Festi San Gorg 2016. Il‐Belt Victoria, Ghawdex. Nru 42, pp.64‐66.

MUSICIANS ON THE MALTESE ISLANDS PRIOR TO THE ESTABLISHMENT

OF THE MID‐NINETEENTH CENTURY BANDS

Anna Borg Cardona

This article is based on a presentation given at the seminar Exploring the Tradition and

Artistic Contribution of local Bands on 14th November 2015

Musicians have always played a very relevant part in the culture of the people of the Maltese

Islands. There were different instruments used over the years, and different influences that

predisposed us for the establishment of the wind, brass and percussion bands, which we

embraced so fully by the mid‐nineteenth century. Folk musicians, instrumentation in sacred and

secular music, pageantry and finally the early military bands all played a part.

First and foremost I cannot omit the influence of the Ottoman Bands (Mehter), which from

medieval times accompanied all Turkish attacks. Some of the Turkish instruments, most

significantly the kettledrum, were adopted in instrumentation of European bands and

orchestras. During the Great Siege of 1565, the Turkish attack on Malta was accompanied by

numerous musical instruments, several of which sounded ‘strange’ to the western ear.1

Mattheo Perez d’Aleccio, who in 1584 painted frescoes of the Great Siege in the Grand Master’s

Palace in Valletta, depicts long trumpets, kettledrums, smaller kettledrums, bass drums,

shawms and cymbals being played by the Turkish band. In Malta kettledrums, bass drum,

trumpets and cymbals all formed part of the later wind, brass and percussion bands.

On the Maltese Islands, instrumentalists, occasionally alone, but usually in very small groups,

accompanied all sacred and secular functions, family celebrations, public celebrations, feasts

and processions. Over the years different instruments were filling these various functions.

There were particular instruments which were associated with specific times of the year. The

żaqq and tanbur, for example, were closely associated with Christmas time and would perform

in the streets of towns and villages on Christmas Eve. The rabbaba or żafżafa (friction drum), on

the other hand, was used mostly during the carnival period.2 Stringed instruments had a strong

presence on the islands: they had their place in wedding processions (wilġa), and in wedding

entertainment, in dance music, and street entertainment. Violins or fiddles were mostly

1

Anna Borg Cardona, ‘Sounds of war and the exotic alla turca’ Treasures of Malta vol. XXI no.3,

(Summer 2015) 36‐43.

2

Anna Borg Cardona, ‘The Maltese Friction drum’ Journal of the American Musical Instrument

Society, vol. XXVII, (2002) 174‐210.

�Festi San Gorg 2016. Il‐Belt Victoria, Ghawdex. Nru 42, pp.64‐66.

associated with dance in both Malta and Gozo,3 whilst lutes are often mentioned in the

accompaniment of wedding quatrains in praise of the bride and groom and are already

recorded in the wedding context in Gozo as far back as the fifteenth century.4 The lira was a

very common peasant instrument throughout the eighteenth century and later.5 Guitars were

constantly present, particularly in association with song. All these stringed instruments

provided the traditional melodies and improvisations for the music of the Maltese people.

Though brass instruments may seem to have made their first appearance in the mid‐nineteenth

century, their sound was in fact already very familiar locally through secular music, sacred

music and pageantry. The Order of St John, ever since its arrival in 1530, was accompanied by

constant pageantry, which above all included drums and trumpets. It was customary to

announce the presence of Grand Masters with drums and trumpets; Proclamations, known as

Bandi, were also generally announced by drums in order to attract attention. On a more private

note, we find Grand Master de Verdalle (1582‐1595) enjoying music during his meals,

particularly trumpet and flute concerts.6

Looking at another important centre of music, the Mdina Cathedral, we find that between 1622

and 1649 there were instrumentalists of brass‐family instruments employed, playing trombone,

cornetta and trumpet.7 The same was happening in the Conventual church of St John, where it

is worth singling out the serpent, which we find recorded in 1756.8

Instrumentalists on board the Order’s galleys were usually also brass and percussionists. In

1673, Grand Master Cotoner was giving these musicians a special gift over and above their

salary. They were given 4

3

See Anna Borg Cardona Musical Instruments of the Maltese Islands: History, Folkways and

Traditions (Malta, FPM 2014) 145‐149.

4

CEM, AO, Vol.3, f.329v. Godfrey Wettinger, ‘Aspects of daily life in late medieval Malta and

Gozo’ Stanley Fiorini (ed.) in A Case Study of International Crosscurrents (1991) 81‐90.

5

NLM, Ms 143. Gian Piet. Agius De Soldanis Damma tal‐kliem vol.1, f.329v

6

Dal Pozzo, F. B. (1703). Historia della Sacra Religione di S. Giovanni Gerosolimitano detta di

Malta. Verona, Giovanni Berno.

7

ACM, Misc. 275, f.61v, f.68v.

8

Petruzzo Caruana, virtuoso del serpente, formed part of the Order’s Cappella of St John’s in

1756. See J. Vella Bondin Il‐Mużika ta’ Malta sa l‐aħħar tas‐Seklu Tmintax (Malta: Pin 2000) 48‐

49.

�Festi San Gorg 2016. Il‐Belt Victoria, Ghawdex. Nru 42, pp.64‐66.

scudi, as a New Year gift (‘per la Strena’). This happened every year and was still being awarded

by Grand Master Perellos in 1699. It is important to note that the musicians employed by the

Grand Masters were Maltese. In 1707 we find Paolo Balzan who was employed as tamborlino

getting a monthly salary of 2 scudi.9 Gio Batta Saliba, likewise tamborlino was getting 2 scudi 6

tari,10 and Barbaro Vella was getting the monthly salary of 2 scudi for playing the fifra.11

Looking at sacred processions on the Islands, it is evident that musicians had long formed an

integral part of these. Records show seventeenth‐century processions in Mdina were using a

spinetta or a regaletto, both of which were small keyboard instruments.12 These may also have

been accompanied by string instrumentalists, who were in regular employ with the Cathedral.

However, a marked change is recorded in a procession of the Immaculate Conception in

Valletta in 1796. Musicians were following a blue banner, and a crucifix and were in turn

followed by monks carrying a statue. The instruments included in this procession were drums,

pipes, horns and flutes. This shows that wind, brass and percussion bands had already taken

over from previous instruments and had started filling the function of accompanying sacred

processions.13

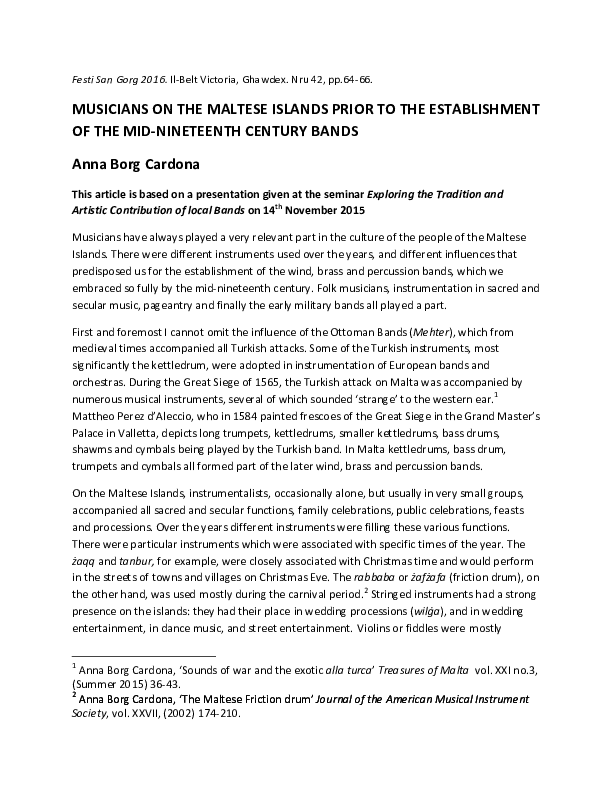

A caricature of the procession of St Lawrence in Birgu from the same period further records a

full fourteen‐strong band in uniform leading the procession: trumpets, French horns,

trombones, triangle, bassoon (or dulcian?), cymbals, bass drums, and jingles.

Militia Regiments also played an important part in the formation of bands. Already in the Militia

lists of the fifteenth century we find the presence of musicians listed as ‘juculari’.14 Though

their precise function is not known they are most likely to have been instrumentalists who

could sound the alert in case of danger and who would provide marching music. Gusè Gatt

claims that by the end of the eighteenth century, several towns and villages (such as Birkirkara,

9

AdeP, Ms 104, Rollo 1707‐1708, f.17v

Ibid, f.18v.

11

Ibid, f.5v.

12

Franco Bruni, Musica e Musicisti alla Cattedrale di Malta nei secoli XVI‐XVIII (Malta University

Press, 2011) 186. ACM Misc. 169 f.239, f.499.

13

Sven Sørensen and Joseph Schirò eds. Malta 1796‐1797: Thorvaldsen’s visit (Malta: Beck

Graphics, 1996) 40.

14

Godfrey Wettinger ‘The Militia Roster of Watch Duties of 1417’ The Armed Forces of Malta

Journal 1979. ‘The Militia List of 1419‐20’ Melita Historica 5/2 (1969), 80‐106.

10

�Festi San Gorg 2016. Il‐Belt Victoria, Ghawdex. Nru 42, pp.64‐66.

Fig.1 Caricature showing a late‐eighteenth century Brass Band in uniform, heading the St

Laurence Procession in Birgu. Anonymous, Courtesy Birgu Parish Museum.

Żebbuġ, Rabat, Mdina and Valletta), had their own Militia regiments, each with its own drums

and fife band. These musicians received a soldier’s pay and an additional bonus for band

performances during Carnival, Religious processions such as Corpus, l‐Imnarja, and during horse

races.15 The continued participation of these small bands of drums and fife in processions of

Good Friday and Easter Sunday can be confirmed through the several depictions of Gerolamo

Gianni throughout the nineteenth century. By 1800, Alexander Ball already had at San Anton

one of the earliest‐established wind and brass bands on the Islands.16

The influence of these military band instruments can be seen by the mid‐nineteenth century

when small groups of folk musicians known as Ta’ wara l‐bibien began to include band

instruments in their group instead of their more traditional instruments. These musicians

knocked at doors and performed for remuneration wherever they knew there was a family

celebration, such as an academic achievement, an engagement, a marriage, or the birth of a

child. An etching attributed to Charles Frederick de Brocktorff (1775‐1850) shows this very

clearly. Five musicians are seen playing clarinet, French horn, a very large drum, triangle and

cymbals at the door of a house in Valletta. These musicians may possibly have formed part of

15

Ġusè Gatt, in an appendix to the historical novel Il‐Famiglia T‐Traduta by Arturo Dimech (sd)

699‐704. Though information is taken from documents, sources are unfortunately not quoted.

16

Ġusè Gatt quoting NLM, Ms 94.

�Festi San Gorg 2016. Il‐Belt Victoria, Ghawdex. Nru 42, pp.64‐66.

regiments and may have been using their free time to earn some extra pennies. They could also

have picked up discarded instruments, as is surely the case with the cracked cymbals in this

etching.

Fig.2 Small Band of musicians ‘Ta’ wara l‐Bibien’. Etching attributed to Charles Frederick de

Brocktorff. Courtesy National Museum of Fine Arts, Valletta (Inv.no. 1459‐60).

At this point large changes began to take place. Instrumentalists joining military bands started

learning to play new and different instruments, and above all, began to read music notation. As

a result, the old traditional melodies and the improvisations were replaced by a new,

unfamiliar, written type of music, which included pieces like waltzes and quadrilles. An

anonymous mid‐nineteenth century poem entitled Il Caulata captures this moment in time,

poking fun at this very important turning point in band history.17

‘Idoqqu bhal professuri / fuq il‐karti ta’ Binet / They play like professors/ from papers of Binet/

Xi valz, xi sinfonia / Xi kwadrilja u xi terzett’.

A walz, a symphony / a quadrille or a trio.

From these humble beginnings in the mid‐nineteenth century, wind, brass and percussion

bands very soon mushroomed in every town and village of the Maltese Islands. They have since

made great strides and flourished over the years, and are now entirely embraced as an integral

part of our cultural identity.

17

Il Caulata – ossia canti guerrieri, per la Militia Maltese. Albert Ganado Collection. See Anna

Borg Cardona Musical Insruments of the Maltese Islands (2014) 16‐17.

��

Anna Borg Cardona

Anna Borg Cardona