J Gastrointest Surg (2007) 11:1673–1679

DOI 10.1007/s11605-007-0341-6

Surgical Management of Gastro–Gastric Fistula

After Divided Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

for Morbid Obesity

O. N. Tucker & S. Szomstein & R. J. Rosenthal

Received: 23 July 2007 / Accepted: 11 September 2007 / Published online: 3 October 2007

# 2007 The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract

Abstract

Background Gastro–gastric fistula (GGF) formation is uncommon after divided laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

(LRYGB) for morbid obesity. Optimal surgical management remains controversial.

Methods A retrospective review was performed of a prospectively maintained database of patients undergoing LRYGB

from January 2001 to October 2006.

Results Of 1,763 primary procedures, 27 patients (1.5%) developed a GGF and 10 (37%) resolved with medical

management, whereas 17 (63%) required surgical intervention. An additional seven patients requiring surgical intervention

for GGF after RYGB were referred from another institution. Indications for surgery included weight regain, recurrent, or

non-healing gastrojejunal anastomotic (GJA) ulceration with persistent abdominal pain and/or hemorrhage, and/or recurrent

GJA stricture. Remnant gastrectomy with GGF excision or exclusion was performed in 23 patients (96%) with an average

in-hospital stay of 7.5 days (range, 3–27). Morbidity in six patients (25%) was caused by pneumonia, n=2; wound

infection, n=2; staple-line bleed, n=1; and subcapsular splenic hematoma, n=1. There were no mortalities. Complete

resolution of symptoms and associated ulceration was seen in the majority of patients.

Conclusion Although uncommon, GGF formation can complicate divided LRYGB. Laparoscopic remnant gastrectomy

with fistula excision or exclusion can be used to effectively manage symptomatic patients who fail to respond to

conservative measures.

Keywords Complications . Roux-en-Y gastric bypass .

Morbid obesity . Fistula . Remnant gastrectomy

Abbreviations

AA

antecolic antegastric

BMI

body mass index

CT

computed tomography

GE

gastroesophageal

GUGI

GGF

EGD

LRG

LRYGB

POD

PPI

RG

RR

RYGB

gastrograffin upper gastrointestinal study

gastro–gastric fistula

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

laparoscopic remnant gastrectomy

laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

postoperative day

proton pump inhibitor

remnant gastrectomy

retrocolic retrogastric

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

This paper was presented at the SSAT Poster Presentation session on

May 21st 2007 at the SSAT Annual Meeting at Digestive Disease

Week, Washington (poster ID M1590).

O. N. Tucker : S. Szomstein : R. J. Rosenthal (*)

The Bariatric Institute and Division of Minimally Invasive

Surgery, Cleveland Clinic Florida,

2950 Cleveland Clinic Blvd.,

Weston, FL 33331, USA

e-mail: rosentr@ccf.org

Introduction

Surgery is the preferred technique to achieve weight loss

and resolution of comorbidity in the morbidly obese.1

However, surgery is not without its complications, and a

�1674

wide variety of approaches have been developed over the

last three decades in an attempt to reduce morbidity and

improve outcome. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

(LRYGB) is currently the most commonly performed

bariatric procedure worldwide.2–6 Despite advances in

technology and improvements in surgical technique, adverse events contributing to serious morbidity and mortality

are seen after LRYGB. Fistula formation is an uncommon

but potentially significant complication. The most common

type encountered is a gastro–gastric fistula (GGF) with an

abnormal communication between the gastric pouch and

the excluded stomach, which can result in failure of weight

loss, weight regain, intractable marginal ulceration with

recurrent upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, pain, and

stricture formation.

Historically, the technique of gastroplasty, its subsequent

modification to the vertical banded gastroplasty, and the

early open RYGB procedures involved the creation of a

non-divided or partially divided gastric pouch.7–9 GGF

rates of 49% were reported after primary RYGB when the

pouch and stomach were stapled in continuity or partially

divided.10 Following complete transection of the gastric

segments, Capella and Capella10 reported a significant

reduction in the incidence of GGF to 2.6%, with further

reduction with the use of jejunal limb interposition.11 These

surgical techniques minimize the incidence of GGF

formation but do not eliminate it. GGF continue to occur

with a reported incidence of up to 6%.10,12,13 We have

previously reported a 1.2% incidence of GGF in our series

of patients after divided LRYGB.14

The optimal management of GGF remains controversial,

and reports of surgical treatment of this complication are

infrequent.10,12,15 We wished to determine the incidence of

GGF in our patient population of 1,763 morbidly obese

patients who underwent primary divided LRYGB to

determine the indications for intervention and to evaluate

a novel surgical approach to symptomatic GGF. We present

our results on laparoscopic remnant gastrectomy (LRG) with

tract excision or exclusion without interference with the

gastrojejunostomy in the management of patients with

symptomatic GGF after LRYGB.

Methods

Review of a prospectively maintained database and medical

records of consecutive patients undergoing primary

LRYGB from January 2001 to October 2006 was undertaken. All procedures were performed by two surgeons (S.

S. and R.J.R.) in accordance with the National Institute of

Health consensus criteria.16 Study permission was obtained

from the Institutional Review Board. All patients had a

Gastrograffin upper gastrointestinal study (GUGI) on

J Gastrointest Surg (2007) 11:1673–1679

postoperative day (POD) 1, and oral intake commenced if

normal. Patients were discharged on POD 2 to 4 on a

3-month course of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). Patients

were reviewed at 2 weeks, 2 and 6 months, and yearly

thereafter. All data including demographic data, weight,

body mass index (BMI), co-morbidities, prior surgery,

reason for revision, complications, and outcome, including

mortality, morbidity, readmission rate, and weight loss,

were analyzed.

Surgical Technique of Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric

Bypass

A standard seven-trocar LRYGB was performed.17 A 15- to

20-ml pouch was created with a linear stapler with

reinforcement of the last three vertical firings with bovine

pericardial strips. A 50-cm biliopancreatic and >100-cm

antecolic antegastric (AA) alimentary limb determined by

BMI were fashioned. GJA and pouch staple-line integrity

was confirmed by air insufflation, methylene blue instillation, and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

Diagnosis and Management of Patients with GGF

Patients with persistent nausea, vomiting, failure of weight

loss, weight regain, intractable GJA ulceration, persistent

epigastric pain, recurrent upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage,

and GJA stricture underwent surgeon-performed EGD,

GUGI, barium contrast study with supine and lateral

decubitus views, and/or double contrast abdominal CT

(Fig. 1). All patients with a GGF were treated with a PPI

regardless of symptoms, with the addition of sucralfate for

concomitant marginal ulceration and/or stricture. Indications for surgery were failed medical management in a

symptomatic patient, weight regain with non-resolution of

comorbidity, recurrent or non-healing GJA ulceration with

persistent abdominal pain and/or hemorrhage, and recurrent

GJA stricture.

Surgical Technique of Laparoscopic Remnant Gastrectomy

Trocar site placement was identical to primary LRYGB.17

The greater curve vessels were divided to the GEJ, the

postgastric space entered with remnant mobilization, and a

window was created separating pouch and remnant. Intraoperative EGD was performed to delineate the fistula. The

distal antrum was transected with a linear stapler proximal

to the pylorus. The pouch was vertically transected medial

to the GGF over an Ewald tube with a linear stapler. In the

presence of a small pouch, the remnant was vertically

transected lateral to the GGF, leaving a narrow stomach

margin. All staple lines were over-sewn. Repeat EGD was

performed to confirm fistula excision or exclusion, fol-

�J Gastrointest Surg (2007) 11:1673–1679

1675

tectomy, appendicectomy and two previous caesarian

sections; the second, had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy

and bilateral tubal ligation; and the third, had a total

abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingoophorectomy. Concomitant surgery was performed at the time of

LRYGB in two patients, umbilical hernia repair in one, and

laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the other. All procedures

were completed laparoscopically (100%). The mean length

of hospital stay was 3.7 days (range, 3–5). During followup, three patients (18%) developed acute cholecystitis

requiring laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

The indications for surgery were failure of medical

management in 17 (100%), weight regain in 9 (53%),

persistent epigastric pain in 10 (59%), vomiting in 5 (29%),

persistent GJA ulceration in 13 (76%) with significant

hemorrhage in 3 (18%), and non-resolving GJA stenosis in

8 (47%) patients (some patients had more than one

indication). Surgery was performed at a mean of

24.9 months after primary LRYGB (range, 4–57). LRG

was performed in all 17 patients and completed laparoscopically in 16 (94%). One patient required conversion

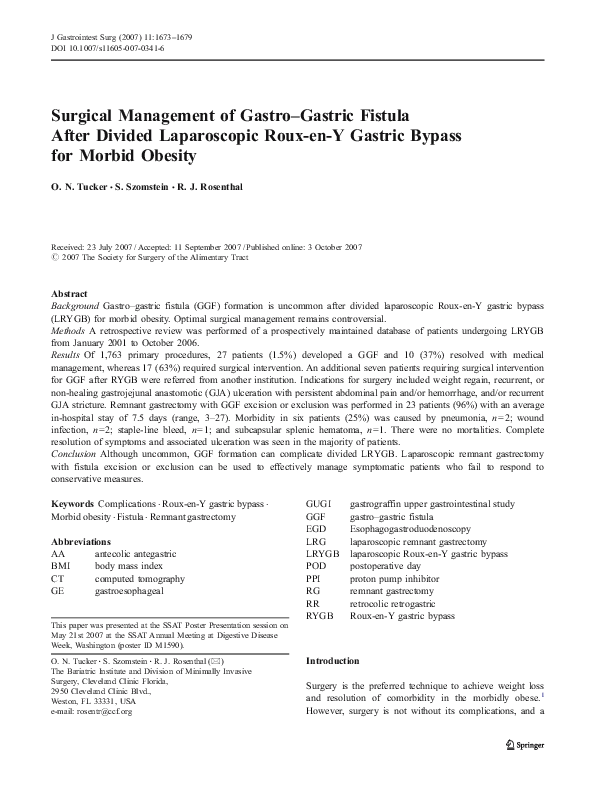

(6%) because of excess intraluminal air in the gastrointesFigure 1 Gastrograffin upper gastrointestinal contrast study demonstrating contrast extravasation from the lateral aspect of the gastric

pouch (P) through a fistulous tract (arrows) into the remnant stomach

(R) after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; E esophagus.

lowed by air insufflation to check staple-line integrity. The

gastric remnant was extracted through the umbilicus.

Results

Over a 70-month period from January 2001 to October

2006, 1,763 patients underwent LRYGB for morbid

obesity. Of the 1,763 procedures performed, 27 patients

(1.5%) developed a GGF. All LRYGB procedures in these

27 patients were performed in a standard fashion with an

AA approach, and all were completed laparoscopically. All

27 patients were prescribed a treatment course of a PPI. In

addition, sucralfate was commenced in patients with

concomitant GJA ulceration and/or stenosis. Ten patients

(37%) with GGF after LRYGB responded to medical

treatment with symptom resolution. The remaining 17

patients (63%) had persistent symptoms despite maximum

medical treatment and required surgical intervention.

Of the 17 patients who required surgical intervention, the

majority were women with a male/female ratio of 1:5. At

the time of their primary LRYGB, their mean age was

42 years (range, 30–58), with a mean weight of 325 lb

(range 215–570), and a mean BMI of 49.7 kg/m2 (range,

35–61; Table 1). Three patients had a history of previous

abdominal surgery. One patient had a prior open cholecys-

Table 1 Patient Characteristics at Primary Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y

Gastric Bypass

Patients with gastro–gastric fistula requiring

surgery (n)

Gender (n)

Male

Female

Age (year)

Mean

Range

Weight (lb)

Mean

Range

BMI (kg/m2)

Mean

Range

Comorbidities (n)

Hypertension

Ischemic heart disease

Hyperlipidemia

Diabetes

Osteoarthritis

Chronic muscle and joint pain

Obstructive sleep apnoea

Gastroesophageal reflux

Deep venous thrombosis

Pulmonary embolus

Depression

Hypothyroidism

Others

Data in parentheses are percentages.

BMI Body mass index

17/27 (63%)

14 (82)

3 (18)

42

30–58

325

215–570

49.7

35–61

13 (76)

2 (12)

8 (47)

7 (41)

9 (53)

7 (41)

11 (65)

7 (41)

2 (12)

2 (12)

4 (23)

1 (6)

4 (23)

�1676

tinal tract after an intraoperative EGD. Remnant gastrectomy with pouch trimming and GGF excision was performed

in 12 patients (71%); four (23.5%) of these patients

required GJA excision and reanastomosis for stomal

obliteration secondary to longstanding marginal ulceration.

LRG without pouch trimming was performed in 5 patients

(29%) for exclusion of GGF. Five of 17 (29.4%) patients

developed early postoperative complications that delayed

discharge. One patient required 3 days of intravenous

antibiotics for a wound infection. A second patient

developed unexplained pyrexia, nausea, and tachycardia.

A GUGI and abdominal CT scan were normal with no

evidence of a leak or collection, and the patient responded

to conservative treatment. The third patient discharged

purulent fluid from his surgical drain on POD 7. An

anastomotic or staple-line leak was suspected, but a GUGI

and abdominal CT were entirely normal. He was discharged home on oral antibiotics with the drain in situ,

remained well, and the drain was subsequently removed in

the outpatient clinic. Hemorrhage from the gastric staple

line occurred in a single patient who was taking an oral

anticoagulant before surgery. This patient underwent an

urgent exploratory laparoscopy that required conversion to

an open approach to achieve hemostasis with over-sewing

of the pouch staple line. A fifth patient developed

pneumonia, which responded to oral antibiotics. The mean

length of stay for the 17 patients was 6.1 days (range,

3–10).

An additional seven patients were referred for surgery

from other centers with symptomatic GGF after open

RYGB in five (71%), and LRYGB in two (29%). Four

patients had a RYGB with GJA ring reinforcement (57%)

and two a non-divided RYGB with staple-line disruption

(28.5%). All patients were female. Incomplete data was

available for weight, BMI, and comorbidity at the time of

primary RYGB, and this data, was not included. The

patients presented for surgery at a mean of 7.8 years (range,

2–20) from the time of primary RYGB at a mean age of

42 years (range, 27–52). Indications for surgery were

intractable epigastric pain in four (57%), non-resolving

GJA stenosis in one (14%), recurrent GJA ulceration in

three (43%) with hemorrhage in one (14%), coexistent

jejuno–gastric fistula in one (14%), and vomiting in four

(57%). Six of the seven patients underwent RG (86%). The

remaining patient had a prior ring reinforcement of an open

retrocolic retrogastric (RR) RYGB. At laparotomy, pouch

outlet obstruction with ring erosion and GGF was evident.

The eroded ring was removed, the GJA was excised and

reanastomosed, the GGF transected, and a tube gastrostomy

inserted. LRG was attempted in four patients and completed

successfully in two (50%). An open approach was used in

the remaining two patients. Remnant gastrectomy with

pouch trimming and GGF excision was performed in five

J Gastrointest Surg (2007) 11:1673–1679

patients (71%). In four (57%) patients, the gastric bypass

was converted from a RR to an AA RYGB with excision

and reanastomosis of the GJA, and insertion of a tube

gastrostomy in addition to pouch trimming and GGF

excision. Remnant gastrectomy with GGF exclusion was

performed in one patient. In addition, an appendicectomy

was performed in one patient. Three complications were

observed, a subcapsular splenic hematoma, pneumonia, and

a superficial wound infection. The mean duration of

hospital stay was 9.4 days (range, 3–27).

Our incomplete follow-up is promising with symptom

resolution in the majority of patients (87%), resolution of

GGF and GJA ulceration in all 24 patients, and further

weight loss of an average of 27 lb in 21 patients (87%).

Four patients required surgical intervention for late

complications after LRG, including open adhesiolysis for

small bowel obstruction at 1 month, laparoscopic adhesiolysis for small bowel obstruction at 4 months, incarcerated

umbilical port site hernia repair at 13 months, and a

converted procedure for an internal hernia at the jejunojejunal anastomosis at 21 months.

Discussion

There are many factors responsible for GGF formation after

LRYGB (Table 2). Non-divided RYGB procedures have

been associated with an unacceptably high incidence of

GGF because of breakdown of the staple line with

reestablishment of continuity between the gastric segTable 2 Pathogenesis of Gastro–Gastric Fistula After Laparoscopic

Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

Description

Iatrogenic

Anastomotic Leak

Operation type

Marginal ulcer,

perforation

Foreign body erosion

Natural tendency

Poor surgical technique

Incomplete gastric transection

Pouch staple line disruption

Gastrojejunal anastomotic disruption

Coagulation injury

Ischemic necrosis due to foreign body:

VBG, LAGB

Incomplete gastric transection

Non-divided gastric bypass

Tissue ischemia

Staple migration

Use of non-absorbable suture material

Preanastomotic rings in banded gastric

bypass

Bovine pericardial strips

Natural gastric migration to reattach to the

remnant

LAGB Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, VBG vertical banded

gastroplasty

�J Gastrointest Surg (2007) 11:1673–1679

ments.10 In our series, two patients referred to us for

surgical management of symptomatic GGF from other

centers had a prior non-divided RYGB with staple-line

disruption (28.5%). Subsequent technical variations with

reinforcement of divided RYGB procedures with bands or

rings to increase restriction and prevent stomal and pouch

dilation were also plagued with a high incidence of

GGF.7,10 Intragastric migration of the band or ring with

erosion of the staple line was implicated in the evolution of

GGF in these procedures.7,10 Four of the patients referred to

us from other centers with symptomatic GGF had a prior

RYGB with GJA ring reinforcement (57%). At laparotomy,

two of the four rings had completely eroded through the

gastric staple line, whereas the other two were densely

adhered to the gastric wall. Ischemic necrosis because of

the presence of a constricting ring or band may have been

responsible for GGF in the latter two cases.

In the current era of divided RYGB, the majority of GGF

are caused by poor surgical technique with failure to

completely divide the stomach during pouch creation with

maintenance of continuity between the pouch and remnant.

Cucchi et al.13 reported a 6% incidence in divided gastric

bypass and recommended meticulous oversewing of staple

lines, careful anastomotic technique with good bites of

healthy tissue, avoidance of alimentary limb obstruction,

and intraoperative confirmation of GJA integrity using

methylene blue. Another common cause of GGF is an acute

leak from the GJA or the pouch staple-line disruption,

which is reported in up to 4.3% of patients after LRYGB.18

We have previously reported a 1.7% incidence of GJA leak,

of whom 27% subsequently developed a GGF.14 Malfunctioning of linear staplers can also occur, although this

complication has become uncommon with the advent of

more sophisticated devices.19 Various techniques have been

used to reduce the occurrence of pouch staple-line leak and

GGF, including jejunal and/or omental interposition, suture

reinforcement of the staple line, vapor-heated fibrin sealant,

and more recently, bovine pericardial strips.20–23

Figure 2 Schematic representation of a gastro–gastric fistula after

laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; GJA gastrojejunal anastomosis, GGF gastro–gastric fistula, HCL hydrochloric acid, P cells parietal

cells, G cells gastrin cells.

1677

Table 3 Surgical Management of Gastro–Gastric Fistula

n=24 patients

Remnant gastrectomy,

n=23 (96)

Additional procedures

Fistula transection,

n=1 (4)

Remnant gastrectomy with GGF excision,

n=9

Remnant gastrectomy with GGF exclusion,

n=6

Remnant gastrectomy with redo GJA,

n=8

Gastrostomy, n=4

Appendicectomy, n=1

Conversion from RR RYGB to AA RYGB,

n=4

Removal of eroded ring, GGF transection,

redo GJA, tube gastrostomy, n=1

Data in parentheses are percentages.

GGF Gastro–gastric fistula, RR retrocolic retrogastric, AA antecolic

antegastric, RYBG Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

In our series, the incidence of symptomatic GGF of 1.5%

after 1,763 primary LRYGB is relatively low compared to

other published series.13,15,24 Of these 27 patients, 37%

resolved without further intervention. We believe this is

because of standardization of our surgical approach to

LRYGB. At the beginning of the procedure, dissection

commences high on the gastric fundus to expose the angle

of His and the gastroesophageal junction. This exposure

allows the creation of a small lesser curve-based pouch and

ensures exclusion of the fundus with complete separation of

the gastric segments under direct vision. Incomplete

division of the apical portion of the stomach during pouch

construction can predispose to GGF formation.25 We

routinely perform a posterior wall stapled GJA and close

the anterior enterotomy in two layers with an absorbable

suture creating a narrow 1.5-cm outlet. To reduce the risk of

staple-line leak and hemorrhage, the lateral pouch staple

line is reinforced with bovine pericardial strips. The

integrity of the GJA and pouch staple line are then

confirmed by a combination of intraoperative EGD, air

insufflation, and methylene blue instillation. Non-absorbable suture use, staple migration, and tissue ischemia have

all been implicated in the development of stomal ulceration.10,14,24 Although peristrips could act as a foreign body

resulting in localized erosion and/or ulceration with

subsequent GGF formation, no cases have been recorded

in our series. We also use diathermy judiciously, as a

localized coagulation injury may predispose to GGF

formation. In our institution, we routinely perform GUGI

study on POD 1, facilitating the detection of acute leaks

and permitting early intervention.26

Persistent ulceration at the GJA predisposes to a

localized perforation and subsequent GGF formation. We

have previously reported a 4.2% incidence of marginal

ulceration after LRYGB, with a significant increase up to

�1678

53.3% in patients with a demonstrable GGF.14 To reduce

the risk of GJA ulceration, we preoperatively test and treat

patients positive for Helicobacter pylori. Eradication of H.

pylori has been demonstrated to significantly reduce the

incidence of marginal ulceration.27,28 Patients are also

encouraged to stop smoking. In addition, after LRYGB,

patients are discharged on a 3-month course of a PPI.29

A number of patients with symptomatic GGF will

respond to conservative management.30 The aim of medical

treatment is to attenuate the increased acid production in the

remnant stomach because of stimulation of parietal and

antral G-cells by food entering through the fistula (Fig. 2).

The acid from the remnant stomach spills over through the

fistula into the pouch and contributes to marginal ulceration

formation.31 Acid production, although significantly reduced, has been observed in the gastric pouch by

stimulation of residual parietal cells.32,33 PPI significantly

decrease acid production in the excluded gastric remnant. In

our unit, patients are commenced on a 6-week treatment

course of a PPI, with the addition of sucralfate in the

presence of marginal ulceration. Sucralfate provides a

protective barrier to the gastric pouch and jejunal mucosa,

reducing damage by refluxed acid from the remnant

stomach through the GGF.14,30 Patients are reevaluated

after 6 weeks to assess symptoms, and a repeat EGD is

performed. If patients fail to respond to maximal medical

therapy and develop GGF-related complications, surgery is

indicated. Currently, there is no accepted surgical technique

to manage symptomatic GGF. In our unit, we favor a LRG

with trimming of the gastric pouch and excision or

exclusion of the fistulous tract. This approach does not

interfere with the gastrojejunal anastomosis. In our series,

23 of 24 patients (96%) underwent a RG with GGF

excision in 74% and GGF exclusion in 26% (Table 3).

The pouch size determines the need for fistula excision or

exclusion. In the presence of an adequately sized small

pouch, we exclude the tract by vertical transection of the

gastric remnant just lateral to the fistula. To date, there has

been no evidence of ischemia of the narrow cuff of the

stomach left in situ lateral to the GGF. It is important to

excise as much of the antrum as possible to avoid the

creation of a retained antrum and the theoretical risk of

hypergastrinemia. Therefore, the distal stomach is transected just proximal to the pylorus. Remnant gastrectomy

can be performed successfully by a laparoscopic approach in

the majority of patients. In our series, a laparoscopic

approach was attempted in 21 patients (91%) and completed

in 18 (78%). As expected, the conversion rate for remnant

gastrectomy was higher in patients referred from other

centers, the majority of whom had a primary open RYGB.

Excision of the GJA with reanastomosis is required in the

presence of significant marginal ulceration with stomal

stenosis or prior RYGB, where complete pouch revision is

J Gastrointest Surg (2007) 11:1673–1679

required. Eight patients (35%) in our series required excision

of the GJA with reanastomosis, of whom four (50%) were

converted from a RR to AA RYGB. After RG, adverse

events were observed in the early postoperative period in six

patients (25%), and our surgical reintervention rate was

4.1%. A leak was suspected in one patient but not proven,

and a second patient developed pyrexia of unknown origin.

No deaths were recorded in this series.

Conclusion

In summary, GGF formation can complicate divided LRYGB.

Asymptomatic GGF can be managed conservatively. There is

no standardized surgical treatment approach for symptomatic

GGF. Reports of surgical treatment for this complication are

rare. In this study, we present a novel surgical procedure to

treat GGF, which consists of a laparoscopic approach with

RG with or without trimming of the gastric pouch and/or

fistulous tract, while leaving the GJA intact in the majority of

patients. Based on our early experience, we recommend LRG

with fistula excision or exclusion as an effective option with a

low morbidity and no mortality in the management of

symptomatic GGF after LRYGB.

References

1. Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, Maglione M, Sugerman

HJ, Livingston EH, Nguyen NT, Li Z, Mojica WA, Hilton L, Rhodes

S, Morton SC, Shekelle PG. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of

obesity. Ann Intern Med 2005;142(7):547–559.

2. DeMaria EJ, Jamal MK. Surgical options for obesity. Gastroenterol

Clin North Am 2005;34(1):127–142.

3. Rosenthal RJ, Szomstein S, Kennedy CI, Soto FC, Zundel N.

Laparoscopic surgery for morbid obesity: 1,001 consecutive

Bariatric operations performed at The Bariatric Institute,

Cleveland Clinic Florida. Obes Surg 2006;16(2):119–124.

4. Cottam DR, Nguyen NT, Eid GM, Schauer PR. The impact of

laparoscopy on Bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc 2005;19(5):621–627.

5. Nguyen NT, Silver M, Robinson M, Needleman B, Hartley G,

Cooney R, Catalano R, Dostal J, Sama D, Blankenship J, Burg K,

Stemmer E, Wilson SE. Result of a national audit of Bariatric

surgery performed at academic centers: a 2004 University

HealthSystem Consortium Benchmarking Project. Arch Surg

2006;141(5):445–449.

6. Wittgrove AC, Clark GW. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y500 patients: technique and results, with 3–60 month follow-up.

Obes Surg 2000;10(3):233–239.

7. Gomez CA. Gastroplasty in morbid obesity. Surg Clin North Am

1979;59(6):1113–1120.

8. Mason EE. Vertical banded gastroplasty for obesity. Arch Surg

1982;117(5):701–706.

9. Mason EE, Doherty C, Cullen JJ, Scott D, Rodriguez EM, Maher JW.

Vertical gastroplasty: evolution of vertical banded gastroplasty.

World J Surg 1998;22(9):919–924.

10. Capella JF, Capella RF. Gastro–gastric fistulas and marginal ulcers

in gastric bypass procedures for weight reduction. Obes Surg

1999;9(1):22–27.

�J Gastrointest Surg (2007) 11:1673–1679

11. Fobi MA, Lee H, Igwe D, Jr, Stanczyk M, Tambi JN. Prospective

comparative evaluation of stapled versus transected silastic ring

gastric bypass: 6-year follow-up. Obes Surg 2001;11(1):18–24.

12. Stanczyk M, Deveney CW, Traxler SA, McConnell DB, Jobe BA,

O’Rourke RW. Gastro–gastric fistula in the era of divided

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: strategies for prevention, diagnosis,

and management. Obes Surg 2006;16(3):359–364.

13. Cucchi SG, Pories WJ, MacDonald KG, Morgan EJ. Gastrogastric

fistulas. A complication of divided gastric bypass surgery. Ann

Surg 1995;221(4):387–391.

14. Carrodeguas L, Szomstein S, Soto F, Whipple O, Simpfendorfer

C, Gonzalvo JP, Villares A, Zundel N, Rosenthal R. Management

of gastrogastric fistulas after divided Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

surgery for morbid obesity: analysis of 1,292 consecutive patients

and review of literature. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2005;1(5):467–474.

15. Gumbs AA, Duffy AJ, Bell RL. Management of gastrogastric

fistula after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes

Relat Dis 2006;2(2):117–121.

16. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Consens Statement

1991;9(1):1–20.

17. Szomstein S. How we do it: laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric

bypass. Contemp Surg 2007;62(3):106–111.

18. Hamilton EC, Sims TL, Hamilton TT, Mullican MA, Jones DB,

Provost DA. Clinical predictors of leak after laparoscopic

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Surg Endosc

2003;17(5):679–684.

19. Favretti F, Segato G, De MF, Pucciarelli S, Nitti D, Lise M.

Malfunctioning of linear staplers as a cause of gastro–gastric

fistula in vertical gastroplasty]. G Chir 1990;11(3):157–158.

20. Shikora SA, Kim JJ, Tarnoff ME. Reinforcing gastric staple-lines

with bovine pericardial strips may decrease the likelihood of

gastric leak after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes

Surg 2003;13(1):37–44.

21. Sapala JA, Wood MH, Schuhknecht MP. Anastomotic leak

prophylaxis using a vapor-heated fibrin sealant: report on 738

gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg 2004;14(1):35–42.

1679

22. Lee MG, Provost DA, Jones DB. Use of fibrin sealant in

laparoscopic gastric bypass for the morbidly obese. Obes Surg

2004;14(10):1321–1326.

23. Zorrilla PG, Salinas RJ, Salinas-Martinez AM. Vertical banded

gastroplasty–gastric bypass with and without the interposition of

jejunum: preliminary report. Obes Surg 1999;9(1):29–32.

24. Filho AJ, Kondo W, Nassif LS, Garcia MJ, Tirapelle RA, Dotti

CM. Gastrogastric fistula: a possible complication of Roux-en-Y

gastric bypass. JSLS 2006;10(3):326–331.

25. Gould JC, Garren MJ, Starling JR. Lessons learned from the first

100 cases in a new minimally invasive Bariatric surgery program.

Obes Surg 2004;14(5):618–625.

26. Sims TL, Mullican MA, Hamilton EC, Provost DA, Jones DB.

Routine upper gastrointestinal Gastrografin swallow after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2003;13(1):66–72.

27. Rasmussen JJ, Fuller W, Ali MR. Marginal ulceration after

laparoscopic gastric bypass: an analysis of predisposing factors

in 260 patients. Surg Endosc 2007 19.

28. Carrodeguas L, Szomstein S, Zundel N, Lo ME, Rosenthal R.

Gastrojejunal anastomotic strictures following laparoscopic

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: analysis of 1291 patients.

Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006;2(2):92–97.

29. Gumbs AA, Duffy AJ, Bell RL. Incidence and management of

marginal ulceration after laparoscopic Roux-Y gastric bypass.

Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006;2(4):460–463.

30. Gustavsson S, Sundbom M. Excellent weight result after

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in spite of gastro–gastric fistula. Obes

Surg 2003;13(3):457–459.

31. MacLean LD, Rhode BM, Nohr C, Katz S, McLean AP. Stomal

ulcer after gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg 1997;185(1):1–7.

32. Siilin H, Wanders A, Gustavsson S, Sundbom M. The proximal

gastric pouch invariably contains acid-producing parietal cells in

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2005;15(6):771–777.

33. Hedberg J, Hedenstrom H, Nilsson S, Sundbom M, Gustavsson S.

Role of gastric acid in stomal ulcer after gastric bypass. Obes Surg

2005;15(10):1375–1378.

�

Olga Tucker

Olga Tucker