Globalisation and Sustainable

Globalisation and Sustainable

Uploaded by

Syed Aiman RazaCopyright:

Available Formats

Globalisation and Sustainable

Globalisation and Sustainable

Uploaded by

Syed Aiman RazaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Globalisation and Sustainable

Globalisation and Sustainable

Uploaded by

Syed Aiman RazaCopyright:

Available Formats

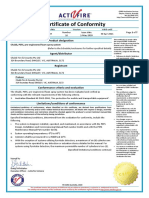

Globalization and Sustainable Development:

Issues and Applications

Edited by

Rebecca Lee Harris

Dr. Kiran C. Patel Center for Global Solutions

University of South Florida

Published in 2006 by:

Dr. Kiran C. Patel Center for Global Solutions

University of South Florida

4202 East Fowler Avenue, SOC102

Tampa, Florida 33620-6912

Phone: (813) 974-2954

Fax: (813) 974-2522

Email: GlobalResearch@cas.usf.edu

Website: http://www.cas.usf.edu/globalresearch

Cover design by Rebecca Hagen, in focus design, Tampa, FL

Cover photograph, Small-scale fishers using gillnets in the

Gulf of San Miguel, Panama, by Daniel Suman, Rosenstiel

School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami

Printing by Pro-Copy, Tampa, FL

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the

authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher.

Obtainable from the Dr. Kiran C. Patel Center for Global

Solutions at the University of South Florida.

ISBN: 0-9742736-9-4

Globalization and Sustainable Development:

Issues and Applications

Contents

Figures vii

Maps viii

Tables ix

Foreword 1

Rebecca Lee Harris

Part I: Broad Perspectives

1

The Evolution of Sustainable Development 13

Renu Khator and Lisa Fairchild

2

Sustainable Development: The World Is Still Oceans Apart! 23

O.P. Dwivedi

3

Third Systems, Human Security, and Sustainable Development 43

Jorge Nef

vi

Part II: Economic and Political Considerations

4

Shaping Globalization for Sustainable Development 61

Kwabena Gyimah-Brempong

5

Trade and Sustainable Development at the World Trade

Organization: Toward a Decision on Genetically Modified

Organisms

84

Michael Miller

Part III: Grassroots Movements

6

Sustainable Community for Sustainable Development: Mujeres

Reunidas and the Hhu of Hidalgo, Mexico

109

Ella Schmidt

7

Feminism, Poverty, and Grassroots Movements in India 133

Gurleen Grewal

8

To Save a City: Grassroots Movement toward Reforestation in

Ica, Peru

147

Richard Weisskoff

Part IV: Natural Resource Use and Policy

9

Environmental Degradation in a Conservation Model: Major

Forest Loss in Costa Ricas Amistad-Caribe Conservation Area

165

Michael Miller

10

The Case of the Shrimp Industry in Eastern Panama (Darin

Province): Unsustainable Harvest of a Valuable Export Product

and Its Limited Impact on Local Community Development

192

Daniel Suman

About the Authors 221

Figures

4.1

Average Annual Rural Population Growth Rate

69

4.2

Percentage Annual Change in Environmental Index

70

8.1

Direction of the mudslides, Ica, J anuary 29, 19

150

8.2

Looking toward Ica and the Ocean from atop a Mud Slide,

Cansas Canyon

151

8.3

Panorama of the Cansas Canyon, Ica, Peru

157

8.4

The Future Vision of the Cansas Canyon

158

Maps

9.1

Location of the ACLAC within Costa Ricas National System

of Conservation Areas

166

9.2

Map of Costa Rica with Political Boundaries and Topography

167

10.1

Map of Eastern Panama and the Darien Region

194

10.2

Important Fishing Zones in Panama

197

10.3

Coastal Communities in Darien Province

199

10.4

Important Shrimp Harvesting Areas for the Artisanal Fishing

Fleet in the Gulf of San Miguel

203

Tables

1.1

Comparing Development and Sustainable Development

18

1.2

Sustainable Development in the Global Context

19

3.1

Human Security/Insecurity: Analytical Matrix

57

4.1

Environmental Indicators, 2000

68

10.1

Shrimp Permits per Community Granted by the DGRMC,

1996, 2003

201

10.2

Finfish Permits per Community Granted by the DGRMC,

1996, 2003

201

10.3

Numbers and Percentages of Fishers in Coastal Communities,

2000

202

Foreword

Rebecca Lee Harris

INTRODUCTION

This book examines the relationship between two of the most

used and abused catchphrases of our timesglobalization and

sustainable development. While in some circles, being in favor of

one implies the demise of the other, the chapters in this book suggest

that both are forces with which we must simultaneously contend.

Indeed, it is only by embracing and yet harnessing globalizations

impacts that our worlds societies and economies can develop in a

sustainable manner.

The modern era of globalization may be rooted in the economic

consequences of the dismantling of barriers to international trade and

finance. However, in a broader sense, globalization includes the

increased connectivity of people around the world not just because

of an increased exchange of goods, services and capital.

Improvements in transportation and changing economic

opportunities have led to an increase in movements of peoples, both

through migration as well as tourism. Improved communications

technology has also increased connections among people and

peoples worldwide. Many would argue that globalization is not a

new phenomenon, but rather one that has been occurring to some

extent since the beginning of human history. However, there is a

general consensus that the rate of globalization has increased in

recent years and certainly our awareness of it (and accompanying

debate over it) has as well.

2 Rebecca Lee Harris

As several authors in this book note, the concept of sustainable

development first came into our common vernacular with the

publication of Our Common Future, the report issued by the U.N.

Commission on Environment and Development (often called the

Brundtland Commission, after Gro Brundtland, the head of the

commission). The report refers to sustainable development as that

which meets the needs of the present without compromising the

ability of future generations to meet their own needs. (p. 8)

Sustainable development requires a holistic view toward growth and

environmental stewardship, taking into account poverty and

inequality, human health and human capital, differences in cultures,

political conditions (including government budget pressures), and

global markets among other factors.

Given the complexity of the impacts of globalization and the

causes of sustainable or unsustainable development, it is no surprise

that the nexus of the two is not straightforward either. The

relationship differs across and within countries, as well as among

different aspects of environmental issues. For example, the increased

trade associated with globalization causes a shift in national

production as countries expand production in goods for which they

have an international market and contract production of other goods

for which it is economically more efficient to import. In the United

States, this has manifested itself in a shift from heavy manufacturing

to cleaner types of production, such as service industries.

However, many of the industries in the new economy of the U.S.

have their own environmental problems; witness the growing

problem of hazardous waste caused by dumping high-tech products.

In some poorer countries, pressures to export high-value agricultural

products, for example, often lead to unsustainable agricultural

practices, such as mono-cropping or intensive use of pesticides and

other chemicals.

Globalization may have positive or negative impacts on

individual or country-level incomes. The effects of these income

changes on sustainable development are also not clear cut. On a

micro level, as peoples incomes rise, they are likely to have better

education and more access to information which may help them

make more environmentally positive choices. In addition, individuals

can afford more environmentally-friendly goods, whether it be

cleaner fuels, fuel efficient cars, or products with recycled

Foreword 3

components. For a number of reasons, increased incomes slow

population growth, which is imperative to slowing down the use of

our natural resources. At the national level, wealthier countries are

more likely to have and enforce environmental regulations.

On the other hand, increased incomes have some detrimental

impacts on sustainability. As peoples incomes rise, they are also

more likely to consume more, including driving more, driving bigger

cars, demanding goods with more packaging (leading to more solid

waste), and demanding more energy and water.

However, not all segments of the population receive the

economic benefits of globalization. J obs may be lost due to

international competition, or social safety nets (such as food

subsidies) may be erased due to pressures from the international

lending community. For those whose incomes fall, the above-

mentioned effects on sustainability are reversed. In particular, food

insecurity in developing countries forces poor families to employ

environmentally unsustainable farming practices such as farming on

fragile lands or clearing forests to grow produce. In general, lower

incomes shorten ones time horizon such that poor families must pay

more attention to meeting current needs than worrying about future

needs. This, unfortunately, runs counter to the definition of

sustainable development as defined above.

In addition to economic manifestations, globalization is seen in

the increased movements of peoples, both within and among

countries. Improvements in transportation have eased the way for

migrants and travelers. Increased economic, educational and social

opportunities make urban areas, in particular, more attractive for

migrants. Rapid urbanization and the growth of mega-cities put

stresses on water and sanitation systems, increase traffic congestion

and pollution, and result in a loss of habitat as urban areas expand

outward. Tourism is another outcome of globalization forces. While

often promoted as a clean tool for economic development, often

the opposite is true. Large hotels, inefficiently expending water and

other natural resources, and influxes of tourists in environmentally

fragile areas, are just two ways that tourism often harms the very

resources that attracted visitors in the first place.

Whether or not increased connectivity among peoples

encourages or discourages sustainable development is also up for

debate. The proliferation of non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

4 Rebecca Lee Harris

has given a national and international voice to many concerns

previously unheard or ignored, while simultaneously linking activists

from around the world. The increased presence of civil society

groups both physically, at international forums, and virtually,

through improved communications technologies, has broadened

international awareness of a range of factors impacting sustainable

development. Increased contact with other peoples also impacts

cultural norms around the world about protecting the environment,

strengthening some and weakening others.

ABOUT THE BOOK

This book is the result of two symposia held at the University of

South Florida, in Tampa, Florida, in 2005, sponsored by the Patel

Center. The first symposium, held in April 2005, was designed to

give an overview of the issues involved in globalization and

sustainable development. The second symposium, held in J une 2005,

looked specifically at how poverty is related to sustainability, using

country case studies from around the world. The book loosely

follows the format of the symposia, starting with the initial

contextual presentations given by Renu Khator and Lisa Fairchild,

O.P. Dwivedi, and J orge Nef. These are followed by broad

perspectives on the political and economic dimensions of

globalization and the environment, with papers by Michael Miller

and Kwabena Brempong. Ella Schmidts presentation from the first

symposium joins those of Gurleen Grewal and Richard Weisskoff

from the J une symposium. These three papers present case studies of

grassroots movements to reduce poverty and improve the

environment. The final part of the book examines specific natural

resource use and policy, with research by Michael Miller and Daniel

Suman.

The three chapters in Part I of this book provide an overview of

the issues related to globalization and sustainable development.

Khator and Fairchild trace the history of the term sustainable

development since the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human

Environment. International environment summits have since

increased in importance and political influence, while the number of

attendees, both at the state and grassroots level, has grown. The

authors describe a holistic approach to sustainable development

Foreword 5

which includes equality, quality of life issues, sustaining resources,

both human and natural, and meeting international obligations.

Complementing this is the positive correlation between global

economic integration and the ability to protect the environment and

develop in a sustainable way. While the term sustainable

development has now become part of our lexicon, the authors

caution that it can be abused by those hoping to continue behaving in

a business as usual modus operandi.

In the next chapter, Dwivedi looks at sustainable development

from the perspective of North-South relations. He suggests that it is

time to re-think the North-South relationship. Since global

environmental problems are not constrained by national boundaries

nor by national incomes, the North and South must face these

problems as equals who are dependent on one another. Dwivedi

posits that poverty is the greatest cause of environmental

degradation, particularly via the high rates of population growth that

accompany poverty. For Dwivedi, then, poverty and

underdevelopment must be addressed in order to ensure sustainable

development. In Chapter 3, Nef takes a similar approach, looking at

how global inequalities impact the broader concept of human

security, which includes environmental security. Nef traces the

connection between inequality and unsustainable development, and

suggests that the resultant insecurity causes global vulnerability. As

in the previous chapter, Nef suggests that globalization has made all

countries interdependent, regardless of level of development. Thus,

as long as the South is insecure, the North will be as well. He

proposes that the environment agenda provides an opportunity to

reformulate the global agenda for human security, with a citizens-

based perspective.

Part II of this book analyzes the relationship between

globalization and sustainable development through two broad social

dimensions: economic and political. Brempong (Chapter 4) analyzes

the impact of economic globalization, which he considers inevitable

and, on net, beneficial. Because globalization enables producers to

substitute environmentally harmful production methods for more

benign ones, opening up markets can, in fact, have environmental

benefits. In addition, according to international trade theory,

economic openness and increased influence from international

research and development lead to increased growth. The resulting

6 Rebecca Lee Harris

raised incomes has a positive effect on the environment. Given the

high correlation between poverty and environmental degradation,

Brempong suggests that it is not globalization, per se, that is harming

the environment, but rather, globalization-induced poverty that is the

culprit. In order for globalization to help less developed countries

(LDCs) grow sustainably, they must learn to harness its forces to

their advantage. This occurs in two ways: internally, countries must

enact proper safeguards and correct institutional problems (e.g.,

develop land tenure systems, reform political institutions, and get

prices right). Globalization only exacerbates domestic problems

that already exist. Externally, LDCs must make sure they are part of

the international debate on environmental and trade treaties, partners

in crafting policy and in taking responsibility.

In Chapter 5, Miller looks more closely at the politics of these

international agreements, using the GMO (genetically modified

organisms) debate between the U.S. and the European Union as a

laboratory. Regardless of the state of development of the

participating countries, there is an inherent conflict between

international environmental agreements and other international laws.

Trade expansion will always raise problems of protecting the

environment and human health. Two main suggestions from the

author echo themes raised in earlier chapters: globalization can be

taken advantage of to standardize safety information worldwide,

which would benefit not only the disputing parties, but countries

around the world; and, the author calls for increased participation

from civil society groups and NGOs, who can ensure greater global

representation in these debates.

In Part III, three country-case studies examine poverty and

sustainable development from the grassroots level. Schmidt

highlights the importance of including culture in any efforts to offer

sustainable development programs in Chapter 6. An indigenous

community from Hidalgo, Mexico, the Hhu, are an example of

how globalizations impact on culture strengthens environmental

sustainability efforts. While the Hhu population in Mexico has

dramatically decreased due to migration to the U.S., cultural norms

dictate that its citizens continue to participate in the home

community, regardless of where the migrants live. Within that

obligation is a strong commitment to environmental stewardship. In

the community of El Alberto, a womens cooperative has sprung up

Foreword 7

in response to the economic pressures faced particularly by the

women who have been left behind by their migrating families.

Developed using a bottom up approach, the cooperative has used

indigenous knowledge to create products from the native maguey

(century plant). In a perfect example of sustainable development, the

women now have an incentive to re-forest their land with maguey,

and as a result, they are gaining income as well as business know-

how. The women benefit from a second globalization factor in force:

they sell their products on global markets, with the assistance of

NGOs whose very purpose is to serve as a broker for these activities.

In Chapter 7, Grewal examines three grassroots movements of

underserved Indian groups, representing poor women, oppressed

castes and indigenous tribes, to protect the environment and fight

against poverty. Implicit in Grewals analysis is a built-in tension

between the North and South, between the elite and the poor. She

further points out that there is a strong relationship between poverty

and gender inequity; reducing both of these problems is a necessary

component of sustainable development. Grewal introduces the

concept of ecofeminism the idea that women and nature are both

objects of mastery for the western rational male subject.

Ecofeminism, as more broadly interpreted in India, is a driving force

behind the holistic grassroots movements to improve womens

livelihoods, the environment, and rights of the poor, among others.

This perspective also suggests, as mentioned in earlier chapters of

this book, that if women are given more economic choices and

security, it will lead to reduced population growth. Similarly,

infrastructural changes, such as conferring property rights to women

and empowering local communities, will help them be more

effective stewards of the environment.

The final case study of environmental activism coming from the

ground up is Weisskoffs report on the city of Ica, Peru. For decades,

Ica has been caught in a pattern of city development followed by

destruction from mudslides. A group led by three citizens is working

to overcome these natural disasters that have been compounded by

human activity. Their solution lies in building natural dams with an

indigenous tree, the huarango, which would not only provide

environmental services (such as stemming soil loss and improving

soil with the decomposition of its leaves), but could also provide an

income source through its by-products (such as its fruit and its leaves

8 Rebecca Lee Harris

which provide forage for animals). The reforestation effort has the

added benefit of providing jobs, another cog in the sustainable

development cycle.

Finally, Part IV of this book looks at the unsustainable use of

natural resources and policy efforts to protect those resources.

Millers case study of forest use in one area of Costa Rica (Chapter

8) shows that even in a country with a reputation for sound natural

resource management policies, deforestation is still a problem. In

spite of a law protecting forests, which the author evaluates as

following sustainability principles, legal and judicial weaknesses,

poverty and insecure property rights add up to major problems in the

study region. Peasants are forced by poverty to cut down trees for

short-term income and space for farming. In addition, squatters clear

land in an attempt to secure land tenure. Intermediaries further

pressure peasants to cut trees in an unsustainable manner. Corrupt

regulators and weak enforcement further compound the problem.

Miller offers policy solutions to attempt to correct the structural

barriers to improved forest stewardship, including market-based

incentives which reward forest owners who protect their land.

While Sumans chapter (Chapter 9) examines the shrimp

industry in eastern Panama, many of the principles from the previous

chapter still hold. Suman studies a poor, isolated region where

shrimp exports are a major source of income. However, overfishing

by small and large-scale fishers (with the social tensions implied by

the relationship between these two groups) and weak government

enforcement are putting future catch in jeopardy. While the majority

of shrimp is destined for international markets, the number of

intermediate steps involved (processing, packaging, etc.) between

the point of capture and the market suggests that the locals do not

reap much of the profits in the final sale of the shrimp, thereby

necessitating even more exploitation of the resource. Local

investment to keep related value-added activities within the region,

as well as to offer economic alternatives to shrimping, and increased

government regulations and legislation will be necessary to improve

the sustainability of the industry.

Foreword 9

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Many of this books authors conclude that, ultimately, the

factors associated with globalization impact the environment most

through the ways in which they affect poverty. Poverty, in turn, is

shown to be at the root of many sources of environmental

degradation. To some extent, however, loss of natural resources can

itself contribute to poverty. Either way, the marginalized members of

society often bear the brunt of this loss, whether it be in terms of

longer searches for clean water or more difficulty in providing food

for themselves and their families.

Related to this is the extent to which inequalities prevent more

environmentally healthy behaviors and policies. At a global level,

many authors point out, the uneven relationship between countries of

the North and South has led to environmental policies that exclude

the poorer countries. Similarly, within countries, national and

regional policies must address income and gender inequalities to

ensure that all segments of the population are included. Since

environmental problems are not constrained by national boundaries,

gender differences or socio-economic distinctions, environmental

solutions must be comprehensive and inclusive in scope.

Many of the authors underscore the importance of grassroots

movements and paying attention to local cultural practices.

Indigenous knowledge and products can and do contribute to

sustainable development behaviors. At the same time, governments

must set aside resources in order to create workable regulations, with

accompanying monitoring and enforcement. Governments must also

address underlying institutional issues, particularly land tenure

systems, effective judicial and legal systems and transparent

regulatory systems, which contribute to sustainable development.

In short, developing sustainably in todays globalized world

requires a holistic and integrated approach. The authors of this book,

while coming from a variety of academic backgrounds and

perspectives, all acknowledge that no one discipline will suffice in

tackling the problem. Given the inevitability of globalization and the

necessity to develop sustainably, this book provides some roadmaps

to comprehensive and practical solutions for policymakers and

communities.

10 Rebecca Lee Harris

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Center gratefully acknowledges the participation of all of

the authors for their presentations and written work. We also

appreciated the oral presentations by Steve Lerner from

Commonweal, and Ambe Njoh from the University of South Florida,

St. Petersburg, at the J une symposium. The papers were all reviewed

by members of the Patel Center Editorial Board and edited by Lavina

Fielding Anderson. Carylanna Bahamondes provided invaluable

administrative support as well as the design and layout of the

manuscript. Finally, we are grateful to O.P. Dwivedi who initiated

and championed this project and inspired all of us with his

enthusiasm.

REFERENCE

World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common

future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

9

Part I:

Broad Perspectives

1

1

The Evolution of Sustainable

Development

Renu Khator and Lisa Fairchild

INTRODUCTION

Though the term sustainable development was not popularized

until the 1980s, the concept dates back to the 18th century when the

term sustainable was used to indicate concern about logging

practices (Dwivedi et al., 2001, p. 220). Over the years, the concept

has evolved and become a buzz-word for both environmentalists and

industrialists, with little agreement on the definition. This paper

traces the evolution of sustainable development from its inception

in the international realm at the 1972 Stockholm Conference through

the 2002 J ohannesburg Summit and beyond.

So, why has sustainable development become popularized?

Sustainable development offers an alternative to the traditional

concept of development, which focused on growth as the ultimate

end and regarded the means to achieve this end as irrelevant. Soon,

the antithesis to this dominant thesis emerged in the form of

radicalism in which development was interpreted as evil. It was

undesirable both as a means and as an end. Later years witnessed the

emergence of a synthesis in the form of sustainable development,

which implied that development may be desirable if approached

within a holistic framework. The emergence and evolution of the

14 Renu Khator and Lisa Fairchild

concept of sustainable development reflects an increased awareness

and interest in the long term view of development and the necessity

to preserve environmental integrity in a time of increasing

development.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: DEFINED

The root of the word sustainable comes from sus-tenere,

meaning to uphold. Additionally, Websters Dictionary (1999, p.

1111) defines sustainable as to keep in existence; to give support

or relief to; to supply with sustenance. These definitions indicate

that an important aspect of sustainable development is its pro-active

nature (Khator, 1998). Other definitions of sustainable also support

its active nature and supply additional principles to the concept.

Odum (1971, p. 223) applies the concept of sustainability to the

biological sciences and writes that sustainable behavior is prudent

behavior by a predator that avoids over exploiting its prey to ensure

an optimum sustainable yield. This definition indicates that in

addition to being active, sustainability is also self-regulating.

Sustainable behavior also implies maintenance of equilibrium, as

evidenced by Hicks definition. Hicks (1946, p. 172) defines sustainability

as being able to maximize the value one can consume during a week

and still expect to be as well off at the end of the week as...at the

beginning (Khator, 1998). Sustainable development is equated with

motion and continuous growth for Ophuls and Boyan (1977) who

explain that sustainability provides a dynamic equilibrium affording

ample scope for continued artistic, intellectual, moral, scientific and

spiritual growth.

Sustainable development also includes an intergenerational

component, a pattern of social and structural economic transformations

(i.e., development) which optimizes the economic and other social

benefits available in the present without jeopardizing the likely potential

for similar benefits in the future (Goodman and Redclift, 1991, p. 36).

Sustainability also implies equality, in a qualitative sense, as

explained by Korton (1990, p. 67), as ...a process by which the

members of a society increase their personal and institutional

capacities to mobilize and manage resources to produce sustainable

and justly distributed improvements in quality of life consistent with

their own aspirations. Finally, Barbier (1987, p. 103) integrates the

The Evolution of Sustainable Development 15

holistic nature of sustainable development in his definition which is

to maximize simultaneously the biological system goals (genetic

diversity, resilience, biological productivity), economic system goals

(satisfaction of basic needs, enhancement of equity, increasing useful

goods and services), and social system goals (cultural diversity,

institutional sustainability, social justice, participation).

Though there are many definitions of sustainable development,

the most popular is that of the World Commission on Environment

and Development, or the Brundtland Commission. In 1987, the

Bruntland Commission defined sustainable development as

development that meets the needs of the present without

compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own

needs (1987, p. 89). While there is no consensus on the precise

definition of sustainable development, the general concept has

succeeded in permeating international discussions on the

environment beginning with the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the

Human Environment.

EVOLUTION OF THE AGENDA

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, a number of

publications inspired interest in the environmental movement. Of

specific interest were Rachel Carsons Silent Spring (1962) and

Garret Hardins The Tragedy of the Commons (1968). Following

Carsons lead, many people in the 1960s predicted a doomsday in

the 1960s and called for an immediate moratorium on growth, for

they believed growth to be the root cause of environmental

destruction (Meadows, 1972). Such concerns were voiced at the

1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment. Originally,

developing nations, particularly the South, planned on boycotting the

conference; however, they chose to participate once the scope of

development was broadened to include issues of poverty and other

ills of underdevelopment. Ultimately, representatives from 111

countries attended the Conference, although only two heads of state

(India and Sweden) were in attendance. Though the conference is

perceived as having limited success, it elevated environmental

concerns to an international level.

Numerous short-comings were identified as contributing to the

limited success of the Stockholm Conference: first, development was

16 Renu Khator and Lisa Fairchild

presented as black and white; second, pollution was defined as a

purely environmental problem with no regards given to the social

aspects; and third, the conference ignored the agenda of the

developing countries. Despite these shortcomings, important

developments were made and the conference led to the development

of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the

Stockholm Declaration on Human Environment, several multilateral

environmental agreements, and environmental policies in many

countries.

There would be two critical developments between this and the

1992 Earth Summit in Rio De J aneiro. In 1982, the World

Commission on Environment and Development was formed.

Consequently, the report Our Common Future was published in

1987, and introduced the term sustainable development, as defined

in the previous section. Additionally, in 1986, new trade talks, which

would lead to the creation of the World Trade Organization in 1994,

reinforced the idea that the world had shrunk and a global dialog on

new development had become necessary. Following these

developments, the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio advanced the agenda of

the 1972 Stockholm Conference.

The 1992 Earth Summit expanded in scope, as well as in

attendance, from its 1972 predecessor. In attendance were

representatives from 167 nations as well as 116 heads of state. In

addition to the increased government participation, 7,892

representatives from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and

8,000 journalists were also present for the summit (J ohnson, 1993).

This marked increase in attendance over the 1972 Stockholm

Conference indicates an increased inclusivity with public, private

and non-profit sectors. Despite the appearance of increased

inclusivity, the attention paid to the developing nations of the South

was not satisfactory, and the ability to positively affect the

environment still remained in the hands of the North. Additionally,

trade patterns still remained skewed to the North. Finally,

international agencies were failing to create real opportunities for the

South. In order to address these concerns, Agenda 21 was created at

the Earth Summit as a plan of action, and the Commission of

Sustainable Development was established in order to monitor

progress. Again, there would be significant developments between

the 1992 Earth Summit and the 2002 J ohannesburg Summit.

The Evolution of Sustainable Development 17

One of the major outcomes of the Uruguay Roundtable, held

J anuary 1, 1995, was the establishment of the World Trade

Organization (WTO), which would shape the global economy by

providing free trade of goods across national borders. The

development of the WTO also had significant implications for

the environment. According to Muller-Kraenner (2002, p. 19) its

establishment demonstrated a move from the classic treatment of

environmental and development issues to more confrontational

discussions over economic globalizations. This shift in focus has

generated severe criticism. The most severe critique of free trade is

that it encourages countries to ignore their commitments to

environmental obligations and human rights (Esty, 1994; Barrett,

1994; Rauscher, 1994). Critics argue that in pursuit of global business,

poor countries create free zones with relaxed environmental laws,

unregulated labor, and undesirable subsidies. These concerns would be

voiced at the Johannesburg Summit in 2002.

The growing concern over global environmental issues was

reflected by the participation at the 2002 J ohannesburg Summit. It

was attended by over 22,000 people including 100 heads of state,

10,000 delegates, 8,000 group representatives and 4,000 members of

the media (United Nations, 2003). There were five major issues

addressed at this meeting: water/sanitation, energy, health,

agricultural productivity and biodiversity protection/ecosystem

management (United Nations, 2003). This summit, like the ones

before, was perceived as a missed opportunity which depended on

the cooperation of rich nations for success, and failed to address

North/South disparities.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT REVISITED

The objectives of sustainable development have been

summarized by the Government of Canada (2002) as a virtuous

cycle with five components: (1) promoting equality, (2) improving

the quality of life and well-being, (3) sustaining natural resources

along with sustainable jobs, communities and industries, (4) protecting

human and ecosystem health, and (5) meeting international obligations.

Though this circle was designed to illustrate Canadas objectives of

sustainable development for its citizens, the objectives can be

generalized to apply to all nations.

18 Renu Khator and Lisa Fairchild

Additionally, to better understand the objectives of sustainable

development, it is helpful to examine the characteristics that distinguish

development from sustainable development, shown in the

following table (Khator, 1998, 1788-1789). Sustainable development is

distinct from development in its emphasis, scope, political sphere,

cultural context, decision-making system and accountability. It is

holistic, comprehensive, active, engaging, participatory and responsible.

Table 1.1 Comparing Development and Sustainable Development

Characteristic Development

Sustainable

Development

Emphasis Economic_ Comprehensive

Scope Developing Countries All Countries

Political Sphere Neutral Active and Engaging

Cultural Context Neutral Differences

preclude replicability

Operational Mode Unilateral transfer

of knowledge

Bilateral transfer

of lessons

Decision-Making

System

Centralized

Administration

Decentralized

Administration

Non-Governmental

Involvement

No role of non-

governmental actors

Dependent on non-

governmental actors

Role of Foreign

Aid

Aid is a privilege Aid is a responsibility

Accountability No accountability Accountability to people

and to the international

community

Source: Khator, 1998

Though much progress has been made since the initial summit in

Stockholm, the concept of sustainable development still has a long

way to go. Despite the universal validity of the concept, it has yet to

gain paradigmatic coherence. Additionally, the term is used widely

by environmentalists and industrialists, by users as well as abusers.

As critics of sustainable development point out, the term may

mean little more than business as usual. Lele (1991, p. 619) sums it

The Evolution of Sustainable Development 19

up by stating that sustainable development is an attempt to have

ones cake and eat it too. An additional obstacle to the success of

sustainable development is weak global governance which makes it a

common good agenda item. Finally, the global context of trade

poses significant challenges in terms of human securityincluding

human rights, poverty and scarcity.

The integration of a country into the global economy may impact

that countrys ability to achieve the conditions necessary for

sustainable development. Depending on its level of integration (core,

peripheral, sub-peripheral) the impact of free trade will be different on

a countrys economic, political, and social agenda and consequently,

the country will find that its capacity to adhere to its environmental

and human rights obligations varies. Free trade is neither good nor bad

for sustainable development, nor is its impact the same for all

countries. We hypothesize that a countrys position in the global

economy plays an important intervening role in defining the

sustainable agenda of the country. The following table provides a

conceptual model of the impact of free trade on the economies of

trading countries and on their environmental obligations, which are

critical to sustainable development in a global context.

Table 1.2 Sustainable Development in the Global Context

Trading

Position in

the Global

Market

Economic

Growth

Level of

Environmental

Protection

Capacity for

Sustainable

Development

Core

Countries

Stable growth High due to public

pressure and

increased awareness

High because

choices are

available globally

Advanced

Peripheral

Countries

Rapid growth

due to economic

agility and

adaptability

Low due to

conscious trade-offs

Possible if

conditions are set

Sub-

peripheral

Countries

Low due to

struggle for

survival

Low due to

lack of choices

High due to low

global pressures

Core trading societies, as shown above, will fair better than

either advanced peripheral or sub-peripheral countries in fulfilling

20 Renu Khator and Lisa Fairchild

their commitment to environmental protection and to developing in a

sustainable manner. The high level of environmental protection in

these countries is due to increased public awareness and pressure

coupled with economic capacity. Advanced peripheral countries or

the countries that are rapidly integrating into the global economy, on

the other hand, will be economically capable of observing

environmental obligations; however, they will not possess the

political will to do so. Their capacity to grow in a sustainable manner

exists; however, conscious decisions will have to be made by the

political leadership. Finally, sub-peripheral countries (or countries

whose economy may be tied to the world economy but only through

another core or advanced peripheral country) will experience the

least benefit from free trade, as their primary struggle is with

survival and not expansion. In these countries, the interests of the

corporate class dominate and the environment is likely to suffer as a

result of this.

CONCLUSIONS

The term sustainable development is a dynamic one and has

evolved from an 18

th

century concept to a buzz word used by many,

with little regard to the definition. Over the years the definition has

evolved to express various characteristics of the concept including

(but not limited to): its active nature, continuous growth,

intergenerational concerns, and holistic nature. In 1987, the most

popular definition of this concept was created by the Bruntland

Commission and presented in Our Common Future. Even before

popularization of the term, the concept had succeeded in infiltrating

international discussions on the environment. Spawned by publications

implying the dangers of development, the environmental movement

grew out of the 1972 Conference on the Human Environment in

Stockholm, where the concept of sustainable development gained

international recognition. In the three decades after Stockholm, there

would be two more major international conferences on the

environment: The Earth Summit in Rio in 1992 and the

J ohannesburg Summit in 2002. Each summit exhibited an expansion

in both attendance and scope; however, they were all perceived as

missed opportunities. One major criticism is that the conferences

failed to address North-South disparities. Addressing these disparities

The Evolution of Sustainable Development 21

is integral to the success of sustainable development as the ability of a

country to achieve conditions for sustainable development is related

to the integration of that country into the global economy. Though

much progress has been made since the initial summit in Stockholm,

the concept of sustainable development still has many challenges to

face before it becomes an accepted paradigm for a healthy way of life.

REFERENCES

Barbier, E.B. (1987). The concept of sustainable economic development.

Environmental Conservation 14, 101-110.

Barrett, S. (1994). Strategic environmental policy and international trade.

Journal of Public Economics 54(3), 325-338.

Carson, R. (1962). Silent spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Dwivedi, O.P., Kyba, J.P., Stoett, P., and R. Tiessen (2001). Sustainable

development and Canada. Peterborough, Canada: Broadview Press.

Esty, D. C. (1994). The case for a global environmental organization. In

Peter B. Kenan (ed.), Managing the world economy: Fifty years after

Bretton Woods (pp. 287-309). Washington, DC: Institute for

International Economics.

Goodman, D. and M. Redclift, eds. (1991). Environment and development

in Latin America: The politics of sustainability. New York: Manchester

University Press.

Government of Canada (2002). What is sustainable development?

Retrieved on March 28, 2004 from http://www.sdinfo.gc.ca/what_is

_sd/index_e.cfm.

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science 162(3859), 1243-

1248.

Hicks, J .R. (1946). Value and capital (2

nd

ed.). Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

J ohnson, S.P. (1993). The Earth Summit: The United Nations Conference

on Environment and Development (UNCED). London: Graham and

Trotman.

Khator, R. (1998). The new paradigm: From development administration to

sustainable development administration. International Journal of

Public Administration 21(12), 1777-1801.

Korton, D. (1990). Getting to the 21

st

Century: Voluntary Action and the

Global Agenda. West Hartford, CT: Kumarian.

Lele, S. (1991). Sustainable development: A critical review. World

Development 19(6), 607-621.

22 Renu Khator and Lisa Fairchild

Meadows, D.H., et al. (1972). Limits to growth: A report for the Club of

Romes Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe

Books.

Muller-Kraenner, S. (2002). On the road to J ohannesburg. Development

45(3), 18-23.

Odum, E.P. (1971). Fundamentals of ecology (3

rd

ed.). Philadelphia: W.B.

Saunders.

Ophuls, W. & S. Boyan, J r. (1992). Ecology and politics of scarcity

revisited: The unraveling of the American Dream. New York: W.H.

Freeman.

Rauscher, M. (1994). On ecological dumping, Oxford Economic Papers.

46(5), 822-840.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for

Sustainable Development (2003). The road from Johannesburg: World

Summit on Sustainable Development: What was achieved and the way

forward. New York. Retrieved on August 29, 2005 from http://www.

un.org/esa/sustdev/media/Brochure.PDF

Websters II new college dictionary. (1999). Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Company, 1111.

World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our

common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2

2

Sustainable Development:

The World Is Still Oceans Apart!

O.P. Dwivedi

INTRODUCTION

Humanitys role in manipulating its surroundings is enormous

and ranges from the obvioussuch as damming great riversto the

subtlethe effects of DDT on the reproduction of wildlife. The

modern concern over environmental impact started in the late 1960s.

Soon thereafter, some environmentalists began to propose a right

to environmental quality. Their proposals included mostly decision-

making tools, such as environmental impact assessment, duties and

regulations imposed on private industries and corporations, and

powers acquired by the state to monitor potentially polluting

activities both in the public and private sectors. However, the

assessment of environmental impact does not stop at measuring

pesticide residues and the amount of mercury in fish. It involves the

quality of life on earth and, indeed, the ability of human beings to

interact with nature and survive in the long run. It also means that

pollution, destruction of species and natural areas, and depletion of

resources cannot be placed second to peoples materialism and their

desire for technological progress.

The continuing deterioration of our planets ecology poses a

major threat to the viability of our world. Nowhere is the evidence of

24 O.P. Dwivedi

global ecological deterioration better argued than in Our Common

Future, a report by the World Commission on Environment and

Development (also known as the Brundtland Commission). But the

real significance of this report lies first in its thorough explanation of

why we, the people inhabiting this planet, are collectively destroying

natural resources; second, in its thesis that we cannot save the

environment without development, but at the same time, we cannot

keep on developing unless we save the environment; and third, in its

main recommendationthat unless we restructure the existing

institutional arrangements and legal mechanisms, fragmentation,

overlapping jurisdictions, narrow mandates, and closed decision-

making processes will continue. As the report states, The real world

of interlocked economy and ecological systems will not change; the

policies and institutions concerned must (World Commission, 1987,

p. 310). The commission also warned: The time has come to break

out of past patterns. Attempts to maintain social and ecological

stability through old approaches to development and environmental

protection will increase instability. Security must be sought through

change. . . . Without reorientation of attitudes and emphasis, little

can be achieved (World Commission, 1987, p. 309).

But for developing nations, this warning concerning the

protection of the environment must be balanced against such

pressing human security problems as the population explosion,

chronic poverty, and providing minimum health care and necessary

sanitation, shelter, and other basic needs for their people. In addition,

these nations are impelled to harmonize economic development with

such environmental values as biodiversity protection and

conservation, sustainable resource use, and environmental quality in

general, as necessary ingredients to augment the well-being of all.

NORTH-SOUTH ENVIRONMENTAL RELATIONS

The end of the Cold War has given humanity an opportunity for

a fundamental rethinking of the nature of relations among nations.

That rethinking ought to be directed toward the solution of the

planetary-proportion threat being caused by ecological disaster and

continuing poverty. In our world, poverty prevents one-fourth of

humanity from receiving even basic needs (adequate food, safe and

sufficient water, primary health care, education, and shelter). As long

Sustainable Development: The World is Still Oceans Apart! 25

as this economic disparity remains, stress on the environment will

also continue. For the poor, the struggle for survival overrides any

concern for the environment. At the same time, although for

different reasons, both North and South continue to exhaust the

Earths resources. That is why environmental concerns ought to be

acknowledged as the fundamental point of agreement in their

relationship.

A global policy requires consideration of all and for all. Until

now, we have had a sharp discrepancy between rich and poor,

between developing and affluent, between North and South, and

between First and Third Worlds. This distance is not closing, despite

rhetoric to the contrary. The distinction has been based on the

economic progress and material well-being of people living in two

separate worlds, isolated from each other not only because of

geographical boundaries, trade barriers, and economic prosperity,

but because of political dominance. However, various environmental

crisessuch as ozone depletion, the greenhouse effect, disappearing

biodiversity, and the need to protect world commonsdo not respect

such barriers and borders. We know that ecological disasters have

ways of affecting even those who may not live in close proximity, as

happened during the tsunami disaster in late December 2004. Thus,

the old distinctions which marginalized the poor of the

underdeveloped world while keeping the wealthy secure and

privileged are outmoded because both groups have to share the same

planet and its dwindling resources (Dwivedi, 1994). Although this

realization is perhaps much more apparent in the poorer sections of

our global society than in the richer parts; nevertheless, a similar

sensitivity is arising among the people of the North that no group can

live in isolation from the other.

For the South, poverty alleviation is the most crucial task of

these times; while for the North, ozone depletion, deforestation, or

population growth in the South are more important global issues.

This difference in perspective was first highlighted by Mrs. Indira

Gandhi at the 1972 United Nations Conference on Human

Environment in Stockholm: On the one hand the rich look askance

at our continuing povertyon the other, they warn us against their

own methods. We do not wish to impoverish the environment any

further and yet we cannot for a moment forget the grim poverty of

26 O.P. Dwivedi

large numbers of people. Are not poverty and needs the greatest

polluters? (1972, p. 2).

It is obvious from various reports of the World Bank that people

in developing nations are still struggling with poverty, hunger,

squalor, and poor health care. To such people, environmental

problems are actually afflictions of overdevelopment in the

industrialized North, although they are now convinced that

environmental protection is also a threat. This perspective gives

them a different view about population growth and the continuation

of poverty. These two aspectspopulation growth and povertyand

their impact on the environment, are discussed below.

POPULATION GROWTH AND

ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION

Demographytaken as the size of the population and its rate of

growthis considered a principal factor in environmental

degradation, since the faster the population increases, the more

natural resources are depleted, causing environmental degradation.

But reduction in population increase, if that is the answer, is difficult

to achieve, even if some authoritarian measures are employed. For

example, when Mrs. Gandhi ordered vasectomy operations to reduce

Indias population during her emergency rule in 1975-1977, the

general election of 1977 repudiated her policy. No political leader

has since dared to raise this issue in India. Demographers have

estimated that, even in the unlikely event that we managed to

immediately reduce world fertility to a level of simple replacement

(two children per couple) and to maintain this level in the future

the world population, due to the effects of its present age distribution

and to the expected increase in life-expectancy, would continue to

grow for approximately a century before leveling off at almost

double the present figure (Cabre, 1993, p. 2). In the case of India, it

was argued during the 1970s and 1980s that its population has

outstripped its carrying capacity (Commission, 1992, p. 33). However,

such predictions have not proven accurate even when the countrys

population grew beyond 1 billion in 2001. Through better land use,

soil management, increased levels of agricultural inputs, and

improvements in seed quality, the country could feed not only many

Sustainable Development: The World is Still Oceans Apart! 27

more million people compared to its 1970s level, but also export or

provide food aid to needy neighbors.

Two dimensions of demographic trends should also be taken into

consideration: aging populations and youth bulges. As death rates

are declining, populations are growing older. It is generally known

that aging populations have less demand on the environment but

more for health-care services. Similarly, the youth bulge has reached

crisis proportions in several developing nations where youth account

for more than 40 percent of all adults. According to the United

Nations (2003), more than 100 countries have youth bulges

compared to North America and Europe where youth accounts for

about 20-25% of all adults. Even in the case of those bulges,

environmental security is not the issue. On the contrary, a large

proportion of young workers can prove to be a demographic bonus

to economic prosperity (Mastny & Cincotta, 2005, p. 24). Thus,

population increase is not always the culprit when environmental

damage occurs.

Perhaps it is easier for the North to recommend population

control because, in the past, the heavily populated countries of

Europe were able to unload their growing population on the new

colonies of the Americas and Australia-New Zealand. However,

developing nations have no new frontier to which they can export

their surplus population. Of course, their population growth has to be

controlled, but we know from past experience that a high population

density does not always cause the same proportion of environmental

degradation as less densely populated nations. For example, if one

compares the population density of the United States or Australia

with India or China during this century, it is clear that there has been

more environmental destruction per capita in the first two countries

than in the last two over the same period. This is what Mrs. Gandhi

meant when she stated, It is an over-simplification to blame all the

worlds problems on increasing population. Countries with but a

small fraction of the world population consume the bulk of the

worlds production of minerals, fossil fuels and so on (1972, p. 2).

Anna Cabre (1993) gives one glaring example from the American

past. In a single decade, between 1870 and 1880, the skeletons of

750,000 bisons (buffalos) were loaded at one particular railway

station for shipment to fertilizer factories (1993, p. 2). Instead of

28 O.P. Dwivedi

emphasizing population as a factor in environmental degradation, we

should look for another culprit; and that culprit is poverty.

POVERTY AND POLLUTION

At the Rio Summit, leaders of the South hoped to link the issue

of poverty with global environmental problems; however, they later

found that, due to the 1990s economic crisis, the issue was sidelined

by nearly all industrialized nations. By the time the World Summit

was held in 2002, poverty and the needs of developing nations were

yet to be addressed appropriately despite four decades of

developmental efforts. When the international aid program started in

mid-1950s, it was presumed that, in relatively few years, basic

human needs (food, living conditions, health care, and education)

and social justice would be achieved. But this did not happen. For

hundreds of millions of people, life remains a constant struggle for

survival. Sustainable environment for them can become credible

only when poverty is eradicated and living conditions become

tolerable. As Shridath Ramphal, former Secretary General of the

Commonwealth of Nations and a member of the Brundtland

Commission noted: If poverty is not tackled, it will be extremely

difficult to achieve agreement on solutions to major environmental

problems. Mass poverty, in itself unacceptable and unnecessary, both

adds to and is made worse by environmental stress. . . . That is why

the global policy dialogue must integrate environment and

development (1992, p. 17).

Mass poverty has remained a worldwide concern. In 2000, the

United Nations Millennium General Assembly adopted eight

Millennium Development Goals (MDG):

1. Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger.

2. Achieve universal primary education.

3. Promote gender equality and empower women.

4. Reduce child mortality.

5. Improve maternal health.

6. Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases.

7. Ensure environmental sustainability.

8. Create global partnerships for development.

(United Nations, 2000)

Sustainable Development: The World is Still Oceans Apart! 29

Among these eight goals, both poverty alleviation and ensuring

environmental sustainability are supposed to be met by 2015.

Can the seventh goal, environmental sustainability, succeed?

Past experience with similar U.N. developmental decades and other

exhortations indicate that the results are going to be mixed. But one

thing is clear: sustainable development as a paradigm has changed

our old concept of economic development. The concept emphasizes

the need, among other things, (a) to conserve biological diversity in

genes, species, and eco-systems; (b) to recognize the dynamic,

constantly evolving, and often unpredictable properties of nature; (c)

to be conscious of our responsibility, in the form of environmental

stewardship, to protect the global environment; and (d) to respect the

intrinsic value of global commons as well as the need for

intergenerational equity. Furthermore, the concept provides for an

operational definition which establishes equity among the nations of

North and South. For example, how do we address the issue of

incomplete development faced by most of the poor nations? This

issue includes such aspects as population growth without an

adequate fall in birth rates, while the mortality rate has fallen and life

expectancy has risen. Or what do we do with the exodus from rural

areas and resultant urban growth? And when it is replaced by another

paradigm (discussed later in this essay), again a similar optimism

might ensue. But there is no assurance that our world will not remain

oceans apart!

THE WORLD IS STILL OCEANS APART!

What are the specific challenges that keep the North and South

oceans apart? I offer the following twelve proposals and

observations:

1. Mainstream the Environment

Thus far, there has been a natural tendency to think of

environmental issues primarily in terms of how to avoid doing harm

and what policies to safeguard the environment should be in place

when a new development project or an international aid-dependent

project begins. Once the project receives its environmental impact

assessment (EIA) clearance, attention to environmental concerns is

sidelined especially by financial institutions (such as a ministry of

30 O.P. Dwivedi

finance), infrastructure specialists, and on-site project management

teams. And if later, some environmental problems crop up, clean-

up work starts. Moreover, after a project has received EIA

clearance, constituencies for the poor (who tend to bear the brunt of

environmental harm) and the environment continue to be

underrepresented in the decision-making processes. Frances

Seymour (2004) from the World Bank has suggested that, instead of

addressing the environmental safeguards on a project-by-project

basis, sustainability and environmental safety concerns should be

integrated or mainstreamed into country-wide plans (e.g., five-year

plans) and into sectoral and cross-sector strategies, instead of placing

such issues in separate policy compartments (p. 17).

2. Strategizing Sustainable Development

The sustainable development approach offers nations an

opportunity to integrate economic strategies, environmental

integrity, and social equality. There is an urgent need to develop

integrative, forward-looking, cross-sectoral processes for linking and

balancing environmental, social, and economic policy objectives.

But such integration depends on reconciling the three pillars of

sustainability: (a) living within [our] global biophysical carrying

capacity; (b) providing a decent living standard for all people; [and]

(c) ensuring a reasonable measure of distributional fairness in access

to resources and their economic benefits (Sadler, 1996, p. 26).

These pillars capture some of the practical solutions and idealistic

goals of sustainability. However, they do not tackle the fundamental

causes of unsustainable development and offer few avenues for

policy direction. Thus, what is needed is a deeper understanding of

who in a country (or, for that matter, in the world taken as a unit)

lacks access to and control of resources and why.

In addition, it is equally crucial that state governments allocate

additional commitments to ensure multisectoral perspectives and

approaches by incorporating them into each nations policy-planning

and decision-making processes. However, as long as unsustainable

development policies are primacy in economic policy, we will

continue to live unsustainably. If we as a species want to do better,

then we need to identify how these changes can take place and how

Sustainable Development: The World is Still Oceans Apart! 31

an appropriate sustainable development policy can be more

expediently translated into practice (Dwivedi et al., 2001, p. 236).

3. Assure Planetary Survival with Ecological Diversity

Diversity is directly linked with adaptability and with the

survivability of species. For example, people migrating from one

geographic system have been able to adapt to another totally

different kind of environment since the beginning of human history.

That new environment in which those migrant people sought

stability and prosperity was born out of diversity. It is the diversity

which impels us to adapt and seek benefit from new surroundings. In

contrast, uniformity creates dependency, inflexibility, and a lack of

adaptability to new and challenging situations. Human ingenuity is

based on such challenges. In the absence of such challenges,

creativity, genius, and immunity fade slowly. The strongest societies

are those that are the most diverse, as is the case with ecosystems

(Dwivedi & Khator, 2005).

4. Control Worldwide Bio-piracy

It is an understatement to note that biodiversity is declining at an

unprecedented rate. For example, in China alone, 10,000 varieties of

wheat were under cultivation in 1949; by the 1970s, only 1,000 were

still in production. In Mexico, only about 20% of the maize varieties

in production in 1930 are still being grown. In the Philippines,

thousands of rice varieties were once cultivated. Nowadays two

varieties account for more than 98% of the rice acreage (Nierenberg

& Halweil, 2005, p. 64). As mentioned during the World Summit in

2002, half of the tropical rainforests and mangroves are gone, 75%

of marine fisheries stock is gone; mono-culture and bio-seeds are

further affecting biodiversity; and many nations report the

continuing decline of their biodiversity genetic pool (Dwivedi &

Khator, 2005).

Scientists in industrialized nations are busy patenting inventions

made in publicly funded research institutions and universities,

permitting scientific journals to fall under corporate ownership, and

stealing genetic resources from indigenous communities, including

the cell-lines and genes of indigenous people. Is this not plagiarism

at an international level? For example, the Brazilian government

32 O.P. Dwivedi

estimates that 97% of the 4,000 patents taken out on natural products

in their country between 1995 and 2000 were made by foreigners.

So, bio-piracy is rampant. In February 2002, 12 countries (India,

China, Brazil, Indonesia, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Kenya,

Peru, Venezuela, Mexico, and South Africa) formed an alliance to

press for the protection of indigenous genetic resources because they

collectively possess 70% of the worlds biodiversity in food crops

(INES, 2003, p. 6).

5. Affirm the Earth Charter

By the time we entered the third millennium, it became

increasingly clear that many of our values were totally inadequate

for long-term survival and for the development of a sustainable

future in which all species (not only human beings) are taken care of.

This conclusion was evident from the emergence of a wide spectrum

of challenges to the traditional materialistic view. Guided by

Western culture, people have had blind faith in the prowess of

science and technology to produce material progress.

Only recently have we understood that so-called material

prosperity should not be an end in itself. Slowly, a realization is also

emerging that spirituality and the control of ones desires can bring a

more lasting happiness than acquisitive materialism. However, such

a realization has yet to enter the domain of governmental policy or

the corporate world, where spiritual perspectives are generally

ignored. Economic criteria which place no value on the commons

(the air, water, oceans, outer space, etc.) and which use concepts

such as cost-benefit analysis, law of supply and demand, rate of

return, land as commodity, etc., have been based on the delusion that

they operate independently of the cultural and spiritual domain. Until

now, we have taken a great deal from our Mother Earth. We have

given little thought to limiting our plundering and ravaging instincts.

Without a change in our current value system, there is little hope of

correcting the environmental problems we face today. Slowly, a

heightened consciousness is emerging for the formation of a new

international environmental rights regime, including instilling

respect for Mother Earth and care for all species in creation. The

Earth Charter is a proper instrument for helping to empower that

consciousness. It is also clear that, without a universally accepted

Sustainable Development: The World is Still Oceans Apart! 33

regime of environmental protection, world resources will continue to

be depleted and the quality of life for the majority of people on earth

will remain questionable.

For this reason, we urgently need a holistic vision of basic

ethical principles supported by broadly accepted tenets and practical

guidelines that should govern the behavior of people and states in

their relations between each other and the Earth (Dwivedi & Khator,

2006). This is not a new demand; it has been persistently called for

by various environmental NGOs, international organizations, and

reports such as Our Common Future by the World Commission on

Environment and Development (1987), and Caring for the Earth, a

report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and

Natural Resources (1991).

6. Poverty is the Greatest Challenge

Environmental stress is caused less by poor nations than by

voracious consumption in the North. The pressure on natural

resources increases with consumption. Consumption pressure is a

factor of the number of people making demands, but it is also a

factor of consumption patterns. It has been estimated that every birth

in the North puts as much pressure on resources as tens of births in

the South. Thus, in addition to the eradication of poverty in the

South, lifestyles in the North must be modified. For example, the

World Commission on Environment and Development has estimated

that the cost of implementing Agenda 21 could be about $US125

billion a year until the end of this century. And as most of the

expenditures are related to managing commons and assisting poor

nations, it is helpful to recognize that in 1990 developing nations

transferred $140 billion in debt service payments, capital and

interest, to creditor nations (Ramphal, 1992, pp. 253-254). If the

North can divert a part of this sum toward global environmental

protection and sustainable development, our world will be a better

and safer place to live.

Some may argue that the establishment of the Global

Environmental Facility (GEF) has addressed this concern; however,

there have been criticisms about the facilitys governing structure, its

strategies, and its operative procedures. Although in March 1994, a

new instrument of governance for GEF was agreed upon between

34 O.P. Dwivedi

North and South, it has adopted, as some critics contend, many of

the failings of its administrative parents, and particularly those of the

[World] Bank (J ordan, 1994, p. 266).

7. Globalization of our World

Thomas Friedman argued in The Lexus and the Olive Tree that

countries which tried to avoid globalization became poorer. He

pointed out that between 1975 and 1997, the 8% of countries with

open markets (accounting for $23 billion of direct foreign

investment) had expanded to 28% (with $644 billion of foreign

investment). Hence, nations which hesitate or avoid globalization are

doomed to poverty (Friedman, 1999, pp. 8-9). The World Bank

(2000) also asserts that, since 1980, globalizers have growth rates

three times those of non-globalizers. It also reported that, with

globalization, countries were impelled to improve public services,

provide better social security nets, and even increase environmental

protection.

Nevertheless, ground realities are different. The World Banks

statistics show that the average income in the 20 richest countries

was 37 times the average in the poorest 20, a gap that has doubled

during the past 20 years (World Bank, 2000, p. 3). Another

impediment to poverty alleviation is the trade barriers imposed by

the rich nations. The New York Times reported that in 2002

industrialized nations provided $320 billion in farm subsidies

compared to $50 billion in international aid (Editorial: Harvesting

Poverty, 2003, p. 10). For example, the United States gives a $3

billion subsidy to its 25,000 cotton farmers thereby wrecking world

cotton prices (Werlin, 2004, p. 1034). If these subsidies were

reduced, about 114 million people in poor countries could be pulled

out of poverty.

One thing appears certain: There is no way to avoid