Work-Life Balance Through Interval Training

Work-Life Balance Through Interval Training

Uploaded by

hilerishahCopyright:

Available Formats

Work-Life Balance Through Interval Training

Work-Life Balance Through Interval Training

Uploaded by

hilerishahCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Work-Life Balance Through Interval Training

Work-Life Balance Through Interval Training

Uploaded by

hilerishahCopyright:

Available Formats

WORK-LIFE BALANCE

Work-Life Balance Through Interval Training

by Scott Behson

JUNE 03, 2014

At aThirdPath Instituteconference a few weeks ago, a great discussion arose around the fact that workloads tend to ebb and ow, and its important to

know how to alternate between periods of peak eort and recovery. Before long, someone noted the analogy to high performance in sports, and used a

phrase that piqued my curiosity:Corporate Athlete. I loved the term so much I jotted it down, thinking I might make something of it in my writing and

consulting. Then I Googled it.

Oops. Apparently, Jim Loehr and Tony Schwartz have already made quite a lot of the term corporate athlete, having coined it way back in a2001 HBR

article(I was only 13 years late to the party!) and explored it in a series ofbest-selling booksabout engagement, energy, and business success. So much

for my plan to unleash it on the world.

But I was all the more glad to nd so much work already done on corporate athleticism, because it has a lot to oer my eld: the challenges faced by

working parents.

Loehr and Schwartz look at how the winners in the world of sports prepare for competition and then apply these techniques to managerial work. They

urge executives to train in the same systematic, multilevel way that world-class athletes do. No, CEOs are not forced to run wind sprints (although

some do). Rather, they are coached in a holistic program designed to help them attain and sustain- the highest performance at their craft.

What strikes me most in the writing Loehr and Schwartz have done is their frequent use of the word balance.In particular, they see great athletes and

corporate athletes achieving the right balance across three critical dimensions:

1. Mind and Body

2. Performance and Development

3. Exertion and Recovery

Of course, people trying to succeed both at work and at home are constantly thinking in terms of balance. But perhaps Loehr and Schwartz have given

us a more nuanced way of thinking about what needs to be balanced. Using their dimensions, how might someone go about becoming a superstar WorkLife Athlete?

First, lets think about thatmind-body balance. For athletes, the classic mistake to avoid is focusing only on preparing ones body for the game. Great

coaches equip their players to win the mental game as well the physical one. Executives, by contrast, are too likely to grind away at intellectual tasks

and overlook that their bodies must be healthy if they are to have the energy to perform well on the job. As Loehr and Schwartz put it,a successful

approach to sustained high performance must pull together [many] elements and consider the person as a whole. It must address the body, the

emotions, the mind, and the spirit.

For work-life athletes, mind-body balance suggests that we shouldget enough sleep, eat reasonably well, engage insome exercise- and make room in

our lives forsocial interaction, me time, and perspective-seeking through reection and meditation or prayer. You dont have to be in perfect shape to

be good at your job or eective as a parent. But if we neglect our bodies, or spirits, we may not have enough sustained energy for eectiveness in either

work or family, let alone both.

Theperformance-development balancealso has a particular relevance tothe work-life realm. Athletes know that the vast majorityof their eort is

spent on development, preparing for the performance they must put in during actual competition. In business, it feels like the proportions are inverted:

every day executives must perform, and only a tiny fraction of their time is set aside for professional development. But actually, the athletes

understanding of the balance would make more sense for business people, too. Athletes in their development days focus on individual elements of their

game and build their capacity in the fundamentals; on competition days, they pull all the pieces together and push performance to the maximum.

Likewise in business, there are those high-stakes occasions when managers can only pull o what they are trying to accomplish by drawing on every

competence they have; but between big game days, many assignments could be focused on honing particular fundamentals.

Now consider that working parents also have moments when their capabilities as work-life athletes are seriously put to the test and their performance

has the greatest consequences. In those moments, they too need to pull together all their resources and abilities to make the right moves. And ideally,

they would have prepared for those moments by deliberately developing individual elements in situations where the stakes were not so high.

Anyone who wants to sustain a performance edge needs to gure out how to keep developing new capabilities, and not just keep drawing on existing

ones. If this cant be accomplished through daily tasks, then it requires regularly scheduled time to be set aside. Whether its protecting 30 minutes

every other day to read up on industry developments, listening to a language-instruction course during the morning commute, or trying a new recipe

every week, turning o the performance pressure creates more openness to new approaches and heightens performance in the long run.

This brings us, nally, to theexertion-recovery balancethat Loehr and Schwartz see great athletes managing so well. In the living laboratory of sports,

they write, we learn that the real enemy of high performance is not stress, which, paradoxical as it may seem, is actually the stimulus for growth.

Rather, the problem is the absence of disciplined, intermittent recovery. For example, in weight lifting, one stresses muscles to the point where their

bers literally start to break down. However, after an adequate recovery period, the muscle not only heals, it grows stronger. Without rest, one ends up

with be acute and chronic damage.

In business, demanding projects, with tight deadlines and stretch goals, can be great but cant be unremitting. Occasional overwork is a necessity, at

work and in the rest of our lives, butchronic overworkrobs us of our resilience. This reduces our performance over time, and causes damage in our

work and personal lives. Similarly, too many working parents go full-tilt, non-stop to tackle all they have to do without allowing themselves the

recovery time needed for sustainable eectiveness. Recovery for the work-life athlete might not come when they jump from the demands of one

front to the demands of another. It might require taking breaks from the jumping itself. A good start might be to arrange for some standing no/limited

contact time slots with managers and coworkers (e.g., specifying that no one should expect a response to an email between 6:30 and 9:30 pm). For that

matter, why not set no screen hours at home, when everyone stays o their phones, tablets, and other devices and is available to each other?

From a management standpoint, we need to rethink the notion that non-performance time is wasted time. Instead, we need to see that recovery is a key

component of sustained high performance. This means we must resist continually increasing the time demands we put on our employees and expecting

our employees to be constantly on call even after hours. We need to encourage our employees to take lunch breaks, relax on weekends, and actually

take their vacation days, unplugged (and also do these things ourselves). By helping to strike the right balances, we can build the work-life athleticism

we need when the stakes are highest.

Scott Behson is a Professor of Management at Fairleigh Dickinson University, and the author of The Working Dads Survival Guide: How to Succeed at Work and at

Home. He writes about work and family issues for Time, WSJ, the Hufngton Post and his blog, Fathers, Work and Family. A national expert in work-family issues,

Scott was a featured speaker at the White House Summit for Working Families. Follow him on Twitter @ScottBehson.

This article is about WORK-LIFE BALANCE

FOLLOW THIS TOPIC

Related Topics: MANAGING YOURSELF |

STRESS

Comments

Leave a Comment

POST

43 COMMENTS

kennethfung

2 years ago

Scott, the term corporate athletewas new to me too and its a good one. In particular, the need for recovery time which I think is absolutely essential particularly with

knowledge work. The brain simply cannot constantly analyze, create or synthesize. It needs both rest time and time to take on new information. One question Scott- who do you

think should be in charge of insuring our corporate athletes get into top condition HR, managers, or executives at the top?

00

REPLY

JOIN THE CONVERSATION

POSTING GUIDELINES

We hope the conversations that take place on HBR.org will be energetic, constructive, and thought-provoking. To comment, readers must sign in or register. And to ensure the quality of the discussion, our moderating team will

review all comments and may edit them for clarity, length, and relevance. Comments that are overly promotional, mean-spirited, or off-topic may be deleted per the moderators' judgment. All postings become the property of

Harvard Business Publishing.

Work-Life Balance Through Interval Training

NO THANKS, I WANT TO CONTINUE READING.

Get the latest from HBR emailed to your inbox. Sign up now

You might also like

- Nutrition For The AthleteDocument11 pagesNutrition For The AthletewenghuatNo ratings yet

- Training Session - Beginner I Milestones - Holistic Strength - Reddit PDFDocument1 pageTraining Session - Beginner I Milestones - Holistic Strength - Reddit PDFGary100% (1)

- Bulking Training ProgramDocument5 pagesBulking Training ProgramLuke SergiouNo ratings yet

- The 6-Week Model Workout Plan For A Lean Body - Muscle & FitnessDocument6 pagesThe 6-Week Model Workout Plan For A Lean Body - Muscle & FitnessIMAM MD MEHEDI HASANNo ratings yet

- Nutrition For RunnersDocument6 pagesNutrition For RunnersGlo Anne GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Eating To Win: Activity, Diet and Weight ControlDocument23 pagesEating To Win: Activity, Diet and Weight ControlAbraham SolomonNo ratings yet

- Aron Straker Intuitive Eating PDFDocument53 pagesAron Straker Intuitive Eating PDFHenry BidalNo ratings yet

- Fat Loss Program: Program Latihan SET Repetisi Rest KeteranganDocument1 pageFat Loss Program: Program Latihan SET Repetisi Rest KeteranganDzul QornainNo ratings yet

- Workout Abs Bible 37 Six-Pack Secrets For Weight Loss and Ripped Abs (Workout Routines, Workout Books, Work Workout, Abs... (Harder, Felix) (Z-Library)Document132 pagesWorkout Abs Bible 37 Six-Pack Secrets For Weight Loss and Ripped Abs (Workout Routines, Workout Books, Work Workout, Abs... (Harder, Felix) (Z-Library)Fatma özgüleçNo ratings yet

- EbookmbaDocument49 pagesEbookmbaKrishna ThakurNo ratings yet

- Strength Training ExercisesDocument18 pagesStrength Training ExercisesKhalayla LagahidNo ratings yet

- Yog For WellnessDocument205 pagesYog For Wellnessgarima100% (1)

- American Fitness Magazine Fall 2017Document72 pagesAmerican Fitness Magazine Fall 2017ΑΡΙΣΤΟΤΕΛΗΣ ΓΕΩΡΓΟΠΟΥΛΟΣNo ratings yet

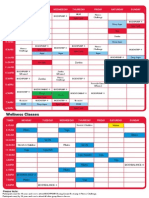

- Group Fitness Timetable Effective 1 March 2011Document2 pagesGroup Fitness Timetable Effective 1 March 2011wongfanyNo ratings yet

- Increased Physical AttractivenessDocument22 pagesIncreased Physical AttractivenessNasir SaleemNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : IntroductionDocument12 pagesJournal Homepage: - : IntroductionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Latest BackIntelligence FWD Head Exercises PDFDocument7 pagesLatest BackIntelligence FWD Head Exercises PDFmattiaNo ratings yet

- Kris Gethin Muscle Building Calendar Food and Fluid List PDFDocument1 pageKris Gethin Muscle Building Calendar Food and Fluid List PDFYash SNo ratings yet

- Lead and Motivate Your StaffDocument7 pagesLead and Motivate Your StaffNag Amrutha BhupathiNo ratings yet

- Commercial Weight Loss ProgramsDocument13 pagesCommercial Weight Loss ProgramsJenny Rivera100% (1)

- PDF - FBX 15workout Plans PDFDocument81 pagesPDF - FBX 15workout Plans PDFLazar Stanimirovic67% (3)

- Balance Crossways Form, Technique, and BiomechanicsDocument37 pagesBalance Crossways Form, Technique, and Biomechanicsbacharelado2010No ratings yet

- Why A Calorie Deficit Is Key To Effective Weight Loss by Steve SearleDocument8 pagesWhy A Calorie Deficit Is Key To Effective Weight Loss by Steve SearlesearlsaNo ratings yet

- OvertrainingDocument5 pagesOvertrainingCésar Morales García100% (1)

- Pre-Workout Your Complete Guide 2Document1 pagePre-Workout Your Complete Guide 2Yap Kai Hoong100% (1)

- Fitness and Wellness 13th Edition PDFDocument13 pagesFitness and Wellness 13th Edition PDFbiriga60233100% (1)

- Built LeanDocument4 pagesBuilt LeanKostaPemacNo ratings yet

- Lunch and Learn: Corporate Wellness ProgramDocument8 pagesLunch and Learn: Corporate Wellness ProgramLavinia FratilaNo ratings yet

- Guide To Lean BulkDocument4 pagesGuide To Lean Bulkamirreza jmNo ratings yet

- Body Making Food - Google SearchDocument1 pageBody Making Food - Google SearchmohanmedzayanmzNo ratings yet

- 28 Day Transformation AcceleratorDocument13 pages28 Day Transformation AcceleratorSidNo ratings yet

- Fit 101 Guide PDFDocument18 pagesFit 101 Guide PDFThequranseekerNo ratings yet

- 100 Days of Weight Loss MaterialsDocument3 pages100 Days of Weight Loss MaterialsCeleste AbdonNo ratings yet

- Level 0: Initial Inputs: Body Weight (In LBS) : Maintenance CaloriesDocument14 pagesLevel 0: Initial Inputs: Body Weight (In LBS) : Maintenance Calorieslucas AyalaNo ratings yet

- Andrew Gym Power Fat Blasting ProgramDocument34 pagesAndrew Gym Power Fat Blasting ProgramAndrew EscagedaNo ratings yet

- What Goes Viral On Social MediaDocument46 pagesWhat Goes Viral On Social MediaPrabhu RamNo ratings yet

- Two Brain MetricsDocument27 pagesTwo Brain MetricsJay MikeNo ratings yet

- Ebook Completo Sobre CoachingDocument22 pagesEbook Completo Sobre CoachingJúlio GuerreroNo ratings yet

- ISSA Client Intake FormsDocument17 pagesISSA Client Intake FormsJason WilkinsNo ratings yet

- Paleolithic HIIT Singular Phase 2Document9 pagesPaleolithic HIIT Singular Phase 2Ivan AldinataNo ratings yet

- Coaching.: Home: CorrespondenceDocument19 pagesCoaching.: Home: CorrespondenceĐạt NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Jeunesse Zen Project 8 Thrive FoodDocument20 pagesJeunesse Zen Project 8 Thrive FoodZen Project 8No ratings yet

- Nutrition !Document18 pagesNutrition !MercédeszNo ratings yet

- Double Your Muscle Building ResultsDocument19 pagesDouble Your Muscle Building ResultsMiguel BarbosaNo ratings yet

- Postpartum ExDocument2 pagesPostpartum ExYang Yong YongNo ratings yet

- Fast Track Study Guide - Personal TrainingDocument47 pagesFast Track Study Guide - Personal TrainingEMANUEL ANTONIO CAMACHO SILVANo ratings yet

- Fitness and Wellness 1. What Is P.E ?: Cardiovascular Exercises or AerobicsDocument2 pagesFitness and Wellness 1. What Is P.E ?: Cardiovascular Exercises or AerobicsRecca Mae TiaoNo ratings yet

- CS4L SummaryDocument2 pagesCS4L SummarySpeed Skating Canada - Patinage de vitesse CanadaNo ratings yet

- Work Life BalanceDocument15 pagesWork Life BalanceHarshit AgarwalNo ratings yet

- 327616blood Flow Restriction (BFR) Training - Sports Medicine Center ...Document2 pages327616blood Flow Restriction (BFR) Training - Sports Medicine Center ...tyrelawlknNo ratings yet

- Exercise Routine For Weight Loss KenyaDocument2 pagesExercise Routine For Weight Loss Kenyasandra Chemase100% (2)

- Step by Step Weight Loss With 150 Weight Loss Tips PDFDocument65 pagesStep by Step Weight Loss With 150 Weight Loss Tips PDFhiNo ratings yet

- Training ExercisesDocument197 pagesTraining ExercisesYasir ButtNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Stress and Wellbeing at Work - BB LearnDocument23 pagesWeek 6 Stress and Wellbeing at Work - BB LearnTaimoor BaigNo ratings yet

- 2000 DFY MetricDocument4 pages2000 DFY MetricbookslolNo ratings yet

- Aerobic Basics - A Complete Guide To Stay Active And Healthy And Make Fitness FunFrom EverandAerobic Basics - A Complete Guide To Stay Active And Healthy And Make Fitness FunNo ratings yet

- Bodybuilding High Protein Meal Prep Cookbook: Easy, Nutritious Meals to Build Muscle, Burn Fat, and Stay LeanFrom EverandBodybuilding High Protein Meal Prep Cookbook: Easy, Nutritious Meals to Build Muscle, Burn Fat, and Stay LeanNo ratings yet

- Alpha BlueprintDocument265 pagesAlpha BlueprintDavid Herbert Lawrence89% (36)

- The Full Moon in Aries Arrives Sunday NightDocument7 pagesThe Full Moon in Aries Arrives Sunday NightslavenkaNo ratings yet

- General Psychology - PDF - Psychology - MindDocument57 pagesGeneral Psychology - PDF - Psychology - MindAishleyNo ratings yet

- MasterClass 1Document6 pagesMasterClass 1ryuvaNo ratings yet

- Ford Case Study: Jaipuria Institute of Management LucknowDocument2 pagesFord Case Study: Jaipuria Institute of Management LucknowHoàng ThànhNo ratings yet

- 3 - Q1 21st CenturyDocument14 pages3 - Q1 21st CenturyLily Mae De ChavezNo ratings yet

- Sandeep NumerologyDocument7 pagesSandeep NumerologyDhawan SandeepNo ratings yet

- Chan Handbook Free SampleDocument36 pagesChan Handbook Free SampleSanity FairNo ratings yet

- Personal Development Unit Test - AnswerDocument2 pagesPersonal Development Unit Test - AnswerPamPam Gajes100% (5)

- The Great Little Book of Afformations PDFDocument149 pagesThe Great Little Book of Afformations PDFmanjunathganguly77127594% (47)

- Coaching Framework For Thinking Before ActingDocument3 pagesCoaching Framework For Thinking Before ActingJosé Henríquez GalánNo ratings yet

- Tactical Periodization Training The Brain To Make Quick Decisions PDFDocument4 pagesTactical Periodization Training The Brain To Make Quick Decisions PDFHung100% (1)

- Must Music Education Have An Aim - HowardDocument16 pagesMust Music Education Have An Aim - HowardMr. BarryNo ratings yet

- Reality Creationcheat Sheet 1Document17 pagesReality Creationcheat Sheet 1Ahmed Loeb100% (13)

- CharacterDocument3 pagesCharactersgw67No ratings yet

- Carl Roger S Congruence As An Organismic Not A Freudian ConceptDocument21 pagesCarl Roger S Congruence As An Organismic Not A Freudian ConceptYuri De Nóbrega Sales100% (1)

- ES Book3Document67 pagesES Book3Anh Việt Lê100% (3)

- Pde 506Document6 pagesPde 506PemarathanaHapathgamuwaNo ratings yet

- Article - Motivation vs. Discipline PDFDocument10 pagesArticle - Motivation vs. Discipline PDFMinuteman73No ratings yet

- Occult Debunks Globe Mind UnveiledDocument10 pagesOccult Debunks Globe Mind Unveiledtavdeash238No ratings yet

- 36 - Meditation LetterDocument13 pages36 - Meditation LetterZamara BennettNo ratings yet

- Ebook How To Have A Lucid Dream PDFDocument3 pagesEbook How To Have A Lucid Dream PDFVuk MicunovicNo ratings yet

- Principalities Power Andspiritual WickednessDocument2 pagesPrincipalities Power Andspiritual WickednessG. ALEX DEE JOE100% (1)

- The Character of Creativity: The Vedic Perspective: Maharaj RainaDocument16 pagesThe Character of Creativity: The Vedic Perspective: Maharaj RainaWilliam Eduardo Avila Jiménez100% (1)

- Works of Pier Luigi NerviDocument162 pagesWorks of Pier Luigi Nervialejoeling100% (3)

- The Silent Storm: Poems by DR - Sandhya TiwariDocument14 pagesThe Silent Storm: Poems by DR - Sandhya TiwariSandhya TiwariNo ratings yet

- 21 Ways To Stay in Love ForeverDocument31 pages21 Ways To Stay in Love Foreverlambdacore_12100% (1)

- The Way of Sanchin Kata The Application of PowerDocument220 pagesThe Way of Sanchin Kata The Application of PowerAndy100% (6)

- Osho MeditationDocument4 pagesOsho MeditationRam SidhNo ratings yet

- Mind Your MindDocument37 pagesMind Your MindVilma Zubinaitė100% (5)