[Anthony Pryer, ed., Claudio Monteverdi: Sacrae Cantiunculae; Madrigali Spirituali, Canzonette a 3

Voci. Claudio Monteverdi Opera Omnia, Vol. I (Cremona: Fondazione Claudio Monteverdi, 2012).

FINAL DRAFT, March 2012]

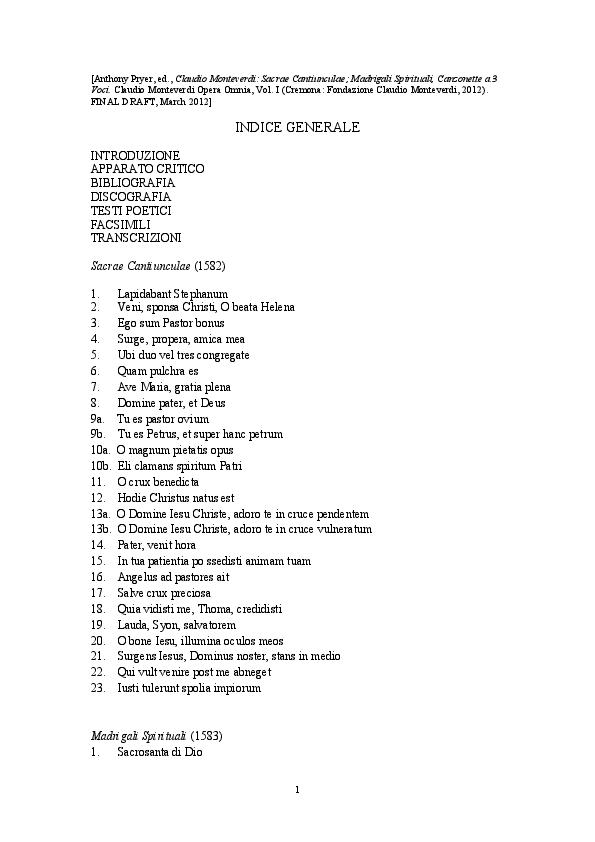

INDICE GENERALE

INTRODUZIONE

APPARATO CRITICO

BIBLIOGRAFIA

DISCOGRAFIA

TESTI POETICI

FACSIMILI

TRANSCRIZIONI

Sacrae Cantiunculae (1582)

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9a.

9b.

10a.

10b.

11.

12.

13a.

13b.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

Lapidabant Stephanum

Veni, sponsa Christi, O beata Helena

Ego sum Pastor bonus

Surge, propera, amica mea

Ubi duo vel tres congregate

Quam pulchra es

Ave Maria, gratia plena

Domine pater, et Deus

Tu es pastor ovium

Tu es Petrus, et super hanc petrum

O magnum pietatis opus

Eli clamans spiritum Patri

O crux benedicta

Hodie Christus natus est

O Domine Iesu Christe, adoro te in cruce pendentem

O Domine Iesu Christe, adoro te in cruce vulneratum

Pater, venit hora

In tua patientia po ssedisti animam tuam

Angelus ad pastores ait

Salve crux preciosa

Quia vidisti me, Thoma, credidisti

Lauda, Syon, salvatorem

O bone Iesu, illumina oculos meos

Surgens Iesus, Dominus noster, stans in medio

Qui vult venire post me abneget

Iusti tulerunt spolia impiorum

Madrigali Spirituali (1583)

1.

Sacrosanta di Dio

1

�2a.

2b.

3a.

3b.

4a.

4b.

5a.

5b.

6a.

6b.

7a.

7b.

8a.

8b.

9a.

9b.

10a.

10b.

11a.

11b.

L’aura del ciel

Poi che benigno

Aventurosa notte, in cui risplende

Serpe crudel

D’empi martiri

Ond’in ogni pensier ed opra santo

Mentre la stella appar nell’orïente

Tal contra Dio

Le rose lascia, gli amaranti e gigli

Ai piedi avendo i capei d’oro sparsi

L’empio vestìa di porpora

Ma quell mendico Lazaro

L’uman discorso quanto poco importe

L’eterno Dio quel cor pudico scelse

Dal sacro petto esce veloce dardo

Scioglier m’addita

Afflito e scalzo, ove a la sacra sponda

Ecco dicea, ecco l’agnel di Dio

De’miei giovenili anni

Tutte esser vidi le speranze vane

Canzonette a tre voci (1584)

1.

Qual si può dir maggiore

2.

Canzonette d’amore

3.

La fiera vista

4.

Raggi, dov’è il mio bene?

5.

Vita dell’alma mia

6.

Il mio martir

7.

Son questi’i crespi crini

8.

Io mi vivea

9.

Su, su, su, che’l giorno

10. Quando sperai

11. Come faro cuor mio

12. Corse a la morte

13. Tu ridi sempre mai

14. Chi vuol veder d’inverno un dolce aprile

15. Già mi credeva

16. Godi pur del bel sen

17. Giù lì a quel petto

18. Sì come crescon

19. Io son fenice

20. Chi vuol veder un bosco folto e spesso

21. Or, care canzonette

2

�INTRODUZIONE

Monteverdi’s Earliest Printed Music: Publishers and Patrons

This edition brings together the three earliest printed collections in Monteverdi’s

output – the Sacrae Cantiunculae (1582), the Madrigali Spirituali (1583) and the

Canzonette a tre voci (1584).1 The Sacrae Cantiunculae have never been presented

before with a full liturgical commentary, the Madrigali Spirituali have hitherto only

appeared in facsimile and without a commentary, and the Canzonette have never been

edited so as to display all of the stanzas of the texts underlayed to the music, and with

a flexible system of barring that takes proper account of the accentuation of the Italian

words. These collections were clearly designed to demonstrate the precocious ability

of the young Monteverdi (he was just fifteen years old in 1582), covering as they do

three important, contrasting musical genres – the motet, the spiritual madrigal, and the

canzonetta. Moreover, they all date from Monteverdi’s years in Cremona, and the

printers, publishers and patrons involved reveal interesting details about exactly how

he gained entry to the professional world of music.

The title pages of the three prints tell us that he was a disciple of Marc’Antonio

Ingegneri, who was maestro di cappella at Cremona cathedral. 2 The Ingegneri

connection is also declared on the title pages of his first two books of madrigals,

dating from 1587 and 1590. However, his third book of madrigals (1592) drops this

epithet, probably because he had already moved on to Mantua by that time, but also

conceivably because he knew Ingegneri was close to death in 1592: the dedication of

the Third Book is dated 27th June 1592, and Ingegneri died just four days later on 1st

July and is unlikely to have seen that volume in print. Monteverdi thereafter never

mentions Ingegeneri in any document that has come down to us, though his name is

appended to a list of exponents of the seconda prattica, in the “Dichiaratione” written

by Monteverdi’s brother and appended to the Scherzi Musicali of 1607. The

influence of the older composer on these early works seems to have been more as an

instructor than as a provider of his own compositions as direct models to be imitated.3

Only in the case of one motet, “Surge, propera”, does Ingegneri seem to have preempted Monteverdi by setting the same text earlier, and it is clear that Monteverdi’s

motet is not based on Ingegneri’s music but on that of Costanzo Festa’s “Surge amica

mea” to which, however, Ingegneri may have drawn his attention (see the

commentary to motet no. 4).

1

For a transcription of the title-pages of these publications see the next subsection, “The Sources”..

For the prefaces and dedications of the three prints see the section on the texts (below in this volume),

and also D. DE’ PAOLI, ed., Claudio Monteverdi: Lettere, Dediche e Prefazioni (Roma, Edizioni de

Santis, 1973), pp. 371-7.

3

For detailed discussions of the stylistic connections between Ingegneri and Monteverdi see: L.

SCHRADE, Monteverdi: Creator of Modern Music (New York, Norton and Co., 1951), Chapters 3 to 6;

D. ARNOLD, “Monteverdi and his Teachers”, in D. ARNOLD and N. FORTUNE, eds., The Monteverdi

Companion (London, Faber and Faber, 1968), pp. 91-109; G. TOMLINSON, Monteverdi and the End of

the Renaissance (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1987), pp. 35-6, 56-7; and I. FENLON,

“Marc’Antonio Ingegneri: un compositore tra due mondi”, in A. DELFINO and M. T. ROSA- BAREZZANI,

eds., Marc’Antonio Ingengneri e la musica a Cremona nel secondo cinquecento (Lucca, Libreria

musicale italiana, 1995), pp. 127-134. On other musicians associated with Cremona see R.

MONTEROSSO, Mostra bibliografica dei musicisti cremonesi – Catalogo storico-critico degli autori

(Cremona, Biblioteca Governativa e Libreria Civica, 1951).

2

3

�It cannot have been easy to find patrons and publishers for so young a composer.

Monteverdi’s first collection, the Sacrae Cantiunculae, has a Preface written in Latin

with a somewhat over-familiar tone addressed to “amantissime” Dom Stefano

Caminio Valcarenghi (who seems to have been a canon at Cremona Cathedral), with

thanks and praises for his “love” (“amor”) for the young Monteverdi and for the

“jovial spirit” (“hilaris animus”) of his character. This would suggest that that

Valcarenghi family had fairly close ties with the Monteverdis, a view that seems to be

corroborated by the appearance of both family names on the foundation list of the

Collegio dei Chirurghi (College of Surgeons) of Cremona in 1587.4 It is remarkable

that Monteverdi’s Sacrae Cantiunculae, his very first publication, was issued by the

prestigious Venetian printer Angelo Gardano, a connection that he must have owed to

his teacher since all of Ingegneri’s secular collections (madrigal books one to five,

1578-1587) were produced by Gardano. There are, incidentally, small signs

Monteverdi’s teacher may have found him a rather demanding and time-consuming

pupil. For example, in spite of Ingegneri’s otherwise steady flow of publications,

there is a gap between 1580 and 1584 when nothing was issued by him, and these are

precisely the years that saw the production of the three collections by Monteverdi

edited here.

The dedicatee of the Madrigali Spirituali, Alessandro Fraganeschi, represented a

step up the social ladder. He was a member of an important noble family in Cremona,

and in 1588 he served on the city’s Council of Ten.5 The Preface of the Spiritual

Madrigals tells us that it was Monteverdi’s first publication for four voices

(unfortunately only the Basso partbook survives), and the title page reveals that the

works were printed in Brescia at the instigation (“ad instanzia”) of Pietro Bozzola , a

bookseller in Cremona. In fact Pietro Bozzola seems to have had a relative (possibly a

brother), Tommaso, who was a publisher in Brescia who regularly worked with the

printer Vincenzo Sabbio, and this seems to explain why Monteverdi’s spiritual

madrigals were published in Brescia by Sabbio.6 Both of the Bozzolas apparently

acted as publishers without having printing houses of their own, and in 1592

Tommaso himself undertook in a similar way to petition the Venetian printer

Ricciardo Amadino to print Antonio Mortaro da Brecsia’s Il terzo libro delle

fiammelle amorose a 3. The title page has almost the same formula as Monteverdi’s

spiritual madrigals, proclaiming that they were printed at the instigation (“a

instanzia”) of Tommaso Bozzola the publisher.7 Outside of the realm of music the

Bozzolas are best known for having published in the 1580s the many pious works of

the fifteenth century German theologian Gabriel Biel (a founder member of Tübingen

University), whose writings had a very significant impact on the deliberations at the

Council of Trent. Monteverdi’s spiritual madrigals would have coincided very well

4

For a photographic reproduction of the list see E. SANTORO, La famiglia e la formazione di Claudio

Monteverdi (Cremona, Athenaeum Cremonense, 1967), Plate XI.

5

DE’ PAOLI, Claudio Monteverdi: Lettere, Dediche e Prefazioni, p. 376 (citing a manuscript by G.

BRESCIANI, Libro delle famiglie nobili della città di Cremona, surviving in the Libreria Civica in

Cremona).

6

A. CIONI, “Bozzola, Tommaso”, in A. GHISALBERTI, ed., Dizionario biografico degli italiani (Roma,

Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1971), Vol. 13, p. 243. In the index to D. W. KRUMMEL and S.

SADIE, eds., Music Printing and Publishing, the Norton/Grove Handbooks in Music (London,

Macmillan Press, 1990), the separate references to Tommaso and Pietro Bozzola in the book are

mistakenly taken to be only to Pietro.

7

E. VOGEL, A. EINSTEIN, F. LESURE AND C. SARTORI, eds., Bibliografia della musica italiana vocale

profana pubblicata dal 1500 al 1700 (Pomezia, Minkoff, 1977), 3 vols. [= NV (Il nuovo Vogel)], item

1967.

4

�with such a publishing venture, particularly since several of the madrigals were

concerned with events in the life of Christ (for example: no. 3, the nativity; no. 5, the

massacre of the innocents; no. 10, the baptism of Christ; no. 1, the crucifixion) just as

was the volume of Biel’s sermons, De Fastis Christi Sermones, issued by Tommaso

and Pietro Bozzola, and printed by Vincenzo Sabbio, in exactly the same year. It is

not known how Monteverdi came to know the poems by Fulvio Rorario, taken from

the latter’s Rime Spirituali (Venice, Franceschi and Francesco Guerra, 1581), which

provide the only source of the texts in the Madrigali Spirituali.8 It may be significant,

however, that the only book connected with music known to have been produced by

the Guerra publishers is Zarlino’s Le istitutioni harmoniche (1558). We do know that

at some point Monteverdi acquired the 1573 edition of this work since a copy signed

by him survives,9 hence he (or Ingegneri) may have been alerted to Rorario’s poems

during some communication with the publishers. No other composer seems to have

set these verses.

Whatever the local motivations for printing the Madrigali Spirituali, they also

formed part of a wider concern with the genre during the 1580s, the high point of the

Counter-Reformation. For example, Philippe de Monte and Palestrina published

spiritual madrigals in 1581,10 Marenzio in 1584,11 and Monte then went on to publish

four more collections (in 1583, 1589, 1590 and 1593). 12 Interestingly enough,

Monteverdi demonstrates, in a letter of 2nd December 1608, that he had followed the

careers of precisely these three composers with some interest.13 There is also no

doubting Ingegneri’s connection with the wider Counter-Reformation movement

which was centred on Milan and its territories, the region in which Cremona was the

second largest city.

The ideals of the Counter-Reformation were strongly

promulgated by Cardinal Borromeo in Milan and by Nicolò Sfondrati, Bishop of

Cremona (from 1560). The latter became Pope Gregory XIV in 1590 and Ingegneri

over the course of his career dedicated three works to him – his Sacrum cantionum

quinque vocibus liber primus (1576), his Liber secundus missarum (1587), and his

Sacrae cantiones (1591). In the event, however, Ingegneri’s output of spiritual

madrigals was small and his works in that genre tend to be scattered among his

secular madrigal books.14 For example, the devotional madrigal “Poscia che troppo i

miei peccati indegni” opens his Il second libro de’ madrigali … a quattro voci

(Venezia, Angelo Gardano,1579), a collection dedicated to Nicolò’s brother, Baron

Paolo Sfondrati.

The Preface of the Canzonette of 1583 is addressed to Pietro Ambrosini, a member

of a patrician family apparently originally from Bologna, and Monteverdi’s most

prestigious patron to date. The Ambrosini were members of a well-established

Cremonese literary and artistic academy (the Accademia degli Animosi) as, indeed,

8

For more on Rorario see Professor Ragni’s remarks in the Text section below.

For a photographic reproduction of the signed title page see G. REESE, Music in the Renaissance

(London, Dent and Sons, 1954), Plate IV (opposite p. 366). The printer for the Zarlino volume was

Francesco Senese, but Guerra provided editorial help. See the remarks in the facsimile edition: I.

FENLON and P. DA COL, eds., Gioseffo Zarlino, Le Istitutioni Harmoniche, Venice 1561 (Bologna,

Arnaldo Forni, 1999), p.7.

10

NV items 802 and 2101.

11

NV item 1676 (reprinted 1588, 1606 and 1610).

12

NV items 803, 804, 805 and 733.

13

É. LAX, ed., Claudio Monteverdi: Lettere (Florence, Olschki, 1994), p.22.

14

See ELENA BARASSI, “Il madrigale spirituale nel cinquecento e la raccolta monteverdiana del 1583”,

in R. MONTEROSSO, ed., Congresso internazionale sul tema Claudio Monteverdi e il suo tempo:

relazioni e comunicazioni (Venezia, Mantova, Cremona, 1968), pp. 217-246, at p. 218.

9

5

�was Ingegneri.15 This would explain not only how the connection with the dedicatee

was made but why some of Monteverdi’s canzonette (and their texts) are more selfconsciously complex than many other examples of the genre. For example, several of

the texts contain classical references (no. 1, Jove; no. 3, the Sirens and the basilisk; no.

9, Phoebus and Damon; no. 12, Narcissus, Helen of Troy, Ganymede and Jove), and

the music sometimes displays ambitious attempts at counterpoint (nos. 3, 7, 9 and 10)

or sections in proportional notation (nos. 4 and 16). Other texts seem to be borrowed

from collections by those associated with Milan: Gasparo Costa for nos. 10 and 16;

Gioseppe Caimo for no.13; and no. 11 has a text by Pietro Taglia who worked at

Santa Maria presso San Celso in that city.16

Two other important sources of the canzonette texts are Orazio Vecchi’s Canzonette

di Orazio Vecchi da Modona [sic] Libro Primo a quattro voci (Venezia, Angelo

Gardano, 1580) [NV item 2796], which contains settings of items 2, 4, 7, 12, 19 and

20; and Gasparo Fiorino’s Libro Secondo Canzonelle a tre e a quattro voci di

Gasparo Fiorino della città di Rossano, musico. In lode et gloria d’alcune signore et

gentildonne genovesi (Venezia, Gardano, 1574) [NV item 988], which includes

settings of items 5, 14, 15 and 17. The Vecchi and Fiorini collections, however, were

widely disseminated, and their use as a resource for Monteverdi’s Canzonette need

hold no personal or local significance. Interestingly, however, the Vecchi-connected

pieces dominate the first half of Canzonette collection (up to and including no. 12), as

do the pieces with classical allusions or political references. Canzonetta no. 8

mentions the eagle (the symbol of the Habsburg Emperors), as well as the salamander

(the emblem of the Kings of France), and no. 9 plays on the word “Alba”, apparently

a reference to the famous Spanish noble dynasty. The first half of the collection also

contains most of the poems where the final line of each stanza is the same or a close

variant, and it has all of the pieces (nos. 3, 7, 9, 10, 12 and 13) which have their

second sections of music through composed without any shorthand indications of

internal repetitions (see the section on “Canzonetta Form” below). These features

may reflect Monteverdi’s initial attempts to tailor his compositions precisely to the

known tastes of Ambrosini and the Accademia degli Animosi. But the second half of

the collection seems to have been more loosely constructed, as time became pressing,

out of works with less integrated types of poetic structure, largely based on items in

the Fiorini collection. The two sections of the collection are divided by an odd little

canzonetta (no. 13) comprising a single stanza, and possibly inserted at a late stage in

the collection in tribute to the composer Gioseppe Caimo who had recently died (see

the critical commentary).

The Sources

For each of Monteverdi’s three earliest printed collections there is only one viable

surviving copy upon which to base an edition. The title page of the 1582 Sacrae

Cantiunculae reads as follows:

15

V. LANCETTI, Biografia cremonese: ossia dizionario storico delle famiglie e persone per qualsi

voglia titolo memorabili e chiare spettanti alla città di Cremona dai tempi più remoti fino all’età

nostra (Cremona, G. Borsani, 1819), Vol. I, p. 213.

16

Details in the Apparato Critico section below.

6

�SACRAE CANTIVNCVLAE / TRIBVS VOCIBVS / CLAVDINI MONTISVIRIDI CREMONENSIS

/ EGRERII INGEGNERII DISCIPVLI / LIBER PRIMVS / nuper editus. / [printer’s stamp showing a

cart within a decorative frame] / Venetijs Apud Angelum Gardanum / MDLXXXII

The dedication is to Stefano Caninio Valcarengo and is dated 1st August 1582.The

sole surviving copy, and hence the one used for this edition, is in Castell’Arquato (a

small town near Piacenza), Archivio Parrocchiale [I-CARp].17 Each partbook is in

folio oblong format. It is significant that the title page indicates by the rubric “LIBER

PRIMUS” that this publication was intended to be the first of a series although – so

far as we know – no other such volumes were published by Monteverdi. Moreover,

no other similar three-voiced motets appear anywhere else in his output.

The 1583 Madrigali Spirituali also survives in a single copy, but the loss is greater

since only one partbook remains from the original four. For the editorial difficulties

that arise from this situation see the Apparato Critico section. The title page is as

follows:

MADRIGALI / SPIRITUALI /A QVATTRO VOCI / Posti in Musica da Claudio Monteverde

Cremone- /se, Discepolo del Signor Marc’Antonio / Ingegnieri . / Nouamente poste in luce. / [printer’s

stamp containing a griffin holding up a plinth and a winged globe within a decorated frame] / In

Brescia, per Vincenzo Sabbio; Ad instanza di Pietro / Bozzola, Libraro in Cremona. 1583.

The dedication is to Alessandro Fraganesco and is dated 31st July 1583. The Basso

partbook is in folio choirbook format, and can be found in the Museo Internazionale e

Biblioteca della Musica di Bologna (previously the Biblioteca del Civico Museo

Bibliografico Musicale), [I-Bc].18There are no other self-contained collections of

spiritual madrigals from Monteverdi, but the Canto parts of two otherwise unknown

examples (i.e., compositions that are not contrafacta of known secular madrigals) –

“Se d’un angel’il bel viso” and “Fuggi, fuggi cor, fuggi a tutte l’or” – appear in a

manuscript in Brescia, apparently written down by a certain Michele Pario in Parma

in 1610.19 To these should be added five examples of madrigali morali that open

Monteverdi’s Selva Morale e Spirituale of 1640. 20 It may be that a copy of

Monteverdi’s Madrigali Spirituali made it to Rome (and perhaps still survives there),

because two works published in 1590 21 by Michelangelo Cancineo who had

associations with Rome and Viterbo – once a rival of Rome for the residency of the

popes – show melodic similarities to two of the madrigali spirituali bass lines:

Cancineo’s “Era ne la stagioni” resembles no. 7a, “L’empio vestìa”; and his “Cresce

la fiamma” is similar to no. 9a, “Dal sacro”.

The 1584 Canzonette do survive intact, but again in only one complete copy. The

title page reads as follows:

17

F. LESURE, ed. Répertoire international des sources musicales, Recueils imprimés XVI-XVII siècles,

ed. F. LESURE (München-Duisburg, Henle-Verlag, 1960-)[ = RISM], Series A, item 3443.

18

RISM Series A, item 3444; NV item 1943.

19

Biblioteca Queriniana, shelf-mark MS L.IV.99. See P. FABBRI, Monteverdi, trans. Tim Carter

(Cambridge, 1994), p.108 for the details. See further: P. GUERRINI, “Canzonette spirituali del

Cinquecento”, Santa Cecilia, xxiv (1922), 6-8; and J. KURTZMAN, “An Early 17th-Century Manuscript

of Canzonette e madrigaletti spirituali”, Studi musicali, viii (1979), pp. 149-71.

20

Modern edition in D. STEVENS, ed, Selva Morale e Spirituale, Claudio Monteverdi: Opera Omnia,

Tomo XV (Cremona, Fondazione Claudio Monteverdi, 1998), Volume II, pp. 205-255. See also G. F.

MALIPIERO, ed., Monteverdi: tutte le opere [Asolo? n.d., (1926-42)] (Vienna, 1954-68), vol. XV/1.

21

In his Il Primo Libro de Madrigali di Michel’Angelo Cancineo … a quattro, cinque, sei et otto voci

(Venezia, Angelo Gardano, 1590). RISM series A item 1590-21; NV item 475.

7

�CANZONETTE / A TRE VOCI: /DI CLAVDIO MONTEVERDE / Cremonese, Discepolo del Sig.

Marc’Antonio / Ingegnieri, nouamente poste in luce, / LIBRO PRIMO. / [Printer’s stamp within a

decorative frame showing a pine cone adorned with the motto: AEQVE BONUM ATQVE TVTVM] /

VENETIA / Presso Giacomo Vincenzi, & Ricciardo Amadino, compagni. /MDLXXXIIII.

The dedication is to Pietro Ambrosini and is dated 31st October 1584. The sole

surviving complete copy is in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich [D-Mbs].22

The partbooks are in folio oblong format and they are the main source for this edition.

However, a Canto partbook survives in the Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della

Musica di Bologna (previously the Biblioteca del Civico Museo Bibliografico

Musicale) [I-Bc]; Canto and Tenore partbooks can be found in the Bibliothèque

Nationale, Paris [F-Pn]; and a Basso partbook is in the British Library in London

[GB-Lbl]. These isolated partbooks all appear to be from the same print run as the

complete copy in Munich. The evidence for this is varied but, for example, in the

Munich Basso partbook, p. 8 (“Il mio martir”), the damaged stem on the eighth note

from the end of stave two is also to be found in the Basso partbook in London.

As with the Sacrae Cantiunculae, the canzonette collection appears to promise (by

the term “LIBRO PRIMO”) that the collection will be part of a series. No second

volume has survived, but four more unaccompanied canzonette by Monteverdi can be

found in Antonio Morsolino, Il primo libro delle canzonette a tre voce … con alcune

altre de diversi eccellenti musici (Venezia, Ricciardo Amadino, 1594).23 Possibly

these works were a “residue” of Monteverdi’s attempts to complete a second volume.

It might also be the case that these pieces that were the “four canzonette by messer

Claudio Monteverdi” that Valeriano Cattaneo (perhaps a relative of Monteverdi’s

wife, Claudia Cattaneo) sent from Mantua to the wife of Alfonso II of Ferrara,

Margherita Gonzaga, with a letter of 4th December 1594.24 Other canzonette appear

sporadically in Monteverdi’s seventh, eighth and ninth books of madrigals (1619,

1638 and 1651), for example, and in his 1632 Scherzi Musicali, but these later pieces

are accompanied by instruments and are unlikely to be related to his youthful

ambition to produce a second volume comprised exclusively of canzonette for voices

alone.

The printed notation in all three of these early collections has very few errors by the

normal standards of production in the period. In the Sacrae Cantiunculae items 6 and

19 each has a single misprint, and in the Canzonette items 2 and 19 each requires a

single minor adjustment. In the Madrigali Spirituali item 10a appears to have the

wrong time signature. The Index of the Sacrae Cantiunculae gives the wrong title for

item 2. (See the Apparato Critico section for all the relevant details).

Editorial Methods

The purpose of this edition is to reveal and clarify the intentions of Monteverdi in

respect of the music here, while offering supportive commentary for scholars and

performers alike on the contexts of the compositions, and on aspects of the text

22

RISM series A, item 3452; NV item 1898.

Modern edition in G. F. MALIPIERO, ed., Monteverdi: tutte le opere, vol. XVII, pp.1-7. An earlier

version of Malipiero’s edition, possibly produced in Asolo,1926-42, seems to have been privately

printed and does not contain these items. They appear in this supplementary Volume XVII that was

issued in 1966.

24

See FABBRI, Monteverdi, pp. 31-2, and 280 fn. 18. Fabbri doubts that the four canzonette should be

linked to those in the 1594 Morsolino publication, but he does not explain why.

23

8

�setting and performance issues. The approach to the editing of the texts has to be

somewhat different since Monteverdi and/or his publishers clearly were not overly

concerned with strictly canonical versions of liturgical texts in the motets, or with

making all aspects of the poems of the spiritual madrigals or canzonette conform to

literary standards in relation to scansion, spelling or poetic word order and content.

Consequently attempts have been made to construct out of the occasionally confused

and inconsistent presentation in the print (not at all unusual for musical repertories),

versions of the texts that are acceptable in literary and/or liturgical terms. Full details

are given in Professor Ragni’s section below on the texts.

1. The Presentation of the Score

Since the collections were issued in partbooks (Cantus,Tenor, Bassus; Canto, Tenore,

Basso) the names for each part are fixed throughout the collections notwithstanding

the varying ranges for each part found across the compositions included . We have

kept the given part names while indicating the range of each voice-part at the

beginning of each piece. This has led to some apparent anomalies – in Sacrae

Cantiunculae item 19, for example, the part labelled Tenor lies above the Cantus for

half the piece – but the critical commentaries indicate which modern voice ranges

would be suitable to sing each part. On issues of possible transposition see Section 6

below. Original note values have been kept wherever possible, though in some rare

instances of proportional notation (for example, at the end of the spiritual madrigal no.

7b) modern note values differ in appearance from the printed ones. Further details are

in Section 3 on mensuration below. The final note for each composition has generally

been standardized to a breve with a fermata (in the case of the Sacrae Cantiunculae)

or a semibreve with a fermata (in the case of the Canzonette). Exceptions to this

include motet no. 7 (where Monteverdi failed to make all parts end together – see the

critical commentary), and canzonetta no.2 where a long finale note would have

implied an accent on the wrong syllable of the final word “Giove”. The final notes of

the Madrigali Spirituali are varied (as in the print) since, with the loss of the other

partbooks, it is impossible to know what is happening in the other voices. Modern

bars (measures) and bar numbers have been supplied. In general the pieces have not

been barred in a regular “mathematical” way, but more flexibly to show how the

music supports the changing accentuation of the text. In the case of the canzonette

(which are strophic), this has been problematic since sometimes later stanzas will

require a different barring. Hence in the case of canzonette nos. 2 and 21 the final

stanzas have been transcribed separately with new barring, and in no. 4 (bb. 16-17,

Tenore and Basso parts) the text accents imply a hemiola rhythm across two groups of

triplets , and the simplest way to indicate this was to put accents above the notes. See

also the section on text underlay below.

2. Text Underlay

Details of the approach to orthography and the standardization of the texts and

punctuation are given in Professor Ragni’s edition of the texts below. In cases where

text phrases have needed to be repeated but this is not indicated in the print, or where

the print simply indicates a repetition of a phrase with the number “ii”, those sections

of the text are printed in italics since their exact distribution under the music is the

result of an editorial decision. In the case of the Canzonette all of the stanzas are

placed directly under the music and not separately from it as we find in the original

print. Where italics are required for the text in stanza 1, they have also been kept at

the same points for subsequent stanzas, since when making the edition the words of

9

�those later stanzas could not be underlayed to the music mechanically, as it were, at

those points, but required fresh editorial decisions. In the Canzonette for some stanzas

the long notes need to be split into smaller note values to fit a great number of

syllables. Those smaller note values are linked together with dotted tie marks (see,

for example, canzonette nos. 14, 15 and 17). Very occasionally a word has been

added to the original text so as to comply with the scansion requirements of the poetry,

or the accentual requirements of the music; such added words are placed in square

brackets (see for example “[un] angelo” in stanza three of canzonetta no. 15). There

are a few instances where Monteverdi has changed the word order of the poetry

apparently for musical reasons: see, for example, the commentary to canzonetta no.

14.

3. Mensuration and Proportions

In the Sacrae Cantiunculae most of the motets are in C-stroke time. These items do

not generally present problems, and when there is a switch from duple to triple metre

it is usually instigated by the meaning of the text: ten of the twenty-six motets change

into triple metre to emphasize a particular word (such as “Alleluia”), or an image (as

at “flores apparuerunt” in motet no. 4, Surge propera). In the Madrigali Spirituali the

mensuration issues are relatively minor , but items 4b, 6a and 6b pose isolated

questions concerning proportions, and the C-stroke signature for item 10a seems to be

a printer’s error and should read C as with its partner-motet, 10b (see the editions and

critical commentaries). In the Canzonette most of the items are in C time. However,

four of the pieces (nos. 2, 4, 9 and 14) alternate binary and triplet sections, with the

latter being indicated by colored notes. The triple rhythms of the color sections are

further underlined by a “3” being inserted intermittently amid the black notes.

Canzonette nos. 2 and 9 are relatively unproblematic since the length of the semibreve

is the same in both the duple and triplet sections – that is, they keep the semibreve

tactus throughout. However, in nos. 4 and 16 we find that the minim tactus of the

binary section alternates with the semibreve tactus of the triplet sections, so that the

length of a semibreve in the triplet section is the same as that of a minim (not a

semibreve) in the binary section. Our edition indicates the proportional speeds

between these sections by the placing of equivalent note values for each section above

the stave at the point where the sections meet. It is difficult in these pieces to give a

precise notion of the speed at which they should be taken since there is no clear

evidence, though the intelligible enunciation of the text should always be a concern in

conjunction with an awareness of the number of small note values in the piece.25

4. Accidentals

Whenever the musical prints place an accidental against a note it appears alongside

that note in our score. This is the case even if modern conventions would consider the

first appearance valid for the entire bar. On all other occasions where accidentals are

suggested editorially – either to remind the performer that an accidental occurring a

few notes earlier remains valid, or to cancel a previous accidental where there might

25

On broader questions of proportions and speeds see the following contemporary treatises: A.

BRUNELLI, Regole utilissime per li scolari (Firenze, Volcmar Timan, 1606); ROCCO RODIO, Regole

di musica (Napoli, 1608); and A. PISA, Battuta della musica (Roma, Bartolomeo Zannetti, 1611). See

also: A. M. VACCHELLI, “Monteverdi as a Primary Source for the Performance of his own Music”, and

R. BOWERS, “Proportioned Notations in Banchieri’s Theory and Monteverdi’s Music”, both in: R.

MONTEROSSO, ed., Performing Practice in Monteverdi’s Music: The Historic-Philological Background

(Cremona, Fondazione Claudio Monteverdi, 1995), pp. 23-52, and 53-92 respectively.

10

�be ambiguity, or to signal that the original print has omitted an accidental in error –

they are placed above the note. No instances occur where an absolutely necessary

accidental has been omitted from the print, so all editorial additions are either

precautionary (for example, making clear repeated accidentals) or they offer one

possible solution to an ambiguous harmonic moment. However, some instances do

deserve special mention. For example, in Sacrae Cantiunculae item 2 the printed Bnatural in the Bassus at b. 10 destroys the exact imitation with the Cantus in b.8; it has

been retained but the consequence has been signalled in the commentary. In

canzonetta no. 19, the Tenore part (b.14) has a redundant A natural sign in the print,

clearly included in error – this has been omitted in the edition. As explained in the

Apparato Critico section the application of accidentals to the madrigali spirituali is

problematic since only one partbook survives. On the “tierce de Picardie” effect at the

end of canzonette nos. 1, 2, 4, 7, 8 and 10, see the commentary to canzonetta no. 1.

5. Canzonetta Form

Most of the texts of the canzonette in Monteverdi’s collection have three or four

stanzas, and each stanza tends to have three or four lines of poetry. The words are set

to the music according to a standard formula. The music is divided into two sections,

A and B, both of which are repeated. The B section always sets the two final lines of a

stanza whether the stanza has four lines or poetry or three. Hence the A music sets the

first two lines in a 4-line stanza, and the first line only in a 3-line stanza. However,

there is a complication. In fifteen of the twenty-one pieces the print contains what

looks like a single barline on the stave – there are no other barlines – just before the

final line of poetry in the B section (the exceptions are nos. 3, 7, 9, 10, 12 and 13). It

seems likely that this implies that, in those pieces with the single barline, the final line

of the poetry with its music should be sung again after the usual repeat of the B

section. There is some corroborative evidence for this view. For example in Vecchi’s

1580 setting of the text of no. 4, “Raggi, dov’è il mio bene?” in his Canzonette di

Orazio Vecchi da Modona Libro Primo a quattro voci (item 10), which is where

Monteverdi seems to have acquired the text, Vecchi does repeat the final line again

but the repeat of that line is fully written out and so there is no need of any special

signal (such as an inserted barline) indicating that this should happen. The question

then arises whether, in those pieces with the repeated final line (after the repeat of the

B section), the usual repeat of the B section should still end in the first time bar,

saving the second time bar only for the repeat of the final line. If we take this

approach then the full scheme for the performance of Monteverdi’s first stanza of his

setting of “Raggi, dov’è il mio bene?” would be as follows:

A music

1. Raggi, dov’è ‘l mio bene?

2. Non mi date più pene,

A music repeated

1. Raggi, dov’è ‘l mio bene?

2. Non mi date più pene,

← second time bar

B music

3. ch’io me n’andrò cantando dolce aita:

4. Questi son gl’occhi che mi dan la vita.

← first time bar

B music repeated

3. ch’io me n’andrò cantando dolce aita:

4. Questi son gl’occhi che mi dan la vita.

← first time bar again

11

�Second half of B music

4. Questi son gl’occhi che mi dan la vita.

← second time bar (with “tierce de Picardie”)

Even in this scheme there is a further issue concerning the final chord with its “tierce

de Picardie” effect: should that chord with its effect be reserved for the very end of

the piece? If so, all repeats of the B section in the early stanzas should still finish in

the first time bar, and there should be no repeats of the final lines of the early stanzas,

and the repeat of the final line of text (signalled by the inserted barline) should only

be applied to the last stanza of the piece. Once that final line of the last stanza is

repeated, only then should the music move into the second time bar of the B section

to conclude the work on a “tierce de Picardie”. In the case of “Raggi, dov’è il mio

bene?”, this would apply to the repeat of the line “Questi son gli occhi donde il ciel

s’indora” at the end of stanza three.

Clearly, although the printer inserted the single barline into the notation for a reason,

it would have been extremely complicated to indicate for each piece containing such a

barline exactly what was intended by it, and editorial suggestions as to its particular

application for each piece will be found in the critical commentaries. It should be

noted that these indicative barlines also occur in another collection (mentioned

earlier) containing canzonette by Monteverdi: Antonio Morsolino’s Il primo libro

delle canzonette a tre voci … con alcune altre de diversi eccellenti musici, published

in 1594. Both Monteverdi’s “Io ardo si” (item 2) and Morsolino’s “Come lungi da

voi” (item 17) have them, though Malipiero’s edition of the former does not take that

feature into account.

6. Transposition Issues

It is possible that certain pieces might invite downward transposition. For example,

those pieces in the Sacrae Cantiunculae with a G clef in the top voice (items 10 to 16,

and 21) have a written range approximately a 4th higher than the other motets, and the

clef combination for most of these – G2, C2, C3 – has become a standard signal for

the application of so-called “chiavette” transposition, though the term first appears as

late as the 18th century in Giuseppi Paolucci’s Arte pratica di contrapunto (Venezia,

1765), and debates as to the applicability of the system are still in disagreement and

intense. Most of the canzonette have a high written range with a G2 clef in the top

voice, the major exceptions to this being items 13 and 15 which have a lower range

and are the only canzonette to have the clef combination C1, C1, C4 (see the critical

commentary).

7. Liturgical Contexts

Since Monteverdi’s motets seem not to be designed for specific church services, and

may have been intended for private devotions or domestic performance, it has not

seemed appropriate to attempt to match particular items to specific services within the

liturgy familiar to Monteverdi in the Milanese region. In any case, it is clear that

Monteverdi acquired some of the texts from previous settings, and those settings were

selected and composed at some remove from his local liturgical observances. Hence,

as indicated in the Apparato Critico section, references are made in this edition to

indicative versions only of the texts and their usual placing within the liturgy, as

specified in modern chant books. Full details are in the commentaries.

Acknowledgements

12

�The editor warmly thanks Professors Raffaello Monterosso and Anna Maria

Monterosso Vacchelli for their invaluable and detailed help on many aspects of the

edition, and Professor Eugenio Ragni for his meticulous editions of the words as texts

in their own right. Dr Naomi Matsumoto deserves special thanks for her assistance

with the complex transfer of the transcriptions into computer files (as well as other

matters), and Matteo Dalle Fratte for his good-natured help with final corrections and

adjustments to the layout.

13

�APPARATO CRITICO

ABBREVIATIONS

b., bb.

D-Mbs

F-Pn

GB-Lbl

I-Bc

I-CARp

I-Rvat

NV

RISM

SV

bar (measure), bars (measures).

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale.

London, British Library.

Bologna, Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica (previously

the Biblioteca del Civico Museo Bibliografico Musicale).

Castell’Arquato, Archivio Parrocchiale.

Roma, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Bibliografia della musica italiana vocale profana

pubblicata dal 1500 al 1700, ed. E. Vogel, A. Einstein, F. Lesure & C.

Sartori, 3 vols. (Pomezia, Minkoff, 1977). [Il nuovo Vogel].

Répertoire international des sources musicales, Recueils imprimés

XVI-XVII siècles, ed. F. Lesure (München-Duisburg, Henle-Verlag,

1960-).

M.H.STATTKUS, Claudio Monteverdi: Verzeichnis der erhalten Werke:

kleine Ausgabe (Bergkamen, Musikverlag Stattkus, 1985).

Sacrae Cantiunculae (1582)

Previous Modern Editions

There are three previous complete modern editions of the Sacrae Cantiunculae:

GIUSEPPE TERRABUGIO, ed.,Canzoni Sacre – Sacrae Cantiunculae – a tre voci. Ridotte nella

scrittura moderna e aggiuntivi i segni dinamici convenzionali per colorito musicale da G. Terrabugio

(Milano: Bertarelli & C., 1909).

GIAN FRANCESCO MALIPIERO, ed., Monteverdi: tutte le opere [Asolo? n.d., (1926-42)] (Vienna,

1954-68), vol. XIV/1. The early edition, possibly produced in Asolo, seems to have been privately

printed. The Vienna edition contains revisions only in volumes VIII, XV and XVI. A supplementary

volume (XVII) was issued in 1966.

GAETANO CESARI, ed., La musica in Cremona nella seconda metà del secolo XVI e i primordi

dell’arte monteverdiana: Madrigali a 4 e 5 voci di M. A. Ingegneri e le Sacrae cantiunculae e

canzonette di Monteverdi, in Istituzioni e monumenti dell’arte musicale italiana, I, vi (1939).

The Terrabugio and Cesari editions both provide a piano reduction of the score with the edition.

Terrabugio’s score uses modern clefs and expression marks, and some items are transposed. Cesari

presents the score using the original clefs and adds little except phrase marks. Malipiero uses modern

clefs. None indicates the use of ligatures or coloration in their scores. Significant errors and variants in

these editions are noted below.

There are other editions of isolated items in this motet collection, but they are mostly instrumental

arrangements or contrafacta allocating English words to the original music. Only Fellerer in his edition

of Angelus ad pastores ait shows evidence of having independently consulted the original print (see the

commentary to motet no. 16), and thus his is the only other edition noted.

14

�Liturgical Sources

It has not been possible to identify the precise sources of the liturgical texts employed by Monteverdi.

This is because sixteenth-century liturgical sources from Cremona seem not to have survived, and in

any case those used by Ingegneri and Monteverdi probably sometimes derived from Milanese or

Roman uses. Moreover, on some occasions (as with no. 6, Quam pulchra es) Monteverdi clearly based

his work on a previously existing polyphonic models which may have had their origins far from

Cremona. We do know that Pope Pius V instituted a reformed Breviary (in 1568) and Missal (in 1570);

their possible relationship to Monteverdi’s works requires further investigation. Since there is such

uncertainty it seemed appropriate whenever possible to give references to “indicative” versions of the

chants and their texts in modern chant books (see the bibliography for full details of the editions

employed ) such as the Liber Usualis (1961), the Antiphonale Monasticum (1934), the Processionale

Monasticum (1893), or the Liber Responsorialis (1895).

No.1. LAPIDABANT STEPHANUM [SV207]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 1; Tenor, p. 1; Bassus, p. 1

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve.

Liturgical context: Respond at Matins for the Feast of St. Stephen, 26th December.

See for example the Lucca Antiphonary [facsimile in Paléographie musicale, XII

(Tournai 1906), p.44]. This motet was perhaps placed first in the collection out of

homage to another saintly ”Stephen”, canon Don Stefano Caninio Valcarenghi, under

whose protection this collection found its way into print.

Clefs: C1; C3; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F.

Range: 13 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 1; Malipiero, pp. 1-2; Cesari, pp. 216-7. Terrabugio

has a text error: “Lapidabant Stephanum innocentem”. Malipiero (p.1) has the wrong

clef for the bass part placing it an octave higher than Monteverdi intended.

No.2. VENI, SPONSA CHRISTI, O BEATA HELENA [SV 208]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 2; Tenor, p. 2; Bassus, p. 2

The title is given as in the text incipit. The Index [unnumbered p.18] gives: “Veni in

hortum meum”.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve (but on the dotted breve from b.25).

Liturgical context: Magnificat antiphon, 1st Vespers for the Common of Virgins, in

this case for the Feast of St. Helena, 18th August. See for example the Liber Usualis, p.

1209. In the motet the words “O beata Helena” are inserted into the antiphon text.

15

�Clefs: C1; C3; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke. Circle-stroke 3/2.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F.

Range: 13 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Bassus: b. 10: the B-natural is in the print but destroys the exact imitation with the

Cantus (which has a B-flat). If the first B is made flat then there is a case for

flattening the E in the tenor part in b. 10.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 2; Malipiero, pp. 3-5; Cesari, pp. 218-19. Malipiero

has the title “Veni in hortum meum’ (as in the Index, but not in the text underlay), and

the wrong clef for the bass part placing it an octave higher than Monteverdi intended.

No.3. EGO SUM PASTOR BONUS [SV 209]

Partbooks: Cantus, pp. 2-3; Tenor, pp. 2-3; Bassus, pp. 2-3.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto/Tenor, Tenor/Bass.

The beat is on the semibreve (but on the dotted breve from b. 22).

Liturgical context: Magnificat antiphon, 2nd Vespers, 2nd Sunday after Easter. See for

example the Liber Usualis, p. 816. This text was also set (later) by Monteverdi’s

teacher, Ingegneri, in: Marci Antonii Ingignerii sacrae cantiones, senis vocibus

decantandae. Liber primus ad Sanctiss. D.N. Gregorium XIIII pont. opt. et max.

(Venezia, Angelo Gardano, 1591).

Clefs: C1; C3; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke; Circle-stroke, 3/2.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F.

Range: 15 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 3; Malipiero, pp. 6-7; Cesari, pp. 220-21. Malipiero

has the wrong clef for the bass part placing it an octave higher than Monteverdi

intended.

No.4. SURGE, PROPERA, AMICA MEA [SV 210]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 3; Tenor, p. 3; Bassus, p. 3

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve (but on the dotted breve from b. 24).

Liturgical context: The text is from the Song of Solomon, 2: 10-12, and these words

recur, in part, in the “Nigra sum” section of Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610. The words

16

�are not those of the antiphon Surge propera amica mea used variously for Feasts

belonging to the Common of Virgins since the motet continues differently. The words

here are those of a long Milanese (Ambrosian) antiphon for the Common of Virgins,

and the Introit Surge propera amica mea. It has not been possible to discern the exact

liturgical function of this motet.

This text had already been set by Ingegneri, Monteverdi’s teacher, in his Sacrarum

cantionum cum quinque vocibus, Marci Antonii Ingignerii musicis cathedralis

ecclesiae cremonensis praefecti. LiberPrimus. (Venezia, Angelo Gardano, 1576),

which is where Monteverdi probably got this precise text, but there appears to be no

connection between the settings. There are some clear indications of word painting in

this motet such as the rising phrase on the opening word “Surge”. However, this

opening melody bears a strong relation to that employed by Costanzo Festa in his

setting of “Surge amica mea” found in his Motetta trium vocum ab pluribus

authoribus composita quorum nomina sunt Iachetus Gallicus, Morales Hispanus,

Constantius Festa, Adrianus VVilgliardus (Venezia, 1543),p. xx. Other items from

Festa’s collection are also apparently related to pieces by Monteverdi; see for

example Sacrae Cantiunculae nos. 6 (and Festa: “Quam pulchra es”) and 7 (and

Festa: “Ave regina caelorum”).

Clefs: C1; C3; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke; Circle-stroke 3/2.

Key signatures: none. Final on D.

Range: 15 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 4; Malipiero, pp. 8-10; Cesari, pp. 222-24.

Malipiero has the wrong clef for the tenor part placing it an octave higher than

Monteverdi intended. Malipiero also misreads the rhythm in the Cantus part, bb. 4142.

No. 5 UBI DUO VEL TRES CONGREGATI [SV 211]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 4; Tenor, p. 4; Bassus, p. 4.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Soprano, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve (but on the dotted breve from b.20).

Liturgical context: Magnificat antiphon for the third day of the Third Week of Lent.

See for example the Liber Usualis, p. 1090. The text is derived from Matthew 18:20,

but the words “in nomine meo” are omitted from Monteverdi’s setting.

Clefs: C1; C1; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke; Circle-stroke 3/2.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F.

Range: 16 notes. Top two voices equal in range and cross frequently.

Note values: as in the original.

17

�Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 5; Malipiero, pp. 11-12; Cesari, pp. 225-27.

Malipiero has the wrong clef for the bass part placing it an octave higher than

Monteverdi intended. Also his text bb. 5-10 reads “in medio co-rum” for “in medio eo-rum”, and he inserts slurs between notes to make up for the “lost” syllable.

No.6 QUAM PULCHRA ES [SV 212]

Partbooks: Cantus, pp. 4-5; Tenor, pp. 4-5; Bassus, pp. 4-5.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Soprano, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve.

Liturgical context: this is not the antiphon text used variously for feasts of the Virgin

Mary (see for example the version in the Processionale Monasticum, p. 272), but the

work is certainly appropriate to a Marian Feast (see also no. 7). The text has greater

similarity with the responsory found in the Liber Responsorialis, p. 224. The words

are selected from the Song of Songs: 7:6 (Quam pulchra es et quem …); 4:1 (Quam

pulchra es amica mea …); 2:10 (Columba mea formosa …); 5:2 (Dilecta mea) and

2:14 (Vox enim tua …). The Roman antiphon chant is paraphrased in the Cantus part.

The work is based on a setting of the same text by Costanzo Festa, first published in a

four-voiced version in 1521. A three-voiced version (as in Monteverdi’s setting) of

Festa’s work, without the old-fashioned altus part, was first published in 1543 by

Antonio Gardano, founder of the publishing house that issued Monteverdi’s Sacrae

Cantiunculae, in his collection Motetta trium vocum ab pluribus authoribus

composita quorum nomina sunt Iachetus Gallicus, Morales Hispanus, Constantius

Festa, Adrianus VVilgliardus (Venezia, 1543), no. 14. For details of the different

versions of Festa’s motet together with a modern edition, see: Albert Seay, ed.,

Costanzo Festa Opera Omnia, Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae, 25 (American Institute

of Musicology, 1979), vol. V, xvi-xvii and 54-6. The connection between the works

by Monteverdi and Festa was first discovered by Arnold Hartman of Columbia

University, as reported in Leo Schrade, Monteverdi: Creator of Modern Music (New

York, 1950), p.94 fn. 8. In Monteverdi’s setting the imitation is the most sustained

and consistent between the Cantus and Bassus parts.

Clefs: C1; C1; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F.

Range:13 notes. Cantus and Tenor are equal in range with frequent crossing of parts.

Note values: as in the original.

Tenor: b. 37, extra breve, pitch F, inserted on the first beat in error.

Bassus: bb. 16, 24. Both contain attempts to indicate in movable type ligatures of 2

semibreves. These are the only points in the work where two consecutive semibreves

must be sung to the same syllable. Presumably Monteverdi, or his printer, used the

ligatures to signal that that must happen whatever the vagaries of the actual text

placement in the printed source (for example, the print places the two-syllable word

“veni” under a single ligature in b. 24).

18

�Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 6; Malipiero, pp. 13-14; Cesari, pp. 228-29.

Malipiero has the wrong clef in the bass part placing it an octave higher than

Monteverdi intended.

No.7. AVE MARIA, GRATIA PLENA [SV 213]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 5; Tenor, p. 5; Bassus, p. 5.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Soprano, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve.

Liturgical context: This is a famous but liturgically problematic text. It is the most

popular of all the Marian prayers and is also referred to as the “Ave”, the “Hail Mary”

or the “Angelic Salutation”. It was used in private as well as public devotions, and

was incorporated into the liturgy (as part of the Rosary) in the fifteenth century. The

text falls into two sections: the scriptural (bb. 1-19) and the intercessory (bb. 20-36).

The scriptural part is taken from Luke 1: 28, 42 and repeats the words of the Angel

Gabriel at the Annunciation. The second part, Sancta Maria, … ora pro nobis, is an

intercessory prayer to the Virgin. On the liturgical context of this prayer text and its

use by Monteverdi in his Vespers of 1610, see: David Blazey, “A Liturgical Role for

Monteverdi’s Sonata sopra Sancta Maria”, Early Music 17 (1989), 175-82. The

opening of this prayer is found in various litanies of the church, such as the Litaniae

Lauretanae (Litany of Loreto: see the Liber Usualis, p. 1857). The prayer had two

different endings which are combined in this motet. The first, Sancta Maria, Mater

Dei, ora pro nobis peccatoribus, is found in the writings of St. Bernardine of Siena

(1380-1444) and the Carthusians. A second ending, Sancta Maria, Mater Dei, ora pro

nobis nunc et in hora mortis nostrae, can be found in the writings of the Servites, in a

Roman Breviary, and in some German Dioceses. The current form of the prayer was

included in the reformed Breviary promulgated by Pope Pius V in 1568. In the motet

(bb. 18-21) the name “JESUS” is inserted in capital letters (the capitals are retained in

this edition) before the concluding prayer text. The insertion of the name “Jesus” into

the text may have been established by Pope Urban IV around the year 1262. Clearly

the obvious place for such a motet would be within some Marian celebration, as with

the previous item in the collection, Quam pulchra es.

The opening of the tenor part of the present motet, Ave Maria, shows a close

similarity to the opening of the tenor part of the setting of the same text by Iachet,

found in the same collection as Festa’s version of item 6 - the Motetta trium vocum

ab pluribus authoribus composita quorum nomina sunt Iachetus Gallicus, Morales

Hispanus, Constantius Festa, Adrianus VVilgliardus (Venice: Antonio Gardano,

1543). In the same collection, the opening of the cantus part of Festa’s setting of Ave

Regina coelorum seems to have provided the inspiration for the Cantus/Tenor

imitation here following bar b.23, at the words “ Mater Dei, ora pro nobis”. For a

sustained analysis of this motet showing how its devices are distinct from the

Northern Netherlandish style, see: Leo Schrade, Monteverdi: Creator of Modern

Music, pp. 96 and 99-100.

19

�Clefs: C1; C1; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F.

Range: 13 notes. The Cantus and Tenor cross frequently.

Note values: as in the original.

Tenor: The final note is a Long in the print in keeping with the conventional

presentation of final notes throughout. However, this would make the Tenor part one

breve longer than the other parts, and so it has been shortened to a breve. All other

final notes throughout the edition of the Sacrae Cantiunculae are kept as Longs. The

Malipiero edition simply omits the penultimate note of the Tenor part (a breve on F)

in an attempt to make all parts reach the final chord at the same moment. It seems

likely that this problem arose because Monteverdi (in haste to finish the work?)

simply copied over the final bars of motet no. 6, which he then lightly decorated, but

without due regard for the details of the text setting. Probably he would have

preferred all three parts to reach their final note at the same time, but apparently was

not able to ensure that this happened.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 7; Malipiero, pp. 15-16; Cesari, pp. 230-33.

Malipiero has the wrong clef for the bass part placing it an octave higher than

Monteverdi intended

No.8. DOMINE PATER, ET DEUS [SV 214]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 6; Tenor, p. 6; Bassus, p. 6.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto,Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve.

Liturgical context: This is a Responsory text (slightly curtailed) for Sundays for

Feasts of the first rank. For the Roman chant see, for example, sources in the Vatican

Library (I-Rvat B 79, f. 142r) and the British Library (GB-Lbl Add. 29988, f. 111r).

The text is from Ecclesiasticus 23: 4, 5 and 6. The Biblia Vulgata (Vulgate Bible) has

‘Extollentiam” for the “Extollentia” found in the text, bb. 12-14, of the Sacrae

Cantiunculae version. Fabbri, Monteverdi (p.11), describes the text of this work as

“not identified”. Responsories were usually sung at Matins (as a response to the Bible

Readings), and they were also employed in processions on major feast days.

Clefs: C1; C3; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F.

Range: 14 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 8; Malipiero, pp. 17-18; Cesari, pp. 232-33.

Malipiero has the wrong clef for the bass part placing it an octave higher than

Monteverdi intended

20

�No.9a. TU ES PASTOR OVIUM Prima pars [SV 215a]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 6; Tenor, p. 6; Bassus, p. 6.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto,Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve (but on the dotted breve from b.20).

Liturgical Context: Magnificat antiphon from 1st Vespers, for the Feast of St. Peter

and St. Paul (29th June). See for example the Liber Usualis, p. 1516. Text based on

Matthew 16: 19.

Clefs: C1; C3; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke; Circle-stroke 3/2.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F.

Range: 16 notes. Parts cross only once (Bass/Tenor, b. 9).

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, pp. 8-9; Malipiero, p. 19; Cesari, pp. 234-35. Malipiero

has the wrong clef for the bass part placing it an octave higher than Monteverdi

intended.

No.9b. TU ES PETRUS, ET SUPER HANC PETRAM Secunda pars [SV 215b]

Partbook: Cantus, p. 7; Tenor, p. 7; Bassus, p. 7.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto/Tenor, Tenor/Bass.

The beat is on the semibreve (but on the dotted breve from b. 26).

Liturgical Context: This appears to be based on the Offertory for the Feast of The

Chair of St Peter at Rome. See, for example, Liber Usualis, pp. 1333-1334. The text

is from Matthew 16:18-19. However, Monteverdi’s motet reverses the order of the

middle clause (“et portae inferi …”) and the final clause ( “in tibi dabo …”). Fabbri

(Monteverdi, p. 11), wrongly identifies this motet text as the fifth antiphon for Lauds

at the Feast of St Peter and St Paul (see for example the Liber Usualis, pp. 15151516), but that antiphon only accounts for the text up to b.13.

Clefs: C1; C3; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke; Circle-stroke 3/2.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F.

Range: 15 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 9; Malipiero, pp. 20-21; Cesari, pp. 236-37.

Malipiero has the wrong clef for the bass part placing it an octave higher than

Monteverdi intended.

21

�No.10a. O MAGNUM PIETATIS OPUS Prima pars [SV 216a]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 7; Tenor, p. 7; Bassus, p. 7.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve (except for the cross rhythms in bb. 18 and 19).

Liturgical context: Magnificat antiphon, 2nd Vespers, for the Feast of The Finding of

the Holy Cross (May 3rd). See for example the Liber Usualis, p. 1459.

Clefs: G2; C2; C3.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: none. Final on G.

Range: 12 notes. Tenor/Bassus cross once, b.10. No other crossings.

Note values: as in the original.

Cantus: the coloration in bb.18-19 - three semibreves in the time of the previous

breve (in b.17), but with the first and last two semibreve beats divided into a triplet

and given a long-short rhythm - may have been intended by Monteverdi, though it is

also possible that the black notes are simply symbolic Augenmusik for the word

‘mortua’. On the other hand the same device occurs in No. 10b. but with a different

text. Malipiero in his edition ignores the coloration in both 10a. and 10b.

Bassus: the rhythm as given in b. 14 does not quite accurately reflect that of the halfcolored ligature in the original, which implies that the pitches E and F form a longshort triplet figure for the space of a semibreve, rather than the dotted one given in the

edition. However, it is likely that Monteverdi intended the Bassus rhythm to match

the dotted-minim-crotchet figure in the Cantus, and it is this example that has

persuaded the editor to transcribe all such half-colored ligatures as dotted rhythms

throughout the edition. The half-colored ligature is found extensively in works by

Ingegneri from around this time, for example in his “Beata viscera”, “Exaudi

Domine”, “Quam fecit”, and “Nimis exaltatis”, all from his Sacrarum Cantionum …

(Venezia, 1576), the source that also contains a setting of “Surge propera” as found in

motet no. 4 in this collection.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 10; Malipiero, p. 22; Cesari, p. 238. Malipiero

ignores the coloration and imperfection in the notation bb.18-19.

No.10b. ELI CLAMANS SPIRITUM PATRI Secunda pars [SV 216b]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 8; Tenor, p. 8; Bassus, p. 8.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve (except for the cross rhythms bb. 22-26).

22

�Liturgical context: This is a fragment of a hymn taken from the Hours of the Holy

Cross, found in Books of Hours used in private devotions. It may have been used on

the Feast of The Finding of the Holy Cross (3rd May) as was 10a. The words are

woven together from Luke 23: 45, 46; John 19: 34; and (less directly) Matthew 27: 46,

50. The full text of the hymn is:

Hora Nona Dominus

Jesus expiravit.

Eli clamans spiritum

Patri commendavit;

Latus eius lancea

Miles perforavit;

Terra tunc contremuit

Et sol obscuravit.

It is not clear where Monteverdi got this text. In this collection only this text and the

sequence “Lauda, Syon” (no. 19) are in poetry, all the rest are in prose. It has attracted

few musical settings, though there is a complete one by the English composer Martin

Peerson (c. 1573-1651). In this truncated version Monteverdi perhaps intended the

description of the setting (in the first two lines) to be declaimed by the officiant, and

then to start the music with the dramatic details. If so, he failed to take musical

advantage of either his specially extracted dramatic opening “Eli clamans”, or the

regular rhythms of the verses, or the opportunities for musical rhyme at

commendavit/perforavit/obscuravit. That the text occurs in Books of Hours suggests

that the work may have been intended for use in private devotions, perhaps in the

household of the dedicatee of the collection, Stefano Caninio Valcarengo.

Clefs: G2; C2; C3.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: none. Final on G.

Range: 16 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 10; Malipiero, pp. 23-24; Cesari, pp. 239-40.

Malipiero has the wrong clef for the bass part placing it an octave higher than

Monteverdi intended. He also displays the wrong original clef for the tenor part (he

gives C1), and ignores the coloration and imperfection notational issues in bb. 22-26.

No.11. O CRUX BENEDICTA [SV 217]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 8; Tenor, p. 8; Bassus p. 8.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve (but on the dotted breve, bb. 17-26)

23

�Liturgical context: Magnificat antiphon, 2nd Vespers, for the Feast of the Exaltation of

the Holy Cross (14th September). See for example the Liber Usualis, with its rubric on

p.1630 and chant on p. 1631. Additional to the standard text the word “angelorum”

has been inserted (bb. 12 ff.) after the word “Dominum”. Cesari, p. cv, draws

attention to the evident parallelism between that insertion and the phrase “Ave

Dominum angelorum” from the famous Marian antiphon Ave Regina caelorum (see

the Liber Usualis, p. 274).

Clefs: G2; C2; C3.

Time signatures: C-stroke; Circle-stroke 3/2; C-stroke.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F.

Range: 13 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 11; Malipiero, p. 25; Cesari, pp. 241-42. Malipiero

has the wrong clef for the bass part placing it an octave higher than Monteverdi

intended.

No.12. HODIE CHRISTUS NATUS EST [SV 218]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 9; Tenor, p. 9; Bassus, p. 9.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve.

Liturgical context: Magnificat antiphon, 2nd Vespers for Christmas. See for example

the Liber Usualis, p. 413. The text is partly based on Luke 2: 14. For an analysis of

Monteverdi’s motivic devices in this work see Leo Schrade, Monteverdi: Creator of

Modern Music, p. 97.

Clefs: G2; C2; C3.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on G.

Range: 16 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, pp. 11-12; Malipiero, pp. 26-28; Cesari, pp. 243-45.

Terrabugio transposes this motet down a minor third.

No.13a. O DOMINE IESU CHRISTE, ADORO TE IN CRUCE PENDENTEM

[SV 219a]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 10; Tenor, p. 10; Bassus, p.10

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve.

24

�Liturgical context: this, together with no.13b, are the first two of seven prayers

meditating on Christ’s Passion attributed to Pope St. Gregory the Great and frequently

found in Books of Hours. It is not known where Monteverdi discovered these texts

though there is an undated setting for four voices by Willaert edited in A. Willaert:

Opera Omnia, ed. H. Zenk and W. Gerstenberg, Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae iii/1,

10 (Rome, 1950). Ingegneri also later set this text in his Sacrarum cantionum cum

quatuor vocibus, Marci Antonii Ingignerii musicis cathedralis ecclesiae cremonensis

praefecti. Liber primus, item 9. In Books of Hours the prayer was usually

accompanied by a picture of St. Gregory genuflecting at the Consecration with Christ

appearing on the Crucifix in front of the Altar. Fabbri (Monteverdi, p.11), says that

the text and context of this work are “not identified”.

Leo Schrade (Monteverdi: Creator of Modern Music, p.97), draws attention to the

melodic links between 13a and 13b, for example at the setting of the words “deprecor

te”, bb.16-19 in 13a and bb.19-21 in 13b.

Clefs: G2; C2; C3.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: none . Final on G.

Range: 15 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 13; Malipiero, pp. 29-30; Cesari, pp. 246-47.

Malipiero, Canto b. 1 has incorrect pitch G.

No.13b. O DOMINE IESU CHRISTE, ADORO TE IN CRUCE VULNERATUM

[SV 219b]

Partbooks: Cantus, pp. 10-11; Tenor, pp. 10-11; Bassus, pp. 10-11.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve.

Liturgical context: the second of seven prayers meditating on Christ’s Passion

attributed to Pope St. Gregory the Great and frequently found in Books of Hours. For

further details see no.13a above. Fabbri, Monteverdi (p.11), says that the text and

context of this work are “not identified”.

Note the dissonances expressing Christ’s agonies on the cross, bb, 13-14. Leo

Schrade (Monteverdi: Creator of Modern Music, p. 97), draws attention to the

melodic links between 13a and 13b, for example at the setting of the words “deprecor

te”, bb.16-19 in 13a and bb.19-21 in 13b.

Clefs: G2; C2; C3.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: none. Final on G.

Range: 15 notes.

25

�Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 14; Malipiero, pp. 31-32; Cesari, pp. 248-49.

No.14. PATER, VENIT HORA [SV 220]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 11; Tenor, p. 11; Bassus, p.11

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve (but on the dotted breve from b.21).

Liturgical context: antiphon for Feria IV in Rogation Week at the Vigil of the Feast of

the Ascension. See, for example, the Antiphonale Monasticum Pro Diurnis Horis, p.

503. Text based on John 17: 1, 5.

Clefs: G2; C2; C3.

Time signature: C-stroke; Circle-stroke 3/2.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on G.

Range: 13 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Tenor: it is unclear why Monteverdi (or the printer) employed coloration in the Tenor

part, bb. 27-29, while the Bassus part with almost the same rhythm has none.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 15; Malipiero, p. 33; Cesari, pp. 250-51.

No.15. IN TUA PATIENTIA POSSEDISTI [SV 221]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 12; Tenor, p. 12; Bassus, p.12

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve.

Liturgical context: Magnificat antiphon for First Vespers of the Feast of St. Lucy

(December 13th). See for example Liber Usualis, pp. 1322-1323. Text based on Luke

21: 19.

Clefs: G2; C2; C3.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: none. Final on F.

Range:15 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 16; Malipiero, pp. 34-35; Cesari, pp. 252-54. In

Malipiero syllables 2 to 6 of the text are misaligned with the music in all parts.

26

�No.16. ANGELUS AD PASTORES AIT [SV 222]

Partbooks: Cantus, pp. 12-13; Tenor, pp. 12-13; Bassus, pp. 12-13.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Alto, Tenor.

The beat is on the semibreve (but in bb.13-23 it is on the dotted breve).

Liturgical context: Third antiphon for the Office of Lauds on the Nativity (Christmas

Day). See for example Liber Usualis, p. 397. Text based on Luke 2: 10, 11.

Clefs: G2; C1; C3.

Time signatures: C-stroke; Circle-stroke 3/2; C-stroke.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on F

Range: 15 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 17; Malipiero, pp. 36-37; Cesari, pp. 255-56; K. G.

Fellerer, ed., Angelus ad pastores ait (Mainz, B. Schott’s Söhne, 1936) Canticum

Vetum, no. 12. Fellerer halves the original note values, and provides a keyboard

reduction.

No.17. SALVE CRUX PRECIOSA [SV 223]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 13; Tenor, p. 13; Bassus, p. 13

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Tenor, Bass.

The beat is on the semibreve.

Liturgical context: This is an antiphon with various uses. For example, it is the first

antiphon at Lauds for the Feast of St. Andrew Apostle (30th November) - see for

example the Antiphonale Monasticum, p. 755. Also, it is the first antiphon at Second

Vespers for the same Feast (which happens to begin the liturgical year) - see for

example the Liber Usualis, p. 1307. The openings of the Cantus and Bassus parts

paraphrase the beginning of the Marian Antiphon ‘Salve Regina mater misericordiae’

(compare the chant in the Liber Usualis, p. 276). There is a setting of ‘Salve crux

preciosa’ for five voices attributed to Cipriano da Rore, but published posthumously

in 1595.

Clefs: C1; C3; C4.

Time signature: C-stroke.

Key signatures: B-flat; B-flat; B-flat. Final on G.

Range: 16 notes.

Note values: as in the original.

Previous editions: Terrabugio, p. 18; Malipiero, pp. 38-39; Cesari, pp. 257-8.

Terrabugio transposes this piece down a tone. Malipiero has the wrong clef in the

bassus part placing it an octave higher than Monteverdi intended.

27

�No.18. QUIA VIDISTI ME, THOMA, CREDIDISTI [SV 224]

Partbooks: Cantus, p. 14; Tenor, p. 14; Bassus, p. 14.

Suggested performance forces: Soprano, Tenor, Bass.