Serendipity in Entrepreneurship: Nicholas Dew

Serendipity in Entrepreneurship: Nicholas Dew

Uploaded by

Celina LimCopyright:

Available Formats

Serendipity in Entrepreneurship: Nicholas Dew

Serendipity in Entrepreneurship: Nicholas Dew

Uploaded by

Celina LimOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Serendipity in Entrepreneurship: Nicholas Dew

Serendipity in Entrepreneurship: Nicholas Dew

Uploaded by

Celina LimCopyright:

Available Formats

article title

Serendipity in Entrepreneurship

Nicholas Dew

Abstract

Nicholas Dew This paper addresses the concept of serendipity in entrepreneurship, defined as search

Naval Postgraduate leading to unintended discovery. It conceptually delineates serendipity, showing how it is

School, Monterey, related to the entrepreneurship literature on prior knowledge and systematic search. The

USA paper also discusses how serendipitous entrepreneurship relates to some aspects of evo-

lutionary theory, socio-economic institutions, and social psychology. It is suggested that

serendipity may be a quite prevalent feature of entrepreneurship and thus has implications

for both research and practice.

Keywords: serendipity, entrepreneurship, opportunity

Introduction

‘Entrepreneurship is a series of random collisions. Sure, you start with a plan and follow

it systematically. But even though you start out in the alternative energy business, you

are just as likely to end up in real estate development.’ (David A. Padwa, founder of

Agrigenetics Corp., quoted by Silver 1985: 16)

Despite their significance, the serendipity of many events goes unrecognized

(and even denied) for long periods of time. Columbus, for instance, discovered

America’s shores while searching for a passage to India. Yet, all his life he

refused to recognize that the land he had found was not the land he had set out

to explore for; one unlikely consequence of this is that we still refer to native

Americans as ‘Indians’.

Columbus’ discovery of the ‘New World’ was, of course, an example of serendip-

ity: of making a discovery, by accident and sagacity, of things not in quest of.

Picasso’s Blue period is another well-known example of serendipity — a con-

fluence of situational factors that gave birth to a new genre of art that, though mar-

Organization

Studies velous, was quite unintended. So the story goes, Picasso had only blue paint to

30(07): 735–753 work with one day, but when he started to toy with the effects of painting with this

ISSN 0170–8406 one color, he found that interesting art could be made of it. Thus, Picasso took

Copyright © The

Author(s), 2009. what was initially a serendipitous constraint, and leveraged it into a creative result.

Reprints and In what follows, I want to suggest that serendipity also plays an important role

permissions: in entrepreneurship. For the purposes of this paper, I define serendipity as search

http://www.sagepub.

co.uk/journals leading to unintended discovery. Many entrepreneurship scholars, as well as many

permissions.nav entrepreneurs, intuitively conceptualize entrepreneurial opportunity in terms of

www.egosnet.org/os DOI: 10.1177/0170840609104815

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

736 Organization Studies 30(07)

serendipity — some combination of search (directed effort), contingency (favorable

accidents), and prior knowledge (sagacity).1 Entrepreneurship scholars have identi-

fied roles for both systematic exploration and spontaneous recognition in the litera-

ture on the discovery of opportunities (Fiet 2002; Shane 2000). Serendipity lies

between these two concepts: individuals are involved in some kind of search effort

when they accidentally discover something that they were not looking for. In this

paper, I suggest that there are good theoretical reasons for supposing that serendip-

ity has a logical place in a taxonomy of opportunity discovery, based on a framework

that shows how the concepts of systematic exploration, spontaneous recognition,

and serendipity have related conceptual underpinnings. My suggestion is that a

theory of entrepreneurship is therefore likely to be incomplete without the concept

of serendipity and that, once a non-trivial place has been located for serendipity in

entrepreneurial behavior, several implications follow for research and practice.

The paper deals with these points as follows. The next section describes the

concept of serendipity and offers a framework that integrates serendipity within

the entrepreneurship literature. The following section discusses how serendipi-

tous entrepreneurship relates to some aspects of evolutionary theory, socio-

economic institutions, and social psychology. A subsequent section deals with

implications for research and practice. Brief concluding remarks follow.

The Concept of Serendipity

Serendipity is an ambiguous word. It combines the notions of (fortunate) ‘acci-

dent’ with ‘sagacity’, which means acute mental discernment and a keen practi-

cal sense. Modern Webster’s dictionaries define serendipity as ‘an aptitude for

making desirable discoveries by accident’, but this definition arguably just fol-

lows a modern trend which highlights the sagacity in serendipity and demotes

the equally important components of search and good fortune in the term

(Merton and Barber 2004).

A well-known and excellent example of serendipity in scientific discovery —

Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928 — helps illustrate the meaning of the

term. Despite the fact that other researchers had noted the antibacterial effects

of penicillin, it was Fleming who is widely credited with its discovery. First,

Fleming was actively searching for a discovery when he found penicillin.

Second, the fortunate accident was that Fleming was cleaning up his laboratory

when he noticed how penicillin mold had contaminated one of his old experi-

ments — a completely unanticipated contingency. Third, sagacity enters the

story because Fleming had been experimenting with the antibacterial properties

of common substances for many years, and therefore had enough prior knowl-

edge about molds to find that particular petri dish anomalous, and immediately

begin to discern its potential implications.

The vast majority of research on serendipity involves scientific discoveries such

as Fleming’s. Both Merton and Barber (2004) and Roberts (1989) provide a com-

pendium of serendipitous discoveries in science. In addition, there are a very large

number of discussions of the nature of serendipity in a wide variety of papers on

scientific discovery (Van Andei 1994). Between 1950 and 2003 there were at least

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

Dew: Serendipity in Entrepreneurship 737

832 publications across all branches of science with ‘serendipity’ or ‘serendipitous’

in their title (University of Pennsylvania 2004). In fact, the regularity with which

serendipitous discoveries are made in science has led some historians to describe

serendipity as a significant factor in the evolution of science (Kantorovich and

Neeman 1989). Over the years, a great many scientists have also directly expressed

their views about the importance of serendipity in scientific work, perhaps none

more colorfully than the 19th-century French physiologist Bernard:

‘Experimental ideas are often born by chance, with the help of some casual observation.

Nothing is more common: and this is really the simplest way of beginning a piece of sci-

entific work. We take a walk, so to speak, in the realm of science, and we pursue what

happens to present itself to our eyes. Bacon compares scientific investigation with hunt-

ing: the observations that present themselves are the game. Keeping the game simile, we

may add that, if the game presents itself when we are looking for it, it may also present

itself when we are not looking for it, or when we are looking for game of another kind.’

(Bernard 1865, quoted in Van Andei 1994: 635)

As well as the idea of serendipity, there is also the idea of pseudo serendipity, which

refers to a situation in which someone is looking for something in particular, but the

route by which they discover it is accidental and unanticipated. For instance, Charles

Goodyear made many attempts to stabilize natural rubber so that it could be made

useful, but it was only when he accidentally allowed a mixture of rubber and sulfur

to touch a hot stove that he discovered vulcanization (Roberts 1989: 54). Similarly,

Alfred Nobel had experimented extensively with ways of taming nitroglycerin, but

it was an accidentally cut finger that prompted him to experiment with a mixture of

collodion (commonly applied to wounds in Nobel’s day) and nitroglycerin, a com-

bination that was later patented as blasting gelatin, and is still used to this day.

There are diverse examples of serendipity in entrepreneurship. The founding

of Staples office supply retail chain provides one example of the serendipitous

discovery of an underserved market (Sarasvathy 2007). On the Thursday before

the Fourth of July weekend in 1985, Thomas Stemberg, who had recently lost

his job as division manager for a supermarket chain, was working on a business

plan for starting a new chain, when he ran out of the printer ribbon for his Apple

Imagewriter. When he went out to purchase a new ribbon, he simply could not

get it. Either stationery stores had closed early for the weekend, or the ones that

were open did not carry the ribbon. ‘It dawned on me’, he said in an interview

with CNN’s Stuart Varney, ‘that not only could small entrepreneurs not get sta-

tionery at the rate of bigger companies, sometimes they couldn’t get it at all.’ He

still had no ribbon to finish his business plan over the weekend, but he had found

the new venture he actually wanted to start in that contingency.

Honda’s discovery of a market for small motorcycles in the USA has also been

cited in the literature as an example of serendipity (Denrell et al. 2003; Van Andei

1994). In the late 1950s Honda sought to introduce large motorcycles into the US

market in competition with Harley Davidson and European importers. Its strategy

was based on its analysis of the US market, where big bikes were very popular.

However, members of Honda’s import staff used small 50cc bikes for their own

transport needs. According to Kihachiro Kawashima, Honda’s US president:

‘We used the 50s ourselves to ride around Los Angeles. They attracted a lot of attention.

One day we had a call from a Sears buyer … surprisingly, the retailers who wanted to sell

them weren’t motorcycle dealers, they were sporting goods stores.’ (Pascale 1984: 55)

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

738 Organization Studies 30(07)

Thus Honda serendipitously discovered a latent market for small motorcycles in the

USA, in a classic example of searching for one opportunity and discovering another

through a contingent interaction — in this case, with a Sears buyer — what

Mintzberg (1996) has described as being ‘pleasantly surprised’ by a contingency.

Serendipity also sometimes occurs in the discovery of new combinations of fac-

tors of production (Schumpeter 1934). An example of this can be found in the his-

tory of J. R. Simplot, the potato magnate. Simplot built a business storing and sorting

potatoes and onions during the Great Depression. Silver (1985) recounts that:

‘in the spring of 1940, Jack Simplot decided to drive to Berkeley, California, to find out why

an onion exporter there had run up a bill of $8,400 for cull (or reject) onions without pay-

ing. … The girl in the office said the boss wasn’t in. Fine, said J. R., he would wait until the

man arrived.

‘Two hours later, at ten o’clock, a bearded old man walked in. Assuming this was his

debtor, Simplot accosted him. But he turned out to be a man named Sokol, inquiring why

he was not getting his due deliveries of onion flakes and powder. They sat together until

noon, but still the exporter failed to arrive.

‘As the noon hour passed, Simplot was suddenly struck with an idea. He asked the

bewhiskered old trader to a fateful lunch at the Berkeley Hotel. “You want onion pow-

der and flakes,” said J. R., “I’ve got onions. I’ll dry ‘em and make powder and flakes

in Idaho.”’

Thus, through a contingent meeting with Sokol, Simplot found an opportunity to

recombine his existing resources (storage and sorting facilities and access to a

large supply of onions) with new ones (onion-drying processes). This recombina-

tion was important because drying onions (and later potatoes and other foods)

increased the capital efficiency of Simplot’s traditional operations by reducing the

warehouse space required for storage by a factor of seven. Simplot thus discovered

synergies with his existing operations, an example of the serendipitous discovery

of strategic interactions between resources, described by Denrell et al. (2003).

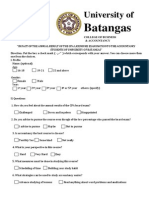

Table 1.

Examples of Domains and overlaps Examples

Domains and

Overlaps in Figure 1 Contingency/accident J. R. Simplot’s chance meeting with Sokol (Silver 1985);

Peter Hodgson’s chance attendance of a party where kids

happened to be playing with Silly Putty as a toy (Van Andei 1994).

Prior knowledge Knowledge of technologies, markets, and customer needs learned

from working with users in their prior jobs. Bhidé (1996) found

that over 50% of HBS entrepreneurs he sampled started their firms

based on specific insights gained in prior employment.

Search activity Thomas Edison searched 6000 vegetable growths and ‘ransacked

the world’ for a suitable filament for his most important innovation:

the electric light bulb (Weitzman 1998).

Systematic exploration An entrepreneur’s periodic scrutiny of their storehouse of previously

shelved venture ideas; for firms, periodic scrutiny of previously

shelved technologies, patents, etc. (Wilson and Hlavacek 1984).

Spontaneous recognition Opportunities for commercializing. MIT’s 3DP technology was

spontaneously recognized by eight different entrepreneurs

(Shane 2000).

Pre-discovery Corning’s pre-discovery of technology for optical fibers

(Cattani 2006).

Serendipity Thomas Stemberg’s founding of Staples office supply retail chain

(Sarasvathy 2007).

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

Dew: Serendipity in Entrepreneurship 739

Figure 1. Serendipitous Discovery

Domains of – Search activity leading to the discovery

Opportunity Discovery of something the entrepreneur was not

looking for

Domain of Pre-discovery

Systematic Search – Hunch that something has

been discovered but lack of

Exploration pre-existing knowledge to

– Discovery of opportunities make an on-the-spot

is based on purposefully evaluation

searching knowledge

corridors

Domain of

Domain of

Prior

Contingency

Knowledge

Spontaneous

Recognition

– Sheer/utter surprise

Since serendipity is a somewhat elusive concept, I will examine a framework that

helps to tangibly locate it in relation to prior research in the entrepreneurship literature

on opportunity identification, discovery, and creation (Shane and Venkataraman

2000). The focus is on three conceptual building blocks that have been extensively

explored in the literature. In essence, serendipity involves the interaction of three ele-

ments: a resource (sagacity), an event (contingencies), and an activity (the individual

is already on a journey). Figure 1 uses a framework that captures these three elements

as three domains and relates them to different types of opportunity discovery.2 Table 1

illustrates this framework with examples from a variety of entrepreneurial endeavors.

The three domains in Figure 1 can be described as follows. First, within the entre-

preneurship literature the concept of prior knowledge captures the notion of

sagacity, i.e. the prepared mind. Prior knowledge is a stock of information known

to a particular individual. Because information is generated through idiosyncratic

life experiences, the stock of prior knowledge held by individuals differs consider-

ably (Venkataraman 1997). Empirical research has shown that prior knowledge is

influential in the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities (Shane 2000).

The second domain is that of contingencies. Contingencies can be defined as

events that are not logically necessary, i.e. could not have occurred. They may

happen by pure chance, or without a known cause. In the model presented in

Figure 1, contingencies represent the influence of the exogenous environment on the

discovery of possible opportunities. Anecdotal evidence suggests contingent events

abound in entrepreneurship, and several papers in the literature ascribe an impor-

tant role to contingencies (Mintzberg and Waters 1982; Sarasvathy 2001).

The third domain is search. Search activity involves purposeful actions under-

taken to acquire new information. Because search is costly, it has been theorized

that differences in search costs may explain the propensity of some individuals

to become entrepreneurs rather than others (Stigler 1961). Prior research

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

740 Organization Studies 30(07)

has suggested that heterogeneous search capabilities may be one kind of

individual-specific entrepreneurial resource (Alverez and Busenitz 2001).

Importantly, search activity may occur with or without invoking prior knowledge.

Because individuals forget things, they may even sometimes search for the same

things more than once (De Holan and Phillips 2004). Some possible examples of

search without prior knowledge include random search processes (Hayes 2001),

habitual search activity (Hodgson 2006), and playful search (March 1982).

The overlapping areas of the three domains of search, prior knowledge, and

contingency results in four fictional opportunity discovery ‘spaces’ in Figure 1:

a space where opportunities are discovered as the result of the systematic explo-

ration of knowledge corridors; a space where opportunities are discovered as a

result of spontaneous recognition; a space where search and contingency result

in pre-discoveries; and finally, a space where serendipities occur. The next sec-

tions of the paper describe each of these in turn.

Systematic Exploration

Several authors have suggested that the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities

might be the result of purposeful search activity (Caplan 1999; Fiet 1996, 2002).

This search may involve looking for demand-side opportunities arising from

unserved or underserved market needs, or it may involve looking for supply-side

opportunities arising from the possibility of serving market needs with new

resource combinations. The former is sometimes conceptualized as search of an

exogenously given opportunity set, whereas the latter may be conceptualized as an

endogenous process (Weitzman 1998: 332).

In either case, two characteristics of the notional search space are important.

First, the number of possibilities that have to be searched is vast, which means

searching for opportunities is costly. Therefore the effectiveness of search

depends on entrepreneurs making cost-effective informational investments that

equilibrate the costs of search with the benefits it may potentially produce (Fiet

1996; Stigler 1961). Second, public areas of the search space are unlikely to be

especially fruitful because other entrepreneurs are likely to have already searched

there and thus picked all of the ‘low-hanging fruit’. Therefore the entrepreneur

may be better off searching areas where information asymmetries exist, i.e. where

it is possible that the entrepreneur may gain a competitive advantage because of

private information (Hayek 1945). This suggests that the entrepreneur should

constrain their search to a ‘consideration set’ that initially consists of their prior

knowledge resources (Fiet 2002). This overlap between the domain of search and

the domain of prior knowledge is captured in Figure 1 as the space where oppor-

tunity discovery is the result of systematic exploration of knowledge corridors.

The effectiveness of systematic exploration is a function of relative search costs

and the nature of prior knowledge. Heterogeneous search costs may explain why

some people discover opportunities while others do not. One explanation of

different costs is that individuals mostly search myopically, which suggests that

opportunity discovery is situational, because individuals are more likely to dis-

cover opportunities that are ‘cheap’ to find because they happen to be nearby, i.e.

close to their pre-existing knowledge. An alternative explanation is that entrepre-

neurs have better search processes than non-entrepreneurs, either because they

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

Dew: Serendipity in Entrepreneurship 741

scan information better or have superior information-processing abilities, maybe

as a result of acquired expertise (Shaver and Scott 1991). Alverez and Busenitz

(2001:755) build on this explanation by suggesting that the prior knowledge and

cognitive ability of entrepreneurs may be conceptualized as a heterogeneous

resource, arguing that entrepreneurs ‘have individual-specific resources that

facilitate the recognition of new opportunities and the assembling of resources’.

They argue that these resources give entrepreneurs a relative advantage (over

non-entrepreneurs) in systematically exploring for opportunities.

Spontaneous Recognition

An alternative and complementary category of entrepreneurial opportunities are

those that involve spontaneous recognition. Obvious opportunities can be searched

for, but entrepreneurs cannot search for information that they do not know exists

(Kirzner 1997). In these cases, individuals are (initially) utterly ignorant of the exis-

tence of the possible opportunity. However, they may recognize an opportunity if

they happen to come across it contingently. Thus, some opportunities may be dis-

covered in the absence of any search activity. Figure 1 captures this space of oppor-

tunities as the space where the domains of contingency and prior knowledge overlap.

A good example that fits into this space is Shane’s study of eight entrepreneurs

who sought to commercialize a new technology, called 3DP, that was developed at

MIT (Shane 2000:451). Shane points out that the discovery of opportunity was

based on the contingent arrival of new information: ‘People do not discover oppor-

tunities through search, but through recognition of the value of new information that

they happen to receive through other means.’ In the case of Shane’s study, all eight

entrepreneurs he studied heard about 3DP technology from someone directly

involved in its development. None of the entrepreneurs had contacted MIT’s

Technology Licensing Office about the technology. Therefore, in these cases the dis-

covery of opportunity occurred because of a combination of two elements captured

in Figure 1. First, new information arrived contingently, i.e. the entrepreneurs were

all introduced to 3DP technology by social network contacts. Second, they com-

bined this new information with their prior knowledge of a possible use or applica-

tion of the technology. The result of this matching process was the discovery of a

possible opportunity. According to Shane, none of the eight entrepreneurs said they

found the commercial opportunity by searching for it. Instead, they each discovered

different opportunities to apply the new technology based on their prior knowledge.

The results of Shane’s study are very much in line with arguments made in the

literature about knowledge ‘corridors’ (Ronstadt 1988; Venkataraman 1997). Prior

knowledge captures the idea of a stock of knowledge, and the knowledge corridor

metaphor adds the hypothesis that this accumulation process typically occurs

along a narrow, probably path-dependent trajectory. Studies of habitual entrepre-

neurs have added the insight that much of the specific knowledge accumulated

by entrepreneurs occurs in the course of their prior entrepreneurial experiences

(Ucbasaran et al. 2008). Prior experience therefore generates specific knowledge

that is used in recognizing future opportunities, and thus may potentially fuel

future episodes of entrepreneurship in an individual’s career. Very experienced

entrepreneurs may be adept at recognizing several different opportunities in a

given invention such as the one described by Shane (Gaglio and Katz 2001).

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

742 Organization Studies 30(07)

Pre-discovery

Figure 1 also reveals one space of opportunity discovery that has been less

studied in the literature. This is the space where contingency and search overlap,

but without prior knowledge (sagacity). In this space, unanticipated opportuni-

ties are ‘pre-discovered’, i.e. an entrepreneur may suspect that they have dis-

covered an opportunity but they lack the pre-existing knowledge that is needed

in order to immediately recognize what has been discovered. For example, peni-

cillin had been ‘pre-discovered’ by many bacteriologists who had observed the

growth of one bacterium inhibiting the growth of another. However, these indi-

viduals lacked the prior knowledge that was needed in order to make an on-the-

spot evaluation of what they had found (Merton and Barber 2004: 176).

In the literature on technology evolution, recent empirical research by Cattani

(2006) highlights that pre-discoveries are quite commonplace. Cattani uses the

term ‘pre-adaptation’ to describe some technology discoveries firms make: ‘that

part of a firm’s technological knowledge base that is accumulated without antic-

ipation of subsequent uses (foresight), but might later prove to be functionally

“pre-adapted” (i.e., valuable) for alternative, as yet unknown, applications’

(Cattani 2006: 286). One firm Cattani studied was Corning, where the technolo-

gies for optical fibers and flat-panel display glass were both pre-discovered

years before the complementary knowledge necessary to commercialize them

was developed. As emphasized by Garud and Nayyar (1994) in their framework,

such discoveries may be systematically explored for their knowledge character-

istics, and relevant knowledge about them may be stored for potential reactiva-

tion, synthesis, and use in the future.3

Serendipity

While systematic exploration, spontaneous recognition, and pre-discovery

highlight different combinations of search, prior knowledge, and contingency,

serendipity captures all three in a single combinational concept (see Figure 1).

Serendipity is distinct from exploration and recognition (two ideas debated vig-

orously in the literature — Alsos and Kaikkonen 2004; Gaglio & Katz 2001), yet

builds on elements common to both these concepts. It differs from systematic

exploration because it incorporates a significant role for contingent environmen-

tal factors in the discovery of opportunities. It differs from spontaneous recogni-

tion because it supposes that opportunity discovery involves a vigorous quest on

the part of the entrepreneur, rather than the discovery of opportunities that were

all along under the entrepreneur’s nose (Kirzner 1997: 72). It differs from pre-

discovery in that it incorporates a role for prior knowledge in the opportunity

discovery process.

This combinational conception of serendipity is also useful in distinguishing

serendipity from luck (Barney 1997; Demsetz 1983; Friedel 2001; Ma 2002).

Luck is captured in the domain of contingency (Figure 1). As described by

Denrell et al. (2003: 989):

‘While good luck may befall the inert or lazy, serendipitous discovery occurs only in the

course of an energetic quest — a quest in which lucky discoveries of an unanticipated

kind can be recognized through alertness and then flexibly exploited.’

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

Dew: Serendipity in Entrepreneurship 743

For the purposes of this paper, I shall define pure luck as some kind of favorable

contingency or chance happening (i.e. an event completely beyond the entrepre-

neur’s control) that impacts the entrepreneur in a positive way. Luck is some-

thing that (sometimes) happens to you. It does not presuppose any search

activity or prior knowledge on the part of the entrepreneur. Also, by contrast with

luck, the role of contingencies in serendipity can come in more or less fortunate

forms, such that unlucky incidents may sometimes constitute the contingent

component of serendipity.

Having thus defined a framework in which serendipity can be understood as

an inclusive element of entrepreneurial opportunity, it may help to place this

framework in a broader context in which entrepreneurial discovery and creation

occur. To do this, I next turn to examining serendipity in an evolutionary and

institution-rich context. What emerges from this analysis is the sense that

serendipity occupies an important place in some widely used and powerful ideas

about social and economic dynamics.

Links between Serendipity and Evolutionary Theory,

Socio-economic Institutions and Social Psychology

The Evolutionary Logic of Serendipity

Human systems are complex and evolving, creatively open-ended, and subject to

several types of nonlinear behavior (Buchanan and Vanberg, 1990; Prigogine and

Stengers 1984). Dooley and Van de Ven (1999) highlight four patterns in such

dynamics (periodic, chaotic, white noise, or pink noise) which suggest different

underlying generative mechanisms. Their analysis points to differences in the

causes of complex behavior in evolving systems, and the necessity of using dif-

ferent process theories to understand and explain them. For some types of sys-

tems, seemingly innocuous and improbable serendipities may have far-reaching

consequences because the system sometimes amplifies small events into large

effects (Taleb 2007). That things could have turned out very differently in the face

of equally plausible serendipities, or without the surprises of serendipity, is a fact

that we will inevitably have to admit. In other types of systems, the vast majority

of serendipities may merely be ‘lost’ events that, in effect, are swallowed up by

other processes, eventually becoming errors of omission — just one more micro-

scopic element in the cloudy, confusing human comedy. These are the serendipi-

ties that went sufficiently unattended to in the flow of human experience that they

had no meaningful impact on the shape of future social artifacts (Garud and

Karnoe 2001). Indeed, because all human descriptions of events depend on social

processes that shape patterns of noticing and inattentiveness (Weick 1979), it is

also possible that the fraction of serendipities that we (collectively) pay attention

to are merely those few mindfully noted events that have been selected — perhaps

retrospectively — for their meaningfulness. This is to say, that the concept of

serendipity may sometimes be a useful tool for helping us generate good entre-

preneurial stories out of vaguely understood, highly complex situations.

Yet, serendipity is not just a product of our mental limitations, which mask

underlying processes that are deterministic in nature. Consistent with complex

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

744 Organization Studies 30(07)

systems thinking, it involves contingent interactions that have real ontological

status in the world and are not just a matter of our inability to know the deeper

structures that determine outcomes (Gould 2002). The kind of contingent, acci-

dental, fortuitous features of history we commonly claim under the title ‘serendip-

itous’ are an irreducible and real property of evolutionary processes (Kantorovich

and Neeman 1989). In principle, there is unpredictability in these processes. This

does not necessarily mean that serendipity creates chaos in organizational histo-

ries. As noted by Dooley and Van de Ven (1999: 367), the common meaning of

chaos is extreme disorder and confusion but from a mathematical point of view the

opposite is true, and a large part of the work of chaos theorists has involved creat-

ing simple mathematical relationships that effectively model chaotic patterns

(Mandelbrot and Hudson, 2006). Thus viewed, the ‘accidental’ event may be

explained by prior interactions, and might perhaps be a recurring result of them,

though any particular instance remains unpredictable.4 Stephan Jay Gould, who

made a career in evolutionary biology as a champion of contingency, quotes Darwin

himself, saying, ‘I believe in no fixed law of development … variability … depends

on many complex contingencies’ (Gould 2002: 1335). According to Gould:

‘Over and over again, through the Origin [of Species], Darwin stresses that, for a large

class of problems about species and interacting groups, answers must be sought in the

particular and contingent prior histories of individual lineages, and not in general laws of

nature that must affect all taxa in a coordinated and identical way.’ (Gould 2002: 1335)

Since evolutionary theorizing is used so frequently in conceptualizing entrepre-

neurship, organizations, markets, and institutions, the same argumentation can

be applied to them. This means that the histories of our organizations, markets,

institutions, and other products of serendipitous entrepreneurship will tend to

have a contingent nature. One result is that any view of economic and social evo-

lution that gives a real place to serendipity implies that we cannot validate our

present institutions, markets, and organizations by general principles but only as

an outcome of contingent, historical processes (Rorty 1989). A careful appreci-

ation of the role of serendipity therefore attenuates some of our accepted notions

of how social and economic processes work, and has implications for how they

might best be designed to work. A striking example of this occurs in thinking on

socio-economic institutions, to which I turn next.

Socio-economic Institutions and Serendipitous Entrepreneurship

Few institutional thinkers have shown such a clear appreciation of the role of

serendipity and entrepreneurship as Hayek (1960). Hayek didn’t use the term

‘serendipity’ but he was clearly thinking about something very similar in the

following passage:

‘Humiliating to human pride as the insight may be, we must recognize that we owe the

advance and even the preservation of civilization to a maximum of opportunity for acci-

dents to happen.’ (Hayek, 1960: 29)

The implication is that serendipitous entrepreneurship belongs with a clutch of

ideas (i.e. unintended consequences and spontaneous orders) with a common

root in the limits to human knowledge (Hayek 1974). Hayek makes a powerful

argument for individual freedom based on this:

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

Dew: Serendipity in Entrepreneurship 745

‘If there were omniscient men, if we could know not only all that affects the achievement

of our present wishes but also our future wants and desires, there would be little case for

liberty … Liberty is essential to leave room for the unforeseeable and unpredictable; we

want it because we have learned to expect from it the opportunity of realizing many of

our aims.’ (Hayek 1960: 29)

Important implications follow from this argument for the design (whether delib-

erate or evolutionary) of institutional frameworks that best leverage serendipities.

First, individual entrepreneurs must allow enough freedom in their own plans that

they might leverage serendipities. Relentless predefinition of entrepreneurial

ventures, either in the form of business planning or ‘vision’, restricts the entre-

preneur’s opportunity to harness serendipity (contra Witt 2007). Next, the institu-

tional constraints imposed by organizations on employees also need careful

examination so that employees are allowed sufficient autonomy to pursue

serendipitously discovered opportunities (Tsoukas 1996). In this regard, Hayek’s

arguments for freedom are just as relevant to private institutions as they are for

public ones (see, for example, Schlender 1992 on Sony’s practices). Furthermore,

institutions vary in how well they encourage the retention of knowledge that

might fund future serendipitous events. As noted by Garud et al. (1997: 348):

‘Institutions are not mechanisms to sanction individuals for “failed” efforts, but

are devices for the retention of knowledge from “experiments”.’ Institutions that

support the retention of prior knowledge help access (future, possible) serendipi-

ties. Thus, organizations that value serendipity are motivated to take a different

approach to ‘failure’ and ‘waste’, one that recognizes the option value inherent in

establishing a stock of prior knowledge, even when that is a product of creative

endeavors that ostensibly went ‘wrong’ (Garud et al. 1997).

Social Psychology of Serendipity in Entrepreneurship

Serendipity has an important role in the public image of entrepreneurship.

Indeed, it may not be going too far to say that in popular perception these two

concepts are tightly linked. The central issue is that, on the one hand, there is a

popular image of the entrepreneur (particularly strong in the USA) which cele-

brates the idea that people with merit win out in the entrepreneurial process. Yet,

on the other hand, there also appears to be an underlying popular hostility

towards the idea that merit alone won the day. People prefer the idea that ‘lady

luck’ also has an important role in the entrepreneurial process (regardless of the

scientific accuracy of this preference). From this, we can discern that the popu-

lar image of successful entrepreneurship implicitly identifies an important role

for serendipity in entrepreneurship, i.e. the social psychology of entrepreneur-

ship involves lucky accidents as well as individual effort and sagacity.

This issue — that public perceptions of classes of individuals sometimes

revolve around the concept of serendipity — prompted a fascinating discussion by

Merton with regard to scientists (Merton and Barber 2004: 169). What Merton

noticed was that, for reasons perhaps of threat, envy, or fairness, the public likes to

attribute advances in science to ‘the happy accident’, precisely because it tends to

pull the scientist off his/her pedestal and bring him/her back down to earth, thus

making the work of great scientists more congenial with both the average individ-

ual’s abilities and experiences of everyday life (in which serendipity plays a part).

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

746 Organization Studies 30(07)

Serendipity — which might be thought of as a fancy word for ‘chance and smart

fellows’ (Merton and Barber 2004: 169) — thus has popular appeal precisely

because it is an equalizing factor that enables people to vicariously imagine them-

selves as the scientist, or entrepreneur, who discovers or creates the next big thing.

This social psychology might be traced to notions of fairness (Rawls 1971),

i.e. that whereas the lottery of birth may have treated people unfairly by gifting

them with unequal skills and motivations, contingency rebalances the scales

somewhat, precisely because of the synergistic interaction required between

contingency, sagacity, and effort that is required to yield serendipity. Accident

may be no use without effort and sagacity, but effort and sagacity are of little

value without being complemented by fortunate accidents which can be lever-

aged — and these may be randomly distributed. The attractiveness of this image

to the public psyche — that even the gifted need their lucky accidents — brings

to mind the image of Greek gods rolling dice to determine human destinies.

Thus, the popular appeal of entrepreneurship may be said to stretch just as far as

the concept of serendipity stretches: the public likes its entrepreneurial heroes

(popular figures like Bill Gates) to be worthy of their wealth by being meritori-

ous; but only insofar as they were also recipients of good fortune. This combi-

nation centers popular perceptions of entrepreneurship squarely on the concept

of serendipity, which serves to keep entrepreneurship both imaginatively acces-

sible and enables its outcomes to be perceived as ‘fair’ in the popular psyche.

Implications for Research and Practice

Research Implications

In a recent comment directed at the marketing community, Brown (2005) sum-

marized developments in what he called ‘the science of serendipity’ and urged

marketing scholars to pay more attention to the ‘incorrigible incalculability of

commercial life’, arguing that, ‘the history of management in general and mar-

keting in particular reveals that serendipity plays a significant part in the com-

mercial equation’ (Brown 2005). In this section of the paper, I suggest that

the framework developed in this paper carries two significant implications for

research in entrepreneurship that scholars might consider devoting more attention

to understanding.

The first implication that the concept of serendipity highlights is that the dis-

covery of some opportunities involves a genuine and non-trivial role for contin-

gency as a trigger event. Consider the role of the taller tree in the discovery of

trickle irrigation, the melting candy bar in the invention of microwave cooking,

or the set of circumstances that led Simplot to make the acquaintance of Sokol.

The importance of contingency in combination with other factors is easily under-

estimated (Gould 2002; Rorty 1989; Taleb 2002). Thus, of the three elements that

constitute serendipity, it is contingency that has the most profound implications

for how researchers think about entrepreneurial opportunity. The central issue is

that our models of entrepreneurial phenomena typically involve treating contin-

gencies as error terms that are essentially expunged from the analysis, controlled

for, or assumed away. But what if the error term is the regularity? The concept of

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

Dew: Serendipity in Entrepreneurship 747

serendipity suggests that it is the chance conversation, the idiosyncratic outlier,

the unanticipated event, or the anomalous result that fund opportunity discovery

and creation. If we relegate these terms to the category of errors, it leads to a sys-

tematic underestimation of a phenomenon that may be important to our under-

standing of opportunity discovery and creation.

Of course, if we acknowledge an important role for contingency, we are left

with several difficult questions about drawing valid lessons based on scientific

principles that implicitly or explicitly apply deterministic frameworks. As

Denrell (2004) puts it:

‘Underestimation of the role of chance also makes it difficult for individuals to draw valid

lessons from history … there is always something special in the history of a firm, its strat-

egy, and its organization that could be used to explain its performance record. Thus, even

if success is the result of luck, it is possible to construct an “explanation” (Fischhoff 1975,

1982). The explanation may be entirely spurious, however.’ (Denrell 2004: 933)

Brown (2005) argues that this has been the case in marketing, where everyone is

familiar with serendipities in the history of Velcro, Corn Flakes, Band Aids, and

Post-it-Notes, but there remains a systematic and misleading underestimation of

the total impact of contingency (Pina E Cunha 2004). Marketing scholars have

used extremely sophisticated statistical analyses, ‘But for all this probabilistic

prowess, our concepts hardly capture the sheer capriciousness of commercial

life’ (Brown 2005: 1231). Dooley and Van de Ven further argue that, in organi-

zation studies, the value placed on generalizability of research findings is based

on ‘the assumption that knowledge about commonalities … are of more interest,

or value, than knowledge about differences … Aren’t practicing managers as

interested in what they cannot generalize, as well as what they can?’ (Dooley and

Van de Ven 1999: 370). The same arguments could be made for entrepreneurship

research. And so what remains to be done is to incorporate a systematic role for

contingency the way the literati, historians and biologists have married chance

and necessity in their disciplines. In entrepreneurship, we have to find the right

balance between attending to, and ignoring, contingencies. Serendipity might be

fashioned into a useful concept for exactly this purpose.

The notion that some serendipities become venues for action, and some not, raises

a second implication: when are serendipities more likely to occur and be acted upon

(or not)? As suggested by McMullen and Shepherd (2006: 132), entrepreneurship

involves acting on ‘the possibility that one has identified an opportunity worth pur-

suing’. In the framework presented in this paper, I have made no particular assump-

tions about the ‘hit rate’ of serendipities, i.e. the framework is agnostic about what

entrepreneurs do with their serendipitously discovered opportunities. However,

whether serendipities are acted upon might be important for them to be considered

serendipitous by others.5 Also, it does seem that some entrepreneurs may be more

exposed to serendipity and more likely to develop and create new businesses based

on a serendipitously discovered opportunity (Ardichvili et al. 2003). These points

beg questions about the process of generating and acting on serendipity.

While there are several frameworks one could use to examine this issue, one

attractive framework is effectuation, because it suggests that a predisposition to

flexibly exploit contingency is a central element in the behavior of expert entre-

preneurs (Sarasvathy 2001). According to Sarasvathy (2007: 87):

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

748 Organization Studies 30(07)

‘Surprises are usually relegated to error terms in formal models. Instead an effectual logic

suggests they may be the source of opportunities for value creation, but only if someone

seizes upon them in an instrumental fashion and imaginatively combines them with

extant inputs to create new possibilities.’

In places, subjects in her experimental studies of expert entrepreneurs pointed

directly to the role of serendipity in their reasoning processes, suggesting

‘acknowledging and appropriating contingency rather than trying to avoid it’

was an important part of their cognitive processes (Sarasvathy 2007). Moreover,

effectual logic specifies that expert entrepreneurs take a particular approach to

leveraging serendipities, one in which the entrepreneur actively attempts to cre-

ate a context that attributes value to the conjectured opportunity in what Garud

et al. (1997) termed ‘tailoring fits’, i.e. engaging in the design and development

of market and institutional infrastructures (Sarasvathy et al. 2008; Garud et al.

2007). Of course, these actions highlight that the notion of discovery is some-

what different in the entrepreneurial realm than the scientific realm. In the sci-

entific realm, discovery is (at least by standard accounts) about finding new

phenomena and explaining them; in contrast, entrepreneurial discoveries involve

shaping and creating value in social settings, which involves action repertoires

such as interfering, orchestrating, tailoring, and so on.

What makes more experienced and expert entrepreneurs predisposed to har-

ness serendipity? One possibility is that there is a non-trivial linkage between

social network position and contingent events that roughly corresponds with

boundary-spanning, gate-keeping, and brokering activities (Burt 1992; Obstfeld

2005). To the extent that more experienced entrepreneurs tend to have richer

social networks, their network connections may expose them to information

flows that make them more likely to encounter contingencies. This suggests that

entrepreneurs may be able to engage in social networking behaviors that make it

more likely that contingencies (hence serendipities) happen to them, i.e. they may

deliberately engage in behaviors that semi-endogenize contingency. Sony’s ‘wan-

dering chairman’ serendipitously discovering a speaker system for the Walkman

exemplifies how certain networking activities may make contingencies more

likely (Garud et al. 1997). A second possibility is that the occurrence of serendip-

ity may vary with entrepreneurial experience because serendipity is a function of

prior knowledge, and more experienced entrepreneurs have larger pools of prior

knowledge and better ability to access and filter it (Baron and Ensley 2006).

Third, personality traits may play a role in receptiveness to serendipity and there-

fore the likelihood of leveraging it. Studies of entrepreneur psychology have

found that, in general, entrepreneurs score higher on the variable ‘openness to

experience’ than managers (Zhao and Seibert 2006). Openness to experience is

defined as someone who is intellectually curious and tends to seek new experi-

ences. Such individuals may be more receptive to, and welcoming of, contingent

events and information, and thus more likely to view these events as opportuni-

ties for action. These are individuals who display a taste for the unexpected, for

surprise (March 1982; Scitovsky 1976). The literature on expert cognition further

suggests that, because experts routinize many cognitive tasks, they are more

likely to have spare cognitive capacity available to handle non-routine tasks,

which may also increase their receptivity to contingencies (Feltovich et al. 2006).

Together these three factors suggest that future researchers might gain further

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

Dew: Serendipity in Entrepreneurship 749

insight into entrepreneurial opportunity by examining to what extent experience

and expertise make entrepreneurs more likely to encounter and exploit serendip-

ities on their travels.

Implications for Practice

This study also has implications for several aspects of practitioner behavior.

Many of these implications are not new, but worth reiterating nonetheless. A few

of them are significantly different from existing literature, and worth considera-

tion. First, entrepreneurs might wonder whether they should follow recommen-

dations from the research on systematic exploration (Fiet 2002) or from research

on spontaneous recognition (Shane 2000). The former suggests that entrepre-

neurs should make carefully considered, cost-effective investments in informa-

tion that signals the value of opportunities (Fiet 2002: 3). By contrast, the latter

suggests that ‘people do not discover entrepreneurial opportunities through

search’ and that they can and will discover entrepreneurial opportunities without

actively searching for them (Shane 2000: 451). What should an entrepreneur do?

Serendipitous discovery suggests that both factors, in fact, matter. This is

because an active search process may lead to the recognition of an opportunity,

even though the opportunity is not what the entrepreneur set out to look for. This

perspective allows practitioners to see that there may be a coherent rationale that

unifies these otherwise conflicting perspectives.

A second implication of this paper concerns a long-running debate between com-

mitment and flexibility. Remember that serendipitous discovery suggests that the

entrepreneurial process will involve exploiting accidents and surprises that happen

in the course of developing a venture. This raises the question of the optimal choice

of, and investment in, systems and processes to detect and exploit serendipities. In

a sense, the issue is how much commitment the entrepreneur should make to flex-

ibility (Ghemawat and Costa 1994). This is a conundrum that many academics and

practitioners have stubbed their toes on, so while a solution is clearly beyond the

scope of this paper, a few remarks might be helpful. One is that the entrepreneur

should expect business plans to change; in fact, evolving business plans may be

something to strive for. It is also advisable that, early in the life of a new enterprise,

the entrepreneur should use vision — if it is to be used at all — as a flexible

umbrella under which serendipities may be incorporated (if they occur). The

remarks by David Padwa in the introduction section of this paper stand as a

reminder of how unwise it may be to let deterministic vision constrain the devel-

opment of a new enterprise early in its life. Furthermore, even in very early-stage,

resource-scarce enterprises, entrepreneurs need to find ways of cutting themselves

enough slack to fund some continuing search activity. It has to be remembered that

serendipity is a tripod that relies on some kind of resource-consuming search, as

well as prior knowledge and contingency. Serendipity is not free.

Conclusion

Serendipity has been given little systematic attention by entrepreneurship schol-

ars (Boussouara and Deakins 1999), yet it appears that it might be very relevant

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

750 Organization Studies 30(07)

to the entrepreneurial process once its relationships with concepts already

employed in that literature are understood. To use an analogy, serendipity may

be just the difference between a forgotten ball or an immortal homerun, but

despite the fact that as a concept it exists on the knife edge of chance — and

therefore always appears to be in danger of dissolution — serendipity is a rich

idea that may be more central to the entrepreneurial process than so far has been

recognized. In serendipity is the delight of the strange moment. But this does not

make serendipity a residual, a leftover after the deterministic laws of the entre-

preneurial process have run their course. Instead, serendipitous events — though

by their nature individually unpredictable — may be worth understanding as a

central, recurring feature of entrepreneurship.

Notes The author would like to thank Raghu Garud and two anonymous Organization Studies reviewers

for their helpful remarks on earlier drafts of this paper. Thanks, as always, also go to my usual cast

of collaborators — you know who you are. The usual disclaimers apply.

1 Throughout the paper, I used the terms ‘accident’ and ‘contingency’ interchangeably.

2 Of course, whether the concept of ‘discovery’ is the most useful language for describing entre-

preneurial opportunity is a matter of debate in the field (McMullen and Shepherd 2006). In this

paper I take no particular position on this issue.

3 Throughout, I assume all opportunities are uncertain to some degree.

4 I would like to acknowledge the wisdom of an anonymous reviewer in pointing out the many dif-

ferent types of complex behaviors exhibited in evolving systems, and the possibility that a deeper

understanding of these different patterns of behavior may indicate that some cases of serendipity

are not, in fact, serendipitous, but may be predictable consequences of the behavior of the system.

5 I am grateful to Raghu Garud for pointing out this issue to me.

References Alsos, Gry A., and Virpi Kaikkonen Baron, Robert A., and Mica D. Ensley

2004 ‘Opportunity recognition and prior 2006 ‘Opportunity recognition as the

knowledge: A study of experienced detection of meaningful patterns:

entrepreneurs’. Paper presented at Evidence from comparisons of novice

the Nordic Conference in Small and experienced entrepreneurs’.

Business Research. Management Science 52/9: 1331–1344.

Alvarez, Sharon A., and Lowell W. Busenitz Bernard, Claude

2001 ‘The entrepreneurship of resource- 1865 An introduction to the study of

based theory.’ Journal of Management experimental medicine, trans.

27: 755–775. H. C. Green, 1957. New York: Dover.

Ardichvili, Alexander, Richard Cardozo, and Bhidé, Amir

Ray Sourav 1996 ‘The road well travelled: A note on

2003 ‘A theory of entrepreneurial the journeys of HBS entrepreneurs’.

opportunity identification and Harvard Business School publication.

development’. Journal of Business

Venturing 18/1: 105–123. Boussouara, Mohammed, and David Deakins

1999 ‘Market-based learning,

Barney, Jay B. entrepreneurship and the high

1997 ‘On flipping coins and making technology small firm’. International

technology choices: Luck as an Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour

explanation of technological foresight and Research 5/4: 204–223.

and oversight’ in Technological

innovation: Oversights and Brown, Steven

foresights. Raghu Garud, Praveen R. 2005 ‘Science, serendipity and the

Nayyar and Zur B. Shapira (eds). contemporary marketing condition’.

Cambridge: Cambridge University European Journal of Marketing

Press. 39/11–12: 1229–1234.

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

Dew: Serendipity in Entrepreneurship 751

Buchanan, James M., and Victor J. Vanberg Fiet, James O.

1990 ‘The market as a creative process’. 2002 The systematic search for

Economics and Philosophy entrepreneurial discoveries.

7: 167–186. Westport, CT: Quorum.

Burt, Ron Friedel, Robert

1992 Structural holes: The social structure 2001 ‘Serendipity is no accident’. The

of competition. Cambridge, Kenyon Review 23/2: 36–47.

MA: Harvard University Press.

Gaglio, Connie M., and Jerome A. Katz

Caplan, Brian 2001 ‘The psycological basis of

1999 ‘The Austrian search for realistic opportunity identification:

foundations’. Southern Economic Entrepreneurial alertness’. Journal

Journal 65/4: 823–838. of Small Business Economics

16: 95–111.

Cattani, Giovanni

2006 ‘Technological pre-adaptation, Garud, Raghu, and Peter Karnoe

speciation, and emergence of new 2001 ‘Path creation as a process of

technologies: How Corning invented mindful deviation’ in Path

and developed fiber optics’. Industrial dependence and creation. Raghu

and Corporate Change 15/2: 285–318. Garud and Peter Karnoe (eds), 1–38.

Philadelphia: Lawrence Earlbaum

De Holan, Pablo M., and Nelson Phillips Associates.

2004 ‘Remembrance of things past?

The dynamics of organizational Garud, Raghu, and Praveen Nayyar

forgetting’. Management Science 1994 ‘Transformative capacity: Continual

50/11: 1603–1613. structuring by inter-temporal

technology transfer’. Strategic

Demsetz, Harold Management Journal 15: 365–385.

1983 ‘The neglect of the entrepreneur’ in

Entrepreneurship. Joshua Ronen (ed.), Garud, Raghu, Cynthia Hardy, and Steve

271–280. Lanham, MD: Lexington Maguire

Books. 2007 ‘Institutional entrepreneurship as

embedded agency: An introduction to

Denrell, Jerker the Special Issue’. Organization

2004 ‘Random walks and sustained Studies 28/7: 957–969.

competitive advantage’. Management

Science 50/7: 922–934. Garud, Raghu, Praveen Nayyar, and

Zur Shapira

Denrell, Jerker, Christina Fang, and Sidney 1997 ‘Beating the odds: Towards a theory

G. Winter of technological innovation’ in

2003 ‘The economics of strategic Technological innovation:

opportunity’. Strategic Management Oversights and foresights. Raghu

Journal 24: 977–990. Garud, Praveen R. Nayyar and

Dooley, Kevin J., and Andrew van de Ven Zur B. Shapira (eds), 345–354.

1999 ‘Explaining complex organizational Cambridge: Cambridge

dynamics’. Organization Science University Press.

10/3: 358–372. Ghemawat, Pankaj, and J. E. Ricarti Costa

Feltovich, Paul J., Michael J. Prietula, and 1994 ‘The organizational tension between

K. Anders Ericsson static and dynamic efficiency’.

2006 ‘Studies of expertise from Strategic Management Journal

psychological perspectives’ in The 14/1–2: 59–75.

Cambridge handbook of expertise Gould, Steven J.

and expert performance. K. Anders 2002 The structure of evolutionary theory.

Ericsson, Neil Charness, Paul Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

J. Feltovich and Robert R. Hoffman

(eds), 41–68. Cambridge: Cambridge Hayek, Fredrich A.

University Press. 1945 ‘The use of knowledge in society’.

American Economic Review

Fiet, James O. 35/4: 519–530.

1996 ‘The informational basis of

entrepreneurial discovery’. Journal of Hayek, Fredrich A.

Small Business Economics 1960 The constitution of liberty. Chicago:

8/6: 419–430. University of Chicago.

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

752 Organization Studies 30(07)

Hayek, Fredrich A. innovation’. Administrative Science

1974 ‘The pretence of knowledge’. Quarterly 50: 100–130.

American Economic Review 79/6: 3–7.

Pascale, Robert T.

Hayes, Brian 1984 ‘Perspectives on strategy: The real story

2001 ‘Randomness as a resource’. behind Honda’s success’. California

American Scientist 89/4: 300–304. Management Review 26: 47–72.

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. Pina E Cunha, Miguel

2006 ‘The ubiquity of habits and rules’. 2004 ‘Serendipity: Why some organizations

Cambridge Journal of Economics are luckier than others’. Working

21/6: 663–684. Paper, University Of Lisbon.

Kantorovich, Aharon, and Yuval Neeman Prigogine, IIya, and Isabelle Stengers

1989 ‘Serendipity as a source of 1984 Order out of chaos — man’s new

evolutionary progress in science’. dialogue with nature. Toronto: Bantam.

Studies in History and Philosophy of Rawls, John

Science 20/4: 505–529. 1971 A theory of justice. New York: Belknap.

Kirzner, Israel Roberts, Royston M.

1997 ‘Entrepreneurial discovery and the 1989 Serendipity: Accidental discoveries in

competitive market process: An science. New York: Wiley.

Austrian approach’. Journal of

Economic Literature 35: 60–85. Ronstadt, Robert

1988 ‘The corridor principle’. Journal of

Ma, Hao Business Venturing 3/1: 31–40.

2002 ‘Competitive advantage: What’s luck

got to do with it?’ Management Rorty, Richard

Decision 40/6: 525–536. 1989 Contingency, irony, and solidarity.

Cambridge: Cambridge University

McMullen, Jeff S., and Dean A. Shepherd Press.

2006 ‘Entrepreneurial action and the role of

uncertainty in the theory of the Sarasvathy, Saras D.

entrepreneur’. Academy of 2001 ‘Causation and effectuation: Toward a

Management Review 31/1: 132–152. theoretical shift from economic

inevitability to entrepreneurial

Mandelbrot, Benoit, and Richard L. Hudson contingency’. Academy of

2006 The misbehavior of markets: A fractal Management Review 26/2: 243–263.

view of risk, ruin and reward.

Sarasvathy, Saras D.

New York: Basic Books.

2007 Effectuation: Elements of

March, James G. entrepreneurial expertise.

1982 ‘The technology of foolishness’ in Cheltenham: Routledge.

Ambiguity and choice in Sarasvathy, Sars D., Nicholas Dew, Stuart

organizations. James G. March and Read, and Robert Wiltbank

Johann P. Olsen, 69–81. Bergen: 2008 ‘Designing organizations that design

Universitetsforlaget. environments’. Organization Studies

Merton, Robert K., and Eleanor Barber 29/3: 331–350.

2004 The travels and adventures of Schlender, Brenton R.

serendipity: A study in sociological 1992 ‘How Sony keeps the magic going’.

semantics and the sociology of Fortune, 24 February 1992: 76–82.

science. Princeton: Princeton

University Press. Schumpeter, Joseph A.

1934 The theory of economic development.

Mintzberg, Henry Oxford: Oxford University Press.

1996 ‘Learning 1, planning 0’. California

Management Review 38/4: 92–93. Scitovsky, Tibor

1976 The joyless economy: An inquiry into

Mintzberg, Henry, and James A. Waters human satisfaction and consumer

1982 ‘Tracking strategy in an dissatisfaction. Oxford: Oxford

entrepreneurial firm’. Academy of University Press.

Management Journal 25/3: 465–499.

Shane, Scott

Obstfeld, David 2000 ‘Prior knowledge and the discovery

2005 ‘Social networks, the tertius iungens of entrepreneurial opportunities’.

orientation, and involvement in Organization Science 11/4: 448–469.

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

Dew: Serendipity in Entrepreneurship 753

Shane, Scott, and Sankaran Venkataraman University of Pennsylvania

2000 ‘The promise of entrepreneurship 2004 Papers with serendipit* in the title.

as a field of research’. Academy Online: downloaded 14 February

of Management Review 25/1: 2007. http://www.garfield.library.

217–226. upenn.edu/histcomp/serendipit_

title/index-3.html.

Shaver, Kelly G., and Linda R. Scott

1991 ‘Person, process, choice: The Van Andei, Pek

psychology of new venture creation’. 1994 ‘Anatomy of the unsought finding.

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice Serendipity: Origin, history, domains,

16/2: 23–42. traditions, appearances, patterns and

programmability’. British Journal of

Silver, David.A.

Philosophy of Science 45: 631–648.

1985 Entrepreneurial megabucks: The 100

greatest entrepreneurs of the last 25 Venkataraman, Sankaran

years. New York: Wiley. 1997 ‘The distinctive domain of

Stigler, George entrepreneurship research’ in Advances

1961 ‘The economics of information’. in entrepreneurship research: Firm

Journal of Political Economy emergence and growth. Jermoe A. Katz

69/3: 213–225. (ed.), 119–138. Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Taleb, Nassim N. Weick, Karl E.

2002 Fooled by randomness: The hidden 1979 The social psychology of organizing.

role of chance in life and in the Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

markets. New York: Texere.

Weitzman, Martin L.

Taleb, Nassim N. 1998 ‘Recombinant growth’. Quarterly

2007 The black swan. The impact of the Journal of Economics 113/2: 331–360.

highly improbable. New York:

Random House. Wilson, T. L., and J. D. Hlavacek

1984 ‘Don’t let good ideas sit on the shelf’.

Tsoukas, Haridimos Research Management 27/3: 27–34.

1996 ‘The firm as a distributed knowledge

system: A constructionist approach’. Witt, Ulrich

Strategic Management Journal 2007 ‘Firms as realizations of

17: 11–25. entrepreneurial visions’. Journal of

Management Studies 44/7:

Ucbasaran, Deniz, Paul Westhead, 1125–1140.

and Mike Wright

2008 ‘Opportunity identification and Zhao, Hao, and Scott E. Seibert

pursuit: Does an entrepreneur’s 2006 ‘The big five personality dimensions

human capital matter?’ Journal of and entrepreneurial status: A meta-

Small Business Economics 30/2: analytical review’. Journal of Applied

153–173. Psychology 91: 259–271.

Nicholas Dew Nick Dew is an Assistant Professor of Strategic Management at the Naval Postgraduate

School, Monterey. His research focuses on entrepreneurial cognition and industry evolu-

tion. He has a PhD in management from the University of Virginia and an MBA from the

Darden school. Before entering academia, he spent eight years working internationally in

the oil industry. His work has been published in several academic journals, including the

Journal of Marketing, Strategic Management Journal, the Journal of Business Venturing,

the Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies. He has received the Louis D.

Liskin award for teaching excellence at NPS.

Address: Graduate School of Business and Public Policy, Naval Postgraduate School,

Monterey, CA 93943, USA.

Email: ndew@nps.edu

Downloaded from oss.sagepub.com at TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY on December 18, 2014

You might also like

- Mario Bunge - Demarcating Science From Pseudoscience (1982)Document20 pagesMario Bunge - Demarcating Science From Pseudoscience (1982)Sergio MoralesNo ratings yet

- First Grade Community Unit OverviewDocument5 pagesFirst Grade Community Unit OverviewKristen Coughlan100% (5)

- Chapter 2 Entrepreneurial DNADocument38 pagesChapter 2 Entrepreneurial DNACelina LimNo ratings yet

- Creating Video Lessons: Basis For Teachers Training: ProponentsDocument3 pagesCreating Video Lessons: Basis For Teachers Training: ProponentsJemuel AntazoNo ratings yet

- 2 Passages's (3rd)Document9 pages2 Passages's (3rd)AyushNo ratings yet

- Accidental ScientistsDocument9 pagesAccidental ScientistsThủy Dương100% (3)

- Final Creativity S.kazim (2015-El-046)Document11 pagesFinal Creativity S.kazim (2015-El-046)kdon160% (1)

- What Is CreativityDocument11 pagesWhat Is Creativitykdon16No ratings yet

- To Most People-WPS OfficeDocument4 pagesTo Most People-WPS Officenck slimNo ratings yet

- Chase Chance and Creativity The Lucky A - James H AustinDocument367 pagesChase Chance and Creativity The Lucky A - James H AustinkvngtamzNo ratings yet

- Serendipity - WikipediaDocument5 pagesSerendipity - WikipediaFabio OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Creativity in ScienceDocument14 pagesCreativity in ScienceDrWhoFNo ratings yet

- Passage 3 08.02 @mindless - WriterDocument6 pagesPassage 3 08.02 @mindless - Writersdth9911No ratings yet

- Reading Writing SpeakingDocument7 pagesReading Writing Speakinglong phamNo ratings yet

- Homo Problematis Solvendis–Problem-solving Man: A History of Human CreativityFrom EverandHomo Problematis Solvendis–Problem-solving Man: A History of Human CreativityNo ratings yet

- Maley in Tomlinson (2003) - Creative Approaches To Writing MaterialsDocument16 pagesMaley in Tomlinson (2003) - Creative Approaches To Writing MaterialsCindyUbietaNo ratings yet

- Capability, Namely To Recombine Any Number of Observations and Deduce Matching Pairs'Document7 pagesCapability, Namely To Recombine Any Number of Observations and Deduce Matching Pairs'Leon LaupNo ratings yet

- Reading Exercise (Stole)Document20 pagesReading Exercise (Stole)William MarcusNo ratings yet

- Reading FullDocument12 pagesReading FullVy PhạmNo ratings yet

- Between Zero and One: On The Unknown Knowns: Professor Simon Biggs, Edinburgh College of Art, September 2010Document8 pagesBetween Zero and One: On The Unknown Knowns: Professor Simon Biggs, Edinburgh College of Art, September 2010bairagiNo ratings yet

- How Managers Express Their CreativityDocument9 pagesHow Managers Express Their CreativityElyes ElyesNo ratings yet

- Reading Excercises (Advanced)Document70 pagesReading Excercises (Advanced)Kim GiaNo ratings yet

- EmbracingDocument2 pagesEmbracingasdfjiilNo ratings yet

- Inventology: How We Dream Up Things That Change the WorldFrom EverandInventology: How We Dream Up Things That Change the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- 2.5 Pistas para CriatividadeDocument14 pages2.5 Pistas para CriatividadejamesscheresNo ratings yet

- Inventology Summary - Pagan Kennedy - 12min BlogDocument13 pagesInventology Summary - Pagan Kennedy - 12min BlogVladimir OlefirenkoNo ratings yet

- Czernowin - The Art of Risk TakingDocument9 pagesCzernowin - The Art of Risk TakingtomerhodNo ratings yet

- The Cartesian Methodic DoubtDocument12 pagesThe Cartesian Methodic DoubtIsmael MagadanNo ratings yet

- Ways of Seeing EssayDocument4 pagesWays of Seeing Essayuwuxovwhd100% (2)

- Robert Fisher PSVDocument18 pagesRobert Fisher PSVJiannifen Luwee100% (1)

- PDF Natureculture 03 07 Being One Being MultipleDocument36 pagesPDF Natureculture 03 07 Being One Being MultipleFranciscoNo ratings yet

- Serendipity in Rhetoric, Writing, and Literacy ResearchFrom EverandSerendipity in Rhetoric, Writing, and Literacy ResearchRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Accidental Scientists: The Word Did Not Appear in The Published Literature Until The Early 19th Century and Did NotDocument4 pagesThe Accidental Scientists: The Word Did Not Appear in The Published Literature Until The Early 19th Century and Did Notmyoanh2468No ratings yet

- The Production of Knowledge Is Always A Collaborative Task and Never Solely A Product of The IndividualDocument4 pagesThe Production of Knowledge Is Always A Collaborative Task and Never Solely A Product of The IndividualHarun ĆehovićNo ratings yet

- Isaac Asimov Asks, "How Do People Get New Ideas?"Document8 pagesIsaac Asimov Asks, "How Do People Get New Ideas?"jeldar300No ratings yet

- Final Exam ReviewerDocument8 pagesFinal Exam ReviewerJeus Andrei EstradaNo ratings yet

- Cronin BlaiseDocument16 pagesCronin BlaiseRosa LUZNo ratings yet

- Passage 3 - The Accidental ScientistDocument5 pagesPassage 3 - The Accidental ScientistNguyễn Huỳnh Mai ChâuNo ratings yet

- 139.creating Creative EnvironmentsDocument8 pages139.creating Creative EnvironmentsBouteina NakibNo ratings yet

- Reading 2.Document5 pagesReading 2.Hiền Cao MinhNo ratings yet

- Chase Chance and CreativityDocument2 pagesChase Chance and Creativityas1999bngNo ratings yet

- NaturalismsDocument28 pagesNaturalismsf234369No ratings yet

- Title - The Art of Serendipity - Embracing Chance Discoveries in Science and CreativityDocument2 pagesTitle - The Art of Serendipity - Embracing Chance Discoveries in Science and Creativityhaseeb.hussainy14No ratings yet

- Ernst Von Glasersfeld. The Radical Constructivist View On Science (2001)Document12 pagesErnst Von Glasersfeld. The Radical Constructivist View On Science (2001)alexnotkinNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 Strategic ManagementDocument24 pagesLecture 2 Strategic ManagementKrishnamurthy PrabhakarNo ratings yet

- Human Flourishing HandoutDocument3 pagesHuman Flourishing HandoutThom Steve Ty100% (1)

- Zetetic Scholar No 1Document64 pagesZetetic Scholar No 1neronspanopoulosNo ratings yet

- Practice of ScienceDocument13 pagesPractice of Sciencemariam.vallesNo ratings yet

- Rosanas, J.M. - Methodology and Research in Management (Lectura Sugerida)Document12 pagesRosanas, J.M. - Methodology and Research in Management (Lectura Sugerida)Gonzalo Flores-Castro LingánNo ratings yet

- Barry Stroud - Understanding Human Knowledge (2000)Document267 pagesBarry Stroud - Understanding Human Knowledge (2000)andres felipe100% (3)

- Module 1 - The Nature and Practice of ScienceDocument13 pagesModule 1 - The Nature and Practice of ScienceTOBI JASPER WANGNo ratings yet

- CAM 17, Page-46 - Summary With Clues - Insight or EvolutionDocument4 pagesCAM 17, Page-46 - Summary With Clues - Insight or EvolutionRabby TafsirNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - Human FlourishingDocument4 pagesLesson 1 - Human FlourishingKARYLLE MAE MIRAFUENTESNo ratings yet

- How Do We Know?Document7 pagesHow Do We Know?Michael Smith100% (2)