Ficino on Force, Magic, and Prayers: Neoplatonic

and Hermetic Influences in Ficino’s

Three Books on Life

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD, University of Notre Dame

This article analyzes new evidence from the marginalia to Ficino’s Plotinus manuscripts and offers

a novel reading of Ficino’s “De Vita” 3. It settles scholarly disagreements concerning Paul O. Kristeller’s

manuscript research and Frances Yates’s Hermetic thesis about “De Vita” 3, and reconsiders accepted

conclusions regarding the centrality of Hermetic magic in Ficino’s philosophy. It demonstrates the

origins and sources for “De Vita” 3 in Ficino’s reading of Plotinus’s explanations of prayer, and also

reveals Iamblichus’s overlooked influence on Ficino: on the performative nature of philosophy in “De

Vita” 3, and even on Ficino’s acknowledgment of the pseudonymity of the Hermetica.

INTRODUCTION: PLOTINUS’S INTERPRETER OR

HERMETIC MAGUS?

A HANDBOOK FOR helping scholars and philosophers stay healthy, live long

lives, and bask in the heavens’ glow, Marsilio Ficino’s (1433–99) De Vita Libri Tres

(Three books on life, or simply De Vita) is also the cornerstone of Renaissance theories

of melancholy, saturnine genius, astrology, and magic. Despite its difficulty the De

Vita was a Renaissance best seller: between 1489 and 1647 it was printed in over

thirty editions and multiple vernacular translations.1 The De Vita has also attracted

the attention of some of the brightest luminaries of twentieth-century Renaissance

scholarship. Its third and final book, the De Vita Coelitus Comparanda (On obtaining

life from the heavens),2 has become with some controversy the source text for

understanding two central currents of the Renaissance: Neoplatonism and Hermeticism.

Ficino tells his readers on a few occasions that the third book was originally

written as a commentary on Plotinus’s Enneads, and Paul O. Kristeller first argued

I wish to thank Christian F€orstel at the BnF and David Gura at the University of Notre Dame for

discussing MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816, fols. 157v–158r. I benefited from questions at annual conferences

of the Renaissance Society of America and the International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, and from

the members of Notre Dame’s Classical Tradition Working Group, who read a draft of this article.

1

Kaske’s introduction to Ficino, 2002, 3. All translations are mine except where otherwise noted.

2

Walker, 1958, 3n2, suggests two translations: “on obtaining life from the heavens or on

instituting one’s life celestially.”

Renaissance Quarterly 70 (2017): 44–87 Ó 2017 Renaissance Society of America.

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

45

that since Ficino’s longer commentaries on the individual chapters of the Enneads

end shortly after Ennead 4.3.11, at ca. 4.3.12 (thereafter replaced with short

argumenta), the third book of the De Vita seems to pick up where the commentary

to Ennead 4.3.11 left off.3 Tracking De Vita 3’s origins in Lorenzo de’ Medici’s

(1449–92) deluxe manuscripts of Ficino’s translation and commentary of the

Enneads, Kristeller noted that an earlier draft of the work begins at 4.3.11.4 In fact,

Ficino repeats the title to the commentary of this section, De Vita Coelitus

Comparanda, as the title for De Vita 3, and its removal in subsequent printings of the

Plotinus commentary has thrown off the numbering of the argumenta for the

remaining sections of the Enneads.5

Yet ever since Kristeller formulated this argument the difficulty of identifying the

specific passages in Plotinus on which De Vita 3 comments has caused considerable

scholarly debate, and has persuaded some to conclude that the work does not

comment on Plotinus at all. The present article reviews the scholarly disagreements

centered on Frances Yates’s Hermetic interpretation of Kristeller’s research in order to

analyze new evidence from Ficino’s marginalia to his Greek manuscript of Plotinus’s

Enneads.6 Reconstructing Ficino’s work on Plotinus through these fragmentary

notes, I identify novel sources and establish connections between Plotinus and De

Vita 3. On a few occasions Ficino interrupted his labors on Plotinus to translate

a group of texts by Porphyry, Iamblichus, Proclus, et al., that he published in Venice

(1497) with Aldus Manutius.7 Ficino’s marginalia to Plotinus further reveal ties

between these Neoplatonic works and De Vita 3. Despite the arguments of Yates and

others to the contrary, these findings show that De Vita 3 is, in fact, Neoplatonic in

nature. This study, therefore, reconsiders accepted conclusions regarding the

centrality of Hermetic magic in Ficino’s philosophy and demonstrates the origins

and sources for De Vita 3 in Ficino’s reading of Plotinus’s explanations of prayer.

These findings also reveal the overlooked influence of Iamblichus (an acquaintance

and likely student of Plotinus’s disciple Porphyry) on Ficino. Iamblichus’s

incorporation of Neopythagorean philosophy and mathematics into Neoplatonism

in his De secta pythagorica (On the Pythagorean sect), and his debate with Porphyry on

3

On Ficino’s work with Plotinus, see Kristeller, 1:cxxvi–cxxviii, clvii–clix; Gentile and Gilly,

106–07, 111–12; Toussaint’s introduction to Plotinus, 2008; F€orstel; Robichaud, 2015 and

2017, where I refer to the present article by “Plotinus’s Hermeneus,” and the scholarship cited

therein. At Ennead 4.3.14, Ficino remarks that he is interrupting his longer commentary:

Plotinus, 1580, 371.

4

Beginning at MS Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (hereafter LAUR), Plut. 82.11,

fol.13r.

5

Kristeller, 1:xii, lxxxiv–lxxxvi, cxxxvi–cxxviii.

6

MS Paris, Biblioth�eque nationale de France (hereafter BnF), Gr. 1816.

7

For example, the letter to Faventino from August 1489: see Ficino, 1576, 900. This

volume is known by Ficino’s title: Iamblichus’s De mysteriis. See Iamblichus, 1497.

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�46

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

the place of theurgy (working with/on gods) and religious ritual within philosophy in

his De mysteriis (On mysteries), influenced the performative nature of philosophy and

the understanding of power and symbol in De Vita 3.8 Ficino’s study of Iamblichus’s

De mysteriis even compelled him to acknowledge the Hermetica’s pseudonymity.

The point of contention for the question at hand emerged once Yates, in her

influential Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (1964), built upon Kristeller’s

manuscript evidence by arguing that in De Vita 3 Ficino only proposed a Hermetic

reading of Ennead 4.3.11, where Plotinus speaks of the images or statues of the

divine: “And it seems to me that the ancient sages who made temples and statues

[ἀγάλματα] wishing that the gods would be present for them, examining the nature

of all, understood that the nature of soul is easily accepted everywhere, and it would

be easier most of all if someone were to make something sympathetic to soul capable

of receiving a portion of it.”9 In Yates’s opinion, “Ficino’s commentary on the

Plotinus passage becomes, by devious ways, a justification for the use of talismans,

and of the magic of the Asclepius, on Neoplatonic grounds.”10 She continues, “this

means that the De Vita Coelitus Comparanda is a commentary only secondarily on

Plotinus and primarily on Trismegistus, or rather, on the passage in the Asclepius in

which he described the magical Egyptian worship.”11 For Yates, Plotinus and other

Neoplatonists only serve as pretexts for Ficino’s circuitous (and in her view devious)

commentary on the so-called “god-making” passage describing ancient Egyptian

practices of luring and trapping the divine in statues from the Asclepius, the

pseudepigraphic text of the first centuries CE (also known as the Perfect Discourse),

purportedly authored by Hermes Trismegistus (and once thought to have been

translated from Greek into Latin by Apuleius).

The debate on the genesis of Ficino’s De Vita 3 seems often to have been held in

the halls of the Warburg Institute. Scholars of the De Vita have argued whether the

third book is indebted to one of two sections of Plotinus’s Enneads. The first, on

images and statues of the divine, is the passage just quoted from Ennead 4.3.11. The

second, where Plotinus primarily explains the function of prayer, is from Ennead

4.4.26–45. What is at stake in the long-standing debate is that those who interpret

De Vita 3 as a work of Hermetic magic pin their argument to the claim that its source

text is the first passage from Plotinus on images and statues of the divine, whereas

those who interpret De Vita 3 as a work of Neoplatonic philosophy point to the

second passage from Plotinus on prayer as its source text. Before Yates, and seemingly

8

Iamblichus is also known for dividing reality into multiple suborders (a metaphysics also

advanced by Proclus and Pseudo-Dionysius), for organizing the corpus of Platonic dialogues

into a specific philosophical and pedagogical series, and for writing commentaries on Plato and

Aristotle.

9

Plotinus, 1964–83, 2:26 (Ennead 4.3.11.1–6).

10

Yates, 70.

11

Ibid., 71.

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

47

unaware of Kristeller’s evidence, Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz

Saxl, in their famed Saturn and Melancholy (1964), identified the second section on

prayer as Ficino’s source (along with Plotinus’s critique of astrology).12 D. P. Walker

cited Kristeller’s argument yet also agreed with Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl, whom

he does not quote, that De Vita 3 is more likely a commentary on the second section

on prayer.13 Nevertheless, Walker also discusses the importance of the “god-making”

passage from the Asclepius and connects it to the first section from Plotinus on divine

images and statues.14 Eugenio Garin also recognizes Kristeller’s arguments as

important and accepts them (without explicit acknowledgment) in his own

significant study, “Le ‘elezioni’ e il problema dell’astrologia” (1960), on Ficino,

Plotinus, and elective astrology.15 According to Garin, in the first section, on divine

images and statues, Ficino found the central node for De Vita 3, namely the Plotinian

concept of a mediating soul that fabricates things according to the rational forms that it

contains; but Garin also writes a few lines comparing Ficino’s project to the Hermetic

“god-making” passage of the Asclepius.16

Thus one ought to contextualize Yates’s thesis in relation to these four major

studies.17 All of these scholars, including Yates, draw on a variety of sources to show the

rich complexity of Ficino’s text.18 Nevertheless, Yates’s argument forcefully suppresses

12

Plotinus’s critique of astrology is in Plotinus, 1964–83 (Ennead 2.3). Klibansky, Panofsky,

and Saxl, 263n67. They argue that De Vita 3 seeks to reconcile medicine with Neoplatonism

through the Neoplatonic principle of series, which Ficino chiefly encounters in Proclus’s De

sacrificio et magia. Ibid., 254–74. Περὶ τῆς καθ᾽Ἕλληνας ἱερατικῆς τέχνης was

previously thought to have survived only in Ficino’s Latin translation before Bidez published

the Greek text in 1928: Bidez, Cumont, Delatte, et al., 139–52.

13

Walker, 1958, 3n2, 14n5. Walker understands Ficino’s spiritual magic principally as

Neoplatonic or Orphic, and refers to Plotinus’s discussion of figures as Ficino’s source for his own

thinking about celestial figures and images. Ibid., 14–15n7, where he refers to Ennead 4.4.34.

14

Walker, 1958, 40–44.

15

Garin, 1960, 18–19.

16

The dynamism of Garin’s argument does not rest on one source very long, directing the

reader to multiple references including other passages of the Enneads (notably Ennead 4.4.40), the

works of Albumasar, Iamblichus’s De mysteriis, the Theologia Aristotelis, Psellus’s interpretation of

the Chaldean Oracles, and Proclus’s De sacrificio et magia. In fact, it seems as though for Garin that

Ennead 4.3.11 has its closest affinities not so much with the Asclepius as with Proclus’s De sacrificio

et magia. What is of first importance to him is the common mimetic ontology in Proclus, Ficino,

and the mirror of Dionysus at Ennead 4.3.12: Garin, 1960, 19, 21.

17

For Yates’s use of Kristeller’s evidence, see 66n2 and 68; for Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl,

see ibid., 67n3; for Garin, ibid., 66n1, 68n9, 70n11, 71n14, 219n34. Yates, 68n9, concedes in

a note: “Walker (p. 3. note 2) points out that Enn. IV, 4, 30–42, may also be relevant.” Her

work contains multiple references to Walker.

18

Kaske and Clark’s introduction and notes in Ficino, 2002, are helpful for an orientation of

the sources.

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�48

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

the text’s specifically Plotinian and generally Neoplatonic nature. Ficino primarily

invokes Neoplatonists, she believes, as a cipher to encrypt his true Hermetic magic.

Hardening the position that he had argued earlier in “Le ‘elezioni,’” Garin, in his

magisterial survey of Renaissance astrology, explicitly agreed with Yates (who was in

turn influenced by Garin’s “Le ‘elezioni’”) that the De Vita 3 is an exegesis of the

Asclepius rather than a commentary on Plotinus.19

However, despite its influence, Yates’s interpretation of Kristeller’s evidence has

not convinced everyone.20 Brian Copenhaver has been a vocal critic. He has argued

that De Vita 3 is neither a treatise on Hermetic magic nor a long commentary on the

Asclepius passage about the “god-making” statues, but a rigorous philosophical study

of natural magic that draws primarily from Ficino’s studies of Plotinus, Thomas

Aquinas, and Neoplatonic works. As Copenhaver notes, if the De Vita 3 is in fact

a commentary on the statues from the Asclepius by way of commenting on the

discussion of statues in Plotinus, the reader has to wait until the latter chapters of

De Vita 3 to find any mention of them.21 Yates explains this away by claiming that

Ficino deliberately hides his true intentions, in her words, by “muffling . . . the

connection with the Asclepius under layers of commentary on Plotinus or rather

misleading quotations from Thomas Aquinas.”22 In short, what for Yates are

Ficino’s devious and deceitful misdirections are for Copenhaver Ficino’s actual

sources. The question of Ficino’s sources for De Vita 3 is still a persistent debate.

More recently, St�

ephane Toussaint discussed Ficino’s use of Oriental philosophy

and Lauri Ockenstr€om has argued that Ficino’s writings should be considered

Hermetic magic based on astromagical images in the Arabic Hermetica.23 This

study aims to demonstrate that Ficino’s marginalia to his Plotinus manuscripts

show that Plotinus’s writings on prayer served as a matrix to hold together

a variety of sources (including, importantly, Iamblichus) central to Ficino’s

thinking in De Vita 3.

19

Garin, 1976a, 73.

See also Zanier, esp. 29–60.

21

To be precise, chapters 13, 20, and 26 (the work has 26 chapters in total). Copenhaver,

1984, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1993. Copenhaver thinks De Vita 3 draws on Ennead 4.3–5,

whereas, to repeat, Yates only believes Ficino comments on the statues in Ennead 4.3.11 in

order to discuss the statues in the Asclepius.

22

Yates, 97.

23

Zambelli critiques Copenhaver’s arguments, and there is still a steady stream of works

trying to identify the sources for Ficino’s De Vita 3 (some of which are broached below). Most

recently see Ockenstr€om; Toussaint. On the Arabic Hermetica now, see van Bladel. Debate on

Yates’s interpretation of Kristeller’s evidence has also bled into the dispute concerning Yates’s

larger argument (the so-called Yates thesis that is not addressed in this article) about

Hermeticism in early modern thought (see Zambelli, 314–27; Copenhaver, 1990), and onto

the discussion of the Hermetica in Ficino’s oeuvre: see Allen, 1990; Gentile and Gilly, 19–26;

Moreschini.

20

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

49

THE ORIGINS OF DE VITA 3 IN FICINO’S

PLOTINUS MANUSCRIPTS

In translating the Enneads, Ficino chiefly utilized two manuscripts that are now

housed in Florence and Paris.24 Sebastiano Gentile astutely detected connections

between De Vita 3 and the Parisian manuscript.25 If one looks in the manuscript at the

specific passage in question where Plotinus discusses statues, one finds, Gentile

observes, two pertinent marginal annotations in Greek by Ficino. In the first Ficino

writes, “How the ancient wise men through statues and sacred things made the gods

present in them”; and, in the second, “in what manner and whence comes the power

of the magi and prophets.”26 Gentile concludes: “Thus Frances Yates (1981, p. 82)

was right when she said that the De Vita is not a commentary on Plotinus but on the

passage of Asclepius.”27 Gentile’s brief comments correctly establish the significance of

Ficino’s annotations in the Parisian manuscript, but a full investigation of the evidence

complicates Yates’s thesis.

If one juxtaposes Ficino’s annotations to this passage with the Greek text of

Plotinus one will notice that in the first note Ficino only reformulates Plotinus’s

own Greek terminology to indicate the passage’s subject matter.28 These Greek

annotations merely record the passage’s content, in effect creating notabilia that

serve as marginal catchwords for facilitating future referencing. In these instances

Ficino is not adding much of his own interpretive content, Hermetic or

24

MS Florence, LAUR, Plut. 87.03: a fourteenth-century manuscript from the circle of

Nicephoros Chumnos (ca. 1260–1327), formerly possessed by Niccol�o Niccoli (1364–1437)

and the library of San Marco, and an important witness to one of the two most important

textual families; its apograph, MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816 was copied in 1469 by Giovanni

Scutariotes. For descriptions of the manuscripts, see Henry, 16–36, 45–62.

25

Gentile rightly points out a few significant annotations in two short entries of a manuscript

catalogue. He supplies a few lines from Ficino’s annotations to 4.3.11 and 4.4 but neither

transcribes them in full nor analyzes them in detail: Gentile and Gilly, 106–07, 111–12.

26

MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 137r: “πῶς παλαίοι σοφοὶ διὰ τὰ ἀγάλματα καὶ ἱερὰ

θεοὺς ἐποιησαν ἀυτοῖς παρεῖναι.” MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 137v: “ποῖα καὶ πόθεν

δύναμις μάγων καὶ προφήτων.”

27

Gentile and Gilly, 107; see also his entry in Gentile, Niccoli, and Viti, 136.

28

Plotinus, 1964–83, 2:26 (Ennead 4.3.11.1–6): “Καί μοι δοκοῦσιν οἱ πάλαι σοφοί,

ὅσοι ἐβουλήθησαν θεοὺς αὐτοῖς παρεῖναι ἱερὰ καὶ ἀγάλματα ποιησάμενοι, εἰς τὴν

τοῦ παντὸς φύσιν ἀπιδόντες.” Thus, for example, if one compares it to the first Greek note

on the same folio one sees that Ficino employs the same reading strategy at 4.3.10. MS Paris,

BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 137r: “ψυχὴ καὶ φύσις ποιεῖ οὐ γνώμη ἀλλὰ δυνάμει τῆς οὐσίας”

(“Soul and nature do not make by intent but by the power of substance”). Plotinus, 1964–83,

2:25 (Ennead 4.3.10.13–15): “ὅ τι γὰρ ἂν ἐφάψηται ψυχῆς, οὕτω ποιεῖται ὡς ἔχει φύσεως

ψυχῆς ἡ οὐσία� ἡ δὲ ποιεῖ οὐκ ἐπακτῷ γνώμῃ οὐδὲ βουλὴν ἢ σκέψιν ἀναμείνασα” (“For

anything that touches soul is thus made so that its substance holds the nature of soul. But it makes

neither by an external intent, nor by waiting for deliberation and examination”).

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�50

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

otherwise. This is not to say that these notes are trivial; a single note may point to

an interpretation that is particularly interesting to him. Ficino’s almost

continuous annotation of his manuscript in this manner also demonstrates his

assiduous reading of the Enneads and the textual strategies that he employs to

make the Parisian manuscript a useful tool for repeated study. Almost all of

Ficino’s marginalia to Ennead 4.3 can be classified as notabilia, even if there are

some short Greek notes that are important for determining Ficino’s exegesis.29

However, things are quite different for Plotinus’s explanation of prayer since

Ficino heavily annotates the text. When compared to this second set of notes,

Ficino’s annotations to Plotinus on statues and their supposed Hermetic

undertones behind De Vita 3 are meager indeed.30

The first passage of importance to Ficino is where Plotinus inquires into the

power of prayer, asking whether the heavens have sense and memory to hear our

prayers. He responds that they receive prayers by way of sympathetic magic,

linking our words to them by a certain contact.31 In his manuscript margins,

Ficino writes Greek notabilia in a similar fashion to those discussed above: “where

does the power of the magi come from” and “spherical souls hear prayers and grant

prayers.”32 He follows this with long exegetical Latin notes:

Al-Kindi says in his book on magic that in us there is a certain sense of nature

more universal than the five senses in that universal. It draws out from these

five senses by which all these things come to be known. But beyond these

there are also certain sensibles that are hidden from the other senses. A

fascination is made from their affect and a change occurs by something absent,

remote, and hidden. Some will call this sense of nature the first source and

unity itself of the senses both interior and exterior, or the sense that converges

in the world soul that is present to all things, and by whose contact our senses

Important annotations to Ennead 4.3 in MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816 are on fol. 136r where

Ficino copies a schematic scholion that he found in MS Florence, LAUR, Plut. 87.03 into the

margins near Ennead 4.3.9; on fol. 140r where Ficino draws from Hermias, Damascius, Egidius,

and Basil to understand Ennead 4.3.18–19; and on fol. 142r where Ficino appeals to Synesius and

Psellus to gloss Ennead 4.3.24.

30

Again to clarify: the two compared sections are Plotinus, 1964–83, 2:83–114 (Ennead

4.4.26–45), on prayer and magic, and Plotinus, 1964–83, 2:26–27 (Ennead 4.3.11), on divine

statues and images.

31

Plotinus, 1964–83, 2:83 (Ennead 4.4.26). What follows does not include all of the

annotations to Ennead 4.4. I only focus on the most important notes for reconstructing Ficino’s

exegesis. While some of the notes passed over are of interest to the present study, they would

not alter the present argument significantly. For an overview of Plotinus on prayer, see Rist,

199–212.

32

MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 157v: “δύναμις μάγων πόθεν. ψυχαὶ σφαιρῶν

ἀκοῦoσιν τῶν εὐχων καὶ ἐπινεῦουσιν εὐχαῖς.”

29

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

51

perceive and feel. Or others will assert otherwise. Read Al-Kindi, Proclus’s On

Magic and On Images, and consider how many animals can sense from far

away, as for example a boar can discern the odor and an eagle the color of a dog

through traces and odors left behind that remain hidden to us. Which means

that from things powers are projected and act on us from far away and we act

on others in a wonderful manner, especially because many think that not only

accidental forms that are manifest to the senses multiply species and emit their

powers, but all the more substantial forms hidden to us. Indeed the heavens

chiefly produce their own strong celestial species, from which light, which is

the image of the sun, has such a power.33

Ficino thus interprets Plotinus’s initial discussion on the heavens’ ability to

receive our prayers by glossing it with the ninth-century Arabic philosopher

Al-Kindi’s (Ya‘qūb ibn ’Ishāq al-Kindī) De radiis (On rays) and the fifth_

century Neoplatonist Proclus’s De sacrificio et magia (On sacrifice and

magic).34

Al-Kindi’s modern editors and translators, Marie-Th�er�ese D’Alverny and Françoise

Hudry, have claimed that De radiis’s explanations are more akin to Proclus’s De

sacrificio et magia than any other work.35 In fact, one can see how Ficino made a similar

connection between the two insofar as Al-Kindi’s optical explanation for linear

radiation and Proclus’s concept of ontological series are analogous philosophical

accounts of action at a distance.36 Ficino’s gloss also indicates that he is interested in

33

Ibid.: “Alchindus de magia dicit esse in nobis quemdam naturae sensum communiorem et

5 sensibus in illo communi qui trahit a 5 ad quem perveniunt omnia hec. et ultra hec item

quedam sensibilia aliis sensibus occulta. ex cuius passione fiat fascinatio et alteratio ab aliquo

absente, remoto, occulto. Hunc sensum naturae appellabit aliquis primum fontem et unitatem

ipsam sensuum tam intimorum quam exteriorum vel sensum in anima mundi convenitur

adstantem omnibus, cuius contiguitate sensus nostri percipiant et conpatiantur. Vel alii aliud

afferent. Lege Alchindum et Proculi magicam et de Imaginibus. Considera quam procul multa

animalia sentiant ut aper [fort. apes] odorem et aquila colorem canis discernat per vestigia

odorem relictum nobis occultum. Quod significat a rebus vires longissime proici et agere in nos

et nos in alia mirum in modum praesertim quia plerique putant non solum formas accidentales

quae sunt manifeste sensibus multiplicare species et vires iaculari suas; sed multo magis

substantiales nobis occultas maxime vero celestia producunt species suas valde celestes unde

lumen quod est imago solis tantum vim habet.” Gentile and Gilly, 106.

34

Bidez, Cumont, Delatte, et al., 139–52; Copenhaver, 1988; Al-Kindi; Lindberg, 1976,

18–32; Burnett; Vescovini, 2008, 5–14.

35

Al-Kindi, 158–59.

36

On the Proclean concept of series (τάξεις, σειραί) see Copenhaver, 1988, 85–86. The

terminology that Ficino employs in his translation of Proclus’s De sacrificio et magia also

conveys the transmission of divine power as a series participating mimetically in celestial rays.

Copenhaver, 1988, 107 (lines 35–45); ibid. (lines 63–66).

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�52

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

Al-Kindi’s notion of the unitas regitiva (ruling unity, which itself draws from Proclean

metaphysics), which acts as a principle of unification, assuring a continuity between

the plurality of perception and the cosmos, and connects the individual soul to the

world soul.37 Al-Kindi’s scientific writings in the De radiis and in the De aspectibus

(On aspects) offered one of the first coherent geometric theories for extramission: he

analyzes the cone of radiation emitted from our eyes and the radiation emitted from

the surfaces of other bodies as discrete points transmitting linear rays. The De radiis

employs a geometric analysis of extramission to understand occult action at a distance

and speaks directly to Plotinus on prayer, since by far the largest section in the De

radiis is devoted to explaining the power of words, invocations, and prayers.38

Ficino’s interests in glossing Plotinus on the function of prayer are therefore

equally directed toward scientific epistemology and metaphysical cosmology. He

investigates how various beings (animal, human, and heavenly) can sense manifest

and occult influences (fascinatio, animals smelling and seeing hidden traces at

a distance, and the powers of light). His use of “multiplication of species and

powers” in his explanation of the causal operation of action at a distance also recalls

Roger Bacon’s (ca. 1214–94) scientific theory of optics and perspective that an

object projects linearly its imitative likeness (or species), which in turn projects

another likeness on the same vector, and so on.39 Drawing directly from a passage

in Al-Kindi that influenced medieval optics, Ficino also raises the issue of the

difference between the transmission of manifest and accidental species, on the one

hand, and occult and substantial forms, on the other.40

Regarding Al-Kindi’s influence on Ficino, researchers already have noted

a direct reference to him in De Vita 3, and Copenhaver has discussed Ficino’s

marginalia to the opening paragraph of his Greek manuscript of Proclus’s De

sacrificio et magia, now in the Vallicelliana library: “Porphyry says the same

thing in his Sententiae. See Mercurius, Plotinus, Iamblichus, Al-Kindi, and

your own writings” (fig. 1).41 Yet scholars have also contested the relative

37

For the unitas regitiva, see Al-Kindi, 160–67.

Ibid., 233–50. (De radiis 6).

39

Lindberg, 1976, 113–15; Lindberg, 1983; Lindberg, 1996, lxviii–lxx, 104–06, 140–44.

40

Al-Kindi, 224 (De radiis 3). Lindberg, 1976, 19; Vescovini, 2003, 53–55. The fact that

Ficino refers to species and substantial forms should be noted since some have debated whether

Ficino’s magic is beholden to the notions. See Copenhaver, 1984 and 1986; Blum (pro); and

Zambelli, 321 (contra).

41

The reference to Al-Kindi is at De Vita 3.21. See MS Rome, Biblioteca Vallicelliana

(hereafter VALL), F 20, fol. 138r: “Eadem dixit Porphyrius in propositionibus. Vide

Mercurium et Plotinum et Iamblichum et Alchindum et tua scripta.” Copenhaver, 1988,

88–90; Toussaint published a reference to Al-Kindi in a marginal annotation to Ficino’s

manuscript of Synesius: Toussaint, 22n16; Kaske’s introduction to Ficino, 2002, 28, 46, 50,

51; Weill-Parot, 2002a, 647–708; Weill-Parot, 2002b, 74, 84, 88; Zambelli, 320; Gentile and

Gilly, 95–98.

38

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

53

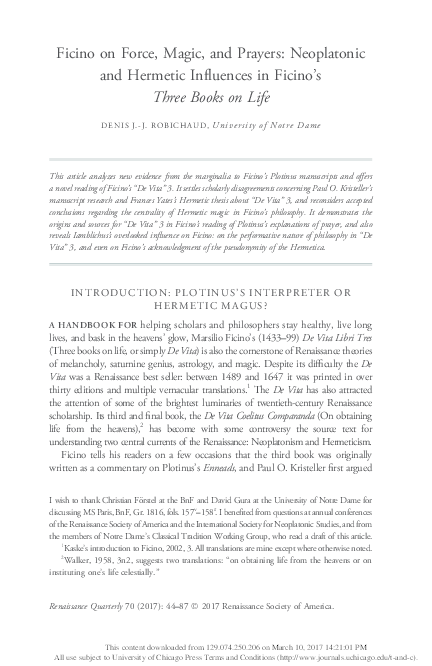

Figure 1. Ficino’s annotations to Proclus, De sacrificio et magia. MS Rome, Biblioteca

Vallicelliana, F 20, fol. 138r.

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�54

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

weight that one ought to attribute to Al-Kindi over Neoplatonists for

Ficino’s theories in De Vita 3.42 When one takes Ficino’s marginalia in the

Parisian manuscript into consideration, it is not solely a question of rating

one source over another, e.g., Al-Kindi instead of Plotinus, since one in fact

notices how Ficino deploys a type of circular hermeneutics. He glosses the

passage above from Plotinus with Al-Kindi’s De radiis and Proclus’s De

sacrificio et magia; in turn, Ficino glosses Proclus’s De sacrificio et magia with

Plotinus and Al-Kindi (along with Porphyry, Hermes, Iamblichus, and

Ficino’s own writings).43

As for the brief mention of the De imaginibus (On images) in the marginal

note, Ficino is likely referring either to a work by the ninth-century Sabian

Thabit (Thebit/Thābit ibn Qurra al-Harrānī) or to another by Pseudo_

Ptolemy, who wrote a work sometimes designated with the same title. It is

difficult to determine whether Ficino alludes only to Thabit or also to PseudoPtolemy since he mentions both authors explicitly in the same breath in De

Vita 3.44 He may very well have been denoting both since they circulated in

the same manuscript corpus. But the matter may be even less certain since

there are a number of medieval tracts on astronomical images that are

preserved with descriptive titles referring to imagines, e.g., De imaginibus et

horis (On images and hours) and De imaginibus sive annulis septem planetarum

(On images or the rings of the seven plants)—the latter of which Ficino

probably knew.45 Ficino may have simply shortened the title of one of these

works, or perhaps even referred to a complete manuscript containing various

works as De imaginibus. Since the note is a personal reference, he would have

known its designation without the need of further precision. Because De Vita

3 provides explicit corroboration, Thabit (or Thabit and Pseudo-Ptolemy) is

42

Kaske assigns a high value to Al-Kindi (and the Picatrix) and diminishes Walker,

Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl’s opinion that Ficino relied most heavily on Plotinus and other

Neoplatonists: Ficino, 2002, 50. Kaske is correct that this previous group of Warburg scholars

could not benefit from D’Alverny and Hudry’s 1975 critical edition of the De radiis and

Pingree’s 1986 edition of the Picatrix. It is the very nature of scholarship to reevaluate claims

with new sources, as the evidence produced by Ficino’s marginalia in the Parisian manuscript

allows one to do at present.

43

Walker, 1958; as well as Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl, 1964, focus on Ennead 4.4.26;

Kaske, on Al-Kindi’s De radiis, in Ficino, 2002, 50; and Copenhaver, 1988, on Ficino’s

marginal glosses to Proclus’s De sacrificio et magia.

44

Ficino, 2002, 278 (1576, 541); 340 (1576, 558).

45

For example, MS Florence, LAUR, Plut. 30.29, and MS Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale

Centrale (hereafter BNCF), II.iii.214. See Carmody, 167–97; Pingree; the catalogue

description of MS Florence, LAUR, Plut. 89, sup. 38 in Gentile and Gilly, 107–12;

Thorndike; Weill-Parot, 2002a, 40–79, 91–102; Lucentini and Perrone Compagni, 59–61,

64–66; Ockenstr€om, 10–11, 22–25.

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

55

the more cautious conclusion.46 Despite this ambiguity, the note offers clear

connections between the manuscript and Ficino’s De Vita. Usually categorized

either as popular or technical Hermetica, Thabit’s and Pseudo-Ptolemy’s

treatises are works of practical magic that explain how talismans, statues,

images, or figures function according to astrological theories of decanic

personifications. Although Ficino’s annotation does not address talismanic

magic as such, by including Thabit in the note he reveals that he glosses the

Plotinian passage not only with Al-Kindi’s theoretical magic and Proclus’s

philosophical explanations of celestial series, but also with medieval works of

practical magic.

A final thought remains on the Neoplatonic terminology found in Ficino’s

marginal note. The term συναφή (union, contact, or connection) in the Plotinus

passage that Ficino comments will gain importance for Iamblichus and later

Neoplatonism: “Their knowledge of prayers comes about according to a contact

[σύναψιν] and according to an order of dispositions such as this, and the same

goes for their productions. And in the magi’s art all is done toward this union

[συναφὲς]; but these things follow powers sympathetically.”47 The term expresses

the kind of union by which one comes into contact (without discursive reasoning)

with the divine or the Neoplatonic One. While A. H. Armstrong employs

“linking” for this term, Pierre Hadot, Henri Dominique Saffrey, and AlainPhilippe Segonds translate it respectively as “co€ıncidence” and as “entrer en

contact,” and Ficino accurately stays within this semantic realm by translating it as

“contactum” or “contiguum” and by expressing the concept in the note with

“contiguitate.”48 In the following treatise on sight (Ennead 4.5) Plotinus employs

this same concept to explain how sight comes into contact with and touches, so to

speak, what is seen, so it is only appropriate that Ficino employs optical theories to

gloss this earlier passage where Plotinus asks how prayer brings us into contact with

the divine.49

If one continues to follow the traces of Ficino’s interpretation of Plotinus on

prayer, one sees that the Greek notabilia multiply on the following folio of the

Parisian manuscript, but that Ficino’s reading also turns to daemons: “All the senses

are in the soul of the earth. Thus also Psellus attributes all the senses to daemons and

discusses about magic.”50 Ficino continues:

46

Ficino, 2002, 287, 340 (De Vita 3.8 and 3.18).

Plotinus, 1964–83, 2:84 (Ennead 4.4.26.3).

48

Iamblichus, 2013, 5–6. (De mysteriis 1.3), with Saffrey and Segonds’s translation. For

Armstrong’s translation, see Plotinus, 1989, 4:307; for Hadot’s translation, see Plotinus, 1994,

101 (Ennead 6.9.8). Ficino’s translations, see Plotinus, 1580, 418; Iamblichus, 1497, a.iir.

49

See, for example, Vasiliu, 2015.

50

MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 158r: “πᾶσαι αἰσθήσεις ἐν ψυχῆ τῆς γῆς. sic item

omnes sensus demonibus tribuit Psellus et de magia tractat.”

47

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�56

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

In the Meno the opinion of Empedocles is mentioned stating that certain effluvia

emanate from us through pores into the pores of things, and that some [effluvia]

are sensed but others are not at all. Remember that daemons have the most

unnatural bodies. Therefore they act in many places at the same time, and also

emit their effluences at a distance in the manner of stars, alter the air and move

quickly, keenly sense from far away, see objects at a distance and act on them only

by moving not so much across wide distances as by elevation on high, and bring

together passives with actives, in the proper way, place, and time. Democritus also

says that understanding happens from the emission of influxes of real presences by

things, that is for example, from a human there is a human power. Roger Bacon

and Blasius of Parma prove that in nature real impressions of hidden realities

occur. On this see also Synesius.51

Here Ficino further reasons about Plotinus on prayer, comparing the effects of

daemons and stars according to models of emission at a distance based on theories

from Empedocles in Plato’s Meno and from Democritus.52 He also resumes his

gloss of Plotinus with medieval scientific writings on geometric optics, perspective,

and light, jotting down a comparison with the writings on occult impressions from

Roger Bacon the philosopher, mathematician Blasius of Parma (ca. 1365–1416),

and the Neoplatonist, rhetorician, and bishop, Synesius (ca. 373–ca. 414).53

51

Ibid.: “In Menone tangitur opinio Empedoclis ponentis emanare a nobis defluxus quosdam per

poros in rerum poros et quosdam sentiri quosdam minime. Tu memento demones habere corpora

ingentissima. Ideo agere simultim multis in locis, item emittere influxus suos procul more stellarum,

et alterare aeres, et cito moveri, et acute proculque sentire, et non tantum per motum in latum quam

in per elevationem in altum videre remota et agere in ea, et appropinquare passibilia agentibus, debito

modo loco tempore; Intellegere de emissione a rebus influxuum realium id est ab homine hominis vis

dicit etiam Democritus et proba[n]t Rogerius Bacho et Blasius Parmensis ut natura fiunt impressiones

reales occultae. De his Synesius.” NB: square brackets are used here to indicate added text.

52

Plato, Meno, 76c, in Bekker, 2.1:337–38. One scholar argues that Empedocles was a magician:

Kingsley, 1995. Democritus could refer, for Ficino, to the writings of Bolus of Mendes (ca. 200

BCE), known by the pseudonym Democritus, one of the first alchemical authors avant la lettre

whose writings on the sympathetic relationship of occult powers, plants, gems, and celestial bodies

were known in the Middle Ages through the works of Rhazes (Muhammad ibn Zakariyā Rāzī,

854–925), Avicenna (Ibn-Sīnā, ca. 980–1037), and Avenzoar (Ibn Zuhr, 1094–1162)—three

authors known to Ficino. See Festugi�ere, 1:197–200. If the writings of Bolus are intended, this

would offer a hint toward Ficino’s sometimes debated interests in alchemy, which does not figure

prominently in his works. On the state of the question, see Forshaw; Matton.

53

Lindberg, 1976, esp. 18–32; Lindberg, 1996; Vescovini, 1979, 257–60; Vescovini, 2003,

45–103, 319–58; Vescovini, 2008, 403–23; Blaise de Parme, 2009. There are also interesting

marginalia in Ficino’s Plotinus manuscript (MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816) about vision, light, rays,

and eyes, referring to geometric theories of optics and pyramids of light rays on fol. 168v

(Ennead 4.5.3) and fols. 169v–170r (Ennead 4.5.5.), with a reference to Ennead 1.7.1.

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

57

Ficino puts forward a daemonological interpretation of a passage from the Enneads

that does not speak explicitly about daemons by reading it through medieval science

and late ancient pneumatology. The reference to Synesius, who writes on the spirit and

the imagination, shows that for Ficino the terminology related to spirit (πνεῦμαspiritus) in the Plotinus passage encompasses a medium between body and soul

(human or cosmic) and a personal spirit or daemon.54 Questioning how and whether

prayers are received, Plotinus asks rhetorically if the earth has senses. He answers that

not all beings in the cosmos have the same senses and organs and proposes that the

sympathetic relationship between beings is accomplished through a “breath,”

“spiritual being,” or “spirit.” Plotinus states that earth’s generative power is

a “spiritual being,” that its soul “is a god,” and, in a passage that Ficino highlights

in the margins, that the earth has a soul and intelligence, “which men, with

a divinatory nature and in consultation of oracles, name Hestia and Demeter.”55 This

passage is the source of inspiration for De Vita 3’s opening section on images and

figures. Ficino notes that Platonists and Pythagoreans think that all rays converge their

powers (transmitted along linear vectors) onto a single point at the center of the earth.

“They believe,” he writes, “the fire that breaths out of the center to be Vesta’s

[Hestia’s], since indeed they thought Vesta was the life and patron deity of the earth.

And therefore the ancients used to construct the temple of Vesta in the middle of cities

and place a perpetual fire in the middle of it.”56

A few chapters later, having explained that the heavens do not need memory to

receive prayers, Plotinus asks if they are complicit when the one praying requests

help to commit wrongs. There, Ficino writes a few notes about theurgy: “perception

in the stars; for how prayers have strength, read in Iamblichus and Proclus’s

commentary on the Timaeus; how the stars hear prayers; whether the power of magi

comes from working with the gods or evil work.”57 It is clear that Ficino is not only

concerned with prayers to commit wrongs but with prayers and magic in general. In

another long exegetical Latin note he continues to draw on the kinship between

Proclus, the De imaginibus, and Al-Kindi but also includes a gloss from Porphyry’s

54

Walker, 1958, 45–53.

Plotinus, 1964–83, 2:84–85 (Ennead 4.4.26.23–31); 2:85 (Ennead 4.4.27.13–17).

56

Ficino, 2002, 323 (1576, 553). Ficino’s identification of Plotinus’s Hestia with

Pythagorean doctrines leads him to misinterpret the Pythagorean Philolaus’s heliocentric

cosmology since the Pythagorean postulated an unlimited fire, called hearth or Hestia, at the

center of the universe not the earth. On Philolaus’s cosmology see Huffman, 231–88.

57

Ennead 4.4.30. MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 160r: “αἰσθήσεις ἐν τοῖς ἄστροις. Quod

orationes valent et quomodo Iamblichum lege et Proculum in timaeo. πῶς ἄστρα κλύουσιν

εὐχῶν. δύναμις τῶν μάγων πότερον θεοὶ συνεργοὶ γίνονται φάυλοις ἔργοις.” Ficino

marks the passages on prayer in his manuscript of Proclus’s In Timaeum, MS Florence,

Biblioteca Riccardiana (hereafter RICC), 24, and translates them in his own Timaeus

commentary.

55

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�58

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

De abstinentia (On abstinence) and a reference to the eleventh-century work on

magic, the Ghāyat al-Hakīm, by the pseudo-Maslama al-Majrītī, known in the Latin

_

_

translation as the Picatrix. The Picatrix has long been suspected as a source for De

Vita 3—in fact, Ficino was perhaps one of the first to study it since the thirteenth

century.58 He writes:

Here consider the works De imaginibus, following Proclus, Al-Kindi, and the

Picatrix. However, because a figure has power in some degree it is clear that it

produces various aspects. Certainly also because species of figures and numbers

follow their ideas they have a single power. They have efficacy, not as a quantity

but as having something more formal, and they are properties of the figures. But if

forms and numbers were not to have fixed powers they would be connected by

chance, nor would one similarly observe these things in nature always in a fixed

order. But see what you said about this in the first book on the stars of Plotinus; it

concerns other things unless celestial figures and numbers act in an especially

stable manner when either our figures are able to act on our eyes as much as

possible or numbers from above on our ears. Porphyry says that the Pythagoreans

would invoke gods with numbers and figures and would be filled with prophecy,

and that indefinite dimension may be ineffectual as matter but a formal figure is

something [effectual], and certain species in nature therefore have power.59

Here Ficino begins to develop what he further explains in De Vita 3: figures and

numbers project a single efficacious power through a series of species that

participate in the radiation of a noetic chain headed by an idea. Such a projection

58

Already in the 1920s Warburg and scholars associated with his library suspected that De

Vita 3 drew from the Picatrix: Saxl, 232–33; Ritter, 114–15. The earliest indirect evidence of

Ficino’s use of the Picatrix is a letter from Michele Acciari to Filiopo Valori, published by

Delcorno Branca, which tells that Valori had asked Ficino for the Picatrix, to which Ficino

responded that he already returned the manuscript to its owner (likely Giorgio Ciprio) but that

he had taken what was valuable from it for his De Vita. Delcorno Branca; Garin, 1976b;

Gentile also notes the next marginal annotation that refers to the Picatrix in Gentile and Gilly,

137–38; Perrone Compagni.

59

MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 162v: “Hic pone de imaginibus secundum Proclum,

Alchindum, Picatricem. Quod autem figura aliquid possit patet quod movet aspectus varios. Item

quia certe species figurarum et numerorum suas secuntur ideas unam vim habent. Hec habent

efficaciam non prout quantitas sunt sed prout formalius aliquid habent et formarum propria sunt.

Nisi vero figure et numeri certas vires haberent, casu contingerent, neque natura hec certo semper

ordine similiter observaret. Sed vide quod de his dixistis in primo libri de astris Plotini; aliorum

est, ni celestes figure et numeri praesertim stabiles aliquid agunt cum et figure nostre ad oculos et

numeri insuper ad aures possint quam plurimum. Porphyrius dicit quod Pythagorici numeris et

figuris advocant deosum et vaticinio implebanturque dimensio indeterminata sit inefficax qua

materia sed figura formale aliquid est et certa species in natura ergo vim habent.”

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

59

travels on geometric vectors in line with celestial aspects. In essence, this

ontological theory glosses how Plotinus’s Intellect emanates its reasons to the

world, implanting them as seminal reasons in nature. Figures tap into the series

with visual phenomena while numbers only require acoustic rhythm and tone.

Reconstructing Ficino’s textual work through marginalia, it is possible to identify

which books he had on his desk to gloss Plotinus on prayer. Drawing from

Porphyry’s De abstinentia, which Ficino translated in 1488–89, the notes mention

that the Pythagoreans invoke gods and perform divinatory prophecy with figures and

numbers (which Ficino seems to interpret as Pythagorean songs).60 The manuscript

in the Vallicelliana library that has the Greek text of Proclus’s De sacrificio et magia

also contains a draft copy of Ficino’s translation of the excerpts of Porphyry’s De

abstinentia. In this manuscript, next to the passage in De abstinentia just quoted in his

marginalia to Plotinus, Ficino writes the same annotation verbatim. The only variant,

“deos/deum” (“gods/god”; he gives both with a superscript in the Parisian text), offers

the slightest glimpse into the shift from polytheism to monotheism (fig. 2).61

A little later in his Plotinus manuscript, Ficino again quotes Pythagorean

sources and Porphyry to gloss Plotinus on whether invoking the heavens through

prayer can be beneficial or maleficent to life. The note is written in the hand of

his amanuensis Luca Fabiani:

Pythagoras says that invocated gods approach us not voluntarily but compelled

with a certain necessity that is not so much by election as with a certain lure of

nature by which we are thus affected, and from this we seem to draw them out

in such a manner. Porphyry speaks about this in his book On the Way to the

Intelligible, and in his book On Oracles he explains that magic was delivered to

us from the gods who taught what matter, images, and prayers they rejoiced in.

Read about this in Eusebius.62

Ficino finds his material from Porphyry’s Sententiae, or De via ad intelligibile

(Sentences or on the way to the intelligible), and De philosophia ex oraculis

60

Porphyry, 1979, 2:102–03 (De abstinentia 2.36). Ficino translated parts of book 2,

paragraphs 37–61, which he sent to Braccio Martelli (1576, 876–79). He included them in the

1497 Aldine incunabulum with other extracts from books 1, 2, 3, and 4. See Toussaint’s

introduction in Iamblichus, 2006, IV–VIII. The passage in question is found at ibid., i.vi r–v.

61

MS Rome, VALL, F 20, fol. 152v: “Pythagorici numeris et figuris advocant deum et

vaticinio implebantur.”

62

Ennead 4.4.38. MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 164r: “Pythagoras ait Deos invocatos

accedere ad nos non sponte, sed quadam necessitate compulsos id est non tam electione quam

quodam tractu naturae quo nos sic affecti sic inde haurire videmur. De his Porphyrius dicit in

libro de via ad intelligibile et in libro de oraculis tractat magicam fuisse nobis traditam a superis

qui docuerint quibus materiis et imaginibus et orationibus gaudeant. Lege apud Eusebium.”

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�60

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

Figure 2. Ficino’s notes to Porphyry, De abstientia. MS Rome, Biblioteca Vallicelliana, F 20,

fol. 152v.

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

61

haurienda (On philosophy drawn from oracles), a work openly critical of Christianity

that Ficino simply calls Liber de oraculis.63 The brief passing reference to Eusebius

indicates that his source is Praeparatio evangelica (Preparation for the Gospels), which

preserves most of the extant fragments of De philosophia ex oraculis haurienda.64 In fact,

based on Fabiani’s Latin, one can ascertain that Ficino was quoting from George of

Trebizond’s (1395–1472/73) translation of Eusebius’s Praeparatio evangelica.65 The

verb that Ficino uses in the annotation, “haurire” (“to draw out”), which George does

not use in his translation of the specific passage, clearly fits within De Vita 3’s semantic

field. De Vita 3 repeatedly employs “haurire” to denote how one can take in or drink

life and influences from the heavens.66 Its connotation of draining, or pouring, as in

water streaming downwards from a source, illustrates the concept’s emanative

metaphysics. The verb figures prominently in Ficino’s previous formulation of the

work’s title in the dedicatory letter to Mathias Corvinus (1443–90), king of Hungary:

“Now among the books of Plotinus destined for the great Lorenzo de’ Medici, I had

recently composed a commentary (numbered among the rest of our commentaries on

him) on the book of Plotinus which discusses drawing favor down from the heavens

[de favore coelitus hauriendo].”67

63

Porphyry, 2005, 1:308–11, 326–31; 2:795–96, 804–07 (Sentences: 1–6, 27–29). De philosophia

ex oraculis haurienda is the Latin title commonly adopted since G. Wolff’s edition: Porphyry, 1856.

64

Eusebius, 1954–56, 43.1:236–42 (Praeparatio evangelica 5.8–9). Other Porphyry

fragments about the gods’ teachings: 5.11–14 and 6.4.

65

Eusebius, 1480, fol. 112r (5.6): “Magnam vero naturam daemonum ea quae istis subiecit

maxime ostendunt. Recte inquit a Pythagora dictum est non sponte invocatos deos: sed

necessitate quadam impulsos accedere.” George’s translation of Praeparatio evangelica 5.6, or

5.8 in the standard division. For Ficino’s use of George’s translation, see Monfasani. On the

Pythagorean “deos invocatos,” see also Plotinus, 1580, 433 (Ennead 4.4.38–39).

66

For example, Ficino, 2002, 242–63, 288–97 (De Vita 3.1–4, 11).

67

Ficino, 2002, 236–39 (1576, 529). The De Vita Coelitus Comparanda also seems to have

been known in later generations by the title De Vita Coelitus Haurienda (On drawing life from

the heavens); for example, Jacques Gohory (1520–76), cited in Walker, 1958, 104n1; Forshaw,

265n66. On the work’s title, see Kristeller, 1:lxxxiii–lxxxvi. Given certain thematic connections

between Ficino’s and Porphyry’s work, it would be tempting to draw a direct line of

transmission from Ficino’s title De Vita Coelitus Haurienda to Wolff’s choice of De philosophia

ex oraculis haurienda for Porphyry’s Περὶ τῆς ἐκ λογίων φιλοσοφίας. Although Wolff

knows Ficino’s Neoplatonic writings (especially through G. F. Creuzer’s edition of Plotinus), as

far as I have been able to ascertain Ficino simply refers to Porphyry’s work as the Liber de

oraculis. Moreover, since George of Trebizond uses Liber de oraculis, Liber responsorum, and

Liber de responsis, I have not been able to identify a Latin translation for the title of Porphyry’s

work that predates Ficino’s work that would indicate that Ficino’s choice of De Vita Coelitus

Haurienda intentionally alludes to Porphyry’s De philosophia ex oraculis haurienda. In the first

early modern scholarly study on Porphyry, Dissertatio De Vita et Scriptis Porphyrii Philosophi

(1630), Lucas Holstenius employs De philosophia ex oraculis.

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�62

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

How vocalizations (prayers, invocations, sacramental words of consecration,

etc.) call the divine down to earth is important for the theologies and religious

practices of both Christians and ancient Neoplatonists. In De Vita 3.21 Ficino

asks why certain sounds carry specific meaning and how voice works with or on

the divine:

That a specific and great power exists in specific words, is the claim of Origen

in Contra Celsum, of Synesius and Al-Kindi where they argue about magic,

and likewise of Zoroaster where he forbids the alteration of barbarian words,

and also of Iamblichus in the course of the same argument. The Pythagoreans

also make this claim, who used to perform wonders by words, songs, and

sounds in the Phoebean and Orphic manner. The Hebrew doctors of old

practiced this more than anyone else; and all poets sing of the wondrous things

that are brought about by songs. And even the famous and venerable Cato in

his De re rustica sometimes uses barbarous incantations to cure the disease of

his farm animals. But it is better to skip incantations. Nevertheless, that

singing through which the young David used to relieve Saul’s insanity—

unless the sacred text demands that it be attributed to divine agency—one

might attribute to nature.68

Here Ficino is not interested specifically in prayers to god(s) or saints, but how voice

works with or on the heavens in general. This is also Plotinus’s exact topic. Like

Plotinus and Porphyry, Ficino notes that the heavens do not freely choose to react to

certain utterances since they neither hear nor remember prayers. Invocations and

prayers, however, do not constrain the divine either. Rather, words have powers that

correspond to the heavens by way of natural influences that function sympathetically

like harmonic ratios (sound) and geometric analogies (image).

The final marginal annotation significant for analyzing the connecting tissues

between Ficino’s interpretation of Plotinus and the origins of De Vita 3 addresses

this very issue. After a short Greek note in his manuscript, next to Plotinus’s

explanation that magic functions through love and sympathy, stating, “On

magic, how is it done, what is its source?” Ficino reminds himself to:

See Proclus On Magic, as well as Iamblichus, Al-Kindi, and the Picatrix, and

how there may be an attraction of influxes to us not only through different

reasons favorably disposed to the heavens but also through precise

imaginations, aspects, prayers, and words. Zoroaster says about the power

of words that you should not change barbarian names. See the Cratylus on

how the air having thus been fractured by instruments [i.e., the tongue or

a musical instrument] and having been unified with a specific signification

68

Ficino, 2002, 354–55 (1576, 562).

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

63

through the imagination draws vital power through the spiritual imagination

from the world soul and from celestial rays. But note that an aspect is most

powerful with the imagination. The Pythagoreans would perform wonders

with words, and I pass over the fact that they would chant exercises [i.e., forms

of incantations] publicly. Concerning these matters Virgil in his Bucolics and

also the Orphic Hymns reveal this. However much more akin the vocalized

matter is with the heavens than other matters, so much more it receives special

power from heaven rather than the composition of other matters.69

Ficino here reiterates the same group of sources as the previously discussed notes

to Plotinus and adds the Oracula Chaldaica (Chaldean oracles; Zoroaster),

Virgil’s Eclogues, and the Orphic Hymns. The connections between this

annotation and the paragraph from De Vita 3.21 quoted above are clear, and

show Ficino working on the material at an earlier stage.

He begins with the same argument that only specific vocalizations carry

power, especially when they also correspond to precise aspects and imaginations.

Although they differ from one another, the set of authoritative sources that

Ficino quotes in the annotation and De Vita 3.21 are closely related. He repeats

the Chaldean Oracle in both cases with similar terms.70 He also restates the

reference to Pythagorean singing, taken from Iamblichus’s De secta pythagorica.71

Ficino, however, uses the Latin term “exercitatio” in the annotation to Plotinus

Ennead 4.4.40–42. MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 165r: “Περὶ τῶν γοητείων, πῶς,

πόθεν Vide Proculi magiam et Iamblichum et Alkindum et Picatricem et quomodo non solum

per alias superis accommodatas rationes fit attractio influxuum ad nos sed etiam per certas

imaginationes, aspectus, orationes, verba. De vi verborum dicit Zoroaster nomina barbara ne

permutes. Vide Cratylum quomodo aer ita fractus et organicis et significatione certa per

imaginationem unificatus trahit vitalem vim per spiritalem imaginationem ab anima mundi et

a radiis celestibus. Sed nota quod cum imaginatione aspectus potest plurimum. Pythagorici

nominibus mirabilia operabantur ut praetermittam quid exercitationes vulgo canant. De quibus

Virgilius in Buccolicis etiam Hymni Orphici hoc ostendunt. Quanto vocalis materia cognatior

est celesti quam alias tanto magis vim specialem celitus accipit quam materiarum aliarum

compositio.” Two brief Greek notes follow: “πῶς ἄστρα νεύουσιν εὐχαῖς, καὶ πότερον

[πότενον sic] ἀκοῦωσιν. πάντα ἐν κόσμω συμπάσχουσιν, ὥσπερ ὅμοιαι χορδαὶ ἐν

λύραις” (“How do stars grant prayers, and whether they listen. All things in the cosmos are in

sympathy just as strings on a lyre are alike”).

70

Ficino, 2002, 354 (1576, 562): “Item Zoroaster vetans barbara verba mutari.” MS Paris,

BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 165r: “De vi verborum dicit Zoroaster nomina barbara ne permutes.” On

the oracle, see Kroll, 58 (Psellus, expos. or. chald. 1132c); Lewy, 238–40.

71

Ficino, 2002, 354 (1576, 562): “Item Pythagoricis verbis et cantibus atque sonis mirabilia

quaedam Pheobi et Orphei more facere consueti.” MS Paris, BnF, Gr. 1816, fol. 165r:

“Pythagorici nominibus mirabilia operabantur ut praetermittam quod exercitationes vulgo

canant.” The source is Iamblichus, 1975, 15–16, 25.

69

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�64

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

to translate precise Pythagorean terms for a kind of musical arrangement

(ἐξάρτυσις) and its related exercises (ἄσκησις) and devout practices

(ἐπιτήδευσις). He does this in his own translation of the De secta pythagorica

as well, but he replaces “exercitatio” with the more general “verbum” and “cantus”

(“song”; “incantation”) in De Vita 3.21.72 Ficino reiterates Iamblichus, Al-Kindi,

and the Orphic Hymns in both the annotation and De Vita 3.21, but seems to

replace Virgil’s Eclogues with Cato’s De re rustica (On agriculture) for a Roman

example, and removes the references to Plato’s Cratylus, the Picatrix, and Proclus

from De Vita 3.21, mentioning instead Origen, Synesius, the Hebrew doctors, and

the first book of Samuel. Ficino’s alternative sources might simply indicate a later

revision or they might show that he preferred to include biblical and Christian

sources (even if unorthodox) instead of Platonic and magical ones. These omissions

could account for his statement in the passage in question from De Vita 3.21 that

“it is better to skip incantations.”73

In De Vita 3 Ficino specifies three performative steps for invoking heavenly

forces. First, one needs to match the specific powers of stars, constellations, and

aspects, with exact verbal significations. Second, one should imitate the correct

region, persona, and tone that correspond to specific words bearing celestial

signification. That is, one should pronounce the words in the manner of

a specific persona, as, for example, Zoroastrian, Apollonian, Dionysian, Orphic,

or Pythagorean personas. This second stage also includes the use of fumigations

and the performance of gestures, dance, and ritual.74 Third, one ought to imitate

those who observe the correct time to perform the rite—that is, when the stars

have specific positions and aspects that best accommodate their influx to our

words, personas, and performances.75 This argument shares its technical

terminology with the annotations (for example, accommodare, aspectus, significatio,

influxum, and cantus), and, like the annotations, all the mimetic dimensions of

words, personas, and performances also depend on a philosophical theory of

spiritual imagination.

Despite De Vita 3’s forays into the power of sight (figures, images, talismans,

statues, etc.), according to Ficino it is sounds—prayers, hymns, words, invocations,

incantations, music—that best transmit spiritual influences from the heavens.

Walker presented Ficino’s argument in these passages that the sound is the aerial

spirit of hearing (aereus auris spiritus) as an Augustinian-Aristotelian epistemology

72

On the difficult term “ἐξάρτσυις,” see Delatte, 136–38. “Exercitatio” is also the term

that Ficino uses in his own translation of the De secta pythagorica, which I am presently editing

for publication. On this work in Ficino’s oeuvre, see Kristeller, 1:cxlv–cxlvi; Gentile; Celenza,

1999; Celenza, 2001; Robichaud, 2016.

73

Ficino, 2002, 354–55 (1576, 562).

74

On Ficino’s Orphic persona, see Walker, 1958, 12–35.

75

Ficino, 2002, 357–59 (1576, 562–63).

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

65

that the medium of sensation must correspond to its organ, but it is clear that

it is grounded in Neoplatonic reasoning.76 After explaining the three steps,

Ficino writes:

But remember that song is a most powerful imitator of all things. . . . Now the

very matter of song, indeed, is altogether purer and more similar to the

heavens than is the matter of medicine. For this too is air, hot or warm, still

breathing and somehow living; like an animal, it is composed of certain parts

and limbs of its own and not only possesses motion and displays passion but

even carries meaning like a mind, so that it can be said to be a kind of airy and

rational animal. Song, therefore, which is full of spirit and meaning—if it

corresponds to this or that constellation not only in the things it signifies, its

parts, and the form that results from those parts, but also in the disposition of

the imagination—has as much power as does any other combination of things

[e.g., a medicine] and casts it into the singer and from him into the nearby

listener.77

Ficino had already planted the seed to this theory in Neoplatonic terms in the

argument of the last annotation to Plotinus quoted above. His marginalia reveal

an identical principle: the closer the medium of voice is to the heavens, the more

it will receive its power. Unlike the material medium of images or medicine,

vocalization draws more power from the heavens since its very medium, spirit, is

identical to the spiritual influx received from the heavens.

To understand this last passage from Plotinus, Ficino pairs Neoplatonic

pneumatology with various accounts of the symbolic power of barbarian divine

names. Plato’s Cratylus is the root text for this kind of understanding of symbols,

and in his manuscript margins Ficino glosses its discussion of barbarian names for

gods with the Chaldean Oracle that states that one should not alter or translate

barbarian names.78 Ficino theorizes that a tongue or an instrument breaks air,

which according to Plato is a continuous flux, in order to produce a sound. The

imagination then generates signification and tunes the sound in a harmonious

ratio with the heavens.79 Our spiritual imagination, he believes, comes into contact

with the spiritual imagination of the world soul and thereby reaches it without the

aid of discursive reasoning. Since Plotinus claims that the heavens do not

deliberately answer our supplications, Ficino reasons that the efficacy of prayers

76

Walker, 1958, 7–8.

Ficino, 2002, 358–59 (1576, 563).

78

Plato, Cratylus, 425d–426b in Bekker, 2.2:89–92. De Vita 3.21 refers to Iamblichus,

2013, 189–93 (De mysteriis 7.4–5).

79

Plato, Cratylus, 410b in Bekker, 2.2:58–60. Ficino, 2001–06, 3:176–79 (Platonic

Theology 10.7.5).

77

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�66

R E N AI S S A N C E QU A RT E R L Y

VOLUME LXX, NO. 1

does not depend on a discursive process of communication to produce meaning

and signification. Prayers and other vocalizations do not function by generating an

understanding in discourse. Discursive communication could be translated into

different languages, but the symbolic power of words comes from the very formal

structure and measure of the vocalized spiritual sound itself: its mathematical ratio

with the heavens.

This theory reflects the formal progression of De Vita 3 as a whole, where modes

of drawing influences from the heavens resemble something like a threefold heuristic

structure (fig. 3). Following Ficino’s discussion of nature and the cosmos in De Vita

3, the formal Neoplatonic structure investigates art sequentially: from matter, to

matter with form, to spiritual form and the figures and numbers that correspond to

intelligible form. This three-stage order agrees with the principles expressed in the

opening paragraph of De Vita 3.17: “For thus figures, numbers and rays, since there

they are sustained by no other material, seem practically to constitute what things are

made of [quasi substantiales]. And since, in the order of being, mathematical forms

precede physical ones, being more simple and less defective, then deservedly they

claim the most dignity in the primary—that is, the celestial—levels of the cosmos, so

that consequently as much comes about from number, figure, and light as from

some elemental property.”80 Additionally, in the middle section of this threefold

categorization (De Vita 3.18), Ficino provides a further tripartite classification for

engraved images and figures.81 Thus even within the middle section devoted to

images and figures one notices a hierarchy that moves away from the visible body

toward the intelligible form. It progresses from mimetic representations of visible

phenomena (the zoomorphic representations of star constellations), to nonvisible

but imaginable phenomena (the decanic personifications of the heavens), to

nonrepresentational but still mimetic symbols.

However, this diagrammatic structure of De Vita 3 remains only a heuristic

guide since Ficino’s cosmos does not separate absolutely between nature and art,

nor between sensible and intelligible. Instead of a definite separation between

sensible and intelligible, there is a constant that pervades throughout the

complete spectrum of the cosmos: the continuous emanation of the

superabundant power of the Neoplatonic One. Ficino conceives the whole

order of De Vita 3 with a Neoplatonic method whereby one removes levels of

complexity from phenomena to reach simple unity.82 When sound is performed

in a nondiscursive, or noetic, manner (as in certain prayers or vocalizations of

80

Ficino, 2002, 328–29 (1576, 555).

Ficino, 2002, 333–35 (1576, 556).

82

Aphaeresis, for instance, abstracts levels of complexity in mathematics; one moves from

the study of bodies in motion (astronomy) and their complex ratios (music), to static bodies

(stereometry), to plane figures (plane geometry), to lines, and, finally, to a point (a simple and

singular arithmetical unit).

81

This content downloaded from 129.074.250.206 on March 10, 2017 14:21:01 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

�FICINO ON FORCE, MAGIC, AND PRAYERS

67

Figure 3. Diagram of the structure of Ficino’s De Vita 3. Created by Joseph Bowling of the

Renaissance Society of America.

divine names) it acts as a nonrepresentational but mimetic symbol directly

signifying the divine intelligible. Such noetic symbols are closer to intelligibles

insofar as the ontological status of their mathematized medium (spirit) is prior to

material images (statues or otherwise) and medicine. While images are depicted

on a material medium, sound does not require a material substrate. Yet Ficino

employs theories of light to understand how sound travels. The importance of

Plotinus’s metaphysics of light is here central to his thinking. Like light, prayer

becomes a link by which one touches the divine. According to Ficino, therefore,

Plotinian prayers and invocations turn one away from the variety of complex

connections in the cosmos. These spiritual conversions are intellectual (re)alignments

to accommodate a simpler contact with the heavens and intelligibles, and perhaps to

participate in the most simple contact, a union with the One.83

DATING FICINO’S ANNOTATIONS AND

PLOTINUS ON ASPECTS

One of the notes discussed above (to Ennead 4.4.34) includes Ficino’s own

reminder to see what he wrote on the topic of astrological aspects in Plotinus’s

first book on the stars (Ennead 2.3.1). Ennead 2.3 contains one of Plotinus’s

most severe attacks on the belief that stars cause events. Instead, Plotinus argues

that stars may merely serve as signs for events. This argument greatly influenced

Ficino’s own thinking about astrology, and aligns well with his Disputatio

83

See Giglioni, 24–30.