Decision Making Skills of High Performance Youth Soccer Players

Decision Making Skills of High Performance Youth Soccer Players

Uploaded by

Esteban LopezCopyright:

Available Formats

Decision Making Skills of High Performance Youth Soccer Players

Decision Making Skills of High Performance Youth Soccer Players

Uploaded by

Esteban LopezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Decision Making Skills of High Performance Youth Soccer Players

Decision Making Skills of High Performance Youth Soccer Players

Uploaded by

Esteban LopezCopyright:

Available Formats

Main Article

Ger J Exerc Sport Res 2021 · 51:102–111 Dennis Murr1 · Paul Larkin2 · Oliver Höner1

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-020-00687-2 1

Institute of Sports Science, Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany

Received: 14 August 2019 2

Institute for Health and Sport, Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia

Accepted: 15 October 2020

Published online: 26 November 2020

© The Author(s) 2020

Decision-making skills of high-

performance youth soccer

players

Validating a video-based diagnostic

instrument with a soccer-specific motor

response

Introduction knowledge about a (current) situation players (e.g., Ruiz Pérez et al., 2014) re-

to select an appropriate decision, based search is scarce within talent promotion

In team sports like soccer, a multidimen- on one’s perceived ability to execute programs (e.g., regional association or

sional spectrum of performance factors is a context-specific motor skill. From youth national teams; youth academies)

required to perform at the elite level. This a sporting perspective, the ability to with high-performance level (e.g., elite)

has been acknowledged by Williams and make the correct decision during com- players. This statement is emphasized in

Reilly (2000) who developed a heuristic plex game situations, under high game a recent meta-analysis which explored

model for the categorization of soccer pressure and time constraints is a key cognitive functions measurements with

talent predictors. The model identifies component of in-game performance performance level as the moderator vari-

potential talent predictors across four (Höner, Larkin, Leber, & Feichtinger, able (Scharfen & Memmert, 2019). The

core areas of sport science, including 2020). Thus, decision-making has been results indicated, high-performance level

physical, physiological, psychological shown to be an important skill, with athletes had superior performance, with

and sociological characteristics. While several cross-sectional studies assess- a small to medium effect size, compared

there seems to be an emphasis on phys- ing decision-making performance and to low-performance level athletes. While

iological and physical characteristics in demonstrating that decision-making there is a plethora of studies examining

research and practice (Johnston, Wattie, skills discriminate between skilled and known group differences, a potential

Schorer, & Baker, 2018; Wilson et al., less-skilled players in team sports (e.g., reason for the lack of research examin-

2016), recently, there has been increased Diaz, Gonzalez, Garcia, & Mitchell, ing homogenous samples could lie in the

interest in the psychological attributes, 2011; Lorains, Ball, & MacMahon, 2013; fact that it is more difficult to find large

such as perceptual-cognitive factors Woods, Raynor, Bruce, & McDonald, effect sizes for discriminating athletes

(Mann, Dehghansai, & Baker, 2017). 2016). With respect to soccer, Ruiz of a similar ability (Bergkamp, Niessen,

Researchers have highlighted the im- Pérez et al. (2014) found Spanish club den Hartigh, Frencken, & Meijer, 2019).

portance of perceptual-cognitive factors players with international experience Despite the fact researchers have used

for skilled performance, with findings demonstrated better decision-making cross-sectional approaches to discrimi-

showing highly skilled players possess performance in comparison to local nate between high- and low-performance

superior decision-making, anticipation level players. Further, Höner (2005) decision-makers, Murr, Feichtinger,

and situational probability proficiency found youth national players had su- Larkin, O’Connor, and Höner (2018)

compared to their less-skilled coun- perior decision-making skills compared highlighted in their systematic review

terparts (e.g., Lex, Essig, Knoblauch, to local youth players, and additionally that there is a significant gap in the

& Schack, 2015; Ward, Ericsson, & older players (i.e., U17 age group) had literature concerning empirical evidence

Williams, 2013). a significant decision-making perfor- related to the predictive value of decision-

The focus of the current study is mance advantage over younger players making assessments. According to this

decision-making as the cognitive perfor- (i.e., U15 age group). While researchers review, only one investigation has used

mance factor. Causer and Ford (2014) have used an expertise approach to a video-based assessment to examine

define decision-making in sports as highlight superior performance of ex- the predictive ability of decision-making

a cognitive process in which one uses pert/elite players over novice/nonelite skills in soccer. O’Connor, Larkin, and

102 German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 1 · 2021

Williams (2016) demonstrated a large Traditional diagnostic instruments with the ball while watching the video

significant effect in discriminating be- used to examine decision-making, such stimuli and then execute their decision

tween selected and nonselected players as video-based tests, provide advantages by passing to a player in the video).

within an Australian talent development in test execution or methodological con- Travassos et al. (2013) reaffirmed this

program. However, it should be noted trol and have demonstrated the ability issue and emphasized that an expertise

the prognostic period for this study to discriminate skilled and less-skilled effect is more consistent if participants

was very short (i.e., the selection at the players (e.g., Roca, Williams, & Ford, have to execute sport-specific actions in

conclusion of the data collection), with 2012). However, a limitation of previous experimental studies. Hadlow, Panchuk,

further research required to investigate investigations is the video presenta- Mann, Portus, and Abernethy (2018)

longer prognostic periods. Despite this tion stimuli which is often presented address these topics in a new classifi-

positive result, more research is needed to from a third-person perspective (i.e., cation framework to modify perceptual

develop valid and reliable measures that television broadcast perspective; e.g., training in sport and emphasize the im-

have a strong predictive value to assist O’Connor et al., 2016). It has been sug- portance of high sport-specific stimulus

the identification of high-performance gested however, when developing sport- and response correspondence.

level talent. specific assessments, that researchers

In addition to the lack of assessment consider increasing the representative- Present study

within high-performance level groups, ness of a task (Bonney, Berry, Ball, &

a further restriction of the current de- Larkin, 2019). Therefore, there could be With respect to their meta-analysis,

cision-making literature is the limited a benefit of presenting the video stimulus Travassos et al. (2013) suggested fur-

understanding of the potential per- from a first-person perspective which ther research is required to develop and

formance differences between playing represents a more realistic perceptual examine the impact of decision-mak-

positions. From a physical perspective, environment compared to broadcast ing instruments which integrate sport-

researchers have found physiological footage. specific perceptual (e.g., first-person

and anthropometric differences across A further limitation of the current perspective) task constraints and sport-

playing positions. For example, Rago, diagnostic instruments is the method of specific (e.g., passing or shooting) skill

Pizzuto, and Raiola (2017) revealed mid- responding to the video presentation, executions. Therefore, this study aims to

fielders and defenders completed more with participants providing a verbal, develop and evaluate a valid first-person

high-intensity running than forwards, written or button response (e.g., Larkin, perspective video-based diagnostic in-

and Boone, Vaeyens, Steyaert, Vanden O’Connor, & Williams, 2016; Ward strument which incorporates a soccer-

Bossche, and Bourgois (2012) found cen- & Williams, 2003). Currently, it re- specific motor response to the decision

tral defenders are taller and heavier than mains unclear if these nonsport-specific process and, thus, to provide a more

midfielders and wing defenders. There- responses correspond to real game situa- representative task.

fore, it is possible that due to specific tions and performance (van Maarseveen, To address this aim, three objectives

game-related roles of players in different Oudejans, Mann, & Savelsbergh, 2016). were pursued: In order to ensure a scien-

positions (e.g., make goals, organize Overall, the extant research lacks studies tific sound assessment, the reliability of

the build-up), in addition to physical examining decision-making competence the diagnostic instrument was evaluated

capabilities, playing position may also on video-based measures which incor- (Objective I). The focus of this study

influence decision-making ability (De- porate a sport-specific motor response. was on the criterion-related validity of

prez et al., 2015; Pocock, Dicks, Thelwell, To address this limitation, Hagemann, the diagnostic instrument (Objective II).

Chapman, & Barker, 2019). An initial Lotz, and Cañal-Bruland (2008) utilized Here, both diagnostic and prognostic

investigation by Höner (2005) attempted a video-based decision-making train- validation methods were used to ex-

to address this issue and demonstrated ing tool with a soccer-specific motor amine positive relationships between

that midfielders make better decisions response. Using a similar visual-mo- the diagnostics’ results and appropriate

compared to defenders and forwards. tor response (i.e., players had to pass performance factors (i.e., age groups

However, the results could be attributed the ball against different targets in the in middle to late adolescence, playing

to the situations used in the video scenes video), Frýbort, Kokštejn, Musálek, and time in official matches of the current

which presented more offensive deci- Süss (2016) investigated the influence of season, future draft in youth national

sions specific to midfield performance. varying exercise intensity on decision- team) resulting in three hypotheses:

Therefore, research is needed to address making time and accuracy. Although

this limitation by attempting to measure these investigations provide the foun- Diagnostic validity:

decision-making performance in dif- dation for incorporating soccer-specific

ferent game contexts, such as build-up responses within laboratory-based de- H1 Decision-making skills improve

(i.e., wing and central defense situations) cision-making training, to date no di- across adolescent age groups (i.e., U16;

and offensive (i.e., midfield and forward agnostic instruments assess decision- U17; U19) Specifically:

situations) game-based decisions. making skills using a more represen-

tative task (e.g., participants dribble

German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 1 · 2021 103

Abstract

4 H1a: U17 soccer players demonstrate Ger J Exerc Sport Res 2021 · 51:102–111 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-020-00687-2

better decision-making skills than © The Author(s) 2020

U16 players

4 H1b: U19 soccer players demonstrate D. Murr · P. Larkin · O. Höner

better decision-making skills than Decision-making skills of high-performance youth soccer players.

U16 players Validating a video-based diagnostic instrument with a soccer-

4 H1c: U19 soccer players demonstrate specific motor response

better decision-making skills than

U17 players Abstract

Objectives. This study aimed to develop players (U17 > U16 in SCbu: Φ = 0.24 and SCoff:

a valid video-based diagnostic instrument Φ = 0.39, p < 0.01; U19 > U16 in SCbu: Φ = 0.41

H2 Players who played more minutes that assesses decision-making with a sport- and SCoff: Φ = 0.46, p < 0.01); however, there

in official matches of the current sea- specific motor response. was no difference between U17 and U19

son demonstrate better decision-making Methods. A total of 86 German youth aca- players. Furthermore, the predictive value of

skills than players with less minutes. demy players (16.7 ± 0.9 years) viewed game the test indicates that future youth national

situations projected on a large video screen team players make better decisions with

and were required to make a decision by respect to the build-up category (SCbu:

Prognostic validity: dribbling and passing to one of three targets Φ = 0.20; p < 0.05), whereas playing position

(representing different decision options). did not significantly influence decision-

H3 Future youth national team play- The test included 48 clips separated into making competence.

ers demonstrate better decision-making two categories: build-up (bu) and offensive Conclusion. Results indicate the video-based

decisions (off). Criterion-related validity was decision-making diagnostic instrument can

skills than nonselected players.

tested based on age (i.e., U16, U17, and discriminate decision-making competence

Finally, in an explorative analysis it U19), playing status (i.e., minutes played in within a high-performance youth group.

was examined whether decision-making official matches of the current season) and The outcomes associated with national

performance is influenced by playing po- in a prospective approach relating to future youth team participation demonstrate the

sition (Objective III). youth national team status (i.e., selected or predictive value of the diagnostic instrument.

nonselected). Finally, it was investigated This study provides initial evidence to suggest

whether decision-making competence was a new video-based diagnostic instrument

Methods influenced by playing position (i.e., defenders with a soccer-specific motor response can be

vs. midfielders vs. forwards). used within a talent identification process to

Sample and design Results. Instrumental reliability demonstrated assist with assessment of decision-making

satisfactory values for SCbu (r = 0.72), and performance.

The study sample consisted of 86 youth lower for SCoff (r = 0.56). Results showed

the diagnostic instrument is suitable for Keywords

academy players, born between 1996 and discriminating between playing status (SCbu: Football · Talent identification · Adolescence ·

2001, from a professional German soc- Φ = 0.22, p < 0.01; SCoff: Φ = 0.14, p < 0.05) Perceptual cognitive factors · Athletic

cer club. The players competed in the and between younger (U16) and older performance

highest German youth league, and thus

belong to the top 1% of German players

for their age groups (i.e., U16, U17, and

U19). At the first measurement point the dent variable age group (H1) were ex- of all 86 players were captured. Play-

players were 15–19 years of age (median amined splitting the sample into three ers who participated at least in one Ger-

[Mage] = 16.7 years, standard deviation age categories (U16: N = 41, U17: N = 55 man youth national team training course

[SDage] = 0.96) and were tested over a 3- and U19: N = 44; H1a–H1c). A further in subsequent seasons (i.e., 2015/2016;

year period (i.e., near the end of seasons analysis of the criterion-related validity 2016/2017; 2017/2018) were identified as

2014/15 to 2016/17), resulting in three was conducted on the independent vari- selected (N = 16), with all other players

measurement points (T2015, T2016, and able playing status (H2) that was deter- identified as nonselected (N = 70). Fur-

T2017). Over the 3-year period, a total mined based on minutes played in of- thermore, with respect to the explorative

of 140 data points were collected. Due to ficial matches (i.e., U19/U17 German analysis (Objective III), players were sep-

the nature of professional youth academy Youth Bundesliga and U16 Oberliga). arated by playing positions as defined by

selection processes (i.e., some players are Median split procedure was utilized to their respective coaches (i.e., defenders

deselected, and new players are recruited separate players into two categories: first [DF, N = 55]; midfielders [MF, N = 61];

to the academy) which resulted in not ev- team regular (i.e., who play more minutes and forwards [FW, N = 24]).

ery player being tested at all three time than median; N = 70) and reserve play-

points (. Table 1). ers (i.e., who play less minutes than the Decision-making diagnostic

To examine the three hypothesizes, median; N = 68). Further, to examine the instrument

the study sample was separated into three predictive value of the decision-making Stimulus materials Decision-making

subsamples. To assess diagnostic crite- diagnostic instrument relative to future competence was assessed using a newly

rion-related validity (Objective II), po- youth national team status (H3), data of developed soccer-specific video-based

tential differences between the indepen- the respective first measurement point diagnostic instrument. To create the

104 German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 1 · 2021

Table 1 Datapointscollectedwithrespect two passing options and one option to Only one correct option was determined

to age group and measurement time point shoot at goal. Between each trial, a black by the expert panel for each scenario.

Age Measurement point Total screen remained for 6 s. Each clip com- Any trial where the participant missed

group T2015 T2016 T2017 menced with the first frame of the video a target or did not decide before the

U16 13 12 16 41 frozen for 1.5 s, to orientate the partici- scene ended was also coded as a zero.

U17 21 17 17 55 pants to the situation. Subsequently, participants’ decisions

from 48 testing video situations were

U19 15 14 15 44

Procedure Each participant individually used for calculating offensive (SCoff; i.e.,

Total 49 43 48 140

completed the test in the same indoor mean value of 24 corresponding scenes)

room at the youth academy over a 6- and build-up (SCbu; i.e., mean value of

diagnostic instrument, more than 300 week period at each measurement point 24 corresponding scenes) decision accu-

dynamic on-ball decision-making situ- (i.e., T2015; T2016; T2017). At the com- racy scores. Both scores (i.e., SCoff and

ations, recorded from the first-person mencement of each test, the participant SCbu) were converted to a percentage of

perspective of the ball carrier at different was provided with a standardized in- correct decisions. As the primary aim

positions on the pitch (i.e., forward, struction (e.g., “In each scene you start of the study was to determine decision-

midfield, wing defense, central defense; to dribble from one of five positions.”; making accuracy, we did not calculate or

. Fig. 1) were designed and filmed as “A short freeze frame at the start of each assess speed of decision-making within

part of a pilot study (Dieze, 2015). video will help you to orientate to the cur- the study.

The footage of each situation moved like rent game situation.”; “During the drib-

a player in possession of the ball and were bling your decision is based on passing Statistical analyses

reviewed by a panel of expert coaches the ball to one of three targets that rep-

(i.e., one UEFA pro-level, one UEFA A- resent the position of your teammate.”). Data were analyzed using SPSS ver-

level and two UEFA B-level). During the Prior to each testing block, three famil- sion 24. Diagnostics’ instrumental relia-

review process, a round table forum was iarization video scenes were presented bility (Objective I) was examined using

held, whereby the panel discussed the for participants to become accustomed a split-half procedure (odd-even-method

outcome of each clip (i.e., best correct to the procedures and the respective cat- corrected by Spearman–Brown formula;

decision), until 100% agreement was egory situation. Participants were then Lienert & Raatz, 2011) for players’ first

reached. Following this detailed evalua- able to ask any questions they had in assessment results.

tion by the expert panel, 30 video scenes relation to the video or response pro- An examination of distributional

were selected as the most realistic game cedures. Following the familiarization properties revealed the decision-making

situations and were thus used for the videos, the 12 testing videos were pre- accuracy scores SCoff and SCbu were not

study (24 testing scenes; 6 familiarization sented. For each trial, participants were normally distributed. A Mann–Whit-

scenes). positioned with the ball on a starting ney-U-test (as one-tailed hypothesis) was

To ensure a more comprehensive di- position which represented the location used to determine differences in SCoff

agnostic instrument, the 24 testing video on the pitch. As the video commenced and SCbu between age groups, playing

scenes were mirrored (i.e., the same scene the participants started to dribble with status and future youth national team

presented from the opposite direction), the ball while watching the evolving game status (Objective II, H1–H3). To ex-

creating a final diagnostic instrument of situation on the screen. Prior to overstep- plore mean differences between playing

48 game situations. Each situation was ping a limiting line orthe videoscene end- positions, nonparametric Kruskal–Wal-

then classified as either offensive deci- ing the participant provided a response lis tests were conducted with post hoc

sions (i.e., situations in forward and mid- by passing to one of three possible tar- pairwise comparisons (Objective III).

field positions where players create scor- gets (i.e., supporting teammates in the As the number of measurement points

ing opportunities) or decisions that occur video, . Fig. 2). For each trial, the first may influence decision-making scores

in the build-up of a game (i.e., situations author recorded the target (i.e., decision) and consequently the results in regards to

in defensive positions such as wing and the participants passed the ball to, while the diagnostics’ validity (due to memo-

central defense where players start offen- a research assistant placed a ball on the rable or habituation effects), a priori anal-

sive moves). For testing, the video scenes next starting position. ysis was conducted to determine whether

were projected on a 2.76 m wide × 1.50 m the number of measurement points cor-

high video screen and were presented Dependent measures The decision- related with the independent variables

in four video blocks of 12 videos (i.e., making accuracy for each video situa- playing status, age group, future youth

forward; midfield; wing defense; central tion was assessed using a coding criterion national team status, and playing posi-

defense) completed by all participants. of one for a correct decision (i.e., passing tion. The variables age group (rs = 0.18;

During the test, each video scene was or shooting to the best option identified p < 0.05) and playing position (rs = 0.22;

5–6 s in duration and had three possible by the expert panel) and zero for an p < 0.01) correlated with the number of

passing options; however, in the forward incorrect decision (i.e., passing or shoot- measurement points. Therefore, in a sec-

category players had the choice between ing to an option not rated the best). ond step and as an additional analysis for

German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 1 · 2021 105

Main Article

Fig. 1 8 Example of a midfield scene used within the first-person perspec-

tive video-based decision-making diagnostic instrument

the effects of age groups and playing posi-

tion, the number of measurement points

served as a manifest covariate. This was

to assess whether the number of mea-

surement points influenced the result pat-

tern and statistical decisions with respect

to age groups. As there is no statisti-

cal procedure controlling for a covariate

in nonnormal distributional properties,

ANCOVAs (analyses of covariance) were

conducted in addition to Mann–Whit-

ney-U-tests (post hoc analysis) to assess

for possible influences of the number of

measurement points on the results. Fig. 2 8 The structure of the first-person perspective video-based decision-

Effect sizes ω and Φ for nonparamet- making diagnostic instrument experimental set up

ric tests were calculated and classified in

accordance to Cohen (1992). To deter- As H2 and H3 investigated a group tus (H3; Objective II). Mann–Whitney-

mine the size of a possible population prediction, additional stepwise logistic U-tests identified significant differences

effect (within objective II and III), sensi- regressions were conducted. The overall (each p < 0.01) in decision-making com-

tivity was calculated by post hoc power model fit was examined with the like- petence between U17 and U16 (H1a;

analyses using G*Power version 3.1.9.7. lihood ratio chi-square (X2) test. The U17 > U16 in SCbu: Z = 2.35, Φ = 0.24

G*power provides sensitivity calcula- SCoff and SCbu regression coefficients as and in SCoff: Z = 3.82, Φ = 0.39), as

tions for mean comparisons between well as the odds ratios eβ and their 95% well as between U19 and U16 players

two groups only based on Cohen’s d. confidence intervals were calculated with (H1b; U19 > U16, SCbu: Φ = 0.41 and

The analyses determined the sensitivity reference to the respective selection cri- SCoff: Φ = 0.46). However, no significant

for objective II (α = 0.05, 1 – β = 0.85, teria (i.e., “reserve player” for H2; “non- differences were found between the com-

one-tailed), whereas H1 ranged from selected” for H3). Finally, individual se- parison of U19 and U17 players (H1c;

0.56 ≤ d ≤ 0.60, with H2 equal to d = 0.47, lection probabilities were determined for U17 > U19 in SCbu: Z = 0.04, p = 0.48 and

and H3 equal to d = 0.77. Regarding ob- playing status and future youth national U19 > U17 in SCoff: Z = 0.69, p = 0.244).

jective III, the power analyses (α = 0.05, team status on the basis of a player’s SCoff In relation to playing status (H2) first-

1 – β = 0.85, two-tailed) provided a range and SCbu. team regular players performed signif-

of 0.57 ≤ d ≤ 0.76. Therefore, medium icantly better than reserve players in

effect sizes could be detected within the Results both build-up and offensive situations,

present study. As the present study uti- with low to moderate effect sizes (SCbu:

lized Φ as an effect size, this corresponds Instrumental reliability demonstrated Z = 2.57, Φ = 0.22, p < 0.01 and SCoff:

to a range of Φ between 0.30 and 0.50. satisfactory values for build-up scenes Z = 1.69, Φ = 0.14, p < 0.05). With re-

Due to the fact that only three measure- (r = 0.72), and lower for offensive scenes spect to the stepwise logistic regression,

ment points are available for a very small (r = 0.56; Objective I). . Table 2 presents only build-up situations showed signif-

number of players, a longitudinal study an overview of the decision-making icance and therefore remained in the

was omitted. scores relative to age (H1) playing status model (χ2(1) = 8.00, p < 0.01). The odds

(H2) and future youth national team sta- ratios e β from the logistic regression

106 German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 1 · 2021

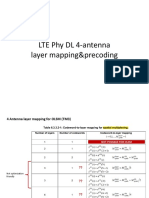

Table 2 Descriptive and inferential statistics for criterion-related validity with regards to age group (Objective II, H1), playing status (Objective II, H2),

future youth national team players (Objective II, H3), and the explorative analysis of playing position (Objective III)

Variables Decision Descriptive Effect size

accuracy statistics Post hoc analysis/Mann–Whitney U-test Kruskal–Wallis

score (%) (M ± SD) test

Age group U16 U17 U19 U16 vs. U17 U16 vs. U19 U17 vs. U19

(N = 41) (N = 55) (N = 44)

Φ

SCbu 66 ± 14 73 ± 14 71 ± 18 0.24** 0.41** 0.00

SCoff 63 ± 11 74 ± 13 75 ± 14 0.39** 0.46** 0.00

Playing status FTRP RP FTRP vs. RP

(N = 70) (N = 68)

Φ

SCbu 74 ± 13 67 ± 17 0.22**

SCoff 73 ± 13 69 ± 15 0.14*

Youth national team Selected Nonselected Selected vs.

(N = 16) (N = 70) nonselected

Φ

SCbu 73 ± 11 65 ± 16 0.20*

SCoff 69 ± 11 66 ± 13 0.08

Playing positiona DF MF FW DF vs. MF DF vs. FW MF vs. FW

(N = 55) (N = 61) (N = 24)

Φ ω

SCbu 71 ± 16 72 ± 13 63 ± 17 0.00 0.21 0.25* 0.44#

SCoff 70 ± 16 73 ± 13 69 ± 9 0.07 0.07 0.15 0.15

FTRP First team regular player, RP Reserve player, DF Defenders, MF Midfielders, FW Forwards, SCbu Decision accuracy score for build-up, SCoff Decision

accuracy score for offensive

**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05; # p < 0.10

a

Playing position correlated significantly with the number of measurement points. However, ANCOVAs (analysis of covariance) with the main factor playing

position and the covariate number of measurement points demonstrated no changes in the statistical decisions regarding the multiple group comparison.

Thus, the results pattern for playing position is independent of the number of measurement points

model indicated that a one standard up score improved the chance of being tical decisions regarding the multiple

deviation (SD = 0.153) increase in build- selected for a future youth national team group comparisons of playing position.

up score, improved the chance of being by a factor of 1.89 (= (eβ)0.153 = 64.200.153).

a first-team regular player by a factor of Regarding playing position (Objec- Discussion

1.65 (= (e β )0.153 = 26.690.153). tive III), the results for the different

With respect to the prognostic va- subsamples (i.e. DF, MF, FW) in both The aim of this study was to develop

lidity (H3), Mann–Whitney-U-test build-up and offensive decision category a valid video-based decision-making

demonstrated that selected players ranged in mean from 69–72% with only diagnostic instrument which presented

have a higher decision-making accu- one exception (i.e., the result of 63% footage from a first-person perspective

racy than nonselected players in build- from FW deviated in their nonposition- and incorporated a soccer-specific mo-

up (Z = 1.82, Φ = 0.20, p < 0.05) and of- specific build-up category compared to tor response. A further strength of the

fensive (Z = 0.78, p = 0.217) situations; other playing positions distinctly). De- study was the video stimuli were not

however, only build-up situations pro- spite these facts, the Kruskal–Wallis tests limited to one game situation, but rather

vided a significant difference. Analyzing did not reveal significant differences in different situations (i.e., build-up and of-

the prediction of future youth national any decision-making competence (SCbu: fensive decisions). While there were no

team status with regard to the logistic H(2) = 5.26, p = 0.072; SCoff: H(2) = 1.81, differences between playing positions,

regression models led to the same re- p = 0.404). In terms of possible influ- the study does provide a foundation

sult as for the playing status variable. ences caused by correlations between for future research. In particular, the

Only build-up score demonstrated sig- the manifest variable, the number of diagnostic instrument was developed as

nificance and therefore remained in the measurement points, and the indepen- a measure to discriminate decision-mak-

model (χ2(1) = 4.15, p < 0.05). A one dent variable playing position, ANCOVA ing competence within a group of youth

standard deviation increases in build- demonstrated no changes in the statis- high-performance level players. Results

German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 1 · 2021 107

Main Article

showed the diagnostic instrument, which these situations by exchanging current enough to differentiate performance of

included realistic soccer video-scenes in lower reliability clips with newly devel- high-performing late adolescent athletes

combination with a soccer-specific mo- oped higher reliability clips. Also adding requires further investigation. A possi-

tor response, is a suitable instrument more items to the diagnostic instrument ble explanation as to why there was no

for discriminating playing status and could be an approach for improving significant difference between the U17

partially for age (U19 and U17 > U16). the reliability and even reduce the need and U19 players (H1c) could be due to

Further, it provides a more representa- for large sample sizes (Schweizer et al., at least two possible reasons. First, from

tive assessment compared to previous 2020). the perspective of the U19 team, the

studies where the diagnostic instrument This study advances current sport- best players from the squad had already

was limited by a lack of a soccer-specific based decision-making literature by played for the senior professional team

response (e.g., Bennett, Novak, Pluss, demonstrating the ability to develop (i.e., in either the first or reserve/second

Coutts, & Fransen, 2019). An additional a decision-making diagnostic instru- team) and therefore were not able to

aim was to examine the predictive value ment in which the process of visual participate in the investigation. In rela-

of the new video-based decision-making perception of in-game video-scenes (i.e., tion to the U17 group, two of the three

diagnostic instrument, with the findings first person perspective) is more chal- U17 cohort squads in this study were

indicating that in parts of the study (i.e., lenging by an additional soccer-specific very successful and participated in the

in build-up categories) future youth na- motor action (i.e., dribbling) and re- finals of the German U17 championship

tional team players perform better in the sponse (i.e. passing). Traditional video- (i.e., the highest level of competition at

decision-making diagnostic instrument. based instruments which assess decision- this age). Therefore, it seems feasible

Using reliable diagnostic instruments making performance generally present that despite the age difference with re-

is fundamental to scientific work. The footage from a broadcast (i.e., television spect to U19 group, both groups were of

implications associated with using a di- broadcast) or third person perspective a very similar performance level (limit-

agnostic instrument with a lack of, or associated with nonsoccer-specific de- ing the studies’ internal reliability with

unknown, reliability is whether the par- cision response (i.e., written, verbal or regard to discriminating between age

ticipant performance differences are due button response). In this context, Mann, groups). Second, this finding supports

to random test error or actual per- Farrow, Shuttleworth, Hopwood, and other studies to investigate age-related

formance changes of the participants MacMahon (2009) indicated using a di- soccer-specific performance skill differ-

(Gadotti, Vieira, & Magee, 2006). In agnostic instrument from first person- ences. For example, Huijgen, Elferink-

comparison to the assessment of manifest perspective is more realistic. However, Gemser, Post, and Visscher (2010) high-

variables (e.g., time, height, distance), it was noted this may be more difficult lighted there were no improvements

the measurement of latent constructs from a decision-making perspective than from ages 16 to 19 in dribbling and

such as decision-making competence using footage from an aerial perspective, sprinting, which the authors attributed

poses a much larger challenge. While and therefore may provide more robust to the end of puberty. Furthermore,

researchers have highlighted the limited diagnostic instruments. Furthermore, it Beavan et al. (2019) revealed in a battery

reporting of reliability for new diagnos- has been suggested the lack of sport-spe- of cognitive function tests (e.g., Vienna

tic instruments (Hadlow et al., 2018; cific responses may limit the correlation Test System, which measures inhibition

Schweizer, Furley, Rost, & Barth, 2020), between video-based tests and actual and cognitive flexibility) that there were

a key aim of the current study was to in-game decision-making performance no differences between U19 and U17 age

measure the reliability of the latent con- (e.g., van Maarseveen et al., 2016). This groups. At this stage, further research

struct decision-making (Objective I). is further supported by Travassos et al. is needed to explore whether there are

Here, an adequate level of reliability (2013) who indicated that perceptual- peak developmental phases for cognitive

for the build-up situations was found; cognitive assessments need to consider factors such as decision-making.

however, the lower reliability for offen- the task representativeness when de- A strength of this study is that the

sive situations has to be considered as veloping sport-specific diagnostic in- sample consisted of participants from

a larger limitation. A potential reason struments. By developing assessments, one of the most successful youth soccer

for the lower reliability of the offensive which consider representative task con- academies in Germany, thus, result-

situations could be due to the restric- straints, such as presenting decision- ing in a very homogeneous high-level

tion of range phenomenon within the making situations from a first-person group. This is not a common approach

high-performance level group (i.e., ho- perspective, combined with a sport- used by researchers investigating soccer-

mogeneous expert samples) the study specific motor response, enhances the specific decision-making skills as they

was conducted (Schweizer et al., 2020). validity of the assessment measure. have generally conducted cross-sectional

Despite this limitation, the current study While the current study demonstrated studies comparing and identifying skill

does provide a method for establishing the ability to differentiate U16 and older differences between groups of high-

the reliability of the offensive decision- adolescent athletes (i.e., U17 and U19, performance and low-performance level

making situations. In addition, future objective II), developing a decision- participants (i.e., sub-elite; intermediate;

studies may improve the reliability of making diagnostic instrument sensitive novice participants; Diaz et al., 2011;

108 German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 1 · 2021

jective III). However, while assump-

tions were based on previous investiga-

tions which have demonstrated differ-

ences based on playing positions (e.g.,

Höner, 2005), the current findings did not

reveal a significant difference. Despite

this finding, the novel approach used in

the study (i.e., provide the players video-

scenes from different playing positions

Fig. 3 9 Selection on the pitch) may enable more detailed

probabilities ob-

tained from the lo- comparisons between playing positions

gistic regression in future. Hence, research should divide

for reaching first playing positions in a stricter manner,

team regular player for instance when considering the posi-

(FTRP) and for draft- tion of a forward, there may be specific

ing youth national

team (YNT) status differences between central forwards and

wide forwards (i.e., wingers).

As this is one of the first studies to

Roca et al., 2012; Scharfen & Memmert, course) by a factor of 1.89. The probabil- develop a decision-making diagnostic in-

2019). Therefore, while the findings of ity curve (. Fig. 3) increased more rapidly strument which links visual perception of

the current study indicated only a small for higher SCbu values and therefore re- first-person video scenes and soccer-spe-

significant effect size for discriminat- sults proved the diagnostics’ prognostic cific motor responses in the assessment,

ing playing status (H2), the possible relevance, as participants who perform the findings should be considered with

reason for this may be attributed to the better on the assessment are also more respect to several limitations. First, the

high sensitivity when comparing athletes likely to be selected. This finding sup- execution-time of decision-making was

within a homogeneous high-level group. ports other video-based research which not measured directly. Decision-making

This supports previous findings by van has demonstrated the ability to predict se- was only restricted by the length of the

Maarseveen et al. (2016) who also failed lectionintohighperforming youthsoccer video scenes and a marked limiting line.

to detect significant differences in per- programs (O’Connor et al., 2016). This Currently, there are different opinions

ceptual-cognitive skills between talented indicates the possibility for a video-based about the importance of execution time

female soccer players of a comparable diagnostic instrument with a soccer-spe- with respect to decision-making. There

highly skilled performance level (i.e., cific motor response to be used within seems to be the belief that experienced

national soccer talent team). Never- the talent identification process to assist players make quicker and more accurate

theless, the logistic regression models with the assessment of players’ decision- decisions compared to less skilled play-

demonstrated that players with good making performance. The nonparamet- ers (Vaeyens, Lenoir, Williams, Mazyn, &

decision accuracy on the diagnostic in- ric analysis demonstrated a small signifi- Philippaerts, 2007). Nevertheless, a fur-

strument will have a higher probability cant effect size for SCbu and no significant ther development of the diagnostic in-

of being a first team regular player (SCbu: difference for SCoff between selected and strument could include the measurement

Odds Ratio = 1.65; . Fig. 3). Therefore, nonselected future youth national team of execution-time to determine whether

the results provide initial evidence to players. However, this finding may have highly skilled players decide faster than

suggest the new diagnostic instrument been limited by the relatively low num- less skilled players or whether they wait

can potentially identify more skilled ber of participants selected into national even longer for the perfect moment to ex-

individuals within a high-performance youth programs (N = 16). Therefore, fu- ecute the appropriate response. Second,

level youth group. ture research should consider increasing the current sample was limited by the re-

Further, in comparison to previous the number of national youth players in strictions of testing within a professional

investigations which only assessed per- the sample to fully understand the po- sporting club environment. As such, sev-

formance using a cross-sectional design tential decision-making skill differences eral high-performing U19 athletes were

(e.g., Höner, 2005), the current investi- between these high performing players not included in the sample due to pro-

gation implemented a prospective design (i.e., selected; nonselected for youth na- fessional club commitments. As a result,

to allow for a greater understanding of tional team; Ackerman, 2014). it may be possible that the lack of signif-

potential future soccer success (H3). The The present study extended the cur- icant differences between U17 and U19

logistic regression model for SCbu indi- rent research knowledge related decision- players in the current sample may not

cated that players who performed well on making assessments by developing a di- fully describe the potential age-related

the assessment improved the chance of agnostic instrument which incorporated differences between these two groups.

being selected (i.e., selected to participate decision situations from defense, mid- Therefore, future investigations should

in a German youth national team training field, and forward playing positions (Ob- aim to sample all athletes from within an

German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 1 · 2021 109

Main Article

age group to ensure a true representation formance youth group, in particular for Funding. Open Access funding enabled and orga-

nized by Projekt DEAL.

of the performance group. Finally, sim- playing status and to some extent age.

ilar to other studies (e.g., Höner, 2005), Although the reliability of the diagnostic

this study limited the number of options instrument is satisfied for the build-up Compliance with ethical

(i.e., three option per situation) and the category, future research should aim for guidelines

sport-specific motor response (i.e., play- higher reliability for all measured vari-

ers only had the options to pass or shoot). ables (e.g., offensive decision), by using Conflict of interest. D. Murr, P. Larkin and O. Höner

Future studies should also consider the the guidelines proposed, for example, declare that they have no competing interests.

development of diagnostic instruments by Schweizer et al. (2020). Further, the

All procedures performed in studies involving human

which include other decision-making op- results demonstrate the predictive value participants were in accordance with the ethical stan-

tions, such as dribbling. While observa- of the new video-based decision-making dards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later

tional studies (e.g., recording decision- diagnostic instrument, especially the amendments or comparable ethical standards. The

ethics department of the Faculty of Economics and

making skills in small-sided games) such build-up situation for national youth Social Sciences at the University of Tübingen and the

as Romeas, Guldner, and Faubert (2016) team selection. However, future investi- youth academy of the professional soccer club ap-

have attempted to assess the whole spec- gations with a longer prognostic period proved the implementation of this study. All players

and legal guardians (i.e., parents) provided informed

trum of decision-making alternatives, it (e.g., up to senior level) is of interest to consent prior to participation in the study.

is a challenge developing such situations strengthen the results. With respect to

within a video stimuli. A possible alter- playing positions, no differences were Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which

native maybe developing diagnostic in- found between positions; however, fur- permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and re-

struments that provide more graduations ther examination of playing position on production in any medium or format, as long as you

of decisions (i.e., best option; second best decision-making skills is warranted (e.g., give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and

the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons li-

option; etc.), rather than current binary are midfielder better decision-makers re- cence, and indicate if changes were made. The images

forms (e.g., Bennett et al., 2019). Further, gardless on which area of the pitch the or other third party material in this article are included

off-the-ball decision-making in defensive decision-making skill is required?). in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless in-

dicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If

game situations such as positioning close Considering these results, this study material is not included in the article’s Creative Com-

or far from the ball, which has not been provides initial evidence to suggest a soc- mons licence and your intended use is not permitted

assessed in the literature, should also be cer-specific video-based diagnostic in- by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use,

you will need to obtain permission directly from the

considered in future research. strument can be used within talent identi- copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit

fication processes to assist with the assess- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Conclusion ment of players’ decision-making perfor-

mance. Finally, future decision-making

Sport-based decision-making is a cogni- assessment studies can use similar proce- References

tive process in which athletes use their dures to those employed in the current in-

knowledge about a (current) situation to vestigation to develop a valid and reliable Ackerman, P. L. (2014). Nonsense, common sense,

and science of expert performance: talent and

select an appropriate decision based on video-based decision-making diagnostic individual differences. Intelligence, 45, 6–17.

their perceived ability to execute a sport- instrument in other sports/domains. In https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2013.04.009.

specific motor skill response (Causer & addition, further exploration of the inte- Beavan, A. F., Spielmann, J., Mayer, J., Skorski, S.,

Meyer, T., & Fransen, J. (2019). Age-related

Ford, 2014). While decision-making is gration of motor specific responses with differences in executive functions within high-

defined by the ability to perceive appro- the video footage to create an even more level youth soccer players. Brazilian Journal of

priate stimuli and execute a sport-specific realistic diagnostic instrument may be Motor Behavior, 13(2), 64–75.

Bennett, K. J. M., Novak, A. R., Pluss, M. A., Coutts, A. J.,

skill response, traditional video-based possible. One approach would be to use & Fransen, J. (2019). Assessing the validity of

instruments assess decision-making us- virtual reality technology to allow body a video-based decision-making assessment for

ing nonsport-specific responses such as parts (e.g., foot) interacting with the stim- talent identification in youth soccer. Journal of

Science and Medicine in Sport, 22(6), 729–734.

verbal, written, or button responses (e.g., ulus material or to measure a player’s in https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2018.12.011.

Roca et al., 2012). This study addressed situ task constraints. Bergkamp, T. L. G., Niessen, A. S. M., den Hartigh, R. J. R.,

this limitation by developing a valid Frencken, W. G. P., & Meijer, R. R. (2019). Method-

ological issues in soccer talent identification

first-person perspective video-based Corresponding address research. Sports Medicine. https://doi.org/10.

diagnostic instrument which requires 1007/s40279-019-01113-w.

a soccer-specific motor response (i.e., Dennis Murr Bonney, N., Berry, J., Ball, K., & Larkin, P. (2019).

Institute of Sports Science, Australian football skill-based assessments: a

participants dribble with the ball while proposed model for future research. Frontiers

Eberhard Karls University

watching a video stimulus and then exe- Tübingen, Germany in Psychology, 10, 429–429. https://doi.org/10.

cute their decision by passing to a player 3389/fpsyg.2019.00429.

dennis.murr@uni-

Boone, J., Vaeyens, R., Steyaert, A., Vanden Bossche,

in the video). The results indicate the tuebingen.de L., & Bourgois, J. (2012). Physical fitness of

© Mario

video-based decision-making diagnostic elite Belgian soccer players by player position.

Heilemann Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research,

instrument can discriminate decision-

making competence within a high-per-

110 German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 1 · 2021

26(8), 2051–2057. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC. soccer? Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, a meta-analytic review. Applied Cognitive

0b013e318239f84f. 28(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/ Psychology, 33(5), 843–860.

Causer, J., & Ford, P. R. (2014). ‘Decisions, decisions, 10413200.2015.1085922. Schweizer, G., Furley, P., Rost, N., & Barth, K.

decisions’: transfer and specificity of decision- Lex, H., Essig, K., Knoblauch, A., & Schack, T. (2020). Reliable measurement in sport

making skill between sports. Cognitive (2015). Cognitive representations and cognitive psychology: The case of performance outcome

Processing, 15(3), 385–389. https://doi.org/10. processing of team-specific tactics in soccer. measures. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 48,

1007/s10339-014-0598-0. PLoS One, 10(2), e118219. https://doi.org/10. 101663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current 1371/journal.pone.0118219. 2020.101663.

Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101. Lienert, G. A., & Raatz, U. (2011). Testaufbau Travassos, B., Araujo, D., Davids, K., O’hara, K., Leitão,

Deprez,D.,Fransen,J.,Boone,J.,Lenoir,M.,Philippaerts, und Testanalyse [Setup and analysis of tests]. J., & Cortinhas, A. (2013). Expertise effects

R., & Vaeyens, R. (2015). Characteristics of high- Weinheim: Beltz. on decision-making in sport are constrained

level youth soccer players: variation by playing Lorains, M., Ball, K., & MacMahon, C. (2013). Expertise by requisite response behaviours—A meta-

position. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(3), differences in a video decision-making task: analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(2),

243–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414. speed influences on performance. Psychology of 211–219.

2014.934707. Sport and Exercise, 14(2), 293–297. https://doi. Vaeyens, R., Lenoir, M., Williams, A. M., Mazyn, L.,

Diaz, D. C. D., Gonzalez, V. S., Garcia, L. L., & Mitchell, org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.11.004. & Philippaerts, R. M. (2007). The effects of

S. (2011). Differences in decision-making van Maarseveen, M. J. J., Oudejans, R. R. D., Mann, task constraints on visual search behavior and

development between expert and novice D. L., & Savelsbergh, G. J. P. (2016). Perceptual- decision-making skill in youth soccer players.

invasion game players. Perceptual and motor cognitive skill and the in situ performance Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(2),

skills, 112(3), 871. of soccer players. The Quarterly Journal of 147–169.

Dieze, S. (2015). Positionsspezifische Diagnostik der Experimental Psychology. https://doi.org/10. Ward, P., & Williams, A. M. (2003). Perceptual and

Entscheidungskompetenz im Fußball: Entwick- 1080/17470218.2016.1255236. cognitive skill development in soccer: the

lung und erste Validierung einer Videotestbatterie Mann, D., Dehghansai, N., & Baker, J. (2017). multidimensional nature of expert performance.

[Position-specific diagnostics of decision-making Searching for the elusive gift: advances in Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 25(1),

in soccer: developing and validation of a video- talent identification in sport. Current Opinion in 93–111.

based test battery]. Tübingen: Eberhard Karls Psychology, 16(SupplementC), 128–133. https:// Ward, P., Ericsson, K. A., & Williams, A. M. (2013).

Universität Tübingen. doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.016. Complex perceptual-cognitive expertise in

Frýbort, P., Kokštejn, J., Musálek, M., & Süss, V. (2016). Mann, D., Farrow, D., Shuttleworth, R., Hopwood, a simulated task environment. Journal of

Does physical loading affect the speed and M., & MacMahon, C. (2009). The influence of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 7(3),

accuracy of tactical decision-making in elite viewing perspective on decision-making and 231–254.

junior soccer players? Journal of Sports Science & visual search behaviour in an invasive sport. Williams, A. M., & Reilly, T. (2000). Talent identification

Medicine, 15(2), 320–326. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 40(4), and development in soccer. Journal of Sports

Gadotti, I., Vieira, E., & Magee, D. (2006). Importance 546–564. Sciences, 18(9), 657–667.

and clarification of measurement properties Murr, D., Feichtinger, P., Larkin, P., O’Connor, D., Wilson, R. S., James, R. S., David, G., Hermann, E.,

in rehabilitation. Brazilian Journal of Physical & Höner, O. (2018). Psychological talent Morgan, O. J., Niehaus, A. C., et al. (2016).

Therapy, 10(2), 137–146. predictors in youth soccer: a systematic review Multivariate analyses of individual variation in

Hadlow, S. M., Panchuk, D., Mann, D. L., Portus, M. R., of the prognostic relevance of psychomotor, soccer skill as a tool for talent identification and

& Abernethy, B. (2018). Modified perceptual perceptual-cognitive and personality-related development: utilising evolutionary theory in

training in sport: a new classification framework. factors. PLoS One, 13(10), e205337. https://doi. sportsscience. Journal of Sports Sciences. https://

Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 21(9), org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205337. doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1151544.

950–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2018. O’Connor, D., Larkin, P., & Williams, A. M. (2016). Woods, C. T., Raynor, A. J., Bruce, L., & McDonald,

01.011. Talent identification and selection in elite youth Z. (2016). Discriminating talent-identified

Hagemann, N., Lotz, S., & Cañal-Bruland, R. (2008). football: an Australian context. European Journal junior Australian football players using a video

Wahrnehmungs-Handlungs-Kopplung beim of Sport Science, 16(7), 837–844. https://doi.org/ decision-making task. Journal of Sports Sciences,

taktischen Entscheidungstraining: Eine ex- 10.1080/17461391.2016.1151945. 34(4), 342–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/

ploratorische Studie [Perceptual-action-cou- Pocock, C., Dicks, M., Thelwell, R. C., Chapman, 02640414.2015.1053512.

pling in tactical decision-making training: an M., & Barker, J. B. (2019). Using an imagery

explorative study]. E-Journal Bewegung und intervention to train visual exploratoryactivityin

Training, 2, 17–27. eliteacademyfootballplayers. Journal of Applied

Höner, O. (2005). Entscheidungshandeln im Sportspiel Sport Psychology, 31(2), 218–234.

Fußball: Eine Analyse im Lichte der Rubikontheo- Rago, V., Pizzuto, F., & Raiola, G. (2017). Relationship

rie [Decision making in football—An analysis in between intermittent endurance capacity and

the context of the Rubicon theory]. Schorndorf: match performance according to the playing

Hofmann. position in sub-19 professional male football

Höner, O., Larkin, P., Leber, P., & Feichtinger, P. players: preliminary results. Journal of Physical

(2020). Talentauswahl und -entwicklung Education and Sport, 17(2), 688.

im Sport. In J. Schüler, M. Wegner & Roca, A., Williams, A. M., & Ford, P. R. (2012).

H. Plessner (Eds.), Sportpsychologie: Grundlagen Developmental activities and the acquisition of

und Anwendung [Textbook of sports psychology: superior anticipation and decision making in

basics and application] (pp. 499–530). Berlin, soccer players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(15),

Heidelberg, New York: Springer. 1643–1652. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.

Huijgen, B. C. H., Elferink-Gemser, M. T., Post, W., & 2012.701761.

Visscher, C. (2010). Development of dribbling in Romeas, T., Guldner, A., & Faubert, J. (2016). 3D-

talented youth soccer players aged 12–19 years: Multiple Object Tracking training task improves

a longitudinal study. Journal of Sports Sciences, passing decision-making accuracy in soccer

28(7), 689–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/ players. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 22, 1–9.

02640411003645679. Ruiz Pérez, L. M., Palomo Nieto, M., García Coll, V.,

Johnston, K., Wattie, N., Schorer, J., & Baker, J. (2018). Navia Manzano, J. A., Miñano Espín, J., & Psotta,

Talent identification in sport: a systematic R. (2014). Self-perceptions of decision making

review. Sports Medicine, 48(1), 97–109. https:// competence in Spanish football players. Acta

doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0803-2. Gymnica, 44(2), 77–83.

Larkin, P., O’Connor, D., & Williams, A. M. (2016). Does Scharfen, H. E., & Memmert, D. (2019). Measurement of

grit influence sport-specific engagement and cognitive functions in experts and elite athletes:

perceptual-cognitive expertise in elite youth

German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 1 · 2021 111

You might also like

- Introduction To OpendTectDocument382 pagesIntroduction To OpendTectHenrique Moreira SantanaNo ratings yet

- Rocks and The Rock Cycle: Powerpoint PresentationDocument39 pagesRocks and The Rock Cycle: Powerpoint PresentationPriana100% (6)

- Vision 2047 November 2023Document53 pagesVision 2047 November 2023Soham SamantaNo ratings yet

- Periodization and Programming For Team Sports - Supplement PDFDocument38 pagesPeriodization and Programming For Team Sports - Supplement PDFAkshai Suresh C100% (1)

- FIFA 18 - Data Analysis: - Harsh Takrani - Pranay LullaDocument16 pagesFIFA 18 - Data Analysis: - Harsh Takrani - Pranay LullaSovan DashNo ratings yet

- Floorball - Individual Technique and TacticsDocument57 pagesFloorball - Individual Technique and Tacticsdavosian89% (9)

- Transfer Case 4405 PDFDocument2 pagesTransfer Case 4405 PDFadriangalindo2009No ratings yet

- Differential Learning As A Key TrainingDocument15 pagesDifferential Learning As A Key TrainingRicardo PaceNo ratings yet

- نظرة عامة على المسحDocument10 pagesنظرة عامة على المسحOmar AbdelazizNo ratings yet

- Football, The Philosophy Be (Z-Library)Document74 pagesFootball, The Philosophy Be (Z-Library)abelabebe2023No ratings yet

- Team Analysis CheslerDocument24 pagesTeam Analysis CheslersaratvegaNo ratings yet

- Annual Calender 2023-24Document12 pagesAnnual Calender 2023-24pulkitmNo ratings yet

- 4-2-3-1 Attaking Style For FM 17Document3 pages4-2-3-1 Attaking Style For FM 17Budui DanielNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: Activity Name Description Diagram Purpose/Coaching PointsDocument4 pagesLesson Plan: Activity Name Description Diagram Purpose/Coaching PointspklNo ratings yet

- Seu Game ModelDocument37 pagesSeu Game ModelnickcowellNo ratings yet

- Coaches Circle Issue 6 - May 2021Document24 pagesCoaches Circle Issue 6 - May 2021เซบาสเตียน ไลฟ์ลีดเดอร์No ratings yet

- FP Parent Handbook 2023 24Document33 pagesFP Parent Handbook 2023 24amanogho.adidiNo ratings yet

- Optimizing The Use of Soccer Drills For Physiological DevelopmentDocument8 pagesOptimizing The Use of Soccer Drills For Physiological DevelopmentS HNo ratings yet

- Coaching and Games Development in - The Club PDFDocument12 pagesCoaching and Games Development in - The Club PDFGreggC66No ratings yet

- العاب ترفيهية بكرة القدمDocument23 pagesالعاب ترفيهية بكرة القدمjaimito jmgmmm2726yahoo.comNo ratings yet

- Shivraj Vilas Patil. Annual Plan U11Document26 pagesShivraj Vilas Patil. Annual Plan U11shivrajpatil1527No ratings yet

- The ManifestoDocument4 pagesThe ManifestoriverbendfcNo ratings yet

- EasiCoachU7 U8Document90 pagesEasiCoachU7 U8RICHARD SARDON LEONNo ratings yet

- GROUND ZERO ACADEMY CRITERIA Ver 2Document33 pagesGROUND ZERO ACADEMY CRITERIA Ver 2oxionzNo ratings yet

- Learn To Train - WebDocument24 pagesLearn To Train - WebHurairah M HMNo ratings yet

- Position Training Attack: Marcel Lucassen, DFB TrainersDocument10 pagesPosition Training Attack: Marcel Lucassen, DFB Trainersadu rawdiNo ratings yet

- Skill Soccer1Document20 pagesSkill Soccer1api-401557091No ratings yet

- EvanDocument20 pagesEvanMartin Paul Embile GabitoNo ratings yet

- MUFC2015 Player - Transfer AnalysisDocument30 pagesMUFC2015 Player - Transfer AnalysisJose MoonrinhoNo ratings yet

- Gronnemark Football360 2021Document19 pagesGronnemark Football360 2021ryan.lazaroeNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Approach To Developing Sporting Excellence: Insights From FC Barcelona'S La Masia'Document5 pagesAn Integrative Approach To Developing Sporting Excellence: Insights From FC Barcelona'S La Masia'Taktik BolaNo ratings yet

- Red BullsDocument39 pagesRed BullsMensur SmigalovicNo ratings yet

- Receng Trends in High Intensity Aerobic - Training PDFDocument6 pagesReceng Trends in High Intensity Aerobic - Training PDFPablo100% (1)

- Attacking 442Document3 pagesAttacking 442abeyassineNo ratings yet

- Football Resurse KitDocument14 pagesFootball Resurse KitViktor GenovNo ratings yet

- Uefa A 2014 Oppgave Luis PimentaDocument45 pagesUefa A 2014 Oppgave Luis PimentaAmin CherbitiNo ratings yet

- Small Sided Games Book Layout 1Document67 pagesSmall Sided Games Book Layout 1latierrajlNo ratings yet

- Testing Speed and Agility in Elite Tennis Players.13Document4 pagesTesting Speed and Agility in Elite Tennis Players.13Mohd HafizzatNo ratings yet

- 3v3 UK Training ManualDocument45 pages3v3 UK Training ManualrpntbpvcwrNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Contrast Training Program Without External Load On Vertical Jump, Kicking Speed, Sprint, and Agility of Young Soccer Players PDFDocument9 pagesEffects of A Contrast Training Program Without External Load On Vertical Jump, Kicking Speed, Sprint, and Agility of Young Soccer Players PDFNiña AlviaNo ratings yet

- FAS Grassroots Coaching Course Workbook 2016 EditionDocument68 pagesFAS Grassroots Coaching Course Workbook 2016 Editionjun chen100% (1)

- The Mlu Player Development Curriculum U10Document14 pagesThe Mlu Player Development Curriculum U10Sabah TourNo ratings yet

- 2010 - 06 - 28 World Cup 2010, GHANA - USA, Professional Tips For Coaches, Players, Referees & ManagersDocument13 pages2010 - 06 - 28 World Cup 2010, GHANA - USA, Professional Tips For Coaches, Players, Referees & ManagersDr. Victor StanculescuNo ratings yet

- Sia Methodology: Technical AreaDocument9 pagesSia Methodology: Technical AreaKhusnul YaqienNo ratings yet

- Gareth Southgate Creative Attacking PlayDocument15 pagesGareth Southgate Creative Attacking PlayCaptain-Ramadan Al-zubidyNo ratings yet

- 2014 - RGP - North Julian - Youth Development in Seven Countries - Final ReportDocument126 pages2014 - RGP - North Julian - Youth Development in Seven Countries - Final Reportmojtabamorshed100% (1)

- Speed Training Practices of Brazilian Olympic Sprint and JumpDocument25 pagesSpeed Training Practices of Brazilian Olympic Sprint and Jump超卓No ratings yet

- Player Development in FinlandDocument17 pagesPlayer Development in FinlandkrasimirNo ratings yet

- Asb Football in School Programme Updated DocoDocument45 pagesAsb Football in School Programme Updated Docoapi-246218373No ratings yet

- Game-Model 1Document24 pagesGame-Model 1Ricardo PaceNo ratings yet

- Fitnessgram / Activitygram: Test Administration ManualDocument152 pagesFitnessgram / Activitygram: Test Administration ManualDonald Glover0% (1)

- Periodize Your Game: PeriodizationDocument3 pagesPeriodize Your Game: PeriodizationFioravanti AlessandroNo ratings yet

- Playing With The Ball: Individual Training and Coaching Within The Team TrainingDocument4 pagesPlaying With The Ball: Individual Training and Coaching Within The Team Trainingadu rawdiNo ratings yet

- UEFA Study Group Report - PortugalDocument26 pagesUEFA Study Group Report - PortugalSoccerCTC100% (1)

- Effects of Aerobic Training On Soccer PerformanceDocument3 pagesEffects of Aerobic Training On Soccer PerformanceNikos NikidisNo ratings yet

- The Threats of Small-Sided Soccer Games A Discussion About TheirDocument6 pagesThe Threats of Small-Sided Soccer Games A Discussion About TheirPabloAñonNo ratings yet

- Great Britain Hockey 93026 GBH Talent Development Framework BookletDocument28 pagesGreat Britain Hockey 93026 GBH Talent Development Framework Booklet43AJF43No ratings yet

- Mission Soccer: From The Good Men Project MagazineDocument16 pagesMission Soccer: From The Good Men Project MagazineGoodMenProject100% (1)

- Goalkeeping Intelligence MANIFESTODocument9 pagesGoalkeeping Intelligence MANIFESTOAdam WoodageNo ratings yet

- Feasibilityreport Group2Document43 pagesFeasibilityreport Group2Devika RainaNo ratings yet

- China and Football Report - Nielsen SportsDocument13 pagesChina and Football Report - Nielsen SportsMichael OzanianNo ratings yet

- Chapter 08 Physical Preparation and Physical Development and T 2Document52 pagesChapter 08 Physical Preparation and Physical Development and T 2Sis Wantoro100% (1)

- (Brill's Studies in Indo-European Languages & Linguistics) Hackstein, O. - Gunkel, D. - Language and Meter-Brill (2018)Document441 pages(Brill's Studies in Indo-European Languages & Linguistics) Hackstein, O. - Gunkel, D. - Language and Meter-Brill (2018)Esteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Varieties of English - A Typological ApproachDocument328 pagesVarieties of English - A Typological ApproachEsteban Lopez100% (1)

- Pedagogy For Creative Problem SolvingDocument255 pagesPedagogy For Creative Problem SolvingEsteban LopezNo ratings yet

- The Construction of Words Advances in Construction MorphologyDocument617 pagesThe Construction of Words Advances in Construction MorphologyEsteban LopezNo ratings yet

- The Art of The Question: The Structure of Questions Posed by Youth Soccer Coaches During TrainingDocument17 pagesThe Art of The Question: The Structure of Questions Posed by Youth Soccer Coaches During TrainingEsteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Ramirez Campillo Et Al 2021Document59 pagesRamirez Campillo Et Al 2021Esteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Psychometric Properties of The Motor Diagnostics in The German Football Talent Identification and Development ProgrammeDocument16 pagesPsychometric Properties of The Motor Diagnostics in The German Football Talent Identification and Development ProgrammeEsteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Practice and Play in The Development of German Top Level Professional Football PlayersDocument11 pagesPractice and Play in The Development of German Top Level Professional Football PlayersEsteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Sport and Exercise During and Beyond The Covid 19 PandemicDocument3 pagesSport and Exercise During and Beyond The Covid 19 PandemicEsteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Review of The Tactical Evaluation Tools For Youth Players Assesing The Tactics in Team Sports FootballDocument17 pagesReview of The Tactical Evaluation Tools For Youth Players Assesing The Tactics in Team Sports FootballEsteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Technical Testing and Match Analysis Statistics As Part of The Talent Development Process in An English Football AcademyDocument18 pagesTechnical Testing and Match Analysis Statistics As Part of The Talent Development Process in An English Football AcademyEsteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Aplicación de Un Programa de Entrenamiento de Fuerza en Futbolistas Jovenes PDFDocument16 pagesAplicación de Un Programa de Entrenamiento de Fuerza en Futbolistas Jovenes PDFEsteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Wilkes A - German For Beginners Languages For Beginners PDFDocument51 pagesWilkes A - German For Beginners Languages For Beginners PDFCarlos Antonio Muñoz Rubio100% (1)

- Attacking From The Back 2 Zone Possession GameDocument4 pagesAttacking From The Back 2 Zone Possession GameEsteban LopezNo ratings yet

- Skin Effect and Formation DamageDocument20 pagesSkin Effect and Formation DamageChristopher ArthurNo ratings yet

- 4 Ant DL MIMO LayerMappingPrecodingDocument14 pages4 Ant DL MIMO LayerMappingPrecodingMelih GünalNo ratings yet

- May2015 Physics Paper 3 TZ1 HL MarkschemeDocument18 pagesMay2015 Physics Paper 3 TZ1 HL MarkschemeAnanya AggarwalNo ratings yet

- DCM601A71 Intelligent Touch MGR Install ManDocument44 pagesDCM601A71 Intelligent Touch MGR Install Mandinie90No ratings yet

- Junus SInuraya (2019) Pengukuran Kualitas Website Dengan Metode WebQual 4.0Document9 pagesJunus SInuraya (2019) Pengukuran Kualitas Website Dengan Metode WebQual 4.0Fergi Argi100% (1)

- Introduction To IBM Power Systems, AIX and System Administration Unit 1Document19 pagesIntroduction To IBM Power Systems, AIX and System Administration Unit 1Richie BallyearsNo ratings yet

- ThermodynamicsDocument25 pagesThermodynamicsJean BesanaNo ratings yet

- Topographic Map of MontopolisDocument1 pageTopographic Map of MontopolisHistoricalMapsNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Psychology Frontiers and Applications 4th Fourth Canadian Edition Michael PasserDocument141 pagesTest Bank For Psychology Frontiers and Applications 4th Fourth Canadian Edition Michael PasserPhilip Neri100% (43)

- KISSsoft 2019 Tutorial 16-The-Tolerance-For-The-External-Diameter-Of-The-WormDocument17 pagesKISSsoft 2019 Tutorial 16-The-Tolerance-For-The-External-Diameter-Of-The-WormNguyễnVănLăngNo ratings yet

- E Commerce Website For Online ShoppingDocument35 pagesE Commerce Website For Online ShoppingFahim MuntasirNo ratings yet

- Adarsh Public School: Class-IiiDocument2 pagesAdarsh Public School: Class-IiiNirmal KishorNo ratings yet

- Unit 8Document3 pagesUnit 8Diana RebeccaNo ratings yet

- Fiksna Kompenzacija TransformatorDocument3 pagesFiksna Kompenzacija Transformatorts45306No ratings yet

- 2021 Exam Memo Past Paper MemoDocument16 pages2021 Exam Memo Past Paper MemomaahlewestNo ratings yet

- 001 Introduction To StreMa PDFDocument29 pages001 Introduction To StreMa PDFEj ParañalNo ratings yet

- SHS MODULE v2020 M1.3 1 1Document6 pagesSHS MODULE v2020 M1.3 1 1Peter Anton RoaNo ratings yet

- Module 2 - 3 Functions and RelationsDocument61 pagesModule 2 - 3 Functions and RelationsraydieuxxNo ratings yet

- Year 5 Full Spring TermDocument105 pagesYear 5 Full Spring TermM alfyNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S001346861530551X MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S001346861530551X Mainhenry.a.peraltaNo ratings yet

- Fluid Power With Applications 7th Edition - Chapter 1Document53 pagesFluid Power With Applications 7th Edition - Chapter 1Nadeem AldwaimaNo ratings yet

- PPAPDocument16 pagesPPAPOsvaldo Da Silva Neto100% (1)

- Swing Feel Supplement PDFDocument5 pagesSwing Feel Supplement PDFEugem CopeliusNo ratings yet

- 9 Beta 2 MicroDocument3 pages9 Beta 2 Microarpitjain01020No ratings yet

- Designing A sp3 Structure of Carbon T-C9 First-PriDocument10 pagesDesigning A sp3 Structure of Carbon T-C9 First-Pri余慶峰No ratings yet

- Calculation of K Factor Function For The Carbonation Process of Lime-Based PlastersDocument5 pagesCalculation of K Factor Function For The Carbonation Process of Lime-Based PlastersSaurav BhattacharjeeNo ratings yet

- Scheduling of Operating System Services: Stefan BonfertDocument2 pagesScheduling of Operating System Services: Stefan BonfertAnthony FelderNo ratings yet