(De)Securitising Technological Innovation:

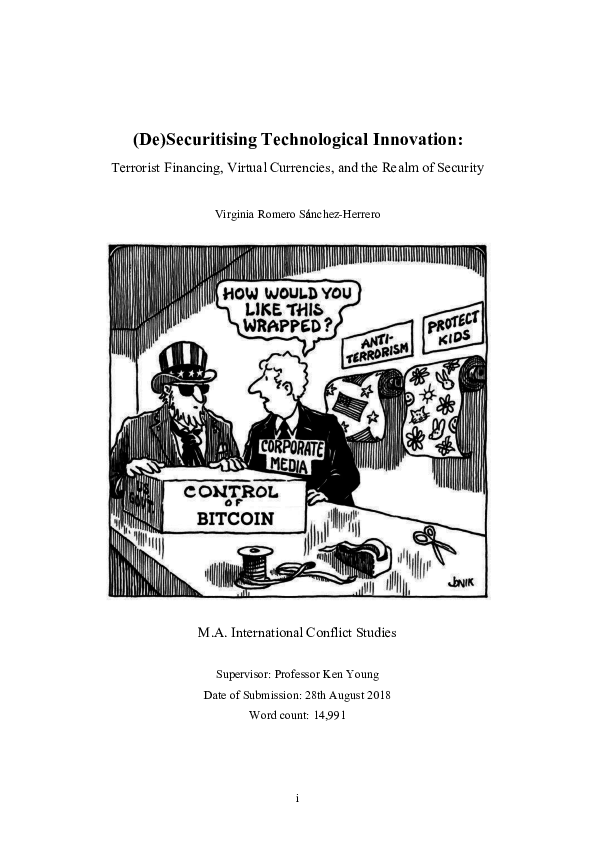

Terrorist Financing, Virtual Currencies, and the Realm of Security

Virginia Romero Sánchez-Herrero

M.A. International Conflict Studies

Supervisor: Professor Ken Young

Date of Submission: 28th August 2018

Word count: 14,991

i

�Abstract

A perceived risk in terrorist use and adoption of virtual currencies over the past few years has

driven the widespread notion that this financial innovation represents a threat to security. This

dissertation addresses this issue, examining the security implications associated to the rise of

this technology. It argues that the risks of terrorist exploitation are in fact limited, these being

primarily confined to their sporadic and ad hoc use as opposed to their adoption as a

sustained financing method. Moreover, it contends that a number of practices have ultimately

led to the ‘securitisation’ of this issue, or its framing in the logic of security and emergency,

justifying for increased state control over virtual currencies. The dissertation first presents an

overview of this question to subsequently sketch out a theoretical framework based on a

critical approach to security. It then considers patterns and methods of terrorist financing to

help situate virtual currencies in this context, arguing that some of the alleged benefits

offered by this technology are limited. In consequently considering the case of ISIL, it

determines that the organisation’s current financing needs are best served by their established

methods and not virtual currencies. The final section then returns to the question of security,

showing that a number of practices have resulted in the gradual securitisation of this

technology, and advocating for its de-securitisation, or its negotiation in the political realm

and not one defined by the logic of emergency.

ii

�Table of Contents

Abstract……………………………………………………………………….…….……..ii

Declaration………....………………………………………………………….….…….....iv

List of Abbreviations…………………………………………………………..………......v

1. Introduction………..…………………..……………………………….…….......1

2. Security as Practice.…..………………………………..………………..….........9

3. The Financing of Terrorism and Virtual Currencies.………....….………..…15

4. Case Study: The Financing of ISIL…….……………………..…..…….…...…26

5. Critical Security and Virtual Currencies….………………………….…..........33

6. Conclusion…..…………….…….…………...……………………………...……38

References………………………………………………...……………………...............40

iii

�Declaration

This dissertation is the sole work of the author, and has not been accepted in any previous

application for a degree; all quotations and sources of information have been acknowledged.

I confirm that my research [ ] did or did not [x] require ethical approval.

I confirm that all research records (e.g. interview data and consent records) will be held

securely for the required period of time and then destroyed in accordance with College

guidelines.

(The department will assume responsibility for this if you send your research records to the

Senior Programme Officer) [ ] Yes

Signed _______Virginia Romero_____________ Date ___28/08/2018________

iv

�List of abbreviations

AML

Anti-Money Laundering

CSS

Critical Security Studies

CTF

Counter-terrorist Financing

DLT

Distributed Ledger Technology

ETA

Basque Homeland and Freedom

FATF

Financial Action Task Force

IRA

Irish Republican Army

ISIL

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

KYC

Know-Your-Customer

PLO

Palestine Liberation Organisation

RMB

Renminbi (Chinese Yuan)

RUF

Revolutionary United Front

TATP

Triacetone Peroxide

UNSC

United Nations Security Council

VC

Virtual Currency

v

�1. Introduction

On September 15, 2008, as financial services firm Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, the

reality of a global financial crisis unparalleled since the 1930s’ Great Depression began to

crystallise. Mere months later, in November 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto’s whitepaper Bitcoin: A

Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System first appeared online. Echoing a growing loss of faith in

the international financial and banking system, Nakamoto outlines the need for a network

able to process electronic payments without financial institutions acting as ‘trusted third

parties’ (2008:1). As its proposed alternative, it details a secure electronic payment system

based on cryptographic principles rather than trust, one relying upon a peer-to-peer computer

network validating and executing transactions in a tamper-proof manner (Bruhl, 2017:6).

Nakamoto effectively devises a framework to facilitate instant payments, enabling parties to

transact directly without the need for institutional intermediaries to validate transactions,

whereof the currency employed constitutes a virtual representation of value.

Since its inception in January 2009, Bitcoin, like many other successive virtual

currencies (VCs) developed on its open source code, has attracted a growing global interest.

While the current total VC market capitalisation is estimated at approximately $255 billion as

of June 2018, the price of Bitcoin has soared, increasing by almost 6,000% over the past 5

years (Yahoo! Finance, 2018). Like Bitcoin, the value of VCs resides in their acceptance by

people as common mediums of exchange and, despite remaining far from extensively

adopted, these have been sanctioned by increasing numbers of enterprises and businesses,

speaking to their merits and applications. Among such benefits, proponents contend, are the

speed of international transfer, degree of anonymity, and their characteristically decentralised

nature. In utilising VCs, parties can transact privately, quickly, and cheaply with

independence from financial institutions, allowing for the monetisation of goods and services

online, the inexpensive transfer of funds across borders, and the prevention of corruption and

fraud (Brito and Castillo, 2013).

Yet, whilst the benefits offered by VCs appear manifold, their purported risks have

increasingly attracted worldwide attention. Concerns are numerous, and range from fears that

VCs provide common criminals with opportunities for financial criminal activity, to their

attractiveness for cybercriminals and drug dealers alike. In fact, as the UK’s HM Treasury

contends in a 2017 report, it is commonly accepted that such risks are high, particularly

1

�because of the role of virtual currencies ‘in directly enabling cyber-dependent crime’ (Jones,

2018:44). Nonetheless, perhaps the most compelling of the alleged risks associated with VCs

is their appeal for terrorist and extremist organisations across the globe (Carlisle, 2017).

Because of their benefits (relative anonymity, speed, independence from the established

international financial system…), a common concern is their potential exploitation for

terrorist financing purposes. On this matter, several influential organisations argue that the

use of VCs by terrorist organisations ‘should be’ considered first in the ‘hierarchy of financial

crime threats’ (Centre for a New American Security, 2017), given that these ‘present

governments with new national security challenges and terrorist groups, criminals, and rogue

states with opportunities’ (Council on Foreign Relations, 2018). In many ways, VCs have

undoubtedly become firmly placed within what may be simply called the realm of ‘security’.

Although this narrative provides a convincing account of the potential for terrorist

exploitation based on the alleged benefits of this technology, the extent of such risks remains

unascertained. Clearly, any emerging and disruptive technological innovation is likely to

bring about certain challenges and opportunities for a number of actors. Yet, should the

international community consider VCs, as some suggest, the ‘next generation of terrorist

financing’? (Brill and Keene, 2014:7). Do VCs facilitate the funding of terrorism? Will they

in the future? Should VCs constitute a ‘security priority’ within this context? In short, this

dissertation scrutinises the security implications associated to their rise, specifically within

the context of terrorist financing.

1.2

The Literature

The question of terrorist use of VCs for financing purposes has been discussed in the

literature to a certain degree, but determining the extent of the threat has thus far proven far

from straightforward. Although there exists a near-consensus that VCs possess unequivocal

appeal for terrorist actors and common criminals alike, their associated risks have only been

tentatively examined and, because of the emerging nature of this phenomenon, the literature

considering the relationship between VCs and terrorist financing remains somewhat scarce.

In what follows, this review examines the existing body of scholarly literature on the

broad subject of terrorist financing. It first presents an overview on the state of knowledge

regarding how terrorist organisations finance their activities and operations, to subsequently

2

�consider

academic

enquiries

into

the

international

community’s

corresponding

countermeasures. It then appraises existing research on the topic of VCs and the threats these

pose from a terrorist financing/counter-terrorist financing perspective.

a. Terrorist Financing

With a few notable exceptions, the subject of terrorist financing remained largely unexplored

in the pre-9/11 era. In exploring the cases of the PLO, the IRA, and the Red Brigades, Adams

(1986) presents terrorist financing as resulting from numerous activities, from kidnapping for

ransom, narcotics and smuggling, to government funding, charitable donations, and complex

commercial enterprises. Similarly, ensuing studies point to the funding of terrorist

organisations by non-state actors such as diaspora and refugee communities in the post-Cold

War context (Byman et al., 2001). Terrorist financing is thus understood as a complex

enterprise whereby organisations raise, move, store, and use funds through a range of

activities.

In the wake of the September 11 attacks, the research into how terrorist actors finance

their activities significantly expanded, mirroring a concurrent burgeoning interest in the

broader critical terrorism studies field (Ridley, 2012). Numerous post-9/11 studies build on

the knowledge concerning the sources and methods of terrorist financing. Schneider (2004)

and Olsen (2007) reveal the role of the shadow and underground economies in financially

supporting Islamic terrorism, while Ehrenfeld (2005) emphasises the importance of charitable

donations, and the narcotics trade, for the financing of Al-Qaeda, Hezbollah, and Hamas. In

examining how the movement of funds is managed, the exploitation of the hawala system of

informal payments has been linked to an inexpensive, fast, and traceless transfer of funds (ElQorchi,.2002; McDowel,.2002; Muller,.2006; Vaccani,.2009). Alternative fund dispersion

methods such as ‘starbust’, the depositing of smaller amounts into multiple bank accounts, is

also associated to organisations like Al-Qaeda (Schneider,.2004).

An issue often debated is the extent to which terrorist groups exploit the formal

international financial system. Some emphasise that terrorist financing relies on the regulated

financial system and that its methods largely resemble those of money laundering

(Masciandaro, 2004). Others illustrate the adjustment of financing methods in the post-9/11

era to avoid detection by authorities (Bierstaker and Eckert, 2007). Consequently, scholars

increasingly highlight the importance of further analysing terrorist use of both formal and

3

�informal banking systems (Raphaelli, 2003; Abuza, 2003; Acharia, 2009), arguing that

understanding the economics of different sources of funding for organisations is essential, as

these activities largely involve the regular economy (Wittig, 2011). There is therefore a

growing sense that terrorist financing ought to be considered in the context of groups’

individual principles (Clarke, 2015), thereby meriting judgement on an independent basis

(Tupman,.2009). In a theory-driven analysis, Freeman (2011) offers a useful taxonomy of the

sources of terrorist funding, classifying these into 1) state sponsorship, 2) illegal activity, 3)

legal activity, and 4) popular support.

In recent years, studies point to the relatively inexpensive nature of contemporary

terrorism (Walters, 2003; Lutz and Lutz, 2011; Neumann, 2017), a paradigm deriving from

the low manufacturing costs of widely-used improvised explosive devices (Ridley, 2012),

and the low operational costs of vehicle-ramming attacks. This idea is challenged, however,

alluding to the costs of terrorism far from being limited to those of attacks, often drawing a

useful distinction between operational and organisational expenses (Acharya, 2009). As

analyses indicate, organisational costs incurred to support such infrastructures include

training, salaries, promotion efforts, equipment, and materials (Ayers, 2002; Waszak, 2004;

Levitt, 2007; Freeman, 2011). From a theoretical perspective, Vittori (2011) emphasises

terrorists’ resourcing capabilities as an indicator of operational ability and longevity; offering

a three-fold typology of assets: 1) money and other liquid assets, 2) tangible goods, and 3)

intangible goods like knowledge, training, and intelligence.

b. Counter-terrorist Financing

Paralleling the growing interest on terrorist financing, the global counter-terrorist financing

regime has increasingly become the subject of academic scrutiny. Some provide in-depth

historical accounts of these measures, from the emergence of the Financial Action Task Force

(FATF), to the International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism in

the years leading up to 9/11 (Lavalle, 2000; Winer, 2002; Kersten, 2002; Freeland, 2002).

Since these attacks, efforts have also focused on the expansion and reform of this regime

within the context of the war on terror (Jayasuriya, 2002; Levi, 2010; Rider, 2015),

particularly the US role (Walters, 2003; Zagaris, 2013), the EU’s (Unger et al., 2014; Bures,

2015), and continuities and ruptures with past approaches (Navias, 2002).

4

�Beyond these descriptive contributions, debate has centred on the merits, successes,

and failures of the global counter-terrorist financing regime. Some contend that it provides a

normative framework instilling the system with international and regional legitimacy

(Beekarry, 2013); and that the Customer Due Diligence and know-your-customer (KYC)

measures at its heart are fundamental for effectively targeting terrorist financing (Freeland,

2002). Others conclude that such countermeasures constitute the most successful initiatives in

the fight against terrorism (Clunan,.2005), largely considering these essential in preventing

their funding (Levit,.2007;.2011), what is perceived as critical as tackling their operations

(Abuza, 2003). Despite these endorsements, some argue that the counter-terrorist financing

regime is inherently flawed and ineffective due to its merging with incompatible anti-money

laundering (AML) policies (Kersten,.2002; Zagaris,.2002; Roberge,.2007; Sinha, 2013).

Besides, the lack of enforcement of these global standards (Waszak,.2004; Winer, 2008);

their inconsistent implementation (Pieth,.Thelesklaf.and..Ivory,.2009); the absence of

cooperation among individual states (Acharya,.2009); definitional disagreements concerning

terrorist financing itself (Rider, 2004; Alzubairi,.2017); its widespread misunderstanding

(Goede, 2012; Neumann, 2017) as well as organisations’ bureaucratic politics and internal

tensions (Heng and McDonagh,/2008;/Rider, 2013;/Tsingou, 2013), have all been singled out

as issues for concern.

Overall, consensus on the steps required moving forward has not been reached. While

some propose the regime’s reform and expansion (Weschler, 2001; Raphaelli, 2003; Walters,

2003; Rider, 2004), or the more stringent enforcement of existing laws and international

cooperation (Allen, 2003; Myers, 2005; Winer, 2008), others question its raison d’être,

advocating for initiatives grounded upon a greater understanding of terrorist financing itself.

These approaches contend that because terrorist organisations largely conduct their funding

operations outside of the established international financial system (Freeman, 2012;

Neumann, 2017), the current regime proves misdirected. Said lack of consensus perhaps

derives from the disjointed rubric employed in determining what counts as successes and

failures in the context of these initiatives, what has ultimately hindered research in this area.

c. Terrorist Financing & Virtual Currencies

The literature on terrorist and counter-terrorist financing suggests that understanding the

particularities behind the financing of diverse groups is essential for the formulation of

5

�effective responses - including those encompassing the regulation of VCs - to adequately

address such concerns.

However, while there exists a near-consensus that VCs possess an unequivocal appeal

for terrorist organisations, risks have only been tentatively examined. Although general texts

to VCs provide relevant insights (Lee,.2015; Gatto and Broeker,.2015), most studies

superficially consider this dimension within the broader context of terrorist use of virtual

spaces (Keene, 2011; Ashley, 2012; Irwin et al., 2014; Tierney, 2018); or that of the criminal

exploitation of VCs more generally (Trautman, 2014; Carlisle, 2017). Moreover, those

centring on VCs and their alleged risks and regulations tend to adopt an anti-money

laundering perspective, with a lack of direct reference to the question of terrorist financing

(Singh, 2015; Vandezande, 2017). Although a few studies do focus on this specific issue,

findings are informed by speculative analyses of VCs themselves and the incentives and

mechanisms they allegedly provide for illicit financing (Brill and Keene, 2014); sporadic

instances of their exploitation by scattered terrorist cells and individuals (Irwin and Millad,

2016); or future-oriented hypothesis as to advocate for stringent regulations (Goldman et al.,

2017).

In this respect, studies predominantly neglect the process of terrorist financing itself

and particularities across organisations, as well as the broader literature on the subject.

Therefore, existing scholarly research considering exploitation of VCs for the financing of

terrorism cannot conclusively determine whether or not VCs ought to be considered a priority

for those leading the international fight against the financing of terrorism.

1.3

Research Design, Approach, and Structure

One could determine the extent to which VCs constitute a security threat by gathering data on

terrorist use of VCs over a substantial period of time, as to conduct a large statistical analysis

to determine the probability of increased adoption by extremist groups. However, given the

significantly opaque nature of both terrorist financing and VCs, obtaining a statistically

significant and reliable dataset proves challenging. Moreover, this quantitative approach

would fail to adequately or fully address the paramount notion of ‘security’, leaving aside

fundamental conceptual and theoretical questions.

Instead, by building on the Critical Security Studies (CSS) scholarship, its

understanding of security, and its theorisation of securitisation, this dissertation puts forward

6

�a critical interpretation of the security implications associated to the rise of VCs in the

context of terrorist financing. In so doing, it problematises accounts that conceptualise VCs

as the ‘next generation of terrorist financing’ and a ‘national security threat’. It posits,

instead, that their association to the realm of security is one that has granted this issue

‘heightened priority’ thereby urging ‘the use of decisive action’ (Hansen,.2006:35); whilst

obfuscating their legitimate uses and applications, and misrepresenting terrorist financing

risks as imminent and crystallised rather than contained. Consequently, in line with the CSS

field, the notion of security is hereafter understood as far from merely ‘the absence of threats

to acquired values’ (Wolfers,.1952:485), but as ‘the product of social and political practices’

(Aradau et al.,.2015:1). The approach herein adopted may thus be classified as poststructuralist, being based upon the assumption that policies and ‘security practices’ are

dependent upon ‘representations of the threat, country, security problem, or crisis they seek to

address’ (Hansen, 2006:6). This theoretical framework offers the basis through which the rise

of VCs and their association to the realm of security may be examined.

Furthermore, although it is commonly argued that there exists an inextricable link

between VCs and terrorist financing, this dissertation contends that such fears and concerns

are, for the most part, unjustified. Specifically, in seeking to dissociate VCs from terrorist

financing, this dissertation adopts an integrated twofold qualitative approach that

encompasses both a theoretical and an empirical analysis. From a theoretical standpoint, it

develops a framework that examines, on the one hand, notions of security ‘as practice’ and,

on the other, the process of terrorist financing. Conversely, from an empirical perspective, it

employs a case study approach to examine patterns and methods of financing associated to

the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). Following Flyvbjerg

(2006:.228), this case study is used as a representative example to produce generalisations

that reflect on the issue of potential terrorist adoption of VCs more widely. While scrutinising

ISIL patterns of financing, the analysis specifically considers the benefits of VC adoption

against those of existing methods. It determines there is no clear incentive or benefit for the

organisation to adopt VCs in lieu of its existing financing methods to, for instance, buy

materials, transfer funds quickly between cells and individual members, to store funds, or to

avoid detection by authorities - as it is commonly feared.

In its approach, this dissertation offers a contribution to three main research areas.

First, to the interest into VCs as an emerging subject of scholarly attention. Second, to the

long-established CSS scholarship by incorporating this issue into its broad research agenda.

7

�Third, to the academic field concerning terrorist financing through its examination of VCs

within this context and the case of ISIL.

Structure

Consequently, in what follows, this dissertation suggests the dissociation of VCs from

inherent terrorist financing risks whilst advocating for their de-securitisation. The following

section, chapter two, considers notions of security, securitisation, and approaches to critical

security analysis as to build a theoretical and conceptual framework to examine the

emergence of VCs within the realm of security. Chapter three subsequently reflects upon the

issue of terrorist financing whilst paying attention, in particular, to methods associated to the

financing of terrorism, situating VCs in this context by drawing on the latter’s defining

characteristics. Chapter four empirically reflects upon terrorist financing through the case of

ISIL, and some of the group’s patterns and methods of financing as to show the limited

desirability of adoption. The fifth chapter then draws from previous sections to examine the

security implications analogous to the rise of VCs, arguing that these have been subjected to a

broad process of securitisation while advocating for their de-securitisation. This dissertation

concludes by addressing any foreseeable limitations and identifying opportunities for further

research.

8

�2. Security as Practice

Scholarly enquiries seeking to evaluate the security implications associated to the rise of

virtual currencies ought to be grounded upon a firm conceptual and theoretical understanding

of the notion of security itself. What is security? What makes certain developments (and not

others) ‘security issues’? How do these, as Balzacq (2011) puts it, ‘emerge and dissolve’?

To answer these questions, this section draws upon the CSS field to examine notions

of security and securitisation, and approaches in critical security. In so doing, it provides a

framework that understands security as practice, or a set of interrelated processes through

which the (in)security of situations is created within public consciousness. In short, the

theoretical rationale that underpins the rest of this dissertation is delineated, representing the

basis through which VCs’ association to the realm of security may be examined.

2.1 Evolving Understandings of Security

For much of the twentieth century, the discipline of International Relations widely

understood the notion of ‘security’ strictly in relation to the military-political milieu.

According to this traditional understanding, ‘security is about survival’ and, in particular, that

of the military defence of the modern state (Buzan,.Waever, and de Wilde, 1998:21). There

exist a number of traditionalist and state-centric approaches to security1, each holding

different assumptions on state behaviour and the factors taking primacy in explaining policy

choices. Nonetheless, in considering security issues, these share a focus on the state as their

basic unit of analysis, and on military power as the key independent variable accounting for

‘security-ness’. Reinforced through the Cold War’s ‘military and nuclear obsessions’ these

are commonly referred to as ‘narrow’ approaches to the field, being restricted to ‘the threat or

actual use of force between political actors’ (Buzan,.1998:2-3).

Following an impulse towards the broadening of the security agenda in the 1980s by

the Copenhagen School, the traditional meaning of security has become contested and reinterpreted. Barry Buzan’s seminal work People, States, and Fear (1983) presents security as

multi-levelled, incorporating the individual and the international system as further levels of

security analysis beyond that of the state. It also proposes an understanding of security

extending into the political, economic, societal, and environmental sectors (Buzan, 1983 and

1

For a discussion of such traditionalist IR approaches see Smith (2005:27-62).

9

�1991), convincingly making the case for a wider field. Indeed, by the 1990s, the end of the

Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union gave impetus to this project for the widening

of the security agenda. Such geopolitical developments brought into question the adequacy of

traditional approaches to explain and make sense of the new emerging security landscape in

Europe and elsewhere. Amid these developments, the security field experienced a shift away

from a strict focus on state preservation to a wider concern with human well-being and thus

an emphasis upon the security of the individual, giving rise to distinct ‘human security’

approaches (Hayden,.2004:40).

For those in the Copenhagen School, the shift away from the state as the sole focus of

analysis was similarly noticeable. Recognising the need to extend referent objects of security

beyond that of the state for a ‘fully meaningful’, ‘multi-sectoral approach to security’ (Buzan,

1998:8), Waever et al. (1993) propose a dualist reconceptualisation of security, adding the

notion of ‘societal security’ to that of the state. Societal security is therein defined as ‘the

ability of a society to persist in its essential character under changing conditions and possible

or actual threats’ (Ibid: 23) and, Waever (1995) explains, it is theoretically underpinned by

the notion of identity and not sovereignty. In practice, in adopting this concept, the security

concerns and dynamics encapsulated by a range of actors and institutions outside the realm of

‘the state’ and its formal representatives can be illuminated. Most importantly, in

understanding security through both the dynamics of the security of the state and that of

society more widely, this perspective refuses a conceptualisation of security as a defined

concept possessing ‘independent, stable, context-free meaning’ (Ibid:3). Instead, from the

perspective of the Copenhagen School and others within the broader CSS field, security

represents a process, one whereby certain developments are moved from an area of regular

politics into one of exception. In making this move, state representatives and societal actors

take ‘politics beyond the established rules of the game’, framing issues ‘either as a special

kind of politics or as above politics’ (Buzan, Waever and De Wilde, 1998:23). In this respect,

central to critical security approaches is a shared understanding that ‘security threats and

insecurities are not simply objects to be studied or problems to be solved, but the product of

social and political practices’ (Aradau et al.,.2015:1).

Building on the work of the Copenhagen School, contemporary understandings of

security within the CSS field are concerned with a focus on security as a set of practices,

seeking to determine how these work, as well as their social and political implications. In

moving away from security in narrowly-defined terms, CSS approaches have become one of

10

�the predominant ways in which the contemporary scholarship makes sense of security

phenomena. This understanding of security, as a process and a set of social and political

practices, is the one herein adopted.

2.2 Securitisation & De-Securitisation: How Security Issues Emerge and Dissolve

In understanding security as a process instead of a given or defined value characterising

situations, CSS approaches share a focus in seeking to make sense of the ways in which

security issues emerge and dissolve within public consciousness. First coined by Ole Waever,

the process whereby security issues emerge is known as ‘securitisation’. In essence,

securitisation theory postulates that ‘no issue is essentially a menace’ (Balzacq, 2011:1), but

that issues become security problems through a set of interrelated practices. As such,

securitisation is constitutive and not just representative of threat phenomena, this process

being an indivisible element through which issues come to be placed within the realm of

security and outside the domain of regular political negotiation. Conversely, through

processes of de-securitisation, issues are brought from the security sphere to (often, but not

exclusively) the political milieu (politicisation), where these can be contested in the public

domain (Waever, 2011:472). It is commonly accepted that processes of politicisation are

more desirable than those of securitisation (Waever,.1995), given that whilst the latter tend to

render the use of exceptional measures justifiable (if successful), the former bring the issues

in question back to the realm of democratic politics (Aradau,.2004). Within the democratic

political realm, such issues of concern and importance to human security can be negotiated

by societal actors without the need to invoke the notion of security and thus the logic of

emergency.

Yet, how do processes of securitisation take place? What are the mechanisms

whereby issues become securitised? Balzacq (2011) identifies two main variants of

securitisation theory. The first regards securitisation as a ‘speech act’ and underpins the

Copenhagen School’s approach. According to this first (deemed linguistic) variant,

securitisation occurs when an issue is presented as posing an existential threat to a designated

referent object (oftentimes the state, its government, territory, or society), thereby enabling an

agent to treat the issue by extraordinary means (Buzan, Waever and de Wilde, 1998: 21,26).

In this view, a securitisation move is successful if the speech act constructing some

11

�development as a threat is accepted by the audience towards which it is targeted. Through this

approach, securitising actors, referent objects, and discursive securitisation moves and their

ramifications are identified and emphasised as to ascertain whether given social phenomena

represent instances of securitisation.

The second variant of securitisation theory is, for Balzacq (2011:1), one which

recognises that ‘whilst discursive practices are important in explaining’ how security

problems originate, ‘many develop with little if any discursive design’. In many ways, this

second approach represents an expanded version of the original postulation of securitisation

theory and the one most prevalent in contemporary critical security studies. According to this

second perspective, securitisation is understood ‘as practice in the broadest sense’, including

‘discourses, ideas, power relationships, bodies of knowledge, techniques of government,

technologies, and the linkages between them’ through which the ‘securityness of situations is

created’ (Aradau et al., 2015:3). Arguably, in offering a holistic perspective of processes of

securitisation through their multiple manifestations and elements beyond discursive practices,

this second variant of securitisation theory effectively presents an understanding of the

various practices through which securitising agents, contexts, and structures carry out and/or

facilitate securitisation moves.

Thus far, this chapter has provided a broad conceptualisation of security ‘as practice’

rooted upon the field of CSS. In so doing, it has argued that security issues emerge and

dissolve through a process known as ‘securitisation’, one whereby developments are taken

outside the domain of regular political negotiation and within one of ‘exception’. Moreover,

it has argued that securisation ought to be understood as the result of sets of practices

including but not confined to ‘speech acts’. In this light, I suggest, borrowing from the

outlined perspectives when appropriate allows for a broader understanding of given instances

of securitisation without the need to expressly favour one variant over the other. The

chapter’s following and final section discusses two relevant approaches to securitisation

theory within critical security analyses.

2.3 Critical Security Analysis

For CSS scholars interested in understanding processes of securitisation, there exist two

fundamental layers of analysis. The first concerns the identification of the issue referred to as

12

�a security problem: one that should be both the subject of public attention or debate, as well

as a target for activities relating to public opinion, legal, or political action (Balzacq,

2011:32). In the case of this dissertation, the issue under consideration is the threat allegedly

posed by virtual currencies in the context of terrorist financing, an issue that satisfies both

outlined criteria for identification. This is the case given 1) the sustained and increasing

interest in the subject on the part of the media, academics, government representatives, and

society more widely; and 2) the legislative and policy efforts towards which VCs have been

subjected.

The second aspect of security analysis entails determining ‘how to make sense’ of the

issue under consideration, one closely related to research design. In other words, it represents

the task of appropriately identifying the kinds of levels of analysis and tools used to

investigate the issue at hand, in such a way as to illuminate the various facets involved in the

process of securitisation being considered. Two approaches to critical security analysis are

detailed below, each of which can be drawn upon to varying degrees as to analyse how VCs

have become placed within the realm of security.

Thierry Balzacq (2011) proposes an approach to securitisation theory that builds upon

that originally developed by the Copenhagen School, and one divided into three main levels

of analysis. The first level focuses on ‘agents’, or the actors and relations involved in the

structuring of a given security situation. These include both ‘securitising’ actors, as well as

the wider audience towards which securitising moves are directed (2011:35). The second

level refers to ‘acts’, or those discursive and non-discursive practices underpinning the

process of securitisation being scrutinised. These include any practices, tools, or policies that

generate or are generated through the process of securitisation (Ibid:36). The third and final

level of analysis is concerned with ‘context’, or the social and historical circumstances that

help illuminate the given instance of securitisation (Ibid:37). As Balzacq explains, this

approach offers analysts the ability to capture processes of securitisation by focusing on

distinct sources, each of which can offer complementary explanations. In the context of VCs

and the finance of terrorism, this approach can help illuminate a number of aspects. Namely,

what is portrayed as being threatened by this technological development; the entities and

practices responsible for the association of VCs to the realm of security; and, finally, the

context wherein these processes have developed.

A second relevant approach meriting attention is that found in Aradau et al., one to be

13

�employed within the context of analyses concerning the ‘dangerousness of matter’; or how

threatening non-human things come to be placed within the security agenda (2015:.58). This

approach to critical security analysis is based on three ‘operationalisations’ of securitisation

theory: dispositifs, performativity, and agency. For Aradau et al., a Foucauldian dispositif can

be used as a device for ‘analysing how strategies of security governance are constituted, often

in an unintended manner, through changing connections between seemingly unconnected

elements’ (Ibid:64). In empirical analyses such as an examination of VCs, the dispositif can

be used to understand how the binding of VCs to discursive tropes leads to the emergence of

a defined security strategy comprised of various disparate relations. The second

operationalisation is that of ‘performativity’, which can be employed as to specifically

analyse how given ‘threats, objects and subjects’ are given ‘a seemingly fixed character’

through repetitions and reiterations (Ibid:70). In using performativity as a device, the distance

between the discourse surrounding VCs and VCs themselves can be refused, thereby

accounting for their co-constitutive relation (Callon, 2006:24, cited in Ibid). The final

operationalisation is that of ‘agency’, takes the form of ‘distributed’ or ‘entangled’, and used

to understand how the actions and capabilities of human and non-human things reflect upon

the constitution of a security strategy. In other words, Aradau et al. (2015:75) explain, the

difference between distributed and entangled agency can ‘be captured through the difference

between ‘follow the object’ and ‘follow the event’. Thus, whilst distributed agency is

concerned with tracing how the characteristics of particular things reflect on a wider security

strategy, entangled agency examines how a particular event can illustrate the ways in which a

set of elements converge into a wider security ensemble.

Ultimately, the two outlined approaches can be employed within critical security

analyses of VCs, as these point to disparate yet complementary elements that can help

explain and account for the securitisation of this technology. This chapter sought to provide a

conceptual and theoretical interpretation of security, by uncovering evolving understandings

of this notion. It advocated for a broad conceptualisation of security as practice, and thus as a

series of interrelated processes that define the ‘security-ness’ of given phenomena. Moreover,

it put forth an account of securitisation theory as a lense through which to make sense of the

processes whereby security issues emerge and dissolve. In exploring critical approaches to

security analysis, it emphasised relevant tools which can subsequently be drawn upon as to

examine how VCs have emerged within the realm of security.

14

�3. The Financing of Terrorism and Virtual Currencies

Having provided a theoretical and conceptual framework through which to examine the

security implications associated to the rise of VCs, this chapter moves away from

securitisation theory to discuss the central issue of terrorist financing. It begins by

considering patterns in the financing of terrorism to subsequently discuss criteria for

evaluating the desirability of specific methods. It then explores VCs and their potential for

exploitation as one of such methods by detailing how their defining characteristics allow for

terrorist financing exploitation.

In sum, this chapter offers an account of the association of VCs to terrorist financing

grounded upon 1) the process of terrorist financing itself, and 2) the defining attributes that

characterise VCs. In so doing, it delineates some of the main concerns that are often alluded

to when presenting this technological development as a threat to security.

3.1 Patterns of Terrorist Financing

The FATF describes terrorist financing as a range of activities encompassing the various

ways through which terrorist organisations2 ‘raise, move and use funds’ (2008:5). This

understanding proves useful, recognising that terrorist financing is not limited to the sources

through which organisations are funded, an aspect perhaps most frequently debated in the

literature. Instead, it is useful to ask a number of general questions: Why do terrorist

organisations need funds? How are these funds used by terrorist actors? What means and

methods do they employ in the context of terrorist financing?

A terrorist group requires a number of resources to not only fund its activities, but to

endure and thrive as an organisation. Financial resources are essential for the success and

resilience of terrorist groups, particularly at the point of inception, when these are needed to

help attract and sustain support, and to develop significant material capabilities (Adams,

1986). In general terms, funds are required to promote the group’s ideology through

propaganda efforts or social activities, to sustain militants and their relatives, to finance travel

expenses and the recruitment and training of new members, to acquire weapons and safe

2

The critical terrorism studies literature remains divided on a conceptual understanding of this phenomenon

(Crenshaw, 2000). Terrorism is herein simply understood as a strategy - a tactic used to obtain political gain

from the use or the threat of the use of violence primarily against civilian populations (Hoffman, 2006;

Richards, 2014).

15

�houses, as well as for carrying out operations (FATF,.2008:7). Although the requirements of

specific terrorist groups and actors vary according to their principles and internal

characteristics, those considered essential for survival can be divided into three main

categories: money, tangible resources, and intangible resources (Vittori,.2011:13-23). Money

and liquid assets are needed to acquire tangible and intangible goods, as well as a means to

store wealth. Tangible resources represent material goods possessing a monetary value,

encompassing both equipment and varied infrastructures. Intangible resources (such as

expertise, an ideological narrative, a command and control structure, training, and

intelligence) are also necessary to ensure survival (Ibid). As mentioned, these will differ

according to actors’ organisational structures, goals, and characteristics (Clarke,.2015).

Despite diverse resourcing requirements, the financing needs of terrorist organisations

can similarly be broadly divided into two main areas, according to where the spending

necessity derives from. The first refers to organisational expenses, the funds required to

maintain and manage the terrorist organisation’s infrastructure itself, regardless of its size;

while the second concerns operational expenses, the costs associated with conducting attacks

and operations (Acharya,.2009:24-28). According to the FATF, the costs of financially

maintaining a terrorist network are ‘the most significant drain on resources’ (2008:8), an

observation supported by the existing literature. While the costs of maintaining the

infrastructure of a typical terrorist organisation represent 90% of its financial needs, those

associated to the operational, day-to-day expenses incurred in planning and executing attacks

generally represent a mere 10% of total financing costs (Brisard,.2002:7; Ehrenfeld,.2005;

Acharya, 2009:24). In fact, there exists a near consensus regarding the notion that the costs

associated with launching terrorist attacks are in themselves relatively small, particularly

when considering the fact that large, active, terrorist organisations like al-Qaeda, Hezbollah,

or the Taliban ‘have budgets that can range up to hundreds of millions of dollars per year’

(Freeman, 2012:9). For instance, highly-coordinated, strategic attacks such as the World

Trade Center 1993 bombings, those of Bali in 2002, or of Madrid in 2004, have been

estimated to have cost between $10,000 and $50,000 each (Passas,.2007:31); while recent

home-grown terrorist attacks, such as those inspired by ISIL around the world since 2014,

may have required as little as $100 (Levitt, 2017:4). These figures help illustrate the

relatively low costs terrorist actors incur when undertaking operations.

Notwithstanding these low operational costs, resourcing capabilities can indeed

significantly impact upon their ability to support a wider group infrastructure (if applicable)

16

�and, to a certain extent, the ability to successfully carry out attacks. Although most attacks

will require small amounts of money, direct cost estimates often fail to account for overheads

(Acharya,.2009:32). On this point, the impact of resourcing upon a terrorist organisation’s

ability to carry out attacks is heavily dependent on the group itself. For example, a terrorist

network such as Al-Qaeda, comprised of several interrelated cells globally, might suffer in its

ability to carry out spectacular and co-ordinated operations if unable to fund its recruitment,

planning, training, and procurement efforts (FATF,.2008:8). Conversely, a lone wolf attacker

or isolated cell carrying out an inspired attack on behalf of an organisation without its direct

support will ostensibly be less reliant upon financial resources to carry out an isolated, often

inexpensive operation. This further speaks to the importance of considering terrorist

financing activities within the context of specific groups and actors, given the diversity and

complexity of terrorist actors themselves and their varying financing needs.

3.2 Terrorist Financing Methods & Criteria for Desirability

Beyond general patterns of terrorist financing, it is important to consider some of the factors

influencing the ways in which terrorist actors are financed. The advantages and disadvantages

offered by given financing methods are, of course, dependent on the specific terrorist actor or

organisation, whose chosen methods will ostensibly seek to maximise value3. As mentioned,

methods of terrorist financing can be subdivided into three areas: the raising of funds, the

moving of funds, and the use of funds. In broad terms, chosen methods in these key areas

may account for questions of 1) volume, 2) reliability, 3) security, 4) speed, 5) cost, and 6)

simplicity (Freeman,.2012; Freeman and Ruehsen, 2013). Two main categories of terrorist

financing methods are briefly considered below in relation to the above-mentioned

desirability criteria.

3.2.1. Raising funds

The ways in which terrorist actors raise funds vary greatly across organisations, and given

groups or cells often secure a wide-ranging portfolio of sources of funding. These can also

change over time, as terrorist actors will tend to adapt their sourcing activities as a result of

geopolitical or demographic developments, as well as counterterrorism strategies (Ranstorp

3

The issue of whether ‘terrorism works’ is contested. However, it is generally accepted that terrorist actors act

rationally and strategically in seeking to achieve their goals. For discussions on these debates, see Crenshaw,

1987 and 2000; Kydd and Walter, 2006; Abrahms, 2011; and Ganor, 2015, among others.

17

�and Normak, 2015).

When considering sources of finance, terrorist actors will seek to secure as many

funds as possible, what makes sources that provide a larger volume of funds more desirable

(Freeman, 2012:10). For instance, in exploiting Sierra Leone’s rich diamond resources, the

RUF derived an estimated $25 - $125 million in revenues associated to the diamond trade in

the year 2000 alone (Napoleoni,.2005:187). Sources of finance that are reliable (predictable

and consistent) are also favoured by terrorist organisations, who normally require a steady

flow of funds as to underwrite their diverse operations (Ibid; Vittori,.2011:23). State

sponsorship represents one of such reliable sources for Hezbollah, an organisation estimated

to annually receive $200-$350 million from Iran, or the Taliban, historically chiefly funded

by Pakistan and Saudi Arabia (Clarke, 2015:.78,119). Terrorist actors are also inclined

towards sources that are secure, or those that carry less risks in drawing the unwanted

attention of authorities, given the clandestine nature of their operations (Freeman and

Ruehsen, 2013: 6). In this regard, numerous terrorist groups have historically profited from

the revenues of legitimate businesses, which offer security advantages as states are limited in

their possible countermeasures. For example, whilst the sources of financing for the Basque

ethno-nationalist group ETA included kidnappings and extortion, the organisation also had a

number of legitimate enterprises, such as a network of legal pubs and restaurants serving as

meeting places for sympathisers (Buesa and Baumert,.2013:320). Another important question

is that of simplicity: sources that ‘require fewer specialised skills, that require as little effort

as possible’ and ‘that have simpler processes’ are more attractive than more complex ones

(Freeman, 2012:12). One of such sources is popular support, an essential component of the

financing of terrorist organisations of the likes of the IRA, the PLO or the Tamil Tigers who,

for instance, relied upon the global Tamil diaspora as a major source of the organisation's

fundraising efforts (Clarke,.2015:51).

3.2.2. Moving and storing funds

For terrorist actors to effectively carry out their activities, funds must also be moved from the

originating source to wherever these are needed as, ‘without targeted transfers, funds are

useless’ (Hess cited in Acharya, 2009:70). In the context of methods of financing, funds are

moved prior to being used and value transferred in two main ways: as a means to store value,

or as a means to procure tangible and intangible goods (Vittori,.2011). This transfer and

storing of value normally involves the formal international financial system (such as bank

18

�transfers into disguised accounts), the physical movement of money (like cash couriers), the

international trade system, or alternative remittance systems like the hawala network (FATF,

2008: 21-24). Similarly to the sources of finance, the methods whereby terrorist actors move

funds are highly dependant upon the internal characteristics and requirements of specific

groups and organisations, and these will often vary according to the particular purpose why

money is being moved and stored4.

In determining how terrorist actors choose to transfer and store value, the desirability

of possible methods may also be determined with reference to the outlined criteria. Regarding

volume, those methods that enable terrorist groups and individuals to move and store ‘more

money with each transaction mak[e] it easier for terrorist groups to fund an operation’

(Freeman and Ruehsen, 2013:6). For example, while the formal banking system can

theoretically allow for infinite funds to be transferred between accounts, the transfer of large

quantities in a single transaction is likely to alert financial authorities. A further aspect is that

of reliability, or the extent to which different methods ensure funds are transferred and stored

‘accurately and completely’ without presenting substantial risks, such as government seizure,

or theft (Ibid). The hawala network is considered an efficient and cheap method of terrorist

financing, and one linked to a number of Islamist groups, such as the Lakshar-e-Taiba in

Pakistan (Kambere et al., 2012:84) or the Taliban in Afghanistan (Reese,.2012:106).

Concerning speed, methods enabling funds to be moved quickly and efficiently are more

desirable than those that do not. On this point, while hawala and bank transfers enable the fast

transfer of funds, couriers will require time, particularly if moving cash across multiple

jurisdictions (Freeman and Ruehsen, 2013:7). Finally, with reference to simplicity,

‘everything being equal, terrorists would prefer methods that require the fewer number of

steps, the lowest level of technology, and the least amount of skill’ (Ibid).

Ultimately, because specific methods of financing carry both advantages and disadvantages

(‘trade-offs’), terrorist actors prioritise different criteria when choosing among the various

possible methods to raise, move, store, and use funds (Freeman,.2012). In turn, these

decisions are influenced by the different contexts in which these activities are carried out. In

examining methods of terrorist financing from the perspective of terrorist actors, some of the

factors influencing the ways in which they choose to finance their activities and operations

have been illuminated. Drawing on their defining characteristics, this chapter’s subsequent

4

For an in-depth discussion of such methods, see Acharya, 2009:70-79.

19

�and final section provides an account of VCs5 as a potential method of terrorist financing.

3.3 Virtual Currencies as Terrorist Financing Method

Also known as cryptocurrencies, decentralised VCs associated to terrorist financing

risks may be defined as ‘distributed, open-source, math-based peer-to-peer virtual currencies

that have no central administrating authority, and no central monitoring or oversight’ (FATF,

2014:5). In simpler terms, VCs represent a form of digital asset that may be used as a

medium of exchange to undertake financial transactions, like a digital form of cash. Through

the use of public-key cryptographic principles, these allow for the verification of transactions

without a need for financial intermediaries, enabling parties to transact directly. Public key

cryptographic proof ‘ensures that all computers in the network have a constantly updated and

verified record of all transactions ... which prevents double-spending and fraud’, thus

removing the need for third-party verification (Brito and Castillo, 2013:5). This public,

chronological, and permanent record of transactions is called the ledger - one which depends

on users’ processing power for the updating and verification of transactions, as opposed to

any given central authority. In turn, the process whereby such users establish network

consensus is known as ‘mining’ - one which involves the solving of mathematical problems

as to verify the transactions on the ledger and for which certain users (‘miners’) are rewarded

in VC units. The ledger effectively maintains the VC ecosystem, representing a tamper-proof,

shared database distributed across servers and geographic locations, making this

decentralised network secure. The technology that underpins VCs is hence known as

distributed ledger technology (DLT), given that a majority of existing cryptocurrencies have

derived from Bitcoin’s open source ledger, the Blockchain, comprised of blocks of inalterable

transactions.

Decentralised VCs are digitally traded in online exchanges by users, who determine

their value by means of supply and demand, what has led to their extensive use as a means of

both investment and speculation, despite their high volatility (CFTC,.2018). Their practical

applications are numerous, since these can facilitate fast and inexpensive payments, monetise

tangible and intangible goods online, and store and exchange value when traded for

5

VCs can themselves be divided into two main categories: centralised and decentralised. The former are used in

contained environments (such as virtual gaming) and centrally-issued by a single authority; whilst the latter can

be converted into fiat (government-backed) currency, and possess no central authority. Decentralised VCs (or

cryptocurrencies) are those associated to terrorist financing risks.

20

�government-issued currency or other virtual currencies (FATF, 2014:9). Moreover, VCs can

help extend financial services to unbanked populations in developing countries with limited

financial infrastructures (Carlisle,.2017:8); and, as Hook (2017) notes, DLT presents

opportunities for the fight against financial crime, since this technology can be harnessed by

financial institutions in order to trace the movement of funds, commodities, and securities,

thereby holding potential for decreasing fraudulent transactions and the laundering of the

proceeds of crime.

Despite the above-mentioned benefits and legitimate applications, the exploitation of

VCs for illicit purposes (and cybercrime in particular) is well-documented6, with cases like

those of Silk Road7 and the WannaCry8 ransomware attacks attracting worldwide media

attention. Notwithstanding, the criminal adoption of VCs begs consideration of two

fundamental questions. First, what features characterising VCs make them attractive for the

raising, moving, and storing of funds in the context of financial criminal activity (terrorist or

otherwise)? And, second, while criminals have been shown to exploit VCs at a large scale,

why is this not the case for terrorist actors?

3.3.1. Features Associated to Terrorist Financing Risks

Anonymity/Pseudonymity

A key aspect often cited in detailing the terrorist financing risks associated to VCs is that of

anonymity. Because user identities are concealed behind digital addresses (‘wallets’)

composed of alphanumeric keys, due diligence and know-your-customer procedures

underlying AML/CTF initiatives are difficult to implement in the context of these

transactions (FATF,.2014). This concern is encapsulated in Brill and Keene (2014:13), who

rightly suggest that if you were ‘a terrorist, a money launderer or a criminal’, you

would certainly want a system that did not require you to prove your identity and to have

that validated identity tied to all of your transactions. In fact, you would like a system

that did not require you to identify yourself at all, or to provide any information about

6

The illicit exploitation of VCs for criminal purposes has received substantial attention. See, for example,

Trautman,.2014 and Carlisle,.2017.

7

An online black market operating on the dark web until 2013 which allowed users to purchase and sell illegal

drugs anonymously, whereof the method of payment was Bitcoin (Trautman,.2014:91-100).

8

Those responsible demanded payment in VC, allowing them to procure £108,000 in Bitcoin ransom

(Gibbs,.2017).

21

�yourself.

Now, whilst VCs indeed offer varying degrees of privacy and anonymity, it should be noted

that these are better characterised as ‘pseudonymous’, rather than fully anonymous financial

instruments. As noted by Chambers-Jones and Hillman (2014:156), it is not VCs such as

Bitcoin that are pseudonymous, but rather, their transactions, which nonetheless remain

publicly available (and therefore, traceable) on the ledger. Users in VC networks are

identifiable by their digital wallets’ alphanumeric keys and, although it is possible to ‘create a

potentially infinite number of pseudonymous identities’, the ledger’s public nature represents

a ‘mitigant by offering a complete transaction trail’ (Carlisle, 2017:9) through which the

movement of funds can be followed. In this regard, AML in VCs ‘has to deal with imperfect

knowledge of identities, but may exploit perfect knowledge of all transactions’ (Moser cited

in ibid).

Notwithstanding the pseudonymous nature of a majority of VCs, there exist

techniques available that indeed provide for greater anonymity to those wishing to

deliberately conceal illicit financing activities. Relevant examples are anonymity-enhancing

alternative VCs such as Monero (‘drug dealer’s cryptocurrency of choice’), or the use of

‘tumblers’ - employed as a means of ‘combining multiple transactions, hiding the amount of

each transaction and obscuring the recipient of funds’ (Goldman et al., 2017). However, their

use requires ‘watertight discipline’ and highly-technical expertise - a faux-pas being

sufficient to allow law enforcement to ‘unmask’ illicit users seeking to obscure the trail of

funds (Prisco,.2018). This limited anonymity is considered one of the key reasons why

terrorists have not exploited the technology at any significant scale (Carlisle,.2017).

Decentralisation

The second key area for concern refers to the decentralised nature of VCs, or the lack of a

central monitoring or administrative authority overseeing the network and whom to hold

accountable. As the FATF contends, this not only prevents law enforcement from targeting

one central entity for ‘investigative or asset seizure purposes’ (2015:32), but also makes

wallets and accounts within VC networks difficult to control, oversee, or censor by financial

authorities. Such lack of oversight has led some to dub the VC domain as a sort of ‘wild

west’; one dominated by widespread deregulation, criminality, and speculation (Singh,.2015).

It is important to note, however, that there are few, if any, truly decentralised and

22

�convertible VC environments, as these networks are themselves often accessed via

intermediaries such as VC exchanges and wallet providers. As Carlisle (2017:14) has noted,

the bulk of VC transactions ‘still pass through exchanges for conversion into fiat currency’

and vice versa, as these networks are difficult to access without third-party assistance, thus

far from representing fully contained environments. Such intermediaries establish links

between the formal financial and banking system and VC networks, illustrating their lack of

decentralisation in practice. In fact, the FATF’s VC risk assessment (2015:6) recommends the

targeting of those ‘points of intersection that provide gateways to the regulated financial

system’ as a main focus of AML/CTF initiatives, given that only convertible VCs present

risks in the context of money laundering and terrorist financing. VC exchanges can hence

provide assistance and support to law enforcement as these generally have ‘access to more

information about transacting parties than their [VC] addresses’ (Martin Christopher,

2014:23). Moreover, these exchanges have increasingly been brought under financial

regulatory frameworks, thereby ensuring the reporting of suspicious transactions (Manheim

et al., 2017).

Fast and Inexpensive Transactions

A third feature associated to financial crime risks is the ability of VCs to enable a fast and

inexpensive transfer of funds. Because of their peer-to-peer nature and ‘near real-time

transaction settlement’, these theoretically offer users a quick and cost-efficient method to

transfer funds across borders (Carlisle, 2017:13). These characteristics make of VCs an

attractive opportunity to illicit actors presumably interested in settling transactions as quickly

and cheaply as possible, as to reduce costs and the chances of blocking and interception (Brill

and Keene, 2014:13).

However, despite the promises of DLT in allowing for fast and inexpensive

transactions, the increased adoption of VCs has sometimes led to concurrent decreases in

transaction speeds and cost-effectiveness. This is particularly true of the Bitcoin network,

whereof scalability problems have been described as a limiting factor in its utility as a

reliable financial instrument (Goldman et al., 2017:15). In December 2017, coinciding with

dramatic increases in Bitcoin interest worldwide and skyrocketing price valuation, the

average Bitcoin transaction confirmation took 78 minutes, this raising as high as 1,188

minutes when the network was particularly busy (Browne,.2017). As per transaction fees,

because users normally access VC networks through exchanges, the average virtual currency

23

�transaction cost was, as of that date, an estimated $28 (ibid).

3.3.2. Limited Adoption by Terrorist Actors

Although there is substantial evidence concerning the criminal exploitation of this technology

for numerous types of illicit activity, this is not the case for terrorist financing. Reporting on

terrorist use of VCs ‘remains limited and largely anecdotal’, there being ‘no concrete

indication in the public record that terrorists are using cryptocurrencies as a payment tool

with regularity’ (Carlisle, 2017:18-19). Thus, whilst terrorists have been known to

sporadically use VCs to primarily solicit donations online, VC adoption by these actors

substantially lags behind that of cybercriminals (RAND, 2015:19). What accounts, then, for

these discrepancies?

Although terrorist actors will often resort to criminal enterprises in order to acquire

funds to finance their activities9, there exist fundamental differences between common crime

and terrorism. For terrorists, crime represents a means to an end, that of achieving some

political, ideological and/or religious goal, while criminals’ overriding purpose is the

accumulation of money or valuable resources (Hutchison and O’Malley, 2007:1098). In the

context of terrorist financing ‘the movement of funds occurs before the intended crime has

been committed’, whilst laundering the proceeds of illicit activity happens once the crime has

taken place (Martin Christopher, 2014:5). This distinction partially accounts for why terrorist

actors have not exploited VCs at the same rate as other criminals, given the fact that the

process of terrorist financing does not involve, by definition, the use and movement of illicit

funds. As Neumann (2017) explains, because ‘terrorists can draw on legitimate sources of

income’, fighting terrorist financing ‘is harder than fighting money laundering or organised

crime’. Then, perhaps one of the most significant reasons accounting for disparity in adoption

is that terrorist actors have not needed to do so - as other means of value transfer ‘have served

their needs reliably’ (Goldman et al., 2017:28). This, coupled with the inherent technical

complexity of VCs compared to other methods of finance, and their limited anonymity and

decentralisation, can help account for their (to date) very limited adoption by terrorist actors.

This chapter has presented an examination of VCs as a possible method of terrorist

9

This link is commonly referred to as the crime-terror nexus. For accounts on this convergence see Dishman,

2005; Hutchinson and O’Malley,.2007; and Makarenko,.2012.

24

�financing rooted upon an understanding of this process and the defining features

characterising this technology. It first examined general patterns of terrorist financing, as well

as criteria for determining the desirability of given financing methods for terrorist actors. It

then considered VCs as one of such methods by drawing on the key features of

anonymity/pseudonymity, decentralisation, and fast and inexpensive transaction settlements.

Finally, it accounted for their limited adoption by terrorist actors vis-a-vis that by other

criminals.

Ultimately, as noted by the FATF, ‘the adaptability and opportunism shown by

terrorist organisations suggests that all the methods that exist to move money around the

globe are to some extent at risk’ (2008:4). However, like other methods, VCs offer legitimate

users numerous benefits and applications, and their characterisation as primarily a tool for

financial criminal activity proves misleading10. Yet, given this terrorist adaptability, the

prospect of increased or even widespread adoption for terrorist financing purposes cannot be

completely ruled out (Carlisle, 2017; Goldman et al., 2017), particularly as the technology

underpinning VCs continues to evolve. Therefore, in order to ascertain prospects of increased

adoption, and bearing in mind the importance of considering terrorist financing within the

context of specific actors, the next chapter discusses these with reference to a particular case,

that of ISIL.

10

According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, criminal activity accounts for ‘approximately 10 percent of

on-chain bitcoin transactions, down from a high of 90 percent in 2013’ (Wilmoth,.2018).

25

�4. Case Study: The Financing of ISIL

This section examines prospective VC adoption by terrorist actors through the case of ISIL. It

first considers the group’s composition and current patterns of financing, showing that the

advantages offered by VCs are fairly limited in these contexts. It subsequently moves on to

consider two main methods of ISIL’s financing, hawala and cash couriers, discussing their

benefits as to compare them against those offered by a prospective VC adoption. To do so, it

draws from the desirability criteria outlined in the previous chapter, considering questions of

volume, reliability, security, speed, cost, and simplicity.

In short, in employing ISIL as a case study, this chapter shows that the desirability of

VC exploitation is limited, particularly when compared against that offered by the group’s

established methods of finance. Therefore, while VCs may be used sporadically by terrorist

actors to fundraise online or to purchase materials on the dark web, they are unlikely to

become a method of ongoing finance for terrorist actors. This suggests that, notwithstanding

substantial future developments surrounding this technology and the conduct of terrorism

itself, the risks of widespread terrorist exploitation of VCs remain confined to their isolated

and sporadic use.

4.1 Current Patterns and VC adoption

At the height of its power in 2014, ISIL was considered a ‘proto-state’ by many observers: it

administered a large territory of 10 million people extending across Iraq and Syria, collected

taxes, provided social services, minted its own currency, and even controlled agricultural

resources, providing sustenance to the local population (Martin and Solomon, 2017; Levallois

et al., 2017). Its standing as a territory-controlling terrorist organisation enabled it to secure

substantial sources of revenue. The most significant of these being taxes and fees imposed on

the population it ruled over, the control of oil-producing fields, and the proceeds derived from

lootings, confiscations, and fines (Heissner et al.,.2017). By the end of 2015, as a proto-state,

the group was estimated to generate in excess of $2.4 billion per year, making it the richest

terrorist organisation in modern history (Martin and Solomon,.2017:34).

Despite its defeat in Iraq and most of Syria by late 2017, ISIL ‘continue[s] to pose a

significant and evolving threat around the world’ (UNSC, 2018:1). According to the UN,

26

�ISIL is primarily ‘now organised as a global network, with a flat hierarchy and less

operational control over its affiliates’ (ibid:2). This has effectively resulted in a gradual shift

from its stated focus on the project of ‘building and expanding’ its self-proclaimed Islamic

caliphate, to that of coordinating external operations through local cells in neighbouring

countries, encouraging followers to organise attacks wherever they may reside

(Levallois.et.al,.2017:16).

Therefore, although no longer in control of substantial swaths of territory and

resources, the group persists in three main forms as a terrorist actor: as the group’s core

remaining in Syria and Iraq; as affiliated cells and branches in numerous countries; and in the

form of its worldwide support base. First, the ISIL core is composed of the group’s militants

whom, after losing its territorial caliphate, continue to fight as insurgents in the region under

the authority of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (Ensor,.2018). The core of the group remains

distributed among the two countries, with as many as 30,000 militants still operating mostly

in covert cells or hiding in sympathetic communities (Lederer,.2018). Second, in the form of

its global network of affiliated cells, transnationally linking foreign-based ISIL supporters

and ‘fighters located in conflict zones and elsewhere’ (UNSC,.2018:6). These linkages

increase the capabilities and skills of affiliated networks and individuals whom, whilst

operating with reduced backing from the group, continue to receive its endorsement. Third,

ISIL continues to enjoy the ideological support of committed sympathisers. These are

individuals (lone actors) or groups of individuals who carry out inspired attacks on ISIL’s

behalf without its prior knowledge or support.

ISIL’s said composition has a number of implications for the group’s current patterns

of financing. Since the fall of its caliphate, the core has slowly become a ‘less reliable

financial backer of its affiliates and operatives’ (Levitt,.2018), what has led these to

increasingly diversify their income as to become financially independent (UNSC, 2018:4).

According to the UN, affiliated cells across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia are said to rely

on sources of finance such as kidnappings, theft, extortion, human trafficking, and the illicit

drug trade. Moreover, despite having lost 90% of its revenues since 2015, the core continues

to move funds (primarily derived from extortion and checkpoint controls) through networks

and facilitators across the Middle East by using hawala systems and cash couriers. The group

is also said to be infiltrating legitimate regional businesses through the use of fronts,

ostensibly clean individuals able to access the formal financial sector (ibid). With regards to

operations undertaken by affiliated members and sympathisers, current and historical trends

27

�point to the continuation of low-cost, medium and small-sized terrorist attacks by the group

(EU,.2017), favoured instead of spectacular plots which may take months or years to mount

(Callimachi,.2016). In fact, in a 2015 publication, the group explained: ‘with less attacks in

the West being group attacks and increasing amounts of lone-wolf attacks, it will be more