Gatekeepers Inside Out

SUNG HUI KIM*

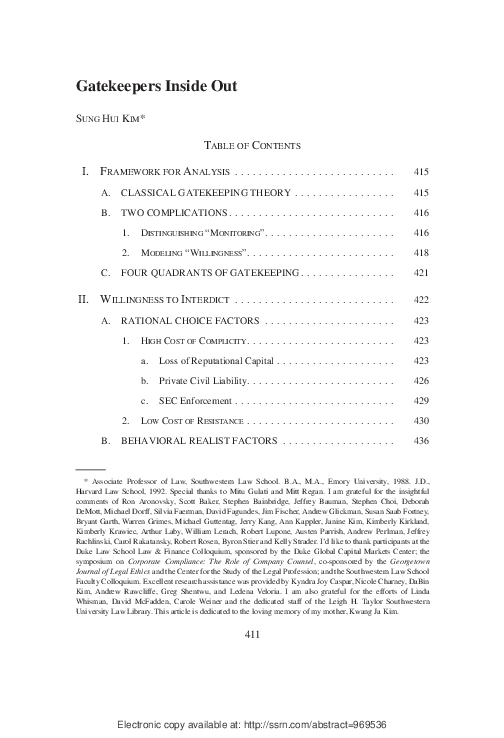

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

415

A.

CLASSICAL GATEKEEPING THEORY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

415

B.

TWO COMPLICATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

416

1.

DISTINGUISHING “MONITORING”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

416

2.

MODELING “WILLINGNESS”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

418

FOUR QUADRANTS OF GATEKEEPING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

421

II. WILLINGNESS TO INTERDICT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

422

C.

A.

RATIONAL CHOICE FACTORS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

423

1.

HIGH COST OF COMPLICITY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

423

a.

Loss of Reputational Capital . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

423

b.

Private Civil Liability. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

426

c.

SEC Enforcement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

429

LOW COST OF RESISTANCE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

430

BEHAVIORAL REALIST FACTORS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

436

2.

B.

* Associate Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School. B.A., M.A., Emory University, 1988. J.D.,

Harvard Law School, 1992. Special thanks to Mitu Gulati and Mitt Regan. I am grateful for the insightful

comments of Ron Aronovsky, Scott Baker, Stephen Bainbridge, Jeffrey Bauman, Stephen Choi, Deborah

DeMott, Michael Dorff, Silvia Faerman, David Fagundes, Jim Fischer, Andrew Glickman, Susan Saab Fortney,

Bryant Garth, Warren Grimes, Michael Guttentag, Jerry Kang, Ann Kappler, Janine Kim, Kimberly Kirkland,

Kimberly Krawiec, Arthur Laby, William Lerach, Robert Lupone, Austen Parrish, Andrew Perlman, Jeffrey

Rachlinski, Carol Rakatansky, Robert Rosen, Byron Stier and Kelly Strader. I’d like to thank participants at the

Duke Law School Law & Finance Colloquium, sponsored by the Duke Global Capital Markets Center; the

symposium on Corporate Compliance: The Role of Company Counsel, co-sponsored by the Georgetown

Journal of Legal Ethics and the Center for the Study of the Legal Profession; and the Southwestern Law School

Faculty Colloquium. Excellent research assistance was provided by Kyndra Joy Caspar, Nicole Charney, DaBin

Kim, Andrew Rawcliffe, Greg Shentwu, and Ledena Veloria. I am also grateful for the efforts of Linda

Whisman, David McFadden, Carole Weiner and the dedicated staff of the Leigh H. Taylor Southwestern

University Law Library. This article is dedicated to the loving memory of my mother, Kwang Ja Kim.

411

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=969536

�412

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS

[Vol. 21:411

1.

MERE EMPLOYEE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

437

2.

TEAM PLAYER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

439

3.

FAITHFUL AGENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

441

III. WILLINGNESS TO MONITOR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

446

IV. CAPACITY TO MONITOR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

448

A.

FORMAL COMMUNICATION CHANNELS . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

448

B.

INFORMAL COMMUNICATION CHANNELS . . . . . . . . . . . .

453

C.

OBJECTION: KNOWING THE LAW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

455

V. CAPACITY TO INTERDICT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

457

VI. CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

460

“If we want companies to fuse high performance with high integrity, the place

to begin—and to be most effective—is inside the company itself. Outside

regulators and gatekeepers can never be as potent and preventative as internal

governance on the front lines from the CEO on down.”

Ben W. Heineman, Jr., former general counsel,

General Electric Company1

INTRODUCTION

On September 28, 2006, a visibly exhausted Ann Baskins stood before a

Congressional committee investigating the Hewlett Packard (“HP”) spying

scandal. Baskins, who had just resigned as general counsel, raised her right hand

and swore to tell the truth. Then, on the first question, she exercised her Fifth

Amendment privilege against self-incrimination.2 While Baskins sat mute

nearby, the former HP chairwoman Patricia Dunn and chief executive officer

Mark Hurd told the committee that Baskins was to blame for the spying fiasco.

They accused her of rendering bad legal advice and claimed that she knew about

and permitted the use of “pretexting”—using false pretenses to obtain certain

board members’ personal information from telephone companies.3

Baskins’s ordeal comes at a watershed moment for general counsel of public

1. Ben W. Heineman, Jr., Caught in the Middle, CORP. COUNS., Apr. 2007, at 84, 89 (arguing that inside

counsel do and must play the role of “guardian of the corporation’s integrity and reputation”).

2. Sue Reisinger, Saw No Evil, CORP. COUNS., Jan. 2007, at 68.

3. Id.

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=969536

�2008]

GATEKEEPERS INSIDE OUT

413

corporations. In a little more than a year, twelve general counsel have stepped

down amid allegations of options-backdating at their companies,4 with at least

one general counsel pleading guilty to criminal conspiracy.5 Not only have these

general counsel lost their jobs but some face civil or criminal indictment and

shareholder derivative actions that name them individually as defendants.6

Although it remains to be seen whether the general counsel under suspicion are

scapegoats or masterminds, the catalogue of scandals in the past year has

certainly soiled the public’s perception of inside counsel. These scandals have

lent support to the general consensus that inside lawyers are too “captured” to

exercise the independent judgment that is the hallmark of professionalism.7 In the

securities context, these scandals have cast doubt about inside counsel’s ability to

fulfill their role as “gatekeepers,” private intermediaries who can prevent harm to

the securities markets by disrupting the misconduct of their client representatives.8 John Coffee exemplifies the conventional wisdom:

While the outside attorney has been increasingly relegated to a specialist’s role

and is seldom sought for statesman-like advice, the in-house general counsel

seems even less suited to play a gatekeeping role . . . . [T]he in-house counsel is

less an independent professional–indeed he is far more exposed to pressure and

reprisals than even the outside audit partner.9

True, inside lawyers may well be “more exposed to pressure and reprisals”

than outside lawyers or outside auditors; however, this does not necessarily make

inside counsel less suited to the gatekeeping role than outside intermediaries. The

truth is much more complex. Inside counsel are superior to outside counsel in

crucial respects, and outside counsel face their own impediments, which differ in

kind (and not just degree) from those encountered on the inside. In short, the

4. D.M. Osborne, The Great Plague: Stock option backdating scandals have taken down a record number of

GCs, CORP. COUNS., Jan. 2007, 16.

5. See, e.g., Exit-of-the-Month Club, CORP. COUNS., Jan. 2007, at 17 (reporting Comverse Technology, Inc.’s

former general counsel’s guilty plea to criminal charges relating to an options manipulation scheme); Judith

Burns, Ex-Counsel At Comverse Settles Lawsuit, WALL ST. J., Jan. 11, 2007, at A11 (reporting settlement of SEC

civil lawsuit for $3 million); Jessie Seyfer, The SEC Land a Big One, CORP. COUNS., June 2007, at 16 (reporting

the SEC’s filing of civil fraud suit against former Apple Inc. general counsel for backdating stock options); Sue

Reisinger, Caught in Backdating’s Web, CORP. COUNS., Feb. 2008 (summarizing back-dating scandals

implicating general counsel).

6. Osborne, supra note 4, at 16.

7. See, e.g., Deborah A. DeMott, The Discrete Roles of General Counsel, 74 FORDHAM L. REV. 955, 967

(2005) [hereinafter DeMott, Discrete Roles] (noting that the “conventional skepticism” about in-house lawyers

“focuses on the exclusivity of their relationship with a single client [their employer]”).

8. This definition of “gatekeepers” is modified and adapted from that set forth in Reinier H. Kraakman,

Gatekeepers: The Anatomy of a Third-Party Enforcement Strategy, 2 J.L. ECON. & ORG. 53 (1986) [hereinafter

Kraakman, Gatekeepers] (describing “gatekeeper liability” as “liability imposed on private parties who are able

to disrupt misconduct by withholding their cooperation from wrongdoers”). See infra Part I.A. for a discussion

on Kraakman’s framework for gatekeeper liability.

9. JOHN C. COFFEE, JR., GATEKEEPERS: THE PROFESSIONS AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 195 (2006)

[hereinafter COFFEE, GATEKEEPERS].

�414

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS

[Vol. 21:411

difference between the gatekeeping efficacy of inside and outside counsel is

caricatured and exaggerated. Further, a careful comparison between inside and

outside counsel’s potential for gatekeeping reveals deeper insights into gatekeeping theory and its practical implementation. Or so I shall argue.

In Part I, I briefly summarize classical gatekeeping theory,10 introduced into

the legal literature in 1986 by Reinier Kraakman. Going beyond simple

restatement, I identify three key elements of a gatekeeper enforcement regime

and translate that theory into a set of tractable performance criteria (“Four

Quadrants of Gatekeeping”) by which we can measure the gatekeeping potential

of any professional. These criteria arise from two simple observations. First, in

order to be successful, gatekeepers must not only be willing to disrupt

misconduct but also be capable of doing so. Second, gatekeepers must not only

be prepared to interdict misconduct but also monitor to detect such happenings in

the first place. Intersecting these observations, we see that potential gatekeepers

can be evaluated by their: (1) willingness to interdict, (2) willingness to monitor,

(3) capacity to monitor, and (4) capacity to interdict.

In Parts II through V, I employ these criteria to elicit a textured, institutional

comparison between inside and outside lawyers as gatekeepers. In doing so, I

make a methodological intervention by using social psychology11 and sociology,

in addition to traditional rational choice theory, to analyze a more comprehensive

set of factors that influence lawyer behavior in the face of client wrongdoing. In

this way, this project is consistent with a call for behavioral realism,12 which has

recently gained traction within legal analysis. In my conclusion, I explore how

my new synthesis of gatekeeping theory and the insights gained from my analysis

suggest pathways for reform and, more broadly, call for an inquiry into some of

our long-held assumptions about gatekeeping.

10. By “classical” or “traditional” gatekeeping theory, I refer to a particular triad of articles authored by

Kraakman and Ronald Gilson in the mid-1980s. These are: Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8; Reinier H.

Kraakman, Corporate Liability Strategies and the Costs of Legal Controls, 93 YALE L.J. 857, 888-96 (1984)

[hereinafter Kraakman, Corporate Liability]; and Ronald J. Gilson & Reinier H. Kraakman, The Mechanisms of

Market Efficiency, 70 VA. L. REV. 549 (1984) [hereinafter Gilson & Kraakman, Market Efficiency]. Theoretical

contributions and clarifications have been made by Ronald J. Gilson, The Devolution of the Legal Profession: A

Demand Side Perspective, 49 MD. L. REV. 869 (1990) [hereinafter Gilson, Devolution]; COFFEE, GATEKEEPERS,

supra note 9; Stephen Choi, Market Lessons for Gatekeepers, 92 NW. U. L. REV. 916 (1998); Assaf Hamdani,

Gatekeeper Liability, 77 S. CAL. L. REV. 53 (2003); Frank Partnoy, Barbarians at the Gatekeepers?: A Proposal

for a Modified Strict Liability Regime, 79 WASH. U. L.Q. 491 (2001).

11. This article and prior work are also heavily influenced by scholars in the field of social cognition. Social

cognition is the intersection between the traditionally separate fields of social psychology and cognitive

psychology. For an overview of social cognition, see SUSAN T. FISKE AND SHELLEY E. TAYLOR, SOCIAL

COGNITION (McGraw-Hill, 2d ed. 1991).

12. See infra Part I.B.2.

�2008]

GATEKEEPERS INSIDE OUT

415

I. FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS

A. CLASSICAL GATEKEEPING THEORY

Reinier Kraakman described gatekeeper liability as a genre of third party

liability used by the government to “supplement efforts to deter primary

wrongdoers directly by enlisting their associates and market contacts as de facto

‘cops on the beat.’”13 These de facto cops are in fact “gatekeepers,” originally

defined as “private parties who are able to disrupt misconduct by withholding

their cooperation from wrongdoers.”14 A review of the gatekeeping literature

suggests that a gatekeeper enforcement regime must have at least three key

elements: (1) a gatekeeper—someone “who can and will prevent misconduct

reliably,”15 (2) a gate—some service which the wrongdoer needs to accomplish

his goal,16 and (3) a law enforcement mechanism—an enforceable duty—that

obligates private parties to take some action aimed at averting misconduct when

detected.17

In the capital markets context, gatekeeping scholars have traditionally

conceived the gatekeeper as an outside professional services firm which has a

contractual relationship with the primary enforcement target (the client). The

gate has traditionally been that firm’s specialized certification (e.g., legal opinion

from a law firm, audit letter from an accounting firm) needed to consummate the

client’s securities transactions. And the specific mechanism has traditionally been

the gatekeeper’s professional duty to withhold services when it finds that it

cannot vouch for the veracity of its client. Thus, by withholding the firm’s

certification, the gatekeeper warns the market and shuts the gate, effectively

foreclosing the issuer’s access to the capital markets.18

Under the original formulation, gatekeeper liability was “designed to enlist the

support of outside participants [of] the firm when controlling managers commit

offenses, that is, when the firm’s internal monitors have failed.”19 The logic

13. Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 53.

14. Id. (defining “gatekeeper liability” as “liability imposed on private parties who are able to disrupt

misconduct by withholding their cooperation from wrongdoers”); Gilson, Devolution, supra, note 10, at 883

(defining gatekeepers as “someone in a position to decline when his service will be misused”).

15. See Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 61 (“[G]atekeepers who can and will prevent misconduct

reliably, regardless of the preferences and market alternatives of wrongdoers.”).

16. Gilson, Devolution, supra note 10, at 883.

17. See Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 57 (“[A]n enforceable duty—that allows private parties to

avert misconduct when they detect it.”) (emphasis added).

18. COFFEE, GATEKEEPERS, supra note 9, at 2. Of course, if the client successfully shops for another

certification, the fraudulent transaction may close and the market may not be warned. See infra Part V

(discussing how gatekeepers may be circumvented by issuers).

19. Kraakman, Corporate Liability, supra note 10, at 890 (emphasis added). However, Kraakman

acknowledged the possiblity of using intra-firm monitors as gatekeepers. See Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra

note 8, at 69 (observing gatekeeper regimes that enlist intrafirm monitors, e.g., those that police disclosure for

pollution discharge permits and public issues of securities).

�416

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS

[Vol. 21:411

behind this preference for outsiders was that “in the usual case, [outsiders] likely

have less to gain and more to lose from firm delicts than inside managers.”20

Thus, the ideal gatekeeper would be an “outsider with a career and assets beyond

the firm,”21 such as auditors, investment bankers, securities analysts, securities

attorneys, and, as more recently posited, credit rating agencies.22

But theory has crashed into some inconvenient truths. The vivid failure of a

Big Five accounting firm, Arthur Andersen, to prevent the ongoing frauds of

Enron and WorldCom, raised the question whether outsiders, in fact, make

reliable gatekeepers. This is not to say that insiders had a better track record in

these particular fiascos; however, it no longer seems quixotic to reexamine our

basic assumptions about gatekeeping inside and out.

B. TWO COMPLICATIONS

Kraakman declared that a successful gatekeeping strategy requires gatekeepers

“who can and will prevent misconduct reliably, regardless of the preferences and

market alternatives of wrongdoers.”23 This simple sentence hides two complications worthy of close examination.

1. DISTINGUISHING “MONITORING”

First, focus on the word “prevent.” In order to prevent or interdict24 managerial

misconduct, it goes without saying that the gatekeeper must find out about it in

the first place. In other words, prevention presupposes that the gatekeeper

20. Kraakman, Corporate Liability, supra note 10, at 891.

21. Id.

22. The one prominent exception to the view that outsiders are the only appropriate gatekeeping candidates

is Gilson, Devolution, supra note 10, at 915 (arguing that, since the market power necessary for private

gatekeeping has moved in-house, so, too, must the gatekeeping function).

23. Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 61 (setting forth the third of four criteria used to evaluate a

gatekeeper enforcement strategy). The other three criteria are: serious misconduct that practicable penalties

cannot deter; missing or inadequate private gatekeeping incentives; and gatekeepers whom legal rules can

induce to detect misconduct at reasonable cost. Id. Offering a slightly different formulation, Ronald Gilson

notes that not only must there be a gatekeeper and a gate, but (1) the “gatekeeper must be able to detect with

some precision when his service will be misused,” and (2) “supply and demand conditions in the market for the

service that functions as a gate must support an enforcement regime: the gatekeeper must be willing to play that

role and consumers of that service must be willing to accept it.” Gilson, Devolution, supra note 10, at 883.

24. While I adopt Kraakman’s verb, “interdict,” to describe what is expected of the effective gatekeeper, I

intend to include any and all steps taken by the gatekeeper (including reporting information up-the-ladder to the

board) for the purpose of averting or thwarting misconduct, short of the revelation of client confidences outside

of the corporate client (which would implicate an alternative “whistleblower” enforcement regime). See

Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 56 (distinguishing the whistleblower enforcement strategy that would

“compel third parties to disclose misconduct directly to potential victims or enforcement officials”). While the

specific design of gatekeeping duties is beyond the scope of this article, one could imagine that a typology of

duty design, based on potential impact, would be illuminating.

�2008]

GATEKEEPERS INSIDE OUT

417

monitor to detect potential malfeasance.25

Granted, monitoring and interdiction cannot always be sharply distinguished

because they sit along a detection-to-response continuum.26 When a gatekeeper

has some reasonable suspicion (but not quite probable cause) about some

misbehavior, its further actions can be framed as either deeper monitoring or

incipient interdiction.27 That said, in many contexts, the distinction will be plain

and analytically useful.

There are at least two reasons why. First, by distinguishing these two attributes

of good gatekeepers, we can better sort among potential actors that can play that

role.28 After all, certain actors may be quite ready and willing to interdict but

have no ability to monitor, and vice versa. As I demonstrate below, even if

outside law firms will be more willing to interdict, inside counsel have an

overwhelming advantage in their ability to monitor.

Second, this distinction makes us mindful of how solutions intended to

incentivize the gatekeeper to interdict (e.g., harsh sanctions imposed on the

gatekeeper who has “knowledge” of client wrongdoing but nonetheless fails to

25. See Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 86 (suggesting that a gatekeeper should have “the capacity

to interdict misconduct with some reliability and the ability to detect it at a relatively low cost”) (emphasis

added).

26. Depending on the type of gatekeeper regime, the distinction between monitoring and interdiction may be

more or less material. As Kraakman notes, in one genre of gatekeeper regimes known as “bouncer” regimes, for

example, a tavernkeeper’s duty to exclude minors, the distinction between monitoring and interdiction may not

be material. The tavernkeeper merely has a duty to check ID and to refuse to serve alcohol for those who fail to

present the proper ID. Thus, the duty to monitor and interdict are highly focused, mechanical and fairly

coincident. See Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 79. “Bouncer” regimes are a subset of gatekeeper

regimes where misconduct is easily disrupted by revoking access to a particular good or service. By contrast, in

“chaperone” regimes, the gatekeeper can detect and disrupt misconduct in a more complex, longer-term (often

contractual) relationship with enforcement targets. Thus, more complex monitoring duties are appropriate for

chaperone regimes. See Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 63.

27. To understand why monitoring and interdiction cannot always be sharply distinguished, consider the

following three scenarios:

(1) Will the gatekeeper—even in the absence of red flags—voluntarily assume an active monitoring role to

keep apprised of ongoing facts or will she do the bare minimum and passively “see no evil, hear no evil”?

(2) If red flags appear, will the gatekeeper probe for further facts or will she look the other way?

(3) Finally, once the gatekeeper knows of actual or anticipated misconduct, will she interdict—either by

saying “no” to the wrongdoer, reporting misconduct up-the-ladder, or withholding the critical support from a

recalcitrant client?

The first question above clearly goes to the gatekeeper’s willingness to monitor. The last question clearly

relates to her willingness to interdict. The middle question lies somewhere in between; after red flags first appear

(and the gatekeeper’s “spider sense” starts to tingle) but before the gatekeeper definitively knows a law has been

broken. In this grey zone, a lawyer’s further actions can be framed as either deeper monitoring or incipient

interdiction. And in situations characterized by complexity and ambiguity, self-serving rationalizations of

unethical conduct are likely to take root. See infra note 46.

28. See, e.g., Arthur B. Laby, Differentiating Gatekeepers, 1 BROOK. J. CORP. FIN. & COM. L. 119, 120 (2006)

(criticizing the rational actor model for failing to distinguish among gatekeepers, “who are likely to respond

differently to incentives,” and proposing to evaluate “dependent” and “independent” gatekeepers from a

behavioral viewpoint).

�418

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS

[Vol. 21:411

interdict) may perversely disincentivize monitoring.29 A gatekeeper who potentially faces the hard decision of either losing one’s job (being fired for resisting

the wrongdoer) or losing one’s professional license (for failing to resist the

wrongdoer) will prefer to cloister herself within her office and hear no evil.

2. MODELING “WILLINGNESS”

Second, notice that Kraakman distinguished between “can” and “will.”

Although Kraakman did not make much of that distinction, I contend that

willingness and capacity are also independent attributes worthy of separate

analysis. This is so because certain actors may be very willing but quite unable,

and vice versa. As I argue below, outside law firms may arguably be more willing

to interdict misconduct but they may be deeply unable to do so, because they are

never quite aware of when it takes place.

Further, I want to make a methodological intervention in our understanding of

“willingness.” Gatekeeping theory has largely adopted “rational choice theory”

(“RCT”) or “expected utility theory” as its model of human behavior.30 RCT

presents an idealized model of decisionmaking built on the foundational

assumption that man is a rational maximizer of his expected utilities.31 As a

result, gatekeeping theory has focused almost exclusively on the expected gains

of a gatekeeper’s corruption or acquiescence (e.g., continued fees from wrongdoer) weighed against its expected costs (probability of detection multiplied by

sanctions levied, e.g., reputational harm, civil liability, incarceration). If we are

interested in measuring a lawyer’s willingness to monitor, to interdict—indeed to

do anything, including eating a ham sandwich—we should simply measure the

incentives she faces, in costs and benefits.

But in the 1990s, behavioral-law-and-economics scholars began challenging

RCT’s foundational assumption that people make outcome-maximizing decisions.32 Drawing on the “heuristics and biases” literature from cognitive

psychology and behavioral economics, they called for a more empirically

accurate model of human-decisionmaking.33 I am fully on board with the call for

29. See infra Part III.

30. See Russell B. Korobkin & Thomas S. Ulen, Law and Behavioral Science: Removing the Rationality

Assumption from Law and Economics, 88 CAL. L. REV. 1051, 1061-1066 (2000) (classifying and describing the

different versions of rational choice theory, including the “expected utility” version). Gatekeeping theory has

thus far relied heavily on RCT, and its descendants–finance theory and institutional economics. Herbert Simon

observes that institutional economics “retains the centrality of markets and exchanges. All phenomena are to be

explained by translating them into . . . market transactions based upon negotiated contracts.” H. A. SIMON,

MODELS OF MY LIFE, 26 (1991).

31. See, e.g., RICHARD A. POSNER, ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF LAW 2-6 (1st ed. 1973).

32. For a survey, see Donald C. Langevoort, Behavioral Theories of Judgment and Decision Making in Legal

Scholarship: A Literature Review, 51 VAND. L. REV. 1499 (1998).

33. See, e.g., BEHAVIORAL LAW AND ECONOMICS (Cass Sunstein ed., 2000); Korobkin & Ulen, supra note 30

(critiquing rational choice theory and advocating “law and behavioral science”).

�2008]

GATEKEEPERS INSIDE OUT

419

greater empirical accuracy in modeling decisionmaking, which in this context is

ethical decisionmaking.34 But behavioral law and economics, notwithstanding

protestations to the contrary, privileges “economics” and undervalues scientific

findings from other fields. In practice, behavioral law and economics seems to

identify a laundry list of heuristics and biases that deviate from perfect rationality,

which still remains the default assumption.

Accordingly, I am more interested in what has recently been called a

“behavioral realist” approach,35 which calls forth on the law to adopt the most

accurate model of human decisionmaking and behavior provided by the mind

sciences, or if it does not, to explain in transparent terms why not.36 This

approach does not privilege one branch of scientific knowledge, such as

economics, over another in word or deed. It can, for instance, easily encompass

important insights from modern social psychology: that the situation is a better

predictor of human behavior than an individual’s personal characteristics or

views.37 It is not shy to extend beyond heuristics and biases that compromise

rationality but to consider less apparent yet “pervasive, fundamental and arational

cognitive processes”38 that RCT, even with modifications, declines to consider.

In the context of lawyer gatekeeping, these powerful but subtler and, for the

most part, arational cognitive processes include alignment, obedience, and

conformity pressures that are automatically activated by specific situational

factors in the lawyer’s environment, such as the organizational setting and the

lawyer’s position in the organizational hierarchy.39 In “role” terms that I have

34. A good example of a behavioral-law-and-economics approach to ethical decisionmaking by lawyers is

Richard W. Painter, Lawyers’Rules, Auditors’Rules and the Psychology of Concealment, 84 MINN. L. REV. 1399

(2000) (using prospect theory to explain lawyers’ unethical actions to conceal fraud). See also Jeffrey J.

Rachlinski, Gains, Losses and the Psychology of Litigation, 70 S. CAL. L. REV. 113 (1996) for one of the earliest

applications of prospect theory to lawyers’ behavior (in the litigation context).

35. Jerry Kang & Mahzarin R. Banaji, Fair Measures: A Behavioral Realist Revision of “Affirmative

Action,” 94 CAL. L. REV. 1063, 1064-65 (2006) (describing “behavioral realism”). See Symposium on

Behavioral Realism, 94 CAL. L. REV. 45 et seq. (2006). Other scholars have similarly introduced different

nomenclatures. See, e.g., John Hanson & David Yosifon, The Situation: An Introduction to the Situational

Character, Critical Realism, Power Economics, and Deep Capture, 152 U. PA. L. REV. 129 (2003) (introducing

“critical realism”); Korobkin & Ulen, supra note 30 (advocating “law and behavioral science”).

36. See Kristin A. Lane, Jerry Kang, & Mahzarin R. Banaji, Implicit Social Cognition and the Law, 3 ANN.

REV. L. & SOC. SCI. 19.1, 19.14-19.15 (2007); Kang & Banaji, supra note 35, at 1065 (noting that behavioral

realism is not a set of “first-order normative commitments or policy preferences” but a second-order

commitment against hypocrisy and self-deception: “If science reveals that the law is failing to do so because it is

predicated on erroneous models of human behavior, then the law must transparently account for the gap instead

of ignoring its existence”).

37. See, e.g., Hanson & Yosifon, supra note 35 (introducing “situationism”); Sung Hui Kim, The Banality of

Fraud: Re-Situating the Inside Counsel as Gatekeeper, 74 FORDHAM L. REV. 983, 992-97 (2005). By

“situation,” I mean features in the person’s environment. For situational factors, see infra note 39.

38. Jerry Kang, Trojan Horses of Race, 118 HARV. L. REV. 1489, 1494 at n.21 (2005) (advocating a

“behavioral realist” approach to law, drawing on the traditions of legal realism and behavioral science).

39. Situational factors include, among others, the “physical setting, roles, rules, uniforms, symbols, and

group consensus.” See Kim, supra note 37, at 995.

�420

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS

[Vol. 21:411

described elsewhere and below,40 we should be mindful of the roles that outside

and inside counsel play as mere employee, team player, and faithful agent.

Further, numerous psychological and economics experiments reveal how we

automatically engage in biased and motivated reasoning to self-serving ends.41

Thus when the situation pits self-interest against one’s moral responsibilities, we

often fail to perceive that as a moment of ethical choice and instead rationalize

our self-interested behavior. That individuals often fail to classify situations as

“ethical” is consistent with sociological findings that law firm partners deny the

moral dimensions of their work,42 inside counsel report experiencing little ethical

conflict in their jobs,43 and experienced business managers do not frame

situations in moral terms.44

In sum, when thinking about “willingness,” we should not imagine a

gatekeeper experiencing an overt ethical dilemma, pondering the decision to

interdict. Instead, a more behaviorally realistic model understands the prevailing

psychological forces as akin to gravitational pulls–pervasive, powerful, and yet,

fundamentally invisible and unnoticed. This insight has two implications. First,

explicit moral commandments to be better gatekeepers without a concurrent shift

in the ethical norms of lawyering45 will have limited effect. Second, given our

robust ability to unconsciously and selectively process information in a selfinterested manner, especially in situations characterized by complexity and

40. See infra Part II.B.; Kim, supra note 37, at 1001-26.

41. Social psychologists refer to the mechanism by which self-interest (through the “self-serving bias” or

“egocentric bias”) is automatically processed by the human brain as “motivated reasoning,” the selective

information processing that has been identified and supported by the empirical literature. For a discussion on the

self-serving bias, motivated reasoning and the dual processing model of cognition, see Kim, supra note 37, at

1026-34. See also Ziva Kunda, The Case for Motivated Reasoning, 108 PSYCHOL. BULL. 480 (1990) for a review

of evidence that supports the existence of motivated reasoning.

42. See, e.g., Mark Suchman, Working Without A Net: The Sociology of Legal Ethics in Corporate Litigation,

67 FORDHAM L. REV. 837, 844-45 (1998) (noting that large firm associates “readily acknowledged the moral

dimensions of their work, but often collapsed these into pragmatic concerns” and that large firm “partners . . .

tended to deny the moral dimensions of their work entirely, and to reduce most issues to either ethical rules or

pragmatic strategies”); Kimberly Kirkland, Ethics in Large Law Firms: The Principle of Pragmatism, 632 U.

MEM. L. REV. 632, 726 (concluding that “Partners do not see moral questions . . . because partners do not

measure their conduct against internal or fixed principles; their habit of mind is to glean expectations, to read

situations, to collapse the distinction between appearance and substance, and to equate etiquette with ethics”).

43. Hugh P. Gunz & Sally P. Gunz, The Lawyer’s Response to Organizational Professional Conflict: An

Empirical Study of the Ethical Decision Making of In-House Counsel, 39 AM. BUS. L.J. 241, 250, 264 (2002)

(noting that the degree of “organizational-professional conflict” in studies of inside counsel is low). In the Gunz

study, “organizational-professional conflict” was related to the frequency with which counsel reported

encountering ethical dilemmas in their professional lives. Id. at 275.

44. Milton C. Regan, Jr., Moral Intuitions and Organizational Culture, 51 ST. LOUIS U. L.J. 941, 965 (2007)

(summarizing research that shows how managers employ non-moral prototypes as their default perceptual

framework); ROBERT JACKALL, MORAL MAZES: THE WORLD OF CORPORATE MANAGERS 6 (1988).

45. See Part II.B.3 (“Faithful Agent”) for a discussion of prevailing lawyers’ role ideologies that may

contribute to pressures to align one’s views to those of your de facto clients.

�2008]

GATEKEEPERS INSIDE OUT

421

ambiguity,46 clear and specific prescriptions will be more effective in encouraging gatekeeping than vague standards.47

C. FOUR QUADRANTS OF GATEKEEPING

To repeat, the first complication distinguished monitoring from interdiction.

The second complication emphasized the significance of distinguishing willingness from capacity, especially if we allow ourselves to incorporate not only

economics but social psychology and sociology in our modeling of “willingness.” By intersecting these insights, we see that potential gatekeepers can be

understood and evaluated by their: (1) willingness to interdict, (2) willingness to

monitor, (3) capacity to monitor, and (4) capacity to interdict. Stated another way,

these four factors are necessary components to effective gatekeeping. I have

numbered the Quadrants in clockwise fashion to correspond to the order that I

address them in this article.

Interdict

Monitor

Willingness

I. Willingness to Interdict

II. Willingness to Monitor

Capacity

IV. Capacity to Interdict

III. Capacity to Monitor

Quadrant I (Willingness to Interdict). Suppose that a gatekeeper discovers

facts suggesting illegality. Will she then take the next action to interdict

misconduct? Using Kraakman’s cops-on-the-beat metaphor, once the cop

actually sees a crime occurring, will she do something to stop it? If she’s two

months away from retirement with a pension and a violent melee has just erupted,

will she intervene without backup, or will she look the other way? If she sees a

health code violation at the doughnut shop that treats her daily to hot coffee and

crullers, will she be inclined to issue a warning or notify the local health

agency?48

Quadrant II (Willingness to Monitor). A gatekeeper closes the gate when she

knows that there has been misconduct. But how does the gatekeeper come to

know? In part, the gatekeeper must be willing to expend resources to be vigilant.

When red flags appear, the gatekeeper must be willing to probe further those

46. See Kim, supra note 37, at 1029-31 (noting how complex and ambiguous environments serve as a fertile

breeding ground for motivated reasoning) and 1048-52 (applying such insights to criticize regulations enacted

under SOX § 307 and the 2003 amendments to the ABA’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct).

47. See, e.g., Painter, supra note 34, at 1406-10 (describing how the American Bar Association has

persistently declined—for many years—to revise and clarify its Model Rule 1.13 which vaguely commanded

that the lawyer must act in the “best interests of the organizational client” when confronted with crime or fraud

committed by an organizational agent).

48. The two aforementioned hypothetical scenarios (imminent retirement and doughnut shop freebies) raise

“duty of care” and “duty of loyalty” issues, respectively. The first scenario raises the question of whether the

cop’s incentive structure encourages shirking while the second scenario raises the question of whether the cop

has conflicted loyalties.

�422

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS

[Vol. 21:411

suspicious circumstances. To continue the policing metaphor, it’s not enough that

the cop has a gun strapped to her hip and is willing to fire it when she sees a

mugging. She must actually do some patrolling–walk around the four square

blocks that constitute her beat. She must talk to the people who live there, follow

up on suspicious shadows down long alleys–even when it’s cold outside and a

warm doughnut shop beckons.

Quadrant III (Capacity to Monitor). Resolute willingness may in the end

matter little if fundamental capacity is lacking. For example, earnest vigilance

will fail to uncover misconduct if the gatekeeper has no access to the facts.

Imagine not a cop on the beat, but a police officer using videocameras from a

remote surveillance site. No matter how sincere and duty-bound, the technology

constrains what that officer can discover at a distance. If there is no audio,

gunshots cannot be heard. If the camera has blindspots, corners will remain in the

shadows. If the magnification and resolution are poor, no matter how much the

officer strains, she simply won’t be able to see.

Quadrant IV (Capacity to Interdict). Finally, even assuming that a gatekeeper

is capable and willing to monitor and perfectly eager to close the gate, she is only

as effective as her capacity to interdict. One reason why this capacity may be

lacking is if the wrongdoing client has access to multiple gates. If one gate shuts,

ten more may swing wide open. Suppose the cop on the beat also moonlights as

private security and is hired to help transport some item in the trunk across state

lines—“no questions asked.” A guard who asks too many questions (what am I

transporting? to whom? why?) won’t be hired again because another contractor

who just happens to be less curious will be waiting in the wings. The capacity to

interdict ultimately turns on the ease with which the wrongdoer can circumvent

any particular gatekeeper.

By unpacking two complications and cross-tabulating them, I have remapped

Kraakman’s gatekeeping theory and identified four criteria by which potential

gatekeepers may be evaluated. In analyzing “willingness,” my approach is to be

behaviorally realistic and not constrained by stylized models that emphasize

explicit, overt, expected utility calculations. By systematically running both

inside and outside counsel through this analytic mill, we come to unexpected

conclusions about the relative strengths and weaknesses of inside and outside

counsel for the gatekeeping role.

II. WILLINGNESS TO INTERDICT

The analytic mill starts here with Quadrant I. In this Part, my principal

objective is to revise prior understandings of “willingness” by being more

behaviorally realistic. Although behavioral realism is critical of the stylized

simplifications of rational choice theory (“RCT”), the insights from RCT and

behavioral realism are often mutually illuminating, not mutually exclusive. In

other words, we learn a great deal from examining both individual economic

�2008]

GATEKEEPERS INSIDE OUT

423

incentives—even if we accept that entirely different cognitive mechanisms (than

what RCT posits) are at work—and the pervasive situational forces unknowingly

experienced.49

In this vein, this Part identifies five important factors that go to the willingness

of a lawyer to interdict. Some of these factors are commonly attributed to RCT

(and thus I will refer to them as “rational choice factors”); others sound more in

behavioral realism, where I draw heavily from social psychology and sociology

(“behavioral realist factors”). I apply these five factors to elicit comparative

strengths and weaknesses of inside and outside counsel.

A. RATIONAL CHOICE FACTORS

Gatekeeping theory operates on the assumption that for the gatekeeper to act,

the expected benefits should outweigh the expected costs. The most salient

benefit of closing the gate is avoiding the costs associated with acquiescing in

misconduct. Thus, one can safely infer that a gatekeeper is likely to interdict

client wrongdoing if two RCT conditions are satisfied: the gatekeeper (1) stands

to lose much if its acquiescence in misbehavior is detected (the “high cost of

complicity”)50 and (2) stands to lose little by resisting the wrongdoer’s bribes (the

“low cost of resistance”).51 Put another way, a gatekeeper will interdict if (1) the

cost of complicity is high and (2) the cost of resistance is low.

1. HIGH COST OF COMPLICITY

a. Loss of Reputational Capital

Gatekeepers will interdict misconduct if they fear that failing to do so might

result in an irreparable loss to their longstanding reputations. In the securities

context, market gatekeepers such as investment banking and accounting firms act

as reputational intermediaries whom issuers pay to vouch for their disclosures to

the market. By certifying the issuer’s public statements to the market, these

intermediaries attest that they have evaluated the issuer and are prepared to stake

their reputation on the accuracy of the issuer’s statements.52 They effectively

49. See supra Part I.B.2 (describing my behavioral realist revision of gatekeeping theory’s modeling of a

gatekeeper’s willingness to interdict and monitor and how my revision, which fully considers arational

cognitive processes that are unleashed by situational forces, differs from the account posited by RCT).

50. See, e.g., Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 70 (noting that professionals who have made large

investments in their licenses and reputations make attractive gatekeepers because “they stand to lose too much if

their corruption is detected”).

51. Id. at 71 (noting that “diversified gatekeepers, who have proportionately less at stake in relationships

with particular clients or customers, are less likely to receive threats (or corrupt offers) that are large enough to

offset their expected costs of corruption”); Kraakman, Corporate Liability, supra note 10, at 891 (noting that

outsiders have different incentives from those of inside managers: “they are likely to have less to gain and more

to lose from firm delicts than inside managers”).

52. Gilson & Kraakman, Market Efficiency, supra note 10, at 620.

�424

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS

[Vol. 21:411

pledge their reputation to the issuer, which in turn increases investor confidence.53 Because reputation is hard to gain but easy to lose, these intermediaries

are viewed as ideal market gatekeepers because they already “face powerful

private incentives to prevent misconduct.”54

Of course, this reputation story presupposes that market gatekeepers have

already accumulated enough reputational capital to deter them from squandering

it away by vouching for a wayward issuer.55 The only way to accrue such

reputation is by acting as a repeat player in many securities transactions for many

issuers over many years.56 Large and long-lived accounting and investment

banking firms are thus seen as the gatekeepers of choice. Likewise, elite law firms

(not individual attorneys) that have accrued reputations for trustworthiness and

independence can serve this function.57 In sharp contrast, inside counsel are

viewed as lacking the threshold amount of reputational capital necessary to

discipline their behavior.58 As Coffee states:

[I]n-house counsel is seldom a reputational intermediary (as law and accounting firms that serve multiple clients are) because the in-house counsel cannot

easily develop reputational capital that is personal and independent from the

corporate client.59

This is a persuasive, logical story. But it is overstated.

First, the empirical data raise questions about the importance of reputational

capital to effective gatekeeping.60 To pick a salient counterexample, why would

53. Id.

54. Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 62.

55. Jonathan Macey & Hillary A. Sale, Observations on the Role of Commodification, Independence, and

Governance in the Accounting Industry, 48 VILL. L. REV. 1167, 1173 (2003).

56. COFFEE, GATEKEEPERS, supra note 9, at 2. Coffee goes on to note:

Because the gatekeeper is inherently an agent of its principal, its expected fee or commission is likely

to be far less than the gain that the principal itself expects to make from the transaction. As a result,

because the gatekeeper/agent expects less profit than its principal does, it can be more easily deterred

than its principal.

See id. at 5.

57. See Karl S. Okamoto, Reputation and the Value of Lawyers, 74 OR. L. REV. 15, 19 (1995); Ronald J.

Gilson & Robert H. Mnookin, Sharing Among the Human Capitalists: An Economic Inquiry into the Corporate

Law Firm and How Partners Split Profits, 37 STAN. L. REV. 313, 368 (1985) (“At the core of the firm’s ability to

pledge its reputation on behalf of its client is a perception by other parties that the firm is ‘independent’—that

the firm would not put its reputation on the line were the client’s statements not true.”).

58. Okamoto, supra note 57, at 19, 21, 33 (noting inside counsel’s relative inability to serve as a reputational

intermediary for their clients).

59. COFFEE, GATEKEEPERS, supra note 9, at 195.

60. To be sure, classical gatekeeping theory maintained a more nuanced understanding of reputation than I

have thus far portrayed (for the sake of clarity and brevity). Kraakman has observed that outsiders often lack the

ability to distinguish among firms, so they apply average reputations from a broad market segment. See

Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 97-98.

�2008]

GATEKEEPERS INSIDE OUT

425

Arthur Andersen have squandered its legendary reputation61 by signing off on

Enron’s shady accounting?62 Perhaps Anderson was an outlier, but an empirical

study covering 1,000 large public firms from 1997 to 2001 yielded no evidence

that the quality of public company audits performed by Andersen was any worse

than the other large accounting firms.63 Also, according to surveys of companies

who hire outside counsel, their reputational value is not declared to be important

for most transactions.64

Second, reputational information markets may not work as perfectly as

imagined. Public reports of ethical or legal breaches may not even link the

malfeasant individual to her firm,65 or may not be significantly correlated with

the seriousness of the infraction committed or the degree of harm inflicted. For

example, an exhaustive empirical study of securities class action settlements

from 1989 to 1994 observed that although underwriters settled twice as many

securities class action lawsuits as accountants and also paid more per case, there

was little to no press coverage on underwriters, in contrast to the voluminous

publicity devoted to accountants.66

Third, the information that does flow out may be artfully managed by

sophisticated public relations campaigns that introduce just enough ambiguity to

stanch serious reputational losses.67 Like public companies, law firms can settle

cases with regulators or plaintiffs while denying guilt. They can take advantage

of plausible deniability by characterizing individual wrongdoers as rogue

attorneys punished for their ultra vires actions while the firm publicly renews its

61. See Ken Brown & Ianthe Jeanne Dugan, Sad Account: Andersen’s Fall From Grace Is a Tale of Greed

and Miscues—Pushed to Boost Revenue, Auditors Acted as Sellers, Warred With Consultants—‘Three Pebbles

and a Boulder’, WALL ST. J., June 7, 2002, at A1 (citing an Andersen Heritage Center display devoted to press

clippings memorializing former firm leader Leonard Spacek’s accusing Bethlehem Steel of overstating profits in

1964 by more than 60% and lambasting the SEC for failing to crack down on fraudulent accounting).

62. See Robert A. Prentice, The Inevitability of a Strong SEC, 91 CORNELL L. REV. 775, 780-799 (2006)

(citing evidence that reputation insufficiently constrains gatekeeper behavior); Hillary A. Sale, Gatekeepers,

Disclosure and Issuer Choice, 81 WASH. U. L.Q. 403, 407 (2003) (critiquing reliance on reputational

constraints).

63. See Theodore Eisenberg & Jonathan R. Macey, Was Arthur Andersen Different? An Empirical

Examination of Major Accounting Firm Audits of Large Clients, 1 J. EMPIRICAL LEGAL STUD. 263, 264-65

(2004) (noting that its analysis “yields no evidence that accounting profession problems that lead to [financial]

restatements were unique to Andersen” and suggesting that “accounting profession problems are industrywide

and not linked to any particular firm”).

64. Steven L. Schwarcz, Explaining the Value of Transactional Lawyering, 12 STAN. J.L. BUS. & FIN. 486,

502-03 (2007) [hereinafter Schwarcz, Transactional Lawyering] (finding only weak support for the proposition

that transactional lawyers add value by acting as reputational intermediaries).

65. Ted Schneyer, Professional Discipline for Law Firms?, 77 CORNELL L. REV. 1, 34 (1991) [hereinafter

Schneyer, Professional Discipline].

66. Steven P. Marino & Renee D. Marino, An Empirical Study of Recent Securities Class Action Settlements

Involving Accountants, Attorneys or Underwriters, 22 SEC. REG. L. J. 115, 174 (1994).

67. Donald C. Langevoort, Where Were the Lawyers? A Behavioral Inquiry into Lawyers’ Responsiblity for

Clients’ Fraud, 46 VAND. L. REV. 75, 112 (1993) [hereinafter Langevoort, Where Were the Lawyers?].

�426

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS

[Vol. 21:411

commitment to ethics.68

Finally, due to intense competition, law firms may be more worried about

cultivating reputations for client devotion than client independence.69 Independence can mean, when one’s ethical duties call, having to deviate from the

clients’ express requests, something that high paying clients, who feel entitled to

every possible advantage, do not especially value.70

Of course, none of this is to say that inside lawyers have comparatively more

reputation than large outside law firms to lose: they do not. My only point is to

caution against an overeager acceptance of the reputation story.

b. Private Civil Liability

In addition to loss of valuable reputation, incentives to interdict can arise from

the threat of private civil liability.71 If outside law firms were held liable for

facilitating securities fraud, surely that would incentivize them to interdict by

raising the costs of complicity. Interestingly, recent legislative and judicial

developments have dramatically decreased the likelihood of such liability.72

First, in 1994, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Central Bank of Denver v.

First Interstate Bank of Denver against private liability for secondary actors—

those who aided and abetted a primary violation under the antifraud provisions of

the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.73 This decision greatly inhibited private

plaintiffs from suing law and accounting firms, who otherwise would be

vicariously liable for their agents’ facilitation of a primary violation.74 Because of

this decision, the “legal profession remained far more insulated than the

accounting profession, which still faced primary liability for its certification of

68. Donald C. Langevoort, Monitoring: The Behavioral Economics of Corporate Compliance with Law,

2002 COLUM. BUS. L. REV. 71, 102 (discussing companies’ strategies); Schneyer, Professional Discipline, supra

note 65, at 34.

69. Milton C. Regan, Jr., Professional Reputation: Looking for the Good Lawyer, 39 S. TEX. L. REV. 549,

558-60 (1998) [hereinafter Regan, Professional Reputation].

70. Id. at 560. As noted by Milton Regan, “With increased competition, potentially mobile clients correctly

perceive that they have leverage to press lawyers not just to do their bidding, but to do it exactly as they would

have it done and without regard for the legal or ethical niceties that typically give pause to members of the

guild.” Id. at 561.

71. Of course, all threats of legal liability have attendant reputational consequences, making it impossible to

segregate completely the “loss of reputational capital” from the threat of “private civil liability.”

72. For a comprehensive list of developments that have reduced the legal threat to gatekeepers, see COFFEE,

GATEKEEPERS, supra note 9, at 60-61.

73. Central Bank of Denver, N.A. v. First Interstate Bank of Denver, N.A., 511 U.S. 164, 191 (1994) (holding

“that a private plaintiff may not maintain an aiding and abetting suit under § 10(b)” of the Securities Exchange

Act of 1934).

74. To be clear, Central Bank of Denver did not abolish the vicarious liability of firms for their agents’

violations. See Robert A. Prentice, Conceiving the Inconceivable and Judicially Implementing the Preposterous: The Premature Demise of Respondeat Superior Liability Under Section 10(b), 58 OHIO ST. L.J. 1325

(1997) (arguing in favor of maintaining respondeat superior liability for Section 10(b) actions).

�2008]

GATEKEEPERS INSIDE OUT

427

the issuer’s financial statements.”75

Second, a year later, the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995

(“PSLRA”)76 enacted a number of measures that collectively eroded plaintiffs’

ability to pursue claims against law firms.77 These developments effectively

capped a general trend toward reducing the liability of law and accounting

firms.78 According to an SEC study completed in 1997,79 out of a total of 105

securities class actions filed in 1996, not a single lawsuit named a law firm as

defendant.80

In short, if civil liability for the large law firm was ever a significant threat, it

certainly is not now. Moreover, recent judicial attempts to expand the primary

75. COFFEE, GATEKEEPERS, supra note 9, at 216. Auditors were still potentially liable as primary participants

based on their public certifications.

76. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, Pub. L. No. 104-67, 109 Stat. 737, 758 codified as

amended at 15 U.S.C. § 78u-4 [hereinafter PSLRA].

77. Plaintiffs-side securities litigators blame PSLRA’s adoption of a particular judgment reduction method

(for Securities Exchange Act actions) as severely hampering plaintiffs’ ability to maintain actions against law

firms. See PSLRA, supra note 76, § 21D(g)(7)(B), 15 U.S.C. § 78u-4(g)(7)(B). The judgment reduction

provision complicates settling multi-party cases and can lead to plaintiffs’ opting to dismiss a co-defendant

(such as a law firm) rather than risk the verdict against the non-settling defendants being reduced by the amount

that corresponds to the percentage of responsibility of a settling co-defendant and thus potentially leading to a

denial of full recovery for the plaintiffs. If the law firm is not named as co-defendant or is otherwise dismissed,

the final judgment will not be reduced by the law firm’s percentage of fault (since the law firm will not be

deemed a settling co-defendant), in which case the non-settling co-defendants remain liable for the entire

verdict. Correspondence from William S. Lerach of Lerach Coughlin Stoia Geller Rudman & Robbins LLP to

author dated Aug. 8, 2007 (on file with author) [hereinafter Lerach Correspondence]. See also Marc I. Steinberg

& Christopher D. Olive, Contribution and Proportionate Liability under the Federal Securities Laws in

Multidefendant Securities Litigation After the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, 50 SMU L. REV.

337, 378 (1996) (noting that, under PSLRA’s judgment reduction method, the “risk of an inadequate settlement

falls on the plaintiffs, resulting in the potential denial of full compensation”).

For other reasons why secondary actors (law and accounting firms) enjoyed a reduced threat of legal liability

in the 1990s, see COFFEE, GATEKEEPERS, supra note 9, at 60-61 (citing PSLRA’s replacement of joint-andseveral liability with proportionate liability, heightened pleading standards, restriction of the sweep of the RICO

statute, adoption of safe harbor for forward-looking information as having a hindering effect on private

litigation). However, it seems that PSLRA’s proportionate liability provisions in particular had much less an

impact on law firms than on other secondary actors. See OFFICE OF GEN. COUNSEL, U.S. SEC. & EXCH. COMM’N,

REPORT TO THE PRESIDENT AND THE CONGRESS ON THE FIRST YEAR OF PRACTICE UNDER THE PRIVATE SECURITIES

LITIGATION REFORM ACT OF 1995 (1997), § IV. D (“Effect of the Act on Secondary Defendants”), available at

http://www.sec.gov/news/studies/lreform.txt [hereinafter PRACTICE UNDER THE PSLRA]; Marino & Marino,

supra note 66, at 163 (concluding that law firms do not act as deep pockets when an issuer is bankrupt and were

never much hurt by the joint-and-several liability aspects of securities laws in the first place).

78. Even prior to Central Bank of Denver and PSLRA, law firms may have already been facing a declining

threat of legal liability. See PRACTICE UNDER THE PSLRA, supra note 77, at § IV.D (reporting results of the

National Economic Research Associates study that from 1991 to June 1996, law firms were defendants in only

seven cases and reporting that plaintiffs’ bar attributed part of the decline in lawsuits to their inability to obtain

timely discovery—that may reveal misconduct by secondary actors—within the one-to-three year statute of

limitations imposed by Lampf, Pleva, Lipkind, Prupis & Petigrow v. Gilbertson, 501 U.S. 351, 359-61 (1991)).

79. See PRACTICE UNDER THE PSLRA, supra note 77, at § IV.D.

80. COFFEE, GATEKEEPERS, supra note 9, at 61. See PRACTICE UNDER THE PSLRA, supra note 77, at § IV.D

(“Our review of complaints in the 105 class actions filed under the Act reveals that accounting firms have been

named in six cases, corporate counsel in no cases, and underwriters in 19 cases.”).

�428

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS

[Vol. 21:411

liability of secondary actors, such as law and accounting firms,81 have been

rebuffed by the U.S. Supreme Court.82 It is thus unlikely that the central course of

Central Bank of Denver and PSLRA will be changed.

By contrast, what can be said about potential civil liability of inside counsel?

This question can be addressed on two levels—entity and individual liability. The

inside counsel is an employee of the company. To the extent that securities class

actions deter public companies from engaging in securities fraud,83 it follows that

the employees through which the company “acts” are also deterred from

securities fraud. Of course, this trickle down theory of deterrence, from entity to

complying employee, has been hotly disputed.84 Consider just the single

complication of moral hazard induced by insurance,85 which covers almost all of

the costs of corporate and individual liability (including defense and settlement

costs) arising out of securities lawsuits.86

There is, however, one area under the Securities Act of 1933 (the “Securities

Act”) where the in-house general counsel should be directly incentivized because

of potential individual liability. If the general counsel signs her company’s

registration statement in her capacity as a senior executive officer of the

company, she is personally liable for misstatements under Section 11 of the

81. In the past several years, lower courts have adopted various theories to allow private lawsuits against

secondary actors including law firms and lawyers. See, e.g., Steve L. Schwarcz, Financial Information Failure

and Lawyer Responsibility, 31 J. CORP. L. 1097, 1099-100 (2006); John C. Coffee, Jr., Gatekeeper Failure and

Reform: The Challenge of Fashioning Relevant Reforms, 84 B.U. L. REV. 301, 338, 340 (2004) (observing a

‘judicial shift . . . toward imposing greater liability on gatekeepers‘ in financial frauds and showing empirical

data which indicate that ‘the risk for gatekeepers is real and growing‘).

82. See Stoneridge Inv. Partners, LLC v. Scientific-Atlanta, Inc. 128 S. Ct. 761 (2008) (reaffirming that the

implied private right of action for securities fraud under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

does not extend to aiders and abettors and rejecting plaintiffs’ “scheme liability” theory).

83. John C. Coffee, Reforming the Securities Class Action: An Essay on Deterrence and Its Implementation,

106 COLUM. L. REV. 1534, 1543, 1548 (2006) [hereinafter Coffee, Securities Class Action].

84. See, e.g., Jennifer H. Arlen & William J. Carney, Vicarious Liability for Fraud on Securities Markets:

Theory and Evidence, 1992 U. ILL. L. REV. 691, 704-17 (arguing against entity liability—and in favor of agent

liability—because firms are not superior to courts and private plaintiffs in identifying and sanctioning

wrongdoers ex post, firms do not have superior incentives to screen ex ante for honest agents, and firms do not

have superior incentives to monitor current employees); Jennifer Arlen, The Potentially Perverse Effects of

Corporate Criminal Liability, 23 J. LEGAL STUD. 833 (1994) (arguing that strict vicarious criminal liability may

increase corporate crime by incentivizing companies to reduce corporate enforcement expenditures—that

would otherwise facilitate crime detection—in an effort to decrease the company’s expected criminal liability);

Deborah A. DeMott, Organizational Incentives to Care About the Law, 60 LAW & CONTEMP. PROBS. 39 (1997)

(defending vicarious liability as a reflection of the principal’s right and presumed ability to define the agent’s

incentive structure).

85. Tom Baker & Sean J. Griffith, The Missing Monitor in Corporate Governance: The Directors’ &

Officers’ Liability Insurer, 95 GEO. L.J. 1795, 1798, 1808 (2007) (reporting that insurers generally do not offer

loss prevention services and do not otherwise monitor the corporate governance of their corporate insureds).

According to the authors, executive and risk manager agency costs and the fact that insurance insulates

companies and their managers from the financial impact of liability together suggest that these insurance

policies create a moral hazard for corporate officers. Id. at 31, 47-51.

86. Id. at 1804-05. Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance (D&O insurance) protects the assets of the

corporation as well as its directors and officers. See id. at 1797.

�2008]

GATEKEEPERS INSIDE OUT

429

Securities Act,87 subject to a “due diligence” defense.88 By contrast, outside law

firms are never subject to Section 11 liability.89

In sum, if we expect private civil liability to raise the costs of complicity, that

expectation is not met by current law. And as between outside law firms and

inside counsel, if there is any marginal difference in potential liability, the inside

counsel may bear a slightly higher cost.

c. SEC Enforcement

Even if there is little chance of private civil liability, what about the threat of

SEC enforcement? Even in the aftermath of Central Bank of Denver, the SEC

retained its ability to sanction secondary participants for knowingly aiding and

abetting a securities fraud.90 The SEC can also sanction lawyers and law firms as

primary violators or for “causing” a securities fraud under § 15(c)(4) of the

Securities Exchange Act of 193491 and has a number of civil and administrative

tools at its disposal.92 In a post-Sarbanes-Oxley93 world, do outside law firms risk

being charged by the SEC? And if so, how does that probability compare to that

faced by inside counsel?

So far, while the SEC has stepped up enforcement actions against individual

inside and outside lawyers,94 the SEC has generally refrained from charging large

law firms. When it has gone after outside lawyers, it has targeted sole

87. 48 Stat. 74, 82 (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 77k (1982)).

88. As summarized by Kraakman, “All § 11 participants must be able to prove that ‘after reasonable

investigation,’ they had ‘reasonable ground’ to believe those portions of the registration statement not made

under the authority of an expert . . . [A]ll participants (other than experts) must not have had reasonable ground

to disbelieve the portions of the registration statement prepared by the experts (§11 (b)(3)).” Kraakman,

Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 86.

89. Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 82 (noting that “virtually all key participants in the preparation

of the [registration] statement except attorneys are potentially iable under Section 11”). Of course, attorneys

remain subject to private malpractice liability vis-a-vis their clients.

90. In 1995, PSLRA clarified that the SEC (but not private parties) may bring enforcement actions and

administrative proceedings against aiders and abettors of securities fraud, so long as the SEC could prove that

such persons “knowingly” did so. See COFFEE, GATEKEEPERS, supra note 9, at 215; JAMES D. COX ET AL.,

SECURITIES REGULATION—CASES AND MATERIALS 734-35 (4th ed. 2004) (discussing SEC’s authority to

prosecute secondary actors as aiders and abettors).

91. THOMAS LEE HAZEN, 3 LAW SEC. REG. § 9.8[2] (5th ed. 2006).

92. The SEC may bring civil injunction actions in the federal district courts under § 20(b) of the Securities

Act of 1933 and § 21(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and administrative proceedings under Rule

102(e) of the SEC’s Rules of Practice, and administrative cease-and-desist proceedings. Lewis D. Lowenfels,

Alan R. Bromberg, & Michael J. Sullivan, Attorneys as Gatekeepers: SEC Actions Against Lawyers in the Age

of Sarbanes-Oxley, 37 U. TOL. L. REV. 877 (2006). In addition to civil fines, possible SEC sanctions include

censure, temporary suspension, a cease and desist order, and permanent disbarments from practice before the

SEC. 17 C.F.R. § 201.102(e)(1) (2002).

93. Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. Pub. L. No. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745 (codified in scattered sections of 11, 15,

18, 28 and 29 U.S.C. (Supp. III 2003)).

94. See, e.g., Lowenfels et al, supra note 92, at 929 (noting that the “sheer number of SEC actions against

lawyers after the enactment of SOX has increased dramatically”). In a preliminary study that I have performed,

based only on a review of SEC litigation releases from January 2002 to April 2007, of approximately 82

�430

THE GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LEGAL ETHICS

[Vol. 21:411

practitioners or individual lawyers from small firms.95 So why has the SEC been

reluctant to bring cases against large law firms?96 One commentator has

suggested that SEC attorneys, who often come from prestigious law firms, are

leery of bringing cases against the very kinds of firms they hope to join in the

future.97 Or perhaps the SEC is continuing to ration its limited (although recently

expanded) financial resources by avoiding costly prosecutions of large law

firms.98 Unless we are to believe that large law firms simply do not commit

securities infractions,99 SEC inaction translates into weak deterrence of large law

firms.100

To summarize so far: large law firms were identified as the legal gatekeepers of

choice because they would suffer a high cost of complicity: the potential loss of

their reputation and legal liability (in the form of private civil liability and SEC

enforcement). But my analysis casts some doubt on that thesis in light of modern

developments, especially the judicial erosion of private aiding-and-abetting

liability, which had historically operated as one of the primary deterrents for law

firms.

2. LOW COST OF RESISTANCE

On the other side of the balance sheet of rational choice factors is the cost of

resistance. To be effective, a gatekeeper should also stand to lose little from

publicized SEC actions naming attorneys as defendants, a little more than half of the cases implicate inside

counsel. Research on file with author.

95. Michael A. Perino, SEC Enforcement of Attorney Up-The-Ladder Reporting Rules: An Analysis of

Institutional Constraints, Norms and Biases, 49 VILL. L. REV. 851, 860 (2004). See also Sec. & Exch. Comm’n,

Study and Report on Violations by Securities Professionals (2003), available at http://www.sec.gov/news/studies/

sox703report.pdf. This Report lists 13 enforcement actions—from 1998 to 2001—taken against “accounting

firms” but none listed against “law firms.” Id. app. at 10. By contrast, this Report notes that the SEC took action

against 49 (individual) lawyers during 1998-2001; however, it is unclear from the compilation whether the

alleged infractions arose out of the lawyer’s rendering of legal services or conduct unrelated to lawyering (for

example, insider trading infractions). It is noteworthy that of the 1,596 securities professionals charged, only 13

of them were charged solely as aiders and abettors. Id. at 10.

96. See, e.g., Perino, supra note 98, at 858-65 (describing the institutional incentives and constraints that

explain SEC’s reluctance to bring disciplinary proceedings against lawyers and law firms, including the fact that

the SEC is a lawyer-dominated agency sharing cultural norms of lawyers generally, implicit recognition of the

hindsight bias, cognitive conservatism, risk-aversion in the selection of cases, and self-serving “revolving-door”

careerist motivations).

97. Id. at 863-64.

98. See, e.g., COFFEE, GATEKEEPERS, supra note 9, at 155 (citing the SEC’s frozen budget during the 1990s

and its other enforcement priorities as explaining its past reluctance to charge a Big Six accounting firm);

Perino, supra note 95, at 853-57 (describing the SEC’s budget and personnel constraints).

99. See David J. Beck, The Legal Profession at the Crossroads: Who Will Write the Future Rules Governing

the Conduct of Lawyers Representing Public Corporations?, 34 ST. MARY’S L.J. 873, 905 (2003) (reporting that

SEC staff members have remarked that lawyers failed their gatekeeping duties because, in part, the SEC has

declined to use its disciplinary powers, preferring to leave the work to state disciplinary committees).

100. See Erling Eide, Economics of Criminal Behavior, IN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF LAW & ECONOMICS 345, 359

(Boudewijn Bouckaert & Gerrit De Geest eds., 2000) (reviewing studies showing empirical support that the

probability of punishment has a deterrent impact, while the effect of the severity of sanctions is less conclusive).

�2008]

GATEKEEPERS INSIDE OUT

431

resisting the wrongdoing client. The cost of resistance is typically the gatekeeper’s loss of ordinary patronage from its wrongdoing client. So, gatekeepers who

rely heavily on single clients are quite susceptible to clients’ threats to take their

business elsewhere.101 Conversely, gatekeepers with more diversified client

bases have proportionately less at stake in preserving particular client relationships.102 This simple logic underlies the common observation that for law and

accounting firms, a “diversified client base fosters professional independence.”103 And since large size often serves as a reasonably proxy for larger

assets and a wider portfolio of clients,104 larger law firms should theoretically be

superior gatekeepers to stand-alone individuals, such as inside counsel.

But, again, recent developments have complicated the conventional wisdom.

How could Arthur Andersen, an accounting firm with 2,300 audit clients

generating $9.34 billion in revenues fail to gatekeep when its client Enron

represented less than 1% of its total annual revenue?105 The answer may lie in the

fact that large firms still suffer from principal-agent problems. The nominal

gatekeeper is the outside firm, but the “functional gatekeepers” are “small teams,

directed by one or more partners, which actually conduct audits, prepare legal

opinions, or otherwise facilitate client transactions.”106 That small team (as

agent) may act against the interests of the firm (principal), and some such story is

typically used to explain the Andersen debacle.107

If we examine the incentives of the functional gatekeeper, the conventional

wisdom about the vast superiority of large firms becomes tough to defend.

Recently published sociological research on 787 members of the Chicago bar108

suggests that lawyers at larger firms are more dependent on any particular client

than lawyers at small firms.109 The study reported that sole practitioners and

lawyers at the smallest law firms had large numbers of clients and “spent a

101. Kraakman, Gatekeepers, supra note 8, at 71. As noted by Kraakman, the threat to withdraw ordinary

patronage is powerful because it is “easily valued, easily arranged (it may be wholly implicit) and, most

important, difficult to detect in the event of a later investigation.” Id. at 71.

102. Id.

103. Id.

104. Id. at 72.

105. Arthur Andersen, Andersen Revenues by Geographic Area (2002), http:// www.andersen.com/website.nsf/

content/MediaCenterFacts& Figures?OpenDocument (reporting 2001 figures).