Received: 11 December 2018

|

Accepted: 17 April 2019

DOI: 10.1002/pan3.30

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Perspectives of ammunition users on the use of lead

ammunition and its potential impacts on wildlife and humans

Julia L. Newth1,2,3

Eileen C. Rees1

| Alice Lawrence1 | Ruth L. Cromie1 | John A. Swift4 |

| Kevin A. Wood1

| Emily A Strong1 | Jonathan Reeves1 |

Robbie A. McDonald3

1

Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge,

Gloucestershire, UK

Centre for Ecology and

Conservation, College of Life and

Environmental Sciences, University of

Exeter, Cornwall Campus, Penryn, Cornwall,

UK

2

3

Environment and Sustainability

Institute, College of Life and Environmental

Sciences, University of Exeter, Cornwall

Campus, Penryn, Cornwall, UK

John Swift Consultancy – Higher Wych,

Malpas, Cheshire, UK

4

Correspondence

Julia L. Newth, Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust,

Slimbridge, Gloucestershire, GL2 7BT, UK.

Email: Julia.Newth@wwt.org.uk

Handling editor: Steve Redpath

Abstract

1. Recent national and international policy initiatives have aimed to reduce the exposure of humans and wildlife to lead from ammunition. Despite restrictions, in the

UK, lead ammunition remains the most widespread source of environmental lead

contamination to which wildlife may be exposed.

2. The risks arising from the use of lead ammunition and the measures taken to

mitigate these have prompted intense and sometimes acrimonious discussion between stakeholder groups, including those advancing the interests of shooting,

wildlife conservation, public health and animal welfare.

3. However, relatively little is known of the perspectives of individual ammunition

users, despite their role in adding lead to the environment and their pivotal place

in any potential changes to practice. Using Q‐methodology, we identified the perspectives of ammunition users in the UK on lead ammunition in an effort to bring

forward evidence from these key stakeholders.

4. Views were characterised by two statistically and qualitatively distinct perspectives: (a) Open to change—comprised ammunition users that refuted the view that

lead ammunition is not a major source of poisoning in wild birds, believed that

solutions to reduce the risks of poisoning are needed, were happy to use non‐lead

alternatives and did not feel that the phasing out of lead shot would lead to the

demise of shooting; and (b) Status quo—comprised ammunition users who did not

regard lead poisoning as a major welfare problem for wild birds, were ambivalent

about the need for solutions and felt that lead shot is better than steel at killing

and not wounding an animal. They believed opposition to lead ammunition was

driven more by a dislike of shooting than evidence of any harm.

5. Adherents to both perspectives agreed that lead is a toxic substance. There was

consensus that involvement of stakeholders from all sides of the debate was desirable and that to be taken seriously by shooters, information about lead poisoning

should come from the shooting community.

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

© 2019 The Authors. People and Nature published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of British Ecological Society

People and Nature. 2019;00:1–15.

wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/pan3

|

1

�2

|

NEWTH ET al.

People and Nature

6. This articulation of views held by practitioners within the shooting community

presents a foundation for renewing discussions, beyond current conflict among

stakeholder and advocacy groups, towards forging new solutions and adaptation

of practices.

KEYWORDS

ammunition, environmental contaminants, hunters, hunting, lead, Q methodology, shooting,

waterfowl

1 | I NTRO D U C TI O N

sport, pest management and hunting for food. Shooting, therefore,

involves heterogeneous communities of participants (Kanstrup,

There is international recognition of the risks presented by lead to the

2019). Furthermore, stakeholder groups in discussions about lead

health of humans and wildlife (Arnemo et al., 2016; Green & Pain, 2015;

extend beyond shooting, encompassing organisations advancing

Pain, Cromie, & Green, 2015; Stroud, 2015). Following regulation to

wildlife conservation, public health and animal welfare (Cromie et

remove lead in the environment from other sources such as paint and

al., 2015). This discussion, as played out among membership organi-

petrol (Stroud, 2015), recent policies have aimed to reduce the exposure

sations and vocal commentators in public arenas, is dominated by a

of humans and wildlife to lead from ammunition (IUCN, 2016; Stroud,

‘lead debate’ between those advocating retention of the Status quo

2015; UNEP‐CMS, 2014). Over the last 50 years, lead ammunition (pri-

(predominantly shooting and countryside management organisa-

marily shot) has been subject to legislative and other forms of regulation

tions) and those favouring stricter controls or phasing out of lead

in 33 countries world‐wide (Kanstrup, 2019; Kanstrup, Swift, Stroud,

ammunition and replacement with non‐toxic alternatives (predomi-

& Lewis, 2018; Stroud, 2015). Currently, two countries have total bans

nantly wildlife conservation organisations). This ‘lead debate’ has

on the use, trade and possession of lead shot: Denmark introduced leg-

become polarised in the UK and sits within a wider landscape of mis-

islation in 1996 (Kanstrup, 2006) and the Netherlands in 1993 (Avery

trust and tension between shooting and conservation organisations,

& Watson, 2009). Partial and total restrictions on the use of lead am-

despite their holding many conservation goals in common. There

munition for hunting have culminated in a range of experiences from

may also be a perception that moves to phase out the use of lead

different jurisdictions (Kanstrup, 2019). In Denmark, the proposed ban

ammunition are ‘anti hunting’ and part of a wider attack on shooting

initially received a negative reception from hunters. Resistance was mo-

and other legitimate field sports, leading to ratcheting up of regula-

tivated by concerns about safety and the quality and expense of the al-

tion and restrictions (Cromie et al., 2015; Thomas, 2015).

ternatives to lead shot, compounded by tensions between stakeholders

As with other environmental conflicts, the ‘lead debate’ has been

and a lack of organisational leadership (Kanstrup, 2015, 2019). Hunter

characterised by contested interpretations of the scientific evidence

attitudes became more positive with a widening appreciation of the en-

and can now be regarded as a sociopolitical issue (Arnemo et al.,

vironmental impacts of lead shot and the introduction of a new gener-

2016). Evidence from the natural sciences alone is often insufficient

ation of shot types (Kanstrup, 2019). In the UK, partial restrictions on

to resolve conflicts (Haas, 2004; Hulme, 2009; Luks, 1999; Saltelli,

the use of lead ammunition, particularly over wetlands and foreshores,

Giampietro, Avan, Ambientals, & Autonoma, 2015) and this appears

have been introduced to reduce morbidity and mortality of wildlife in

to be true in this case (Arnemo et al., 2016). Indeed, Byrd (2002) ar-

England in 1999 (HMSO, 1999, 2002a, 2003), Wales in 2002 (HMSO,

gues that without addressing the sociopolitical dynamics driving the

2002b), Scotland in 2004 (HMSO, 2004) and Northern Ireland in 2009

public discourse behind such conflicts, interventions based solely on

(HMSO, 2009). Despite these restrictions, lead ammunition remains the

science are likely to polarise people and result in politically unviable

most widespread and common source of environmental lead contami-

management plans. The origins of many conflicts are related to val-

nation to which wildlife might be exposed in the UK (Pain et al., 2015).

ues, changing attitudes and power relations (Raik, Wilson, & Decker,

2008) that have roots in social and cultural history (Redpath et al.,

1.1 | The ‘lead debate’

The risks arising from the use of lead ammunition and the measures

taken to mitigate these have prompted intense discussion between

stakeholder groups in the UK (Newth, Cromie, & Kanstrup, 2015).

Shooting is a long‐standing activity with established practices and

traditions and is undertaken for a variety of purposes, including

2013).

1.2 | The perspectives of ammunition users

Although the ‘lead debate’ could be characterised as an apparently

‘intractable conservation conflict’ (Redpath et al., 2013), played out

by large organisations, relatively little is known of the perspectives

�People and Nature

NEWTH ET al.

|

3

of individual ammunition users, despite their critical roles in (a) add-

the success of guidance and legislation and help guide organisations

ing lead to the environment; and (b) adopting, or not adopting, any

and commentators participating in debate. Enhanced dialogue may

potential changes to practice. Efforts by statutory agencies and

prevent misunderstandings about perspectives and motivations of

shooting and countryside management organisations to improve

those with differing viewpoints and encourage discourse about the

user compliance with regulations (e.g. through awareness‐raising

issue so that mutually agreeable compromises might be reached

activities such as the ‘Use Lead Legally’ campaign) have been largely

(Durning, 2005).

unsuccessful. Compliance with existing regulation remains gener-

Here, using Q‐methodology, we aim to identify the perspectives

ally poor in England (e.g. 77% of ducks were shot with lead shot in

of ammunition users in the UK in relation to the substance of the

winter 2013–2014; Cromie et al., 2015), some 13 years after the

‘lead debate’ in an effort to bring forward evidence from these key

introduction of regulations (HMSO, 1999), indicating that at least

stakeholders, who have influence over and are most affected by the

some shooting participants have not ‘bought‐in’ to the legislation or

issue.

guidance.

The success or otherwise of conservation interventions may

depend on whether and how the opinions of relevant individual

2 | M ATE R I A L S A N D M E TH O DS

stakeholders are understood and catered for (Bennett et al., 2017;

Madden & McQuinn, 2014; Redpath et al., 2013) and whether

A Q‐study involves a relatively small number of purposively se-

or not proposed solutions are perceived as appropriate (Zabala,

lected participants (usually 20–40 people) who are asked to rank, in

Sandbrook, & Mukherjee, 2018). Understanding the viewpoints and

order, a number of opinion statements about a specific topic (Cairns,

values of individuals with respect to issues important for conser-

2012). The rankings, known as ‘Q‐sorts’, are then analysed statis-

vation has multiple benefits (Curry, Barry, & McClenaghan, 2013;

tically using factor analysis to explore patterns or shared perspec-

Zabala et al., 2018), including identification of barriers or alignments

tives towards a topic. These ‘factors’, or social perspectives, are then

(Frantzi, Carter, & Lovett, 2009), improved assessment of the ef-

interpreted with the aid of contextual information gained through

fectiveness of policy and plans, improvement of public participa-

post‐sort interviews with all participants (Cairns, 2012).

tion and stakeholder dialogue (Cuppen, Breukers, Hisschemöller, &

Bergsma, 2010) and the facilitation of critical reflection (Zabala et

al., 2018) as well as an opportunity to resolve contentious issues

(Durning, 2005).

2.1 | Constructing the narrative for the debate (the

‘concourse’)

A concourse which contains expressions of potentially varied per-

1.3 | Q‐methodology in conservation conflicts

spectives of the topic (Webler, Danielson, & Tuler, 2009) was constructed using a ‘semi‐naturalistic approach’ (Cairns, 2012; Robbins

Q‐methodology uses a combination of quantitative and qualitative

& Krueger, 2000), whereby opinion statements were drawn from

techniques to identify and explore subjective attitudes, viewpoints

a combination of semi‐structured interviews with seven informed

and perspectives on a given topic (Stephenson, 1953; Watts &

individuals (Webler et al., 2009) and through review of written

Stenner, 2012). It combines the transparency of a structured quan-

materials (Stainton Rogers, 1995). The interviewees, all of whom

titative technique with the richer understanding of a qualitative ap-

were based in the UK, were purposively selected for their consid-

proach (Zabala et al., 2018). For contentious issues, Q‐methodology

erable professional knowledge of lead ammunition in relation to

may facilitate agreeable and compromise policy solutions in several

wildlife health, human health and shooting. They were not asked

ways. It may help decision‐makers to: (a) clarify issues, through

to rank statements for analysis. Written materials that included

deeper understanding of the sometimes hidden interests and beliefs

the broad subjects of lead ammunition, related impacts on wildlife

of stakeholders; (b) identify competing definitions of problems and

and humans, associated politics and non‐toxic/non‐lead ammuni-

solutions and reveal commonalities between them; and (c) as a con-

tion were selected for review. The scope was limited to informa-

sequence, forge new solutions (Durning, 2005). Within conservation

tion relevant to the UK only. Materials included published papers,

conflict scenarios, Q‐methodology has identified shared and oppos-

perspectives and reports, articles in shooting and conservation

ing discourses relating to the management of large, terrestrial wild-

magazines, content from shooting and conservation blogs, web-

life (e.g. Bredin, Lindhjem, Van Dijk, & Linnell, 2015; Price, Saunders,

sites and forums, texts of international agreements and minutes of

Hinchliffe, & McDonald, 2017; Zabala et al., 2018), with the aim of

meetings and transcripts of parliamentary debates related to the

reaching acceptable solutions. Although some conservation con-

issue of lead shot. This multisource approach was used to capture,

flicts might be well‐suited to the application of Q‐methodology, such

as far as possible, the diversity of opinion and to provide a breadth

use remains relatively uncommon and the method has rarely been

of personal and organisational perspectives. A total of 243 state-

used to explore diversity of viewpoints within potentially hetero-

ments written and released between January 2009 and June 2017

geneous stakeholder groups. In this context, Q‐methodology might

were selected and constituted the original concourse. The con-

help clarify the views of individual stakeholders within the shoot-

course was considered complete when the addition of new state-

ing community, that is, ammunition users, who are instrumental to

ments did not present any new opinions (Cairns, 2012).

�4

|

NEWTH ET al.

People and Nature

2.2 | Constructing the Q‐set

The concourse was refined to a manageable number of statements

to each other. This was to reduce undue social influence within

the sample, thus improving the likelihood that a diversity of views

could be captured.

(termed the Q‐set; Table 1) so that they could be sorted by the participants in the Q‐sort stage. An unstructured strategic sampling approach was followed to ensure that the variability of the concourse

was captured by the Q‐set (Webler et al., 2009). Each statement was

2.3.1 | Administering the Q‐sort

Q‐sorts were undertaken by each participant individually be-

printed onto a card in a common format and read in detail several

tween August 2017 and February 2018. Participants were asked

times by the members of the research team who were familiar with

to rank the 56 Q‐statements according to how strongly they

the topic (though none had participated in the interviews to construct

agreed or disagreed with each (Brown, 1996). To facilitate this

the concourse). Group discussions explored possible meanings of each

process, participants were given a deck of randomly numbered

statement. The statements were assigned to clearly define themes

cards (with each card containing one statement from the Q‐set),

and subthemes that emerged inductively from the concourse. The

instructed to read all 56 statements and sort them first into three

categories provided a means of grouping statements that had broad

categories; Agree, Disagree and Neutral/Unsure/Not applicable

similarities (Webler et al., 2009). When no new themes emerged, it was

(Cotton, 2015). The status of statements could be changed dur-

surmised that major themes had been identified (Thomas, 2003). The

ing subsequent sorting if desired. Statements were then sorted

statements were further reduced following Fisher's experimental de-

along a scale from 5 (agree most strongly) to −5 (disagree most

sign principles (Brown, 1980), whereby similar statements within each

strongly), where 0 is neutral (statements have zero salience),

theme were eliminated to avoid repetition. The final Q‐set constituted

and with a fixed number of statements along the scale (Watts

56 statements and was created by selecting a number of statements

& Stenner, 2012). A pyramid‐shaped grid, known as an array, is

from each theme and subtheme in order to encompass the spectrum

used as it requires respondents to rank the statements in a forced

of aspects discussed in the debate. A range of views within each theme

quasi‐normal distribution (Curry et al., 2013; Figure S1). This en-

was maintained (Cotton, 2015; Stainton Rogers, 1995). In order to

courages the participants to evaluate each statement carefully

minimise reflexivity (i.e. researcher interference) in the study design

and helps them to reveal their preferences (Webler et al., 2009).

(Webler et al., 2009), verbatim statements were included where possi-

Participants in the Q‐sort were encouraged to interpret the

ble with minimal editing and paraphrasing of the statements employed

statements in the context of others when sorting (Cairns, 2012;

only for the purposes of increasing clarity and brevity (Cotton, 2015;

Webler et al., 2009). Once the statements had been ranked,

Stainton Rogers, 1995). The final Q‐set was checked by eight informed

each participant was asked to identify the areas in the grid that

individuals from both the shooting and conservation communities in

demarcated agree from disagree and neutral. Following the Q‐

the UK (Cotton, 2015; Stainton Rogers, 1995). Finally, pilot testing with

sort, each participant was asked in an interview to elaborate on

five individuals helped refine the Q‐sort process and ensured that in-

how they had interpreted the most salient statements (those

structions were clear and well understood.

placed at both extreme ends of the continuum on the array),

their reasoning for ranking the statements in their unique way,

2.3 | Participant selection

and whether they felt that their perspective had been captured

within the Q‐set (Brown, 1980; Van Exel & de Graaff, 2005). The

Participants from the UK's shooting community were selected

interviews provided information which, along with the factor

through purposive sampling, instead of random sampling of a large

analysis, helped give the Q‐sorts meaning. The interviews were

number of participants. Q‐method aims to identify the compre-

recorded by Dictaphone and transcribed. A number of verbatim

hensive diversity of perspectives that exist, rather than to deter-

statements were extracted to qualitatively illustrate the various

mine how those perspectives are distributed across a population

perspectives within each identified factor. During the interview,

(Armatas, Venn, & Watson, 2017). Therefore, participants from the

participants engaged in a short discussion on whether they felt

shooting community were selected for their familiarity with the

that solutions were required to reduce the risks of people and

issue (Webler et al., 2009). Based on previous studies (Cromie et

wildlife ingesting lead ammunition and, if so, to propose sugges-

al., 2010) and discussions with those from the community, views

tions. Potential barriers to implementing change were also dis-

were deemed likely to vary according to how shooters predomi-

cussed. Those not believing that solutions were required were

nantly accessed their shooting, their primary target quarry species

asked to explain their reasoning. Participants also provided addi-

and their familiarity with non‐toxic shot (indicated by frequency

tional socio‐demographic information through the completion of

of use), albeit acknowledging that there is likely some overlap be-

a short questionnaire. Each participant gave their informed con-

tween categories. These additional criteria were therefore used

sent to participate before they were surveyed. The anonymity of

to identify participants within the shooting community (Table 2).

participants was protected and the study and its methodology

Although some participants were known to each other, efforts

were approved by the College of Life and Environmental Sciences

were made to incorporate individuals from a breadth of distinct

(Penryn) Ethics Committee at the University of Exeter (reference

and separate friendship groups, whose members were unknown

2016/1498).

�People and Nature

NEWTH ET al.

|

5

TA B L E 1 Factor arrays for the two study factors. Factor 1 represents the ‘Open to change’ perspective while Factor 2 represents Status

quo. A factor array (i.e. an estimate of the factor's viewpoint) was identified by combining a weighted average of all the individual Q‐sorts

that loaded significantly on a particular factor

Factor

Statement

1

2

1

Stakeholder opinions from all sides of the lead poisoning debate should be included in any decision‐making

process.

2

3

2

Lead shot is better than steel at killing and not wounding an animal.

0

5

3

Supermarkets should clearly state that their wild game meat products might contain lead.

2

0

4

Lead ammunition harms the image of shooting.

1

−3

5

Steel shot is more likely to ricochet from hard surfaces than lead.

2

4

6

The phasing out of lead shot will lead to the demise of shooting.

−5

1

7

The financial impacts of any further restrictions on lead could be very damaging to shooting‐related

interests.

−3

0

8

Lead ammunition is not a major source of lead poisoning in wild birds.

−3

1

9

There is no evidence that lead poisoning causes bird populations to decline.

−3

1

10

Current game meat handling techniques are enough to address any risks to humans from lead shot.

−1

2

11

Shooters' pastimes and activities are being eroded.

−4

2

12

If shooters saw birds dying from lead poisoning, they would think twice about using lead ammunition.

4

0

13

The scientific evidence of the impacts of lead on waterbirds is robust.

1

−2

14

The shooting community probably does more for wildlife and habitats than any other group in the UK.

0

5

15

A large number of wildfowl die from lead poisoning each year.

0

−3

16

The risks to wild birds from lead ammunition have been exaggerated.

17

Lead is a toxic substance.

−3

3

5

3

18

Those with political power to influence the issue are biased in favour of keeping lead shot.

−1

−4

19

20

Lead poisoning is a major welfare problem for wild birds.

0

−4

Shooters and non‐shooters have the same aim of having sustainable numbers of birds in the British

countryside.

3

4

21

Steel shot damages shotgun barrels.

−1

1

22

There needs to be greater awareness within the shooting community about the harm lead poisoning does.

4

0

23

To be taken seriously, information about lead poisoning needs to come from within the shooting

community.

1

1

24

There should be better enforcement of current regulations restricting the use of lead shot.

1

−2

25

Opposition to lead ammunition is driven more by a dislike of shooting than any evidence of harm.

−2

4

26

If use of non‐toxic ammunition makes people more aware of good range judgement, then they will shoot

better.

−1

−3

27

Steel and lead shot are comparably priced.

−1

−2

28

More research should be done on the performance of non‐toxic ammunition.

0

3

29

Eating game killed by lead ammunition has adverse effects on human health.

−2

−5

30

The most effective solution to reduce the risks of lead would be to replace lead shot with non‐toxic

alternatives.

2

−1

31

There are no safe levels of lead exposure.

1

−2

32

More guidance on different ammunition types, and techniques for their use, would reduce concerns about

non‐toxic shot.

2

0

33

Those selling game meat for human consumption are not very aware of possible lead contamination in their

meat.

−1

−4

34

There is clearly a need for solutions to reduce the risks of lead poisoning.

3

0

35

The risks to human health from lead ammunition have been exaggerated.

−2

3

36

There should be better observance of current regulations restricting the use of lead shot.

4

−2

(Continues)

�6

|

NEWTH ET al.

People and Nature

TA B L E 1

(Continued)

Factor

1

Statement

2

37

Current restrictions on using lead shot in England and Wales are not sufficient to address lead poisoning in

waterbirds.

38

If you have to shoot at shorter ranges it's not as sporting or fun.

−4

−1

39

Shooting at closer range with non‐toxic shot damages the meat.

−2

−1

1

0

40

Using plastic wads with non‐toxic shot can cause problems with livestock.

0

2

41

Non‐toxic shot is widely available.

3

2

42

The shooting community and cartridge manufacturers need to work together and come up with a viable

alternative to lead shot.

0

4

43

Ballistically, alternatives to lead shot that are fit for purpose already exist.

44

Current human health advice is enough to reduce the risks of lead shot to humans.

45

Sooner or later, lead shot will be banned.

46

Using non‐toxic shot would have a negative financial impact on me.

47

Non‐toxic shot is ineffective against clay targets.

−5

−3

48

Regulations are essential to reducing lead poisoning in waterbirds.

3

−3

3

−1

−1

2

0

−2

−2

1

49

Lead poisoning in birds is not a big enough problem to justify current regulations.

−4

1

50

Accumulated spent lead shot in intensively shot locations should be removed from the soil to reduce environmental contamination.

−2

−4

51

Shooting organisations are afraid they will look weak if they support a ban on lead shot.

1

−1

52

I am happy to use non‐lead ammunition.

4

−1

53

A wider range of non‐toxic cartridges would become available if there was a ban on lead.

2

−1

54

Some 'non‐toxic' alternatives to lead have greater toxicity than lead.

−3

0

55

Robust scientific evidence should determine how we use lead shot.

56

If we stopped using lead shot we'd have more birds to shoot.

5

2

−4

−5

Note: Statement numbers from the Q‐set are presented in brackets followed by their corresponding factor array score which relates to a scale of

agreement (e.g. −5 = most disagree; 0 = neutral; +5 = most agree). For example, (17, +5) indicates that statement 17 is strongly agreed with.

Rule; Brown, 1980); and (c) there were two or more significant factor

2.4 | Statistical analysis

loadings following extraction (Brown, 1980; Table S1). Factor loadings

The 30 Q‐sorts were analysed using centroid factor analysis and

(i.e. the extent to which an individual Q‐sort exemplifies the pattern

subjected to a Varimax rotation in PQMethod (Schmolck, 2014). An

for a defined factor) were regarded as significant when ≥±0.34 at the

unrotated factor was considered significant when: (a) its Eigenvalue

p < 0.01 level (Brown, 1980) (Table S1), where:

exceeded one (Kaiser–Guttman criteria: Guttman, 1954; Kaiser, 1960,

1970); (b) the cross product of its two highest loadings exceeded twice

the standard error of the correlation matrix (i.e. >±0.27, Humphrey's

√

Significant factor loading = 2.58 × (1∕ number of items in Q-set)

TA B L E 2 Summary of the characteristics of survey participants. Based on previous studies (Cromie et al., 2010) and discussions with

those from the community, it was hypothesized that viewpoints were likely to vary according to how shooters predominantly accessed their

shooting, their primary target quarry species and their familiarity with non‐toxic shot (indicated by frequency of use), albeit acknowledging

that there is likely some overlap between categories

Characteristics

Response (number of respondents)

Use of non‐toxic shot

Very frequently/frequently (14), occasionally (11), rarely/very rarely (3), never (1), unknown (1)

Main quarry species

Wildfowl (10), terrestrial (13), mixed (5), deer (1), unknown (1)

Main access to shooting

Syndicate/club (11), local contacts (9), shoots alone (1), employment (2), mixed methods, including commercial (3), mixed methods, excluding commercial (2), unknown (2)

Age

25–34 (3), 35–44 (6), 45–55 (6), 55–64 (9), 65+ (5), Unknown (1)

Gender

Male (30), female (0)

Occupation

Business/industry/construction (9), farming/land management (4), conservationist/researcher (4), game

management (4), cartridge supplier (1), rural commentator/journalist (2), retired (6)

�People and Nature

NEWTH ET al.

|

7

Factors selected using these criteria (Table S1) were then rotated

drawing distinctions between them (Stenner, Cooper, & Skevington,

(Schmolck, 2014). Q‐sorts that load significantly on the same fac-

2003). In order to minimise researcher bias that may arise during

tor (e.g. see Table 3) show a similar sorting pattern suggesting simi-

the interpretation process, a protocol (known as a ‘crib sheet’) for

lar and/or shared viewpoints among participants (Watts & Stenner,

analysing factor arrays developed by Watts and Stenner (2012) was

2012). A single, typical Q‐sort (termed a factor array) was created for

systematically and rigorously followed for each array. This ensured

each rotated factor by combining a weighted mean of all the signifi-

that a methodical approach to factor interpretation was applied con-

cantly loading Q‐sorts (Brown, 1980; Watts & Stenner, 2012; Table

sistently in the context of each factor and helped to deliver genuinely

3; Figure S1). Interpretations of the factor arrays were made by ho-

holistic factor interpretations by forcing engagement with every

listically examining the way items were patterned within each and by

statement in the factor arrays (Watts & Stenner, 2012). A ‘reflexive’

approach (Galdas, 2017) was also adopted which ensured critical

TA B L E 3 The rotated factor matrix. The loadings indicate the

extent to which each Q‐sort is associated with each of the study

factors following rotation

Sort number

1

self‐reflection about preconceptions, relationship dynamics and the

analytical focus, throughout the process. For this, the lead researcher

made use of observation and reflection to repeatedly examine these

Factor 1

Factor 2

0.6684

−0.4248

aspects, processing through an ongoing internal dialogue and also

in discussion with colleagues that were further removed from the

subject (Attia & Edge, 2017).

2

0.2244

0.7025

3

0.5362a

0.2377

4

0.0096

0.8426a

5

a

0.6077

0.1417

6

0.4084a

−0.0330

7

0.5248a

−0.0383

8

0.4316a

0.2421

9

0.5574a

0.2656

10

0.6947a

0.2477

vided in Table 2. Two factors were extracted (Table 3) and ac-

0.7495a

cording to the following selection criteria, represented the

−0.0755

most plausible summary of the Q‐sorts (Watts & Stenner, 2012)

0.6006a

(Table S1): Eigenvalues exceeded 1.0 (Kaiser–Guttman criteria:

0.1362

Guttman, 1954; Kaiser, 1960, 1970), the cross product of each

0.0074

factor's two highest loadings exceeded twice the standard error

11

−0.1989

a

3 | R E S U LT S

A total of 36 people were approached; 30 (83.3%) actually

participated (two individuals declined, two initially agreed to

participate but later withdrew and two did not respond to the

invitation). Detail of the composition of the participants is pro-

12

0.6766a

13

0.0146

14

0.6967

15

0.7434

16

0.0532

0.5185a

17

0.0065

0.6312

18

0.3381a

0.1736

19

0.2259

0.7108a

20

0.6856a

−0.0933

21

0.3842a

0.3290

40% or above; Kline, 1994; Watts & Stenner, 2012). In total, 28 of

22

0.2094

0.5258a

the 30 Q‐sorts significantly loaded onto one of the two factors

23

−0.0807

0.7516a

and two sorts were confounded as they loaded significantly onto

24

0.2837

0.6375a

both factors. Here, we aim to understand and explain the per-

25

−0.1903

0.7204a

spective exemplified by each factor and shared by participants

a

a

a

of the correlation matrix (i.e. >±0.27, Humphrey's Rule; Brown,

1980), and there were two or more significant factor loadings

(i.e. ≥±0.34) following extraction (Brown, 1980). Together both

factors accounted for 43% of the rotated explained variance

(Table 3) which falls at the lower end of the range of explained

variance that would ordinarily be considered acceptable (35%–

26

0.5973a

0.0711

whose sorts have significantly aligned with them. Statement

27

0.6639

a

−0.0979

numbers from the Q‐set are presented in brackets followed by

28

0.6313

a

−0.2830

their corresponding factor array score. For example, (17, +5) indi-

29

0.5579

a

0.1875

30

0.4762

% explained variance

Eigenvalue

0.4972

22.7

20.2

6.8

6.1

*Indicates which factor each Q‐sort is significantly loaded on (i.e.

≥±0.34 at p < 0.01). For example, sorts 3 and 5 significantly load on to

Factor 1 and contribute to the weighted average derived from the array

which exemplifies Factor 1 (Table 1; Figure S1). Q‐sorts 1 and 30 are

confounded, that is, they significantly load on to both factors.

cates strong agreement with statement 17 (see Table 1 for array

scores associated with each statement and factor). Pertinent

comments made by participants during the post‐sort interviews

are also used to support interpretation.

3.1 | Factor 1: Open to change

Résumé: This group of ammunition users believed that lead is toxic; re‐

futed the view that lead ammunition is not a major source of poisoning

�8

|

NEWTH ET al.

People and Nature

in wild birds; believed that solutions are needed, and the phasing out of

to develop a viable alternative to lead shot (42, 0). Using non‐toxic

lead shot will not lead to the demise of shooting. They are content to use

shot was not believed to have a negative financial impact on the

non‐lead ammunition.

individual (46, −2). There was neither agreement nor disagreement

Factor 1 has an Eigenvalue of 6.8 and explains 22.7% of the study

with the notion that lead shot is better than steel at killing and

variance. A total of 17 participants significantly loaded on this factor.

not wounding an animal (2, 0). There was some disagreement that

current human health advice is sufficient to reduce the risks of

lead shot to humans (44, −1) and that current game meat handling

3.1.1 | Evidence and impacts

techniques are enough to address any risks to humans from lead

I think we're all aware that lead is a toxic substance.

shot (10, −1).

It's been taken out of petrol, it's been taken out of

pencils. And now, in certain circumstances, it's been

taken out of shotgun ammunition

(Participant 5)

3.1.3 | Cultural and sporting aspects

I don't see any reason why the phasing out of lead

This perspective was characterised by a strong belief that lead is

shot will lead to the demise of shooting… Indeed,

toxic (17, +5) and some agreement that there are no safe levels of lead

in some senses, if we lost lead shot, or gave up lead

exposure (31, +1). It refutes the views that lead ammunition is not a

shot, we might be in a stronger position to promote

major source of poisoning in wild birds (8, −3) and that it has no impact

what we do, because it is such a controversial issue

on bird populations (9, −3). Scientific evidence of the impacts of lead on

(Participant 14)

waterbirds was perceived to be robust (13, +1). This position did not believe that the risks to wild birds from lead ammunition have been exag-

This position strongly disagreed with the view that shoot-

gerated (16, −3) nor that opposition to lead ammunition is driven more

ers' pastimes and activities are being eroded (11, −4). There

by a dislike of shooting than any evidence of harm (25, −2). Eating game

was strong disagreement that shooting at shorter ranges is not

killed by lead ammunition was not thought to have adverse effects on

as sporting or fun (38, −4). The financial impact of any further

human health (29, −2). However, the risks to human health from lead

restrictions on lead was not perceived to be very damaging to

ammunition were not perceived to have been exaggerated (35, −2).

shooting‐related interests (7, −3). This perspective adhered to the

view that shooting organisations are afraid they will look weak if

they support a ban (51, +1). There was strong disagreement that

3.1.2 | Solutions

the phasing out of lead shot would lead to the demise of shooting

I am very happy to use non‐lead ammunition. It's not

(6, −5), and there was uncertainty that lead shot will be banned in

an opinion; I use it, it works, and therefore I'm in com-

the future (45, 0).

plete agreement with it

(Participant 12)

This viewpoint recognised the need for solutions to reduce the

3.2 | Factor 2: Status quo

risks of lead poisoning (34, +3). It strongly agreed that if shooters saw

Résumé: This group of ammunition users believed that lead is toxic but

birds dying from lead poisoning, they would think twice about using

did not regard lead poisoning a major welfare problem for wild birds; op‐

lead ammunition (12, +4), and that there was a need for greater aware-

position to lead ammunition is driven more by a dislike of shooting than

ness within the shooting community about the harm lead poisoning

evidence of any real harm; there is ambivalence about the need for solu‐

does (22, +4). There was also strong support for better observance

tions and they are unhappy with the non‐toxic alternatives.

of current regulations restricting the use of lead shot (36, +4) and the

need for robust scientific evidence to determine how lead shot is used

Factor 2 has an Eigenvalue of 6.1 and explains 20.2% of the study

variance. In total, 11 participants significantly loaded on this factor.

(55, +5). This view strongly disagreed that lead poisoning in birds is not

a big enough problem to justify current regulations (49, −4).

Regulations were seen as essential for reducing lead poisoning

3.2.1 | Evidence and impacts

in waterbirds (48, +3). This position supported the replacement of

If it was right what they're saying, why are

lead shot with non‐toxic alternatives as the most effective solution

there not people picking up birds all across the

for reducing the risks of lead (30, +2). There was strong agreement

countryside?

with the statement ‘I am happy to use non‐lead ammunition’ (52,

+4) and agreement that guidance on different ammunition types,

In the shooting world we're up against so much oppo-

and techniques for their use, would reduce concerns about non‐

sition. A lot of people just don't like what we do, they

toxic shot (32, +2). According to this view, alternatives to lead shot

don't like shooting…

(Participant 25)

that are fit for purpose (in ballistic terms) already exist (43, +3).

Therefore, there was ambivalence about whether the shooting

This perspective agreed that lead is a toxic substance (17, +3)

community and cartridge manufacturers need to work together

but disagreed that there are no safe levels of lead exposure (31, −2).

�People and Nature

NEWTH ET al.

Lead ammunition was not perceived to be a major source of lead

|

9

shot locations should be removed from the soil (50, −4). There was

poisoning in wild birds (8, +1) and lead poisoning was not regarded

strong disagreement that those selling game meat for human con-

as a major welfare problem for wild birds (19, −4). The scientific

sumption are not very aware of possible lead contamination in their

evidence of the impacts of lead on waterbirds was not believed to

meat (33, −4) and there was satisfaction that current human health

be robust (13, −2) and the risks to wild birds from lead ammunition

advice is sufficient to reduce risks of lead shot to humans (44, +2).

were thought to have been exaggerated (16, +3). It was strongly

Current game handling techniques were deemed to be sufficient to

agreed that opposition to lead ammunition is driven more by a dis-

address any risks to humans from lead shot (10, +2).

like of shooting than any evidence of harm (25, +4). There was

strong disagreement that eating game killed by lead ammunition

has adverse effects on human health (29, −5). Furthermore, the

3.2.3 | Cultural and sporting aspects

risks to human health from lead ammunition were perceived to

So they [the gamekeepers] are managing the habi-

have been exaggerated (35, +3).

tats so they are not only beneficial to the pheasants

but also all the other wildlife that's there as well

(Participant 4)

3.2.2 | Solutions

It's been overlooked, the fact that lead is the cleanest

killing ammunition out there

(Participant 25)

This position strongly adhered to the view that the shooting community probably does more for wildlife and habitats than any other

group (14, +5). There was agreement with the notion that shooters'

There was ambivalence about the need for solutions to reduce

pastimes and activities are being eroded (11, +2) and that the phasing

the risks of lead poisoning (34, 0) although agreement that robust

out of lead shot will lead to the demise of shooting (6, +1). There was

scientific evidence should determine how lead shot is used (55, +2).

uncertainty about whether the financial impacts of any further restric-

This view did not agree that there should be better observance of

tions on lead could be very damaging to shooting‐related interests (7,

the current regulations restricting the use of lead shot (36, −2). There

0). There was strong disagreement that those with political power are

was some agreement that lead poisoning in birds is not a big enough

biased in favour of keeping lead shot (18, −4). This view did not believe

problem to justify current regulations (49, +1). Regulations were not

that lead shot will be banned in the future (45, −2).

deemed essential for reducing lead poisoning in waterbirds (48, −3).

This position disagreed with the suggestion that the most effective

solution to reduce the risks from lead would be to replace lead shot

3.3 | Consensus among perspectives

with non‐toxic alternatives (30, −1). There was some disagreement

Well, if you've got to have a discussion, you need to

with the statement ‘I am happy to use non‐lead ammunition’ (52,

have the people who are against it and the people

−1) suitable alternatives to lead shot already exist (43, −1). It was

who are for it, so you can have a balanced debate

strongly agreed that lead shot is better than steel at killing and not

(Participant 25)

wounding an animal (2, +5) and that steel is more likely to ricochet

from hard surfaces than lead (5, +4). There was strong support for

There were five statements of statistically significant consensus

the shooting community and cartridge manufacturers working to-

across both factors (Table 4). Both parties indicated that lead poisoning

gether to develop a viable alternative to lead shot (42, +4). This view

was a shared problem; the involvement of stakeholders from all sides

strongly disagreed that accumulated spent lead shot in intensively

of the debate was desirable and there was consensus that to be taken

TA B L E 4 Statements with statistically significant consensus across both factors. These are items whose rankings do not distinguish

between factors, that is, the study factors have ranked these statements in the same or similar ways (where p > 0.05). Both the Q‐sort

value and normalised factor scores (the z scores) are shown. It should be noted that the authors noticed some difficulty with participants'

interpretation of statement 56. It was clear in the follow‐up interviews that some took this statement to refer to lead's impacts on wild bird

populations while others linked it with reared game bird populations. There is therefore likely some ambiguity with the interpretation of this

statement in this analysis

Statement

1

Stakeholder opinions from all sides of the lead poisoning

debate should be included in any decision‐making process

21

23

Factor 1

Rank (z score)

Factor 2

Rank (z score)

Differential

z score

2 (0.820)

3 (0.968)

−0.148

Steel shot damages shotgun barrels

−1 (0.022)

+1 (0.156)

−0.134

To be taken seriously, information about lead poisoning

needs to come from within the shooting community

+1 (0.423)

+1 (0.212)

0.211

41

Non‐toxic shot is widely available

+3 (0.830)

+2 (0.573)

0.257

56

If we stopped using lead shot we'd have more birds to shoot

−4 (−1.828)

−5 (−2.084)

0.256

�10

|

NEWTH ET al.

People and Nature

seriously by shooters information about lead poisoning should come

policy issues in three main ways: (a) Clarifying perspectives; (b)

from the shooting community. It was agreed that some challenges as-

Identifying competing problem definitions and solutions; and (c)

sociated with the non‐toxic alternatives (steel shot damages shotgun

Forging new solutions. Here, we discuss the contribution of this

barrels) remain, though the alternatives were believed to be widely

study to each of these, summarising and exploring the links between

available. Key statement positions that define the two factors and con-

each perspective's definition of the problem and preferred solutions

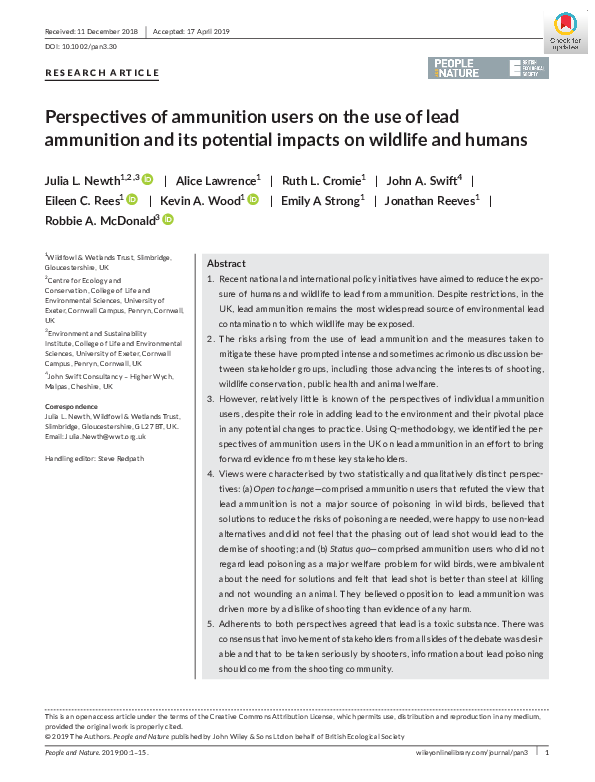

sensus statements are illustrated in Figure 1.

(Derry, 1984; Weiss, 1989).

4 | D I S CU S S I O N

4.1 | Clarifying perspectives

The views of individual ammunition users in the UK about the ‘lead

The risks of lead ammunition use to human and wildlife health and

debate’ were characterised by two statistically and qualitatively

the measures taken to mitigate these have long been debated in

distinct perspectives: (a) ‘Open to change’—those that refuted the

the UK, culminating in a current conflict primarily enacted between

view that lead ammunition is not a major source of poisoning in

groups representing shooting and conservation interests (Cromie et

wild birds, believed that solutions to reduce the risks of poisoning

al., 2015; Newth et al., 2015). While this conflict between groups is

are needed, were happy to use non‐lead alternatives and did not

well known, we have explored the diversity of perspectives among

feel that the phasing out of lead shot would lead to the demise of

ammunition users, the critical group for their role in releasing lead

shooting; and (b) Status quo—those who did not regard lead poi-

into the environment and adopting any related changes to shooting

soning as a major welfare problem for wild birds, were ambivalent

practice. Durning (2005) proposed that Q‐methodology can be de-

about the need for solutions and felt that lead shot is better than

ployed to help resolve conflicts and forge solutions for contentious

steel at killing and not wounding an animal. Opposition to lead

F I G U R E 1 A Venn diagram depicting views on some key statements that define two subject positions derived from a Q‐method study

of ammunition users. Topics of consensus between the two positions are highlighted in the centre. For each perspective, statements were

allocated to three themes that emerged inductively from the Q‐set: the problem, the solution and the wider context. Taking a holistic

approach advocated by Q‐method (Watts & Stenner, 2012), statements that reflected a breadth of factor scores, from −5 to +5, within

each factor array were extracted, and statements related to topics regarded by the authors as most prevalent within the ‘lead debate’ were

prioritised for inclusion. Statements with statistically significant consensus across both factors (see Table 4) were included in the ‘Consensus’

section. For brevity and illustrative purposes, these statements were summarised and included in this Venn diagram. This figure therefore

represents a ‘snap‐shot’ of each perspective rather than a comprehensive view

�People and Nature

NEWTH ET al.

|

11

ammunition was driven more by a dislike of shooting than evi-

Although both perspectives agreed that lead is toxic, the extent of its

dence of any harm. To understand fully the complexity and nature

toxicity was disputed: ‘Open to change’ believed that lead is a genuine

of perspectives, they should be placed within their wider socio‐

problem and there are no safe levels of lead, whereas Status quo be-

economic and cultural contexts. Both therefore are discussed

lieved that the lead problem is exaggerated and safe levels exist. Such

within the context of views about the future of shooting in the

contrasting definitions of the ‘lead problem’ was manifested in differ-

British landscape.

ing views on its impacts and the need for (and preferred) solutions.

The two perspectives had contrasting views about the future

For ‘Open to change’, the scientific evidence on the impacts of

of shooting. The Status quo perspective was framed by fears that

lead on waterbirds was believed to be sound and the evidence was

the phasing out of lead shot would lead to the demise of shooting

trusted (i.e. not considered exaggerated nor influenced by a wider

and that shooters' pastimes and activities were being eroded. These

dislike of shooting sports). Conversely, those aligned to Status quo’

fears were compounded by the feeling that opposition to lead shot is

were less inclined to believe the evidence, which was not regarded

driven by a dislike of shooting. This perspective reflects a prevailing

as robust and was perceived to have been exaggerated. This distrust

message in the printed shooting media in recent years, which has

of the evidence is again likely compounded by the strong sense that

suggested that a ban on lead shot represents ‘the thin end of the

opposition to lead ammunition is driven more by a dislike of shoot-

wedge’ with a call for all attacks on shooting to be resisted (Cromie

ing than evidence of harm. Mistrust of scientists often stems from

et al., 2015). Such concerns were also reflected in comments made

a questioning of their motives rather than their expertise or integ-

during the interviews and suggest that some may perceive their

rity (Wissenschaft im Dialog, 2017). Multiple factors may contribute

shooting heritage as a whole to be under threat, for example:

to distrust of science, including religious beliefs, level of education,

political affiliation and socio‐economic status (Kabat, 2017; Kahan,

People with political influence are using banning of

2002). Distrust is a key barrier to collaboration (Ansell & Gash, 2007)

lead shot in the hope therefore that people will give

and to the resolution of conservation conflicts (Young et al., 2016),

up shooting. So it's the sprat to catch the mackerel.

and therefore may have serious implications for conservation, the

The thin end of the wedge

success of which often relies on effective collaboration.

(Participant 13)

In the post‐sort interviews, several ammunition users linked

Moreover, this shooting heritage was believed to make an import-

their disbelief about the impacts of lead with their own personal

ant contribution to the conservation of British wildlife. This sense

experiences, notably that they had never knowingly encountered a

of pride in the ‘shooting life’ was a strong theme in the post‐sort

lead poisoned bird nor had been aware of any impacts on their own

interviews:

health following a lifetime of eating game:

The shooting community wants the wildlife to suc-

But here I am, I've been eating game for, I don't know,

ceed…My grandfather was a tenant farmer, he told

72 years, and I'm still here. So it's ineffective on me

me that you're only here for a short period and you're

(Participant 19)

only the steward of the land in your lifetime, and you

have an obligation to leave it looking better than you

found it

(Participant 13)

Neither perspective believed that lead shot was harmful to human

health. Mortality of wild birds from lead poisoning often goes undetected (Cromie et al., 2010; Newth et al., 2013). Unlike wildlife diseases

Conversely, ‘Open to change’ disagreed that shooters' pastimes

such as botulism, large‐scale die‐offs of wild birds from lead poisoning

and activities were being eroded and that the phasing out of lead shot

are rare events (Pain, 1991). Furthermore, sublethal impacts of lead

would lead to the demise of shooting:

on the physiological systems of birds (Franson & Pain, 2011; Newth et

al., 2016) and humans (Arnemo et al., 2016; EFSA, 2010) may not be

I don't agree that the phasing out of lead shot would

obvious (Cromie et al., 2015).

lead to the complete demise of shooting. I think the

It should also be considered that when conservation issues

phasing out of lead shot will have short‐term impacts

are politicised, individuals may selectively understand the science

on shooting

in accordance with their own value‐based demands (Chamberlain,

(Participant 12)

Rutherford, & Gibeau, 2012; Kahan, Jenkins‐Smith, & Braman, 2011;

Sarewitz, 2004) and this may partly explain the polarity in view-

4.2 | Identifying competing definitions of the

lead problem

Problem definition provides the foundations for the construction of

points in this study.

4.3 | Preferred solutions

policy and its implementation, as well as influencing which stakehold-

Status quo was ambivalent about the need for a solution to reduce

ers take part in the decision‐making process (Weiss, 1989). We found

the risks of lead shot, perhaps unsurprisingly given the view within

contrasting definitions of the problem among ammunition users.

this group that lead poisoning is not a significant problem. A previous

�12

|

NEWTH ET al.

People and Nature

survey of British shooters found that a key reason for non‐compliance with the current lead shot restrictions was that ‘lead poisoning is

4.3.1 | Commonalities

not a sufficient problem to warrant restrictions’ (Cromie et al., 2010).

Although the two perspectives differed on many issues, there was

There was also support for this sentiment within Status quo, associ-

consensus that to be taken seriously information about lead poison-

ated with little enthusiasm for suggested solutions such as awareness

ing should come from within the shooting community:

raising, better observance or enforcement of the current regulations

and further regulations to replace lead shot with non‐toxic alterna-

Yes. If you want to hear bad news, you want to hear it

tives. In contrast, as well as agreeing that lead was a significant prob-

in the pub, from your mates, rather than in the media,

lem, ‘Open to change’ recognised the need for solutions to reduce the

at a press conference directed at you. You want to

risks of lead poisoning. Regulations were seen as essential and there

be in the room, and you want to be in ownership

was some support for the replacement of lead shot with non‐toxic al-

of leading the way out of what the issue might be

ternatives. This view strongly agreed that shooters would think twice

(Participant 22)

about using lead ammunition if they saw birds dying from poisoning

and that greater awareness of the issue would help:

This indicates that such sources would have greater credibility

among shooters. In Denmark, critical advocates within the hunting

I just can't imagine that anybody, whether they were

community persuaded other hunters of the benefits of non‐toxic

shooters or not, would think that it's acceptable to

ammunition using evidence from hunter‐led research (Kanstrup,

see birds being poisoned or dying. If they saw it, I

2019; Newth et al., 2015). In principle, both perspectives supported

think it would upset them

using robust scientific evidence to guide lead shot policy and man-

(Participant 10)

agement and agreed that opinions from all sides of the ‘lead debate’

In recent years, the ‘lead debate’ has been punctuated by numer-

should be included in the decision‐making process. Effective par-

ous national laws (HMSO, 1999, 2002a, 2002b, 2003, 2004, 2009)

ticipation may improve relationships by increasing trust and sharing

and international agreements (IUCN, 2016; Kanstrup et al., 2018;

perspectives and ultimately reduce conflicts (Ansell & Gash, 2007;

UNEA, 2017; UNEP‐CMS, 2014, 2017) which have called, to varying

Redpath et al., 2013). Both perspectives believed that shooters and

degrees, for the replacement of lead ammunition with non‐toxic al-

non‐shooters have the same aim of having sustainable numbers of

ternatives. Views on non‐lead alternatives notably differed between

birds in the British countryside:

the two perspectives. Those in ‘Open to change’ were more likely to

be happy to use non‐lead options, felt that they were fit for purpose

I feel as though my view would be the same as a non‐

and therefore saw little need for further research to develop a viable

shooter. We want to see the same thing, we don't

alternative. They believed that the availability of further information

want to see the decline in wildlife at all. We'd rather

on non‐lead ammunition would reduce concerns. A previous survey

see the uprising of it

(Participant 17)

found that 41% of British shooters felt that more guidance about the

non‐lead options would help improve compliance with current restrictions (Cromie et al., 2010). However, those in Status quo were generally

not happy to use non‐lead ammunition, did not feel that the alterna-

4.3.2 | Forging solutions

tives were fit for purpose and strongly believed that lead shot was

Conflicts are often oversimplified as they become entrenched and

better than steel at killing and not wounding an animal. A dislike of the

polarised, losing the nuanced perspectives that may exist among

alternatives was also a key reason that British shooters gave for not

the parties. Furthermore, individuals within a polarised stake-

complying with the current regulations in England (Cromie et al., 2010)

holder group do not necessarily hold uniform opinions on wild-

and concerns about the effectiveness of non‐lead shot relative to lead

life management (Chamberlain et al., 2012; Rust, 2017). Here, use

have been reported in shooting communities elsewhere (Kanstrup,

of Q‐method has allowed access to a complex issue, enabling the

2006, 2015, 2019). There was a strong belief among those in Status

perspectives of ammunition users, as the key group of actors, to

quo that more research should be done to develop a viable alternative.

be clarified, competing definitions of the problem and preferred

It seems logical that those who were more content with the non‐lead

solutions to be identified and commonalities to be revealed.

alternatives, reflecting the perspective of ‘Open to change,’ are more

Critically, these perspectives arise solely from within the shooting

likely to support the replacement of lead shot with these alternatives

community of ammunition users. In a conflict commonly depicted

while those who were not, are less likely to support this suggested

as between those in favour of shooting versus those opposed, we

solution. There was some support from those within ‘Open to change’

reveal that a diversity of views on lead ammunition are held within

for the notion that shooting organisations are afraid they will look

the shooting community itself. Further studies are required to as-

weak if they support a ban on lead shot. This may reflect the pressure

sess the prevalence of the views identified. The variables influenc-

that membership‐oriented shooting organisations are under to pro-

ing the views outlined within this paper merit further examination

vide both leadership and to reflect their memberships' views and sup-

using interdisciplinary methods from the social sciences and psy-

porting a ban may feed into a narrative of giving in to the opposition.

chology. A deeper understanding of factors predicting the use of

�People and Nature

NEWTH ET al.

lead and non‐lead ammunition would be beneficial for addressing

non‐compliance with the current regulations and acceptability of

any future changes to practice. Given that the lead debate is dynamic and influenced by various socio‐economic and political factors (Cromie et al., 2015), this study may form a useful foundation

for a longitudinal study whereby changes in perspectives on the

issue across time can be explored.

The views of women shooting participants were not captured

within this study as women were not specifically targeted during

participant recruitment. Studies have shown that women exhibit

relatively stronger environmental concern and behaviour than men

(Vincente‐Molina, Fernández‐Sáinz, & Izagirre‐Olaizola, 2018), and

therefore targeted work to assess the perspectives of women in relation to the lead shot issue merits further examination. Overall, the

clarification of views held by ammunition users presents an opportunity for the shooting community to take forward discussions and

potentially forge new solutions.

AC K N OW L E D G E M E N T S

We are extremely grateful to all participants and advisors from the

shooting community for their trust, time and contribution to this

study.

C O N FL I C T O F I N T E R E S T

There are no conflicts of interest associated with this work.

AU T H O R S ’ C O N T R I B U T I O N S

J.L.N. conceived the idea, J.L.N., R.A.M., A.L., R.L.C. and J.A.S. designed the methodology; J.L.N. collected the data; J.L.N. and E.S.

prepared the data for analysis; J.L.N. analysed the data; J.L.N. led

the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to

the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

DATA ACC E S S I B I L I T Y

All data supporting the results in this paper are available

from Zenodo (digital repository): https ://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2653514 (Newth et al., 2019).

ORCID

Julia L. Newth

https://orcid.org/0000‐0003‐3744‐1443

Eileen C. Rees

https://orcid.org/0000‐0002‐2247‐3269

Kevin A. Wood

https://orcid.org/0000‐0001‐9170‐6129

Robbie A. McDonald

https://orcid.org/0000‐0002‐6922‐3195

|

13

REFERENCES

Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2007). Collaborative Governance in theory and

practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18,

543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopar t/mum032

Armatas, C., Venn, T., & Watson, A. (2017). Understanding social‐ecological vulnerability with Q‐methodology: A case study of water‐based

ecosystem services in Wyoming, USA. Sustainability Science, 12, 105–

121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625‐016‐0369‐1

Arnemo, J. M., Andersen, O., Stokke, S., Thomas, V. G., Krone, O., Pain,

D. J., & Mateo, R. (2016). Health and environmental risks from lead‐

based ammunition: Science versus socio‐politics. EcoHealth, 13, 618–

622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393‐016‐1177‐x

Attia, M., & Edge, J. (2017). Be(com)ing a reflexive researcher: A developmental approach to research methodology. Open Review of

Educational Research, 4(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/23265

507.2017.1300068

Avery, D., & Watson, R. T. (2009). Regulation of lead‐based ammunition

around the world. In R. T. Watson, M. Fuller, M. Pokras & W. G. Hunt

(Eds.), Ingestion of lead from spent ammunition: Implications for wildlife

and humans (pp. 161–168). Boise, Idaho: The Peregrine Fund.

Bennett, N. J., Roth, R., Klain, S. C., Chan, K., Christie, P., Clark, D. A.,

… Wyborn, C. (2017). Conservation social science: Understanding

and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation.

Biological Conservation, 205, 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

biocon.2016.10.006

Bredin, Y. K., Lindhjem, H., Van Dijk, J., & Linnell, J. D. C. (2015).

Methodological and ideological options mapping value plurality towards ecosystem services in the case of Norwegian wildlife management: A Q analysis. Ecological Economics, 118, 198–206. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.07.005

Brown, S. R. (1980). Political subjectivity. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press.

Brown, S. R. (1996). Q methodology and qualitative research. Qualitative

Health Research, 6, 561–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732396

00600408

Byrd, K. (2002). Mirrors and metaphors: Contemporary narratives of the

wolf in Minnesota. Ethics, Place & Environment, 5, 50–65. https://doi.

org/10.1080/13668790220146456

Cairns, R. C. (2012). Understanding science in conservation: A Q method

approach on the Galapagos Islands. Conservation and Society, 10,

217–231. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972‐4923.101835

Chamberlain, E. C., Rutherford, M. B., & Gibeau, M. L. (2012). Human

perspectives and conservation of grizzly bears in Banff National

Park, Canada. Conservation Biology, 26, 420–431. https://doi.

org/10.1111/j.1523‐1739.2012.01856.x

Cotton, M. D. (2015). Stakeholder perspectives on shale gas fracking:

A Q‐method study on environmental discourses. Environment and

Planning, 47(9), 1944–1962. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15

597134

Cromie, R. L., Loram, A., Hurst, L., O’Brien, M., Newth, J., Brown, M. J.,

& Harradine, J. P. (2010). Compliance with the environmental protection (restrictions on use of lead shot)(England) Regulations 1999.

Report to Defra. Bristol.

Cromie, R., Newth, J., Reeves, J., Beckmann, K., O’Brien, M., & Brown,

M. (2015). The sociological and political aspects of reducing lead

poisoning from ammunition in the UK: Why the transition to non‐

toxic ammunition is so difficult. In R. J. Delahay & C. J. Spray (Eds.),

Proceedings of the Oxford lead symposium (pp. 104–124). Oxford, UK:

Edward Grey Institute, University of Oxford.

Cuppen, E., Breukers, S., Hisschemöller, M., & Bergsma, E. (2010). Q

methodology to select participants for a stakeholder dialogue on energy options from biomass in the Netherlands. Ecological Economics,

6, 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.09.005

�14

|

People and Nature

Curry, R., Barry, J., & McClenaghan, A. (2013). Northern Visions?

Applying Q methodology to understand stakeholder views on the

environmental and resource dimensions of sustainability. Journal of

Environmental Planning and Management, 56, 624–649. https://doi.

org/10.1080/09640568.2012.693453

Derry, D. (1984). Problem definition in policy analysis. Lawrence, KS:

University of Kansas Press.

Durning, D. (2005). Using Q‐methodology to resolve conflicts and find

solutions to contentious policy issues. Network of Asia‐Pacific Schools

and Institutes of Public Administration and Governance(NAPSIPAG)

Annual Conference 5–7 December 2005, Beijing, China.

EFSA. (2010). Scientific opinion on lead in food. EFSA Journal, 8, 1570.

https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1570

Franson, J. C., & Pain, D. J. (2011). Lead in birds. In W. N. Beyer & J. P.

Meador (Eds.), Environmental contaminants in biota. Interpreting tissue

concentrations (pp. 563–593). Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis.

Frantzi, S., Carter, N. T., & Lovett, J. C. (2009). Exploring discourses on

international environmental regime effectiveness with Q methodology: A case study of the Mediterranean Action Plan. Journal of

Environmental Management, 90, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

jenvman.2007.08.013

Galdas, P. (2017). Revisiting bias in qualitative research: Reflections

on its relationship with funding and impact. International Journal of

Qualitative Methods, 16, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094 06917

748992

Green, R. E., & Pain, D. J. (2015). Risk of health effects to humans in

the UK from ammunition‐derived lead. In R. J. Delahay & C. J. Spray

(Eds.), Proceedings of the Oxford lead symposium (pp. 27–43). Oxford,

UK: Edward Grey Institute, University of Oxford.

Guttman, L. (1954). Some necessary conditions for common‐factor analysis. Psychometrika, 19, 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF022

89162

Haas, P. (2004). When does power listen to truth? A constructivist approach to the policy process. Journal of European Public Policy, 11,

569–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176042000248034

HMSO (Her Majesty's Stationary Office). (1999). The environmental protection (restriction on use of lead shot) (England) Regulations 1999.

Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1999/2170/

contents/made

HMSO (Her Majesty's Stationary Office). (2002a). The environmental

protection (restriction on use of lead shot) (England) (Amendment)

Regulations 2002. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/

uksi/2002/2102/contents/made

HMSO (Her Majesty's Stationary Office). (2002b). The environmental

protection (restriction on use of lead shot) (Wales) Regulations 2002.

Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/wsi/2002/1730/

contents/made

HMSO (Her Majesty's Stationary Office). (2003). The environmental

protection (restriction on use of lead shot) (England) (Amendment)

Regulations 2003. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/

uksi/2003/2512/contents/made

HMSO (Her Majesty's Stationary Office). (2004). The environmental protection (restriction on use of lead shot) (Scotland) (No. 2) Regulations

2004. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ssi/2004/358/

contents/made

HMSO (Her Majesty's Stationary Office). (2009). The environmental

protection (restriction on use of lead shot) Regulations (Northern

Ireland) 2009. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/

nisr/2009/168/contents/made

Hulme, M. (2009). Why we disagree about climate change: Understanding

controversy, inaction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

IUCN. (2016). WCC Resolution 082: A path forward to address concerns over the use of lead ammunition in hunting. Retrieved from:

https ://porta ls.iucn.org/libra ry/sites/ libra ry/files/ resre cfile s/

WCC_2016_RES_082_EN.pdf

NEWTH ET al.

Kabat, G. C. (2017). Taking distrust of science seriously. EMBO Reports,

18, 1052–1055. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.20174 4294

Kahan, D. M. (2002). The logic of reciprocity: Trust, collection action and

law. John M. Olin Center for Studies in Law, Economics, and Public

Policy Working Papers. Paper 281.

Kahan, D. M., Jenkins‐Smith, H., & Braman, D. (2011). Cultural cognition

of scientific consensus. Journal of Risk Research, 14, 147–174. https://

doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2010.511246

Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic computers to factor

analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 141–151.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164460 02000116

Kaiser, H. F. (1970). A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika, 35,

401–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291817

Kanstrup, N. (2006). Non‐toxic shot‐Danish experiences. In G. Boere,

C. A. Galbraith & D. A. Stroud (Eds.), Waterbirds around the world (p.

861). Edinburgh, Scotland: The Stationery Office.

Kanstrup, N. (2015). Practical and social barriers to switching from lead

to non‐toxic gunshot‐a perspective from the EU. In R. J. Delahay & C.

J. Spray (Eds.), Proceedings of the Oxford lead symposium (pp. 98–103).

Oxford, UK: Edward Grey Institute, University of Oxford.

Kanstrup, N. (2019). Lessons learned from 33 years of lead shot regulation in Denmark. In N. Kanstrup, V. G. Thomas & A. D. Fox (Eds.),

Lead in Hunting Ammunition: Persistent Problems and Solutions (Ambio

Vol.48). Stockholm, Sweden: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s13280-018-1125-9

Kanstrup, N., Swift, J., Stroud, D. A., & Lewis, M. (2018). Hunting with

lead ammunition is not sustainable: European perspectives. Ambio,