International Journal of Obesity (2007) 31, 1731–1738

& 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0307-0565/07 $30.00

www.nature.com/ijo

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Defined weight expectations in overweight women:

anthropometrical, psychological and eating behavioral

correlates

V Provencher1, C Bégin2, M-P Gagnon-Girouard2, HC Gagnon1, A Tremblay3, S Boivin4 and

S Lemieux1

1

Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Institute of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods, Laval University, Québec,

Canada; 2School of Psychology, Laval University, Québec, Canada; 3Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Division

of Kinesiology, Laval University, Québec, Canada and 4Eating Disorders Treatment Program, CHUL, CHUQ, Laval

University, Québec, Canada

Objective: To examine associations between defined weight expectations and anthropometric profile and to identify

psychological and eating behavioral factors that characterize women having more realistic weight expectations.

Methods: A nonrandom sample of 154 overweight/obese women completed the ‘Goals and Relative Weight Questionnaire’,

which assessed four weight expectations: (1) dream weight (whatever wanted to weight); (2) happy weight (would be happy to

achieve); (3) acceptable weight (could accept even if not happy with it); and (4) disappointed weight (would not view as a

successful achievement). Psychological assessments evaluated dysphoria, self-esteem, satisfaction with one’s body (i.e., body

esteem) and weight-related quality of life. The ‘Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire’ assessed eating behaviors: (1) cognitive

dietary restraint (control of food intake), (2) disinhibition (overconsumption of food with a loss of control), and (3) susceptibility

to hunger (food intake in response to feelings and perceptions of hunger).

Results: Women’s expectations for their dream (60.676.0 kg), happy (65.276.4 kg) and acceptable (67.976.8 kg) weights

corresponded to higher percentages of weight loss (24.276.6% or 19.877.1 kg, 18.675.8% or 15.276.0 kg and 15.275.7%

or 12.675.8 kg, respectively) than goals recommended for overweight individuals. Defined weight expectations were positively

associated with current weight and body mass index (BMI; 0.37prp0.85; Po0.0001). When women were matched one by one

for their current BMI, but showing different happy BMI, women with a more realistic happy BMI were older (P ¼ 0.03) and were

characterized by a greater satisfaction towards body weight (P ¼ 0.04), a higher score for flexible restraint (P ¼ 0.003) and a

lower score for susceptibility to hunger (P ¼ 0.02) than women with a less realistic happy BMI.

Conclusion: These findings suggest that having more realistic weight expectations is related to healthier psychological and

eating behavioral characteristics.

International Journal of Obesity (2007) 31, 1731–1738; doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803656; published online 5 June 2007

Keywords: weight status; psychological profile; eating behaviors; treatment goals

Introduction

There is no doubt that the prevalence of obesity is increasing

in industrialized countries,1,2 and efforts have been engaged

to raise awareness among the general population about the

importance of having a healthy weight. In a culture that

emphasizes thinness and weight control, preoccupation about

Correspondence: Dr S Lemieux, Institute of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods,

Laval University, 2440, Hochelaga Blvd., Québec, Québec G1K 7P4, Canada.

E-mail: Simone.Lemieux@aln.ulaval.ca

Received 14 October 2006; revised 11 March 2007; accepted 10 April 2007;

published online 5 June 2007

weight may be related to dissatisfaction with one’s body

weight and shape as well as an overconcern about reaching

an ideal weight.3 This is particularly observed in women

compared to men who appear to be much more comfortable

with their weight.4 A study performed in Canadian women

having a body mass index (BMI) within acceptable limits

(acceptable BMI defined as being between 20 and 24 kg/m2 for

the purpose of that study), showed that the proportion of

those who desire to lose weight was quite elevated with 35%

considering themselves above their desired weight.5

A considerable discrepancy exists between recommended

weight loss goals (5–10% of initial weight6) and patient’s

expectations (average of 30% of initial weight7) among

�Factors related to weight expectations

V Provencher et al

1732

overweight and obese individuals. Previous studies have

shown that measured BMI was positively related to higher

weight expectations as defined in absolute weight or in BMI

units.7–9 Moreover, measured weight has been identified as

a strong determinant of dream, happy, acceptable and

disappointed weights.10 Individuals having a higher weight

status are thus more likely to choose higher weights in

kilograms to define their weight expectations.7–10

In addition to unmodifiable factors such as age and sex,9,10

other modifiable factors have been suggested to explain the

determinants of patient’s expectations. Psychological characteristics such as higher level of dysphoria,10 lower selfesteem7 and poorer satisfaction with body image7 have been

found to be related to more stringent weight expectations. As

underlined by Foster et al.,10,11 data concerning modifiable

factors related to body weight expectations are still scarce,

and this issue is central for the development of interventions

that aimed at modifying patient’s expectations. Among

those potential modifiable factors, we may consider the

contribution of eating behaviors in the determination of

patient’s expectations because eating behaviors are closely

related to psychological characteristics, such as well-being,12

and they are also significantly associated with weight

status.13–16 Given that both psychological characteristics

and weight status are related to weight expectations, it could

therefore be suggested that eating behaviors may be involved

as significant determinants of weight expectations.

Even if moderate weight losses of 5–10% of initial weight

are recommended for overweight and obese individuals who

are attempting to lose weight,6 controversy is still observed

in the literature regarding the possible consequences of

having greater weight loss expectations or in other words,

expecting a higher percentage of body weight loss. Some

authors reported that subjects who expected a highest

percentage of body weight loss were those who lost the

most significant body weight without being psychologically

distressed,17,18 suggesting that less realistic weight loss goals

are not hampering efforts to lose weight, and may rather

increase motivation to lose weight. On the opposite, other

studies have shown that individuals who expressed more

important weight-loss expectations were experiencing a

higher attrition rate during a weight-loss program, suggesting that not being able to reach defined weight-loss

goals may create dissatisfaction regarding weight-loss

attempts.9,19,20 Teixeira et al.20 reported a curvilinear relationship between weight expectations and weight changes.

More precisely, having either too high weight-loss expectations or too low weight-loss expectations were related to a

lower percentage of body weight loss. On the other hand,

previous pilot studies aiming at changing weight-loss

expectations were generally effective in producing more

realistic weight-loss expectations at the end of the intervention, without however enhancing weight-loss maintenance.11,21 Inconsistent results reported in the literature

therefore stress the relevance to understand better factors

related to patient’s weight expectations.

International Journal of Obesity

Considering the meaningful impact of obesity, psychological distress and eating behaviors on health status together

with the discrepancy observed between recommended

weight-loss goals and patient’s expectations, it appears of

relevance to understand better the associations between

weight status, weight expectations, psychological profile and

eating behaviors. The primary objective of this study was to

examine associations between defined weight expectations

and anthropometric profile in a sample of premenopausal

overweight and obese women studied at baseline of a

research intervention on weight management. In addition,

this study proposed to identify psychological and eating

behavioral factors that characterize women having more

realistic BMI expectations defined in terms of happy BMI.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study was conducted among a nonrandom sample of

154 premenopausal women (mean age of 42.475.6 years). In

response to advertisement through different media in the

Quebec City metropolitan area (for example, newspapers

and Internet), women voluntarily accepted to participate in

the research project. All women included in this study were

overweight or obese (BMI between 25 and 35 kg/m2), had a

stable weight for at least 2 months (72.5 kg), were not

currently dieting, were not pregnant or lactating and were

not presenting chronic diseases or taking medication that

could impact on measurements performed. Women were

also characterized by a preoccupation with their weight and

eating.22 Before their participation to the study, each woman

signed an informed consent document which was approved

by the Laval University Research Ethics Committee.

Study design

Women who participated in this study were recruited during

four equal phases of testing and intervention (September 2003,

January 2004, September 2004 and January 2005). A total of

194 women were met for a screening interview and 154 of

them accepted to take part in the study and were tested at

baseline. This paper presents results obtained at baseline and

does not report results from the intervention part of the study.

Women were tested during the follicular phase of their

menstrual cycle to control for the potential impact of

hormonal variation on nutritional and psychological variables. However, some women were exceptionally tested at

another moment of their cycle mainly because they had an

irregular cycle (N ¼ 4). When these women were excluded

from the present analyses, similar results were observed.

Measurements of dependent variables

Defined weight expectations. A French version of the Goals

and Relative Weights Questionnaire (part II)7 was used to

�Factors related to weight expectations

V Provencher et al

1733

identify four different categories of weight expectations: (1)

dream weight (‘A weight you would choose if you could

weight whatever you wanted’); (2) happy weight (‘This

weight is not as ideal as the first one. However, it is a weight

that you would be happy to achieve’); (3) acceptable weight

(‘A weight that you would not be particularly happy with,

but one you could accept since it is less than your current

weight’; and (4) disappointed weight (‘A weight that is less

than you are at your current weight, but one that you would

not view as successful in any way. You would be disappointed

if this were your final weight after the program’). All women

involved in the study (except one woman who did not

answer this questionnaire; N ¼ 153) identified their four

weight expectations (in pounds or in kilograms) and these

absolute weight values were used in the analyses. In

addition, weight expectations were also transformed into

BMI units to permit adequate comparison between women

from different statures. Expected weight loss and percentages

of weight loss that would be required to reach the four

defined weight expectations were also calculated according

to initial body weight for each woman.

Anthropometrical profile. Height, body weight and BMI were

determined according to standardized procedures, as recommended at the Airlie Conference.23 Briefly, height was

measured to the nearest millimeter with a stadiometer, and

body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg on a

calibrated balance. Participants were asked to dress lightly

and to remove their shoes for these measurements.

Diet and weight history. Data regarding previous attempts to

lose weight and changes in weight status were collected

through a general questionnaire on diet and weight history.

In this study, two questions on diet history and two

questions on weight history were of particular interest.

Women had to indicate at which age they first attempted to

lose weight. They also had to indicate the number of times

they previously experienced dieting (from 0 to 5 times).

Finally, they had to recall their highest and lowest weight

ever during adult life (excluding weight reached during

pregnancies for the highest weight).

Psychological variables. Different validated questionnaires

were administrated to assess psychological variables. Dysphoria was evaluated by the Beck Depression Inventory

during the screening interview.24 Weight-related quality of

life was measured by the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life

Questionnaire (IWQOL-Lite),25 according to five dimensions

of quality of life (Physical Function, Self-Esteem, Sexual Life,

Public Distress, and Work). Self-esteem (general, social and

personal) was assessed with the Culture-Free Self-esteem

Inventories.26 Body esteem (appearance, weight and attribution) were measured by the Body-Esteem Scale.27

Eating behaviors. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire is a

51-item validated questionnaire,28–30 which assesses three

factors that refer to cognitions and behaviors associated with

eating: cognitive dietary restraint (conscious control of food

intake with concerns about shape and weight), disinhibition

(overconsumption of food in response to a variety of stimuli

associated with a loss of control on food intake), susceptibility to hunger (food intake in response to feelings and

perceptions of hunger). More specific subscales can also

be derived from these three general eating behaviors:31,32

rigid restraint (dichotomous, all-or-nothing approach to

eating, dieting and weight), flexible restraint (gradual

approach to eating, dieting and weight), habitual susceptibility to disinhibition (behaviors that may occur

when circumstances predispose to recurrent disinhibition),

emotional susceptibility to disinhibition (disinhibition associated with negative affective states), situational susceptibility to disinhibition (disinhibition initiated by specific

environmental cues), internal hunger (hunger interpreted

and regulated internally) and external hunger (triggered by

external cues).

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s correlation analyses were performed to quantify

the univariate relationships between defined weight expectations (in kilograms and in BMI units), anthropometric

profile (current weight and BMI) and age. As Foster et al.7

have previously shown that happy weight was the body

weight expectation that was the most closely associated with

weight-loss goal, further analyses were conducted with

happy weight expectations. To allow adequate comparison

between women from different statures,10 further analyses

assessing differences in psychological variables and eating

behaviors were performed with current BMI and happy

weight expectation expressed in BMI units (referred to as

happy BMI). In the two groups of women formed on the

basis of their current BMI (BMI above or below the median

value of 30.4 kg/m2), coefficients of correlation observed for

the relationship between current BMI and happy BMI were

computed and then compared using MedCalc statistical

software (version 8.2.1.0).

Women were also matched one by one for their current

BMI (70.95 kg/m2, which refers to the stable weight

inclusion criteria (72.5 kg) for the mean height in our

sample (1.6270.05 m)). Each pair was formed so that a

noticeable difference in their value of happy BMI was

observed (number of pairs formed was N ¼ 57; 39 women

were not included in the analysis because it was not possible

to match them for these specifications). More specifically,

each pair showed a difference of at least 1.73 kg/m2 for their

happy BMI, which corresponds to the standard deviation

(s.d.) for the mean happy BMI value. This matching

procedure also resulted in similar values for weight and

height when the two groups were compared. For the purpose

of these analyses, women with a more realistic happy BMI

were determined as follows. For a given current BMI, women

who defined their happy BMI as being closer to their current

International Journal of Obesity

�Factors related to weight expectations

V Provencher et al

1734

BMI were considered as having a more realistic happy BMI

than women who defined their happy BMI as being further

from their current BMI (less realistic happy BMI). Psychological variables and eating behaviors were compared between

these two groups of women by performing a Student’s

unpaired t-test analysis. For variables not normally distributed, a log-transformation was performed. The probability

level for significance used for the interpretation of all

statistical analyses was set at an a-level of Po0.05. All

analyses were performed by using SAS statistical software

(SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Women from this study had a mean body weight of

80.579.6 kg (BMI: 30.573.0 kg/m2). Their perception of

their dream, happy, acceptable and disappointed weights

are presented in Table 1. An average woman would have to

lose 18.675.8% of her initial weight to reach her happy

weight expectation. This value is higher than current

recommendations for weight loss (5–10% of initial weight).

An average weight loss of 7.875.5% would have been

considered as a disappointed result in this sample.

Table 2 shows correlations between defined weight

expectations and anthropometric profile. Current weight

and current BMI were both positively related to dream,

happy, acceptable and disappointed weights expressed in

kilograms or in BMI units. Age was positively associated

with dream weight, dream BMI and happy BMI, and these

relationships remained significant after adjustment for

weight or BMI. As explained in the Materials and methods

section, relationship between current BMI and happy BMI

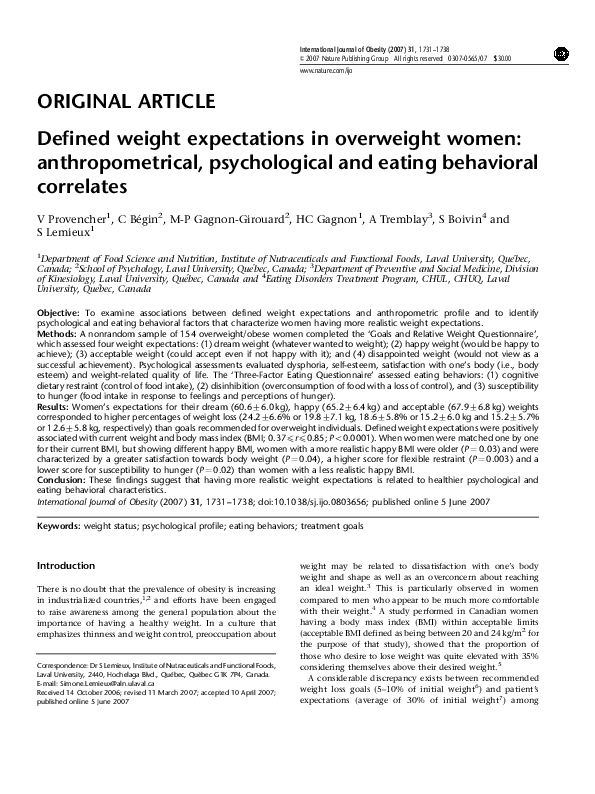

was further examined. As illustrated in Figure 1, the

correlation observed between current BMI and happy BMI

was stronger in women having a BMI below the median

value (p30.4 kg/m2; Figure 1a) than to those with a BMI

above the median (430.4 kg/m2; Figure 1b) (r ¼ 0.63,

Po0.0001 and r ¼ 0.27, P ¼ 0.02, respectively, with a z

statistic ¼ 4.0232; P ¼ 0.0001). Similar differences between

groups formed on the basis of their current BMI were also

observed for relationships between current BMI and dream

BMI, acceptable BMI and disappointed BMI (data not

shown).

Table 1

Further analyses were performed in women matched one

by one for their current BMI, but presenting a significantly

different happy BMI, as described in the Materials and

methods section. As expected, Table 3 shows no difference

for weight and BMI between women having either a lower

(less realistic) happy BMI or a higher (more realistic) happy

BMI. Moreover, the percentage of weight loss from initial

body weight that would be required to reach happy weight

(percentage of weight loss) was greater in women with a less

realistic happy BMI than in women with a more realistic

happy BMI. Women with a less realistic happy BMI were also

younger than women having a more realistic happy BMI.

However, no significant differences were observed with

regard to diet and weight history between these two groups.

More specifically, women with a less realistic happy BMI

were comparable to those with a more realistic happy BMI

regarding the age at which they first attempted to lose

weight (23.778.2 years vs 23.277.7 years, respectively;

P ¼ 0.77) as well as the number of times they experienced

dieting (3.272.0 vs 3.471.7, respectively; P ¼ 0.59). Women

from these two groups also reported similar highest and

lowest weight during adult life (82.778.4 and 56.376.9 kg

for women with a less realistic happy BMI vs 85.079.7 and

Table 2 Pearson correlation coefficients for the association of defined weight

expectations with body weight, BMI and age (N ¼ 153)

Weight (kg)

BMI (kg/m2)

Age (years)

0.67***

0.78***

0.80***

0.85***

0.39***

0.59***

0.58***

0.63***

0.37***

0.48***

0.53***

0.68***

0.49***

0.67***

0.71***

0.80***

0.16*a

0.13

0.09

0.11

0.23**b

0.19*b

0.13

0.14

Dream weight

Happy weight

Acceptable weight

Disappointed weight

Dream BMI

Happy BMI

Acceptable BMI

Disappointed BMI

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index. Significant correlation: *Po0.05;

**Po0.01; ***Po0.0001. aRemained significant after adjustment for weight.

b

Remained significant after adjustment for BMI. Dream weight: ‘A weight you

would choose if you could weight whatever you wanted’; happy weight: ‘This

weight is not as ideal as the first one. However, it is a weight that you would

be happy to achieve’; acceptable weight: ‘A weight that you would not be

particularly happy with, but one you could accept since it is less than your

current weight’; and disappointed weight: ‘A weight that is less than you are

at your current weight, but one that you would not view as successful in any

way. You would be disappointed if this were your final weight after the

program’.

Defined weight expectations in overweight and obese women (N ¼ 153)

Dream weight

Happy weight

Acceptable weight

Disappointed weight

Weight (kg)

BMI (kg/m2)

Expected weight loss (kg)

Difference from current weight (%)

60.676.0

65.276.4

67.976.8

74.078.5

23.071.7

24.771.7

25.771.9

28.072.8

19.877.1

15.276.0

12.675.8

6.475.0

24.276.6

18.675.8

15.275.7

7.875.5

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; s.d., standard deviation. Data are means7s.d. Dream weight: ‘A weight you would choose if you could weight whatever you

wanted’; happy weight: ‘This weight is not as ideal as the first one. However, it is a weight that you would be happy to achieve’; acceptable weight: ‘A weight that

you would not be particularly happy with, but one you could accept since it is less than your current weight’; and disappointed weight: ‘A weight that is less than you

are at your current weight, but one that you would not view as successful in any way. You would be disappointed if this were your final weight after the program’.

International Journal of Obesity

�Factors related to weight expectations

V Provencher et al

1735

Table 4 Differences in variables of the psychological profile between women

with either lower or higher happy BMI

a

32

r=0.63

p <0.0001

30

28

26

24

22

20

18

24

b 32

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

Higher happy BMI

(N ¼ 57)

P-value

10.277.0

72.5713.5

11.973.2

6.471.5

4.672.2

1.270.6

0.770.5

1.870.6

9.277.4

76.3712.2

11.873.5

6.771.1

4.872.6

1.470.6

0.970.6

1.870.5

0.48

0.12

0.88

0.27

0.67

0.23

0.04a

0.65

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; s.d., standard deviation. Data are

means7s.d. aDifference observed between the two groups remained

significant after adjustment for age (P ¼ 0.03). BDI ¼ dysphoria (Beck Depression Inventory); total IWQOL ¼ weight-related quality of life (Impact of Weight

on Quality of Life-Lite); BES – appearance, weight and attribution ¼ body

esteem (Body-Esteem Scale).

r=0.27

p =0.02

30

BDI

Total IWQOL

General self-esteem

Social self-esteem

Personal self-esteem

BES – appearance

BES – weight

BES – attribution

Lower happy BMI

(N ¼ 57)

28

26

24

22

Table 5 Differences in eating behaviors between women with either lower or

higher happy BMI (N ¼ 114)

20

18

30

31

32

33

34

Current BMI

35

36

37

Figure 1 Pearson correlation between current BMI (kg/m2) and happy BMI

(kg/m2) in women below the median value of BMI (a: p30.4 kg/m2) and in

women above the median value of BMI (b: 430.4 kg/m2); z statistic ¼ 4.0232;

P ¼ 0.0001. Happy BMI refers to the happy weight expectation (in BMI units),

which is corresponding to the following definition: ‘This weight is not as ideal

as the first one. However, it is a weight that you would be happy to achieve’.

Table 3 Differences in age, body weight, BMI and weight loss needed to

achieve happy weight between women with either lower or higher happy BMI

Age (years)

Weight (kg)

BMI (kg/m2)

Happy weight loss (%)

Lower happy BMI

(N ¼ 57)

Higher happy BMI

(N ¼ 57)

P-value

Cognitive restraint

Flexible restraint

Rigid restraint

8.574.3

2.471.6

2.771.9

9.473.6

3.371.4

2.871.6

0.25

0.003a

0.75

Disinhibition

Habitual

Emotional

Situational

9.873.0

2.371.6

2.371.0

3.571.3

9.272.9

2.171.4

2.071.2

3.371.5

0.31

0.43

0.19

0.38

Hunger

Internal

External

6.373.8

2.472.2

2.971.8

4.773.0

1.771.7

2.271.4

0.02

0.06

0.02

38

(kg/m2)

Lower happy BMI

(N ¼ 57)

Higher happy BMI

(N ¼ 57)

P-value

41.275.8

80.279.2

30.673.0

22.175.1

43.575.2

82.179.0

30.872.9

15.475.0

0.03

0.28

0.71

0.0001

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; s.d., standard deviation. Data are

means7s.d. Women from the lower happy BMI group had a mean happy BMI

of 23.771.4 kg/m2, whereas women from the higher happy BMI group had a

mean happy BMI of 26.071.5 kg/m2 (Po0.0001).

58.877.6 kg for women with a more realistic happy BMI;

P ¼ 0.17 and P ¼ 0.07, respectively).

As observed in Table 4, no significant differences were

observed with regard to psychological variables between

women presenting either a lower or a higher happy BMI,

except for the body image dimension. Women with a more

realistic happy BMI showed a greater satisfaction with their

weight compared to those having a less realistic happy BMI.

Differences observed in eating behaviors between women

with less realistic and more realistic happy BMI are presented

in Table 5. Women with a more realistic happy BMI were

characterized by a higher score for flexible restraint while

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; s.d., standard deviation. Data are

means7s.d. aDifferences observed between the two groups remained

significant after adjustment for age (Po0.05), except for external hunger

(P ¼ 0.07).

they displayed a lower level of susceptibility to hunger

(particularly for the external hunger subscale). Because age

was significantly different between women with a lower vs

those with a higher happy BMI, adjustment for age was also

performed. Significant differences were still observed for

satisfaction with their weight (P ¼ 0.03), flexible restraint

(P ¼ 0.003) and susceptibility to hunger (P ¼ 0.03), whereas

the difference noted for external hunger was no longer

significant (P ¼ 0.07).

Discussion

The main objectives of this study were to examine associations between defined weight expectations and anthropometric profile as well as to identify psychological and eating

behavioral factors that characterize women having a more

International Journal of Obesity

�Factors related to weight expectations

V Provencher et al

1736

realistic definition of what would be a happy BMI. As

previously reported,7,8,10 women with higher weight and

BMI were likely to choose higher defined weight expectations. In this present study, 57 pairs of women having a

similar current BMI, but showing significantly different

happy BMI expectations were formed. Women with a more

realistic happy BMI were older and were characterized by

a greater satisfaction towards their body weight together

with a higher score for flexible restraint and a lower score for

susceptibility to hunger. These findings suggest that, in

addition to unmodifiable factors such as age and sex,9,10

modifiable factors such as body image and eating behaviors

are also related to weight expectations.

Defined values for dream, happy and acceptable weights

reported by women from this study represented higher

weight-loss goals than current recommendations (5–10% of

initial weight).6 The values corresponding to actual recommendations were rather considered as disappointing results

for women in the present sample. This discrepancy between

women’s definitions and health definitions of successful

weight loss has been observed previously in other studies.7–10

Socio-cultural context and norms in which women are

living, such as value of thinness, may contribute to explain

the important deviation between current recommendations

and defined expectations in terms of weight loss.33,34 In this

study, percentages of weight loss needed to achieve each

defined weight were lower than those observed previously

in other samples.7,10,11 Considering that defined weight

expectations are positively related to BMI, as observed in the

present and previous studies,7,8,10 this difference could be

explained by a relatively lower BMI observed in our sample

(mean BMI of 30.573.0 kg/m2 in this study vs 36.374.3

kg/m2 in the study of Foster et al.7). As previously demonstrated,10 age was also positively related to weight expectations, where older women were showing more realistic

values for happy BMI. However, after adjustment for the

confounding effect of age, similar results were observed

suggesting that differences noted for body weight satisfaction, flexible restraint and susceptibility to hunger between

women with different happy BMI expectation could not be

explained solely by differences in age. Finally, in accordance

with previous studies,10 the amount of initial weight to lose

to reach defined weight expectations (percentage of weight

loss) were also positively related to weight and BMI (data

not shown), which could mean that even if heavier women

choose higher absolute weights, they would still have to lose

higher amount of weight to reach their expected body

weight.

It has been previously shown that more positive selfesteem and body image as well as lower weight phobia and

dysphoria were associated with more realistic defined

weights, when adjusted for BMI.7,8,10 In line with these

results, women with a more realistic happy BMI were

characterized by a greater satisfaction towards their weight,

whereas no other differences were noted for psychological

variables. This is suggesting that body image is a consistent

International Journal of Obesity

psychological factor closely related to women’s definition

of their happy weight. Although we know that, in general,

body image dissatisfaction is highly prevalent among overweight and obese individuals,34,35 the present results showed

that, among our overweight and obese samples, there is a

specific group of women who, independent of their BMI, are

more dissatisfied with their weight and present higher

expectations towards weight loss. In accordance with results

from Teixeira et al.,19 these women would be more likely

to experience unsuccessful weight-loss attempts. In fact,

Teixeira et al.19 showed that a lower body cathexis (i.e., more

negative feelings towards one’s body) and a less realistic

happy weight were both predictors of poorer success in

weight loss on a long-term basis. It is therefore of relevance

to understand better why for a given current BMI, some

women are more susceptible to be less satisfied by their

weight and to have less realistic weight expectations. One

possible explanation may be that these women associate

negatively weight and happiness.36 In that sense, the

influence of body dissatisfaction on weight-loss attempt

could be related to unrealistic expected changes in body

image. If we referred to Stice’s model, we may suppose that

those who are less satisfied with their body and present

less realistic expectations are at higher risk to adopt nonnormative eating behaviors to lose their excess weight.37 In

fact, this study has demonstrated a significant negative

relationship between satisfaction towards weight and susceptibility to hunger (r ¼ �0.20; P ¼ 0.0002). Accordingly,

prior studies have shown that body dissatisfaction was

related to overeating.37,38

Few studies have examined the relationships between

eating behaviors and weight expectations, except for the

severity of binge-eating for which no association was

observed.8,9 In this study, higher score for flexible restraint

together with lower score for susceptibility to hunger were

observed in women having a more realistic happy BMI.

Successful weight maintenance, which implies that initial

weight loss is subsequently kept for at least several months,

has been previously related to higher levels of flexible

restraint and lower scores for susceptibility to hunger.39–42

This would suggest that having more realistic weight

expectations is associated with some eating behaviors related

to more successful weight-loss maintenance. This is in line

with the work of Westenhoefer,43 who has previously

suggested that long-term success in weight maintenance

would be enhanced by helping individuals to give up their

less realistic expectations about weight loss together with

focusing on behavioral changes under the principle of

flexible control. In addition, findings from this study suggest

that weight expectations and eating behaviors could be

related to each other. In this regard, our results may also

provide some explanations for the greater attrition rate

observed during weight-loss programs in individuals with

higher expectations as well as for their lower percentage

of body weight loss achieved.9,19,20 In fact, for those overweight and obese women who have less realistic weight

�Factors related to weight expectations

V Provencher et al

1737

expectations, it could be suggested that lower level of flexible

restraint as well as higher score of susceptibility to hunger

may act as barriers that counteract efforts to lose weight or

maintain weight loss achieved. In fact, being able to manage

food intake with a more graduated and sustainable approach

together with being less triggered by feelings of hunger

may help to develop a better relationship with food. Thus,

women with more realistic weight expectations could be

more successful in their attempts to maintain their weight

loss, because they also display more favorable eating

patterns. However, the cross-sectional nature of this study

has to be considered and at this point, it remains to be

established whether eating behaviors are causally involved

in relationships observed with weight expectations. In

addition, because women involved in this study were not

randomly selected, they may not be representative of all

overweight and obese women. Accordingly, potential bias

such as a higher socio-economical status, which is often

observed among research volunteers, may have influenced

results obtained.

Conclusion

In a sample of premenopausal overweight and obese women

preoccupied with their weight, more realistic weight expectations were related to less body weight dissatisfaction as

well as to higher level of flexible restraint and lower score for

susceptibility to hunger. According to the previous literature,

these characteristics would be related to more successful

weight-loss attempts.19,40 Clinical pilot studies that mainly

aimed to promote more modest weight-loss expectations

have been conducted previously.11,21 These interventions

were effective in producing more realistic expectations while

they did not facilitate a better long-term weight-loss

maintenance. It might be suggested that to be successful,

interventions focusing on more modest weight losses should

also include components aiming at improving body image

and eating behaviors. Other factors, such as flexible eating

and hunger, also seem to be of relevance in the understanding of women’s definitions of weight expectations,

as preoccupation about food seems to be closely related

to preoccupation about weight, and these psychological

and eating behavioral correlates of weight expectations

appear to be relevant clinical targets in weight management

interventions.

Acknowledgements

This research project was supported by the Canadian

Institutes of Health Research (MOP-64226) and Danone

Institute. VP is recipient of a studentship from the Fonds de la

recherche en santé du Québec. AT is partly funded by the

Canada Research Chair in Physical Activity, Nutrition, and

Energy Balance. We would like to underline the excellent

work of all research professionals that were involved in this

study (Geneviève Alain, Louise Corneau, Julie Doyon and

Natacha Godbout) as well as the research nurses (Danielle

Aubin and Claire Julien). The authors would like to express

their gratitude to the subjects for their participation in this

study.

References

1 Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and

trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 2002; 288:

1723–1727.

2 Tjepkema M, Shields M. Nutrition: Findings from Canadian

Community Health Survey – Adult Obesity in Canada. Measured

Height and Weight, Statistics Canada: Ottawa, 2005.

3 Pelletier LG, Dion S, Levesque C. Can self-determination help

protect women against sociocultural influences about body image

and reduce their risk of experiencing bulimic symptoms? J Soc and

Clin Psychol 2004; 23: 61–88.

4 Crawford D, Campbell K. Lay definitions of ideal weight and

overweight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1999; 23: 738–745.

5 Green KL, Cameron R, Polivy J, Cooper K, Liu L, Leiter L et al.

Weight dissatisfaction and weight loss attempts among Canadian

adults. Canadian Heart Health Surveys Research Group. CMAJ

1997; 157 (Suppl 1): S17–S25.

6 National Institutes of Health. The Practical Guide: Identification,

Evaluation and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults.

National Institutes of Health: Bethesda MD, 2000.

7 Foster GD, Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Brewer G. What is a reasonable

weight loss? Patients’ expectations and evaluations of obesity

treatment outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65: 79–85.

8 Dalle GR, Calugi S, Magri F, Cuzzolaro M, Dall’Aglio E, Lucchin L

et al. Weight loss expectations in obese patients seeking treatment

at medical centers. Obes Res 2004; 12: 2005–2012.

9 Dalle GR, Calugi S, Molinari E, Petroni ML, Bondi M, Compare A

et al. Weight loss expectations in obese patients and treatment

attrition: an observational multicenter study. Obes Res 2005; 13:

1961–1969.

10 Foster GD, Wadden TA, Phelan S, Sarwer DB, Sanderson RS. Obese

patients’ perceptions of treatment outcomes and the factors that

influence them. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 2133–2139.

11 Foster GD, Phelan S, Wadden TA, Gill D, Ermold J, Didie E.

Promoting more modest weight losses: a pilot study. Obes Res

2004; 12: 1271–1277.

12 Provencher V, Begin C, Piche ME, Bergeron J, Corneau L,

Weisnagel SJ et al. Disinhibition, as assessed by the Three-Factor

Eating Questionnaire, is inversely related to psychological

well-being in postmenopausal women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;

31: 315–320.

13 Hays NP, Bathalon GP, McCrory MA, Roubenoff R, Lipman R,

Roberts SB. Eating behavior correlates of adult weight gain and

obesity in healthy women aged 55–65 y. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 75:

476–483.

14 Lawson OJ, Williamson DA, Champagne CM, DeLany JP, Brooks

ER, Howat PM et al. The association of body weight, dietary

intake, and energy expenditure with dietary restraint and

disinhibition. Obes Res 1995; 3: 153–161.

15 Provencher V, Drapeau V, Tremblay A, Despres JP, Lemieux S.

Eating behaviors and indexes of body composition in men

and women from the Québec Family Study. Obesity Res 2003; 11:

783–792.

16 Williamson DA, Lawson OJ, Brooks ER, Wozniak PJ, Ryan DH,

Bray GA et al. Association of body mass with dietary restraint and

disinhibition. Appetite 1995; 25: 31–41.

International Journal of Obesity

�Factors related to weight expectations

V Provencher et al

1738

17 Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Finch EA, Ng DM, Rothman AJ. Are

unrealistic weight loss goals associated with outcomes for overweight women? Obes Res 2004; 12: 569–576.

18 Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Levy RL, Pronk NP, Boyle RG. Weight loss

goals and treatment outcomes among overweight men and

women enrolled in a weight loss trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;

29: 1002–1005.

19 Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, Cussler EC, Metcalfe LL,

Blew RM et al. Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful

weight management in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord

2004; 28: 1124–1133.

20 Teixeira PJ, Palmeira AL, Branco TL, Martins SS, Minderico CS,

Barata JT et al. Who will lose weight? A reexamination of

predictors of weight loss in women. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act

2004; 1: 12.

21 Ames GE, Perri MG, Fox LD, Fallon EA, De Braganza N, Murawski

ME et al. Changing weight-loss expectations: a randomized pilot

study. Eat Behav 2005; 6: 259–269.

22 Grodner M. Forever dieting: chronic dieting syndrome. J Nutr

Educ 1992; 24: 207–210.

23 The Airlie (VA) consensus conference. Standardization of Anthropometric Measurements. Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign,

IL, 1988.

24 Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression

Inventory, 2nd edn. The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio

TX, 1996.

25 Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR. Development

of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res

2001; 9: 102–111.

26 Battle J. Culture-Free Self-esteem Inventories, 2nd edn. PRO-ED:

Austin TX, 1992.

27 Mendelson BK, Mendelson MJ, White DR. Body-esteem scale for

adolescents and adults. J Pers Assess 2001; 76: 90–106.

28 Laessle RG, Tuschl RJ, Kotthaus BC, Pirke KM. A comparison of

the validity of three scales for the assessment of dietary restraint.

J Abnorm Psychol 1989; 98: 504–507.

29 Lluch A. Identification des conduites alimentaires par approches

nutritionnelles et psychométriques: implications thérapeutiques et

préventives dans l’obésité humaines. Université Henri Poincaré:

Nancy I, France, 1995.

30 Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to

measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom

Res 1985; 29: 71–83.

International Journal of Obesity

31 Bond MJ, McDowell AJ, Wilkinson JY. The measurement of

dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger: an examination

of the factor structure of the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire

(TFEQ). Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 900–906.

32 Westenhoefer J, Stunkard AJ, Pudel V. Validation of the flexible

and rigid control dimensions of dietary restraint. Int J Eat Disord

1999; 26: 53–64.

33 Paquette MC, Raine K. Sociocultural context of women’s body

image. Soc Sci Med 2004; 59: 1047–1058.

34 Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A. Body image and weight

control in young adults: international comparisons in

university students from 22 countries. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;

30: 644–651.

35 Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Foster GD. Assessment of body image

dissatisfaction in obese women: specificity, severity, and clinical

significance. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66: 651–654.

36 Viken RJ, Treat TA, Bloom SL, McFall RM. Illusory correlation

for body type and happiness: covariation bias and its relationship to eating disorder symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 2005; 38:

65–72.

37 Stice E, Agras WS, Telch CF, Halmi KA, Mitchell JE,

Wilson T. Subtyping binge eating-disordered women along

dieting and negative affect dimensions. Int J Eat Disord 2001;

30: 11–27.

38 van Strien T, Engels RC, Van Leeuwe J, Snoek HM. The Stice

model of overeating: tests in clinical and non-clinical samples.

Appetite 2005; 45: 205–213.

39 Cuntz U, Leibbrand R, Ehrig C, Shaw R, Fichter MM. Predictors of

post-treatment weight reduction after in-patient behavioral

therapy. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25 (Suppl 1):

S99–S101.

40 Elfhag K, Rossner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A

conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev 2005; 6: 67–85.

41 Pasman WJ, Saris WH, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Predictors of

weight maintenance. Obes Res 1999; 7: 43–50.

42 Westenhoefer J, von Falck B, Stellfeldt A, Fintelmann S.

Behavioural correlates of successful weight reduction over 3 y.

Results from the Lean Habits Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord

2004; 28: 334–335.

43 Westenhoefer J. The therapeutic challenge: behavioral changes

for long-term weight maintenance. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord

2001; 25 (Suppl 1): S85–S88.

�

Sonia Boivin

Sonia Boivin