0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

175 viewsCessm 1

CESSM-1

Uploaded by

msiddiq1Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online on Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

175 viewsCessm 1

CESSM-1

Uploaded by

msiddiq1Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online on Scribd

You are on page 1/ 75

THE INSTITUTION OF CIVIL ENGINEERS

CESMM3 HANDBOOK

Aguide to the financial control of contracts

using the Civil Engineering Standard Method of

Measurement

MARTIN BARNES

_

1 THOMAS TELFORD, LONDON, 1992

Published fortheinsti

House, 1 Heron Quay,

ion of Civil Engineersby Thomas Telford Services Ltd, Thomaa Telford

‘ondan £1440,

Firstedition 1986

Socondecition 1992

‘Terms used n this book include terms which are definedin the CE Concitions of Contract and in

the Givi Engineering Standard Method of Measurement, hird edition (CESNIM, third edition).

These termsare printed with intial lettersin eapitalsto indicate that the defined mooning s

intended. Paragraph numbers and class letters refer those inthe CESMM, third ection: rules

inthe CESMM, thirdedition, are referrodto by their laee and number. The interpretation e! the

ICE Conditions of Contract andiof the Civi/ Engineering Standerd Method of Measurersent tied

dition, offeredin this Bookis not an official interpretation and should not be used as euch inthe

settlement of disputes arising in the course of civil engineering contracts,

sments made or opinions expressed herein is publishedon the

tunderstanding thatthe authori solely responsibie forthe opinions expreseedin itandthatits,

Publication does not necessarily imply that such statements andor opinions are o refiectthe

views or opinions of ICE Councilor ICE commito

© The institution of Civil Engineers 1932

ahLitey Eatoguing nPubcston Dat

tet eyitam civsnamitein ary ormerbyanymaane learns chi, Stang rcaages et

towne writen parmisiosbangottartc omega

“Trpenty Opuehegaies Landon

‘eed wthowrdin ret Birt Buta Tarr, Sererat

FOREWORD

By the President of the Institution of Civil Engineers

When the Civil Engineering Standard Method of Measurement

(CESMM) was first published in 1976, the practice of preparing and

using bills of quantities on civil engineering projects was

revolutionized. The practical structure which the CESMM

introduced and the thorough analysis upon which its details were

based led to its rapid and effective adoption. It was copied widely and

influenced quantity surveying practice in many sectors beyond civil

engineering. Martin Barnes, who designed and draughted the

CESMM, wrote a handbook to go with it.

Fifteen years later, it isa pleasure to welcome this third edition of the

handbook, published to coincide with publication of the third edition

ofthe CESMM itself.

Much of the original text is still here and will continue to instruct

young engineers coming freshly to the use of bills of quantities. The

new material explaining the new features of CESMM3 will help to

ensure the smooth and uncontentious adoption of this method of

measurement in the tradition of its predecessors.

Mastering of financial control is an essential skill for the rounded civil

engineer. I commend Martin Barnes’ CESMM3 handbook as an

important help in acquiring the skill

Robin Wilson, FEng, FICE

London, 1991

PREFACE

This is the third edition of the handbook for use alongside the Civil

Engincering Standard Method of Measurement, third edition

(CESMM) itself. In content it differs from the second only in that it

explains the changes and additions made in producing CESMM3,

‘There are a number of minor improvements and detailed changes

which are introduced either to keep CESMMG up to date or to

eliminate difficulties which have been experienced in practice. A

significant addition is the new class Z which covers building work

incidental to civil engineering projects.

acknowledge the help of various members of the Institution of Civil

Engincers specialist committees who have helped with advice, and

pay my thanks to the staff of Thomas Telford Services for their

patience and assistance.

Jacknowledge principally the help of my colleague John McGee, who

has contributed a high proportion of the text for the changes mad

this third edition of the handbook.

Martin Barnes

London, 1991

Section 1.

Section2.

Section3.

Section 4,

Sections.

Section6.

Section?

Section 8.

Index.

Definitions

General principles

‘Application of the Work Classi

Coding and numbering of items

Preparation of the Bill of Quantities

Completion and pricing of the Bill of Quantities bya tenderer

Method-Related Charges

Work Classifi

Generalitems

Groundinvestigation

Geotechnical and other specialist processes

Demolition andsite clearance

Classe: Earthworks

Class: Insituconcret

GlaseG: Concrete ancillaries

ClassH: Precaetconcrete

Classi: Pipework—pipes

Class Ji Pipework—fittings andvalves,

Class: Pipework—manholes and pipeworkancilaries

Glass: Pipework—supports and protection ancillariesto

laying and excavation

Clase M: Structural metalwork

Class: Miscellaneous metalwork

Class0: Timber

ClassP: Piles

Class; Pilingencillaies

Class: Roads andpavings

Clases: Reitrack

ClassT: Tunnels

lass: Brickwork blockworkandmasonry

Glasses Vand W: Painting and Waterprooting

ClassX: Miscellaneous work

Class: Seworandwatermain renovation andaneillary works

Class2: Simple building works incidentalto civil engineering works

137

14

uaz

45

159

169

m

178

181

186

197

194

an

25

225

237

INTRODUCTION

Financial control means control of money changing hands. Since

money almost always changes hands in the opposite direction from

thatin which goods or services are supplied, it can be considered as the

control of who provides what and at what price. This thought

establishes a priced bill of quantities as the central vehicle for the

financial control of a civil engineering contract. The Bill of Quantities

is the agreed statement of the prices which will be paid for work done

by the Contractor for the Employer and it shares with the Drawings

and the Specification the responsibility for defining what has been

agreed shall be done.

Control is usually based on a forecast. The difficulty of controlling

something is proportional to the difficulty of predicting its behaviour.

The points, finer and coarser, of the financial control of civil

engineering contracts revolve around the difficulty the Employer has.

in forecasting and defining to a Contractor precisely and immutably

what he is required to do, and the difficulty the Contractor has in

forecasting precisely what the work will cost. To achieve effective

control it is necessary to limit these difficulties as much as possible

within reasonable limits of practicality. This means using as much

precision as possible in defining the work to the Contractor and in

enabling him to forecast its cost as precisely as possible. These are the

‘essential fanctions of bills of quantities. It is the essential function of a

method of measurement to define how bills of quantities should be

compiled so that they serve these two essential functions.

itis clear from this consideration that a bill of quantities works bestifit

is a model in words and numbers of the work in a contract. Such a

model could be large, intricately detailed and reproducing the

Workings ofthe rel thing in an enact representation. Alternatively. i

could be as simple as possible while still reproducing accurately those

aspects of the behaviour of the original which are relevant 10 the

Purposes for which the model is constructed

The first purpose of a bill of quantities is to facilitate the estimating of

the cost of work by a contractor when tendering. Considered as a

model, it should therefore comprise a list of carefully described

Parameters on which the cost of the work to be done can be expected

to depend. Clearly these parameters should include the quantities of

the work to be done in the course of the main construction operations.

There is no point in listing those parameters whose influence on the

total cost of the work is so small as to be masked by uncertainty in the

forecasting of the cost of the major operations.

Other points of general application emerge from this principle of

cost-significant parameters. The separation of design from

construction in civil engineering contracts and the appointment of

INTRODUCTION

CESMM3 HANDBOOK

contractors on the basis of the lowest tender are the two features ofthe

system which make ie essential for a good set of parameters to be

passed to contractors for pricing, and for a good set of priced

parameters to be passed back to designers and employers. Only then

can they design and plan with the benefit of realistic knowledge of

how their decisions will affect construction costs. The less contractual

pressures cause distortion of the form of the prices exchanged from the

form of actual construction costs the better this object is served. It is

very much in the interests of employers of the civil engincering

industry, whether they are habitually or only occasionally in that role,

that the distortion of actual cost parameters should be minimized in

priced bills of quantities.

‘An employer's most important decision is whether to proceed to

construction or not. This decision, if it is not to be taken wrongly,

must be based on an accurate forecast of contract price. Only if a

designer has a means of predicting likely construction cost can such a

forecast be achieved. The absence of cost parameters which are

sensitive to methods and timing of construction has probably caused

as much waste of capital as any other characteristic of the civil

‘engineering industry. It has sustained dependence on the view that

quantity is the only cost-significant parameter long after the era when

ithad some veracity. Generations of contractors, facing drawings first

when estimating, have found themselves marvelling at the

construction complexity of some concrete shape which has apparently

been designed with the object of carrying loads using the minimum

volume of concrete. That it has required unnecessary expense in

constructing the formwork, in bending and placing the reinforcement

and in supporting the member until the concrete is cured often appears

to have been ignored.

A major aspect of financial control in civil engineering contracts is the

control of the prices paid for work which has been varied. Varying

work means varying what the Contractor will be required to do, not

varying what has already been actually done. Having once been built,

workis seldom varied by demolition and reconstruction; the difficulty

of pricing variations arises because what gets built is not what the

Contractor originally plans to build. If the work actually buile were

that shown on the original Drawings and measured in the original Bill

of Quantities, the prices given would have to cover all the intricate

combinations of costs which produce the total cost the Contractor wi

actually experience. This would inchide every hour of every man’s

paid time — his good days, his bad days and the days when what he

does is totally unforeseen. It would include every tonne or cubic metre

of material and the unknown number of bricks which get trodden into

the ground, It would include every hour of use of every piece of plant

and the weeks when the least popular bulldozer is parked in a far

comer of the Site with a track roller missing. The original estimate of

the total cost of this varied and unpredictable series of activities could

reasonably only be based on an attempt to foresee the level of

resources required to finish the job, with many little overestimates

balancing many little underestimates. Changes to the work from that

originally planned may produce changes to total cost which are

unrelated to changed quantities of work. They are less likely to

produce changes in cost which are close to the changed valuation if

value is taken to be purely proportional to quantity of the finished

work. Where there are many variations to the work, the act of faith

embodied in the original estimate and tender can be completely

|

INTRODUCTION

undermined, The Contractor may find himself living from day to day

doing work the costs of which have no relationship to the pattern

originally assumed,

‘That cost is difficult to predict must not be allowed to obscure the fact

that financial control depends on prediction. Ifehe content of the work

cannot be predicted the conduct of the work cannot be planned. Ifthe

work cannot be planned its cost can only be recorded, not controlled.

It must also be accepted that valuation of variations using only unit

prices in bills of quantities is an unrealistic exercise for most work and

does little to restore the heavily varied project to a climate of effective

financial control. Only for the few items of work whose costs are

dominated by the cost of a frecly available material is the quantity of

work a realistic cost parameter. It follows that employers are well

served by the civil engineering industry only if contractors are able to

plan work effectively: to select and mobilize the plant and labour

teams most appropriate to the scale and nature of the expected work

and to apply experience and ingenuity to the choice of the most

appropriate methods of construction and use of temporary works.

‘That this type of planning is often invalidated by variations and delays

has blunted the incentive of contractors to plan in the interests of

economy and profit. The use of over-simplified and unrealistic

parameters for pricing variations has led to effort being applied to the

pursuit of payment instead of to the pursuit of construction efficiency.

In a climate of uncertainty brain power may be better applied to

maximizing payment than to minimizing cost.

Mitigation of this problem lies in using better parameters of cost as the

basis of prices in bills of quantities. It would be ideal ifthe items in a

bill were a set of parameters of total project cost which the Contractor i

had priced by forecasting the cost of each and then adding a uniform

margin to allow for profit. Then, if parameters such as a quantity of

work or a length of time were to change, the application of the new

parameters to each of the prices would produce a new total price

bearing the same relationship to the original estimated price as the new

total cost bore to the original estimated cost. The Employer would

then pay for variations at prices which were clearly related to tender

prices and the derivation of the adjusted price could be wholly

systematic and uncontentious, This ideal is unobtainable, but it is

brought closer as bills of quantities are built up from increasingly

realistic parameters of actual construction costs.

From the cash flow point of view there are also advantages in sticking

to the principle of cost parameters. The closer the relationship

tween the pattern of the prices in a bill of quantities and the pattern |

ofthe construction costs, the closer the amount paid by the Employer

to the Contractor each month is to the amount paid by the Contractor

i cach month to his suppliers and sub-contractors. The Contractor's

i cash balance position is stabilized, only accumulating profit or loss

‘when his operations are costing less or more than was estimated.

Since much of the Contractor's turnover is that of materials suppliers

and sub-contractors with little added value, stability and predictability

of cash-flow has an importance often not appreciated by employers

i and engineers, Contractors are in business to achieve a return on their

Resources of management and working capital — a return which is

seldom related closely to profit on turnover. Predictability of the

CESMM3 HANDBOOK

amount of working capital required is a function of prompt and

cost-related payment from the Employer another benefit of using

pricing parameters closely related to parameters of construction cost.

In the detailed consideration of the financial control of civil

engineering contracts and of the use for the purposes of control of

CESMM3 which follows in this book, the application ofthe priniple

set down here is recognized. It should not be thought that the close

attention to the affairs of contractors implied by this principle allows

them a partisan advantage over employers.

An employer’s interest is best served by a contractor who is able to

base an accurate estimate on a reliable plan for constructing a clearly

defined project, and who is able to carry out the work with a

continuing incentive to build efficiently and economically despite the

assaults of those unforeseen circumstances which characterize civil

engineering work. Confidence in being paid fully, promptly and

fairly will lead to the prosperity of efficient contractors and to the

demise of those whose success depends more on the vigour with

which they pursue doubtful claims,

As Louis XIV's department of works was recommended in 1683, as a

result of what may have been the first government enquiry into the

financial control of civil engineering contracts: ‘In the name of God:

re-establish good faith, give the quantities of the work and do not

refuse a reasonable extra payment to the contractor who will falfil his

obligations.”

CESMM3 sets out to serve the financial control of civil engineering

contracts and in doing so finds itself at one with this advice. This book

elaborates on and illustrates the use of CESMM3. To facilitate

‘cross-reference its sections correspond to those of CESMM3 itself.

The first edition of the Civil Engineering Standard Method of

‘Measurement was in use for a few months less than ten years, The

changes between the first and second editions were many, The layout

of what were first called notes were changed. They were replaced by

rules, which were categorized and classified to make reference to them

easier and interpretation more straightforward. How the rules are

intended to be used is explained in detail in Section 3.

A new class Y was introduced in the second edition to cover sewer

renovation work. This has been expanded in CESMM3 to include

‘water main renovation work. CESMM3 introduces a brand new class

Z for simple building works incidental co civil engineering works.

Classes Y and Z are explained in detail in Section 8 as are the other

changes in CESMM3.

The principles of the Civil Engineering Standard Method of

‘Measurement were not tampered with in producing the second and

third editions. The innovations which the Civil Engineering Standard

Method of Measurement contained, such as coded and tabulated

measurement rules, simplified itemization and Method-Related

Charges, were all retained unchanged. Fifteen years of use had proved

their worth.

Many of the changes between the first and third editions are detailed

refinements. The purposes behind the more significant of these is

INTRODUCTION

explained in che technical sections of this book. Each section of this

book concludes with schedules of the principal changes between the

first and second and and the second and third editions of the Civil

Engineering Standard Method of Measurement. These schedules do

not include the smaller textual changes.

For brevity, the third edition of the Civil Engineering Standard

Method of Measurement is referred to throughout this book, asin its

title, as CESMM3.

SECTION 1. DEFINITIONS

The definitions given in CESMM3 are intended to simplify its text by

enabling the defined words and expressions to be used as

abbreviations for the full definitions. Where the same words and

expressions arc used in bills of quantities they are taken to have the

same definitions.

There are two changes to the definitions in CESMM3 concerning

paragraphs 1.2 and 1.15. These have been updated to tie in with the

ICE Conditions of Contract, sixth edition and European procurement

law.

It is helpful to use capital initial letters in bills of quantities for any of

the terms defined in CESMM3 or the Conditions of Contract which

themselves have capital initial letters. This leaves no doubt that the

defined meaning is intended.

The definition of ‘work’ in paragraph 1.5 is important. Work in

CESMM3 is different from the three types of ‘Works’ defined in

clause 1 of the Conditions of Contract. It is a more comprehensive

term and includes ail the things the Contractor does. Itis not confined

to the physical matter which he is to construct. For example,

maintaining a piece of plant is work as defined in CESMM3, but

‘would not be covered by any of the definitions of Works in the

Conditions of Contract.

‘The expression ‘expressly required’, defined in paragraph 1.6, is very

helpful in the use of bills of quantities. It is used typically in rule M15

of class E which says that the area of supports left in an excavation

which is to be measured shall be that area which is ‘expressly required’

tobeleft in. The corollary to this rule is that, if the Contractor chooses

toleave in supports other than at the Enginccr’s request, theit arca will

not be measured and the Contractor will receive no specific payment

forit, Knowing this, the Contractor will leave the supports in only ifit

is in his own interests to do so. However, if the Engineer orders the

supports to be left in, itis because it is in the Employer's interest that

they should be left in, and the Employer will then pay for them at the

bill rate for the appropriate items (E 5 7-8 0).

Rules in CESMM& use ‘expressly required’ wherever it is intended

that the Engineer should determine how much work of a particular

type is to be paid for. Usually this is work which could be either

temporary — done for the convenience of the Contractor — or

permanent — done for the benefit of the Employer. Expressly

Tequired also means ‘shown on the Drawings’ and ‘described in the

Specification’ so that it is applicable if intentions ate clear before a

contract exists.

DEFINITIONS

CESMM3 HANDBOOK

Rule MS of class E is an example which refers to excavation in stages.

‘The Contractor may decide to excavate in stages for his own economy

and convenience, or the Engineer may require excavation to be cartied

‘out in stages for the benefit of the completed Works. The use of the

term ‘expressly required’ in rule M5 of dass E and in other places

draws attention to the fact that the work referred to, when done on the

Site, will not necessarily be paid for asa special item unless itis a result

of work of the type described having been expressly required.

It is prudent for Engineers and Contractors to make sure that work

done on the Site which may or may not be measured is carefully

recorded between the Contractor and the Engineer's Representative

0 that it can be agreed whether work is or is not expressly required.

Preferably these agreements should be reached before work is carried

out.

‘The definition of ‘Bill of Quantities’ in paragraph 1.7 establishes that

the bill does not determine either the nature or the extent of the work

in the Contract. The descriptions of the items only identify work

which must be defined elsewhere. ‘This definition is important as it

directly implies the difference between the status of the Bill of

Quantities under the ICE Conditions of Contract and under the

building or JCT conditions of contract.* In the building contract the

bill of quantities is the statement of what the Contractor has to do in

terms of both definition and quantity. This difference from civil

engineering practice is significant, There is no reason to lessen this

difference. Both the ICE Conditions of Contract and CESMM3 rely

heavily on it. The estimator pricing a civil engineering bill of

quantities will derive most of the information he needs in order to

estimate the cost of the work from the Drawings nd Specification. He

will use the bill as a source of information about quantities and as the

vehicle for offering prices to the Employer. The main vehicles for

expressing a design and instructing the Contractor what to build

remain the Drawings and Specification.

The definitions of four surfaces in paragraphs 1.10-1.13 are used to

avoid ambiguity about the levels from which and to which work such

as excavation is measured. When the Contractor first walks on to the

Site, the surface he sees is the Original Surface. During the course of

the work he may excavate to lower surfaces, leaving the surface in its

final position when everything is finished. Between the Original and

Final Surfaces he may do work covered by more than one bill item, as

for example in carrying out general excavation before excavating for

pile caps. The surface which is left after the work in one bill item is

Ennished is the Excavated Surface for that item, and the Commencing

Surface for the work in the next item if there is one. ‘Final Surface’ is

defined as the surface shown on the Drawings at which excavation is

to finish, This is so that any further excavation to remove soft spots

can be referred to as ‘excavation below the Final Surface’. Fig. 1

illustrates the use of the four definitions of surface.

‘The words of definitions 1.12 and 1.13 were changed in the second

edition. No change to the effect of the definitions was intended, butit

had become apparent that some compilers of bills of quantities were

“Joint Contracts Tribunal. Standard form of building contrat. Private edition with

‘quantities, Royal Istcute of British Architects, London, 1980.

-e___—_—

DEFINITIONS.

taking the implied instructions in paragraph 5.21 and the ewo

definitions further than was necessary as regards measurement of

excavation of different materials

It was never intended that the Commencing and Excavated Surfaces

of layers of different materials within one hole to be excavated should

be identified separately as regards Commencing and Excavated

Surfaces. For example, if excavation of a hole involved excavation of a

layer of topsoil, then ordinary soft material, then a band of rock, the

‘Commencing Surface forall three items could be properly regarded as

the Original Surface, and the Excavated Surface for all three items

could be properly regarded as the Final Surface. The maximum depth

stated in the item descriptions for al three items would be the range of

those stated in the class E table in which the maximum depth of the

complete hole occurred, irrespective of the thickness of each layer of

material or of the sequence within the total depth in which they

occurred. Fig. 2illustrates this point. This produces item descriptions

which can occasionally seem peculiar such as ‘Excavate topsoil

maximum depth 5-10 m’, This description seems less peculiar as soon

as itis understood that it means ‘Excavate the topsoil encountered in

the course of digging a hole whose maximum depth is between 5 and

10m’,

Fig, 1.Aplicaton of the dations

Sora ceen ee, fine for surooos gue

oar pagans 10-1 1 The Bxcovated

Sitece lor ong tor becomes the

‘Commencing Surface for the next

7 fam excoatn massed

| ihre arene stage fase

ase ieeeecm nitty porepash S21

a

ena

. rane

ei ren

i

Final Surace anc

Exewateg Surece

fritem

Fig. 2. Three items are required for

commencing this excavation, All can be described

be {8 maximum depth 10-15 m”

Definition rules 1.12 and 1.13 da not

oor require intermediate surfaces to be

identified

(ther salt mata

Exeavaieg Suttacd

CESMM3 HANDBOOK

‘Schedule of changes in CESMM2

1, Paragraph 1.1. Makes the

definitions apply to terms used in

bili of quantities.

2, Paragraph 1.2, Refers to the latest

edition of the ICE Conditions of

Contract

3. Peragraphs 1.12 and 1.19. Revised

10 eliminate the identification of

surfaces between different

‘materials in excavation.

Schedule of changes in CESMM3.

1. Paragraph 1.2. Refers to the ICE

Conditions of Contract, sixth

edition

2, Paragraph 1.16 Defines references

to Brtish Standards as references

to equivalent standards in the

European Community

40

‘The changes to definitions 1.12 and 1.13 mean that item descriptions

will no longer be cluttered with unnecessary identifications of

Commencing and Excavated surfaces, Such phrases as ‘Excavate

topsoil, Excavated Surface underside of topsoil’ or ‘Excavated rock,

Commencing Surface underside of soft material’ should no longer

appear. They were never necessary: the new wording of definitions

1.12and 1.13 makes this more obvious.

Definition 1.14 provides a simple abbreviation for phrases like

‘exceeding 5 m but not exceeding 10 m’. In bills compiled using

CESMM3 this phrase should be abbreviated to ‘5-10 m’. This con-

vention does not work ifranges are defined with the larger dimension

first, ¢.g. 10-5 m means nothing.

Definition 1.15 has been introduced in CESMM3 to take account of

developments in European law which affects contracts awarded by

public authorities within the United Kingdom.

‘The main factor in this was an Irish case [Commission of the European

Communities (supported by the King of Spain, intervenor) v Ireland,

Building Law Reports, vol. 44P1] in which the court declared that a

specification which called for materials to comply with an Irish

Standard was illegal. The court ruled that this was contrary to Article

30 of the Treaty of Rome and that the specification should have called

for the materials to be the ‘Irish Standard or equivalent’

This decision only affects contracts let by government agencies and

local authorities at the present time. However, these contracts

represent a substantial proportion of the UK civil engineering

workload and the coverage will extend further if the present draft

Excluded Sectors Directive is implemented.

a |

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

SECTION 2. GENERAL PRINCIPLES

‘The general principles in CESMMG3 are a small group of rules and

statements which set the scene for the detailed rules which follow.

Where they are expressed in mandatory terms they are rules of full

significance; where they are expressed in less than mandatory terms

they give background to help interpretation of the rules.

Paragraph 2.1 points out that CESMMS is intended to be used in

conjunction with the ICE Conditions of Contract, sixth edition and

only in connection with civil engineering works or simple building

works incidental to civil engineering works. This is a change from the

second edition which has been achieved through the introduction of a

new class Z. Class Z sets out rules for measuring simple building

works which are incidental to civil engineering works. CESMM3 can

be used with other conditions of contract which invest the Bill of

Quantities and the method of measurement with the same functions.

The co-ordination of the provisions of CESMM3 with other

conditions of contract must then be checked carefully before tenders

are invited and appropriate amending preamble clauses included in the

bill. The standard conditions of contract for ground investigation* are

referred to in the preface of CESMM3 but not specifically in the

‘general principles. Where CESMM3 is used for ground investigation

work, the clause numbers can be left as printed because the clauses

referred to in CESMM3 have the same numbers in both contracts.

In several places CESMM3 refers to individual clauses of the

Conditions of Contract. Any change to the significance of these

references should be checked when CESMMS is used in conjunction

with other conditions of contract or with supplementary conditions to

the Conditions of Contract. For example, rule C1 of class A of

CESMM3 limits the coverage of the insurance items included in class

Ato the minimum insurance requirements stated in clauses 21 and 23

ofthe Conditions of Contract. Itis therefore essential to use additional

specific items to cover any other requirements for insurance which

may be applied in particular contracts.

Provided that the responsibilities of the parties are similar and that the

status of the Bill of Quantities and method of measurement are

similar, CESMM3 can be used with other conditions of contract and

for work which is not civil engineering or measured in class Z. In such

ases it will usually be necessary to give amending preambles. There is

clearly no point in using CESMM3 if the work in a contract is not

Principally made up of the things which CESMM3 covers.

ee eee EEE Ee EEE eee ee eee eee eee eee eee

‘MCE conditions of contac for ground investigation. Thomas Telford, London, 1983.

u

scans

CESMM3 HANDBOOK

12

Paragraph 2.2 deals with the problem of identifying and measuring

work which is not covered by CESMM3, either because it is work

outside the range of work which CESMM3 covers or because it is

work not sufficiently common to justify its measurement being

standardized in CESMM3. Work which is not covered by CESMM3

includes mechanical or electrical engineering works or building works

other than those covered by class Z. No rules are given for

itemization, description or measurement of such work but principles

are given which should be followed. Ifthe work needs to be measured,

that is to say a quantity calculated, any special conventions for so

doing which it is intended shall be used should be stated in the

Preamble to the bill.

The last sentence of paragraph 2.2 says that non-civil engineering

work outside the scope of CESMM3 which has to be covered shall be

dealt with in the way which the compiler of the bill chooses, governed

‘only by the nced to give the itemization and identification of work in

item descriptions in sufficient detail to enable it to be priced

adequately.

Paragraph 2.2 does not imply a standard method of measurement

because for this type of work there is no necessity for there to be a

standard method. Thus, an entry in the Preamble to the bill which

complies with this paragraph might refer to another standard method

of measurement, such as the standard method of measurement for

building, or it might state a measurement convention adopted for a

particular work component. An example of this would be the

measurement of large oil tanks associated with oil refinery

installations. These are not mentioned in CESMM3 but they might

have to be measured within a civil engineering contract. In such a case

the compiler of the bill would probably decide to measure the tanks by

their mass of steel and might need to state related measurement

conventions in the Preamble to the bill. These conventions might

include the rules by which the mass of steel in the oil tank was to be

calculated for payment.

There is no need for non-standard measurement rules to be

complicated or indeed to be given atall in many cases. The function of

s bill item is identify work and to enable a price to beset against it

If, for example, an item description read: “The thing described in

Specification clause 252 and shown in detail D of drawing 137/65" and

were given as a sum to be priced by the Contractor it would be a

satisfactory item from all points of view. It would not require any

‘measurement conventions, No method of measurement is required

for any self-contained component of the work which does not have a

particular quantity as a useful parameter of its cost. It might be a

plague on the wall by an entrance, or a complicated piece of

manufactured equipment peculiar to the use to be made of the finished

project. Only if it is something which may be changed and the

financial control of which would benefit from remeasurement of a

cost-related quantity is it necessary to give a quantity for it in the Bll

“Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors and Building Employers’ Confeder:

Standard method of measurement of building works, 6th edn. Royal Institution of

Chartered Surveyors and National Federation of Building Trades Employers,

London, 1988,

—_—_——————$—$—$<$KFKFK<$<$_

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Usually these items are something like others which are covered by

CESMM3 and related measurement rules can be used

It is good practice to keep away from non-standard measurement

conventions for unusual work as much as possible because they can

become contentious in preparing final accounts, Ie is better to make

sure that the work required to provide the unusual thing is clearly

defined in the Contract and for it to be priced as a sum. If there are

several items they can be counted and measured by number,

Paragraph 5.18 of CESMM3 provides a general convention of

measurement, namely that quantities are measured net using

dimensions from the Drawings. Special conventions are needed for

non-standard work only when this general convention is

inappropriate.

Simple building works incidental to civil engineering works are dealt

with in CESMM3 through the introduction of class Z. This is because

compilers of bills were often reluctant to use the building standard

method of measurement for a simple incidental building such as a

gatehouse, valve house, or a simple superstructure in a water or

sewerage treatment works. Although use of another standard leads to

inconsistency between parts ofa bill and some problems of mismatch

with the Conditions of Contract, it should be considered when the

building work is substantial or complex. When the building work is 7

self-contained and uncomplicated it may be controlled most

effectively by being treated as specialist work. A provisional sum in

the main bill can then be used in a manner appropriate to the

circumstances. There should be few problems if it can be priced on a

complete and well thought out design which does not have to be

changed. Effort is better applied to achieving stable design than to

setting up contractual arrangements and drawing up a detailed bill of

quantities for something ill-defined which may not be what is

eventually wanted.

The scope of CESMM3 is referred to in general terms in paragraph

2.2. In detail it can be judged by examination of the various classes of

work and the lists of classified components of work which each class

includes. It should be noted that CESMM3 only provides procedures

for measurement of work which is normal new construction.

Maintenance and alterations to existing work are mentioned only in

relation to sewer and water main renovation. Extraction of piles is not

mentioned, nor is any other work which involves removal of previous

work unless that work is classed as demolition. Any such activity

which is to be included in a Contract must be included in the Bill of

Quantities. Itis suggested that the itemization and description of such

work should follow the principles of the appropriate class of

CESMM3 for new work, with the fact that the items are for extraction

or removal stated in descriptions or applicable headings. Class ¥

dealing with sewer and water main renovation is an exception to the

general principle that CESMM3 only provides for new construction,

Ie does not indicate that the general principle has been abandoned,

When the compiler of a bill is faced with a drawing which shows a

¢omponent of work not mentioned in CESMM3, he will occasionally

be in doubt as to whether it is outside the scope of CESMM3 or

whether itis within its scope but not mentioned because a separate bill

item for itis not required. No standard method of measurement could

avoid this dilemma entirely as there will always be some items of work

13

‘CESMM3 HANDBOOK

14

whose nature is just outside the normal understanding of the terms

used to name work items in the method. CESMM3 should yield few

instances of this dilemma, ‘but where it does arise, the treatment

should always be to insert non-standard items which describe the

work clearly and preferably also to state the location of the work. The

resulting bill cannot be held to be in error as this treatment is preciscly

that intended by paragraphs 2.2 and 5.15.

The objects of the Bill of Quantities are set down in paragraphs

2.4-2.7. Paragraph 2,5 encapsulates the theme of this book. It is

important to the financial control of civil engineering contracts that

the people who influence it should concern themselves with the

practical realities of the costs to contractors of constructing civil

‘engineering Works. Paragraph 2.5 establishes an overriding principle

that Bill of Quantities Should encoarage expostite of cost differentials

arising from special circumstances. It is the application of this

principle which puts flesh on the standardized skeleton of a bill of

‘quantities and makes the descriptions and prices particular to the job in

hand. Its importance is hard to over-emphasize. Differences in

construction costs due to the influence of location and other factors on

methods of construction are often much greater than the whole cost of

the smaller items of permanent work which are itemized separately in

abill.

‘The items dealing with pipe laying and drain laying provide an

example of this. Many bills used to include a schedule of trench depths

for drain laying so that an appropriate slightly different rate could be

paid for excavating and backfilling trenches whose depths were

slightly different, perhaps 100 mm shallower, than that originally

billed. In practice the cost of the work is so dependent on whether or

not the trench can be battered, whether or not it is through boulders,

whether or not there is room to side pile the spoil, whether or not

adjacent buildings prevent a backacter swinging round and so on that

differences in depth make lle impact on the diflerence between the

actual cost and the bill rate,

That cost significance is the allsimportant factor in dividing the work

into separate bill items is demonstrated by how CESMM3 deals with

this matter, Lengths of pipe laying are given in separate items to

indicate different locations by reference to the Drawings (rule A1 of

class 1). Items are subdivided according to trench depth only within

depth ranges.

In applying these detailed rules and the general principle in paragraph

2.5 the bill compiler is required to think about construction costs and

to divide up the work so that the likely influence of location on cost is

exposed in the bill, He will not be able to read the minds of the

contractors who will price his bill, who will not in any case be of one

mind as to what is or is not cost significant. Paragraph 2.5 confers on

the compiler the obligation to use his best judgement of cost

significance while protecting him from any Consequence of his

judgement being less than perfect. It achieves this by saying that he

‘should’ itemize the bill in a way which distinguishes work which

‘may ’ have different cost considerations. If he does not foresee cost

differentials perfectly, as he cannot, a contractor cannot claim that the

bill is in error and ask for an adjustment to payment. Paragraph 2.5

ends with an exhortation to strive for brevity and simplicity in bills.

Bills of Quantities are not works of literature: they are vehicles of

ee

i GENERAL PRINCIPLES

technical communication. They should convey information clearly

and, in the interests of economy, briefly. An engineer writing a bill of

quantities should aim to carry the load of communication safely but

with minimum use of resources, in the same way as in his design he

aims to carry physical load safely with minimum use of resources.

A general principle not stated in CESMM3 is the principle that its use

is not mandatory. Whether or not a standard method of measurement

a mandatory document used to be a favourite discussion topic, and

each view had strong adherents. When using the ICE Conditions of

Contract the method of measurement applicable to each contracts the

one the title of which is inserted in the Appendix to the Form of

Tender: now normally the Civil Engineering Standard Method of

Measurement, Such an insertion brings clause 57 of the Conditions of

Contract into play, giving a warranty (subject to the condition given

in the opening words of the clause) that the Bill of Quantities shall be

‘deemed to have been prepared and measurements shall be made

according to the procedure set forth’ in the Civil Engineering

Standard Method of Measurement. In order to relate properly to this

clause the rules of CESMMG are expressed in authoritative terms; they

say, for example, that ‘separate items should be given’ and

“descriptions shall include’.

The Employer or Engineer is free to decide not to use CESMM3, but

if he decides that he will use it, he must do what it says that he'shall

unless he expressly shows in the Bill of Quantities that he has done

otherwise.

There are a few instances where CESMM3 says that details of the

procedure ‘should’ or ‘may’ be followed. In these instances there is no

infringement of CESMM if the procedure is not followed. These less

imperative details of procedure are of two types. One type concerns

the procedure for bill layout and arrangement, which has no

contractual significance whether followed or not; paragraphs 4.3 and

5.22 are examples. The other type is where the bill compiler is

encouraged to use his judgement of likely cost-significant factors to

decide on such matters as the subdivision of the bill into parts

{paragraph 5.8) or the provision of additional item description

(paragraph 5.10). Since the compiler cannot accurately make such

Judgements without an unattainable foreknowledge of the factors

which would actually influence the Contractor's costs, he can only be ‘Schedule of changes in CESMM2

encouraged to do his best, secure in the knowledge that hismothaving 1, Newly stated princste at peragraph

Bot i quite right will not entitle the Contractor to have the bill "28

corrected later by an application of clause 55(2). This clause is in the 2 Former paragraph 2.6 is

background of all the uses of the words ‘may’ and ‘should’ in renumbered 2.7.

CESMM3. If, for example, paragraph 5.22 had said ‘the work items

shall beset out in column tuled as follows --'a Contactor could SehadUe of chergosin CESS

have asked for a bill to be corrected if the rate column ona particular 1. Paragraphs 2.1 and 2.2 make

age were only 19 mm wide, Whether ornot the Engineer would then reference to class 2 for the

decide that this affected ‘the value of the work actually carried out’ is ‘easurernent of simple ‘buidrg

another matter. It would obviously have been pedantic to have made engineering works,

this a rule instead ofa suggestion aimed at helpful standardization.

18

, APPLICATION OF THE WORK CLASSIFICATION

SECTION 3. APPLICATION OF THE WORK CLASSIFICATION

‘The Work Classification is the framework and structure of CESMM3.

It is the main instrument of CESMM3 by which co-ordination of

various financial control functions is fostered. It is a basic classification

of the work included in civil engineering contracts which can be used

for all purposes where it is helpful

Examples of use of the Work Classification outside CESMM3 itself

are: as the basis of contractors’ allocations in cost control, as an index

for records of prices to help with pre-contract estimating and as an

index to Specification clauses. The classification is a list of all the

commonly occurring components of civil engineering work. It starts

with the contractual requirement to provide a performance bond and

ends with renovation of sewer manholes.

The Work Classification is not a continuous list. It is divided into

' blocks of entries which have generic names. First the whole list is

divided into 26 classes from ‘Class A: General items’ to ‘Class 2:

Simple building works incidental to civil engineering works’. In

between are classes for main operations, like class E for earthworks

and class P for piling. Each class is divided into three divisions. The

first division is divided into up to cight of the main types of work in

the class, the second divides each of these up to cight times, and the 8.3. Ciassifcation table for pipasin

process is repeated into the third division. Class I for pipes is illustrated Ceo Gecctoa toni

Bi tig, 3. The frst division classifies pipes by the material of which hrecensaonsoreesatetoon cars

they are made, the second by thenominal bore ofthe pipeand the third "bina to produce biet descrptions

by the depth below the Commencing Surface at which they are laid. and code numbers for groups of com

ponents of chil engineering works. In

this case the brief descriptions are

‘The entries in the divisions are called ‘descriptive features’ because, cetnedir bile otautetos by

when three are linked together — one drawn from each division more specific information given in

between the same pair of horizontal lines — they comprise the ‘accordance with the additional

description of a component of work in the full list of work in description rules in class

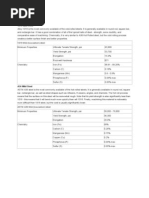

CLASS |: PIPEWORK — PIPES

Includes: Provision, laying and jointing of pipes

Excavating and backfiling pipe trenches

Exeludes: Work included in classes J, K, Land Y

Piped building services (ineludedinciass Z)

RST DIISION SECOND DIVISION THiRo oNsiON

1 Clayoipes ar [a Nominal bore: notesceesing 00mm | 1 Notinrenches

2 Concrtepipes m2 300"360 mm 2 Intvenenes, Soph: not excoading 15m

3 Wronpipee nis 300-800.mm 3 {Sam

4 Stotpipes mys 00-800 mm 4 23m

5 Folnylchloae pins ms So. asa mm : Ban

Glessrenforcedpleste pipes mis "300-1s00mm m

z ra mi? 1500-1800 mm 7 354m

8 mie exceeding 100mm |B excoeding Am

v7

CESMM3 HANDBOOK

18

the whole classification. Thus class I can generate 512 components in

the list, from ‘Clay pipes nominal bore not exceeding 200 mm not in

trenches’ to ‘Medium density polyethylene pipes nominal bore

exceeding 1800 mm in trenches depth exceeding 4m’.

‘All components can be identified by their position in the classification

list if the numbers of the descriptive features are also linked together.

Thus the components mentioned in the previous paragraph are

numbers 111 and 888 respectively of class I. When a class letter is put

in front ofa number, a code number which identifies the component is

produced. Thus 123 4 is a unique reference number for iron pipes of

nominal bore 300-600 mm laid in trenches of depth 2-2.5 m.

‘The Work Classification does not subdivide to the finest level of detail

at which distinctions might be needed. It does not, for example,

subdivide pipes according to the different types of joints which can be

used or different specifications of pipe quality. Also the method of

trenching is not classified; neither is the type of terrain being crossed.

The reason for this is that the Work Classification and the code

numbers which go with it are intended to be adopted as the core of

wider ranging classification systems used for other purposes and not

necessarily standard among different users. This is the main

importance of the Work Classification. Linked as it is to the items in

the Bill of Quantities, it makes the use of logical data handling muct

more worthwhile than hitherto on both sides of the contract. Wher

bill items arising from any Employer or Engineer fit into the same

classification, the use of an expansion of that classification by the

Contractor as a framework for systematic estimating, cost recording

output recording and valuation becomes possible and justifiable. Alsc

bill preparation, with the aid of computers, estimating for the

Employer linked to prices and escalation factors stored within the

‘Work Classification are made simpler.

Coded classification of items in the Bill of Quantities is the key to the

development of modem data handling arrangements used in civi

engineering contracts, Tt makes possible computer assistance acros

the whole spectrum of financial control. The person taking of

quantities from a drawing could begin a process which was wholl

computer aided up to the point where a draft-analysed estimate fo

consideration by a tenderer’s estimator was produced, Itis not fancifu

to foresee that, if a disc of the Bill of Quantities were to be sent ov

with the invitation to tender, this could be used by the recipien

contractors to produce immediately an analysis of the job wit

tentative prices calculated from output figures and current unit cost

drawn from files held on their own computers. The estimator's jo

would then be to convert these average prices into prices appropriat

to the specific job for which the tender was required.

Clearly, sophistication of that order is not necessary, desirable

practicable in all cases and the usefulness of the Work Classificatio

does not depend on such refinement being attained. The discipline ¢

compiling CESMM3 for possible usc in that way meant that a

procedures related to it could be made simple and logical. This h:

more immediate benefits to organizations that do not aim to be in tk

forefront of systems development. For example, the fact thar bil

compiled using CESMM3 list items within the classes of CESMM

means that contractors are able to set up simple arrangements f¢

allocating costs to classes and to find that these match self-containe

[APPLICATION OF THE WORK CLASSIFICATION

site activities. The simplest possible form of cost monitoring and

comparison with valuations is thereby made utterly straightforward,

and can be achieved without requiring a small company to use or

obtain the help of specialists to set up a new procedure. The

classification provides for contractors’ indirect and overhead costs to

be allocated to class A. Also two of its eight first division features are

left unused to provide room for any such costs which do not appear as

prices in the Bill of Quantities and which would not become the

subject of Method-Related Charges.

The application of the Work Classification to the preparation of Bills

of Quantities is explained in section 3 of CESMM3. Paragraph 3.1

requires that each item description should identify the component of

work covered with respect to one feature from each division of the

relevant class. The following example is given

‘Class H_ (precast concrete) contains three divisions of classi-

fication, The first classifies different types of precast concrete units,

the second classifies different units by their dimensions, and the

third classifies them by their mass. Each item description for precast

concrete units shall therefore identify the component of work in

terms of the type of unit, its dimensions and mass."

Paragraph 3.1 docs not say that the item descriptions shall use

precisely the words which are stated in the Work Classification. Bill

compilers are therefore not bound to use the words given in the Work

Classification; they should use judgement to produce descriptions

which comply with paragraph 3.1 without duplicating information.

‘This is particularly noteworthy where more detail of description is

required by a rule in the Work Classification than is given in the

tabulated and classified lists themselves. For example, a joint in

concrete may be measured which comprises a ‘plastics waterstop

average width 210 mm’. That is an adequate description which docs

not have to be preceded by a statement that the waterstop is made of

‘plastics or rubber’ or that it is in the size range 200-300 mm’

Compilers of bills of quantities will need to exercise this type of

judgement in many instances, most commonly when a rule requires a

particular definition to be given in addition to the general definition

provided by the Work Classification table. The rule then overrides the

tabulated classification so that the latter merely indicates the

appropriate code number for the items concerned. Rule 3.10 confirms

this arrangement

Another example will serve to emphasize this important point. It

shows that the wording of the Work Classification can be simplified in

item descriptions without losing meaning and without infringing the

rule in paragraph 3.1. The text ‘Unlined V section ditch

cross-sectional area 1-1.5 m?" would identify an item clearly as

derived from the descriptive features for item K 4 6 5. It is not

necessary to add to the description the words from the first division of

the classification at K 4 * * : ‘French drains, rabble drains, ditches and

trenches’, This is because the word ‘ditch’ appears in the second

* division descriptive feature and itis irrelevant to point out in the item

description that the item is from a division which also includes French

and rubble drains.

The lists of different descriptive features given are compiled to show

the eight most common types of component in each part of the class.

They do not attempt to list all types of component in any class. The

18

CESMMS HANDBOOK

20

digit 9s to be used for any type of component which is not among th

eight listed

Paragraph 3.2 deals with the question of style in item descriptions. Ie

point is that the bill, where it is dealing with Permanent Works

should identify the physical measurable things and not attempr to lis

all the stages of activity which the Contractor will havc to go throug!

to produce them, There are good reasons for this apart from brevity

However careful the bill compiler might be in listing the necessar

tasks there will always be at least one more he could have added. Th

risk of listing tasks inconsistently from one item to another i

considerable, and if it occurs the Contractor may subsequently alleg

that he had not allowed for the thing in the item that was incomplete

It is better and contractually proper to rely on the wording of th

Specification, Drawings and Conditions of Contract to establish th

overriding assumption that the Contractor knew what he had to dot

achieve the defined result and either did or did not allow for it in hi

price, entirely at his own risk. For example, suppose a bill item wer

worded: ‘Supply, deliver, take into store, place in positior

temporarily support, thoroughly clean and cast onto in situ concret

mild steel channels as specified and in accordance with the Drawing

all to the satisfaction of the Engineer and clear away all rubbish o

completion rate to allow for all delays and any necessary cutting <

formwork and making good.’ This descripion is much ler

informative than ‘Mild steel channels in pumphouse roof beams :

detail E on drawing 137/66."

‘The latter description is much less dangerous to financial control if tt

work on behalf of the Employer than the first, not just becau:

something may have been left out of the first, but because the fir

invites comparison with other item descriptions. Ifit is not stated th

some other component is to be cleaned, the Contractor may conter

that he has not allowed for cleaning, despite the fact that it would t

unreasonable for him to expect not to have to.

Phrases like ‘properly cleaned’, ‘to a good finish’, and ‘well ramme

should be avoided like the plague. They are usually masks for slopy

specification. ‘To the satisfaction of the Engineer’ is a particular

abhorrent phrase to use ina bill of quantitics. The Contractor is und

a general obligation to ‘construct and complete the Works in stri

accordance with the Contract to the satisfaction of the Engine:

(clause 13(1)). Adding these phrases to a bill item description

misguided on ewo further counts. First the Specification, not the B

of Quantities, is the place to define workmanship requirement

Second if the Engineer knows what standard of work will bring hi

satisfaction he should describe it in the Specification; if he does n

know what standard he requires, the Contractor assuredly cann

know and cannot estimate the cost of reaching it.

Paragraph 3.2 refers to item descriptions for ‘Permanent Work

CESMMB also sets out rules for temporary works such as formwo

and temporary supports which should also be described in accordan

with paragraph 3.2.

In the context of paragraphs 3.2 and 3.3, it should be noted that t

general case, assumed unless otherwise stated, is that item descriptic

‘identify new work which is to be constructed by the Contractor usi

materials which he has obtained at his cost. Additional descriptior

APPLICATION OF THE WORK CLASSIFICATION

needed wherever this assumption is not intended. For example,

additional description is needed to identify items for extracting piles,

for underpinning and related work to existing structures, and for any

work which involves the use of existing materials, such as the

relocation of existing street furniture

The first example in paragraph 3.3 uses the expression ‘excluding

supply and delivery to the Site’ to illustrate an item description for

work which is specifically limited. Compilers of bills of quantities

should note that this expression is not defined in CESMM3 as its exact

scope may vary from one contract to another. For example, pipework

supplied by the Employer may be for collection by the Contractor

from a depot or may be delivered to the site for the Contractor.

Compilers of bills of quantities should therefore ensure that,

whenever the scope of an item is specifically limited in this way, the

precise limitation is stated and that, if an abbreviated expression such.

as ‘fix only’ is used, a definition of this term is given in the preambles

to bills or in a heading to the appropriate items.

A second example is included in paragraph 3.3. This is intended to

clarify how work divided between two bill items should be described.

This often occurs when additional description is necessary to make it

clear how the cost of supply and fix ate divided between two items.

The principle to be followed in bills prepared using CESMM3 is

simple. Unless otherwise stated, all items are assumed to include both

supply and fixing of the work they cover. Whenever this is not

intended, additional description must be given to identify whether the

item is intended to cover supply or to cover fixing.

Paragraphs 3.4 and 3.9 which deal with separate items, are important

as they directly govern against which different components of work

the tenderer will be able to insert different prices. There is no absolute

criterion of ‘full’ measurement no level of detailed subdivision of the

work into items which is complete or incomplete. A bill of quantities

for a motorway would earn the name if it contained one item

‘Amount

Number | Item description | Unit | Quantity | Rate

£ |p

1 Motorway m_| 23124

It would also earn thename ifit contained separate items for each piece

of reinforcing stccl of a different shape in each different bridge, for

each differently shaped formwork surface, for each detail of water

stops and drainage fitings, and generally for no two things of any

detectable dissimilarity. Such a bill would contain several thousand

items and would be as useless due to its over-complexity as the single

item bill would be due to its over-simplicity.

In practice effective financial control is served by using bills of

quantities which balance the opposing pressures for precision and

simplicity. Real cost differentials should be exposed by dividing work

into separate items which itis helpful to price differently. Trivial or

imagined cost differentials are ignored when their influence on the

amounts of money changing hands does not justify the cost of

cosseting the necessary items through the processes of estimating and

interim measurement into the final account.

2

CESMM3 HANDBOOK

2

The effect of paragraph 3.4 is that no two items from the Work

Classification list may be put into one item. Hence formwork may not

be included with concrete, lined and unlined ditches may not be

covered in the same item, and so on. Thus the Work Classification,

coupled with paragraph 3.4, has the effect which is achieved in other

methods of measurement by many different rules of the general form,

separate items shall be given for lined ditches’ or for any other

distinctive component of work.

Paragraphs 3.6-3. 11 are the rules which establish the function of all the

material which appears on the right-hand pages of the Work

Classification. The rules are categorized according to whether they

refer to measurement itself, definitions of terms used in the Work

Classification coverage to be assumed for particular items and

description to be given in addition to that which is derived from the

main classification tables in accordance with paragraph 3,1. These

four types of rules are set out in columns. Generally, each rule is

printed alongside the section of the classification tables on the

left-hand page to which it refers. Fig. 4 is a reproduction of the first

group of right-hand page rules from class C of CESMM3.

Paragraph 3.6 is the definition of the first type of rule, the

measurement rule, Measurement rules either say something which

affects how a quantity against a particular item or group of items will

be calculated or say something about the circumstances in which

particular work will or will not be measured. The measurement rules

exemplified in Fig, 4 show these different functions. Rules M1 and M2

are rules affecting the quantity calculated for such items as the depths

of holes in carrying out geotechnical processes. Rule M3 is a

‘measurement rule stating the circumstances in which work associated

with drilling grout holes shall be measured. M¢ is an example of a

measurement rule using the expression ‘expressly required’. All uses

of this expression in the Work Classification are contained in the

‘measurement rules.

Paragraph 3.6 refers to paragraph 5.18. The logical connection

between the two demonstrates that the measurement rules are quite

clearly and consistently the exceptions to the general rule of

calculation of quantities set out in paragraph 5.18, Put another way,

this means that if there is no measurement rule alongside a particular

group of items in the Work Classification the general rule of

measurement in paragraph 5,18 applies. This is the principle, but it

does not apply entirely. It has to be qualified because there may be

measurement tules that are applicable to the whole of one class which

appear at the head of the class as illustrated by Fig. 4.

Paragraph 3.7 establishes the function of definition rules. The phrases

or words for which definitions are given in the definition rules are

assumed to have the same meanings when they are used in bills of

quantities. Most of the definition rules cover matters which it is

helpful to define in order to avoid ambiguity in bills of quantities. For

example, definition rule D8 in class F says thata wall less than 1 mlong

isto be called a column, Itis followed by definition rule D9 which says

what is meant by a ‘special beam section’. A particular function of

some definition rules is to enable bill item descriptions to be

abbreviated. The example which appears in Fig. 4 is of this type. It

says that drilling and excavation for geotechnical processes shall be

deemed to be in material other than rock or artificial hard material

‘APPLICATION OF THE WORK CLASSIFICATION

(MEASUREMENT RULES DEFINITION RULES COVERAGE RULES

CLASS C

ADDITIONAL

DESCRIPTION RULES.

{obs m moter other ten sector

irsfotherdmatonalunces

Stroreiso satan tem

Seseions

DI Driling andexcavatonior | C1 Wamatormorkinthiaclass

orkinisclassshell be deomes | shalibe deemed telnctda

IM3_ Orting trough previously i}

routed holes inte course oF

Stage growing shal not be

aeured. Where oles are

‘cpessiy aquired tobe

‘extended the numberct bales

{hall be meesared onc ding

through previously proved hoes

‘halloe mecsureaa ding

tivough oct or rit hae

IMa_ the numberof stages

‘measured shal athe tal

umber of grouting stages

Bepresry requires

'At_ The darters ofholes sal

ba stated item descitions ler

Erling ae eng fo grout hoes

unless otherwise stated in item descriptions. The effect of this rule is

nothing more than to permit the words ‘material other than rock or

artificial hard material’ to be omitted from bill item descriptions. This

mechanism is used in a number of places in CESMM3 to allow the

words which would establish the general case to be omitted from bill

item descriptions leaving only special cases to be explicitly mentioned,

Paragraph 3.8 is an important rule in CESMM3 which establishes the

fanction of coverage rules, Work inchided by virtue of a coverage rule

does not need to be itemized separately in the Bill of Quantities. For

example, coverage rule C1 in class R of CESMMG states that items in

the class which involve in situ concrete shall be deemed to include

formwork.

Paragraph 3.8 includes a very important provision to the effect that

coverage rules do not state all the work covered by the item

concerned. This means, taking the same example again, that items in

bills of quantities for concrete carriageway slabs do cover, and the

rates entered against such items in a Bill of Quantities arc decmd to

include, formwork. Paragraph 3.8 is worded carefully so that the

existence of this coverage rule cannot lead to an argument that any

work other than formwork is not included in the item because itis not

mentioned in the rule. It follows that coverage rules only draw

attention to particular elements of cost within a bill item which are

certainly deemed to be covered. They leave the majority of the

clements of cost to be inferred from the description used in the Bill of

Quantities which identifies the work shown on the Drawings and

described in the Specification. The coverage rule does not, of course,

override drawings and specifications in the sensc that if, for example,

no formwork is required for a particular carriageway slab the rate

against a bill item for it would not include formwork. Coverage rules

do not normally mention work which is also mentioned in additional

description rules. Occasionally this repetition is made in order to add

emphasis

Fig. 4. The layout of the classified

rulas in CESMM3: note the different

style of each of the four types of rule,

‘the horizontal alignment and the use

of the double horzontal ine to

separate rules of general application

to the class,

(CESMM3 HANDBOOK

2

‘The last sentence of paragraph 3.8 points out that the Contractor may

have allowed for the work referred to in a coverage rule in :

Method-Related Charge. This is quite permissible and indeed is to bx

encouraged where the cost of the work referred to in the coverage ru

is either independent of the quantity required or related to time.

Paragraph 3.9 in CESMMS establishes the function of the additiona

description rules in the Work Classification. The importance of th

additional description rules should be emphasized. Paragraph 3.9 i

very explicit. In simple terms, it should be understood that th

classification tables on the left-hand page in CESMM3 only generat

the basic subdivision of civil engineering work into items and the basi

descriptions which will be used. Further description and furthe

subdivision into items is very often required as a result of applying th

additional description rules. The main classification tables are divide.

into three divisions. [It may be helpful to think of the additions

description rules as providing a fourth uncoded division.

Paragraph 3.10 makes it explicit that additional description rules cat

override the main classification table. It refers in particular t

dimensions mentioned in item descriptions. There are a number 0

instances in CESMM3 where an additional description rule requires

particular dimension to be stated in an item description although th

related part of the Work Classification table only requires a range 0

dimensions to be stated. The most well known example of this is th

cone which is used as an example in CESMM3.

Additional description rule A2 of class I requires that the nominz

bores of the pipes shall be stated in item descriptions. The range ¢

nominal bore taken from the second division of the classification

class I shall not also be stated.

The rule in paragraph 3. 11 is illustrated in Fig. 4. To reduce repetitio.

of the rules in CESMMG3, any rales which apply to the whole of a clas,

ate printed at the head of the first right-hand page above a doubl

horizontal line. Ifthe class runs over onto a second page, a reminde

that there are rules of general application is printed at the head of th

following right-hand page. In some classes, rules are repeated once 0

twice within the class because they apply to more than one section ¢

the table. In such cases the rule is printed more than once but th

number is kept the same.

“The phrases printed in italics in the rules on the right-hand pages of th

Work Classification are those which are taken directly from th

classification table on the left-hand page. This has no contract:

significance: its adopted merely as a convenience to enable users ¢

CESMMS to recognize very quickly the type of work to which th

tule refers.