Galvao 2005

Galvao 2005

Uploaded by

api-3825305Copyright:

Available Formats

Galvao 2005

Galvao 2005

Uploaded by

api-3825305Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Galvao 2005

Galvao 2005

Uploaded by

api-3825305Copyright:

Available Formats

VOLUME 23 䡠 NUMBER 4 䡠 FEBRUARY 1 2005

JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY R E V I E W A R T I C L E

Review of Exercise Intervention Studies in

Cancer Patients

Daniel A. Galvão and Robert U. Newton

From the School of Biomedical and

Sports Science, Edith Cowan Univer-

A B S T R A C T

sity, Joondalup, Australia.

Purpose

Submitted June 14, 2004; accepted

To present an overview of exercise interventions in cancer patients during and after

October 14, 2004.

treatment and evaluate dose-training response considering type, frequency, volume, and

Address reprint requests to Daniel A. intensity of training along with expected physiological outcomes.

Galvão, MS, School of Biomedical and

Sports Science, Edith Cowan Univer- Methods

sity, 100 Joondalup Dr, Joondalup, The review is divided into studies that incorporated cardiovascular training, combination of

Western Australia 6027, Australia; cardiovascular, resistance, and flexibility training, and resistance training alone during and

e-mail: d.galvao@ecu.edu.au.

after cancer management. Criteria for inclusion were based on studies sourced from

© 2005 by American Society of Clinical electronic and nonelectronic databases and that incorporated preintervention and postinter-

Oncology vention assessment with statistical analysis of data.

0732-183X/05/2304-899/$20.00

Results

DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.085 Twenty-six published studies were summarized. The majority of the studies demonstrate

physiological and psychological benefits. However, most of these studies suffer limitations

because they are not randomized controlled trials and/or use small sample sizes. Predomi-

nantly, studies have been conducted with breast cancer patients using cardiovascular

training rather than resistance exercise as the exercise modality. Recent evidence supports

use of resistance exercise or “anabolic exercise” during cancer management as an exercise

mode to counteract side effects of the disease and treatment.

Conclusion

Evidence underlines the preliminary positive physiological and psychological benefits from

exercise when undertaken during or after traditional cancer treatment. As such, other cancer

groups, in addition to those with breast cancer, should also be included in clinical trials to

address more specifically dose-response training for this population. Contemporary resis-

tance training designs that provide strong anabolic effects for muscle and bone may have an

impact on counteracting some of the side effects of cancer management assisting patients

to improve physical function and quality of life.

J Clin Oncol 23:899-909. © 2005 by American Society of Clinical Oncology

pears as the third most common cancer in

INTRODUCTION

the world, and it is ranked as the fifth most

A progressive increase of cancer burden, prevalent cause of death from cancer overall,

with an estimated 15 million new cases and being the leading cause of cancer mortality

10 million new deaths, is expected by the in women.2 Treatments for cancer include

year of 2020.1 In this context, prostate can- surgery as well as systemic and radiation

cer is the sixth most common cancer in the therapy and have successfully shown reduc-

world, representing 14.3% of cancers tions in mortality rates. However, for cancer

among men in developed countries with patients, the increased levels of fatigue dur-

more than 80% of the cases occurring in ing treatment remains a concern as it affects

men older than 65 years.2 Breast cancer ap- the majority of patients during radiotherapy

899

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Galvão and Newton

and/or chemotherapy periods compromising their physical cal and psychological adaptations increasing quality of life

function and quality of life.3-9 Dimeo7,8 has proposed that in this population.

the lack of physical activity during treatment may affect the The purpose of this article is to present a descriptive

increased levels of fatigue observed during and after cancer overview and chronological perspective of developments of

management. As such, several studies examining the role the experimental exercise intervention studies undertaken

of exercise with cancer patients have linked the increased during and after cancer management. The second aim of

levels of physical activity during10-23 and after cancer this review attempts to establish a dose response of training

treatment24-32 with positive effects on decreasing rates of for this population considering type of exercise, frequency

fatigue, enhancing physical performance, and improving of training, volume of training, intensity of training and

quality of life. However, the majority of the exercise inter- expected physiological outcome measures. In addition, we

ventions undertaken with this population have focused on also highlight specific points that should be examined in the

cardiovascular training,10,11,15,17-19,22-24,33-36 with few stud- future with the goal of obtaining more information on

ies using the combination of aerobic and resistance exercise prescription for this population. This review re-

exercises12,16,25,29-31 or resistance exercise alone.20,37 There- ports 26 published studies appearing in the Medline (elec-

fore, little is known as to the effect of resistance training tronic version of Index Medicus) database, published by

being a primary exercise choice to counteract some of the June of 2004 and searched by the terms: exercise; cardiovas-

physiological conditions accompanied by cancer disease and cular training; resistance training; rehabilitation; and can-

the traditional treatments. Considering that most of the exper- cer. Secondary searching involved scanning the reference

imental exercise studies have incorporated breast cancer lists from the papers identified above and then locating

patients11,18,19,21,38-40 and other types of cancer10,17,23,24,37 papers that appeared useful in reviewing the topic. A key

but not prostate cancer, there is a particular lack of infor- criterion throughout this process was identifying studies

mation on how prostate cancer patients undertaking tradi- that incorporated preintervention and postintervention as-

tional treatment would respond to an exercise program. sessment with statistical analysis of the data.

Yet, given the documented effects of androgen deprivation

therapy (ADT),41-49 these patients should benefit particu- EXPERIMENTAL EXERCISE STUDIES DURING

larly from resistance exercise. To date, only one published CANCER TREATMENT

report has examined the effects of a short-term resistance

exercise program on patients diagnosed with prostate can-

A summary of the published studies examining the effect of

cer undertaking ADT.20 Interestingly, they reported quite

exercise on cancer patients undertaking treatment is shown

promising results. In view of the extensive scientific litera-

in Table 1. Of the 18 experimental exercise interventions

ture supporting resistance training as being the most effec-

under cancer treatment, 14 had used some type of cardio-

tive method available for improving muscle strength and

vascular training,10,11,13-15,17-19,21,23,33-35,38,40 two had used

increasing lean tissue mass in different populations ranging

a mixed training program using cardiovascular, resistance,

from athletes to frail older adults,50-60 resistance exercise

and flexibility exercises12,16 while the other two studies ap-

may also have a great potential to counteract the side effects

plied a structured resistance training program.20,37 The

of prostate cancer during ADT by increasing muscle func-

main outcome measures from these studies include: levels

tion, lean tissue mass, and bone mineral density with sub-

of fatigue,11,20,35,40,69 quality of life, emotional-related dis-

sequent reduction in levels of fatigue.

tress,11,12,15,16,19,23,33,35 immunological parameters,13,14,17,24, aer-

There are specific training variables involving resis-

obic capacity,10-12,14-19,21,23,33,35,39,40 and muscle strength.12,16,20

tance exercise prescription that include number of sets and

repetitions (volume), intensity of training (load), duration Cardiovascular Training

of rest between sets and exercises, frequency of training, and The first study by Winningham et al38 examined the

repetition velocity.39,61,62 Currently, there is no informa- effect of a 10-week aerobic program performed three times

tion with regard to such training variables and possible per week on nausea responses of patients with breast cancer

variations with cancer patients undertaking resistance undertaking chemotherapy. Subjects were randomly as-

training programs. Interestingly, some of these variables signed to a supervised aerobic exercise group three times

have been examined in untrained older adults54,63-66 and per week, a placebo group that performed low-intensity

favorable responses in strength and function result from a supervised flexibility training once weekly, or a control

variety of training regimens, even those that involve rela- nonexercise group. Nausea responses to training were as-

tively low intensities,54,64,67 frequencies,65 and volume.63,68 sessed by a self-report system inventory (Symptom Check-

Considering the detrained state and high levels of fatigue of list-90-R; Pearson Assessments, Eagan, MN). The exercise

many cancer patients, it may be expected that even a train- group improved significantly more on symptoms of nausea

ing program consisting of lower intensity, volume, and compared with control and placebo groups (P ⬍ .05). Con-

frequency could significantly promote positive physiologi- sidering that nausea is a consistent symptom experienced by

900 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Exercise in Cancer Patients

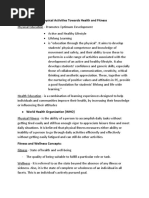

Table 1. Experimental Design Exercise Studies During Cancer Treatment

Study Frequency No. of Age

(Reference Number) Duration (weeks) Patients Sex (years) Type of Cancer Exercise Program Intensity Outcome Measures

Cunningham et al, 5 3-5/week 40 M, W 14-44 Leukemia Resistance training Unspecified 2 Nitrogen balance

198649 7 Creatinine excretion

7 AC

Winningham et al, 12 3/week 42 W 45-48 Breast Cardiovascular cycling 60-85% MHR 2 Nausea

198850 IT 20-30 minutes

Winningham et al, 12 3/week 24 W 45 Breast Cardiovascular cycling 60-85% MHR 1 Lean tissue mass

198948 IT 20-30 minutes 2 0.5% Body fat

2 Skinfold sites

Macvicar et al, 10 3/week 45 W 43-46 Breast Cardiovascular cycling 60-85% MHR 1 42% VO2max

198930 IT

Mock et al, 6 4-5/week 46 W 35-64 Breast Cardiovascular walking Self-paced 1 4% 12-MWT

199723 20-30 minutes 2 Fatigue

2 Symptom experience

Dimeo et al, ⵑ2 Daily 70 M, W 39-40 Breast, sarcoma, Cardiovascular cycling 50% HRR 2 14% MP, 2 Thro

199729 carcinoma, IT 30 minutes 2 Neutro, 2 Hosp

adenocarcinoma,

neuroblastoma

Dimeo et al, 6 5/week 5 M, W 18-55 Hodgkin’s lymp., Non- Progressive treadmill 3 mmol/L (LC) 2 100% LC

199822 Hodgkin’s lymp., walking 30-35 80% MHR 2 18% Heart rate

bronchial, breast, minutes 1 101% TD

medulloblastoma 1 12% MP

Dimeo et al, * Daily 59 M, W 40 Breast, lung Cardiovascular cycling 50% HRR 2 Psychologic distress

199935 Carcinoma, IT 30 minutes

seminoma,

Adenocarcinoma,

Hodgkin’s lymp.

Schwartz et al, 8 4/week 27 W 35-57 Breast Cardiovascular walking Self-paced 1 10.4% 12-MWT

1999, 200046,47 35 minutes accelerometers 2 Fatigue

Na et al, 200025 2 5/week 35 * 28-75 Stomach Cardiovascular arms and 60% MHR 1 28% NKCA

cycling ergometers

30 minutes

Schwartz et al, 8 3–4/week 72 W 27-69 Breast Cardiovascular walking Self-paced 1 15% 12-MWT

200152 12 minutes accelerometers 2 Fatigue

Mock et al, 6-24 5-6/week 52 W 28-75 Breast Cardiovascular walking Self-paced 1 6% 12-MWT

200131 10-30 minutes 2 Fatigue

2 Emotional distress

Segal et al, 26 5/week 123 W 51.4 Breast Cardiovascular walking, 50–60% VO2max 1 Physical functioning

200145 home vs. non-home 7 Quality of life

based 7 VO2max

Kolden et al, 16 3/week 40 W 45–76 Breast Cardiovascular walking, Unspecified 1 11% Flexibility

200224 cycling, stepping, 1 15.4% VO2max

resistance training, 1 34.5% UB

flexibility 1 37% LB

2 5% RSBP

1 Quality of life

Segal et al, 12 3/week 155 M 68.2 Prostate Resistance training, 2 60–70% 1-RM 1 42% UB

200332 sets, 12 repetitions 1 36% LB

7 Body composition

7 PSA, 2 Fatigue

1 Quality of life

Dimeo et al, ⵑ2 Daily 66 M, W 20–73 Leukemia, Hodgkin’s Cardiovascular walking 70% MHR 7 Walking speed

200326 lymp., non- 2 6.7% HEM

Hodgkin’s lymp.,

myeloma

Courneya et al, 16 3–5/week 102 M, W 61.1 Colorectal Cardiovascular walking, 65–75% MHR 7 Quality of life

200327 flexibility 7 Cardiovascular capacity

Adamsen et al, 6 4/week 23 M, W 18–63 Leukemia, breast, Resistance training, 3 60–100% MHR 1 32.5% WB

200328 colon, ovary, testis, sets, 5–8 repetitions; 85–95% 1-RM 1 16% VO2max

cervix, Hodgkin’s cardiovascular 7 Quality of life

lymp., non- cycling; relaxation

Hodgkin’s lymp.

Abbreviations: M, men; W, women; 7, no change; 1, increase; 2, decrease; *, not described; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; LC, lactate concentration;

VO2max, maximum concentration of oxygen consumption; lymp., lymphoma; IT, interval training; TD, training distance; MHR, maximum heart rate; MP,

maximal performance (MET); HEM, hemoglobin; AC, arm circumference; UB, upper body strength; LB, lower body strength; WB, whole body strength; RSBP,

resting systolic blood pressure; NKCA, natural killer-cell cytotoxic activity; HRR, heart rate reserve; Neutro, duration of neutropenia; Thro, duration of

thrombopenia; Hosp, duration of hospitalization.

www.jco.org 901

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Galvão and Newton

cancer patients during treatment, these preliminary data A progressive walking treadmill program up to 30 to 35

showed that cardiovascular training can safely be incorpo- minutes with intensity set to elicit a blood lactate level of 3

rated during breast cancer traditional treatment and may mmol/L in capillary blood was prescribed. At the end of the

decrease symptoms of nausea. Winningham et al36 also pre- intervention, walking distance, walking maximal perfor-

sented data related to a subgroup of their earlier report,38 mance, heart rate, and lactate concentration were improved

which examined the effect of a 10- to 12-week aerobic training (P ⬍ .05) demonstrating once more the positive physiolog-

program on body composition responses of breast cancer sub- ical responses accrued with cardiovascular training. In ad-

jects undertaking chemotherapy. Subjects were randomly al- dition, the authors also noted a clear decrease in levels of

located to an exercise group that trained three times per week fatigue at post-test. Subsequently, in 1999, the same group

for 20 to 30 minutes with intensity set at 60% to 80% of of investigators23 also examined a daily exercise protocol

maximal heart rate or a control group that did not receive the consisting of a supine bike program followed by an interval

exercise treatment. Although elementary techniques for body training pattern for 30 minutes in cancer patients receiving

composition determination, such as skinfold measurement, high doses of chemotherapy. Outcome measures included

were used in this intervention, the results were an increase in psychological distress and levels of fatigue. It was demon-

lean tissue mass for the training group compared with the strated at the end of the intervention that subjects under-

control group. Considering the specificity of the training taking the exercise program significantly decreased

program in this study (aerobic exercise only), the relative in- psychological distress with no changes in fatigue levels.

crease in lean tissue mass may be attributed to the decreased fat Schwartz et al34,35 reported results from a 8-week

tissue. exercise intervention in 27 women with breast cancer un-

The effect of a 10-week aerobic interval training pro- dertaking chemotherapy. The exercise program included a

gram was also investigated by MacVicar et al.18 Forty-five home-based walking program with self-paced intensity

women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy were measured by an accelerometer. Subjects who underwent the

randomly assigned to an aerobic exercise group (cycling exercise program demonstrated greater response in the

training), a flexibility training group, or a control group. physical performance assessment (12-minute walk test), as

Exercise intensity was set at 60% to 85% of the maximum well as decreasing levels of fatigue compared with subjects

heart rate reserve. Results demonstrated differences for who did not adopt the training program (P ⬍ .05).

maximum oxygen uptake (VO2MAX) and testing time The short-term effect of cardiovascular training on

among groups; the aerobic training group improved signif- natural killer-cell cytotoxic activity (NKCA) in patients

icantly more than the flexibility and control groups. with stomach cancer were reported by Na et al.13 Subjects

Mock et al11 examined the effect of a randomized were assigned to an exercise group that performed 30 min-

controlled-trial home-based exercise program on 46 utes of supervised cardiovascular training using arm and

women with breast cancer undertaking radiotherapy. The cycle ergometer or a nonexercise control group. Blood sam-

exercise program consisted of a 20- to 30-minute self-paced ples were collected at baseline, day 7, and day 14. At post-

walking program, four to five times per week over 6 weeks. test, a significantly greater increase in NKCA was noted for

A 12-Minute Walk Test, Symptom Assessment Scales, and the exercise group (27.9%) compared with the control

the Piper Scale were used to assess physical function, symp- group (13.3%; P ⬍ .05). Although the training period was

toms experience, and fatigue, respectively. Results showed short in duration, it is interesting to note that both groups

that subjects undertaking the exercise program improved had similar values for NKCA at the midpoint of interven-

significantly more in walking distance, symptom experi- tion, with the differences between groups occurring during

ence (anxiety, depression, and difficulty sleeping), and fa- the second half of the training period.

tigue compared with controls. Schwartz et al40 also investigated the relationship of

The effect of a daily bed cycling program during high- fatigue and exercise through a home-based aerobic exercise

dose chemotherapy treatment in cancer patients followed program consisting of a 12-minute walk in women under-

by autologous peripheral blood cell transplantation was going chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer. Func-

reported by Dimeo et al.17 Subjects from the control group tional abilities were assessed through a 12-minute walk test

experienced significantly higher loss of physical perfor- and fatigue levels by a self-reported instrument. The exer-

mance levels during hospitalization than the exercise group cise program increased functional ability by 15% whereas

(P ⬍ .05). Moreover, other physiological parameters such the nonexercisers decreased performance by 16%. In addi-

as duration of neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and sever- tion, decreased levels of fatigue (P ⬍ .01) for the exercise

ity of diarrhea were significantly reduced after the exercise group were observed after the intervention. It is interesting

intervention (P ⬍ .05). Dimeo et al10 also reported the to note that the exercise program was unsupervised with

response of a 6-week cardiovascular exercise program on none of the sessions being accompanied by an exercise

fatigue and physical performance in a small sample of can- physiologist. Considering that training program variables

cer patients (n ⫽ 5) experiencing fatigue during treatment. were not well controlled during training, the results are

902 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Exercise in Cancer Patients

somewhat attractive and one would expect even greater program on quality of life and cardiovascular capacity of

adaptations for an exercise program that incorporates a colorectal cancer patients undertaking adjuvant therapy.

more controlled setting resulting in an enormous impact on The exercise group was instructed to perform cardiovascu-

the outcome measures with this population. lar and flexibility activities three to five times per week over

The effect of a similar home-based walking exercise 16 weeks whereas the control group was advised to not

intervention on patients with breast cancer undertaking participate in any exercise activity during the study period.

either radiotherapy or chemotherapy was also examined by No significant differences were observed between groups

Mock et al.19 The exercise program consisted of a progres- for quality of life and cardiovascular capacity at the end of

sive walking (10 to 30 minutes) program 5 to 6 days per the intervention. The failure to detect differences between

week with an unspecified training intensity. Similar to groups is primarily explained by the fact that 51.6% of the

Schwartz et al40 and their previous report,11 physical func- control group did not comply with the study and exercised

tion was assessed by the 12-Minute Walk Test. In addition, during the study period. The nature of the exercise itself

fatigue and emotional distress were measured by the Piper (home-based program) was pointed out by the authors as

Scale and Profile of Mood States (POMS), respectively. Con- being one possible reason of the high contamination during

sistent with their previous findings,11 the exercise intervention the intervention with little effectiveness.

lead to a significant improvement in physical performance by

increasing walking distance. Additionally, fatigue and emo- Cardiovascular, Resistance, and

tional distress were enhanced at post-test, indicating once Flexibility Training

more that positive psychological outcomes may be achieved Kolden et al12 examined the effect of an exercise train-

with a simple home-based walking exercise program. ing intervention including cardiovascular, resistance, and

Segal et al33 conducted a randomized controlled trial flexibility training over 16 weeks in patients with breast

examining the effect of a supervised and unsupervised walking cancer undertaking some type of adjuvant therapy (radio-

program on patients with breast cancer undertaking treatment therapy, chemotherapy, or hormonal therapy). Subjects

(radiotherapy, hormonal therapy, or chemotherapy) over 26 were tested for resting blood pressure, body composition,

weeks. Aerobic capacity, body weight, and generic and disease- aerobic capacity, flexibility, and strength. In addition, nu-

specific health-related quality of life were assessed (MOS SF- merous psychological outcomes were also examined using

36) at baseline and post-test. Results demonstrated that the Beck Depression Inventory, State-Trait Anxiety Inven-

physical function measured by the MOS SF-36 decreased in tory, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, Hamilton Scale

the control group while it increased in both training groups for Depression, Quality of Life, and Global Assessment

(P ⬍ .05). At post-test, no differences among groups were Scale. At the end of the intervention, there was an observed

detected for quality of life, aerobic capacity, or body weight. effect for time for upper and lower body strength, cardio-

However, when groups were stratified by type of adjuvant vascular capacity (estimated VO2max), flexibility, and resting

therapy, in this case not receiving chemotherapy, differences in systolic blood pressure (P ⬍ .05). Additionally, subjects

improvement were observed between the supervised and con- experienced positive psychological adaptations with train-

trol group for aerobic capacity (P ⬍ .01). It is relevant to point ing improving some of the quality-of-life measures.

out that the small changes in aerobic capacity (3.5%) may be Recently, Adamsen et al,16 examined the effect of a high-

related to the nonspecific aerobic capacity test protocol (step- intensity supervised exercise program on a mixed cancer pop-

ping ergometer) utilized by the authors to assess chronic re- ulation over 6 weeks. The training program included interval

sponse of a walking program. training with intensity set at 60% to 100% of the maximal heart

The effect of 2 weeks of cardiovascular training on a rate, resistance exercises performed at 85% to 95% of 1 repeti-

mixed cancer population undergoing conventional or high- tion maximum (RM) for five to eight repetitions, and relax-

dose chemotherapy during hospitalization was examined ation training. The results demonstrated an increase of 32.5%

by Dimeo et al.14 The training program consisted of a daily in maximal strength (P ⬍ .0001) and 16% improvement in

walking treadmill interval training program with intensity VO2max (P ⬍ .001). Several measures of quality of life were also

set at 70% of the maximum heart rate. Submaximal stress improved; however, no statistically significant values were

test results demonstrated that physical performance re- noted. It is relevant to highlight that this is the first study that

mained unaltered during treatment with significant reduc- incorporates a higher intensity training design; however, the

tions in hemoglobin levels at hospital discharge (P ⬍ .05). absence of a control group and the short duration of the inter-

Although physical performance did not change at post- vention limited the interpretation of the data.

test, results demonstrated that cardiovascular training Resistance Training

may assist on preserving performance status during inten- The earliest published study examining the effects of

sive chemotherapy. resistance exercise was a short-term intervention involving

Finally, Courneya et al15 conducted a randomized con- patients with acute leukemia undertaken by Cunningham

trolled trial examining the effect of a home-based exercise et al.37 Subjects were randomly assigned to two exercise

www.jco.org 903

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Galvão and Newton

groups performing the program either three or five times 2. Four studies had used cardiovascular exercise pro-

weekly or a nonexercising control group. The training pro- grams24,26-28,32 whereas the other four implemented a

gram consisted of several upper and lower body exercises mixed training program using cardiovascular, resistance,

including the chest press, biceps curl, triceps extension, and flexibility exercises.25,29-31 Levels of fatigue, muscle

straight leg raises, knee extension, hip extension, hip abduc- strength,29,31 cardiovascular function,24,26-31 immunologi-

tion, shoulder retractors, and sit-ups performed with 15 cal parameters,24,27,28,31 symptoms of emotional-related

repetitions at an unspecified intensity. Outcome measures distress, and quality of life25,27,29,30,32 were the major out-

included skinfold measures, arm circumference, nitrogen come measures from these studies.

balance, and creatinine excretion. Results indicated that

groups did not change arm circumference and skinfold Cardiovascular Training

measures over the course of the intervention. Although Sharkey et al26 conducted the first experimental exer-

there were no differences among groups for nitrogen bal- cise study examining the chronic response of a 12-week

ance during the course of the study, the authors suggested cardiovascular training program on children and young

that the exercise program favored both training groups with adults with mixed cancer diagnosis who had completed

the control group decreasing levels of creatinine excretion chemotherapy for at least 1 year. Outcome measures in-

from pretest to post-test (P ⬍ .05). cluded cardiovascular and pulmonary physiological re-

Recently, Segal et al20 reported the results from a 12- sponses. Although none of the physiological parameters

week whole body resistance training intervention in pa- changed with training, exercise tolerance assessed by exer-

tients with prostate cancer undergoing ADT. The resistance cise time was increased significantly (P ⬍ .05).

training program consisted of two sets of 8 to 12 repetitions The effect of cardiovascular training on NKCA, mono-

at 60% to 70% of 1 RM for six upper body and three lower cytes, and personality was examined in a group of breast

body exercises performed three times per week. Outcome cancer survivors by Peters et al.27,28 Their training program

measures included fatigue, disease-specific quality-of-life consisted of 30 to 40 minutes of cycling at approximately 60%

assessment, and muscle strength and body composition. of maximum heart rate performed five times per week during

Results showed positive effects of resistance training on the first 5 weeks of training with a subsequent reduction of

decreasing fatigue levels, health-related quality of life, and training frequency for the following 6 months completing a

muscle strength with no changes in body composition by total 7-month training period. Although NKCA cell numbers

the subjects embarking on the exercise program. The fact were unaltered over the course of the intervention, an increase

that body composition was unaffected by the training pro- in the cytotoxic activity was noted at post-test. While the total

gram may be related in part to the elementary body composi- number of leukocytes was unchanged after the training pro-

tion methods used to assess changes in muscle and fat tissue. In gram, significant changes in leukocyte subpopulations were

addition, it is well known that strength gains during the first detected with an increased number of granulocytes and a de-

stages of resistance training are predominantly caused by neu- creased number of lymphocytes and monocytes (P ⬍ .05). The

ral factors with gains in muscle size becoming dominant as authors suggested that cardiovascular training would possibly

training continues.70-72 Consequently, the shorter duration of alter the number of specific receptors in the surface membrane

the intervention and the limitations on body composition on monocytes. Moreover, satisfaction of life increased in the

assessment methods indicated that increases in strength were first 5 weeks of training with a subsequent decrease during the

likely to be related to neural alterations rather than muscle other 6 months of the intervention.

morphological changes. These preliminary data showed opti- Dimeo et al24 examined the effects of a cardiovascular

mistic outcomes with a resistance training program that is training program on maximal performance and hemoglo-

characterized primarily by anaerobic rather than aerobic en- bin levels of cancer patients directly after hospital discharge.

ergy sources. Taking into consideration that immunological The exercise program consisted of 6 weeks of treadmill walking

parameters were not assessed in this particular study, it re- every weekday with intensity set to elicit a blood lactate level

mains to quantify if resistance training may positively alter the of 3 mmol/L in capillary blood. Results indicated that sub-

immune system of patients under cancer treatment. In addi- jects that underwent the exercise program showed a significant

tion, it would be interesting to examine how other types of increase in maximal performance and hemoglobin concentra-

cancer patients would respond with resistance exercises. tion compared with controls (P ⬍ .05).

The effects of 10 weeks of cardiovascular exercises on

women who had undergone breast cancer treatment were

EXPERIMENTAL EXERCISE STUDIES AFTER examined by Segar et al.32 Subjects were randomly allocated

CANCER TREATMENT

to an exercise group, exercise plus behavior modification

group, or a control group in an experimental crossover design.

Experimental studies examining the effect of exercise on Symptoms of depression, state of anxiety, and self-esteem

patients with cancer after treatment are presented in Table were assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory, the State

904 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Exercise in Cancer Patients

Table 2. Experimental Design Exercise Studies After Cancer Treatment

Frequency No. of Age

Study Duration (weeks) Patients Sex (years) Type of Cancer Exercise Program Intensity Outcome Measures

Sharkey et al, 12 2/week 10 M, W 19 Leukemia, Ewings Cardiovascular 60–80% MHR 10% ET, 7 AT

199338 tumor, * 7 Peak OX

neuroblastoma 7 Peak HR

Wilms’ tumor,

rhabdomyosarcoma

Peters et al, 28 2-5/week 24 W 49 Breast Cardiovascular ⵑ 60% MHR 12 Satisfaction of life

1994, cycling 7 NKCA

199539, 40 7 Leukocytes

2 2.1% Lymphocytes

2 1.1% Monocytes

1 4.1% Granulocytes

Nieman et al, 8 3/week 12 W 61 Breast Cardiovascular 75% MHR 7 NKCA

199543 resistance 7 LB

training 1 6-minute Walk Test

Dimeo et al, 6 5/week 36 M, W 39–42 Non-Hodgkin’s Cardiovascular 3 mmol/L (LC) 1 32% MP

199736 lymp., breast, walking 30 1 30% HEM

sarcoma, minutes

seminoma, lung

Segar et al, 10 4/week 24 W 30–65 Breast Cardiovascular ⫽ 60% MHR 2 Depression

199844 30–40 minutes 2 Anxiety

Durak et al, 10 2/week 20 M, W 50 Carcinoma, Cardiovascular Own RPE 1 43% WB, 41.4% 1 MP

199841 lymphoma, resistance 1 Quality of life

leukemia training,

flexibility

Durak et al, 20 2/week 25 M, W 44-71 Prostate carcinoma, Cardiovascular Unspecified 7 Aerobic capacity

199942 leukemia resistance 1 45% WB

training

Porock et al, 4 * 9 M, W 51-77 Bowel, breast, oral, Cardiovascular Unspecified 2 Depression

200037 pancreas, resistance 2 Anxiety

melanoma training 7 Fatigue

Abbreviations: M, men; W, women; 7, no change; 1, increase; 2, decrease; 1 2, increased at week 5 and decreased at posttest; *, not described; LC,

lactate concentration; MHR, maximum heart rate; MP, maximal performance (MET); HEM, hemoglobin; LB, lower body strength; WB, whole body strength;

NKCA, natural killer-cell cytotoxic activity; ET, exercise tolerance; AT, anaerobic threshold; peak OX, peak oxygen uptake; peak HR, peak heart rate.

Anxiety Inventory, and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Inventory, distance test compared with controls (P ⬍ .05). However,

respectively. At post-test, it was observed that the exercise differences between groups were neither observed for lower

group had significantly less depression and state of anxiety body strength nor for NKCA. It should be noted that the small

compared with controls with no differences between exercise sample size (n ⫽ 6 per group) limited the ability to detect

and exercise plus behavior modification groups. After the significant difference between groups.

crossover, the controls also showed optimistic changes by de- Durak et al29 conducted an exercise intervention in a

creasing depression and state of anxiety showing positive psy- mixed cancer patient population over 10 weeks. The exer-

chological response accrued with cardiovascular training. cise program was performed twice weekly and consisted of

Cardiovascular, Resistance, and cardiovascular training at their own perceived exertion,

Flexibility Training resistance training machines using unspecified intensity,

The effects of an exercise program on breast cancer and flexibility exercises. Outcome measures included qual-

survivors who had undergone surgery, radiation, and che- ity of life (Modified Rotterdam Quality of Life Survey),

motherapy were examined by Nieman et al.31 Subjects were endurance capacity, and a four- to six-repetition maximum

randomly assigned to an exercise or control group. In addi- strength test. Results demonstrated an average increase of

tion to physical performance measures that included 43% for both upper and lower body strength combined and

symptoms-limited exercise testing on the treadmill, 6-minute a 41.4% increase in MET level from the first to the last

walk test and lower body strength, immunological training session of the exercise program. In addition, the quality of

response was also assessed by measuring NKCA and concen- life assessment indicated a significant improvement in par-

trations of circulating immune cells. The training program ticipants’ ability to perform daily functions. The same

included 30 minutes of walking at 75% of heart rate maximum group of investigators30 also examined the effect of a 20-

and seven different resistance exercises performed for 12 rep- week cardiovascular and resistance training program on

etitions at an unspecified intensity. Results indicated signifi- survivors of prostate cancer, carcinoma, and leukemia. The

cant improvement for the exercise group on 6-minute walk exercise protocol was described with little detail in the

www.jco.org 905

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Galvão and Newton

original manuscript; therefore it is unclear what intensity should be taken of the recent report from Segal et al20 who

and volume were applied during the exercise intervention reported positive effects of resistance exercises alone on

for both cardiovascular and resistance exercises. In addi- rates of fatigue, health-related quality of life, and muscle

tion, neither strength maximum nor cardiovascular capac- strength in patients with prostate cancer undertaking ADT.

ity tests were implemented at pretest and post-test; Although these results support positive psychological and

therefore it was extremely difficult to analyze the authors’ physical outcomes, it remains to be examined how specific

presented data. At post-test, subjects completed a quality- physiological parameters such as muscle tissue mass and

of-life survey with the same questionnaire being reassessed bone mineral density would respond with resistance exer-

in a 2-year follow-up period. It was reported that the train- cises in this population, especially in long-term trials. Re-

ing protocol induced an increase of 38% and 52% for over- cently, Smith et al43 reported an increase of 11% of fat mass

all strength in the prostate cancer and carcinoma/leukemia and a decrease of 3.8% of lean-free bone tissue mass from a

groups, respectively. No significant change was noted for aer- year-long prospective assessment of the effects of ADT on

obic capacity. It is interesting to point out the high level of body composition responses evaluated by dual energy x-ray

adherence to the exercise program from both groups with absorptiometry. Further, the concern related to the negative

subjects from the prostate cancer group having 100% compli- effects of ADT on accelerating bone loss has been exten-

ance to the training program whereas the carcinoma/leukemia sively reported in the literature.46,75-83 As an alternative,

group recorded 65% of adherence over the 2-year period. resistance exercise studies in older adults have consistently

Finally, Porock et al25 investigated the effect of a short- shown it to be a safe and effective strategy to counteract

term home-based exercise intervention in a mixed popula- sarcopenia50,54-57,59,84,85 and preserve or induce gains in

tion of cancer patients. The training program appears to bone mineral density84,86-88. Recently, Villareal et al86 re-

include both cardiovascular and resistance exercises but ported positive effects of a 9-month resistance training pro-

lacked an exact description of training program variables gram on bone mineral density in older women undertaking

(intensity, frequency, and volume). Outcome measures in- hormonal replacement. A meta-analysis undertaken by

cluded fatigue, anxiety, depression, symptoms of distress, Wolff et al89 also proposes that resistance training preserves

and quality of life. Results indicated positive adaptations for or reverses bone loss of up to 1% per year in both femoral

depression and anxiety with no change in fatigue levels. It neck and lumbar spine sites for pre- and postmenopausal

should be noted that the short-term duration of the inter- women. Taking into consideration the long-term benefits

vention and the small sample size (n ⫽ 9) limited the ability of this exercise modality on bone response, resistance train-

to detect significant changes with training. ing may have an important role on reducing the effect of

bone loss rate in men with prostate cancer undertaking

ADT. Moreover, considering that, traditionally, ADT varies

DISCUSSION

from 2 to 3 years but can also take up to 20 years,90 the role

of resistance exercise may be even more relevant by improv-

The primary aim of this article was to present an overview of ing psychological and physiological parameters and, there-

published studies undertaken with any cancer population fore, improving quality of life.

during and after treatment. Unfortunately, most of these In the context of maintaining or increasing lean tissue

studies suffer limitations because they are not randomized content in healthy elderly and various patient populations in

controlled trials, use small sample sizes, and/or report in- which muscle and bone loss are problematic, resistance exer-

sufficient scientific methodological criteria. Despite this, it cise might be more appropriately termed “anabolic exercise.”

appears that there is a reasonable amount of data in the It is not surprising, therefore, that the many cardiovascular

literature that underline preliminary positive physiological exercise interventions with cancer patients have produced

and psychological benefits from exercise when undertaking mixed results as such exercise does not provide a strong ana-

during or after traditional cancer treatment. It is interesting bolic effect for muscle and bone and may not elicit the changes

to point out that the early published report on cancer and in endocrine status that are desirable in these patients.

exercise by Cunningham et al37 used resistance exercises as It is interesting to note that, among the different cancer

the training modality that was based on the original work by types, breast cancer has been the most common cancer type

Delorme,73,74 who introduced the model of progressive examined during exercise trials. Of the 18 studies undertaken

workload with resistance exercises. Subsequently, the ma- during treatment, nine had used exclusively breast cancer

jority of studies examining the effect of exercise on cancer subjects11,12,18,19,21,33-35,38,40 with three studies including

patients undertaking treatment completed from the late breast cancer plus a mix of cancer populations10,17,23 and few

1980s to 2003 implemented the cardiovascular training other experiments using leukemia, stomach cancer, prostate,

modality10,11,13,15,17-19,23,33-36,38,40 with only two interven- colorectal, and a mix population of cancer types.13,15,16,20,37

tions using the combination of resistance, flexibility, and A similar figure can be observed with the experimental trials

cardiovascular training.12,16 Therefore, particular attention undertaken after cancer treatment where three studies were

906 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Exercise in Cancer Patients

Table 3. Guidelines and Possible Physiological Outcomes from Exercise in Cancer Patients

Frequency

Exercise Modality Intensity (/week) Volume Dosage Cancer Relevant Expected Outcomes

Cardiovascular exercises 55-90% MHR 3-5 20-60 minutes Continuous or intermittent 1 Cardiopulmonary function

40-85% MHRR 1 Insulin sensitivityⴱ, 1 HDLⴱ, 2 LDLⴱ

2 Fat mass, 2 Fatigue

Anabolic/resistance 50-80% 1-RM 1-3 1-4 sets per muscle 1 Muscle massⴱ, 1 Muscle strength

exercises 6-12 RM group 1 Muscle powerⴱ, 1 Muscle endurance

1 BMDⴱ, 1 FP, 2 Fatigue

1 Resting metabolic rateⴱ, 2 Fat massⴱ

Flexibility exercises ? 2-3 2-4 sets per muscle 10-30 seconds 17 Range of motion

group

Abbreviations: 1, increase; 2, decrease; 7, no change; MHR, maximum heart rate; MHRR, maximum heart rate reserve; HDL, high-density lipoprotein;

LDL, low-density lipoprotein; BMD, bone mineral density; FP, functional performance; RM, repetition maximum.

ⴱ

Data not available with cancer population, recommendation based from studies undertaken with noncancer population.

conducted with breast cancer patients,27,28,31,32 three in a spite the work by Segal et al33 and Cunningham et al,37

mixed cancer population including breast cancer,24,25,29 which compared a home-based versus supervised exercise

and two in a mixed cancer population not including breast and five times versus three times weekly resistance exercises,

cancer.26,30 Therefore, future studies aiming to examine the respectively, none of these studies had actually used more

role of exercises in cancer populations should also include than one training protocol, attempting to compare differ-

other cancer types than breast to reveal possible physiolog- ences in training response due to various intensities, fre-

ical and psychological benefits from exercise among other quencies, volume, and type of training. Consequently, a

cancer groups. requirement for future studies on this topic should include

As a secondary purpose of this review, we attempted randomized controlled trials comparing how various types

to establish a training dose-response with this population of cancer undergoing different treatments and stages of the

based on the existing literature. The importance of scientific disease would respond to different training stimuli.

exercise principles has been extensively reported.39,61,62,91 Finally, the majority of the studies involving resistance

It is well known that manipulation of the training pro- training did not draw on the wealth of scientific research that

gram variables of frequency of training, intensity of has been published in regard to resistance training for muscle

training, specificity of training, and rest period between hypertrophy and strength gain. In all cases excepted one,16 the

sets and exercise sessions produces clearly differentiated intensity of exercise in particular was inferior to the 6 to 10 RM

effects on specific physiological adaptations for both car- load that has been deemed optimal for muscle growth and

diovascular and resistance exercise. Nevertheless, long-

strength enhancement.61,62 One of the better designed resis-

term trials comparing different training models are rare

tance training interventions addressed in this review was by

even in healthy adult populations as reported by the

Cunningham et al37 and yet their model was based on research

American College of Sports Medicine position stand on

completed around 1950.73,74 Moreover, the only study that

the recommended quantity and quality of exercise pre-

incorporated a better-quality training intensity limited the

scription in healthy adults.39 Therefore, most of the stud-

program to 6 weeks and performed no more than three resis-

ies presented in this review that aim to elucidate training

tance exercises.16 Although much more research is required in

response for cancer patients during and after treatment,

were short in duration10,13,14,16,18,20,24,25,29,31,32,34-38,40 this important area, some guidelines and possible physiologi-

with some interventions still not controlling elementary cal outcomes are provided in Table 3. Future research into

training variables.12,25,29,30,92 The short-term nature of exercise interventions with cancer patients should involve con-

these interventions would likely limit the ability to detect temporary resistance training program designs incorporating

specific physiological responses with training. Moreover, adequate intensity, periodization, selection of functional exer-

considering that exercise has been endorsed as a crucial cises involving large muscle groups, and manipulation of rest

component of a healthy lifestyle and is viewed as a lifelong period and recovery strategies to maximize the anabolic effect

behavior that may prevent and control various disease on muscle and bone as well as positive endocrine responses.

conditions,93-96 further studies undertaken for longer peri- ■ ■ ■

ods are needed. Additionally, the specific training dose for

this population and how it would differentiate from many Authors’ Disclosures of Potential

of the cancer types, treatment modalities, and stages of Conflicts of Interest

treatment remains an open area for prospective trials. De- The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

www.jco.org 907

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Galvão and Newton

18. MacVicar MG, Winningham ML, Nickel JL: 34. Schwartz AL: Daily fatigue patterns and

REFERENCES Effects of aerobic interval training on cancer effect of exercise in women with breast cancer.

patients functional capacity. Nurs Res 38:348- Cancer Pract 8:16-24, 2000

1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, et al: Estimat- 351, 1989 35. Schwartz AL: Fatigue mediates the effects

ing the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int 19. Mock V, Pickett M, Ropka ME, et al: of exercise on quality of life. Qual Life Res

J Cancer 94:153-156, 2001 Fatigue and quality of life outcomes of exercise 8:529-538, 1999

2. Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J: Global can- 36. Winningham ML, MacVicar MG, Bondoc

during cancer treatment. Cancer Practice 9:119-

cer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 49:33-64, 1999 M, et al: Effect of aerobic exercise on body

127, 2001

3. Irvine D, Vincent L, Graydon JE, et al: The weight and composition in patients with breast

20. Segal RJ, Reid RD, Courneya KS, et al:

prevalence and correlates of fatigue in patients cancer on adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs

Resistance exercise in men receiving androgen

receiving treatment with chemotherapy and ra- Forum 16:683-689, 1989

deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin

diotherapy. A comparison with the fatigue expe- 37. Cunningham AJ, Morris G, Cheney CL:

Oncol 21:1653-1659, 2003

rienced by healthy individuals. Cancer Nurs 17: Effects of resistance exercise on skeletal muscle

21. Winningham ML, MacVicar MG, Bondoc

367-378, 1994 in marrow transplant recipients receiving total

M, et al: Effect of aerobic exercise on body

4. Smets EM, Garssen B, Schuster-Uitterhoeve parental nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr

weight and composition in patients with breast

AL, et al: Fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 10:558-563, 1986

68:220-224, 1993 cancer on adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs

38. Winningham ML, MacVicar MG: The ef-

5. Smets EM, Visser MR, Willems-Groot AF, Forum 16:683-689, 1989

fect of aerobic exercise on patient reports of

et al: Fatigue and radiotherapy: (A) experience in 22. Dimeo F, Stieglitz RD, Novelli-Fischer U, et

nausea. Oncol Nurs Forum 15:447-450, 1988

patients undergoing treatment. Br J Cancer 78: al: Correlation between physical performance

39. American College of Sports Medicine Po-

899-906, 1998 and fatigue in cancer patients. Ann Oncol

sition Stand. The recommended quantity and

6. Smets EM, Visser MR, Willems-Groot AF, 8:1251-1255, 1997

quality of exercise for developing and maintain-

et al: Fatigue and radiotherapy: (B) experience in 23. Dimeo FC, Stieglitz RD, Novelli-Fischer U, ing cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and

patients 9 months following treatment. Br J et al: Effects of physical activity on the fatigue flexibility in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc

Cancer 78:907-912, 1998 and psychologic status of cancer patients during 30:975-991, 1998

7. Dimeo F: Radiotherapy-related fatigue and chemotherapy. Cancer 85:2273-2277, 1999 40. Schwartz AL, Mori M, Gao R, et al: Exer-

exercise for cancer patients: A review of the 24. Dimeo F, Tilman MHM, Bertz H, et al: cise reduces daily fatigue in women with breast

literature and suggestions for future research. Aerobic exercise in the rehabilitation of cancer cancer receiving chemotherapy. Med Sci Sports

Front Radiat Ther Oncol 37:49-56, 2002 patients after high dose chemotherapy and au- Exerc 33:718-723, 2001

8. Dimeo FC: Effects of exercise on cancer- tologous stem cell transplantation. Cancer 79: 41. Pickett M, Bruner DW, Joseph A, et al:

related fatigue. Cancer 92:1689-1693, 2001 1717-1722, 1997 Prostate cancer elder alert. Living with treatment

9. Irvine DM, Vincent L, Graydon JE, et al: 25. Porock D, Kristjanson LJ, Tinnelly K, et al: choices and outcomes. J Gerontol Nurs 26:22-

Fatigue in women with breast cancer receiving An exercise intervention for advanced cancer 34, 54-55, 2000

radiation therapy. Cancer Nurs 21:127-135, 1998 patients experiencing fatigue: A pilot study. J 42. Holzbeierlein JM, McLaughlin MD,

10. Dimeo F, Rumberger BG, Keul J: Aerobic Palliat Care 16:30-36, 2000 Thrasher JB: Complications of androgen depriva-

exercise as therapy for cancer fatigue. Med Sci 26. Sharkey AM, Carey AB, Heise CT, et al: tion therapy for prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol

Sports Exerc 30:475-478, 1998 Cardiac rehabilitation after cancer therapy in chil- 14:177-183, 2004

11. Mock V, Dow KH, Meares CJ, et al: Ef- dren and young adults. Am J Cardiol 71:1488- 43. Smith MR: Changes in fat and lean body

fects of exercise on fatigue, physical functioning, 1490, 1993 mass during androgen-deprivation therapy for

and emotional distress during radiation therapy 27. Peters C, Lotzerich H, Niemeier B, et al: prostate cancer. Urology 63:742-745, 2004

for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 24:991- Influence of a moderate exercise training on 44. Michaelson MD, Marujo RM, Smith MR:

1000, 1997 natural killer cytotoxicity and personality traits in Contribution of androgen deprivation therapy to

12. Kolden GG, Strauman TJ, Ward A, et al: A cancer patients. Anticancer Res 14:1033-1036, elevated osteoclast activity in men with meta-

pilot study of group exercise training (GET) for 1994 static prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 10:2705-

women with primary breast cancer: Feasibility 28. Peters C, Lotzerich H, Niemeir B, et al: 2708, 2004

and health benefits. Psychooncology 11:447- 45. Stege R: Potential side-effects of endo-

Exercise, cancer and the immune response of

456, 2002 crine treatment of long duration in prostate can-

monocytes. Anticancer Res 15:175-179, 1995

13. Na YM, Kim MY, Kim YK, et al: Exercise cer. Prostate Suppl 10:38-42, 2000

29. Durak EP, Lilly PC: The application of an

therapy effect on natural killer cell cytotoxic 46. Diamond TH, Higano CS, Smith MR, et al:

exercise and wellness program for cancer pa-

activity in stomach cancer patients after curative Osteoporosis in men with prostate carcinoma

tients: A preliminary outcomes report. J Strength

surgery. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81:777-779, receiving androgen-deprivation therapy: Recom-

Cond Res 12:3-6, 1998

2000 mendations for diagnosis and therapies. Cancer

30. Durak EP, Lilly PC, Hackworth JL: Physical

14. Dimeo F, Schwartz S, Fietz T, et al: Effects 100:892-899, 2004

and psychosocial responses to exercise in can-

of endurance training on the physical perfor- 47. Hedlund PO: Side effects of endocrine

cer patients: A two year follow-up survey with

mance of patients with hematological malignan- treatment and their mechanisms: Castration, an-

cies during chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer prostate, leukemia, and general carcinoma.

tiandrogens, and estrogens. Prostate Suppl 10:

11:623-628, 2003 J Exercise Physiol Online 2, 1999

32-37, 2000

15. Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Quinney 31. Nieman DC, Cook VD, Henson DA, et al: 48. Cassileth BR, Soloway MS, Vogelzang NJ,

HA, et al: A randomized trial of exercise and Moderate exercise training and natural killer cell et al: Quality of life and psychosocial status in

quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Eur J cytotoxic activity in breast cancer patients. Int stage D prostate cancer. Zoladex Prostate Can-

Cancer Care (Engl) 12:347-357, 2003 J Sports Med 16:334-337, 1995 cer Study Group. Qual Life Res 1:323-329, 1992

16. Adamsen L, Midtgaard J, Rorth M, et al: 32. Segar ML, Katch VL, Roth RS, et al: The 49. Cleary PD, Morrissey G, Oster G: Health-

Feasibility, physical capacity, and health benefits effect of aerobic exercise on self esteem and related quality of life in patients with advanced

of a multidimensional exercise program for can- depressive and anxiety symptoms among breast prostate cancer: A multinational perspective.

cer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Support cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 25:107-113, Qual Life Res 4:207-220, 1995

Care Cancer 11:707-716, 2003 1998 50. Charette SL, McEvoy L, Pyka G, et al:

17. Dimeo F, Fetscher S, Lange W, et al: 33. Segal R, Evans W, Johnson D, et al: Struc- Muscle hypertrophy response to resistance

Effects of aerobic exercise on the physical per- tured exercise improves physical functioning in training in older women. J Appl Physiol 70:1912-

formance and incidence of treatment-related women with stages I and II breast cancer: Re- 1916, 1991

complications after high-dose chemotherapy. sults of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin 51. Kraemer WJ, Hakkinen K, Newton RU, et al:

Blood 90:3390-3394, 1997 Oncol 19:657-665, 2001 Effects of heavy-resistance training on hormonal

908 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Exercise in Cancer Patients

response patterns in younger vs. older men. J Appl 66. Hunter GR, Wetzstein CJ, McLafferty CL vation therapy for prostate cancer. J Urol 163:

Physiol 87:982-992, 1999 Jr., et al: High-resistance versus variable- 181-186, 2000

52. Kraemer WJ, Hakkinen K, Triplett-Mcbride resistance training in older adults. Med Sci 83. Wei JT, Gross M, Jaffe CA, et al: Andro-

NT, et al: Physiological changes with periodized Sports Exerc 33:1759-1764, 2001 gen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer re-

resistance training in women tennis players. 67. Vincent KR, Vincent HK, Braith RW, et al: sults in significant loss of bone density. Urology

Med Sci Sports Exerc 35:157-168, 2003 Strength training and hemodynamic responses 54:607-611, 1999

53. Taaffe DR, Pruitt L, Reim J, et al: Effect of to exercise. Am J Geriatr Cardiol 12:97-106, 84. Nelson ME, Fiatarone MA, Morganti CM,

recombinant human growth hormone on the 2003 et al: Effects of high-intensity strength training

muscle strength response to resistance exercise 68. Taaffe DR, Galvão DA: High- and low- on multiple risk factors for osteoporotic frac-

in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 79:1361- volume resistance training similarly enhances tures. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 272:

1366, 1994 functional performance in older adults. Med Sci 1909-1914, 1994

54. Taaffe DR, Pruitt L, Pyka G, et al: Compar- Sports Exerc 36:142, 2004 (suppl) 85. McCartney N, Hicks AL, Martin J, et al: A

ative effects of high- and low-intensity resistance 69. Mock V: Evaluating a model of fatigue in longitudinal trial of weight training in the elderly:

training on thigh muscle strength, fiber area, and children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 18:13- Continued improvements in year 2. J Gerontol A

tissue composition in elderly women. Clin 16, 2001 Biol Sci Med Sci 51:B425-433, 1996

Physiol 16:381-392, 1996 70. Sale DG: Neural adaptation to resistance 86. Villareal DT, Binder EF, Yarasheski KE, et

55. Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, et al: training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 20:135-145, 1988 al: Effects of exercise training added to ongoing

High-intensity strength training in nonagenari- (suppl) hormone replacement therapy on bone mineral

ans. Effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA 263: 71. Sale DG, MacDougall JD, Upton AR, et al: density in frail elderly women. J Am Geriatr Soc

3029-3034, 1990 Effect of strength training upon motoneuron 51:985-990, 2003

56. Fiatarone MA, O’Neill EF, Ryan ND, et al: excitability in man. Med Sci Sports Exerc 15:57- 87. Kerr D, Morton A, Dick I, et al: Exercise

Exercise training and nutritional supplementation 62, 1983 effects on bone mass in postmenopausal

for physical frailty in very elderly people. N Engl 72. Sale DG: Influence of exercise and training women are site-specific and load-dependent.

J Med 330:1769-1775, 1994 on motor unit activation. Exerc Sport Sci Rev J Bone Miner Res 11:218-225, 1996

15:95-151, 1987 88. Pruitt LA, Taaffe DR, Marcus R: Effects of

57. Frontera WR, Meredith CN, O’Reilly KP, et

73. Delorme TL, Watkins AL: Technics of pro- a one-year high-intensity versus low-intensity

al: Strength conditioning in older men: Skeletal

gressive resistive exercises. Arch Phys Med resistance training program on bone mineral

muscle hypertrophy and improved function.

Rehabil:263-273, 1948 density in older women. J Bone Miner Res

J Appl Physiol 64:1038-1044, 1988

74. Delorme TL, West FE, Shriber WJ: Influ- 10:1788-1795, 1995

58. Hakkinen K, Kallinen M, Linnamo V, et al:

ence of progressive resistance exercises on 89. Wolff I, van Croonenborg JJ, Kemper HC,

Neuromuscular adaptations during bilateral ver-

knee function following femoral fractures. et al: The effect of exercise training programs on

sus unilateral strength training in middle-aged

J Bone Joint Surg Am 32:910-924, 1950 bone mass: A meta-analysis of published con-

and elderly men and women. Acta Physiol Scand

75. Diamond T, Campbell J, Bryant C, et al: trolled trials in pre- and postmenopausal women.

158:77-88, 1996

The effect of combined androgen blockade on Osteoporos Int 9:1-12, 1999

59. Hakkinen K, Kallinen M, Izquierdo M, et al:

bone turnover and bone mineral densities in men 90. Schroder FH: Endocrine treatment: Ex-

Changes in agonist-antagonist EMG, muscle

treated for prostate carcinoma: Longitudinal eval- pected duration stage by stage. Prostate Suppl

CSA, and force during strength training in

uation and response to intermittent cyclic etidr- 10:26-31, 2000

middle-aged and older people. J Appl Physiol

onate therapy. Cancer 83:1561-1566, 1998 91. American College of Sports Medicine Po-

84:1341-1349, 1998

76. Berruti A, Dogliotti L, Terrone C, et al: sition Stand. Exercise and physical activity for

60. Newton RU, Hakkinen K, Hakkinen A, et

Changes in bone mineral density, lean body older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30:992-1008,

al: Mixed-methods resistance training increases mass and fat content as measured by dual 1998

power and strength of young and older men. energy x-ray absorptiometry in patients with 92. Mock V: Fatigue management: Evidence

Med Sci Sports Exerc 34:1367-1375, 2002 prostate cancer without apparent bone metasta- and guidelines for practice. Cancer 92:1699-

61. Kraemer WJ, Adams K, Cafarelli E, et al: ses given androgen deprivation therapy. J Urol 1707, 2001

American College of Sports Medicine Position 167:2361-2367, 2002 93. Thompson PD, Buchner D, Pina IL, et al:

Stand. Progression models in resistance training 77. Smith MR: Osteoporosis during androgen Exercise and physical activity in the prevention

for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 34:364- deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Urology and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular

380, 2002 60:79-86, 2002 disease: A statement from the Council on Clini-

62. Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA: Fundamen- 78. Smith MR, Eastham J, Gleason DM, et al: cal Cardiology (Subcommittee on Exercise, Re-

tals of resistance training: Progression and Randomized controlled trial of zoledronic acid to habilitation, and Prevention) and the Council on

exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc prevent bone loss in men receiving androgen Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism

36:674-688, 2004 deprivation therapy for nonmetastatic prostate (Subcommittee on Physical Activity). Circulation

63. Galvão DA, Taaffe DR: Multiple sets are cancer. J Urol 169:2008-2012, 2003 107:3109-3116, 2003

superior to single sets for enhancing muscle 79. Smith MR, McGovern FJ, Zietman AL, et 94. Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al: Physical

function in older adults. Presented at the Pre- al: Pamidronate to prevent bone loss during activity and public health. A recommendation

Olympic Congress, Thessaloniki, Greece, Au- androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate can- from the Centers for Disease Control and Pre-

gust 6-11, 2004 cer. N Engl J Med 345:948-955, 2001 vention and the American College of Sports

64. Vincent KR, Braith RW, Feldman RA, et al: 80. Stoch SA, Parker RA, Chen L, et al: Bone Medicine. JAMA 273:402-407, 1995

Resistance exercise and physical performance in loss in men with prostate cancer treated with 95. Wei M, Gibbons LW, Kampert JB, et al:

adults aged 60 to 83. J Am Geriatr Soc 50:1100- gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. J Clin Low cardiorespiratory fitness and physical inac-

1107, 2002 Endocrinol Metab 86:2787-2791, 2001 tivity as predictors of mortality in men with type

65. Taaffe DR, Duret C, Wheeler S, et al: 81. Daniell HW: Osteoporosis due to andro- 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med 132:605-611, 2000

Once-weekly resistance exercise improves mus- gen deprivation therapy in men with prostate 96. Wei M, Kampert JB, Barlow CE, et al:

cle strength and neuromuscular performance in cancer. Urology 58:101-107, 2001 Relationship between low cardiorespiratory fit-

older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 47:1208-1214, 82. Daniell HW, Dunn SR, Ferguson DW, et al: ness and mortality in normal-weight, overweight,

1999 Progressive osteoporosis during androgen depri- and obese men. JAMA 282:1547-1553, 1999

www.jco.org 909

Downloaded from www.jco.org at VU Medical Centre, Medical Library on February 6, 2006 .

Copyright © 2005 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Exercise Training in Cancer Control and Treatment PDFDocument41 pagesExercise Training in Cancer Control and Treatment PDFVarun Kumar100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S1836955320300217 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S1836955320300217 Mainjaxad78743No ratings yet

- Exercise in CancerDocument10 pagesExercise in CancerSebastian SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Exercise Prescription in Oncology Patients: General PrinciplesDocument9 pagesExercise Prescription in Oncology Patients: General PrinciplesІра Горинь100% (1)

- Effects of Resistance Exercise On Fatigue and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Adjuvant Chemotherapy - A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument10 pagesEffects of Resistance Exercise On Fatigue and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Adjuvant Chemotherapy - A Randomized Controlled TrialPablo NahuelcoyNo ratings yet

- 10 1634@theoncologist 2019-0463Document15 pages10 1634@theoncologist 2019-0463jenny12No ratings yet

- Enefits of Exercise in Cardio OncologyDocument13 pagesEnefits of Exercise in Cardio OncologyFranco Tabilo AlfaroNo ratings yet

- Winningham 1986Document8 pagesWinningham 1986Christine SiburianNo ratings yet

- Ligibel JA Et Al. 2022 Exercise, Diet and Weight Management During Cancer Treatment - ASCO GuidelineDocument20 pagesLigibel JA Et Al. 2022 Exercise, Diet and Weight Management During Cancer Treatment - ASCO GuidelineJasmyn KimNo ratings yet

- Medical and Cardiac Risk Stratification and Exercise Prescription in Persons With CancerDocument7 pagesMedical and Cardiac Risk Stratification and Exercise Prescription in Persons With CancermarciarigaudNo ratings yet

- Roles y Molecular Mecanismos Del Ejercicio en CancerDocument10 pagesRoles y Molecular Mecanismos Del Ejercicio en CancerGabriela Araya MedranoNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer PDFDocument10 pagesBreast Cancer PDFHadley AuliaNo ratings yet

- friedenreich2016Document11 pagesfriedenreich2016riadh.dahmenNo ratings yet

- Artigo 9Document12 pagesArtigo 9Átrio Reabilitação CardiopulmonarNo ratings yet

- J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle - 2016 - Klassen - Muscle Strength in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Different TreatmentDocument12 pagesJ Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle - 2016 - Klassen - Muscle Strength in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Different TreatmentVukašin Schooly StojanovićNo ratings yet

- Excercise Intervention Meta AnalysisDocument11 pagesExcercise Intervention Meta Analysisansantiago.mendezzNo ratings yet

- Effects of Physiotherapy On Breast Cancer Related Secondary Lymphedema: A Systematic ReviewDocument7 pagesEffects of Physiotherapy On Breast Cancer Related Secondary Lymphedema: A Systematic ReviewPCT LOULENo ratings yet

- Exercise Guidelines For Cancer SurvivorsDocument34 pagesExercise Guidelines For Cancer SurvivorsSebastian SaavedraNo ratings yet

- ArticuloDocument14 pagesArticuloLeidy Katherine Villamil CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Exercise Prescription Cancer y Hematologia - 231009 - 142451Document13 pagesExercise Prescription Cancer y Hematologia - 231009 - 142451Carlos AvilaNo ratings yet

- Telehealth System (e-CUIDATE) To Improve Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors: Rationale and Study Protocol For A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument10 pagesTelehealth System (e-CUIDATE) To Improve Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors: Rationale and Study Protocol For A Randomized Clinical TrialCaroPlachotNo ratings yet

- Nihms 432244Document12 pagesNihms 432244Zuri S. GalindoNo ratings yet

- Cancers 14 05402 v2 PDFDocument43 pagesCancers 14 05402 v2 PDFPaulina Sobarzo VegaNo ratings yet

- Ejercicio y Cancer - Phys Ther Res. Vol. 26, 10-16Document7 pagesEjercicio y Cancer - Phys Ther Res. Vol. 26, 10-16Carlos Fabian Amigo MendozaNo ratings yet

- Mur-Gimeno Et Al 2021Document16 pagesMur-Gimeno Et Al 2021Thiago SartiNo ratings yet

- Fu 2017Document3 pagesFu 2017Jessica CampoNo ratings yet

- Health Behaviors of Lung Cancer SurvivorsDocument8 pagesHealth Behaviors of Lung Cancer SurvivorsShawnya MichaelsNo ratings yet

- 520 2020 Article 5834Document14 pages520 2020 Article 5834Chloe BujuoirNo ratings yet

- Strength and Endurance Training in The Treatment of Lung Cancer Patients in Stages IIIA-IIIB-IVDocument7 pagesStrength and Endurance Training in The Treatment of Lung Cancer Patients in Stages IIIA-IIIB-IVFRANCISCO JAVIER TABILO SAEZNo ratings yet

- Lifestyle and Integrative Oncology Interventions for Cancer-related Fatigue and Sleep DisturbancesDocument7 pagesLifestyle and Integrative Oncology Interventions for Cancer-related Fatigue and Sleep DisturbanceszhuyyinNo ratings yet

- review breast cancer 3Document11 pagesreview breast cancer 3Karen MejiaNo ratings yet

- Document PDFDocument7 pagesDocument PDFPricess PoppyNo ratings yet

- Psycho-Oncology - 2017 - Ormel - Predictors of adherence to exercise interventions during and after cancer treatment ADocument12 pagesPsycho-Oncology - 2017 - Ormel - Predictors of adherence to exercise interventions during and after cancer treatment APaulo JorgeNo ratings yet

- Associations-between-health-related-fitness-and-patien_2024_Journal-of-SportDocument12 pagesAssociations-between-health-related-fitness-and-patien_2024_Journal-of-SportSujasree NavaneethanNo ratings yet

- Ada 2017Document11 pagesAda 2017IvanCarrilloNo ratings yet

- Artigo 3 2023.1Document12 pagesArtigo 3 2023.1Andréia MoraisNo ratings yet

- Physical Activity and Cancer Risk. Actual Knowledge and Possible Biological MechanismsDocument11 pagesPhysical Activity and Cancer Risk. Actual Knowledge and Possible Biological MechanismsTiara SafitriNo ratings yet

- Blank Et Al - IJYT PDFDocument9 pagesBlank Et Al - IJYT PDFFrancisca González SalvatierraNo ratings yet

- Artigo 10Document9 pagesArtigo 10Átrio Reabilitação CardiopulmonarNo ratings yet

- Exercise CancerDocument10 pagesExercise CancermustakNo ratings yet

- 2019 Article 1090Document12 pages2019 Article 1090YairCañizaresNo ratings yet

- Multidisciplinary Exercise Based Oncology Rehabilitation Prog - 2021 - JournalDocument15 pagesMultidisciplinary Exercise Based Oncology Rehabilitation Prog - 2021 - JournalAbner HenriqueNo ratings yet

- Cancer PrehabitationDocument13 pagesCancer PrehabitationAna Carolina Soares EstevesNo ratings yet

- The Journal of Physiology - 2023 - Clifford - Exercise Snacks A Recipe For Health in Cancer PopulationsDocument2 pagesThe Journal of Physiology - 2023 - Clifford - Exercise Snacks A Recipe For Health in Cancer PopulationsVinícius Humberto Morales PinoNo ratings yet

- Hayes 2020Document9 pagesHayes 2020Manuel OvelarNo ratings yet

- Ovarian CancerDocument17 pagesOvarian CancerVinitha DsouzaNo ratings yet

- s10549 015 3652 4Document9 pagess10549 015 3652 4Utami DewiNo ratings yet

- Resistance Exercise Dosage in Men With Prostate CancerDocument60 pagesResistance Exercise Dosage in Men With Prostate Cancersilvio da costa guerreiroNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 11 05487Document10 pagesIjerph 11 05487Pauline OctavianiNo ratings yet

- Role of Physiotherapy For Oncology and Surgery NewDocument30 pagesRole of Physiotherapy For Oncology and Surgery NewelbazhagerNo ratings yet

- EBP Practice 1 - N - Supervised Group Exercise Programme For Breast Ca Survivor - 2016Document7 pagesEBP Practice 1 - N - Supervised Group Exercise Programme For Breast Ca Survivor - 2016elieser toding mendilaNo ratings yet

- Ensayo controlado aleatorio que prueba la viabilidad de una intervención de ejercicio y nutrición para pacientes con cáncer de ovario durante y después de la quimioterapia de primera línea (estudio BENITA)Document11 pagesEnsayo controlado aleatorio que prueba la viabilidad de una intervención de ejercicio y nutrición para pacientes con cáncer de ovario durante y después de la quimioterapia de primera línea (estudio BENITA)joelccmmNo ratings yet

- Lung CaDocument20 pagesLung Cadr.soppalNo ratings yet

- Does Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Regimen Affect SarcoDocument7 pagesDoes Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Regimen Affect SarcoNova SuryatiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2347562521004133 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2347562521004133 MainUtami DewiNo ratings yet

- 2018 - Breast and Ovarian Cancer - BMC Cancer - BauersfeldDocument10 pages2018 - Breast and Ovarian Cancer - BMC Cancer - BauersfeldHouda BouachaNo ratings yet

- Pilates For Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument6 pagesPilates For Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysismelisberilyNo ratings yet

- Wenzel 2005Document8 pagesWenzel 2005cikox21848No ratings yet

- 2018 Article 1051Document10 pages2018 Article 1051Vukašin Schooly StojanovićNo ratings yet