Ethics of Inclusion

Ethics of Inclusion

Uploaded by

JakovMatasCopyright:

Available Formats

Ethics of Inclusion

Ethics of Inclusion

Uploaded by

JakovMatasOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Ethics of Inclusion

Ethics of Inclusion

Uploaded by

JakovMatasCopyright:

Available Formats

The Ethics of Inclusion

John OBrien & Marsha Forest

We want to begin a dialogue on the expectations about personal behavior that

go along with a commitment to inclusion. Unattainable expectations confuse

good people and fragment efforts for change into factions organized around

hurt feelings. We who care about inclusion can reduce this drain on the energy

necessary to work for justice by being clear about three delusions which are

common but mostly unconscious among advocates for inclusion. When we re-

place these false and destructive beliefs with simpler expectations of decency

and working constructively in common, we will all be better able to live out the

real meaning of inclusion by honoring and growing from our shared struggle

with our diverse gifts, differences, and weaknesses.

Delusion 1: Inclusion means that everybody must love everybody

else or We must all be one big, happy family!

This delusion is at work when people who care about inclusion feel shocked

and offended to discover that other inclusion advocates dont really like one

another. Sometimes this delusion pushes people into pretending, or wanting

others to pretend, that real differences of opinion and personality dont exist or

dont really matter. The roots of this delusion may be in a desire to make up for

painful experiences by finally becoming part of one big happy family, where

there is continual harmony and peace.

The one big happy family delusion is the exact opposite of inclusion. The

real challenge of inclusion is to find common cause for important work that can-

not be done effectively if we isolate ourselves from one another along the many

differences of race, culture, nationality, gender, class, ability, and personality

that truly do divide us. Educating our children is one such common cause: it is

too important for us to give in to the many forces of divisiveness that surround it.

The reward of inclusion comes in the harvest of creative action and new under-

standing that follows the hard work of finding common ground and tilling it by

confronting and finding creative ways through real differences.

The one big happy family delusion destroys the possibilities for inclusion in a

complex community by seducing people into burying differences by denying

their significance or even their existence. People in schools or agencies or as-

sociations which promote this delusion lose vividness and energy because they

have to swallow the feelings of dislike and conflict they experience and deny

The Ethics of Inclusion - 1

the differences they see and hear. Denial makes a sandy foundation for inclu-

sive schools and communities.

Community grows when people honor a commitment to laugh, shout, cry, ar-

gue, sing, and scream with, and at, one another without destroying one another

or the earth in the process. We cant ever honestly celebrate diversity if we pre-

tend to bring in the harvest before we have tilled the ground together.

Delusion 2: Inclusion means everyone must always be happy and

satisfied or Inclusion cures all ills.

A group of good people came together to study inclusive community in an in-

tensive course. One person, Anne, angrily announced her dissatisfaction from

the groups first meeting on. She acted hostile to everyone else and to the

groups common project.

At first, the group organized itself around Annes dissatisfaction. A number of

members anguished over her participation. It was hard for the group to sustain

attention on anything for very long before the topic of how to satisfy Anne took

over. The group acted as if it could not include Anne unless she was happy.

And, they assumed, if they could not be an inclusive group (that is, make Anne

happy) they would be failing to live up to their values. Two other members

dropped out the group, frustrated by their inability to overcome the power of this

delusion and move on to issues of concern to them.

The group broke through when they recognized that true community includes

angry and anguished people as well as happy and satisfied people. After over-

coming the delusion of cure, the group gave Anne room to be angry and dissat-

isfied without being the focus of the whole group. Let out of the center of the

groups concern, Anne found solidarity with several other members, whom she

chose as a support circle for herself. In this circle of support her real pain

emerged as she told her story of being an abused child and a beaten wife. She

did not go home cured or happy, but she did find real support and direction for

dealing with the issues in her life.

The delusion that inclusion equals happiness leads to its opposite: a pseudo-

community in which people who are disagreeable or suffering have no place

unless the group has the magic to cure them. Groups trapped in this delusion

hold up a false kind of status difference that values people who act happy more

than people who suffer. This delusion creates disappointment that inclusion is

not the panacea.

The Ethics of Inclusion - 2

Real community members get over the wish for a cure-all and look for ways to

focus on promoting one anothers gifts and capacities in the service of justice.

They support, and often must endure, one anothers weaknesses by learning

ways to forgive, to reconcile, and to re-discover shared purpose. Out of this hard

work comes a measure of healing.

Delusion 3: Inclusion is the same as friendship or We are really all

the same

Friendship grows mysteriously between people as a mutual gift. It shouldnt be

assumed and it cant be legislated. But people can chose to work for inclusive

schools and communities, and schools and agencies and associations can

carefully build up norms and customs that communicate the expectation that

people will work hard to recognize, honor, and find common cause for action in

their differences.

This hard work includes embracing dissent and disagreement and sometimes

even outright dislike of one person for another. The question at the root of in-

clusion is not Cant we be friends? but, in Rodney Kings hard won words,

Can we all just learn to get along?

We cant get along if we simply avoid others who are different and include only

those with who we feel comfortable and similar. Once we openly recognize dif-

ference, we can begin to look for something worth working together to do. Once

we begin working together conflicts and difficulties will teach us more about our

differences. If we can face and explore them our actions and our mutual under-

standing will be enriched and strengthened.

To carry out this work, our standard must be stronger than the friendly feelings

that come from being with someone we think likes and is like us. To understand

and grow through including difference we must risk the comfortable feeling of

being just like each other. The question that can guide us in the search for bet-

ter understanding through shared action is not Do we like each other? but

Can we live with each other? We can discover things worth our joint effort

even if we seem strange to one another, even if we dislike one another, and,

through this working together, we can learn to get along.

The delusion of sameness leads away from the values of inclusion. It blurs

differences and covers over discomfort and the sense of strangeness or even

threat that goes with confronting actual human differences. Strangely, it only

when the presumption of friendship fades away that the space opens up for

friendship to flower.

The Ethics of Inclusion - 3

An ethic of decency and common labor

Inclusion doesnt call on us to live in a fairy tale. It doesnt require that we begin

with a new kind of human being who is always friendly, unselfish, and unafraid

and never dislikes or feels strange with anyone. We can start with who we are.

And it doesnt call for some kind of supergroup that can make everyone happy,

satisfied, and healed. We can start with the schools, and agencies, and asso-

ciations we have now.

The way to inclusion calls for more modest, and probably more difficult,

virtues. We must simply be willing to learn to get along while recognizing our

differences, our faults and foibles, and our gifts.

This begins with a commitment to decency: a commitment not to behave in

ways that demean others and an openness to notice and change when our be-

havior is demeaning, even when this is unintentional. This ethical boundary

upheld as a standard in human rights tribunals around the globe defines the

social space within which the work of inclusion can go on.

This work calls on each of us to discover and contribute our gifts through a

common labor of building worthy means to create justice for ourselves and for

the earth through the ways we educate each other, through the ways we care

for one anothers health and welfare, and through the ways we produce the

things we need to live good lives together.

In this common labor we will find people we love and people we dislike; we

will find friends and people we can barely stand. We will sometimes be aston-

ished at our strengths and sometimes be overcome by our weaknesses.

Through this work of inclusion we will, haltingly, become new people capable of

building new and more human communities.

The Ethics of Inclusion - 4

You might also like

- What Would A Satisfactory Moral Theory Be Like - JAT PDFDocument10 pagesWhat Would A Satisfactory Moral Theory Be Like - JAT PDFpurchases100% (1)

- Aspects of Community Community As OpennessDocument11 pagesAspects of Community Community As OpennessMariacris CarniceNo ratings yet

- SolidarityDocument4 pagesSolidarityBernadeth A. UrsuaNo ratings yet

- Wellness WednesdayDocument3 pagesWellness Wednesdayapi-376517437No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledKeshav GuptaNo ratings yet

- Makna Menjadi Manusia SeutuhnyaDocument4 pagesMakna Menjadi Manusia SeutuhnyaLidya RahmadhaniNo ratings yet

- Manila - Written Activity 2Document4 pagesManila - Written Activity 2Julia ManilaNo ratings yet

- Why Is It Important To Find Common With Someone Who Is Different From YouDocument2 pagesWhy Is It Important To Find Common With Someone Who Is Different From YouANASTASIA EVANGELINANo ratings yet

- UTS - TP (Midterm)Document5 pagesUTS - TP (Midterm)CJ AdvinculaNo ratings yet

- I, You and We: Respecting Similarities and DifferencesDocument15 pagesI, You and We: Respecting Similarities and DifferencesKenneth AranteNo ratings yet

- BATAUSA_023933Document5 pagesBATAUSA_023933Batausa Christine May L.No ratings yet

- Why Talking To Others Is Not The Solution To LonelinessDocument4 pagesWhy Talking To Others Is Not The Solution To LonelinessDharshini annamalaiNo ratings yet

- Service:: Shifting The Emphasis From Getting To GivingDocument9 pagesService:: Shifting The Emphasis From Getting To GivingFanueal SamsonNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Introduction of The Philosophy of The Human PersonDocument15 pagesDepartment of Education: Introduction of The Philosophy of The Human PersonMissy Lumpay De AsisNo ratings yet

- Discussion - FreewriteDocument2 pagesDiscussion - FreewritekalonzofrankNo ratings yet

- The Power of Empathy in Building A Compassionate SocietyDocument1 pageThe Power of Empathy in Building A Compassionate SocietyACHIRA DANIEL RAYNENo ratings yet

- CWTSDocument2 pagesCWTSRolean Grace Cabayao SangariosNo ratings yet

- Emotional Competency - CommunityDocument3 pagesEmotional Competency - CommunityCarl D'SouzaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8Document10 pagesChapter 8Mohd Hafiy SyazuanNo ratings yet

- The Power of Empathy Building Bridges of UnderstandingDocument1 pageThe Power of Empathy Building Bridges of UnderstandingPepe DecaroNo ratings yet

- Lisa Renee Crisis in ConsciousnessDocument7 pagesLisa Renee Crisis in Consciousnessbj ceszar100% (1)

- The Power of Compassion in A Divided WorldDocument2 pagesThe Power of Compassion in A Divided World6A DS //No ratings yet

- Listening 2Document2 pagesListening 2Lorena UribeNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Public Narrative Worksheet 2019Document7 pagesModule 3 Public Narrative Worksheet 2019tejasrkm1No ratings yet

- Allyship and SolidarityDocument3 pagesAllyship and SolidarityTanishka vermaNo ratings yet

- Santillan BSN 1E EssayDocument2 pagesSantillan BSN 1E EssayLouie Gene SantillanNo ratings yet

- Being Assertive: Finding the Sweet-Spot Between Passive and AggressiveFrom EverandBeing Assertive: Finding the Sweet-Spot Between Passive and AggressiveRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- FacebookaDocument2 pagesFacebookasarcozy922No ratings yet

- Living Oneness Study GuideDocument198 pagesLiving Oneness Study GuideyashyiNo ratings yet

- The Power of EmpathyDocument2 pagesThe Power of Empathyee9987No ratings yet

- Real Change: Mindfulness to Heal Ourselves and the WorldFrom EverandReal Change: Mindfulness to Heal Ourselves and the WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- Ensayo SocioDocument4 pagesEnsayo SocioChristian RiveraNo ratings yet

- We Will Not Cancel Us: And Other Dreams of Transformative JusticeFrom EverandWe Will Not Cancel Us: And Other Dreams of Transformative JusticeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (26)

- The Power of Empathy in Building Stronger CommunitiesDocument2 pagesThe Power of Empathy in Building Stronger Communitiesalberts.sarkansNo ratings yet

- Prosocial BehaviorDocument37 pagesProsocial Behaviorxerah0808No ratings yet

- Helpful Tips To Start Building A Diverse CommunityDocument3 pagesHelpful Tips To Start Building A Diverse CommunityNanik Lestari NingsihNo ratings yet

- CatchUp PeaceEducationQ4Session1Document17 pagesCatchUp PeaceEducationQ4Session1Jonna RizaNo ratings yet

- The family is the building block of societyDocument2 pagesThe family is the building block of societyjustindeperalta05No ratings yet

- Summary of Daring Greatly: by Brene Brown | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of Daring Greatly: by Brene Brown | Includes AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Letter EssayDocument5 pagesLetter Essayjosephmainam9No ratings yet

- For Week 15Document26 pagesFor Week 15Michael QuidorNo ratings yet

- In Our Families and Faith CommunitiesDocument1 pageIn Our Families and Faith CommunitiesroshelleNo ratings yet

- Leading Together: How Brave, Honest Conversations can Transform Our Lives, Organizations, and CommunitiesFrom EverandLeading Together: How Brave, Honest Conversations can Transform Our Lives, Organizations, and CommunitiesNo ratings yet

- Answer The QuestionsDocument2 pagesAnswer The QuestionsLê NguyệtNo ratings yet

- The Power of EmpathyDocument2 pagesThe Power of EmpathyerkanaptiNo ratings yet

- Sharing and CaringDocument2 pagesSharing and Caringayoub.salhi.as7No ratings yet

- Second Essay 2Document2 pagesSecond Essay 2Yasmiin MansooriNo ratings yet

- An Overview in Solidarity: by Kehm Angel SocayreDocument2 pagesAn Overview in Solidarity: by Kehm Angel SocayreKehm SocayreNo ratings yet

- My ProjectDocument4 pagesMy ProjectA Facilitator ProNo ratings yet

- The Unicorn FactoryDocument50 pagesThe Unicorn FactoryasovarosiNo ratings yet

- The Power of Empathy in Building Stronger CommunitiesDocument1 pageThe Power of Empathy in Building Stronger CommunitiesmonkeyboppopNo ratings yet

- Usct Ipu BCE ENGLISHDocument7 pagesUsct Ipu BCE ENGLISHmk.manishkhatreeNo ratings yet

- 1 - Poverty RedefinedDocument1 page1 - Poverty RedefinedShristee ManandharNo ratings yet

- 0361 ActivityDocument4 pages0361 ActivityLance TizonNo ratings yet

- Lesson9-INTERSUBJECTIVITY (1)Document58 pagesLesson9-INTERSUBJECTIVITY (1)yvanoxgamerNo ratings yet

- Dwight EisenhowerDocument21 pagesDwight Eisenhowerapi-26406010No ratings yet

- Pub2601 Assignment 2Document4 pagesPub2601 Assignment 2luciamashiane2No ratings yet

- A Business Ethic Theory of WhistleblowingDocument14 pagesA Business Ethic Theory of WhistleblowingIlham NurhidayatNo ratings yet

- Catanduanes - ProvDocument2 pagesCatanduanes - ProvireneNo ratings yet

- MIPD 160112 ReportDocument2 pagesMIPD 160112 ReportDevan PatelNo ratings yet

- Personal Status Legal Personality and Capacity ReportDocument34 pagesPersonal Status Legal Personality and Capacity ReportRussel SirotNo ratings yet

- A. Manifest Destiny: Chapter 13: The Impending Crisis I. Looking WestwardDocument6 pagesA. Manifest Destiny: Chapter 13: The Impending Crisis I. Looking WestwardSchool AccountNo ratings yet

- John Zvesper - The Utility of Consent in John Locke's Political PhilosophyDocument13 pagesJohn Zvesper - The Utility of Consent in John Locke's Political PhilosophyLuiz Paulo FigueiredoNo ratings yet

- Buenavista Central Elementary SchoolDocument2 pagesBuenavista Central Elementary Schoolanon_108827268No ratings yet

- Ahmed DhawDocument3 pagesAhmed DhawMahmoudNo ratings yet

- COA ResearchDocument38 pagesCOA ResearchCleoNo ratings yet

- Issues and Controversies About The Heroism of Dr. Jose RizalDocument14 pagesIssues and Controversies About The Heroism of Dr. Jose RizalKian Bartolome75% (4)

- Print Edition: 05 January 2014Document21 pagesPrint Edition: 05 January 2014Dhaka TribuneNo ratings yet

- Polity - Revision ClassDocument60 pagesPolity - Revision ClassjoshuaNo ratings yet

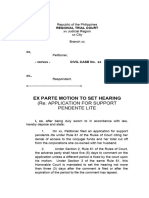

- Ex-Parte-Motion-To Set HearingDocument3 pagesEx-Parte-Motion-To Set HearingSoc PriNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Policies and Procedures Manual For The Public ServiceDocument163 pagesHuman Resource Policies and Procedures Manual For The Public ServiceAMANANG'OLE BENARD ILENYNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Tanyag V Gabriel DigestDocument3 pagesHeirs of Tanyag V Gabriel DigestMikkolet100% (1)

- SPIODocument31 pagesSPIOrchowdhury_10No ratings yet

- Kejatuhan Daulah UthmaniyyahDocument31 pagesKejatuhan Daulah Uthmaniyyahmohd.malkiNo ratings yet

- COF 2 1000 10N FrictioncoeffvsCycleDocument68 pagesCOF 2 1000 10N FrictioncoeffvsCyclejituniNo ratings yet

- Women Empowerment - Chapter 8Document102 pagesWomen Empowerment - Chapter 8EbinNo ratings yet

- Sexual HarassmentDocument19 pagesSexual HarassmentSteph Corpuz0% (1)

- E0363 PDFDocument29 pagesE0363 PDFAnjali KilledarNo ratings yet

- Final CCF SubmissionDocument24 pagesFinal CCF SubmissionIntelligentsiya HqNo ratings yet

- Indian Judiciary ReportDocument18 pagesIndian Judiciary ReportLö Räine AñascoNo ratings yet

- Cadre Review Trade Notice NO 01/2014-CC (LZ) DATED 08.10.2014Document2 pagesCadre Review Trade Notice NO 01/2014-CC (LZ) DATED 08.10.2014SUSHIL KUMARNo ratings yet

- Defense Opening StatementDocument2 pagesDefense Opening StatementParimal KashyapNo ratings yet

- Advocates Act: The Backbone of Legal ProfessioDocument4 pagesAdvocates Act: The Backbone of Legal ProfessioSHIVANSHI SHUKLANo ratings yet

- Grade 4 ST Joan 2 4THDocument12 pagesGrade 4 ST Joan 2 4THChristina Aguila NavarroNo ratings yet

- Lea For PRC LicenseDocument17 pagesLea For PRC LicenseArnold Zabate AparicioNo ratings yet