Lynn Hilditch

Liverpool Hope University, Art and Design, Faculty Member

- History, Photography Theory, History of photography, Art History, Visual Culture, Documentary (Film Studies), and 19 moreFilm History, Surrealism, Vogue, Cultural History, Popular Culture, Documentary Photography, Photography and War, Social and Collective Memory, Lee Miller, Documentary Film, Second World War, History and Theory of Photography, War Photography, Photojournalism, Audrey Hepburn, Cultural Studies, Gender Studies, Gender, and English Literatureedit

- Dr. Lynn Hilditch is a lecturer in art and design history at Liverpool Hope University, UK. Lynn has lectured on vari... moreDr. Lynn Hilditch is a lecturer in art and design history at Liverpool Hope University, UK. Lynn has lectured on various aspects of the visual arts, predominantly American film and photography; her research interests include the interpretation of war in art and photography and the socio-historical representation of gender in twentieth-century popular culture. Her doctoral research focused on the World War Two photography of the American Surrealist and war photographer Lee Miller.

Member of the Desmond Tutu Research Centre for War and Peace Studies at Liverpool Hope University.edit

Lee Miller (1907-1977) was an American-born Surrealist and war photographer who, through her role as a model for Vogue magazine, became the apprentice of Man Ray in Paris and later one of the few women war correspondents to cover the... more

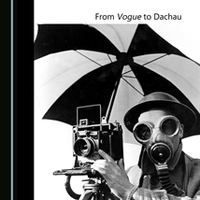

Lee Miller (1907-1977) was an American-born Surrealist and war photographer who, through her role as a model for Vogue magazine, became the apprentice of Man Ray in Paris and later one of the few women war correspondents to cover the Second World War from the frontline. Her comprehensive understanding of art enabled her to photograph vivid representations of Europe at war—the changing gender roles of women in war work, the destruction caused by enemy fire during the London Blitz, the horrors of the concentration camps—that embraced and adapted the principles and methods of Surrealism. This monograph examines how Miller’s war photographs can be interpreted as ‘surreal documentary’ combining a surrealist sensibility with a need to inform. Each chapter contains a close analysis of specific photographs in a generally chronological study with a thematic focus, using comparisons with other photographers, documentary artists, and Surrealists, such as Margaret Bourke-White, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, George Rodger, Cecil Beaton, Bill Brandt, Henry Moore, Humphrey Jennings and Man Ray. In addition, Miller’s photographs are explored through André Breton’s theory of ‘convulsive beauty’—his credence that any subject, no matter how horrible, may be interpreted as art—and his notion of the ‘marvellous’.

Research Interests: Photography, Surrealism, Photojournalism, Second World War, Second World War (History), and 7 moreLee Miller, War correspondents, social and cultural history of the Second World War, Relationship of Aesthetics and War, World War 2 empire War Correspondents/Women, History of the Second World War and the Holocaust, and Modern Memory

On 8 May 1945 American war photographer, Lee Miller, sent a telegraph to the editor of Vogue magazine, Audrey Withers, along with a collection of negatives that she had taken at the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau, demanding... more

On 8 May 1945 American war photographer, Lee Miller, sent a telegraph to the editor of Vogue magazine, Audrey Withers, along with a collection of negatives that she had taken at the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau, demanding “I IMPLORE YOU TO BELIEVE THIS IS TRUE!” Through these photographs she also appealed to Vogue’s readers, particularly in the United States, to be aware of, if not totally comprehend, the atrocities that had been committed by the Nazis. Her photographs, she hoped, would act as visual evidence by placing the readers directly in view of those horrors in an attempt to provoke as well as inform. In this paper I will explore how Miller, once the muse and apprentice of the Surrealist artist Man Ray, approached the Holocaust in order to visualise the inconceivable. By using her ‘surrealist eye’ she was able to create aesthetic and historical interpretations of one of the most horrific periods in human history. Miller’s images not only have great worth as historical documents, they also give expression to testimony, experience and memory of the Holocaust. In addition, I will consider the work of theorists and writers such as John Berger, Susan Sontag and Walter Lippman and their views regarding the visual representation of the Holocaust in order to explore how photographers, like Miller, were able to use their medium and artistic skills to effectively reconstruct the horror as a form of ‘modern memorial’ for future generations.

Research Interests:

On 8 May 1945 American war photographer, Lee Miller, sent a telegraph to the editor of Vogue magazine, Audrey Withers, along with a collection of negatives that she had taken at the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau, demanding... more

On 8 May 1945 American war photographer, Lee Miller, sent a telegraph to the editor of Vogue magazine, Audrey Withers, along with a collection of negatives that she had taken at the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau, demanding “I IMPLORE YOU TO BELIEVE THIS IS TRUE!” Through these photographs she also appealed to Vogue’s readers, particularly in the United States, to be aware of, if not totally comprehend, the atrocities that had been committed by the Nazis. Her photographs, she hoped, would act as visual evidence by placing the readers directly in view of those horrors in an attempt to provoke as well as inform. In this paper I will explore how Miller, once the muse and apprentice of the Surrealist artist Man Ray, approached the Holocaust in order to visualise the inconceivable. By using her ‘surrealist eye’ she was able to create aesthetic representations of one of the most horrific periods in human history. Miller’s images not only have great worth as historical documents, they also give expression to testimony, experience and memory of the Holocaust. In addition, I will consider the work of theorists and writers such as John Berger, Susan Sontag and Walter Lippman and their views regarding the visual representation of the Holocaust in order to explore how photographers, like Miller, were able to use their artistic skills to effectively frame the horror as a form of ‘modern memorial’ for future generations.

Research Interests: Photography, History and Memory, Cultural Memory, Second World War, Holocaust Studies, and 3 moreCultural Memory (especially in Relation to Cinema And/or Photography), Cinema/cultural Experience and Psychoanalytic Theory, Film History; Photography and Cultural Memory, Lee Miller, and Memorialisation

George Orwell in his essay “A Nice Cup of Tea”, published in the London Evening Standard in January 1946, described tea as “one of the main stays of civilization in this country”, and this belief was confirmed by the British documentary... more

George Orwell in his essay “A Nice Cup of Tea”, published in the London Evening Standard in January 1946, described tea as “one of the main stays of civilization in this country”, and this belief was confirmed by the British documentary filmmakers who produced many short films during the 1930s and 1940 depicting the act of tea drinking as a significant part of British culture. In the wartime films of Humphrey Jennings, for example, the cup of tea symbolizes the mythology of the ‘spirit of the Blitz’ by strengthening the concept of citizenship and bringing the community closer together during a time of chaos and uncertainty. Anthony Aldgate and Jeffrey Richards, in their 2007 book Britain Can Take It: British Cinema in the Second World War, recall a scene from Jennings’ 1943 masterpiece Fires Were Started when, after the team of firemen finish putting out a raging fire at the London docks, which has seen one of their colleagues tragically killed, “A mobile canteen arrives with the ‘nice cup of tea’, that distinctively British symbol of normality”. This particular scene signifies the importance of the ‘cup of tea’ in times of crisis (both personal and national) and emphasises the fact that tea consumption has always been a central part of daily life in Britain. Consequently, tea culture has become synonymous with British national identity.

This chapter will provide a contextual analysis of the depiction of tea culture within the British documentary film from a socio-historical and cultural perspective establishing how tea drinking crossed boundaries of class and gender; taking ‘afternoon tea’ was no longer a leisure activity strictly reserved for the upper classes but a necessity for the working classes for whom the much need ‘tea break’ provided an opportunity for relaxation from the everyday toil of the factory, farm, coal mine and steel mill. Tea also played a vital role during the war, comforting families whose homes had been destroyed by enemy bombs and weary citizens emerging from long nights in inner-city air-raid shelters. Films such as Ruby Grierson’s Today We Live (1937) and They Also Serve (1940), Harry Watt’s North Sea (1938), Jack Lee and J B Holmes’ Ordinary People (1941) and Humphrey Jennings’ Spare Time (1939), Heart of Britain (1941), Fires Were Started (1943) and The Silent Village (1943) all comment on the cultural significance of tea as part of the British national experience while reinforcing the concept of British wartime community spirit. As the 20th century philosopher Bernard-Paul Heroux once claimed, “There is no trouble so great or grave that cannot be much diminished by a nice cup of tea”.

This chapter will provide a contextual analysis of the depiction of tea culture within the British documentary film from a socio-historical and cultural perspective establishing how tea drinking crossed boundaries of class and gender; taking ‘afternoon tea’ was no longer a leisure activity strictly reserved for the upper classes but a necessity for the working classes for whom the much need ‘tea break’ provided an opportunity for relaxation from the everyday toil of the factory, farm, coal mine and steel mill. Tea also played a vital role during the war, comforting families whose homes had been destroyed by enemy bombs and weary citizens emerging from long nights in inner-city air-raid shelters. Films such as Ruby Grierson’s Today We Live (1937) and They Also Serve (1940), Harry Watt’s North Sea (1938), Jack Lee and J B Holmes’ Ordinary People (1941) and Humphrey Jennings’ Spare Time (1939), Heart of Britain (1941), Fires Were Started (1943) and The Silent Village (1943) all comment on the cultural significance of tea as part of the British national experience while reinforcing the concept of British wartime community spirit. As the 20th century philosopher Bernard-Paul Heroux once claimed, “There is no trouble so great or grave that cannot be much diminished by a nice cup of tea”.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Lee Miller’s photographs of the London Blitz, including the twenty-two published in Ernestine Carter’s Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (1941), effectively demonstrate what Susan Sontag described as “a beauty in ruins”. As a... more

Lee Miller’s photographs of the London Blitz, including the twenty-two published in Ernestine Carter’s Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (1941), effectively demonstrate what Susan Sontag described as “a beauty in ruins”. As a former student and muse of Man Ray during the 1930s and a close associate of the Surrealists in Paris, Miller was able to utilize her knowledge of Surrealism, and other art forms, to create an aestheticized reportage of a broken city ravished by war. In Miller’s case, her war photographs may be deemed aesthetically significant by considering her Surrealist background and by analyzing her images within the context of André Breton’s theory of “convulsive beauty”—his idea that a scene of destruction can be represented or analyzed as something beautiful by convulsing, or transforming, it into its apparent opposite. Miller’s war photographs, therefore, not only depict the chaos and destruction of Britain during the Blitz, they also reveal Surrealism’s love for quirky or evocative juxtapositions while creating an artistic visual representation of a temporary surreal world of fallen statues and broken typewriters. As Leo Mellor writes about these dualities, “The paradox of Miller’s wartime reportage was announced in the title of her book of documentary photographs, Grim Glory; that is to say, the coexistence of darkening mortality and ideal exaltation, like a Baroque conceit”.

Research Interests:

During the Second World War, the world’s press faced the difficult task of recording the horrific scenes of conflict, death and destruction they had witnessed across Europe. Often these scenes were so incredulous that many reporters found... more

During the Second World War, the world’s press faced the difficult task of recording the horrific scenes of conflict, death and destruction they had witnessed across Europe. Often these scenes were so incredulous that many reporters found it impossible to articulate what they had seen into words and turned to photographers to translate the horrors into visual images. The war photograph, therefore, took on the crucial role not only of historical document, but also as a means to inform, provoke, shock and remind. In this essay, I will discuss how the American Surrealist and war correspondent Lee Miller recorded horrors of the Second World War, and the concentration camps at Dachau and Buchenwald, in particular. Through the Surrealist practice of ‘fragmentation’ she was able to use her knowledge of art to break down, or ‘fragment’, scenes of death and destruction into smaller, digestible chunks for the readers of Vogue magazine on both sides of the Atlantic. As hybrids of art and historical documentation, Miller’s concentration camp photographs become ‘modern memorials’ to the victims of war and the Holocaust.

Research Interests: Surrealism, Memory Studies, Modernity (Memory Studies), Second World War, Holocaust Studies, and 5 moreCultural Memory (especially in Relation to Cinema And/or Photography), Cinema/cultural Experience and Psychoanalytic Theory, Film History; Photography and Cultural Memory, Lee Miller, Memorialisation, War Photography, and Photography and Memory

On 8 May 1945 American war photographer, Lee Miller, sent a telegraph to the editor of Vogue magazine, Audrey Withers, along with a collection of negatives that she had taken at the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau, demanding... more

On 8 May 1945 American war photographer, Lee Miller, sent a telegraph to the editor of Vogue magazine, Audrey Withers, along with a collection of negatives that she had taken at the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau, demanding “I IMPLORE YOU TO BELIEVE THIS IS TRUE!” Through these photographs she also appealed to Vogue’s readers, particularly in the United States, to be aware of, if not totally comprehend, the atrocities that had been committed by the Nazis. Her photographs, she hoped, would act as visual evidence by placing the readers directly in view of those horrors in an attempt to provoke as well as inform.

In this paper I will explore how Miller, once the muse and apprentice of the Surrealist artist Man Ray, approached the Holocaust in order to visualise the inconceivable. By using her ‘surrealist eye’ she was able to create aesthetic representations of one of the most horrific periods in human history. Miller’s images not only have great worth as historical documents, they also give expression to testimony, experience and memory of the Holocaust. In addition, I will consider the work of theorists and writers such as John Berger, Susan Sontag and Walter Lippman and their views regarding the visual representation of the Holocaust in order to explore how photographers, like Miller, were able to use their artistic skills to effectively frame the horror as a form of ‘modern memorial’ for future generations.

In this paper I will explore how Miller, once the muse and apprentice of the Surrealist artist Man Ray, approached the Holocaust in order to visualise the inconceivable. By using her ‘surrealist eye’ she was able to create aesthetic representations of one of the most horrific periods in human history. Miller’s images not only have great worth as historical documents, they also give expression to testimony, experience and memory of the Holocaust. In addition, I will consider the work of theorists and writers such as John Berger, Susan Sontag and Walter Lippman and their views regarding the visual representation of the Holocaust in order to explore how photographers, like Miller, were able to use their artistic skills to effectively frame the horror as a form of ‘modern memorial’ for future generations.

Research Interests:

Lee Miller’s photographs of the London Blitz, including the twenty-two published in Ernestine Carter’s Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (1941), effectively demonstrate what Susan Sontag described as “a beauty in ruins”. As a... more

Lee Miller’s photographs of the London Blitz, including the twenty-two published in Ernestine Carter’s Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (1941), effectively demonstrate what Susan Sontag described as “a beauty in ruins”. As a former student and muse of Man Ray during the 1930s and a close associate of the Surrealists in Paris, Miller was able to utilize her knowledge of Surrealism, and other art forms, to create an aestheticized reportage of a broken city ravished by war. In Miller’s case, her war photographs may be deemed aesthetically significant by considering her Surrealist background and by analyzing her images within the context of André Breton’s theory of “convulsive beauty”—his idea that a scene of destruction can be represented or analyzed as something beautiful by convulsing, or transforming, it into its apparent opposite. Miller’s war photographs, therefore, not only depict the chaos and destruction of Britain during the Blitz, they also reveal Surrealism’s love for quirky or evocative juxtapositions while creating an artistic visual representation of a temporary surreal world of fallen statues and broken typewriters. As Leo Mellor writes about these dualities, “The paradox of Miller’s wartime reportage was announced in the title of her book of documentary photographs, Grim Glory; that is to say, the coexistence of darkening mortality and ideal exaltation, like a Baroque conceit”.

Research Interests:

In his post-war essay “A Nice Cup of Tea” (1946), George Orwell described tea as “one of the main stays of civilization in this country” and suggested that tea had the ability to provide some kind of empowering national energy as well as... more

In his post-war essay “A Nice Cup of Tea” (1946), George Orwell described tea as “one of the main stays of civilization in this country” and suggested that tea had the ability to provide some kind of empowering national energy as well as having a very precise preparation and social purpose. During wartime, tea became a tool of perseverance in order to affirm British cultural identity during a period when it was very much under attack. While the process or ‘art’ of tea drinking as well as tea’s social history has been discussed many times, the cultural significance of that most traditionally British of hot beverages has habitually been taken for granted throughout film and visual culture. However, in numerous British documentary films of the 1930s and 1940s, the importance of tea drinking in British culture appears to have been magnified as an essential social pastime, particularly relevant in times of crisis and hardship.

This paper will offer a contextual analysis of the depiction of tea culture within the British documentary film from a socio-historical and cultural perspective; taking ‘afternoon tea’ was no longer a leisure activity strictly reserved for the upper classes but a necessity for the working classes for whom the much need ‘tea break’ provided an opportunity for relaxation from the everyday toil of the factory, farm, coal mine and steel mill. Tea also played a vital role during the war, comforting families whose homes had been destroyed by enemy bombs and weary citizens emerging from long nights in inner-city air-raid shelters, thus reinforcing the somewhat propagandist concept of British wartime community spirit.

This paper will offer a contextual analysis of the depiction of tea culture within the British documentary film from a socio-historical and cultural perspective; taking ‘afternoon tea’ was no longer a leisure activity strictly reserved for the upper classes but a necessity for the working classes for whom the much need ‘tea break’ provided an opportunity for relaxation from the everyday toil of the factory, farm, coal mine and steel mill. Tea also played a vital role during the war, comforting families whose homes had been destroyed by enemy bombs and weary citizens emerging from long nights in inner-city air-raid shelters, thus reinforcing the somewhat propagandist concept of British wartime community spirit.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

In his essay "First Principles of Documentary" (1932), the British filmmaker and social critic John Grierson argues that the principles of documentary are that cinema's potential for observing life can be exploited in a new art form; that... more

In his essay "First Principles of Documentary" (1932), the British filmmaker and social critic John Grierson argues that the principles of documentary are that cinema's potential for observing life can be exploited in a new art form; that the ‘original’ actor and ‘original’ scene are better guides than their fictional counterparts to interpreting the modern world. In other words, the realist nature of the documentary film is able to depict the actuality of a nation’s identity and culture more explicitly than the false representations of the movies.

This paper will examine how British national identity, or ‘Britishness’, has been depicted in the work of key twentieth-century British documentary filmmakers from the pre-war period to the early 1960s. With particular focus on the work of John Grierson, Humphrey Jennings and John Schlesinger, I will explore how filmmakers portrayed class, race and social crisis in Britain, particularly during Second World War and post-war period. In addition, I will consider Grierson's definition of documentary as "creative treatment of actuality", a belief which has gained general acceptance from film critics but presents philosophical questions about documentaries containing fictional elements, such as Schlesinger’s 1961 film Terminus.

This paper will examine how British national identity, or ‘Britishness’, has been depicted in the work of key twentieth-century British documentary filmmakers from the pre-war period to the early 1960s. With particular focus on the work of John Grierson, Humphrey Jennings and John Schlesinger, I will explore how filmmakers portrayed class, race and social crisis in Britain, particularly during Second World War and post-war period. In addition, I will consider Grierson's definition of documentary as "creative treatment of actuality", a belief which has gained general acceptance from film critics but presents philosophical questions about documentaries containing fictional elements, such as Schlesinger’s 1961 film Terminus.

Research Interests:

Michel Hazanavicius’ 2011 silent masterpiece The Artist not only pays homage to the Silent Era of Hollywood cinema, it also provides a complex commentary on key themes such as of loss, despair, love and death. While the character of... more

Michel Hazanavicius’ 2011 silent masterpiece The Artist not only pays homage to the Silent Era of Hollywood cinema, it also provides a complex commentary on key themes such as of loss, despair, love and death. While the character of George Valentin may be stereotypical of the 1920s matinee idol, he also symbolises the decline of an era as his career is sabotaged by the onset of new sound technology and the growing popularity of the “Talkie”. George fears that the birth of sound will inevitably result in the death of art—“I am an Artist!”

This paper aims to contextualise The Artist in relation to the key themes as well as analysing Hazanavicius’ incorporation of American cinematic references, not only his references to the classic silent films of Douglas Fairbanks and John Gilbert but also to the work of Alfred Hitchcock (Vertigo) and Orson Welles (Citizen Kane), and the art house cinematic style of Twentieth Century European filmmaking.

This paper aims to contextualise The Artist in relation to the key themes as well as analysing Hazanavicius’ incorporation of American cinematic references, not only his references to the classic silent films of Douglas Fairbanks and John Gilbert but also to the work of Alfred Hitchcock (Vertigo) and Orson Welles (Citizen Kane), and the art house cinematic style of Twentieth Century European filmmaking.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

As the former muse of the Dada-Surrealist Man Ray, the American-born photographer Lee Miller’s work contains an in depth knowledge of Surrealist practices, in particular her use of the method of fragmentation as both a compositional tool... more

As the former muse of the Dada-Surrealist Man Ray, the American-born photographer Lee Miller’s work contains an in depth knowledge of Surrealist practices, in particular her use of the method of fragmentation as both a compositional tool and as a mechanism for artistic control. Working within an essentially misogynist artistic circle proved invaluable in her later role as a war photographer for Vogue magazine capturing the horrors of the Second World War. As Linda Nochlin writes that “the human body is not just the object of desire, but the site of suffering, pain and death”.

This paper explores Miller’s photographic representations of the body, firstly, through her collaboration with Man Ray, secondly, in her role as a Surrealist photographer, and, thirdly, as a war correspondent photographing the victims of conflict. Drawing upon the work of theorists such as Susan Sontag, Julia Kristeva, John Berger and André Breton, I will argue that Miller’s experience as a Surrealist muse provided her with the foresight to photograph the bodies she came across on the battlefields of Europe and, in particular, at the concentration camps of Dachau and Buchenwald. Sontag explains, “It seems that the appetite for pictures showing bodies in pain is as keen, almost, as the desire for ones that show bodies naked”.

This paper explores Miller’s photographic representations of the body, firstly, through her collaboration with Man Ray, secondly, in her role as a Surrealist photographer, and, thirdly, as a war correspondent photographing the victims of conflict. Drawing upon the work of theorists such as Susan Sontag, Julia Kristeva, John Berger and André Breton, I will argue that Miller’s experience as a Surrealist muse provided her with the foresight to photograph the bodies she came across on the battlefields of Europe and, in particular, at the concentration camps of Dachau and Buchenwald. Sontag explains, “It seems that the appetite for pictures showing bodies in pain is as keen, almost, as the desire for ones that show bodies naked”.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Susan Sontag in her 2003 book Regarding the Pain of Others suggests that images of war and destruction can be interpreted as aesthetic objects--that there is “a beauty in ruins”. A landscape of war is still a landscape. A painting... more

Susan Sontag in her 2003 book Regarding the Pain of Others suggests that images of war and destruction can be interpreted as aesthetic objects--that there is “a beauty in ruins”. A landscape of war is still a landscape. A painting depicting war is still a piece of art. Lee Miller’s photographs taken during the latter years of World War Two demonstrate this argument--that images of war can be justified as being aesthetic artefacts through the photographer’s creative use composition and form and by considering the image within the context of the Surrealist Andre Breton’s theory of “convulsive beauty”, his idea that anything can be deemed beautiful even the most disturbing or horrific of subjects. A scene of death and destruction can, therefore, be transformed into something beautiful, something aesthetic by convulsing it into its apparent opposite.

This paper will discuss how Miller’s war photographs can be interpreted as aesthetic by analysing how Miller uses her knowledge of art--through the creative use of composition and form and the application of Bretonian Surrealism--and by arguing that a war photograph often involves a hybrid-aesthetic, justified by its interpretation as a combination of art and historical documentation. Miller’s photographs taken at the Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps, therefore, not only inform and act as crucial documentary evidence that the holocaust existed, they also show scenes photographed with a great sensitivity, a need to inform, technical excellence and the presence of a “surrealist eye”.

This paper will discuss how Miller’s war photographs can be interpreted as aesthetic by analysing how Miller uses her knowledge of art--through the creative use of composition and form and the application of Bretonian Surrealism--and by arguing that a war photograph often involves a hybrid-aesthetic, justified by its interpretation as a combination of art and historical documentation. Miller’s photographs taken at the Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps, therefore, not only inform and act as crucial documentary evidence that the holocaust existed, they also show scenes photographed with a great sensitivity, a need to inform, technical excellence and the presence of a “surrealist eye”.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests: Visual Studies, Art History, Art, Photography, Surrealism, and 11 morePhotojournalism, Second World War, Multidisciplinary, Lee Miller, Miller, War correspondents, social and cultural history of the Second World War, Relationship of Aesthetics and War, History of the Second World War and the Holocaust, Modern Memory, and Second World War History

EThOS - Electronic Theses Online ServiceGBUnited Kingdo

During the Second World War, the world's press faced the difficult task of recording the horrific scenes of conflict, death and destruction they had witnessed across Europe. Often these scenes were so incredible that many reporters... more

During the Second World War, the world's press faced the difficult task of recording the horrific scenes of conflict, death and destruction they had witnessed across Europe. Often these scenes were so incredible that many reporters found it impossible to articulate what they had seen into words and turned to photographers to translate the horrors into visual images. The war photograph, therefore, took on the crucial role not only of historical document, but also as a means to inform, provoke, shock and remind. This article discusses how the American Surrealist and war correspondent Lee Miller recorded horrors of the Second World War, and the concentration camps at Dachau and Buchenwald, in particular. Through the Surrealist practice of ‘fragmentation’ she was able to use her knowledge of art to break down, or ‘fragment’, scenes of death and destruction into smaller, digestible chunks for the readers of Vogue magazine on both sides of the Atlantic. As hybrids of art and historica...

Research Interests:

Lee Miller (1907-1977) was an American-born Surrealist and war photographer who, through her role as a model for Vogue magazine, became the apprentice of Man Ray in Paris and later one of the few women war correspondents to cover the... more

Lee Miller (1907-1977) was an American-born Surrealist and war photographer who, through her role as a model for Vogue magazine, became the apprentice of Man Ray in Paris and later one of the few women war correspondents to cover the Second World War from the frontline. Her comprehensive understanding of art enabled her to photograph vivid representations of Europe at war—the changing gender roles of women in war work, the destruction caused by enemy fire during the London Blitz, the horrors of the concentration camps—that embraced and adapted the principles and methods of Surrealism. This monograph examines how Miller’s war photographs can be interpreted as ‘surreal documentary’ combining a surrealist sensibility with a need to inform. Each chapter contains a close analysis of specific photographs in a generally chronological study with a thematic focus, using comparisons with other photographers, documentary artists, and Surrealists, such as Margaret Bourke-White, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, George Rodger, Cecil Beaton, Bill Brandt, Henry Moore, Humphrey Jennings and Man Ray. In addition, Miller’s photographs are explored through André Breton’s theory of ‘convulsive beauty’—his credence that any subject, no matter how horrible, may be interpreted as art—and his notion of the ‘marvellous’.