Group

Reports

&

&

&

&

&

&

&

&

&

&

Journal of Perinatology ( 2002 ) 22, S27 – S32 doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7210807

The participants divided into four groups on days 3 and 4 of the

workshop to discuss and prepare recommendations on the following

four areas:

Components of community-based interventions to improve

perinatal and newborn outcomes?

Appropriate study designs and key variables for studies on

community-based interventions to improve perinatal and

newborn outcomes?

Steps and factors in moving from research to implementation?

Eliciting community mobilization and focused community

participation to promote neonatal health?

&

&

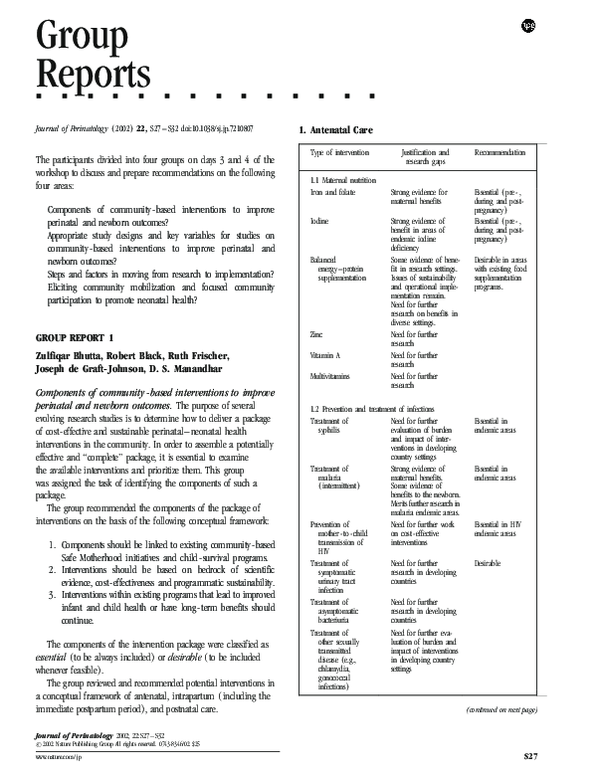

Type of intervention

1.1 Maternal nutrition

Iron and folate

Iodine

Balanced

energy – protein

supplementation

Zinc

Zulfiqar Bhutta, Robert Black, Ruth Frischer,

Joseph de Graft-Johnson, D. S. Manandhar

Vitamin A

1. Components should be linked to existing community-based

Safe Motherhood initiatives and child-survival programs.

2. Interventions should be based on bedrock of scientific

evidence, cost-effectiveness and programmatic sustainability.

3. Interventions within existing programs that lead to improved

infant and child health or have long-term benefits should

continue.

The components of the intervention package were classified as

essential (to be always included) or desirable (to be included

whenever feasible).

The group reviewed and recommended potential interventions in

a conceptual framework of antenatal, intrapartum (including the

immediate postpartum period), and postnatal care.

&

1. Antenatal Care

GROUP REPORT 1

Components of community-based interventions to improve

perinatal and newborn outcomes. The purpose of several

evolving research studies is to determine how to deliver a package

of cost-effective and sustainable perinatal–neonatal health

interventions in the community. In order to assemble a potentially

effective and ‘‘complete’’ package, it is essential to examine

the available interventions and prioritize them. This group

was assigned the task of identifying the components of such a

package.

The group recommended the components of the package of

interventions on the basis of the following conceptual framework:

&

Multivitamins

Justification and

research gaps

Recommendation

Strong evidence for

maternal benefits

Essential ( pre - ,

during and postpregnancy )

Essential ( pre - ,

during and postpregnancy )

Strong evidence of

benefit in areas of

endemic iodine

deficiency

Some evidence of benefit in research settings.

Issues of sustainability

and operational implementation remain.

Need for further

research on benefits in

diverse settings.

Need for further

research

Need for further

research

Need for further

research

1.2 Prevention and treatment of infections

Treatment of

Need for further

syphilis

evaluation of burden

and impact of interventions in developing

country settings

Strong evidence of

Treatment of

malaria

maternal benefits.

( intermittent )

Some evidence of

benefits to the newborn.

Merits further research in

malaria endemic areas.

Need for further work

Prevention of

on cost - effective

mother - to - child

interventions

transmission of

HIV

Need for further

Treatment of

research in developing

symptomatic

countries

urinary tract

infection

Treatment of

Need for further

asymptomatic

research in developing

bacteriuria

countries

Need for further evaTreatment of

luation of burden and

other sexually

impact of interventions

transmitted

in developing country

disease ( e.g.,

settings

chlamydia,

gonococcal

infections )

Desirable in areas

with existing food

supplementation

programs.

Essential in

endemic areas

Essential in

endemic areas

Essential in HIV

endemic areas

Desirable

(continued on next page)

Journal of Perinatology 2002; 22:S27 – S32

# 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved. 0743-8346/02 $25

www.nature.com / jp

S27

�Group Reports

(continued )

Type of intervention

Detection and

treatment of

bacterial

vaginosis

1.3 Behavioral issues

Birth preparedness

Education

into seeking

antenatal care

Counseling

on benefits

of exclusive

breastfeeding

Improved nutrition

in pregnancy

Recognition of

danger signs

for seeking

emergency

obstetric care

Education on

high risk

pregnancies,

e.g., previous

stillbirths or

perinatal deaths

(continued )

Justification and

research gaps

Recommendation

Need for further

research

Cord cutting and care

Essential

Essential

Essential

Essential

Training of the birth

attendant and families in recognition

of birth complications

that impact on newborn health and require speedy referral,

e.g., malpresentation,

prolonged labor,

eclampsia, antepartum hemorrhage,

cord prolapse

Hand - washing by birth

attendant, clean

surface

Care of the baby during

the delivery of the

placenta

� Drying and wrapping the baby

� Placing the baby on

the mother’s abdomen or to the breast

S28

Use of clean disposable blade

� Use of clean tie

� Clean cord and

leave uncovered

Basic resuscitation

including:

Justification and

research gaps

Recommendation

Further operational

research is needed to

assess the utilization of

safe birth kits versus

other approaches, and

the impact of cord

antisepsis on neonatal

outcomes

Essential

Need for further

operational research,

especially at the

domiciliary and

community level

Essential

Need for behavioral

and operational

research

Proven benefits

Essential

�

Essential

Tactile stimulation

Positioning

� Mouth - to - mouth

or bag - mask

resuscitation

Avoidance of inappro priate oxytocic use

�

�

Need for further

research on benefits

for perinatal / newborn

outcomes

Desirable

Immediate breast feeding

2. Intrapartum Care and Immediate Postpartum Care

The group underscored the importance and the need for skilled

health care at birth, but recognized that the nature of individuals

providing this care would differ according to health systems and

countries. The emphasis should be on the requisite skills necessary

for safe birth in domiciliary settings.

Type of intervention

Type of intervention

Justification and

research gaps

Recommendation

Well - known complications that impact on

fetal – neonatal survival

Essential

Essential

Need for research on the

optimal timing of cord

cutting in relation to

placental delivery

Essential

Essential

3. Postnatal Care

Type of intervention

Keeping the baby warm

� Delay bathing by

6 hours or more

� Kangaroo Mother Care

� Swaddling

� Co - bedding

� Warm room

Weighing the baby

Exclusive breast - feeding

Cup and spoon feeding of

expressed breast milk

for low birth weight

infants

Hygiene and skin care

Eye care

Justification and

research gaps

Recommendation

Need for operational

research

Essential

Need for research on

alternative methods

( e.g., anthropometry )

to identify low birth

weight babies

Proven benefits

Well - established

benefits

Desirable

Need for formative

and operational

research

Proven benefit

Essential

Essential

Essential

Essential in

endemic areas

Journal of Perinatology 2002; 22:S27 – S32

�Group Reports

(continued )

Type of intervention

Education of families

and caregivers for

recognition of danger

signs on care seeking

and referral of a sick

newborn

Education of families and

caregivers in recognition of danger signs for

neonatal sepsis and

care seeking / referral /

treatment

Treatment of

neonatal sepsis

Justification and

research gaps

Need for further research

into use of a clinical

algorithm to identify

sick newborns, domiciliary management of

the sick newborn, if

referral not possible.

Operational research

also needed on how to

overcome barriers to

identify sick newborns

and how to promote

effective referral

pathways

Need for research to

validate criteria of sepsis

in diverse settings.

Need for research on

microbiology of organisms causing sepsis

Several possibilities exist

for treatment of sepsis

Selection of antibiotics

should be based on

microbiology of organisms, national drug

policy, cost effectiveness

and feasibility of delivery. Need for research

into different approaches

for treating neonates

with sepsis in the community, including domiciliary management.

Recommendation

Essential

Essential

Key Outcome Indicators

The choice of outcome indicators depends on the duration

and size of the study. These two factors affect the likelihood of

achieving changes in outcome indicators such as neonatal mortality

rate. The indicators that are expected to change due to intervention

should be specified at the outset. If a process indicator is used as an

outcome, it should also be used in the estimation of sample size.

For studies on community-based interventions to improve perinatal and neonatal health, the following indicators were recommended:

Essential

Note: The group highlighted the need to consider approaches to

domiciliary management of the newborn in the context of the health

system. Thus, it is important to emphasize the need to strengthen

referral pathways, improve quality of care at the primary and

secondary referral centers, and ensure linkage with maternal

postnatal care.

GROUP REPORT 2

Saadet Arsan, Paul Arthur, Abdullah Baqui,

Simon Cousens, Ashok Deorari, Shams El Arifeen, David

Osrin, Izaz Rasul, Indira Narayanan

Appropriate study designs and key variables for studies on

community-based interventions to improve perinatal and

neonatal outcomes. In order to maximize the gains from different

studies, it is essential to have standardized design and methodology.

Only then can the results be compared and, possibly, pooled. There

should be an agreement on key outcome variables and date

collection methods: This group addressed these key issues.

Journal of Perinatology 2002; 22:S27 – S32

Study Design

The optimal study design to demonstrate the impact of an

intervention on a behavior or a health outcome is the randomized

controlled trial. Current knowledge about community care of

neonates is not at a stage where intervention packages can be taken

to trial without the need for randomization and controls. The use of

controls raises ethical and design issues. One way to address these

concerns is to introduce interventions in a stepwise fashion.

The packages of interventions should be examined for effectiveness, while individual interventions need to be tested for efficacy.

� Essential: Neonatal mortality rate

� Desirable: Perinatal mortality rate, stillbirth rate, early

neonatal mortality rate, late neonatal mortality rate, fresh

stillbirths plus neonatal mortality rate.

It was recommended that cost be estimated, as it is essential

descriptive information in these studies.

Depending on the scope of the study and the precision of the

evaluation tools employed, the following additional information may

be gathered:

Maternal morbidity

Fresh stillbirth/all stillbirths

Cause-specific neonatal mortality

Birth weight (or surrogates)

Proportion of low birth weight infants

Birth-weight-specific mortality

Proportion of preterm infants

Incidence of neonatal morbidities, especially birth asphyxia

and sepsis

� Delivery sites, skilled or unskilled care at birth

� Choice and use of providers, utilization of health system

resources

�

�

�

�

�

�

�

�

Process Indicators

One or more process indicators could be used as outcome variables.

Generating information on practices is more important than

information on knowledge; and observation or demonstration of

activities is preferable to reporting or recall of activities.

Qualitative assessment must be an integral part of the studies as

ethnographic investigation may yield extremely useful information

for the program.

S29

�Group Reports

The specific process indicators recommended were skilled health

care at birth, immediate care at birth, thermal control, clean

practices at birth, resuscitation, cord care, early initiation and

exclusivity of breast-feeding, eye care, immunization, recognition of

danger signs, care seeking, and postnatal care by a skilled provider.

Many of these indicators need further definition and validation.

Considerations in Data Collection

Data collection may be continuous or periodic. Both have their

advantages and disadvantages. A decision needs to be taken

beforehand whether specific information will be collected from the

control group or not. The process of data collection may affect the

outcomes in the control population. The greater the quantum of

process information collected, the higher the cost of the study and the

more intense the effect on the control group. One way to neutralize

this effect is to exclude informants from subsequent periodic

assessments. As far as possible, studies should develop their own

evaluation system and not rely on routinely collected data.

Studies need to take into consideration the issues of loss to followup, variable exposure to intervention, dispersion or congruity of

intervention and control areas, intra- and intercluster movement,

and problems of emigration or temporary movement of subjects. All

providers within the community should be enumerated.

Standard and accepted definitions and tools should be used. The

studies may address the development of additional necessary tools as

a part of their activities.

GROUP REPORT 3

Elaine Albernaz, Abhay Bang, Gary Darmstadt,

Judith Moore, N. C. Saxena, Uzma Syed

Moving from research to implementation. The ultimate aim of

action research is to develop interventions for incorporation into

health programs. However, all community-based research does not

necessarily lead to program-ready interventions and approaches.

This group was assigned the task of defining the attributes of

interventions that make them amenable to implementation in the

program setting and the steps required to achieve that.

Criteria

The decision to move from research to implementation depends on

several considerations:

1. Is the problem of sufficient magnitude and/or severity in

the population to take up the intervention on a

programmatic scale?

The importance of a given health problem varies from country

to country. There is no universal threshold of neonatal mortality

rate at which a program targeted to newborn infants needs to be

initiated. Each country should set national goals for neonatal

health indicators.

S30

2. Is the intervention effective?

The intervention should have been demonstrated as effective

under field conditions in more than one site and under more than

one set of conditions. There is often a need for an intermediate step of

effectiveness studies between the initial efficacy trial and

implementation. The intervention should potentially be able to

address the problem on a national level. The acceptable level of

impact depends on many factors such as the cost, the ease of

implementation and potential for adverse effects.

3. Is the intervention cost-effective?

The intervention should be cost-effective and affordable by the

country.

4. Is the intervention acceptable?

It is essential to ensure the acceptability of the intervention among

decision makers, professional leaders, health workers and the

community.

5. Is the intervention sustainable?

Sustainability is a fundamental issue in community programs.

Embarking on a program that cannot be sustained in the long

run does more harm than good to the cause. Vertical programs

may be more easily scaled up than an integrated, multicomponent

program, but sustainability may be compromised.

6. Is there an ethical urgency?

There is a threshold beyond which it is unethical to withhold an

intervention from the community that has impact and only a limited

chance of causing adverse effects.

Steps

After the above criteria regarding the intervention are met, the

following steps are required in order to effectively implement the

intervention in a program:

� Build consensus among political leaders and other

stakeholders that implementation of the intervention is

essential. Generating political will and momentum may be a

major bottleneck to the launch of a program. Therefore,

there is a need to take along all the stakeholders including

national and regional policy makers, professional groups,

human rights groups, women’s groups and the media.

Opinion makers who are likely to oppose the program

should be included in deliberations from the beginning.

� Select the implementing agency, which could be a

department within the government, private sector, or an

NGO, or a combination of these.

� Constitute a group that adapts the intervention to national or

regional circumstances. It is possible that some elements of

the package are dropped or modified.

� Prepare a blueprint for implementation of the intervention,

taking into account the burden of the problem, perceived

community demand for the intervention, resource needs,

health system strengths/weaknesses, private sector/community assets and available tools.

Journal of Perinatology 2002; 22:S27 – S32

�Group Reports

� Start the phase-wise implementation of the program. Initial

communities should be selected carefully to provide for a fair

chance of success of the program.

� Monitor and evaluate the program. There is a need to

regulate the implementation of the program to ensure that

the program improves over time. Aspects of the package may

lose relevance over time as the magnitude of the target

problem(s) changes, requiring fine-tuning of the program.

The above process will need to be repeated at the local level

to make microlevel adjustments.

health because infants are often born at home and the care of

newborns in developing countries is often conditioned by traditional

beliefs, practices, and behaviors that may require change for

improved outcomes. The deliberations of this group were focused on

the need, principles, and methodology of community mobilization.

Why Community Mobilization and Participation

� Focus of the program is on the infants of the community;

hence, its involvement is a moral and ethical obligation.

� Newborn essential care packages consist primarily of

GROUP REPORT 4

Nabeela Ali, Anthony Costello, Lisa Howard-Grabman,

Vinod K. Paul, Jose Martines

Eliciting community mobilization and focused community

participation to promote neonatal health. Community

acceptance and participation in health care programs is a

fundamental prerequisite for its sustainability and success.

Investigators engaged in community-based research aimed to be

translated into programs must build in a component of community

mobilization from the outset. This is particularly so for neonatal

�

�

�

�

behavior change, requiring changes in individual, family,

and community behaviors and norms.

Success of community-based interventions depends on

community acceptance of the interventions.

Involvement of communities in research planning, implementation of interventions and evaluation can help to reduce

lag time for implementation, upscaling, and expansion.

Communities can contribute resources that may not be

available to the health system alone.

Community involvement in monitoring and evaluation

provides community perspective on quality of care,

appropriateness, and feasibility of interventions.

Figure 15. The community action cycle for community mobilization (Courtesy, Lisa Howard-Graham ).

Journal of Perinatology 2002; 22:S27 – S32

S31

�Group Reports

� Community participation breaks barriers to implementation,

� Consider issues of coverage of all strata including those most

helps program teams to troubleshoot, and develop practical

solutions.

� Outcomes of community participation go beyond health to

include self-efficacy and collective efficacy, and strengthened

community capacity to identify priorities and address them.

� Community participation is the key to long-term sustainability of program interventions and outcomes.

affected by the problem with emphasis on marginalized or

disadvantaged groups.

Ensure appropriate involvement of ‘‘gatekeepers,’’ opinion

leaders, and decision makers (including private practitioners).

Develop strategies to ensure continuing community interest

in the initiative (e.g., identifying successes and celebrating

them).

Ensure that the team has a clear understanding of economic,

social, political, and cultural context.

Work in accordance with the community calendars and

schedules.

Make the program management culture as participatory and

open to supporting new approaches. Do not punish team

members for mistakes; learn from them.

Keep focused on the program goal; put a monitoring system

in place with community review of findings.

Ensure adequate contact with the community to maintain

desired level of action.

Determine your program policy and philosophy with regard

to incentives for community participation in the context of

long-term sustainability of the program and not for shortterm gains.

�

�

�

Some Basic Principles of Community Participation/

Mobilization

� Set specific goals around which to mobilize the community.

� Define your community (it could be just a ‘‘core group,’’ or

�

�

supporting groups and individuals, or a broader community).

� Be apolitical. Do not indulge in local politics.

� Be transparent and honest; explain the goals of the program

�

to the community and share what you can do and what you

cannot do.

Respect community values and concerns as well as

hierarchies and culture.

Define and redefine your role in relation to communities as

they strengthen their capacity in order to encourage growing

autonomy.

If you do not know why something is happening, ask

community members.

Be flexible. Not all communities are the same and not all

groups within communities are the same.

Define process objectives for community mobilization related

to underlying themes that contribute to the health problem

(e.g., exploring the value of newborns’ and mothers’ lives,

gender equity, shared responsibility for quality care).

Draw upon successful models in similar situations.

�

�

�

�

�

�

�

Community Action Cycle

Community action cycle describes the steps in community

mobilization. It consists of the following sequence of activities:

prepare to mobilize, organize community for action, explore the

health issues and set priorities, plan together, act together, evaluate

together and scale up. Figure 15 depicts the details of these steps.

�

Issues in Scaling Up

� The methodology needs to be affordable and feasible in order

to be scaled up.

� Consensus should be built around adopting a particular

model/approach.

� Partnerships are essential to achieve larger scale impact and

it is crucial to define goals of the partnership and program,

roles and responsibilities, coordination mechanisms, and

indicators of success/performance.

� Partners in scaling up could be social scientists, NGOs,

government, communities, private sector, economists, and

other technical specialists.

� Advocacy with the leaders is required to ensure acceptance of

the scaling-up initiative.

Gaps

Issues in Implementation of a Community Mobilization

Effort

� There are only a few examples of scaling-up experiences and

� Ensure that design is feasible and affordable on a large scale.

� Develop capacity of facilitators for community mobilization

community participation programs at different scales and in

different settings.

� Only a limited experience is documented on the impact of

community participation approaches combined with communication strategies such as social marketing, mass media,

and interpersonal communication and counseling.

� While estimating cost-effectiveness, the investigators often

overlook gains in community capacity as a part of the

broader benefit to the program.

through a combination of training and field experience.

(This is a technical discipline with a defined set of skills.)

� Foster community acceptance of the project and its team at

the outset.

� Build on other existing programs and activities in the

community.

� Build on prevalent positive practices in the community.

S32

approaches to scaling up in community mobilization.

� There is a paucity of research on impact evaluation of

Journal of Perinatology 2002; 22:S27 – S32

�

Ruth Frischer

Ruth Frischer