Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

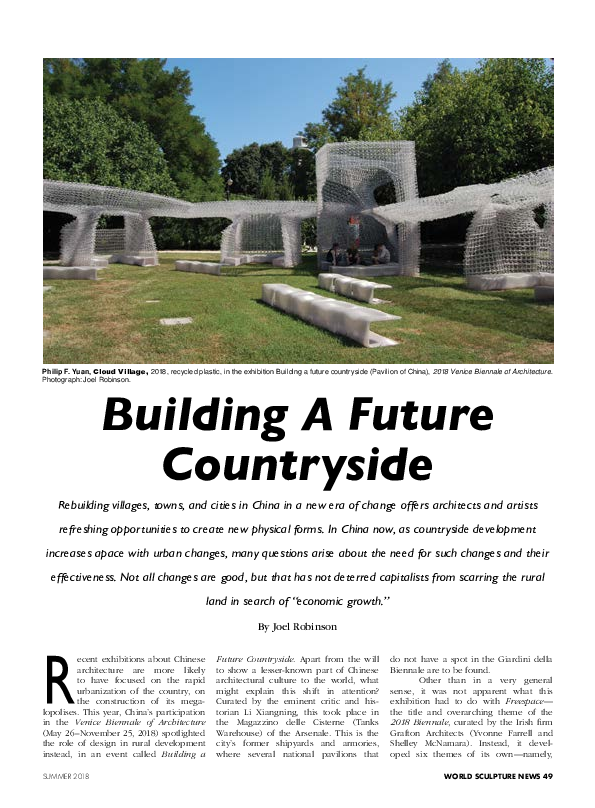

'Building a Future Countryside: China Pavilion at the 2018 VAB'

'Building a Future Countryside: China Pavilion at the 2018 VAB'

2018, World Sculpture News

Related Papers

In the rural areas of China, construction is growing vigorously, and the question of how to realize the creative inheritance and development of these areas in the regional context, as well as the exploration of new construction methods and paths, are important problems. Nowadays, there are two developing trends in terms of research methods. Firstly, the boundaries between various disciplines are becoming increasingly blurred, and interdisciplinary theoretical reference has become an effective means of realizing innovation in this field. The other trend relates to the great development of digital technology, such as parameterization and spatial information technology. This technological innovation sheds new light on rural image construction. This study aims to draw on the montage art concept and organization techniques and to integrate the new technical language into the construction of new aesthetic orientations and context-related inheritance paths of rural historical places in Chi...

Structures and Architecture

COCOON' a bamboo building with integration of digital design and low-tech construction2016 •

Heritage 2012, International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development, At Porto, Portugal, Volume: 978-989-95671-8-4

Bamboo entwines: a design intervention to envision culture and innovation values of local crafts2012 •

We introduce a design research project about design and local crafts. The research playground belongs to a wider program about social innovation located in Chongming Island, fundamental rural area of Shanghai. We contribute to new directions of urban planning taking into account community factors, and the immaterial values of local resource like bamboo craftsmanship. We start a co-design project interacting directly with the locals, working to reconstruct the social cohesion around a stronger local identity. The paper fully describe the research and design activities. Even the project is still a work-in-progress, it has already emerged the notion of cultural artifacts as new heritage: value is not technical quality embedded in forms and processes, but in the way they are integrated in the social lifestyles and patterns.

2020 •

Abandonment of mining sites and buildings has been an issue that is on the rise today, in the age of rapid globalisation and advancement. In certain mining towns, residents move away from the site once resources are depleted and weren’t able to finance the town, which in turn causes vacant and abandonment of the site, leaving everything behind to be neglected or underused. As Germany is currently preparing for a coal energy phase-out, the scene of unused mining sites is reoccurring when these neglected sites provide potential reuse and growth. The studio will explore the complexities and chances of transforming post-carbon age industrial environments, transnational sustainable energy production, and sustainable jobs and living concepts. To develop an urban and architectural concept for a cool coal exit, this thesis will research the methodology of revitalising abandoned mining sites. For the past 40 years, as a community, we have become in- increasingly aware of the need to protect the environment where we can understand the concern, given that the damage done during the industrial revolution continues to affect our climate. In the environmentally conscious society in which we now reside, the mining industry is often portrayed as an antagonist, leaving behind polluted land and ravaged environments. Most people don’t realise that most of the mined site does not return to their former glory, either in making the mined site as habitable as they were before. Mined sites can be reclaimed into different programs, however, in Germany, the trend is to reclaim the mined sites as forests, lakes or water features. Repurposing mined sites not only brings benefits to the environment but most importantly helps to boost local economies, especially in areas that affect the unemployment rates when the mines were shut down. Another issue that this proposal aims to tackle is on the number of people who live in urban areas is drastically more compared to rural areas. These developments are the process where populations moved from rural areas into urban areas. Undeniably, the gap between big cities and local existence in Germany is not as severe as in other countries due to the federal structure of 16 state capitals. However, there is still an obvious imbalance between urban and rural areas. It is said that several agricultural areas in the state of Brandenburg are expected to lose about a third of their populations by 2035. These regions experience a general lack of a job, shops, skilled crafts, doctors and banks. The main cause of outbreaks of diseases and drivers of climate change are various forms of pollution, and inadequate space for walking, cycling and active living. Other than these certain obvious physical diseases that occur throughout rapid urban development that constitutes to polluted environment, emotional or psychological issues are also another factor affecting the well-being of urban dwellers. Consequently, urban dwellers are exposed to an increased risk for different types of neuropsychiatric disorders. With the concern on the mentioned problem statement, it is envisioned to develop the abandoned mining sites through revitalisation and reclamation, with the concept of village typology development. Thus, this research focuses on the villages alongside their typologies and characteristics. In most areas, villages are linear settlements where the houses are clustered along a line, instead of a central point. For the past decades, rural areas and small towns are consistently losing young people. However, today and or in the future, it might be the other way around, moving to rural areas might be the new way of life. Urban dwellers are moving to rural areas to seek a quiet life. Most of the young people and millennials decided to uproot and enjoy the peaceful and quiet countryside. As mentioned in the problem statement, life in urban areas causes health issues because of the growing emission factors contained in big cities. Other than that, village life provides the opportunity for thought, study and mental development providing a healthier and mental physical for those that require thinking. As it is envisioned to develop the abandoned mining sites with the concept of village typology development, with these 6 characteristics, horizontal community engagement can be achieved in today’s world. The characteristic includes small and intimate, unique, specially designed to encourage social interaction, driven locally and locally responsive, useful as well as blended culture. Through the problem statement, this proposal will further explore the methodology that tackles the issue as stated. One of the methodologies is through the concept of the ecovillage, where it is a community that aims to become more sustainable in terms of social, cultural and economic and environmental. Ecovillages are deliberately designed to rebuild and restore social and natural ecosystems through participatory processes which are owned locally. Furthermore, the concept of a productive loop reinvents proactive proximities, close circular economies, and alternatives of co-production and eco-sharing systems. With the intention of production within the village, living and work are combined again which creates more opportunities for recycling, social interactions and a greater sustainable village. On the other hand, the methodology of the energy-integrated building where design solutions are incorporated with adaptive building elements and power systems into one entity to maximise the sustainability performance of energy production, consumption of resources and indoor environmental quality. This methodology will further study the norm of an energy farm that occupies a big area of the site solely for the purpose of energy harvesting and the possibilities of mixing the infrastructures of the village into a unified area. In conclusion, through the usage of the methodology, as stated, it is envisioned to design a village with the integration of urban lifestyle into rural living. With the result of this research proposal, the ideology of Villagegification is visioned to be applied on multiple abandoned mining sites with similar variance to the current site so as not to repeat the process of rapid urban development that is uncontrolled and causing a negative impact on its dwellers, and excavate the vast land opportunity to have sustainable development.

Vernacular & Earthen Architecture towards Local Development. Proceedings of 2019 ICOMOS CIAV & ISCEAH International Conference

Earthen buildings in rural Fujian. Architectural challenges for local development2019 •

Against the backdrop of the recent array of policies targeted to boost processes of revitalization in rural China, the small settlements are the object of a growing interest by scholars and institutions. Considering the controversial issues related to the countryside restructuring, among which the cultural losses determined by the phenomenon of rural urbanisation, the international debate arena is shifting its attention from development per se to sustainable development. From one side, it has already been acknowledged that being sustainable requires something more beyond being ecologically friendly. On the other side, we found there is a huge space for investigation in regard to the elaboration of practices of rural revitalization. In particular, we argue that context-related strategies of revitalization have to be defined considering what exists as a possible resource. With this perspective, we focus on fifteen earthen vernacular buildings of an ordinary rural settlement in Fujian Province, the last tangible witnesses of local traditional past. At present, most of these constructions are used only during rituals and in rare cases for living purposes, resulting in neglection and dilapidation. However, they still play a pivotal role in the rural fabric, in the way they establish spatial relations with the built form and the open space as well. These ancestral halls still influence local construction activities, by suggesting a non-written system of rules. Such a system can be read in the morphological pattern of the settlement whose backbone is still clearly recognizable. Despite it is not possible to label them as architectural heritage, they are something more than vernacular architecture. Recalling the concept of cultural heritage, they embody a complex system of values rooted in the traditional local society, combining housing, farming and rituals. This paper explores the architecture of these ancestral buildings, their current condition and their contextual relations. We found they represent a cultural asset crossing different ages, for both the rediscovery of past and the reorientation of future developments.

Frontiers of Architectural Research

Modernity in tradition: Reflections on building design and technology in the Asian vernacular2015 •

Proceedings of the International Conference on Changing Cities IV

Emerging issues of heritage in the context of China's dynamic development; metropolitan -vernacular and the quest to reinvent the identity of China's built environment: the case of the Hengjing Village2019 •

The rapid and unprecedented urbanization of the Chinese cities according to the twentieth century modern design paradigm has almost entirely replaced the traditional vernacular communities all over China and has radically changed the identity of the urban landscape. Chinese cities have grown inhuman in scale, unfriendly to the pedestrian, culturally and architecturally confusing and increasingly unpleasant to live in. As the expansion of the cities comes to a limit, awareness of the importance of preserving the cultural identity is growing in the PRC and many projects have gone forward in an attempt to preserve heritage. In 2015, the City Architectural and Planning Bureau of Ningbo has targeted over 2,000 historical buildings and has started working on creating the database of these buildings including building layouts and locations. A research team from the University of Nottingham Ningbo China, in collaboration with the Bureau, has been working on the site survey and follow-up evaluation of a total of 44 buildings in Qiu'ai Town in the southern area of Ningbo summarizing the site survey results of these historical buildings, including building type, structure and construction materials, repair status, historical and architectural values, ownership and present usage. Based on this material, this paper focuses on the case of the Hengjin Village and it discusses the housing typology, basic elements of urban space and its interstitial spaces; The concept of genius loci, including components such as geographical context, social-historical and economical context issues which, spatially combined, create an information agglomeration with influences and consequences on the space. The paper further discusses the concept of sustainability in the Chinese vernacular, the long-standing systems that people set in place for their families and society and the reflection in the building typologies, materials and construction, emerging issues of heritage and questions of identity, traditional versus modern, local-international and finally sustainability, models for decentralized / rural development, the concept of transformation versus conservation nostalgia.

Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review

Production of Space in Traditional Towns and Villages against the Backdrop of “Chinese Characteristics”: A Study of Rural Form Transformation in Huizhou2021 •

2014 •

Wood is a natural – environmentally friendly (eco-friendly) material. Wood can be recycled and contemporary architecture buildings use numerous wood-based products obtained by adding certain chemical compounds. The use of wood, as both old and new material, in modern architecture has affected the elements of traditional architecture, as an attempt to change aesthetic, constructive and stimulating effects on the overall concept of architecture. Global trends in wood re-application and woodbased products, as construction and architectural coating material, are present not only because of aesthetic, artistic and design requirements or tradition and naturebased inspiration, but also because wood is known to be eco-friendly and energyefficient and it adapts to modern trends in sustainable development and applied technology solutions to the production of materials, with the aim of maintaining connection with Nature, environment and tradition. The spirit of regionalism, the application of ...

RELATED PAPERS

2001 •

Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception

The Jewish Reception of Muhammad. EBR 2022 20.64-Journal of Traumatic Stress

Examining Insomnia During Intensive Treatment for Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Does it Improve and Does it Predict Treatment Outcomes?2020 •

Diabetes & Metabolism

Impact à 1 an d’une supplémentation multivitaminique post sleeve gastrectomie2017 •

BMC Medical Imaging

Clinical value of resting cardiac dual-energy CT in patients suspected of coronary artery disease2022 •

International Journal of Infectious Diseases

Characteristics of paradoxical tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and its influence on tuberculosis treatment outcomes in persons living with HIV2020 •

Joel Robinson

Joel Robinson