mc NO 13

2019

manuscript cultures

Hamburg | Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures

ISSN 1867–9617

�PUBLISHING INFORMATION | MANUSCRIPT CULTURES

Publishing Information

Homiletic Collections in Greek and Oriental Manuscripts

Edited by Jost Gippert and Caroline Macé

Proceedings of the Conference ‘Hagiographico-Homiletic Collections in Greek, Latin and Oriental Manuscripts –

Histories of Books and Text Transmission in a Comparative Perspective’

Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures, Universität Hamburg, 23–24 June 2017

Layout

Editors

Astrid Kajsa Nylander

Prof Dr Michael Friedrich

Universität Hamburg

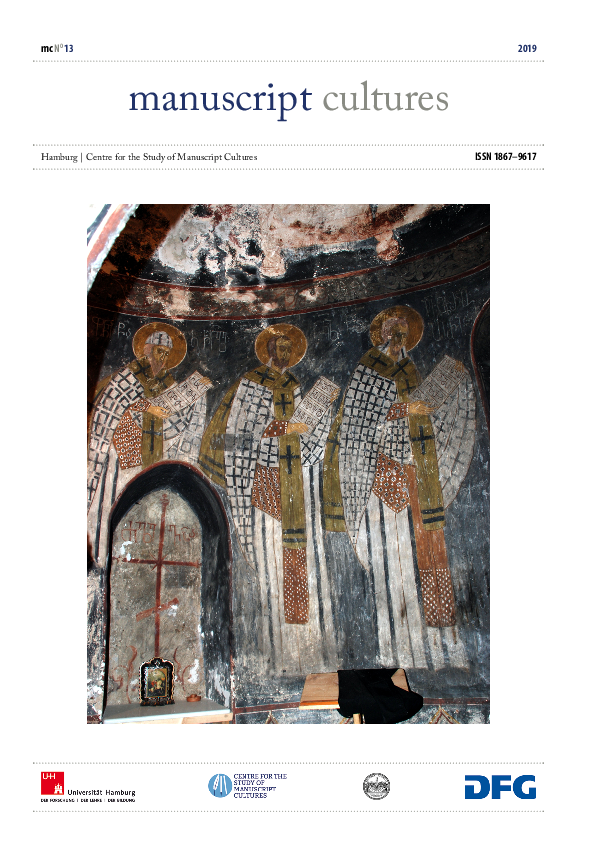

Cover

Asien-Afrika-Institut

The front cover shows the three church fathers Cyril of Jerusalem, Nicholas of Myra

Edmund-Siemers-Allee 1/ Flügel Ost

and John Chrysostom in a 16th-century fresco of the Church of the Archangels in

D-20146 Hamburg

Matskhvarishi, Latali, Svanetia (photography by Jost Gippert). All three fathers bear

Tel. No.: +49 (0)40 42838 7127

a board with text fragments from the Liturgy by John Chrysostom (CPG 4686) in

Fax No.: +49 (0)40 42838 4899

Georgian; the text passage held by Cyril of Jerusalem is the beginning of the sentence

michael.friedrich@uni-hamburg.de

რამეთუ სახიერი და კაცთ-მოყუარე ღმერთი ხარ ‘For you are a benevolent and

philanthropic God’, which also appears in lines 6–7 of Fig. 1 on p. 2 below (from an 11th-

Prof Dr Jörg Quenzer

century scroll of the Iviron Monastery on Mt Athos, ms. Ivir. georg. 89).

Universität Hamburg

Asien-Afrika-Institut

Copy-editing

Edmund-Siemers-Allee 1/ Flügel Ost

Carl Carter, Amper Translation Service

D-20146 Hamburg

www.ampertrans.de

Tel. No.: +49 40 42838 - 7203

Fax No.: +49 40 42838 - 6200

joerg.quenzer@uni-hamburg.de

Mitch Cohen, Berlin

Print

Editorial Office

AZ Druck und Datentechnik GmbH, Kempten

Dr Irina Wandrey

Printed in Germany

Universität Hamburg

Sonderforschungsbereich 950

‘Manuskriptkulturen in Asien, Afrika und Europa’

Warburgstraße 26

D-20354 Hamburg

Tel. No.: +49 (0)40 42838 9420

Fax No.: +49 (0)40 42838 4899

irina.wandrey@uni-hamburg.de

ISSN 1867–9617

© 2019

www.manuscript-cultures.uni-hamburg.de

SFB 950 ‘Manuskriptkulturen in Asien, Afrika und Europa’

Universität Hamburg

Warburgstraße 26

D-20354 Hamburg

manuscript cultures

mc NO 13

�1

CONTENTS | MANUSCRIPT CULTURES

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

2 | Homiletic Collections in Greek and Oriental Manuscripts – Histories of Books and Text Transmission from a Comparative Perspective

by Jost Gippert and Caroline Macé

ARTICLES

07 | The Earliest Greek Homiliaries

by Sever J. Voicu

15 | Gregory of Nyssa’s Hagiographic Homilies: Authorial Tradition and Hagiographical-Homiletic Collections. A Comparison

by Matthieu Cassin

29 | Unedited Sermons Transmitted under the Name of John Chrysostom in Syriac Panegyrical Homiliaries

by Sergey Kim

47 | The Transmission of Cyril of Scythopolis’ Lives in Greek and Oriental Hagiographical Collections

by André Binggeli

63 | A Few Remarks on Hagiographical-Homiletic Collections in Ethiopic Manuscripts

by Alessandro Bausi

081 | Cod.Vind.georg. 4 – An Unusual Type of Mravaltavi

by Jost Gippert

117 | The Armenian Homiliaries. An Attempt at an Historical Overview

by Bernard Outtier

123 | Preliminary Remarks on Dionysius Areopagita in the Arabic Homiletic Tradition

by Michael Muthreich

131 | Compilation and Transmission of the Hagiographical-Homiletic Collections in the Slavic Tradition of the Middle Ages

by Christian Hannick

143 | Contributors

145 | Picture Credits

146 | Indices

146 | 1. Authors and Texts

157 | 2. Manuscripts and Other Written Artefacts

161 | Announcement

mc NO 13

manuscript cultures

�29

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

Article

Unedited Sermons Transmitted under the Name of

John Chrysostom in Syriac Panegyrical Homiliaries*

Sergey Kim | Paris – Aubervilliers

1. Preamble. Preaching to create books or books to create preaching?

On 1 September 691, the Quinisext Council convened in the

‘Trullus’ chamber of the Palace of Justinian II; it issued 102

rules of administrative and canonical value.1 Its rule no. XIX

endeavours to formulate a methodology of predication by

delimiting the personal initiative of homilists and demanding

that preachers rely primarily on the teaching of the ancient

Fathers.

19. The superiors of the Churches must instruct all their

clergy and their people in true piety every day, but especially

on Sundays, choosing for them from divine Scripture the

thoughts and judgements of truth and following unswervingly

definitions already set forth and the tradition of the Godbearing Fathers. If a Scriptural passage should come up for

discussion, they shall in no wise interpret it differently than the

luminaries and Doctors of the Church have set down in their

writings (συγγραμμάτων). In this way shall they distinguish

themselves, rather than by composing their own works, being

at times incapable of this and thereby falling short of what

is proper. For through the teaching of the aforementioned

Fathers the people are given knowledge of important things

and virtues, and of unprofitable things and those to be rejected:

thus they reform their lives for the better and escape being

taken captive by the emotions of ignorance […]2

*

By the term ‘panegyrical homiliary’, here we mean a manuscript containing a collection of homilies by different authors organised according to the

logic of a Church calendar (cf. the Greek πανήγυρις – ‘a feast, a festive

celebration’).

1

For a recent volume on the Council in Trullo see Nedungatt and

Featherstone 1995.

Although this instruction echoes the Apostolic Canon no.

LVIII3 regarding the duty of the bishops to preach, the

general accent here is entirely different. The preacher is

invited to hold close to the writings (συγγραμμάτων) of

the ancient Fathers; furthermore, it could be argued that the

decree presupposes a library or a collection of homiletic and

exegetic patristic texts at the disposal of the homilist. While

inaugurating a conservative approach to the art of preaching,

the decree implies that the bishops should pay special

attention to the written text of the forerunners and that they

read and cite what has been written before.

It is tempting to suggest a link between this tendency

towards homiletical conservatism expressed by the conciliar

decree and the emergence of a new genre of panegyrical

homiletical manuscripts in the Christian book culture. It

is not impossible that one – albeit indirect – reason why

panegyrical homiliaries emerged as a book type was the

demand for ancient homiletic texts promoted by the Fathers

of the Council in Trullo.

It could be argued as well that, chronologically, the most

ancient panegyrical homiliaries of the Christian East go

back to this very period, i.e. to the end of the seventh and

the beginning of the eighth century. In Armenian, almost all

panegyrical homiliaries are derivative of the large homiliary

of Sołomon of Makʿenocʿ, who accomplished his titanic endeavour around the year 747.4 In Georgian, the palimpsest

homiliary with khanmeti linguistic features (manuscript Tbilisi, National Centre of Manuscripts, S-3902) is datable to

3

‘If any bishop or presbyter neglects the clergy or the people, and does not

instruct them in the way of godliness, let him be excommunicated, and if he

persists in his negligence and idleness, let him be deposed’ (my translation).

See Joannou 1962, 38.

2

For the English translation and a critical edition of the Greek text, see

Nedungatt and Featherstone 1995, 94–9696; see also Sever Voicu, this

volume, 13, n. 52.

mc NO 13

4

See Bernard Outtier, this volume, 117ff.; see also Van Esbroeck 1984,

237–238.

manuscript cultures

�30

the beginning of the eighth century5 or even to the seventh

century.6 For the Syriac, we have a number of manuscripts

that contain corpora (or fragments of corpora) by various

authors – Aphrahat,7 Ephrem,8 Chrysostom,9 Severus of Antioch10 etc. – from the fifth (!) century onwards, but the earliest panegyrical homiliaries in the Syriac language go back at

most to the mid-eighth century.

One would also wish to recall that, back in 1910, Anton

Baumstark endeavoured to propose a typology of Syriac

panegyrical homiliaries,11 suggesting that the most ancient

type of panegyrical homiliary comprised mostly translated

and, consequently, prose homilies, called turgomo (as

opposed to original Syriac rhymed or rhythmic homilies,

memro). Baumstark deplored the fact that no pure ‘prose’

homiliaries had survived. He argued that the second stage of

evolution was the contamination of the ‘prose’ homiliaries

with the original Syriac memro sermons. This must have

happened ‘an der Wende des 7. zum 8. Jahrhundert’ (‘at

the turn of the seventh to the eighth century’)12 according

to Baumstark’s calculations. A further stage of development,

not relevant for our research here, was the mixture of

hymnography with homiletic materials within a single

volume – hudrō. What is important to note is that the intense

evolution of Syriac homiliaries took place in the seventh to

eighth centuries, as put forward by Baumstark.

With all due caution, we find it quite symptomatic that the

burgeoning of the panegyrical type of homiliaries throughout

the cultures of the Christian East fits the general context of

the homiletical conservatism witnessed by the canonical

legislation of the Council in Trullo.

5

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

2. Syriac panegyrical homiliaries and John Chrysostom

The procedure of constituting early panegyrical homiliaries

in the Eastern Christian cultures, and especially in Syriac, is

of utmost interest, given that their compilers used materials

that are no longer available to us. It is instructive to recall

that immediately after Albert Ehrhard published the first

volume of his monumental work on the typology of the

Greek homiliaries, Charles Martin underlined the role of the

Oriental homiliaries, viz. Syriac ones, for the study of the

earliest stage of homiletic book culture.13 It is on his trail

that Joseph-Marie Sauget undertook a systematic analysis

of the Syriac panegyrical homiliaries in a series of studies,

venturing to elucidate the principles of the compilation of

Syriac homiliaries and of the use of translated Greek texts.14

In our paper, we limit ourselves to the texts, either

translated into Syriac from Greek or original Syriac compositions, that the earliest Syriac panegyrical homiliaries

transmit under the name of John Chrysostom. It turns out

that several homilies ascribed to him in their titles or their

explicits have not yet been edited or altogether studied.

Surprisingly, a total of 38 such sermons showed up in the

Syriac panegyrical homiliaries. In what follows, we offer a

list of unedited Chrysostomica and Pseudo-Chrysostomica

extant in Syriac panegyrical collections, hoping that this list

will encourage specialists in Patristic and Oriental Christian

Studies to proceed to editions and studies of this hitherto

neglected heritage.15

We have not included in the list two Pseudo-Chrysostomian

texts discovered recently by Paul Géhin,16 because the manu-

See Šaniʒe 1927.

6

See Jost Gippert, this volume, 86; see also Gippert 2016, 69 and especially

Gippert 2017, 896.

7

See, for example, the manuscript London, British Library, Add. 17182

(474 and 512).

8

See Butts 2017 for a recent study on the oldest textual witnesses of

Ephrem’s works.

13

9

14

See, for example, Childers 2013 and Childers 2017.

10

See the manuscript Vatican City, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat.

sir. 143 (563).

Martin 1937, 355–358.

Sauget 1961, Sauget 1968, Sauget 1985, Sauget 1986; see also a brief

overview in Brock 2007, 19–20.

15

Baumstark 1910, 53–62, chapter ‘Die nichtbiblischen Lesestücke (das

Homiliar)’.

See the exemplary study Chahine 2002, in which one of the Syriac

texts attributed to John Chrysostom was edited on the basis of panegyrical

homiliaries and identified as a peculiar redaction of the homily Sermo cum

iret in exsilium (CPG 4397).

12

16

11

Baumstark 1910, 56.

manuscript cultures

See Géhin 2017, 869–870 and 873.

mc NO 13

�31

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

scripts that contain them (Sinai syr. 1017 and Sinai syr. 1618)

are not panegyrical homiliaries.

For the purpose of the present study, we used the following

manuscripts:

Eighth century

• Vatican City, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana (BAV), Vat.

sir. 25319 (mid-eighth century) (Fig. 1)

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 36820 (mid-eighth century)

Ninth century

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 36921 (first quarter of the ninth

century)

Tenth to eleventh century

• Damascus (olim Homs), Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate

(SOP), syr. 12/1922

Fig. 1: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 253, fol. 75r.

17

In defunctos.

MS: Sinai, syr. 10, fols 60v–62r

BIBL: Géhin 2017, 869–870 (no. A1b)

̈ ܕܝܠܗ ܟܕ ܕܝܠܗ ܕܥܠ ̈ܚܫܐ ܘܡܬܬܘܝܢܘܬܐ ܘܒܘܝܥܐ ܕܥܠ

TIT: ܥܢܝܕܐ

‘Of the same, on the suffering, the penitence and the delay concerning those

who passed away’

̈

INC: ܐܚܝ ܟܠܢܫ ܠܡܦܛܪ ܐܝܬ ܠܗ ܡܢ ܥܠܡܐ ܘܠܡܫܢܝܘ ܡܢ ̈ܚܝܐ

‘My brothers, everyone has to leave the world and to depart from life’

̈ ܡܬܒܣܡܝܢ ܘܒܓܗܢܐ ܕܥܘܪܐ

̈

DES: ܡܫܬܢܩܝܢ ܠܥܠܡ ܥܠܡܝܢ

ܫܘܒܚܐ ܡܢ ܟܠ ܕܒܡܠܟܘܬܐ

ܐܡܝܢ

‘Glory from all those who take pleasure in the kingdom and those who are

tormented in the Gehenna of blindness, to the age of the ages, amen’.

18

An unidentified fragment in a section comprising quotations from

Chrysostomian works.

MS: Sinai, syr. 16 , fols 195ra–b (inc. mut.)

BIBL: Géhin 2017, 873 (no. B2d)

TIT: —

INC: ( ܘܛܘܠܫܐ...)

‘(…) and the impurity’

DES: ܘܝܬܒ ܥܠ ܝܡܝܢܐ ܕܐܠܗܐ ܐܒܘܗܝ ܕܠܗ ܫܘܒܚܐ ܘܐܠܒܘܗܝ ܕܫܠܚܗ ܠܦܘܪܩܢܢ

ܘܠܪܘܚܐ ܕܩܘܕܫܐ ܗܫܐ ܘܒܟܠܙܒܢ ܘܠܥܠܡ ܥܠܡܝܢ ܐܡܝܢ

‘and sits on the right hand of God, His Father, to Him and to His Father who

sent our Saviour, and to the Spirit of holiness, now and in all times and to

the age of ages, amen’.

19

See Sauget 1968 and a recent correction in Kim 2018. The manuscript is

available in digitised form on the website of the Vatican Library:

<https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.sir.253>.

20

Sauget 1961. See the digitised manuscript on the website of the Vatican

Library: <https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.sir.368>.

21

Sauget 1961. See the digitised manuscript on the website of the Vatican

Library: <https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.sir.369>.

22

Fig. 2: Berlin, SPK, Sachau 28/220, fol. 43r.

Brock 1994–1995; Sauget 1986, 144–145.

mc NO 13

manuscript cultures

�32

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

Eleventh century

• Damascus (olim Homs), SOP, syr. 12/2023 (1000)

• London, British Library (BL), Add. 1216524 (1015) (Figs

4–13 and 15).

• Berlin, Staatsbibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz (SPK),

Sachau 28/22025 (beginning of the eleventh century) (Fig. 2)

Twelfth century

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 11726 (Fig. 3)

Twentieth century

• Birmingham, Cadbury Research Library, Mingana Collection, syr. 54527 (1929)

Additional manuscripts

We have occasionally also used the following homiliaries:

• London, BL, Add. 1451628 (ninth century)

• London, BL, Add. 1451529 (893)

• London, BL, Add. 1472530

• London, BL, Add. 14727.31

Fig. 3: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 117, fol. 28r.

Unseen manuscripts

We have unfortunately not had access to:

• the manuscript Chicago, Oriental Institute, A. 1200832

(eleventh to twelfth century)

23

Brock 1994–1995, Sauget 1986, 144–145.

24

Wright 1871, 842–851 (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986.

25

See Malki 1985, Brock 1985, and especially Sauget 1985. See the

digitised manuscript on the website of the Berlin State Library: <http://

resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0001588000000000>.

26

See Assemani and Assemani 1759, 1759, 87–107 and Sauget 1968b, 133–

135. See the digitised manuscript on the website of the Vatican Library:

<https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.sir.117>.

27

See Rilliet 1982. In spite of its recent date, this Syriac homiliary comprises

numerous texts from medieval panegyrical collections; the scribe copies the

colophon of one of them dated 1312 (see Rilliet 1982, 579–580).

28

Wright 1870, 244–246 (no. CCCVIII).

29

Wright 1870, 240–243 (no. CCCVI).

30

Wright 1871, 827–828 (no. DCCCXIV)

31

Wright 1871, 886–890 (no. DCCCXLVIII).

32

v

Fig. 4: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 68 .

manuscript cultures

See the summary description in Vööbus 1973a, 121–127 and Vööbus

1973b, 81–87.

mc NO 13

�33

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

• the lost codex Jerusalem, St Mark’s Monastery, Syr. 4333

(before the year 1143/1144).

3. Analytical list of unedited Chrysostomica and Pseudo-Chrysostomica

CPG 514534

CPG 5145.1

In sanctum ieiunium

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 22, fols 68v–71v (Fig. 4)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/19, no. 39, fols 142b sqq.

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 41, fols 171a sqq.

BIBL: Wright 1871, 843b (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986,

140; Brock 1994–1995, 616 and 622.

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܨܘܡܐ ܩܕܝܫܐ ܕܐ̈ܪܒܥܝܢ.ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ

‘Of holy Mar John, sermon on the holy Lent of forty

(days)’

INC: ܥܐܕܐ ܗܘ ܓܝܪ ܫܪܝܪܐ.ܒܥܐܕܐ ܪܒܐ ܟܢܫܢܢ ܝܘܡܢܐ ܕܢܬܒܣܡ

ܡܐ ܕܒܡܝܬ̈ܪܬܐ ̇ܩܪܒܐ.ܕܢܦܫܐ

‘Nous sommes réunis aujourd’hui pour nous réjouir à

propos d’une grande fête. C’est, en effet, une véritable

(fête) pour l’âme lorsque celle-ci par les vertus se

rapproche (de Dieu)’ (Sauget 1986, 140).

Fig. 5: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 93v.

CPG 5145.2

In sanctum ieiunium et de paenitentia

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 30, fols 93v–96r (Fig. 5)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/19, no. 41, fols 147b sqq.

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 43, fols 178a sqq.

BIBL: Wright 1871, 844b (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986,

140; Brock 1994–1995, 616 and 622.

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܨܘܡܐ ܩܕܝܫܐ ܘܥܠ.ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ

ܬܝܒܘܬܐ

‘Of holy Mar John, sermon on holy Lent and on repentance’

INC: ܐܡܪ.ܡܢ ܩܕܡ ܝܘܡܐ ܟܕ ܥܡܟܘܢ ̇ܡܡܠܠ ܗܘܝܬ ܥܠ ܨܘܡܐ

ܗܘܝܬ ܕܙܒܢܐ ܗܘ ܕܬܝܒܘܬܐ

‘(Il y a un jour), je vous ai parlé du jeûne: je disais que

c’est le temps de la pénitence’ (Sauget 1986, 140).

33

See the description by Baumstark 1911, 300–309 and interesting remarks

in Baumstark 1910, 54–56.

34

This Clavis patrum Graecorum (ed. Geerard 1974–1998; CPG) number

contains only unedited Syriac homilies that do not have parallel versions in

other ancient languages.

mc NO 13

Fig. 6: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 120r.

manuscript cultures

�34

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

CPG 5145.3

In meso-ieiunium quaranta dierum

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 38, fols 120r–121v (Fig. 6)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/19, no. 63, fols 200a sqq.

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 65, fols 255b sqq.

BIBL: Wright 1871, 845a (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986,

140; Brock 1994–1995, 617 and 623.

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܡܨܥܬ ܨܘܡܐ ܩܕܝܫܐ.ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ

ܕܐ̈ܪܒܥܝܢ

‘Of holy Mar John, sermon on the middle of the holy Lent

of forty (days)’

INC: ܡܢܥ ܠܗ.ܐܓܘܢܗ ܕܨܘܡܐ ܟܕ ܡܫܬܘܫܛ ܒܪܗܛܗ ܠܩܕܡܘܗ

ܠܡܨܥܬܐ ܕܙܒܢܐ

‘Le combat du jeûne poursuivant sa course devant lui est

arrivé au milieu du temps’ (Sauget 1986, 140).

Fig. 7: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 125v.

Fig. 8: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 168r.

manuscript cultures

CPG 5145.4

In psalmum 100

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 40, fols 125v–127v (Fig. 7)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/19, no. 71, fols 219b sqq.

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 73, fols 281a sqq.

BIBL: Wright 1871, 845b (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986,

140; Brock 1994–1995, 617 and 623.

TIT: . ܡܐܡܪܐ ܥܠ ܡܙܡܘܪܐ ܗܘ ܕܡܐܐ.ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ

ܫܒܚܘ ܠܡܪܝܐ ܟܠܗ ܐܪܥܐ

‘Of holy Mar John, sermon on Psalm 100, “Glorify the

Lord, all the earth”’

INC: ܥܘܠܘ.ܝܘܡܢܐ ܫܡܥܡܢܝܗܝ ܠܛܘܒܢܐ ܕܘܝܕ ܕܢܩܫ ܒܟܢܪܐ ܘܐܡܪ

̈

̈

ܕܗܢܝܐܢ

ܢܥܡܬܐ

.ܒܬ̈ܪܥܘܗܝ ܒܬܘܕܝܬܐ ܘܠܕ̈ܪܘܗܝ ܒܫܘܒܚܐ

̈ ܘܢܓܕܢ

̈ ܠܡܫܡܥܬܐ

ܠܫܡܘܥܘܗܝ ܠܒܘܣܡܐ ܕܪܘܚܐ

‘Aujourd’hui, nous avons entendu le bienheureux David

qui pince sa cithare et qui dit: Entrez dans ses portes

avec la louange et dans ses atriums avec la glorification

(Ps. 100:4). Les chants qui sont agréables à l’ouïe et qui

conduisent à la félicité de l’esprit (…)’ (Sauget 1986, 140).

CPG 5145.5

In diuitem cui uberes fructus ager attulit (Lk. 12:16)

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 54, fols 168r–171r (Fig. 8)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/19, no. 65, fols 203b sqq.

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 67, fols 260a sqq.

BIBL: Wright 1871, 846b (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986,

141; Brock 1994–1995, 617 and 623.

mc NO 13

�35

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܥܬܝܪܐ ܕܐܥܠܬ ܠܗ.ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ

ܐܪܥܗ ̈ܥܠܠܬܐ ̈ܣܓܝܐܬܐ

‘Of holy Mar John, sermon on the rich man whose field

bore much fruit’

̇

INC: ܚܘܒܬܗ ܕܬܘܕܝܬܐ

ܕܐܛܥܐ.ܡܣܟܢܘܬܗ ܕܠܫܢܝ ܐܠ ܫܒܩܐ ܠܝ

ܕܡܬܬܚܝܒ ܐܢܐ

‘La pauvreté de ma langue ne me permet pas de m’acquitter

de la dette d’action de grâces que j’ai contractée (…)’

(Sauget 1986, 141).

CPG 5145.6

De fine ieiunii et de paenitentia

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 55, fols 170v–173v (Fig. 9)

• (for a homily with a similar incipit, see: Damascus,

SOP, syr. 12/19, no. 79, fols 240a sqq. and Damascus,

SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 81, fols 309a sqq., cf. Brock 1994–

1995, 618 and 624)

BIBL Wright 1871, 846b (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986,

141.

TIT: ܘܥܠ. ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܫܘܠܡ ܨܘܡܐ.ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ

ܬܝܒܘܬܐ

‘Of holy Mar John, sermon on the end of Lent and on

repentance’

̈ ܟܕ ܠܘܬ ܫܘܠܡܗ ܕܨܘܡܐ ̇ܚܙܐ ܐܢܐ ܠܗܘܢ.ܚܒܝܒܝ

̈

INC: ܐܠܓܘܢܐ

.ܗܢܘܢ ܕܡܣܬܪܗܒܝܢ ܡܣܬܪܗܒ ܐܢܐ ܐܦ ܐܢܐ ܕܐܥܒܕܟܘܢ ̈ܚܠܝܨܐ

ܟܕ ܪܓܝܓ ܐܢܐ ܕܠܟܠܟܘܢ ܐܥܒܕ ̈ܫܩܝܠܝ ̈ܟܠܝܐܠ

‘(Mes bien aimés,) quand je vois, vers la fin du carême,

que les combats s’intensifient, je m’efforce moi aussi

de vous rendre forts, car je désire faire de vous tous des

(athlètes) couronnés’ (Sauget 1986, 141).

CPG 5145.7

In sabbatum annuntiationis (= sabbatum sanctum), de

baptismate, de latrone, et in illud: Comessationibus uacat et

luxuriae atque conuiuiis (Deut. 21:20)

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 85, fols 286v–290v (Fig. 10)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/19, no. 100, fols 299a sqq.

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 109, fols 416a sqq.

BIBL: Wright 1871, 848b (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986,

141; Brock 1994–1995, 619 and 625.

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܫܒܬܐ ܕܣܒܪܬܐ.ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ

̈ ܘܥܠ ̇ܗܝ ܕܐܠ ܢܗܘܐ.ܘܡܥܡܘܕܝܬܐ ܘܓܝܣܐ

ܐܣܘܛܐ ܘ̈ܪܘܝܐ

‘Of holy Mar John, sermon on the Saturday of Annunciation, on Baptism, on the Robber, and on (the words):

mc NO 13

Fig. 9: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 170v.

Fig. 10: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 286v.

manuscript cultures

�36

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

“Let there be no dissolute (ἄσωτος) nor drunkards”’

(Deut. 21:20)

̈

INC: . ܝܘܡܢܐ ܦܨܝܚܘܬܐ. ܝܘܡܢܐ ܦܘܪܩܢܐ.ܚܒܝܒܝ ܝܘܡܢܐ ܣܒܪܐ

ܝܘܡܢܐ ܥܐܕܐ ܘܥܕܥܐܕ ܡܠܟܐ

‘Mes bien aimés, aujourd’hui (c’est) l’espérance,

aujourd’hui le salut, aujourd’hui l’allégresse, aujourd’hui

la fête et la fête des fêtes du roi (…)’ (Sauget 1986, 141).

Fig. 11: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 300r.

Fig. 12: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 301v.

manuscript cultures

CPG 5145.8

Admonitio: unusquisque adulterium fugiat

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 90, fols 300r–301v (Fig. 11)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/19, no. 105, fols 318a sqq.

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 115, fols 444b sqq.

BIBL: Wright 1871, 849a (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986,

141; Brock 1994–1995, 619 and 625.

TIT: ܕܬ̈ܪܝܢ ܒܫܒܐ ܕܢܝܚܬܐ.ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ ܡܐܡܪܐ

ܘܕܢܥܪܘܩ ܐܢܫ ܡܢ ܙܢܝܘܬܐ.ܘܡܪܬܝܢܘܬܐ

‘Of holy Mar John, sermon on the Monday of the Week of

Rest and admonition to avoid adultery’

INC: ܕܘܐܠ ܕܢܬܥܗܕܘܢ ܐܦ.ܒܥܘܗܕܢܐ ܕܩܝܡܬܗ ܕܡܪܢ ܡܬܚܙܝܐ ܠܝ

̈

ܕܬܚܡܘ ܘܛܟܣܘ ̈ܥܐܕܐ ܕܒܗܘܢ ܡܬܒܣܡܝܢܢ.ܐܒܗܝܢ ̈ܩܕܝܫܐ

‘Durant la commémoraison de la résurrection de NotreSeigneur, il m’est apparu qu’il convient que nous

rappelions aussi nos saints pères qui ont institué et établi

les fêtes que nous célébrons’ (Sauget 1986, 141).

CPG 5145.9

Sine titulo, pro feria quarta post Pascha

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 91, fols 301v–303r (Fig. 12)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/19, no. 106, fols 319a sqq.

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 116, fols 446a sqq.

BIBL: Wright 1871, 849a (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986,

141–142; Brock 1994–1995, 619 and 625.

TIT: ܕܐܪܒܥܐ ܒܫܒܐ ܕܢܝܚܬܐ.ܕܝܠܗ ܕܡܠܦܢܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܝܣ

‘Of the same teacher Mar John, on the Wednesday of the

Week of Rest’

INC: ܗܘ ܦܬܓܡܐ ܕܢܒܝܐ. ܝܘܡܢܐ ܙܕܩ ܠܢ ܕܟܠܢ ܢܩܥܐ ܘܢܐܡ̈ܪ.̈ܚܒܝܒܝ

ܕܡܢܘ ܢܫܬܥܐ ܬܕܡܪܬܗ. ܟܕ ܡܫܒܚܝܢܢ ܠܡܪܝܐ ܐܠܗܢ ܘܡܙܥܩܝܢܢ.ܕܘܝܕ

ܕܡܪܝܐ

‘Mes bien aimés, aujourd’hui nous devons tous crier et

dire ce verset du prophète David, en glorifiant le Seigneur

notre Dieu et en proclamant: “Qui racontera les merveilles

du Seigneur ?” (Ps. 106:2)’ (Sauget 1986, 141–142).

mc NO 13

�37

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

CPG 5145.10

In sanctos martyres et confessores

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 102, fols 341r–343v

(Fig. 13)

• Berlin, SPK, Sachau 28/220, no. 31, fols 47r–v (inc.

mut.) (Fig. 14)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/19, no. 113, fols 340b sqq.

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 126, fols 484a sqq.

BIBL: Wright 1871, 850a (no. DCCCXXV); Sachau 1899,

120; Malki 1984; Brock 1985, 301; Brock 1994–1995,

619 and 625; Sauget 1985, 386; Sauget 1986, 142.

̈ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ.ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ

̈ ܣܗܕܐ ̈ܩܕܝܫܐ

TIT: ܘܡܘܕܝܢܐ

‘Of holy Mar John, sermon on the holy martyrs and

confessors’

̈ ܝܘܡܐ ܗܘ ܕܕܘܟܪܢܐ

̈

INC: ܘܕܡܘܕܝܢܐ ̇ܗܢܘܢ ܕܒܕܡܐ

ܕܣܗܕܐ

̈ (London, BL, Add. 12165)

ܕܩܛܠܝܗܘܢ ܪܫܝܡܝܢ ܕܘܟ̈ܪܢܝܗܘܢ

‘Ce jour est celui de la commémoraison des martyrs et des

confesseurs, ceux dont la mémoire est signée par le sang

de leur meurtre’ (Sauget 1986, 142).

CPG 5145.11

Ne tantum mortuos lugeamus et ne tantum sacrificia

offeramus pro defunctis, et in illud: Quod Iob sacrificia fecit

filiis suis

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 12165, no. 105, fols 350v–352r (Fig. 15)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 133, fols 484a sqq.

BIBL: Wright 1871, 850a (no. DCCCXXV); Sauget 1986,

142; Brock 1994–1995, 620 and 625.

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܥܠ ̇ܗܝ ܕܐܠ ܙܕܩ ܠܢ ܕܢܐܨܦ.ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ

ܘܕܠܘ ܫܚܝܡܐܝܬ ܡܬܩܪܒܝܢ ̈ܪܐܙܐ ܚܠܦ.ܕܒܟܝܐ ܥܠ ̈ܥܢܝܕܐ ܫܚܝܡܐܝܬ

̈

̈ ܘܕܐܝܘܒ ܚܠܦ ̈ܒܢܘܗܝ ܥܒܪ ܗܘܐ.ܥܢܝܕܐ

ܕܒܚܐ

‘Of holy Mar John, sermon on that we must not simply

worry about those who passed away, and that we must not

simply offer the Mysteries for the deceased, and that Job

too used to make sacrifices for his sons’

INC: ( ܐܠ ܗܟܝܠ ܫܚܝܡܐܝܬ ܢܬܐܒܠ ܥܠ ܗܢܘܢ ܕܡܝܬܝܢDamascus

12/20)

‘Ne pleurons donc pas simplement sur ceux qui sont

morts’ (Sauget 1986, 142).

Fig. 13: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 341r.

Fig. 14: Berlin, SPK, Sachau 28/220, fol. 47v.

mc NO 13

manuscript cultures

�38

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

• Birmingham, Cadbury Research Library, Mingana

Collection, Syr. 545, Bc

BIBL: Assemani and Assemani 1759 88; Assemani

1719, 308b (no. 8); Wright 1870, 240a (no. CCCVI);

Wright 1870, 245a (no. CCCVIII); Wright 1871, 827a (no.

DCCCXIV); Rilliet 1982, 582 (no. 19).

TIT: ܕܥܠ ܙܟܪܝܐ ܟܕ ܐܣܬܒܪ ܡܢ ܡܐܠܟܐ ܥܠ ܡܘܠܕܗ ܕܝܘܚܢܢ

‘In annunciationem Zachariae, quando annunciata ei fuit

ab Angelo Nativitas Johannis Baptistae’ (Assemani and

Assemani 1759, 88).

̈ ̈ܣܓܝܐܝܢ

INC: ܘܚܕ ܗܘ ܒܠܚܘܕ ܥܒܝܪ ܟܪܘܙܐ ܠܕܢܚܗ.ܟܘܟܒܐ ܒܪܩܝܥܐ

̈ .ܕܐܝܡܡܐ

̈ ܘܣܓܝܐܐ

. ܘܝܘܚܢܢ ܗܘ ܡܥܡܕܢܐ ܐܟܪܙ.ܢܒܝܐ ܗܘܘ ܒܥܠܡܐ

̈

ܕܒܪܝܬܐ

( ܕܗܐ ܕܢܚ ܡܫܝܚܐ ܡܪܐLondon, BL, Add. 14515)

‘Plures sunt stellae in firmamento, una autem effecta

est praedicatrix ortus diei; plures etiam fuere in mundo

Prophetae, Johannes vero ille Baptista praedicavit,

quod ecce ortus est Christus illuminator creaturarum’

(Assemani and Assemani 1759, 88).

Fig. 15: London, BL, Add. 12165, fol. 350v.

CPG 5145.12

In dominicam resurrectionis

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 14727, no. 8q, fols 130r–133v

• Birmingham, Cadbury Research Library, Mingana

Collection, Syr. 545, Ea

BIBL: Wright 1871, 889b (no. DCCCXLVIII); Rilliet

1982, 582 (no. 18).

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܚܕܒܫܒܐ ܕܩܝܡܬܐ

‘Sermon on the Sunday of Resurrection’

̇

̇ ܢܗܝܪܐ ܘܦܨܝܚܐ ܘܚܕܝܐ.̈ܚܒܝܒܝ

INC: ܕܟܠܗ

ܕܒܪܘܝܐ.ܟܠܗ ܒܪܝܬܐ

ܩܡ ܡܢ ܩܒܪܐ ܒܬܫܒܘܚܬܐ.ܒܪܝܬܐ

‘Mes bien aimés, aujourd’hui toute la création resplendit,

se réjouit et exulte de joie, car le créateur de toute créature

se lève de la tombe dans la gloire’ (Rilliet 1982, 582).

CPG 5145.13

In annuntiationem Zachariae factam

MSS:

• London, BL, Add. 14515, no. 1, fols 2v–6r

• London, BL, Add. 14516, no. 1, fols 1r–4r

• London, BL, Add. 14725, no. 1a, fols 2v–4v

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 117, no. 10, fols 28rb–29rc

manuscript cultures

Texts not included in CPG:

[1]

In ieiunium

MS: Vatican City, BAV, BAV, Vat. sir. 368, no. 10, fols

35ra–38ra

BIBL: Assemani and Assemani 1831, 42 (no. 9); Sauget

1961, 404.

TIT: ܬܘܒ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܨܘܡܐ ܩܕܝܫܐ ܕܐ̈ܪܒܥܝܢ ܕܐܡܝܪ ܠܩܕܝܫܐ

ܝܘܐܢܝܣ ܐܦܝܣܩܦܐ ܕܩܘܣܛܢܛܝܢܘ ܦܘܠܝܣ

‘Again, sermon on the holy Lent of forty days, pronounced

by St John, bishop of Constantinople’

INC: ܝܬܝܪ ܡܢ ܫܝܦܘܪܐ ܒܪܬ ܩܠܝ ܠܥܠ ܐܪܝܡ

‘Higher than a trumpet I raise my voice’.

[2]

In Lazarum, quem dominus resuscitavit

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 368, no. 15, fols 62ra–63rb

(inc. mut.)

BIBL: Assemani and Assemani 1831, 42 (no. 14); Sauget

1961, 405.

TIT: —

INC: ( ܥܠ ܩܒܪܐ ܘܚܙܘ ܫܠܕܗ ܕܡܝܬܐ...)

‘(...) to the tomb and they saw the body of the dead one’

̈ ܠܟܠܗܘܢ

DES: ܝܠܕܘܗܝ ܕܐܕܡ ܡܐ ܕܕܢܚ ܒܫܘܒܚܗ

‘to all of you, children of Adam, when He shines in His

glory’

mc NO 13

�KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

EXPL: ܫܠܡ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܠܥܙܪ ̇ܗܘ ܕܢܚܡ ܡܪܢ ܕܐܡܝܪ ܠܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ

ܝܘܐܢܝܣ

‘Here ends the sermon on Lazarus whom our Lord

resurrected, pronounced by the holy Mar John’.

[3]

In ascensionem

MSS:

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 368, no. 32, fols 121ra–122va

(lac.);

• London, BL, Add. 14605 (no. DCCLV), fols 1v–5v

BIBL: Assemani and Assemani 1831, 42 (no. 29); Wright

1871, 715b; Sauget 1961, 409.

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܬܪܝܢ ܕܥܠ. ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܝܘܐܢܝܣ.ܬܘܒ ܕܝܠܗ ܟܕ ܕܝܠܗ

ܣܘܠܩܐ

‘Again of the same, the holy Mar John, the second homily

on Ascension’

̈ ܒܟܠܙܒܢ ܡܢ ܟܝܢܐ ܐܠܗܝܐ ܢܫܬܒܚ ܡܢ

INC: ܐܢܫܐ

‘In all times the godly nature is praised by humans’.

[4]

In apostolos

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 368, no. 34, fols 125rb–

126rb (lac.)

BIBL: Assemani and Assemani 1831, 42 (no. 31); Sauget

1961, 409.

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ̈ܫܠܝܚܐ. ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܝܘܐܢܝܣ.ܬܘܒ ܕܝܠܗ ܟܕ ܕܝܠܗ

̈

ܩܕܝܫܐ

‘Again of the same, the holy Mar John, sermon on the

holy Apostles’

̈ ܡܨܝܕܬܐ

̈ ̇ܚܙܐ ܐܢܐ

̈

INC: ܕܥܕܬܐ ܝܘܡܢܐ

ܕܡܠܝܢ

‘I see that the nets of the churches are full today’.

[5]

Homilia, qua ostendit honorandam esse diem dominicam

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 368, no. 36, fols 129va–

132va

BIBL: Assemani and Assemani 1831, 42–43 (no. 33);

Sauget 1961, 409

TIT: ܬܘܒ ܕܝܠܗ ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܝܘܐܢܝܣ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܡܚܙܐ ܕܢܝܩܪ ܚܕ ܒܫܒܐ

‘Again, of the same St John, sermon which demonstrates

that we ought to venerate the Sunday’

̈

INC: ܕܥܐܕܐ

ܙܥܘܪ ܥܐܕܢ ܘܣܓܝ ܙܥܘܕ ܒܦܚܡܐ

‘Our holiday is small, and very small in comparison with

(other) holidays’.

mc NO 13

39

[6]

In laudem martyrum I

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 368, no. 38, fols 136ra–137va

BIBL: Assemani and Assemani 1831, 43 (no. 35); Sauget

1961, 410.

TIT: ܬܘܒ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܡܪܝ ܝܘܐܢܝܘ ܟܪܘܣܘܣܛܡܣ ܕܥܠ ܩܘܠܣܐ

̈

ܕܣܗܕܐ

‘Again, sermon of Mar John Chrysostom (krwswsṭms) on

praising the martyrs’

̈

INC:ܕܣܗܕܐ ܕܐܦ ܡܢ ܪܘܚܩܐ ܢܟܢܫܘܢ ܠܢ

ܚܕ ܬܘܪܨܐ ܐܦ ܗܢܐ

‘Receive this admonition about martyrs, too, and let us

gather from far, too’.

[7]

In laudem martyrum II

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 368, no. 39, fols 137va–

139vb

BIBL: Assemani and Assemani 1831, 43 (no. 36); Sauget

1961, 410.

TIT: ܬܘܒ ܕܝܠܗ ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܝܘܐܢܝܣ ܟܪܘܣܣܛܡܘܣ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܬܪܝܢ ܕܥܠ

̈

ܣܗܕܐ

‘Again, of the same St John Chrysostom (krwssṭmws),

second sermon on martyrs’

INC: ܬܘܒ ܠܥܐܕܐ ܗܢܐ ܟܗܢܝܐ ܘܪܚܝܡܐ ܐܝܬܝ ܠܢ ܐܠܗܐ

‘God brought us again unto this priestly and pleasant

holiday’.

[8]

In apostolum Paulum

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 368, no. 41, fols 146ra–

149vb

BIBL: Assemani and Assemani 1831, 43 (no. 38); Sauget

1961, 410–411.

TIT: ܬܘܒ ܕܝܠܗ ܟܕ ܕܝܠܗ ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܝܘܐܢܝܣ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܦܘܠܣ

ܫܠܝܚܐ

‘Again, of the same, the holy Mar John, sermon on saint

Paul’

̈

INC: ܒܬܟܬܘܫܐ ܕܝܠܗܘܢ

̈ܨܝܕܐ ܠܢ ܐܬܡܠܝ

‘He accomplished contests for us in their competitions’.

[9]

In poenitentiam

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 368, no. 53, fols 194ra–

197ra

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 413.

manuscript cultures

�40

TIT: ܬܘܒ ܕܝܠܗ ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܝܘܐܢܝܣ ܟܪܘܣܘܣܛܡܣ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ

ܬܝܒܘܬܐ

‘Again, of the same St John Chrysostom (krwswsṭms),

sermon on repentance’

INC: ܙܕܩ ܬܢܢ ܠܡܬܬܢܚܘ ܘܠܡܬܐܒܠܘ ܪܘܪܒܐܝܬ

‘Here it is necessary to wail and to weep a lot’.

[10]

In diem manifestationis Domini

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 8, fols 29vb–31rb

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 415.

TIT: ... ܥܠ... ( ܬܘܒpoorly legible in the reproduction)

INC: ܒܝܘܡܐ ܕܒܝܬ ܝܠܕܐ ܕܦܘܪܩܢ ܐܦ ܐܠܗܘܬܐ ܫܪܝܐ ܗܘܬ

ܒܦܓܪܐ

‘On the day of the birth of our Saviour there was true

... divinity in the flesh, too’.

[11]

In baptismum Domini et in pugnam contra diabolum

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 9, fols 31rb–33ra

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 415.

TIT: ܕܝܠܗ ܟܕ ܕܝܠܗ ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܟܪܘܣܛܘܡܘܣ ܥܠ ܥܡܕܐ ܬܘܒ

( ܕܡܪܢpoorly legible in the reproduction)

‘Again of the same, holy Mar Chrysostom, on the Baptism

of our Lord and …’

INC: ܬܘ ܢܬܒܣܡ ܡܢ ܐܓܢܐ ܪܘܚܢܝܬܐ ܕܐܬܬܣܝܡܬ ܩܕܡܝܢ

‘Come, rejoice at the spiritual efforts which I left behind’.

[12]

In manifestationem Domini

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 11, fols 36rb–39ra

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 416.

TIT: ܡܪܢ... ( ܬܘܒ ܕܝܠܗ ܟܕ ܕܝܠܗ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܝܣ ܕܥܠ ܕܢܚܐpoorly

legible in the reproduction)

‘Again of the same, holy Mar John, on the Manifestation

… of our Lord’

INC: ܫܡܥܬܘܢܝܗܝ ܠܫܠܝܚܐ ܕܡܟܪܙ ܠܢ ܝܘܡܢܐ ܥܠ ܡܘܗܒܬܐ

‘Listen to the apostle who preaches about the liberality’.

[13]

De introitu Domini in templum I

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 13, fols 41vb–45rb

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 416.

TIT: ܩܕܝܫܐ... ܡܐܡܪܐ... (poorly legible in the reproduction)

‘The homily (of) … saint …’

̈

INC: ܬܫܒܚܬܗ

ܚܒܝܒܝ ܡܢܘ ܢܫܬܥܐ ܬܕܡ̈ܪܬܗ ܕܡܪܝܐ ܟܠܗܝܢ

manuscript cultures

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

‘My beloved, who can narrate the miracles of the Lord

(and) all His glorious (deeds)?’.

[14]

De introitu Domini in templum II

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 14, fols 47ra–48vb

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 417.

TIT: … (not legible in the reproduction)

‘Sur l’entrée du seigneur au Temple’ (Sauget 1961, 417)

INC: ܐܦ ܝܘܡܢܐ ܬܘܒ ܥܐܕܐ ܐܝܬܘܗܝ ܡܪܐܢܝܐ

‘Today, too, it is a feast of the Lord’.

[15]

De ieiunio

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 20, fols 68rb–74ra

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 418.

TIT: … (not legible in the reproduction)

‘Sur le jeûne’ (Sauget 1961, 418)

INC: ܚܒܝܒܝ ܙܒܢܐ ܗܘ ܡܟܝܠ (؟) ܘܫܥܬܐ ܗܝ ܕܢܬܬܥܝܪ

‘My beloved, it is the time therefore (?) and it is the hour

to get awake’.

[16]

In ieiunium et in Ps. 19, 17

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 21, fols 74ra–75vb

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 418.

TIT: ... ܕܥܠ...( ܬܘܒ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܐܚܪܢܐ ܕܡܪܝ ܐܝpoorly legible in

the reproduction)

‘Now, the second homily of Mar … on …’

INC: ܨܘܡܐ ܚܘܛܪܐ ܫܦܝܪܐ ܐܝܬܘܗܝ

‘Fasting is a beautiful stick’.

[17]

De ieiunio et de gratia

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 22, fols 75vb–77va

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 418.

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܥܠ ܨܘܡܐ ܘܡܪܚܡܢܘܬܐ... ܕܝܠܗ ܟܕ ܕܝܠܗ ܩܕܝܫܐ ܝܘܐܢܣ

(poorly legible in the reproduction)

‘Of the same saint John, … homily on Lent and on charity’

INC: ܛܘܒܐ ̇ܝܗܒ ܐܢܐ ܠܟܠܟܘܢ ܡܛܠ ܪܚܡܬ ܐܠܗܐ

‘I call all of you, blessed ones, because of the love of God’.

[18]

In annuntiationem

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 27, fols 92ra–93rb

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 419.

mc NO 13

�KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

TIT: ܬܘܒ ܕܝܠܗ ܟܕ ܕܝܠܗ ܥܠ ܣܒܪܐ

‘Now, of the same, on Annunciation’

INC: ܠܒܛܘܠܬܐ ܗܟܝܠ ܡܢ ܕܡܩܠܣ ܠܡܫܝܚܐ ܡܫܒܚ

‘Now, who praises the Virgin, glorifies the Christ’.

[19*]

In feriam quintam35

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 32, fols 101ra–

106vb (inc. mut.)

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 420.

TIT: —

INC: ( ܘܡܛܠܠܝܢ ܥܠܘܗܝ ܟ̈ܪܘܒܐ ܕܫܘܒܚܐ...)

‘(...) and the Cherubim cover him with glory’

DES: ܐܐܠ ܚܕܐ ܗܘ ܒܫܢܬܐ ܒܠܚܘܕ ܓܝܪ ܒܦܪܝܫܘܬ ܝܘܡܐ

‘But once a year (and) only with a distinction of the days’

EXPL: ]ܫܠܡ] ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܝܘܡܐ ܩܕܝܫܐ ܕܚܡܫܐ ܒܫܒܐ ܕܪܐܙܐ

‘Here ends the sermon of the holy fifth day of the Week

of Mysteries’.

[20]

In crucifixionem Domini

MSS:

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 36, fols 117va–b

(des. mut.)

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 106, fols 405a sqq.

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 420; Brock 1994–1995, 619 and 624.

TIT: )...( ܕ[ܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ] ܝܘܐܢܝܣ ܕܦܘܡܐ ܕܕܗܒܐ.ܕܝܠܗ ܟܕ ܕܝܠܗ

ܡܐܡܪܐ ܥܠ ܨܠܝܒܘܬܗ ܕܡܪܢ

‘Of the same, (holy Mar) John Chrysostom, (…) sermon

on the Crucifixion of the Lord’

INC: ܚܒܝܒܝ ܒܟܠܙܒܢ ܚܫܗ ܕܦܪܘܩܢ ܘܨܠܝܒܗ ܡܢܢ ܡܫܬܒܚ

‘My beloved, in all times the Passion of our Saviour and

His Cross are praised by us’.

[21]

In resurrectionem Domini

MSS:

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 369, no. 40, fols 126rb–128va

(lac.)

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 253, no. 33, fols 137rb–144rb

BIBL: Sauget 1961, 421; Sauget 1968, 338–339.

35

It is not clear why Sauget ascribed this fragmentary text to Chrysostom;

we find no explicit mention of ‘John’ or ‘Chrysostom’ in the only manuscript

that transmits it. We decided to include it in our list nevertheless, numbered

with an asterisk, leaving further investigations on its authorship open.

mc NO 13

41

TIT: ܬܘܒ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܝܣ ܐܦܝܣܟܘܦܐ

ܕܟܣܛܢܛܝܢܦܘܠܝܣ ܕܥܠ ܩܝܡܬܐ ܕܡܪܢ

‘Now, the homily of holy Mar John, bishop of Constantinople, on the Resurrection of our Lord’ (Vat. sir. 369)

̈ ܘܒܦܘܡܝܗܝܢ

̈

̈ ܩܛܦܢ

INC (1): ܗܒܒܐ

ܕܒܘ̈ܪܝܬܐ ܥܠ ܥܩ̈ܪܐ ܟܕ ܫܟܢܢ

(Vat. sir. 369)

̈ ܘܒܦܘܡܝܗܝܢ

̈ ܩܛܦܢ

̈

INC (2): ܗܒܒܐ

ܕܒܘ̈ܪܝܬܐ ܡܐ ܕܥܠ ܥܩ̈ܪܐ ܫܟܢܢ

(Vat. sir. 253)

‘Apes quando supra radices se ponunt et oribus suis

colligunt flores’ (Sauget 1968, 339).

[22]

De Cruce et latrone

MS: Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 253, no. 27, fols 75rb–77va

BIBL: Sauget 1968, 335.

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܐܝܘܐܢܝܣ ܕܥܠ ܨܠܝܒܐ ܘܓܝܣܐ

‘Sermo sancti Iohannis de Cruce et Latrone’ (Sauget

1968, 335)

INC: The beginning is poorly readable: ( ܥܠ ̇ܗܢܘܢ ܕܡܢܗ...)

̈

̈

ܠܨܒܘܬܐ

ܐܢܝܢ

ܡܚܕܐ ܓܝܪ ܕܐܬܚܙܝ ܒܥܠܡܐ ܫܚܠܦ.ܥܕܩܘ ܗܘܘ

ܠܡܘܬܪܘܬܐ

‘(...) super eos qui ab eo effugerant. Simulatque enim

apparuit in mundo permutavit illa in voluntates ad

abundantiam’ (Sauget 1968, 335)

DES: ܢܨܐܠ ܗܟܝܠ ܐܦ ܚܢܢ ܕܥܡ ܓܝܣܐ ܢܗܘܐ ܘܢܐܡܪ ܥܡܗ

ܐܡܝܢ. ܕܠܗ ܫܘܒܚܐ ܠܥܠܡ ܥܠܡܝܢ.ܥܡܪܢ ܕܐܬܟܪܝܢܝ ܒܡܠܟܘܬܟ

‘Rogemus ergo etiam nos ut cum latrone simus, et dicamus

cum eo domino nostro: memento mei in tuo regno. Quia ei

Gloria in saecula saeculorum. Amen’ (Sauget 1968, 335).

[23]

In sanctum Stephanum

MSS:

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 253, no. 40, fols 165ra–vb

(inc. mut.)

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 117, n. 44, fols 116va–117rb

BIBL: Sauget 1968, 342; Assemani 1719, 91–92.

TIT: ܬܘܒ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܢܢܝܣ ܕܥܠ ܩܕܝܫܐ ܘܣܗܕܐ

̈

ܕܣܗܕܐ

ܐܣܛܦܢܘܣ ܒܘܟܪܐ

‘Again a sermon of the holy Mar John on the holy martyr

Stephen, the first-born of the martyrs’

̈

INC: ܗܢܐ ܕܐܝܬܘܗܝ ܒܥܕܬܐ.ܕܢܨܚܢܘܗܝ ܕܣܗܕܐ ܣܛܦܢܘܣ

ܫܘܦܪܐ

ܩܕܡܝܬܐ

‘Pulchritudo triumphorum Stephani Martyris, primaevae

Ecclesiae’ (Assemani 1719, 91–2).

manuscript cultures

�42

[24]

De deipara

MSS:

• Berlin, SPK, Sachau 28/220, no. 11, fols 12vb, 14r–v, 13ra

(lac.) (Fig. 16)

• London, BL, Add. 14515, fols 49r–52v

• Damascus, SOP, syr. 12/20, no. 122, fols 468b sqq.

BIBL: Sachau 1899, 115–116; Wright 1870, 241a (no.

CCCVI); Malki 1984; Brock 1985, 299; Sauget 1985,

378–9; Brock 1994–1995, 619 and 625.

TIT: ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܡܪܝ ܐܝܘܐܢܢܝܣ

‘Homily of the holy Mar John’

INC: ܐܙܕܡܢܬܘܢ

ܝܘܡܢܐ.ܠܥܐܕܐ ܚܕܘܬܢܝܐ ܕܒܛܘܠܬܐ ̣ܝܠܕܬ ܐܠܗܐ

̣

̇

̇

̈

ܕܝܠܗ

ܠܥܘܣܕܢܐ.ܐܬܛܝܒܬܘܢ

ܕܝܠܕܗ ܡܝܩܪܐ

. ܘܠܕܘܟܪܢܐ.ܚܒܝܒܝ

̣

ܘܠܚܗܐ ܪܘܚܢܝܐ ܘܝܬܝܪ ܡܘܬܪܢܐ.ܪܚ ̣ܝܡܐ ܐܬ ̣ܝܬܘܢ

‘Aujourd’hui, bien aimés, vous avez été invités à la fête

joyeuse de la vierge Théotokos et vous vous êtes préparés

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

[25]

In Pentecosten

MSS:

• Göttingen, State and University Library, MS syr. 18,

fols 1r–2v

• Vatican City, BAV, Vat. sir. 627, fols 1r–2v

BIBL: Géhin 2017, 887–888 (no. Q1).

TIT: ܬܘܒ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܩܕܝܫܐ ܝܘܚܢܢ ܦܘܡܐ ܕܕܗܒܐ ܕܥܠ ܚܕ ܒܫܒܐ

ܕܦܢܛܝܩܘܣܛܐ

‘Now, the homily of Saint John Chrysostom on the

Sunday of Pentecost’

̈

INC: ܚܒܝܒܝ ܕܘܝܕ ܪܡ ܩܐܠ ܘܫܝܦܘܪܐ ܕܢܒܝܘܬܐ ܡܙܥܩ ܝܘܡܢܐ

ܒܢܒܝܘܬܗ ܠܘܬ ܐܠܗܐ ܘܐܡܪ

‘Mes bien aimés, David a élevé la voix et la trompette

de la prophétie a retenti aujourd’hui dans sa prophétie

jusqu’à Dieu’ (Géhin 2017, 888).

à la mémoire de son enfantement magnifique’ (Sauget

1985, 379).

manuscript cultures

mc NO 13

�KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

43

Fig. 16: Berlin, SPK, Sachau 28/220, fol. 12v.

mc NO 13

manuscript cultures

�KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

44

4. Incipits

( )...ܘܡܛܠܠܝܢ ܥܠܘܗܝ ܟ̈ܪܘܒܐ ܕܫܘܒܚܐ

̈

( )...ܥܠ ̇ܗܢܘܢ ܕܡܢܗ ܥܕܩܘ ܗܘܘ .ܡܚܕܐ ܓܝܪ ܕܐܬܚܙܝ ܒܥܠܡܐ ܫܚܠܦ ̈

ܠܨܒܘܬܐ ܠܡܘܬܪܘܬܐ

ܐܢܝܢ

( )...ܥܠ ܩܒܪܐ ܘܚܙܘ ܫܠܕܗ ܕܡܝܬܐ

ܐܓܘܢܗ ܕܨܘܡܐ ܟܕ ܡܫܬܘܫܛ ܒܪܗܛܗ ܠܩܕܡܘܗ .ܡܢܥ ܠܗ ܠܡܨܥܬܐ ܕܙܒܢܐ

]*[19

][22

][2

CPG 5145.3

ܐܦ ܝܘܡܢܐ ܬܘܒ ܥܐܕܐ ܐܝܬܘܗܝ ܡܪܐܢܝܐ

][14

ܒܝܘܡܐ ܕܒܝܬ ܝܠܕܐ ܕܦܘܪܩܢ ܐܦ ܐܠܗܘܬܐ ܫܪܝܐ ܗܘܬ ܒܦܓܪܐ

][10

ܒܟܠܙܒܢ ܡܢ ܟܝܢܐ ܐܠܗܝܐ ܢܫܬܒܚ ܡܢ ̈

ܐܢܫܐ

ܒܥܐܕܐ ܪܒܐ ܟܢܫܢܢ ܝܘܡܢܐ ܕܢܬܒܣܡ .ܥܐܕܐ ܗܘ ܓܝܪ ܫܪܝܪܐ ܕܢܦܫܐ .ܡܐ ܕܒܡܝܬ̈ܪܬܐ ̇ܩܪܒܐ

̈

ܐܒܗܝܢ ̈ܩܕܝܫܐ .ܕܬܚܡܘ ܘܛܟܣܘ ̈ܥܐܕܐ ܕܒܗܘܢ

ܒܥܘܗܕܢܐ ܕܩܝܡܬܗ ܕܡܪܢ ܡܬܚܙܝܐ ܠܝ .ܕܘܐܠ ܕܢܬܥܗܕܘܢ ܐܦ

ܡܬܒܣܡܝܢܢ

][3

CPG 5145.1

CPG 5145.8

ܘܒܦܘܡܝܗܝܢ ̈

ܩܛܦܢ ̈

̈

ܗܒܒܐ

ܕܒܘ̈ܪܝܬܐ ܡܐ ܕܥܠ ܥܩ̈ܪܐ ܫܟܢܢ

][21

ܘܒܦܘܡܝܗܝܢ ̈

̈

ܩܛܦܢ ̈

ܗܒܒܐ

ܕܒܘ̈ܪܝܬܐ ܥܠ ܥܩ̈ܪܐ ܟܕ ܫܟܢܢ

][21

ܙܕܩ ܬܢܢ ܠܡܬܬܢܚܘ ܘܠܡܬܐܒܠܘ ܪܘܪܒܐܝܬ

][9

̈

ܕܥܐܕܐ

ܙܥܘܪ ܥܐܕܢ ܘܣܓܝ ܙܥܘܕ ܒܦܚܡܐ

][5

ܚܒܝܒܝ ܒܟܠܙܒܢ ܚܫܗ ܕܦܪܘܩܢ ܘܨܠܝܒܗ ܡܢ ܡܫܬܒܚ

][20

̈

ܚܒܝܒܝ ܕܘܝܕ ܪܡ ܩܐܠ ܘܫܝܦܘܪܐ ܕܢܒܝܘܬܐ ܡܙܥܩ ܝܘܡܢܐ ܒܢܒܝܘܬܗ ܠܘܬ ܐܠܗܐ ܘܐܡܪ

][25

ܚܒܝܒܝ ܙܒܢܐ ܗܘ ܡܟܝܠ ܘܫܥܬܐ ܗܝ ܕܢܬܬܥܝܪ

][15

̈ܚܒܝܒܝ ܝܘܡܢܐ ܙܕܩ ܠܢ ܕܟܠܢ ܢܩܥܐ ܘܢܐܡ̈ܪ .ܗܘ ܦܬܓܡܐ ܕܢܒܝܐ ܕܘܝܕ .ܟܕ ܡܫܒܚܝܢܢ ܠܡܪܝܐ ܐܠܗܢ ܘܡܙܥܩܝܢܢ .ܕܡܢܘ

ܢܫܬܥܐ ܬܕܡܪܬܗ ܕܡܪܝܐ

CPG 5145.9

̈

ܚܒܝܒܝ ܝܘܡܢܐ ܣܒܪܐ .ܝܘܡܢܐ ܦܘܪܩܢܐ .ܝܘܡܢܐ ܦܨܝܚܘܬܐ .ܝܘܡܢܐ ܥܐܕܐ ܘܥܕܥܐܕ ܡܠܟܐ

CPG 5145.7

ܚܒܝܒܝ ܟܕ ܠܘܬ ܫܘܠܡܗ ܕܨܘܡܐ ̇ܚܙܐ ܐܢܐ ܠܗܘܢ ̈

̈

ܐܠܓܘܢܐ ܗܢܘܢ ܕܡܣܬܪܗܒܝܢ ܡܣܬܪܗܒ ܐܢܐ ܐܦ ܐܢܐ

̈

̈

̈

ܕܐܥܒܕܟܘܢ ܚܠܝܨܐ .ܟܕ ܪܓܝܓ ܐܢܐܕܠܟܠܟܘܢ ܐܥܒܕ ܫܩܝܠܝ ܟܠܝܐܠ

̈

ܬܫܒܚܬܗ

ܚܒܝܒܝ ܡܢܘ ܢܫܬܥܐ ܬܕܡ̈ܪܬܗ ܕܡܪܝܐ ܟܠܗܝܢ

̇

̈ܚܒܝܒܝ ܢܗܝܪܐ ܘܦܨܝܚܐ ܘܚܕܝܐ ̇

ܕܟܠܗ ܒܪܝܬܐ .ܩܡ ܡܢ ܩܒܪܐ ܒܬܫܒܘܚܬܐ

ܟܠܗ ܒܪܝܬܐ .ܕܒܪܘܝܐ

CPG 5145.6

][13

CPG 5145.12

̈

ܕܣܗܕܐ ܕܐܦ ܡܢ ܪܘܚܩܐ ܢܟܢܫܘܢ ܠܢ

ܚܕ ܬܘܪܨܐ ܐܦ ܗܢܐ

][6

ܡܨܝܕܬܐ ̈

̇ܚܙܐ ܐܢܐ ̈

̈

ܕܥܕܬܐ ܝܘܡܢܐ

ܕܡܠܝܢ

][4

ܛܘܒܐ ̇ܝܗܒ ܐܢܐ ܠܟܠܟܘܢ ܡܛܠ ܪܚܡܬ ܐܠܗܐ

ܝܘܡܐ ܗܘ ܕܕܘܟܪܢܐ ̈

ܘܕܡܘܕܝܢܐ ̇ܗܢܘܢ ܕܒܕܡܐ ̈

ܕܣܗܕܐ ̈

ܕܩܛܠܝܗܘܢ ܪܫܝܡܝܢ ܕܘܟ̈ܪܢܝܗܘܢ

ܝܘܡܢܐ ܫܡܥܡܢܝܗܝ ܠܛܘܒܢܐ ܕܘܝܕ ܕܢܩܫ ܒܟܢܪܐ ܘܐܡܪ .ܥܘܠܘ ܒܬ̈ܪܥܘܗܝ ܒܬܘܕܝܬܐ ܘܠܕ̈ܪܘܗܝ ܒܫܘܒܚܐ̈ .

ܢܥܡܬܐ

̈

ܘܢܓܕܢ ̈

ܕܗܢܝܐܢ ܠܡܫܡܥܬܐ ̈

ܠܫܡܘܥܘܗܝ ܠܒܘܣܡܐ ܕܪܘܚܐ

ܝܬܝܪ ܡܢ ܫܝܦܘܪܐ ܒܪܬ ܩܠܝ ܠܥܠ ܐܪܝܡ

ܐܠ ܗܟܝܠ ܫܚܝܡܐܝܬ ܢܬܐܒܠ ܥܠ ܗܢܘܢ ܕܡܝܬܝܢ

ܠܒܛܘܠܬܐ ܗܟܝܠ ܡܢ ܕܡܩܠܣ ܠܡܫܝܚܐ ܡܫܒܚ

mc NO 13

][17

CPG 5145.10

CPG 5145.4

][1

CPG 5145.11

][18

manuscript cultures

�45

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

[24]

̇

̈ ܐܙܕܡܢܬܘܢ

.ܐܬܛܝܒܬܘܢ

ܕܝܠܕܗ ܡܝܩܪܐ

. ܘܠܕܘܟܪܢܐ.ܚܒܝܒܝ

ܝܘܡܢܐ.ܠܥܐܕܐ ܚܕܘܬܢܝܐ ܕܒܛܘܠܬܐ ̣ܝܠܕܬ ܐܠܗܐ

̣

̣

̇ ܠܥܘܣܕܢܐ

ܘܠܚܗܐ ܪܘܚܢܝܐ ܘܝܬܝܪ ܡܘܬܪܢܐ.ܕܝܠܗ ܪܚ ̣ܝܡܐ ܐܬ ̣ܝܬܘܢ

CPG 5145.2

ܐܡܪ ܗܘܝܬ ܕܙܒܢܐ ܗܘ ܕܬܝܒܘܬܐ.ܡܢ ܩܕܡ ܝܘܡܐ ܟܕ ܥܡܟܘܢ ̇ܡܡܠܠ ܗܘܝܬ ܥܠ ܨܘܡܐ

CPG 5145.5

̇

ܚܘܒܬܗ ܕܬܘܕܝܬܐ ܕܡܬܬܚܝܒ ܐܢܐ

ܕܐܛܥܐ.ܡܣܟܢܘܬܗ ܕܠܫܢܝ ܐܠ ܫܒܩܐ ܠܝ

CPG 5145.13

̈ ̈ܣܓܝܐܝܢ

̈ . ܘܚܕ ܗܘ ܒܠܚܘܕ ܥܒܝܪ ܟܪܘܙܐ ܠܕܢܚܗ ܕܐܝܡܡܐ.ܟܘܟܒܐ ܒܪܩܝܥܐ

̈ ܘܣܓܝܐܐ

ܘܝܘܚܢܢ.ܢܒܝܐ ܗܘܘ ܒܥܠܡܐ

̈

ܕܒܪܝܬܐ

ܕܗܐ ܕܢܚ ܡܫܝܚܐ ܡܪܐ.ܗܘ ܡܥܡܕܢܐ ܐܟܪܙ

[16]

[8]

ܨܘܡܐ ܚܘܛܪܐ ܫܦܝܪܐ ܐܝܬܘܗܝ

̈

ܒܬܟܬܘܫܐ ܕܝܠܗܘܢ

ܨܝܕܐ ܠܢ ܐܬܡܠܝ

[23]

̈

ܗܢܐ ܕܐܝܬܘܗܝ ܒܥܕܬܐ ܩܕܡܝܬܐ.ܕܢܨܚܢܘܗܝ ܕܣܗܕܐ ܣܛܦܢܘܣ

ܫܘܦܪܐ

[12]

ܫܡܥܬܘܢܝܗܝ ܠܫܠܝܚܐ ܕܡܟܪܙ ܠܢ ܝܘܡܢܐ ܥܠ ܡܘܗܒܬܐ

[11]

ܬܘ ܢܬܒܣܡ ܡܢ ܐܓܢܐ ܪܘܚܢܝܬܐ ܕܐܬܬܣܝܡܬ ܩܕܡܝܢ

[7]

ܬܘܒ ܠܥܐܕܐ ܗܢܐ ܟܗܢܝܐ ܘܪܚܝܡܐ ܐܝܬܝ ܠܢ ܐܠܗܐ

REFERENCES

Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1719), Bibliotheca Orientalis

Clementino-Vaticana (…), Tomus primus: De scriptoribus Syris

orthodoxis (Rome: Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide).

Assemani, Stefano Evodio, and Giuseppe Simone Assemani (1759),

Bibliothecae Apostolicae Vaticanae codicum manuscriptorum

catalogus… Partis primae tomus tertius complectens reliquos

codices Chaldaicos sive Syriacos (Rome: Typographia linguarum

orientalium).

—— and —— (1831), ‘Codices chaldaici sive syriaci Vaticani

Assemaniani’, in Angelo Mai, Scriptorum veterum nova collectio

e Vaticanis codicibus edita, vol.5.[2.] (Rome: Typis Vaticanis),

1–82.

Baumstark, Anton (1910), Festbrevier und Kirchenjahr der

syrischen Jakobiten: Eine liturgiegeschichtliche Vorarbeit

(Paderborn: F. Schöningh; Studien zur Geschichte und Kultur

des Altertums, III/3–5).

—— (1911), ‘Die liturgischen Handschriften des Jakobitischen

Markusklosters in Jerusalem’, Oriens christianus, n.s. 1: 103–

115, 286–314.

Brock, Sebastian (1985), Review of Malki 1984, Journal of Semitic

Studies, 30: 298–301.

Brock, Sebastian (2007), ‘L’apport des pères grecs à la littérature

syriaque’, in Andrea Schmidt and Dominique Gonnet (eds), Les

Pères grecs dans la tradition syriaque (Paris: Geuthner; Études

syriaques, 4), 9–26.

Butts, Aaron Michael (2017), ‘Manuscript Transmission as

Reception History: The Case of Ephrem the Syrian (d.373)’,

Journal of Early Christian Studies, 25.2: 281–306.

Chahine, Charbel C. (2002), ‘Une version syriaque du Sermo cum

iret in exsilium (CPG 4397) attribué à Jean Chrysostome’, in

Miscellanea Bibliothecae Apostolicae Vaticanae IX (Vatican

City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana; Studi e Testi, 409), 85–102.

Childers, Jeff W. (2013), ‘Mapping the Syriac Chrysostom: The

Topography of His Legacy in the Syriac Tradition’, in Cornelia B.

Horn (ed.), The Bible, the Qur’ān, & Their Interpretation: Syriac

Perspectives (Warwick, Rhode Island; Eastern Mediterranean

Texts and Contexts, 1), 135–156.

—— (2017), ‘Constructing the Syriac Chrysostom: The Transformation of a Greek Orator into a Native Syriac Speaker’, in

Herman Teule, Elif Keser-Kayaalp, Kutlu Akalin, Nesim Dorum,

and M. Sait Toprak (eds), Syriac in its Multi-cultural Context:

First International Syriac Studies Symposium, Mardin Artuklu

University, Institute of Living Languages, 20–22 April 2012,

Mardin (Leuven: Peeters; Eastern Christian Studies, 23), 47–57.

—— (1994–1995), ‘Étude des 4 manuscrits 12/17, 12/18, 12/19,

12/20’, Parole de l’Orient, 19: 608–627.

mc NO 13

manuscript cultures

�46

Geerard, Maurice (ed.) (1974–1998), Clavis patrum Graecorum

(CPG), 6 vols (Turnhout: Brepols).

Géhin, Paul (2017), ‘Saint Jean Chrysostome dans les manuscrits

syriaques du Sinaï’, in Francesca P. Barone, Caroline Macé, and

Pablo A. Ubierna (eds), Philologie, herméneutique et histoire des

textes entre Orient et Occident: Mélanges en hommage à Sever J.

Voicu (Turnhout: Brepols; Instrumenta Patristica et Mediaevalia,

73), 867–894.

Gippert, Jost (2016), ‘Mravaltavi – A Special Type of Old

Georgian Multiple-Text Manuscripts’, in Michael Friedrich and

Cosima Schwarke (eds), One-Volume Libraries: Composite and

Multiple-Text Manuscripts (Berlin – Boston: De Gruyter; Studies

in Manuscript Cultures, 9), 47–91.

—— (2017), ‘A Homily Attributed to John Chrysostom (CPG

4640) in a Georgian Palimpsest’, in Francesca P. Barone, Caroline

Macé, and Pablo A. Ubierna (eds), Philologie, herméneutique

et histoire des textes entre Orient et Occident: Mélanges en

hommage à Sever J. Voicu (Turnhout: Brepols; Instrumenta

Patristica et Mediaevalia, 73), 895–927.

KIM | JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN SYRIAC PANEGYRICAL HOMILIARIES

Sauget, Joseph-Marie (1968b), ‘Remarques à propos de la récente

édition d’une homélie syriaque attribuée à S. Jean Chrysostome’,

Orientalia Christiana Periodica, 34: 133–40.

—— (1985), ‘Le manuscrit Sachau 220: Son importance pour

l’histoire des homéliaires syro-occidentaux’, Annali dell’Istituto

Orientale di Napoli, 45: 367–397.

—— (1986), ‘Pour une interprétation de la structure de l’homéliaire

syriaque: ms. British Library add. 12165’, Ecclesia orans, 3:

121–146.

Šaniʒe, Aḳaḳi (1927), ‘Xanmeṭi mravaltavi’, Ṭpilisis universiṭeṭis

moambe, 7: 98–159.

Van Esbroeck, Michel, S. J. (1984), ‘Description du répertoire de

l’homéliaire de Muš (Maténadaran 7729)’, Revue des études

arméniennes, new ser., 18: 237–280.

Vööbus, Arthur (1973a), Handschriftliche Überlieferung der

Memre-Dichtung des Jaʿqōb von Serūg, vol. 1: Sammlungen:

Die Handschriften (Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO; CSCO

344; Subsidia 39).

Joannou, Périclès-Pierre (ed.) (1962), Discipline générale antique

(IVe–IXe s.), vol. 1.2: Les canons des synodes particuliers (Rome :

Tipografia Italo-Orientale ‘S. Nilo’; Pontificia Commissione per

la redazione del codice di diritto canonico orientale: Fonti, 9).

—— (1973b), Handschriftliche Überlieferung der Memre-Dichtung

des Jaʿqōb von Serūg, vol. 2: Sammlungen: Der Bestand

(Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO; CSCO 345; Subsidia 40).

Kim, Sergey (2018), ‘A Note on the Syriac Pseudo-Chrysostomic

Sermon In peccatricem, CPG 5140.10’, Journal of Eastern

Christian Studies, 70: 223–225.

Wright, William (1870), Catalogue of Syriac manuscripts in the

British Museum, acquired since the year 1838, Part I (London:

Gilbert and Rivington).

Malki, Ephrem (1984), Die syrische Handschrift Berlin Sachau

220 (Frankfurt am Main, New York: P. Lang; Heidelberger

orientalistische Studien, 6).

—— (1871), Catalogue of Syriac manuscripts in the British

Museum, acquired since the year 1838, Part II (London: Gilbert

and Rivington).

Martin, Charles (1937), ‘Aux sources de l’hagiographie et de

l’homilétique byzantines’, Byzantion, 12: 347–362.

Nedungatt, George, and Michael Featherstone (1995), The Council

in Trullo revisited (Rome: Pontificio istituto orientale; Kanonika,

6).

Rilliet, Frédéric (1982), ‘Note sur le dossier grec du Mingana

Syriaque 545’, Augustinianum, 22: 579–582.

Sachau, Eduard (1899), Verzeichnis der Syrischen Handschriften,

Erste Abtheilung (Berlin: A. Asher & Co.).

Sauget, Joseph-Marie (1961), ‘Deux homéliaires syriaques de la

Bibliothèque vaticane’, Orientalia Christiana Periodica, 27:

387–424.

—— (1968), ‘L’homéliaire du Vatican Syriaque 253: Essai de

reconstitution’, Le Muséon, 81: 297–349.

manuscript cultures

mc NO 13

�145

PICTURE CREDITS | MANUSCRIPT CULTURES

Picture Credits

Homiletic Collections in Greek and Oriental Manuscripts – Histories of

Books and Text Transmission from a Comparative Perspective

Cod.Vind.georg. 4 – An Unusual Type of Mravaltavi

by Jost Gippert and Caroline Macé

Fig. 1: © Iviron Monastery, Mt Athos, Greece.

Fig. 2: © St Catherine's Monastery, Mt Sinai, Egypt.

Figs 3–8: © Korneli Kekelidze National Centre of Manuscripts,

Tbilisi, Georgia.

Figs 9–19: © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria.

Fig. 20: © Iviron Monastery, Mt Athos, Greece.

Fig. 21: © Korneli Kekelidze National Centre of Manuscripts,

Tbilisi, Georgia.

Fig. 22: © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria.

Fig. 23: © Iviron Monastery, Mt Athos, Greece.

Figs 24–25: © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria.

Fig. 1: © Iviron Monastery, Mt Athos, Greece.

Fig. 2: © Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City.

The Earliest Greek Homiliaries

by Sever J. Voicu

Fig. 1: © St Catherine’s Monastery, Mt Sinai, Egypt.

Fig. 2: © Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City.

Gregory of Nyssa’s Hagiographic Homilies: Authorial Tradition and

Hagiographical-Homiletic Collections. A Comparison

by Matthieu Cassin

Fig. 1: © Iviron Monastery, Mt Athos, Greece.

Figs 2–4: © Otto Lendle, published in Gunther Heil, et al. (1990),

Gregorii Nysseni Sermones, vol. 2.

by Jost Gippert

The Armenian Homiliaries. An Attempt at an Historical Overview

by Bernard Outtier

Figs 1–3: © Matenaradan – Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient

Manuscripts, Yerevan, Armenia.

Unedited Sermons Transmitted under the Name of John Chrysostom in

Syriac Panegyrical Homiliaries

Preliminary Remarks on Dionysius Areopagita in the Arabic Homiletic

Tradition

by Sergey Kim

by Michael Muthreich

Fig. 1: © Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City.

Fig. 2: © Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin,

Germany.

Fig. 3: © Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City.

Figs 4–13: © British Library, London, UK.

Fig. 14: © Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage,

Berlin, Germany.

Fig. 15: © British Library, London, UK.

Fig. 16: © Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage,

Berlin, Germany.

Figs 1–3: © St Catherine’s Monastery, Mt Sinai, Egypt.

Figs 4–5: © State and University Library Göttingen, Germany.

Fig. 6: © Bibliothèque Orientale, Beirut, Lebanon.

The Transmission of Cyril of Scythopolis’ Lives in Greek and Oriental

Hagiographical Collections

Compilation and Transmission of the Hagiographical-Homiletic

Collections in the Slavic Tradition of the Middle Ages

by Christian Hannick

Fig. 1. © Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck,

Austria.

Fig. 2: © National Library, Warsaw, Poland.

Fig. 3: © State Historical Museum (GIM), Moskow, Russia.

Fig. 4: © St Catherine's Monastery, Mt Sinai, Egypt.

by André Binggeli

Figs 1–4: © St Catherine’s Monastery, Mt Sinai, Egypt.

Fig. 5: © British Library, London, UK.

A Few Remarks on Hagiographical-Homiletic Collections in Ethiopic

Manuscripts

by Alessandro Bausi

Fig. 1: © Ethio-SPaRe. 'Cultural Heritage of Christian Ethiopia.

Salvation, Preservation, Research', Universität Hamburg.

Fig. 2: Courtesy of Jacques Mercier.

Fig. 3: © Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin,

Germany.

Fig. 4: © Ethio-SPaRe. 'Cultural Heritage of Christian Ethiopia.

Salvation, Preservation, Research', Universität Hamburg.

mc NO 13

manuscript cultures

�Studies in Manuscript Cultures (SMC)

Ed. by Michael Friedrich, Harunaga Isaacson, and Jörg B. Quenzer

From volume 4 onwards all volumes are available as open access books on the De Gruyter website:

https://www.degruyter.com/view/serial/43546

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/

New release

Publisher: de Gruyter, Berlin

18 – Canones: The Art of Harmony. The Canon Tables of the Four

Gospels, edited by Alessandro Bausi, Bruno Reudenbach, and Hanna

Wimmer

The so-called ‘Canon Tables’ of the Christian Gospels are an absolutely remarkable feature of the early, late antique, and medieval Christian manuscript

cultures of East and West, the invention of which is commonly attributed to

Eusebius and dated to first decades of the fourth century AD. Intended to host

a technical device for structuring, organizing, and navigating the Four Gospels united in a single codex – and, in doing so, building upon and bringing

to completion previous endeavours – the Canon Tables were apparently from

the beginning a highly complex combination of text, numbers and images, that

became an integral and fixed part of all the manuscripts containing the Four

Gospels as Sacred Scripture of the Christians and can be seen as exemplary for

the formation, development and spreading of a specific Christian manuscript

culture across East and West AD 300 and 800.

This book offers an updated overview on the topic of ‘Canon Tables’ in

a comparative perspective and with a precise look at their context of origin,

their visual appearance, their meaning, function and their usage in different

times, domains, and cultures.

New release

20 – Fakes and Forgeries of Written Artefacts from Ancient

Mesopotamia to Modern China, edited by Cécile Michel and Michael

Friedrich

Fakes and forgeries are objects of fascination. This volume contains a series

of thirteen articles devoted to fakes and forgeries of written artefacts from the

beginnings of writing in Mesopotamia to modern China. The studies emphasise the subtle distinctions conveyed by an established vocabulary relating to

the reproduction of ancient artefacts and production of artefacts claiming to

be ancient: from copies, replicas and imitations to fakes and forgeries. Fakes

are often a response to a demand from the public or scholarly milieu, or even

both. The motives behind their production may be economic, political, religious or personal – aspiring to fame or simply playing a joke. Fakes may be

revealed by combining the study of their contents, codicological, epigraphic

and palaeographic analyses, and scientific investigations. However, certain famous unsolved cases still continue to defy technology today, no matter how

advanced it is. Nowadays, one can find fakes in museums and private collections alike; they abound on the antique market, mixed with real artefacts that

have often been looted. The scientific community’s attitude to such objects

calls for ethical reflection.

�mc NO 13

2019

ISSN 1867–9617

© SFB 950

“Manuskriptkulturen in Asien, Afrika und Europa”

Universität Hamburg

Warburgstraße 26

D-20354 Hamburg

www.manuscript-cultures.uni-hamburg.de

�

Sergey Kim

Sergey Kim