Catalyst Issue 1: March 2013

Catalyst Issue 1: March 2013

Uploaded by

LSE SU Think TankCopyright:

Available Formats

Catalyst Issue 1: March 2013

Catalyst Issue 1: March 2013

Uploaded by

LSE SU Think TankCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Catalyst Issue 1: March 2013

Catalyst Issue 1: March 2013

Uploaded by

LSE SU Think TankCopyright:

Available Formats

Issue 1 March 2013

Copyright Notice

Permitted Uses; Restrictions on Use

Materials available in this publication are protected by copyright law and have been published by the London School of Economics LSE SU Think Tank (or LSE SU Think Tank Society), is a member of the London School of Economics (LSE) Student Union.

Copyright 2013 LSE SU Think Tank. All rights reserved.

Any unauthorised reprint or use of this material is strictly prohibited. No part of the materials including graphics or logos, available in this publication may be copied, photocopied, reproduced, translated or reduced to any electronic medium or machine-readable form, in whole or in part, without specific permission.

You may request permission to use the copyright materials in this journal, please contact our editorial team by email at catalyst@lsethinktank.com. Distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited unless prior agreed upon with the LSE SU Think Tank committee members.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in the articles that form this publication are those of their respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the LSE SU Think Tank as an organisation. The authors of the articles retain full rights of their writings, and are free to disseminate them as they see fit, including but not limited to reproductions in print and websites. The LSE SU Think Tank does not endorse, warrant, or otherwise take responsibility for the contents of the articles.

Issue 1 March 2013

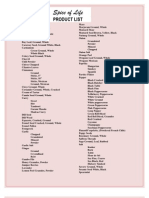

TABLE OF CONTENTS

About LSE SU Think Tank Presidents Note Editors Note ECONOMICS AND FINANCE Myanmars New Foreign Investment Law May Derail the Countrys Stated Developmental Goals -Marie Plishka Islamic Finance: Alternative Banking and Potential Solution to Global Financial Crisis Azril Ikram Rating Agencies: The untouchables of the 21st Century Alessandro Panerai WELFARE POLICY Rethinking the Social Welfare System Designed for Migrant Workers in China --Yang Shen HEALTHCARE The Narrative Paradoxes in Indias HIV/AIDS Policy--Sudheesh Ramapurath Chemmencheri DEVELOPMENT Afghanistan, Aid and Counter Narcotic Policy--Becca Cockayne CONFLICT RESOLUTION Will Turks and Kurds Finally Make a Deal on the Kurdish Question? --Sinem Hun NATIONAL SELF-DETERMINATION Nationalist Revolts in Europe: The Quest for Catalan Independence--Elena Magri GLOBAL DEMOCRACY Converging Election Campaign Practices: How do Americanisation and Modernization help us better Understand this Process?--Siddharth Bannerjee Class Conflict in the Modern Chinese Politics: The Rise of Labour Movement as a Sign of Democracy?- Ruo Wang Sovereignty in Question: Setting the Limits --K. Ipek Miscioglu EU INSITUTIONS The Subsidiarity Principle: Finding a Space for National Parliaments within the EU DecisionMaking processes--Lim Tse Wei

3 4 5

12 19

26

31

38

46

50

56

62

67

73

Issue 1 March 2013 About LSE SU Think Tank LSE SU Think Tank was founded in November 2011 by intellectually curious and like-minded students that would like to engage in lively, informal and often heated discussions on ideas and challenges of the globalized 21st century world. The scope and range of the discussion topics is deliberately vague and broad to attract participants from cross-disciplinary backgrounds CATALYST EDITING TEAM

Elena Magri

Vikram Mathur

Dan Calder

Ruo Wang

Issue 1 March 2013

Presidents Note

Dear readers, LSE SU Think Tank has achieved a lot since the inception of the society in late 2011. As one of the founders, I can proudly say that in just one academic year we have evolved from a small society with just a handful of enthusiastic members to a society with over 150 registered members. The founding vision and principle of the society has remained intact, and in the process, we have created a great society that attracts, connects and excites like-minded students capitalizing the diversity in nationalities and disciplines that we have on campus. This journal is yet another major step forward for us as an organisation. I would like to express my sincere appreciation to everyone involved in the making of this journal especially to the committee members that have worked tirelessly to complete the journal to the standard that we aspire. I would also like to thank all the writers that have submitted their articles, even those that were not accepted by the editorial board to be in the journal. We were really impressed by the level of complexity and sophistication of articles submitted. We highly encourage you to try again in the next issue. Moving forward, I hope that committee members for the year 2013/2014 will continue to improve Catalyst further. I believe we have the capabilities to be the primary platform for students to express their policy recommendation ideas on campus. For readers, I hope that you will find this collection of articles both informative and relevant, and that it will lead you to debate about the issues discussed. Thank you for taking your time to read the collection of articles in this journal that we have prepared for you.

Sincerely, Azril Amiruddin President of LSE SU Think Tank

Issue 1 March 2013

Editors Note

It started, as do most endeavours, with a thought. The relatively new LSE SU Think Tank Society was in the midst of hosting speaker-led discussions and simulations when it stumbled upon a new project; a journal. This journal was intended to serve as a forum for students to voice their own policy analyses and recommendations. I enthusiastically jumped on board knowing that this new project of ours was going to be challenging and hopefully, rewarding. There was no prior groundwork or layout for the journal, and so I must thank all of the writers who contributed their work for inspiring the shape and direction that this journal would eventually take. I must also thank the committee members of the LSE SU Think Tank Society for tirelessly helping me to cultivate this new idea and channel this inspiration into a concrete forum. I came to the LSE believing that politics is personal. What is more personal than the thoughts and ideas that we develop, nurture and struggle with? I remember the anxiety that I felt when I first met with my dissertation supervisor. I had so many ideas, and a fear that I had nothing new to contribute to the existing global politics dialogue. In time I realized that there is no need to feel insecure about ones thoughts. I realized that this is the place where new ideas are created, where important dialogues and debates flourish. I commend our authors for leaping into this project, and for expressing their thoughts with clarity, depth and passion. The articles in this first volume come from a wide array of disciplines and contribute to the questioning of established norms. Against the backdrop of that ever-present concept of globalization arises an awareness that the world is changing, and that the ways that we conceptualize the problems we face must evolve as well. While some of our authors push for possible alternatives to traditional banking systems and instruments, there also appears to be a realization that development policies must address social issues as well. Analyses of the welfare policy in China, HIV/AIDs in India, the counter-narcotics policy in Afghanistan, the endurance of conflicts and the quest for self-determination feature in this volume. Im only here for a year, but I hope that what we have initiated will continue to grow and thrive as new challenges, and new ways of thinking about older challenges emerge. I thank you for reading these policy recommendations, and I hope that you too will be inspired to think different.

Natasha Basu LSE SU Think Tank Editor in Chief 2012-2013

Issue 1 March 2013

Economics and Finance

Issue 1 March 2013

Myanmars New Foreign Investment Law May Derail the Countrys Stated Developmental Goals p.7-11

Marie Plishka

Myanmar government officials have stated on several occasions that their top economic priorities for the country are jobs and inclusive and sustainable growth. Thus, it is surprising to see that after almost a year of debate, the new Foreign Investment Law that was signed by President Thein Sein in November 2012 could actually make it even harder for the country to achieve its stated developmental goals. This paper puts forward a set of policy recommendations that will not only allow the country to continue to reap the benefits of its natural resource endowments, but will also provide more funds to meet Myanmars social development goals. An examination of the issues concerning the Foreign Investment Law will be followed by an analysis of the possible effects that the law will have on inclusive economic growth in Myanmar. Finally, a set of policy recommendations will be presented that could not only satisfy foreign investors but also promise a better future for Myanmars citizens.

New Foreign Investment Law Myanmar started a process of political and economic reform in 2011: free and open elections were held, media censorship was relaxed, political prisoners were set free, and the country signalled that it was ready to open its borders to international trade and commerce1. A country of nearly 55 million people, it is the poorest country in Southeast Asia with a GDP per capita estimated at just $1,400 in 20122. President Thein Sein stated that the economy was his central focus in all of these reform efforts, promising to deliver monumental growth by triplicating per capita GDP in just 4 years.3 Aung San Suu Kyi called for more jobs for the restless youth population, and the President of the Mandalay Region Chamber of Commerce and Industry stated that the country was resource-rich, but what they needed was skills and technology4.

1 2

Thuzar, Moe (2012) Myanmar: No Turning Back. Southeast Asian Affairs. 203-219

Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook: Burma. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-worldfactbook/index.html (accessed 23 February 2013.)

3The

Economist, 2012, July 23. Investing in Myanmar: Triplicating http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2012/07/investing-myanmar. (Accessed 23 February 2013.)

4 The

Success.

Guardian, 2012, 1 June. Aung San Suu Kyi: treat Burma reforms with healthy skepticism: Burmese opposition leader calls for caution from international community on her first overseas visit for decades. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jun/01/aung-san-suu-kyi-burma (accessed 23 February 2013.)

Issue 1 March 2013

Then, after nearly a year under debate and after going through several revisions, President Thein Sein signed into law a more business friendly version of the Foreign Investment Law 5 . The law is a revision of the first investment law from 1988, which was considered to be highly protectionist. The new law is reported to be investor -friendly because it allows for a higher percentage of foreign ownership of ventures, extended land leases, exemptions on corporate income taxes for five years, and a guarantee against nationalization during the contract period. It also includes new labour requirements, which necessitate foreign firms to hire an increasing percentage of Myanmar nationals as the firms years in operation accumulate6. The danger with the new Foreign Investment Law is the concessions made to foreign companies that wish to operate in the extractive industries. Myanmar is a resourcerich country. Research firm IHS Global Insight stated that the country is among the worlds top five oil and gas production hot spots7. A large percentage of the foreign capital that will enter the county will go to extractive industries. This could be a blessing or a curse, depending on how the Myanmar government maintains control of the situation 8

Economic Growth, not Development Economic development is a broader concept of overall wellbeing. To quote from Pike et al.: One of the biggest myths is that in order to foster economic development, a community must accept growth. The truth is that growth must be distinguished from development: growth means to get bigger, development means to get better an increase in quality and diversity9 The Myanmar government should be focused on achieving economic development to raise the living standards of the country and to provide the citizens the opportunities to realize their full potential. Several statements by political leaders indicate that they are hopeful that the reforms will bring about economic development. However, the countrys investment policies should be examined more closely to see if development, and not just growth, would result from the reforms.

ERIA (Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia), 2012, September 28. Myanmar Accepts Development Through Foreign Direct Investment. http://www.eria.org/press_releases/FY2012/10/myanmar-expects-developmentthrough-foreign-direct-investment.html. (Accessed 23 February 2013.)

5 6Anukoonwattaka,

W., & Mikic, M., (2012) Myanmar: Opening Up to its Trade and Foreign Direct Investment Potential. Trade and Investment Division, Staff Democratic Voice of Burma, 2012, November 20. Investment, discretion and Burmas future economic development.http://www.dvb.no/analysis/investment-discretion-and-burmas-future-economic-development/24904. (Accessed 23 February 2013.)

7 8

Bissinger, Jared (2012) Foreign Investment in Myanmar: A Resource Boom but a Development Bust? Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs. 34 (1) 23-52 9 Pike, Andy, Andres Rodriguez-Pose, and John Tomaney. "What Kind of Local and Regional Development and forWhom?."RegionalStudies.41.9.2007): 1254<http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/consultation/terco/pdf/6_university/7_curds_newcastle.pdf>.

Issue 1 March 2013

Impacts of FDI After the US and other western countries imposed sanctions on Myanmar in the early eighties many multi-national companies involved in textiles and apparel were forced to leave the country. Western investors were replaced with Asian ones, and Myanmar received increasingly more foreign investment into its oil and gas sector10. It is here that one should analyse the impact that FDI has on different sectors of the economy. To quickly summarize the research of Alfaro (2003)11, one can expect that FDI into extractive industries will have a negative effect on economic growth and that FDI into manufacturing will have a positive effect on growth. The effect of FDI on economic growth comes from the nature of the industry that is receiving the investment and the contextual factors such as human capital, maturity of the financial system and institutional quality12. As Hirschman put it, The grudge against what has become known as the enclave type of development is due to this ability of primary products from mines, wells, and plantations to slip out of a country without leaving much of a trace in the rest of the economy13. Firms working in the extractive industry create less backwards and forward linkages, do not create a huge number of new jobs, and do not create positive externalities such as knowledge spill overs that can be absorbed by local firms14. Countries can take either one of two paths once natural resources become the dominant industry: they can either harness the enormous amount of money this industry produces and invest that money into the social and economic development of the county, or the country can disintegrate into corruption and rising income inequality. The passage of the new business friendly Foreign Investment Law seems to indicate that Myanmar failed to see that they are really the ones in control. Incentives alone will not bring foreign investors into Myanmar. Indeed, it is just one piece of the picture and the government must also strive to lower corruption, decrease bureaucratic red tape in operating a business, and provide a skilled work force15. Furthermore, being an oil and gas hotspot, foreign investors will come regardless of incentives. By offering incentives to foreign extraction firms, Myanmar forgoes a substantial amount of income from these business activities. Indeed, Myanmar would be able to self-finance a larger portion of their developmental plans and they would be less likely to borrow from the Asia Development Bank and the World Bank, both of whom they recently accepted loans for social development16.

10

Anukoonwattaka, W., & Mikic, M., (2012) Myanmar: Opening Up to its Trade and Foreign Direct Investment Potential. Trade and Investment Division, Staff

11 12

Alfaro, L. (2003) Foreign Direct Investment and Growth: Does the Sector Matter? Allston, MA, Harvard Business School Alfaro, L. (2003) Foreign Direct Investment and Growth: Does the Sector Matter? Allston, MA, Harvard Business School 13 Hirschman, A. (1958) the Strategy of Economic Development. Yale University Press (p.110)

14 15

Alfaro, L. (2003) Foreign Direct Investment and Growth: Does the Sector Matter? Allston, MA, Harvard Business School Moran, T.H., Graham, E.M., Blomstrom, M. (Eds). (2005) Does Foreign Direct Investment Promote Development? Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.

16

BBC News, 2013, January 28. Burma gets Asian Development http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-21226344 (accessed 23 February 2013.)

Bank

and

World

Bank

Loans.

Issue 1 March 2013

A struggle has already developed amongst the elites in Myanmar as to whether the country should grow rapidly and perhaps unevenly, with the help of the private sector and FDI, or if it should pursue a more inclusive, diversified and sustainable development path 17. The passage of the new Foreign Investment Law would seem to suggest that the decision has been made to pursue the former. Recognizing that FDI will be flooding Myanmar, political figures such as Aung Suu have asked the investors to be thoughtful in their investments and to work to benefit the people of Myanmar18. Unfortunately, this request will most likely go unheeded. Myanmar must create a diversified economy with inclusive and sustainable growth as their first priority. Focusing on quick economic growth through FDI in extractive industries will only lead to the deindustrialization of other industries (the feared Dutch disease) and will further widen the gap between the rich and the poor in Myanmar. Inclusive growth can only be achieved if the right incentives, or disincentives, are written into law. Therefore, the policy recommendation for Myanmar would be to erase the incentives for FDI into the extractive sector. Foreign investors are eager to enter the country and exploit this sector, and will likely be undeterred by a less generous tax holiday. The money the government receives from taxes in the extractive sector could then be invested in the social and economic development of the country. A country with more domestically mobilized resources means that they would be less dependent on foreign loans and assistance to accomplish their development goals. Marie Plishka MSc Development Management, 2013 M.Plishka@lse.ac.uk

17

The Economist, 2012, July 23. Investing in Myanmar: Triplicating Success. http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2012/07/investing-myanmar. (Accessed 23 February 2013.)

18

The Guardian, 2012, 1 June. Aung San Suu Kyi: treat Burma reforms with healthy skepticism: Burmese opposition leader calls for caution from international community on her first overseas visit for decades. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jun/01/aung-san-suu-kyi-burma (accessed 23 February 2013.)

10

Issue 1 March 2013

References Thuzar, Moe (2012) Myanmar: No Turning Back. Southeast Asian Affairs. 203-219. Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook: Burma. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html (accessed 23 February 2013.) The Economist, 2012, July 23. Investing in Myanmar: Triplicating Success. http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2012/07/investing-myanmar. (Accessed 23 February 2013.) The Guardian, 2012, 1 June. Aung San Suu Kyi: treat Burma reforms with healthy skepticism: Burmese opposition leader calls for caution from international community on her first overseas visit for decades. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jun/01/aung-san-suu-kyi-burma (accessed 23 February 2013.) ERIA (Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia), 2012, September 28. Myanmar Accepts Development Through Foreign Direct Investment. http://www.eria.org/press_releases/FY2012/10/myanmar-expects-developmentthrough-foreign-direct-investment.html. (Accessed 23 February 2013.) Democratic Voice of Burma, 2012, November 20. Investment, discretion and Burmas future economic development. http://www.dvb.no/analysis/investment discretion-and-burmas-future-economic-development/24904. (Accessed 23 February 2013.) Anukoonwattaka, W., & Mikic, M., (2012) Myanmar: Opening Up to its Trade and Foreign Direct Investment Potential. Trade and Investment Division, Staff Alfaro, L. (2003) Foreign Direct Investment and Growth: Does the Sector Matter? Allston, MA, Harvard Business School. Hirschman, A. (1958) the Strategy of Economic Development. Yale University Press Moran, T.H., Graham, E.M., Blomstrom, M. (Eds). (2005) Does Foreign Direct Investment Promote Development? Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics. BBC News, 2013, January 28. Burma gets Asian Development Bank and World Bank Loans. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-21226344 (accessed 23 February 2013.) Working Paper 01/12. Bangkok, Trade and Investment Division, United Nations Economics and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Bissinger, Jared (2012) Foreign Investment in Myanmar: A Resource Boom but a Development Bust? Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs. 34 (1) 23-52.

11

Issue 1 March 2013

Democratic Voice of Burma, 2013, January 17. Burma Launches Major Oil Tender. http://www.dvb.no/news/burma-launches-major-oil-tender/25823 (accessed 23 February 2013.) Pike, Andy, Andres Rodriguez-Pose, and John Tomaney. "What Kind of Local and Regional Development and for Whom?." Regional Studies. 41.9. (2007): 1253-1269. <http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/consultation/terco/pdf/6_university/7 _curds_newcastle.pdf>.

12

Issue 1 March 2013

Islamic Finance: Alternative banking and potential solution to global financial crisis? p. 13-18

Azril Amiruddin

The current global financial crisis was the effect of the western dominated banking systema system that relies on high risk instruments such as subprime lending, over leveraging, incorrect pricing of risk, shadow banking system, and predatory lending. In the aftermath of the crisis, there have been debates on the need for alternative forms of banking that are safe and ethical. Islamic banking has the potential to be a complementary entity in the global financial ecosystem.

Although the industry has been around for almost 50 years, Islamic finance remains largely misunderstood in the western world and by many, significantly underestimated. When it was initially introduced, sceptics labelled the industry as spurious and argued that it is simply an attempt to rebrand conventional banking products in a deceptive way In a nutshell, Islamic finance is a system of banking that complies with Islamic law known as Sharia law. The fundamental principles that govern Islamic banking are: collective risk and profit sharing between the stakeholders, the assurance of fairness for all parties, and transactions that are based on underlying business activity or real assets. Since the opening of the first modern commercial Islamic bank, Dubai Islamic Bank (DIB) in 1975, Islamic finance has developed from a niche service serving only Sharia-compliant Muslim clients to mass market investing and does business in a mature, sophisticated and fast growing industry with an estimated one trillion dollars in total assets. According to Ernst & Youngs World Islamic Banking Competitiveness Report 2013, the global market share for Islamic finance by the end of 2011 was worth around $1.3 trillion (800bn; 1tn), suggesting an average annual growth of 19% over the past four years (24% in 2011). In other words, it is the fastest growing segment of the modern financial market.

13

Issue 1 March 2013

Islamic banking asset growth (US$b)

Certainly market performance is a major factor behind this recent trend, but it is nave to underestimate the role of socially conscious consumers, businesses and leaders who are expecting more from the corporations (i.e. business that play a role in generating social good to the community) to this discussion. With approximately 1.62 billion Muslims in the world a ready-made or captive customer base for Islamic finance arguable already exists1. At the same time, Islamic Banking presents a clear scope for a broader appeal to non-Muslims who are seeking an alternative form of ethical, transparent and responsible banking practices. This trend supports a projected rise in values-based investing among investors, and since the Muslim population is expected to grow at twice the rate of the non-Muslim population over the next two decades2 to approximately 2.2 billion people, we can expect the growth in Islamic finance will continue to expand further in the future.

The rapid growth of Sukuk One of the major products in Islamic Finance is Sukuk. Sukuk is a financial certificate, similar to a bond in conventional finance but it complies with Sharia law. Global sukuk represents a dynamic part of the Islamic financial system that continues to grow at a remarkable pace.

1

PewResearchCenter, (2012), The Worlds Muslim: Unity and Diversity (http://www.pewforum.org/uploadedFiles/Topics/Religious_Affiliation/Muslim/the-worlds-muslims-fullreport.pdf) 2 PewResearchCenter, (2011). The future of the global Muslim population, Forum on Religion and Public Life, US

14

Issue 1 March 2013

After the largest quarterly issuance of sukuk shown in the graph below in 1Q 2012, the global sukuk market has continued its rapid growth trend on both primary and secondary market fronts.

Sukuk Outstanding Trend (US$m)

The growth of sukuk issuances in 2012 can be attributed to a number of reasons, including the declining yield to maturity (YTM) for both corporate and sovereign bond issuances in conventional financial markets, the rarity of high quality yielding fixed income instruments, and the flight of fixed income safety due to broad macroeconomic concerns emerging from US fiscal cliff and European sovereign-debt crisis. The primary sukuk market has been driven by the increasing number of funds raised by corporations, states and central banks around the world to capitalize the excess liquidity and provide for safe short to medium-term investment. Some prominent Western financial institutions that are facing tough conditions in the funding market on which they have long relied, are also turning to sukuk as alternative funding for investment. HSBCs Middle East unit became the first Western bank to issue a sukuk in May 2011 with a $500 million five year sukuk. In addition, the French bank Credit Agricole has said it is contemplating issuing an Islamic bond or creating a wider sukuk program that could lead to several issuances in the future. Moreover, France and South Korea have introduced news laws for issuing sukuk. New Islamic banks have recently opened in US, China, India, Germany and the UK. Citigroup, Standard Chartered and BNP Paribas have all taken steps to seize the growth opportunity in Islamic finance. Other than sukuk, there is also significant demand for other Islamic financial services such as insurance (takaful), joint venture (musharakah), lease (ijarah), safekeeping (wadiah) and wealth management services (amanah). Financial news agencies such as Thomson Reuters and Bloomberg have built deep transaction systems and complex financial data for customers to navigate in real time the emerging Islamic financial landscape. However, Islamic finance remains small compared to conventional finance with its hundreds of trillions dollars of market capitalization. The market in sukuk is believed to total about

15

Issue 1 March 2013

$200 billion in September 2012, roughly 1% of global bond issuance3. It is still a relatively young industry compared to the 600 years existence of the conventional banking.

Challenges moving forward The lack of consensus among Sharia scholars who sit on the board of the standard setting authorities is hampering the growth of the industry. The Islamic Financial Service Board (IFSB) based in Kuala Lumpur and Accounting and Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI), based in Bahrain are the two prominent global standard setting authorities that establish the guiding principles upon which the industry is operating. Both belong to diverging schools of thought, and this becomes problematic for standardization. In order for the product development and innovation process to be more efficient and effective standardization is crucially needed. Without standardization the industry is left exposed to Sharia arbitrage as banks, firms and consumers pick and choose for the standard or fatwa that suits their personal objectives. A lack of standardization is not the only hurdle the sector is facing. There are questions regarding the integrity of the products for an industry that is supposedly built on ethics. The past several years have exposed various weaknesses in Islamic finance. The Dubai debt crisis of 2009 showed that there is a problem with the sukuk market. Nakheel, a property developer raised funds through sukuk issuance was forced to restructure the companys debt worth $3.5 billion when they found themselves unable to repay their debt holders from the onset of the financial crisis4. Moreover, the supply of trained and experience bankers have lagged behind the increasing demand for Islamic banking expertise. This has resulted in many Sharia scholars sitting on multiple boards of approving bodies and financial institutions, thus creating a potential conflict of interest. A major misconception would be to consider this faith-founded method of banking to be idiosyncratic or out of date. Islamic banking is as sophisticated as any form of financing available today with tremendous potential for innovation and evolution of its services.

Potential solution to global financial crisis Intriguingly, Islamic banks, with their unique business models, emerged from the global financial crisis with their statement of financial position comparatively unharmed. Sharia law strictly prohibits businesses from profiting based on interest taking, usury, gambling, prostitution and speculative trading; all of which are contrary to the principles of Islamic practice. The law also propagates a certain level of protection of tangible assets from the general meltdown.

3

HSBC Amanah, (2012), Global sukuk market: The current status and growth potential

Hassan and Kholid (2011), Bankruptcy Resolution and Investor Protection in Sukuk Markets,

16

Issue 1 March 2013

Proponents of Islamic banking and the finance industry have already predicted that the industry may have a remedy and that this fast-growing industry can come forward to solve the current financial crisis affecting the world5. Although the size of the industry is still relatively small, there exists an unprecedented opportunity for the financial world to seek solutions in managing and solving financial crisis. The problem of limited expertise can be solved by establishing more academic programmes in institutions to qualify bankers interested in specializing in Islamic banking. For instance, many universities throughout the UK and elsewhere in Europe such as Aston Business School and Bangor Business School have started MBA programme for students interested in the area. On the other hand, Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA) and International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance (INCEIF) has introduced chartered professional qualification equivalent to master programme for working professionals that would like to work in the Islamic finance industry. Azril Amiruddin BSC Accounting and Finance a.i.amiruddin@lse.ac.uk

References PewResearchCenter, (2012), The Worlds Muslim: Unity and Diversity (http://www.pewforum.org/uploadedFiles/Topics/Religious_Affiliation/Muslim/theworlds-muslims-full-report.pdf) PewResearchCenter, (2011). The future of the global Muslim population, Forum on Religion and Public Life, US HSBC Amanah, (2012), Global sukuk market: The current status and growth potential Hassan and Kholid (2011), Bankruptcy Resolution and Investor Protection in Sukuk Markets, QFinance (http://www.qfinance.com/contentFiles/QF01/h0im2u72/12/0/bankruptcyresolution-and-investor-protection-in-sukuk-markets.pdf) RoulaKhalaf and Gillian Tett (2007) Backwater sector moves into global mainstream

5

Ernst

and

Young,

(2012),World

Islamic

Banking

Competitiveness

Report

2013,

(http://www.mifc.com/index.php?ch=151&pg=735&ac=818&bb=file)

17

Issue 1 March 2013

Dr Abul Hassan (2009) the global financial crisis and Islamic Banking. The Islamic Foundation, UK Sonam Garg, (2012)Sukuk and its growth across major Islamic financial markets Ernst and Young, (2012),World Islamic Banking Competitiveness Report 2013, (http://www.mifc.com/index.php?ch=151&pg=735&ac=818&bb=file)

18

Issue 1 March 2013

Rating Agencies: The untouchables of the 21st Century p. 19-24

Alessandro Panerai

Discussing rating agencies can be a tricky challenge. This category of complex actors, certainly one of the most influential in the contemporary economic panorama, tends to lurk in the shadows for months, only appearing, ex abrupto, to publish their famous and controversial rating reports1. They have become notorious for their downgrades against southern European countries, which has caused more than a few problems for their governments, and recently for Standard & US Treasury Bonds. A downgrade can lead to burdensome public debt since the interest rate a government has to grant to its investors becomes higher, and governments experience greater difficulty obtaining credit and paying back loans. This leads to entrapment into one of the so-called "death spirals" that can steer governments to bankruptcy. For many countries like Italy, that continue to experience austerity, there is no guarantee that the spread between German bonds and Italian bonds will be resolved. Another downgrade for Italy would mean that the Italian people would be poorer, and the spread would remain unchanged. Rating agencies remain powerful and controversial actors. The aim of this article is to explore why.

First of all, what is a rating agency? A credit rating agency (CRA) is a company that assigns credit ratings for issuers of certain types of debt obligations as well as debt instruments themselves. The rating is expressed with specific parameters, i.e. the letter-system created by rating agencies for their judgments, ranging from the triple A, which indicates an almost complete absence of risk (and so that the debtor is solvent), to D, which indicates Default.

Sinclair, Timothy J., The New Masters of Capital: American Bond Rating Agencies and the Politics of Creditworthiness (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005)

19

Issue 1 March 2013

You can find the complete map below: Moody's S&P Fitch Long-term Short-term Long-term Short-term Long-term Short-term Aaa AAA AAA Prime Aa1 AA+ AA+ A-1+ F1+ Aa2 AA AA High grade P-1 Aa3 AAAAA1 A+ A+ A-1 F1 A2 A A Upper medium grade A3 AAP-2 A-2 F2 Baa1 BBB+ BBB+ Baa2 BBB BBB Lower medium grade P-3 A-3 F3 Baa3 BBBBBBBa1 BB+ BB+ Non-investment grade Ba2 BB BB speculative Ba3 BBBBB B B1 B+ B+ B2 B B Highly speculative B3 BBCaa1 Not prime CCC+ Substantial risks Caa2 CCC Extremely speculative Caa3 CCCC CCC C In default with little CC prospect for recovery Ca C C DDD D / / In default

In the rating market there are more or less thirty relevant players, and among these, nine companies are considered the most reliable and thus are often preferred to the others. These nine companies are the so-called NRSRO (Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organization), and are recognized as more influential by the SEC, the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Among these nine, three are the most famous and powerful: Standard & Poor's, Moody's, and Fitch. The three together occupy 94% of market shares (Moody's and Standard & Poor's have 40% each, Fitch has 14%) and are usually cited by newspapers for their judgments3. Another important (and quite new) agency is the Chinese Dagong. Established in 1994, this agency has become famous for its downgrade of US Treasury Bonds, and for not having been recognized by the SEC, "because of the

3

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, "Credit Rating AgenciesNRSROs". ( U.S. SEC, 2008).

20

Issue 1 March 2013

commission's inability to supervise the Beijing-based agency"4. This by itself reveals the first problem in this industry: the three main agencies form a de facto oligopoly, an oligopoly curiously legitimized by a regulatory organism, the SEC, thanks to the already cited NRSRO rules. This oligopoly also happens to be situated in one of the most liberal countries in the world, and regulates the most liberalized sector: that of financial instruments. This paradox has caused a lot of criticism in the past. Many influential opinion leaders such as the ECB president Mario Draghi, have proposed a removal of the NRSRO rules, since these agencies' reports can be "catastrophically misleading" and have extremely negative impacts on the world economy5. Large corporate CRAs do not downgrade companies promptly enough. The list of their mistakes is sadly long. In November 2001, the continuous losses notwithstanding, Standard & Poor's gave Enron a BBB rating. The third of December of the same year the company went bankrupt. Even worse (because of the impact this decision had on every one of us): the 18th of July 2008 Standard & Poor's, Moody's and Fitch gave Lehman Brothers an A, A2, A+ rating respectively. The following 15th of September the company went bankrupt. It was the beginning of the financial crisis. The CDOs on subprime mortgages themselves were rated AAA before the explosion of the crisis. Simple oversights? Innocent mistakes? Or is there something else? Companies which receive on average $300,000-$500,000 per rating should be a little more careful with their evaluations. Since the top three CRAs often use private information to assess their judgments, the bond between them and private companies is pretty opaque, and leaves space to undue influence or misjudge. One could also argue that since private firms pay high amounts of money to obtain a rating of a debt issuer, this might also give additional money to rating agencies to "buy" a higher rating. In some cases (such as that of the insurance company Hannover Re) the newspapers have openly talked about "blackmailing" tactics from CRAs, asking for more money and threating to downgrade if the company did not pay. Hanover Re is said to have lost $175 million because of this6. A downgrade can easily cause a countrys economy or a company to head towards a downward spiral culminating into bankruptcy when it cannot repay in full its debts when requested. Due to the fact that theoretically no one would gain from a countrys bankruptcy (first and foremost, its citizens), the question spontaneously arises as to why rating agencies should downgrade them? Is it just for "financial honesty" (a term which sounds absurd in itself)? Or is it because this can lead to substantial political submission of a country, a continuous dependence on foreign aid and, as I claim the creation of a "discount" whose products are national companies and their shares? At the very least, rating agencies could use more discretion when making forming their judgments.

4

Society for the advancement of Credit Rating, Dagong, the new Chinese bad guy or a fair player? ,,. Available at: http://www.another-rating.org/2012/03/dagong-new-bad-chinese-or-just.html 5 Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose: Only Mario Draghi's ECB can avert global calamity before the year is out. A vailable at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/comment/ambroseevans_pritchard/9436348/Only-Mario-DraghisECB-can-avert-global-calamity-before-the-year-is-out.html 6 Grigolon. Gloria. "Quando il giudice viene giudicato". Available at: http://www.echeion.it/economia/quandoil-giudice-viene-giudicato/

21

Issue 1 March 2013

The complexities of the rating agencies and their relationship to companies and countries become more fascinating when considering who owns and controls the main CRAs: Moodys, founded in 1909, is present in 26 countries, has more or less 4500 employees, and is based in New York7. Its owners are: Berkshire Hathaway Inc., the investment fund owned by the Omaha oracle Warren Buffet, with the 12, 47% of shares. Capital World Investors: 12,38% Price (T.Rowe) Associates Inc. : 5,95% BlackRock Fund Advisors : 3,68% State Street Global Advisors : 3, 24%

Standard & Poors, created in 1860, is based in New York as well, employs 10000 people and has offices in 23 countries8 .It is 100% owned by McGraw-Hill, a famous American company whose main areas of business are publishing, education and financial services. Who owns McGraw-Hill?9 Capital World Investors: 12,31% State Street Corporation: 4,34% Vanguard Group Inc.: 4,17% Black Rock Fund Advisors: 4,17% Oppenheimer Funds Inc.: 4,04%

All of the actors outlined above in the ownership structures are investment, pension or hedge funds companies Again, the question spontaneously arises: how fair is it that these funds might theoretically (or certainly.) know in advance the behaviour of a certain debt instruments, due to the fact that they own companies that can influence the interest rates (and consequently prices) of these instruments? It is s pretty easy for Mr. Buffet to be an oracle if he can directly influence the plausibility of his predictions. If we continue exploring further the ownership structures of the funds themselves we discover that: the main shareholders of State Street Corporation (present in both the rating agencies analysed above) are: Barclays Plc; Citigroup Inc.; Vanguard Group Inc., i.e. some of the major investment banks and another fund. The same is the case with BlackRock. Here we have: Bank of America Merrill Lynch; P.N.C Financial Services & co. etc. An example of the possible implications of this is the following: an investment bank, lets say Goldman Sachs, goes to Standard & Poors two months before it will publish its periodical report and says: Dear Standard & Poors, why dont we make the following deal: in your next report you will downgrade company x. In the meantime I create derivatives, ex. futures, on

7

White, Lawrence J. (Spring 2010). "The Credit Rating Agencies". Journal of Economic Perspectives (American Economic Association) 24 (2): 211226

8

Blumenthal, Richard (May 5, 2009). "Three Credit Rating Agencies Hold Too Much of the Power". Juneau Empire - Alaska's Capital City Online Newspaper. Retrieved August 7, 2011. 9 Standard & Poor's "S&P | About S&P | Americas - Key Statistics".. Retrieved August 7, 2011

22

Issue 1 March 2013

company xs shares, and I sell as many as I can to the market. Knowing that you will downgrade it, I will bet their price to go down and sell as many as I can at a certain price, so as to make profit on each of them. At the very end, I will give you the 10% of my earnings. What do you think?. Easy money, indeed. The situation with Fitch is just a little bit different. It is based in New York like the other two, but it is half French half American 10. Here are the two owners: Fimalac (France): 60% Hearst Corporation: 40%

Fimalacs president is Mr. Marc Ladreit de Lacharriere, one of the wealthiest people in France, ex-member of the board of LOreal, Air France and France Telecom, actual member of the boards of Renault and Casino, and consultant for the Bank of France. For those fans of conspiracy, he is also the President of the French section of the Bilderberg Group. To conclude, I hope I have demonstrated that the rating sector is full of shadows. Rating agencies, at minimum, are a risk to be criticized for collusion. It is not clear how influential their owners are and what these companies are able to do at an unofficial level. Moreover, the US Federal Law currently blocks every amendment of the sectors structure. Here lies the sad truth: rating agencies are the untouchables of 21st century.

Alessandro Panerai MSc Global Politics 2013 paneraialessandro@hotmail.it

10

FIMALAC, Group, Fitch. "2011 Fiscal" (in English).. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

23

Issue 1 March 2013

References: Blumenthal, Richard (May 5, 2009). "Three Credit Rating Agencies Hold Too Much of the Power". Juneau Empire - Alaska's Capital City Online Newspaper. Retrieved August 7, 2011. Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose: Only Mario Draghi's ECB can avert global calamity before the year is out. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/comment/ambroseevans_pritchard/9436348/OnlyMario-Draghis-ECB-can-avert-global-calamity-before-the-year-is-out.html FIMALAC, Group, Fitch. "2011 Fiscal" (in English).. Retrieved 26 March 2012. Grigolon. Gloria. "Quando il giudice viene giudicato". http://www.echeion.it/economia/quando-il-giudice-viene-giudicato/ Available at:

Panerai, Alessandro, Speciale agenzie di rating: che cosa sono. Available at: http://www.echeion.it/economia/speciale-agenzie-di-rating-che-cosa-sono/ Society for the advancement of Credit Rating, Dagong, the new Chinese bad guy or a fair player? ,,. Available at: http://www.another-rating.org/2012/03/dagong-new-bad-chineseor-just.html Sinclair, Timothy J., The New Masters of Capital: American Bond Rating Agencies and the Politics of Creditworthiness (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005). Standard & Poor's "S&P | About S&P | Americas - Key Statistics".. Retrieved August 7, 2011 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, "Credit Rating AgenciesNRSROs". ( U.S. SEC, 2008). White, Lawrence J. (Spring 2010). "The Credit Rating Agencies". Journal of Economic Perspectives (American Economic Association) 24 (2): 211226

24

Issue 1 March 2013

Welfare Policy

25

Issue 1 March 2013

Rethinking the Social Welfare System Designed for Migrant Workers in China

p.26-32

Yang Shen

China has experienced very strong economic growth in the last three decades, leading to rising prosperity and declining poverty. At the same time, this rapid economic growth has paralleled rising inequality, both socially and geographically. This, in turn, has led to high levels of internal migration as people move from the relatively low-income rural regions to the booming cities and industrial regions.

Statistics show that in 2009 more than 145.33 million migrant workers moved away from their homes in order to make a living in China1. The imbalance in development between the western and eastern parts of the country, as well as between the rural and urban areas, is one of the primary reasons rural residents become migrant workers. These rural migrants become the disadvantaged citizens in cities due to the housing system, the low wages, the unpleasant living conditions, the overtime work and the scarce social welfare. In order to explore the experiences of peasant migrant workers in the service sectors, I have done six months of fieldwork in Shanghai. Based on interviews with government officials, academic experts, employees and restaurant managers, I focus on documenting the implications of the attitudes of different stakeholders towards the changing social policy on the social benefits for migrant workers. In particular, this paper concentrates on reactions to this policy at the local governmental level, institutional level, and employee level. These stakeholders have different concerns on this policy based on their own particular standpoint. I argue that migrant workers cannot fully benefit from the policy without direct advocacy from the government to grassroots migrant groups, and without a more transferrable social welfare system across the nation as a whole. In the following sections, this paper first briefly introduces hukou system as well as the social welfare system for migrant workers; then it addresses how different stakeholders view this policy and how their attitudes are associated with their roles. In the last section, I provide recommendations for the Chinese government.

Hukou system and social welfare system for migrant workers The policy of tightening and relaxing the hukou system (household registration system) reflects the state control of labour in order to meet its own political and economic pursuits. As a consequence, it leads to the fluctuation of migration. Hukou system refers to the household registration system in China that categorizes citizens as either urban or rural, and it requires every Chinese citizen to be recorded with the registration authority at birth. The

1

NBS.

(2010).

Report

on

migrant

workers

in

2009

(in

Chinese).

(http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjfx/fxbg/t20100319_402628281.htm)

26

Issue 1 March 2013

earliest hukou system was adopted in 19582. The parents hukou rather than the childs birthplace determines an individuals hukou. Pun argues that the system is designed to prevent unplanned urbanization and overcrowding3. Solinger claims that citizenship benefits such as health insurance, pensions and unemployment compensation were tied to one's hukou, which for a long time were exclusively associated with urban citizens 3. However, we must recognize the changing nature of policies and situate the discussion of the hukou system in different time periods. Hukou reform is one crucial aspect that reflects the ever-changing policies in China. More recent policy changes indicate the governments desire to create a more harmonious society while maintaining economic prosperity. According to the new Social Insurance Law published in October 2010 in China, the social benefits, once attached to ones hukou of a fixed area, can now be transferred from one place to another from July, 20114. In the case of Shanghai, migrants social insurances are now integrated in the insurance system in Shanghai. Non-Shanghai urban hukou holders can enjoy pensions, medical insurance, injury insurance, maternity insurance and unemployment insurance as well. After retirement, they can enjoy a Shanghai standard pension by paying a certain proportion of fees for 15 years in Shanghai. However, nonShanghai rural hukou holders are only entitled to the first three insurances that urban hukou holders enjoy5. The social benefits, which were divided into Shanghai and nonShanghai hukou, have now shifted into urban and non-urban hukou. Owing to the recognition of the need for migrant labour, and the calls for changing the system, the hukou system is less rigid than it was in the past but it is still a source of discrimination. Promisingly, according to the municipal government, non-Shanghai rural hukou holders will be entitled to five benefits within four years. The central government set up five years of buffering time for Shanghai, from July 2011 for several reasons. First, it is not possible to implement the policy all at once because by adding two more social benefits, the cost increases rapidly. For instance, in the restaurant I worked in, migrant workers are expected to pay 280 yuan (28 pounds) per month instead of the current 180 yuan (18 pounds) if they enjoy five benefits. To illustrate this, these extra social benefits for workers means that the restaurant chain owner who has 14 branches in Shanghai and employs more than 2000 employees has to spend an additional 1.6 million yuan (160,000 pounds) per month on labour, which is a huge expenditure especially against the backdrop of soaring commodity prices. Whilst profit would decline, the cost of food and labour would rise.

2 3

Li, B. (2004). Urban social exclusion in transitional China. CASEPaper, 82 Pun, N. (2007). Gendering the dormitory labor system: production, reproduction, and migrant labor in South China. Feminist Economics, 13(3-4), p. 256. doi:Doi 10.1080/1354570070143946

3

Solinger, D. J. (1999). Contesting citizenship in urban China: peasant migrants, the state, and the logic of the market. Berkeley: University of California Press.

4

National Peoples Congress. (2010). Social Insurance Law (http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/xinwen/2010-10/28/content_1602435.htm)

of

PRC

(in

Chinese).

Retrieved

from

Shanghai Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau. (2011). Policy Q&A on employees from outside for participation in social insurance in Shanghai (in Chinese).(http://www.12333sh.gov.cn/200912333/2009bmfw/zcjd/201106/t20110628_1131177.shtml)

27

Issue 1 March 2013

Other reasons have to do with the transferability of the social welfare system. Neither the hukou system nor the social welfare system have a nationwide synchronised network, which renders information sharing impossible, enhancing the difficulty in transferring social benefits. Furthermore, different areas have different social benefits packages. For example, it is compulsory to pay the fees for all the social benefits together in Shanghai, whereas in some provinces one can choose which benefits to pay for, which complicates the social welfare system as the different governments have to negotiate the linkage problem.

Perspectives from different stakeholders I have interviewed two government officials, both of whom make the point that the main reason for reforming the social benefits of migrant workers is to reduce the social differentiation. An official of Shanghai Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau reiterates that the purpose for transforming the policy is to ensure the wellbeing of migrant workers, to decrease the gap between urban and rural residents, and to achieve social equality. When I expressed to the officials my concern of some top-down policies that may not effectively reach the bottom, they pointed out that the government has made great efforts to provide information and free services to migrant workers via newspapers, television, and online resources. They argue that migrants should take the initiative to understand policies that closely related to them and make use of these services provided. At the employers level, the restaurant chain owner has been planning to apply some changes to this restaurant, including a) limiting the labour quota, cutting from 68 to 48 for table servers. Ironically, this is easily achieved. Due to the scarcity of labour, it has been impossible to recruit enough people for two years; and b) the restaurant recruits part time table servers more frequently than ever. By recruiting a large number of part time workers from rural areas, the restaurant does not need to pay social benefits for them, which lowers the wage bill. 95% of the restaurant workers are from rural China. At the employees level, for many of my colleagues, they have already registered for New Farmers Insurance in rural areas. The compulsory social benefits tied up with work in Shanghai seem repetitive and unnecessary to them. There are two typical perspectives of my informants. Some of them are unwilling to pay for the social benefits, although they are forced to do so. They care more about whether they can take out the money once they leave Shanghai than whether they can obtain three or five kinds of social benefits. One of the interviewees quit his job in 2011 when the government started to charge fees for the social benefits from both employees and employers on a monthly basis (but he re-joined the restaurant in 2012). For the others, they think that social benefits are good for their future but they are confused about how to transfer the benefits or how to withdraw the money once they quit their job and move away. Many of my informants have no idea about the transferability of the social benefits. Being poorly educated and working 60 hours a week, they simply do not have the ability and time to access to the information provided by the government.

28

Issue 1 March 2013

The social welfare system is not unified or synchronised nationwide. One of the greatest challenges is to build a nationwide welfare system so that the social benefits are more transferrable. According to the officials, the city was intending to create a more inclusive environment for migrant workers. However, the migrant workers I interviewed did not appreciate the government's efforts. How to allow migrant workers to benefit the most from this new policy, and how to make policies that meet their real needs are issues that need to be addressed by the government. I would offer the following advice. First, with regards to the accessibility of the policy to migrant workers, community mobilisation may be a good way. As far as I know, almost every district in Shanghai arranges the social workers dealing with migrant issues. Extending their responsibilities to organise lectures and workshops in migrants residential places may be an effective way to disseminate the relevant social policies. Apart from residential areas, social workers can target industries such as catering and factories that are concentrated with migrant workers. Second, a series of policies should work together to contribute to the wellbeing of migrant workers. For example, access affordable housing and education are two primary concerns of migrant workers. Establishing a more inclusive social welfare system alone cannot significantly improve the living conditions of migrant workers in urban areas. Situated in their particular context, different stakeholders the government, employers and employees - have different concerns. An outcome will be reached through negotiation and conflict. Yang Shen PhD candidate in Gender Studies shenyang0118@gmail.com References NBS. (2010). Report on migrant workers in 2009 (http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjfx/fxbg/t20100319_402628281.htm) Li, B. (2004). Urban social exclusion in transitional China. CASEPaper, 82. Pun, N. (2007). Gendering the dormitory labor system: production, reproduction, and migrant labor in South China. Feminist Economics, 13(3-4), 239258. doi:Doi 10.1080/13545700701439465 Solinger, D. J. (1999). Contesting citizenship in urban China: peasant migrants, the state, and the logic of the market. Berkeley: University of California Press. National Peoples Congress. (2010). Social Insurance Law of PRC (in Chinese). Retrieved from (http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/xinwen/2010-10/28/content_1602435.htm) Shanghai Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau. (2011). Policy Q&A on employees from outside for participation in social insurance in Shanghai (in Chinese).(http://www.12333sh.gov.cn/200912333/2009bmfw/zcjd/201106/t20110628 _1131177.shtml)

29

(in

Chinese).

Issue 1 March 2013

Healthcare

30

Issue 1 March 2013

The Narrative Paradoxes in Indias HIV/AIDS Policy p.31-36

Sudheesh Ramapurath Chemmencheri

India has the third largest number of HIV/AIDS infected people, after South Africa and Nigeria. There are 2.39 million carriers in India, of which 39% are women and 3.5% are children. Through the efforts of the National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) and a host of aid-dependent NGOs, the infected population has decreased by 56% 1. These partnerships have resulted in multiple streams of policy transfer coupled with the importation of a rich vocabulary of HIV/AIDS combat. This paper explores the narrative framings of Indias HIV/AIDS policy through the prism of policy transfer and highlights three paradoxes that the discourse poses before the policy-maker. I will conclude by recommending an acknowledgment of these paradoxes and exploration of compensatory measures.

Teaching and Learning: the Politics of Policy Diffusion The policy transfer literature has thoroughly tracked the various transfer processes operating today, especially the diffusion of policy in a global information society2. Such processes could either be voluntary, wherein one country draws lessons from the experiences of another, or coercive, wherein the policy transfer occurs as a result of necessity and under pressure. The high prevalence and need for specialised expertise in an issue like HIV/AIDS increases the chance of a country being coerced to adopt the donors perspective and policies. Such transfers are indirect, as Dolowtiz and Marsh point out, as against cases where there is a direct coercion to adopt policies. Also, the policy transfer process can either act like an independent variable that determines the kind of policies that are adopted, or in other words, the means determine the goals. Or it could act as a dependent variable that is chosen by a country according to its policy-objectives, i.e. the goals determine the means. A quick survey of Indias HIV/AIDS policy reveals that we find a mixture of both scenarios; the Millennium Development Goal 6, which calls for halting the spread of HIV infection by 2015 and providing universal access to HIV/AIDS treatment by 2010, has provided the basic framework for HIV/AIDS combat in India. At the same time, governmental and non-governmental organisations have adopted the vocabulary of the donor agencies. Along the same lines, Jensen3 points out that policy transfers can be characterised as either constructivism or social learning. While the former involves the domination of an external party providing the policy ideas, the second involves drawing lessons and inspiration from the external party. For instance, although the government of India has largely been

1

NACO. (2012). Annual Report 2011-2012. New Delhi: National Aids Control Organisation. (http://www.nacoonline.org/upload/Publication/Annual%20Report/NACO_AR_Eng%202011-12.pdf ) 2 Dolowitz, David and David Marsh. (1996). Who Learns from Whom: a Review of the Policy Transfer Literature. Political Studies XLIV, 343-357

3

Jensen, Jane. (2010). Diffusing Ideas for After Neoliberalism: The Social Investment Perspective in Europe and Latin America. Global Social Policy 10 (59), 59-84

31

Issue 1 March 2013

ambivalent towards the decriminalisation of homosexuality, its constituent, the Ministry of Health, has been a supporter of the demand for decriminalisation citing how criminalisation impedes access of the LGBT community to treatment. Although it is difficult to find causal connections, it is interesting to note that the World Bank, which provided around $180 million to Phase II of the Ministrys AIDS efforts, has advocated decriminalisation as part of its HIV/AIDS combat strategies4, and similar lessons have been proffered by the experience of South Africa. The former could be seen as an instance of constructivism whiles the latter as social learning. Clearly, instances of policy transfer involve carriers in many cases, such as international financial institutions, aid agencies and international NGOs that facilitate the process of policy transfer. For example, the Global Business Coalition, an association of major corporates, many of which have a significant presence in India, runs an HIV/AIDS mission wherein it allows the transfer of prevention lessons from communities in one country location to another5. Avahan, the Indian AIDS control chapter of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which has promised $338 million to the country, expressly seeks to disseminate lessons learnt from one work site to another6.

Narrative Framing and Paradoxes The most conspicuous example of information transfer is reflected in the narrative framing of the HIV/AIDS policy. Three such issues and the paradoxes that they open up are delineated here: Identity The identity of the countrys HIV/AIDS policy has been framed closely following the cognitive frames used by international organisations. Thus, HIV/AIDS Surveillance is a major responsibility identified for governments that involves producing accurate data on the classified groups of Men-Having-Sex-with-Men (MSM), Injecting Drug Users, Female Sex Workers and Bridge Population like single male migrants. This lexicon is visible in the work of the National AIDS Control Organisation and across the agencies like the World Bank, UNDP and UNAIDS (compare, for instance, NACO 2012, World Bank 2011, UNDP 2011, UNAIDS 2012). The surveillance strategy hints at the problems involved in monitoring the spread of HIV/AIDS, particularly among the high-risk-groups listed above whose activity is suspected to be largely underground. The second effort to give the countrys HIV/AIDS policy a defining character is seen in the efforts to mainstream the efforts. This effort was

4

World Bank. (2012). Charting a Programmatic Road-Map for Sexual Minority Groups in India. Report No. 55, South Asia Human Development Sector Discussion Paper Series. (http://ilga.org/ilga/static/uploads/files/2012/8/4/04232441.pdf ) 5 GBC Health. (2011). Who We Are and How We Work. (http://www.gbchealth.org/our-coalition/who-we-arehow-we-work/ )

6

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. (2009). Avahan (http://www.gatesfoundation.org/avahan/Documents/Avahan_FactSheet.pdf )

Fact

Sheet.

32

Issue 1 March 2013

spearheaded by the UNAIDS owing to its associational character having 8 co-sponsors including the World Bank and UNDP. Noting that HIV/AIDS is not just a health issue, NACO adopted the integrated, inclusive and multi-sectorial approach 7. These processes of idea diffusion open up a paradoxical space where it becomes difficult to explicate whether the policy process has been voluntary or coercive and if coercive, whether direct or indirect. The NGOs and the state have largely adopted the strategy of making use of all available opportunities to procure funds and in the process adopted the donors cognitive frames of surveillance and mainstreaming. Crisis The HIV/AIDS epidemic is treated in most policy documents as a crisis or emergency. The thrust on making treatment available to the largest number of people without taking into account the auxiliary aspects of the infected persons lives has been persistent in the policies. Targeted intervention that centres on a set of identified target groups such as the MSM, intravenous/injected drug users and sex workers, and plans the entire policy based on targets is a defining feature of NACOs policy. Seckinelgin8 notes the problems associated with this vertical policy intervention, pointing out that such a strategy focuses on goalachievement and success, and ignores the actual impact on peoples lives in terms of developing their capabilities including income security. The paradox is exposed when the policy-maker is thrown into a dilemma of choosing between the dominant discourse of vertical intervention and capability approach. While the former brings an extensive stock of tools, methodologies and money to the states disposal, and insinuates a sense of ur gency in the implementation process, the latter could appear time-consuming, although more egalitarian. Identity-Crises The medicalised discourse of HIV/AIDS policy has constructed new workable identity categories that have subsumed a spectrum of vernacular sexual identities. The category of men having sex with men emerged as a generalised identity in the terminology of the Centres for Disease Control, that manages the U.S. Presidents Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and rolls out the five-year period funding of $150 million promised to the third phase of NACOs efforts. This categorisation has since become universal in HIV/AIDS prevention efforts. While the vernacular lexicon is replete with words such as hijra, kothi, panthi etc. to refer to the transgender, gay and men seeking male sex workers (the third mostly pejorative) respectively, these have been subsumed under the homogenizing term MSM. The NGOs working on HIV/AIDS, including those who have been at the forefront of demanding gay rights and decriminalisation of homosexuality such as the Humsafar Trust and Naz Foundation, have adopted this terminology. Reddys9 ethnographic work in the city

7

NACO. (2007). Mainstreaming and Partnerships. (http://www.nacoonline.org/NACO/Parterships/ )

Seckinelgin, Hakan. (2012). The Global Governance of Success in HIV/AIDS Policy: Emergency Action, Everyday Lives and Sens Capabilities. Health and Place 18, 453-460 9 Reddy, Gayatri. (2005). Geographies of Contagion: Hijras, Kothis and the Politics of Sexual Marginality in Hyderabad. Anthropology and Medicine 12 (3), 255 -270

33

Issue 1 March 2013

of Hyderabad brings out how power difference operates within the local moral economy of the sexual minorities; the sexual health clinics mostly operate for the gay men with consultations for transgenders once in a while. The transgender community, meanwhile, sees the gay men and men seeking male sex workers as the main perpetrators of the spread of HIV. Reddy draws attention to these pathologies of power and suggests that this could be one possible reason for the marginalisation of hijras within the MSM category and hence the ineffectiveness of the prevention programmes targeted at this community. The paradox before the policy-maker then is whether to go beyond the MSM categories and adopt the vernacular identities or retain the medicalised label of MSM understanding that it has helped circumvent the stigmas associated with transgenders and homosexuals in the mainstream community while rolling out prevention programmes.

Reframe the policy narrative from a constructivist perspective to a social learning perspective: the policy-makers should tap the rich experience already built in HIV/AIDS combat to revise the current policy by learning from its own and other countries lessons and move away from a donor-imposed language, especially with respect to the narrative frames used such as MSM, crisis etc. Translate the international policy discourse to the local context: this involves moving away from a surveillance strategy to a rights framework wherein the HIV/AIDS infected people are not approached as mere target population but as citizens with a right to health. This revision would help remove the stigma attached to the HIV positive people and bring more of them forward to access treatment, thereby boosting the success rate of HIV/AIDS combat. Move from vertical policy intervention towards the capability approach: The existing counselling centres should be strengthened, made more approachable and welcoming and also serve to build a community of people living with HIV/AIDS. In the next step, the feedback given by the HIV/AIDS infected people on the impact of treatment or prevention measures on enhancing capabilities in their lives should be used to rework policy priorities and strategies. Integrate vernacular identities in the policy discourse: this is important to understand the local moral economies of the stakeholder community as demonstrated above. To avoid the risk of loss of aid money, a pilot project could be undertaken to demonstrate this revised policy strategy. The new strategy would include, as an example, sensitizing the treatment and counselling centres to the differential power relations with regard to access to treatment within the target population and creating spaces for the marginalised section such as the hijras. India has presented an exemplary case of HIV/AIDS prevention with partnerships running in multiple levels NGOs, community based organisations, international aid agencies and UN institutions. The need now is to take stock of the policy path pursued so far, introspect and introduce corrective strategies where possible. Research outside the field of medicine, some of them cited here, have brought out grassroots accounts of how policies boil down to the lived experience of people. The path ahead is to incorporate them in the narrative discourse

34

Issue 1 March 2013

by negotiating spaces available within the constraints posed by the dominant policy discourse disseminated by the donors and global policy making bodies. Sudheesh Ramapurath Chemmencheri MSc. Social Policy and Development, 2013 S.Ramapurath-Chemmencheri@lse.ac.uk

References NACO. (2012). Annual Report 2011-2012. New Delhi: National Aids Control Organisation. (http://www.nacoonline.org/upload/Publication/Annual%20Report/NACO_AR_Eng% 202011-12.pdf )

Dolowitz, David and David Marsh. (1996). Who Learns from Whom: a Review of the Policy Transfer Literature. Political Studies XLIV, 343-357

Jensen, Jane. (2010). Diffusing Ideas for After Neoliberalism: The Social Investment Perspective in Europe and Latin America. Global Social Policy 10 (59), 59-84

World Bank. (2012). Charting a Programmatic Road-Map for Sexual Minority Groups in India. Report No. 55, South Asia Human Development Sector Discussion Paper Series. (http://ilga.org/ilga/static/uploads/files/2012/8/4/04232441.pdf )

GBC

Health.

(2011).

Who

We

Are

and

How

We

Work.

(http://www.gbchealth.org/our-coalition/who-we-are-how-we-work/ )

Bill

and

Melinda

Gates

Foundation.

(2009).

Avahan

Fact

Sheet.

(http://www.gatesfoundation.org/avahan/Documents/Avahan_FactSheet.pdf )

World Bank. (2011). The Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic among Men Who Have Sex with Men.

35

Issue 1 March 2013

(https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/2308/622610PUB 0glob01476B0extop0ID018726.pdf?sequence )

UNDP.

(2011).

From

the

Frontline

of

Community

Action.

(http://www.undp.org/content/dam/india/docs/from_the_frontline-ofcommunity_actioncompendium_of_six_succ.pdf )

UNADIS.

(2012).

Global

Report

on

the

AIDS

Epidemic.

(http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/ 2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_with_annexes_en.pdf )

NACO.

(2007).

Mainstreaming

and

Partnerships.

(http://www.nacoonline.org/NACO/Parterships/ )

Seckinelgin, Hakan. (2012). The Global Governance of Success in HIV/AIDS Policy: Emergency Action, Everyday Lives and Sens Capabilities. Health and Place 18, 453460

Reddy, Gayatri. (2005). Geographies of Contagion: Hijras, Kothis and the Politics of Sexual Marginality in Hyderabad. Anthropology and Medicine 12 (3), 255-270

36

Issue 1 March 2013

Development

37

Issue 1 March 2013

Afghanistan, Aid and Counter Narcotic Policy p.38-44 Becca Cockayne

In an ideal world, successful international intervention, established through peace-building structures, would allow for the creation of healthy interdependencies between rulers and peripheral elites. 1Unfortunately, the dynamic relationship between economic development initiatives and political conflict in frontier and transition states are far from clear. Government policy has looked to build Afghanistan into a stable Nation-State on the assumption that effective economic development strategy will lead to peace across the country.19 It has been designed primarily on the assumption that agricultural initiatives can act as a viable alternative to the opium industry2 and be the engine for Afghanistan's economic and social growth.3

A developmentalist approach has largely been propagated by USAID and other foreign investors; one that encourages private sector-led development through attempting to create chances for the poor to act as agents of their own destiny. It is less concerned with the structures that create poverty in the first place. Unfortunately, these strategies have not fulfilled their potential; since peace building initiatives began there has been only marginal development economically and socially.4 Moreover, despite billions of USD dollars of investment, Afghanistan ranked 158 out of 185 in the Human Development Index in 2011.5 Inter-ethnic violence, cultural clashes with international troops and studies highlighting rural Afghanistans high propensity for violence6 suggest current strategies are counter-productive. Moreover, inefficiency of economic policy is exacerbated by the existence of only weak conflict processing mechanisms7 which fail to overcome a substantial industrial roadblock: Opium. This article investigates the fragile relationship between economic development strategies and political conflict by analyzing that which existing Counter Narcotic and Agricultural policy neglects to consider; the short-term benefits of the established by the opium industry

1

Peacebuilding involves complex bargaining processes between rulers and peripheral elites over power and resources and when successful leads to stable interdependencies. See: Corrupting or Consolidating the Peace? The Drugs Economy and Post-conflict Peacebuilding in Afghanistan: JONATHAN GOODHAND 19 Peace Building and State-Building in Afghanistan: constructing sovereignty for whose security? BARNETT R RUBIN, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp 175 185, 2006 2 Afghanistan Post 2014: Economic Development Difficulties, Brasseur, 2005

3 4 5 6 7

Policy making in Agriculture and Rural Development in Afghanistan, Pain and Shah, 2009 Afghanistan Post 2014: Economic Development Difficulties, Brasseur, 2005 HDI 2010 index - Human Development Reports http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-17123464, Feb 2012

Introduction: Security, Governance and Statebuilding in Afghanistan, Christopher Freeman, international Peacekeeping, Volume 14, 2007

38

Issue 1 March 2013