Photography in

the Third Reich

Art, Physiognomy and Propaganda

EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER WEBSTER

�PHOTOGRAPHY IN

THE THIRD REICH

��Photography in

the Third Reich

Art, Physiognomy

and Propaganda

Edited by Christopher Webster

�https://www.openbookpublishers.com

© 2021 Christopher Webster. Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the

chapter’s author.

OPEN

ACCESS

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC

BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt

the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the

authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Attribution should include the following information:

Christopher Webster, Photography in the Third Reich: Art, Physiognomy and Propaganda.

Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2021. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0202

In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://

doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0202#copyright

Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/

licenses/by/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have

been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://doi.

org/10.11647/OBP.0202#resources

Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or

error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-914-0

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-915-7

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-916-4

ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-917-1

ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-78374-918-8

ISBN Digital (XML): 978-1-78374-919-5

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0202

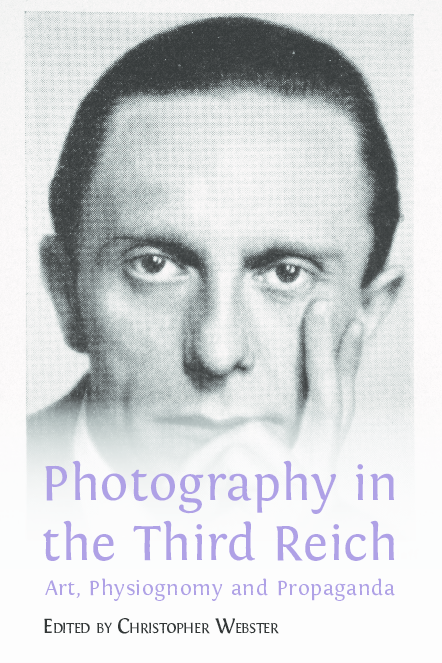

Cover image: Erich Retzlaff, Joseph Goebbels, 1933, reproduced in Wilhelm Freiherr von

Müffling, ed., Wegbereiter und Vorkämpfer für das neue Deutschland (Pioneers and Champions

of the New Germany) (Munich: J. F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1933), p. 11.

Cover design by Anna Gatti.

�Contents

Foreword

vii

Eric Kurlander

Introduction

Editor’s Introduction

1

1

Christopher Webster

Photo Lessons: Teaching Physiognomy during the Weimar

Republic

15

Pepper Stetler

STATE

1. Dark Sky, White Costumes: The Janus State of Modern

Photography in Germany 1933–1945

29

31

Rolf Sachsse

LEADERS

59

2. ‘The Deepest Well of German Life’: Hierarchy, Physiognomy 61

and the Imperative of Leadership in Erich Retzlaff’s Portraits

of the National Socialist Elite

Christopher Webster

WORKERS

3. The Timeless Imprint of Erna Lendvai-Dircksen’s Face of the

German Race

95

97

Andrés Mario Zervigón

HEIMAT

4. Photography, Heimat, Ideology

Ulrich Hägele

129

131

�vi

Photography in the Third Reich

MYTH

5. ‘Transmissions from an Extrasensory World’: Ethnos and

Mysticism in the Photographic Nexus

171

173

Christopher Webster

SCIENCE

6. Science and Ideology: Photographic ‘Economies of

Demonstration’ in Racial Science

203

205

Amos Morris-Reich

Conclusion

239

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Index

257

275

283

�Foreword

Eric Kurlander

Most scholars will recall Walter Benjamin’s observation that fascism is

defined by the ‘aestheticization of politics’. What fewer remember is that

Benjamin first floated this argument in a Weimar-era book review. The

review dealt with a collection of essays titled War and Warrior, which

were edited by the well-known nationalist writer, Ernst Jünger. ‘The

inner connection which lies at the basis of the essays collected in this

volume’, Jünger explained, ‘is that of German nationalism’, a nationalism

‘that has lost its connection to both the idealism of our grandfathers

and the rationalism of our fathers’ and sought ‘that substance, that

layer of an absolute reality of which ideas as well as rational deductions

are mere expressions’. ‘This stance is thus also a symbolic one’, Jünger

continued, ‘insofar as it comprehends every act, every thought and

every feeling as the symbol of a unified and unchangeable being which

cannot escape its own inherent laws’. No wonder that Benjamin titled his

review of Jünger’s collection, ‘Theories of German Fascism’.1 For Jünger

had articulated well, already three years before Hitler’s rise to power,

the relationship between art, myth, and politics in radical nationalist

thinking. It was a relationship that sought to escape the realm of

empiricism by symbolically uniting the racial and the metaphysical in

order to reveal that ‘layer of absolute reality’ that ‘rational deductions’

could never suffice to express.

The essays in this volume work to uncover this ‘layer of absolute

reality’ in the realm of National Socialist photography, namely

‘the stylised representation of the body as constituent parts of the

1

See Ansgar Hillach, Jerold Wikoff and Ulf Zimmerman, ‘The Aesthetic of Politics:

Walter Benjamin’s Theories of German Fascism’, New German Critique 17 (1979),

99–119.

© Eric Kurlander, CC BY 4.0

https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0202.08

�viii

Photography in the Third Reich

Volksgemeinschaft’. More specifically, these essays trace the Third Reich’s

creation of a ‘visual myth of the “master race”’ through the use of

physiognomy — the science of judging character through facial features

and other ‘racial’ characteristics. Although its theoretical premises were

not explicitly supernatural, physiognomy belongs epistemologically

to other ‘border’ or ‘fringe’ sciences (Grenzwissenschaften) popular in

interwar Germany and Austria. These faith-based, supernaturallyinspired sciences included astrology, radiesthesia (‘pendulum

dowsing’), characterology, graphology, cosmobiology, and biodynamic

agriculture — together constituting an important element of what I call

the ‘Nazi supernatural imaginary’.2 Combined with racialist (völkisch)

esotericism, neo-paganism, and Germanic folklore, the border sciences

helped the Third Reich square the circle between claims that National

Socialism was a scientifically sound doctrine based on ‘applied biology’,

in the words of Hitler’s Deputy Rudolf Hess, and the blood-and-soil

mysticism that undergirded National Socialist perceptions of race

and space, culture and aesthetics. National Socialist attitudes toward

photography, informed as they were by so-called pseudo-scientific

doctrines such as physiognomy, might therefore be placed in the context

of a broader supernatural imaginary that informed many aspects of

German culture in the interwar period.

The authors in this volume recognize that the National Socialist

preoccupation with a faith-based, quasi-religious conception of blood

and soil was not the only element determining the aesthetic character

and cultural trajectory of photography in the Third Reich. As Alan

Steinweis, Michael Kater, Pamela Potter, and others have shown in respect

to music, theatre, and the visual arts, one cannot ignore the continuities

between Weimar and National Socialist-era aesthetic traditions.3 Most of

the contributors to this volume recognize such continuities in the realm

of photography as well — between the ostensibly völkisch, romantic,

racially organicist photography of the Third Reich and the highly

modern, experimental culture of the Weimar Republic.

2

3

See Eric Kurlander, Hitler’s Monsters. A Supernatural History of the Third Reich (New

Haven: Yale University Press, 2017).

See Alan Steinweis, Art, Ideology, and Economics in Nazi Germany. The Reich Chambers

of Music, Theatre, and the Visual Arts (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina

Press, 1996); Michael Kater, Culture in Nazi Germany (New Haven: Yale University

Press, 2019); Pamela Potter, Art of Suppression: Confronting the Nazi Past in Histories of

the Visual and Performing Arts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016).

�Foreword

ix

At the same time, one must acknowledge the mystical and irrational

trends in Weimar culture itself before 1933. ‘Occult beliefs and practices

permeated the aesthetic culture of modernism,’ writes Corinna Treitel,

one of the foremost experts on German esotericism. Numerous Weimar

artists and intellectuals, Treitel reminds us, ‘drew on occult ideas and

experiences to fuel their creative processes.’ Among these Weimar-era

artists there was a shared expectation that the ‘new art speak to the soul’

by drawing ‘heavily on fin-de-siècle German Theosophy and its deeply

psychological understanding of a spiritual reality that lay beyond the

reach of the five senses’.4

While such aesthetic trends were not inherently fascist, they

nonetheless influenced and encouraged modes of artistic experimentation

that had little to do with Weimar-era progressivism, what the film

historian Lotte Eisner referred to as the ‘Mysticism and magic, the dark

forces to which Germans have always been more than willing to commit

themselves’, culminating ‘in the apocalyptic doctrine of Expressionism

[…] a weird pleasure […] in evoking horror […] a predilection for the

imagery of darkness’.5 Similarly, the Weimar social theorist Siegfried

Kracauer has cited Fritz Lang’s expressionist masterpiece, The Cabinet of

Dr Caligari, as well as his later films featuring the criminal mastermind

Dr Mabuse, as representative of Germany’s ‘collective soul’ wavering

between ‘tyranny and chaos’.6 In his Theses Against Occultism, Kracauer’s

Frankfurt School colleague, Theodor Adorno, insisted that the interwar

renaissance in occultism — which he dismissively regarded as ‘the

metaphysics of dunces’ — contributed to the rise of National Socialism

through its ‘irrational rationalization of what advanced industrial

society cannot itself rationalize’ and ‘the ideological mystification of

actual social conditions’.7

4

5

6

7

Corinna Treitel, A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern

(Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), pp. 109–10.

Lotte Eisner, The Haunted Screen (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), pp.

8–9, 95–97.

Thomas Koebner, ‘Murnau — On Film History as Intellectual History,’ in Dietrich

Scheunemann, ed., Expressionist Film: New Perspectives (Rochester: Camden House,

2003), pp. 111–23. There are those who see the völkisch, supernatural, and irrational

elements intrinsic to Weimar film as less all-encompassing. See, for example, Ofer

Ashkenazi, A Walk into the Night: Reason and Subjectivity in the Films of the Weimar

Republic (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2010); Ofer Ashkenazi, Weimar Film and Modern Jewish

Identity (New York and London: Palgrave, 2012).

See Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler a Psychological History of the German

Film (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019); Cary J. Nederman and James

�x

Photography in the Third Reich

If esotericism might have abetted some of the more anti-democratic

tendencies within Weimar culture, however, we should be careful about

equating fascist aesthetics with traditionalism or anti-modernism.

National Socialist ideology and the fascist aesthetic that developed

alongside it, was a dynamic and contradictory amalgam of high

modernism and neo-classicism, of industrial rationality and agrarian

romanticism, biological materialism, and racial mysticism. To be sure,

Goebbels and his acolytes were always willing to make concessions

to the market and the needs of propaganda. If the reality of National

Socialist artistic policy was complex and contentious, the attempt to

create a new fascist aesthetic was nonetheless authentic. As Wolfram

Pyta argues in a recent book, Hitler. The Artist as Politician and Military

Commander, the National Socialist Führer viewed himself as an artist

staging an elaborate Wagnerian drama in which he and other party

leaders were Norse heroes fighting a (meta)physical battle against the

Jewish-Bolshevik Nibelungen. In this political and cultural struggle, the

aesthetics of race and the body, as exemplified by physiognomy, was an

essential element.8

Such aesthetic norms went well beyond preoccupations with

representing socioeconomic reality, as articulated in the Weimar-era

photography of Helmar Lerski or August Sander. Already before 1933

völkisch-oriented photographers such as Erna Lendvai-Dircksen and

Erich Retzlaff favoured a more romantic idealism, anticipating the Third

Reich by producing images that reified physiognomic characteristics and

highlighted the putative racial superiority of heroic peasants vis-à-vis

the subhuman other.9 Though still reflecting the aesthetic sophistication

of Weimar modernity and the pragmatism of the ‘New Objectivity’

(Neue Sachlichkeit), these photographers were, like their colleagues in the

8

9

Wray, ‘Popular Occultism and Critical Social Theory: Exploring Some Themes in

Adorno’s Critique of Astrology and the Occult’, Sociology of Religion 42:4 (1981),

325–32. Also see, Adorno, Stars Come Down to Earth and Other Essays on the Irrational

in Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994).

See Wolfram Pyta, Hitler. The Artist as Politician and Military Commander (New Haven:

Yale University Press, 2015); Frederick Spotts, Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics (New

York: Overlook, 2004).

See, for example, Claudia Gabriel Philipp, Deutsche Volkstrachten, Kunst und

Kulturgeschichte: der Fotograf Hans Retzlaff (Marburg: Jonas Verlag, 1987); Thomas

Friedrich and Falk Blask, eds, Menschenbild und Volksgesicht: Positionen zur Porträt

fotografie im Nationalsozialismus (Münster: LIT, 2006).

�Foreword

xi

fields of characterology or graphology, mimicking and in some respects

employing highly modern techniques. Far from rendering the world ‘wie

es eigentlich war’ ‘(what it was actually like)’, they were in fact working

to create a new (faith-based) reality through photography, drawing

on the supernatural imaginary wherever possible. Thus, while ThirdReich-era photography appropriated elements of high modernism and

scientific progress in technical terms, racial physiognomy reinforced a

vision of racial utopia, a völkisch ideal disconnected from any real-world

understanding of science or society.

The perennial debate regarding the visual arts in the Third Reich,

after all, is twofold. The first question has to do with the accuracy of

Benjamin’s assessment above: were the National Socialists successful in

aestheticizing politics in service of their racial and spatial goals; or did

they resign themselves to eliminating only the most prominent examples

of avant-garde (‘degenerate’) art, allowing, sometimes even exploiting,

modern art — not to mention apolitical entertainment — in order to

maintain popularity? The second and related question has to do with

artistic coercion versus consent. To what degree did the regime manage

culture through top-down repression? Or was culture determined by

bottom-up efforts of artists and writers to ‘work toward the Führer’, in

the words of Ian Kershaw, voluntarily producing art that appeared to

satisfy the National Socialist-era market, Hitler, or both?

Early ‘intentionalist’ accounts of National Socialist culture tended

to focus on Hitler and Goebbels’ preoccupation with coordinating

and politicizing art (aestheticizing politics) from the top down. Many

of the same scholars suggested that the National Socialists were

cultural philistines, traditionalists who couldn’t recognize quality art

or understand modernist aesthetics.10 Beginning in the 1980s and 90s,

more ‘functionalist’ accounts have emphasized the porous nature

and artistic eclecticism that defined National Socialist cultural policy,

characterized by competing agendas and often producing improvised

10

See, for example, Paul Ortwin Rave’s Kunstdiktatur im Dritten Reich (Hamburg:

Mann, 1949); Hellmut Lehmann-Haupt, Art under a Dictatorship (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1954); Franz Roh, ‘Entartete’ Kunst: Kunstbarbarei im Dritten Reich

(Hannover: Fackelträger, 1962); David Stewart Hull, Film in the Third Reich (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1969); David Welch, Propaganda and the German

Cinema 1933–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983); Henry Grosshans,

Hitler and the Artists (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1983).

�xii

Photography in the Third Reich

and inconsistent outcomes. Instead of a National Socialist ideological

consensus imposed from above, we see a remarkable willingness on

the part of leading artists and intellectuals to ‘coordinate’ themselves,

whether for economic or ideological reasons, in order to remain viable.11

The essays in this volume provide a newer perspective that moves

beyond both of these schools.12 First and foremost, this collection

indicates that the National Socialists were anything but cultural hacks.

They could appreciate modernist aesthetics, and innovative artists

could appreciate National Socialism as well. In this sense, the National

Socialists were open to new, even avant-garde ideas — provided they

served the purposes of the regime (or pleased its leaders). Indeed, in

looking at the role of the state, individual party leaders, and National

Socialist propaganda before and after the outbreak of the Second World

War; in surveying photographic representations of peasants and workers;

and in analyzing aesthetic norms such as Heimat and beauty, the essays

in this volume uncover a greater ideological coherence and cultural

symbiosis between the regime and the arts than one is accustomed to

finding in classic functionalist accounts. Yet this ideological consensus is

both more voluntarist and diverse than most traditional (‘intentionalist’)

interpretations of National Socialist culture would allow. Whether due

to market forces or ideology, many photographers were eager to work

towards the Führer in order to remain financially and culturally viable

in the Third Reich.

The National Socialists, in turn, embraced many photographers’

experiments in modern technology and communication. This modernity

in technique appeared, in particular, in the pages of the era’s popular

photographic periodicals, such as the Deutsche Illustrierte and Volk und

Rasse, which ranged in content from beautiful ‘Nordic’ women on skis

to physiognomic profiles of putatively ‘degenerate’ Dachau inmates.13

Hitler’s personal photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann, and the abovementioned Erich Retzlaff produced parallel images of the National

11

12

13

See again Steinweis, Art (1996); Kater, Culture in Nazi Germany (2019); Potter, Art

of Suppression (2016); Spotts, Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics (2004). For an earlier

example anticipating this argument, see Hildegard Brenner, Die Kunstpolitik des

Nationalsozialismus (Berlin: Rowohlt, 1963).

For a useful synthesis of this newer approach, see Kater, Culture in Nazi Germany

(2019).

David Crew, ‘Photography and the Cinema,’ in Robert Gellately, ed., Oxford

Illustrated History of Germany (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

�Foreword

xiii

Socialist elite, promoting an ideal of physiognomic ‘nobility’. Similar

attempts were made by Retzlaff and others to portray the German peasant

as an ideal of Aryan physiognomy, the archetypal representative of bloodand-soil ideology. National-Socialist-era photographers also glorified

labour, though in ways that emphasized technology as well as race,

creating images not dissimilar from those idealizing industrialization

in America or the Soviet Union. Photos of the German Heimat were,

in contrast, especially romanticized and racialized, drawing on the

mythical imagination of Germany’s past and future. Nowhere were the

aesthetics of physiognomy more clearly on display — or more explicitly

politicized — than in Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia, which played on

racialist tropes as consciously and as successfully as any contemporary

work of National Socialist propaganda.

What held all this together — the regime’s intentions and the artists’

aspirations — was the ‘Nazi supernatural imaginary’, infused by völkisch

imagery and the aesthetics of physiognomy. This pseudo-scientific

thinking allowed faith-based, blood-and-soil mysticism and ‘applied

biology’ to co-exist, bringing the Third Reich’s racial and spatial fantasies

into more concrete reality. Though technically sophisticated and

modernist in aesthetic sensibility, National-Socialist-era photography

consequently drew on the ‘parascience’ of physiognomy to facilitate

a project of racial resettlement and even mass murder. At least in the

realm of photography, as the essays in this volume suggest, Benjamin’s

pronouncement still rings true.

��Introduction

Editor’s Introduction

Christopher Webster

When photography was born from the union of chemistry and optics

(‘officially’ in 1839),1 it was long anticipated and much desired. From the

Renaissance onwards, the urge to provide greater and greater accuracy

drove artists to use optical aids when drawing, such as the Camera

Obscura. Among the newly wealthy and emergent middle classes of

this anthropocentric era, born out of the Enlightenment, there was also

a desire for an image-making process that did not rely on the expensive

and elitist process of painting. Devices such as the Camera Obscura led

to other machines that could provide simple but accurate likenesses.

The advent of photography in 1839 presented to the world a device

that seemed capable of reproducing reality so exactly as to seem a very

piece of that reality itself. Even a scene physically far removed from the

intended viewer’s gaze could apparently be brought from the realm of

the exotic to the innocuous space of the drawing room of any European

or American household. Through optics and chemistry, a translocation

occurred where it seemed that the receiver of the photograph could

hold and read a fragment of another place. Although it did not provide

an actual window onto reality (after all, the photograph in its flattened,

monotone, shrunken state is a derivation of what the cameraman saw)

it was so unique in its time that it appeared to do so.

As the next best thing to the ‘real’, the photograph quickly assumed

a position as arbiter of truth without precedent. This was particularly

1

Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre’s photographic process was disclosed to the French

public on 19 August 1839.

© Christopher Webster, CC BY 4.0

https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0202.09

�2

Photography in the Third Reich

relevant in an age when empiricism was the cardinal rule. Photographs

appeared as certainties. They seemed certain because they were verifiably

of something — even the photocollage or the carefully assembled

photomontage were composed from pieces that had at first been a

representation of an object before the lens. Photography lent gravitas

to the past and framed collective histories: from the family snapshot to

the state occasion; from the dance floor to the battlefield; from birth to

death. The photograph was regarded not only as a scientific marvel but

also as an objective aid to recording, which would affect a revolution in

human perception. The photograph became evidence and purported to

display things as they were. Within months of photography’s invention

and announcement the new photographers began to travel to every

corner of the European-dominated world.

The ability of the camera to take (as opposed to make) a seemingly

‘true’ portrait likeness, a vera icon, ensured its popularity. When

portraits were made, physiognomic science was quickly applied to

read the shadow on the photographer’s plate. Until relatively recently,

physiognomy was generally assumed to be able to reveal, by careful

study of the features and body of the subject, something about the

inner person. The Swiss pastor Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741–1801)

famously helped to revive physiognomy as a credible study after

it had fallen somewhat into disrepute during the Middle Ages and

Renaissance, when it became associated with palmistry and other

divinatory practices. The Renaissance polymath Giovanni Battista

della Porta (1538–1615) for example, had been brought before the

Inquisition after over-enthusiastic Neapolitans had hailed him as

a ‘magus’. Della Porta had, amongst his other publications, also

published De Humana Physiognomonia in 1586. In De Humana, Della

Porta’s makes a comparative study between the external characteristics

of humans and animals. As with many of the nascent scientists of the

Renaissance, Della Porta’s worldview was intrinsically spiritual and

magical, a kind of spiritual metaphysics.

Lavater described how, after careful training, the physiognomist

could make a reading of the character in the face; in so doing he was

drawing on a broad tradition that included Della Porta. Lavater ensured

the continuing popularity of such an understanding through likeness.

Nor should the extent of his influence be underestimated. After Lavater’s

�Introduction

3

death in 1801 the Scots Magazine remarked that he had been, ‘For many

years one of the most famous men in Europe’.2

For Lavater, the likeness was a derivation of the mark of the creator,

a mystical connection to a higher ideal that through moral degradation

led to visual ‘types.’ Lavater posed the rhetorical question:

The human countenance, that mirror of Divinity, that noblest of

the works of the Creator — shall not motive and action, shall not the

correspondence between the interiour and the exteriour, the visible and

the invisible, the cause and the effect, be there apparent?3

The empiricist nineteenth-century sciences, which sought reason

over superstition and evidence over faith, nevertheless explored

processes of visual examination that were linked to, and born out of

an understanding of what was effectively an esoteric physiognomy and

widely divergent interpretations of Darwinian evolution. Thus, when

photography was invented at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it

was quickly assimilated as a tool for making physiological assessments,

both in the service of science and as a more populist cultural record.

Certainly, by the end of the nineteenth century, the camera was being

applied prolifically throughout emergent scientific fields of study, such

as anthropology, as a measuring and classifying device.

In the late nineteenth century, many in Germany, a country that had

only recently been forged into a national state, were keen to demarcate

and underline what could specifically be regarded as ‘Germanic’, both

visually and otherwise. One symptom of the cultural anxieties of the

era was the emergence of the völkisch movement, an eclectic mix of

philosophies and trends that involved notions of ethnicity, Heimat (or

homeland), a return to the land, nature, and romanticism, in particular.

Science and photography became inextricably intertwined with these

notions especially as several leading scientists, including Ernst Haeckel

(1834–1919), endorsed a social-Darwinist and ethnically-led hypothesis

of German racial science. German science, therefore, laid down the

visual formatting for the photographer’s approach to the visage of the

German Volk.

2

3

John Graham, ‘Lavater’s Physiognomy in England’, Journal of the History of Ideas 22:4

(1961), 561.

Johann Kaspar Lavater, Essays on Physiognomy for the Promotion of the Knowledge and

Love of Mankind (London: G. G. J. and J. Robinson, 1789), p. 24.

�4

Photography in the Third Reich

By the early twentieth century, ethnographic images were

commonly utilised as an increasingly sophisticated tool to validate

claims centred on the distinction between one race and another.

Scientific texts such as Deutsche Köpfe nordischer Rasse (German heads

Nordic race, 1927)4 written by the racial scientists Hans F. K. Günther

(1891–1968) and Eugen Fischer (1874–1967) set out to illustrate the

Nordic ‘type’ using the clear eye of the photographer’s lens. The use of

photography as a comparative means of assessment and identification

became increasingly paramount during this period, not only in

scientific documents, but also in popular publications that contained

photographs of racial types from around the world displayed in

photographic charts. What these studies highlighted was not only

the geography and range of race, but also what was perceived as the

negative admixture and miscegenation that, according to celebrated

scientists like Günther), posed a threat to the German race.

In line with the development and use of documentary and creative

modernist photography in other parts of the world, Weimar Germany

(1919–1933) also quickly established the photographic form as a

revelatory medium to document the German people. Moreover,

whether the political ideology was of the left or of the right, many

photographers were galvanised to impose a typological approach even

in their creative practices. Progressive photographic practice in Weimar

Germany emerged emphatically and innovatively with its rejection of

‘arty’ Pictorialist practices of manipulation to offer something straight,

direct, sometimes brutal — what came to be characterised as the ‘New

Vision’. This was when photography, ‘came to occupy a privileged place

among the aesthetic activities of the historical moment’.5

The photographic focus on physiognomy in Germany that

preoccupied so many of the photographers between the two world

wars was a focus common to those with conservative or nationalist

sympathies, as well as to those who rejected or were unaffiliated

with the extremes of the political axis. The celebrated and influential

photographer August Sander (1876–1964), for example, employed

4

5

Eugen Fischer and Hans F. K. Günther, Deutsche Köpfe nordischer Rasse: Ergebnisse

des Preisausschreibens für den besten nordischen Rassenkopf (München: J. F. Lehmann

Verlag, 1927).

George Baker, ‘Photography between Narrativity and Stasis: August Sander,

Degeneration and the Death of the Portrait’, October 76 (Spring 1996), 76.

�Introduction

5

physiognomy as the central pillar of his portrait catalogue of the

German people. According to George Baker, Sander had followed

a personal visual interpretation of Hegelian dialectics and sought

to demonstrate how degeneracy is co-equal with progress.6 In

1931 Kenneth Macpherson, writing about Helmar Lerski’s (1871–

1956) book Köpfe des Alltags (Everyday Heads), thought that the

photographer had defined a ‘clear definition of the physionomicalpsychological accord; a blending of visible and ‘invisible’, so that

rather more than character delineation is there […] Pores of the skin,

cracked lips, hairs in the nostrils — these are part of the purpose and

reality’.7 But photographers who would later prosper under National

Socialism also adopted these approaches using a ‘clear definition of the

physionomical-psychological’ as defined by those Weimar proponents

of the ‘New Vision’.

When the National Socialists emerged as the dominant political force

in Germany in 1933, many photographers who coordinated themselves

according to the new dispensation (the Selbstgleichschaltung or selfcoordination) were already considered as pioneers in their photographic

output with regard to depictions of the racial German proletariat.

Indeed, their work seemed an ideal vehicle to broadly disseminate

notions centred on the Volksgemeinschaft or people’s community. The

work was invested with a romantic artfulness that made the images

visually appealing, as well as carrying the legitimisation of document.

This was a time when:

[…] ordinary people increasingly recognised themselves as inhabitants

of cultural territories distinguished by language and custom […] As

Germans came to regard each other as contemporaries, they took

increasing interest in the tribulations of fellow citizens, tied their own

biographies to the national epic, and thereby intertwined personal with

national history.8

These photographs were born from a then emergent modernist

photographic practice, which often possessed the descriptive vigour of

the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) and the directness of an Edward

6

7

8

See George Baker, ‘Photography between Narrativity and Stasis’ (1996).

Kenneth Macpherson, ‘As Is’ (1931), in David Mellor, ed., Germany — the New

Photography 1927–1933 (London: The Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978), p. 68.

Peter Fritzsche, ‘The Archive’, History and Memory 17:1/2 (Spring/Summer 2005), 17.

�6

Photography in the Third Reich

Weston. These portraits are presented without filters and where there is

a hint of a romantic vision it is far removed from the soft vagueness of

Pictorialism. They have more in common with Walker Evans’ portraits of

sharecroppers in Alabama or Dorothea Lange’s Depression-era migrant

workers. These American counterparts were producing photographic

studies as a marker of their time, when their subjects were enduring

the trauma of the Depression and its deleterious effect on labour and

farming. Supported by government salaries, these photographers

sought to ‘show and tell’, to underscore the primacy of the American

relationship to ‘honest labour’ whilst simultaneously highlighting the

plight of these people in turbulent and even disastrous economic times.

Their German contemporaries echo this concerned documentary

approach. However, images of plight were not recorded, but rather

a celebration of the peasant and proletarian. These photographs

are situated as a counterpoint to the perceived dangerous effects of

Weimar cosmopolitanism and urban living. They emphasize notions

of Heimat and Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil), concepts that were

embedded in National Socialist thinking. They were constructed

images of ‘Ethnos’.9

The subjects recorded in their portfolios are often constructed as

striking and unavoidable. Very often, the subjects are encountered

face-to-face, almost literally. In the folio publications that included

much of this work, many of the portraits are reproduced at near-lifesize, creating an unsettling sense of intimacy — sharp eyes, creases of

skin, wrinkles, stubble, and roughness. There can be no doubt that this

work was often an attempt to ennoble the subjects.10 Clearly these are

not ‘neutral’ photographs; their use by, for example, the Rassenpolitische

Amt der NSDAP (the Office of Racial Policy) in various publications and

expositions situates them as political objects and thus inextricably bound

to the fundamental belief system of the National Socialist state.

In the first serious post-war examination in English of the art of

National Socialism, Brandon Taylor and Wilfried van der Will’s The

9

10

The editor has used ‘Ethnos’ as a summary term for this ethnically driven approach

to (in particular) the autochthonous peasant and other ‘people of the soil’. These

were images about the ‘tribe’, about blood and belonging, framed, as this text

explores, through a modern lens of myth, politics, and science.

Although this was not exclusively the case — see for example Andrés Zervigón’s

discussion on Erna Lendvai-Dircksen in this volume.

�Introduction

7

Nazification of Art (1990) suggested that the historical unwillingness to

discuss the subject of National Socialist creative making in any critical

depth had been the result of an:

[…] understandable reluctance […] to enter into discussions about

National Socialist art for fear of being accused of implying support either

for the works under review or for the regime which sponsored them. On

the other hand, the tendency to condemn all such works as ‘horrific’ to

an equal degree is a sure sign that the process of historical, social and

aesthetic analysis has yet to begin.11

Although there has been a plethora of studies on a wide variety of aspects

of image-making in the Third Reich, including film, the graphic and fine

arts, in the (nearly) thirty years since The Nazification of Art appeared,

a focussed examination in English of the work of specifically creative

photographers of Ethnos who flourished under National Socialism is

now long overdue, particularly in relation to understanding the lasting

historical legacy of their work as ‘art’ employed as propaganda.12 Yet,

such examinations are still fraught by the potential for negative reactions

to the topic, especially in modern-day Germany and Austria. As a result,

the photography under scrutiny here has received scant non-judgmental

11

12

Brandon Taylor and Wilfried van der Will, The Nazification of Art: Art, Design, Music,

Architecture and Film in the Third Reich (Winchester: The Winchester Press, 1990),

p. 5. Even this valuable academic text did not explore creative photography in any

depth.

Exceptions do exist in German. Rolf Sachsse’s book Die Erziehung Zum Wegsehen:

Photographie im NS-Staat (Dresden: Philo and Philo Fine Arts, 2003) is a wellresearched, broad, yet detailed study of this period but only available in German;

another good example (also only available in German) is the series of essays

on the work of Erna Lendvai-Dircksen: Falk Blask and Thomas Friedrich, eds,

Menschenbild und Volksgesicht: Positionen zur Porträtfotografie im Nationalsozialismus

(Münster: Lit, 2005). Paul Garson’s New Images of Nazi Germany (Jefferson:

McFarland and Co. Inc., 2012) is an interesting study but, like his earlier volume

Album of the Damned (Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, 2009), has an

emphasis on personal photography and snapshot photography. Other studies

are broader in their scope (i.e., their historical focus is broader) such as Klaus

Honnef, German Photography 1870–1970 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997)

or focus on very specific topics, such as Janina Struk’s excellent Photographing the

Holocaust (London: I.B. Tauris, 2003), or deal with the periods prior to Hitler (in

particular the Weimar period) or post-Hitler. Relevant recent studies of interest

in English include Elizabeth Cronin’s Heimat Photography in Austria: A Politicized

Vision of Peasants and Skiers (Salzburg: Fotohof Edition, 2015). However, literature

on specifically creative/art photography during the Third Reich, and in particular

by those supportive of the regime, remains remarkably scarce.

�8

Photography in the Third Reich

critical attention in the various histories of photography, largely because

of the political affiliation of this work prior to 1945 and the ongoing

political bias of some contemporary academics. As the historian Anna

Bramwell has suggested, ‘Reading history backwards has its problems,

especially when it is done from the highly politicised (and nearly always

social democratic) viewpoint natural to historians of Nazi Germany’.13

This volume is intended to be a part of a process of re-evaluation in

context.

Though it has been well documented how many creative

photographers made the decision to leave Germany prior to or

soon after the January 1933 electoral success of Adolf Hitler and his

Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP),14 there were some

who not only tolerated, but welcomed the political change and, through

self-co-ordination with the regime, continued to practice as creative

freelance photographers during the twelve years of the Third Reich.

This book therefore is a photo-historical survey of the work of some

of those select photographers who embraced (or at least professionally

endured) National Socialism and the formulation of a somatic vision

that accorded or aligned itself with a National Socialist worldview.

Involved as it is in the main with creative practice, this text places

a deliberate emphasis on those photographers who made an idealised

(and aesthetically guided) representation of the overarching notion

of Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil), often through the image of the

German peasant (and his landscape) and almost invariably through an

interpretation of physiognomy. The idea of ‘Blood and Soil’ predated

National Socialism, however, the idea was adapted and upheld as a

core tenet of the movement and has since become synonymous with

National Socialism.

Again, according to Anna Bramwell, ‘Blood and Soil’ as understood

by National Socialism,

… was the link between those who held and farmed the land and whose

generations of blood, sweat and tears had made the land part of their

being, and their being integral to the soil. It meant to them the unwritten

13

14

Anna Bramwell, Blood and Soil: Richard Walther Darré and Hitler’s ‘Green Party’

(Abbotsbrook, Bourne End, Bucks.: The Kensall Press, 1985), p. 2.

Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) won the national

elections on 30 January 1933, signalling the beginning of the so-called ‘Third Reich’.

�Introduction

9

history of Europe, a history unconnected with trade, the banditry of the

aristocracy, and the infinite duplicity of church and monarchy. It was the

antithesis of the mercantile spirit, and still appeals to some basic instinct

as a critique of unrootedness.15

This book examines the influence of pseudo-scientific notions (such as

physiognomy) as well as völkisch culture on photography and how this

ethnically orientated photography was exploited by the regime (but also

enthusiastically produced) after 1933. It analyses the social, political,

institutional and cultural processes that affected the photographic

practices of select photographers and the proliferation of their influential

work during the twelve years of National Socialist rule in Germany. This

book sets out to explore how an aestheticized photography was used to

create a visual correlation to the ‘Master Race’ (and its antitheses) and

continued to do so under the auspices of the National Socialist state. The

contributions to this volume explore the question of whether we can

talk of a distinct National Socialist photographic style and posits that if it

does exist it might be argued to lie in a stylised representation of the body

as constituent parts of the Volksgemeinschaft (the people’s community)

by these often passionate photographers, who were concerned with

imposing a new National Socialist and völkisch-influenced reading of the

notion of a ‘Blood and Soil’ Ethnos.

Where National Socialist ideology itself was conflicted and

conflicting (shifting emphasis over its twenty-five-year period from the

original twenty-five-point programme of 1920), after 1933 all aspects

of culture, including photography and the visual arts, were deeply

impacted by the specific demands of the new government. By the mid1930s, the regime’s policy towards the visual arts had effectively become

a reflection of Hitler’s personal taste for a form of ‘Heroic Realism’ with

‘Blood and Soil’ as a core element of these representations.

In the Weimar era, photographers such as Helmar Lerski and August

Sander had developed their physiognomic precepts for photography

on notions such as class and social position; photographers under

National Socialism on the other hand, based their studies on biology,

culture, and the homeland or Heimat (and to some degree a mythic

melange of all of these), the guiding principles of ‘Blood and Soil’.

15

Bramwell, Blood and Soil (1985), p. 53.

�10

Photography in the Third Reich

Many of these photographers, for example, Erna Lendvai-Dircksen

(1883–1962) and Erich Retzlaff (1899–1993), had already begun

developing a catalogue of racially ‘satisfactory’ and ‘heroic’ peasants

during the Weimar period. Whereas their approach became officially

sanctioned by the regime after the Gleichshaltung (co-ordination) of

culture that began in 1933, photographers like Sander were censured.

This book includes examinations of how already established, as well

as emergent photographers reflected these ‘Blood and Soil’ tendencies

in their portfolios and publications, and how personal ideology, social

advancement, scientific discourses, and political pressure influenced

their practice and output.

***

In the first chapter ‘State’, Rolf Sachsse explores the interplay between

National Socialist policies towards the arts and photographic aesthetics

where ‘media modernity was introduced into a totalitarian government

structure’, as well as how this interaction created a lasting legacy in

(West) Germany after 1945. Sachsse unravels the seemingly contrary

positions of National Socialism’s celebration of the past and its emphasis

on a modern industrial vision, weaving a discourse that examines how

‘New Vision’ approaches to media, design, and photography played on

paradoxically archaic depictions of Germans themselves, their history,

and their landscape. It was, as Sachsse asserts, a process of encouraging

a ‘looking away’ that used state-of-the-art approaches.

Chapter two, ‘Leaders’, describes how leadership was framed as

an aesthetic manifestation of the Führerprinzip (leader principle), the

model for leadership in the National Socialist state. The chapter focuses

on select publications by one specific photographer, Erich Retzlaff, to

explore how this photo-construction extended, like the Führerprinzip

itself, through the so-called National Socialist ‘elite’, for example, in

publications such as Wegbereiter und Vorkämpfer für das neue Deutschland

(Pioneers and Champions of the New Germany, 1933). It is argued that

many of the photographs, such as those reproduced in Wegbereiter and

other publications like it, go beyond mere record and physiognomically

position these men as a new type of man, a political elite. This

presentation of an ethno-nationalist elite included sportsmen, artists,

and, later, military figures, amongst others. Using these and other

�Introduction

11

photographic examples, the chapter explores how the physiognomic

profile of Hitler can be read in conjunction with an attempt to develop

a broader physiognomic portrait of a National Socialist leadership elite.

Following on from the themes developed in the second chapter,

in chapter three, ‘Workers’, Andrés Zervigón examines the framing

of the ‘Germanic’ peasant and worker, and Erna Lendvai-Dircksen’s

‘psychological’ approach in particular. Zervigón explores how these

close-up photographs often forced the viewer to look longer at the

face of the subject, to engage with it, and thus to read it as framed by

a mode that employed both archaism and ultra-modernity. Zervigón

argues that the reading of the photograph was thus determined by the

context within which the image was framed and the milieu in which it

was being presented. From the modernity of the Reichsautobahn, to the

lone farmer at work with the scythe and the peasant girl in traditional

costume, this photography seemed to set out to create an aestheticised

and propagandistic record of paradoxical modernisation and entrenched

tradition. At the centre of these visual constructions were the workers

themselves as time-worn or idealised bodies, racial paragons, and

dramatic physiognomic types.

Ulrich Hägele (chapter four) follows the development of the

visualisation of the notion of Heimat from its Romantic origins in the

nineteenth century through to its manifestation as a genre of creative

photography during the era of the Third Reich. Hägele surveys the

often convoluted and ideologically entangled use of Heimat that found

its political apotheosis after 1933 with an emphasis on the work of Erna

Lendvai-Dircksen and Hans Retzlaff. Using these specific examples,

Hägele explores the photographic manifestation of Heimat as projected

onto the individual situated within the land and as part of the land itself

in a ‘Blood and Soil’ context. The chapter sets out how the relationship

of these photographic portfolios to National Socialism was more

complex than has formerly been proposed, with an examination of their

placement as ‘documentary’. The essay appraises these photographer’s

works as more than merely a blunt affirmation of National Socialist

ideology, arguing rather that they were informed by a broader sense of

national romanticism.

Chapter five, ‘Myth’, explores this notion of a ‘national romanticism’

further by examining the controversial impact of nineteenth-century

�12

Photography in the Third Reich

völkisch and occult currents on National Socialism, and how this

supposedly parlous influence leached into image-making and into

photography in particular. Using select examples, the chapter explores

the photographic framing of the German as ‘other’. National Socialist

ideologues and propagandists, like their predecessors in the nineteenthand early-twentieth-century völkisch mise-en-scène, clearly recognised

the unifying power of myth and thus promoted (and exploited) it as

part of their overarching cultural programme. The work of controversial

scholars such as Herman Wirth, and the influence of political

institutions such as Himmler’s Ahnenerbe, played a role in directing

this visual manifestation of the (specifically) rural inhabitant so that

they were presented as a race apart, having a semi-divine origin in a

mythical Urheimat in the ‘ultimate north’. As images of Ethnos, these

photographic portfolios ‘revealed’ the peasant as an archetypal figure.

In contrast to chapter five, Amos Morris Reich’s essay ‘Science’

(chapter six) enters into the respective scientific logics of a variety of

scientific and scholarly fields and reconstructs, from within, the use of

photographic techniques with regards to ‘race’ before and during the

National Socialist period. From a methodological perspective, the text

surveys Rudolf Martin’s standardization of photography as a measuring

device in physical anthropology. The second part explores how, during

the Third Reich, these techniques were redefined because their scientific,

political, and aesthetic contexts had been transformed. Morris Reich

argues here that the range of scientific and ideological positions with

which photography was aligned became smaller, and rather than being

guided by any substantial scientific questions, these positions were

used to uphold components of the National Socialist worldview and,

sometimes, immediate political concerns. But this process of contraction

was not limited to the science-politics nexus, in the strictest sense of

the term, as it reflected wider contemporary cultural-political processes.

The chapter ends by exploring how, during the Third Reich, the

scientific uses of photography increasingly overlapped with National

Socialist aesthetic ideologies in general and with certain branches of

documentary and art photography in particular.

***

�Introduction

13

Photography in the Third Reich is an exegesis of the work of select

photographers and aesthetic photographic practices during the Third

Reich. It is not intended as an overview of photographic practice and

application per se during the Hitler years, rather, it is specifically focussed

on those photographers who engaged with work that emphasised an

anti-rational, anti-enlightenment, and romantic model, creating a

visual framework upon which ideas relating to the Volk could be hung,

especially in the image of the autochthonous peasant.

This aesthetic photography presented the subjects as inhabitants of

an idealised space and underlined a radical traditionalism relating to

Ethnos. The subjects represented a connectivity with the past through

customs, dress, and, in particular, the face, as representative of breeding

and ‘good blood’. The ideal that was visualised looked backwards

through a blend of myth, tradition, race science, and occult currents to

a divine origin of the ‘Aryan’ who had, it was suggested, emerged in a

distant time from an Ultima Thule. And, Janus-like, this work was part of

an ideology that also looked forward to a rebirth, an epic palingenesis16

where, out of the dying decadent world, a new one would be forged in

fire and blood.

This book also explores how this interpretation of the autochthonous

Volk was directed by and co-opted for political propagandistic purposes

and where it might be said to fit into an aesthetic and contextual

understanding of photography from this period. Although not

specifically an eisegesis of the relationship of this photography to ethnic

cleansing as a result of racial political policies, it will be argued that the

work of these photographers created a mindset of national uniqueness,

a visual ethnic identity, and ultimately a reactionary intolerance in the

metapolitical crucible of the Third Reich.

Read on a formalist level (a medium-specific approach to interpreting

photography using notions such as style, self-expression, aesthetics

and photographic tradition) this creative photography of the Third

Reich carries all the merits of what is considered ‘great’ modernist

photography from that period. In terms of a purely aesthetic reading

(composition, tone, technique, expressiveness, originality, etc.) they are

often outstanding and certainly equivalent to the work of their peers

16

On this notion of a national ‘palingenesis’ see Roger Griffin, Modernism and Fascism

(2007).

�14

Photography in the Third Reich

outside of Germany who are still highly regarded by critics, collectors,

museums, and galleries. But such a reading only reveals one facet of

their construction. Reading these images from a post-modern and nonaesthetic context (as objects spawned with a particular social function

and ideological coding) is also insufficient, however, even when it

allows a sharper analytical review of their origination. This book adopts

both approaches (formalist aesthetic and analytical). This co-dependent

reading facilitates an analysis of these images’ aesthetic presence as

material objects when reproduced in magazines and other media, such

as ‘coffee-table’ picture books, allied with the historical, socio-cultural,

and political origins that made these photographs so powerful as carriers

of meaning, which potently added to the German national myth.

�Photo Lessons: Teaching Physiognomy during

the Weimar Republic

Pepper Stetler

Photography flourished during the Weimar Republic as a prolific form

of visual communication. Artists were remarkably aware of their era as a

moment of transition in which an imagined future of a new photographic

language was yet to occur.17 In a photographically illustrated essay

published in 1928, the graphic designer Johannes Molzahn envisioned

a future in which reading would be an obsolete skill. ‘“Stop reading!

Look!” will be the motto in education,’ Molzahn wrote, ‘“Stop Reading!

Look!” will be the guiding principle of daily newspapers’.18 In an

essay published in 1927 on the growing prevalence of photography in

advertising, the Hungarian-born Bauhaus professor László MoholyNagy predicted, ‘those ignorant of photography, rather than writing,

will be the illiterate of the future’.19 Molzahn, Moholy-Nagy and others

anticipated photography’s eventual achievement of a universally

accessible and highly efficient form of communication. Germany’s

immediate future did not fulfil such emancipatory predictions. By the

end of the Weimar Republic, it was clear that one of photography’s most

significant achievements was repackaging physiognomy, the ancient

practice of identifying and classifying people according to racial and

ethnic type, as a modern visual language.20

17

18

19

20

See Pepper Stetler, Stop Reading! Look!: Modern Vision and the Weimar Photographic

Book (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015).

Johannes Molzahn, ‘Nicht mehr lessen! Sehen!’ Das Kunstblatt 12:3 (1928), p. 80.

László Moholy-Nagy, ‘Die Photographie in der Reklame,’ Photographische

Korrespondenz 63:9 (1927), 259.

The bibliography on physiognomic theories during the Weimar Republic is

extensive. In addition to Rittelmann’s work (see for example her essay ‘Facing

Off: Photography, Physiognomy, and National Identity in the Modern German

Photobook’ Radical History Review 106 (December 2010)), studies particularly

relevant here are Rüdiger Campe and Manfred Schneider, eds, Geschichten der

Physiognomik: Text, Bild, Wissen (Freiburg im Breisgau: Rombach Verlag, 1996);

Sander Gilman and Claudia Schmölders, eds, Gesichter der Weimarer Republik: eine

physiognomische Kulturgeschichte (Köln: DuMont, 2000); Sabine Hake, ‘Faces of

Weimar Germany,’ in Dudley Andrew, ed., The Image in Dispute: Art and Cinema

in the Age of Reproduction (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1997), pp. 117–47;

Claudia Schmölders, Das Vorurteil im Leibe: eine Einführung in die Physiognomik

(Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1995); Wolfgang Brückle, ‘Politisierung des Angesichts:

© Pepper Stetler, CC BY 4.0

https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0202.10

�16

Photography in the Third Reich

Repeated and paraphrased by critics, typographers, art historians,

and photographers, Moholy-Nagy’s statement became a catchphrase of

the era and justified the publication of countless photographic books.

Walter Benjamin saw a connection between Moholy-Nagy’s prediction

and August Sander’s Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time), which he

described as a training manual for the increasingly vital skill of reading

facial types. Antlitz der Zeit featured sixty of Sander’s portraits of German

citizens taken between 1910 and 1929. The project has come to exemplify

the systematic and comparative nature of physiognomic looking that

photography facilitates. ‘Whether one is of the Left or the Right,’

Benjamin writes, ‘one will have to get used to being looked at in terms

of one’s provenance’.21 The statement is part of an essay on the history of

photography. Yet a preoccupation with the future — what the outcome

of this culture dominated by photographic media will be — haunts

this essay by one of the era’s most important critics of photography.

The urgency of Benjamin’s statement lies in its anticipation of a visual

practice that would dominate the Third Reich — recognizing specific

racial, ethnic, and political identities through different visual features.

But it is also remarkable for its connection between the photographic

innovations that Benjamin had watched emerge during the Weimar

Republic and this foreboding future. The connection seemed inevitable

to him by 1931, so much so that this form of looking was not something

to resist, but something to get used to.

Declarations of photography as a new universal language and its

revival of physiognomic looking went hand in hand with the racialized

and metaphysical pursuits of National Socialist photography. This

continuity points to uncomfortable connections between Weimar

modernism and the fascist ideology of totalitarian regimes. As Eric

Kurlander points out in his forward to this volume, scholars acknowledge

21

Zur Semantik des fotografischen Porträts in der Weimarer Republik,’ Fotogeschichte

17:65 (1997), 3–24; Richard T. Gray, About Face: German Physiognomic Thought from

Lavater to Auschwitz (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004); Helmut Lethen,

‘Neusachliche Physiognomik: gegen den Schrecken der ungewissen Zeichen,’ Der

Deutschunterricht 2 (1997), 6–19.

Walter Benjamin, ‘A Short History of Photography,’ in Michael W. Jennings, Brigid

Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin, eds, The World of Art in the Age of its Technological

Reproducibility and other Writings on Media (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press, 2008), p. 287. Originally published in Die literarische Welt (September-October

1931).

�Fig. 0.1 ‘Physiognomik,’ Praktische Berlinerin 16 (1927), 15. Public domain.

�18

Photography in the Third Reich

that National-Socialist-era culture developed from — rather than

broke with — Weimar aesthetic traditions. The racial strategies of

photographers during the Third Reich took advantage of efforts to

instil a photographic literacy in a mass public during the Weimar

Republic. In the first chapter of this volume, Rolf Sachsse argues for the

‘media modernity’ of the Third Reich — how some of the totalitarian

regime’s most celebrated photographers developed from the strategies

of ‘New Vision’ photography during the 1920s and early 1930s. This

introduction establishes efforts to train modern viewers in photographic

literacy during the Weimar Republic as an important parallel trend. The

photographers discussed in the chapters that follow build on such skills

already put in place by the photo-media culture of the Weimar Republic.

Illustrated magazines and newspaper editors were aware that the

growing dominance of the visual required their readers to possess new

sets of perceptual skills. An article from 1927, published in the women’s

magazine Praktische Berlinerin (see Fig. 0.1), presents physiognomy as a

way to enhance the enjoyment of summer vacations:

For the married woman who is wrapped up in her occupation as

housewife and mother, vacation is the only opportunity to meet new

people… Luckily, the nature of man was created so that his character can

for the most part be determined from facial features. Writing, hands, gait,

posture, shape of the head, and face create a unity that good judges of

character quickly utilize for their purposes.22

Although its origins lie in the ancient world, the article describes

physiognomy as a modern visual skill that can be developed through

experience.

Physiognomic skills also prevent potentially duplicitous social

interactions: ‘Lifelong friendships are often started on the beach, and

of course disappointment often follows soon after a hasty, pleasant

attraction, when one’s affections have been given away too quickly.

Knowledge of humankind is necessary for all women’.23 The photographs

accompanying the essay break up the human face into the most

concentrated areas of physiognomic meaning: eyes, forehead, lips, chin,

and nose. The layout of the article emphasizes the separation of the face

into parts, yet it also allows the viewer to imagine their reorganization

22

23

‘Physiognomik,’ Praktische Berlinerin 16 (1927), 15.

Ibid.

�Introduction

19

into a unified whole. Columns of text separate eyes from lips, foreheads

from chins, while the photographs of noses appear in the middle of the

page. The article’s photographs provide views of the face through which

the overall character and identity of a person can be deduced. Two

photographs of each part of the face appear, allowing us to compare, for

example, a ‘softly outlined, good-natured nose’ to a ‘sharply outlined,

egotistical nose.’ The physiognomic lesson of this essay depends on the

cropping, close-ups, and montage-like arrangement of photographic

images. Physiognomic reading is considered a skill necessary to interact

with strangers in modern life. It requires modern viewers to organize

information and establish a coherent worldview from an overwhelming

visual field. As presented in this article, physiognomy involved

determining the whole from the part, deducing characteristics of a

person from a particularly telling detail. The determination of character

from facial features cropped and isolated in photographs exemplifies

the kind of visual training that Molzahn and Moholy-Nagy promoted.

While illustrated newspapers like Praktische Berlinerin trained a

mass audience in physiognomic looking, photographic archives of

racial types were emerging as important tools in areas of specialized

study. Dr Egon von Eickstadt’s Archiv für Rassenbilder (Archive of Racial

Images) assembled ‘scientifically and technically flawless images from

life’ into an archive of ‘all races and racial groups of the Earth’.24 Offered

for sale to the public as a book in 1926, the archive consisted of small

cards that could be used ‘for instruction and lectures’ and fulfilled

‘the needs of anthropologists and representatives of neighbouring

fields (anatomy, ethnology, geography, and others)’.25 In order to

convey scientific standardization and objectivity, each card showed a

profile, frontal, and oblique photography of a member of a particular

race. Eickstadt’s archive emphasizes the comprehensive nature of the

physiognomic project that is so easily facilitated by the reproducibility

of the photographic medium. Multiple photographs are compiled into

one composite picture of a race or ethnicity.

24

25

Egon von Eickstedt, ed., Archiv für Rassenbilder: Bildaufsätze zur Rassenkunde (Munich:

J.F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1926). An advertisement for the archive in the back of Ludwig

Ferdinand Clauss, Von Seele und Antlitz der Rassen und Völker: Eine Einführung in

die vergleichende Ausdrucksforschung (Munich: J.F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1929) states,

‘Das Archiv will in absehbarer Zeit von allen Rassen und Rassengruppen der Erde

wissenschaftlich und technisch einwandfreie Bilder vom Lebenden bieten.’

From advertisement in the back of Clauss, Von Seele und Antlitz der Rassen und Völker

(1929).

�20

Photography in the Third Reich

Fig. 0.2 Bildaufsatz 2, Archivkarte 14 (Image attachment 2, archive card 14) in

Egon von Eickstedt, ed., Archiv für Rassenbilder: Bildaufsätze zur Rassenkunde

(Archive of Pictures of Race: Image Cards for Racial Studies) (Munich: J.F.

Lehmanns Verlag, 1926). Public domain.

Such an approach anticipates photographic books like Erna LendvaiDircksen’s, Das deutsche Volksgesicht (The Face of the German Race),

discussed by Andrés Zervigón in the third chapter of this collection.

Erich Retlzaff’s Das Gesicht des Geistes (The Face of the Spirit) compiles

photographs of elite German individuals into a comprehensive portrait

of German national and cultural achievement, as demonstrated by

Christopher Webster in chapter two.

Chiromancy, the physiognomic study of the hands, was an occult

yet prevalent part of Weimar culture’s obsession with the signifying

potential of the body. Photographic books of hands helped to revive

this mythical form of knowledge. Das Buch der hunderte Hände (The

Book of a Hundred Hands) is compiled by an enigmatic ‘Mme. Sylvia,’

who appears in the frontispiece of the book with her face covered by

a black mask.26

26

Mme. Sylvia, Das Buch der hunderte Hände: mit einer Geschichte der Chirosophie

(Dresden: Verlag von Wolfgang Jess, 1931).

�Introduction

21

Fig. 0.3 Frontispiece, Mme. Sylvia, Das Buch der hunderte Hände: mit einer Geschichte

der Chirosophie (The Book of a Hundred Hands) (Dresden: Verlag von

Wolfgang Jess, 1931). Public domain.

The photograph sets up a tension between visibility and invisibility

and announces the mysterious nature of the knowledge contained on

the following pages. Like many physiognomic projects subsequently

produced during the Third Reich, Das Buch der hunderte Hände and

its author, Mme. Sylvia, mixes the rational and the occult. Das Buch

der hunderte Hände focuses on the hands of identifiable figures such as

Thomas Edison and Albert Einstein (see Fig. 0.4).

In addition to photographs of distinguished hands, the book contains

several images of handprints, which conflates the photographic index

and the direct trace of human hands in ink on paper. While publication

does not establish a German national identity, like books of photographic

portraits published by National Socialists, it establishes physiognomic

looking as a form of mystically defined knowledge, a way of connecting

what is seen in a photograph with spiritually sanctioned truth.

Hände: eine Sammlung von Handabbildungen grosser Toter und Lebender

(Hands: A Collection of Images of Hands of Great Dead and Living

People) mixes photographs of the hands of key historical figures

�22

Photography in the Third Reich

Fig. 0.4 The hands of the inventor Thomas Alva Edison and the theoretical

physicist Albert Einstein reproduced in Mme. Sylvia, Das Buch der hunderte

Hände: mit einer Geschichte der Chirosophie (The Book of a Hundred Hands)

(Dresden: Verlag von Wolfgang Jess, 1931). Public domain.

with the anonymous hands of professions and ethnicities. The book’s

preface states that the photographs in the book are meant to connect the

appearance of man to an overall ‘world view’:

Observations and the conclusions drawn from them are based on the

general recognition that the form and whole external appearance of man

offers a symbolism that concerns itself intensively with the dependence

of the worldview on the pure observation of objects. […] The more the

pure function of this perception is intensified, this symbolism is given

specific contents and a connection between man and world, between past

and future can be created.27

Along with the preface, the book includes brief commentaries on the

photographs collected. The first thirty-five plates in Hände) feature the

hands of legendary names in European history, including Napoleon,

27

Hände: Eine Sammlung von Handabbildungen grosser Toter und Lebender (Hamburg:

Gebrüder Enoch Verlag, 1929), p. 5.

�Fig. 0.5 The hand of the artist Max Liebermann reproduced in Hände: eine Sammlung

von Handabbildungen grosser Toter und Lebender (Hands: A Collection of

Images of Hands of Great Dead and Living People) (Hamburg: Gebrüder

Enoch Verlag, 1929). Public domain.

�24

Photography in the Third Reich

Goethe, Victor Hugo, and Gottfried Keller.28 The book then shows the

hands of contemporary notables that exemplify a certain type. The text

points to the distinctive features of the hands, the lengths of certain

fingers, the width of wrists, the lines on the palm, which indicate certain

traits of the individual. For example, the ‘slender hand and long, strong,

jointed fingers with youthful and long nails’ of Max Liebermann in plate

49 is associated with the ‘strong, subjective naturalism’ of his painting29

(see Fig. 0.5).

Intermixed with such famous hands are also anonymous examples

of the hands of members of a professional occupation. Plate 46, for

example, shows the ‘short, stable, widely separated fingers with

wide ends’ of an engineer, whose ‘strongly developed lines of the

hand are repetitively crossed and sometimes broken’.30 Plate 48

displays the ‘strong and long hand with a regular and oval form’ of

a photographer.31 Hands often appear with props appropriate to the

profession being represented. The hands of a mountaineer in plate

59 are holding a pick and lantern. The hands of a potter in plate

60 appear in the act of working on a potter’s wheel. Other hands

represent ethnicities, such as the ‘Brazilian’ hands in plate 75 and the

‘Somali’ hands in plate 76. Others are meant to express emotions. The

limp hand in plate 82 is labelled as a ‘tired hand.’ The interlocking

hands with bent wrists in plate 85 demonstrate ‘tense hands.’ Despite

these brief commentaries that guide the viewer to notice certain

characteristic features in each hand, and to compare the long fingers

of the painter to the short, blunt fingers of the engineer, a brief note

at the beginning of these introductory commentaries states that these

remarks ‘in no way attempt to create meaning or an analysis’ but

instead mean to ‘encourage precise observation’.32 The accompanying

text) guides the viewer to notice certain aspects of the photographed

hands. While physiognomic meaning purports to be purely visual, text

is nonetheless required to teach viewers how to look.

28

29

30

31

32

Hände does not explain how photographs of the hands of such historical figures

were obtained.

Hände: Eine Sammlung von Handabbildungen grosser Toter und Lebender (1929), p. 15.

Ibid., p. 14.

Plates 46, 48, 57 (Office Worker), 60 (Potter), 64 (Worker), and 66 (Draftswoman)

are credited to Albert Renger-Patzsch. The hand of the photographer in plate 48, is

possibly a self-portrait, although it is not identified as such.

Hände: Eine Sammlung von Handabbildungen grosser Toter und Lebender (1929), p. 3.

�Introduction

25

Hands act simultaneously as a bodily fragment and their own

autonomous system of expression. Beyond the traits and emotions

of an individual, Weimar-era physiognomic studies searched for

evidence of unifying connections among social, ethnic, and racial

groups. Bodily movements and gestures could potentially express the

unifying features of a culture or race. In his book Das Gesichtausdruck

des Menschen (The Facial Expression of Man) , the physician Hermann

Krukenberg wrote that ‘above all else it is an issue of whether a

legitimate inner connection exists overall or whether facial expression

is determined only by habits and upbringing. In the latter case, the

entire study of facial expression can demand only a relatively small

amount of interest’.33 Krukenberg indicates a desire to locate a unifying

and eternal trait of humankind, something eternally present rather

than shaped by circumstantial context. He also attempts to move the

study of communication away from linguistic theory and semiotics.34

Human identity, and the expression of that identity, he argued, was

not entirely discursive or arbitrarily motivated. Instead, unifying,

eternal features of humanity remain constant, but manifest themselves

in various forms. ‘The human Gesichtausdruck is a combination of

facial expression and enduring features. The latter primarily forms

the characteristic traces of humankind and the peculiarities of race

specifically.’35 Because the face displays the ‘enduring features,’

its expressions make up a universal form of communication that is

unspeakable and purely visual: ‘One language is still understood by