�Sharon Macdonald (ed.)

Doing Diversity in Museums and Heritage

Cultural Heritage Studies Volume 1

�Sharon Macdonald is Alexander von Humboldt professor of social anthropology at

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, where she directs both the Hermann von HelmholtzZentrum für Kulturtechnik and CARMAH (the Centre for Anthropological Research on

Museums and Heritage).

�Sharon Macdonald (ed.)

Doing Diversity in Museums and Heritage

A Berlin Ethnography

�The publication of this work was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 (BY-SA) which

means that the text may be remixed, build upon and be distributed, provided credit is given to

the author and that copies or adaptations of the work are released under the same or similar

license.

Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures,

photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may

be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely

with the party re-using the material.

First published in 2023 by transcript Verlag, Bielefeld

© Sharon Macdonald (ed.)

https://www.transcript-verlag.de/

Cover layout: Maria Arndt, Bielefeld

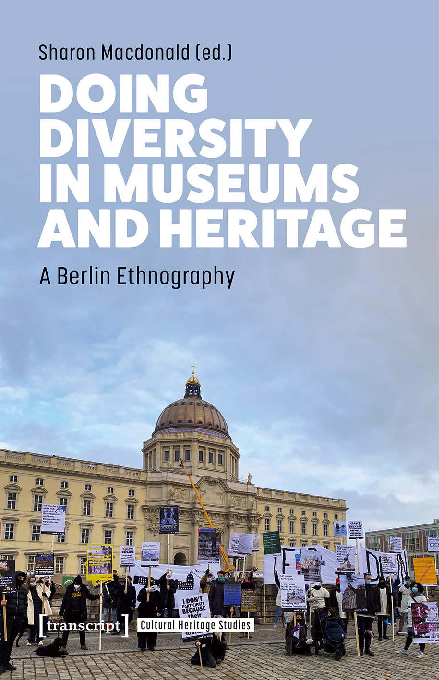

Cover illustration: Opposition to the Humboldt Forum, August 2020. Photograph by Andrei Zavadsky.

Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar

https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839464090

Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-6409-6

PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-6409-0

ISSN of series: 2752-1516

eISSN of series: 2752-1524

Printed on permanent acid-free text paper.

�Contents

Acknowledgements ...................................................................... 7

List of Images ............................................................................ 9

Doing Diversity, Making Differences

Multi-Researcher Ethnography in Museums and Heritage in Berlin

Sharon Macdonald ........................................................................... 13

Talking and Going about Things Differently

On Changing Vocabularies and Practices

in the Postcolonial Provenance and Restitution Debates

Larissa Förster .............................................................................. 57

Being Affected

Shifting Positions at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin

Margareta von Oswald ....................................................................... 77

Beyond Compare

Juxtaposition, Enunciation and African Art in Berlin Museums

Nnenna Onuoha ............................................................................. 97

Polarised Public Perceptions of German Colonialism

Visitor Comments at the DHM German Colonialism Exhibition

Harriet Merrow ..............................................................................117

Changing Street Names

Decolonisation and Toponymic Reinscription for Doing Diversity in Berlin

Duane Jethro............................................................................... 137

�Dis-Othering Diversity

Troubling differences in a Berlin-Brussels Afropolitan

curatorial collaboration

Jonas Tinius ............................................................................... 157

Diversity Max*

Multiple Differences in Exhibition-Making in Berlin Global

in the Humboldt Forum

Sharon Macdonald .......................................................................... 173

Diversifying the Collections at the Museum of European Cultures

Magdalena Buchczyk........................................................................ 193

Collecting Diversity

Data and Citizen Science at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin

Chiara Garbellotto, Tahani Nadim .............................................................211

Exploring the Futurabilities of Museums

Making differences with the Museum Divan at the Museum

for Islamic Art in Berlin

Christine Gerbich ..........................................................................229

Willkommen im Museum

Making and Unmaking Refugees in the Multaka Project

Rikke Gram................................................................................. 247

i,Slam. Belonging and Difference on Stage in Berlin

Katarzyna Puzon ........................................................................... 261

Transnational Entanglements of Queer Solidarity

Berlin Walks with Istanbul Pride March

Nazlı Cabadağ .............................................................................. 277

Difficult Heritage and Digital Media

‘Selfie culture’ and Emotional Practices at the Memorial to the Murdered

Jews of Europe

Christoph Bareither .........................................................................293

Making Differences to Doing Diversity in Museums and Heritage. An

Afterword

Sharon Macdonald .......................................................................... 315

Notes on Contributors ................................................................. 319

�Acknowledgements

This book is a product of the research project Making Differences in Berlin. Transforming

Museums and Heritage in the Twenty-First Century (a title that we later came to use in shortened versions). The project was generously funded primarily by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in the form of a Professorship to myself, Sharon Macdonald. This was

an extraordinary privilege and allowed me to work with an amazing group of researchers,

many of whom contribute to this book. Unlike so many funders, the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation gives an unusual degree of freedom, for which I am grateful not only as

it helped to reduce administrative burdens but also because it meant that it was possible

to reshape the research as it developed, responding to issues and concerns that emerged

in this dynamic field. Alongside the positions funded by the Alexander von Humboldt

Foundation, further much appreciated posts were financed by the Humboldt-Universität

zu Berlin, the Museum für Naturkunde, and the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation.

The funding was also used to establish the Centre for Anthropological Research on

Museums and Heritage – CARMAH – which was located within the Institute of European Ethnology, within the Philosophical Faculty of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

As such, this book and the research more generally, also benefited from discussions with

members of other research projects at and visitors to CARMAH, as well as colleagues

within the Institute, Faculty and wider University. There are too many people to name

here individually but we are grateful to all. Likewise, to many productive discussions elsewhere. In particular, however, a panel that we held at the Heritage Futures conference of

the Association of Critical Heritage Studies, hosted (online) by University College London, in 2020 was an opportunity to collectively present work on the topic of this book

and receive valuable feedback.

Many of those whose work is included in this book were part of an earlier reading

group and read earlier drafts of chapters of some of the others, though as the project and

book were produced over several years, some joined later or left earlier than others. Many

thanks to all for the various and always valuable input. Gratitude also extends to others

who participated in discussions and gave helpful feedback or other support: Tal Adler,

Alice von Bieberstein, Hannes Hacke, Irene Hilden and Anna Szöke. Andrei Zavadsky additionally provided the photograph for the cover as well as for within the introduction.

Extra appreciation is due to Christine Gerbich for helping with mobilizing and manag-

�8

Doing Diversity in Museums and Heritage

ing submissions at an important stage, and to the student assistants, especially Dominik

Biewer and Sarah Felix but also Clara Dröll, Emma Jelinski and Harriet Merrow, for extensive and vital work of chasing picture rights, formatting and bibliographies, liaising

with authors and more. We were fortunate to have been able to enlist the skillful language editor, Dominic Bonofiglio, to improve all of our texts. The Humboldt-Universität

covered the costs to make this book open access. Jakob Horstmann at transcript has been

wonderfully responsive and enthusiastic throughout. He is the only person I know who

says ‘swell’ but it is a good description of working with him. I have been accompanied

in my Berlin adventure by my husband, Mike Beaney, and I thank him for being there

alongside during the long making of this book too.

Conducting a Berlin ethnography has meant that we have interacted with and learned

from many different individuals and groups, even beyond those with whom we more formally worked. Thanks to all for being part of such a stimulating conversation.

Sharon Macdonald, Berlin, June 2022

�List of Images

Cover:

Opposition to the Humboldt Forum, August 2020. Photograph by Andrei Zavadsky.

1.1

Humboldt Forum under construction, July 2018. Photograph by Sharon Macdonald.

1.2

Opposition to the Humboldt Forum, August 2020. Photograph by Andrei Zavadsky.

1.3

Map of German colonies in the German Colonialism Exhibition, 2016, at the German

Historical Museum. Reproduced courtesy of the German Historical Museum.

Photograph by Wolfgang Siesing.

3.1

Logo of the ‘No Humboldt 21!’ Initiative. Reproduced courtesy of No Humboldt 21!

3.2

Logo of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Reproduced by permission of the Stiftung

Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

3.3

Logo of the Stiftung Berliner Schloss. Reproduced courtesy of the Stiftung Berliner

Schloss.

3.4

Ever seen looted art? Poster by No Humboldt 21! Creative Commons License.

3.5

Prussian cultural heritage? Poster by No Humboldt 21! Creative Commons License.

4.1

The temporary exhibitions room in the basement. Photograph by Nnenna Onuoha,

2019. Reproduced courtesy of the Ethnological Museum, State Museums of Berlin.

4.2

Beyond Compare’s official exhibition imagery. Photograph by Nnenna Onuoha, 2019.

Reproduced courtesy of the Ethnological Museum, State Museums of Berlin.

4.3

Beyond Compare smartphone app. Photograph by Nnenna Onuoha, 2019. Reproduced

courtesy of the Ethnological Museum, State Museums of Berlin.

4.4

Two statues, ‘Statue of the goddess Irhevbu or of Princess Edeleyo’(right) and ‘Dancing

putto with a tambourine’ (left) in a glass case. Photograph by Nnenna Onuoha, 2019.

Reproduced courtesy of the Ethnological Museum, State Museums of Berlin.

4.5

Glass case at the entrance to the Bode’s Basilica. Photograph by Nnenna Onuoha, 2019.

Reproduced courtesy of the Ethnological Museum, State Museums of Berlin.

�10

Doing Diversity in Museums and Heritage

4.6 & 4.7

Supplementary materials and the general aesthetic of the Basilica, providing context to

the putto while leaving the Benin statue out of place. Photograph by Nnenna Onuoha,

2019. Reproduced courtesy of the Ethnological Museum, State Museums of Berlin.

4.8

The ‘Basilica’ as a museum space. Photograph by Nnenna Onuoha, 2019. Reproduced

courtesy of the Ethnological Museum, State Museums of Berlin.

4.9

Juxtaposition of sculptures in the Bode Museum. Photograph by Nnenna Onuoha, 2019.

Reproduced courtesy of the Ethnological Museum, State Museums of Berlin.

5.1

Reproduction of page 126 of the visitor book of the exhibition German Colonialism.

6.1

May Ayim Ufer. Joshua Aikins, Decolonial City Tour – The Everyday Presence of the

Colonial Past, Sunday 21 October, 2018. Photograph by Duane Jethro.

6.2

Afrikanisches Viertel. Joshua Aikins, Decolonial City Tour – The Everyday Presence of the

Colonial Past, Sunday 21 October, 2018. Photograph by Duane Jethro.

6.3

Petersallee. Joshua Aikins, Decolonial City Tour – The Everyday Presence of the Colonial

Past, Sunday 21 October, 2018. Photograph by Duane Jethro.

6.4

M-Straße street sign defaced, 20 June 2020. Photograph by Duane Jethro.

6.5

Decolonise the City. M-Straße Ubahn Station defaced, 23 July 2020. Photograph by

Duane Jethro.

7.1

Olani Oweuett, Naomi Ntakiyica, and Jonas Tinius during the panel on the Mapping

Survey at Dis-Othering Symposium, BOZAR, May 2019. Photograph by Lyse Ishimwe.

7.2

Screenshot of a survey question in the SurveyMonkey app during the test phase.

8.1

Tape That sound portraits and artworks. Photograph by Thomas Beaney. Reproduced

courtesy of Stadtmuseum Berlin and Kulturprojekte Berlin.

8.2

Interconnections area in Berlin Global. Photograph by Thomas Beaney. Reproduced

courtesy of Stadtmuseum Berlin and Kulturprojekte Berlin.

8.3

Computer terminal showing visitors’ connections. Photograph by Thomas Beaney.

Reproduced courtesy of Stadtmuseum Berlin and Kulturprojekte Berlin.

8.4

Globe showing multiple connections near the beginning of Berlin Global. Photograph by

Thomas Beaney. Reproduced courtesy of Stadtmuseum Berlin and Kulturprojekte

Berlin.

8.5

Berlianen in Berlin Global. Photograph by Thomas Beaney. Reproduced courtesy of

Stadtmuseum Berlin and Kulturprojekte Berlin.

9.1

The Scottish section of the museum store. Reproduced courtesy of the Museum of

European Cultures, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

9.2

Museum library catalogue entries. Reproduced courtesy of the Museum of European

Cultures, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

9.3

Wedding dress on display in the Museum of European Cultures. Reproduced courtesy of

the Museum of European Cultures, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

10.1

People assemble to look for nightingales during an early morning guided tour in the

Tiergarten Berlin. Photograph by Chiara Garbellotto.

10.2

A nightingale sings on a tree branch while the camera lens focuses to compose the

portrait. Photograph by Daniela Friebel.

10.3

An online map that locates the verified recordings shared by the App users at the end of

the second season of the nightingale project. Reproduced courtesy of the Forschungsfall

Nachtigall team at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin.

�List of Images

11.1

Museum Divan participants Cathrin Schaer, Fadi Abdelnour, Dani Mansour and Farzad

Akvahan engaging with object replicas during a revisiting collections workshop,

November 2015. Photograph by Jana Braun.

11.2

Interactive space with images of Museum Divan participations and comment board in

the exhibition The Heritage of the Old Kings. Ctesiphon and the Persian Sources of

Islamic Art, November 2016. Photograph by John-Paul Sumner.

12.1

Multaka tour in the Bode Museum. Photograph by Milena Schlösser. Reproduced

courtesy of the Museum für Islamische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

12.2

Multaka tour in the Museum of the Ancient Near East. Photograph by Wesam

Muhammed. Reproduced courtesy of the Museum für Islamische Kunst, Staatliche

Museen Berlin.

12.3

Multaka tour in the Museum of Islamic Art. Photograph by A. R. Laub. Reproduced

courtesy of Museum für Islamische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

12.4

Multaka tour in the German Historical Museum. Photograph by Milena Schlösser.

Reproduced courtesy of the Museum für Islamische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

13.1

Youssef performing on the stage © i,Slam.

13.2

Panel discussion during the 2019 Muslim Cultural Days at the Museum of Islamic Art.

Photograph by Katarzyna Puzon. Reproduced courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

and i,Slam.

14.1

The poster of Berlin Walks with Istanbul Pride combining symbolic architectures of two

cities: the Galata Tower, the Brandenburger Tor and the plate of Hermannplatz subway

station. Retrieved from the Facebook event page.

14.2

Istanbul Pride Solidarity Demo, 2018, Hermannplatz, Berlin. Photograph by C.Suthorn /

CC-BY-SA.05 / commons.wikimedia.org

15.1

Christine’s smile (used with permission).

15.2

Adam’s selfie (used with permission).

15.3

Benedikt’s selfie (used with permission).

15.4

Katarina and Haasim looking into the distance (used with permission).

11

�Dis-Othering Diversity

Troubling Differences in a Berlin-Brussels Afropolitan

Curatorial Collaboration

Jonas Tinius

Curatorial practices that address Europe’s colonial legacies through contemporary art

frequently engage with constructions of alterity, difference, and otherness. Many target

the ways in which institutions of artistic and cultural production reproduce ethnic and

geographic forms of othering. The practices on which I focus in this chapter build on a

range of critiques articulated in anti-racist, feminist, and intersectional approaches to

curating and artistic production (Bayer, Kazeem-Kaminski and Sternfeld 2017, Oswald

and Tinius 2020). At the heart of those practices is a ‘double presence of difference’, that

is to say, difference as both a subject of positive identity-formation and an object of critique, an obstacle to social justice and a political strategy for its attainment (Ndikung and

Römhild 2013).1 Markers of identity such as race, gender, class, and regional and cultural

belonging can indicate symptoms of structural discrimination and exclusion, yet they

also allow for the formulation of subject positions that can challenge hegemonic, normative, and canonical structures.

In recent decades, and across a variety of transnational contexts, the notion of diversity has captured many of the tensions implicit in earlier debates on class, nation,

race, identity politics, and difference. Damani Partridge and Matthew Chin suggest that

we may indeed ‘use the current discourse on diversity as a lens to think about question

of economic disparity and social justice’ (2019: 202; see also Appadurai 2013). By asking,

‘Who benefits from diversity, and who might be forgotten?’, they argue that we can ‘productively engage with the different kinds of work [that] are being done under “diversity”’

(2019: 202; 206). Drawing on Sara Ahmed’s analyses of the ways in which diversity works

in ‘institutional life’ (2012), my research has sought to understand the practices of curators working in Berlin, and the complex means by which they strategically operationalise

an anti-racist diversity agenda in identifying larger issues of exclusion in public cultural

institutions. I describe these practices as a form of ‘curatorial troubling’ in which curators seek to ‘stir up potent responses’ (Haraway 2016: 1) to structural forms of exclusion.

For this contribution, I draw on fieldwork conducted between mid-2016 and late-2019

with the Berlin art space SAVVY Contemporary, the BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts in Brus-

�158

Jonas Tinius

sels (Belgium), and Kulturen in Bewegung, a smaller cultural institution in Vienna (Austria) engaged in anti-racist cultural production.2 The collaboration was initially meant to

focus on Afropolitanism, and much of the programming across the three countries focused on African diasporic life in Europe.3 Due to a number of conflicts arising over the

representation of Africa in predominantly white cultural institutions, especially between

SAVVY Contemporary and its director Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung and BOZAR’s

director Paul Dujardin, the project inadvertently became itself an example of the work

and effects of diversity agendas in European cultural institutions.

This chapter describes how Ndikung and his colleagues reframed a large EU-funded

project, initially focusing on Afropolitanism and Afropean identity by turning it around,

suggesting it look instead at the ideas of Africanness in institutions that conduct projects

on Africa.4 The project eventually was renamed to indicate the shift: Dis-Othering: Beyond

Afropolitan & Other Labels.

Dis-othering is a term coined by Ndikung for institutions to analyse their own practices of othering. I was invited as an ethnographer to join the advisory committee of

Mapping Diversity, a quantitative data-gathering effort within the Dis-Othering project

managed by the BOZAR ‘Africa desk’. The aim of Mapping Diversity was to investigate

conceptions and policies of diversity in public culture and art organisations in Austria,

Germany and Belgium. Specifically, its task was to examine the extent to which curatorial projects focusing on diversity (i.e. the presence of persons of African descent in shows

about Africa curated by European cultural institutions) are themselves lacking the diversity they purport to exhibit. As such, the survey was entangled in the problem it sought to

address, namely, the reification of markers of difference such as race, nationality, ethnicity and gender. How can a survey designed to challenge geographically-bound categories

of otherness operate without reproducing them?

This chapter traces the paradoxes of curatorial practices that hope to trouble the reification of diversity. It shows how efforts to expose a lack of diversity at cultural institutions can reinforce the markers it seeks to undo. Focusing on this double presence of

difference as both the subject and the outcome of the diversity survey, I argue that the

querying of diversity is always implicated in the unresolved and ongoing reproduction of

difference. The curatorial probing of diversity for tackling social injustice can also shed

light on the complexity of similar problematisations of difference in the fields of contemporary art, exhibition-making and museum practice.

Curatorial troubling

By late 2017, I had conducted fieldwork for nearly a year on three galleries and project

spaces in Berlin focused on German colonial legacies, migration, and constructions of

difference (Tinius 2018, 2020, 2021). I was planning to conclude the official research

phase when I received a text message from Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung and

Antonia Alampi, the founder and one of the then co-directors, respectively, of one of

my principal fieldwork partners, SAVVY Contemporary. They wanted to talk. We arranged a meeting at SAVVY Contemporary, located in the Wedding district of Berlin.

At the meeting, which took place among the many books and magazines of SAVVY

�Dis-Othering Diversity

Contemporary’s archive, Ndikung and Alampi told me about their collaboration with

BOZAR and expressed regret about the way the project had developed: the inclusion

of people of colour in major European cultural institutions was lagging behind the

demographic realities of the cities in which these institutions were located, Brussels

and Berlin in particular.5 Their concerns echoed what Damani Partridge and Matthew

Chin describe as the way in which ‘diversity has come to mean a sprinkling of color

or the contingent presence of the “disadvantaged” in otherwise majoritarian “White”

or upper-class/high-caste institutions’ (2019: 198). In Ndikung’s view, BOZAR’s project

on the African diaspora was merely symbolic and risked reducing Africa to a mere

theme or project, which Ndikung found particularly inappropriate for a major cultural

institution in a former colonial metropolis with ongoing ties to the African continent.

As Antonia Alampi noted, ’for them “Africa” is just a show’, while ‘for us’, an engagement

with practices of othering ‘is why we exist’. The problem for the two curators was not

their partnership with a large institution on an EU-funded project about Africa, but

what the consequences of such an engagement would be. The two curators were worried

that the project on Europeans of African descent would end up being another project in

which an institution ‘cloaks itself with a thin veil of recognising the diversity of its cities’

without drawing any consequences in terms of its programming or hiring policies. The

two curators criticised the institutional appropriation of difference—in this case, the

label ‘African’ and ‘Afropolitan’—for the purposes of appearing inclusive.

Ndikung and Alampi wanted to know how an institution like BOZAR could conduct

a small albeit significant project on Africa and Afropolitanism without instrumentalising people of colour as temporary tokens to make the project appear inclusive. They also

wondered how SAVVY, an organisation doing critical, mostly independent and, by extension, financially precarious work with artists from Africa and the African diaspora,

could collaborate with BOZAR without falling prey to the same logic of appropriation.

When, they wondered, does collaboration signal approval and complicity? Alampi and

Ndikung thought a mapping survey of the actual employment statistics of large statefunded institutions could provide some ‘hard facts’.

Alampi and Ndikung did not describe the mapping survey as a form of strategic essentialism whose purpose was to identify people of colour working in art and cultural

institutions. Rather, its purpose was, in keeping with their Dis-Othering concept, to provoke reflection on whiteness and diversity in an organisation like BOZAR that aimed to

carry out a large project on its institutional ties to Africa. The survey was part of a complex

attempt to address a practice that Alampi and Ndikung believed was especially strong

in the areas of art and culture: the promotion of diversity in certain types of temporary

projects while keeping the institutional landscape largely unchanged. They were grappling with how they could trouble the tokenism of ‘diversity’ while still partnering with

major institutions.

After our conversation, I agreed to join the mapping survey project. I was curious

how the curators would negotiate the shift from identifying the ‘African’ ties of public

cultural organisations in Belgium, Germany, and Austria to analysing these institutions

‘policies on and reckoning with diversity’. For the curators, conducting a quantitative

survey with markers of difference was a political and moral challenge that ran counter to

the ways in which they sought to problematise statistical science. They were already wor-

159

�160

Jonas Tinius

ried about the double presence of difference and were reluctant to develop a survey that

would promote diversity while reaffirming markers of difference (race, ethnicity, gender)

that they sought to undo in most of their curatorial work. They thus suggested that my

role could be to document their efforts to deal with the basic conundrum. They believed

that the inclusion of an ethnographer like me who was outside the project yet implicated

in its work could be productive. Moreover, the additional perspective could provoke or

illuminate the negotiations of the categories used by the organisations in question. The

outside observation, they hoped, might add a layer of observation on the production of

conventional notions of diversity in cultural organisations and in the survey project itself. In Alampi’s words, the survey’s point was to pose the question, ‘Who is talking about

whom when it comes to diversity and difference?’

The origins of Dis-Othering

During the months after our meeting, I became acquainted with the Dis-Othering

project and its partner staff from Kulturen in Bewegung in Vienna and from the Africa

desk at BOZAR, including its director, Kathleen Louw. It seemed curious to me that a

project could so abruptly shift gears. What started as a study focused on Afropolitanism

in Europe swerved to an interrogation of its own premises and of diversity in Europe’s

cultural institutions. How did this come about?

Ndikung’s official curatorial statement of the Dis-Othering project begins with an

observation that hints at the need to use and reformulate received notions of difference.

Just in the nick of time when we, by repetition and reiteration, start believing our

own concepts that we have postulated and disseminated…we seem to be experiencing a quake that pushes us …to reconsider who and how one bears historical

Othering, reconsider the mechanisms of rendering Other, as well as reconsidering

who represents whom or who tries to shape whose future in contemporary societies

and discourses (2019: 3).6

SAVVY’s curatorial troubling is marked by self-aware political positioning.7 The ‘quake’

that made them reconsider forms of othering was triggered in part by ‘geographical specification-ing’ (2019: 3): the museum practice of highlighting specific regions of the world

for a temporary period of time. As Ndikung puts it:

What does it mean to put together an ‘Africa exhibition’ or an ‘Arab exhibition’

today, as we see in the New Museum, MMK Frankfurt, BOZAR Brussels, Fondation

LV and many other museums in the West? (…) [H]ow would one represent the 54

African countries, thousands of African languages, and communities within such an

exhibition? These issues necessitate re-questioning and reconsidering (2019: 4).

Ndikung identifies seven ways that Dis-Othering responds to a ‘geographical specification-ing’ often promoted under the heading of soft-power diplomacy and inclusion.

Most importantly from my perspective, Ndikung writes that ‘Dis-Othering starts with

the recognition of the acts and processes of othering’ (2019: 5). In this sense, the concept

of Dis-Othering is already a Dis-Othering practice insofar as it positions the curator in a

�Dis-Othering Diversity

conscious and critical relation to host institutions. As Ndikung elaborates, Dis-Othering

considers how

social identity building is not made by projecting on the so-called ‘Other,’ but rather

a projection towards the self. A self-reflection. A boomerang. … It is about acknowledging and embodying the plethora of variables that make us be (2019: 5).

Ndikung describes a position in which institutional introspection and subjective selfanalysis can be mobilised for the purposes of anti-discrimination. It is a position that

reshuffles the genealogies of Othering—in line with the efforts of Seloua Luste Boulbina

(2007), Arjun Appadurai (1986), and Michel-Rolph Trouillot (2003)—using new postcolonial language that is at once poetic and political. The project statement is a gesture of

‘theoretical accounting’ (Smith 2015: 15) that situates and affirms Ndikung’s epistemological jurisdiction vis-à-vis other institutions while shifting the discussion of othering

to one of institutional self-critique. As Ndikung wrote in an earlier version of the text,

the curatorial statement is ‘a reaction to the invitation to exercise Afropolitanness’.8

The SAVVY’s curatorial concept bears the imprint of this critique in its subtitle: Beyond Afropolitan & Other Labels. The subtitle pokes fun at the tokenistic usage of the

prefix ‘Afro-’ in cultural institutions. But the criticism voiced by Ndikung and the Berlin

team went further. As later became evident during the project’s final conference in May

2019, their criticism was not a response merely to BOZAR’s engagement with minorities,

particularly of African descent.9 It also targeted the way that institutions, which work on

‘Africans’, or those of ‘African descent’ (or ‘afro-descendant’), do not include those people among its permanent staff; instead they invite them to contribute to programming

temporarily on an unpaid or low-paid basis. BOZAR is a ‘differentiating institution’ in

the sense that it produces geographically-bounded, tokenistic, and even racialised images of Africa. As Ndikung writes, SAVVY was concerned that their project might serve

a similar function for BOZAR, leading to a ‘parasitical incorporation’ of critical work in

an otherwise ‘white’ institution that, in their eyes, did little to further more substantial

engagement with African scholars, artists, personnel, publics, and programming (2017).

Ndikung and Alampi’s Dis-Othering project was meant as a critique of institutional ‘othering’ practices and well-intended ‘conceptual labels’ such as Afropolitan, which ignore

the broader context and fail to look at ‘what they actually do and what processes of identity construction they encourage’.10

The critical reorientation, which I observed unfold during fieldwork in Brussels at

BOZAR and at SAVVY Contemporary in Berlin, brought a level of critical reflection to the

ways in which institutions and projects can produce difference. Dis-Othering

is not about the ‘Other’—which is just the ‘product’. The project is a deliberation on

the amoebic and morphed methodologies employed by institutions and societies at

large in constructing and cultivating ‘Otherness’ in our contemporaneity. It is about

the commodification and the cooption of the ‘Other’, strategies of paternalization

used in the cultural field.11

Ndikung, Alampi, and their expanded team are part of Berlin’s ecology of cultural institutions. Their organisation is diverse in terms of its inclusion of women and people of

colour, and other directors of cultural institutions in Berlin and beyond regard them as

161

�162

Jonas Tinius

the vanguard of a progressive post-colonial agenda. In a conversation with me, Ndikung

and Alampi said that their position was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they

were pleased with the recognition they received for issues regarding contemporary art

from African perspectives; on the other, they worked with larger institutions whose desire for ‘representation’ relied on a merely temporary inclusion of African perspectives.

Ndikung and Alampi’s curatorial troubling led them, therefore, to a sub-project: interrogating policies on diversity.

The mapping diversity survey

The SAVVY mapping survey was designed to assess diversity at major cultural institutions in Germany, Belgium, and Austria. Initially, it focused on the distribution of class,

race, and gender among curatorial and executive personnel. In view of the difficulty of attaining such sensitive data and several SAVVY team members’ ‘discomfort with the simple positing of such markers of identity as “facts”’, Ndikung and Alampi decided that the

survey should also examine the ways in which cultural organisations understand diversity. The survey concentrated on directorial staff because the SAVVY curators and other

members of the mapping survey team felt that it was on this level that decisions about

personnel, programming, and public outreach—the three p’s—would be made.

In the first few months, the partners discussed the scope of the survey via email and

in online meetings. Due to the limited funding for research (the Berlin team relied on external funding from small grants and private research scholarships), they restricted the

survey to institutions mainly involved in arts or culture production and kept the number

to five institutions per country from its three largest cities. Moreover, they decided to use

institutions in which at least 70 percent of the funding comes from public sources. Publicly funded institutions, they argued, could reasonably be expected to take into account

the demographics of the city and country that finance them.

Selection, data and privacy

Choosing which institutions to survey proved contentious. Team members were uncertain whether it would be a good idea to identify institutions based on ‘best practice’,

‘worst practice’, or name recognition. Some wondered whether the project should focus on different types of institutions (universities, museums, performance venues) or

on different organisations within a broad institutional category (cultural sector, public

sphere, programming)? The framing would affect the ultimate selection. For instance,

programming staff at a museum are different from programming staff at a small-scale

art space. In a similar vein, SAVVY Contemporary would feature as a ‘best-practice’ type

of organisation given the high percentage of women and persons of colour working there,

while BOZAR would be seen a ‘bad practice’ institution, with its white middle-class director and its predominantly white executive staff. Long debates ensued about whether

the aim would be to expose the assumed lack of diversity in one institution or to provide

statistical facts about the diversity in another. For example, the SAVVY team identified

�Dis-Othering Diversity

the Humboldt Forum as a case to be ‘exposed’, but the idea was abandoned due to the institution’s complicated organisational structure (Häntzschel 2017; Macdonald, Gerbich,

and Oswald 2018).

The Mapping Diversity advisory committee found that while the data gathered might

not be on the scale of larger regional or national surveys, the project stood to provide

meaningful data on the diversity of staff in decision-making positions along with their

particular understanding of diversity. But the committee suggested that it would be

helpful not only to approach institutions via formal email inquiries but also to interview

‘gatekeepers’, i.e. directors or head curators most likely to decide whether or not to send

the surveys to their core staff. Hence, the team invited gatekeepers from the institutions

selected for the survey to meetings in the hope of convincing them to participate.

After consultations with the BOZAR legal department and the legal team of the Creative Europe programme, the Mapping Diversity teams formulated short ethical and legal statements.12 But the country teams remained unclear about how to transmit the

survey data to the participating institutions. Although they broadly agreed on the use

of anonymous data, some wondered whether this would miss the point of the project,

which was to determine how major public cultural institutions deal with diversity. Would

producing general statistics for each country be meaningful? Might it be necessary to

specify and differentiate the data? How would the data help identify particular kinds of

diversity. Would not the project’s ethical and political commitment to anonymity make

it impossible to make meaningful statements about diversity? The conundrum here was

the tension between ‘private’ and ‘political’ data. Some participants might refuse to share

‘private’ data to conceal sensitive information. Yet the ‘private’ data seemed likely to provide the most relevant insight into the politics of diversity.

Gatekeeper interviews

The issues regarding data use continued in the gatekeeper interviews. For instance, a representative from a well-known German cultural institution expressed discomfort about

the project’s results and how the data would be put to use. The team members believed

that the collaborative nature of the project— all of the partners involved were cultural

institutions, after all—would help establish trust and encourage participation. But some

gatekeepers were not convinced. ‘We don’t want our data to be used in some form of artistic project where the outcome and form is unclear to us’, one respondent said. Other

interviewees expressed scepticism on other, altogether opposite grounds. The links of

the project to universities—including my presence in the interviews as a white male anthropologist—raised concerns that the data would be used in academia and therefore

detached from a shared artistic context.

On a whole, the gatekeepers made clear to the team that, while they were sympathetic

to the general aims of the project and were happy to participate in the interviews, we

could not distribute the results of our survey. For it was not ‘sufficiently clear’ what would

happen with the survey, whether public authorities could access the data or whether the

project would reframe the data in ways beyond the institutions’ control. Participating

institutions from Austria were worried that the information might be used against them

163

�164

Jonas Tinius

by the government, which at the time was composed of a right-wing coalition between

the ÖVP (Austrian People’s Party) and FPÖ (Freedom Party of Austria). Tonica Hunter, the

then research lead for Kulturen in Bewegung, commented on the situation during a talk

at the final BOZAR symposium:

Several institutions that participated in our ‘let’s talk about Dis-Othering’ symposiums who then agreed to be included in the mapping, later declined for various

reasons…We found the pattern pertinent given the tense political situation in Austria

in view of its black-blue government and the threatened (and real) cuts to the cultural sector. The diversity of cultural institutions is not an easy topic for institutions,

who seem to believe that the exercise will lead to critique rather than to the kind

of insight that could help bring about improvements and address shortcomings.

The issue, therefore, was not only about managing data but also about the mapping itself.

As the project team noted during the final conference in Brussels, the term mapping is

associated with colonial practices such as systemic governmental control, geographic information systems, and other forms of knowledge acquisition, which have often targeted

marginalised peoples (Rose 2007).

7.1 Olani Owunnet, Naomi Ntakiyica, athe nd Jonas Tinius during panel on the Mapping Survey

at Dis-Othering Symposium, BOZAR, May 2019. Photograph by Lyse Ishimwe.

As the process unfolded and interviews were coordinated, the project’s advisory committee (of which I was a member in my capacity as research coordinator and ethnographer) decided that it would be helpful to document the survey deliberations. It had

become evident to most participants that almost every step of the survey—from design

�Dis-Othering Diversity

and implementation to analysis—involved a fundamental questioning of the survey categories and the purpose they were meant to achieve. The team members recorded the

deliberations in several kinds of documents, regularly contributed new documents, and

reviewed the contents. The process was also discussed with team members during the

final Dis-Othering Symposium at BOZAR in Brussels in 2019.

Survey design

The mapping coordination team at SAVVY Contemporary discussed at length the precise

organisation of the survey. Each of the research teams had access to the survey software

SurveyMonkey, which provides a fairly straightforward interface for designing surveys

(similar to website design software like Weebly or WordPress) and for sharing surveys

and exploring data sets in visualised form.

The teams decided on a 40-question survey, beginning with drop-down optional

questions on economic issues and general questions covering age, nationality, location,

gender, sexual orientation, religious orientation or belief, immigration history, and

education. These included an ‘other’ category and several open boxes. Next was a set of

broader questions about the diversity of staff, diversity policies, job criteria, and general

assessments such as ‘How important is diversity to your institution?’ and ‘Do you think

you contribute to the diversity of a) the public/audience, b) the programmes/curatorship

or c) the personnel?’ For many of the questions, the survey requested elucidation, including prompts such as ‘If yes, why and how?’ or ‘If yes, please elaborate’. These allowed

for critique and disagreement to avoid implicit bias.

The research team members held intense discussions about which markers of identity were considered ‘sensitive’, including ones liable to discrimination such as gender,

country of birth, nationality, ethnic background, and sexuality. They collected several of

the categories from existing surveys in Germany such as online discrimination questionnaires conducted by the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. The teams included ‘current

nationality’ and ‘nationality at birth’ to account for migration and changes of nationality

over time. A particular contentious category was ‘ethnic background’. Some team members disputed the relevance or existence of ‘ethnicity’; and everyone rejected the category

of race, which, despite its frequent use in the Anglophone world, was not considered appropriate in Continental Europe. Instead, the team decided to specify the difficult notion

of ‘ethnos’ by asking respondents whether they belong ‘to an ethnic minority which is not

linked to recent migration’. All questions related to ethnicity came with the option ‘Prefer not to say’. Team members agreed that the survey categories could not be assumed to

be ‘exhaustive’. Furthermore, though questions about nationality had a long list of dropdown options, they included the box ‘Add your current nationality / nationality at birth,

if it is not on the list’. Participants were also given the choice to choose multiple nationalities, with options ranging from pre-defined countries to open boxes.

165

�166

Jonas Tinius

7.2 Screenshot of a survey question in the SurveyMonkey app during the test

phase.

The team members discussions revealed a broader problem when it came to diversity:

the multiplication of differences extended the problem of difference by ‘maximising’ differentiation. Yet, it also became evident that the categories that were most contentious

were also the ones that mattered most to team members. This suggested that the core

of the ‘diversity’ problem in the survey involved categories of identity that themselves

created discomfort. These included the concepts of race, sexuality, sexual orientation,

and their translatability (or untranslatability, as with race and the German Rasse, which

immediately recalls Nazi racial ideology). In our online video conferences several members self-identified as persons of colour or of African descent. It was noticeable that the

positionality of the team members across categories of whiteness, sexual orientation,

�Dis-Othering Diversity

and institutional affiliation played a role in the discussion, and many were reluctant to

fix a category that they experienced as discriminatory. Their response revealed the nonneutrality of the categories, and how the meaning of the categories change depending

on who is using them (e.g. me as a white German male versus a person of colour). The

challenge here lay not in maximising the number of diversity markers, but in crafting a

survey that overcomes discrimination without reifying difference.

Conclusion

Curatorial practices seeking to create infrastructures for ‘greater diversity’ within cultural institutions often essentialise difference for strategic purposes. The process is as

paradoxical as it is unavoidable. Yet some institutions adopt elements of strategic essentialism without reflecting on the difficulties of diversity. BOZAR and the Dis-Othering

project are a case in point: a well-intended project ended up causing such a stir within its

own team that the project turned on itself and became a study of failure and critical selfreflexivity. This is not an isolated problem. The language of wokeness and strategic criticality pervades capitalist and cultural institutions alike (Ahmed 2021, Boltanski and Chiapello 2007 [1999], Bose 2017, Leary 2018). The risk here is that ‘diversity’ becomes a technocratic issue, packaged in ‘proposals’ and handled by short-term ‘diversity managers’

who serve to conceal underlying structural inequalities instead of addressing them.

In this chapter, I focused on two dimensions of difference-making for two different

ends. First, I considered the criticisms of BOZAR and the reformulation of the SAVVY

Contemporary project on Dis-Othering in response. The revised SAVVY project shaped

the terms used in the mapping diversity project, which speaks not of ‘difference’, but of

‘Othering’ and ‘Dis-Othering’. These depart from a particular genealogy of postcolonial

theory and thought. These include Afropeanism, in which the practices of SAVVY Contemporary are situated, and more recent institutional discussions on diversity management, which echo through the Humboldt Forum exhibition addressed by Sharon Macdonald.

Dis-Othering is a curatorial neologism that has an ethnographic function insofar as

it describes a particular problem and situation. It is a form of curatorial troubling coined

by Ndikung and Alampi to facilitate critical thinking about the way in which public cultural institutions produce geographically-bounded ideas of cultural otherness. The questions that led to the mapping diversity survey in the Dis-Othering project centred on representation and infrastructure: who can represent whom? In whose interest is diversity

work done? How can projects critically reflect on the undoing of Othering practices, and

turn their gaze onto themselves?

A second dimension of difference-making that I addressed is how ‘diversity’ became

the central problem of the Mapping Diversity survey. The attempt to interrogate what diversity and diversity-work means for cultural institutions led to an ambivalent and often

contradictory discussion of how to define diversity without recreating the categories that

the project as a whole sought to question. The group discussions—and the references to

similar surveys (Marguin and Losekandt 2017)—illustrates the primacy of ‘diversity’ in

the project.

167

�168

Jonas Tinius

The core analytical contribution of this chapter is to draw out the tensions of difference: on the one hand, difference can be a problem (producing geographical, cultural,

and even racialised distinctions between ‘Europeans’ and ‘Africans’) and an obstacle (preventing non- or post-racial forms of artistic expression). At the same time, difference

and diversity are part of the performative consequences of the survey, which risked reproducing the very essentialism of diversity work that the project as a whole wanted to

overcome.

Perhaps, as a participant mentioned at the final BOZAR conference, the significance

of the project lies in sparking a conversation about diversity agendas within and among

cultural institutions. Due to the reasons I outlined above, the mapping survey did not

produce the scale and scope of quantitative results that the curators initially hoped for,

and the reasons for this failure are themselves testament to the broader problem the survey sought to address. Too little money, time, and human resources were allocated to

the mapping project, which, as the BOZAR manager of the project commented, could

have been the subject of an entire EU-project itself—as could failure itself (Appadurai

and Alexander 2019). Yet, within the boundaries and limitations of the project, the survey helped sensitise the participating institutions to the complexity and multiple forms

of difference at play. And it began a conversation about the need to reflect on, refine, and

dis-other strategic mobilisations of diversity in the cultural field and beyond.

Acknowledgements

The fieldwork for this chapter was conducted during a research fellowship for Making

Differences: Transforming Museums and Heritage in the Twenty-First Century, at the Centre for

Anthropological Research on Museums and Heritage (CARMAH). The fellowship was

funded by Sharon Macdonald’s Alexander von Humboldt Professorship. I am grateful

to Sharon Macdonald along with Arjun Appadurai, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung,

Antonia Alampi, Lynhan Balatbat-Helbock, Olani Ewuett, Tonica Hunter, Kathleen

Louw, Naomi Ntakiyica, Elena Ndidi Akilo, and Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov for their helpful

comments.

Notes

1

2

At the time of writing, one of the discussions involving members of SAVVY Contemporary coalesced around the debate on the overwhelming presence of white men.

See the open letter by the organisers (https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/open-lett

er-regarding-lack-of-diversity-in-nrw-forum-exhibition/8345) and a video recording of an event at the Red Salon of the Berlin Volksbühne (http://www.youtube.com

/watch?v=G2zejVIrAdI), which included several of the interlocutors mentioned in

this chapter. All links were last accessed on 8 February 2022.

Further project partners include the Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren),

Afropean London, and Obieg Magazine (Poland). The Dis-Othering project

website at BOZAR can be found here: https://www.bozar.be/en/calendar/dis-

�Dis-Othering Diversity

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

othering#event-page__description (last accessed, 8 February 2022). The Dis-Othering project was funded by the EU’s Creative Europe programme, which possesses a

budget of 1.46 billion euros.

The concept of Afropolitanism has its roots in pan-African theoretical texts, but now

includes a broader set of reflections on the relationship of urban space to African

cultural production and to diasporic citizenship practice (Weheliye 2005). The concept has thus moved from Africa’s post-independence era to the postcolonial theorisation of transnational forms of belonging.

Afropean: Notes from Black Europe (2019), by Johny Pitts, an affiliated member of the

project discussed in this chapter, engages with the notion in order to overcome the

‘hyphenated identities of Afro-and’ (personal communication).

Ahead of the 2019 European elections, a Guardian newspaper op-ed with the heading

‘Why is Brussels so White? The EU’s Race Problem That No One Talks About’ (2019)

states that ‘Migrants, minorities and people of colour are almost absent from tomorrows’ list of prospective MEPs.’ As the author, Sarah Chander, writes, the representation of people of colour in the European parliament is ‘less than 3%, and Italy’s Cécile Kyenge is the sole black woman.’

The concept was written in response to BOZAR’s interest in collaborating with

SAVVY Contemporary. It was subsequently revised and updated by the curator to

reflect the ongoing processes and experiences in this collaboration. The project

statement can be found on the SAVVY Contemporary website: www.savvy-contemporary.com/site/assets/files/4038/geographiesofimagination_concept.pdf (last

accessed 8 February 2022).

In a chapter co-authored with Sharon Macdonald, I reflect on the recursivity of such

concepts in curatorial discourse (Tinius and Macdonald 2019). Marcus Morgan and

Patrick Baert’s book Conflict in the Academy (2015), on positioning theory and the role

of discursive statements in the creation of intellectual spheres, is a relevant point of

comparison.

In June 2019, when I finished a first draft of this piece, the shortened earlier statement could still be found on the BOZAR website here https://www.bozar.be/en/cal

endar/dis-othering#event-page__description. It had since been removed.

The conference Race, Power and Culture: A Critical Look at Belgian Cultural Institutions (22–24 May 2019) stirred up a heated discussion and even a boycott of BOZAR.

Various attendees, among them members of the original advisory committee, felt

that they had been lured to participate on false promises, only to appear as tokens

of a thinly veiled diversity agenda.

The quote appears in the shorter version of Ndikung’s curatorial concept on the

BOZAR website.

Ibid.

Excerpts of the invitation email include these passages: ’The survey is anonymous. It has been reviewed by the legal department of the Centre of Fine Arts

(Brussels) (project leader), and assessed compliant with the new EU General Data

Protection Regulation (GDPR). The collected survey data: is collected for scientific

research only; will be accessible only to a scientific committee comprising a total

of 6 researchers from the three partner countries, who will perform a qualitative

169

�170

Jonas Tinius

analysis of interview material and quantitative results, and direct the graphic and

digital visualisation of survey results; will not be shared with any other research or

projects (3rd parties); will be destroyed after 2 years’.

References

Ahmed, S. 2012. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham, NC:

Duke University Press.

Ahmed, S. 2021. Complaint! Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Appadurai, A. 1986. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Appadurai, A. 2013. ‘Diversity and disciplinarity as cultural artifacts’, in C. McCarthy, W.

Crichlow, G. Dimitriadis, and N. Dolby (eds), Race, Identity, and Representation in Education, 2nd ed., 427–437. London, New York: Taylor and Francis.

Appadurai, A., N. Alexander. 2019. Failure. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Baert, P., and M. Morgan. 2015. Conflict in the Academy. A Study in the Sociology of Intellectuals. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Bayer, N., B. Kazeem-Kaminiski, and N. Sternfeld (eds). 2017. Kuratieren als antirassistische

Praxis. Kritiken, Praxen, Aneignungen. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Boltanski, L., and È. Chiapello. 2007 [1999]. The New Spirit of Capitalism. Trans. Gregory

Elliott. London, New York: Verso.

Bose, F. von 2017. ‘Strategische Reflexivität. Das Berliner Humboldt Forum und die

postkoloniale Kritik’, Historische Anthropologie, 3: 409–417.

Boulbina, S. L. 2007. ‘Being Inside and Outside Simultaneously. Exile, Literature, and the

Postcolony: On Assia Djebar’, Eurozine. 02 November 2007. www.eurozine.com/being-inside-and-outside-simultaneously/ (accessed 8 February 2022).

Chander, S. 2019. ‘Why is Brussels so white? The EU’s race problem that no one

talks about’, The Guardian, 19 May 2019. www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/may/19/eu-race-problem-european-elections-meps-migrants-minorities

(accessed 8 February 2022).

Häntzschel, J. 2017. ‘Verstrickung als Prinzip’, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 20 November 2017.

www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/kulturpolitik-verstrickung-als-prinzip-1.3757309 (accessed 8 February 2022).

Haraway, D. J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, London: Duke University Press.

Law, J., and R. Williams. 1982. ‘Putting Facts Together: A Study of Scientific Persuasion’,

Social Studies of Science, 12(4): 535–558.

Leary, J. P. 2018. Keywords. The New Language of Capitalism. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Macdonald, S., C. Gerbich, and M. von Oswald. 2018. ‘No Museum is an Island: Ethnography beyond Methodological Containerism’, Museum & Society, 16(2): 138– 156.

Marguin, S., and T. Losekandt. 2017. Studie zum Berliner Arbeitsmarkt der Kultur- und

Kreativsektoren. Berlin: Bildungswerk Berlin der Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung.

Ndikung, B. S. B. 2017. ‘The Globalized Museum? Decanonisation as Method: A Reflection in Three Acts’, Mousee Magazine. www.moussemagazine.it/the-globalized-mu-

�Dis-Othering Diversity

seum-bonaventure-soh-bejeng-ndikung-documenta-14-2017/ (accessed 8 February

2022).

Ndikung, B. S. B. 2019. ‘Dis-Othering as Method. LEH ZO, A ME KE NDE ZA’, Curatorial Concept, published online. Berlin: SAVVY Contemporary. www.savvy-contemporary.com/site/assets/files/4038/geographiesofimagination_concept.pdf (accessed

8 February 2022).

Ndikung, B. S. B., and R. Römhild. 2013. ‘The Post-Other as Avant-Garde’, in D. Baker,

and M. Hlavajova (eds), We Roma: A Critical Reader in Contemporary Art, 206–225. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Oswald, M. von, and J. Tinius. 2020. ‘Introduction: Across Anthropology’, in M. von Oswald, and J. Tinius (eds), Across Anthropology. Troubling Colonial Legacies, Museums, and

the Curatorial, 17–44. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

Partridge, D. J., and M. Chin. 2019. ‘Interrogating the Histories and Futures of “Diversity”: Transnational Perspectives’, Public Culture, 31(2): 197–214.

Pitts, J. 2019. Afropean: Notes from Black Europe. London: Penguin.

Rose, N. 2006. The Politics of Life Itself. Biomedicine, Power, and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First

Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Smith, T. 2015. Talking Contemporary Curating. New York: ICI.

Tinius, J. 2018. ‘Awkward Art and Difficult Heritage: Nazi Art Collectors and Postcolonial

Archives’, in T. Fillitz, and P. van der Grijp (eds), An Anthropology of Contemporary Art,

130–145. London: Bloomsbury.

Tinius, J. 2020. ‘Porous Membranes: Hospitality, Alterity, and Anthropology in a Berlin

District Gallery’, in M. von Oswald, and J. Tinius (eds), Across Anthropology. Troubling Colonial Legacies, Museums, and the Curatorial, 254–277. Leuven: Leuven University

Press.

Tinius, J. 2021. ‘The Anthropologist as Sparring Partner: Instigative Public Fieldwork, Curatorial Collaboration, and German Colonial Heritage’, Berliner Blätter. 83: 65–85.

Tinius, J., and S. Macdonald. 2019. ‘The Recursivity of the Curatorial’, in R. Sansi (ed.),

The Anthropologist as Curator, 35–58. London: Bloomsbury.

Trouillot, M.-R. 2003. ‘Anthropology and the Savage Slot: The Poetics and Politics of Otherness’, in Global Transformations. Anthropology and the Modern World, 7–28. New York:

Palgrave.

Weheliye, A. G. 2005. ‘Sounding Diasporic Citizenship’, in Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic

Afro-Modernity, 145–197. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

171

�

Jonas Tinius

Jonas Tinius