. (Denfeld 1992).

The Mariana Islands in WWII, 1941-1944

Across the Pacific, word spread that war was coming, however, only Japan knew when and

where it would start. Shortly after the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii,

Japanese forces initiated air attacks over Guam, which they had been openly monitoring since

November. Commercial airline buildings, fuel supplies, the US Navy yard, vessels in Apra Harbor,

and the capital at Agana were bombed. Poorly defended by the US, Guam fell on 10 December

within six hours subsequent to the Japanese invasion. Guam became the only part of the US to

fall under enemy occupation during WWII. With this prize under its belt, the Japanese Imperial

Army and Navy mounted very successful aggressive operations across the Pacific in the early

years of the war (Rogers 1995; Rottman 2004a).

As these events were occurring in the Marianas, Allied powers meeting in Egypt agreed upon a

Pacific strategy consisting of two offensive drives. The first, led by General Douglas MacArthur,

was an advance from New Guinea to the Philippines. The second, led by Admiral Chester Nimitz,

was a push through the Gilbert and Marshall Islands across the Central Pacific to take the

Marianas. Once accomplished, a strategic bombing campaign could be mounted against the

Japanese mainland. By the start of 1944, this broad strategy proved successful for the US and

the Japanese government realized an invasion of the Marianas was imminent. As Marine

historian O.R. Lodge wrote, “A strangling noose was tightening around the inner perimeter

guarding the path to their homeland” (Lodge 1954).

Operation Forager

The US’s plan to take control of the Marianas from Japanese forces was code-named Operation

Forager and included the island of Guam. The plan to invade and take control of Saipan was

called Operation Tearaway. This massive operation involved thousands of troops from all

branches of the military and a bewildering number of vessels, vehicles, and weapons. Japan’s

defenses focused on five islands in the Marianas: Guam, Rota, Tinian, Saipan, and Pagan. Saipan,

home of the administrative center of the Japanese Marianas, was chosen as the first target with

Tinian and Guam as secondary. US war planners opted to bypass a full assault on Rota and

Pagan (Rottman 2004a).

Air attacks were the first phase of Operation Forager. In February 1944, US bombers destroyed

the Orote Peninsula airstrip on Guam. General air raiding also began across the Marianas,

resulting in US dominance of the skies. In response, Japanese forces prepared Operation A-Go,

which relied upon the support of the Imperial Japanese Navy and air forces to support troops on

the ground in the Marianas.

18

�Operation Forager was in full swing by June 1944 when the invasion of Saipan was planned. The

invasion was set for June 15, D-Day. Responsible for this task was the Marine V Amphibious

Corps (VAC) that consisted of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, the 27th Infantry Division (Army),

and the XXIV Corps Artillery (Army). US military planners considered landing points on all sides

of Saipan. On the eastern side of the island, an area designated Brown Beach on the Kagman

Peninsula was considered but rejected because it was well-defended and would offer a poor

exit. Three other beaches, Purple Beach on Magicienne Bay and White Beach 1 and 2 near Cape

Obiam on the southern reach of the island, were kept as alternates. At Tanapag Harbor were the

well-defended Scarlet Beaches 1 and 2, and to the north of this area were Black Beaches 1 and

2, which offered insufficient space for the large unit landing that was planned (Rottman 2004a).

The lower western side of Saipan was chosen as the primary invasion area. Stretching

approximately four miles and divided into several zones, this area was most favorable because

the size would allow two Marine divisions to land simultaneously. A landing here also allowed

the immediate capture of the airstrip at Chalan Kanoa placing direct pressure on nearby Aslito

Airfield. Once secure, these air strips were used to support the penetration northward across

Saipan. Afetna Point divided the landing beaches. To the north were Red Beaches 1, 2, and 3 and

Green Beaches 1 and 2 while to the south were Green Beach 3, Blue Beaches 1 and 2, and

Yellow Beaches 1, 2, and 3 (Rottman 2004a) (Figure 4).

As favorable as the lower western side of Saipan was for the US invasion, certain limitations

remained. Because of its distance from the northern sector of the island, beaches in this area

(Scarlet 1 and 2 and Black 1 and 2) had to be captured in order to facilitate the off-loading of

supplies from landing craft. Another problem at the beaches off the lower western side of

Saipan was the extensive coral reef that abutted the shore. These had to be negotiated with

amphibious vehicles including AMTRACS or Landing Vehicle Tracked (LVTs) and amphibious

tanks, also known as Landing Vehicle Tanks (LVT(A)s). Both the 2nd Marine Division and the 4th

Marine Division had three AMTRAC battalions each, plus one amphibian tank battalion, for the

initial shore assault. This amounted to approximately 1,400 AMTRACS, the largest use to date of

amphibious vehicles. Once ashore, the AMTRACS were required to push inland from the beach,

a tactic that was equally unprecedented and also potentially dangerous. AMTRACS, with their

thin armor and low ground clearance, were not designed for cross-country movement.

19

�Figure 4. Invasion beaches of Saipan (Ships of Discovery 2009).

The Battle of Saipan – Operation Tearaway, 1944

An intensive barrage presaged the beach invasion foreshadowing the massive confrontation

that was set for June 15. On June 12, 200 carrier aircraft bombed Japanese airfields in the

southern Marianas, decimating the enemy’s air force. That same day, US B-24 bombers began

around-the-clock raids on Saipan and Tinian. The following day (June 13), seven fast battleships

leveled the towns of Chalan Kanoa and Garapan and on June 14, more battleships as well as 11

cruisers and 26 destroyers attacked Japanese coastal defenses.

20

�On June 14, other crucial preliminary actions took place along the coast of Saipan. Early that

morning, Underwater Demolition Teams began their mission to demolish reefs, enemy mines,

and mark lanes along the Red, Green, Blue, and Yellow beaches. This effort was largely

successful. Simultaneously, a mock attack was held by a “Demonstration Group” off the

northwestern coast at Scarlet and Black beaches (refer to Figure 1) in an attempt to trick the

Japanese into thinking that the invasion was to occur there. Another was held in the early

morning hours of June 15, D-Day. The Demonstration Group consisted of the 2nd Marines, the

1st Battalion, 29th Marines, and the 24th Marines. The feint was supported by naval gunfire as

landing craft approached the beach to within 5,000 yards, circled for a few minutes, wheeled

about, and returned to their ships. Troops were not embarked, the landing craft drew no fire,

and no activity was observed on the shore. Although clearly not convinced by the ploy, the

Japanese stopped short of removing troops from here and redeploying them to other beaches.

Interestingly, Japanese commanders did wire Tokyo to report that they had repelled an invasion

in this area (Rottman 2004a).

As the sun rose on June 15, the enormous US amphibian force was assembled for the invasion.

AMTRACS and DUKWs were unloaded and LSDs (Landing Ship, Dock) launched LCMs (Landing

Craft, Mechanized) that held tanks. Battleships, cruisers, and destroyers closed in on the

invasion beach with aircraft screaming overhead toward the shore. With nearly 1,500 vessels in

all, this great unpacking of men, weaponry and ammunition was surely an intimidating sight for

the Japanese forces and the islanders. At exactly 0830 hours, the AMTRACS carrying hundreds of

marines stormed for the beach as supporting ships and aircraft opened fire. The Japanese

troops generally held their fire until the AMTRACS reached the lip of the coral reef when they

poured artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire on the Marines. Due to the condition of the seas,

the Marines had a great deal of difficulty reaching the beach. Numerous AMTRACS were

rendered inoperable or destroyed as a result. Dozens of Marines lost their lives when AMTRACS

were overturned in the rough surf, but by 0900 hours nearly 8,000 Marines were ashore (Crowl

1960; Rottman 2004a).

The beaches, especially the northern Red and Green Beaches, were chaotic and crowded.

Because of the heavy swell and long shore current, the US landing in this area was several

hundred yards north of its intended location. In all areas Japanese fire was very heavy and came

from the high ground beyond, as well as trenches and spiderholes along the immediate

shoreline. The overland AMTRAC charge, a calculated risk, proved disastrous as the flimsy

AMTRACS became stranded in marshy areas, craters, and other obstructions on the ground. As

casualties for the Marines mounted, many chose to abandon their machines in favor of walking

or crawling. Problems increased as the morning wore on. At the northern beaches, two 2nd

Marine Division command posts were destroyed, killing battalion commanders and key staff and

on the south, the 4th Division indecisively struggled with Japanese tanks for hours. The arrival of

US tank battalions, howitzer batteries, and other support forces improved the overall situation

by the end of the day, although the beachhead remained unconsolidated. On this day, the first

of the battle for Saipan, some 2,000 Marines were killed. Mortar and artillery fire were the

principal causes of death. Offshore hospital vessels were completely overwhelmed and

wounded men were transferred to other, non-hospital ships for treatment (Crowl 1960;

Rottman 2004a).

Over the next two days, the Marines secured and expanded the beachhead. The morning of

June 16 was spent closing the gap between the two divisions, which were separated by a strong

21

�Japanese force on Afetna Point. By noon, this goal was accomplished. A huge Japanese

counterattack was successfully repelled that afternoon and the Marines engaged in the largest

tank battle of the Pacific War. Aslito Airfield was under pressure at the close of the day. In

contrast, the 27th Infantry Division (Army) came ashore to support the Marines on the morning

of June 17 and bore the brunt of a door-to-door fight through Garapan village, another

innovation in the Pacific War.

After the beaches were secured, support groups landed on the beachheads to facilitate the

massive unloading of supplies. The post-invasion landscape they witnessed was grim. Disabled

AMTRACS and boxes of c-rations were scattered across the beach. Bodies of dead Marines that

were not yet recovered bobbed in the surf. “The leaves on battered trees and underbrush were

covered with a fine, gray dust,” wrote former Naval Construction Battalion (Seabee) commander

David Moore. “This whole scene gave an eerie feeling of war” (Moore 2002).

On the evening of D-Day, Seabees were ordered to launch the floating causeways held in the

LSTs (Landing Ship, Tanks). Throughout the night, the Seabees maneuvered the various pieces

through the channel and assembled them at the Chalan Kanoa beachhead. By daybreak supplies

were being unloaded from landing craft. Other craft towed pontoon sections that were made

into floating piers to unload supplies. Pontoon barges were used to haul ammunition. While vital

to the continued success of the American operation on Saipan, unloading supplies and

ammunition from barges on the beachhead became monotonous as combat moved farther

inland. This “grueling mission of moving ammunition and other supplies to the beach…became a

routine of eating bland c-rations and sleeping on the barge for a boring 54 days of blazing sun or

miserable rain,” remembered one Seabee who served at Saipan. “The Coxswain often grumbled:

it is noble to suffer. We [the Seabees] were granted the undistinguished title, ‘Bastards of the

Beaches’” (Moore 2002).

There were nevertheless many soldiers on the mainland that would have traded places with the

Seabees. Japanese attempts to call in reinforcements from neighboring islands were fruitless,

but they continued to fight with resolve. On June 18, they attempted a daring counter-landing

from their tattered Navy base at Tanapag Harbor. Japanese infantrymen were hastily loaded

onto 35 barges and sent toward the US landing beaches. In route, US infantry gunboats and

Marine artillery intercepted them, destroying many and deterring all. A larger-scale encounter

played out in the Philippine Sea between June 19 and 20 when the US Navy defeated the

Japanese Imperial Navy in what is known at the “Marianas Turkey Shoot.” In the meantime, the

US secured Aslito Airfield and the southern reaches of the island and prepared the northward

fight (Crowl 1960; Rottman 2004a).

More gruesome scenes followed in this monstrous battle as June became July and US troops

pushed deeper into the island of Saipan. Garapan was secured on July 3, the Tanapag seaplane

base on July 4, and on July 6 the Japanese forces staged their last massive banzai charge. After

Saipan, Japanese commanders deemed such suicidal charges as wasteful. Rarely effective, they

were not used in later battles. Through mountainous terrain, tropical conditions, and intense

resistance, US forces reached the northern end of Saipan at Marpi Point on July 9, 1944 (Crowl

1960; Rottman 2004a).

22

�The aftermath of the Battle of Saipan

The loss of life during the Battle of Saipan was tremendous. Approximately 3,426 of the 67,451

US troops who participated in the Battle were killed or reported missing in action. Four times

this number were confirmed wounded. Japanese losses were far greater. Of the approximately

31,629 Japanese troops who participated in the Battle, 29,500 were killed or missing (Rottman

2004b). Japanese sources, however, estimated the total number killed on Saipan to be well over

40,000 (Bulgrin 2005).

The long-fought and costly victory at Saipan, the fiercest of the three major battles in the

Marianas, was politically and militarily decisive. US successes in the opening two weeks of the

Battle induced Japanese Emperor Hirohito to attempt a diplomatic end to the war. When news

of Saipan’s fall reached Japan, political pressure forced Prime Minister, War Minister, and Chief

of Army General Staff Tojo Hideki and his cabinet, as well as Navy officials, to resign (Rottman

2004a).

Equally as important to the decisiveness of the victory at Saipan was the island’s proximity to

Japan. This was also true of Guam and Tinian. The Mariana Islands were ideal for the

development of bases for long range, B-29 bombers that were capable of reaching the Japanese

mainland. On Saipan, the US wasted no time in developing these bases. Aslito Airfield was

renamed Conroy Field and then Isely Field. By December 1944, it was used as the main

operating field on the island. Two new airfields, Kobler Field and another at Kagman Peninsula,

were also built at this time. The seaplane base at Flores Point was rebuilt and improvements

were made to the Marpi Point airfield.

Saipan and the Mariana Islands paved the road for more decisive battles at Okinawa and Iwo

Jima. Together, the great sacrifices of these and other battles of the Pacific War gave US military

planners an impression of what could be expected from an invasion of the Japanese mainland.

Plans for such an invasion were in the making when the decision was made to drop the atomic

bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, resulting in the surrender of the Japanese Empire and the

conclusion of WWII.

23

�Chapter 2: The Battlefield Today

The Saipan battlefield retains considerable integrity in certain areas of the island and the

viewshed from many points is excellent and a constant reminder of the activities that took place

during 1944. Locals and visitors are reminded of the Battle daily by the remnants of the war,

such as tanks and guns scattered inland and along the coastline, pre-war and WWII Japanese

structures covering the island and large and small caves hidden in the bush. While the island is

easily recognizable as a battlefield site, it has also been the location of years of development

and commercial and private building which can obscure prominent features and sites.

The battlefield

Three battlefield boundaries were addressed as a result of the application of KOCOA analysis in

a 2009-2010 project that assessed the significance of the central and northwestern portions of

waters surrounding Saipan (McKinnon and Carrell 2011). These include:

1. Study Area, which encompasses the ground over which units maneuvered in

preparation for combat;

2. Core Area, which defines the area of combat; and

3. Potential National Register Boundary (PotNR), which contains only those portions of the

battlefield that have retained integrity.

In most cases KOCOA has been applied to Revolutionary and Civil War battlefields which are

clearly bounded and defined (Legg et al. 2005; Bedell 2006; GAI Consultants 2007; Fonzo 2008).

These conflicts, lasting one to several hours, were brief encounters on a discrete portion of land.

Combat consisted of hand-to-hand combat and close range artillery, such as guns and cannon. In

the survey and analysis of this type of battlefield site archeologists are dealing with a short

moment in time and an enclosed space. Conversely, the battle for Saipan was several months

long if aircraft bombing missions are considered, or, if only the ground invasion is considered, a

three week engagement that slowly spread across an island 115 km2 in size. Further, it was not

only fought over land, but also in the surrounding lagoon and sea and in the airspace above. This

type of combat was made possible through advances in combat vehicles and aircraft and

increased artillery range.

Study area

The study area for the Battle of Saipan is much larger than the island of Saipan and its

immediate surrounding waters. Broadly speaking, the approach to the island from Pearl Harbor

where the expeditionary forces left on 5 June 1944 could be considered part of the study area;

however this space will not be included for the purposes of this project. Rather the study area

encompasses the waters and airspace above the adjacent Philippine Sea, approaches to the

island, the island, and the immediate surrounding waters that both US and Japanese forces used

to maneuver and prepare for battle (Figure 5). For example, the US and Japanese forces utilized

the sea and airspace to conduct aerial and underwater reconnaissance and to position

themselves strategically in the lead up to and during the Battle of Saipan. Historical records

indicate that several reconnaissance missions both in the air and underwater were launched by

the US in early 1944. Further, Japanese forces conducted their own reconnaissance flights to

gain more knowledge about the invading US forces. There are also records of the US using

diversionary tactics such as a mock attack prior to invasion and on the day of invasion. These

demonstrations, maneuvers, staging, and reconnaissance activities all can be considered part of

the study area of the Battle of Saipan.

24

�Core area

The core area for the Battle of Saipan is similar in scope to the study area of Saipan, particularly

on the western side of the island. This research has defined the core area as the space in which

either side engaged in combat in the form of hand-to-hand, close range, and long range

weaponry. For example, the offshore position from which US shelling and bombardment

occurred several days prior to the invasion of the island is considered part of the core area, as is

the space just outside of and above the lagoon where aircraft strafed and bombed surface

vessels and other aircraft. Thus the core area incorporates the whole island of Saipan as well as

those spaces on the water and in the air where combat occurred (Figure 6).

The study and core area for this project has not been altered and will remain the same as

previous projects.

Potential National Register boundary

The WWII landing beaches on the west coast, Aslito/Isley Field in the south and Marpi Point in

the north were listed on the NRHP and designated a National Historic Landmark (NHL) on

February 4, 1985. The NHL encompasses 1,366 acres of land and water (Thompson 1984). The

NHL was designated based on the history and integrity of the areas; however, no archeological

fieldwork was conducted. (See Thompson’s [1984] nomination for sites located within the

Landmark). It was not within the scope of this project to delineate a second or expanded

boundary for this area. Further, because this project did not cover the entire battlefield, but

only specific cave properties on private lands, the integrity of the battlefield cannot be assessed

for those areas not surveyed. Nevertheless, the individual sites that were surveyed can be

assessed on a case-by-case basis for archeological integrity (see following chapters).

25

�Figure 5. Study area as defined by KOCOA analysis (McKinnon 2014).

26

�Figure 6. Core area as defined by KOCOA analysis (McKinnon 2014).

27

�Previous cave research in the Mariana Islands

While the existence of cultural remains in cave sites has been documented by numerous

researchers over the past one hundred years, few projects have focused specifically on caves. To

date there has been no systematic island-wide archeological survey of caves on Saipan and

there are very few published works on archeology conducted in caves. Like most other Pacific

islands where caves have been documented by archeologists, it has generally been undertaken

only when they are encountered though cultural resource management projects or surveys of

WWII battlefield sites. Although in many other parts of the world archeological research in cave

environments has been considered highly important and excavations have provided new

information about local cultural histories, until recently caves sites on Saipan have been given

little attention.

Following the end of WWII, the islands of Micronesia were established as a trusteeship of the

United Nations and were known as the Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands, which were

administered by the US. Apart from Guam, which became a Territory of the US in 1898, the

Northern Marianas existed under Trust Territory status (18 July 1947) until they were declared a

Commonwealth of the US in 1976. During the Trust Territory period little archeological research

was conducted on the Northern Marianas aside from the 1949-1950 Chicago Natural History

Museum investigations conducted by Alexander Spoehr. This project involved excavations on

the archipelago’s three southern islands and the results of these formed the basis for Spoehr’s

major work entitled Marianas Prehistory: Archaeological Survey and Excavations on Saipan,

Tinian and Rota (1957). This seminal volume included not only descriptions of his excavations

and discussions of the results, it provided brief discussions of previous research that had been

carried out in the pre-war period. Of interest in this discussion is the reference to Laura

Thompson’s investigations of cave sites on both Tinian and Saipan, though no further

information about her research is given. Spoehr’s own surveys included the investigation of 25

limestone caves on Saipan and numerous others on Tinian (Spoehr 1957). However, all but one

of these were found to have been disturbed “by Japanese defense forces and converted into

machine gun positions and military strong points for the defense of the island during the

American invasion” (Spoehr 1957:29). The only cave site to be excavated and documented by

Spoehr was the Laulau Shelter site, which is located near the large bay of the same name on the

island’s east side. Excavations at the site indicate that it was used primarily as a place for burial

and cremation; just under the topsoil a thick stratum of densely packed ashes and fragments of

charred human bones, some plain pottery and three shallow burial pits was found. Below this

layer several other burial pits where found in a clay layer that was devoid of artifacts other than

those associated with the burials. These contained the remains of several adults and children, as

well as ceramics that predate those found in the upper level (Spoehr 1957:52-58). Spoehr

(1957:52) also mentions that the surface in the northern part of this cave had been cleaned out

by Japanese forces and that it was used as a military strong point.

Dave Lotz (1998) documented over 400 WWII related resources in Guam, Rota, Tinian, Saipan,

and Aguiguan in World War II Remnants – Guam, Northern Mariana Islands: A Guide and

History. Lotz’ survey and publication contain a few of the cave and rock shelter sites, but little indepth research was conducted other than noting their locations.

28

�The next research project that focused directly on the archeological investigation of Saipan’s

caves was carried out by Genevieve Cabrera and Herman Tudela of the CNMI Historic

Preservation Office. Cabrera and Tudela conducted a research project on Indigenous rock art

located in various caves around the island, but primarily reported on Kalabera Cave. They

outlined the historical, cultural and archeological significance of cave sites and rock art, and

provided a useful interpretation of the imagery, which they supported with archeological

evidence and Indigenous oral histories (Cabrera and Tudela 2006).

The private consulting firm SHARC conducted both archeological and environmental

assessments of the well-known Kalabera Cave site in 2009/2010 when government plans were

considered for developing the cave into a tourist attraction (Swift et al. 2009). The government

plans proposed several option for tourism development including a full-scale tourism operation

with food venues, parking, etc. SHARC’s survey and excavation focused primarily on Indigenous

use and occupation of the cave system; however they provided significant information regarding

management options for cave sites. Their report should be consulted with regards to any future

research on cave sites. Also, in conjunction with the work by SHARC, the LAMAR Institute

conducted a GPR survey at Kalabera Cave as part of a larger GPR training project on the island

(Elliot and Elliot 2008). This survey also focused on the Indigenous contexts.

Caves and their associated artifacts have also been identified as part of cultural resource

management archeological surveys in various areas of Saipan (Eakin et al. 2012; Mohlman

2011). For example, an archeological survey conducted by the consulting firm Southeastern

Archaeological Research, Inc. (SEARCH) was conducted of the Sabanettan i Toru area in the

north of Saipan and several cave sites were recorded (Eakin et al. 2012). Another archeological

survey of the Ginalangan Defensive Complex on Rota, conducted by Moore and HunterAnderson (1988) identified thirteen different property types on the island of Rota, including

bulwarks, caves, concrete slabs, parapets, pillboxes, pits, revetments, rock-faced terraces,

stone steps, stone wall enclosures, stove bases, vehicles, and water tanks. Another archeological

survey conducted by SEARCH was of the Chudang Palii Defensive Complex in Rota. A portion of

the complex had been documented in 1992 by Swift et al. (1992). Among the 133 features

recorded, including those recorded previously, and of relevance to this research were 27

tunnels, nine overhangs and one rock shelter (Mohlman 2011:50).

Environmental geologists Danko Taboroši of the Hokkaido University and John Jensen of the

University of Guam published an article on the use of caves in WWII in the Mariana Islands, and

more specifically on Guam in 2002; however, the article is historical in nature. Another article

published by Boyd Dixon and Richard Schaefer (2014) focusses on the caves and rock shelters of

Guam and Tinian and primarily is concerned with the pre-historic period use of cave.

Wider cave research has focussed on the non-cultural aspects of caves. In 2006 and 2007,

geologists conducted fieldwork on Saipan to update and reinterpret the geology of island, which

was last documented in 1956. This included documenting the geological composition of caves

found in Saipan’s karst topography (Weary and Burton 2011). In 2009, biologists attempted to

establish a prehistoric fossil record for the vertebrate fauna of Guam. To achieve this, they

excavated animal bones in Guam’s caves, particularly Ritidian Cave and Gotham Cave. Results

expanded on the reptilian, rat, and bird fauna of Guam and indicate that human impact had led

to declines or losses of vertebrate populations by late prehistoric times (Carson 2012:347; Pregill

and Steadman 2009:984, 991–994).

29

�Oral histories

In 1980 a private research and writing firm, Ted Oxborrow and Associates, conducted an oral

history project for the Micronesian Area Research Centre (MARC). They collected 20 interviews

from residents, primarily Chamorro and Carolinian, in Saipan, Tinian, and Rota who lived on the

islands from 1943–1945. The interviews are split into two volumes. The volumes are in the

archival collections at MARC at the University of Guam. Out of the 20 interviewees, 14 mention

Indigenous people digging caves, seeking caves as places of refuge and as places where family

members and co-habitants died during the Battle (MARC 1981:16, 22, 24, 34, 39, 43, 64, 69, 76,

82–83; MARC 1981a:9, 11–12, 19, 57–58, 65–66, 77–79).

In 2004, a book entitled We Drank Our Tears: Remembering the Battle of Saipan was published

(Pacific STAR Center for Young Writers 2004). It is a collection of stories by mostly Chamorro and

Carolinian elders of Saipan which were told to the younger generation (i.e. grandchildren and

great grandchildren) about their experiences during the Battle. There are 79 short stories and

the majority of the interviewees describe hiding in caves (see Appendix D for table of caves

mentioned).

Phelan and Denfeld’s cave research in the Pacific

The most comprehensive publication on cave types dating to the war period was that produced

by W.C. Phelan, USNR, entitled Japanese Military Caves on Peleliu, “Know Your Enemy!” (1945).

The publication was prepared for those currently serving in the Pacific. Phelan (1945) indicates

that in Peleliu, human-made caves were created in different shapes and for different naval and

army purposes. He states that the majority of the human-made caves were for naval purposes

and were more spacious, while the human-made Army caves were smaller and more crudely

constructed (Phelan 1945:16). Phelan identifies different human-made cave types based on

their shape (H, E, U, Y, I, L, and T) (Figure 7, Figure 8, and Figure 9). Most of these caves were

used for shelter while the U and Y-shaped caves were used for combat, and the rectangular

were used for storage. E and T caves were used as shelter and for combat. Those used for

combat were modified with stacked rock, gasoline drums and tree logs for protection (Phelan

1945:4-16). Human-made Army caves came in seven types: I, L, T, U, W, J, and Y. Most were