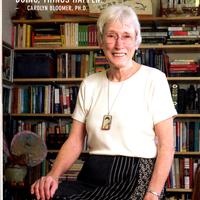

- I am a cultural anthropologist specializing in modern China, and my fieldwork there (1988-2011) has concentrated prim... moreI am a cultural anthropologist specializing in modern China, and my fieldwork there (1988-2011) has concentrated primarily on contemporary art and cinema. In addition to anthropological perspectives, my thinking is informed by earlier research and writing in the field of visual perception and by decades of prior experience in the teaching and practice of art. I’m currently working on a 3-part series of reference guides to Chinese film.

I am Professor Emeritus retired from Ringling College of Art and Design where for 23 years I taught anthropology in the Liberal Arts Program and coordinated the Cross-cultural Perspectives curriculum. I earned my PhD in from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1992 after a 20-year career as an active exhibiting artist/professor and author of PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL PERCEPTION (1976, revised edition 1989). From 2007-2017 I was also Director for the official Sister City relationship between Sarasota, Florida and Xiamen, China.edit - Dissertation Advisor: Judith B Farquhar, PhD. University of Chicagoedit

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Interestingly, woodcut prints resonate with traditional Chinese painting. They are executed primarily in black and white, and on paper. They resemble the rubbings of famous paintings and calligraphies, in which black and white are often... more

Interestingly, woodcut prints resonate with traditional Chinese painting. They are executed primarily in black and white, and on paper. They resemble the rubbings of famous paintings and calligraphies, in which black and white are often reversed. In the process of creation, the cut of the knife into the wood is as economical, expedient, simple and direct as is the brush on the paper--like the mark of the brush, the cut of the knife cannot be erased: once executed it must be accepted, else the work must be discarded and begun anew. For centuries, woodcuts have been used in China for illustrating books, journals and painting manuals, for vernacular New Year's pictures, for visual journalism and, in the late 19th century, for disseminating anti-Christian and anti-foreign propaganda. Nonetheless, in the late 1920s and early 30s woodcut prints became the central axis for a radical restructuring of artistic institutions, practices, and audiences in China.

Research Interests:

Western understandings of the trajectory of Chinese art following Mao’s death in 1976 have been hampered by several factors. A persistent element is the propensity of Western art historians and critics to impose Western historical... more

Western understandings of the trajectory of Chinese art following Mao’s death in

1976 have been hampered by several factors. A persistent element is the propensity of Western art historians and critics to impose Western historical patterns, esthetic standards and critical methods to the analysis of Chinese art, its production and expression. This tendency was exacerbated by China’s closing to the West after 1949, which discouraged scholarship and Chinese language study and resulted in a 30-year hiatus in scholarly communications and firsthand knowledge—a situation that invited imagination and speculation that favored an obsessive preference in the West for art that could be interpreted as politically subversive. When China re-opened in the 1980s, scholars of contemporary Chinese art faced the further problem of trying to make sense of an anarchic disarray of theories and practices rushing in to fill the vacuum afforded by the collapse of Marxism-Leninism-Mao-Zedong ideology. The prolific but scattered writings and publications by Chinese artists, critics and theorists were accessible only to those few who already possessed a high level of Chinese language facility including the specially nuanced vocabulary of the art world, as well as a wide-ranging and balanced network of interpersonal contacts. This volume addresses the need for wider access to primary Chinese sources by readers of English.

1976 have been hampered by several factors. A persistent element is the propensity of Western art historians and critics to impose Western historical patterns, esthetic standards and critical methods to the analysis of Chinese art, its production and expression. This tendency was exacerbated by China’s closing to the West after 1949, which discouraged scholarship and Chinese language study and resulted in a 30-year hiatus in scholarly communications and firsthand knowledge—a situation that invited imagination and speculation that favored an obsessive preference in the West for art that could be interpreted as politically subversive. When China re-opened in the 1980s, scholars of contemporary Chinese art faced the further problem of trying to make sense of an anarchic disarray of theories and practices rushing in to fill the vacuum afforded by the collapse of Marxism-Leninism-Mao-Zedong ideology. The prolific but scattered writings and publications by Chinese artists, critics and theorists were accessible only to those few who already possessed a high level of Chinese language facility including the specially nuanced vocabulary of the art world, as well as a wide-ranging and balanced network of interpersonal contacts. This volume addresses the need for wider access to primary Chinese sources by readers of English.

Research Interests:

Combining psychology, art theory and cross-cultural studies, this book explores ways in which our minds construct meaning from visual information. It discusses how the mind attributes meaning to things and events, the structure and... more

Combining psychology, art theory and cross-cultural studies, this book explores ways in which our minds construct meaning from visual information. It discusses how the mind attributes meaning to things and events, the structure and functioning of eye and brain, how we perceive color, space, depth and distance, motion, the development and mechanics of photography and how the camera affects our definition of reality and the way we think about the world, the incursion of electronic and mass-communication media, and finally, making and looking at works of art with greater awareness.

First edition published in 1976: NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold / Prentice Hall, 1976-86 (six printings). Translation of first edition published in 1987 by Beijing University Press as Shijue Yuanli视觉原理,Zhang Gongqian 张功 钱, translator, author name transliterated as Kaluolin M Bulumo 卡鲁琳 M 布鲁墨 (print run: 28,500).

\

First edition published in 1976: NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold / Prentice Hall, 1976-86 (six printings). Translation of first edition published in 1987 by Beijing University Press as Shijue Yuanli视觉原理,Zhang Gongqian 张功 钱, translator, author name transliterated as Kaluolin M Bulumo 卡鲁琳 M 布鲁墨 (print run: 28,500).

\

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Since the mid-1980s, when vital, new Fifth Generation films from the PRC began to attract international attention, the field of Chinese film studies has steadily matured, transforming from a potpourri of discrete academic treatments into... more

Since the mid-1980s, when vital, new Fifth Generation films from the PRC began to attract international attention, the field of Chinese film studies has steadily matured, transforming from a potpourri of discrete academic treatments into an arena of analysis that is increasingly inclusive and co-mingled with broad issues of social theory. From the first, Chris Berry has been a leader in this gestation process, and his collaboration here with Mary Farquhar has produced an important and exceedingly satisfying read. In the interests of creating a larger and more productive analytic framework appropriate to our age of transnational cinema, these two scholars--aptly enough--begin with proposing a rectification of names: the abandonment of conventional categories.

Research Interests:

Western understandings of the trajectory of Chinese art following Mao’s death in 1976 have been hampered by several factors. A persistent element is the propensity of Western art historians and critics to impose Western historical... more

Western understandings of the trajectory of Chinese art following Mao’s death in

1976 have been hampered by several factors. A persistent element is the propensity of Western art historians and critics to impose Western historical patterns, esthetic standards, and critical methods to the analysis of Chinese art, its production and expression. This tendency was exacerbated by China’s closing to the West after 1949, which discouraged scholarship and Chinese language study and resulted in a 30-year hiatus in scholarly communications and firsthand knowledge, and at the same time invited imagination and speculation favoring an obsessive preference in the West for art that could be interpreted as politically subversive. When China opened in the 1980s, scholars of contemporary Chinese art faced the further problem of trying to make sense of an anarchic disarray of theories and practices rushing in to fill the vacuum afforded by the collapse of Marxism-Leninism-Mao-Zedong ideology. The

prolific but scattered writings and publications by Chinese artists, critics and

theorists were accessible only to those few who already possessed a high level of

Chinese language facility including the specially nuanced vocabulary of the art

world, as well as a wide-ranging and balanced network of personal contacts. This collection addresses the need for wider access to these Chinese sources by readers of

English.

1976 have been hampered by several factors. A persistent element is the propensity of Western art historians and critics to impose Western historical patterns, esthetic standards, and critical methods to the analysis of Chinese art, its production and expression. This tendency was exacerbated by China’s closing to the West after 1949, which discouraged scholarship and Chinese language study and resulted in a 30-year hiatus in scholarly communications and firsthand knowledge, and at the same time invited imagination and speculation favoring an obsessive preference in the West for art that could be interpreted as politically subversive. When China opened in the 1980s, scholars of contemporary Chinese art faced the further problem of trying to make sense of an anarchic disarray of theories and practices rushing in to fill the vacuum afforded by the collapse of Marxism-Leninism-Mao-Zedong ideology. The

prolific but scattered writings and publications by Chinese artists, critics and

theorists were accessible only to those few who already possessed a high level of

Chinese language facility including the specially nuanced vocabulary of the art

world, as well as a wide-ranging and balanced network of personal contacts. This collection addresses the need for wider access to these Chinese sources by readers of

English.

Research Interests:

contemporary china ;chinese studies; china review; CUHK; Chinese University Press;modern china;sociology, literature ;arts;business;economics;geography; history;domestic politics; international affairs;

Research Interests:

Recalling the Chinese traditional saying 桃李漫天下 táolǐ màn tiānxià– “a teacher’s students – his peaches and plums -- fill the whole world” Professor Ju’s former students remembered him in special programs at the Millennium Gate Museum... more

Recalling the Chinese traditional saying 桃李漫天下 táolǐ màn tiānxià– “a teacher’s students – his peaches and plums -- fill the whole world” Professor Ju’s former students remembered him in special programs at the Millennium Gate Museum (Atlanta GA) during a memorial exhibition of his paintings. This essay was the third of three presentations. Turner McGee, Chair of the Art Department at Hastings College (Nebraska) first gave personal reminiscences of his long-term relationship with Professor Ju as mentor, friend, and fellow artist. Then Mike Kopald, a dedicated painter of bamboo, gave a painting demonstration while relating his personal experiences with Professor Ju.

Research Interests: Visual perception, Teachers' And Students' Interpersonal Relationships, Kinesthetic teaching, Chinese Calligraphy, Kinesthetic learning, and 8 moreChinese Art - Calligraphy & Ink Painting, Student-Teacher Relationships, Embodied knowledge, Educational Methodology, Chinese Calligraphy Its Transmission, Chinese in America, Chinese Traditional Ink Painting, and Traditional Chinese Ink Painting

Recalling the Chinese traditional saying 桃李漫天下 táolǐ màn tiānxià– “a teacher’s students – his peaches and plums -- fill the whole world” Professor Ju I-Hsiung ’s former students remembered him in special programs at the Millennium Gate... more

Recalling the Chinese traditional saying 桃李漫天下 táolǐ màn tiānxià– “a teacher’s students – his peaches and plums -- fill the whole world” Professor Ju I-Hsiung ’s former students remembered him in special programs at the Millennium Gate Museum (Atlanta GA) during a memorial exhibition of his paintings. This essay was the third of three presentations. Turner McGee, Chair of the Art Department at Hastings College (Nebraska) first gave personal reminiscences of his long-term relationship with Professor Ju as mentor, friend, and fellow artist. Then Mike Kopald, a dedicated painter of bamboo, gave a painting demonstration while relating his personal experiences with Professor Ju.

Research Interests:

Principles of effective information design are often assumed to be universal. An ethnographic perspective, however, shows us that every culture cultivates certain distinctive perceptual modalities. Following a model of communication that... more

Principles of effective information design are often assumed to be universal. An ethnographic perspective, however, shows us that every culture cultivates certain distinctive perceptual modalities. Following a model of communication that defines viewers as active decoders (rather than passive recipients), and using China and Japan as case studies, this paper examines some culturally specific modalities involved in the perception of visual information. These are: directionality in scanning visual information; significant differences between phonetic and ideographic writing; mixed coding; kinesthetic empathy; reading unmarked space; interpreting size and position on the image plane in various perspectives; construing facial expressions and eye contact; and curious relations between sign and referent. When working across cultures, designers who strive to understand the culturally directed perceptual habits and predispositions of their target audiences and match their approaches accordingly can capitalize on intriguing new possibilities for graphic communication. (minor updates added 3/2020)

Research Interests: Asian Studies, Visual Studies, Perception, Visual Anthropology, Chinese Studies, and 11 moreVisual perception, Cross-Cultural Studies, Visual Communication, Information Design, Culture and Cognition, Cross-Cultural Communication, Communication & Graphic Design, Infographics, Graphic communications, Communication models, and Infographics Journalism Advertising Graphic Design

Written from the perspective of a cultural anthropologist, this paper explores differences in traditional Chinese and Western cultural concepts, values, and practices regarding 'copying' and their implications for the social practice and... more

Written from the perspective of a cultural anthropologist, this paper explores differences in traditional Chinese and Western cultural concepts, values, and practices regarding 'copying' and their implications for the social practice and economic circulation of artistic productions and other 'intellectual properties' in a globalizing world. While Chinese models of 'copying' nourish the accretion of history, genealogies of practice, and open access, Western models favor the displacement of history through concepts of 'originality', and the management of creative work as an analog of material property ownership. Implications for the regulation of 'intellectual property' in the global market place are considered.

Research Interests:

In this recent book, New York art critic Barbara Pollack focuses on the elite art scene in the golden triangle of Beijing-Shanghai-New York. Pollack generally bypasses 'art-speak' jargon, preferring to explain the artists' works in terms... more

In this recent book, New York art critic Barbara Pollack focuses on the elite art scene in the golden triangle of Beijing-Shanghai-New York. Pollack generally bypasses 'art-speak' jargon, preferring to explain the artists' works in terms of the singularity of their individual experiences within the particular globalized time and space in which they work. US-China Review is the quarterly journal of the national US-China Peoples Friendship Association.

Most highly recommended: YouTube: "Barbara Pollack: Brand New Art From China", a 50- minute slide-lecture in which the author talks about her book and her experiences with the artists, followed by 30 minutes of Q&A afterward. Presented at Asia Society (NYC) December 3, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JJa70cyo3tc

Most highly recommended: YouTube: "Barbara Pollack: Brand New Art From China", a 50- minute slide-lecture in which the author talks about her book and her experiences with the artists, followed by 30 minutes of Q&A afterward. Presented at Asia Society (NYC) December 3, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JJa70cyo3tc