Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies Vol. 33 No. 1 (2009) 17–41

Un-Orthodox imagery: voids and visual narrative in the

Madrid Skylitzes manuscript*

Elena Boeck

DePaul University

In the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript (BN, Vitr. 26–2) representations of Orthodox triumph

over iconoclast heresy range from startlingly novel to seemingly incoherent. While previous studies have posited that the visual programme of the chronicle originates in

Comnenian Constantinople, this article argues that the visual narrative is out of place in a

climate of rigorous Comnenian Orthodoxy. The visual narrative actively restructures and

revisions Byzantine history: iconoclast arch-villains such as John the Grammarian are

assigned symbols of sanctity, Orthodox heroes such as patriarch Methodios and empress

Theodora are obscured and misrepresented, and important events in the chronicle are

turned into visual voids.

Under the gaze of the empress and her courtiers, the Byzantine patriarch Methodios

confronts a female accuser and exposes his groin area to prove irrefutably that he did not

have sex with that woman. On another folio, a golden halo of sanctity graces the head of

the anathematized heretic John the Grammarian. These are but two of several tantalizing

images that illuminate the triumph of Orthodoxy in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript (BN,

Vitr. 26–2), the only surviving mediaeval illustrated chronicle in Greek. In this manuscript,

representations of Orthodox triumph over iconoclast heresy range from startlingly novel

to seemingly incoherent. Could a Byzantine patron have approved of image after image

in which the arch-villains of Byzantine history, Iconoclast emperors and patriarchs,

are assigned symbols of sanctity, while Orthodox heroes are obscured and misrepresented?

Previous studies have posited that the Madrid Skylitzes is a copy of an original

produced either for Alexios I Komnenos or during his era, but they have never analyzed its

* I would like to thank my dissertation advisor, Maria Georgopoulou, for her constant encouragement and

patient advice. I am very grateful to Leslie Brubaker, Nancy Patterson Ševch enko, Alice-Mary Talbot and Brian

Boeck for consultations and comments on earlier versions of this article, and the two anonymous readers of the

BMGS for their thoughtful suggestions. I would like to acknowledge the generous support of Yale University

for research funding, Dumbarton Oaks for a Junior fellowship that facilitated writing, and DePaul University

for funding photograph rights and reproduction.

© 2009 Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham

DOI: 10.1179/174962509X384598

�18

Elena Boeck

un-orthodox imagery in the context of a vigorous and rigorous Comnenian Orthodoxy.1

The style of one artistic hand has been singled out as the determining factor for hypothesizing a Comnenian original.2 Rather than give style priority as the bearer of meaning,

this study demonstrates that a visually un-orthodox, and religiously un-Orthodox, visual

narrative makes a hypothetical Byzantine original produced for Alexios Komnenos a most

unlikely scenario.

The contested identity of the Madrid manuscript

Since in its current condition the Madrid Skylitzes contains no explicit references to its

original patron, date of production or provenance, scholars disagree on the central points

of the manuscript’s identity. The text itself is a Byzantine chronicle composed some time

before the end of the eleventh century by a high official at the court of Constantinople,

known in historiography as Skylitzes.3 The chronicle, which covers Byzantine history from

811 to 1057, enjoyed great popularity as more than twenty manuscripts of the text

survive.4 Scholars agree to attribute the manuscript’s paleography to southern Italy, but

still debate issues of dating and the number of scribes involved.5 The manuscript displays

a rare heterogeneity of artistic styles, usually referred to as ‘Byzantine’ and ‘Western’.

There is no consensus on the number of artists that were involved.6

1 André Grabar dated this manuscript to no earlier than the middle of the thirteenth century, but he believed

that its Constantinopolitan model was executed c.1100 (see A. Grabar and M. Manoussacas, L’Illustration du

manuscrit de Skylitzès de la Bibliothèque Nationale de Madrid (Venice 1979) 131, 172, 173). Nigel Wilson

hypothesized that the Madrid manuscript is a third-generation copy of the Constantinopolitan prototype

(N. Wilson, ‘The Madrid Scylitzes’, Scrittura e Civiltà 2 (1978) 216, 218).

2 Wilson, ‘The Madrid Skylitzes’, 218; Grabar and Manoussacas , L’Illustration, 173.

3 The manuscript is written in Greek (see A. Laiou, ‘Prologue’, in Joannis Scylitzae Synopsis Historiarum:

Codex Matritensis Graecus Vitr. 26–2 (Athens 2000) 13). This publication is also a colour edition of the entire

manuscript. The English translation by John Wortley will be used in this article: John Scylitzes, A Synopsis of

Histories (811–1057 A.D): A Provisional Translation, trans. J. Wortley (Winnipeg 2000). For the most recent

publication on the Madrid Skylitzes, see V. Tsamakda, The Illustrated Chronicle of Ioannes Skylitzes in Madrid

(Leiden 2002). The recent dissertation by Bente Bjornholt, ‘The use and portrayal of spectacle in the “Madrid

Skylitzes” (Bibl. Nac. Vitr. 26–2)’ (unpublished doctoral thesis., Queen’s University of Belfast 2002), was not

available to me for consultation.

4 An extensive introduction to the text and the critical edition was produced by I. Thurn, Ioannis Scylitzae

Synopsis historiarum (Berlin 1973) vii–xlvi.

5 B. L. Fonkich, ‘Paleograficheskaia zametka o Madridskoi rukopisi Skilitsy’, VV 42 (1981) 231–2; Wilson,

‘The Madrid Skylitzes’, 212; Tsamakda, The Illustrated Chronicle, 11–4.

6 Since decades of stylistic analysis produced contradictory results and divergent dating, this study will

not reconsider the question of style. Most recently, Tsamakda identified seven artists (see Tsamakda, The

Illustrated Chronicle, 373–9). For detailed discussions, see S. Cirac Estopañan, Skyllitzes Matritensis.

Reproducciones y miniaturas (Madrid/Barcelona 1965) 37–40; A. Grabar, ‘Les illustrations de la chronique de

Jean Skylitzès à la Bibliothèque Nationale de Madrid’, Cahiers Archéologiques 21 (1971) 191–211.

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 19

The origins of the visual programme represent the biggest bone of contention: the

manuscript has alternately been upheld as a window into Byzantine reality, sidestepped as

an ambiguous entity that defies easy categorization, or identified as an ad hoc Sicilian

production. Most scholars who have written about this manuscript view it as a copy of a

lost Constantinopolitan original and employ it to hypothesize the existence of a genre of

Byzantine illuminated histories.7 I have elsewhere provided support for Ihor Ševcenko’s

h

conclusion that the visual programme is an ad hoc creation and readers who might wish to

pursue the manuscript’s connections to Norman Sicily can do so there.8 Here I shall only

advance arguments pertaining to the visual narrative’s putative Comnenian origins.

Reconciling the manuscript with its hypothetical Constantinopolitan original has

long prevailed over analyzing the vision of Byzantine history that the visual narrative

projects. The recent comprehensive study of the manuscript by Vassiliki Tsamakda resurrected the hypothesis that the Madrid manuscript is a copy of a lost Byzantine original,9

and revived Kurt Weitzmann’s terminology: from discussion of ‘migrated miniatures’ to

considerations of an imperial ‘archetype’.10 Tsamakda considered the visual programme to

be a passive reflection of the chronicle: ‘The miniature cycle, seen as a whole, does not

interpret the narration of Skylitzes.’11 In a 2005 publication that entirely ignores the

controversies over the visual programme’s origins, Elisabeth Piltz described the images

as ‘secular documentary pictures’ and characterized the manuscript as a ‘panorama of

Byzantine events ... “videotaped” before our eyes’.12

In contrast, I argue that un-Orthodox imagery reflects active and deliberate choices

made in the ad hoc production of the visual narrative.13 The illustrations transform the

7 Tsamakda also considered this manuscript to be a copy of a lost archetype (Tsamakda, ‘The miniatures of

the Madrid Skylitzes’, in Joannis Scylitzae, 148–9). Other scholars who have described the manuscript as a copy

of a lost Constantinopolitan original include Sebastian Cirac Estopañan, Nikolaos Oikonomides, Christopher

Walter and Boris Fonkich.

8 Based on analysis of the organization and distribution of labour in the manuscript, Ihor Ševch enko suggested

that ‘the Madrid Skylitzes is an original creation; “original” in the sense of having been made ad hoc, illustrations and all’ (I. Ševcenko,

‘The Madrid manuscript of the chronicle of Skylitzes in the light of the new dating’,

h

in Byzanz und der Westen: Studien zur Kunst des Europäischen Mittelalters (Wien 1984) 125, 126, 127). For the

most extensive argument for the ad hoc nature of the visual narrative, see E. Boeck, ‘The art of being Byzantine:

history, structure and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Yale

University 2003); see also G. Parpulov’s review of Tsamakda’s monograph in JÖB 56 (2006) 383–7.

9 Tsamakda, The Illustrated Chronicle, 267–8.

10 Tsamakda, The Illustrated Chronicle, 22, 263, 265.

11 Tsamakda, The Illustrated Chronicle, 265.

12 E. Piltz, Byzantium in the Mirror: the Message of Skylitzes Matritensis and Hagia Sophia in

Constantinople (Oxford 2005) 1.

13 A likely scenario would have involved the designer selecting topics for illustration and marking places for

future images in an unillustrated copy of the Skylitzes text. Simultaneously, a list of instructions for the artists

would have been generated, which ranged from vague or generic in most cases (‘pursuit in battle,’ ‘seated

imperial figure’) to very specific (clearly addressing main participants, aspects of setting, physical attributes

and other details) in cases of topics that were of primary interest to the patron (see Boeck, ‘The art of being

Byzantine’, Chapter 2).

�20

Elena Boeck

text and become a distinct narrative.14 Visual sequences highlight subjects of particular

interest to the patron of the visual programme and subjects that were deliberately marked

for omission become visual voids.15 These conscious omissions are particularly important

for understanding the origins of the visual narrative. Because these choices are embedded

in the structure of the visual narrative, they can be analyzed regardless of whether or not

the Madrid manuscript is a copy.16 By focusing on representations of the protagonists of

the Orthodox struggle in the Madrid Skylitzes, this study reveals a ‘Byzantine’ artistic

hand that not only ignores established Orthodox iconographies, but also diverges

creatively from the text.

John the Grammarian

John the Grammarian provides a crucial case for testing whether the images of the Madrid

Skylitzes conform to Byzantine ideology and iconography. In the Byzantine imagination,

John the Grammarian was one of the most captivating, vivid and dark figures of the

Iconoclast controversy. Yet this renowned, reviled and iconographically distinct character

in Byzantine art does not sustain an Orthodox, or even typologically consistent, iconography in the visual narrative of the Madrid Skylitzes. At the design stage, John’s

un-Orthodox story was not singled out as significant. Orthodox rhetoric established John

as the very incarnation of evil. He has featured prominently in the writings of the clergy,

in saints’ lives, and in chronicles: he was anathematized in the Synodikon of Orthodoxy,17

called ‘John the Transgressor’, 18 ‘knower of Satan19 and enemy of the church’,20 ‘equal of

the “Hellenes”’, ‘Iannis the Magician’, ‘sorcerer patriarch’ and ‘impious’. Lemerle aptly

calls this lore ‘the legendary traditions, which surround John the Lekanomantos with a

sulphurous halo’.21

14 I employ Hayden White’s definition of narrative: ‘[T]he narrative is not merely a neutral discursive form

that may or may not be used to represent real events in their aspect as developmental processes but rather entail

ontological and epistemic choices with distinct ideological and even specifically political implications’ (H.

White, The Content of Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (Baltimore, MD 1987) ix).

15 I use the term ‘visual void’ in a similar manner to Wolfgang Kemp’s ‘blank’, referring to conscious

omissions (see W. Kemp, ‘Death at work: a case study on constitutive blanks in nineteenth-century painting’,

Representations 10 (1985) 110).

16 I have dealt extensively with questions of copying in my dissertation and plan to address the subject in

depth in a future article (see Boeck, ‘The art of being Byzantine’, 57–62, 225–36).

17 F. Uspenskii, Sinodik v nedeliu pravoslaviia: svodnyi tekst s prilozheniiami (Odessa 1893) 13.

18 P. Lemerle, Byzantine Humanism, trans. H. Lindsay and A. Moffatt (Canberra 1986) 163–4. For an

excellent discussion of the epithets applied to John the Grammarian by iconodule writers, see I. Ševch enko,

‘Anti-iconoclastic poem in the Pantocrator psalter’, Cahiers Archéologiques 15 (1965) 47–8.

19 MPG 99, 1772C.

20 MPG 99, 1772 C.

21 Lemerle lists a number of these abusive terms, with discussion. See his Byzantine Humanism, 164, 156, 166.

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 21

Images of a distinctly wicked John the Grammarian feature in some of the Marginal

Psalters, demonstrating that Byzantine artists could unambiguously distinguish Orthodox

heroes from heretics and saints from villains.22 The appearance of John in the marginal

Psalters belongs to a very distinct iconographic type: his wild hair directly associates him

with the devil.23 In the Barberini Psalter, on folio 89v, the haloed patriarch Nikephoros

tramples the prostrated simoniac cleric with wild hair — John the Grammarian (inscribed

‘Jannes’).24 This representation of John accords with the Byzantine iconographic typology

of heretics as noted by Christopher Walter: ‘Heretics ... are represented in Byzantine art

not for themselves but in order to set in perspective the superiority, the triumph, or the

privileges of the orthodox.’25

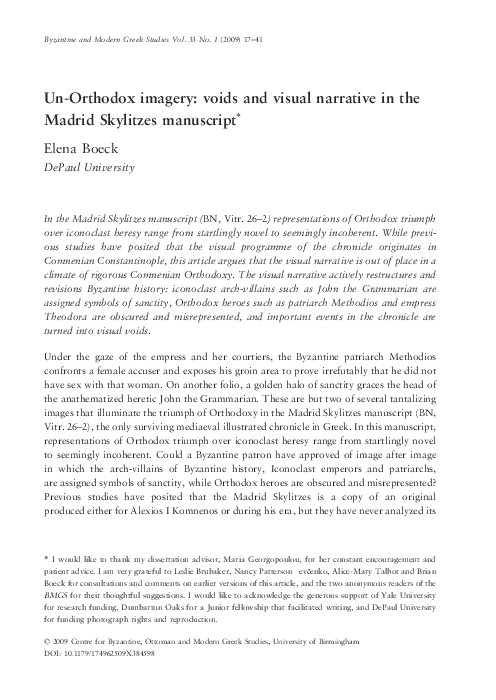

In several Skylitzes images, the heretic John the Grammarian metamorphoses from

‘an inferior person, a victim, a conquered enemy’26 into a centre-stage presence, both

triumphant and Orthodox.27 In two consecutive representations, this vile heretic morphs

into a haloed saint (fol. 47, fol. 47va)! John is represented as a gray-haired, bearded cleric

who delivers a communication from a haloed emperor to a seated, turbaned Muslim on

folio 47, and distributes gifts to additional turbaned figures on folio 47va (Figure 1). It is

not the sulphurous halo of iniquity created by the Orthodox rhetoric, but a golden halo of

sainthood that shines brightly around John’s head in these images. Can we imagine that

the purported Constantinopolitan original would have committed such an ideological

blunder not once, but twice? Not if we take seriously eleventh-century Orthodox claims

22 Scholarship on the Marginal Psalters is extensive. For recent discussions and bibliography, see K. Corrigan,

Visual Polemics in the Ninth-century Marginal Psalters (Cambridge 1992); C. Barber, ed., Theodore Psalter:

Electronic Facsimile (Champaign 2000). For the Barberini Psalter, see J. Anderson, P. Canart and C. Walter,

The Barberini Psalter: Codex Vaticanus, Barberinianus Graecus 372 (Zurich 1989); see also S. Der Nersessian,

L’Illustration des psautiers grecs du Moyen âge: Londres, Add. 19.352 (Paris 1970), esp. 63–70; S. Dufrenne,

L’Illustration des psautiers grecs du Moyen âge: Pantocrator 61, Paris. grec. 20, British Museum 40731 (Paris

1966); A. Cutler, ‘Liturgical strata in the Marginal Psalters’, DOP 34 (1980) 17–30; J. Lowden, ‘Observations on

the illustrated Byzantine Psalters’, Art Bulletin 70 (1988) 242–60; A. Grabar, ‘Quelques notes sur les psautiers

illustrés byzantins du IXe siècle’, Cahiers Archéologiques 15 (1965) 61–82. The relationship among the eleventhcentury psalters is complex and there is debate about the degree of conscious anti-iconoclast polemic they

exhibit (see C. Barber, ‘Readings in the Theodore Psalter’, in Theodore Psalter, 14; see also L. Brubaker, ‘The

Bristol Psalter’, in C. Entwistle (ed.), Through a Glass Brightly: Studies in Byzantine and Mediaeval Art and

Archaeology presented to David Buckton (Oxford 2003) 135).

23 See Ševcenko,

‘Anti-iconoclastic poem’, 41; Corrigan, Visual Polemics, 27–9; Walter, ‘Heretics in

h

Byzantine art’, Eastern Churches Review 3 (1970) 44–5.

24 For a description of this image, see Anderson et al., The Barberini Psalter, 89. Corrigan, discussing

the prototype of the Barberini image in the Khludov Psalter, states: ‘[T]he Khludov image condemns John the

Grammarian as a simoniac as well as an Iconoclast, an accusation that can be found in several sources of the

period’ (Corrigan, Visual Polemics, 28).

25 Walter, ‘Heretics’, 48.

26 Walter’s words reflect the proper role of heretics in Byzantine imagery (Walter, ‘Heretics’, 48).

27 Although Tsamakda notes that John’s halo is ‘extraordinary’, she does not consider the issue any further

(Tsamakda, The Illustrated Chronicle, 90).

�22

Elena Boeck

Figure 1 Madrid Skylitzes, folio 47, © Biblioteca Nacional de España

that heretics had recently revived the notion that ‘only Iconoclasts are orthodox and

faithful’.28 The haphazard use of haloes throughout this section of the manuscript muddles

the memory of Orthodox tribulations since even emperors portrayed as persecuting

Orthodox saints are at times assigned haloes.29

It is remarkable that the visual narrative is oblivious to the characterization of

John in the chronicle passage immediately adjacent to the first sainted image: ‘Loyal to

the Emperor and of the same heresy as the Emperor, [John] was experienced in affairs

of state and highly skilled in debating.’30 This disjunction between text and image is

highly instructive: although the essence of the action presented in the text is clearly

communicated in the image of John setting off on his embassy to the Saracens, the

Orthodox cultural background of the text that insisted on John’s heretical nature is

absent. This image is the first of a sequence of four images of the successful mission of

28 Euthymios Zigabenos, ‘Dogmatic panoply against the Bogomils,’ in Christian Dualist Heresies in the

Byzantine World, c.650–c.1450, trans. J. Hamilton and B. Hamilton (Manchester 1998) 188.

29 The use of haloes is inconsistent in the manuscript, but together with structural analysis it testifies that

Orthodox concerns were of little importance at the design stage, not simply the execution stage. E.g.,

Theophilos is represented haloed on folios 49 va, 49 vb and 50 a, while persecuting Orthodox saints, including

Lazaros.

30 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 34; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 56.90.

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 23

John to Syria.31 The images highlight John’s diplomatic triumph with a Muslim Syrian

ruler, including a delivery of imperial gifts, making an indelible impression upon the

Saracens with munificence and oratorical skills, and securing release of the Byzantine

prisoners.32 The anathematized heretic of Orthodox discourse becomes a saint and a

successful handler of Saracens in the visual narrative of the Madrid Skylitzes.33

If the images were simply designed to provide ‘an objective, visual parallel’ to the

text as Tsamakda assumed, one would expect to find at least one image that reflects the

subsequent long section of chronicle narrative devoted to the iconoclasm of John’s protégé

emperor Theophilos.34 The text narrates how images of beasts were substituted for holy

icons, sacred objects were abused in markets, holy men were driven from cities, and

monks and bishops languished in jails or hid out in caves. Surprisingly, not a single one of

these easily visualized and ideologically charged themes was included in the pictorial

programme. Instead, the visual narrative gave priority to John’s diplomacy and even

depicted the notorious iconoclast Theophilos with a halo (fol. 47).35 Whether this

divergence is by mistake or design, it is un-Orthodox.

Somewhat later in the manuscript, following the triumph of Orthodoxy, John

reappears in a group of images on a single page opening devoted to the last surge of his

unrepentant iconoclasm (fol. 64v–65r). The text recounts how John, who was confined in

a monastery, ordered his deacon to deface icons in a church. As punishment for this deed,

John was lashed. The chronicle then reminds the reader of his dark powers, flashing back

to an incident in which John’s destruction of the three-headed statue in the Hippodrome

caused the sorcerous annihilation of leaders of an invading foreign army.36 The three

images are closely interconnected through the duplication of compositional elements: a

repetitive architectural setting ties fol. 64va and fol. 64vb, while ladders, a gesturing,

bearded cleric (John), and acts of destruction of images link fol. 64va and fol. 65 as

pendant images. The positioning of the latter pair is most peculiar, since John’s attempt

31 For a discussion of John’s mission, see P. Magdalino, ‘The road to Baghdad in the thought-world of ninthcentury Byzantium’, in L. Brubaker (ed.), Byzantium in the Ninth Century: Dead or Alive? (Aldershot 1998)

195–214.

32 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 34–5; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 56–8, lines 86–48.

33 The images of John are iconographically inconsistent even within this sequence: the third image depicts

a very tall and beardless younger man (fol. 47vb), while the final image simply represents a church. The

continuous textual narrative of John’s embassy to the Saracens and its outcome breaks down in the visual

narrative. This is a very different treatment of the narrative than, e.g., Leslie Brubaker’s discussion of ‘a

recognizable narrative progression’ in the Sacra Parallela (L. Brubaker, Vision and Meaning in Ninth-century

Byzantium: Image as Exegesis in the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus (Cambridge 1999) 38).

34 Tsamakda, The Illustrated Chronicle, 265; see, however, Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 58–9, 60–80.

35 For the changing attitudes to Theophilos in Byzantine texts of the late ninth-early tenth centuries, see

A. Markopoulos, ‘The rehabilitation of the emperor Theophilos’, in Byzantium in the Ninth Century: Dead or

Alive?, 37–49.

36 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 49–50; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 84–5.

�24

Elena Boeck

upon an icon and his destruction of a pagan idol are deliberately juxtaposed. The tight

compositional organization and iconographic consistency points to the planned nature of

this page-opening.

Some very curious aspects of narrative structure are embedded in each of the trio of

images and in their interrelationship. John’s virulent anti-iconic stance, narrated in the

text, is embodied on fol. 64va — John gives instructions to vandalize icons. In this

instance, the image faithfully reflects the words of the chronicle: ‘As for the impious

Jannes, he was shut up in some monastery and somewhere there he saw an icon set up;

it showed Christ our God, the Mother of God and the Archangels. He ordered his

personal deacon to climb up and put out the eyes of the sacred icons’ (Figure 2).37 The

viewer beholds a bearded cleric, armed with the Gospels, pointing his finger up to the

templon beam with four icons (two archangels flank the Virgin and Christ), a ladder

reaching up to the left-most icon, and a much-redrawn figure doing John’s bidding by

pointing a thin object at the Archangel’s eye. This figure became a particular challenge for

the artist: the outline drawing for the icon-offender was reworked several times, and an

adequate solution for his representation was not found.38 If the artist was not creating an

ad hoc representation of an image-destroyer, why was it so challenging to execute?

Figure 2 Madrid Skylitzes, folio 64va, © Biblioteca Nacional de España

37 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 49; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 84–7.

38 My close examination of the manuscript in Madrid in 2001 suggests that the figure underwent at least three

unsatisfactory stages of drawing.

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 25

The subsequent image depicts the lashing of a young, beardless half-naked man (the

deacon?). Although he is supposed to be John in the text and is labeled as John by the

rubricator, this is clearly not the bearded cleric of the previous or the following images.39

The images display a different narrative logic by punishing the minion instead of the

mastermind. This transposition allows the heretical cleric (John) to escape justice in the

visual narrative.

The right side of this page-opening is graced with another of John’s legendary

exploits in image-destruction. In this case, John directs an attack on a three-headed pagan

statue that stood in the Hippodrome (fol. 65) (Figure 3). The image, a companion-piece

to the defacing of an icon on fol. 64v, is fairly faithful to the text, reflecting the proper

number of pagan heads and their synchronized destruction. While in Byzantium the

Orthodox regularly visually associated their opponents with ‘idol worship’ (such as Paris.

gr. 74, fol. 135v), it was the domain and characteristic trait of Orthodox saints to expel or

destroy idols, such as St. Cornelius in the Menologion of Basil II (Vat. Gr. 1613, p. 125).40

Unlike the heretics of Byzantine iconography, including the wild-haired John the

Grammarian who worships an idol in the ninth-century Pantokrator psalter (fol. 165r), in

the Madrid Skylitzes, John, although lacking a halo, is represented destroying an idol.41

Although the text unswervingly labels John a heretic, portraying him as an intelligent

but dangerous and ungodly man, in the images John reveals a polyvalent persona and

multiple personalities: he is represented as a saint, an ambassador, a sorcerer and a

Saracen. In his three individual appearances in the visual narrative, which are not

connected to visual sequences, images of John are remarkable for their iconographic

inconsistency: while on fol. 57b a dignified white-haired and bearded bishop (John)

accedes to the patriarchal throne, on fol. 58a a younger man in secular garments (John

in the text) practices dish-divination in front of an emperor, and on fol. 49va a beardless

turbaned Saracen (John in the text) persecutes an Orthodox monk.42 Not a single visual

clue indicates that the three protagonists are in fact the same person or connects them to

39 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 49; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 88–92. This image is fol. 64vb. The composition precisely

repeats a stock image of punishment from fol. 43va (a public punishment in front of the emperor).

40 The issue of idolatry is at the heart of the iconoclast debate and Byzantine articulation of image theory. For

an excellent discussion of Byzantine conceptualization of idols, see Brubaker, Vision and Meaning, 20–1, 27–8,

39.

41 In the Skylitzes illustration, John’s hair is well-groomed and the idol that he points to is being destroyed,

as opposed to the Pantokrator image in which John prefers to worship a naked idol in opposition to David and

Beseleel, who honour the Tabernacle. For an extensive discussion of the Pantokrator image, see S. Dufrenne,

‘Une illustration “historique”, inconnue, du Psautier du Mont-Athos, Pantocrator 61’, Cahiers Archéologiques

15 (1965) 83–95. For a brief discussion of John in this image, see Walter, ‘Heretics’, 44–5; see also Piltz,

Byzantium in the Mirror, 30–7.

42 The turbaned figure is represented as a conventional Saracen in the rendering of this artist. Walter briefly

refers to this image in ‘Saints of Second Iconoclasm in the Madrid Skylitzes’, in Pictures as Language: How the

Byzantines exploited them (London 2000) 368–9.

�26

Elena Boeck

Figure 3 Madrid Skylitzes, folio 65, © Biblioteca Nacional de España

the haloed diplomat or iconoclast cleric discussed above. We can conclude that neither at

the design stage nor at the painting stage was John conceptualized as an arch-heretic.

Iconographic consistency, which is central to Byzantine image theory, is absent in

the images of John the Grammarian of the Madrid Skylitzes.43 The visual narrative gave

priority to certain plot-lines (such as diplomacy, divination, image-destruction) and

omitted others (such as John’s sexual escapades with nuns in cavernous settings), but was

unconcerned with the sustained legibility of John-the-heretic, or Orthodox condemnation

of John and his protégé the tyrant Theophilos. The visual narrative is blind to the

Orthodox vision of heretic John, and deaf to his names and epithets reiterated in the

Skylitzes text and Orthodox rhetoric.44 John’s iconographies in the Madrid Skylitzes are

43 Brubaker (Vision and Meaning, 39) noted: ‘Since similitude between image and archetype was a major

feature of iconophile theory, conscious use of traditional iconography deflected the possibility of any criticism

that the image was deviating from its prototype.’ See also D. Mouriki, ‘The portraits of Theodore Studites in

Byzantine art’, JÖB 20 (1971) 249–80; G. Dagron, ‘Holy images and likeness’, DOP 45 (1991) 33.

44 John’s accession to patriarchal power was represented as a stock image (fol. 57b) no different from

accessions of Orthodox patriarchs. Nothing indicates impious proceedings, as might be expected in an

Orthodox frame of reference, and in spite of the text suggesting that he ‘received the high-priesthood as a

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 27

also inconsistent, adhering neither to the text nor to the established iconography of John

(the marginal Psalters) or the generic trampled heretic of the Byzantine iconography.45

Even style does not bridge the cultural divide, for it is notably the ‘Byzantine hands’ that

present little familiarity with the Orthodox ideology.46

The restoration of Orthodoxy

Although the Skylitzes images muddle the memory of the arch-iconoclast, perhaps the

vision of history crystallizes with the ascendance of Orthodoxy. How are the triumph of

Orthodoxy and its saintly heroes, the patriarch Methodios and the empress Theodora,

celebrated? We quickly learn that the representations of St. Theodora and St. Methodios

in the Madrid Skylitzes also do not correspond to Orthodox iconographic formulae or to

Byzantine cultural expectations.47

Before examining the iconography of the two Orthodox heroes in the Madrid

Skylitzes, we shall consider their ritualized public remembrance and visualization within

the Orthodox milieu. Theodora and Methodios both became officially celebrated saints

in the second half of the ninth century.48 Their Orthodox achievements are formally

Continue

reward for impiety and faithlessness’ (Wortley, John Scylitzes, 43; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 72.45–6). John’s

multiple personalities are properly reflected in the captions that closely follow the text, and identify him as

‘Ioannes Synkellos’ in both representations of a saintly bishop. The Saracen on folio 49va is identified in

the captions as ‘Jannes the Philosopher’ (in the text he is called ‘Jannes’ at this point). The John practicing

dish-divination (fol. 58a) is now a figure in courtly attire, labeled by the captions as ‘Iannes Lekanomantes’,

though the text still calls him ‘Jannes’ (see Wortley, John Scylitzes, 43; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 72.66–7).

45 For images of trampled heretics in various media, see Walter, L’Iconographie des conciles dans la tradition

byzantine (Paris 1970).

46 Images of the iconoclast controversy in the Marginal Psalters would continue into the fourteenth century

(see C. Havice, ‘The Hamilton Psalter in Berlin: Kupferstichkabinett 78.A.9’ (unpublished doctoral thesis,

Pennsylvania State University, 1978) 213–9).

47 Kazhdan and Maguire noted: ‘It was in physiognomic details, then, rather than in illusionistic modeling

and perspective, that the “realism” of Byzantine portraiture resided for contemporary viewers’ (Kazhdan and

Maguire, ‘Byzantine hagiographic texts’, 8; see also Brubaker, ‘Byzantine art in the ninth century, 23–3;

A. Grabar, ‘Un calice byzantin aux images des patriarches de Constantinople’, Deltion ser. 4 (vol. 4)

(1964–1965) 46). Since consistency of images of saints was to be expected, it is therefore surprising that

Christopher Walter does not consider this issue for the images of the Madrid Skylitzes.

48 For a discussion of Methodios, see B. Zielke, ‘Methodios I (843–847)’, in R.-J. Lilie (ed.), Die Patriarchen

der ikonoklastischen Zeit: Germanos I – Methodios I (715–847) (Frankfurt am Main 1999) 183–260; see also

V. Grumel, ‘La politique religieuse du patriarche saint Méthode’, EO 34 (1935) 385–401. For Theodora, see

A. P. Kazhdan and A.-M. Talbot, ‘Women and iconoclasm’, BZ 84–85, Heft 2 (1991–1992) 391–408;

M. Vinson, ‘Life of St. Theodora the Empress’, in A.-M. Talbot (ed.), Byzantine Defenders of Images

(Washington, DC 1998) 353–82; see also M. Vinson, ‘Gender and politics in the post-Iconoclastic period: the

lives of Antony the Younger, the Empress Theodora, and the Patriarch Ignatios’, B 68 (1998) 469–515;

M. Vinson, ‘The life of Theodora and the rhetoric of the Byzantine bride show’, JÖB 49 (1999) 31–60.

�28

Elena Boeck

commemorated in the Synaxarion of Constantinople and the Synodikon of Orthodoxy.

Theodora is memorialized in the Synaxarion of Constantinople on February 11:49

And this remembrance of the empress Theodora who brought about Orthodoxy. The

blessed woman became the wife of emperor Theophilos the Iconoclast. She was not

a heretic like her husband. That man banished the holy Methodios, patriarch of

Constantinople, and appointed Ioannes the Lekanomantes the patriarch in his stead,

and burned the holy icons. Even though she did not dare to venerate the holy icons

openly, however she had them hidden in her bed-chamber, and during the night she

stood praying and entreating God in order that he would have mercy towards the

Orthodox. She gave birth to a son named Michael and brought him up in Orthodoxy.

After the death of her husband, she directly brought back the holy Methodios, and

they assembled the holy synod and anathematized the Iconoclasts, and deposed from

the [patriarchal] throne Ioannes, and brought into churches the holy icons. Then she

died leaving the empire to her son Michael.50

The text readily lends itself to oral recitation, the narrative is easy to follow and the

message is clearly communicated. The passage succinctly narrates her tribulations and

accomplishments, but emphasizes that the joint effort of Theodora and Methodios

brought success in the struggle for Orthodoxy. In a single entry, the participants on both

sides of the controversy are remembered and judged. Alexander Kazhdan and Alice-Mary

Talbot noted: ‘Theodora is given a ... substantial entry [in the Synaxarion] in which her

role in the restoration of the cult of images is duly emphasized.’51 Since the Synaxarion

entry was read every year on the day of the saint, Theodora’s name and deeds were

continuously publicly circulated and commemorated by the Orthodox.

Outside the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript, depictions of Theodora are rare.52 The one

extant Byzantine manuscript representation of Empress Theodora is preserved in the

Menologion of the Emperor Basil II (Vat. Gr. 1613, p. 392) — a manuscript of impeccable

Orthodox and imperial pedigree. Her iconic representation in the Menologion is that of

49

Vinson takes these commemorations as a sign of ‘the official rather than popular character of her cult.

...[S]he developed no popular following and nothing is known of her relics or any posthumous miracles’

(Vinson, ‘Life of St. Theodora the Empress’, 356). However, according to Alice-Mary Talbot, Theodora was a

very well-known saint. A reliable indicator of a saint’s currency among the people would be his or her inclusion

in the Synaxarion of Constantinople, which was read out to the congregation. This oral dissemination of

the information about the given saint would have reached many more people than a full-length vita since the

manuscript tradition for the Middle Byzantine saints is sparse. I am grateful to Dr Talbot for providing me with

this information.

50 The translation is mine from Synaxarium Ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae: Propylaeum ad Acta sanctorum

Novembris, ed. H. Delehaye (Brussels 1902) 458–60; hereafter cited as Synax. Cp.

51 Kazhdan and Talbot, ‘Women and iconoclasm’, 393.

52 Martha Vinson cites three currently known images of Theodora: in the Menologion of Basil II, a fresco in

the fourteenth century church of the Virgin Gouverniotissa (Crete) and the icon of the Feast of Orthodoxy (see

Vinson, ‘Life of St. Theodora the Empress’, 356 n. 79).

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 29

Figure 4 Vat. Gr. 1613, p. 392, © Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Vaticano)

an Orthodox, imperial saint: a standing, haloed empress, wearing a kite-shaped loros

decorated with a large cross, and a crown surmounted by a cross,53 with her left hand she

upholds a clipeated image of Christ54 (Figure 4). Theodora’s image distils the essential

attributes of an empress and a saint directly associated with the triumph of Orthodoxy.

The patriarch Methodios was also actively remembered in Orthodox texts and

images. He is commemorated in the Synaxarion of Constantinople on June 14 as ‘our

father among the saints, Methodios archbishop of Constantinople’ and as the person

who definitively refuted the heresy of Iconoclasm.55 He is acclaimed in the Synodikon of

Orthodoxy as ‘the true priest of God, champion and teacher of Orthodoxy’.56 Although

53 The costume of Theodora in the Menologion of Basil II recalls that of St. Helena. For the most recent

discussion of the imperial loros, the costume of Sts. Constantine and Helena, see M. Parani, Reconstructing the

Reality of Images: Byzantine Material Culture and Religious Iconography (11th–15th centuries) (Leiden 2003)

25–7, 38–41; see also P. Grierson, Catalogue of the Byzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and in

the Whittemore Collection, vol. 3, part 2: Basil I to Nicephorus III (867–1081) (Washington, DC 1973) 748, 125,

plate LXII 1a.4.

54 Grabar briefly mentions this image in his L’Iconoclasme Byzantin. Le Dossier archéologique (Paris 1984)

229.

55 Synax. Cp., 749–50. My translation.

56 J. Gouillard, ‘Le Synodikon de l’Orthodoxie’,TM 2 (1967) 110–11.

�30

Elena Boeck

both Methodios and Theodora are venerated in the annual Orthodox commemoration,

Methodios is a more prominent saint.

All surviving images of Methodios display an established iconography that is consistent across media, time and space. Already his earliest images preserved in the mosaics of

the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (dated between later ninth–early tenth century),57 and

miniatures in the ninth-century Sacra Parallela manuscript (Paris. gr. 923)58 reproduce the

same iconography. Cyril Mango thus describes the mosaic located in the north tympanum:

‘This Patriarch is represented ... as an old man with gray beard and moustache. He wore

a kind of hood tied in a bow under his chin, ornamented over the forehead with a red

cross and four segmenta.’59 Mango explains Methodios’ headgear as the result of suffering

inflicted upon him by Iconoclasts:

This distinctive headgear is in reality a bandage. It is alleged that during the iconoclast persecution under the Emperor Theophilus, Methodius’ jaws were broken and

his teeth pulled out; thus maimed, the future Patriarch was obliged to wear a bandage

round his head.60

Images of Methodios created for the principal church of the Byzantine Empire shortly

after the death of the patriarch already present a distinct, consistent visual identity and

iconic representation that accentuated his physical suffering for Orthodoxy.

The images of Methodios produced within the Byzantine/Orthodox cultural sphere

incorporate the most distinct and recognizable feature of Methodios’ iconography: his

bonnet/bandage (Figure 5). Frescoes of the saint survive in St. Kliment in Ohrid, dated

1294/1295, in a chapel of St. Euthymios of the church of St. Demetrios in Thessaloniki of

h ca.

1303, in the Staro Nagoricino,

and in Zi

h

a A thirteenth–fourteenth century manuscript

image (Mt. Athos, Mon. Kutlumusi, 412, fol. 129r) depicts a half-length, medallion

57 Cyril Mango dates the mosaics in the north tympanum to the late ninth–early tenth centuries (C. Mango,

Materials for the Study of the Mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul (Washington, DC 1962) 57). Robin Cormack

and Ernest Hawkins propose 870 as the date for the mosaic of the southwest rooms (see R. Cormack and E. J.

W. Hawkins, ‘The mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul: the rooms above the southwest vestibule and ramp’, DOP

31 (1977) 245). I should note that Christopher Walter noticed the difference between the appearance of

Methodios in the mosaics of Hagia Sophia and the Skylitzes. However, he did not analyse the implications of

this observation (Walter, ‘Saints of Second Iconoclasm’, 378).

58 I am grateful to Leslie Brubaker for bringing the Sacra Parallela images and the following bibliographical

reference to my attention (J. Osborne, ‘A note on the date of the Sacra Parallela (Parisinus Graecus 923)’, B 51

(1981) 316–7). According to Osborne (p. 316), the artist of the Sacra Parallela represented on fols. 131v, 278v

and 325r ‘the bishop ... with a close-fitting white hood that covers his head and ties beneath his chin’.

59 Mango, Materials for the Study, 52. The other mosaic ‘is preserved in the room over the southwest

vestibule’ (Mango, Materials for the Study, 52). Daniele Stiernon includes the representations of Methodios in

the Madrid manuscript in the list of his images as unproblematic (see Stiernon, ‘Metodio I’, in Bibliotheca

Sanctorum 9 (1961–1970), col. 392).

60 Mango, Materials for the Study, 53.

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 31

Figure 5 Hagia Sophia, Constantinople, St. Methodios.

Drawing by Justin Magnuson (after Fossati).

portrait of Methodios.61 Such stability of iconography is to be expected since, as noted

by Alexander Kazhdan and Henry Maguire, ‘similarity to the archetype was a principle

required by Byzantine aesthetics’.62

In the Madrid Skylitzes, visualizations of Theodora and Methodios are not bound by

Orthodox iconographic traditions, ‘Byzantine aesthetics’, the established sanctity of the

two protagonists or even the text of the chronicle. Unlike St. Theodora of the Menologion

of Basil II, Theodora of the Madrid Skylitzes images often lacks a halo and is not central

61 The iconographic relationship between manuscript representations and monumental images of the same

person is to be expected. See, e.g., the discussion of representations of the patriarch Nikephoros in the Hagia

Sophia and the Khludov Psalter by Cormack and Hawkins, ‘The mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul,’ 225; see also

Grabar, ‘Un calice byzantin’, 45–51; Grabar, L’Iconoclasme, 149.

62 A. Kazhdan and H. Maguire, ‘Byzantine hagiographical texts as sources on art’, DOP 45 (1991) 6. This

principle had philosophical and theological underpinning (see Belting, Likeness and Presence, 153; see also

G. Dagron, ‘Le culte des images dans le monde byzantin’, in J. Delumean (ed.), Histoire vécue du peuple

chrétien (Toulouse 1979) 144–59).

�32

Elena Boeck

in the reinstatement of Orthodoxy (fol. 63 va):63 instead a haloed, generic patriarch

(unnamed in the text and captions, presumably Methodios, but not conforming to his

Orthodox iconography) approaches the enthroned imperial couple64 (Figure 6). The

emperor motions to the patriarch, while the empress sits rigidly frontal and static.65

The chronicle text recounts the moment of restoration of Orthodoxy:

[Theodora] directed that all those who were distinguished by intelligence and learning, members of Senate or Synod, were to assemble in the palace of Theoctistos to

discuss and debate the question of orthodoxy. [fol. 63va] Everybody (so to speak)

gathered there; a great number of speeches were made, a multiplicity of attestations

from the holy scriptures was produced and the party of godliness carried the day. A

decree went out for the immediate restoration of the sacred icons.66

The active Theodora of the chronicle and the Synaxarion is made passive in the

image since she is neither accorded a halo nor assigned an active role in the proceedings.

The distinct ideology of the visual narrative is displayed by the addition of the adult

imperial male as an active protagonist.67 Even if this figure is intended to be Michael III,

for whom Theodora was a regent, he is not mentioned in this portion of the text and was

but a small child at the time.68 The marginalization of Theodora fits with the concerns of

the visual narrative, which appear consistently to make active women of the chronicle

text more passive or evil.69 Thus, in the officially commemorated key moment in her life

63 Theodora is represented privately venerating an icon once (fol. 45a). In the next image at the bottom of the

page, both Theodora and her iconoclast husband Theophilos are represented with haloes. During the reign of

Theophilos, she is at times represented with a halo (e.g., when conversing with holy men), but a number of

these images alter the sex of the empress and represent an emperor instead. Walter briefly noted, without

explaining, this gender confusion in ‘Saints of Second Iconoclasm in the Madrid Scylitzes’, 373. Grabar, on the

other hand, ignored the change of sex entirely, identifying the figure as a male (based on the text) (Grabar and

Manoussacas, L’illustration, 44).

64 The patriarch wears a polystaurion. For a discussion of the polystaurion, see C. Walter, Art and Ritual of

the Byzantine Church (London 1982) 14–6. Tsamakda (The Illustrated Chronicle, 107 n. 3) disagrees that this

is Methodios, while Grabar and Manoussacas considered this figure as a representation of Methodios (see

Grabar and Manoussacas, L’illustration, 49). Had the established Byzantine iconography been used to represent

the saint, there would be no doubts or questions about visual legibility of this figure.

65 For the sake of proper historical chronology, it should be noted that the emperor Michael was 3 years old

when he succeeded to the throne (842–867), and Theodora served as the regent for 14 years (842–856). Her

position as the primary ruler is reflected on her coins (see W. Wroth, Catalogue of the Imperial Byzantine Coins

in the British Museum, vol. 2 (London 1908) 429–30, pl. XLIX, #14, 15, 16; see also Grierson, Catalogue of the

Byzantine Coins, vol. 3, part 1, 454–7, 461–3).

66 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 49; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 83.50–6.

67 Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 71.19–27.

68 No iconic referent to the triumph of Orthodoxy is present in the image, nor, given the gravity of the

proceedings, is the image constructed on the model of an Orthodox council. For representations of councils

(including images in the Madrid Skylitzes), see Walter, L’Iconographie des conciles.

69 Boeck, ‘The art of being Byzantine’, 99–100.

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 33

Figure 6 Madrid Skylitzes, folio 63va, © Biblioteca Nacional de España

within the Orthodox narrative, the importance of Theodora is played down and denied

active agency, despite her centrality in the Skylitzes text.

The established Orthodox iconography of the patriarch Methodios is likewise

ignored or disregarded in the visual narrative of the Madrid manuscript, despite the clear

reference to the bodily injuries of St. Methodios in the Skylitzes text.70 The momentous

triumph of Orthodoxy celebrated in the text is re-imagined as an iconless, mundane

exchange between stock figures. 71

Miraculous intervention or misogynistic exposure?

The ultimate triumph of Orthodoxy climaxes in a sexually explicit sequence with

the Orthodox patriarch Methodios publicly exposing his lack of genitalia. The dense

visual sequence gradually unfolds an allegation of an illicit affair leveled against the

Patriarch by iconoclasts: the six images play out on two page-openings and expose the

peculiar interests of the visual narrative that prioritizes sensational over saintly, and

70 Skylitzes stated: ‘[T]he Empress gave the church the sacred and godly Methodius as patriarch, who still

bore in his flesh the marks of having been a confessor and martyr’ (Wortley, John Scylitzes, 49; Skylitzes, ed.

Thurn, 84.77–8).

71 The ‘restoration of the sacred icons’ mentioned in the text is not clearly articulated by this image. The

iconless restoration of icons in the visual narrative is somewhat puzzling since the artists ably represented icons

in images when an icon is specifically mentioned in the text in incidents that involved concrete and physical

interaction between an individual and an icon (painting, veneration, destruction, etc.). A number of these

images have become popular in scholarship, such as fol. 44v, fol. 45a, and fol. 50b.

�34

Elena Boeck

misogynistic over miraculous. The chronicle, meanwhile, narrates the final triumph of

Orthodoxy, the ultimate defeat of John the Grammarian, and highlights a miraculous

saintly intervention.72

The visual intrigue commences on folio 65v with a poorly preserved image that

includes two groups of three seated men flanking a standing female figure, clearly a

recipient of their instructions. The text preceding the image informs the reader:

[John and his supporters] pieced together a false accusation against Methodius in an

attempt to bring that blameless man into disrepute and thus demoralize the multitude

of the orthodox. They corrupted a woman with a large amount of gold and promises

if she would fall in with their plans. ... They persuaded her to denounce the holy man

before the Empress and the Emperor’s tutors, saying that he had consorted with her.73

The conspiracy narrated in the text is made transparent in the image with the privacy

of the gathering conveyed by a continuous architectural backdrop. Furthermore, the

woman is clearly established as both the central figure and an agent of others’ will. The

subsequent image swiftly publicizes the intrigue, bringing the accusers and the accused

face to face in the imperial presence. Although the empress is spatially distanced from the

proceedings (she is framed by an architectural setting), imperial involvement is expressed

by her gestures to the two groups: the patriarch, backed by the clergy, stands closer to

the throne, while a lay group displays the ‘corrupted’ woman at its centre and forefront

(fol. 66a). The chronicle sets up the confrontation:

An awesome tribunal was immediately constituted, of laymen and clerics. The devout

were in evidence, cast down in grief and sorrow — while the impious, far from

absenting themselves, were there in force, thinking that the church of the orthodox

was about to be plunged into unusual and severe disgrace. [fol. 66a]74

The visual arrangement of the opposing groups of laity and clergy clearly captures the

physical standoff, but the ideological standoff that underpins the Orthodox struggle is

absent from the image: though the iconographically consistent key participants are shared

in both narratives — the empress, the patriarch and the accuser — the image does not

mark the Orthodox with haloes.

The climactic pinnacle of the patriarch’s public exposure comes next75 (fol. 66b)

(Figure 7). The text informs the reader:

Wishing to frustrate the hopes of the godless, to relieve the devout of the burden of

shame and to ensure that he not be a stone of stumbling to the church, paying no

72 Also see Walter, ‘Saints of Second Iconoclasm’, for a somewhat problematic discussion of Methodios.

73 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 51; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 86–7.51–7.

74 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 51; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 87.57–60.

75 Visual continuity between the two images is created by their position on the same page, and the nearly

identical placement of the empress in both images.

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 35

Figure 7 Madrid Skylitzes, folio 66b, © Biblioteca Nacional de España

attention to the crowd, he shook off his garments and this man who was worthy of

all respect and honour exposed his private parts to the gaze of all the on-lookers. It

was now revealed to everybody that [his genitals] were atrophied by some disease and

totally incapable of performing their natural function. [fol. 66b]76

We may well wonder what is more remarkable in the relationship between text and image

in this instance — that the patriarch, who lacks a halo, is represented having lifted his

robes to reveal his groin area and prove that he was incapable of fathering a child (as a

result of a miraculous castration that is subsequently discussed in the text) or that the

designer of the visual narrative was so attentive to this particular episode.

The extraordinary display of patriarchal nudity (he is represented lacking genitalia)

should be evaluated in the broader context of both the manuscript and the surviving

corpus of Byzantine art. What types of images feature nudity in this manuscript? Except

for images of baptism, representations of partial and full nudity appear 24 times. Consistently, nudity is a shameful state imposed upon male outcasts such as prisoners, tortured

enemies, criminals, demons and the murdered emperor Romanos Argyros.77 In a study of

76 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 51; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 87.66–73.

77 Partial and full nudity appears in the following images of the manuscript (aside from the saintly patriarch):

fol. 41 a, fol. 43 va, fol. 64vb, fol. 65, fol. 68 v, fol. 98 v, fol. 101 a, fol. 112b, fol. 129vb, fol. 130, fol. 131b, fol.

131c, fol. 134va, fol. 134 vb, fol. 135a, fol. 136c, fol. 169, fol. 172 vb, fol. 175, fol. 182, fol. 206 va, fol. 223, fol.

225va.

�36

Elena Boeck

the human figure in Byzantine art, June and David Winfield have observed: ‘The nude

figure is not common in Byzantine works but it is retained where the narrative truth

requires it.’78 Methodios’ exposure was at the heart of the story. Does the nudity of the

saintly patriarch Methodios in this context signal shame or endurance in the face of

adversity?79 It is not immediately heroic; however, unlike the other, passively nude figures,

he actively exposes himself.

The nudity of Methodios should be contextualized within the entire visual sequence

— most notably the subsequent image and a visual void created by the designer of the

visual narrative. On the next page-opening, the visual sequence advances to the resolution

of the intrigue: the supporters of the now fully clothed patriarch embrace him and

celebrate with animated gesticulation on fol. 66va, in close accordance with the text.80 At

this point, the parallel structure between text and images in recounting central moments of

the intrigue against the patriarch Methodios collapses and the two narratives diverge. The

chronicle expounds at length the miraculous nature of Methodios’ emasculation, but the

extraordinary miracle is omitted from the visual narrative:

One of his closer friends came up to him and quietly questioned the Patriarch,

wishing to know how it came about that his genitals were withered away. In reply,

the latter explained the matter from the very beginning: I had been sent to the pope in

Rome in connection with the proceedings which had been instituted against

Nicephoros, the most holy patriarch. While I was staying there, I was harassed by the

demon of fleshly-desire. Night and day it never stopped titillating me and inciting me

to the desire for sexual congress. I was so inflamed that I knew it was nearly all over

for me, so I entrusted myself to Peter, the chief apostle, begging him to relieve me of

that fleshly appetite. By night, he [came and] stood beside me. He touched his right

hand to my genitals and burned them, assuring me that henceforth I would no longer

be troubled by the appetite for carnal delight. I awoke in considerable pain, and

found myself in the condition which you have witnessed.81

78 J. Winfield and D. Winfield, Proportion and Structure of the Human Figure in Byzantine Wall-painting

and Mosaic (Oxford 1982) 41, see also 42–7. For nudity in Byzantine art, see H. Maguire, ‘The profane

aesthetic in Byzantine art and literature’, DOP 53 (1999) 200–3; see also B. Zeitler, ‘Ostentatio genitalium:

displays of nudity in Byzantium’, in L. James (ed.), Desire and Denial in Byzantium (Aldershot 1999) 185–201.

For the representation of partially nude pagan idols, see N. P. Ševcenko,

The Life of Saint Nicholas in Byzantine

h

Art (Torino 1983) 132–3. Walter refers to ‘the calumny’ of the patriarch, but does not analyze the image or

discuss the omission of St. Peter (see Walter, ‘Saints of Second Iconoclasm’, 376–7).

79 For a discussion of saints, sex and nudity, see A. Kazhdan, ‘Byzantine hagiography and sex in the fifth to

twelfth centuries’, DOP 44 (1990) 131–43; see also A.-M. Talbot, ‘Epigrams in context: metrical inscriptions on

art and architecture of the Palaiologan era’, DOP 53 (1999) 87–8.

80 Preceding the image the text narrates: ‘This greatly dismayed those who rejoiced in iniquity and the

false-accusers, but it filled the devout with gladness of heart and rejoicing. They rushed upon him with

uncontainable glee, embracing and hugging him; they simply were unable to control their excessive joy.’

(Wortley, John Scylitzes, 51; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 87.73–6).

81 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 51; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 87–8.76–88.

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 37

This lengthy account of St. Peter’s miraculous intervention that enhanced the status of

Methodios, was transformed into a visual void. This omission eliminates the active,

hands-on divine endorsement of the saintly and Orthodox patriarch, excises St. Peter from

the visual narrative, and reveals a surprising lack of interest in a powerful miracle.

The visual narrative spins the patriarchal display, twisting a virtuous affirmation of

divinely sponsored victory into an ambiguous image. Because the miraculous emasculation

of the patriarch Methodios was omitted from the visual narrative, his public display as a

eunuch stands for the entire miracle.82 In this case, the visual evidence (his lack of a halo)

correlates closely with the structural evidence (omission of the miracle). Methodios’

genitals reveal the deliberate and distinct orientation of the visual narrative: the bodily

exposure alone was lifted out of its broader heroic Orthodox context articulated by the

text.

The conclusion of this visual sequence muffles the divinely sanctioned Orthodox

triumph.83 The castigation of the female accuser concludes the visual sequence (fol. 67),

giving priority to the corporal punishment of a treacherous woman over the triumph of

the Orthodox party. In the chronicle, the coerced recanting by the false-accuser was but a

small part of the extensive triumph of Orthodoxy and the punishment of the impious. The

Skylitzes text closes the intrigue with the annual celebratory procession of the triumph of

Orthodoxy in Constantinople:

The false-accusers would have been handed over to be punished accordingly, but the

Patriarch, imitating his own Lord, had the forbearance to request that the charges be

staid. He asked that their only retribution and punishment should be that, each year,

at the Feast of Orthodoxy, they should process with lights from the Church of the

all-pure [Mother of God] at Blachernae to the divine Church of the Holy Wisdom

and hear the anathema with their own ears; which custom was maintained as long as

they lived.84

The topography of the ceremony in the Skylitzes text corresponds to its description in

De Ceremoniis of Constantine Porphyrogennitos, who dedicated an entire chapter to

the account of this feast.85 Porphyrogennitos named the patriarch Theophylact as a

82 It is possible that his status as a eunuch could have complicated the acknowledgement of his saintliness,

even though, as Kathryn Ringrose noted: ‘God, through St. Peter, seems to have approved the crucial act

[i.e., emasculation]!’ (K. M. Ringrose, The Perfect Servant: Eunuchs and the Social Construction of Gender

in Byzantium (Chicago, IL/London 2003) 125). For a discussion of eunuchs and sanctity, as well as recent

bibliography on the subject, see Ringrose (The Perfect Servant, esp. 112–27). See also M. Mullett, ‘Theophylact

of Ochrid’s In Defence of Eunuchs’, in S. Tougher (ed.), Eunuchs in Antiquity and Beyond (London 2002)

177–98.

83 It is not the only time when the divine involvement (expressed through saintly participation) is concealed

by the selection process of the visual narrative (see Boeck, ‘The art of being Byzantine’, 204).

84 Wortley, John Scylitzes, 52; Skylitzes, ed. Thurn, 88.4–11.

85 A. Vogt, ed., Le livre des cérémonies, I (Paris 1935), Chapter 37 (28) 145–8; see also D. E. Afinogenov,

‘Povest o proshchenii imperatora Feofila’ i torzhestvo pravoslaviia (Moscow 2004) 63–77, 162–4.

�38

Elena Boeck

participant in the ceremony, thus confirming the active performance of the ritual in

his own time.86 The visual narrative actively re-visions the text by converting the longestablished and continuously celebrated Feast of Orthodoxy into yet another visual void.

It is very difficult to imagine that a Byzantine patron would deliberately omit from

visual commemoration the historical origin of one of the more significant celebrations in

the Byzantine liturgical calendar.

The visual exclusion of an annual Constantinopolitan ritual indicates that it did not

hold much meaning or interest for the patron of the visual programme of the Madrid

Skylitzes. This example serves as yet another reminder that there is more to the visual

narrative than what we see. Even if the facts that Iconoclasts are assigned symbols of

sanctity and Orthodox heroes such as Methodios are deprived of their saintly attributes

could be dismissed as careless mistakes, within the traditional framework there is no

satisfactory explanation for the deliberate obscuration of the triumph of Orthodoxy in the

visual narrative.

A Comnenian commission?

Is it possible that a vision of Byzantine history that so easily ignores Orthodox concerns

and defies Orthodox conventions could be produced for imperial consumption during

the age of Alexios I Komnenos? From the inception of his reign, Alexios I actively

fashioned the image of a ‘defender of Orthodoxy’, thus shrewdly building and reinforcing

his imperial legitimacy.87 During the period in which the Skylitzes prototype is presumed

to have originated as an imperial commission, manifold heresies commanded special

attention of the emperor. The history of Alexios penned by his daughter Anna Komnene

insistently promoted the image of the emperor as the upholder of Orthodoxy. We

learn that Alexios acquainted himself with the impious directly: he presided over the

trial of John Italos in 1082,88 and unsuccessfully taught Neilos the wrong of his

86 Vogt, Le livre des cérémonies: commentaire, I, 162–4.

87 L. Clucas, The Trial of John Italos and the Crisis of Intellectual Values in Byzantium in the Eleventh

Century (Munich 1981) 3. See also R. Browning, ‘Enlightenment and repression in Byzantium in the eleventh

and twelfth centuries’, Past and Present 69 (1975) 14. For the many challenges and open questions in interpreting Alexios and his legacy, see M. Mullett, ‘Introduction: Alexios the enigma’, in M. Mullett and D. Smythe

(eds), Alexios I Komnenos (Belfast 1996) 1–12; see also M. Angold, The Byzantine Empire, 1025–1204: a

Political History (London 1984); P. Lemerle, Cinq études sur le XIe siècle byzantin (Paris 1977); F. Chalandon,

Essai sur le règne d’Alexis Ier Comnène (1081–1118) (New York 1960). The frequency of anti-heretical trials is

quite remarkable, as noted by Robert Browning in ‘Enlightenment and repression’, 19. Also see Jean Gouillard,

‘L’hérésie dans l’empire byzantin des origines au XIIe siècle’, TM 1 (1965) 299–324. For the broad consideration

of heretics and heresies in the Alexiad, see D. Smythe, ‘Alexios I and the heretics: the account of Anna

Komnene’s Alexiad’, in Alexios I Komnenos, 232–59.

88 Annae Comnenae Alexias, ed. D. R. Reinsch and A. Kambylis (Berlin/New York 2001); The Alexiad of

Anna Comnena, trans. E. R. A. Sewter (Harmondsworth 1969); see also F. I. Uspenskii, ‘Deloproizvodstvo po

obvineniiu Ioanna Itala v eresi’, Izvestia Russkago Archeologicheskago Instituta v Konstantinopole 2 (Odessa

1897) 30–66. For the extensive discussion, see Clucas, The Trial.

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 39

ways.89 The emperor personally interrogated Bogomils and held long discussions with

their leader Basil, whose speeches were secretly recorded. 90 Based on this evidence, Basil

was burned at the stake and his followers jailed.91 The routing of the Bogomils was

Alexios’ ‘final triumph’.92

The Comnenian triumphs of Orthodoxy were not confined to the punishment of

heretics alone. Alexios positioned his achievements within the broader historical context

of the Orthodox triumph over iconoclasts: the emperor patronized the revision and updating of the Synodikon of Orthodoxy,93 with condemnations of the newly crushed heresies

incorporated into the revised Synodikon.94 The emperor also commissioned Euthymios

Zigabenos to compile and publicize a didactic, Orthodox and encyclopedic work — the

Dogmatic Panoply — characterized by Anna Komnene as ‘a list of all heresies, to deal

with each separately and append in each case the refutation of it in the texts of the holy

fathers’.95 Zigabenos deliberately linked the Comnenian present with the ninth-century

past by connecting the Bogomils to the Iconoclasts: ‘[T]hey [the Bogomils] banish all pious

emperors from the fold of Christians, and they say that only the Iconoclasts are orthodox

and faithful, especially Copronymous.’96 Would it not be unthinkable in this polarized

climate to portray iconoclasts with haloes and turn key moments of Orthodox triumph

into visual voids?

The acute interest of Alexios I in upholding and enforcing Orthodoxy is manifested

not only in verbal, but also in visual rhetoric. Jeffrey Anderson has argued that the

Barberini Psalter (Vat. Barb. Gr. 372) was produced for Alexios I in the context of another

89 Alexiad 10.1.1–5 (Sewter, 293–5).

90 Alexiad 15.8.5–6 (Sewter, 498).

91 Alexiad 15.10.4 (Sewter, 504).

92 Alexiad 15.10.5 (Sewter, 504).

93 The Synodikon of Orthodoxy was aptly described by Clucas as ‘the official catalogue of condemned

heresies and approved rulings of the Byzantine Church, beginning with the original anathemas read out against

the vanquished Iconoclasts in 843’ (Clucas, The Trial, 2).

94 V. A. Moshin, ‘Serbskaia redaktsiia sinoda v nedeliu pravoslaviia. Analiz tekstov’, VV 16 (1959) 341–2; see

also J. Gouillard, ‘Le Synodikon de l’Orthodoxie’, TM 2 (1967) 1–316; J. Gouillard, ‘Nouveaux témoins du

Synodikon de l’Orthodoxie’, AB 100 (1982) 459–62.

95 Alexiad 15.9.1 (Sewter, 500). The Dogmatic Panoply is the only securely established manuscript commission of Alexios I. This book indisputably held a place of importance in the imperial library, as attested by

two surviving copies: both include a frontispiece miniature of the emperor presenting the book to Christ, thus

signaling the imperial and divine approval of the work. The two surviving copies are Vat. Gr. 666 and Moscow

Hist. Mus. Synodal Gr. 387. For a more detailed discussion of these manuscripts and the identity of the imperial

figure, see I. Spatharakis, The Portrait in Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts (Leiden 1976) 122–9; P. Magdalino

and R. Nelson, ‘The emperor in Byzantine art of the twelfth century’, BF 8 (1982) 149–51; see also L. Rodley,

‘The art and architecture of Alexios I Komnenos’, in Alexios I Komnenos, 344, and the discussion of the

Barberini Psalter below.

96 Zigabenos, ‘Dogmatic panoply against the Bogomils’, 188. On Zigabenos, see M. Jugie, ‘La vie et les

oeuvres d’Euthyme Zigabène’, EO 15 (1912) 215–25.

�40

Elena Boeck

confrontation with heresy,97 but this time the emperor was charged with iconoclasm by

the bishop Leo of Chalcedon in a long-running controversy lasting from 1081 to 1095.98

During grave fiscal crises ‘sacred objects no longer in use’99 were appropriated into

the imperial treasury in 1081/1082, 1087 and 1091,100 but Leo viewed the despoliation of

the religious images as a form of iconoclasm.101 Anderson asserts the propagandistic

nature of the commission of the Barberini Psalter as ‘an affirmation of the Emperor’s

orthodox position on the worship of images’.102 This hypothesis is tempting, since the

Barberini Psalter revives the ninth century ‘visual polemics’103 between the Orthodox and

iconoclasts.104

Given the unswervingly Orthodox interests and patterns of patronage of Alexios I in

repeatedly linking Comnenian and ninth-century Orthodoxies, we should expect similarly

celebratory displays of Orthodoxy and its heroes in the Skylitzes history if we are to put

credence in the genesis of this manuscript from a Constantinopolitan imperial prototype

c.1100. Instead, we are confronted with a visual narrative that casually assigns iconoclasts

haloes, denies the Orthodox markings of sanctity and fails to distinguish the miraculous

97 J. Anderson, ‘The date and purpose of the Barberini Psalter’, Cahiers Archéologiques 31 (1983) 35–67. This

attribution was first proposed by E. De Wald in ‘The Comnenian portraits in the Barberini Psalter’, Hesperia

13 (1944) 78–86. The bibliography on this subject is thoroughly covered by Anderson in ‘The date and purpose’.

On folio 5 of the Barberini Psalter, an imperial family is represented with the young successor placed centrally

between his parents. This miniature makes this an unambiguously imperial manuscript (as either a commission

or a gift). For problems of imperial representation, see I. Spatharakis, ‘Portrait falsifications in Byzantine

illuminated manuscripts’, in Studies in Byzantine Manuscript Illumination and Iconography (London 1996)

45–8; see also Anderson, ‘The date and purpose’.

98 P. Stephanou, ‘Le procès de Léon de Chalcédoine’, OCP 9 (1943) 7. For an excellent analysis of the events,

see Anderson, ‘The date and purpose’, 56–9.

99 Alexiad 5.2.3 (Sewter, 158).

100 Anderson, ‘The date and purpose’, 56–7. For in-depth analysis of the events, see P. Stephanou, ‘Le procès

de Léon de Chalcédoine’, 5–64; see also V. Grumel, ‘Les documents athonites concernant l’affaire de Léon de

Chalcédoine’, Studi e Testi 123 (1946) 116–35.

101 For a recent discussion, see A. Weyl Carr, ‘Leo of Chalcedon and the icons’, in C. Moss and K. Kiefer

(eds), Byzantine East, Latin West: Art Historical Studies in Honor of Kurt Weitzmann (Princeton, NJ 1995)

579–84; see also J. Meyendorff, ‘Leo of Chalcedon’, in Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium 2: 1214–15; Anderson,

‘The date and purpose’, 57; V. Grumel, ‘L’affaire de Léon de Chalcédoine: Le décret ou “semeioma” d’Alexis

I Comnène (1086)’, EO 39 (1940) 333–41; P. Gautier, ‘Le synode de Blachernes (fin 1094). Étude

prosopographique’, REB 29 (1971) 213–84; P. Stephanou, ‘La doctine de Léon de Chalcédoine et de ses

adversaires sur les images’, OCP 12 (1946) 177–99.

102 Anderson, ‘The date and purpose’, 59.

103 ‘Visual polemics’ is part of the title of the book by Corrigan, Visual Polemics in the Ninth-century

Byzantine Psalters.

104 The Barberini Psalter contains five images pertaining directly to the iconoclast controversy, which makes

this manuscript stand out among the body of the surviving Marginal Psalters (see Anderson et al., The

Barberini Psalter, 15; see also Brubaker, ‘The Bristol Psalter’, 127–41). For discussion of the Khludov and

Barberini images, see Walter, ‘Christological themes in the Byzantine Marginal Psalters from the ninth to the

eleventh century’, REB 44 (1986) 284–5.

�Voids and visual narrative in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript 41

from the mundane. The very conceptualization and structure of the visual narrative are

out of place in the context of rigorous Comnenian Orthodoxy.

It is extremely unlikely that the visual programme of the Skylitzes, which is blind to

iconoclasm as a burning issue for both imperial and church leaders in the time of Alexios

Komnenos, could have been produced at the Byzantine court. The Madrid Skylitzes

appears tone deaf to the amazing chorus of contemporary voices testifying to the heavy

weight of Orthodoxy in cultural circles close to the Comnenian court. It would be inconceivable for a manuscript destined for the eyes of an Orthodox emperor to present such a

clouded and distorted vision of Orthodox history. Future studies will need to explain

and account for the manuscript’s ideological distance from the triumphant visions of

Orthodoxy prevalent in Byzantium. Both the visual and structural evidence discussed

here make a Sicilian origin of the visual programme more likely, especially when considered in tandem with stylistic diversity, paleography and misrepresentations of Byzantine

landmarks such as Hagia Sophia.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that the Madrid Skylitzes exhibits no evidence of

acquaintance with the established Byzantine iconography for Orthodox heroes and

Iconoclast villains. While in terms of training it is possible to identify artistic hands as

‘Byzantine’, beyond matters of style and stock poses there is little overlap with wellattested Byzantine ritual remembrance and iconographic representations of the triumph

of Orthodoxy. By not differentiating the virtuous from the villains, the visual narrative

displays a detached and distant view of Byzantine religious history.

The manuscript’s un-orthodox treatment of Orthodox themes underscores the complex structure of the visual narrative. Only by ignoring narrative sequences, visual voids

and structural inconsistencies can one conclude that ‘the selection of passages for illustration does not exhibit a concrete preference for specific contents’.105 The visual narrative

actively restructures and revisions Byzantine history. The devious, dangerous, larger-thanlife John the Grammarian of the chronicle and Orthodox imagination shatters into

unrelated scattered fragments in the visual narrative of the Madrid manuscript. Patriarch

Methodios does not resemble Methodios and the central event of his ascendancy over

the iconoclasts, his miraculous emasculation, is casually omitted. The decision to discard